Overview and Recent Developments

Since assuming the throne from his late father on February 7, 1999, Jordan's 57-year-old monarch King Abdullah II bin Al Hussein (hereinafter King Abdullah II) has maintained Jordan's stability and strong ties to the United States. Although Jordan faces a number of socio-economic challenges, the monarchy has remained resilient owing to a number of factors. These include a strong sense of social cohesion, strong support for the government from both Western powers and the Gulf Arab monarchies, and an internal security apparatus that is highly capable and, according to human rights groups, uses vague and broad criminal provisions in the legal system to dissuade dissent by detaining protesters.1

Despite this resilience, Jordanians are becoming increasingly dissatisfied with economic conditions, corruption, and lack of political reform. According to the public opinion research firm Arab Barometer, "Trust in political institutions is in steep decline across the board - including government, parliament and even the judiciary…. Citizens are particularly frustrated with the government's efforts to create jobs and limit inflation. As a result, almost half of all Jordanians are considering emigrating."2

In fall 2019, 100,000 public school teachers organized a nationwide strike, demanding that the government raise teacher salaries. After the strike shut down schools for a month, the government partially acceded to their demands, despite budgetary strains as the government attempts to cut expenses to comply with the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) three-year, $723 million Extended Fund Facility reform program.3 The teachers' strike marked the second major instance of unrest in the last two years over economic conditions. In 2018, when the government tried to raise income taxes, mass protests ensued, forcing the government to revise its tax plan and turn to the Arab Gulf monarchies, who collectively pledged $2.5 billion to Jordan in grants and loans in order to stabilize the kingdom's fiscal position.

In 2019, as many Arab governments face youth-driven, popular dissatisfaction, it is becoming unclear how the government of Jordan will be able to appease its restive public given the limited policy tools and financial options at its disposal. In the past 18 months, the prime minister has reshuffled the cabinet four times. While this type of move may have once demonstrated government attentiveness to reform, the public may no longer perceive such action as sufficient if it is not accompanied by significant improvements to the economy.4

Public criticism is increasingly being directed toward the monarchy itself rather than the prime minister and cabinet. According to the Economist, "The people used to blame greedy ministers and corrupt officials for their misery—and looked to the king for remedies. Now when they protest, as they often do, they call out King Abdullah by name." 5 During the teacher strike, Queen Rania faced a barrage of criticism over social media for insufficiently supporting the teachers' cause. In an unprecedented royal response to public criticism, the Queen posted a letter on her Facebook account reiterating her support for education initiatives and directly addressing personal critiques against her.6

U.S.-Jordanian relations remain close overall, despite Jordanian concerns about Trump Administration changes to long-standing U.S. policies on Israel and the Palestinians.7 Palestinians have criticized these changes as unfairly punitive to them and biased toward Israel.8 While Jordanian leaders have felt compelled to acknowledge criticism of the U.S. policy changes among their people, they also have sought to maintain strong bilateral relations with the United States.9 In trying to balance U.S.-Jordanian relations with domestic concerns about Palestinian rights, King Abdullah II has refrained from directly criticizing the Trump Administration, while urging the international community to return to the goal of a two-state solution that would ultimately lead to an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.10

The United States has deployed nearly 3,000 U.S. troops to Jordan as part of its effort to combat the Islamic State and defend against possible threats from Syria. Congress appropriated an estimated $1.28 billion in total aid for Jordan in FY2019 and is considering another $1.27 billion for FY2020.

Jordan has been without a U.S. ambassador since the departure of Ambassador Alice Wells in January 2017. The Trump Administration in November 2019 nominated Henry Wooster, a Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs at the State Department, as the next U.S. ambassador to the kingdom.

Country Background

Although the United States and Jordan have never been linked by a formal treaty, they have cooperated on a number of regional and international issues for decades. Jordan's small size and lack of major economic resources have made it dependent on aid from Western and various Arab sources. U.S. support, in particular, has helped Jordan deal with serious vulnerabilities, both internal and external. Jordan's geographic position, wedged between Israel, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, has made it vulnerable to the strategic designs of its powerful neighbors, but has also given Jordan an important role as a buffer between these countries in their largely adversarial relations with one another.

Jordan, created by colonial powers after World War I, initially consisted of desert or semidesert territory east of the Jordan River, inhabited largely by people of Bedouin tribal background, the original "East Bank" Jordanians. The establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 brought large numbers of Palestinian refugees to Jordan, which subsequently unilaterally annexed a Palestinian enclave west of the Jordan River known as the West Bank.11 The "East Bank" Jordanians, though probably no longer a majority in Jordan, remain predominant in the country's political and military establishments and form the bedrock of support for the Jordanian monarchy. Jordanians of Palestinian origin comprise an estimated 55% to 70% of the population. They tend to gravitate toward employment in the private sector, most likely due to their alleged general exclusion from certain public-sector and military positions.12

The Hashemite Royal Family

Jordan is a hereditary constitutional monarchy under the prestigious Hashemite family, which claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad. King Abdullah II (age 57) has ruled the country since 1999, when he succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father, the late King Hussein, who had ruled for 47 years. Educated largely in Britain and the United States, King Abdullah II had earlier pursued a military career, ultimately serving as commander of Jordan's Special Operations Forces with the rank of major general. The king's son, Prince Hussein bin Abdullah (born in 1994), is the designated crown prince.13

The king appoints a prime minister to head the government and the Council of Ministers (cabinet). On average, Jordanian governments last no more than 15 months before they are dissolved by royal decree. The king also appoints all judges and is commander of the armed forces.

Political System and Key Institutions

The Jordanian constitution, most recently amended in 2016, gives the king broad executive powers. The king appoints the prime minister and may dismiss him or accept his resignation. He also has the sole power to appoint the crown prince, senior military leaders, justices of the constitutional court, and all 75 members of the senate, as well as cabinet ministers. The constitution enables the king to dissolve both houses of parliament and postpone lower house elections for two years.14 The king can circumvent parliament through a constitutional mechanism that allows the cabinet to issue provisional legislation when parliament is not sitting or has been dissolved.15 The king also must approve laws before they can take effect, although a two-thirds majority of both houses of parliament can modify legislation. The king also can issue royal decrees, which are not subject to parliamentary scrutiny. The king commands the armed forces, declares war, and ratifies treaties. Finally, Article 195 of the Jordanian Penal Code prohibits insulting the dignity of the king (lèse-majesté), with criminal penalties of one to three years in prison.

Jordan's constitution provides for an independent judiciary. According to Article 97, "Judges are independent, and in the exercise of their judicial functions they are subject to no authority other than that of the law." Jordan has three main types of courts: civil courts, special courts (some of which are military/state security courts), and religious courts. State security courts administered by military (and civilian) judges handle criminal cases involving espionage, bribery of public officials, trafficking in narcotics or weapons, black marketeering, and "security offenses." The king may appoint and dismiss judges by decree, though in practice a palace-appointed Higher Judicial Council manages court appointments, promotions, transfers, and retirements.

Although King Abdullah II in 2013 laid out a vision of Jordan's gradual transition from a constitutional monarchy into a full-fledged parliamentary democracy,16 in reality, successive Jordanian parliaments have mostly complied with the policies laid out by the Royal Court. The legislative branch's independence has been curtailed not only by a legal system that rests authority largely in the hands of the monarch, but also by electoral laws designed to produce pro-palace majorities with each new election.17 Due to frequent gerrymandering in which electoral districts arguably are drawn to favor more rural pro-government constituencies over densely populated urban areas, parliamentary elections have produced large pro-government majorities dominated by representatives of prominent tribal families.18 In addition, voter turnout tends to be much higher in pro-government areas since many East Bank Jordanians depend on family/tribal connections as a means to access patronage jobs.19 The next parliamentary election for the 130-seat House of Deputies (lower chamber) is tentatively scheduled for September 2020.

|

Area: 89,342 sq. km. (34,495 sq. mi., slightly smaller than Indiana) Population: 10,458,413 (July 2018); Amman (capital): 4.008 million (2015) Ethnic Groups: Arabs 97%; other 2.6% (includes Armenians, Circassians) (2015) Religion: Sunni Muslim 97.2%; Christian 2.2%; Buddhist 0.4%; Hindu 0.1% Percent of Population Under Age 25: 54% (2018) Literacy: 95.4% (2015) Youth Unemployment (ages 15-24): 40.1% (2019) Source: Graphic created by CRS; facts from CIA World Factbook and World Bank. |

The Economy

With few natural resources and a small industrial base, Jordan has an economy that depends heavily on external aid, tourism, expatriate worker remittances, and the service sector. Among the long-standing problems Jordan faces are poverty, corruption, slow economic growth, and high levels of unemployment. The government is by far the largest employer; between one-third and two-thirds of all workers are on the state's payroll. These public sector jobs, along with government-subsidized food and fuel, have long been part of the Jordanian government's "social contract" with its citizens.

|

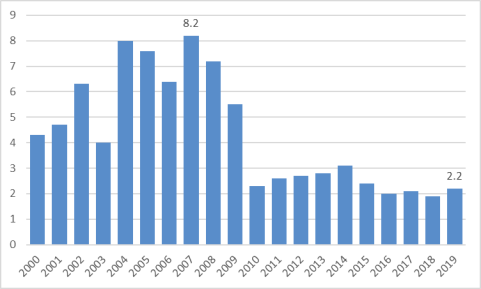

Figure 2. GDP Growth in Jordan Annual percent change in GDP growth (%) 2000-2019 |

|

|

Source: International Monetary Fund, 2019. |

In the past decade, this arrangement between state and citizen has become more strained. When oil prices skyrocketed between 2007 and 2008, the government had to increase its borrowing in order to continue fuel subsidies. The 2008 global financial crisis was another shock to Jordan's economic system, as it depressed worker remittances from expatriates. The unrest that spread across the region in 2011 further exacerbated Jordan's economic woes, as the influx of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees increased demand for state services and resources. Tourist activity, trade, and foreign investment decreased in Jordan after 2011 due to regional instability.

Jordan, like many other countries, has experienced uneven economic growth, with higher growth in the urban core of the capital Amman and stagnation in the historically poorer and more rural areas of southern Jordan. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Amman is the most expensive Arab city and the 25th-most expensive city to live in globally.20

Popular economic grievances have spurred the most vociferous protests in Jordan. Youth unemployment is high, as it is elsewhere in the Middle East, and providing better economic opportunities for young Jordanians outside of Amman is a major challenge. Large-scale agriculture is not sustainable because of water shortages, so government officials are generally left providing young workers with low-wage, relatively unproductive civil service jobs. How the Jordanian education system and economy can respond to the needs of its youth has been and will continue to be one of the defining domestic challenges for the kingdom in the years ahead.

Jordan's economy is projected to grow 2.2% during 2020, though public debt has swelled to 94% of GDP ($40 billion), undermining the government's ability to stimulate growth with additional spending. Unemployment remains at about 19%, posing a continual challenge for Jordan's youthful population; nearly two-thirds of all Jordanians are under the age of 30.21 According to the World Bank, youth unemployment (ages 15-24) is 40.1%.22

Foreign Relations

Israel and the Palestinians

The Jordanian government has long described efforts to secure a lasting end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as one of its highest priorities. In 1994, Jordan and Israel signed a peace treaty,23 and King Abdullah II has used his country's relationship with Israel to improve Jordan's standing in the international community. Nevertheless, the persistence of Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues to be a major challenge for Jordan, as the issue of Palestinian rights resonates with much of the population. Twenty-five years after the signing of the Jordanian-Israeli peace treaty, the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict has soured attempts to improve Jordanian-Israeli people-to-people relations. Various short-lived diplomatic disputes (see below) between Jordan and Israel also have led to tensions in government-to-government relations, despite ongoing security cooperation. Israeli control of Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem (see text box below) is a perpetual concern for the Jordanian monarchy and its domestic legitimacy.24

|

Holy Sites in Jerusalem25 Per arrangements with Israel dating back to 1967 (when the Israeli military seized East Jerusalem—including its Old City—from Jordan) and then subsequently confirmed in the 1994 Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty, Israel acknowledges a continuing role for Jordan vis-à-vis Jerusalem's historic Muslim shrines.26 A Jordanian waqf (or Islamic custodial trust) has long administered the Temple Mount (known by Muslims as the Haram al Sharif or Noble Sanctuary) and its holy sites, and this role is key to bolstering the religious legitimacy of the Jordanian royal family's rule. Jordanian monarchs trace their lineage to the Prophet Muhammad. Disputes over Jerusalem that appear to circumscribe King Abdullah II's role as guardian of the Islamic holy sites create a domestic political problem for the King. Jewish worship on the Mount/Haram is prohibited under a long-standing "status quo" arrangement that dates back to the era of Ottoman control before World War I. |

Jordan and Trump Administration Peace Plans

Since December 2017, when the Palestinians broke off high-level political contacts with the United States after President Trump's decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital and relocate the U.S. embassy there, Jordan has been caught in the middle of acrimony between the Trump Administration and the Palestinian Authority. Jordan has expressed solidarity with the Palestinians while also trying to encourage the Administration to commit to the two-state solution. On several occasions in 2019, Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman al Safadi reiterated that it is the kingdom's long-standing position that any final Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement should include a Palestinian state based on the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital.27

When the Administration has taken action in relation to the peace process, Jordan has found it difficult to broadly support U.S. initiatives without the participation of the Palestinians. For example, in June 2019, Bahrain hosted the "Peace to Prosperity Workshop," a meeting of diplomats and private sector leaders to discuss ways of advancing peace through economic cooperation and foreign investment. Palestinian officials boycotted the workshop, and Jordan sent a deputy minister of finance.

Israeli Settlements and Possible Annexation

Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu pledged—as part of his election campaign in April 2019—to begin annexing Israeli settlements in the West Bank. During his September 2019 campaign, Netanyahu announced his specific intention if reelected to annex the Jordan Valley—the lightly populated area along Jordan's western border that Israel has largely used as a defensive buffer area since it captured the West Bank in 1967. Jordan strongly objects to Israeli unilateral annexation of territory in the West Bank. When asked to respond to Netanyahu's annexation plans, King Abdullah stated in a September 2019 MSNBC interview:

Well again, I do take a pinch of salt in electioneering. But a statement like that does not help at all because what you do is then hand over the narrative to the worst people in our neighborhood. And we that want peace, want to be able to move forward, tend to be more isolated. If the policy is to annex the West Bank, then that is going to have a major impact on the Israeli-Jordanian relationship, and also on the Egyptian-Israeli relationship because we are the two only Arab countries that have peace with Israel.28

In November 2019, after Secretary of State Pompeo remarked that "the establishment of Israeli civilian settlements in the West Bank is not per se inconsistent with international law,"29 Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi tweeted, "We warn of the danger of changing the US position towards the settlements and its impact on peace efforts at a time when the peace process faces unprecedented challenges as a result of Israeli policies and practices that kill all chances of resolving the conflict."30

Jordan Ends Israeli Access to Territories

In late 2018, the king announced (via Twitter) that his government would not renew a provision in its 1994 peace treaty with Israel that allowed Israel access to the Jordanian territories of Baqoura and Al Ghumar, which are agricultural areas in northern and southern Jordan, respectively.31 According to one Jordanian commentator, "Domestically, the King's decision is a much-needed shot in the arm for the government at a time when it is facing public pressure over its unpopular economic policies."32 After several failed Israeli attempts to negotiate with Jordan over the renewal of access to the territories, Jordan ended its lease to Israel on November 10, 2019. A day later, King Abdullah, the Crown Prince, and several high level military officials made an official visit to Baqoura to publicly demonstrate Jordanian sovereignty over the area.33

|

Figure 3. Jordanian Officials Pray at Recently Reclaimed Area from Israel |

|

|

Source: Royal Hashemite Court. |

Jordanian-Israeli Dispute over Prisoners

During summer 2019, Israel detained two Jordanians who crossed into Israel. One of the detainees, 24-year-old Heba al Libadi, who crossed from Jordan to the West Bank to attend a wedding, was arrested for suspected ties to Hezbollah based on past travels to Lebanon. Libadi proclaimed her innocence and launched a hunger strike to draw attention to her arrest and reported ill-treatment. Her detention drew widespread media coverage in the kingdom, and the Jordanian government recalled its ambassador to Israel in order to pressure Israel for the release of its citizens.34 Israel released the detainees in early November 2019.

Water Scarcity and Israeli-Jordanian-Palestinian Water Deal

Jordan is among the most water-poor nations in the world and ranks among the 10 countries with the lowest rate of renewable fresh water per capita.35 According to the Jordan Water Project at Stanford University, Jordan's increase in water scarcity over the last 60 years is attributable to an approximate 5.5-fold population increase since 1962, a decrease in the flow of the Yarmouk River due to the building of dams upstream in Syria, gradual declines in rainfall by an average of 0.4 mm/year since 1995, and depleting groundwater resources due to overuse.36 The illegal construction of thousands of private wells also has led to unsustainable groundwater extraction. The large influx of Syrian refugees has heightened water demand in the north.

To secure new sources of fresh water, Jordan has pursued cooperative water projects with its neighbors. On December 9, 2013, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority signed a regional water agreement (officially known as the Memorandum of Understanding on the Red-Dead Sea Conveyance Project) to pave the way for the Red-Dead Canal, a multibillion-dollar project to address declining water levels in the Dead Sea.37 The agreement was essentially a commitment to a water swap, whereby half of the water pumped from the Red Sea is to be desalinated in a plant to be constructed in Aqaba, Jordan. Some of this water is to then be used in southern Jordan. The rest is to be sold to Israel for use in the Negev Desert. In return, Israel is to sell fresh water from the Sea of Galilee to northern Jordan and sell the Palestinian Authority discounted fresh water produced by existing Israeli desalination plants on the Mediterranean. The other half of the water pumped from the Red Sea (or possibly the leftover brine from desalination) is to be channeled to the Dead Sea. Exact allocations of swapped water were not part of the 2013 MOU and were left subject to future negotiations.

|

Natural Gas Deal with Israel In September 2016, Jordan's state-run National Electric Power Company (NEPCO) signed a 15-year, $10 billion natural gas import deal with a consortium of U.S. (Noble Energy Inc.) and Israeli (Delek Drilling-LP and others) companies. The contract calls for the companies to supply 1.6 trillion cubic feet of natural gas to Jordan, which would reportedly meet an estimated 40% of the country's electricity needs and save the Jordanian government hundreds of millions annually in energy costs.38 Shipments to Jordan from Israel's offshore Leviathan field are to begin in early 2020 through a pipeline currently under construction. Anti-normalization forces (Jordanians opposed to cooperation with Israel) within Jordan have used the gas deal as a rallying cry, calling on the government to cancel the deal. Jordan's Constitutional Court ruled that its parliament cannot legally nullify the gas contract39 and, barring a serious bilateral crisis, Jordan's extensive energy import needs make it unlikely that it would end energy cooperation with Israel. |

Congress has supported the Red-Dead Sea Conveyance Project. P.L. 114-113, the FY2016 Omnibus Appropriations Act, specified that $100 million in Economic Support Funds (ESF) be set aside for water sector support for Jordan, to support the Red Sea-Dead Sea water project. In September 2016, USAID notified Congress that it intended to spend $100 million in FY2016 ESF-Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) assistance on Phase One of the project.40

In 2017, with Trump Administration officials expressing a commitment to reviving the moribund Israeli-Palestinian peace process, U.S. officials focused on finalizing the terms of the 2013 MOU. In July 2017, the White House announced that then-U.S. Special Representative for International Negotiations Jason Greenblatt had "successfully supported the Israeli and Palestinian efforts to bridge the gaps and reach an agreement," with the Israeli government agreeing to sell the Palestinian Authority (PA) 32 million cubic meters (MCM) of fresh water.41

Nearly six years after signing of the MOU on the Red-Dead Canal, the project remains stalled, arguably due to Israeli domestic politics, the overall cost of the project, and ongoing tensions in Jordanian-Israeli relations.42

Syria

Jordanian-Syrian relations have been strained since 2011. King Abdullah was the first Arab leader to openly call for Syrian President Bashar Al Asad's resignation in November 2011, and Jordan supported moderate Syrian rebel groups operating in southwestern Syria until these groups were largely defeated in 2018.43 Once the Asad regime reclaimed control of southern Syria (with the help of Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah), Jordan has sought to return to normal bilateral ties. Along the kingdom's northern border with Syria, many Jordanian residents share familial ties with Syrian families. Over the past year, several Jordanian delegations have visited Syria, and the two countries opened the Nasib/Jaber border crossing to facilitate greater bilateral trade, though economic relations have not returned to pre-2011 levels due to trade barriers, sanctions, and security impediments.44

Syria remains a primary problem for Jordan's security. The kingdom shares security concerns with Israel over the presence of Iranian and Hezbollah forces operating near Jordan's borders. According to one account, "Former Free Syrian Army rebels who have returned to their hometowns in southern Syria after an amnesty agreement with the regime say Hezbollah is effectively 'governing' several towns and villages. Hezbollah and Shiite militias patrol areas dressed as uniformed Syrian regime forces in order to avoid being hit by Israeli airstrikes, they say, or, more frequently, deploy former rebel fighters to patrol areas and provide intelligence directly to the Iran-backed paramilitary group."45

The kingdom also continues to host hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees, many of whom are reluctant to return to their homes for fear of Syrian regime retribution against them. 46 Since 2011, the influx of Syrian refugees has placed tremendous strain on Jordan's government and local economies, especially in the northern governorates of Mafraq, Irbid, Ar Ramtha, and Zarqa. As of November 2019, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there are 654,266 registered Syrian refugees in Jordan.

The United States has used Jordanian territory to monitor and implement U.S. assistance programs to opposition-held areas in Syria. While the Trump Administration ended U.S. funding for stabilization assistance to Syria in 2018, some programs have continued using non-U.S. funding, and the Southern Syria Assistance Platform (SSAP) based in Amman continues to monitor foreign assistance to opposition-held areas in Syria.47

U.S. Relations

U.S. officials frequently express their support for Jordan, citing its role in countering the Islamic State, support for U.S. policy toward Syria, and role as a force for moderation in the Arab world, both in its regional outlook and internal politics.48 At a time when traditional U.S. partnerships with key regional actors like Saudi Arabia and Turkey are fraught, U.S.-Jordanian relations remain solid. President Trump has acknowledged Jordan's role as a key U.S. partner in countering the Islamic State, as many U.S. policymakers advocate for continued robust U.S. assistance to the kingdom. Annual aid to Jordan has nearly quadrupled in historical terms over the last 15 years. Jordan also hosts U.S. troops. According to President Trump's June 2019 War Powers Resolution Report to Congress, "At the request of the Government of Jordan, approximately 2,910 United States military personnel are deployed to Jordan to support Defeat-ISIS operations, enhance Jordan's security, and promote regional stability."49

U.S. Foreign Assistance to Jordan

The United States has provided economic and military aid to Jordan since 1951 and 1957, respectively. Total bilateral U.S. aid (overseen by the Departments of State and Defense) to Jordan through FY2017 amounted to approximately $20.4 billion. Jordan also has received hundreds of millions in additional military aid since FY2014 channeled through the Defense Department's various security assistance accounts. Currently, Jordan is the third-largest recipient of annual U.S. foreign aid globally, after Afghanistan and Israel.

|

Account |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 est. |

FY2020 Request |

|

ESF |

$615.000 |

$812.350 |

$832.350 |

$1,082.400 |

$841.908 |

$910.800 |

|

FMF |

$385.000 |

$450.000 |

$470.000 |

$425.000 |

$425.00 |

$350.000 |

|

NADR |

$7.700 |

$8.850 |

$13.600 |

$13.600 |

$13.600 |

$10.400 |

|

IMET |

$3.800 |

$3.733 |

$3.879 |

$4.000 |

$3.989 |

$3.800 |

|

Total |

$1,011.500 |

$1,274.933 |

$1,319.830 |

$1,525.000 |

$1,284.497 |

$1,275.000 |

Source: U.S. State Department.

Notes: Funding levels in this table include both enduring (base) and Overseas Contingency Operation (OCO) funds. For FY2019, Congress made available $50 million for Jordan from the Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF).

U.S.-Jordanian Agreement on Foreign Assistance

On February 14, 2018, the United States and Jordan signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on U.S. foreign assistance to Jordan. The MOU, the third such agreement between the United and Jordan, commits the United States to provide $1.275 billion per year in bilateral foreign assistance over a five-year period for a total of $6.375 billion (FY2018-FY2022). This latest MOU represents a 27% increase in the U.S. commitment to Jordan above the previous iteration and is the first five-year MOU with the kingdom. The previous two MOU agreements had been in effect for three years.

Economic Assistance

The United States provides economic aid to Jordan for (1) budgetary support (cash transfer), (2) USAID programs in Jordan, and (3) loan guarantees. The cash transfer portion of U.S. economic assistance to Jordan is the largest amount of budget support given to any U.S. foreign aid recipient worldwide.50 U.S. cash assistance is provided to help the kingdom with foreign debt payments, Syrian refugee support, and fuel import costs (Jordan is almost entirely reliant on imports for its domestic energy needs). According to USAID, ESF cash transfer funds are deposited in a single tranche into a U.S.-domiciled interest-bearing account and are not commingled with other funds.51

USAID programs in Jordan focus on a variety of sectors including democracy assistance, water conservation, decentralization, and education (particularly building and renovating public schools). In the democracy sector, U.S. assistance has supported capacity-building programs for the parliament's support offices, the Jordanian Judicial Council, the Judicial Institute, and the Ministry of Justice. The International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute also have received U.S. grants to train, among other groups, the Jordanian Independent Election Commission (IEC), Jordanian political parties, and members of parliament. In the area of decentralization, Chemonics International is USAID's primary U.S. partner in implementing the Cities Implementing Transparent, Innovative, and Effective Solutions (CITIES) project, which aims to improve how Jordanian municipalities delivers core services.52 In the water sector, the bulk of U.S. economic assistance is devoted to optimizing the management of scarce water resources. As mentioned above, Jordan is one of the most water-deprived countries in the world.53 USAID subsidizes several waste treatment and water distribution projects in the Jordanian cities of Amman, Mafraq, Aqaba, and Irbid.54

U.S. Sovereign Loan Guarantees (or LGs) allow recipient governments (in this case Jordan) to issue debt securities that are fully guaranteed by the United States government in capital markets,55 effectively subsidizing the cost for governments of accessing financing. Since 2013, Congress has authorized56 LGs for Jordan and appropriated $413 million in ESF (the "subsidy cost") to support three separate tranches, enabling Jordan to borrow a total of $3.75 billion at concessional lending rates.57

Humanitarian Assistance for Syrian Refugees in Jordan

The U.S. State Department estimates that, since large-scale U.S. aid to Syrian refugees began in FY2012, it has allocated more than $1.3 billion in humanitarian assistance from global accounts for programs in Jordan to meet the needs of Syrian refugees and, indirectly, to ease the burden on Jordan.58 U.S. humanitarian assistance is provided both as cash assistance to refugees and through programs to meet their basic needs, such as child health care, education, water, and sanitation.

Military Assistance

U.S.-Jordanian military cooperation is a key component in bilateral relations. U.S. military assistance is primarily directed toward enabling the Jordanian military to procure and maintain U.S.-origin conventional weapons systems.59 According to the State Department, Jordan receives one of the largest allocations of International Military Education and Training (IMET) funding worldwide, and IMET graduates in Jordan include "King Abdullah II, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Vice Chairman, the Air Force commander, the Special Forces commander, and numerous other commanders."60

Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and DOD Security Assistance

FMF overseen by the State Department is designed to support the Jordanian armed forces' multiyear (usually five-year) procurement plans, while DOD-administered security assistance supports ad hoc defense systems to respond to immediate threats and other contingencies. FMF may be used to purchase new equipment (e.g., precision-guided munitions, night vision) or to sustain previous acquisitions (e.g., Blackhawk helicopters, AT-802 fixed-wing aircraft). FMF grants have enabled the Royal Jordanian Air Force to procure munitions for its F-16 fighter aircraft and a fleet of 28 UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters.61

As a result of the Syrian civil war and U.S. Operation Inherent Resolve against the Islamic State, the United States has increased military aid to Jordan and channeled these increases through DOD-managed accounts. Although Jordan still receives the bulk of U.S. military aid through the FMF account, Congress has authorized defense appropriations to strengthen Jordan's border security. U.S. assistance has helped finance the creation of the Jordan Border Security System, an integrated network of guard towers, surveillance cameras, and radar to guard the kingdom's borders with Syria and Iraq.62 Since FY2015, total DOD security cooperation funding for Jordan has amounted to nearly 1 billion dollars.63

Excess Defense Articles

In 1996, the United States granted Jordan Major Non-NATO Ally (MNNA) status, a designation that, among other things, makes Jordan eligible to receive excess U.S. defense articles, training, and loans of equipment for cooperative research and development.64 In the last five years, excess U.S. defense articles provided to Jordan include three AH-1 Cobra Helicopters, 45 Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles (MRAPs), and M577A3 Tracked Command Post Carriers.65