Introduction

The retransmission of television signals to subscribers of cable, telephone company (telco), and satellite services is governed in part by the Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act Reauthorization Act of 2014 (STELA Reauthorization Act; P.L. 113-200). Some provisions of this law, which amended the Copyright Act of 1976 and the Communications Act of 1934, are set to expire at the end of 2019.1 If these provisions expire, about 870,000 households subscribing to satellite services might lose access to broadcast television programming. Moreover, about 87.4 million households subscribing to cable, telco, and/or satellite services might be more likely to see their viewing disrupted by disputes between the operators and television broadcasters than they would absent the expiring provisions.2

The television industry and consumer viewing habits have changed substantially since 2014. To provide context for the current debate, this report provides background information about how households receive television programming, how the television industry operates, and how the Copyright and Communications Acts determine what programs viewers receive. Finally, the report describes the impact of the expiring provisions on both consumers and industry participants, as well as the potential ramifications if Congress allows them to expire.

Background

A household may receive broadcast television programming through one or more of three methods:

- 1. by using an individual antenna that receives broadcast signals directly over the air from television stations;

- 2. by subscribing to a multichannel video programming distributor (MVPD), such as a cable or satellite provider or a telco, which brings the retransmitted signals of broadcast stations to a home through a copper wire, a fiber-optic cable, or a satellite dish installed on the premises; or

- 3. by using a high-speed internet (broadband) connection. A household may subscribe to a streaming service that includes broadcast television programming on an on-demand basis, or a "virtual MVPD" (vMVPD). A vMVPD aggregates prescheduled programming and packages it in a format that is accessible on devices with broadband connections.3

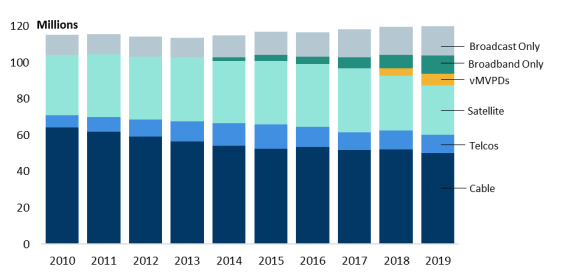

As Figure 1 indicates, the total number of U.S. households subscribing to an MVPD has declined over the past 10 years. In 2010, about 104.2 million households subscribed to an MVPD (cable, telco, or satellite provider), compared with about 87.4 million households in 2019. In place of MVPDs, an increasing number of households rely on video provided over broadband connections (including vMVPDs) or via over-the-air broadcast transmission.

Currently, two direct broadcast satellite providers—DIRECTV and DISH—offer video service to most of the land area and population of the United States.4 As of June 2019, DIRECTV had approximately 17.4 million U.S. subscribers, while DISH had approximately 9.5 million U.S. subscribers.5 Both have lost subscribers since September 2014, when DIRECTV had approximately 20.2 million U.S. subscribers and DISH had approximately 14.0 million U.S. subscribers.6

Broadcast Television Markets

Federal Communications Commission Licensing and Localism

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) licenses broadcast television station owners for eight-year terms to use the public airwaves, or spectrum, in exchange for operating stations in "the public interest, convenience and necessity," pursuant to Section 310(d) of the Communications Act.7 In 1952, the FCC formally allocated television broadcast frequencies among local communities.8 The basic purpose of the allocation plan was to provide as many communities as possible with sufficient spectrum to permit one or more local television stations "to serve as media for local self-expression."9

Television Communities vs. Local Television Markets

Until the mid-1960s, the television audience research firm the Nielsen Company restricted its measurement of television station viewership to the major metropolitan areas that were the first to have broadcast television stations.10 Among other factors, the station considers the estimated number of viewers it attracts with programs when determining the prices that it can charge advertisers. Thus, station viewership plays a significant role in a station's ability to generate revenue. After hearings in the House of Representatives produced accusations that stations licensed to large cities were pressuring the rating services not to measure audiences of stations licensed to smaller cities,11 Nielsen began to assign each U.S. county to a unique geographic television market in which Nielsen could measure viewing habits.12 Nielsen's construct, known as Designated Market Areas (DMAs), has been widely used to define local television markets since the late 1960s.13 The definitions of DMAs are important in determining which television broadcast signals an MVPD subscriber may watch.

Nielsen generally assigns each county to one of 210 DMAs based on the predominance of viewing of broadcast television stations in that county. In addition, Nielsen assigns each broadcast television station to a DMA. Nielsen bases each station's DMA on the home county of its FCC community of license.14 Stations seek to have their signals reach as many people as possible living within their DMAs. They generally have little incentive to reach viewers living outside their DMAs, as they are typically unable to charge advertisers for access to those viewers.

Broadcast stations' contractual agreements with television networks and other suppliers of programming generally give them the exclusive rights to air that programming within their DMAs. Advertisers use DMAs to measure television audiences and to plan and purchase advertising from stations to target viewers within those geographic regions.

Retransmission of Broadcast Signals via MVPDs

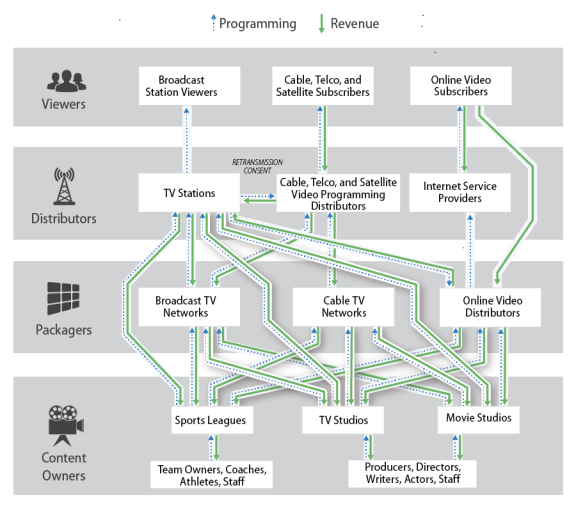

Figure 2 illustrates the relationships among viewers; broadcast television stations; and cable, telco, and satellite operators; cable and broadcast networks; and owners of television programming content.

|

|

Source: CRS. Notes: Many companies/entities fall into multiple categories, or have multiple operations within a category. Other owners of content not included in this diagram are songwriters and recording artists, who in turn have licensing agreements with the content owners pictured here. |

Related Communications Laws

Generally, subscribers to cable, telco, and satellite services may receive television stations located within their DMAs as part of their video packages. Whether or not subscribers do so, however, depends in part on the decisions of broadcast stations to require these services to retransmit their signals or to opt instead to negotiate for compensation. In addition, satellite operators may choose not to provide any local broadcast service in a particular DMA. The Communications Act gives broadcast stations and satellite operators the rights to make these choices.

Must Carry; Carry One, Carry All

Every three years, commercial broadcast television stations may choose to require cable, telco, and satellite operators to retransmit their signals.15 By statute, a cable operator or telco must carry the signals of all television stations seeking "must carry" status and assigned to the DMA in which the cable operator is located. Satellite operators are required to carry the signals of all stations assigned to a DMA that seek must carry status to viewers in that DMA, if they choose to carry the signal of at least one local television station in the market.16 Policymakers often call this provision "carry one, carry all." The applicability of these provisions to telcos is uncertain.17

Due in part to the carry one, carry all provision, DIRECTV has opted not to retransmit any local broadcast television stations in 12 DMAs. They are Alpena, MI; Bowling Green, KY; Caspar-Riverton, WY; Cheyenne, WY/Scottsbluff, NE; Grand Junction, CO; Glendive, MT; Helena, MT; North Platte, NE; Ottumwa, IA; Presque Isle, ME; San Angelo, TX; and Victoria, TX.18

Retransmission Consent

In lieu of choosing must carry status, commercial broadcasting stations may opt to seek compensation from cable, telco, and satellite operators for carriage of their signals in exchange for granting retransmission consent.19 In contrast to the must carry laws, which differ for cable and satellite operators, the retransmission consent laws apply to all MVPDs.

If a broadcast station opts for retransmission consent negotiations, MVPDs must negotiate with it for the right to retransmit its signal within the station's DMA. In addition, cable operators may negotiate with the station for consent to retransmit the station's signals outside of the station's DMA.20 However, the contracts that broadcast stations have with program suppliers, such as television networks, may limit the stations' ability to consent to the retransmission of their signals outside of their markets.21 Most television broadcast stations are part of a portfolio owned by broadcast station groups. Most cable systems are part of multiple-system operations owned by corporations. Negotiations over retransmission consent generally occur at the corporate level, rather than between an individual station and a local cable system.

Greater competition among MVPDs has increased the negotiating advantage of broadcast television stations since 1993, when they first had the right to engage in retransmission consent negotiations.22 At that time, large MVPDs refused to pay broadcast stations directly for retransmission rights.23 Instead, several broadcast networks negotiated on behalf of their affiliates for alternative forms of compensation. The networks sought carriage of new cable networks owned by their parent companies, and split the proceeds they received from the cable networks with the affiliates.

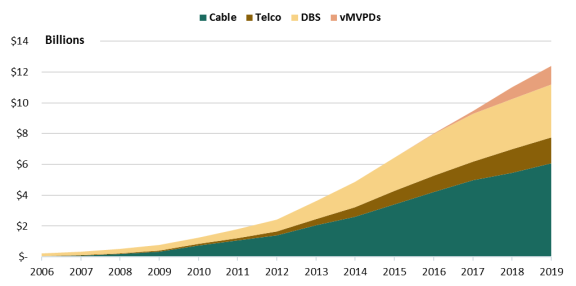

As satellite operators and telcos entered the market in competition with cable operators, broadcast stations could encourage the cable subscribers to switch, and vice versa. Broadcast stations began to demand cash in exchange for carriage. As Figure 3 indicates, the total amount of retransmission fees paid by MVPDs has increased from $0.21 billion in 2006 to $12.38 billion in 2019. The 2019 totals included fees paid by vMVPDs, which did not exist in 2006.

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from S&P Global, "Broadcast Retrans and Virtual Multichannel Sub Carriage Fees Summary: 2011-2024." Notes: "DBS" refers to direct broadcast satellite services. "Telco" refers to telephone companies that offer video service. |

Related Copyright Laws

Generally, copyright owners have the exclusive legal right to "perform"24 publicly their works, and, as is the case with online distribution of their programs, to license their works to distributors in marketplace negotiations.25 The Copyright Act limits these rights for owners of programming contained in retransmitted broadcast television signals. The Copyright Act guarantees MVPDs the right to perform publicly the copyrighted broadcast television programming, as long as they abide by FCC regulations and pay royalties to content owners at rates set and administered by the government.26 In some instances, MVPDs need not pay content owners at all, because Congress set a rate of $0.

The Copyright Act contains three statutory copyright licenses governing the retransmission of local and distant television broadcast station signals. Local signals are broadcast signals retransmitted by MVPDs within the local market of the subscriber ("local-into-local service"). Distant signals are broadcast signals imported by MVPDs from outside a subscriber's local area.

- 1. The cable statutory license, codified in Section 111, permits cable operators to retransmit both local and distant television station signals.27 This license relies in part on former and current FCC rules and regulations as the basis upon which a cable operator may transmit distant broadcast signals.

- 2. The local satellite statutory license, codified in Section 122, permits satellite operators to retransmit local signals on a royalty-free basis. To use this license, satellite operators must comply with the rules, regulations, and authorizations established by the FCC governing the carriage of local television signals.

- 3. The distant satellite statutory license, codified in Section 119, permits satellite operators to retransmit distant broadcast television signals. Congress has renewed this provision in five-year intervals. In 2004, Congress inserted a "no distant if local" provision, which prohibits satellite operators from importing distant signals into television markets where viewers can receive the signals of broadcast network affiliates over the air. Section 119 sunsets on December 31, 2019.

Under the statutory license, cable, telco, and satellite operators make royalty payments every six months to the U.S. Copyright Office, an agency of the Library of Congress. The head of this office, the Register of Copyrights, places the money in an escrow account and maintains the "Statement of Account" that each operator files. Congress has charged the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), which is composed of three administrative judges appointed by the Librarian of Congress,28 with distributing the royalties to copyright claimants. It also has the task of adjusting the rates at five-year intervals, and annually in response to inflation. For additional information about these licenses, see CRS Report R44473, What's on Television? The Intersection of Communications and Copyright Policies, by Dana A. Scherer.

Expiring Provisions of STELAR

Through a series of laws enacted over the last 30 years, Congress created new sections or modified existing sections of the Copyright Act and the Communications Act to regulate the satellite retransmission of broadcast television and to encourage competition between satellite and cable operators. Congress began the process with the enactment of the Satellite Home Viewer Act of 1988 (SHVA; P.L. 100-667), and most recently amended the process with the enactment of the STELA Reauthorization Act of 2014.

|

Statute |

Year Enacted |

Highlights |

|

Satellite Home Viewer Act of 1988 (SHVA; P.L. 100-667) |

1988 |

Established six-year compulsory copyright license to allow satellite operators to carry broadcast programming from distant network affiliates (of ABC, CBS, and NBC—similar to definition for cable compulsory licensing) and superstations,a generally to residents in rural areas using home satellite dishes. Entitled network stations to higher royalty rates than "non-network" stations. |

|

Satellite Home Viewer Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-369) |

1994 |

Renewed compulsory license for an additional five years. Broadened definition of network station to include PBS and FOX affiliates. Limited satellite importation of broadcast television signals to "unserved households" (i.e., those unable to receive over-the-air signals). Placed burden of proof on satellite operators to demonstrate that households are eligible to receive distant broadcast signals. Broadened definition of satellite carriers to include Direct Broadcast Satellite services (DISH and DIRECTV), scheduled to begin operating in 1994. |

|

Satellite Home Viewer Improvement Act of 1999 (SHVIA; P.L. 106-113) |

1999 |

Brought satellite and cable services closer to regulatory parity. Created permanent legal and regulatory framework permitting satellite operators to retransmit local broadcast signals ("local-into-local" service). In contrast to nationwide "must carry" provisions applying to cable operators, applied "must carry" provisions to satellite operators on a market-by-market basis ("carry one, carry all"). Allowed satellite operators same rights as cable operators to deliver local stations to commercial establishments. Imposed five-year good faith retransmission consent obligations on broadcasters, subject to competitive marketplace conditions. Renewed compulsory license for an additional five years. Expanded definition of "unserved households" to include (1) those who obtain a waiver from a local network affiliate to receive a distant signal; (2) those whose distant signals were terminated after Jul. 11, 1998, and before Oct. 31, 1999, pursuant to a court injunction, or received such service on Oct. 31, 1999; (3) operators of recreational vehicles and trucks; and/or (4) those subscribing to C-Band service prior to Oct. 31, 1999.b |

|

Satellite Home Viewer Extension and Reauthorization Act of 2004 (SHVERA; P.L. 108-447) |

2004 |

Renewed compulsory license for an additional five years. Brought satellite and cable services nearer to regulatory parity. Created a "local" copyright license that gave satellite carriers the option to offer subscribers "significantly viewed" signals from an adjacent DMA and granted them retransmission rights for the signals. Restricted satellite operators from offering distant signals to customers in a market where they are also offering the local affiliate of the same network (the "no distant where local" rule). Expanded definition of unserved household to include those who receive network programing in local market via digital multicast signal only. Permitted satellite operators to transmit superstations to commercial establishments, similar to cable operators. Made five-year good faith bargaining requirements (subsequently renewed) for retransmission consent negotiations reciprocal between MVPDs and broadcast stations. |

|

Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act of 2010 (STELA; P.L. 111-175) |

2010 |

Provided that satellite operators may offer "significantly viewed" stations in high definition format only if they provide local stations in high-definition format as well. Modified criteria for determining satellite subscribers' eligibility to receive distant signals (i.e., "unserved households") to account for broadcast stations' conversion from analog to digital signals. Allowed DISH to continue to use statutory license in exchange for providing local-into-local service in all 210 DMAs, notwithstanding court injunction. Some of the DMAs are "short markets," that is, markets in which a local broadcaster does not offer programming from one for more of the four major broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC). |

|

STELA Reauthorization Act of 2014 ( P.L. 113-200) |

2014 |

Extended rules for modification of cable operators' "local markets" to satellite operators, and directs the FCC to factor consumers' access to in-state programming when modifying markets. Eliminated FCC rules barring MVPDs from deleting broadcasters' programming or changing channel positions during "sweeps" weeks. Prohibited separately owned broadcast stations from jointly negotiating retransmission consent in same market. Repealed FCC ban on integration of navigation and security functions within cable set-top boxes effective December 4, 2015. |

Sources: Excerpted by CRS from Testimony of Eloise Gore, Associate Bureau Chief, Enforcement Bureau, FCC, in U.S. Congress, House Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Satellite 101, hearings, 113th Cong., 1st sess., February 13, 2013, H.Hrg. 113-4 (Washington, DC: GPO, 2013) pp. 11-15, (describing the enactment of SHVA in 1988 and the subsequent reauthorizations through 2010); U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Satellite Compulsory License Extension Act of 1994, committee print, 103rd Congress, 2nd session, October 7, 1994, 103-407 (Washington: GPO, 1994); U.S. Congress, House Committee on Commerce, Intellectual Property and Communications Reform Act of 1999, committee print, 106th Congress, 1st session, November 9, 1999, 106-464 (Washington: GPO, 1999); U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Satellite Home Viewer Update and Reauthorization Act of 2009, committee print, 111th Cong., 1st session, October 28, 2009, H.Prt. 111-319 (Washington: GPO, 2009), describing provisions adopted in STELA. Federal Communications Commission, "In the Matter of Amendment of the Commission's Rules Related to Retransmission Consent, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, FCC 14-29," 29 FCC Record 3341 March 31, 2014 (describing satellite television laws implemented by the FCC).

Notes:

a. The Communications Act identifies a class of "nationally distributed superstations" (47 U.S.C. §339(d)(2)). These are independent stations whose broadcast signals are retransmitted by satellite to cable television and satellite operators for distribution throughout the United States. The MVPDs effectively treat the nationally distributed superstations as cable networks rather than local broadcast television stations. As of 2019, there are five superstations: KWGN (Denver), WPIX (New York), KTLA (Los Angeles), WSBK (Boston), and WWOR (New York/New Jersey).

b. In this context, the term C-band service means a service that is licensed by the FCC and operates in the Fixed Satellite Service under part 25 of Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations. 17 U.S.C. §119(a)(2)(B)(iii)(II). For more information about this provision, see "Expiring Provision of Copyright Act."

Expiring Provision of Copyright Act

Certain provisions in STELA are set to expire on December 31, 2019. The expiring copyright provision is Section 119 of the Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. §119). This section enables satellite operators to obtain rights to copyrighted programming carried by distant broadcast network affiliates, superstations, and other independent stations. Under this regime, the satellite operators submit a statement of account and pay a statutorily determined royalty fee to the U.S. Copyright Office on a semiannual basis, avoiding the transactions costs of negotiating with each individual copyright holder.29

A satellite operator is allowed to retransmit the signals of up to two distant stations affiliated with a network (ABC, CBS, FOX, NBC, or PBS) to a subset of subscribing households that are deemed "unserved" with respect to that network. The "unserved household" limitation does not apply to the retransmission of superstations. Pursuant to Section 119, satellite operators may retransmit superstations to commercial establishments as well as households.

Section 119 specifies five different categories of unserved households:

- 1. a household located too far from a broadcast station's transmitter to receive signals using an antenna; [Section 119(d)(10)(A)]

- 2. a household that has received written consent from a local network affiliate to receive a distant signal;30 [Section 119(d)(10)(B)]

- 3. a household that—even if it could receive a local broadcast signal over the air—nevertheless received a satellite retransmission of a distant signal on October 31, 1999, or whose satellite provider terminated the distant signal retransmission after July 11, 1998, and before October 31, 1999, pursuant to court injunction;31 [Section 119(d)(10)(C)]

- 4. operators of recreational vehicles and commercial trucks who have complied with certain documentation requirements;32 [Section 119(d)(10)(D)]

- 5. a household that has received delivery of distant network signals via C-band before October 31, 1999.33 [Section 119(d)(10)(E)]

In 2010, Congress provided an incentive for DISH to offer local-into-local service in all 210 markets with the enactment of STELA.34

In 2006, a Florida district court had found that DISH, then known as EchoStar Communications, had a national pattern of significant violations of the Section 119 license. The U.S. Court of Appeals directed the district court to enjoin DISH from using the Section 119 license.35 In response, Congress restored DISH's ability to provide subscribers distant signals if, and only if, it provided local-into-local service in all 210 DMAs in the country.36 According to the House Judiciary Committee, this change was intended to prompt DISH to provide local-into-local service via an incentive-based system. It added that the inducement would benefit rural consumers who "live in markets that are often not served by cable television and not deemed sufficiently lucrative by satellite companies to justify the expense of launching local into local service."37 Several members of the committee, however, questioned this approach in a section of the report entitled "Additional Views." They stated that

While we share the goal of enabling all Americans to view local television programming via satellite, we question the proposition that the best available means to provide such an incentive is to relieve DISH Network of the foreseeable results of its persistent, determined, unlawful conduct. Rather than crafting a proposal designed to benefit one satellite carrier, a better approach would be to provide an incentive to both national satellite carriers to enter the remaining markets. Such an approach would [respect] the judiciary's independence in administering, without prejudice, the laws Congress enacts....38

Section 119(g)(2)(A) directs a court issuing an injunction against a satellite carrier to lift such an injunction, upon request by the satellite carrier, to the extent necessary to allow the carrier to retransmit distant signals in "short markets." Section 119(g)(2)(E) defines a "short market" as a "local market in which programming of one of the four most widely viewed television networks nationwide as measured on the date of the enactment of this subjection is not offered on the primary stream transmitted by any local television broadcast station."

Use of Section 119 License

In March 2019, the chairman and ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, Representatives Jerrold Nadler and Doug Collins, respectively, asked DIRECTV's parent company, AT&T, and DISH for data regarding the number of subscribers who receive distant network signals under each of the statutory provisions defining an "unserved household."39 Both AT&T and DISH declined to answer, stating that the answers were competitively sensitive.40 The companies stated that combined, they use the distant signal license to provide network television programming to more than 870,000 households. AT&T stated that it serves subscribers through all of the unserved household categories, except for the C-Band exemption.

AT&T also stated that DIRECTV uses the statutory license to provide network programming in some short markets. As described in "Must Carry; Carry One, Carry All" however, DIRECTV does not provide local-into-local service in 12 DMAs. DISH stated that it provides local service in all 210 markets, and listed the stations it imports into each short market.41 DISH generally imports signals from stations located in the same states as its subscribers in short markets. In Glendive, MT, it imports signals of ABC and FOX stations assigned to the Rapid City, SD, DMA. Other short markets include counties from multiple states. The Parkersburg, WV, DMA contains one Ohio county, and the Harrisonburg, VA, DMA contains one West Virginia county.42 In Parkersburg, DISH imports the signal of an ABC station assigned to the Charleston, WV, DMA. In Harrisonburg, DISH imports the signal of an NBC station assigned to the Washington, DC, DMA.

Revenues Collected by Copyright Office

In May 2019, Representatives Nadler and Collins requested that the U.S. Copyright Office provide its views about the status and usage of the Section 119 license. They also asked for the Copyright Office's views on reauthorization of the license.43 In June 2019, the Register of Copyrights and Director of the U.S. Copyright Office, Karyn A. Temple, responded by recommending that Congress allow Section 119 to expire at the end of 2019. She stated that, "[r]oyalties paid under Section 119 have plummeted over the last five years," [that is, since Congress reauthorized this provision in 2014] and usage of this compulsory license over the last five years has "dropped dramatically." As Table 2 indicates, over the last five years, the total number of Section 119 royalties collected by the Copyright Office declined by 89%. Among the reasons she cited for the decline are a drop in the number of distant network stations carried and the conversion of non-network superstations, such as WGN, to cable networks. In addition, as Figure 1 indicates, the total number of households subscribing to satellite television has declined, from about 34.4 million in 2014 to 27.3 million in 2019.44

|

Satellite Provider |

Jan.–Jun. 2014 |

Jan.–Jun. 2019 |

|

DIRECTV |

$26,649,170 |

$2,303,988 |

|

DISH |

$15,102,510 |

$2,174,319 |

|

DISH Puerto Rico |

$299,308 |

$707 |

|

Distant Networks, LLC |

$58,936 |

— |

|

Total |

$42,109,924 |

$4,479,015 |

Source: CRS analysis of 2014 and 2019 statements of account filed by satellite operators.

Notes: Numbers exclude $725 filing fee for each provider for each six-month period. The parent company of Distant Networks, LLC, which offered C-Band satellite television service, ceased operation in February 2014. Internet Archive, "Who is AllAmericanDirect.com?," https://web.archive.org/web/20101127064020/https://mydistantnetworks.com/aboutus.php. Internet Archive, "My DistantNetworks," https://web.archive.org/web/20140516214600/http://allamericandirect.com/.

Potential Transition Period for Marketplace Negotiations

In November 2019, Senator Lindsey O. Graham, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent letters to all four major commercial broadcast networks to inquire about how the networks would enable satellite subscribers to continue to receive their programming during 2020, should Congress allow the Section 119 license to expire in 2019.45 Senator Graham sought answers to the following questions:

- 1. Will their respective networks provide a one-year license to satellite providers for the shows they own in exchange for a "market-by-market" usage fee from each provider, including for use by long-distance truckers and RV owners, who also rely on the license?

- 2. Will the network agree, for that transition period, to charge a rate comparable to the compulsory license rate charged by the Copyright Royalty Board for 2018?

- 3. Will the network work with its affiliates to negotiate during this transition year, on a carriage agreement for full local-into-local carriage on both DISH and DIRECTV beginning in January 1, 2021?

- 4. For areas without local affiliates, will the network commit to negotiating with DISH and DIRECTV on a carriage agreement beginning no later than January 1, 2021?

- 5. Will the network keep the committee informed of its progress toward such agreements?

News reports indicate the networks have agreed to these commitments.46

Expiring Provisions of Communications Act

Several provisions of the Communications Act are also set to expire at the end of 2019. Some of those provisions cross-reference Section 119 of the Copyright Act. In some instances, the cross-references relate to definitions. In other instances, they relate to communications policies and FCC regulations. Other provisions relate to retransmission consent negotiations between broadcast television stations and all MVPDs—including cable operators as well as satellite operators.

Cross-References to Section 119 of Copyright Act

Definitions

Sections 338(k)(7), 339(c)(5), and 339(d)(4) of the Communications Act [47 U.S.C. §§338(k)(7), 339(c)(5), 339(d)(4)] cross-reference Section 119 of the Copyright Act [17 U.S.C. §119(d)] in their definitions of a "satellite carrier." Likewise, Section 628(i)(4) of the Communications Act [47 U.S.C. §548(i)(4)] refers to Section 119 of the Copyright Act in its definition of a "satellite broadcast programming vendor."

Section 338(k)(8) cross-references 47 U.S.C. §119(d) in its definition of a "secondary transmission." Sections 339(d)(2) cross-references Section 119 of the Copyright Act [17 U.S.C. §119] to define a superstation, and 339(d)(3) cross-references Section 119 of the Copyright Act [17 U.S.C. §119(d)] to define a "network station."

Communications Policies and FCC Rules

Section 325(b)(2)(B) and (C) of the Communications Act [47 U.S.C. §325(b)(2)(B)-(C)] permit a satellite operator to retransmit distant broadcast signals of stations without first seeking retransmission consent from those stations, if the satellite operator is retransmitting the signals pursuant to Section 119 of the Copyright Act. Section 325(b)(2)(C) is scheduled to expire on December 31, 2019.

Section 338(a)(3) of the Communications Act [47 U.S.C. §338(a)(3)] states that a low-power station whose signals are retransmitted by a satellite operator pursuant to Section 119 of the Copyright Act [17 U.S.C. §119(a)(14)] is not entitled to must carry rights.

Section 339(a)(1)(A) of the Communications Act (47 U.S.C. §339) permits satellite operators to retransmit the signals of a maximum of two affiliates of the same network in single day to households located outside of those stations' DMAs, subject to Section 119 of the Copyright Act. Section 339(a)(1)(B) states that satellite operators may retransmit local broadcast signals under 17 U.S.C. §122 in addition to any distant signals they may retransmit under Section 119 of the Copyright Act. Section 339(a)(2)(A) discusses rules for retransmitting broadcast station signals to satellite subscribers meeting the "unserved household" definition under Section 119 of the Copyright Act [17 U.S.C. §119(d)(10)(C)]. Section 339(a)(2)(D) and (c)(4)(A), in describing households eligible to receive distant signals, cross-reference the "unserved household" definition under 17 U.S.C. §119(d)(10)(A). Section 339(a)(2)(G) states that "this paragraph shall not affect the ability to receive secondary transmissions ... as an unserved household under section 119(a)(12) of title 17, United States Code." Section 339(c)(2) describes the process under which a household may seek a local affiliate's permission to receive a distant signal, and therefore qualify as an "unserved household" under Section 119 of the Copyright Act [17 U.S.C. §119(d)(10)(B)].

Section 340(3)(2) of the Communications Act [47 U.S.C. §340] states that a satellite operator that retransmits a distant broadcast signal pursuant to 17 U.S.C. §119 need not comply with FCC regulations that would otherwise require the satellite operator to black out certain programs of that station.47

Section 342 of the Communications Act [47 U.S.C. §342] cross-references Section 119 of the Copyright Act [17 U.S.C. §119(g)(3)(A)(iii)], and describes the process through which DISH may obtain a certification from that FCC demonstrating that it is providing local-into-local service in all 210 DMAs. Under 17 U.S.C. §119(g)(3), upon presenting this certification, among other documents, to the Florida district court that had enjoined DISH from using the Section 119 license, DISH would be eligible to use it. (See "Expiring Provision of Copyright Act.")

Good Faith Requirements for Retransmission Consent Negotiations

Section 325(b)(3)(C) of the Communications Act (47 U.S.C. §325(b)(3)(C)) prohibits broadcast stations from engaging in exclusive contracts for carriage. This section also requires both broadcast stations and MVPDs to negotiate retransmission in "good faith," subject to marketplace conditions. Moreover, according to this section, the coordination of negotiations among separately owned television broadcast stations within the same DMA is a per se violation of the good faith standards. The good faith provisions is scheduled to expire on January 1, 2020.

The FCC implements the good faith negotiation statutory provisions through a two-part framework.48 First, the FCC has a list of nine good faith negotiation standards. The FCC considers a violation of any of these standards to be a per se breach of the good faith negotiation obligation.49 Second, the FCC may determine that based on the "totality of circumstances," a party has failed to negotiate retransmission consent in good faith. Under this standard, a party may present facts to the FCC that, given the totality of circumstances, reflect an absence of a sincere desire to reach an agreement that is acceptable to both parties and thus constitute a failure to negotiate in good faith.

Complaints Regarding Good Faith Standard Violations

Over the last 13 years, both broadcast television station owners and MVPDs have filed complaints with the FCC that their counterparty has failed to negotiate in good faith. In some instances, the FCC has found that the complaint lacked validity.50 In 2016, the FCC reached a consent decree with Sinclair after completing an investigation.51 In other instances, the FCC has monitored retransmission consent negotiations even when a party has not filed a complaint.52 In some cases, stations and/or MVPDs withdraw complaints from the FCC after reaching retransmission consent agreements.53 In November 2019, the FCC found that seven different station group owners had violated the per se good faith negotiation standards with respect to AT&T, and directed the parties to commence good faith negotiation.54 The subscribers to AT&T's video subscription services—U-Verse and DIRECTV—have lacked access to those station groups' broadcast signals since June 2019 due to the retransmission consent impasse.

Good Faith Provisions and FCC Media Ownership Rules

Section 325(b)(3)(C)(iv) directs the FCC to adopt rules that prohibit the coordination of negotiations among separately owned television broadcast stations within the same DMA. Unlike the good faith provisions of the Communications Act, the prohibition on coordination is permanent. The FCC, however, has adopted a rule declaring such behavior a per se violation of its good faith negotiation standards.55 Thus, if Congress does not renew the good faith provisions, the FCC may need to adopt a separate rule to comply with Section 325(b)(3)(C)(iv).

In a related matter, the FCC's rules regarding both the number of stations one entity may own within a DMA and the attribution of that ownership have been in flux. Currently, the FCC's ownership rules generally prohibit one company from owning two of the top four ranked stations (usually, stations affiliated with the ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC networks) within the same DMA.56 In 2016, the FCC adopted rules specifying that it would consider one television station that sells more than 15% of the weekly advertising time on a competing local broadcast television station to be under common ownership or control, for the purposes of enforcing its media ownership rule.57 In 2017, however, the FCC eliminated this rule as part of a reconsideration of its 2016 decision.58 In September 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit vacated and remanded the FCC's 2017 reconsideration.59 In November 2019, the FCC petitioned the full court to rehear the case.60

The Third Circuit did not specify whether the FCC's attribution rules adopted in 2016 remain in effect while it considers whether to rehear the case. If the 2016 rules are in effect, then stations that jointly engage in the selling of advertising time may not jointly engage in retransmission consent negotiations, if common ownership would violate the FCC's media ownership rules.61

Legislation

In November 2019, Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee Chairman Roger Wicker introduced the Satellite Television Access Reauthorization Act of 2019 (STAR Act of 2019; S. 2789). This bill would reauthorize the expiring provisions of both the Copyright and Communications Acts for five years.

Also in November 2019, the House Energy and Commerce Committee ordered H.R. 5035, the Television Viewer Protection Act of 2019, as amended by the committee, to be reported to the House. The bill would reauthorize the good faith provisions of the Communications Act permanently.

In addition, the bill would permit smaller cable, telco, and/or satellite operators with fewer than 500,000 subscribers to negotiate collectively with large broadcast station groups reaching 20% or more of U.S. households until January 1, 2025. This provision would not take effect until January 1 of the calendar year after the calendar year in which Congress enacts the bill.

H.R. 5035 would also tie the expiration of Section 325(b)(2)(B) and (C) of the Communications Act [47 U.S.C. §325(b)(2)(B)-(C)], which permits a satellite operator to retransmit distant broadcast signals of stations without first seeking retransmission consent from those stations, to the expiration date of Section 119 of the Copyright Act.

Additional provisions in the bill relating to transparency in billing for video and internet services are beyond the scope of this report.

In November 2019, the House Judiciary Committee ordered H.R. 5140, the Satellite Television Community Protection and Promotion Act of 2019, as amended by the committee, to be reported to the House. This bill would permanently extend Section 119 of the Copyright Act, but limit the scope of "unserved households" eligible to receive the distant signals. The bill would continue to allow operators of recreational vehicles and commercial trucks who have complied with certain documentation requirements to receive distant the distant signals. It would also allow households in short markets to receive distant network signals when local signals are unavailable, that is, in short markets. For the households currently receiving distant signals pursuant to Section 119 of the Copyright Act, the bill would provide satellite operators with a limited extension of the license for 120 days.

The bill would require all satellite providers, including DIRECTV, to offer local service in all 210 DMAs, in order to use the distant signal compulsory license. DIRECTV would have 180 days from the bill's enactment to deliver those signals. If the company files a notice to the Copyright Office that it is making a good faith effort to deliver those signals, it may have unlimited automatic 90-day extensions. If broadcast stations assert DIRECTV is not making a good faith effort, the bill would give them a private right of action in civil court. The bill also specifies that satellite operators would not lose access to the distant compulsory license if their failure to deliver local signals in all 210 markets is due to a retransmission consent impasse.