Introduction

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) authorizes—and in some cases requires—the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to detain non-U.S. nationals (aliens) arrested for immigration violations that render them removable from the United States.1 The immigration detention regime serves two primary purposes. First, detention may ensure an apprehended alien's presence at his or her removal hearing and, if the alien is ultimately ordered removed, makes it easier for removal to be quickly effectuated.2 Second, in some cases detention may serve the additional purpose of alleviating any threat posed by the alien to the safety of the community while the removal process is under way.3

The INA's detention framework, however, is multifaceted, with different rules turning on whether the alien is seeking initial admission into the United States or was lawfully admitted into the country; whether the alien has committed certain criminal offenses or other conduct rendering him or her a security risk; and whether the alien is being held pending removal proceedings or has been issued a final order of removal.4

In many cases detention is discretionary, and DHS may release an alien placed in formal removal proceedings on bond, on his or her own recognizance, or under an order of supervision pending the outcome of those proceedings.5 But in other instances, such as those involving aliens who have committed specified crimes, there are only limited circumstances when the alien may be released from custody.6

This report outlines the statutory and regulatory framework governing the detention of aliens, from an alien's initial arrest and placement in removal proceedings to the alien's removal from the United States. In particular, the report examines the key statutory provisions that specify when an alien may or must be detained by immigration authorities and the circumstances when an alien may be released from custody. The report also discusses the various legal challenges to DHS's detention power and some of the judicially imposed restrictions on that authority. Finally, the report examines how these legal developments may inform Congress as it considers legislation that may modify the immigration detention framework.

Legal and Historical Background

The Federal Immigration Authority and the Power to Detain Aliens

The Supreme Court has long recognized that the federal government has "broad, undoubted power over the subject of immigration and the status of aliens,"7 including with respect to their admission, exclusion, and removal from the United States.8 This authority includes the power to detain aliens pending determinations as to whether they should be removed from the country.9 The Court has predicated this broad immigration power on the government's inherent sovereign authority to control its borders and its relations with foreign nations.10 Notably, the Court has "repeatedly emphasized that 'over no conceivable subject is the legislative power of Congress more complete than it is over' the admission of aliens,"11 and that "Congress may make rules as to aliens that would be unacceptable if applied to citizens."12

Despite the government's broad immigration power, the Supreme Court has repeatedly declared that aliens who have physically entered the United States come under the protective scope of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, which applies "to all 'persons' within the United States, including aliens, whether their presence here is lawful, unlawful, temporary, or permanent."13 Due process protections generally include the right to a hearing and a meaningful opportunity to be heard before deprivation of a liberty interest.14 And one of the core protections of the Due Process Clause is the "[f]reedom from bodily restraint."15 But while the Supreme Court has recognized that due process considerations may constrain the federal government's exercise of its immigration power, there is some uncertainty regarding when these considerations may be consequential.

Generally, aliens seeking initial entry into the United States typically have more limited constitutional protections than aliens present within the country.16 The Supreme Court has long held that aliens seeking entry into the United States have no constitutional rights regarding their applications for admission,17 and the government's detention authority in those situations seems least constrained by due process considerations. Thus, in Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei, the Supreme Court upheld the indefinite detention of an alien who was denied admission into the United States following a trip abroad.18 The Court ruled that the alien's "temporary harborage" on Ellis Island pending the government's attempts to remove him did not constitute an "entry" into the United States, and that he could be "treated as if stopped at the border."19

Nevertheless, some courts have suggested that the constitutional limitations that apply to arriving aliens pertain only to their procedural rights regarding their applications for admission, but do not foreclose the availability of redress when fundamental liberty interests are implicated.20 Thus, some lower courts have concluded that arriving aliens have sufficient due process protections against unreasonably prolonged detention, and distinguished Mezei as a case involving the exclusion of an alien who potentially posed a danger to national security that warranted the alien's detention.21 Furthermore, regardless of the extent of their due process protections, detained arriving aliens may be entitled to at least some level of habeas corpus review, in which courts consider whether an individual is lawfully detained by the government.22

But due process considerations become more significant once an alien has physically entered the United States. As discussed above, the Supreme Court has long recognized that aliens who have entered the United States, even unlawfully, are "persons" under the Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause.23 That said, the Court has also suggested that "the nature of that protection may vary depending upon [the alien's] status and circumstance."24 In various opinions, the Court has suggested that at least some of the constitutional protections to which an alien is entitled may turn upon whether the alien has been admitted into the United States or developed substantial ties to this country.25

Consequently, the government's authority to detain aliens who have entered the United States is not absolute. The Supreme Court, for instance, construed a statute authorizing the detention of aliens ordered removed to have implicit temporal limitations because construing it to allow the indefinite detention of aliens ordered removed—at least in the case of lawfully admitted aliens later ordered removed—would raise "serious constitutional concerns."26 Declaring that the government's immigration power "is subject to important constitutional limitations," the Court has determined that the Due Process Clause limits the detention to "a period reasonably necessary to secure removal."27

Additionally, while the Supreme Court has recognized the government's authority to detain aliens pending formal removal proceedings,28 the Court has not decided whether the extended detention of aliens during those proceedings could give rise to a violation of due process protections.29 But some lower courts have concluded that due process restricts the government's ability to indefinitely detain at least some categories of aliens pending determinations as to whether they should be removed from the United States.30

In sum, although the government has broad power over immigration, there are constitutional constraints on that power. These constraints may be most significant with regard to the detention of lawfully admitted aliens within the country, and least powerful with regard to aliens at the threshold of initial entry into the United States.

Development of Immigration Laws Concerning Detention

From the outset, U.S. federal immigration laws have generally authorized the detention of aliens who are subject to removal. The first U.S. law on alien detention was the Alien Enemies Act in 1798, which subjected certain aliens from "hostile" nations during times of war to being detained and removed.31 But Congress passed no other laws on the detention of aliens for nearly a century.32 Starting in 1875, however, Congress enacted a series of laws restricting the entry of certain classes of aliens (e.g., those with criminal convictions), and requiring the detention of aliens who were excludable under those laws until they could be removed.33 In construing the government's detention authority, the Supreme Court in 1896 declared that "[w]e think it clear that detention or temporary confinement, as part of the means necessary to give effect to the provisions for the exclusion or expulsion of aliens, would be valid."34 Over the next few decades, Congress continued to enact laws generally mandating the detention and exclusion of proscribed categories of aliens seeking entry into the United States, as well as aliens physically present in the United States who became subject to removal.35

In 1952, Congress passed the INA, which distinguished between aliens physically arriving in the United States and those who had entered the country.36 Aliens arriving in the country who were found ineligible for entry were subject to "exclusion," and those already present in the United States who were found to be subject to expulsion were deemed "deportable."37 For aliens placed in exclusion proceedings, detention generally was required,38 unless immigration authorities, based on humanitarian concerns, granted the alien "parole," allowing the alien to enter and remain in the United States pending a determination on whether he or she should be admitted.39 In the case of deportable aliens, detention originally was authorized but not required, and aliens in such proceedings could be released on bond or "conditional parole."40 Congress later amended the INA to require, in deportation proceedings, the detention of aliens convicted of aggravated felonies,41 and authorized their release from custody only in limited circumstances, such as when the alien was a lawful permanent resident (LPR) who did not pose a threat to the community or a flight risk.42

In 1996, Congress enacted the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which made sweeping changes to the federal immigration laws.43 IIRIRA replaced the INA's exclusion/deportation framework, which turned on whether an alien had physically entered the United States, with a new framework that turned on whether an alien had been lawfully admitted into the country by immigration authorities.44 Aliens who had not been admitted, including those who may have unlawfully entered the country, could be barred entry or removed from the country based on specified grounds of inadmissibility listed under INA Section 212.45 Aliens who had been lawfully admitted, however, could be removed if they fell under grounds of deportability specified under INA Section 237.46 A standard, "formal" removal proceeding was established for deportable aliens and most categories of inadmissible aliens.47 But IIRIRA created a new "expedited removal" process that applied to a subset of inadmissible aliens.48 This process applies to arriving aliens and certain aliens who recently entered the United States without inspection, when those aliens lack valid entry documents or attempted to procure their admission through fraud or misrepresentation.49

IIRIRA generally authorized (but did not require) immigration authorities to detain aliens believed to be removable pending those aliens' formal removal proceedings, but permitted their release on bond or "conditional parole."50 IIRIRA, however, required the detention of aliens who were inadmissible or deportable based on the commission of certain enumerated crimes or for terrorist-related grounds, generally with no possibility of release from custody.51 IIRIRA also generally required the detention of "applicants for admission," including aliens subject to expedited removal, pending determinations as to whether they should be removed (such aliens, however, could still be paroled into the United States by immigration officials in their discretion).52 This mandatory detention requirement has been applied even if those aliens were subsequently transferred to formal removal proceedings.53 Finally, IIRIRA created a detention scheme in which aliens with final orders of removal became subject to detention during a 90-day period pending their removal, and the government could (but was not required to) continue to detain some of those aliens after that period.54

A table showing the development of these immigration detention laws can be found in Table A-1.

Modern Statutory Detention Framework

Since IIRIRA's enactment, the statutory framework governing detention has largely remained constant.55 This detention framework is multifaceted, with different rules turning on whether the alien is seeking admission into the United States or was lawfully admitted within the country; whether the alien has committed certain enumerated criminal or terrorist acts; and whether the alien has been issued a final administrative order of removal. Four provisions largely govern the current immigration detention scheme:

- 1. INA Section 236(a) generally authorizes the detention of aliens pending formal removal proceedings and permits (but does not require) aliens who are not subject to mandatory detention to be released on bond or their own recognizance;56

- 2. INA Section 236(c) generally requires the detention of aliens who are removable because of specified criminal activity or terrorist-related grounds;57

- 3. INA Section 235(b) generally requires the detention of applicants for admission (e.g., aliens arriving at a designated port of entry) who appear subject to removal;58 and

- 4. INA Section 241(a) generally mandates the detention of aliens during a 90-day period after formal removal proceedings, and authorizes (but does not require) the continued detention of certain aliens after that period.59

While these statutes apply to distinct classes of aliens at different phases of the removal process, the statutory detention framework "is not static," and DHS's detention authority "shifts as the alien moves through different phases of administrative and judicial review."60

This section explores these detention statutes and their implementing regulations, including administrative and judicial rulings that inform their scope and application. (Other detention provisions in the INA that apply to small subsets of non-U.S. nationals, such as alien crewmen, or arriving aliens inadmissible for health-related reasons, are not addressed in this report.61)

A table providing a comparison of these major INA detention statutes can be found in Table A-2.

Discretionary Detention Under INA Section 236(a)

INA Section 236(a) is the "default rule" for aliens placed in removal proceedings.62 The statute is primarily administered by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the agency within DHS largely responsible for immigration enforcement in the interior of the United States.63 Section 236(a) authorizes immigration authorities to arrest and detain an alien pending his or her formal removal proceedings.64 Detention under INA Section 236(a) is discretionary, and immigration authorities are not required to detain an alien subject to removal unless the alien falls within one of the categories of aliens subject to mandatory detention (e.g., aliens convicted of specified crimes under INA Section 236(c), discussed later in this report).65

If ICE arrests and detains an alien under INA Section 236(a), and the alien is not otherwise subject to mandatory detention, the agency has two options:

- 1. it "may continue to detain the arrested alien" pending the removal proceedings; or

- 2. it "may release the alien" on bond in the amount of at least $1500, or on "conditional parole."66

Generally, upon release (whether on bond or conditional parole), the alien may not receive work authorization unless the alien is otherwise eligible (e.g., the alien is an LPR).67 And ICE may at any time revoke a bond or conditional parole and bring the alien back into custody.68

In the event of an alien's release, ICE may opt to enroll the alien in an Alternatives to Detention (ATD) program, which allows ICE the ability to monitor and supervise the released alien to ensure his or her eventual appearance at a removal proceeding.69

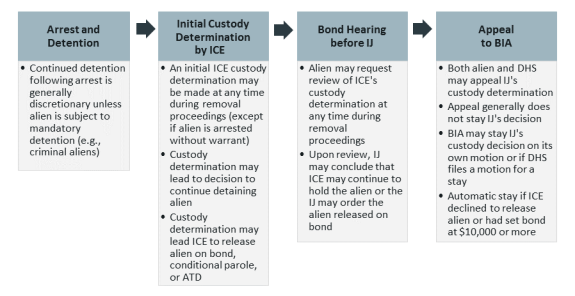

Initial Custody Determination and Administrative Review

Following the arrest of an alien not subject to mandatory detention, an immigration officer may, at any time during formal removal proceedings, determine whether the alien should remain in custody or be released.70 But when an alien is arrested without a warrant, DHS regulations provide that the immigration officer must make a custody determination within 48 hours of the alien's arrest, unless there is "an emergency or other extraordinary circumstance" that requires "an additional reasonable period of time" to make the custody determination.71 DHS has defined "emergency or other extraordinary circumstance" to mean a "significant infrastructure or logistical disruption" (e.g., natural disaster, power outage, serious civil disturbance); an "influx of large numbers of detained aliens that overwhelms agency resources"; and other unique facts and circumstances "including, but not limited to, the need for medical care or a particularized compelling law enforcement need."72

After ICE's initial custody determination, an alien may, at any time during the removal proceedings, request review of that decision at a bond hearing before an immigration judge (IJ) within the Department of Justice's (DOJ's) Executive Office for Immigration Review.73 While the alien may request a bond hearing, INA Section 236(a) does not require a hearing to be provided at any particular time.74 If there is a bond hearing, regulations specify that it "shall be separate and apart from, and shall form no part of, any deportation or removal hearing or proceeding."75 During these bond proceedings, the IJ may, under INA Section 236(a), determine whether to keep the alien in custody or release the alien, and the IJ also has authority to set the bond amount.76 Following the IJ's custody decision, the alien may obtain a later bond redetermination only "upon a showing that the alien's circumstances have changed materially since the prior bond redetermination."77

Both the alien and DHS may appeal the IJ's custody or bond determination to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), the highest administrative body charged with interpreting federal immigration laws.78 The filing of an appeal generally will not stay the IJ's decision or otherwise affect the ongoing removal proceedings.79 The BIA, however, may stay the IJ's custody determination on its own motion or when DHS appeals that decision and files a motion for a discretionary stay.80 Moreover, if ICE had determined that the alien should not be released or had set bond at $10,000 or greater, any order of the IJ authorizing release (on bond or otherwise) is automatically stayed upon DHS's filing of a notice of intent to appeal with the immigration court within one business day of the IJ's order, and the IJ's order will typically remain held in abeyance pending the BIA's decision on appeal.81

Standard and Criteria for Making Custody Determinations

Following the enactment of IIRIRA, the DOJ promulgated regulations to govern discretionary detention and release decisions under INA Section 236(a).82 These regulations require the alien to "demonstrate to the satisfaction of the officer that . . . release would not pose a danger to property or persons, and that the alien is likely to appear for any future proceeding."83 Based on this regulation, the BIA has held that the alien has the burden of showing that he or she should be released from custody, and "[o]nly if an alien demonstrates that he does not pose a danger to the community should an [IJ] continue to a determination regarding the extent of flight risk posed by the alien."84

Some federal courts, however, have held that if an alien's detention under INA Section 236(a) becomes prolonged, a bond hearing must be held where the burden shifts to the government to prove that the alien's continued detention is warranted.85 For example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (Ninth Circuit86) has reasoned that, given an individual's "substantial liberty interest" in avoiding physical restraint, the government should prove by clear and convincing evidence that the detention is justified.87 The Supreme Court has not yet addressed the proper allocation of the burden of proof for custody determinations under INA Section 236(a). On the one hand, the Court has held that the statute does not itself require the government to prove that an alien's continued detention is warranted or to afford the alien a bond hearing.88 On the other hand, the Court has not decided whether due process considerations nonetheless compel the government to bear the burden of proving that the alien should remain in custody if detention becomes prolonged.89

While INA Section 236(a) and its implementing regulations provide standards for determining whether an alien should be released from ICE custody, they do not specify the factors that may be considered in weighing a detained alien's potential danger or flight risk.90 But the BIA has instructed that an IJ may consider, among other factors, these criteria in assessing an alien's custody status:

- whether the alien has a fixed address in the United States;

- the alien's length of residence in the United States;

- whether the alien has family ties in the United States;

- the alien's employment history;

- the alien's record of appearance in court;

- the alien's criminal record, including the extent, recency, and seriousness of the criminal offenses;

- the alien's history of immigration violations;

- any attempts by the alien to flee prosecution or otherwise escape from authorities; and

- the alien's manner of entry to the United States.91

The BIA and other authorities have generally applied these criteria in reviewing custody determinations.92 In considering an alien's danger to the community or flight risk, "any evidence in the record that is probative and specific can be considered."93 The BIA has also instructed that, in deciding whether an alien presents a danger to the community and should not be released from custody, an IJ should consider both direct and circumstantial evidence of dangerousness, including whether the facts and circumstances raise national security considerations.94 In addition, although bond proceedings are "separate and apart from" formal removal proceedings,95 evidence obtained during a removal hearing "may be considered during a custody hearing so long as it is made part of the bond record."96

Limitations to Administrative Review of Custody Determinations

Under DOJ regulations, an IJ may not determine the conditions of custody for classes of aliens subject to mandatory detention.97 In these circumstances, ICE retains exclusive authority over the alien's custody status.98 These limitations apply to

- arriving aliens in formal removal proceedings (including arriving aliens paroled into the United States);

- aliens in formal removal proceedings who are deportable on certain security and related grounds (e.g., violating espionage laws, criminal activity that "endangers public safety or national security," terrorist activities, severe violations of religious freedom); and

- aliens in formal removal proceedings who are subject to mandatory detention under INA Section 236(c) based on the commission of certain enumerated crimes.99

Although aliens who fall within these categories may not request a custody determination before an IJ, they may still seek a redetermination of custody conditions from ICE.100 In addition, aliens detained under INA Section 236(c) based on criminal or terrorist-related conduct may request a determination by an IJ that they do not properly fall within that designated category, and that they are thus entitled to a bond hearing.101

Judicial Review of Custody Determinations

An alien may generally request review of ICE's custody determination at a bond hearing before an IJ, and the alien may also appeal the IJ's custody decision to the BIA.102 INA Section 236(e), however, expressly bars judicial review of a decision whether to detain or release an alien who is subject to removal:

The Attorney General's discretionary judgment regarding the application of this section shall not be subject to review. No court may set aside any action or decision by the Attorney General under this section regarding the detention or release of any alien or the grant, revocation, or denial of bond or parole.103

Even so, the Supreme Court has determined that, absent clear congressional intent, INA provisions barring judicial review do not foreclose the availability of review in habeas corpus proceedings because "[i]n the immigration context, 'judicial review' and 'habeas corpus' have historically different meanings."104 Thus, despite INA Section 236(e)'s limitation on judicial review, the Court has held that the statute does not bar federal courts from reviewing, in habeas corpus proceedings, an alien's statutory or constitutional challenge to his detention.105 The Court has reasoned that an alien's challenge to "the statutory framework" permitting his detention is distinct from a challenge to the "discretionary judgment" or operational "decision" whether to detain the alien, which is foreclosed from judicial review under INA Section 236(e).106 Lower courts have similarly held that they retain jurisdiction to review habeas claims that raise constitutional or statutory challenges to detention.107 For that reason, although a detained alien may not seek judicial review of the government's discretionary decision whether to keep him or her detained, the alien may challenge the legal authority for that detention under the federal habeas statute.108

The Supreme Court has also considered whether a separate statute, INA Section 242(b)(9), bars judicial review of detention challenges.109 That statute provides:

Judicial review of all questions of law and fact, including interpretation and application of constitutional and statutory provisions, arising from any action taken or proceeding brought to remove an alien from the United States under this subchapter shall be available only in judicial review of a final order [of removal] under this section.110

The Court has construed INA Section 242(b)(9) as barring review of three specific actions (except as part of the review of a final order of removal): (1) an order of removal, (2) the government's decision to seek removal (including the decision to detain the alien), and (3) the process by which an alien's removability would be determined.111 But the Court has declined to read the statute as barring all claims that could technically "arise from" one of those three actions.112 Thus, the Court has held that INA Section 242(b)(9) does not bar review of claims challenging the government's authority to detain aliens because such claims do not purport to challenge an order of removal, the government's decision to seek removal, or the process by which an alien's removability is determined.113

Mandatory Detention of Criminal Aliens Under INA Section 236(c)

While INA Section 236(a) generally authorizes immigration officials to detain aliens pending their formal removal proceedings, INA Section 236(c) requires the detention of aliens who are subject to removal because of specified criminal or terrorist-related grounds.114

Aliens Subject to Detention Under INA Section 236(c)

INA Section 236(c)(1) covers aliens who fall within one of four categories:

- 1. An alien who is inadmissible under INA Section 212(a)(2) based on the commission of certain enumerated crimes, including a crime involving moral turpitude, a controlled substance violation, a drug trafficking offense, a human trafficking offense, money laundering, and any two or more criminal offenses resulting in a conviction for which the total term of imprisonment is at least five years.

- 2. An alien who is deportable under INA Section 237(a)(2) based on the conviction of certain enumerated crimes, including an aggravated felony, two or more crimes involving moral turpitude not arising out of a single scheme of criminal misconduct, a controlled substance violation (other than a single offense involving possession of 30 grams or less of marijuana), and a firearm offense.

- 3. An alien who is deportable under INA Section 237(a)(2)(A)(i) based on the conviction of a crime involving moral turpitude (generally committed within five years of admission) for which the alien was sentenced to at least one year of imprisonment.

- 4. An alien who is inadmissible or deportable for engaging in terrorist activity, being a representative or member of a terrorist organization, being associated with a terrorist organization, or espousing or inciting terrorist activity.115

The statute instructs that ICE "shall take into custody any alien" who falls within one of these categories "when the alien is released [from criminal custody], without regard to whether the alien is released on parole, supervised release, or probation, and without regard to whether the alien may be arrested or imprisoned again for the same offense."116

Prohibition on Release from Custody Except in Special Circumstances

While INA Section 236(c)(1) requires ICE to detain aliens who are removable on enumerated criminal or terrorist-related grounds, INA Section 236(c)(2) provides that ICE "may release an alien described in paragraph (1) only if" the alien's release "is necessary to provide protection to a witness, a potential witness, a person cooperating with an investigation into major criminal activity, or an immediate family member or close associate of a witness, potential witness, or person cooperating with such an investigation," and the alien shows that he or she "will not pose a danger to the safety of other persons or of property and is likely to appear for any scheduled proceeding."117 Under the statute, "[a] decision relating to such release shall take place in accordance with a procedure that considers the severity of the offense committed by the alien."118

Without these special circumstances, an alien detained under INA Section 236(c) generally must remain in custody pending his or her removal proceedings.119 Furthermore, given the mandatory nature of the detention, the alien may not be released on bond or conditional parole, or request a custody redetermination at a bond hearing before an IJ.120

Limited Review to Determine Whether Alien Falls Within Scope of INA Section 236(c)

Although an alien detained under INA Section 236(c) has no right to a bond hearing before an IJ, DOJ regulations allow the alien to seek an IJ's determination "that the alien is not properly included" within the category of aliens subject to mandatory detention under INA Section 236(c).121 The BIA has determined that, during this review, the IJ should conduct an independent assessment, rather than a "perfunctory review," of DHS's decision to charge the alien with one of the specified criminal or terrorist-related grounds of removability under INA Section 236(c).122 According to the BIA, the alien is not "properly included" within the scope of INA Section 236(c) if the IJ concludes that DHS "is substantially unlikely to establish at the merits hearing, or on appeal, the charge or charges that would otherwise subject the alien to mandatory detention."123 If the IJ determines that the alien is not properly included within INA Section 236(c), the IJ may then consider whether the alien is eligible for bond under INA Section 236(a).124

Constitutionality of Mandatory Detention

The mandatory detention requirements of INA Section 236(c) have been challenged as unconstitutional but, to date, none of these challenges have succeeded.125 In Demore v. Kim, an LPR (Kim) who had been detained under INA Section 236(c) for six months argued that his detention violated his right to due process because immigration authorities had made no determination that he was a danger to society or a flight risk.126 The Ninth Circuit upheld a federal district court's ruling that INA Section 236(c) was unconstitutional.127 The Ninth Circuit determined that INA Section 236(c) violated Kim's right to due process as an LPR because it afforded him no opportunity to seek bail.128

The Supreme Court reversed the Ninth Circuit's decision, holding that mandatory detention of certain aliens pending removal proceedings was "constitutionally permissible."129 The Court noted that it had previously "endorsed the proposition that Congress may make rules as to aliens that would be unacceptable if applied to citizens," and the Court also cited its "longstanding view that the Government may constitutionally detain deportable aliens during the limited period necessary for their removal proceedings, . . ."130 The Court concluded that "Congress, justifiably concerned that deportable criminal aliens who are not detained continue to engage in crime and fail to appear for their removal hearings in large numbers, may require that persons such as [Kim] be detained for the brief period necessary for their removal proceedings."131

The Court also distinguished its 2001 decision in Zadvydas v. Davis, where it declared that "serious constitutional concerns" would be raised if lawfully admitted aliens were indefinitely detained after removal proceedings against them had been completed.132 The Court reasoned that, unlike the post-order of removal detention statute at issue in Zadvydas, INA Section 236(c) "governs detention of deportable criminal aliens pending their removal proceedings," and thus "serves the purpose of preventing deportable criminal aliens from fleeing prior to or during their removal proceedings, . . ."133 Yet in Zadvydas, removal was "no longer practically attainable" for the detained aliens following the completion of their proceedings, and so their continued detention "did not serve its purported immigration purpose."134 The Court further distinguished Zadvydas because that case involved a potentially indefinite period of detention, while detention under INA Section 236(c) typically lasts for a "much shorter duration" and has a "definite termination point"—the end of the removal proceedings.135

Although the Supreme Court in Demore ruled that mandatory detention pending removal proceedings is not unconstitutional per se, the Court did not address whether there are any constitutional limits to the duration of such detention under INA Section 236(c).136 Some lower courts, however, have construed Demore to apply only to relatively brief periods of detention.137 Ultimately, in Jennings v. Rodriguez, the Supreme Court held that DHS has the statutory authority to indefinitely detain aliens pending their removal proceedings, but did not decide whether such prolonged detention is constitutionally permissible.138

Meaning of "When the Alien Is Released"

INA Section 236(c)(1) instructs that ICE "shall take into custody any alien" who falls within one of the enumerated criminal or terrorist-related grounds "when the alien is released" from criminal custody.139 And under INA Section 236(c)(2), ICE may not release "an alien described in paragraph (1)" except for witness protection purposes.140

In its 2019 decision in Nielsen v. Preap, the Supreme Court held that INA Section 236(c)'s mandatory detention scheme covers any alien who has committed one of the enumerated criminal or terrorist-related offenses, no matter when the alien had been released from criminal incarceration.141 The Court observed that INA Section 236(c)(2)'s mandate against release applies to "an alien described in paragraph (1)" of that statute, and that INA Section 236(c)(1), in turn, describes aliens who have committed one of the enumerated crimes.142 The Court determined that, although INA Section 236(c)(1) instructs that such aliens be taken into custody "when the alien is released," the phrase "when . . . released" does not describe the alien, and "plays no role in identifying for the [DHS] Secretary which aliens she must immediately arrest."143 The Court thus held that the scope of aliens subject to mandatory detention under INA Section 236(c) "is fixed by the predicate offenses identified" in INA Section 236(c)(1), no matter when the alien was released from criminal custody.144

The Court also opined that, even if INA Section 236(c) requires an alien to be detained immediately upon release from criminal custody, ICE's failure to act promptly would not bar the agency from detaining the alien without bond.145 The Court relied, in part, on its 1990 decision in United States v. Montalvo-Murillo, which held that the failure to provide a criminal defendant a prompt bond hearing as required by federal statute did not mandate the defendant's release from criminal custody.146 Citing Montalvo-Murillo, the Court in Preap recognized the principle that if a statute fails to specify a penalty for the government's noncompliance with a statutory deadline, the courts will not "'impose their own coercive sanction.'"147 In short, the Court declared, "it is hard to believe that Congress made [ICE's] mandatory detention authority vanish at the stroke of midnight after an alien's release" from criminal custody.148

The Court thus reversed a Ninth Circuit decision that had restricted the application of INA Section 236(c) to aliens detained "promptly" upon their release from criminal custody, but noted that its ruling on the proper interpretation of INA Section 236(c) "does not foreclose as-applied challenges—that is, constitutional challenges to applications of the statute as we have now read it."149

In sum, based on the Court's ruling in Preap, INA Section 236(c) authorizes ICE to detain covered aliens without bond pending their formal removal proceedings, regardless of whether they were taken into ICE custody immediately or long after their release from criminal incarceration. That said, the Court has left open the question of whether the mandatory detention of aliens long after their release from criminal custody is constitutionally permissible.

Mandatory Detention of Applicants for Admission Under INA Section 235(b)

The INA provides for the mandatory detention of aliens who are seeking initial entry into the United States, or who have entered the United States without inspection, and who are believed to be subject to removal. Under INA Section 235(b), an "applicant for admission," defined to include both an alien arriving at a designated port of entry and an alien present in the United States who has not been admitted,150 is generally detained pending a determination about whether the alien should be admitted into the United States.151 The statute thus covers aliens arriving at the U.S. border (or its functional equivalent), as well as aliens who had entered the United States without inspection, and are later apprehended within the country.152

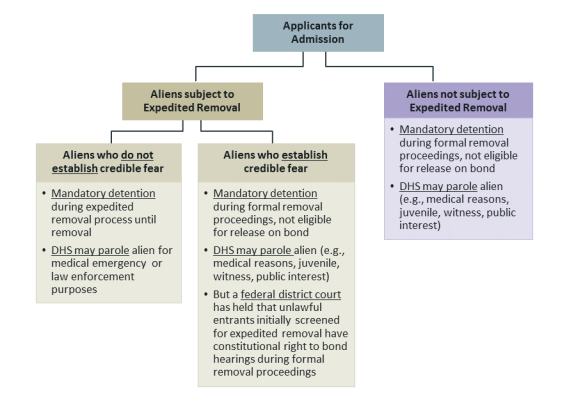

The statute's mandatory detention scheme covers (1) applicants for admission who are subject to a streamlined removal process known as "expedited removal" and (2) applicants for admission who are not subject to expedited removal, and who are placed in formal removal proceedings.153

Applicants for Admission Subject to Expedited Removal

INA Section 235(b)(1) provides for the expedited removal of arriving aliens who are inadmissible under INA Section 212(a)(6)(C) or (a)(7) because they lack valid entry documents or have attempted to procure admission by fraud or misrepresentation.154 The statute also authorizes the Secretary of Homeland Security to expand the use of expedited removal to aliens present in the United States without being admitted or paroled if they have been in the country less than two years and are inadmissible on the same grounds.155 Based on this authority, DHS has employed expedited removal mainly to (1) arriving aliens; (2) aliens who arrived in the United States by sea within the last two years, who have not been admitted or paroled by immigration authorities; and (3) aliens found in the United States within 100 miles of the border within 14 days of entering the country, who have not been admitted or paroled by immigration authorities.156 More recently, however, DHS has expanded the use of expedited removal to aliens who have not been admitted or paroled, and who have been in the United States for less than two years (a legal challenge to this expansion is pending at the time of this report's publication).157

Generally, an alien subject to expedited removal may be removed without a hearing or further review unless the alien indicates an intention to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution if removed to a particular country.158 If the alien indicates an intention to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution, he or she will typically be referred to an asylum officer within DHS's U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)159 to determine whether the alien has a "credible fear" of persecution or torture.160 If the alien establishes a credible fear, he or she will be placed in "formal" removal proceedings under INA Section 240, and may pursue asylum and related protections.161

Detention During Expedited Removal Proceedings

INA Section 235(b)(1) and DHS regulations provide that an alien "shall be detained" pending a determination on whether the alien is subject to expedited removal, including during any credible fear determination; and if the alien is found not to have a credible fear of persecution or torture, the alien will remain detained until his or her removal.162 Typically, the alien will be initially detained by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) for no more than 72 hours for processing (e.g., fingerprints, photographs, initial screening), and the alien will then be transferred to ICE custody pending a credible fear determination if the alien is subject to expedited removal and requests asylum or expresses a fear of persecution.163

Under INA Section 212(d)(5), however, DHS may parole an applicant for admission (which includes an alien subject to expedited removal) on a case-by-case basis "for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit."164 Based on this authority, DHS has issued regulations that allow parole of an alien in expedited removal proceedings, but only when parole "is required to meet a medical emergency or is necessary for a legitimate law enforcement objective."165

Aliens Who Establish a Credible Fear of Persecution or Torture

INA Section 235(b)(1) provides that aliens who establish a credible fear of persecution or torture "shall be detained for further consideration of the application for asylum" in formal removal proceedings.166 The alien will typically remain in ICE custody during those proceedings.167 As noted above, DHS retains the authority to parole applicants for admission, and typically will interview the alien to determine his or her eligibility for parole within seven days after the credible fear finding.168 Under DHS regulations, the following categories of aliens may be eligible for parole, provided they do not present a security or flight risk:

- persons with serious medical conditions;

- women who have been medically certified as pregnant;

- juveniles (defined as individuals under the age of 18) who can be released to a relative or nonrelative sponsor;

- persons who will be witnesses in proceedings conducted by judicial, administrative, or legislative bodies in the United States; and

- persons "whose continued detention is not in the public interest."169

Under DHS regulations, a grant of parole ends upon the alien's departure from the United States, or, if the alien has not departed, at the expiration of the time for which parole was authorized.170 Parole may also be terminated upon accomplishment of the purpose for which parole was authorized or when DHS determines that "neither humanitarian reasons nor public benefit warrants the continued presence of the alien in the United States."171

For some time, the BIA took the view that aliens apprehended after unlawfully entering the United States (i.e., not apprehended at a port of entry), and who were first screened for expedited removal but then placed in formal removal proceedings following a positive credible fear determination, were not subject to mandatory detention under INA Section 235(b)(1).172 Instead, the BIA determined, these aliens could be released on bond under INA Section 236(a) because, unlike arriving aliens, they did not fall within the designated classes of aliens who are ineligible for bond hearings under DOJ regulations.173 Thus, the BIA concluded, INA Section 235(b)(1)'s mandatory detention scheme "applie[d] only to arriving aliens."174

In 2019, Attorney General (AG) William Barr overturned the BIA's decision and ruled that INA Section 235(b)(1)'s mandatory detention scheme applies to all aliens placed in formal removal proceedings after a positive credible fear determination, regardless of their manner of entry.175 The AG reasoned that INA Section 235(b)(1) plainly mandates that aliens first screened for expedited removal who establish a credible fear "shall be detained" until completion of their formal removal proceedings, and that the INA only authorizes their release on parole.176 The AG also relied on the Supreme Court's 2018 decision in Jennings v. Rodriguez, which construed INA Section 235(b) as mandating the detention of covered aliens unless they are paroled.177 Finally, the AG concluded, even though nonarriving aliens subject to expedited removal are not expressly barred from seeking bond under DOJ regulations, that regulatory framework "does not provide an exhaustive catalogue of the classes of aliens who are ineligible for bond."178

In a later class action lawsuit, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington ruled that INA Section 235(b)(1)'s mandatory detention scheme is unconstitutional, and that aliens apprehended within the United States who are first screened for expedited removal and placed in formal removal proceedings following a positive credible fear determination are "constitutionally entitled to a bond hearing before a neutral decisionmaker" pending consideration of their asylum claims.179 The court thus ordered the government to (1) provide bond hearings within seven days of a bond hearing request by detained aliens who entered the United States without inspection, were first screened for expedited removal, and were placed in formal removal proceedings after a positive credible fear determination; (2) release any aliens within that class whose detention time exceeds that seven-day limit and who did not have a bond hearing; and (3) if a bond hearing is held, require DHS to prove that continued detention is warranted to retain custody of the alien.180

The DOJ has appealed the district court's ruling to the Ninth Circuit.181 The Ninth Circuit has stayed the lower court's injunction pending appeal insofar as it requires the government to hold bond hearings within seven days, to release aliens whose detention time exceeds that limit, and to require DHS to have the burden of proof.182 But the court declined to stay the lower court's order that aliens apprehended within the United States who are initially screened for expedited removal, and placed in formal removal proceedings after a positive credible fear determination, are "constitutionally entitled to a bond hearing."183 Thus, the Ninth Circuit's order "leaves the pre-existing framework in place" in which unlawful entrants transferred to formal removal proceedings after a positive credible fear determination were eligible for bond hearings.184

As a result of the district court's ruling, aliens apprehended within the United States who are initially screened for expedited removal and transferred to formal removal proceedings following a positive credible fear determination remain eligible to seek bond pending their formal removal proceedings. On the other hand, arriving aliens who are transferred to formal removal proceedings are not covered by the court's order,185 and generally must remain detained pending those proceedings, unless DHS grants parole.186

Applicants for Admission Who Are Not Subject to Expedited Removal

INA Section 235(b)(2) covers applicants for admission who are not subject to expedited removal.187 This provision would thus cover, for example, unadmitted aliens who are inadmissible on grounds other than those described in INA Section 212(a)(6)(C) and (a)(7) (e.g., because the alien is deemed likely to become a public charge, or the alien has committed specified crimes).188 The statute would also cover aliens who had entered the United States without inspection, but who are not subject to expedited removal because they were not apprehended within two years after their arrival in the country.189

The INA provides that aliens covered by INA Section 235(b)(2) "shall be detained" pending formal removal proceedings before an IJ.190 As discussed above, however, DHS may parole applicants for admission pending their removal proceedings, and agency regulations specify circumstances in which parole may be warranted (e.g., where detention "is not in the public interest").191 Absent parole, aliens covered by INA Section 235(b)(2) generally must be detained and cannot seek their release on bond.192

|

|

Sources: 8 U.S.C. §§ 1182(d)(5)(A), 1225(b)(1)(B)(ii), (iii)(IV), 1225(b)(2(A); 8 C.F.R. §§ 212.5(b), 235.3(b)(2)(iii), (3), (4)(ii), (5)(i), 235.3(c); Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S. Ct. 830 (2018); Padilla v. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 387 F. Supp. 3d 1219 (W.D. Wash. 2019). |

Detention of Aliens Following Completion of Removal Proceedings Under INA Section 241(a)

INA Section 241(a) governs the detention of aliens after the completion of removal proceedings.193 The statute's detention authority covers two categories of aliens: (1) aliens with a final order of removal who are subject to detention during a 90-day "removal period" pending efforts to secure their removal; and (2) certain aliens who may (but are not required to) be detained beyond the 90-day removal period.194 The Supreme Court has construed the post-order of removal detention statute as having implicit temporal limitations.195

Detention During 90-Day Removal Period

INA Section 241(a)(1) provides that DHS "shall remove" an alien ordered removed "within a period of 90 days," and refers to this 90-day period as the "removal period."196 The statute specifies that the removal period "begins on the latest of the following":197

- The date the order of removal becomes administratively final.198

- If the alien petitions for review of the order of removal,199 and a court orders a stay of removal, the date of the court's final order in the case.200

- If the alien is detained or confined for nonimmigration purposes (e.g., criminal incarceration), the date the alien is released from that detention or confinement.201

INA Section 241(a)(2) instructs that DHS "shall detain" an alien during the 90-day removal period.202 The statute also instructs that "[u]nder no circumstance during the removal period" may DHS release an alien found inadmissible on criminal or terrorist-related grounds under INA Section 212(a)(2) or (a)(3)(B) (e.g., a crime involving moral turpitude); or who has been found deportable on criminal or terrorist-related grounds under INA Section 237(a)(2) or (a)(4)(B) (e.g., an aggravated felony conviction).203

The former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) previously issued guidance interpreting these provisions as only authorizing, but not requiring, the detention of "non-criminal aliens" during the 90-day removal period.204 There is no indication that DHS has rescinded that policy. But according to the agency, the statute generally requires the detention during the removal period of terrorists and aliens who have committed the specified crimes enumerated in the statute.205 Under this policy, however, if a criminal alien subject to mandatory detention has been granted withholding of removal or protection under the Convention Against Torture (CAT), the alien may be released if the agency is not pursuing the alien's removal.206

While INA Section 241(a)(1) specifies a 90-day removal period, it also provides that this period may be extended beyond 90 days and that the alien may remain in detention during this extended period "if the alien fails or refuses to make timely application in good faith for travel or other documents necessary to the alien's departure or conspires or acts to prevent the alien's removal subject to an order of removal."207

INA Section 241(a)(3) provides that, if the alien either "does not leave or is not removed within the removal period," the alien will be released and "subject to supervision" pending his or her removal.208 DHS regulations state that the order of supervision must specify the conditions of release, including requirements that the alien (1) periodically report to an immigration officer and provide relevant information under oath; (2) continue efforts to obtain a travel document and help DHS obtain the document; (3) report as directed for a mental or physical examination; (4) obtain advance approval of travel beyond previously specified times and distances; and (5) provide ICE with written notice of any change of address.209

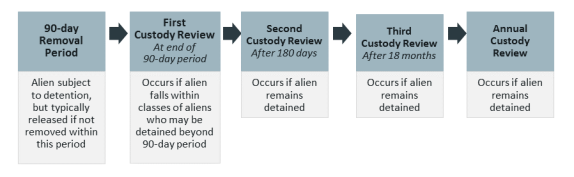

Continued Detention Beyond Removal Period

Typically, an alien with a final order of removal is subject to detention during the 90-day removal period, and must be released under an order of supervision if the alien does not leave or is not removed within that period.210 INA Section 241(a)(6), however, states that an alien "may be detained beyond the removal period"211 if the alien falls within one of three categories:

- 1. an alien ordered removed who is inadmissible under INA Section 212(a) (e.g., an arriving alien who lacks valid entry documents);

- 2. an alien ordered removed who is deportable under INA Sections 237(a)(1)(C) (failure to maintain or comply with conditions of nonimmigrant status), 237(a)(2) (specified crimes including crimes involving moral turpitude, aggravated felonies, and controlled substance offenses), or 237(a)(4) (security and terrorist-related grounds); or

- 3. an alien whom DHS has determined "to be a risk to the community or unlikely to comply with the order of removal."212

DHS regulations provide that, before the end of the 90-day removal period, ICE will conduct a "custody review" for a detained alien who falls within one of the above categories, and whose removal "cannot be accomplished during the period, or is impracticable or contrary to the public interest," to determine whether further detention is warranted after the removal period ends.213 The regulations list factors that ICE should consider in deciding whether to continue detention, including the alien's disciplinary record, criminal record, mental health reports, evidence of rehabilitation, history of flight, prior immigration history, family ties in the United States, and any other information probative of the alien's danger to the community or flight risk.214

ICE may release the alien after the removal period ends if the agency concludes that travel documents for the alien are unavailable (or that removal "is otherwise not practicable or not in the public interest"); the alien is "a non-violent person" and likely will not endanger the community; the alien likely will not violate any conditions of release; and the alien does not pose a significant flight risk.215 Upon the alien's release, ICE may impose certain conditions, including (but not limited to) those specified for the release of aliens during the 90-day removal period, such as periodic reporting requirements.216

If ICE decides to maintain custody of the alien, it may retain custody authority for up to three months after the expiration of the 90-day removal period (i.e., up to 180 days after final order of removal).217 At the end of that three-month period, ICE may either release the alien if he or she has not been removed (in accordance with the factors and criteria for supervised release), or refer the alien to its Headquarters Post-Order Detention Unit (HQPDU) for further custody review.218 If the alien remains in custody after that review, the HQPDU must conduct another review within one year (i.e., 18 months after final order of removal), and (if the alien is still detained) annually thereafter.219

|

Figure 3. General Procedure for Post-Order of Removal Detention |

|

|

Sources: 8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(2), (3), (6); 8 C.F.R. §§ 241.3(a), 241.4(a), (c)(1), (c)(2), (h)(1), (i)(1), (k)(1), (k)(2). |

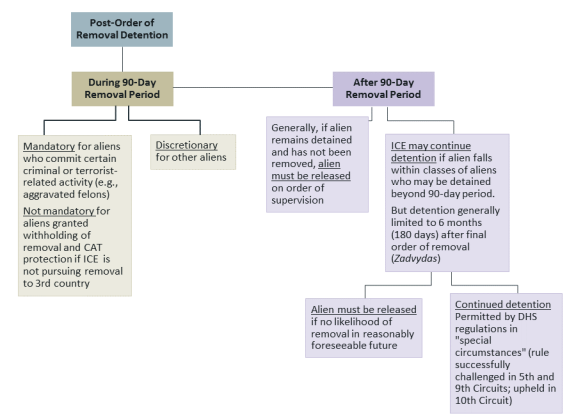

Constitutional Limitations to Post-Order of Removal Detention

Although INA Section 241(a) authorizes (and in some cases requires) DHS to detain an alien after removal proceedings, the agency's post-order of removal detention authority has been subject to legal challenge, particularly when the alien remained detained indefinitely pending efforts to secure his or her removal to another country.220 Eventually, in Zadvydas v. Davis, a case involving the prolonged detention of lawfully admitted aliens who had been ordered removed, the Supreme Court interpreted the statute consistently with due process principles to limit detention generally to a six-month period after a final order of removal.221

In Zadvydas, the Supreme Court considered whether INA Section 241(a)'s post-order of removal detention statute should be construed as having an implicit time limitation to avoid serious constitutional concerns.222 The Court determined that "[a] statute permitting indefinite detention of an alien would raise a serious constitutional problem" under the Due Process Clause.223 The Court reasoned that "[f]reedom from imprisonment—from government custody, detention, or other forms of physical restraint—lies at the heart of the liberty that Clause protects," and found no justifications for the indefinite detention of aliens whose removal is no longer practicable.224 While the Court recognized that a potentially indefinite detention scheme may be upheld if it is "limited to specially dangerous individuals and subject to strong procedural protections,"225 INA Section 241(a)(6)'s post-removal period detention scheme was different because it applied "broadly to aliens ordered removed for many and various reasons, including tourist visa violations."226 The Court thus concluded that the statute could not be lawfully construed as authorizing indefinite detention.227

Notably, the Court rejected the government's contention that indefinite detention pending removal was constitutionally permissible under Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei, which, many decades earlier, had upheld the indefinite detention on Ellis Island of an alien denied admission into the United States and ordered excluded.228 The Zadvydas Court distinguished Mezei, which involved an alien considered at the threshold of entry, because "once an alien enters the country, the legal circumstance changes, for the Due Process Clause applies to all 'persons' within the United States, including aliens, whether their presence here is lawful, unlawful, temporary, or permanent."229

The Zadvydas Court determined there was no indication that Congress had intended to confer immigration authorities with the power to indefinitely confine individuals ordered removed.230 Although INA Section 241(a)(6) states that an alien "may be detained" after the 90-day removal period, the Court reasoned, the statute's use of the word "may" is ambiguous and "does not necessarily suggest unlimited discretion."231

For these reasons, applying the doctrine of constitutional avoidance,232 the Court held that INA Section 241(a)(6) should be construed as authorizing detention only for "a period reasonably necessary to secure removal."233 The Court thus construed the statute as having an implicit temporal limitation of six months following a final order of removal.234 If that six-month period elapses, the Court held, the alien generally must be released from custody if he "provides good reason to believe that there is no significant likelihood of removal in the reasonably foreseeable future."235

In Clark v. Martinez, the Supreme Court considered whether the presumptive six-month time limitation established in Zadvydas applied to aliens who had not been lawfully admitted into the United States, and who were being detained after their 90-day removal periods had lapsed.236 The Court concluded that the time limitation read into INA Section 241(a)(6) for deportable aliens in Zadvydas equally applied to inadmissible aliens. But unlike in Zadvydas, the Court did not rest its decision on matters of constitutional avoidance. Instead, the majority opinion (written by Justice Scalia, who had dissented in Zadvydas), relied on the principle of statutory construction that a provision should have the same meaning in different circumstances.237 "[B]ecause the statutory text provides for no distinction between admitted and nonadmitted aliens," the Martinez Court reasoned, the provision should be interpreted as having the same, presumptive six-month time limit for both categories of aliens.238

In reaching this conclusion, the Supreme Court rejected the government's invitation to construe the detention statute differently when applied to unadmitted aliens, which the government contended was proper because of the limited constitutional protections available to such aliens.239 The majority stated that "[b]e that as it may, it cannot justify giving the same detention provision a different meaning when such aliens are involved."240

Post-Zadvydas Regulations Addressing Likelihood of Removal and Special Circumstances Warranting Continued Detention

Following the Supreme Court's decision in Zadvydas, the former INS issued regulations that established "special review procedures" for aliens who remain detained beyond the 90-day removal period.241 Under these rules, an alien may "at any time after a removal order becomes final" submit a written request for release because there is no significant likelihood of removal in the reasonably foreseeable future.242 The HQPDU will consider the alien's request and issue a decision on the likelihood of the alien's removal.243 Generally, if the HQPDU determines that there is no significant likelihood of removal, ICE will release the alien subject to any appropriate conditions.244 But if the HQPDU concludes that there is a significant likelihood of the alien's removal in the reasonably foreseeable future, the alien will remain detained pending removal.245

The regulations provide, however, that even if the HQPDU concludes that there is no significant likelihood of the alien's removal in the reasonably foreseeable future, the alien may remain detained if "special circumstances" are present.246 The regulations list four categories of aliens whose continued detention may be warranted because of special circumstances: (1) aliens with "a highly contagious disease that is a threat to public safety"; (2) aliens whose release "is likely to have serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States"; (3) aliens whose release "presents a significant threat to the national security or a significant risk of terrorism"; and (4) aliens whose release "would pose a special danger to the public."247

Some courts, though, have ruled that the former INS exceeded its authority by issuing regulations allowing the continued detention of aliens in "special circumstances." Both the Fifth and Ninth Circuits have concluded that the Supreme Court in Zadvydas never created an exception for the indefinite detention post-order of removal of aliens considered particularly dangerous.248 Instead, these courts concluded, the Supreme Court had merely suggested that it might be within Congress's power to enact a law allowing for the prolonged detention of certain types of aliens following an order of removal, not that Congress had done so when it enacted INA Section 241(a)(6), which does not limit its detention authority to "specific and narrowly defined groups."249 The Tenth Circuit, on the other hand, has ruled that the former INS's interpretation of the statute to permit indefinite detention in special circumstances was reasonable.250 The Supreme Court has not yet considered whether INA Section 241(a)(6) authorizes indefinite post-order of removal detention in special circumstances.

|

|

Sources: 8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(2), (3), (6); 8 C.F.R. §§ 241.3(a), 241.4(a), 241.13, 241.14; Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678 (2001); Clark v. Martinez, 543 U.S. 371 (2005); Hernandez-Carrera v. Carlson, 547 F.3d 1237 (10th Cir. 2008); Tran v. Mukasey, 515 F.3d 478 (5th Cir. 2008); Tuan Thai v. Ashcroft, 366 F.3d 790 (9th Cir. 2004); Continued Detention of Aliens Subject to Final Orders of Removal, 66 Fed. Reg. 56,967 (Nov. 14, 2001); Memorandum from Bo Cooper, Gen. Counsel, Immigration & Naturalization Serv., to Reg'l Counsel for Distribution to District and Sector Counsel: Detention and Release during the Removal Period of Aliens Granted Withholding or Deferral of Removal (Apr. 21, 2000). |

Select Legal Issues Concerning Detention

As the above discussion reflects, DHS has broad authority to detain aliens who are subject to removal, and for certain classes of aliens (e.g., those with specified criminal convictions) detention is mandatory with no possibility of release except in limited circumstances.251 Further, while the Supreme Court has recognized limits to DHS's ability to detain aliens after removal proceedings, the Court has recognized that the governing INA provisions appear to allow the agency to detain aliens potentially indefinitely pending those proceedings.252

But some have argued that the prolonged detention of aliens during their removal proceedings without bond hearings is unconstitutional.253 Moreover, the government's ability to detain alien minors, including those accompanied by adults in family units, is currently limited by a binding settlement agreement known as the Flores Settlement, which generally requires the release of minors in immigration custody.254 Apart from concerns raised by prolonged detention, there has been criticism over the lack of regulations governing the conditions of confinement.255 Additionally, for aliens detained by criminal law enforcement authorities, DHS's authority to take custody of such aliens for immigration enforcement purposes through "immigration detainers" has been subject to legal challenge.256 The following sections provide more discussion of these developing issues.

Indefinite Detention During Removal Proceedings

In Zadvydas v. Davis, discussed above, the Supreme Court in 2001 ruled that the indefinite detention of aliens after the completion of removal proceedings raised "a serious constitutional problem," at least for those who were lawfully admitted, and thus construed INA Section 241(a)(6)'s post-order of removal detention provision as containing an implicit six-month time limitation.257 In 2003, the Court in Demore v. Kim held that the mandatory detention of aliens pending removal proceedings under INA Section 236(c) was "constitutionally permissible," but did not decide whether there were any constitutional limits to the duration of such detention.258 Later, though, some lower courts ruled that the prolonged detention of aliens pending removal proceedings raised similar constitutional issues as those raised after a final order, and, citing Zadvydas, construed INA Section 236(c) as containing an implicit temporal limitation.259 In 2018, the Supreme Court held in Jennings v. Rodriguez that the government has the statutory authority to indefinitely detain aliens pending their removal proceedings, but left the constitutional questions unresolved.260

The Jennings case involved a class action by aliens within the Central District of California who had been detained under INA Sections 235(b), 236(c), and 236(a), in many cases for more than a year.261 The plaintiffs claimed that their prolonged detention without a bond hearing violated their due process rights.262 In 2015, the Ninth Circuit upheld a permanent injunction requiring DHS to provide aliens detained longer than six months under INA Sections 235(b), 236(c), and 236(a) with individualized bond hearings.263 The court expressed concern that the detention statutes, if construed to permit the indefinite detention of aliens pending removal proceedings, would raise "constitutional concerns" given the reasoning of the Supreme Court in Zadvydas.264 Although the Supreme Court in Demore had upheld DHS's authority to detain aliens without bond pending removal proceedings, the Ninth Circuit construed Demore's holding as limited to the constitutionality of "brief periods" of detention, rather than cases when the alien's detention lasts for extended periods.265

Recognizing the constitutional limits placed on the federal government's authority to detain individuals, the Ninth Circuit, as a matter of constitutional avoidance, ruled that the INA's detention statutes should be construed as containing implicit time limitations.266 The court therefore interpreted the mandatory detention provisions of INA Sections 235(b) and 236(c) to expire after six months' detention, after which the government's detention authority shifts to INA Section 236(a) and the alien must be given a bond hearing.267 The court also construed INA Section 236(a) as requiring bond hearings every six months.268 In addition, the court held that continued detention after an initial six-month period was permitted only if DHS proved by clear and convincing evidence that further detention was warranted.269

In Jennings, the Supreme Court rejected as "implausible" the Ninth Circuit's construction of the challenged detention statutes.270 The Court determined that the Ninth Circuit could not rely on the constitutional avoidance doctrine to justify its interpretation of the statutes.271 The Court distinguished Zadvydas, which the Ninth Circuit had relied on when invoking the constitutional avoidance doctrine, because the post-order of removal detention statute at issue in that case did not clearly provide that an alien's detention after the 90-day removal period was required.272 According to the Jennings Court, the statute at issue in Zadvydas was sufficiently open to differing interpretations that reliance on the constitutional avoidance doctrine was permissible.273 But the Jennings Court differentiated the ambiguity of that detention statute from INA Sections 235(b) and 236(c), which the Court held were textually clear in generally requiring the detention of covered aliens until the completion of removal proceedings.274 And the Court also observed that nothing in INA Section 236(a) required bond hearings after an alien was detained under that authority, or required the government to prove that the alien's continued detention was warranted after an initial six-month period.275 According to the Court, the Ninth Circuit could not construe the statutes to require bond hearings simply to avoid ruling on whether they passed constitutional muster.276 Having rejected the Ninth Circuit's interpretation of INA Sections 235(b), 236(a), and 236(c) as erroneous, the Court remanded the case to the lower court to address, in the first instance, the plaintiffs' constitutional claim that their indefinite detention under these provisions violated their due process rights.277

In short, the Jennings Court held that the government has the statutory authority to detain aliens potentially indefinitely pending their removal proceedings, but did not decide whether such indefinite detention is unconstitutional. While the Supreme Court has not yet addressed the constitutionality of indefinite detention during removal proceedings, the Court had indicated in Demore v. Kim that aliens may be "detained for the brief period necessary for their removal proceedings."278 And in a concurring opinion in Demore, Justice Kennedy declared that a detained alien "could be entitled to an individualized determination as to his risk of flight and dangerousness if the continued detention became unreasonable or unjustified."279

After the Jennings decision, some lower courts have concluded that the detention of aliens during removal proceedings without a bond hearing violates due process if the detention is unreasonably prolonged.280 Some courts have applied these constitutional limitations to the detention of aliens arriving in the United States who are placed in removal proceedings, reasoning that, although such aliens typically have lesser constitutional protections than aliens within the United States, they have sufficient due process rights to challenge their prolonged detention.281 In reaching this conclusion, some courts have addressed the Supreme Court's 1953 decision in Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei, which upheld the detention without bond of an alien seeking entry into the United States.282 These courts determined that Mezei is distinguishable because, in that case, the alien had already been ordered excluded when he challenged his detention, and the alien potentially posed a danger to national security that warranted his confinement.283

In addition, while the Jennings Court held that INA Section 236(a) does not mandate that a clear and convincing evidence burden be placed on the government in bond hearings, some courts have concluded that the Constitution requires placing the burden of proof on the government in those proceedings.284

At some point, whether in the Jennings litigation or another case, the Supreme Court may decide whether the indefinite detention of aliens pending removal proceedings is constitutionally permissible. In doing so, the Court may also reassess the scope of constitutional protections for arriving aliens seeking initial entry into the United States. The Court may also decide whether due process compels the government to prove that an alien's continued detention is justified at a bond hearing. The Court's resolution of these questions may clarify its view on the federal government's detention authority.

Detention of Alien Minors

As discussed, DHS has broad authority to detain aliens pending their removal proceedings, and in some cases detention is mandatory except in certain limited circumstances. But a 1997 court settlement agreement (the "Flores Settlement") currently limits the period in which an alien minor (i.e., under the age of 18) may be detained by DHS.285 Furthermore, under federal statute, an unaccompanied alien child (UAC) who is subject to removal is generally placed in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), rather than DHS, pending his or her removal proceedings.286 In 2019, DHS promulgated a final rule that purports to incorporate these limitations with some modifications.287

The Flores Settlement originates from a 1985 class action lawsuit brought by a group of UACs apprehended at or near the border, who challenged the conditions of their detention and release.288 The parties later settled the plaintiffs' claims regarding the conditions of their detention, but the plaintiffs maintained a challenge to the INS's policy of allowing their release only to a parent, legal guardian, or adult relative.289 In 1993, following several lower court decisions, the Supreme Court in Reno v. Flores upheld the INS's release rule, reasoning that the plaintiffs had no constitutional right to be released to any available adult who could take legal custody, and that the INS's policy sufficiently advanced the government's interest in protecting the child's welfare.290

Ultimately, in 1997, the parties reached a settlement agreement that created a "general policy favoring release" of alien minors in INS custody.291 Under the Flores Settlement, the government generally must transfer within five days a detained minor to the custody of a qualifying adult292 or a nonsecure state-licensed facility that provides residential, group, or foster care services for dependent children.293 But the alien's transfer may be delayed "in the event of an emergency or influx of minors into the United States," in which case the transfer must occur "as expeditiously as possible."294 In 2001, the parties stipulated that the Flores Settlement would terminate "45 days following [the INS's] publication of final regulations implementing this Agreement."295

In 2008, Congress enacted the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA), which "partially codified the Flores Settlement by creating statutory standards for the treatment of unaccompanied minors."296 Under the TVPRA, a UAC297 must be placed in ORR's custody pending formal removal proceedings, and typically must be transferred to ORR within 72 hours after DHS determines that the child is a UAC.298 Following transfer to ORR, the agency generally must place the UAC "in the least restrictive setting that is in the best interest of the child," and may place the child with a sponsoring individual or entity who "is capable of providing for the child's physical and mental well-being."299

In 2015, the Flores plaintiffs moved to enforce the Flores Settlement, arguing that DHS (which had replaced the former INS in 2003) violated the settlement by adopting a no-release policy for Central American families and confining minors in secure, unlicensed family detention facilities.300 In response, the government argued that the Flores Settlement did not apply to accompanied minors.301 In an order granting the plaintiffs' motion, the federal district court ruled that the Flores Settlement applied to both accompanied and unaccompanied minors, and that accompanying parents generally had to be released with their children.302 In a later order, the court determined that, upon an "influx of minors into the United States," DHS may "reasonably exceed" the general five-day limitation on detention, and suggested that 20 days may be reasonable in some circumstances.303