Introduction

The Social Security system provides monthly benefits to qualified retirees, disabled workers, and their spouses and dependents; it also provides monthly benefits to qualified survivors of deceased workers. Before 1984, Social Security benefits were exempt from the federal income tax. Congress passed legislation in 1983 to tax a portion of Social Security and Railroad Retirement Tier I benefits, with the share of benefits subject to taxation gradually increasing as a person's income rose above a specified income threshold.1 In 1993, a second income threshold was added that increased the taxable share of benefits. These two thresholds are often referred to as first tier and second tier.

In the congressional debate leading to the Social Security Amendments of 1983 and the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 (OBRA 1993), the committee reports noted a desire to

- treat Social Security benefits more like private pension benefits, in which benefits are subject to income tax except for the portion attributable to the individual's own contributions to the system (on which the individual had already paid income tax);

- protect lower-income beneficiaries from taxation of benefits; and

- improve the Social Security program's solvency.2

Today, approximately half of Social Security beneficiaries pay federal income taxes on a portion of their benefits. That percentage is projected to increase over time because the income thresholds used to determine the taxable share of benefits are not indexed for inflation or wage growth.

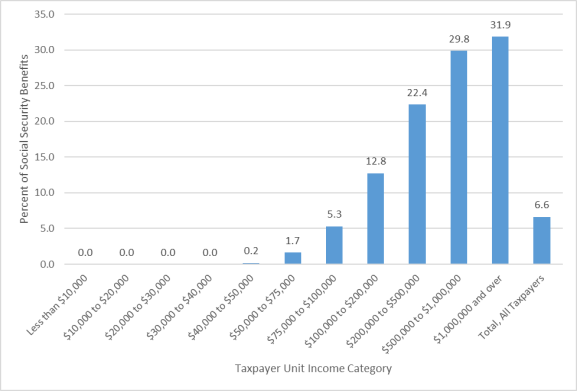

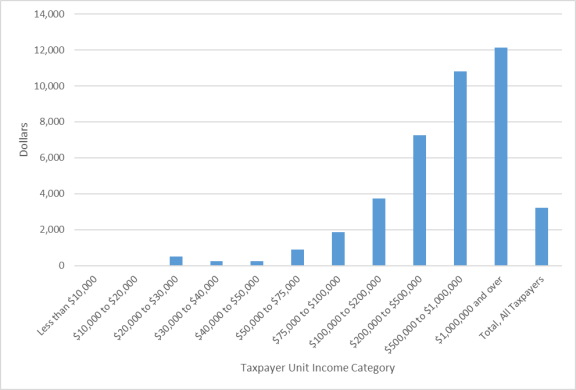

In 2020, Social Security tax liability (federal income taxes owed on Social Security benefits) is projected to be 6.6% of Social Security benefits, with higher tax liabilities associated with higher income categories. Among affected taxpayer units, the average dollar value of Social Security tax liability is projected to be $3,211, again with higher projected tax liabilities for those in higher income brackets.

Overall in 2016, 31.4% of all Social Security benefit payments were taxable. Revenue from the federal taxation of benefits is directed to the Social Security trust funds, the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund, and the Railroad Retirement system,3 and it makes up 3.5%, 7.9%, and 2.3% of total income to the respective systems. In 2028, income from the taxation of benefits is projected to reach 5.7% of revenue to the Social Security trust funds and 12.4% of revenue to the Medicare HI trust fund.

This report details the rules for determining the portion of Social Security benefits subject to federal income taxation, provides statistics about Social Security benefits subject to taxation and the amount of taxes owed, and discusses the impacts on the Social Security and Medicare HI trust funds. It also explains the history of the federal income taxation of Social Security benefits and briefly describes current legislative proposals that would change the taxation of Social Security benefits.

Determining the Portion of Social Security Benefits Subject to Federal Income Taxation

In general, about half of Social Security beneficiaries pay federal income taxes on a portion of their benefits. Up to 85% of Social Security benefits can be included in taxable income for recipients whose "provisional income" exceeds either of two statutory thresholds (based on filing status).4

Provisional income is adjusted gross income,5 plus certain otherwise tax-exempt income (tax-exempt interest), plus the addition of certain income specifically excluded from federal income taxation (interest on certain U.S. savings bonds,6 employer-provided adoption benefits, foreign earned income or foreign housing, and income earned in Puerto Rico or American Samoa by bona fide residents), plus 50% of Social Security benefits.

The first-tier thresholds, below which no Social Security benefits are taxable, are $25,000 of provisional income for taxpayers filing as single, head of household, or qualifying widow(er) and $32,000 of provisional income for taxpayers filing a joint return. In the case of taxpayers who are married filing separately, the threshold is also $25,000 of provisional income if the spouses lived apart all year, but it is $0 for those who lived together at any point during the tax year.7

If provisional income is between the first-tier thresholds and the second-tier thresholds of $34,000 (for single filers) or $44,000 (for married couples filing jointly), the amount of Social Security benefits subject to tax is the lesser of (1) 50% of Social Security benefits or (2) 50% of provisional income in excess of the first threshold.

If provisional income is above the second-tier thresholds, the amount of Social Security benefits subject to tax is the lesser of (1) 85% of benefits or (2) 85% of provisional income above the second threshold, plus the smaller of (a) $4,500 (for single filers) or $6,000 (for married filers)8 or (b) 50% of benefits.

Because the threshold for married taxpayers filing separately who have lived together any time during the tax year is $0, the taxable benefits in such a case are the lesser of 85% of Social Security benefits or 85% of provisional income. None of the thresholds are indexed for inflation or wage growth. Table 1 summarizes the thresholds and calculation of taxable benefits.

|

Provisional Incomea |

Taxable Social Security and |

|

|

Single Taxpayer |

||

|

(A) |

Less than $25,000 |

None |

|

(B) |

$25,000 to $34,000 |

Lesser of (1) 50% of benefits or (2) 50% of provisional income above $25,000 (maximum of $4,500) |

|

(C) |

Greater than $34,000 |

Lesser of (1) 85% of benefits or (2) 85% of provisional income above $34,000 plus amount from line (B) |

|

Married Taxpayer |

||

|

(D) |

Less than $32,000 |

None |

|

(E) |

$32,000 to $44,000 |

Lesser of (1) 50% of benefits or (2) 50% of provisional income above $32,000 (maximum of $6,000) |

|

(F) |

Greater than $44,000 |

Lesser of (1) 85% of benefits or (2) 85% of provisional income above $44,000 plus amount in line (E) |

The two examples in Table 2 illustrate how taxable Social Security benefits may be calculated for single (nonmarried) retirees in tax year 2018. In the examples, John and Mary are at least 62 years of age and receive $17,500 in annual Social Security benefits—about the average for a retired worker in 2018.9 John has non-Social Security income of $20,000, whereas Mary has non-Social Security income of $30,000. John's provisional income is between the first-tier and second-tier thresholds, resulting in taxable Social Security benefits of $1,875. Because Mary's provisional income is higher than John's and exceeds the second-tier threshold, a larger amount of her Social Security benefits ($8,537.50) is subject to income taxation. Because of the differences in non-Social Security income, 10.7% of John's Social Security benefits are subject to income taxation, compared with 48.8% of Mary's. The amount of income tax John and Mary owe on their taxable Social Security benefits is determined separately through the federal income tax system based on their other taxable income and their marginal tax rates.

Table 2. Calculation of Taxable Social Security Benefits for Single Social Security Recipients with a $17,500 Benefit and Different Levels of Other Income: An Example

|

Step 1: Calculate Provisional Income |

John |

Mary |

|

Other income |

$20,000 |

$30,000 |

|

+ 50% of Social Security (assume annual Social Security benefits are $17,500) |

$8,750 |

$8,750 |

|

= Provisional income |

$28,750 |

$38,750 |

|

Step 2: Compare Provisional Income to First-Tier Threshold |

||

|

First-tier threshold |

$25,000 |

$25,000 |

|

Excess over first-tier threshold

|

$3,750 |

$9,000 |

|

First tier taxable benefits equals

|

$1,875 |

$4,500a |

|

Step 3: Compare Provisional Income To Second-Tier Threshold |

||

|

Second-tier threshold |

$34,000 |

$34,000 |

|

Calculate excess over second tier

|

$0 |

$4,750 |

|

Second tier taxable benefits 85% of excess |

$0 |

$4,037.50 |

|

Step 4: Calculate Total Taxable Social Security Benefits |

||

|

For John: Provisional income is less than $34,000, so total taxable benefits equal first tier taxable benefits. For Mary: Provisional income is greater than $34,000, so total taxable benefits equal the lesser of

|

$1,875 |

$8,537.50 |

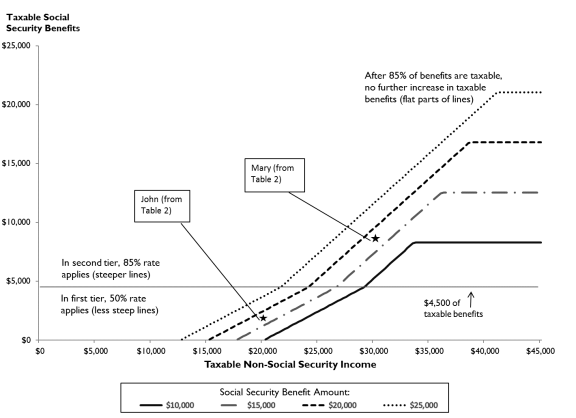

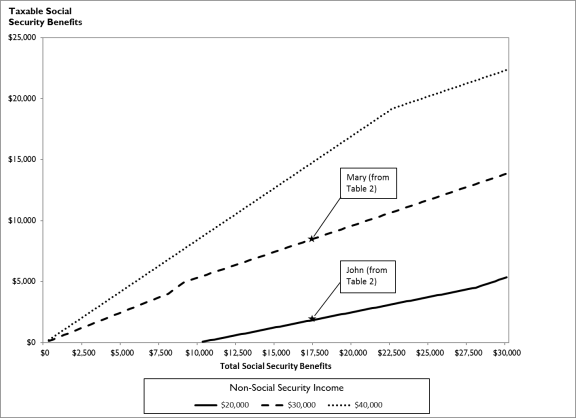

The calculation of taxable Social Security benefits depends on the level of benefits and the level of non-Social Security income.

- Holding benefits constant, as non-Social Security income increases, provisional income increases, and therefore the amount of taxable Social Security benefits increases.

- Holding non-Social Security income constant, as Social Security benefits increase, the taxable amount of Social Security benefits increases.

Those two perspectives are illustrated in the two figures below. (The figures are for single retirees only, but they would be similar for married couples.)

Figure 1 shows taxable Social Security benefits for single retirees with four different amounts of annual Social Security benefits ($10,000, $15,000, $20,000, and $25,000) as non-Social Security income increases from zero to $45,000. (Provisional income, which equals non-Social Security income plus half of Social Security benefits, is not shown directly in the figure.) Once provisional income exceeds the first-tier threshold of $25,000, each additional dollar of non-Social Security income results in 50 cents of additional taxable income. For example, for someone with Social Security benefits of $10,000, no benefits are taxable unless non-Social Security income exceeds $20,000, in which case provisional income would exceed $25,000 (which equals $20,000 plus half of $10,000).

Once provisional income exceeds the second-tier threshold, each additional dollar of non-Social Security income results in an additional 85 cents of taxable income. As described above, the second-tier threshold occurs when provisional income exceeds $34,000, at which point taxable Social Security benefits exceed $4,500. In the figure, a horizontal line marks $4,500 of taxable Social Security benefits.

The taxable amount of Social Security benefits continues to increase as non-Social Security income increases until 85% of Social Security benefits are taxable. After that, the amount of taxable benefits is constant, as shown by the flat portions of the lines on the right-hand side of the figure.

Stars in the figure identify Table 2's example retirees, John and Mary. Both have the same amount of Social Security benefits ($17,500); however, Mary has greater taxable Social Security benefits than John because her non-Social Security income is larger ($30,000 for Mary, $20,000 for John). Mary is in the second tier of the calculation of taxable Social Security benefits, whereas John is in the first tier.

Note that the additional tax owed is less than the additional taxable income. The additional tax owed equals the additional taxable income multiplied by the taxpayer's marginal tax rate. That is, the additional taxable income is the additional amount subject to federal income taxation, not the additional amount paid in taxes.

Figure 2 shows taxable Social Security benefits for single retirees with three different levels of non-Social Security income ($20,000, $30,000, and $40,000) as Social Security benefits increase. (Provisional income, which equals non-Social Security income plus half of Social Security benefits, is not shown directly in the figure.) For people with $10,000 of Social Security benefits, those benefits would be untaxed unless non-Social Security income exceeded $20,000, at which point provisional income would exceed the $25,000 threshold (which equals half of $10,000 plus $20,000).

Stars in the figure identify Table 2's example retirees, John and Mary. Although they have the same amount of Social Security benefits ($17,500), they are on different lines in the figure, representing the differences in their non-Social Security income. If John or Mary were to experience an increase or decrease in their Social Security benefits, holding non-Social Security income constant, their new amount of taxable Social Security benefits would be found by moving to the right or left, respectively, along their same non-Social Security income lines in the figure.

As noted above, the additional tax owed is less than the additional taxable income, because the additional tax owed equals the additional taxable income multiplied by the taxpayer's marginal tax rate.

For the same levels of non-Social Security income and Social Security benefits, a married couple will have lower taxable Social Security benefits than a single retiree. Consequently, Figure 1 and Figure 2 do not reflect the impact of taxation on a married couple filing a joint tax return.

Special Considerations

The application of the benefit taxation formula may vary within special considerations. These include lump-sum distributions, repayments, workers' compensation coordination, nonresident aliens' treatment, and wage withholdings. Each consideration is discussed in more detail in the Appendix to this report.

State Taxation

Although the Railroad Retirement Act prohibits states from taxing railroad retirement benefits, including any federally taxable Tier I benefits (45 U.S.C. §231m), states may tax Social Security benefits. In general, state personal income taxes follow federal taxes. That is, many states use federal adjusted gross income, federal taxable income, or federal taxes paid as a beginning point for state income tax calculations. All of these beginning points include the federally taxed portion of Social Security benefits. States with these beginning points for state taxation must then make an adjustment, or subtraction from income (or taxes), for railroad retirement benefits. A state may also make an adjustment for all or part of the federally taxed Social Security benefits. Some states do not begin state income tax calculation with these federal tax values, but instead begin with a calculation based on income by source. The state may then include part or all of Social Security benefits in the state income calculation. 10

As shown in Table 3, as of tax year 2017, 29 states and the District of Columbia fully exclude Social Security benefits from the state personal income tax. Nine states tax all or part of Social Security benefits but differ from the federal government, and five states follow the federal government in their tax treatment of Social Security benefits. The remaining seven states have no personal income tax.

|

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia exempt Social Security benefits from income taxation |

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Wisconsin |

|

Nine states tax all or part of Social Security benefits but not the same as federal taxation |

Colorado, Connecticut, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Rhode Island |

|

Five states follow federal taxation of Social Security benefits |

New Mexico, North Dakota, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia |

|

Seven states do not have an income tax |

Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, Wyoming |

Source: Rick Olin, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, Individual Income Tax Provisions in the States, Informational Paper 4, January 2019, available at http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lfb/informational_papers/january_2019/0004_individual_income_tax_provisions_in_the_states_informational_paper_4.pdf.

Growth in Social Security Benefits Subject to Taxation

Historical data from 1999 through 2016 show that the number and percentage of beneficiaries subject to taxation of Social Security benefits is growing over time because the provisional income thresholds used to determine the taxable share of benefits are not indexed for inflation or wage growth. Table 4 shows that the percentage of all tax returns with taxable Social Security benefits has grown from 7.4% in 1999 to 13.3% in 2016. In the aggregate, Table 4 shows that the amount of taxable Social Security benefits as a percentage of all Social Security benefit payments has grown from 19.5% in 1999 to 31.4% in 2016.

|

Year |

Percentage of All Tax Returns with Taxable Social Security Benefits |

Taxable Social Security Benefits as a Percentage of All Social Security Benefits |

|

1999 |

7.4 |

19.5 |

|

2000 |

8.2 |

22.1 |

|

2001 |

8.3 |

21.7 |

|

2002 |

8.2 |

20.6 |

|

2003 |

8.4 |

20.8 |

|

2004 |

8.8 |

22.4 |

|

2005 |

9.4 |

24.0 |

|

2006 |

9.9 |

26.4 |

|

2007 |

10.5 |

28.6 |

|

2008 |

10.5 |

27.3 |

|

2009 |

10.9 |

25.9 |

|

2010 |

11.3 |

27.2 |

|

2011 |

11.5 |

27.8 |

|

2012 |

12.3 |

28.9 |

|

2013 |

12.6 |

30.0 |

|

2014 |

12.8 |

30.8 |

|

2015 |

13.1 |

31.3 |

|

2016 |

13.3 |

31.4 |

Source: CRS calculations from Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Bulletin Historical Table 1, at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-historical-table-1, and Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary, Trust Fund Tables, OASI and DI Trust Funds, Combined, 1957 and later, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4a3.html.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that 49% of Social Security beneficiaries (25.5 million people) were affected by the income taxation of Social Security benefits in tax year 2014.11 That share has almost doubled since 1998, when 26% of beneficiaries were affected by taxation of benefits.12 A 2015 Social Security Administration (SSA) analysis projected that the share will continue to rise, with more than 56% of Social Security beneficiary families owing income tax on their Social Security benefits in 2050.13

Federal Income Taxes Owed on Social Security Benefits by Income Level

Federal income tax liability on Social Security benefits increases with income. 14 Figure 3 shows that the overall projected share of Social Security benefits that will be paid as federal income taxes is projected to be 6.6% in 2020. Among Social Security beneficiaries in taxpayer units with economic income less than $50,000, the share is projected to be either zero or nearly zero. 15 The share is projected to increase for economic income categories above $50,000 and is projected to reach 12.8% among Social Security beneficiaries in taxpayer units with economic income between $100,000 and $200,000 in 2020, going up to 31.9% among Social Security beneficiaries in taxpayer units with economic income over $1,000,000 in 2020.

The SSA's 2015 analysis projected that, among all Social Security beneficiary families, the mean percentage of Social Security benefits owed as taxes will be 10.9% in 2050, ranging from 1.1% among beneficiary families in the lowest quartile of the income distribution to 16.1% for beneficiaries in the top quartile.16

|

Figure 3. Federal Income Tax Liability on Social Security Benefits as a Percentage of Social Security Benefits, by Taxpayer Unit Income Category Projected for 2020 |

|

|

Source: CRS calculations from Joint Committee on Taxation, Background on Revenue Sources for the Social Security Trust Funds, JCX-41-19, Tables 9 and 10, July 24, 2019, at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5216. Notes: Taxpayer units include nonfilers, but exclude dependent filers and returns with negative income. The income concept used to place tax returns into income categories is adjusted gross income plus (1) tax-exempt interest, (2) employer contributions for health plans and life insurance, (3) employer share of payroll taxes, (4) worker's compensation, (5) nontaxable Social Security benefits, (6) the value of Medicare benefits in excess of premiums paid, (7) alternative minimum tax preference items, (8) individual share of business taxes, and (9) excluded income of U.S. citizens living abroad. Categories are measured at 2020 levels. |

Corresponding to the share of Social Security benefits payable as federal income tax in Figure 3, Figure 4 shows the projected average federal income tax liability on Social Security benefits among Social Security taxpayer units, by taxpayer unit economic income category in 2020.17 Average federal income tax liability in 2020 for Social Security taxpayer units with economic income less than $50,000 is projected to be either zero or nearly zero. Average federal income tax liability in 2020 is projected to rise steadily with economic income above $50,000, reaching approximately $3,700 for Social Security taxpayer units with economic income between $100,000 and $200,000 and just over $12,000 for Social Security taxpayer units with economic income above $1,000,000. Average federal income tax liability on Social Security benefits across all Social Security taxpayer units is projected to be about $3,200 in 2020.

|

Figure 4. Average Federal Income Tax Liability on Social Security Benefits Among Social Security Taxpayer Units, by Taxpayer Unit Income Category Projected for 2020 |

|

|

Source: CRS and Joint Committee on Taxation, Background on Revenue Sources for the Social Security Trust Funds, JCX-41-19, Table 9, July 24, 2019, at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5216. Notes: Social Security taxpayer units are those federal income taxpayer units that owe federal income taxes on their Social Security benefits. Taxpayer units include nonfilers, but exclude dependent filers and returns with negative income. The income concept used to place tax returns into income categories is adjusted gross income plus (1) tax-exempt interest, (2) employer contributions for health plans and life insurance, (3) employer share of payroll taxes, (4) worker's compensation, (5) nontaxable Social Security benefits, (6) the value of Medicare benefits in excess of premiums paid, (7) alternative minimum tax preference items, (8) individual share of business taxes, and (9) excluded income of U.S. citizens living abroad. Categories are measured at 2020 levels. |

Impact on the Trust Funds

The proceeds from taxing up to 50% of Social Security and Railroad Retirement Tier I benefits for beneficiaries with provisional income between the first-tier and second-tier thresholds are credited to Social Security's two trust funds—the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Disability Insurance (DI) trust funds—and to the Railroad Retirement system, on the basis of the source of the benefits taxed. Proceeds from taxing up to 85% of benefits for beneficiaries with provisional income above the second-tier thresholds are credited to Medicare's HI trust fund.

In 2018, the OASI and DI (collectively referred to as OASDI) trust funds were credited with $35.0 billion from taxation of benefits, or 3.5% of the funds' total income.18 Income from the taxation of benefits in the HI trust fund in 2018 was $24.2 billion, or 7.9% of total HI fund income.19 In 2017, the Railroad Retirement system was credited with $292 million in revenue from taxation of Railroad Retirement Tier I benefits, representing about 2.3% of its total income.20

As noted above, because the income thresholds used to determine the taxable share of benefits are not indexed for inflation or wage growth, income taxes on benefits will become an increasingly important source of tax revenues for Social Security and Medicare. In 2016, about 31% of the total Social Security benefits were subject to income tax (Table 4). CBO estimated that proportion will increase to more than 50% by 2046.21 The income taxes collected from Social Security benefits are projected to grow from 0.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 to 0.3% of GDP in 2028 and 0.4% of GDP in 2078.22

Under the intermediate assumptions, the Social Security and Medicare Trustees project that over the next 10 years, income taxes will grow from 3.5% of Social Security's income to 5.7%. In addition, the share will continue to grow, to 7.4% by 2095.23 For Medicare, income tax on benefits as a share of total revenue increases from 7.9% to 12.4% in 2028.24

History of Taxing Social Security Benefits

Until 1984, Social Security benefits were exempt from the federal income tax. The exclusion was based on rulings made in 1938 and 1941 by the Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Internal Revenue (the predecessor of the Internal Revenue Service). The 1941 bureau ruling on Social Security payments viewed benefits as being for general welfare and reasoned that subjecting the payments to income taxation would be contrary to the purposes of Social Security.25

Under these rules, the treatment of Social Security benefits was similar to that of certain types of government transfer payments (such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Supplemental Security Income, and benefits under the Black Lung Benefits Act). This was in sharp contrast to then-current rules for retirement benefits under private pension plans, the federal Civil Service Retirement System, and other government pension systems.26 Benefits from those pension plans were fully taxable, except for the portion of total lifetime benefits (using projected life expectancy) attributable to the employee's own contributions to the system (and on which he or she had already paid income tax).

Currently (and as in 1941), under Social Security, the worker's contribution to the system is half of the payroll tax, officially known as the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) tax. The amount the worker pays into the Social Security system in FICA taxes is not subtracted to determine income subject to the federal income tax, and is therefore taxed. The employer's contributions to the system are not considered part of the employee's gross income, and they are deductible from the employer's business income as a business expense.27 Consequently, neither the employee nor the employer pays taxes on the employer's contribution.28

The 1979 Advisory Council on Social Security concluded that because Social Security benefits are based on earnings in covered employment, the 1941 ruling was wrong and the tax treatment of private pensions was a more appropriate model for treating Social Security benefits.29 The council estimated that the most anyone who entered the workforce in 1979 would pay in payroll taxes during his or her lifetime would equal 17% of the Social Security benefits he or she would ultimately receive. (This was the most any individual would pay; in the aggregate, workers would make payroll tax payments amounting to substantially less than 17% of their ultimate benefits.) Because of the administrative difficulties involved in determining the taxable amount of each individual benefit and to avoid "taxing more of the benefit than most people would consider appropriate," the council recommended instead that half of everyone's benefit be taxed. It justified this ratio as a matter of "rough justice" and noted that it coincided with the portion of the tax (the employer's share) on which income taxes had not been paid.30

The council's position on taxing Social Security benefits contrasted with that of the National Commission on Social Security, established by Congress in the Social Security Amendments of 1977 (P.L. 95-216). The commission did not, in its 1981 final report, include a recommendation to tax Social Security benefits. Also in 1981, the Senate passed a resolution by a roll-call vote of 98-0 against enacting legislation to tax Social Security benefits, stating that taxing Social Security benefits would be tantamount to a benefit cut and noting that the prospect of taxing benefits could undermine older Americans' confidence in the Social Security program:

Resolved, That it is the sense of the Senate that any proposals to make social security benefits subject to taxation would adversely affect social security recipients and undermine their confidence in the social security programs, that social security benefits are and should remain exempt from Federal taxation, and that the Ninety-seventh Congress will not enact legislation to subject social security benefits to taxation.31

The National Commission on Social Security Reform (often referred to as the "Greenspan Commission"), appointed by President Reagan in 1981, recommended in its 1983 report that, beginning in 1984, 50% of Social Security cash benefits and Railroad Retirement Tier I benefits be taxable for individuals whose adjusted gross income, excluding Social Security benefits, exceeded $20,000 for a single taxpayer and $25,000 for a married couple, with the proceeds of such taxation credited to the Social Security trust funds.32 The commission did not include any provisions for indexing the thresholds. The commission estimated that 10% of Social Security beneficiaries would be subject to taxation of benefits. The commission acknowledged that the proposal had a "notch" problem, in that people with income at the thresholds would pay significantly higher taxes than those with only one dollar less, but trusted that it would be rectified during the legislative process.

In enacting the 1983 Social Security Amendments (P.L. 98-21), Congress adopted the commission's recommendation to tax Social Security benefits, but with a formula that gradually increased the taxable share as a person's income rose above the thresholds, up to a maximum of 50% of benefits. The formula calculated taxable benefits as the lesser of 50% of benefits or 50% of the excess of the taxpayer's provisional income over thresholds of $25,000 (for single filers) and $32,000 (for married filers). Provisional income equaled adjusted gross income plus tax-exempt interest plus certain income exclusions plus 50% of Social Security benefits.

The House Ways & Means Committee reported the following:

Your Committee believes that social security benefits are in the nature of benefits received under other retirement systems, which are subject to taxation to the extent they exceed a worker's after-tax contributions and that taxing a portion of social security benefits will improve tax equity by treating more nearly equally all forms of retirement and other income that are designed to replace lost wages (for example, unemployment compensation and sick pay).33,34

The Senate Finance Committee reported the following:

... by taxing social security benefits and appropriating these revenues to the appropriate trust funds, the financial solvency of the social security trust funds will be strengthened.... By taxing only a portion of social security and railroad retirement benefits (that is, up to one-half of benefits in excess of a certain base amount), the Committee's bill assures that lower-income individuals, many of whom rely upon their benefits to afford basic necessities, will not be taxed on their benefits. The maximum proportion of benefits taxed is one-half in recognition of the fact that social security benefits are partially financed by after-tax employee contributions. The bill's method for taxing benefits assures that only those taxpayers who have substantial taxable income from other sources will be taxed on a portion of the benefits they receive.35

In 1993, the SSA's Office of the Actuary estimated that, if pension tax rules were applied to Social Security, the ratio of total employee Social Security payroll taxes to expected benefits for current recipients (in 1993) would be approximately 4% or 5%. For workers just entering the workforce, the actuaries estimated that the ratio would be, on average, about 7%.36 Because Social Security benefits replaced a higher proportion of earnings for workers who were lower paid and had dependents, and because women had longer life expectancies, the workers with the highest ratio of taxes to benefits would be single, highly paid males. The estimated ratio for these workers (highly paid males) entering the workforce in 1993 was 15%.37

Applying the tax rules for private and public pensions presents practical administrative problems. Determining the proper exclusion would be complex for several reasons, including the difficulty of calculating the ratio of contributions to benefits for each individual when several people may receive benefits on the basis of the same worker's account.38

President William Clinton proposed (as part of his FY1994 budget proposal) that the portion of Social Security benefits subject to taxation be increased from 50% to 85%, effective in tax year 1994. As under then-current law, only Social Security recipients whose provisional income exceeded the thresholds of $25,000 (for single filers) and $32,000 (for married filers) were to pay taxes on their benefits. In addition, the first step was to add 50%, not 85%, of benefits to adjusted gross income. Because the thresholds and definition of provisional income did not change, the measure would only affect recipients already paying taxes on benefits. However, the ratio used to compute the amount of taxable benefits was increased from 50% to 85%. Taxing no more than 85% of Social Security benefits (the estimated portion not based on contributions by a recipient, including highly paid males) would ensure that no one would have a higher percentage of Social Security benefits subject to tax than if the tax treatment of private and civil service pensions were actually applied.

The proceeds from the increase (from 50% to 85%) were slated to be credited to the Medicare HI program, which had a less favorable financial outlook than Social Security. Doing so also avoided possible procedural obstacles (budget points of order that can be raised regarding changes to the Social Security program in the budget reconciliation process). This measure was included in the OBRA 1993, which passed the House on May 27, 1993.

The Senate version of the bill included a provision to tax Social Security benefits up to 85% but imposed it only after provisional income exceeded new thresholds of $32,000 (for single filers) and $40,000 (for married filers). The conference agreement adopted the Senate version of the taxation of Social Security benefits provision and raised the thresholds to $34,000 (for single filers) and $44,000 (for married filers).

President Clinton signed the measure into law (as part of P.L. 103-66) on August 10, 1993. Although other changes in tax law have since affected the amount of taxes paid on Social Security benefits, there have been no direct legislative changes regarding taxation of Social Security benefits since 1993.

Current Proposals Addressing the Taxation of Social Security Benefits

In the 116th Congress, four bills that would alter the taxation of Social Security benefits have been introduced. Each is described briefly below.

H.R. 567, the Save Social Security Act of 2019, was introduced in the House on January 15, 2019, by Representative Crist. In addition to applying the Social Security payroll tax to annual earnings above $300,000 and providing benefit credits for annual earnings above the current-law taxable maximum amount, H.R. 567 would replace the current-law provisional income thresholds for federal income taxation of Social Security benefits with a higher threshold and tax up to 85% of Social Security benefits for individuals and couples with provisional income above that threshold. The separate provisional income thresholds under current law for single individuals and married couples filing jointly would be replaced with one provisional income threshold. The separate thresholds under current law for taxation of up to 50% of Social Security benefits and up to 85% of Social Security benefits also would be replaced with a single threshold. H.R. 567 would tax up to 85% of Social Security benefits for tax filers with provisional income greater than $100,000. The new provisional income threshold would not be indexed to changes in prices or average wages. If enacted, H.R. 567 would result in less income tax revenue to the Social Security trust funds, the Medicare HI trust fund, and the Railroad Retirement system. General revenues would be appropriated in amounts required to make up the lost revenue to each fund.

H.R. 860, the Social Security 2100 Act, was introduced in the House on January 30, 2019, by Representative Larson. An identical bill, S. 269, was introduced in the Senate on the same date by Senator Blumenthal. The bills would increase the Social Security payroll tax rate, expand the share of aggregate covered earnings subject to the Social Security payroll tax, increase benefits for all beneficiaries, change the index used to calculate annual cost-of-living adjustments, and change the federal income taxation of Social Security benefits. Specifically, the bills would replace the separate provisional income thresholds under current law for taxation of up to 50% of Social Security benefits and up to 85% of Social Security benefits with new, higher thresholds for taxation of up to 85% of Social Security benefits, set at $50,000 for single filers and $100,000 for married couples filing jointly. As a result, the bills would reduce the number of beneficiaries who pay federal income taxes on their Social Security benefits. They would require that the Medicare HI trust fund be held harmless in light of the lost income tax revenue.39

H.R. 3971, the Senior Citizens Tax Elimination Act, was introduced in the House on July 25, 2019, by Representative Massie. It would eliminate the federal income taxation of Social Security benefits and Railroad Retirement Tier I benefits. Under H.R. 3971, Section 86 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, which provides for the federal income taxation of Social Security benefits and Railroad Retirement Tier I benefits, would not apply to any taxable year beginning after the date of enactment of H.R. 3971. General funds would be appropriated in amounts needed to hold the Social Security trust funds and the Medicare HI trust fund harmless from the loss of income tax revenues. General funds also would be appropriated to the Railroad Retirement system in amounts needed to compensate for the lost income tax revenues.

Appendix. Taxation of Benefits Under Special Situations

Lump-Sum Distributions

A Social Security beneficiary may receive a lump-sum distribution of benefits owed for one or more prior years.40 In this situation, a beneficiary may choose between two methods for calculating the taxable portion of the lump-sum distribution: (1) include all of the benefits for prior years in calculating the taxable benefits for the current year or (2) recalculate the prior-year taxable benefits using prior-year income and take the difference between the recalculated taxable benefits and the taxable benefits reported in each prior year. In either case, the additional taxable benefits are included in taxable income for the current year. In computing the taxable portion of benefits in prior years, some income sources generally excluded from the provisional income calculation are included.41

Repayments

Sometimes a Social Security beneficiary must repay a prior overpayment of benefits. In this case, the calculation of taxable Social Security benefits is based on the net benefits—gross benefits less the repayment—even if the repayment is for a benefit received in a previous year. For married taxpayers filing a joint return, net benefits equal the sum of the couple's Social Security gross benefits less the repayment.

If, however, the repayment results in negative net Social Security benefits, two consequences exist: (1) there are no taxable benefits and (2) the taxpayer may be able to deduct part of the negative net Social Security benefit if it was included in gross income in an earlier year.42

Coordination of Workers' Compensation

For individuals under the full retirement age who receive Social Security disabled worker benefits, Social Security benefits are reduced by a portion of any workers' compensation payments (or payments from some other public disability programs) received by the individual.43 Workers' compensation is generally not taxable. Any reduction in Social Security benefits due to the receipt of workers' compensation is still considered to be a Social Security benefit, however, so income taxes are computed based on the full (unreduced) benefit amount.44

Treatment of Nonresident Aliens

Citizenship is not required to receive Social Security benefits. Nonresident aliens, under IRS definitions, may receive benefits provided they have engaged in covered employment and otherwise meet eligibility requirements. The IRS defines a nonresident alien as a noncitizen who (1) is not a lawful permanent resident (this is known as the Green Card Test) and (2) has been physically present in the United States for fewer than 31 days in the previous calendar year and 183 days in the previous three-year period, counting all the days in the calendar year and a portion of the days in the two previous calendar years (this is known as the Substantial Presence Test).45 In general, 85% of the Social Security benefits for nonresident aliens are taxable (i.e., none of the thresholds apply) at a 30% rate. However, there are a number of exceptions to this general rule on the basis of tax treaties such that nonresident aliens or U.S. citizens living abroad may not have U.S. Social Security benefits subject to U.S. income taxes.46

Withholding

In general, withholding for a wage earner is based on the estimated income taxes for a full year of earnings at the periodic (weekly, biweekly, monthly, etc.) rate. Taxable Social Security benefits, and the associated taxes, are based on the amount of non-Social Security income earned by a recipient during the tax year. The Social Security Administration, without knowledge about the amount of other income received by a beneficiary, is unable to properly determine the amount of taxes that should be withheld from Social Security benefits. Like other taxpayers, Social Security recipients can make quarterly estimated income tax payments. In addition, effective for payments issued in February 1999, individuals may request voluntary tax withholding from Social Security benefits.47

Nonresident aliens residing outside the United States are subject to different tax withholding rules. Section 871 of the Internal Revenue Code imposes a 30% tax withholding rate on almost all of the U.S. income of nonresident aliens, unless a lower rate is fixed by treaty. Thus, 30% of 85% (or 25.5%) of a nonresident alien's Social Security benefits may be withheld for federal income taxes.