Prescription drugs play a vital role in American public health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that between 2011 and 2014 just under half of all Americans had used one or more prescription drugs in the last 30 days.1 On the other hand, unfettered access to drugs may pose serious public health risks. The CDC reports that in 2017 over 70,000 Americans died of overdoses on prescription and nonprescription drugs.2 The Controlled Substances Act3 (CSA or the Act) seeks to balance those competing interests.4 The CSA regulates controlled substances—prescription and nonprescription drugs and other substances that are deemed to pose a risk of abuse and dependence.5 By establishing rules for the proper handling of controlled substances6 and imposing penalties for any illicit production, distribution, and possession of such substances,7 the Act seeks to protect the public health from the dangers of controlled substances while also ensuring that patients have access to pharmaceutical controlled substances for legitimate medical purposes.8

This report provides an overview of the CSA and select legal issues that have arisen under the Act, with a focus on legal issues of concern for the 116th Congress. The report first summarizes the history of the CSA and explains how the regulation of drugs under the CSA overlaps with other federal and state regulatory regimes.9 It then outlines the categories—known as schedules—into which controlled substances subject to the Act are divided and discusses how substances are added to the schedules.10 The report next summarizes the CSA's registration requirements, which apply to entities that register with the government to legally handle pharmaceutical controlled substances,11 before summarizing the CSA's criminal trafficking provisions, which apply to activities involving controlled substances that are not sanctioned under the Act.12 Finally, the report outlines select legal issues for Congress related to the CSA, including issues related to the response to the opioid crisis, the control of analogues to the potent opioid fentanyl, the growing divergence between the treatment of marijuana under federal and state law, and the legal limits on clinical research involving certain controlled substances.13

Background and Scope of the CSA

Congress has regulated drugs in some capacity since the 19th century. Federal drug regulation began with tariffs, import and export controls, and purity and labeling requirements applicable to narcotic drugs including opium and coca leaves and their derivatives.14 With the passage of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, Congress began in earnest to regulate the domestic trade in narcotic drugs.15 The Harrison Act provided for federal oversight of the legal trade in narcotic drugs and imposed criminal penalties for illicit trafficking in narcotics.16 Over the course of the 20th century, the list of drugs subject to federal control expanded beyond narcotic drugs to include marijuana, depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens.17

Congress revamped federal drug regulation by enacting the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970.18 The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act repealed nearly all existing federal substance control laws and, for the first time, imposed a unified framework of federal controlled substance regulation.19 Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act is known as the Controlled Substances Act.20

The CSA regulates certain drugs21—whether medical or recreational, legally or illicitly distributed—that are considered to pose a risk of abuse and dependence.22 In enacting the CSA, Congress recognized two competing interests related to drug regulation: on the one hand, many drugs "have a useful and legitimate medical purpose and are necessary to maintain the health and general welfare of the American people."23 On the other hand, "illegal importation, manufacture, distribution, and possession and improper use of controlled substances have a substantial and detrimental effect on the health and general welfare of the American people."24 Accordingly, the Act simultaneously aims to protect public health from the dangers of controlled substances while also ensuring that patients have access to pharmaceutical controlled substances for legitimate medical purposes.

To accomplish those two goals, the statute creates two overlapping legal schemes. Registration provisions require entities working with controlled substances to register with the government, take steps to prevent diversion and misuse of controlled substances, and report certain information to regulators.25 Trafficking provisions establish penalties for the production, distribution, and possession of controlled substances outside the legitimate scope of the registration system.26

The CSA does not apply to all drugs. As discussed below, substances must be specifically identified for control (either individually or as a class) to fall within the scope of the Act.27 For medical drugs, the CSA primarily applies to prescription drugs, not drugs available over the counter.28 Moreover, the statute does not apply to all prescription drugs, but rather to a subset of those drugs deemed to warrant additional controls.29 As for nonpharmaceutical drugs, well-known recreational drugs such as marijuana, cocaine,30 heroin, and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) are all controlled substances, as are numerous lesser-known substances, some of which are identified only by their chemical formulas.31 Some recreational drugs are not classified as federally controlled substances.32 Alcohol and tobacco, which might otherwise qualify as drugs potentially warranting control under the CSA, are explicitly excluded from the scope of the Act,33 as is hemp that meets certain statutory requirements.34 Finally, it is possible for legitimate researchers and illicit drug manufacturers to formulate new drugs not contemplated by the Act. Those drugs may fall outside the scope of the CSA unless they are classified as controlled substances.35

Other Regulatory Schemes

Many drugs classified as controlled substances subject to the CSA are also subject to other legal regimes. For example, all prescription drugs, including those subject to the Act, are subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act).36 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the agency primarily responsible for enforcing the FD&C Act, which prohibits the "introduction or delivery for introduction into interstate commerce of any . . . drug . . . that is adulterated or misbranded."37 The FD&C Act defines misbranding broadly: a drug is considered misbranded if, among other things, its labeling, advertising, or promotion "is false or misleading in any particular."38 Unlabeled drugs are considered misbranded,39 as are prescription drugs that FDA has not approved, including imported drugs.40 In addition, misbranding may include misrepresenting that a substance offered for sale is a brand-name drug (even if the seller believes the substance for sale is chemically identical to the brand-name drug).41 The FD&C Act provides that a drug is deemed to be adulterated if, among other things, it "consists in whole or in part of any filthy, putrid, or decomposed substance," "it has been prepared, packed, or held under insanitary conditions," its container is made of "any poisonous or deleterious substance," or its strength, quality, or purity is not as represented.42

The key aims of the FD&C Act are related to but distinct from those of the CSA. The CSA establishes distribution controls to prevent the misuse of substances deemed to pose a potential danger to the public welfare.43 The FD&C Act, by contrast, is a consumer protection statute that seeks to prevent harm to consumers who obtain drugs (and other public health products) through commercial channels.44 Any person or organization that produces, distributes, or otherwise works with prescription drugs that are also controlled substances must comply with the requirements of both the CSA and the FD&C Act.

With respect to both pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical drugs, many drugs subject to the Act are also subject to state drug laws.45 State substance control laws often mirror federal law and are relatively uniform across jurisdictions because almost all states have adopted a version of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act (UCSA).46 However, states are free to modify the UCSA, and have done so to varying extents.47 Moreover, the model statute does not specify sentences for violations, so penalties for state controlled substance offenses vary widely.48

There is not a complete overlap between drugs subject to federal and state control for several reasons. First, states may elect to impose controls on substances that are not subject to the CSA.49 For example, some states have controlled the fentanyl analogues benzylfentayl and thenylfentanyl, but those substances are not currently subject to federal control.50 Second, states may wish to adopt federal scheduling decisions at the state level but lag behind federal regulators due to the need for a separate state scheduling process.51 Third, states may decide not to impose state controls on substances subject to the CSA, or they may choose to impose modified versions of federal controls at the state level.52 Crucially, however, the states cannot alter federal law, and when state and federal law conflict, the federal law controls.53 Thus, when states "legalize" or "decriminalize" a federally controlled substance (as many have done recently with respect to marijuana), the sole result is that the substance is no longer controlled under state law.54 Any federal controls remain in effect and potentially enforceable in those states.55

Classification of Controlled Substances

The heart of the CSA is its system for classifying controlled substances, as nearly all the obligations and penalties that the Act establishes flow from the classification system.56 Drugs become subject to the CSA by being placed in one of five lists, referred to as "schedules."57 Both the Administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)—an arm of the Department of Justice (DOJ)—and Congress can place a substance in a schedule, move a controlled substance to a different schedule, or remove a controlled substance from a schedule.58 As discussed below, scheduling decisions by Congress and DEA follow different procedures.59

Overview of Schedules

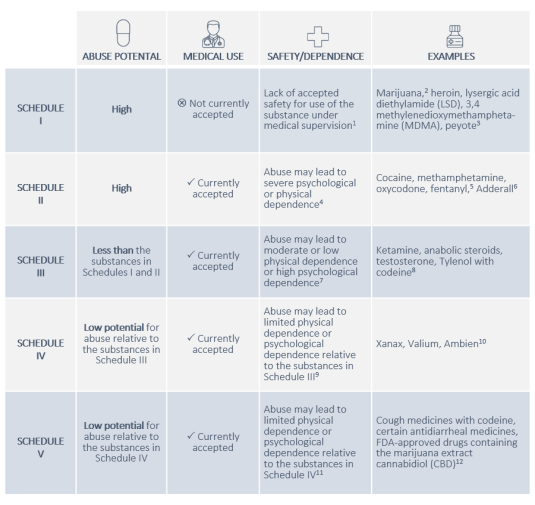

The CSA establishes five categories of controlled substances, referred to as Schedules I through V.60 The schedule on which a controlled substance is placed determines the level of restriction on its production, distribution, and possession, as well as the penalties applicable to any improper handling of the substance.61 As Figure 1 describes, each controlled substance is assigned to a schedule based on its medical utility and its potential for abuse and dependence.

|

|

Notes: 1 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(1). 2 The CSA generally uses the word "marihuana" to refer to the cannabis plant and its derivatives. This report uses the more widely accepted spelling, "marijuana," unless quoting other sources. 3 For the full list of substances in Schedule I, see 21 C.F.R. § 1308.11. 4 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(2). 5 The CSA distinguishes between prescription fentanyl and illicit fentanyl. Prescription fentanyl and several related medications are in Schedule II. Numerous nonprescription fentanyl analogues are in Schedule I. 6 For the full list of substances in Schedule II, see 21 C.F.R. § 1308.12. 7 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(3). 8 For the full list of substances in Schedule III, see 21 C.F.R. § 1308.13. 9 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(4). 10 For the full list of substances in Schedule IV, see 21 C.F.R. § 1308.14 11 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(5). 12 For the full list of substances in Schedule V, see 21 C.F.R. § 1308.15. |

A lower schedule number corresponds to greater restrictions, so controlled substances in Schedule I are subject to the most stringent controls, while substances in Schedule V are subject to the least stringent.62 Notably, because substances in Schedule I have no accepted medical use, it is only legal to produce, dispense, and possess those substances in the context of federally approved scientific studies.63

Analogues and Listed Chemicals

In addition to the controlled substances listed in Schedules I through V, the CSA also regulates (1) controlled substance analogues and (2) listed chemicals.

Under the CSA, a controlled substance analogue is a substance that FDA has not approved and that is not specifically scheduled under the Act, but that has (1) a chemical structure substantially similar to that of a controlled substance in Schedule I or II, or (2) an actual or intended effect that is "substantially similar to or greater than the stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogenic effect on the central nervous system of a controlled substance in schedule I or II."64 A substance that meets those criteria and is intended for human consumption is treated as a controlled substance in Schedule I.65

Listed chemicals subject to the CSA are precursor chemicals for controlled substances. They may be placed on one of two lists:

- List I Chemicals—designated chemicals that, in addition to legitimate uses, are used in manufacturing a controlled substance in violation of the CSA and are important to the manufacture of a controlled substance.66

- List II Chemicals—designated chemicals that, in addition to legitimate uses, are used in manufacturing a controlled substance in violation of the CSA.67

List I chemicals include substances such as ephedrine, white phosphorous, and iodine, which are used to produce methamphetamine, as well as chemicals used to manufacture LSD, MDMA, and other drugs.68 List II chemicals include, among others, solvents such as acetone, hydrochloric acid, and sulfuric acid.69

Listed chemicals are subject to some of the same controls as controlled substances.70 In addition, entities that sell listed chemicals must record the transactions, report them to regulators, and comply with statutory limits on sales to a single purchaser.71

There are a number of differences between how controlled substance analogues and listed chemicals are regulated. A key difference between controlled substance analogues and listed chemicals is that a substance does not qualify for control as an analogue unless it is intended for human consumption as a substitute for a controlled substance, while listed chemicals generally are not intended for human consumption standing alone but are used as ingredients in the manufacture of controlled substances.72 In addition, listed chemicals include only specific substances identified for control under the CSA by statute or rulemaking.73 By contrast, controlled substance analogues need not be individually scheduled; they need only satisfy the statutory criteria.74

Scheduling Procedures

Substances may be added to or removed from a schedule or moved to a different schedule through agency action or by legislation.75

Legislative Scheduling

Perhaps the most straightforward way to change a substance's legal status under the CSA is for Congress to pass legislation to place a substance under control, alter its classification, or remove it from control. The procedural requirements for administrative scheduling discussed in the following section do not apply to legislative scheduling. Thus, Congress may use its legislative scheduling power to respond quickly to a drug it views as posing an urgent concern. For example, the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act of 2012 permanently added two synthetic cathinones (central nervous system stimulants) and certain cannabimimetic substances (commonly referred to as synthetic marijuana) to Schedule I.76

Administrative Scheduling

DEA makes scheduling decisions through a complex process requiring participation by other agencies and the public.77 DEA may undertake administrative scheduling on its own initiative, at the request of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), or "on the petition of any interested party."78 With regard to the last route for initiating administrative scheduling, the DEA Administrator may deny a petition to begin scheduling proceedings based on a finding that "the grounds upon which the petitioner relies are not sufficient to justify the initiation of proceedings."79 Denial of a petition to initiate scheduling proceedings is subject to judicial review, but courts will overturn a denial only if it is arbitrary and capricious.80

Before initiating rulemaking proceedings, DEA must request a scientific and medical evaluation of the substance at issue from the Secretary of HHS.81 The Secretary has delegated the authority to prepare the scientific and medical evaluation to FDA.82 In preparing the evaluation, FDA considers factors including the substance's potential for abuse and dependence, scientific evidence of its pharmacological effect, the state of current scientific knowledge regarding the substance, any risk the substance poses to the public health, and whether the substance is an immediate precursor of an existing controlled substance.83 Based on those factors, FDA makes a recommendation on whether the substance should be controlled and, if so, in which schedule it should be placed.84 FDA's scientific and medical findings are binding on DEA.85 And if FDA recommends against controlling the substance, DEA may not schedule it.86

Upon receipt of FDA's report, the DEA Administrator evaluates all of the relevant data and determines whether the substance should be scheduled, rescheduled, or removed from control.87 Before placing a substance on a schedule, the DEA Administrator must make specific findings that the substance meets the applicable criteria related to accepted medical use and potential for abuse and dependence.88 DEA scheduling decisions are subject to notice-and-comment rulemaking, meaning that interested parties must have the opportunity to submit comments on the DEA Administrator's decision before it becomes final.89

The DEA Administrator's decision whether to schedule, reschedule, or deschedule a substance through the ordinary administrative process is subject to judicial review.90 Such review is generally deferential: courts accept DEA's interpretation of the CSA as long as the interpretation of ambiguous statutory text is reasonable,91 and the CSA provides that the DEA Administrator's findings of fact are "conclusive" on judicial review if the findings are supported by substantial evidence.92

Emergency Scheduling

Ordinary DEA scheduling decisions are made through notice-and-comment rulemaking and can take years to consider and finalize.93 Recognizing that in some cases faster scheduling may be appropriate, Congress amended the CSA through the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 198494 to allow the DEA Administrator to place a substance in Schedule I temporarily when "necessary to avoid an imminent hazard to the public safety."95 Further amendments enacted in the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act of 2012 extended the maximum length of the temporary scheduling period.96 Before issuing a temporary scheduling order, the DEA Administrator must provide 30 days' notice to the public and the Secretary of HHS stating the basis for temporary scheduling.97 In issuing a temporary scheduling order, the DEA Administrator must consider only a subset of the factors relevant to permanent scheduling: the history and current pattern of abuse of the substance at issue; the scope, duration, and significance of abuse; and the risk to the public health.98 The DEA Administrator must also consider any comments from the Secretary of HHS.99

A substance may be temporarily scheduled for up to two years; if permanent scheduling proceedings are pending, the DEA Administrator may extend the temporary scheduling period for up to one additional year.100 A temporary scheduling order is vacated once permanent scheduling proceedings are completed with respect to the substance at issue.101 The CSA provides that emergency scheduling orders are not subject to judicial review.102

DEA has recently used its emergency scheduling power to temporarily control certain analogues to the opioid fentanyl103 and several synthetic cannabinoids.104

International Treaty Obligations

The United States is a party to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, which was designed to establish effective control over international and domestic traffic in narcotics, coca leaf, cocaine, and marijuana.105 That treaty requires signatories, among other things, to criminalize "cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction, preparation, possession, offering, offering for sale, distribution, purchase, sale, . . . importation and exportation of drugs" contrary to the Convention.106

The United States is also party to the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971, which was designed to establish similar control over stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens.107 The Convention on Psychotropic Substances requires parties to adopt various controls applicable to controlled substances, including mandating licenses for manufacture and distribution, requiring prescriptions for dispensing such substances, and adopting measures "for the repression of acts contrary to laws or regulations" adopted pursuant to treaty obligations.108

If existing controls of a drug are less stringent than those required by the United States' treaty obligations, the CSA directs the DEA Administrator to "issue an order controlling such drug under the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out such obligations."109 Scheduling pursuant to international treaty obligations does not require the factual findings that are necessary for other administrative scheduling actions, and may be implemented without regard to the procedures outlined for regular administrative scheduling.110

Registration Requirements

Once a substance is brought within the scope of the CSA, almost any person or organization that handles that substance, except for the end user, becomes subject to a comprehensive system of regulatory requirements.111 The goal of the regulatory scheme is to create a "closed system" of distribution in which only authorized handlers may distribute controlled substances.112 Central to the closed system of distribution is the requirement that individuals or entities that work with controlled substances register with DEA. Those covered entities, which include manufacturers, distributors, practitioners, and pharmacists,113 are referred to as registrants.114 As DEA has described the movement of a pharmaceutical controlled substance from the manufacturer to the patient,

[A] controlled substance, after being manufactured by a DEA-registered manufacturer, may be transferred to a DEA-registered distributor for subsequent distribution to a DEA-registered retail pharmacy. After a DEA-registered practitioner, such as a physician or a dentist, issues a prescription for a controlled substance to a patient . . . , that patient can fill that prescription at a retail pharmacy to obtain that controlled substance. In this system, the manufacturer, the distributor, the practitioner, and the retail pharmacy are all required to be DEA registrants, or to be exempted from the requirement of registration, to participate in the process.115

As discussed further below, registrants must maintain records of transactions involving controlled substances, establish security measures to prevent theft of such substances, and monitor for suspicious orders to prevent misuse and diversion.116 Thus, the registration system aims to ensure that any controlled substance is always accounted for and under the control of a DEA-registered person until it reaches a patient or is destroyed.117

Entities Required to Register

Under the CSA, every person who produces, distributes, or dispenses any controlled substance, or who proposes to engage in any of those activities, must register with DEA, unless an exemption applies.118 Significantly, the CSA exempts from registration individual consumers of controlled substances, such as patients and their family members, whom the act refers to as "ultimate users."119 DEA has explained that ultimate users need not register because the controlled substances in their possession "are no longer part of the closed system of distribution and are no longer subject to DEA's system of corresponding accountability."120

Manufacturers and distributors of controlled substances, such as pharmaceutical companies, must register with DEA annually.121 By contrast, entities that dispense controlled substances, such as hospitals, pharmacies, and individual medical practitioners and pharmacists, may obtain registrations lasting between one and three years.122 Registrations specify the extent to which registrants may manufacture, possess, distribute, or dispense controlled substances, and each registrant may engage only in the specific activities covered by its registration. In some instances, applicants must obtain more than one registration to comply with the CSA. For example, separate registrations are required for each principal place of business where controlled substances are manufactured, distributed, imported, exported, or dispensed.123 And certain activities can give rise to additional registration requirements. For instance, a special registration is required to operate an opioid treatment program such as a methadone clinic.124

The CSA directs the DEA Administrator to grant registration if it would be consistent with the public interest, outlining the criteria the DEA Administrator must consider when evaluating the public interest.125 The criteria vary depending on (1) whether the applicant is a manufacturer, distributor, researcher, or practitioner, and (2) the classification of the controlled substances that are the focus of the application. However, the requirements generally serve to help DEA determine whether the applicant has demonstrated the capacity to maintain effective controls against diversion and comply with applicable laws.126

The registration of an individual or organization expires at the end of the registration period unless it is renewed.127 Registration also ends when the registrant dies, ceases legal existence, or discontinues business or professional practice.128 A registration cannot be transferred to someone else without the express, written consent of the DEA Administrator.129

Obligations of Registrants

Recordkeeping and Reporting

The CSA and its implementing regulations impose multiple recordkeeping and reporting requirements on registrants. Registrants must undertake a biennial inventory of all stocks of controlled substances they have on hand, and maintain records of each controlled substance they manufacture, receive, sell, deliver, or otherwise dispose of.130 In addition, controlled substances in Schedules I and II may only be distributed pursuant to a written order.131 Copies of each order form must be transmitted to DEA.132 Records of orders must be preserved for two years and made available for government review upon request.133

Registrants are also required to "design and operate a system to identify suspicious orders" and to notify DEA of any suspicious orders they detect.134 DEA regulations provide that "[s]uspicious orders include orders of unusual size, orders deviating substantially from a normal pattern, and orders of unusual frequency."135 That list is not exhaustive, however—orders may also be deemed suspicious if, for example, a pharmacy mostly sells controlled substances rather than a more typical mix of controlled and noncontrolled medications, if many customers pay for controlled substances with cash, or if pharmacies purchase drugs at a price higher than insurance would reimburse.136

Inspections

The CSA permits the DEA Administrator to inspect the establishment of any registrant or applicant for registration.137 DEA regulations express the intent of the agency "to inspect all manufacturers of controlled substances listed in Schedules I and II and distributors of controlled substances listed in Schedule I once each year," and other manufacturers and distributors of controlled substances "as circumstances may require."138 Absent the consent of the registrant or special circumstances such as an imminent danger to health or safety, a warrant is required for inspection.139 "Any judge of the United States or of a State court of record, or any United States magistrate judge" may issue such a warrant "within his territorial jurisdiction."140 Issuance of a warrant requires probable cause.141 The CSA defines probable cause as "a valid public interest in the effective enforcement of this subchapter or regulations thereunder sufficient to justify" the inspection at issue.142

Security

The CSA's implementing regulations require all registrants to "provide effective controls and procedures to guard against theft and diversion of controlled substances."143 The regulations establish specific physical security requirements, which vary depending on the type of registrant and the classification of the controlled substance at issue.144 For example, nonpractitioners must store controlled substances in Schedules I and II in a safe, steel cabinet, or vault that meets certain specifications.145 Nonpractitioners must further ensure that controlled substance storage areas are "accessible only to an absolute minimum number of specifically authorized employees."146 Practitioners must store controlled substances "in a securely locked, substantially constructed cabinet."147 In addition to those physical security requirements, practitioners subject to CSA registration may not "employ, as an agent or employee who has access to controlled substances" any person who has been convicted of a felony related to controlled substances, had an application for CSA registration denied, had a CSA registration revoked, or surrendered a CSA registration for cause.148

Quotas

To prevent the production of excess amounts of controlled substances, which may be prone to diversion, the CSA directs DEA to set production quotas for controlled substances in Schedules I and II and for ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine.149 The DEA Administrator is also required to set individual quotas for each registered manufacturer seeking to produce such substances and to limit or reduce individual quotas as necessary to prevent oversupply.150 With respect to certain opioid medications, the Act further directs the DEA Administrator to estimate the amount of diversion of each opioid and reduce quotas to account for such diversion.151

Relatedly, the Controlled Substances Import and Export Act allows the importation of certain controlled substances and listed chemicals only in amounts the DEA Administrator determines to be "necessary to provide for the medical, scientific, or other legitimate needs of the United States."152

Prescriptions

Under the CSA, controlled substances in Schedules II through IV must be provided directly to an ultimate user by a medical practitioner or dispensed pursuant to a prescription.153 The Act does not mandate that Schedule V substances be distributed by prescription, but such substances may be dispensed only "for a medical purpose."154 As a practical matter, Schedule V substances are almost always dispensed pursuant to a prescription due to separate requirements under the FD&C Act or state law.155

Enforcement and Penalties

DEA is the federal agency primarily responsible for enforcing the CSA's registration requirements.156 If a registrant contravenes the Act's registration requirements, DEA may take formal or informal administrative action including issuing warning letters, suspending or revoking an entity's registration, and imposing fines.157

The DEA Administrator may suspend or revoke a registration (or deny an application for registration) on several bases, including findings that a registrant or applicant has falsified application materials, been convicted of certain felonies, or "committed such acts as would render his registration . . . inconsistent with the public interest."158 Unless the DEA Administrator finds that there is an imminent danger to the public health or safety, the DEA Administrator must provide the applicant or registrant with notice, the opportunity for a hearing, and the opportunity to submit a corrective plan before denying, suspending, or revoking a registration.159 Imminent danger exists when, due to the failure of the registrant to comply with the registration requirements, "there is a substantial likelihood of an immediate threat that death, serious bodily harm, or abuse of a controlled substance will occur in the absence of an immediate suspension of the registration"160 Those conditions are satisfied, for example, when a practitioner prescribes controlled substances outside the usual course of professional practice without a legitimate medical purpose in violation of state and federal controlled substances laws.161

A violation of the CSA's registration requirements—including failure to maintain records or detect and report suspicious orders, noncompliance with security requirements, or dispensing controlled substances without the necessary prescriptions—generally does not constitute a criminal offense unless the violation is committed knowingly.162 However, in the event of a knowing violation DEA, through DOJ, may bring criminal charges against both individual and corporate registrants. Potential penalties vary depending on the offense. For example, a first criminal violation of the registration requirements by an individual is punishable by a fine or up to a year in prison.163 If "a registered manufacturer or distributor of opioids" commits knowing violations such as failing to report suspicious orders for opioids or maintain effective controls against diversion of opioids, it may be punished by a fine of up to $500,000.164

Trafficking Provisions

In addition to the registration requirements outlined above, the CSA also contains provisions that define multiple offenses involving the production, distribution, and possession of controlled substances outside the legitimate confines of the registration system, that is, the Act's trafficking provisions.165 Although the word "trafficking" may primarily call to mind the illegal distribution of recreational drugs, the CSA's trafficking provisions in fact apply to a wide range of illicit activities involving either pharmaceutical or nonpharmaceutical controlled substances.166

Prohibitions

The CSA's trafficking provisions make it illegal to "manufacture, distribute, or dispense, or possess with intent to manufacture, distribute, or dispense, a controlled substance," except as authorized under the Act.167 They also make it unlawful "knowingly or intentionally to possess a controlled substance," unless the substance was obtained in a manner authorized by the CSA.168 Penalties vary based on the type and amount of the controlled substance in question.169 Other sections of the CSA define more specific offenses, such as distributing controlled substances at truck stops or rest areas,170 at schools,171 or to people under age 21;172 endangering human life while manufacturing a controlled substance;173 selling drug paraphernalia;174 and engaging in a "continuing criminal enterprise"—that is, an ongoing, large-scale drug dealing operation.175 An attempt or conspiracy to commit any offense defined under the Act also constitutes a crime.176

Enforcement and Penalties

DOJ enforces the CSA's trafficking provisions by bringing criminal charges against alleged violators.177 Notably, the CSA's registration system and its trafficking regime are not mutually exclusive, and participation in the registration system does not insulate registrants from the statute's trafficking penalties. In United States v. Moore, the Supreme Court rejected a claim that the CSA "must be interpreted in light of a congressional intent to set up two separate and distinct penalty systems," one for registrants and one for persons not registered under the Act.178 The Court in Moore held that physicians registered under the CSA can be prosecuted under the Act's general drug trafficking provisions "when their activities fall outside the usual course of professional practice."179

Numerous judicial opinions provide guidance on what sorts of conduct fall outside the usual course of professional practice. The defendant in Moore was a registered doctor who distributed large amounts of methadone with inadequate patient exams and no precautions against misuse or diversion. The Court held that "[t]he evidence presented at trial was sufficient for the jury to find that respondent's conduct exceeded the bounds of 'professional practice'" because, "[i]n practical effect, he acted as a large-scale 'pusher' not as a physician."180 Appellate courts have relied on Moore to uphold convictions of a pharmacist who signed thousands of prescriptions for sale through an online pharmacy,181 and a practitioner who "freely distributed prescriptions for large amounts of controlled substances that are highly addictive, difficult to obtain, and sought after for nonmedical purposes," including prescribing one patient more than 20,000 pills in a single year.182 But several courts have cautioned that a conviction under Moore requires more than a showing of mere professional malpractice. For instance, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (Ninth Circuit) has held that the prosecution must prove that the defendant "acted with intent to distribute the drugs and with intent to distribute them outside the course of professional practice," suggesting that intent must be established with respect to the nature of the defendant's failure to abide by professional norms.183

For decades, DOJ has brought criminal trafficking charges against doctors and pharmacists who dispensed pharmaceutical controlled substances outside the usual course of professional practice.184 In April 2019, DOJ for the first time brought criminal trafficking charges against a pharmaceutical company—Rochester Drug Cooperative—and two of its executives based on the company's sale of the opioids oxycodone and fentanyl to pharmacies that illegally distributed the drugs.185 Similarly, in July 2019, a federal grand jury indicted defendants including two former executives at the pharmaceutical distributor Miami-Luken, Inc. for conspiracy to violate the CSA's trafficking provisions.186

Violations of the CSA's trafficking provisions are criminal offenses that may give rise to large fines and significant jail time. Penalties vary according to the offense and may further vary based on the type and amount of the controlled substance at issue. Unauthorized simple possession of a controlled substance may prompt a minimum fine of $1,000 and a term of up to a year in prison.187 Distribution of large quantities of certain drugs—including Schedule I controlled substances such as heroin and LSD and Schedule II controlled substances such as cocaine and methamphetamine—carries a prison sentence of 10 years to life and a fine of up to $10 million for an individual or a fine of up to $50 million for an organization.188 Penalties increase for second or subsequent offenses, or if death or serious bodily injury results from the use of the controlled substance.189 Compared with the CSA's registration provisions, prosecution under the Act's trafficking provisions generally entails greater potential liability—particularly for individual defendants—but also entails a more exacting burden of proof.190

The CSA is not the only means to target misconduct related to the distribution of pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical controlled substances. Rather, such conduct can give rise to liability under numerous other provisions of federal and state law. For example, drug companies may face administrative sanctions or criminal charges under the FD&C Act.191 Companies and criminal organizations may be subject to federal charges under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.192 And manufacturers and distributors of opioids currently face numerous civil suits under federal and state law based on the companies' marketing and distribution of prescription opioids.193

Legal Considerations for the 116th Congress

Drug regulation has received significant attention from Congress in recent years, prompting a range of proposals concerning the opioid epidemic; the proliferation of synthetic drugs, in particular analogues to the opioid fentanyl; the divergence between the status of marijuana under state and federal law; and the ability of researchers to conduct clinical research involving Schedule I controlled substances.

Opioid Crisis

One of the most salient current issues in the realm of controlled substance regulation is the opioid epidemic. Opioids are drugs derived from the opium poppy or emulating the effects of opium-derived drugs.194 Some opioids have legitimate medical purposes, primarily related to pain management, while others have no recognized medical use.195 Both pharmaceutical opioids—such as oxycodone, codeine, and morphine—and nonpharmaceutical opioids—such as heroin—may pose a risk of abuse and dependence and may be dangerous or even deadly in excessive doses.196 The CDC reports that overdoses on prescription and nonprescription opioids claimed a record 47,600 lives in 2017.197 The CDC further estimates that the misuse of prescription opioids alone costs the United States $78.5 billion per year.198

In recent years, the opioid crisis has prompted various legislative proposals aiming to prevent the illicit distribution of opioids; curb the effects of the crisis on individuals, families, and communities; and cover the costs of law enforcement efforts and treatment programs. In 2016, Congress enacted the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA)199 and the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act).200 CARA authorized grants to address the opioid crisis in areas including abuse prevention and education, law enforcement, and treatment, while the Cures Act, among other things, provided additional funding to states combating opioid addiction.201 In 2018, Congress enacted the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act), which sought to address the opioid crisis through far-ranging amendments to the CSA, the FD&C Act, and other statutes.202 Key amendments to the CSA under the SUPPORT Act included provisions expanding access to medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction,203 specifying the factors for determining whether a controlled substance analogue is intended for human consumption,204 revising the factors DEA considers when establishing opioid production quotas,205 and codifying the definition of "suspicious order" and outlining the CSA's suspicious order reporting requirements.206

Notwithstanding the flurry of recent legal changes, many recent legislative proposals seek to further address the opioid crisis by amending the CSA.207 For example, the DEA Enforcement Authority Act of 2019208 would revise the standard for "imminent danger" required to support an immediate suspension of DEA registration. Specifically, the bill would lower the threshold for what constitutes imminent danger, requiring "probable cause that death, serious bodily harm, or abuse of a controlled substance will occur in the absence of an immediate suspension of the registration," rather than the current statutory requirement that "a substantial likelihood of an immediate threat that death, serious bodily harm, or abuse of a controlled substance will occur in the absence of an immediate suspension of the registration."209 In addition, the John S. McCain Opioid Addiction Prevention Act210 would, as part of the CSA's registration regime, require medical practitioners applying for new or renewed CSA registration to certify that they will not prescribe more than a seven-day supply of opioids for the treatment of acute pain.211 The LABEL Opioids Act212 would amend the CSA to require that opioids in Schedules I through V bear labels warning that they can cause dependence, addiction, and overdose. Failure to comply with the labeling requirements would violate the CSA's registration requirements.213

Some proposals target specific opioids, especially fentanyl. For instance, the Ending the Fentanyl Crisis Act of 2019214 would amend the CSA to reduce the amounts of fentanyl required to constitute a trafficking offense. The Comprehensive Fentanyl Control Act,215 introduced in the 115th Congress, would likewise have reduced the amount of fentanyl triggering criminal liability. That bill would have also increased penalties applicable to offenses involving fentanyl and provided separate procedures for emergency scheduling of synthetic opioids.216 The Screening All Fentanyl-Enhanced Mail Act of 2019217 seeks to require screening of all inbound international mail and express cargo from high-risk countries to detect and prevent the importation of illicit fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. Finally, the Blocking Deadly Fentanyl Imports Act218 would aim to gather information about the illicit production of illicit fentanyl in foreign countries and to withhold bilateral assistance from countries that fail to enforce certain controlled substance regulations.

Analogue Fentanyl

A related issue currently before Congress is the proliferation of synthetic drugs, especially synthetic opioids. Synthetic drugs are drugs that are chemically produced in a laboratory; they may have a chemical structure identical to or different from that of a natural drug.219 Synthetic drugs are often intended to mimic or enhance the effects of natural drugs, but have chemical structures that have been slightly modified to circumvent existing drug laws.220

One particular concern in this area relates to synthetic opioids, including fentanyl analogues and other fentanyl-like substances. Fentanyl is a powerful opioid that has legitimate medical uses including pain management for cancer patients.221 But, due to its potency, it also poses a particularly high risk of abuse, dependency, and overdose.222 Prescription fentanyl is a Schedule II controlled substance; multiple nonpharmaceutical substances related to fentanyl are controlled in Schedule I.223 However, experts have noted that it is relatively easy to manipulate the chemical structure of fentanyl in order to produce new substances that may have similar effects to fentanyl or pose other dangers if consumed but that are not included in the CSA's schedules.224

Since March 2011, DEA has used its emergency scheduling authority 23 times to impose temporary controls on 68 synthetic drugs, including 17 fentanyl-like substances.225 Most recently, in February 2018, DEA issued an emergency scheduling order that applies broadly to all "fentanyl-related substances" that meet certain criteria related to their chemical structure.226 Absent further action by DEA or Congress, the temporary scheduling order will expire in February 2020.227

Even if not individually scheduled on a temporary or permanent basis, fentanyl-related substances may still be subject to DEA control as controlled substance analogues.228 However, to secure a conviction for an offense involving an analogue controlled substance, DOJ must, among other elements, prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the substance at issue (1) is intended for human consumption and (2) has either a chemical structure substantially similar to the chemical structure of a Schedule I or II controlled substance or an actual or intended effect similar to or greater than that of a Schedule I or II controlled substance.229 Thus, DOJ has stated that analogue controlled substance prosecutions can be burdensome because they raise "complex chemical and scientific issues," and has argued that permanent scheduling of fentanyl analogues will reduce uncertainty and aid enforcement.230

Several proposals in the 116th Congress would seek to permanently schedule fentanyl analogues. For instance, the Stopping Overdoses of Fentanyl Analogues Act231 would permanently add to Schedule I certain specific synthetic opioids, as well as the whole category of "fentanyl-related substances," as defined in the February 2018 emergency scheduling order. The Modernizing Drug Enforcement Act of 2019232 would amend the CSA to add to Schedule I all "mu opioid receptor agonists" not otherwise scheduled, subject to certain exceptions.233 One of the sponsors of the Modernizing Drug Enforcement Act has stated that the bill's aim is "to automatically classify drugs or other substances that act as opioids, such as synthetic fentanyl, as a schedule I narcotic based on their chemical structure and functions," avoiding the need for such substances to be individually scheduled.234

A key challenge in permanently scheduling fentanyl analogues is how to define the substances subject to regulation. Not all analogues of fentanyl have effects similar to fentanyl itself, and due to the large number of potential analogues there are many whose effects are unknown.235 Defining covered substances based on chemical structure may be overinclusive because the definition may include inactive substances, potentially allowing for prosecution of individuals who possess substances that pose no threat to public health and safety.236 On the other hand, such a definition may also be underinclusive because it excludes opioids that are not chemically related to fentanyl or that are made using different modifications to fentanyl's chemical structure.237 Alternatively, defining covered opioids based on their effects rather than their chemical structure could impose a heavy burden on prosecutors, similar to the burden they currently face when bringing analogue controlled substance charges.238

Marijuana Policy Gap

Another area raising a number of legal considerations for the 116th Congress is the marijuana policy gap—the increasing divergence between federal and state law in the area of marijuana regulation.239 As of June 2019, 11 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws removing state prohibitions on medical and recreational marijuana use by adults age 21 or older.240 An additional 35 states have passed laws permitting medical use of marijuana or CBD.241 However, marijuana remains a Schedule I controlled substance under federal law, and state legislation decriminalizing marijuana has no effect on that status.242

Because of resource limitations, DOJ typically has not prosecuted individuals who possess marijuana for personal use on private property, but instead has "left such lower-level or localized marijuana activity to state and local authorities through enforcement of their own drug laws."243 Moreover, in each budget cycle since FY2014 Congress has passed an appropriations rider preventing DOJ from using taxpayer funds to prevent the states from "implementing their own laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of medical marijuana."244 The current appropriations rider is in effect through November 21, 2019.245 Several courts have interpreted the appropriations rider to bar DOJ from expending any appropriated funds to prosecute activities involving marijuana that are conducted in "strict compliance" with state law.246 However, activities that fall outside the scope of state medical marijuana laws remain subject to prosecution. For example, in United States v. Evans, the Ninth Circuit upheld the prosecution of medical marijuana growers who smoked some of the marijuana they grew because the defendants failed to show they were "qualifying patients" who acted in strict compliance with state medical marijuana law.247

Notwithstanding the appropriations rider, marijuana-related activity may still give rise to serious legal consequences under federal law. DOJ issued guidance in 2018 reaffirming the authority of federal prosecutors to exercise prosecutorial discretion to target federal marijuana offenses "in accordance with all applicable laws, regulations, and appropriations."248 Furthermore, regardless whether they are subject to criminal prosecution, participants in the cannabis industry may face numerous collateral consequences arising from the federal prohibition of marijuana because other federal laws impose noncriminal consequences based on criminal activity, including violations for the CSA. For example, cannabis businesses that are legal under state law may be unable to access banking services due to federal anti-money laundering laws,249 and those businesses may be ineligible for certain federal tax deductions.250 The involvement of income from a cannabis-related business may also prevent a bankruptcy court from approving a bankruptcy plan.251 And participation in the cannabis industry, even if legal under state law, may have adverse immigration consequences.252

Numerous proposals currently before Congress aim to address issues related to the marijuana policy gap. Some proposals target specific issues that arise from the divergence between federal and state law. For instance, the Secure And Fair Enforcement Banking Act of 2019 (SAFE Banking Act)253 would seek to protect depository institutions that provide financial services to cannabis-related businesses from regulatory sanctions. The Ensuring Safe Capital Access for All Small Businesses Act of 2019254 would make certain loan programs of the Small Business Administration (SBA) available to cannabis-related businesses.255

Other proposals would seek to address the marijuana policy gap more broadly by attempting to mitigate any conflict between federal and state law. For example, the Strengthening the Tenth Amendment Through Entrusting States Act (STATES Act)256 would amend the CSA to provide that most provisions related to marijuana "shall not apply to any person acting in compliance with State law relating to the manufacture, production, possession, distribution, dispensation, administration, or delivery" of marijuana. The STATES Act would remove the risk of federal prosecution under the CSA for individuals and entities whose marijuana-related activities comply with state law, but the bill does not specifically address the potential consequences of such activity under other areas of federal law. The Responsibly Addressing the Marijuana Policy Gap Act of 2019257 would both remove marijuana-related activities that comply with state law from the scope of the CSA and seek to address specific collateral consequences of such activity, including access to banking services, bankruptcy proceedings, and certain tax deductions. By contrast, the State Cannabis Commerce Act258 would take an approach similar to the current DOJ appropriations rider with respect to all federal agencies: while it would not alter the scope of the CSA's restrictions on marijuana, the State Cannabis Commerce Act would prevent any agency from using appropriated funds "to prevent any State from implementing any law of the State that . . . authorizes the use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of marijuana" within the state.

Additional proposed legislation could address the marijuana policy gap by altering the status of marijuana under the CSA across the board. Some proposals would move marijuana from Schedule I to a less restrictive schedule.259 Others would remove marijuana from the CSA's schedules completely.260

Removing marijuana from the coverage of the CSA could, however, raise new legal issues. For instance, by default, the repeal of federal criminal prohibitions rarely applies retroactively.261 As a result, if Congress were to remove marijuana from the CSA, it might want to consider how to address past criminal convictions related to marijuana and whether to take any action to mitigate the effects of past convictions.262 In addition, Congress would not be precluded from regulating marijuana in other ways if it were to remove the drug from the ambit of the CSA. For instance, legislation has been introduced that would impose new federal regulations on marijuana akin to those applicable to alcohol and cigarettes.263

In addition, descheduling marijuana would not, standing alone, alter the status of the substance under the FD&C Act and, thus, would not bring the existing cannabis industry into compliance with federal law.264 FDA has explained that it "treat[s] products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds as [it does] any other FDA-regulated products," and that it is "unlawful under the FD&C Act to introduce food containing added CBD or THC into interstate commerce, or to market CBD or THC products as, or in, dietary supplements, regardless of whether the substances are hemp-derived."265 FDA is currently engaged in "consideration of a framework for the lawful marketing of appropriate cannabis and cannabis-derived products under our existing authorities."266 Congress could also pass legislation to alter FDA regulation of cannabis-based products. For example, the Legitimate Use of Medicinal Marihuana Act would provide that neither the CSA nor the FD&C Act "shall prohibit or otherwise restrict" certain activities related to medical marijuana that are legal under state law.267

Reducing or removing federal restrictions on marijuana might also create tension with certain treaty obligations of the United States. The United States is a party to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, which requires signatories, among other things, to criminalize "cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction, preparation, possession, offering, offering for sale, distribution, purchase, sale, . . . importation and exportation of drugs" contrary to the provisions of the Convention.268 The United States is also party to the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971, which requires parties to impose various restrictions on controlled substances, including measures "for the repression of acts contrary to laws or regulations" adopted pursuant to treaty obligations.269 The two treaties are not self-executing,270 meaning that they do not have the same status as judicially enforceable domestic law.271 However, failure to abide by its treaty obligations could expose the United States to international legal consequences.272

Research Access

Another significant legal issue before the 116th Congress is the effect of the CSA on researchers' ability to conduct clinical research involving Schedule I controlled substances, including marijuana. Because substances in Schedule I have no accepted medical use, it is only legal to produce, dispense, and possess those substances in the context of federally approved scientific studies.273 In addition, federal law generally prevents the use of federal funding for such research: a rider to the appropriations bill for FY2019 provides that no appropriated funds may be used "for any activity that promotes the legalization of any drug or other substance included in schedule I" of the CSA, except "when there is significant medical evidence of a therapeutic advantage to the use of such drug or other substance or . . . federally sponsored clinical trials are being conducted to determine therapeutic advantage."274 Some commentators have expressed concerns that the CSA places too many restrictions on research involving controlled substances, particularly Schedule I controlled substances that might have a legitimate medical use.275 With respect to clinical research involving marijuana specifically, currently there is one farm that legally produces marijuana for research purposes,276 and researchers have complained that such marijuana is deficient in both quality and quantity.277

In 2015, Congress passed the Improving Regulatory Transparency for New Medical Therapies Act, which imposes deadlines on DEA to issue notice of each application to manufacture Schedule I substances for research and then act on the application.278 In 2016, DEA stated that it planned to grant additional licenses to grow marijuana for research purposes; however, as of June 2019 no new licenses had been granted.279 One applicant for a license petitioned the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (D.C. Circuit) for a writ of mandamus compelling DEA to issue notice of its application.280 In July 2019, the D.C. Circuit ordered DEA to respond to the petition.281 On August 27, 2019, DEA published a notice in the Federal Register (1) providing notice of the 33 applications it has received to manufacture Schedule I controlled substances for research purposes and (2) announcing the agency's intent to promulgate regulations governing the manufacture of marijuana for research purposes.282 The next day, DEA filed a response to the mandamus petition in the D.C. Circuit, asserting that the petition was moot because DEA had issued the requested notice of application.283 The petitioner disputes that the matter is moot and asks the court to retain jurisdiction "to ensure the agency acts with dispatch and processes [petitioner's] application promptly."284 The court has yet to rule on the petition.

DEA's Federal Register notice stated that the agency intends to review all pending applications and grant "the number that the agency determines is necessary to ensure an adequate and uninterrupted supply of the controlled substances at issue under adequately competitive conditions."285 The notice further explained that DEA is engaged in an ongoing "policy review process to ensure that the [marijuana] growers program is consistent with applicable laws and treaties."286 It remains to be seen how many applications DEA will grant and what new regulations will apply to the successful applicants.

As it did with the Improving Regulatory Transparency for New Medical Therapies Act, Congress could pass further legislation to guide DEA's consideration of applications to manufacture marijuana for research purposes. For instance, the Medical Cannabis Research Act of 2019,287 which was introduced before the recent developments in the D.C. Circuit and remains pending before Congress, would aim to increase the number of licenses to produce cannabis for research purposes, requiring DEA to approve at least three additional manufacturers within a year of passage.

Congress could also legislate more broadly to facilitate research involving controlled substances. For example, a proposed amendment to the appropriations bill for FY2020 would have eliminated the appropriations rider restricting the use of federal funding for research involving Schedule I substances.288 That amendment, which would have applied to research involving all Schedule I controlled substances, was intended to facilitate research involving not only marijuana but also psilocybin, MDMA, and other Schedule I drugs that might have legitimate medical uses.289