Introduction

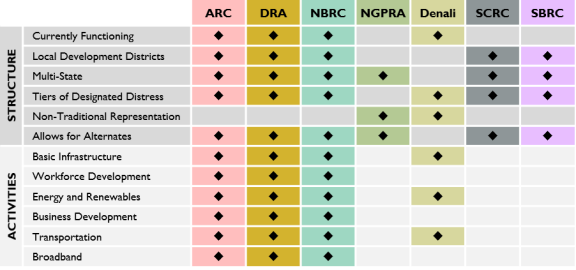

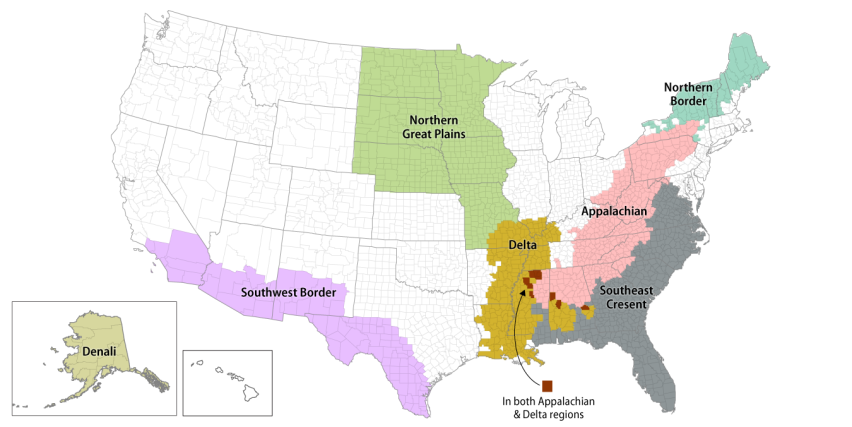

This report describes the structure, activities, legislative history, and funding history of seven federally-chartered regional commissions and authorities: the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC); the Delta Regional Authority (DRA); the Denali Commission; the Northern Border Regional Commission (NBRC); the Northern Great Plains Regional Authority (NGPRA); the Southeast Crescent Regional Commission (SCRC); and the Southwest Border Regional Commission (SBRC) (Table A-1). The federal regional commissions are also functioning examples of place-based and intergovernmental approaches to economic development, which receive regular congressional interest.1

The federal regional commissions and authorities integrate federal and state economic development priorities alongside regional and local considerations (Figure A-1). As federally-chartered agencies created by acts of Congress, the federal regional commissions and authorities depend on congressional appropriations for their activities and administration, and are subject to congressional oversight.

Seven federal regional commissions and authorities were authorized by Congress to address instances of major economic distress in certain defined socio-economic regions, with all but one (Alaska's Denali Commission) being multi-state regions (Figure B-1). The first such federal regional commission, the Appalachian Regional Commission, was founded in 1965. The other commissions and authorities may have roots in the intervening decades, but were not founded until 1998 (Denali), 2000 (Delta Regional Authority), and 2002 (the Northern Great Plains Regional Authority). The most recent commissions—Northern Border Regional Commission, Southeast Crescent Regional Commission, and Southwest Border Regional Commission—were authorized in 2008.

Four of the seven entities—the Appalachian Regional Commission, the Delta Regional Authority, the Denali Commission, and the Northern Border Regional Commission—are currently active and receive regular annual appropriations.

Certain strategic emphases and programs have evolved over time in each of the functioning federal regional commissions and authorities. However, their overarching missions to address economic distress have not changed, and their associated activities have broadly remained consistent to those goals as funding has allowed. In practice, the functioning federal regional commissions and authorities engage in their respective economic development efforts through multiple program areas, which may include, but are not limited to basic infrastructure; energy; ecology/environment and natural resources; workforce/labor; and business development.

Appalachian Regional Commission

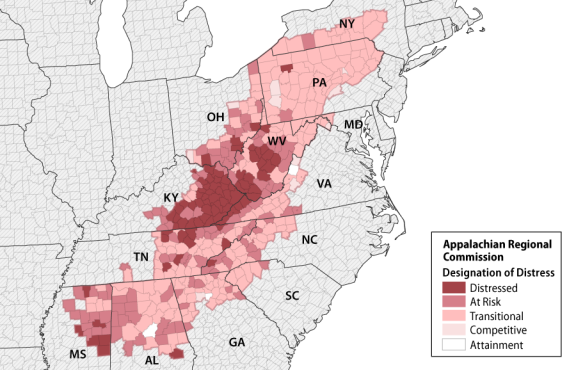

The Appalachian Regional Commission was established in 1965 to address economic distress in the Appalachian region.2 The ARC's jurisdiction spans 420 counties in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia (Figure 1). The ARC was originally created to address severe economic disparities between Appalachia and that of the broader United States; recently, its mission has grown to include regional competitiveness in a global economic environment.

Structure and Activities

Commission Structure

According to the authorizing legislation, the Appalachian Regional Development Act of 1965, as amended,3 the ARC is a federally-chartered, regional economic development entity led by a federal co-chair, whose term is open-ended, and the 13 participating state governors, of which one serves as the state co-chair for a term of "at least one year."4 The federal co-chair is appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. The authorizing act also allows for the appointment of federal and state alternates to the commission. The ARC is a federal-state partnership, with administrative costs shared equally by the federal government and member states, while economic development activities are funded by congressional appropriations.

Regional Development Plan

According to authorizing legislation and the ARC code,5 the ARC's programs abide by a Regional Development Plan (RDP), which includes documents prepared by the states and the commission. The RDP is comprised of the ARC's strategic plan, its bylaws, member state development plans, each participating state's annual strategy statement, the commission's annual program budget, and the commission's internal implementation and performance management guidelines.

The RDP integrates local, state, and federal economic development priorities into a common regional agenda. Through state plans and annual work statements, states establish goals, priorities, and agendas for fulfilling them. State planning typically includes consulting with local development districts (LDDs), which are multicounty organizations that are associated with and financially supported by the ARC and advise on local priorities.6

There are 73 ARC-associated LDDs. They may be conduits for funding for other eligible organizations, and may also themselves be ARC grantees.7 State and local governments, governmental entities, and nonprofit organizations are eligible for ARC investments, including both federal- and also state-designated tribal entities. Notably, non-federally recognized, state-designated tribal entities are eligible to receive ARC funding, which is an exception to the general rarity of federal funds being available to non-federally recognized tribal entities.8

ARC's strategic plan is a five-year document, reviewed annually, and revised as necessary. The current strategic plan, adopted in November 2015,9 prioritizes five investment goals:

- 1. entrepreneurial and business development;

- 2. workforce development;

- 3. infrastructure development;

- 4. natural and cultural assets; and

- 5. leadership and community capacity.

The ARC's investment activities are divided into 10 program areas:10

|

|

These program areas can be funded through five types of eligible activities:12

- 1. business development and entrepreneurship, through grants to help create and retain jobs in the region, including through targeted loan funds;

- 2. education and training, for projects that "develop, support, or expand education and training programs";

- 3. health care, through funding for "equipment and demonstration projects" and sometimes for facility construction and renovation, including hospital and community health services;

- 4. physical infrastructure, including funds for basic infrastructure services such as water and sewer facilities, as well as housing and telecommunications; and

- 5. leadership development and civic capacity, such as community-based strategic plans, training for local leaders, and organizational support.

While most funds are used for economic development grants, approximately $50 million is reserved for the Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization (POWER) Initiative.13 The POWER Initiative began in 2015 to provide economic development funding for addressing economic and labor dislocations caused by energy transition principally in coal communities in the Appalachian region.14

Distressed Counties

The ARC is statutorily obligated to designate counties according to levels of economic distress.15 Distress designations influence funding priority and determine grant match requirements. Using an index-based classification system, the ARC compares each county within its jurisdiction with national averages based on three economic indicators:16 (1) three-year average unemployment rates; (2) per capita market income; and (3) poverty rates. These factors are calculated into a composite index value for each county, which are ranked and sorted into designated distress levels.17 Each distress level corresponds to a given county's ranking relative to that of the United States as a whole. These designations are defined as follows by the ARC, starting from "worst" distress:18

- distressed counties, or those with values in the "worst" 10% of U.S. counties;

- at-risk, which rank between worst 10% and 25%;

- transitional, which rank between worst 25% and best 25%;

- competitive, which rank between "best" 25% and best 10%; and

- attainment, or those which rank in the best 10%.

The designated level of distress is statutorily tied to allowable funding levels by the ARC (funding allowance), the balance of which must be met through grant matches from other funding sources (including potentially other federal funds) unless a waiver or special dispensation is permitted: distressed (80% funding allowance, 20% grant match); at-risk (70%); transitional (50%); competitive (30%); and attainment (0% funding allowance). Exceptions can be made to grant match thresholds. Attainment counties may be able to receive funding for projects where sub-county areas are considered to be at higher levels of distress, and/or in those cases where the inclusion of an attainment county in a multi-county project would benefit one or more non-attainment counties or areas. In addition, special allowances may reduce or discharge matches, and match requirements may be met with other federal funds.

Legislative History

Council of Appalachian Governors

In 1960,19 the Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia governors formed the Council of Appalachian Governors to highlight Appalachia's extended economic distress and to press for increased federal involvement. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy formed the President's Appalachian Regional Commission (PARC) and charged it with developing an economic development program for the region. PARC's report, issued in 1964,20 called for the creation of an independent agency to coordinate federal and state efforts to address infrastructure, natural resources, and human capital issues in the region. The PARC also included some Ohio counties as part of the Appalachian region.

Appalachian Regional Development Act

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Appalachian Regional Development Act,21 which created the ARC to address the PARC's recommendations, and added counties in New York and Mississippi. The ARC was directed to administer or assist in the following initiatives:

- The creation of the Appalachian Development Highway System;

- Establishing "Demonstration Health Facilities" to fund health infrastructure;

- Land stabilization, conservation, and erosion control programs;

- Timber development organizations, for purposes of forest management;

- Mining area restoration, for rehabilitating and/or revitalizing mining sites;

- A water resources survey;

- Vocational education programs; and

- Sewage treatment infrastructure.

Major Amendments to the ARC Before 2008

Appalachian Regional Development Act Amendments of 1975

In 1975, the ARC's authorizing legislation was amended to require that state governors themselves serve as the state representatives on the commission, overriding original statutory language in which governors were permitted to appoint designated representatives.22 The amendments also included provisions to expand public participation in ARC plans and programs. They also required states to consult with local development districts and local governments and authorized federal grants to the ARC to assist states in enhancing state development planning.

Appalachian Regional Development Reform Act of 1998

Legislative reforms in 1998 introduced county-level designations of distress.23 The legislation organized county-level distress into three bands, from "worst" to "best": distressed counties; competitive counties; and attainment counties. The act imposed limitations on funding for economically strong counties: (1) "competitive," which could only accept ARC funding for 30% of project costs (with the 70% balance being subject to grant match requirements); and (2) "attainment," which were generally ineligible for funding, except through waivers or exceptions.

In addition, the act withdrew the ARC's legislative mandate for certain programs, including the land stabilization, conservation, and erosion control program; the timber development program; the mining area restoration program; the water resource development and utilization survey; the Appalachian airport safety improvements program (a program added in 1971); the sewage treatment works program; and amendments to the Housing Act of 1954 from the original 1965 act.

Appalachian Regional Development Act Amendments of 2002

Legislation in 2002 expanded the ARC's ability to support LDDs, introduced an emphasis on ecological issues, and provided for a greater coordinating role by the ARC in federal economic development activities.24 The amendments also provided new stipulations for the ARC's grant making, limiting the organization to funding 50% of project costs or 80% in designated distressed counties. The amendments also expanded the ARC's efforts in human capital development projects, such as through various vocational, entrepreneurial, and skill training initiatives.

The Appalachian Regional Development Act Amendments of 2008

The Appalachian Regional Development Act Amendments of 2008 is the ARC's most recent substantive legislative development and reflects its current configuration.25 The amendments included:

- 1. various limitations on project funding amounts and commission contributions;

- 2. the establishment of an economic and energy development initiative;

- 3. the expansion of county designations to include an "at-risk" designation; and

- 4. the expansion of the number of counties under the ARC's jurisdiction.

The 2008 amendments introduced funding limitations for ARC grant activities as a whole, as well as to specific programs. According to the 2008 legislation, "the amount of the grant shall not exceed 50 percent of administrative expenses." However, at the ARC's discretion, an LDD that included a "distressed" county in its service area could provide for 75% of administrative expenses of a relevant project, or 70% for "at-risk" counties. Eligible activities could only be funded by the ARC at a maximum of 50% of the project cost,26 or 80% for distressed counties and 70% for "at-risk" counties. The act introduced special project categories, including (1) demonstration health projects; (2) assistance for proposed low- and middle-income housing projects; (3) the telecommunications and technology initiative; (4) the entrepreneurship initiative; and (5) the regional skills partnership. Finally, the "economic and energy development initiative" provided for the ARC to fund activities supporting energy efficiency and renewable technologies. The legislation expanded distress designations to include an "at-risk" category, or counties "most at risk of becoming economically distressed." This raised the number of distress levels to five.27 The legislation also expanded ARC's service area. Ten counties in four states were added to the ARC, which represents the most recent expansion.

Funding History

The ARC is a federal-state partnership, with administrative costs shared equally by the federal government and states, while economic development activities are federally funded. The ARC is also the highest-funded of the federal regional commissions and authorities. Its funding (Table 1) has increased 126% from approximately $73 million in FY2008 to $165 million in FY2019.

The ARC's funding growth is attributable to incremental increases in appropriations along with an approximately $50 million increase in annual appropriated funds in FY2016 set aside to support the POWER Initiative.28 The POWER Initiative was part of a wider federal effort under the Obama Administration to support coal communities affected by the decline of the coal industry. The FY2018 White House budget proposed to shutter the ARC as well as the other federal regional commissions and authorities.29 Congress did not adopt these provisions from the President's budget, and continued to fund the ARC and other commissions.

|

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

|

|

Appropriated Funding |

73.0 |

75.0 |

76.0 |

68.4 |

68.3 |

68.3 |

80.3 |

90.0 |

146.0 |

152.0 |

155.0 |

165.0 |

|

Authorized Funding |

87.0 |

100.0 |

105.0 |

108.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

Sources: Authorized funding amounts compiled by CRS using data from P.L. 110-234, P.L. 113-79, and P.L. 115-334. Appropriated funding amounts compiled by CRS using data from: P.L. 111-85; P.L. 112-10; P.L. 112-74; P.L. 113-6; P.L. 113-76; P.L. 113-235; P.L. 114-113; P.L. 115-31; P.L. 115-141; and P.L. 115-244.

Note: FY2008 marked the authorization of the NBRC, SCRC, and the SBRC; as such, FY2008 was selected as the starting point for displayed data for all commissions and authorities for the sake of consistency.

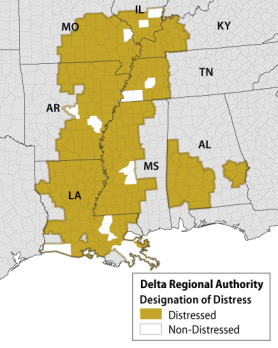

Delta Regional Authority

The Delta Regional Authority was established in 2000 to address economic distress in the Mississippi River Delta region.30 The DRA aims to "improve regional economic opportunity by helping to create jobs, build communities, and improve the lives of the 10 million people"31 in 252 designated counties and parishes in Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee (Figure 2).

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from the Delta Regional Authority and Esri Data and Maps 2018. |

Overview of Structure and Activities

Authority Structure

Like the ARC, the DRA is a federal-state partnership that shares administrative expenses equally, while activities are federally funded. The DRA consists of a federal co-chair appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, and the eight state governors, of which one is state co-chair. The governors are permitted to appoint a designee to represent the state, who also generally serves as the state alternate.32

Entities that are eligible to apply for DRA funding include:

- 1. state and local governments (state agencies, cities and counties/parishes);

- 2. public bodies; and

- 3. non-profit entities.

These entities must apply for projects that operate in or are serving residents and communities within the 252 counties/parishes of the DRA's jurisdiction.

DRA Strategic Planning

Funding determinations are assessed according to the DRA's authorizing statute, its strategic plan, state priorities, and distress designation.33 The DRA strategic plan articulates the authority's high-level economic development priorities. The current strategic plan—Moving the Delta Forward, Delta Regional Development Plan III—was released in April 2016 and is in effect through 2021.34

The strategic plan lists three primary goals:

- 1. workforce competitiveness, to "advance the productivity and economic competitiveness of the Delta workforce";

- 2. strengthened infrastructure, to "strengthen the Delta's physical, digital, and capital connections to the global economy"; and

- 3. increased community capacity, to "facilitate local capacity building within Delta communities, organizations, businesses, and individuals."

State development plans are required by statute every five years to coincide with the strategic plan, and reflect the economic development goals and priorities of member states and LDDs.35The DRA funds projects through 44 LDDs,36 which are multicounty economic development organizations financially supported by the DRA and advise on local priorities. LDDs "provide technical assistance, application support and review, and other services" to the DRA and entities applying for funding. LDDs receive administrative fees paid from awarded DRA funds, which are calculated as 5% of the first $100,000 of an award, and 1% for all dollars above that amount.

Distress Designations

The DRA determines a county or parish as distressed on an annual basis through the following criteria:

- 1. an unemployment rate of 1% higher than the national average for the most recent 24-month period; and

- 2. a per capita income of 80% or less than the national per capita income.37

The DRA designates counties as either distressed or not, and distressed counties received priority funding from DRA grant making activities. By statute, the DRA directs at least 75% of funds to distressed counties; half of those funds must target transportation and basic infrastructure. As of FY2018, 234 of the DRA's 252 counties are considered distressed.

States' Economic Development Assistance Program

The principal investment tool used by the DRA is the States' Economic Development Assistance Program (SEDAP), which "provides direct investment into community-based and regional projects that address the DRA's congressionally mandated four funding priorities." 38

The DRA's four funding priorities are:

- 1. (1) basic public infrastructure;

- 2. (2) transportation infrastructure;

- 3. (3) workforce development; and

- 4. (4) business development (emphasizing entrepreneurship).

The DRA's SEDAP funding is made available to each state according to a four-factor, formula-derived allocation that balances geographic breadth, population size, and economic distress (Table 2).39

The factors and their respective weights are calculated as follows:

- Equity Factor (equal funding among eight states), 50%;

- Distressed Population (DRA counties/parishes), 20%;

- Distressed County Area (DRA counties/parishes), 20%; and

- Population Factor (DRA counties/parishes), 10%.

|

Share of Funding |

Funding Allocation |

|

|

Louisiana |

19.89% |

$ 2,465,089.46 |

|

Mississippi |

15.57% |

$ 1,930,011.64 |

|

Arkansas |

14.73% |

$ 1,825,801.93 |

|

Missouri |

11.45% |

$ 1,419,707.68 |

|

Tennessee |

10.59% |

$ 1,313,068.56 |

|

Alabama |

10.33% |

$ 1,280,015.55 |

|

Kentucky |

9.39% |

$ 1,163,634.96 |

|

Illinois |

8.05% |

$ 997,776.23 |

|

Total |

100.00% |

$ 12,395,106.00 |

Source: Data tabulated by CRS from the DRA website.

DRA investments are awarded from state allocations. SEDAP applications are accepted through LDDs, and projects are sorted into tiers of priority. While all projects must be associated with one of the DRA's four funding priorities, additional prioritization determines the rank order of awards, which include county-level distress designations; adherence to at least one of the federal priority eligibility criteria (see below); adherence to at least one of the DRA Regional Development Plan goals (from the strategic plan); and adherence to at least one of the state's DRA priorities.40

The federal priority eligibility criteria are as follows:

|

|

The DRA is also mandated to expend 50% of its appropriated SEDAP dollars on basic public and transportation infrastructure projects, which lend additional weight to this particular criterion.41

Legislative History

In 1988, the Rural Development, Agriculture, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act for FY1989 (P.L. 100-460) appropriated $2 million and included language that authorized the creation of the Lower Mississippi Delta Development Commission. The LMDDC was a DRA predecessor tasked with studying economic issues in the Delta and developing a 10-year economic development plan. The LMDDC consisted of two commissioners appointed by the President as well as the governors of Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. The commission was chaired by then-Governor William J. Clinton of Arkansas, and the LMDDC released interim and final reports before completing its mandate in 1990. Later, in the White House, the Clinton Administration continued to show interest in an expanded federal role in Mississippi Delta regional economic development.

Key Legislative Activity

- In 1994, Congress enacted the Lower Mississippi Delta Region Heritage Study Act, which built on the LMDDC's recommendations. In particular, the 1994 act saw the Department of the Interior conduct a study on key regional cultural, natural, and heritage sites and locations in the Mississippi Delta region.

- In 1999, the Delta Regional Authority Act of 1999 was introduced in the House (H.R. 2911) and Senate (S. 1622) to establish the DRA by amending the Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act. Neither bill was enacted, but they established the structure and mission later incorporated into the DRA.42

106th Congress

- In 2000, the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2001 (P.L. 106-554) included language authorizing the creation of the DRA based on the seven participating states of the LMDDC, with the addition of Alabama and 16 of its counties.

107th Congress

- The Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002, or 2002 farm bill (P.L. 107-171), amended voting procedures for DRA states, provided new funds for Delta regional projects, and added four additional Alabama counties to the DRA.

110th Congress

- The Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, or 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-234) reauthorized the DRA from FY2008 through FY2012 and expanded it to include Beauregard, Bienville, Cameron, Claiborne, DeSoto, Jefferson Davis, Red River, St. Mary, Vermillion, and Webster Parishes in Louisiana; and Jasper and Smith Counties in Mississippi.

113th Congress

- The Agricultural Act of 2014, or 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79) reauthorized the DRA through FY2018.

115th Congress

- The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, or 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334), reauthorized the DRA from FY2019 to FY2023,43 and emphasized Alabama's position as a "full member" of the DRA.

Funding History

Under "farm bill" legislation, the DRA has consistently received funding authorizations of $30 million annually since it was first authorized. However, appropriations have fluctuated over the years. Although the DRA was appropriated $20 million in the same legislation authorizing its creation,44 that amount was halved in 2002,45 and continued a downward trend through its funding nadir of $5 million in FY2004. However, funding had increased by FY2006 to $12 million. Since FY2008, DRA's annual appropriations have increased from almost $12 million to the current level of $25 million (Table 3).

|

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

|

|

Appropriated Funding |

11.69 |

13.00 |

13.00 |

11.70 |

11.68 |

11.68 |

12.00 |

12.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

|

Authorized Funding |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

Sources: Appropriated funding amounts compiled by CRS using data from the following: P.L. 110-161; P.L. 111-8; P.L. 111-85; P.L. 112-10; P.L. 112-74; P.L. 112-75; P.L. 113-76; P.L. 113-235; P.L. 114-113; P.L. 115-31; P.L. 115-141; and P.L. 115-244.

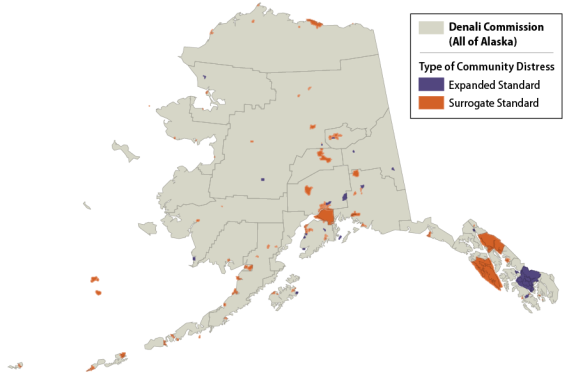

Denali Commission

The Denali Commission was established in 1998 to support rural economic development in Alaska.46 It is "designed to provide critical utilities, infrastructure, and economic support throughout Alaska." The Denali Commission is unique as a single-state commission, and in its reliance on federal funding for both administration and activities.

|

Figure 3. Map of the Denali Commission service area by expanded and surrogate standards of distress |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from the Denali Commission and Esri Data and Maps 2018. |

Overview of Structure and Activities

The commission's statutory mission includes providing workforce and other economic development assistance to distressed rural regions in Alaska. However, the commission no longer engages in substantial activities in general economic development or transportation, which were once core elements of the Denali Commission's activities. Its recent activities are principally limited to coastal infrastructure protection and energy infrastructure and fuel storage projects.

Commission Structure

The Denali Commission's structure is unique as the only commission with a single-state mandate. The commission is comprised of seven members (or a designated nominee), including the federal co-chair, appointed by the U.S. Secretary of Commerce; the Alaska governor, who is state co-chair (or his/her designated representative); the University of Alaska president; the Alaska Municipal League president; the Alaska Federation of Natives president; the Alaska State AFL-CIO president; and the Associated General Contractors of Alaska president.47

These structural novelties offer a different model compared to the organization typified by the ARC and broadly adopted by the other functioning federal regional commissions and authorities. For example, the federal co-chair's appointment by the Secretary of Commerce, and not the President with Senate confirmation, allows for a potentially more expeditious appointment of a federal co-chair.

The Denali Commission is required by law to create an annual work plan, which solicits project proposals, guides activities, and informs a five-year strategic plan.48 The work plan is reviewed by the federal co-chair, the Secretary of Commerce, and the Office of Management and Budget, and is subject to a public comment period. The current FY2018-FY2022 strategic plan, released in October 2017, lists four strategic goals and objectives: (1) facilities management; (2) infrastructure protection from ecological change; (3) energy, including storage, production, heating, and electricity; and (4) innovation and collaboration. The commission's recent activities largely focus on energy and infrastructure protection.49

Distressed Areas

The Denali Commission's authorizing statute obligates the Commission to address economic distress in rural areas of Alaska.50 As of 2018, the Commission utilizes two overlapping standards to assess distress: a "surrogate standard," adopted by the Commission in 2000, and an "expanded standard." These standards are applied to rural communities in Alaska and assessed by the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development (DOL&WD), Research and Analysis Section. DOL&WD uses the most current population, employment, and earnings data available to identify Alaska communities and Census Designated Places considered "distressed."

Appeals can be made to community distress determinations, but only through a demonstration that DOL&WD data or analysis was erroneous, invalid, or outdated. New information "must come from a verifiable source, and be robust and representative of the entire community and/or population." Appeals are accepted and adjudicated only for the same reporting year in question.

Recent Activities

The Denali Commission's scope is more constrained compared to the other federal regional commissions and authorities. The organization reports that due to funding constraints,51 the commission reduced its involvement in what might be considered traditional economic development and, instead, focused on rural fuel and energy infrastructure and coastal protection efforts.52

Since the Denali Commission's founding, bulk fuel safety and security, energy reliability and security, transportation system improvements, and healthcare projects have commanded the vast majority of Commission projects.53 Of these, only energy reliability and security and bulk fuel safety and security projects remain active and are still funded. Village infrastructure protection—a program launched in 2015 to address community infrastructure threatened by erosion, flooding and permafrost degradation—is a program that is relatively new and still being funded.54 By contrast, most "traditional" economic development programs are no longer being funded, including in housing, workforce development, and general economic development activities.55

Legislative History

106th Congress

- In 1999, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2000 (P.L. 106-113) authorized the commission to enter into contracts and cooperative agreements, award grants, and make payments "necessary to carry out the purposes of the commission." The act also established the federal co-chair's compensation schedule, prohibited using more than 5% of appropriated funds for administrative expenses, and established "demonstration health projects" as authorized activities and authorized the Department of Health and Human Services to make grants to the commission to that effect.

108th Congress

- The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2004 (P.L. 108-199) created an Economic Development Committee within the commission chaired by the Alaska Federation of Natives president, and included the Alaska Commissioner of Community and Economic Affairs, a representative of the Alaska Bankers Association, the chairman of the Alaska Permanent Fund, a representative from the Alaska Chamber of Commerce, and representatives from each region.

109th Congress

- In 2005, the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users, or SAFETEA-LU (P.L. 109-59), established the Denali Access System Program among the commission's authorized activities. The program was part of its surface transportation efforts, which were active from 2005 through 2009.56

112th Congress

- 2012's Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act, or MAP-21 (P.L. 112-141), authorized the commission to accept funds from federal agencies, allowed it to accept gifts or donations of "service, property, or money" on behalf of the U.S. government, and included guidance regarding gifts.

114th Congress

- In 2016, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act, or the WIIN Act (P.L. 114-322), reauthorized the Denali Commission through FY2021, and established a four-year term for the federal co-chair (with allowances for reappointment), but provided that other members were appointed for life. The act also allowed for the Secretary of Commerce to appoint an interim federal co-chair, and included clarifying language on the non-federal status of commission staff and ethical issues regarding conflicts of interest and disclosure.

Funding History

Under its authorizing statute, the Denali Commission received funding authorizations for $20 million for FY1999,57 and "such sums as necessary" (SSAN) for FY2000 through FY2003. Legislation passed in 2003 extended the commission's SSAN funding authorization through 2008.58 Its authorization lapsed after 2008; reauthorizing legislation was introduced in 2007,59 but was not enacted. The commission continued to receive annual appropriations for FY2009 and several years thereafter.60 In 2016, legislation was enacted reauthorizing the Denali Commission through FY2021 with a $15 million annual funding authorization (Table 4).61

|

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

|

|

Appropriated Funding |

21.8 |

11.8 |

11.97 |

10.7 |

10.68 |

10.68 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

11.00 |

15.00 |

30.00 |

15.00 |

|

Authorized Funding |

SSAN |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

15.00 |

15.00 |

15.00 |

Source: Appropriated funding amounts compiled by CRS using data from the following: P.L. 110-161; P.L. 111-8; P.L. 111-85; P.L. 112-10; P.L. 112-74; P.L. 112-75; P.L. 113-76; P.L. 113-235; P.L. 114-113; P.L. 115-31; and P.L. 115-14.

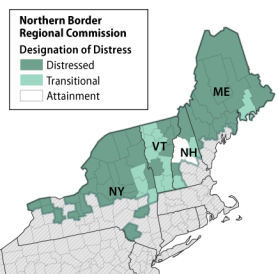

Northern Border Regional Commission

The Northern Border Regional Commission (NBRC) was created by the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, otherwise known as the 2008 farm bill.62 The act also created the Southeast Crescent Regional Commission (SCRC) and the Southwest Border Regional Commission (SBRC). All three commissions share common authorizing language modeled after the ARC.

The NBRC is the only one of the three new commissions that has been both reauthorized and received progressively increasing annual appropriations since it was established in 2008. The NBRC was founded to alleviate economic distress in the northern border areas of Maine, New Hampshire, New York, and, as of 2018, the entire state of Vermont (Figure 4).

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from the NBRC and Esri Data and Maps 2018. Notes: Vermont is the only state with all counties within the NBRC's jurisdiction. |

The stated mission of the NBRC is "to catalyze regional, collaborative, and transformative community economic development approaches that alleviate economic distress and position the region for economic growth."63 Eligible counties within the NBRC's jurisdiction may receive funding "for community and economic development" projects pursuant to regional, state, and local planning and priorities (Table C-4).

Overview of Structure and Activities

The NBRC is led by a federal co-chair, appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, and four state governors, of which one is appointed state co-chair. There is no term limit for the federal co-chair. The state co-chair is limited to two consecutive terms, but may not serve a term of less than one year. Each of the four governors may appoint an alternate; each state also designates an NBRC program manager to handle the day-to-day operations of coordinating, reviewing, and recommending economic development projects to the full membership.64

While program funding depends on congressional appropriations, administrative costs are shared equally between the federal government and the four states of the NBRC. Through commission votes, applications are ranked by priority, and are approved in that order as grant funds allow.

Program Areas

All projects are required to address at least one of the NBRC's four authorized program areas and its five-year strategic plan. The NBRC's four program areas are: (1) economic and infrastructure development (EID); (2) comprehensive planning for states; (3) local development districts; and (4) the regional forest economy partnership.

Economic and Infrastructure Development (EID)

The NBRC's state EID investment program is the chief mechanism for investing in economic development programs in the participating states. The EID program prioritizes projects focusing on infrastructure, telecommunications, energy costs, business development, entrepreneurship, workforce development, leadership, and regional strategic planning.65 The EID program provides approximately $3.5 million to each state for such activities. Eligible applicants include public bodies, 501(c) organizations, Native American tribes, and the four state governments. EID projects may require matching funds of up to 50% depending on the level of distress.

Comprehensive Planning

The NBRC may also assist states in developing comprehensive economic and infrastructure development plans for their NBRC counties. These initiatives are undertaken in collaboration with LDDs, localities, institutions of higher education, and other relevant stakeholders.66

Local Development Districts (LDD)

The NBRC uses 16 multicounty LDDs to advise on local priorities, identify opportunities, conduct outreach, and administer grants, from which the LDDs receive fees.67 LDDs receive fees according to a graduated schedule tied to total project funds. The rate is 5% for the first $100,000 awarded and 1% in excess of $100,000. Notably, this formula does not apply to Vermont-only projects. Vermont is the only state where grantees are not required to contract with an LDD for the administration of grants, though this requirement may be waived.68

Regional Forest Economy Partnership (RFEP)

The RFEP is an NBRC program to address economic distress caused by the decline of the regional forest products industry.69 The program provides funding to rural communities for "economic diversity, independence, and innovation." The NBRC received $7 million in FY2018 and FY2019 to address the decline in the forest-based economies in the NBRC region.70

Strategic Plan

The NBRC's activities are guided by a five-year strategic plan,71 which is developed through "extensive engagement with NBRC stakeholders" alongside "local, state, and regional economic development strategies already in place." The 2017-2021 strategic plan lists three goals:

- 1. modernizing infrastructure;

- 2. creating and sustaining jobs; and

- 3. anticipating and capitalizing on shifting economic and demographic trends.72

The strategic plan also lists five-year performance goals, which are:

- 5,000 jobs created or retained;

- 10,000 households and businesses with access to improved infrastructure;

- 1,000 businesses representing 5,000 employees benefit from NBRC investments;

- 7,500 workers provided with skills training;

- 250 communities and 1,000 leaders engaged in regional leadership, learning and/or innovation networks supported by the NBRC; and

- 3:1 NBRC investment leverage.73

The strategic plan also takes stock of various socioeconomic trends in the northern border region, including (1) population shifts; (2) distressed communities; and (3) changing workforce needs.

Economic and Demographic Distress

The NBRC is unique in that it is statutorily obligated to assess distress according to economic as well as demographic factors (Table C-4). These designations are made and refined annually. The NBRC defines levels of "distress" for counties that "have high rates of poverty, unemployment, or outmigration" and "are the most severely and persistently economic distressed and underdeveloped."74 The NBRC is required to allocate 50% of its total appropriations to projects in distressed counties.75

The NBRC's county designations are as follows, in descending levels of distress:

- Distressed counties (80% maximum funding allowance);

- Transitional counties (50%); and

- Attainment (0%).

Transitional counties are defined as counties that do not exhibit the same levels of economic and demographic distress as a distressed county, but suffer from "high rates of poverty, unemployment, or outmigration." Attainment counties are not allowed to be funded by the NBRC except for those projects that are located within an "isolated area of distress," or have been granted a waiver.76

Distress is calculated in tiers of primary and secondary distress categories and constituent factors:

- Primary Distress Categories

- 1. Percent of population below the poverty level

- 2. Unemployment rate

- 3. Percent change in population

- Secondary Distress Categories

- 4. Percent of population below the poverty level

- 5. Median household income

- 6. Percent of secondary and/or seasonal homes

Each county is assessed by the primary and secondary distress categories and factors and compared to the figures for the United States as a whole. Designations of county distress are made by tallying those factors against the following criteria:

- Distressed counties are those with at least three factors from both primary and secondary distress categories and at least one from each category;

- Transitional counties are those with at least one factor from either category; and

- Attainment counties are those which show no measures of distress.

Legislative History

110th Congress

- The NBRC was first proposed in the Northern Border Economic Development Commission Act of 2007 (H.R. 1548), introduced on March 15, 2007. H.R. 1548 proposed the creation of a federally-chartered, multi-state economic development organization—modeled after the ARC—covering designated northern border counties in Maine, New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont. The bill would have authorized the appropriation of $40 million per year for FY2008 through FY2012 (H.R. 1548). The bill received regional co-sponsorship from Members of Congress representing areas in the northern border region.77

- The NBRC was reintroduced in the Regional Economic and Infrastructure Development Act of 2007 (H.R. 3246), which would have authorized the NBRC, the SCRC, and the SBRC, and reauthorized the DRA and the NGPRA (discussed in the next section) in a combined bill.78 H.R. 3246 won a broader range of support, which included 18 co-sponsors in addition to the original bill sponsor, and passed the House by a vote of 264-154 on October 4, 2007.

- Upon House passage, H.R. 3246 was referred to the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. The Senate incorporated authorizations for the establishment of the NBRC, SCRC, and the SBRC in the 2008 farm bill.79 The 2008 farm bill authorized annual appropriations of $30 million for FY2008 through FY2012 for all three new commissions.

115th Congress

- The only major changes to the NBRC since its creation were made in the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334), or the 2018 farm bill, which authorized the state capacity building grant program.

- In addition, the 2018 farm bill expanded the NBRC to include the following counties: Belknap and Cheshire counties in New Hampshire; Genesee, Greene, Livingston, Montgomery, Niagara, Oneida, Orleans, Rensselaer, Saratoga, Schenectady, Sullivan, Washington, Warren, Wayne, and Yates counties in New York; and Addison, Bennington, Chittenden, Orange, Rutland, Washington, Windham, and Windsor counties in Vermont, making it the only state entirely within the NBRC.

Funding History

Since its creation, the NBRC has received consistent authorizations of appropriations (Table 5). The 2008 farm bill authorized the appropriation of $30 million for the NBRC for each of FY2008 through FY2013 (P.L. 110-234); the same in the 2014 farm bill for each of FY2014 through FY2018 (P.L. 113-79); and $33 million for each of FY2019 through FY2023 (P.L. 115-334).

Due to its statutory linkages to the SCRC and SBRC, all three commissions also share common authorizing legislation and identical funding authorizations. To date, the NBRC is the only commission of the three to receive substantial annual appropriations. Congress has funded the NBRC since FY2010 (Table 5). The NBRC's appropriated funding level has increased from $5 million in FY2014,80 to $7.5 million in FY2016,81 $10 million in FY2017,82 $15 million in FY2018,83 and $20 million in FY2019.84

|

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

|

|

Appropriated Funding |

— |

— |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

7.5 |

10.0 |

15.0 |

20.0 |

|

Authorized Funding |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

33.0 |

Sources: Authorized funding amounts compiled by CRS using data from P.L. 110-234, P.L. 113-79, and P.L. 115-334. Appropriated funding amounts compiled by CRS using data from the following: P.L. 111-85; P.L. 112-10; P.L. 112-74; P.L. 113-6; P.L. 113-76; P.L. 113-235; P.L. 114-113; P.L. 115-31; P.L. 115-141; and P.L. 115-244.

Northern Great Plains Regional Authority

The Northern Great Plains Regional Authority was created by the 2002 farm bill.85 The NGPRA was created to address economic distress in Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri (other than counties included in the Delta Regional Authority), North Dakota, Nebraska, and South Dakota.

|

Figure 5. Map of the Northern Great Plains Regional Authority |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using the NGPRA jurisdiction defined in P.L. 107-171 and Esri Data and Maps 2018. Notes: Missouri's jurisdiction was defined as those counties not already included in the DRA. |

The NGPRA appears to have been briefly active shortly after it was created, when it received its only annual appropriation from Congress. The NGPRA's funding authorization lapsed at the end of FY2018; it was not reauthorized.

Structure and Activities

Authority Structure

The NGPRA featured broad similarities to the basic structure shared among most of the federal regional authorities and commissions, being a federal-state partnership led by a federal co-chair (appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate) and governors of the participating states, of which one was designated as the state co-chair.

Unique to the NGPRA were certain structural novelties reflective of regional socio-political features. The NGPRA also included a Native American tribal co-chair, who was the chairperson of an Indian tribe in the region (or their designated representative), and appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate. The tribal co-chair served as the "liaison between the governments of Indian tribes in the region and the [NGPRA]." No term limit is established in statute; the only term-related proscription is that the state co-chair "shall be elected by the state members for a term of not less than 1 year."

Another novel feature among the federal regional commissions and authorities was also the NGPRA's statutory reliance on a 501(c)(3) non-profit corporation—Northern Great Plains, Inc.—in furtherance of its mission. While Northern Great Plains, Inc. was statutorily organized to complement the NGPRA's activities, it effectively served as the sole manifestation of the NGPRA concept and rationale while it was active, given that the NGPRA was only once appropriated funds and never appeared to exist as an active organization. The Northern Great Plains, Inc. was active for several years, and reportedly received external funding,86 but is currently defunct.

Activities and Administration

Under its authorizing statute,87 the federal government would initially fund all administrative costs in FY2002, which would decrease to 75% in FY2003, and 50% in FY2004. Also, the NGPRA would have designated levels of county economic distress; 75% of funds were reserved for the most distressed counties in each state, and 50% reserved for transportation, telecommunications, and basic infrastructure improvements. Accordingly, non-distressed communities were eligible to receive no more than 25% of appropriated funds.

The NGPRA was also structured to include a network of designated, multi-county LDDs at the sub-state levels. As with its sister organizations, the LDDs would have served as nodes for project implementation and reporting, and as advisors to their respective states and the NGPRA as a whole.

Legislative History

103rd Congress

- The Northern Great Plains Rural Development Act (P.L. 103-318), which became law in 1994, established the Northern Great Plains Rural Development Commission to study economic conditions and provide economic development planning for the Northern Great Plains region. The Commission was comprised of the governors (or designated representative) from the Northern Great Plains states of Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, Nebraska, and South Dakota (prior to Missouri's inclusion), along with one member from each of those states appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture.

104th Congress

- The Agricultural, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1995 (P.L. 103-330) provided $1,000,000 to carry out the Northern Great Plains Rural Development Act. The Commission produced a 10-year plan to address economic development and distress in the five states. After a legislative extension (P.L. 104-327), the report was submitted in 1997.88 The Northern Great Plains Initiative for Rural Development (NGPIRD), a non-profit 501(c)(3), was established to implement the Commission's advisories.

107th Congress

- The Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002, or 2002 farm bill (P.L. 107-171), authorized the NGPRA, which superseded the Commission. The statute also created Northern Great Plains, Inc., a 501(c)(3), as a resource for regional issues and international trade, which supplanted the NGPIRD with a broader remit that included research, education, training, and issues of international trade.

110th Congress

- The Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, or 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-246), extended the NGPRA's authorization through FY2012. The legislation also expanded the authority to include areas of Missouri not covered by the DRA, and provided mechanisms to enable the NGPRA to begin operations even without the Senate confirmation of a federal co-chair, as well as in the absence of a confirmed tribal co-chair.

- The Agricultural Act of 2014, or 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79), reauthorized the NGPRA and the DRA, and extended their authorizations from FY2012 to FY2018.

Funding History

The NGPRA was authorized to receive $30 million annually from FY2002 to FY2018. It received appropriations once for $1.5 million in FY2004.89 Its authorization of appropriations lapsed at the end of FY2018.

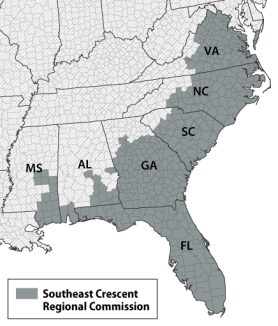

Southeast Crescent Regional Commission

The Southeast Crescent Regional Commission (SCRC) was created by the 2008 farm bill,90 which also created the NBRC and the Southwest Border Regional Commission. All three commissions share common authorizing language modeled after the ARC.

The SCRC is not currently active. The SCRC was created to address economic distress in areas of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida (Figure 6) not served by the ARC or the DRA (Table 13).

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using the jurisdiction defined in P.L. 110-234 and Esri Data and Maps 2018. Notes: The SCRC is statutorily defined as including those counties in the named states that are not already included in the ARC or the DRA. Florida is the only state with all counties are defined as being within the SCRC. |

Overview of Structure and Activities

As authorized, the SCRC would share an organizing structure with the NBRC and the Southwest Border Regional Commission, as all three share common statutory authorizing language modeled after the ARC.

As authorized, the SCRC would consist of a federal co-chair, appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, along with the participating state governors (or their designated representatives), of which one would be named by the state representatives as state co-chair. There is no term limit for the federal co-chair. However, the state co-chair is limited to two consecutive terms, but may not serve a term of less than one year. However, no federal co-chair has been appointed since the SCRC was authorized; therefore, the commission cannot form and begin operations.

Legislative History

The SCRC concept was first introduced by university researchers working on rural development issues in 1990 at Tuskegee University's Annual Professional Agricultural Worker's Conference for 1862 and 1890 Land-Grant Universities.

In 1994, the Southern Rural Development Commission Act was introduced in the House Agricultural Committee, which would provide the statutory basis for a "Southern Black Belt Commission."91 While the concept was not reintroduced in Congress until the 2000s, various nongovernmental initiatives sustained discussion and interest in the concept in the intervening period. Supportive legislation was reintroduced in 2002, which touched off other accompanying legislative efforts until the SCRC was authorized in 2008.92

Funding History

Congress authorized $30 million funding levels for each fiscal year from FY2008 to FY2018, and $33 million in FY2019, and appropriated $250,000 in each fiscal year from FY2010 to FY2019 (Table 5). Despite receiving regular appropriations since it was authorized in 2008, a review of government budgetary and fiscal sources yields no record of the SCRC receiving, obligating, or spending funds appropriated by Congress. In successive presidential administration budget requests (FY2013, FY2015-FY2017), no funding was requested.93

In the U.S. Treasury 2018 Combined Statement of Receipts, Outlays, and Balances, Part III,94 the SCRC does not appear, further indicating that the SCRC remains unfunded. Notably, the Commission for the Preservation of America's Heritage Abroad, which has periodically shared a common section with the SCRC in presidential budgets, is listed in the 2018 Combined Statement, as it is elsewhere.

|

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

|

|

Appropriated Funding |

— |

— |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

|

Authorized Funding |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

30.00 |

33.00 |

Sources: Appropriated funding amounts compiled by CRS using data from the following: P.L. 111-85; P.L. 112-10; P.L. 112-74; P.L. 113-6; P.L. 113-76; P.L. 113-235; P.L. 114-113; P.L. 115-31; P.L. 115-141; and P.L. 115-244.

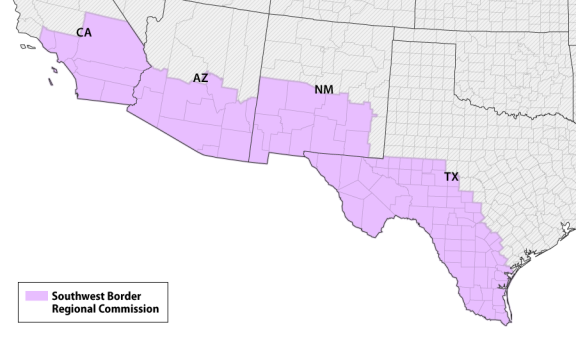

Southwest Border Regional Commission

The Southwest Border Regional Commission (SBRC) was created with the enactment of the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, or the 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-234), which also created the NBRC and the SCRC. All three commissions share common statutory authorizing language modeled after the ARC.

The SBRC was created to address economic distress in the southern border regions of Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas (Figure 7; Table 15). The SBRC has not received an annual appropriation since it was created and is not currently active.

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using the jurisdictional data defined in P.L. 110-234 and Esri Data and Maps 2018. |

Overview of Structure and Activities

As authorized, the SBRC would share an organizing structure with the NBRC and the SCRC, as all three commissions share common statutory authorizing language modeled after the ARC.

By statute, the SBRC consists of a federal co-chair, appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, along with the participating state governors (or their designated representatives), of which one would be named by the state representatives as state co-chair. As enacted in statute, there is no term limit for the federal co-chair. However, the state co-chair is limited to two consecutive terms, but may not serve a term of less than one year. However, as no federal co-chair has been appointed since the SCRC was authorized, it is not operational.

Legislative History

The concept of an economic development agency focusing on the southwest border region has existed at least since 1976, though the SBRC was established through more recent efforts.

- Executive Order 13122 in 1999 created the Interagency Task Force on the Economic Development of the Southwest Border,95 which examined issues of socioeconomic distress and economic development in the southwest border regions and advised on federal efforts to address them.

108th Congress

- In February 2003, a "Southwest Regional Border Authority" was proposed in S. 548. A companion bill, H.R. 1071, was introduced in March 2003. The SBRC was reintroduced in the Regional Economic and Infrastructure Development Act of 2003 (H.R. 3196), which would have authorized the SBRC, the DRA, the NGPRA, and the SCRC.

109th Congress

- In 2006, the proposed Southwest Regional Border Authority Act would have created the "Southwest Regional Border Authority" (H.R. 5742 ), similar to S. 458 in 2003.

110th Congress

- In 2007, SBRC was reintroduced in the Regional Economic and Infrastructure Development Act of 2007 (H.R. 3246), which would have authorized the SBRC, the SCRC, and the NBRC, and reauthorized the DRA and the NGPRA in a combined bill.

- Upon House passage, the Senate incorporated authorizations for the establishment of the NBRC, SCRC, and SBRC in the 2008 farm bill. The 2008 farm bill authorized annual appropriations of $30 million for FY2008 through FY2012 for all three of the new organizations.

Funding History

Congress authorized annual funding of $30 million for the SBRC from FY2008 to FY2018, and $33 million in FY2019. The SBRC has never received annual appropriations and is not active.

Concluding Notes

Given their geographic reach, broad activities, and integrated intergovernmental structures, the federal regional commissions and authorities are a significant element of federal economic development efforts. At the same time, as organizations that are largely governed by the respective state-based commissioners, the federal regional commissions and authorities are not typical federal agencies but federally-chartered entities that integrate federal funding and direction with state and local economic development priorities.

This structure provides Congress with a flexible platform for economic development efforts. The intergovernmental structure allows for strategic-level economic development initiatives to be launched at the federal level and implemented across multi-state jurisdictions with extensive state and local input, and more adaptable to regional needs.

The federal regional commissions and authorities reflect an emphasis by the federal government on place-based economic development strategies sensitive to regional and local contexts. However, the geographic specificity and varying functionality of the statutorily authorized federal regional commissions and authorities, both active and inactive, potentially raise questions about the efficacy and equity of federal economic development policies.

More in-depth analysis of these and other such issues related to the federal regional authorities and commissions, and their role as instruments for federal economic development efforts, is reserved for possible future companion products to this report.

Appendix A. Basic Information at a Glance

|

Year |

Number of States |

Number of |

FY2019 Appropriations |

|

|

ARC |

1965 |

13 |

420, which includes the entire state of West Virginia |

$165.00 |

|

DRA |

2000 |

8 |

252 |

$30.00 |

|

Denali Commission |

1998 |

1 |

Entire state of Alaska |

$15.00 |

|

NBRC |

2008 |

4 |

60 |

$20.00 |

|

NGPRC |

2002 |

6 |

86 counties in Missouri and the entire states of Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, Nebraska, and South Dakota |

N/A |

|

SCRC |

2008 |

7 |

384 counties in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and the entire state of Florida |

$0.25 |

|

SBRC |

2008 |

4 |

93 |

N/A |

Sources: Data compiled by CRS from relevant legislation and official sources of various federal regional commissions and authorities. Authorizing statutes include, in order of tabulation: P.L. 89-4; P.L. 106-554; P.L. 105-277; P.L. 110-234; P.L. 107-171; P.L. 110-234; and P.L. 110-234.

Notes: The commissions and authorities in bold are considered to be active and functioning.

(for active commissions and authorities)

Appalachian Regional Commission

Address:1666 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Suite 700

Washington, DC 20009-1068

Phone:[phone number scrubbed]

Website:http://www.arc.gov

Address:236 Sharkey Avenue

Suite 400

Clarksdale, MS 38614

Phone:[phone number scrubbed]

Website:http://www.dra.gov

Address:510 L Street

Suite 410

Anchorage, AK 99501

Phone:[phone number scrubbed]

Website:http://www.denali.gov

Northern Border Regional Commission

Address:James Cleveland Federal Building, Suite 1201

53 Pleasant Street

Concord, NH 03301

Phone:[phone number scrubbed]

Website:http://www.NBRC.gov

Appendix B. Map of Federal Regional Commissions and Authorities

|

Figure B-1. National Map of the Federal Regional Commissions and Authorities by county |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from the various commission and authorities and Esri Data and Maps 2018. |

Appendix C. Service Areas of Federal Regional Commissions and Authorities

Appalachian Regional Commission

Source: Information compiled by CRS from ARC data.

Delta Regional Authority

|

Distressed Counties |

Non-Distressed Counties |

|

|

Alabama |

Barbour, Bullock, Butler, Choctaw, Clarke, Conecuh, Dallas, Escambia, Greene, Hale, Lowndes, Macon, Marengo, Monroe, Perry, Pickens, Russell, Sumter, Washington, Wilcox |

|

|

Arkansas |

Ashley, Baxter, Bradley, Calhoun, Chicot, Clay, Cleveland, Craighead, Crittenden, Cross, Dallas, Desha, Drew, Fulton, Grant, Greene, Independence, Izard, Jackson, Jefferson, Lawrence, Lee, Lincoln, Lonoke, Marion, Mississippi, Monroe, Ouachita, Phillips, Poinsett, Prairie, Randolph, Searcy, Sharp, St. Francis, Stone, Union, Van Buren, White, Woodruff |

Arkansas, Pulaski |

|

Illinois |

Alexander, Franklin, Gallatin, Hardin, Jackson, Johnson, Massac, Perry, Pope, Pulaski, Randolph, Saline, Union |

Hamilton, White, Williamson |

|

Kentucky |

Ballard,Caldwell, Calloway, Carlisle, Christian, Crittenden, Fulton, Graves, Henderson, Hickman, Hopkins, Livingston, Lyon, McCracken, McLean, Marshall, Muhlenberg, Todd, Trigg, Union, Webster |

|

|

Louisiana |

Acadia, Allen, Assumption, Avoyelles, Beauregard, Bienville, Caldwell, Catahoula, Claiborne, Concordia, De Soto, East Carroll, Evangeline, Franklin, Grant, Iberia, Iberville, Jackson, Jefferson Davis, La Salle, Lincoln, Livingston, Madison, Morehouse, Natchitoches, Ouachita, Pointe Coupee, Rapides, Red River, Richland, St. Bernard, St. Helena, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Landry, St. Martin, St. Mary, Tangipahoa, Tensas, Union, Vermillion, Washington, Webster, West Carroll, West Feliciana, Winn |

Ascension, Cameron, East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, Jefferson, Lafourche, Orleans, Plaquemines, St. Charles, West Baton Rouge |

|

Mississippi |

Adams, Amite, Attala, Benton, Bolivar, Carroll, Claiborne, Coahoma, Copiah, Covington, De Soto, Franklin, Grenada, Hinds, Holmes, Humphreys, Issaquena, Jasper, Jefferson, Jefferson Davis, Lafayette, Lawrence, Leflore, Lincoln, Marion, Marshall, Montgomery, Panola, Pike, Quitman, Sharkey, Simpson, Smith, Sunflower, Tallahatchie, Tate, Tippah, Tunica, Union, Walthall, Warren, Washington, Wilkinson, Yalobusha, Yazoo |

Madison, Rankin |

|

Missouri |

Bollinger, Butler, Carter, Crawford, Dent, Douglas, Dunklin, Howell, Iron, Madison, Mississippi, New Madrid, Oregon, Ozark, Pemiscot, Perry, Phelps, Reynolds, Ripley, Scott, Shannon, Ste. Genevieve, St. Francois, Stoddard, Texas, Washington, Wayne, Wright |

Cape Girardeau |

|

Tennessee |

Benton, Carroll, Chester, Crockett, Decatur, Dyer, Gibson, Hardeman, Hardin, Haywood, Henderson, Henry, Lake, Lauderdale, McNairy, Obion, Tipton, Weakley |

Fayette, Madison, Shelby |

Source: Compiled by CRS from the Delta Regional Authority website.

Denali Commission

Table C-3. Denali Commission Distressed Communities List

by standard of community distress, in alphabetical order

|

Surrogate Standard |

Anchorage, Anderson, Aniak, Atka, Atqasuk, Badger, Bear Creek, Bethel, Bettles, Butte, Chena Ridge, Chignik, Chignik Lagoon, Cold Bay, Coldfoot, College, Cordova, Craig City, Deering, Dillingham, Diomede, Egegik, Ester, Evansville, Fairbanks, False Pass, Farm Loop, Farmers Loop, Fishhook, Four Mile Road, Fox, Galena, Gateway, Golovin, Gulkana, Healy, Hobart Bay, Igiugig, Iliamna, Juneau, Kaktovik, Kalifornsky, Karluk, Kasaan, Kenai, Ketchikan, King Cove, King Salmon, Klawock, Knik River, Knik-Fairview, Kodiak, Kotzebue, Lakes, Larsen Bay, Lazy Mountain, Lowell Point, Meadow Lakes, Metlakatla, Naknek, Newhalen, Nikiski, Nikolski, Nome, North Pole, Nuiqsut, Paxon, Pedro Bay, Petersville, Pilot Point, Pleasant Valley, Point Lay, Port Heiden, Prudhoe Bay, Rampart, Ridgeway, Sand Point, Seward, Sitka, Skagway, Soldotna, St. George, St. Paul, Steele Creek, Sterling, Sunrise, Tanaina, Tazlina, Tolsona, Two Rivers, Unalakleet, Unalaska, Utqiagvik, Valdez, Wasilla, Whittier, Womens Bay, Yakutat |

|

Expanded Standard |

Buffalo Soapstone, Chenega, Chiniak, Clam Gulch, Delta Junction, Eureka Roadhouse, Gakona, Haines, Hollis, Homer, Kasilof, McGrath, Moose Pass, Nenana, Noatak, Northway, Petersburg, Platinum, South Van Horn, Sutton-Alpine, Wrangell |

Source: 2018 Distressed Communities Report, Denali Commission.

Northern Border Regional Commission

|

Attainment |

Transitional |

Distressed |

|

|

Maine |

Hancock |

Androscoggin, Aroostook, Franklin, Kennebec, Knox, Oxford, Penobscot, Piscataquis, Somerset, Waldo, Washington |

|

|

New Hampshire |

Grafton, Belknap |

Carroll, Cheshire |

Coos, Sullivan |

|

New York |

Rensselaer, Saratoga, Schenectady, Warren |

Cayuga, Clinton, Essex, Franklin, Fulton, Genesee, Greene, Hamilton, Herkimer, Jefferson, Lewis, Livingston, Madison, Montgomery, Niagara, Oneida, Orleans, Oswego, St. Lawrence, Seneca, Sullivan, Washington, Wayne, Yates |

|

|

Vermont |

Addison, Bennington, Chittenden, Franklin, Grand Isle, Lamoille, Washington, Windham, Windsor |

Caledonia, Essex, Orange, Orleans, Rutland |

Source: Compiled and tabulated by CRS from NBRC data.

Notes: Vermont is the only NBRC state with all counties within the NBRC jurisdiction.

Northern Great Plains Regional Authority

|

NGPRA Jurisdiction |

|

|

Iowa |

Entire State |

|

Minnesota |

Entire State |

|

Missouri |

Adair, Andrew, Atchison, Audrain, Barry, Barton, Bates, Benton, Boone, Buchanan, Caldwell, Callaway, Camden, Carroll, Cass, Cedar, Chariton, Christian, Clark, Clay, Clinton, Cole, Cooper, Dade, Dallas, Daviess, DeKalb, Franklin, Gasconade, Gentry, Greene, Grundy, Harrison, Henry, Hickory, Holt, Howard, Jackson, Jasper, Jefferson, Johnson, Knox, Laclede, Lafayette, Lawrence, Lewis, Lincoln, Linn, Livingston, Macon, Maries, Marion, McDonald, Mercer, Miller, Moniteau, Monroe, Montgomery, Morgan, Newton, Nodaway, Osage, Pettis, Pike, Platte, Polk, Pulaski, Putnam, Ralls, Randolph, Ray, Saline, Schuyler, Scotland, Shelby, St. Charles, St. Clair, St. Louis, St. Louis City, Stone, Sullivan, Taney, Vernon, Warren, Webster, Worth |

|

Nebraska |

Entire State |

|

Entire State |

|

|

South Dakota |

Entire State |

Source: Tabulated by CRS with information from P.L. 107-171.

Notes: Missouri jurisdiction represents all those counties not currently included in the DRA.

Southeast Crescent Regional Commission

|

SCRC Jurisdiction |

|

|

Alabama |

Autauga, Baldwin, Coffee, Covington, Crenshaw, Dale, Geneva, Henry, Houston, Lee, Mobile, Montgomery County, Pike |

|

Georgia |

Appling, Atkinson, Bacon, Baker, Baldwin, Ben Hill, Berrien, Bibb, Bleckley, Brantley, Brooks, Bryan, Bulloch, Burke, Butts, Calhoun, Camden, Candler, Charlton, Chatham, Chattahoochee, Clarke, Clay, Clayton, Clinch, Cobb, Coffee, Colquitt, Columbia, Cook, Coweta, Crawford, Crisp, De Kalb, Decatur, Dodge, Dooly, Dougherty, Early, Echols, Effingham, Emanuel, Evans, Fayette, Fulton, Glascock, Glynn, Grady, Greene, Hancock, Harris, Henry, Houston, Irwin, Jasper, Jeff Davis, Jefferson, Jenkins, Johnson, Jones, Lamar, Lanier, Laurens, Lee, Liberty, Lincoln, Long, Lowndes, Macon, Marion, McDuffie, McIntosh, Meriwether, Miller, Mitchell, Monroe, Montgomery, Morgan, Muscogee, Newton, Oconee, Oglethorpe, Peach, Pierce, Pike, Pulaski, Putnam, Quitman, Randolph, Richmond, Rockdale, Schley, Screven, Seminole, Spalding, Stewart, Sumter, Talbot, Taliaferro, Tattnall, Taylor, Telfair, Terrell, Thomas, Tift, Toombs, Treutlen, Troup, Turner, Twiggs, Upson, Walton, Ware, Warren, Washington, Wayne, Webster, Wheeler, White, Whitfield, Wilcox, Wilkes, Wilkinson, Worth |

|

Mississippi |

Clarke, Forrest, George, Greene, Hancock, Harrison, Jackson, Jones, Lamar, Lauderdale, Leake, Neshoba, Newton, Pearl River, Perry, Scott, Stone, Wayne |

|

North Carolina |

Alamance, Anson, Beaufort, Bertie, Bladen, Brunswick, Cabarrus, Camden, Carteret, Caswell, Catawba, Chatham, Chowan, Clay, Cleveland, Columbus, Craven, Cumberland, Currituck, Dare, Davidson, Duplin, Durham, Edgecombe, Franklin, Gaston, Gates, Granville, Greene, Guilford, Halifax, Harnett, Hertford, Hoke, Hyde, Iredell, Johnston, Jones, Lee, Lenoir, Lincoln, Martin, Mecklenburg, Montgomery, Moore, Nash, New Hanover, Northampton, Onslow, Orange, Pamlico, Pasquotank, Pender, Perquimans, Person, Pitt, Randolph, Richmond, Robeson, Rockingham, Rowan, Rutherford, Sampson, Scotland, Stanly, Tyrrell, Union, Vance, Wake, Warren, Washington, Wayne, Wilson |

|

South Carolina |

Abbeville, Aiken, Allendale, Bamberg, Barnwell, Beaufort, Berkeley, Calhoun, Charleston, Chester, Chesterfield, Clarendon, Colleton, Darlington, Dillon, Dorchester, Edgefield, Fairfield, Florence, Georgetown, Greenwood, Hampton, Horry, Jasper, Kershaw, Lancaster, Laurens, Lee, Lexington, Marion, Marlboro, McCormick, Newberry, Orangeburg, Richland, Saluda, Sumter, Union, Williamsburg, York |

|

Virginia |

Accomack, Albemarle, Alexandria city, Amelia, Amherst, Appomattox, Arlington, Augusta, Bedford, Brunswick, Buckingham, Campbell, Caroline, Charles City*, Charlotte, Charlottesville city, Chesapeake city, Chesterfield, Clarke, Colonial Heights city, Culpeper, Cumberland, Danville city, Dinwiddie, Emporia city, Essex, Fairfax, Fairfax City, Falls Church city, Fauquier, Fluvanna, Franklin, Franklin city, Frederick, Fredericksburg city, Gloucester, Goochland, Greene, Greensville, Halifax, Hampton city, Hanover, Harrisonburg city, Henrico, Hopewell city, Isle Of Wight, James City*, King And Queen, King George, King William, Lancaster, Loudoun, Louisa, Lunenburg, Lynchburg city, Madison, Manassas city, Manassas Park city, Mathews, Mecklenburg, Middlesex, Nelson, New Kent, Newport News city, Norfolk city, Northampton, Northumberland, Nottoway, Orange, Page, Petersburg city, Pittsylvania, Poquoson city, Portsmouth city, Powhatan, Prince Edward, Prince George, Prince William, Rappahannock, Richmond, Richmond city, Roanoke, Roanoke city, Rockingham, Shenandoah, South Boston city, Southampton, Spotsylvania, Stafford, Staunton city, Suffolk city, Surry, Sussex, Virginia Beach city, Warren, Waynesboro city, Westmoreland, Williamsburg city, Winchester city, York |

|

Florida |

Entire State |

Source: Tabulated by CRS by cross-referencing relevant state counties against ARC and DRA jurisdictions.

Notes: With the exception of Florida, which has no coverage in another federally-chartered regional commission or authority, SCRC jurisdiction encompasses all member state counties that are not part of the DRA and/or the ARC. In Virginia, independent cities (in bold) are considered counties for U.S. census purposes and are eligible for independent inclusion. Virginia counties with an asterisk (*) are named as cities, but are actually counties (e.g., James City County).

Southwest Border Regional Commission

|

SBRC Jurisdiction |

|

|

Arizona |

Cochise, Gila, Graham, Greenlee, La Paz, Maricopa, Pima, Pinal, Santa Cruz, Yuma |

|

California |

Imperial, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, Ventura |

|

New Mexico |

Catron, Chaves, Dona Ana, Eddy, Grant, Hidalgo, Lincoln, Luna, Otero, Sierra, Socorro |

|

Texas |

Atascosa, Bandera, Bee, Bexar, Brewster, Brooks, Cameron, Coke, Concho, Crane, Crockett, Culberson, Dimmit, Duval, Ector, Edwards, El Paso, Frio, Gillespie, Glasscock, Hidalgo, Hudspeth, Irion, Jeff Davis, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kendall, Kenedy, Kerr, Kimble, Kinney, Kleberg, La Salle, Live Oak, Loving, Mason, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Menard, Midland, Nueces, Pecos, Presidio, Reagan, Real, Reeves, San Patricio, Shleicher, Sutton, Starr, Sterling, Terrell, Tom Green, Upton, Uvalde, Val Verde, Ward, Webb, Willacy, Wilson, Winkler, Zapata, Zavala |

Source: Tabulated by CRS with information from P.L. 110-234.