Introduction

Congressional commissions are formal groups established by Congress to provide independent advice, to make recommendations for changes in public policy, to study or investigate a particular problem or event, or to commemorate an individual, group, or event. Usually composed of policy experts chosen by Members of Congress and/or officials in the executive branch, commissions may hold hearings, conduct research, analyze data, investigate policy areas, or make field visits as they perform their duties. Most commissions complete their work by delivering their findings, recommendations, or advice in the form of a written report to Congress. Occasionally, legislation submitted by commissions will be given "fast track" authority in Congress.

Although no legal definition exists for what constitutes a "congressional commission," in this report, a congressional commission is defined as a multimember independent entity that (1) is established by Congress, (2) exists temporarily, (3) serves in an advisory capacity, (4) is appointed in part or whole by Members of Congress, and (5) reports to Congress. These five characteristics effectively serve to differentiate a congressional commission from a presidential commission, an executive branch commission, or other bodies with "commission" in their names. Over 150 congressional commissions have been established since 1989.

Throughout American history, Congress has found commissions to be useful tools in the legislative process,1 and legislators continue to use them today. By establishing a commission, Congress can potentially provide a highly visible forum for important issues and assemble greater expertise than may be readily available within the legislature. Complex policy issues can be examined over a longer time period and in greater depth than may be practical for legislators. The nonpartisan or bipartisan character of most congressional commissions may make their findings and recommendations more politically acceptable, both in Congress and among the public. Conversely, some have expressed concerns that congressional commissions can be expensive, are often formed to take difficult decisions out of the hands of Congress, and are mostly ignored when they report their findings and recommendations.

Congressional commissions can be categorized as either policy commissions or commemorative commissions. Policy commissions generally study a particular public policy problem (e.g., the United States Commission on North American Energy Freedom),2 or investigate a particular event (e.g., the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States).3 Policy commissions typically report their findings to Congress along with recommendations for legislative or executive action. Commemorative commissions, such as the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission,4 are often tasked with planning, coordinating, and overseeing celebrations of people or events, often in conjunction with milestone anniversaries.5

The temporary status of congressional commissions and their often short time horizons make it important that legislators construct statutes with care. Statutes establishing congressional commissions generally include language that states the mandate of the commission, provides a membership structure and appointment scheme, defines member compensation and other benefits, outlines the commission's duties and powers, authorizes funding, and sets a termination date for the commission.

A variety of options are available for each of these organizational choices. Legislators can tailor the composition, organization, and arrangements of a commission, based on particular goals. As a result, individual commissions often have organizational structures and powers quite different from one another.

Defining Congressional Commission

In the past, confusion has arisen over whether particular entities are "congressional commissions." There are several reasons for this confusion. First, the term congressional commission is not defined by law; observers might disagree as to whether an individual entity should be characterized as such. Second, many different entities within the federal government have the word "commission" in their name, such as regulatory commissions, presidential advisory commissions, and advisory commissions established in executive agencies.6 Conversely, some congressional commissions do not have the word "commission" in their name; instead, they are designated as boards, advisory panels, advisory committees, task forces, or by other terms.

In this report, a congressional commission is defined as a multimember independent entity that (1) is established by Congress, (2) exists temporarily, (3) serves in an advisory capacity, (4) is appointed in part or whole by Members of Congress, and (5) reports to Congress. This definition differentiates a congressional commission from a presidential commission, an executive branch commission, or other bodies with "commission" in their names, while including most entities that fulfill the role commonly perceived for commissions: studying policy problems and reporting findings to Congress.7 Each of these characteristics is discussed below.

Independent Establishment by Congress

Congress usually creates congressional commissions by statute.8 Not all statutorily established advisory commissions, however, are congressional commissions. Congress may also statutorily establish executive branch advisory commissions. Conversely, not all federal advisory commissions are established by Congress. The President, department heads, or individual agencies may also establish commissions under various authorities.9

Congressional commissions are also generally independent of Congress in function. This characteristic excludes commission-like entities established within Congress, such as congressional observer groups, working groups, and ad hoc commissions and advisory groups created by individual committees of Congress under their general authority to procure the "temporary services" of consultants to "make studies and advise the committee," pursuant to 2 U.S.C. §72a.10

Temporary Existence

Congressional commissions are established to perform specific duties, with statutory termination dates linked to task completion. This restriction excludes entities that typically serve an ongoing administrative purpose, do not have statutory termination dates, and do not produce reports, such as the House Office Building Commission11 or Senate Commission on Fine Art.12 Also excluded are entities that serve ongoing diplomatic or interparliamentary functions, such as the U.S. Group to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly,13 or the Canada-United States Interparliamentary Group.14 Finally, Congress has created a number of boards to oversee government entities, such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Council15 and the John F. Kennedy Center Board of Trustees.16 Although these entities could arguably be considered congressional commissions, their lifespan, purpose, and function differ from temporary congressional commissions.

Advisory Role

Unlike regulatory commissions, congressional commissions are not typically granted administrative authority, and they usually lack the power to implement their findings or recommendations. Instead, advisory commissions typically produce reports that present their findings and offer recommendations for either legislative or executive action.

Inclusion of Members in the Appointment Process

Congressional commissions provide that Members of Congress, particularly the leadership, be intimately involved in the appointment process, either through direct service on a commission, or by appointing or recommending candidates for membership.17

Reporting Requirements

Congressional commissions are usually required to submit their reports to Congress, or to Congress and the President. Other advisory commissions, such as presidential or executive branch commissions, typically submit their reports only to the President or an agency head.

Types of Congressional Commissions

Congressional commissions can generally be placed into one of two categories: policy commissions and commemorative commissions. Most congressional commissions are policy commissions, temporary bodies that study particular policy problems and report their findings to Congress or review a specific event. Other commissions are commemorative commissions, entities established to commemorate a person or event, often to mark an anniversary. These categories are not mutually exclusive. A commission can perform policy and commemorative functions in tandem.

Policy Commissions

The vast majority of congressional commissions are established to study, examine, investigate, or review a particular policy problem or event. For example, policy commissions have focused on the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction,18 motor fuel tax enforcement,19 threats to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) attacks,20 and the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.21

Commemorative Commissions

Congress also creates commemorative commissions. These commissions most often commemorate an individual, group, or event. In some circumstances, commemorative commissions have also been tasked with the creation of national memorials in the District of Columbia.

For more information on commemorative commissions, see CRS Report R41425, Commemorative Commissions: Overview, Structure, and Funding, by Jacob R. Straus.

Potential Value of Congressional Commissions

Throughout American history, Congress has found commissions to be useful tools in the legislative process. Commissions may be established to, among other things, cope with increases in the scope and complexity of legislation, forge consensus, draft bills, promote inter-party communication, address issues that do not fall neatly within the jurisdictional boundaries of congressional committees, and bring together recommendations.22 These goals can be grouped into five categories: expertise, political complexity, consensus building, nonpartisanship, solving collective action problems, and visibility.

Obtaining Expertise

Congress may choose to establish a commission when legislators and their staffs do not currently have sufficient knowledge or expertise in a complex policy area,23 or when an issue area is sufficiently complex that engaging noncongressional experts could aid in policy development.24 By assembling experts with backgrounds in particular policy areas to focus on a specific mission, legislators might efficiently obtain insight into complex public policy problems.25 Further, a commission can devote itself to a particular issue full time, and can focus on an individual problem without distraction.26

Overcoming Political Complexity

Complex policy issues may also create institutional problems because they do not fall neatly within the jurisdiction of any particular committee in Congress.27 By virtue of their ad hoc status, commissions may circumvent such issues. Similarly, a commission may allow particular legislation or policy solutions to bypass the traditional development process in Congress, potentially removing some of the impediments inherent in a decentralized legislature.28

Consensus Building

Legislators seeking policy changes or requesting a congressional investigation may be confronted by an array of political interests. The normal legislative or oversight process may sometimes suffer politically from charges of partisanship.29 By contrast, the nonpartisan or bipartisan character of most congressional commissions may make their findings and recommendations less susceptible to such charges and result in further credibility both in Congress and among the public.30

Commissions may also give competing viewpoints space to negotiate compromises, bypassing the short-term tactical political maneuvers that may accompany public negotiations in a congressional markup or oversight session.31 Similarly, because commission members are often not elected, they may be better suited to suggest unpopular, but arguably necessary, policy solutions.32

Solving Collective Action Problems

A commission may allow legislators to solve collective action problems, situations in which all legislators individually seek to protect the interests of their own district, despite widespread agreement that the collective result of such interests is something none of them prefers. Legislators can use a commission to jointly "tie their hands" in such circumstances, allowing general consensus about a particular policy solution to avoid being impeded by individual concerns about the effect or implementation of the solution.33

For example, in 1988 Congress established the Base Closure and Realignment Commission (BRAC) as a politically and geographically neutral body to make independent decisions about closures of military bases.34 The list of bases slated for closure by the commission was required to be either accepted or rejected as a whole by Congress, bypassing internal congressional politics over which individual bases would be closed, and protecting individual Members from political charges that they didn't "save" their district's base.35

Raising Visibility

By establishing a commission, Congress can often provide a highly visible forum for important issues that might otherwise receive scant attention from the public.36 Commissions often are composed of notable public figures, allowing personal prestige to be transferred to policy solutions.37 Meetings and press releases from a commission may receive significantly more attention in the media than corresponding information coming directly from members of congressional committees. Upon completion of a commission's work product, public attention may be temporarily focused on a topic that otherwise would receive scant attention, thus increasing the probability of congressional action within the policy area.38

Criticism of Commissions

Congressional commissions have been criticized by both political and scholarly observers. These criticisms chiefly fall into three groups. First, critics often charge that commissions are an "abdication of responsibility" on the part of legislators.39 Second, commissions are criticized for being undemocratic, replacing elected legislators with appointed decisionmakers. Third, critics also argue that commissions are financially inefficient; they are expensive and their findings often ignored by Congress.

Abdicated Responsibility

Critics of commissions argue that they are primarily created by legislators specifically for "blame avoidance."40 In this view, Congress uses commissions to distance itself from risky decisions when confronted with controversial issues. By creating a commission, legislators can take credit for addressing a topic of controversy without having to take a substantive position on the topic. If the commission's work is ultimately popular, legislators can take credit for the work. If the commission's work product is unpopular, legislators can shift responsibility to the commission itself.41

Reduced Democratic Accountability

A second concern about commissions is that they are not democratic. This criticism takes three forms. First, commissions may be unrepresentative of the general population; the members of most commissions are not elected and may not reflect the variety of popular opinion on an issue.42 Second, commissions lack popular accountability. Unlike Members of Congress, commission members are often insulated from the electoral pressures of popular opinion. Finally, commissions may not operate in public; unlike Congress, their meetings, hearings, and investigations may be held in private.43

Financial Inefficiency

A third criticism of commissions is that they have high costs and low returns. Congressional commission costs vary widely, ranging from several hundred thousand dollars to over $10 million. Coupled with this objection is the problem of congressional response to the work of a commission; in most cases, Congress is under no obligation to act, or even respond to the work of a commission. If legislators disagree with the results or recommendations of a commission's work, they may simply ignore it. In addition, there is no guarantee that any commission will produce a balanced product; commission members may have their own agendas, biases, and pressures. Or they may simply produce a mediocre work product.44 Finally, advisory boards create economic and legislative inefficiency if they function as patronage devices, with Members of Congress using commission positions to pay off political debts.45

Selected Considerations for Congress

Statutes establishing congressional advisory commissions generally provide the scope of a commission's mission, its structure, and its rules of procedures. Legislators can tailor the composition, organization, and working arrangements of a commission, based on the particular goals of Congress. As a result, individual congressional commissions often have an organizational structure and powers quite different from one another.46

This section provides an overview of certain features commonly found in commission statutes. For a more detailed and comprehensive description of legislative language and features that are often included in congressional advisory commission statutes, see CRS Report R45328, Designing Congressional Commissions: Background and Considerations for Congress, by William T. Egar.

Membership and Appointment Authority

When creating a new advisory commission, several potential membership structures might be considered. These could include the number of commissioners and who should appoint the members.

Congressional commissions use a wide variety of membership framework and appointment structures. The statute may require that membership of a commission be made up in whole or in part of specifically designated Members of Congress, typically Members in congressional or committee leadership positions. In other cases, selected leaders, often with balance between the parties, appoint commission members, who may or may not be Members of Congress. A third common statutory framework is to have selected leaders, again often with balance between the parties, recommend members, who may or may not be Members of Congress, for appointment to a commission. These leaders may act either in parallel or jointly, and the recommendation may be made either to other congressional leaders, such as the Speaker of the House and President pro tempore of the Senate, or to the President.

Reporting Requirements

Congressional commissions are usually statutorily directed to carry out specific tasks. One of the primary functions of most congressional commissions is to produce a final report for Congress outlining their activities, findings, and legislative recommendations.47 These reports can be sent to Congress generally, to specific congressional committees, to the President, to executive agencies, or to a combination of entities. Recommendations contained in a commission report are only advisory. The potential implementation of such recommendations is dependent upon future congressional or executive branch action.

Report Destination

Most commissions submit their work product to both Congress and the President. A smaller number submit their work to Congress only, and others have submitted their work to both Congress and a specified executive branch agency. The report's destination might matter for the type of future action taken on a topic. If a report is sent to both Congress and the President, potential exists for either legislative or executive action in that policy area. If a report is sent to only one entity. that might reduce the likelihood that other actors might address a particular concern.

Deadlines

Most commissions are given statutory deadlines for the submission of their final report. The deadline for the submission of final reports varies from commission to commission. Some commissions, such as the National Commission on the Cost of Higher Education,48 have been given less than six months to submit their final report for Congress. Other commissions, such as the Antitrust Modernization Commission,49 have been given three or more years to complete their work product.

Commission Expenses

Congressional commission costs vary widely, and have been funded in a variety of ways. Overall expenses for any individual commission are dependent on a variety of factors, including whether commissioners are paid, the number of potential staff and their pay levels, and the duration of the commission.

Many commissions have few or no full-time staff; others employ large numbers, such as the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States,50 which had a full-time paid staff of 80. Additionally, some commissions provide compensation to members; others only reimburse members for travel expenses. Many commissions finish their work and terminate within a year of creation; in other cases, work may not be completed for several years.

Secondary factors that can affect commission costs include the number of commissioners, how often the commission meets or holds hearings, and the number and size of publications the commission produces. For a more detailed analysis of commission funding and expenditures, see CRS Report R45826, Congressional Commissions: Funding and Expenditures, by William T. Egar.

Commission Member Pay

Most statutorily created congressional commissions do not compensate their members, except to reimburse members for expenses directly related to their service, such as travel costs.51 Among congressional commissions that compensate their members, the level of compensation is almost always specified statutorily, and is typically set in accordance with one of the federal pay scales, prorated to the number of days of service.52 The most common level of compensation is the daily equivalent of Level IV of the Executive Schedule (EX), which has a basic annual rate of pay of $166,50053 in 2019.54

Most commissions created in the past since the 101st Congress have not paid members beyond reimbursement. The remaining commissions have generally paid members at the daily equivalent of Level IV of the Executive Schedule.

Staffing

Advisory commissions are usually authorized to hire a staff. Many of these commissions are specifically authorized to appoint a staff director and other personnel as necessary. The size of the staff is not generally specified, allowing the commission flexibility in judging its own staffing requirements. Typically, maximum pay rates will be specified, but the commission will be granted authority to set actual pay rates within those guidelines.

Most of these congressional commissions are also authorized to hire consultants and procure intermittent services. Many commissions are statutorily authorized to request that federal agencies detail personnel to assist the commission. Some commissions are also authorized to accept voluntary services.

Cataloging Congressional Commissions

This report attempts to identify all congressional commissions enacted into law between the 101st and 115th Congress.

Methodology

To identify congressional commissions, CRS searched Congress.gov for terms and phrases related to commissions within the text of laws enacted between the 101st (1989-1990) and 115th (2017-2018) Congresses.55 Each piece of legislation returned was examined to determine if (1) the legislation established a commission, and (2) the commission met the five criteria outlined above. If the commission met the criteria, its name, public law number, Statutes-at-Large citation, date of enactment, and other information were recorded.

Results

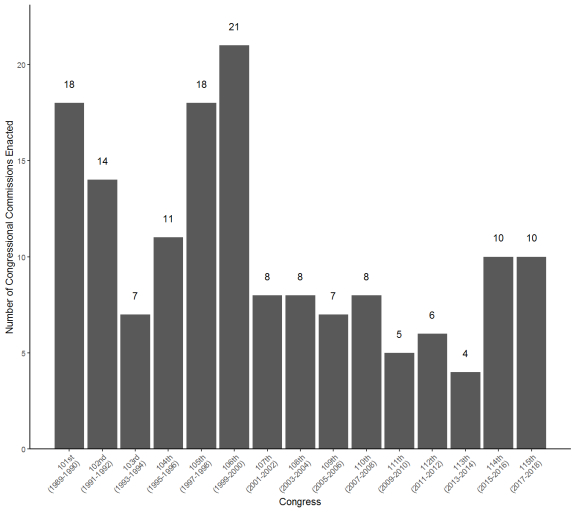

A total of 155 congressional commissions were identified through this search. Figure 1 shows the number of commissions enacted in each Congress between the 101st and 115th Congress.

|

Figure 1. Number of Congressional Commissions Created by Congress 101st to 115th Congress |

|

|

Source: CRS search of public laws enacted between the 101st and 115th Congress. |

Two caveats accompany these results. As stated above, identifying congressional commissions involves making judgment calls about particular characteristics. Second, tracking provisions of law that create congressional commissions is an inherently inexact exercise. Although many such bodies are created in easily identifiable freestanding statutes, others are contained within the statutory language of lengthy omnibus legislation.56 Consequently, individual commissions may have been missed by the search methodology.

Congressional Commissions, 101st to 115th Congress

The tables that follow provide information on the 155 congressional commissions CRS identified through a search of Congress.gov for legislation enacted between the 101st and 115th Congresses. Not included are commissions that were reauthorized during a given Congress. For example, in the 109th Congress, the Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attacks was reestablished. Since it was not a new commission, it is not included in the table (Table 12) for the 109th Congress.

Each Congress is listed in its own table. For each newly created commission, the following information is provided: the name of the commission, the public law creating the commission, and the date of enactment.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

400 Years of African-American History Commission |

P.L. 115-102, 131 Stat. 2248, January 8, 2018 |

|

Commission on Farm Transactions-Needs for 2050 |

P.L. 115-334, 132 Stat. 5009, December 20, 2018 |

|

Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse Attacks and Similar Eventsa |

P.L. 115-91; 131 Stat. 1786; December 12, 2017 |

|

Commission on Military Aviation Safety |

P.L. 115-232, 132 Stat. 1992, August 13, 2018 |

|

Cyberspace Solarium Commission |

P.L. 115-232, 132 Stat. 2140, August 13, 2018 |

|

Frederick Douglass Bicentennial Commission |

P.L. 115-77, 131 Stat. 1251, November 2, 2017 |

|

National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence |

P.L. 115-232, 132 Stat. 192, August 13, 2018 |

|

Public-Private Partnership Advisory Council to End Human Trafficking |

P.L. 115-393, 132 Stat. 5278, December 21, 2018 |

|

Syria Study Group |

P.L. 115-254, 132 Stat. 3519, October 5, 2018 |

|

Women's Suffrage Centennial Commissionb |

P.L. 115-31, 131 Stat. 502, May 5, 2017 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

a. The Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse Attacks and Similar Events is a distinct commission from the Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack that was created by P.L. 106-398, Title XIV. This legislation authorizing the new Electromagnetic Pulse Commission repealed P.L. 106-398, Title XIV, which authorized the original commission.

b. The Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission was incorporated by reference in P.L. 115-31. Text of the bill can be found in S. 847 (115th Congress), and in Appendix C of P.L. 115-31 (131 Stat. 842A-17).

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Alyce Spotted Bear and Walter Soboleff Commission on Native Children |

P.L. 114-244; 130 Stat. 981; October 14, 2016 |

|

Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking |

P.L. 114-140; 130 Stat. 317; March 30, 2016 |

|

Commission on the National Defense Strategy of the United States |

P.L. 114-328; 130 Stat. 2367; December 23, 2016 |

|

Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico |

P.L. 114-187; 130 Stat. 593; June 30, 2016 |

|

Creating Options for Veterans' Expedited Recovery Commission |

P.L. 114-198; 130 Stat. 769; July 22, 2016 |

|

National Commission on Military, National and Public Service |

P.L. 114-328; 130 Stat. 2131; December 23, 2016 |

|

John F. Kennedy Centennial Commission |

P.L. 114-215; 130 Stat. 830; July 29, 2016 |

|

United States Semiquincentennial Commission |

P.L. 114-196; 130 Stat. 685; July 22, 2016 |

|

Virgin Islands of the United States Centennial Commission |

P.L. 114-224; 130 Stat. 921, September 29, 2016 |

|

Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission |

P.L. 114-323; 130 Stat. 1936; December 16, 2016 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Commission on Care |

P.L. 113-146; 128 Stat. 1773; August 7, 2014 |

|

Commission to Study the Potential Creation of a National Women's History Museum |

P.L. 113-291; 128 Stat. 3810; December 19, 2014 |

|

National Commission on the Future of the Army |

P.L. 113-291; 128 Stat. 3664; December 19, 2014 |

|

National Commission on Hunger |

P.L. 113-76; 128 Stat. 41; January 17, 2014 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Commission to Eliminate Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities |

P.L. 112-275; 126 Stat. 2461; January 14, 2013 |

|

Commission on Long-Term Care |

P.L. 112-240; 126 Stat. 2358; January 2, 2013 |

|

Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise |

P.L. 112-239; 126 Stat. 2208; January 2, 2013 |

|

Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission |

P.L. 112-239; 126 Stat. 1787; January 2, 2013 |

|

National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force |

P.L. 112-239; 126 Stat. 1703; January 2, 2013 |

|

World War I Centennial Commission |

P.L. 112-272; 126 Stat. 2449; January 15, 2013 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Independent Panel to Assess the Quadrennial Defense Review |

P.L. 111-84; 123 Stat. 2467; October 28, 2010 |

|

Indian Law and Order Commission |

P.L. 111-211; 124 Stat. 2282; July 29, 2010 |

|

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission |

P.L. 111-21; 123 Stat. 1625; May 20, 2009 |

|

Foreign Intelligence and Information Commission |

P.L. 111-259; 124 Stat. 2739; October 7, 2010 |

|

Ronald Reagan Centennial Commission |

P.L. 111-25; 123 Stat. 1767; June 2, 2009 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Commission on the Abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade |

P.L. 110-183; 122 Stat. 606; February 5, 2008 |

|

Commission on the Prevention of Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferation and Terrorism |

P.L. 110-53; 121 Stat. 501; August 3, 2007 |

|

Commission to Study the Potential Creation of a National Museum of the American Latino |

P.L. 110-229; 122 Stat. 784; May 8, 2008 |

|

Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan |

P.L. 110-181; 122 Stat. 230; January 28, 2008 |

|

Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States |

P.L. 110-181; 122 Stat. 319; January 28, 2008 |

|

Congressional Oversight Panel (Emergency Economic Stabilization Act) |

P.L. 110-343; 122 Stat. 3791; October 3, 2008 |

|

Genetic Nondiscrimination Study Commission |

P.L. 110-233; 122 Stat. 917; October 3, 2008 |

|

National Commission on Children and Disasters |

P.L. 110-161; 121 Stat. 2213; December 26, 2007 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Commission on the Implementation of the New Strategic Posture of the United States |

P.L. 109-163; 119 Stat. 3431; January 6, 2006 |

|

Human Space Flight Independent Investigation Commission |

P.L. 109-155; 119 Stat. 2941; December 30, 2005 |

|

Motor Fuel Tax Enforcement Advisory Commission |

P.L. 109-59; 119 Stat. 1959; August 10, 2005 |

|

National Surface Transportation Infrastructure Financing Commission |

P.L. 109-59; 119 Stat. 1962; August 10, 2005 |

|

National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Commission |

P.L. 109-59; 119 Stat. 1471; August 10, 2005 |

|

Technical Study Panel |

P.L. 109-236; 120 Stat. 501; June 15, 2006 |

|

United States Commission on North American Energy Freedom |

P.L. 109-58; 119 Stat. 1064; August 8, 2005 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Commission on the Abraham Lincoln Study Abroad Fellowship Program |

P.L. 108-199; 118 Stat. 435; January 23, 2003 |

|

Commission on the National Guard and Reserve |

P.L. 108-375; 118 Stat. 1880; October 28, 2004 |

|

Commission on Review the Overseas Military Facility Structure of the United States |

P.L. 108-132; 117 Stat. 1382; November 22, 2003 |

|

Helping to Enhance the Livelihood of People (HELP) Around the Globe Commission |

P.L. 108-199; 118 Stat. 101; January 23, 2003 |

|

National Commission on Small Community Air Service |

P.L. 108-176; 117 Stat. 2549; October 18, 2003 |

|

National Prison Rape Reduction Commission |

P.L. 108-79; 117 Stat. 980; September 4, 2003 |

|

Panel to Review Sexual Misconduct Allegations at United States Air Force Academy |

P.L. 108-11; 117 Stat. 609; April 16, 2003 |

|

Veterans' Disability Benefits Commission |

P.L. 108-136; 117 Stat. 1676; November 24, 2003 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Antitrust Modernization Commission |

P.L. 107-273; 116 Stat. 1856; November 2, 2002 |

|

Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary Commission |

P.L. 107-202; 116 Stat. 739; July 24, 2002 |

|

Brown v. Board of Education 50th Anniversary Commission |

P.L. 107-41; 115 Stat. 226; September 18, 2001 |

|

Commission on the Application of Payment Limitations for Agriculture |

P.L. 107-171; 116 Stat. 216; May 13, 2002 |

|

Guam War Claims Review Commission |

P.L. 107-333; 116 Stat. 2873; December 12, 2002 |

|

National Commission for the Review of the Research and Development Programs of the United States Intelligence Community |

P.L. 107-306; 116 Stat. 2437; November 27, 2002 |

|

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States |

P.L. 107-306; 116 Stat. 2408; November 27, 2002 |

|

National Museum of African American History and Culture Plan for Action Presidential Commission |

P.L. 107-106; 115 Stat. 1009; December 28, 2001 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission |

P.L. 106-173; 114 Stat. 14; February 25, 2000 |

|

Commission on Affordable Housing and Health Care Facility Needs in the 21st Century |

P.L. 106-74; 113 Stat. 1106; October 20, 1999 |

|

Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attacks |

P.L. 106-398, 114 Stat. 1645A-345; October 30, 2000 |

|

Commission on Indian and Native Alaskan Health Care |

P.L. 106-310; 114 Stat. 1216; October 17, 2000 |

|

Commission on Ocean Policy |

P.L. 106-256; 114 Stat. 645; October 7, 2000 |

|

Commission on the Future of the United States Aerospace Industry |

P.L. 106-398; 114 Stat. 1654A-301; October 30, 2000 |

|

Commission on the National Military Museum |

P.L. 106-65; 113 Stat. 880; October 5, 1999 |

|

Commission on Victory in the Cold War |

P.L. 106-65; 113 Stat. 765; October 5, 1999 |

|

Commission to Assess United States National Security Space Management and Organization |

P.L. 106-65; 113 Stat. 813; October 5, 1999 |

|

Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission |

P.L. 106-79; 113 Stat. 1274; October 25, 1999 |

|

Forest Counties Payments Committee |

P.L. 106-291; 114 Stat. 991; October 11, 2000 |

|

James Madison Commemoration Commission |

P.L. 106-550; 114 Stat. 2745; December 19, 2000 |

|

Judicial Review Commission on Foreign Asset Control |

P.L. 106-120; 113 Stat. 1633; December 3, 1999 |

|

Lands Title Report Commission |

P.L. 106-568; 114 Stat. 2923; December 27, 2000 P.L. 106-569; 114 Stat. 2959; December 27, 2000 |

|

Millennial Housing Commission |

P.L. 106-74; 113 Stat. 1070; October 20, 1999 |

|

National Commission for the Review of the National Reconnaissance Office |

P.L. 106-120; 113 Stat. 1620; December 3, 1999 |

|

National Commission on the Use of Offsets in Defense Trade |

P.L. 106-113; 113 Stat. 1501A-502; November 29, 1999 |

|

National Commission to Ensure Consumer Information and Choice in the Airline Industry |

P.L. 106-181; 114 Stat. 105; April 15, 2000 |

|

National Wildlife Refuge System Centennial Commission |

P.L. 106-408; 114 Stat. 1783; November 1, 2000 |

|

Public Interest Declassification Board |

P.L. 106-567; 114 Stat. 2856; December 27, 2000 |

|

Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Advisory Panel |

P.L. 106-170; 113 Stat. 1887; December 17, 1999 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Advisory Committee on Electronic Commerce |

P.L. 105-277; 112 Stat. 2681-722; October 21, 1998 |

|

Amtrak Reform Council |

P.L. 105-134; 111 Stat. 2579; December 2, 1997 |

|

Census Monitoring Board |

P.L. 105-119; 111 Stat. 2483; November 26, 1997 |

|

Commission on the Advancement of Women and Minorities in Science, Engineering, and Technology Development |

P.L. 105-255; 112 Stat. 1889; October 14, 1998 |

|

Commission on Military Training and Gender-Related Issues |

P.L. 105-85; 111 Stat. 1750; November 18, 1997 |

|

Commission on Online Child Protection |

P.L. 105-277; 112 Stat. 2681-739; October 21, 1998 |

|

Independent Panel to Evaluate the Adequacy of Current Planning for United States Long-Range Air Power and the Requirement for Continued Low-Rate Production of B-2 Stealth Bombers |

P.L. 105-56; 111 Stat. 1249; October 8, 1997 |

|

National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare |

P.L. 105-33; 111 Stat. 347; October 5, 1997 |

|

National Commission on the Cost of Higher Education |

P.L. 105-18; 111 Stat. 207; June 12, 1997 |

|

National Commission on Terrorism |

P.L. 105-277; 112 Stat. 2681-210; October 21, 1998 |

|

National Health Museum Commission |

P.L. 105-78; 111 Stat. 1525; November 13, 1997 |

|

Parents Advisory Council on Youth Drug Abuse |

P.L. 105-277; 112 Stat. 2681-690; October 21, 1998 |

|

Presidential Advisory Commission on Holocaust Assets in the United States |

P.L. 105-186; 112 Stat. 611; June 23, 1998 |

|

Twenty-First Century Workforce Commission |

P.L. 105-220; 112 Stat. 1087; October 7, 1998 |

|

Trade Deficit Review Commission |

P.L. 105-277; 112 Stat. 2681-547; October 21, 1998 |

|

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom |

P.L. 105-292; 112 Stat. 2797; October 27, 1998 |

|

Web-Based Education Commission |

P.L. 105-244; 112 Stat. 1822; October 7, 1998 |

|

Women's Progress Commemoration Commission |

P.L. 105-341; 112 Stat. 3196; October 31, 1998 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Commission on 21st Century Production Agriculture |

P.L. 104-127; 110 Stat. 938; April 4, 1996 |

|

Commission on Consensus Reform in the District of Columbia Public Schools |

P.L. 104-134; 110 Stat. 1321-151; April 26, 1996 |

|

Commission on Maintaining United States Nuclear Weapons Expertise |

P.L. 104-201; 110 Stat. 2843; September 23, 1996 |

|

Commission on Servicemembers and Veterans Transition Assistance |

P.L. 104-275; 110 Stat. 3346; October 9, 1996 |

|

Commission on the Advancement of Federal Law Enforcement |

P.L. 104-132; 110 Stat. 1305; April 24, 1996 |

|

Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States |

P.L. 104-201; 110 Stat. 2711; September 23, 1996 |

|

Commission to Assess the Organization of the Federal Government to Combat the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction |

P.L. 104-293; 110 Stat. 3470; October 11, 1996 |

|

National Civil Aviation Review Commission |

P.L. 104-264; 110 Stat. 3241; October 9, 1996 |

|

National Commission on Restructuring the Internal Revenue Service |

P.L. 104-52; 110 Stat. 509; November 19, 1995 |

|

National Gambling Impact Study Commission |

P.L. 104-169; 110 Stat. 1482; October 3, 1996 |

|

Water Rights Task Force |

P.L. 104-127; 110 Stat. 1021; April 4, 1996 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Advisory Board on Welfare Indicators |

P.L. 103-432; 108 Stat. 4463; October 31, 1994 |

|

Commission on Leave |

P.L. 103-3; 107 Stat. 23; February 5, 1993 |

|

Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy |

P.L. 103-236; 108 Stat. 525; April 30, 1994 |

|

Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the United States Intelligence Community |

P.L. 103-359; 108 Stat. 3456; October 14, 1994 |

|

National Bankruptcy Review Commission |

P.L. 103-394; 108 Stat. 4147; October 22, 1994 |

|

National Commission on Crime Control and Prevention |

P.L. 103-322; 108 Stat. 2089; September 13, 1994 |

|

National Skill Standards Board |

P.L. 103-227; 108 Stat. 191; March 31, 1994 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Commission on Broadcasting to the People's Republic of China |

P.L. 102-138; 105 Stat. 705; October 28, 1991 |

|

Commission on Child and Family Welfare |

P.L. 102-521; 106 Stat. 3406; October 25, 1992 |

|

Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Capitol |

P.L. 102-392; 106 Stat. 1726; October 6, 1992 |

|

Commission on the Social Security "Notch" Issue |

P.L. 102-393; 106 Stat. 1777; October 6, 1992 |

|

Commission to Protect Investment in America's Infrastructure |

P.L. 102-240; 105 Stat. 2020; December 18, 1991 |

|

Congressional Commission on the Evaluation of Defense Industry Base Policy |

P.L. 102-558; 106 Stat. 4220; October 28, 1992 |

|

Glass Ceiling Commission |

P.L. 102-166; 105 Stat. 1082; November 21, 1991 |

|

National Commission on Intermodal Transportation |

P.L. 102-240; 105 Stat. 2160; December 18, 1991 |

|

National Commission on Reducing Capital Gains for Emerging Technology |

P.L. 102-245; 106 Stat. 21; February 14, 1992 |

|

National Commission on Rehabilitation Services |

P.L. 102-569; 105 Stat. 4473; October 29, 1992 |

|

National Commission on the Future Role of United States Nuclear Weapons |

P.L. 102-172; 105 Stat. 1208; November 26, 1991 |

|

National Commission to Promote a Strong Competitive Airline Industry |

P.L. 102-581; 106 Stat. 4891; October 31, 1992 |

|

National Education Commission on Time and Learning |

P.L. 102-62; 105 Stat. 306; June 27, 1991 |

|

Thomas Jefferson Commemoration Commission |

P.L. 102-343; 106 Stat. 915; October 17, 1992 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.

|

Commission |

Authority |

|

Civil War Sites Advisory Commission |

P.L. 101-628; 104 Stat. 4504; November 28, 1990 |

|

Commission on Legal Immigration Reform |

P.L. 101-649; 104 Stat. 5001; November 29, 1990 |

|

Commission on Management of the Agency for International Development Programs |

P.L. 101-513; 104 Stat. 2022; November 5, 1990 |

|

Commission on State and Private Forests |

P.L. 101-624; 104 Stat. 3548; November 28, 1990 |

|

Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission |

P.L. 101-510; 104 Stat. 1808; November 5, 1990 |

|

Independent Commission |

P.L. 101-121; 103 Stat. 742; October 23, 1989 |

|

Joint Federal-State Commission on Policies and Programs Affecting Alaska Natives |

P.L. 101-379; 104 Stat. 478; October 18, 1990 |

|

National Advisory Council on the Public Service |

P.L. 101-363; 104 Stat. 424; August 14, 1990 |

|

National Commission on American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Housing |

P.L. 101-235; 103 Stat. 2052; December 15, 1989 |

|

National Commission on Defense and National Security |

P.L. 101-511; 104 Stat. 1899; November 5, 1990 |

|

National Commission on Financial Institution Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement |

P.L. 101-647; 104 Stat. 4889; November 29, 1990 |

|

National Commission on Judicial Discipline and Removal |

P.L. 101-650; 104 Stat. 5124; December 1, 1990 |

|

National Commission on Manufactured Housing |

P.L. 101-625; 104 Stat. 4413; November 28, 1990 |

|

National Commission on Severely Distressed Public Housing |

P.L. 101-235; 103 Stat. 2048; December 15, 1989 |

|

National Commission on Wildfire Disasters |

P.L. 101-286; 104 Stat. 171; May 9, 1990 |

|

National Commission to Support Law Enforcement |

P.L. 101-515; 104 Stat. 2122; November 5, 1990 |

|

Preservation of Jazz Advisory Commission |

P.L. 101-499; 104 Stat. 1210; November 2, 1990 |

|

Risk Assessment and Management Commission |

P.L. 101-549; 104 Stat. 2574; November 15, 1990 |

Source: CRS analysis of commission legislation from Congress.gov.