Introduction

Many Members of Congress have demonstrated an interest in the mandates, effectiveness, and funding status of U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa as an integral component of U.S. policy toward Africa and a key tool for fostering greater stability and security on the continent. As a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council (the Council) with veto power, the United States plays a key role in establishing, renewing, and funding individual operations, including those in Africa. The United States is the largest financial contributor to U.N. peacekeeping.

This report provides an overview of active U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa, including their mandates, budget and funding mechanisms, key challenges, and U.S. policy toward each mission. It does not address broader U.N. peacekeeping issues or missions elsewhere, non-U.N. peacekeeping and stabilization efforts in Africa, or the activities of the U.N. Support Office in Somalia (UNSOS), which is a U.N.-authorized logistics mission that supports the African Union (AU) Mission in Somalia (AMISOM).1

For related information, see CRS In Focus IF10597, United Nations Issues: U.S. Funding of U.N. Peacekeeping; CRS In Focus IF11171, Crisis in the Central African Republic; CRS In Focus IF10116, Conflict in Mali; CRS In Focus IF10218, South Sudan, and CRS Report R45794, Sudan's Uncertain Transition; CRS Report R43166, Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations; and CRS Report RS20962, Western Sahara.

Setting the Context: U.N. Peacekeeping Operations

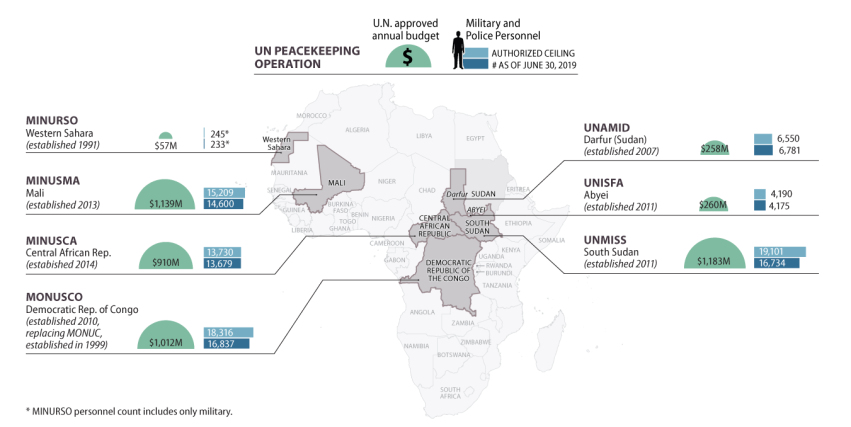

As of August 2019, the United Nations conducts 14 peacekeeping operations worldwide comprising more than 100,000 military, police, and civilian personnel.2 Of these operations, seven are in Africa (Figure 1):

- the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), established by the Council in 2014;

- the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), established in 2013;

- the U.N. Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA), established in 2011;

- the U.N. Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), established in 2011;

- the U.N. Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, MONUSCO), established in 2010 to succeed the U.N. Organization Mission in the DRC (MONUC);

- the U.N.-African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), established in 2007; and

- the U.N. Mission for the Organization of a Referendum in the Western Sahara (MINURSO), established in 1991.

These include the world's four largest U.N. peacekeeping operations by actively deployed uniformed personnel: MONUSCO, UNMISS, MINUSMA, and MINUSCA.

The Africa operations illustrate how U.N. peacekeeping has significantly evolved since the first mission was established in the Middle East in 1948.3 U.N. peacekeeping once involved implementing cease-fire or peace agreements (as is the case for MINURSO, the oldest of the current Africa operations). Since the 1990s, however, the U.N. Security Council has increasingly authorized operations in complex and insecure environments where there may be no peace to keep and little prospect of a near-term resolution. Peacekeepers, particularly those operating in African missions, are increasingly asked to protect civilians, help extend state authority, disarm rebel groups, work with humanitarian actors, assist in restoring the rule of law, and monitor human rights, often in the absence of a comprehensive or effective cease-fire or peace settlement.

Establishment and Budget

Members of the Security Council vote to adopt resolutions establishing and renewing peacekeeping operations. The resolutions specify the mission mandate and timeframe and authorize a troop ceiling and funding level for each mission. The Council generally authorizes the U.N. General Assembly (the Assembly) to create a special account for each operation funded by assessed contributions by U.N. member states. The Assembly adopts the peacekeeping scale of assessments every three years based on modifications of the U.N. regular budget scale, with the five permanent Council members assessed at a higher level for peacekeeping than for the regular budget. The latest U.S. peacekeeping assessment, adopted in December 2018, is 27.89%. Other top contributors include China (15.22%), Japan (8.56%), Germany (6.09%), and France (5.61%).4 The approved U.N. budget for the 2019/2020 peacekeeping fiscal year is $6.51 billion. Of this amount, $4.82 billion (nearly 75%) is designated for the seven missions in Africa.5 U.N. members voluntarily provide the military and police personnel for each peacekeeping mission. Peacekeepers are paid by their own governments, which are reimbursed by the United Nations at a standard rate determined by the Assembly (about $1,428 per soldier per month). Some African countries—including Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Ghana—are among the largest troop contributors.6

Some experts and observers have expressed concern regarding possible funding shortages for U.N. peacekeeping operations, particularly those in Africa, and the impact it could have on their effectiveness. In a March 2019 report to the General Assembly (A/73/809), U.N. Secretary-General (SG) António Guterres noted an increase in the number of peacekeeping missions that are frequently cash constrained due to member state payment patterns and arrears, and "structural weaknesses" in peacekeeping budget methodologies, including inefficient payment schedules and borrowing and funding restrictions.7 These issues have led to some cash shortages, delays in reimbursements to some troop contributing countries (TCCs), and increased risks to "not only the functioning of its [U.N.] peacekeeping operations but also the people who serve in difficult environments."8 Ongoing difficulties in paying for peacekeeping operations could have implications for the internal stability of top African TCCs, which may view U.N.-funded troop salary reimbursements as a tool to reward and/or placate their large and potentially restive militaries. To help address the aforementioned issues, SG Guterres proposed several reforms that have been implemented or are under consideration by U.N. member states.9 The extent to which these efforts might improve the peacekeeping financial situation remains to be seen.

U.S. Funding

Congress authorizes and appropriates U.S. contributions to U.N. peacekeeping. Some Members have expressed an ongoing interest—via legislation, oversight, and public statements—in ensuring that such funding is used as efficiently and effectively as possible. U.S. assessed contributions to U.N. peacekeeping operations are provided primarily in annual State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations bills through the Contributions for International Peacekeeping Activities (CIPA) account.10

Congress has often debated the level and impact of U.S. funding for U.N. peacekeeping. In the early 1990s, the U.S. peacekeeping assessment was over 30%, which many Members of Congress found too high. In 1995, Congress set a 25% cap on funding authorized after 1995. Over the years, the gap between the actual U.S. assessment and the cap has led to shortfalls in peacekeeping funding. The State Department and Congress have often covered these shortfalls by raising the cap for limited periods through SFOPS appropriations measures, and allowing for the application of U.N. peacekeeping credits (excess U.N. funds from previous peacekeeping missions) to fund outstanding U.S. balances. During the Obama Administration, these actions allowed the United States to pay its assessments to U.N. peacekeeping missions in full. Congress has elected not to temporarily raise the cap since FY2016. In addition, since mid-2017, the Trump Administration has allowed for the application of peacekeeping credits up to, but not beyond, the 25% cap. As a result, the State Department estimates that the United States accumulated more than $700 million in cap-related arrears through the CIPA account in FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019 combined (in addition to other peacekeeping arrears).11 These are distributed across U.N. operations, including those in Africa.

The Trump Administration has voted for the renewal and funding of existing U.N. peacekeeping operations. At the same time, it has been critical of overall and Africa-specific U.N. peacekeeping activities and called for a review of operations to ensure that they are "fit for purpose" and more efficient and effective.12 Most recently, the Administration's FY2020 budget proposed $1.13 billion for U.N. peacekeeping operations, a 27% reduction from the enacted FY2019 level of $1.55 billion (see Table 1 for a breakdown by African operations). The proposal states the Administration's "commitment to seek reduced costs by reevaluating the mandates, design, and implementation" of missions and to sharing the cost burdens "more fairly" among countries.

|

U.N. Peacekeeping Operation |

Approved U.N. 2018/19 Budget |

U.S. FY2019 Estimate |

U.S. FY2020 Request |

% Change (Est. vs. Req. |

||||

|

MINUSCA (Central African Republic) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

MINUSMA (Mali) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

UNMISS (South Sudan) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

UNISFA (Abyei) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

UNAMID (Darfur) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

MONUSCO (D.R. Congo) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

MINURSO (W. Sahara) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

TOTAL |

|

|

|

|

Sources: See U.N. document A/C.5/73/21, July 3, 2019, and Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2020, p. 44.

Notes: The U.S. and U.N. numbers in this table may not align due the differences between the U.N. peacekeeping fiscal year (July 1 to June 30) and the U.S. fiscal year (October 1 to September 30).

In addition to its assessed contributions, the United States supports African troop and police contributors by providing training and equipment on a voluntary, bilateral basis. The State Department's Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI) is one key source of funding for such support, funded through the SFOPS Peacekeeping Operations (PKO) account as well as ad hoc regional funding allocations. The State Department also provides police assistance through its International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) account.

Selected Policy Issues

U.S. support for expanding or maintaining individual U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa—or for approving new operations in response to emerging conflicts on the continent—has fluctuated over time. During the Obama Administration, the United States backed new operations in the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali—both times at the urging of France, an ally and fellow permanent member of the U.N. Security Council—while overseeing the closure of long-standing operations in Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire as those countries stabilized in the aftermath of internal conflicts. U.N. Security Council members have not formally proposed new U.N.-conducted operations in Africa during the Trump Administration to date, although some have voiced support for authorizing U.N. assessed contributions and/or logistical support for an ongoing African-led operation in the Sahel region (see "African-led operations" below).<del> </del>

Despite shifts in policy and on the ground, several overarching policy issues and debates continue to arise regarding U.N. peacekeeping in Africa. These fall into several categories discussed below.

Civilian protection mandate fulfillment. Policymakers have debated what changes, if any, can or should be made to enable U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa to fulfill mandates to protect civilians. This issue has been particularly salient with regard to MONUSCO (in DRC) and MINUSCA (in CAR). Both missions' mandates place a high emphasis on civilian protection amid ongoing conflicts and severe logistics and personnel protection challenges. Armed groups have repeatedly massacred civilians at close proximity to U.N. operating sites. Restrictions (or "caveats") imposed by troop-contributing countries on their forces' deployments, often attributable to force protection concerns, may impede civilian protection efforts in some cases.

Mass atrocities. Some experts and observers have debated whether U.N. peacekeeping operations are an effective tool for preventing or addressing mass atrocities. U.S. support for MINUSCA's creation was nested within a high-level effort to prevent further mass atrocities in CAR; fulfilling this goal has proven challenging. In Mali, militias have engaged in a spate of civilian massacres in the center of the country, a region that was largely outside the purview of MINUSMA until the 2019 mandate renewal (as discussed below).

Role of host governments. A key challenge is how and to what extent U.N. peacekeeping operations should pursue positive working relationships with host governments whose interests may not align with international stabilization efforts. In practice, peacekeeping personnel may require approvals from host governments to acquire entry visas or access certain parts of the country, for example. Pursuit of positive relations may, however, undermine perceptions of U.N. neutrality or trustworthiness in the context of an active conflict and/or state abuses. U.N. operations in CAR, DRC, and Mali, among others, are mandated to support the extension of state authority, although state security forces are a party to internal conflicts. These same U.N. missions are also tasked with facilitating peace talks between the government and rebel groups. Operations in Sudan and South Sudan have faced obstructions and threats from government officials and security forces, and the role of state security forces in attacks on civilians complicates the missions' civilian protection and reporting mandates.

Counterterrorism. Some policymakers have questioned what role, if any, U.N. peacekeeping operations should play in addressing transnational terrorism in Africa. This debate has repeatedly arisen in the context of Mali, and may become relevant in other places (such as DRC, where the Islamic State has claimed ties to a local militia group). Despite calls from the Malian government and other regional leaders, the Security Council has declined to mandate MINUSMA explicitly to conduct counterterrorism operations, notwithstanding the mission's civilian protection and stabilization mandates.

Sexual exploitation and abuse by U.N. peacekeepers. Members of Congress have demonstrated an ongoing interest in how the United Nations might better address sexual abuse and exploitation by U.N. peacekeepers—particularly in MONUSCO and MINUSCA, which have the highest rates of substantiated allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation.13 Congress has enacted several provisions to address the issue. For example, SFOPS bills since FY2008 have prohibited the obligation of U.N. peacekeeping funding unless the Secretary of State certifies that the United Nations is implementing effective policies and procedures to prevent U.N. employees and peacekeeping troops from engaging in human trafficking, other acts of exploitation, or other human rights violations.14

African troop-contributing countries (TCCs). Experts and policymakers have debated the advantages and drawbacks of relying on African countries to contribute the bulk of military and police personnel to U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa.15 African troop contributors may be willing, but they often display capacity shortfalls and/or poor adherence to human rights standards. For example, in CAR, in a single year (2016), peacekeepers from the Republic of Congo and DRC—among others—were implicated in the abuse of minors, while Burundi's police contingent was repatriated due to abuses by its police services at home.16 In Mali, which has been the deadliest environment for U.N. peacekeepers since MINUSMA's establishment, top troop contributors include Burkina Faso, Chad, Senegal, and Togo—which are among the world's poorest countries. Moreover, troop contributors that border the host country may have bilateral political interests that complicate their participation in peacekeeping operations. Some countries may also wield their contributions to such missions to deflect international criticism of their domestic political conditions.

|

African Union (AU) Funding Proposal17 In 2016, the AU backed a proposal under which AU member states would cover an increased share of the cost of African-led stabilization operations, in exchange for the potential to receive U.N. assessed funding for the remainder of the cost on a case-by-case basis. AU financing is to be raised primarily through a continent-wide tariff on imports and member state assessments. The Trump Administration has expressed broad support for the AU's efforts to self-finance 25% of its "Peace Fund" by 2025, while criticizing the import tariff as likely to incur violations of World Trade Organization (WTO) obligations. In addition, the Administration has stated a preference for providing U.S. support to African-led stabilization operations (e.g., training, equipment, and logistical support) through bilateral channels rather than U.N. mechanisms. In 2018, the three African members of the Security Council introduced a draft resolution that could have paved the way for the financing future AU-led operations through U.N. assessed contributions, under specific conditions. U.S. diplomats signaled concerns, including with regard to securing congressional support, and the draft resolution did not advance to a vote. |

African-led operations. How and whether to fund and sustain African-led regional stabilization operations in lieu of, or as a complement to, U.N. peacekeeping operations has been debated in U.N. fora, in Africa, and among U.S. policymakers. Stabilization operations initiated by the African Union (AU) or sub-regional organizations are often superseded by U.N. peacekeeping missions. While African regional organizations can authorize rapid military interventions, they are generally unable to finance or sustain them, and donor governments may be reluctant to fund them over long periods. AMISOM—established in 2007 and mandated to take offensive action in support of Somalia's federal government and against Islamist insurgents—has remained the sole African-led military intervention to benefit from a U.N. support operation funded through assessed contributions. At times, U.N. and AU officials, France (a permanent Security Council member), and African heads of state have proposed a similar mechanism for other regional missions (notably in the Sahel), but successive U.S. Administrations have declined to support such proposals, preferring to provide funding on a voluntary and bilateral basis.18 In recent years, the AU has sought the use of U.N. assessed contributions to help fund its operations directly (see text box).

Overview by Operation

The following sections provide background on each active U.N. peacekeeping operation in Africa, including U.S. policy and key issues. Operations are presented in reverse chronological order of their establishment by the U.N. Security Council (starting with most recently authorized).

Central African Republic (MINUSCA)

The Security Council established the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in CAR (MINUSCA) in 2014 in response to a spiraling conflict and humanitarian crisis in the country. The crisis began in 2013 when a largely Muslim-led rebel coalition seized control of the central government; largely Christian- and animist-led militias emerged in response and brutally targeted Muslim civilians, resulting in a pattern of killings and large-scale displacement that U.N. investigators later termed "ethnic cleansing."19 MINUSCA absorbed a preexisting African intervention force, as well as a U.N. political mission in CAR. Although CAR returned to elected civilian-led government in 2016, rebel groups continue to control most of the countryside. Armed factions have continued to kill and abuse civilians, often along sectarian and ethnic lines. Whether a peace accord signed in early 2019 will bring greater stability remains to be seen.

MINUSCA is currently mandated to protect civilians, support the extension of state authority, assist the peace process, and protect humanitarian aid delivery, among other tasks. It also has an unusual mandate to pursue "urgent temporary measures ... to arrest and detain in order to maintain basic law and order and fight impunity," under certain conditions.20 The mission has employed this authority against several militia leaders, with mixed effects on local security dynamics. Localized dynamics on the ground and a lack of domestic security force capacity also have stymied progress on stabilization. An analysis in late 2018 by nongovernment organizations attributed tenuous security improvements in parts of the country to MINUSCA's "robust military operations," as well as to its civilian-led support to local peacebuilding and disarmament efforts, while noting that "MINUSCA is neither authorized nor well-placed to use force with the objective of eliminating armed groups."21 In 2018, U.N. sanctions monitors issued a scathing assessment of a joint operation by MINUSCA and local security forces in the majority-Muslim "PK5" enclave of Bangui that aimed to dismantle a local militia. The sanctions monitors asserted that the operation had failed while also triggering intercommunal tensions and deadly clashes.22

Despite nearly reaching its full authorized troop ceiling, MINUSCA continues to exhibit operational capacity shortfalls, which the Security Council has attributed to "undeclared national caveats, lack of effective command and control, refusal to obey orders, failure to respond to attacks on civilians, and inadequate equipment."23 Force protection is a challenge: 35 MINUSCA personnel have been killed in "malicious acts" to date.24 (CAR is also one of the world's deadliest countries for aid workers.) Continued violence has fueled local frustrations with MINUSCA's perceived ineffectiveness—as has a sweeping sexual abuse scandal implicating multiple MINUSCA contingents, as well as French troops deployed under national command.25 Hostility has also been driven by government officials who oppose an enduring U.N. arms embargo on the country, as well as "demagogic" actors who seek to discredit international forces and destabilize the government.26 In April 2018, demonstrators placed 17 corpses outside MINUSCA headquarters to protest alleged killings of civilians during the aforementioned troubled joint operation with local security forces in the PK5 enclave.27

Despite initial skepticism, the Obama Administration ultimately supported MINUSCA's establishment as part of its efforts to prevent mass atrocities in CAR.28 The Trump Administration has maintained support to date, and in 2017 backed a troop ceiling increase of 900 military personnel. The State Department's FY2020 budget request projects that "the role and size of MINUSCA will likely remain unchanged until the government gains the capacity to fully assume its responsibilities to protect civilians, ensure the viability of the state, and prevent violence."

Mali (MINUSMA)

The Security Council established the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) in 2013 after state institutions collapsed in the face of an ethnic separatist rebellion in the north, a military coup, and an Islamist insurgent takeover of the north of the country.29 The mission absorbed a short-lived African intervention force and U.N. political mission. France also had launched a unilateral military intervention in early 2013 to free northern towns from Islamist militant control, and pressed for both the African-led mission and the transition to a U.N.-conducted operation. MINUSMA was initially mandated to support Mali's transitional authorities in stabilizing "key population centers," support the extension of state authority throughout the country, and prepare for elections, in addition to protecting civilians and U.N. personnel, promoting human rights, and protecting humanitarian aid, among other tasks. Civilian protection was elevated within the mandate in 2014, as was support for the launching of "an inclusive and credible negotiation process" for northern Mali, following a ceasefire between the government and separatist rebels and elections in late 2013. After the government and two northern armed group coalitions signed a peace accord in 2015, the Security Council deemed support for implementation of the accord to be the mission's top priority.

As of mid-2019, the peace agreement remains largely un-implemented, while the Islamist insurgency (excluded from the peace process by design) has expanded into previously government-controlled central Mali, as well as neighboring Burkina Faso and, to a lesser extent, Niger.30 Since 2017, observers have raised alarm over a spate of civilian massacres in the center, attributed to state security forces and to ethnically based militias (some of which appear to have ties to state elements), which may constitute "ethnic cleansing."31 Renewing MINUSMA's mandate in June 2019, the Security Council decided that the mission's "second strategic priority," after support for implementation of the 2015 accord, would be to "facilitate" a future Malian-led strategy to protect civilians, reduce intercommunal violence, and reestablish state authority in the center of the country, followed by other tasks (Resolution 2480).

Unlike most U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa, MINUSMA includes sizable Western contingents, including from Canada (134), Germany (381), the Netherlands (116), Norway (92), and Sweden (253).32 The countries contributing the largest uniformed contingents (>1,000 each), however, are nearby (Burkina Faso, Chad, Senegal, Togo) or major global peacekeeping troop contributors (Bangladesh, Egypt). MINUSMA is the world's deadliest current U.N. peacekeeping operation, with 126 personnel cumulatively killed in "malicious acts" (roughly 20 per year on average), including at least 20 in the first half of 2019.33 African contingents have borne the brunt of these fatalities (112 of 126 deaths).

In 2013, U.N. policy debates over MINUSMA's establishment centered on the wisdom of authorizing a peacekeeping mission in the context of threats from transnational Islamist terrorist organizations, namely, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and its local affiliates and offshoots. Policymakers debated, in particular, whether U.N. personnel would be adequately protected and whether a U.N. operation could or should be given a counterterrorism mandate.34 Ultimately, MINUSMA was not given an explicit mandate to conduct counterterrorism or counterinsurgency operations. France, meanwhile, has maintained troops in the country as a de facto parallel force to target terrorist cells, a mission for which the U.S. military provides direct logistical support.35

Malian and other African leaders (backed by France, at times) have repeatedly called for U.N. assessed contributions to provide funding and sustainment for a regional counterterrorism force, most recently the "G5 Sahel joint force" initiative launched by Mali and neighboring states in 2017. U.N. Secretary-General Guterres, for his part, has urged the Security Council to establish a U.N. support office, funded through assessed contributions and independent of MINUSMA, to provide logistics and sustainment to a G5 Sahel force.36 Successive U.S. Administrations have opposed such proposals, citing a preference for voluntary and bilateral support as opposed to assessed contributions.37

United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA)

UNISFA was authorized by the U.N. Security Council on the eve of South Sudan's independence in June 2011, in an effort to mitigate direct conflict between Sudan and South Sudan at a prominent disputed area on their border. The mission's mandate originally focused only on Abyei, a contested border territory and historic flashpoint for conflict that was accorded special semi-autonomous status in the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between Sudan's government and southern rebels. The mandate was expanded in late 2011 to support broader border security arrangements between the two countries, including a Joint Border Verification and Monitoring Mechanism (JBVMM), which the CPA signatories agreed to establish to monitor the full Sudan-South Sudan border. UNISFA's deployment to Abyei defused a violent standoff between the two countries' militaries, but tensions among local communities still have the potential to destabilize the border.

Under the CPA, the residents of Abyei were to vote in a referendum in 2011 on whether the area should retain its special status in Sudan or join South Sudan, but an officially sanctioned process has yet to occur.38 The final status of Abyei is likely to remain unresolved until Sudan and South Sudan negotiate a solution. The April 2019 ouster of Sudan's President Omar al Bashir and the unfolding political transition may affect the situation in Abyei and other border areas.

UNISFA was most recently reauthorized in May 2019, through November 15, 2019.39 The Security Council directed the mission to reduce its troop presence to 2,965 by October 2019 (from 4,140 previously authorized), while increasing the number of authorized police from 345 to 640. UNISFA's policing function to date has been hamstrung by Sudan's limited issuance of visas for police personnel. UNISFA is almost entirely composed of personnel from neighboring Ethiopia, based on a 2011 agreement between Sudan and South Sudan to demilitarize the area and allow Ethiopian monitors. There have been 36 UNISFA fatalities since 2011, with eight due to "malicious acts."40 The most recent peacekeeper fatality occurred in July 2019, when unidentified gunmen attacked a market.

The U.N. Security Council has pressed, unsuccessfully, for the establishment of a temporary local administration and police service to maintain order in Abyei until a final political settlement is reached. The absence of a local administration, combined with the presence of armed elements and sporadic intercommunal violence, continues to drive humanitarian needs. UNISFA helps to maintain law and order in the absence of local police, and it engages in efforts to reduce intercommunal conflict. UNISFA's presence and its conflict prevention and mitigation efforts have reportedly helped to defuse tensions during the annual migrations of an estimated 35,000 Misseriya (a nomadic group) and their cattle south through Abyei. The mission also confiscates and destroys weapons and facilitates mine clearance. UNISFA has yet to operationalize its human rights monitoring mandate because of Sudan's nonissuance of visas, and because its facilitation of humanitarian aid has been limited by Sudanese restrictions on aid agencies' operations, aid funding shortfalls, and South Sudan's war. With regard to UNISFA's border security role, Sudan and South Sudan took limited action to stand up the JBVMM in the mission's early years, but there has been recent progress, possibly reflecting warming relations between the two countries.

The United States, which served as a facilitator and guarantor of the CPA, has historically placed a high priority on peace between Sudan and what is now South Sudan. In mid-2011, when Sudanese troops and allied militia seized Abyei after its referendum was postponed, the Obama Administration declared the move to be an invasion of area and thus a violation of the CPA. The Security Council similarly condemned Sudan's "taking of military control" of Abyei and authorized UNISFA. Sudan's army subsequently withdrew as UNISFA deployed, and the mission's presence has since been seen as a deterrent to conflict between the two countries' forces. While relations between Sudan and South Sudan have improved in recent years, the instability in South Sudan and Sudan's Southern Kordofan state poses risks, and the political transition in Sudan creates further uncertainty regarding stability in the region. U.S. officials have previously expressed concern that the mission has continued longer than intended and that both Sudan and South Sudan have taken advantage of the relative stability its peacekeepers provide.41

U.N. Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS)

UNMISS was established on July 9, 2011, the date of South Sudan's independence from Sudan. It replaced the U.N. Mission in Sudan (UNMIS), which had supported implementation of the peace deal that ended Sudan's north-south civil war. UNMISS, currently authorized through March 2020, is currently the U.N.'s second largest peacekeeping mission (Figure 1).42

UNMISS was established with the aim of consolidating peace and security in the world's newest country, and helping to establish conditions for development after decades of war. The outbreak of a new internal conflict in December 2013, however, fundamentally changed the mission and its relationship with the host government.43 The war, now in its sixth year, has displaced more than 4 million people, and by some estimates over 380,000 people have been killed, including at least 190,000 in violent deaths.44 Shortly after the fighting began, the U.N. Security Council authorized an expansion of the mission from its prewar level of 7,000 troops and 900 police.45 Months later, as early mediation efforts failed to stop the conflict, the Security Council modified the UNMISS's mandate in Resolution 2155 (2014). As a result, the mandate changed from one that had supported peace-building, state-building, and the extension of state authority to one that sought strict impartiality in relations with both sides of the conflict, while pursuing four key tasks under a Chapter VII mandate: protecting civilians, monitoring and investigating human rights abuses, facilitating conditions conducive to aid delivery, and supporting a ceasefire monitoring.

The Security Council again increased UNMISS's force size after the warring sides signed a peace deal in August 2015, and added to its mandate the task of supporting implementation of the peace agreement. The opposing parties formed a new Transitional Government of National Unity (TGNU) in April 2016, but the arrangement collapsed in July 2016, and the war resumed. The Security Council, in an effort to create conditions under which the opposition could safely return to the capital and revive the peace deal, authorized another increase to UNMISS's troop ceiling, to include a Regional Protection Force (RPF), with up to 4,000 troops to be drawn from East African countries. The tasks of the RPF were to include, among others, providing a secure environment in and around the capital of Juba, with the ability to be deployed "in extremis" elsewhere as needed. South Sudan's government objected to the RPF's mandate and resisted its deployment; meanwhile, the war spread and the number of armed groups proliferated.

When the conflict began, UNMISS bases became shelters for tens of thousands of civilians fleeing the fighting and ethnically targeted attacks. As of September 2019, more than 180,000 people were still sheltering at five bases—also known as Protection of Civilian (POC) sites—including roughly 30,000 at the U.N. base in Juba.46 This is an unprecedented situation for a U.N. peacekeeping mission, and several of the sites, never intended for long-term settlements, feature living conditions that do not meet refugee camp standards.

UNMISS has struggled to protect civilians within and around the POC sites, and responsibility for security of those locations limits its ability to protect civilians and humanitarian workers elsewhere.47 Nevertheless, U.N. officials and others suggest that thousands of civilians would be dead if not for UNMISS.48 Many of those sheltering at the sites reportedly fear being targeted based on their ethnicity if they leave.49

Access restrictions and bureaucratic obstruction further stymie the mission's capacity.50 UNMISS relations with the government have been tense since the war began, and South Sudanese officials have periodically stoked anti-U.N. sentiment based on misperceptions of the mission's role and allegations of partiality.51 U.N. bases have been attacked on several occasions, and mortar and crossfire have resulted in the deaths of civilians and U.N. staff in the bases. To date, 14 peacekeepers have been killed in "malicious acts." Two U.N. helicopters have been shot down in South Sudan, at least one of them by the army. The role of government forces in violence against civilians severely complicates UNMISS's civilian protection mandate, given the mission's reliance on the consent of the host government to operate.

In September 2018, South Sudan's two largest warring factions—those of President Salva Kiir and his rival, Riek Machar—signed a new peace deal. Experts debate whether the deal is a viable framework for sustainable peace. The International Crisis Group (ICG) contends that, at minimum, "it is not a finished product and requires revision, a reality that mediators are not yet ready to admit."52 Implementation of the agreement is significantly behind schedule: the planned formation of a new unity government, delayed from May to November 2019, is in question as concerns about the accord's security arrangements remain unaddressed. The 2018 ceasefire has reduced the fighting in most parts of the country, but clashes continue in some areas, and U.N. reports document "the continued use of conflict-related sexual violence by the warring parties and "targeted" attacks on civilians, notably those "perceived to be associated with opposition groups."53 Amid mounting concerns that this latest deal could collapse, ICG (among others) argues that international pressure—including from the United States, which played a key role in supporting South Sudan's independence and is the "penholder" on the situation in the Security Council—may be critical to preventing a return to full-scale war.54

African Union-United Nations Mission in Darfur (UNAMID)

UNAMID was first authorized in 2007, to succeed the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS), which deployed in 2004 in response to the unfolding crisis in Darfur, an area roughly the size of France.55 When UNAMID was established, it was authorized to have a significantly larger force than AMIS—almost 26,000 personnel initially, including 19,555 troops—with a Chapter VII mandate to protect U.N. personnel, aid workers, and civilians, and to support implementation of a 2006 peace deal. The Security Council also tasked UNAMID with monitoring and conflict mitigation responsibilities. UNAMID is the first, and to date only, hybrid peacekeeping operation, with a U.N. chain of command but dual selection and reporting procedures. (Sudan rejected a regular U.N. mission; a U.N.-AU hybrid was the compromise, with most of the troops drawn from African countries.) By 2011, at almost 90% of its authorized strength, it was one of the largest peacekeeping missions in history.

UNAMID has faced pressures from multiple fronts, and has been described by some as "a mission that was set up to fail."56 The government of former President Omar al Bashir (ousted in April 2019) obstructed its operations and long pressed for its exit. Observers have periodically questioned the mission's credibility, amid allegations that it has self-censored reporting on state-backed crimes against civilians and peacekeepers and understated the level of ongoing violence.57 In 2009, a declaration by the outgoing head of UNAMID that the war in Darfur was over—while violence continued—drew concern from human rights groups and other observers.58 In 2013, the mission's spokesperson resigned, accusing UNAMID of a "conspiracy of silence"; a subsequent U.N. investigation found the mission had underreported and purposefully withheld information from U.N. headquarters concerning attacks by Sudanese forces on civilians and peacekeepers.

The Bashir government periodically denied flight clearances and restricted the movement of UNAMID patrols. Access denials, along with insecurity, have long impeded humanitarian operations, and some parts of Jebel Marra, a rebel stronghold, remain inaccessible. Bureaucratic delays, including in the issuance of visas, have also impeded operations. The mission has faced other challenges, ranging from shortfalls in critical equipment and aviation assets to a hostile environment. There have been over 270 UNAMID fatalities since the mission began, with 73 deaths attributed to "malicious acts." In 2013, the U.N. Panel of Experts suggested that the "lack of a deterrent" against attacks on peacekeepers and humanitarian aid workers "may be a contributing factor to the persistence of this phenomenon." Over the years, the panel has recommended, unsuccessfully, that several individuals and groups deemed responsible for attacks be sanctioned.59 The Security Council has made no sanctions designations since 2006. The United States has not designated individuals under its Darfur sanctions regime (E.O. 13400) since 2007.

The Security Council has reconfigured and gradually reduced UNAMID's mandate and mission since 2014, transferring some of its tasks to the U.N. country team. The country team's limited presence, capacity, and resources, however, have limited its ability to take on new responsibilities. Under pressure from Sudan's government for an exit strategy, the Security Council approved a reduction of troops in 2017, despite criticism from groups like Human Rights Watch that the cuts reflected a "false narrative about Darfur's war ending" (see below).60 Some independent experts suggest that the West suffers from "Darfur fatigue" and contend that flagging political will and pressure to cut peacekeeping budgets have driven decisions on UNAMID's exit, tentatively set under Resolution 2429 (2018) for June 30, 2020.61 Meanwhile, the Council has declared the mission's exit to be contingent on the security situation and progress on specified benchmarks.62

Over a decade after UNAMID's deployment, peace talks have not resolved Darfur's conflicts. The level of fighting subsided after a major government offensive in early 2016 gave the military dominance in the region.63 The government subsequently declared a ceasefire to which, per U.S. officials, it has largely adhered, contributing to the Administration's decision to lift some sanctions on Sudan in 2017.64 Recent U.N. reporting gives a mixed picture of the security situation. A joint U.N.-AU strategic review in 2018 concluded that Sudan's military gains since 2016 had led to the "consolidation of State authority across Darfur," with conditions now described as "lawlessness and criminality, aggravated by a protracted humanitarian crisis, continued human rights violations and the lack of development."65 A U.N. Secretary-General's report in April 2019 described the security situation in the region as "relatively stable," with the exception of Jebel Marra, where clashes continued and where a January 2019 U.N. Panel of Experts report suggested the government had waged large-scale military operations against rebels in 2018.66 Some rebels reportedly fled to Libya to rebuild their military capacity for possible return to Sudan.67 The Secretary-General's report also described serious intercommunal violence, attacks on civilians, and ongoing abuses by government forces as "an obstacle to lasting peace."68 The scale of displacement in Darfur has changed little in recent years: over 1.7 million people remain internally displaced, most of them in camps, and over 340,000 refugees are in Chad.69

In the wake of President Bashir's overthrow in April 2019, a joint U.N.-AU assessment team noted a spike in violence in several camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs). Their report suggested, though, that Darfur had generally "evolved into a post-conflict setting."70 The team submitted that the new political dynamics did not warrant a change of the June 2020 exit date and that conditions had been met for the drawdown to proceed, albeit gradually, with the mission transitioning from peacekeeping to peacebuilding.

Several incidents suggest security conditions for U.N. and aid operations in Darfur worsened in mid-2019, however. In May, UNAMID's West Darfur headquarters was looted on the eve of its scheduled handover to Sudanese authorities; military and police personnel were implicated in the incident. In June, humanitarian relief facilities in South Darfur were looted and vandalized. The United Nations has reported that most of the facilities that UNAMID has closed as part of its drawdown have been occupied by state security forces. (The sites were supposed to be handed over to the government to be used for civilian purposes.) An internal UNAMID review of 10 closed sites indicated that nine were being used specifically by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which have been implicated in human rights abuses.71 In June, the military leaders who seized power from Bashir demanded that remaining UNAMID bases be transferred to the RSF. The AU rejected the order, which was subsequently reversed. It is unclear whether the RSF has vacated the locations.

U.N. human rights officials reported in June 2019 that the human rights situation in Darfur had deteriorated, with increased reports of killing, abduction, sexual violence, and other abuses.72 The AU Peace and Security Council determined at that time that the "drastic change on security and political developments … has contributed to the deterioration of the security situation in Darfur," and called for remaining peacekeepers to be consolidated until the situation stabilized.73 Amnesty International, which has argued against UNAMID's closure, suggests doing so would "recklessly and needlessly place tens of thousands of lives at risk by removing their only safeguard against the government's scorched earth campaign."74 On June 27, the U.N. Security Council voted to pause the drawdown until October 31, with roughly 4,200 troops and 2,300 police remaining in Darfur as of July 31.

It is difficult to predict how the situation in Darfur may evolve in the next year, as UNAMID's prescribed June 2020 exit date approaches. Arguably the most powerful figure among the security officials who seized power from Bashir is RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, aka "Hemeti," a former Janjaweed militia leader from Darfur.75 By some accounts, his forces have sought to expand their control in Darfur, and since Bashir's ouster they have been implicated in the killing of dozens of Darfuri civilians. He now holds a senior position in the new transitional government, and how he may influence the prospects for peace is subject to debate.76 Sudan's new reform-oriented prime minister has identified making peace with the country's insurgent groups as his top priority. As that process begins, in the context of a fragile transition, Sudanese, U.N., and AU officials are set to begin discussions on the future of U.N. peacekeepers in Darfur, and on whether a follow-on mechanism to UNAMID may be appropriate.77

Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO)

The currently largest U.N. peacekeeping operation originated as a response to the civil and regional conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in the late 1990s. In 2010, the Security Council established the U.N. Organization Stabilization Mission in DRC (MONUSCO) to succeed the U.N. Organization Mission in DRC (MONUC, established in 1999), following the conclusion of a formal post-conflict transitional period in DRC. MONUSCO's mandate has generally prioritized the protection of civilians and the extension of state authority in eastern DRC, where multiple armed groups remain active. Other enduring tasks include the protection of U.N. personnel and facilities, support for demobilization of rebel combatants, and support for institutional and security sector reforms. Since 2018, MONUSCO has provided "life-saving logistics support to the Ebola response" in the context of the ongoing Ebola outbreak in eastern DRC, according to U.S. officials.78 In mid-2019, a top MONUSCO official, U.S. citizen David Gressly, became the U.N. Emergency Ebola Response Coordinator, tasked with leading a "strengthened coordination and support mechanism in the epicenter" of the outbreak zone.79

Since 2013, the Security Council has authorized an "intervention brigade" within MONUSCO—consisting of three infantry battalions, one artillery company, and one special force and reconnaissance company—to disarm rebel groups, including via unilateral and/or offensive operations. The intervention brigade has conducted such operations periodically, but the scope of its activity has been limited by troop contributors' evolving perceptions of their own national security interests in DRC, as well as capacity gaps. Observers have debated whether the concept could be a model for other situations, such as South Sudan and Mali.

More broadly, human rights groups allege that MONUSCO forces have repeatedly failed to protect civilians from attacks by armed groups. Such instances may be attributed to multiple factors, including competing tasks, logistical challenges, a lack of capacity and political will among troop contributors, and the role of state actors in violence and their limited commitment to improve stability. MONUSCO personnel also have repeatedly been implicated in sexual abuse and exploitation. Between 2016 and 2018, a surge in political violence in major cities due to election delays placed new strains on the mission, as did the emergence of new conflicts in previously stable regions.80 Emergent, if nebulous, links between an opaque armed group in eastern DRC and the Islamic State organization may present further challenges.81

In 2015 and 2016, the Obama Administration successfully sought to preserve MONUSCO's troop ceiling in the lead-up to DRC's turbulent election period, despite pressure from the DRC government, U.N. officials, and some other Security Council members to decrease troop levels. In 2017, with elections pending, the Trump Administration shifted tack and secured a decrease in MONUSCO's troop ceiling, asserting that the mission was propping up a "corrupt" government in Kinshasa.82 The U.N. Secretary-General reported in 2017 that MONUSCO had pursued reforms to "yield efficiencies," but called for governments to "exercise caution in making further cuts to the Mission's budget that may compromise its ability to deliver on its core priorities."83

U.S. diplomats did not openly pursue, and the Security Council did not adopt, a troop ceiling decrease in the 2018 or 2019 mandate renewals. In March 2019, as DRC underwent a partial political transition following the delayed elections, the Security Council extended MONUSCO's mandate and troop ceiling for nine months and called for an independent strategic review of the mission, including the articulation of an "exit strategy." 84 The State Department's FY2020 budget request asserts that MONUSCO forces "may begin drawing down in FY2020 as the DRC government assumes greater responsibility for security throughout the country." The budget request predated an explosion of Ebola cases in eastern DRC and the U.N.'s stepped-up role in response efforts. U.N. budget negotiations in mid-2019 produced a significant reduction in MONUSCO's civilian personnel and the closure of offices in various areas.85

Western Sahara (MINURSO)

Morocco claims sovereignty over the whole of Western Sahara and administers some 85% of it, while the Polisario Front, which is hosted and backed by Algeria, seeks independence for the territory. Security Council Resolution 690 established the U.N. Mission for the Organization of a Referendum in the Western Sahara (MINURSO) in 1991 in the context of a cease-fire and peace settlement roadmap agreed to by Morocco and the Polisario.86 At the time of MINURSO's establishment, the Security Council called for a referendum to offer Sahrawis—the indigenous inhabitants of Western Sahara—a path to "self-determination." However, successive U.N. efforts to advance a referendum or other resolution options did not obtain the backing of one or both parties (Morocco and the Polisario), and/or of the Security Council.

In the absence of a final settlement, the Security Council has maintained MINURSO to observe the 1991 ceasefire. The Security Council has not explicitly referred to a referendum in over a decade, instead calling for Morocco and the Polisario to engage in talks "without preconditions" to achieve a "mutually acceptable" resolution to the stand-off. Morocco has offered autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty as the only basis for negotiations, while the Polisario continues to call for a referendum on independence. Neither side has shown an interest in compromise. Military tensions escalated in 2016 and again in 2017 as Moroccan and Polisario forces reportedly entered the demilitarized "buffer zone."

MINURSO's uniformed component consists almost entirely of military observers, who are unarmed. It is not a multidimensional mission in the mold of more recently authorized operations. In 2013, U.S. diplomats reportedly expressed support for adding human rights monitoring to the mission's mandate—which Morocco ardently opposes—prompting Morocco to expel hundreds of U.S. military personnel who were conducting an annual joint exercise in the country. In 2016, Morocco expelled MINURSO civilian staff in response to remarks by then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon referring to Morocco's "occupation" of the territory. Some staff, but not all, later returned to the territory.

Successive U.S. Administrations appear to have judged that maintaining MINURSO is a relatively small price to pay for preventing a renewed conflict that could draw in other countries in the region. The Trump Administration has maintained support for U.N.-facilitated talks, while also seeking to increase pressure on the parties by shortening MINURSO's mandate renewals from one year to six months.87 This policy approach was closely associated with former National Security Advisor John Bolton, who has long expressed skepticism of MINURSO and advocated international pressure on Morocco to make concessions.88 Bolton's stance appeared to contribute to some momentum toward U.N.-facilitated talks in 2018, albeit without clear progress toward a settlement. The U.N. Secretary-General's then-Personal Envoy on the Western Sahara, Horst Köhler, convened "roundtable" talks among Morocco, the Polisario, Algeria, and Mauritania in December 2018—the first time official representatives of Morocco and the Polisario had met since 2012—and again in March 2019, but no breakthrough was announced. In May 2019, Köhler unexpectedly announced his resignation, citing health reasons. This development, combined with ongoing political instability in Algeria, has injected new uncertainty into the political process.

Issues for Congress

Members of Congress have examined U.N. peacekeeping operations as a core element of U.S.-Africa policy, and in the context of overarching appropriations and oversight activities. Congressional deliberations on FY2020 SFOPS appropriations—in the context of the Administration's proposal to cut U.S. funding for U.N. peacekeeping overall, and for the Africa missions in particular—have coincided with U.N. Security Council consideration of potentially significant changes to the mandates of several missions, including in Mali, Darfur (Sudan), and DRC, due to evolving conditions on the ground. The Senate Appropriations Committee report on the FY2020 Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Bill (released on September 18, 2019), leads with the observation that:

Weak governance and conflict in Africa, the Middle East, and Central and South America are causing historically unprecedented population movements as refugees and internally displaced persons [IDPs] seek safer lives. […] The humanitarian requirements of the United Nations [UN] and other entities to address this global emergency have consistently exceeded the willingness and generosity of donors to respond.

As Congress continues to shape the U.S. approach toward peacekeeping missions' mandates and budgets, it may consider issues such as:

- how and whether U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa align with U.S. foreign policy priorities in the region and in individual countries;

- the impact that decisions on U.S. funding for peacekeeping may have on these countries, and the relative cost of other potential U.S. responses; and

- the role of other donors and actors in responding to security crises in Africa.