Introduction

South Africa, a majority black, multiracial country of nearly 59 million people, last held general elections May 2019. The African National Congress (ANC) retained the parliamentary majority that it has enjoyed since the country's first universal suffrage elections in 1994, but it did so with its lowest share of votes since taking power. After the election, the National Assembly reelected President Cyril Ramaphosa (rah-mah-POH-sah). He was first elected in early 2018, after his predecessor, Jacob Zuma, resigned under the threat of a parliamentary no confidence vote after defying a decision by ANC leaders to recall him as the party's national presidential nominee. Zuma had faced intense pressure to step down after years of weak economic growth and multiple corruption scandals under his tenure. The ANC replaced Zuma with then-Vice President Ramaphosa, who had won the party presidency in late 2017. Ramaphosa is leading a reform agenda to address economic malaise and corruption. Local and international expectations of him are high, but he faces diverse fiscal, structural, and political challenges.

U.S. Relations

U.S.-South Africa ties are cordial, based in part on shared democratic values and broad bilateral accord on African development goals, and the State Department describes South Africa as a strategic U.S partner.1 High-level bilateral engagement is not as frequent or as multifaceted as it is with some other U.S. strategic partners, however, and South Africa has attracted very limited legislative attention in recent years. South Africa-related congressional activity has centered mostly on U.S. healthcare assistance, notably regarding HIV/AIDS, and trade issues, including during periodic Member travel to the country. Given South Africa's economic and political influence in Africa and diplomatic sway among developing countries in multilateral institutions, some Members of Congress may see a scope for increased U.S. engagement with South Africa.

There is a large U.S. diplomatic presence in South Africa, which has periodically hosted high-level U.S. leadership visits, including two presidential visits by former President Barack Obama. South Africa has been a top African recipient of U.S. assistance for years. For over a decade, such assistance has centered primarily on healthcare, notably HIV/AIDS-related programs implemented under the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), announced by President George W. Bush in 2003. The United States has also supported South African-implemented development and crisis response activities in other African countries. In 2010, the Obama Administration and the South African government initiated a U.S.-South African Strategic Partnership. While it remains in effect, the last full biennial dialogue was held in 2015. Subsidiary

"bilateral forums" were held in 2016 and 2017 to review cooperation in multiple areas.2

Since 2014, South Africa has been the largest U.S. trade partner in Africa. South Africa is also a key regional export and investment destination for U.S. firms; more than 600 operate in the country, often via local subsidiaries. The United States is South Africa's largest source of all types of foreign investment.3 South Africa has long enjoyed a significant trade surplus in goods with the United States, but there is a substantial U.S. surplus in trade in services. In general, while U.S.-South African economic ties are positive, trade has been a source of occasional friction. Differences over foreign policy issues also periodically roil ties. South African officials are critical of Israel's policies toward the Palestinians, for instance, and South Africa maintains cordial relations with Iran, a key U.S. adversary. There have also been divergences on other issues, as illustrated by a lack of congruence between South African and U.S. votes in the United Nations, and regarding responses to the crisis in Venezuela and targeted sanctions on Zimbabwean officials.4 South Africa opposed the Trump Administration's decision to withdraw the United States from the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, a shift from the general bilateral policy congruence on this issue during the Obama Administration.

South African officials have periodically made remarks suggesting anti-U.S. biases. Anti-U.S. rhetoric, when it occurs, may be influenced by historic grievances over U.S. policy toward the ANC during the era of apartheid—a codified, state-enforced system of racial segregation and socioeconomic and legal discrimination favoring the white minority that was operational until the early 1990s.5 During the anti-apartheid struggle, the Reagan Administration categorized the ANC as a terrorist organization and President Reagan vetoed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-440). The Reagan Administration sought to promote change within the apartheid regime—with which it shared anti-communist goals—by engaging with the regime in a dialogue-based approach dubbed "constructive engagement."

The Trump Administration has not pursued any major changes in bilateral ties, but in late 2018, President Trump acted to fill the post of U.S. ambassador to South Africa, vacant since late 2016, by nominating South African-born luxury handbag designer Lana Marks for the position. The Senate confirmed her for the post in late September 2019. In early 2017, President Trump spoke to President Zuma by telephone on "ways to expand" trade and advance bilateral cooperation in other areas, including counter-terrorism and, according to the South African government, multilateral and African peace and stability issues.6

No notable new engagement has since occurred, but in August 2018, President Trump sparked controversy in South Africa and among some U.S. observers after posting a tweet on land reform. It stated that the South African Government was "seizing land from white farmers" and referred to "farm seizures and expropriations and the large scale killing of farmers." His comments drew criticism and were questioned on factual and other grounds by U.S. and South African commentators7 and by the South African government.8 While the South African government is pursuing efforts to change the constitution to allow for the uncompensated expropriation of land, such expropriation was not underway in 2018.

Congress has long played an active role in U.S.-South African relations. This was particularly true during the struggle against apartheid, from the late 1960s until the first universal franchise vote in 1994. Starting in the 1960s, Congress sought to induce democratic change by repeatedly imposing conditions and restrictions on U.S. relations with the apartheid regime. These efforts culminated in Congress's enactment—in votes overriding President Reagan's veto—of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-440). Congressional attention toward South Africa remained strong during its continuing transition over the following decade. In recent years, congressional engagement with South Africa has mainly focused on oversight of foreign aid program—particularly South Africa's relative progress in building its capacity to address its HIV/AIDS crisis and gradually assuming greater responsibility for HIV program financing and implementation, key goals under PEPFAR.9

Efforts to bolster trade and investment ties with South Africa, as with Africa generally, have also drawn attention in recent congresses. In 2015 and 2016, congressional action, including Congress's mandating of a special review of South Africa's eligibility for U.S. trade benefits, helped to resolve a poultry and meat-related trade dispute. Several Members also sought to reverse the Trump Administration's 2018 application of steel and aluminum tariffs to South Africa, which had raised concerns in the country. No South Africa-centered bills have been introduced in the 116th Congress.10 Members periodically travel to South Africa to foster such aims as improved bilateral and U.S.-Africa ties and enhanced trade and investment relations.11

U.S. Assistance12

The State Department's FY2020 foreign aid budget request contains limited discussion of South Africa, but according to the Department's FY2019 foreign aid budget request, the country

is a key player for U.S. engagement in Africa and a critical partner to boost U.S. trade and economic growth, improve regional security, and mitigate public health crises. South Africa is the economic and security anchor of the region but grapples with political and socioeconomic challenges, including high-level corruption and poor accountability, a slowing economy, high youth unemployment, critical levels of violent crime, a weak education system, a high rate of HIV/AIDS, water scarcity, and wildlife trafficking. South Africa continues to work with the United States to address the region's social and economic challenges […].13

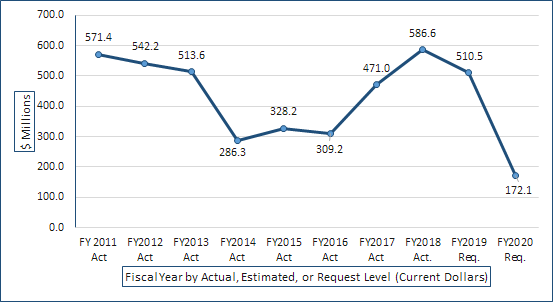

Combined State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) aid for South Africa totaled $586.6 million in FY2018. The Trump Administration requested $510.5 million for South Africa for FY2019 and $172.1 million for FY2020. The latter would represent a 71% decrease relative to actual FY2018 levels and a 66% decrease relative to the FY2019 request, and center solely on health assistance.14 On aid level trends, see Figure 1 and Table 1.

Since 1994, South Africa has been a top African recipient of State Department and USAID aid, the vast majority devoted to PEPFAR and other health programs, including responses to the tuberculosis epidemic and efforts to end child and maternal deaths. After the enactment of the U.S. Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-25), which authorized PEPFAR programs and funding, aid for South Africa rose from $29 million in FY2003 to nearly $580 million in FY2010. Aid levels then declined to a low of $286 million in FY2014 before rising again, to a peak of nearly $587 million in FY2018. PEPFAR funding for South Africa totaled $6.26 billion from FY2004 through FY2018. The FY2019 PEPFAR country operational plan for South Africa prioritizes maintaining current levels of HIV/AIDS antiretroviral drug treatment access, expanding treatment access in high-burden districts and high-volume facilities and HIV prevention programs, and enhancing program quality. Details on FY2020 planning are not yet available.

|

PEPFAR Program Criticisms and Planned Funding Cuts The State Department has proposed to cut PEPFAR funding by 67.6% in FY2020, to $161.8 million, after issuing sharp criticism of the PEPFAR in South Africa in its FY2019 PEPFAR Country Operational Plan "Planning Level Letter." While praising a number of successes under the U.S. PEPFAR partnership with the South African government and commending efforts to improve the program, the letter—by U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and U.S. Special Representative for Global Health Diplomacy Deborah L. Birx—took note of "several fundamental problems in PEPFAR's core treatment program in South Africa." The letter stated Despite a significant infusion of resources by the U.S. government especially over the last three years, progress has been grossly sub-optimal and insufficient to reach epidemic control, including the targets of the Surge Plan [an effort to accelerate HIV testing, treatment, and retention]. The PEPFAR program has demonstrated extremely poor performance in ensuring every person who is started on treatment is retained, particularly from FY 2017 to FY 2018 where results have been relatively stagnant at 479,912 to 481,014 respectively, despite an increase in resources. In fact, the PEPFAR program lost more people on treatment than it gained in FY 2018. Across PEPFAR/South Africa programming, FY 2018 overspending and underperformance at the partner level is a program management and oversight issue. [..] The full expenditure of PEPFAR resources without improvement of results is unacceptable. This represents a serious, continued problem and program failure–linkage and retention must improve in South Africa […].15 |

Other recent-year U.S. development aid for South Africa has supported programs focusing on

- basic education;

- civil society capacity-building aimed at fostering accountable and responsive governance and public service delivery advocacy, and support for the office of the Public Protector [a public ombudsman; see below];

- business-government cooperation in support of development; and

- support for sexual assault and gender-based-violence victims.

The USAID-led Power Africa initiative supports energy projects in South Africa and USAID provides indirect credit for small enterprise activity. Through its Africa Private Capital Group, USAID also facilitates development-focused financing, including though efforts to foster local municipal bond and pension fund investment in public goods and services. USAID also has provided support for development-centered policymaking and administers the Trilateral Assistance Program (see below), under which the United States supports South African foreign aid efforts in Africa. South Africa has served as a "Strategic Partner" under the Feed the Future U.S. global food security/agricultural development initiative by providing agricultural technical aid to other African countries. South Africa also participates in the joint State Department/USAID Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI), which helps develop the leadership skills of young business, civic, and public sector professionals, and hosts a YALI Regional Leadership Center.

|

|

Source: State Department annual congressional budget justifications. |

Most U.S. development assistance programs in South Africa are administered by the State Department and USAID. These agencies sometimes collaborate with and transfer funds to other, technically specialized U.S. agencies, notably the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which plays a key technical role in PEPFAR implementation. Other U.S. agencies periodically fund generally small, functionally-specific programs. U.S. export promotion agencies periodically provide loans, credit guarantees, or other financial services to U.S. or local firms aimed at boosting U.S. exports and fostering development and economic growth. There is a Peace Corps program in South Africa and the U.S. African Development Agency (USADF) provides a few grants in the country. Some project-centered grant aid is also provided to civil society entities, and South Africa periodically benefits from U.S. regional programs focused on such issues as environmental management and trade capacity-building. U.S. trade and export promotion agencies are also active in South Africa.

Security cooperation efforts are diverse but have been funded at far lower levels than development programs. In FY2017 and prior years, International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) funds were used for law enforcement and criminal justice technical support. Except in FY2018, Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs (NADR)-Export Control and Related Border Security (EXBS) funds have supported technical training relating to trade and border control, with a focus on controlling trade in military and dual-use technologies. The International Military Education and Training (IMET) program is long-standing, and in the mid-2010s, Foreign Military Financing (FMF) aid supported the South African military's capacity to respond to regional crises and participate in peacekeeping. Such aid included technical support and training for U.S.-sourced South African military C-130 aircraft. Since 2005, South Africa has received peacekeeping training under the U.S. Africa Contingency Operations Training and Assistance program (ACOTA), a component of the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI, a multi-country State Department training program) and other U.S. military professionalization programs. South African troops also regularly join their U.S counterparts in military training exercises. There is a South Africa-New York National Guard State Partnership Program, and the U.S. Department of Defense also regularly supports South Africa's biennial African Aerospace Defense Exhibition.

Table 1. South Africa: State Department/USAID Aid by Account

(Current $ in millions, actual or requested. Numbers may not sum due to rounding)

|

Account |

FY2016 Actual |

FY2017 Actual |

FY2018 Actual |

FY2019 Request |

FY2020 Request |

|

Total |

309.3 |

471.0 |

586.6 |

510.5 |

172.1 |

|

Development Assistance (DA) |

6.9 |

6.5 |

5.0 |

- |

- |

|

Foreign Military Financing (FMF) |

0.3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Global Health Programs–State (GHP-State) |

284.9 |

450.1 |

560.1 |

500.0 |

161.8 |

|

Global Health Programs–USAID (GHP-USAID) |

15.3 |

13.0 |

20.8 |

9.6 |

9.6 |

|

International Military Education & Training (IMET) |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

|

International Narcotics Control & Law Enforcement (INCLE) |

1.0 |

0.2 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining & Related Programs (NADR) |

0.3 |

0.3 |

- |

0.3 |

- |

Source: State Department annual foreign aid budget justifications; and USAID congressional notification.

Country Overview

South Africa is influential on the African continent due to its investment and political engagement in many African countries and its active role and leadership within the inter-governmental African Union (AU). It also has one of the largest, most diverse and developed economies, and has made substantial progress in spurring post-apartheid socioeconomic transformation, though many negative socioeconomic effects of apartheid persist and the country has experienced a multi-year period of low economic growth. (For summary data on the country, see Figure 2.)

Apartheid ended after a tumultuous negotiated transition, between 1990 and 1994, when South Africa introduced a system of universal suffrage and multi-party democracy—after a decades-long struggle by the ANC and other anti-apartheid groups. After the release of long-imprisoned ANC leader Nelson Mandela and the ANC's legalization in 1990, political dialogue led to an interim constitution in 1993 and elections in 1994, in which Mandela was elected president. Further post-vote negotiations led to the adoption in 1996 of a new constitution and the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC, in operation until 2002). The TRC documented crimes and human rights abuses by the apartheid regime and anti-apartheid forces between 1960 and 1994, and oversaw processes of restorative justice, accountability, and assistance for victims. It has since served as a model for similar efforts around the world, though observers have repeatedly criticized the government's arguably lackluster efforts to prosecute apartheid-era human rights offenders and provide TRC-recommended reparations.16 Mandela died in 2013.17

The ANC, which currently holds 230 of 400 National Assembly seats, has held a parliamentary majority since the first post-apartheid elections in 1994—and, since the National Assembly elects the president, also controlled the executive branch. Successive ANC-led governments have sought to redress the effects of apartheid, notably through efforts to improve the social welfare of the black majority and by promoting a pan-racial, multiethnic national identity. While racial relations have improved, divisions remain; references to race in politics and social media sometimes spur heated debate, and racially motivated criminal acts periodically occur.

Despite diverse investments and policies aimed at overcoming the negative effects of apartheid, many of its most damaging socioeconomic effects endure, posing persistent, profound challenges for development and governance.18 Among these are high levels of poverty, social inequality, and unemployment, as well as unequal access to education, municipal services, and other resources. Such problems disproportionately affect the black population. Racial disparities have gradually declined, but most black South Africans live in poverty and their average per capita incomes are roughly one-sixth as large as those of the historically privileged white minority.

Income and consumption distribution are notably unequal. Recent measures suggest the wealthiest top 10% and top 20% in South Africa enjoy the highest share of income of any country. South Africa's GINI coefficient—a measure of income or consumption inequality—is consistently among the highest globally, and is often the highest. There are also significant regional, rural-urban, and intra-racial socioeconomic disparities.19 Large segments of the poor majority lack access to decent housing and adequate infrastructure services (e.g., electricity and water), especially in rural areas and in the vast, high-density informal settlements surrounding most cities. Known as townships, such settlements are populated mostly by poor black and mixed race "coloured" inhabitants.20 Lack of legal property ownership sometimes subjects township dwellers to municipal squatter eviction and slum clearance operations.

There is also extreme racial disparity in access to land, despite implementation of land redistribution and restitution initiatives since 1994. Under such programs, the state has purchased large amounts of land intended to be transferred to populations that had limited or no ability to own land under the apartheid system—primarily those of black, "coloured" or Indian descent. While, black ownership and other access to land has risen markedly in some provinces since 1994, redistribution and restitution processes have been slow and resulted in les extensive transfers than initially projected. As a result, the small minority white population continues to own over 70% of land nationally. This has spurred growing demands for uncompensated state expropriation of private land and pushed the ANC to pursue an ongoing effort to amend the constitution to permit expropriation of land without compensation.

|

Figure 2. South Africa at a Glance (2019 data unless otherwise noted) |

|

|

||||||||||

Sources: Map by CRS. Data from CIA World Factbook (2018), World Bank Development Indicators and IMF World Economic Outlook databases (April 2019); Statistics South Africa, Mid-Year Population Estimates 2019, Release P0302, July 29, 2019, and Quarterly Labour Force Survey Quarter 2: 2019, Release P0211, July 30, 2019; and U.S. Census Bureau, International Data Base (September 2018).

South Africa faces a range of other socioeconomic challenges. Labor strikes and unrest are common, particularly in the mining sector. Rates of violent crime—notably murder, rape, and gun crime—are high.21 The causes are diverse and but are often viewed by analysts as being rooted in grievances and fractures arising from socioeconomic inequality and marginalization, social biases and, in some instances, criminal activity.22 Extremely violent, drug dealing street gangs exert extensive power in many large informal settlements. In July 2019, the military was deployed to help police counter a spate of murders in one such settlement in the city of Cape Town.23

|

Femicide and Violence Against Women and Children South Africa has one of the world's highest per capita rates of gender-based violence (GBV) and rape. Children often are the victims of such offenses. These are matters of ongoing public and policymaker concern. In September 2019, a series of murders and rapes targeting women spurred several mass protests. These developments prompted President Ramaphosa—who had addressed the nation on femicide and GBV weeks earlier and hosted a National Summit Against GBV in late 2018—to cancel a planned visit to the 74th U.N. General Assembly session. He instead convened and addressed a special parliamentary session on GBV as well as recent xenophobic violence (see below). Ramaphosa called South Africa "one of the most unsafe places in the world to be a woman, with levels of violence that are comparable to countries that are at war" and also cited a high level of violence against girls, including babies.24 In his remarks, Ramaphosa announced the immediate implementation of a six-month national Emergency Action Plan. It seeks to strengthen GBV prevention and criminal justice responses to GBV, including offender sanctions, and enhance GBV-related laws and policies, victim support programs, and women's economic empowerment programs.25 Past administrations have struggled to make progress on these issues. Several brutal, high-profile instances of femicide and child murder in 2012 and 2013 spurred the Zuma administration to sponsor a National Commission of Enquiry into rape and GBV and launch an anti-rape education campaign, but these problems remain widespread and persistent. |

Broader challenges to social cohesion include widespread de facto residential racial and socioeconomic segregation. While many of the poor live in townships, the wealthy, including many whites, often live in gated, highly secured communities. Others include crime-motivated attacks on white farmers and xenophobic mob violence targeting foreigners, notably foreign merchants. Several large-scale attacks of this nature have occurred in 2019, following similar widespread anti-foreigner violence in 2008 and 2015. Multiple smaller-scale attacks also have occurred. In addition to perceived socioeconomic marginalization by foreign commercial actors, analysts have linked such attacks to anti-foreigner political rhetoric and lack of preventative state action. A series of attacks in September 2019 caused a sharp diplomatic rift between South Africa and Nigeria, as many Nigerian immigrants were victims. Nigerian leaders boycotted a South Africa-hosted World Economic Forum annual meeting, and some South African businesses in Nigeria suffered retaliatory attacks.26 Diplomatic tensions also rose with other African countries.

South Africa also faces criminal justice system capacity challenges. Although the country has a relatively well-resourced national police force, there are periodic reports of vigilante mob justice, and police sometimes use heavy-handed, abusive tactics to respond to crime and public unrest.27 Several police leaders have been implicated in professional misconduct inquiries or corruption.

Another key challenge is South Africa's high HIV prevalence. Statistics South Africa, a state agency, estimates that 18.99% of adults were HIV-positive in 2018, up from 2017 (18.88%).28 Despite this moderate increase, which is partially attributable to increased survival rates due to improved access to anti-retroviral treatment, there has been a steady decline in the annual growth rate of HIV prevalence (total cases) and incidence (new infections). National efforts to counter HIV have received considerable international support, notably under U.S. PEPFAR programs.

Citizens' expectations and their demands for rapid socioeconomic transformation have exceeded what the South African state has been able to provide, due to fiscal, technical, and governance shortfalls. Despite large investments in housing, services, infrastructure, and state technical capacities, public goods and services delivery rates and quality have often been inadequate.29 This has spurred frequent, sometimes violent demonstrations. While known as service protests, they center on many issues, including local public corruption and cronyism, and can have political repercussions.30 In April 2018, President Ramaphosa cut short an overseas trip to address a spate of interrelated unrest that featured service delivery protests, attacks on foreigners, anger over alleged corruption by the affected province's then-Premier (governor), and clashes between local rival ANC members.31 In 2015 and 2016, South Africa also experienced mass student protests, some violent, over university education costs and alleged institutional racism in higher education. The current government is implementing a pledge, made just before the end of the Zuma administration, to fund free higher education for the poor and freeze certain other fees.32

Despite such challenges, and indications of an increased politicization of the state bureaucracy under Zuma, many national state agencies (e.g., the central bank, the statistical agency, the courts, some ministries, and the treasury) possess substantial institutional and technical capacity. South Africa ranked second globally on the International Budget Partnership's 2017 Open Budget Index, a measure of public budget transparency. While some state-owned enterprises (SOE) are struggling to recover from reported mismanagement and malfeasance under Zuma, these entities manage large, sophisticated national transport, telecommunication, energy, and other infrastructure systems. The state also administers a large welfare system that supported about 17.6 million grants as of September 2018 and had a 2017/2018 annual budget of about $10.5 billion.33 It is viewed by many observers as a key anti-poverty tool, albeit a costly one that is expected to grow in size and expense. Despite its role in helping to reduce extreme poverty, reported maladministration of the system has spurred considerable controversy in recent years.

Politics and Governance

The ANC party is ideologically leftist, but in practice it has melded pragmatic support for private sector-led growth with state-centric economic planning under what it terms the "developmental state" model. The ANC's political credibility is largely founded on its leading role in the anti-apartheid struggle and its efforts to end South Africa's deep-rooted, enduring social inequalities. It has struggled to build on this legacy, however, amid the country's persistent challenges. Increasingly, voters appear to be judging the ANC on its current performance, and it faces a growing number of opposition parties. Nevertheless, notwithstanding a loss of electoral strength in recent elections, it has maintained its parliamentary dominance.

National Assembly elections take place under a party-list proportional representation system, in which voters select a party and each party allocates its share of elected seats according to an internal party list. As a result, internal ANC politics and leadership selections play a key role in national politics. Rivalry within the ANC at the provincial and local levels—often regarding appointments to local state bodies and the selection of slates of delegates to national party decision-making bodies—is often fierce, and in numerous cases has led to political assassinations.34 The most important ANC post is that of party president, since the ANC usually nominates its party leader to serve as national president. The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP) also exert influence within the ANC. They do so through a compact called the Tripartite Alliance, under which the ANC appoints top members of COSATU and the SACP to party leadership and state posts, and the latter organizations do not independently contest elections. The Alliance weakened during Zuma's tenure due to SACP and COSATU criticism of Zuma, intra-COSATU splits linked to the emergence of new unions, and discontent within the ANC's labor constituency.35

The Democratic Alliance (DA) is the second-largest party in parliament, with 84 of 400 National Assembly seats. The DA has its origins in various historical liberal-leaning party coalitions. For many years, its leaders were predominantly white, but it has built an increasingly strong base among blacks. Now led by a charismatic young black leader, Mmusi Maimane, the DA has often confronted the ANC in parliament, at times in league with the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a populist hard-left party centered on black empowerment.

The EFF was formed in 2013 by a former dissident ANC Youth League leader, Julius Malema, and won 25 seats in the 2014 elections, becoming the third-largest party. It substantially increased its vote share in elections in May 2019, and now holds 44 seats. Malema, a political firebrand, is a former key Zuma supporter who later broke with Zuma. The ANC expelled him in 2012, and he became one of Zuma's most vocal critics, notably regarding corruption—though he and his EFF co-founder have themselves faced corruption allegations. The EFF styles itself as a workers' party and draws its support from socioeconomically marginalized groups (e.g., jobless youth, low-wage workers, and poor communities). The EFF operates as a disruptive force, both in its radical policy proposals and through its often-boisterous obstruction of parliamentary proceedings.

The Inkatha Freedom Party, with origins in Zulu-dominated KwaZulu-Natal province, was a fierce ANC rival during the end of the anti-apartheid period. It is now a self-described centrist party and holds 14 seats, making it South Africa's fourth largest political party. The Vryheidsfront Plus (Freedom Front Plus) party, which advocates for minority rights and self-determination and other policies, notably to protect interests of predominantly white Afrikaners, holds ten seats. The remaining 18 seats are distributed among nine small parties.

A key target campaign demographic for all parties is the "Born Free" generation, those born in 1994 or later, who make up roughly 47% of the population and about 14% of the eligible electorate. They share discontent over corruption, public services, and poverty with their older counterparts, and suffer even higher unemployment rates, but they are reportedly less engaged in formal politics and vote at lower rates than older citizens.

|

2019 Election Opposition parties have successfully exploited growing voter dissatisfaction with the ANC—notably regarding growing corruption, though some EFF leaders have themselves faced corruption allegations—and won significant victories in local elections in 2016. Those polls were seen as a test of ANC strength ahead of the 2019 general elections; in 2016, the ANC won less than 60% of the aggregate national vote for the first time since 1994, and retained majority control of only three of the eight largest urban areas after opposition parties formed coalitions. On May 8, 2019, South Africa held its sixth post-apartheid National Assembly and provincial legislative elections. In the National Assembly elections, the ANC won 57.5% of votes nationwide and 230 out of 400 seats (down from 249 in the last election in 2014). This allowed it to maintain the majority it has won in every post-apartheid general election, but represented the ANC's worst electoral performance since 1994. The main opposition party, the DA, won 22.7% of the vote, giving it 84 seats (down from 89 in 2014), while the EFF made a large gain, winning 10.8% of the vote and 44 seats (up from a 6.4% vote share and 25 seats in 2014). The fourth-largest party, the Inkatha Freedom Party, also made a gain, winning 14 seats, up from 10. Small parties won the remaining seats.36 Following the election, on May 22, the parliament reelected incumbent President Cyril Ramaphosa.37 |

Checks and Balances

During Zuma's presidency, both the DA and the EFF, as well as private foundations and NGOs, sought to use the courts as a check on executive power by regularly suing state officials, including Zuma. These suits, relating to alleged executive branch overreach, agency malfeasance, and illicit actions, were often successful.38 In March 2016, for instance, the Constitutional Court ruled that Zuma had unconstitutionally defied the Public Protector's binding recommendation that he partially reimburse the state for the cost of a state-funded upgrade to his private compound, a matter of long-standing controversy. The DA used the ruling as the basis for initiating an impeachment motion against Zuma that failed but was seen as a political blow against Zuma. In a separate DA-initiated case, a High Court panel ordered in April 2016 that the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) review its 2009 decision to dismiss a 1990s arms purchasing corruption case against Zuma (see below). The Zuma administration faced a third legal setback in March 2016, when the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled that the government had unlawfully ignored a court order—and violated local and international law obligations—by not detaining then-Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir when he attended a mid-2015 African Union (AU) summit in South Africa. Bashir faces an International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrant. The government later sought to formally withdraw South Africa as a party to the ICC. This spurred further litigation. In early 2017, a court determined that the withdrawal was unconstitutional.

Former Public Protector Thuli Madonsela also repeatedly issued reports that documented alleged acts of malfeasance, noncompliance with laws and regulations, corruption, and operational shortcomings by the executive branch and state agencies under its purview. Her reports also ordered corrective actions. Most notably, in late 2016, she issued State of Capture, a highly critical report centering on Zuma and the Guptas, a family of business owners that reportedly maintained very close and allegedly often corrupt relations with Zuma and a network of his political and business associates (see below).39 The report alleged that these actors had engaged in extensive high-level state malfeasance, and mandated the establishment of the now-ongoing judicial commission of inquiry. Zuma fought an unsuccessful legal battle to prevent the report's release, claiming that Madonsela had violated his due process rights. The clash was closely watched, as it was seen as a test of Madonsela's transformation of her office into a key independent institutional check on executive power. A state capture inquiry is ongoing.

Ramaphosa Administration

Ramaphosa—a former anti-apartheid activist and labor leader turned business executive—succeeded Zuma as president in early 2018, weeks after narrowly winning a highly contentious party leadership election. He won the post based largely on his pledge to fight corruption and heal the economy.40 His victory resulted in the defeat of an influential ANC faction linked to Zuma and its favored candidate, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma (Zuma's ex-wife and a former government minister and African Union Commission chair). Analysts speculated that if she had been elected, she might have enabled Zuma to remain national president until general elections in 2019 and potentially helped to avert his prosecution for corruption.

President Ramaphosa's priorities are to reverse what many observers contend was a marked, extensive deterioration in governance under Zuma and to enhance state agency operational efficacy, especially with regard to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Another key goal is to spur faster, more inclusive economic growth by stimulating public and private investment in order to create jobs, enhance social services and infrastructure, and expand gross domestic product (GDP). Particular emphases include "transformation" efforts aimed at expanding and equalizing access to economic opportunities, particularly for the black population. Efforts in this vein include small business promotion, preferential state procurement, and actions to boost industrial growth. Other priorities are reform and growth in mining and trade, along with efforts to attract local and international investment, spur digital sector growth, and expand agricultural production.

The Ramaphosa administration backs a planned constitutional amendment to permit the expropriation of private land without compensation for redistribution to victims of apartheid-era discrimination and land seizures. In early 2018, the parliament provisionally endorsed this goal, which the ANC had adopted as a party policy in late 2017. In late 2018, after holding nationwide hearings, a parliamentary constitutional review committee formally recommended the adoption of this change. Parliament endorsed the recommendation and appointed a committee to craft and introduce the amendment. This effort is highly controversial. It has raised fears that such seizures would primarily target white minority farmers, who own most farmland, and sparked concern that it might cause international investors to question the security of private property ownership in South Africa. Ramaphosa, seeking to dampen such fears, has contended that expropriation would apply mainly in cases involving "unused land, derelict buildings, purely speculative land holdings, or… where occupiers have strong historical rights and title holders do not occupy or use their land, such as labour tenancy, informal settlements and abandoned inner-city buildings."41

Governance Reform and Accountability

Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan—who twice served as finance minister under Zuma but clashed fiercely with him—is spearheading efforts to strengthen state-owned enterprise (SOE) governance and efficacy. President Ramaphosa is directly involved in these efforts; in April 2018, he ordered probes into irregularities and mismanagement at two major SOEs: Eskom, the national power utility, and Transnet, a transport and logistics firm. His administration also replaced these SOEs' boards, along with that of Denel, an important but ailing defense sector SOE. In late 2018, Ramaphosa also fired the head of the tax service—a key Zuma ally and Gordhan foe—after earlier suspending him and appointing a commission of inquiry into alleged malfeasance at the agency. A separate parliamentary commission also probed systematic irregularities at Eskom.

Broader state investigations into and accountability for an allegedly widespread, deep-seated pattern of alleged corruption and influence peddling under Zuma, known locally as "state capture," also continue to roil politics and draw intense public attention. State capture refers, in particular, to the activities of a network of Zuma-allied ANC and business associates, notably the Guptas, an Indian émigré family that accumulated a range of business holdings after arriving in South Africa in the 1990s. This network allegedly participated in corrupt high-level state-business collusion to influence and even control state enterprises and other agency decisions, contracts, regulatory processes, and fiscal assets to advance their financial and political interests.42

Ongoing, high-profile hearings by a judicial commission of inquiry into state capture are a key component of such investigations. Several separate commissions of inquiry have also examined or are probing alleged malfeasance at various state agencies, as well as the alleged extralegal manipulation of state security agencies for political purposes. The latter regard included the creation of ad hoc intelligence networks that worked in parallel to state agencies and the use of mass digital surveillance to target perceived foes of the Zuma administration. In response to such actions, a court recently invalidated parts of a key digital surveillance law.43 To supplement the work of the various commissions of inquiry, in early 2019 President Ramaphosa appointed a special tribunal to fast-track recovery of public assets lost to graft.44

Zuma established the state capture judicial commission in early 2018, as ordered by a court, after earlier resisting doing so. While its proceedings center on developments during his administration, the matters under consideration remain key issues of current policymaking concern and many of the actors at issue remain active in public affairs.45 Witnesses have implicated the Guptas in efforts to influence state agency decisions and top official appointments under Zuma, which the Guptas have denied. The inquiry has revealed evidence of systematic corruption by other actors, notably Bosasa, a public and prison services provider. Its contracts were cancelled and its leaders arrested after hearings in early 2019.46 In testimony before the commission in July 2019, Zuma denied a range of allegations against him, which he attributed to a campaign of character assassination against him by unnamed local and foreign intelligence services, and labeled his relationship with the Guptas benign.47

The ongoing hearings could reveal evidence leading to new charges against Zuma and the Guptas, who reportedly fled to Dubai. The hearings also may have contributed to the ANC's weakened showing in the 2019 election, and could continue to shape the current political environment and undermine Ramaphosa's standing should members of his administration be implicated in malfeasance.48 In 2018, Former Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, a once-reputed anti-Zuma reformer, resigned after testifying to having links to the Guptas. His successor is Tito Mboweni, a business executive and former head of the central bank, whose appointment drew business support. In late 2018, Minister of Home Affairs Malusi Gigaba—a close Zuma ally who was popular within the ANC and whom Ramaphosa had retained—also resigned in 2018 over a perjury accusation and a sex tape scandal.49

Ramaphosa himself faces campaign finance accusations. Public Protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane has accused him of violating the law and misleading parliament by improperly disclosing a political contribution to his 2017 ANC leadership campaign from the corruption-plagued Bosasa firm (see above). Ramaphosa also faces questions over a 2014 donation contribution to the ANC.50 Mkhwebane has endeavored to require that Ramaphosa censure Gordhan and that law enforcement authorities take action against the minister for his role in setting up an allegedly extrajudicial tax enforcement intelligence unit and ostensibly misleading parliament about a meeting with Gupta family members. Gordhan has sharply questioned Mkhwebane's investigatory motives and methods in a legal fight seeking to void her action.51

Meanwhile, Zuma is being tried on 16 charges of fraud, corruption, racketeering, and money laundering in a long-running corruption case centering on a 1990s-era state arms deal scandal. Zuma fended off the case for years, allegedly aided by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). In 2018, however, the NPA was forced to reinstate the charges after an appeals court upheld a 2016 High Court ruling that the NPA's dismissal in 2009 of the case against Zuma had been "irrational" and made under political pressure. The trial is likely to proceed for months. The NPA's alleged improper favoritism toward Zuma drew substantial attention, notably under its former Director, Shaun Abrahams, but also under several of his Zuma-appointed predecessors accused of various irregular actions. In August 2018, a court voided Abrahams's appointment in a case linked to litigation over his predecessors' appointments. In late 2018, Ramaphosa appointed Shamila Batohi, a career prosecutor and former International Criminal Court legal adviser, to head the NPA. She has prioritized state capture and public agency malfeasance cases, but stated that success would require a lengthy rebuilding of a "broken and dysfunctional" criminal justice system. Batohi contends that she inherited an NPA plagued by a "deliberate attempt" to stymie high-profile corruption cases. Such action was potentially exemplified by the NPA's withdrawal of a key criminal case against the Guptas hours prior to Batohi's appointment.52

Ramaphosa: Political Prospects

President Ramaphosa took power just over a year prior to the May 2019 elections. This presented him both with challenges and opportunities: time enough to demonstrate a strong will to pursue economic and governance reform and fight corruption, but arguably not enough time to make substantive progress toward those objectives or consolidate his power within the ANC and unify a splintered party. While the ANC emerged from the elections with a weaker mandate, it might have fared far worse had Ramaphosa not pursued a reform agenda.53 One of Ramaphosa's key challenges going forward is to overcome divisions within the top tiers of the ANC. Some Zuma-aligned party elites—several of whom have faced corruption allegations and/or may be at risk of prosecution due to more proactive law enforcement efforts under Ramaphosa—have sought to obstruct his agenda.54 More generally, Ramaphosa faces longstanding challenges reflected in public anger over poor public services and continuing economic malaise. While he currently appears to enjoy broad public approval, such positive regard may gradually be waning.55

Ramaphosa may continue to face criticism and challenges from Public Prosecutor Mkhwebane, a reputed Zuma ally. Mkhwebane has issued multiple reports questioning actions by the Ramaphosa administration. Critics accuse her of undermining reform efforts and overstepping her mandate. She has also lost in several legal proceedings, and courts have repeatedly questioned her judgment.56 In July 2019, the Constitutional Court ruled that she had lied under oath, prompting calls for her disbarment as a lawyer and a prospective parliamentary review of her appointment.57 The court ruling came in a case arising from an investigation by Mkhwebane into an apartheid-era bank bailout by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB).58

The Economy

South Africa has the most diversified, industrialized economy in Africa. It also has one of the top-five-highest GDPs per capita ($6,331 in 2019) in sub-Saharan Africa, and is one of very few upper-middle-income countries in the region. As earlier noted, however, income distribution is highly unequal.59 South Africa is a top producer of mined raw and processed commodities (e.g., platinum, steel, gold, diamonds, and coal). Other major industries include automobile, chemical, textile, and food manufacturing. These sectors, part of an overall industrial base that contributed just under 26% of GDP in 2017, are important sources of jobs. There are also well-developed tourism, financial, energy, legal, communications, and transport sectors, which are part of an overall services sector that contributed nearly 61% of GDP in 2018.60 Recent GDP trends are provided in Table 2. South Africa regularly hosts large global development and business events, and South African firms are active across Africa, particularly in the mobile phone, retail, and financial sectors. Some also operate internationally, and the Johannesburg Stock Exchange is among the 20 largest global bourses. South Africa is also a famed wine producer and exports diverse agricultural products, but only about 10% of its land is arable and agriculture makes up less than 2.2% of GDP.

Despite its substantial economic strength, South Africa's annual GDP growth, which stood in the 5% range in the mid-2000s, has slowed. It stood at 0.8% in 2018. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects growth of 1.2% in 2019 and a rise to 1.8% in 2021. While the nominal value of GDP has slowly risen in constant local Rand terms since 2010, exchange rate volatility has caused the value of GDP in dollars to fluctuate greatly, which has major implications for the country's terms of trade, international debt servicing, and integration into global manufacturing chains. In dollar terms, GDP fell from a peak of $417 billion in 2011 to $296 billion in 2016, as the Rand weakened sharply against the dollar, before rising to $349 billion in 2017, as the Rand appreciated.61

|

Indicator/Year |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

||||||||||

|

GDP (Current Rand, Billions) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

GDP (Current U.S. dollars, Billions) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Real GDP Growth (Annual % Change; Constant Rand)a |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Real GDP Growth Per Capita (Annual % Change; Constant Rand)b |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Inflation, Consumer Prices (Annual % Change) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Unemployment (Annual; % of Labor Force) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indicator |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

|

Exports of Goods and Services |

||||||

|

Value (current $ in billions) |

110.3 |

95.7 |

90.6 |

103.5 |

110.1 |

|

|

Annual % Growth |

3.6 |

2.9 |

0.4 |

-0.7 |

2.6 |

|

|

Value as % of GDP |

31.5 |

30.2 |

30.6 |

29.6 |

29.9 |

|

|

Imports of Goods and Services |

||||||

|

Current $ in billions |

115.6 |

99.9 |

89.1 |

99 |

108.9 |

|

|

Annual % Growth |

-0.6 |

5.4 |

-3.9 |

1 |

3.3 |

|

|

Value as % of GDP |

33 |

31.5 |

30.1 |

28.3 |

29.6 |

|

|

Total Trade in Goods and Services |

||||||

|

Exports and Imports, Current $ in billions |

225.9 |

195.6 |

179.7 |

202.5 |

219.0 |

|

|

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI; $ in billions) |

||||||

|

Inflows (to South Africa) |

5.8 |

1.7 |

2.2 |

2.0 |

5.3 |

|

|

Inward Stocks (FDI held in South Africa) |

138.9 |

126.8 |

135.5 |

156.1 |

128.8 |

|

|

Outflows (from South Africa abroad) |

7.7 |

5.7 |

4.5 |

7.4 |

4.6 |

|

|

Outward Stocks (South African FDI held abroad) |

146.0 |

154.7 |

175.6 |

276.5 |

238.0 |

|

Sources: Trade date: World Bank, World Development Indicators database. Investment data: U.N. Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Annex Tables, World Investment Report 2018.

Global factors contributing to low growth in recent years have included weak investor confidence, attributed to uncertain economic policy trends and alleged poor governance under Zuma, and periods of weak prices and sluggish global demand for key commodity exports, notably to China. While weak commodity prices may hurt national export earnings, they can also reduce the cost of raw material imports used by many local producers, including exporters.

South Africa has a generally open foreign direct investment (FDI) regime, although investors face high taxes, currency exchange volatility, substantial regulatory burdens, large locally entrenched firms, and Black Economic Empowerment policy compliance costs (see below).62 Moreover, some foreign investors have expressed discontent over the enactment in late 2015 of a law known as the Protection of Investment Act, which removed most special FDI rights and requires foreign investors to settle most disputes through the South African legal system. This has raised concern about potentially unequal treatment under the law and the possibility of expropriation, which South African law permits in some narrow instances.

After several years of stagnation, FDI flows into South Africa have jumped in recent years, rising from $2 billion in 2017 to $5.3 billion in 2018, though they remain lower than a peak of $9.2 billion in 2008. Meanwhile, outward flows have declined, dropping from $7.4 billion in 2017 to $4.6 billion in 2018. See Table 3 for summary trade and FDI trends. The auto industry has been an important source of job-intensive FDI; South Africa has long hosted Ford plants, and other automakers (e.g., Toyota, BMW, and Nissan) have announced significant manufacturing capacity investments in recent years. Rail locomotive manufacturing has also attracted FDI.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) ranked South Africa as the second most competitive economy in 2018 in sub-Saharan Africa (after Mauritius), but assessed it as 67th globally. The WEF has cited as economic strengths South Africa's large market size, relatively good infrastructure, advanced financial system, and innovation capability, but views its research and development capacities as inadequate.63 The country's World Bank Doing Business 2019 rankings (82nd globally and fourth in Africa) are middling (and unchanged from 2018), and its ranking has dropped over the past decade. The survey also suggests that ease of doing business varies within sub-regions of the country, and that national improvements are possible.64

South Africa's private sector is relatively dynamic, although firms face a highly unionized labor force, rigid labor laws and, in some industries, sector-wide wage and working condition agreements negotiated between large firms and unions. Such factors arguably tend to protect incumbent jobholders, reduce labor market flexibility, and limit formal sector economic opportunities for the unemployed and poor—thus contributing to the country's chronically high unemployment rates. South Africa has long had a minimum wage in select sectors, but has only recently enacted a general minimum wage law.65 Sectoral labor agreements have mixed outcomes. They can help firms and industry groups to maintain predictable and stable labor costs and work rules, but often favor the incumbent firms and unions who negotiate them. Oligopolies in some sectors also hinder competition and spur high prices for some locally produced goods.66

There are also skill and geographical mismatches between labor demand and supplies, and low skill levels in some segments of the labor force. This is, in part, an enduring legacy of population and economic controls and discriminatory education and training patterns under apartheid. Chronically high unemployment may also suggest that the labor pool is under-utilized, whether due to skills deficits or a lack of jobs, which may undercut income earning, spending, demand, and other economic growth potentials.67 Information and communication (ICT) adoption rates are low and uneven, and education quality ranks poorly in international comparisons, despite large investments in the sector, which has negative impacts on workforce capabilities.68

Key tools for reversing structural racial disparities are Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) policies, which seek to promote racial equality and economic inclusion using market-based incentives. As a condition of obtaining public contracts, private firms must also comply with BEE requirements, in particular a scorecard-based system ranking firms by factors such as racial inclusiveness in ownership and management, investment in skills development for historically disadvantage persons, and prioritization of commercial ties with other BEE-compliant firms. BEE policies can impose compliance costs on firms and limit hiring choices, and have been criticized in some instances for favoring the interests of middle- and upper-income blacks.

The private sector also faces state competition, as state-owned firms enjoy regulatory preferences in some sectors, even though their performance has often been poor. According to the IMF, SOEs

play a major role, often with limited competition, in providing key products/services, such as power, telecommunications, and transportation (e.g., ports, airways). Their performance thus affects not only the public finances and the borrowing costs of the whole economy, but also economic growth and job creation through the cost of important inputs for a wide range of businesses and households. […G]enerally, there is a need to allow private firms to compete on a more equal footing with large SOEs.69

South Africa's sovereign credit ratings are low and have fallen sharply in recent years. Rising public deficits and debt are also a challenge. Other domestic factors hindering growth include social service delivery challenges and unmet infrastructure needs, which undercut productivity potentials and hurt South Africa's attractiveness as an investment destination.70 Electricity generation deficits and plant maintenance delays have led to periodic rolling power blackouts (see below). The country also has faced several recent droughts, including one that resulted in extreme water shortages in Cape Town, a global tourist destination with a population of 3.7 million people. Continuing water shortage challenges are likely.

Ramaphosa has been spearheading an initiative to attract $100 billion worth of new investment over five years. As of October 2018, the government had solicited $55 billion in FDI commitments.71 Such commitments include recent investments announced by U.S. firms such as McDonalds, Procter and Gamble, Microsoft, and Amazon, as well as United Airlines' entry into the U.S.-South Africa nonstop airline market, alongside Delta Airlines.72

The government is also continuing a range of efforts to reduce unemployment, poverty, and socioeconomic inequality, to improve education and healthcare, and to unite a geographically and racially divided society. Such actions are guided by the 20-year National Development Plan (NDP). Crafted by a Ramaphosa-headed commission and issued under Zuma, it is supplemented by multiple shorter-term, sector-specific plans. The NDP emphasizes investments in social services and state operational capacities. It fosters efforts to boost employment and incomes, including labor-intensive growth strategies and state investment in large-scale infrastructure, especially in the transport, communications, and power sectors. NDP implementation has been hampered by the poor governance and policy inconsistency under Zuma, the intractability and extensive scope of the country's challenges, and financing limitations.

Energy and Natural Resource Issues

Energy issues—particularly electrical power sector challenges—are a sensitive political topic, as they have the potential to influence the economy and political prospects for the ANC and have in some cases been tied to state capture allegations.

Power Sector. Periodic rolling electricity blackouts caused by power generation shortages due to plant maintenance shortfalls and breakdowns are a key energy challenge. They are attributable to multiple factors, including years-long delays and overspending on the construction of two massive new coal-fired plants. Other factors include poor performance by the state-owned national power utility, Eskom. It suffers from massive debt, low credit ratings, and chronic liquidity problems, and has been plagued by reported mismanagement and malfeasance, including in relation to questionable Gupta-related coal and uranium supply deals.73 This has spurred substantial public and opposition party ire and government criticism, especially when Eskom has requested power rate hikes. Eskom has also drawn criticism for continuing to rely heavily on coal, despite pledging to expand renewable power generation, a government-supported goal.

Eskom's generation shortfalls are a key policy challenge because they affect economy-wide productivity, and its $30 billion in state-backed debt hurts the country's sovereign debt rating and ability to borrow. Amidst worsening power shortages, the government plans to fund a three-year, $4.9 billion restructuring of Eskom that is to split it into three state-owned entities focused on generation, transmission and distribution respectively. Eskom had sought the transfer of some Eskom debt to the general public debt ledger, and recently won part of a requested 15% rate increase, despite mining industry opposition.74

Nuclear Power Generation. South Africa is the only African country with a commercial nuclear power plant. The Zuma administration planned to increase the county's 51,309 MW of power generation capacity by 9,600 megawatts (MW) by 2030 by constructing six to eight new nuclear power plants. It pursued pre-bid negotiations with firms from Russia, France, China, the United States, and South Korea, all countries that had signed bilateral commercial nuclear cooperation agreements with South Africa. The project's estimated cost ranged widely, between $30 billion and $100 billion. Cost and environmental concerns spurred substantial opposition to the plan, as did opacity surrounding pre-bid negotiations with Russia.

Due to the lack of concrete cost estimates, the Treasury refused to authorize the release of a formal vendor request for proposals. Leaked details regarding accords with Russia and its Rosatom SOE suggested that a deal would have strongly favored Russian SOE financial interests. Broader concern grew after reports that Shiva Uranium—a firm controversially acquired by the Guptas—was in the running to produce fuel for the plants, amid indications of possible initial procurement irregularities.75 In April 2017, the High Court invalidated the nascent procurement process on procedural grounds. It also voided bilateral pre-procurement agreements with Russia and broad nuclear technical cooperation agreements with the United States (signed in 1995) and South Korea (signed in 2010).76 The court's ruling essentially required the government to begin its procurement effort anew. The Ramaphosa administration, while remaining open to a mix of energy source options, has not expressed support for an expansion of nuclear power in South Africa. Russia, however, is actively pressing for a new nuclear power deal with South Africa.

Natural Gas. The prospect of significant domestic natural gas production from hydraulic fracturing of natural gas-rich shale ("fracking") is also hotly debated. Supporters see natural gas as a less polluting alternative to coal, South Africa's main electricity generation fuel, and local gas production as a way to reduce reliance on energy imports and generate jobs. Opponents, especially farmers, have cited possible contamination and overuse of water resources, notably in the environmentally sensitive semi-desert Karoo region, where most of an estimated 390 trillion cubic feet of recoverable shale gas reserves are located. Such concerns spurred a 2011 moratorium on exploration. It was later lifted, but a 2017 High Court ruling invalidated national fracking regulations. The Ramaphosa administration has pledged to fast-track applications and regulatory requirements to enable new exploration.77

Mining. Mining sector reform is another focus of debate. In 2017, the Zuma administration issued a draft mining charter—a document setting out industry-wide policy requirements with the aim of increasing black economic participation and benefit. It drew widespread industry concern. The charter would have required renewed compliance with a black mine ownership share quota of 30% if current black owners sold or transferred their shares in a mining asset. It would also have required firms to give partial in-kind ownership rights to mine workers and nearby community groups, and pay them dividends. The Ramaphosa administration revised and later adopted a new charter that allows firms to remain compliant with black ownership requirements once they are met—even if black ownership shares fall below the 30% threshold. It also permits firms to make payment in place of worker and community shares and recover the value of such shares, eliminates dividends for such owners, and requires compliance with BEE regulations for mining firms involved in public procurement transactions.78

U.S. Trade and Investment Issues

South Africa has been the largest U.S. trade partner in Africa since 2014, though its global significance is relatively moderate. In 2017, it was the 36th-largest source of U.S. imports and the 42nd-largest U.S. export destination globally. Bilateral trade in goods in 2018 totaled $14.1 billion ($5.5 billion in U.S. exports and $8.5 billion in U.S. imports), down from a peak of $16.7 billion in 2011, while trade in services in 2017 (latest data) totaled $4.8 billion ($2.9 billion in U.S. exports and $1.9 billion in U.S. imports).79 In 2018, U.S. FDI stock in South Africa stood at $7.6 billion, and centered on manufacturing, notably of chemicals and food, professional and technical services, and wholesale trade. South African FDI stock in the United States totaled $4.3 billion.80

A U.S.-South Africa Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) signed in 2012 facilitates bilateral trade and investment dialogues, and there is a bilateral tax enforcement and cooperation treaty, and a double taxation treaty. South Africa also is eligible for duty-free benefits under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA, P.L. 106-200, Title I, reauthorized in 2015 for 10 years under P.L. 114-27), but not for special AGOA apparel benefits. Its $1.5 billion in AGOA exports to the United States in 2018 (excluding Generalized System of Preferences benefits)—13% of all such exports—made it the largest non-oil-focused AGOA beneficiary and the third largest overall, although the value of its exports under AGOA has fallen since peaking at $2.5 billion in 2013.81 A 2018 U.S. International Trade Commission study, U.S. Trade and Investment with Sub-Saharan Africa: Recent Developments, found potential for significantly greater bilateral trade in a range of goods.

|

Alleged Improprieties by Local Affiliates of U.S. and European Firms The local affiliates of several U.S. and European services firms active in South Africa have drawn negative attention in recent years. Local units of several blue chip firms, including McKinsey, KPMG, HSBC, and SAP, became embroiled in Gupta-related scandals, and as a result have lost clients and have faced South African and foreign regulatory and criminal probes. SAP admitted to illicit acts pertaining to the payment of nearly $10 million in commissions to Gupta-linked firms to secure South African SOE digital technology contracts. In 2017, SAP also faced U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission inquiries under the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act related to its South Africa activities. The consulting firms KPMG and McKinsey allegedly provided Gupta-owned firms and allied actors with accounting and consultancy services that violated various auditing or other due diligence standards, and in some cases may have involved improper and potentially illegal acts. In April 2018, the South African government barred KPMG from auditing state agencies.82 In a separate matter, an ongoing, multi-year probe by South Africa's Competition Commission (Compcomm) of multiple large banks—including local affiliates of some major U.S. banks—found that several had engaged in currency trade price rigging collusion. In April 2017, Citibank NA admitted to illicit currency trading and agreed to pay a $5.2 million penalty and cooperate with Compcomm's prosecution of 18 other banks. Compcomm, which initially recommended that the banks be fined 10% of their annual local trading volume, is proceeding with legal actions against the banks. U.S. authorities have also become involved; in early 2019, Standard Chartered Bank pled guilty to currency manipulation in an agreement with the New York State Financial Services Department.83 |

During the 2015 AGOA reauthorization debate, various stakeholders raised questions about South Africa's continued AGOA eligibility. Two issues drew particular attention. One was concern over South Africa's reciprocal trade agreements with other advanced economies, notably that of the European Union (EU). Some in the U.S. private sector argued that a South Africa-EU agreement that gives EU firms preferential South African tariff treatment places U.S. firms at a competitive disadvantage. (In contrast, AGOA gives South African firms preferential access to U.S. markets, but does not give U.S. firms reciprocal access to South African markets.) AGOA eligibility criteria include rules on reciprocal third-party agreements, but no country has lost its eligibility under these criteria. The second issue was concern over the large size and advanced character of South Africa's economy, particularly relative to its African peers, which some have argued make it a U.S. competitor in some sectors. South Africa is the only country to make significant use of AGOA in the export of advanced manufactured products, notably motor vehicles and related parts, though such exports fell by over half in 2018.84

Some stakeholders cited these two issues to argue that stricter income requirements were needed to ensure that AGOA benefits target the least-developed countries in Africa, and to encourage South Africa to negotiate a reciprocal U.S. trade agreement. Others contended, conversely, that South Africa's exports of high-value items showed that AGOA preferences were working as intended, by helping to improve South Africa's economic development. They also asserted that removing South Africa from AGOA might undermine intra-regional trade, since South Africa is a key trade partner of many other African countries, which AGOA is designed to encourage. While no significant changes were made affecting South Africa's AGOA eligibility, these issues may continue to draw congressional scrutiny.85 South African import restrictions on certain agriculture products also temporarily threatened its AGOA eligibility, both before and after the 2015 AGOA reauthorization, and led to a bilateral trade dispute. It focused on South African anti-dumping duties and other restrictions on imports of certain U.S. poultry, pork, and beef products. The dispute was resolved in 2016, when South Africa lifted these restrictions following intensive bilateral engagement initiated under an out-of-cycle 2015 review of South Africa's eligibility.

The Trump Administration's imposition of U.S. tariffs on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%) in March 2018 under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (P.L. 87-794, as amended) roiled bilateral trade ties, but differences over the issue were resolved.86 In October 2018, the South African government reported that the Administration had granted Section 232 duty exclusions for U.S. imports of 161 aluminum and 36 steel products, largely allaying South African concerns. This action followed South Africa's unsuccessful effort to seek the tariffs' removal, requests from several Members of Congress seeking an exemption from these tariffs for South Africa, and U.S. firms' requests for these exclusions.87

An additional U.S. Section 232 investigation on imports of automobiles and certain automotive parts could result in the imposition of additional U.S. tariffs on such imports, reportedly up to 25%, including on such imports from South Africa.88 In 2018, a South African government representative argued against such tariffs on a variety of grounds at a U.S. Commerce Department hearing on the matter. In early 2019, the Commerce Department submitted a nonpublic report on an investigation into U.S. imports of these products to President Trump, who in May 2019 stated that U.S. imports of these products may "threaten to impair" U.S. national security.89 The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), under President Trump's direction, is working on potential negotiated solutions to the threat asserted by the President. How South Africa would be affected is not clear; as currently envisioned, such negotiations would center on larger U.S trade partners that are significantly larger than South Africa. An exclusion similar to that granted to South Africa in relation to steel and aluminum tariffs is also a possibility.90

Other issues with implications for South Africa's AGOA participation include intellectual property concerns set out by the U.S.-based International Intellectual Property Alliance (IIPA), regarding South Africa's Copyright Amendment Bill. In 2018 and 2019, the IIPA testified before annual AGOA eligibility review hearings that the bill would weaken IPR holders' rights, make South Africa noncompliant with AGOA and other international IPR agreements, impose burdens on IPR holders, and disincentivize intellectual property development. Others who provided comments to the USTR on these issues disputed such claims. The bill has not yet been enacted into law.91 South Africa's move to expropriate land without compensation could also potentially affect South Africa's AGOA eligibility, although there are no overt signs of such a shift.92 A range of other issues with implications for U.S. investment are addressed in the State Department's annual Investment Climate Statements publication.93

Foreign Policy Issues

U.S.-South Africa bilateral relations are generally friendly, although there are periodic differences over foreign policy issues. While there is often broad U.S.-South African accord on selected multilateral issues (e.g., nuclear proliferation), African regional development goals and, in some cases, responses to political or military crises in the region, in multilateral fora, South Africa backs developing country positions that are at times inconsistent with stated U.S. interests. South Africa has also criticized some U.S.-backed international interventions (e.g., in Iraq and Libya) and taken stances toward Cuba, the Palestinian cause, and Iran that are at odds with U.S. positions. It has also forged increasingly close economic ties with China. Such ties may be viewed negatively by the Trump Administration.94

South African Efforts in Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is a key focus of South African foreign policy. Its regional activities are multifaceted, but focus on investment; peacekeeping, stabilization, and conflict mediation; and the economic and other development priorities of the African Union (AU) and other sub-regional organizations (e.g., the Southern African Development Community or SADC). It also often helps coordinate or represent African views in multilateral fora on such issues as climate change, African peace and security issues, U.N.-African cooperation, and developing country priorities. South Africa is serving as a nonpermanent member of the U.N. Security Council (UNSC) during 2019 and 2020; some analysts see this as affording South Africa with an opportunity to revitalize its international role following what some see as a period of foreign policy drift under Zuma.95 A key South African aim during its UNSC tenure is to convince Council members to adopt a proposal under which assessed contributions from U.N. member countries would finance 75% of the cost of AU-led peacekeeping operations.