Introduction

This report presents background information and issues for Congress concerning the Navy's force structure and shipbuilding plans. The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the rate of Navy ship procurement, and the prospective affordability of the Navy's shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years.

The Navy's proposed FY2020 budget requests funding for the procurement of 12 new ships, including one Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier, three Virginia-class attack submarines, three DDG-51 class Aegis destroyers, one FFG(X) frigate, two John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers, and two TATS towing, salvage, and rescue ships.

The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy's proposed FY2020 shipbuilding program and the Navy's longer-term shipbuilding plans. Decisions that Congress makes on this issue can substantially affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements, and the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base.

Detailed coverage of certain individual Navy shipbuilding programs can be found in the following CRS reports:

- CRS Report R41129, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. (This report also covers the issue of the Administration's FY2020 budget proposal, which the Administration withdrew on April 30, to not fund a mid-life refueling overhaul [called a refueling complex overhaul, or RCOH] for the aircraft carrier Harry S. Truman [CVN-75], and to retire CVN-75 around FY2024.)

- CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report R44972, Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report RL33741, Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report R43543, Navy LPD-17 Flight II Amphibious Ship Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. (This report also covers the issue of funding for the procurement of an amphibious assault ship called LHA-9.)

- CRS Report R43546, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report R45757, Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

For a discussion of the strategic and budgetary context in which U.S. Navy force structure and shipbuilding plans may be considered, see Appendix A.

Background

Navy's 355-Ship Ship Force-Structure Goal

Introduction

On December 15, 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship force-level goal replaced a 308-ship force-level goal that the Navy released in March 2015. The 355-ship force-level goal is the largest force-level goal that the Navy has released since a 375-ship force-level goal that was in place in 2002-2004. In the years between that 375-ship goal and the 355-ship goal, Navy force-level goals were generally in the low 300s (see Appendix B). The force level of 355 ships is a goal to be attained in the future; the actual size of the Navy in recent years has generally been between 270 and 290 ships. Table 1 shows the composition of the 355-ship force-level objective.

|

Ship Category |

Number of ships |

|

Ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) |

12 |

|

Attack submarines (SSNs) |

66 |

|

Aircraft carriers (CVNs) |

12 |

|

Large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers [CGs] and destroyers [DDGs]) |

104 |

|

Small surface combatants (i.e., frigates [FFGs], Littoral Combat Ships, and mine warfare ships) |

52 |

|

Amphibious ships |

38 |

|

Combat Logistics Force (CLF) ships (i.e., at-sea resupply ships) |

32 |

|

Command and support ships |

39 |

|

TOTAL |

355 |

Source: U.S. Navy, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2020, Table A-1 on page 10.

355-Ship Goal Resulted from 2016 Force Structure Assessment (FSA)

The 355-ship force-level goal is the result of a Force Structure Assessment (FSA) conducted by the Navy in 2016. An FSA is an analysis in which the Navy solicits inputs from U.S. regional combatant commanders (CCDRs) regarding the types and amounts of Navy capabilities that CCDRs deem necessary for implementing the Navy's portion of the national military strategy and then translates those CCDR inputs into required numbers of ships, using current and projected Navy ship types. The analysis takes into account Navy capabilities for both warfighting and day-to-day forward-deployed presence.1 Although the result of the FSA is often reduced for convenience to single number (e.g., 355 ships), FSAs take into account a number of factors, including types and capabilities of Navy ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles, and weapons, as well as ship homeporting arrangements and operational cycles. The Navy conducts a new FSA or an update to the existing FSA every few years, as circumstances require, to determine its force-structure goal.

355-Ship Goal Made U.S. Policy by FY2018 NDAA

Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act, or NDAA (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115-91 of December 12, 2017), states the following:

SEC. 1025. Policy of the United States on minimum number of battle force ships.

(a) Policy.—It shall be the policy of the United States to have available, as soon as practicable, not fewer than 355 battle force ships, comprised of the optimal mix of platforms, with funding subject to the availability of appropriations or other funds.

(b) Battle force ships defined.—In this section, the term "battle force ship" has the meaning given the term in Secretary of the Navy Instruction 5030.8C.

The term battle force ships in the above provision refers to the ships that count toward the quoted size of the Navy in public policy discussions about the Navy.2

New FSA Now Being Done Could Change 355-Ship Figure and Force Mix

Overview

The Navy states that a new FSA is now underway as the successor to the 2016 FSA, and that this new FSA is to be completed by the end of 2019. The new FSA, Navy officials state, will take into account the Trump Administration's December 2017 National Security Strategy document and its January 2018 National Defense Strategy document, both of which put an emphasis on renewed great power competition with China and Russia, as well as updated information on Chinese and Russian naval and other military capabilities and recent developments in new technologies, including those related to unmanned vehicles (UVs).3 Navy officials have suggested in their public remarks that this new FSA could change the 355-ship figure, the planned mix of ships, or both.4

Potential New Fleet Architecture

Some observers, viewing statements by Navy officials, believe the new FSA in particular might shift the Navy's surface force to a more distributed architecture that includes a reduced proportion of large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers), an increased proportion of small surface combatants (i.e., frigates and LCSs), and a newly created third tier of unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). Some observers believe the new FSA might also change the Navy's undersea force to a more distributed architecture that includes, in addition to attack submarines (SSNs) and bottom-based sensors, a new element of extra-large unmanned underwater vehicles (XLUUVs), which might be thought of as unmanned submarines. In presenting its proposed FY2020 budget, the Navy highlighted its plans for developing and procuring USVs and UUVs in coming years.

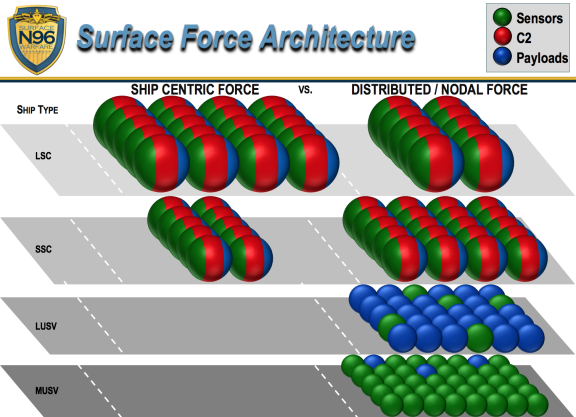

Figure 1 provides, for the surface combatant portion of the Navy,5 a conceptual comparison of the current fleet architecture (shown on the left as the "ship centric force") and the new, more-distributed architecture (shown on the right as the "distributed/nodal force"). The figure does not depict the entire surface combatant fleet, but rather a representative portion of it.

In the figure, each sphere represents a manned ship or USV. (Since the illustration focuses on the surface combatant force, it does not include UUVs.) As shown in the color coding, under both the current fleet architecture and the more-distributed architecture, the manned ships (i.e., the LSCs and SSCs) are equipped with a combination of sensors (green), command and control (C2) equipment (red), and payloads other than sensors and C2 equipment, meaning principally weapons (blue).

Under the more-distributed architecture, the manned ships would be on average smaller (because a greater share of them would be SSCs), and this would be possible because some of the surface combatant force's weapons and sensors would be shifted from the manned ships to USVs, with weapon-equipped Large USVs (LUSVs) acting as adjunct weapon magazines and sensor-equipped Medium USVs (MUSVs) contributing to the fleet's sensor network.

As shown in Figure 1, under the Navy's current surface combatant force architecture, there are to be 20 LSCs for every 10 SSCs (i.e., a 2:1 ratio of LSCs to SSCs), with no significant contribution from LUSVs and MUSVs. This is consistent with the Navy's current force-level objective, which calls for achieving a 355-ship fleet that includes 104 LSCs and 52 SSCs (a 2:1 ratio). Under the more-distributed architecture, the ratio of LSCs to SSCs would be reversed, with 10 LSCs for every 20 SSCs (a 1:2 ratio), and there would also now be 30 LUSVs and 40 MUSVs. A January 15, 2019, press report states

The Navy plans to spend this year taking the first few steps into a markedly different future, which, if it comes to pass, will upend how the fleet has fought since the Cold War. And it all starts with something that might seem counterintuitive: It's looking to get smaller.

"Today, I have a requirement for 104 large surface combatants in the force structure assessment; [and] I have [a requirement for] 52 small surface combatants," said Surface Warfare Director Rear Adm. Ronald Boxall. "That's a little upside down. Should I push out here and have more small platforms? I think the future fleet architecture study has intimated 'yes,' and our war gaming shows there is value in that."6

Another way of summarizing Figure 1 would be to say that the surface combatant force architecture (reading vertically down the figure) would change from 20+10+0+0 (i.e., a total of 30 surface combatant platforms, all manned) for a given portion of the surface combatant force, to 10+20+30+40 (i.e., a total of 100 surface combatant platforms, 70 of which would be LUSVs and MUSVs) for a given portion of the surface combatant force. The Navy refers to the more-distributed architecture's combination of LSCs, SSCs, LUSVs, and MUSVs as the Future Surface Combatant Force (FSCF).

Figure 1 is conceptual, so the platform ratios for the more-distributed architecture should be understood as notional or approximate rather than exact. The point of the figure is not that relative platform numbers under the more-distributed architecture would change to the exact ratios shown in the figure, but that they would evolve over time toward something broadly resembling those ratios.

Some observers have long urged the Navy to shift to a more-distributed fleet architecture, on the grounds that the Navy's current architecture—which concentrates much of the fleet's capability into a relatively limited number of individually larger and more-expensive surface ships—is increasingly vulnerable to attack by the improving maritime anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities (particularly anti-ship missiles and their supporting detection and targeting systems) of potential adversaries, particularly China.7 Shifting to a more-distributed architecture, these observers have argued, would

- complicate an adversary's targeting challenge by presenting the adversary with a larger number of Navy units to detect, identify, and track;

- reduce the loss in aggregate Navy capability that would result from the destruction of an individual Navy platform;

- give U.S. leaders the option of deploying USVs and UUVs in wartime to sea locations that would be tactically advantageous but too risky for manned ships; and

- increase the modularity and reconfigurability of the fleet for adapting to changing mission needs.8

For a number of years, Navy leaders acknowledged the views of those observers but continued to support the current fleet architecture. More recently, however, Navy leaders appear to have shifted their thinking, with comments from Navy officials like the one quoted above, Navy briefing slides like Figure 1, and the Navy's emphasis on USVs and UUVs in its FY2020 budget submission (see next section) suggesting that Navy leaders now support moving the fleet to a more-distributed architecture. The views of Navy leaders appear to have shifted in favor of a more-distributed architecture because they now appear to believe that such an architecture will be

- increasingly needed—as the observers have long argued—to respond effectively to the improving maritime A2/AD capabilities of other countries, particularly China;

- technically feasible as a result of advances in technologies for UVs and for networking widely distributed maritime forces that include significant numbers of UVs; and

- no more expensive, and possibly less expensive, than the current architecture.

The more-distributed architecture that Navy leaders now appear to support may differ in its details from distributed architectures that the observers have been advocating, but the general idea of shifting to a more-distributed architecture, and of using large UVs as a principal means of achieving that, appears to be similar. The Department of Defense (DOD) states that

The FY 2020 budget request diversifies and expands sea power strike capacity through procurement of offensively armed Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs). The USV investment, paired with increased investment in long-range maritime munitions, represents a paradigm shift towards a more balanced, distributed, lethal, survivable, and cost-imposing naval force that will better exploit adversary weaknesses and project power into contested environments.9

Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO)

Shifting to a more-distributed force architecture, Navy officials have suggested, could be appropriate for implementing the Navy's new overarching operational concept, called Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO). Observers view DMO as a response to both China's improving maritime anti-access/area denial capabilities (which include advanced weapons for attacking Navy surface ships) and opportunities created by new technologies, including technologies for UVs and for networking Navy ships, aircraft, unmanned vehicles, and sensors into distributed battle networks.

The Navy's FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan mentions DMO,10 and a December 2018 document from the Chief of Naval Operations states that the Navy will "Continue to mature the Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) concept and key supporting concepts" and "Design and implement a comprehensive operational architecture to support DMO."11 While Navy officials have provided few details in public about DMO, then-Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, in explaining DMO, stated in December 2018 that

Our fundamental force element right now in many instances is the [individual] carrier strike group. We're going to scale up so our fundamental force element for fighting is at the fleet[-wide] level, and the [individual] strike groups plug into those [larger] numbered fleets. And they will be, the strike groups and the fleet together, will be operating in a distributed maritime operations way."12

In its FY2020 budget submission, the Navy states that "MUSV and LUSV are key enablers of the Navy's Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) concept, which includes being able to forward deploy (alone or in teams/swarms), team with individual manned combatants or augment battle groups."13 The Navy states in its FY2020 budget submission that a Navy research and development effort focusing on concept generation and concept development (CG/CD) will

Continue CG/CD development efforts that carry-over from FY[20]19: Additional concepts and CONOPs [concepts of operation] to be developed in FY[20]20 will be determined through the CG/CD development process and additional external factors. Concepts under consideration include Unmanned Systems in support of DMO, Command and Control in support of DMO, Offensive Mine Warfare, Targeting in support of DMO, and Advanced Autonomous/Semi-autonomous Sustainment Systems.14

The Navy also states in its FY2020 budget submission that a separate Navy research and development effort for fleet experimentation activities will include activities that "address key DMO concept action plan items such as the examination of Fleet Command and Maritime Operation Center (MOC) capabilities and the employment of unmanned systems in support of DMO."15

A May 16, 2019, press report states

The Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Systems said Wednesday [May 15] he thinks the upcoming Force Structure Assessment (FSA) will focus on smaller surface combatants as the service looks to build up to a 355-ship Navy.

"I certainly don't see that [FSA fleet] number going down, but it is going to be more reflective of the DMO [Distributed Maritime Operations] construct and it includes not just the battle force ships, but the logistics ships, the trainers, the maritime operations centers, everything that we pull together to keep this machine running," Vice Adm. William Merz said during an event at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

"What we think is going to happen with this FSA is there will be more emphasis on the smaller surface combatants, mostly because the frigate looks like it's coming along very well and it's going to be more lethal than we had planned," Merz said.

Merz explained the likely outcome by comparing it to how Rear Adm. Ron Boxall, director of surface warfare (N96), talks about how the Navy has too many large surface combatants and needs to get more balanced.

"When you look at the lethality of the frigate, yeah that makes sense. So we'll see how the FSA handles the lethality of that – and then how does that bleed over into the other accounts," Merz said….

Merz revealed there will also be "a hard look at the logistics side" because while some logistics ships count as battle force ships some do not. He said the FSA will make an opinion on the non-battle force logistics vessels as well because it does not limit itself to those strict definitions.

The FSA will also take into account the evolution of the air wing, the length of the air wing, the range of the air wing on carriers and amphibious vessels, and how the Navy will cover its responsibilities.16

Large UVs and Navy Ship Count

Because LUSVs, MUSVs, and XLUUVs can be deployed directly from pier to perform missions that might otherwise be assigned to manned ships and submarines, some observers have a raised a question as to whether the large UVs covered in this report should be included in the top-level count of the number of ships in the Navy. Navy officials state that they have not yet decided whether to modify the top-level count of the number of ships in the Navy to include these large UVs.

Sustainment Costs

Regarding the potential sustainment costs of a larger fleet—a concern that the Navy highlighted in its FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan17—a May 15, 2019, press report states

The Navy's upcoming force structure assessment won't back away from the service's long-time goal of a 355-ship fleet, a top official said Wednesday [May 15], suggesting that the number may actually inch higher. But the service is also getting some sobering feedback on how much it will cost to sustain a significantly larger fleet— something it hasn't had to do in decades.

As the Navy plans for more ships, Vice Adm. William Merz Deputy Chief Of Naval Operations For Warfare Systems said Wednesday, "we're also coming to realize what that is going to cost, and how you're going to sustain today's fleet while continuing to grow." The planning process is "much more challenging than anyone realized," he said, "but we're much smarter about our business" than just a few years ago.

The much-anticipated Force Structure Assessment, which CNO Adm. John Richardson has said should be released this summer, is expected to lay out the kinds of capabilities the Navy wants in the near-term to meet and deter potential adversaries like China and Russia.

But taking the fleet from under 300 ships to at least 355 is a daunting task, Merz said at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. "We don't have the complex modeling to even understand what all of these costs are going to materialize to over the next 20 years," he said, but the service is "working hard to converge on a model" to sustain the ships over the long haul.18

Navy's Five-Year and 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans

FY2020 Five-Year (FY2020-FY2024) Shipbuilding Plan

Table 2 shows the Navy's FY2020 five-year (FY2020-FY2024) shipbuilding plan. The table also shows, for reference purposes, the ships funded for procurement in FY2019. The figures in the table reflect a Navy decision to show the aircraft carrier CVN-81 as a ship to be procured in FY2020 rather than a ship that was procured in FY2019. Congress, as part of its action on the Navy's proposed FY2019 budget, authorized the procurement of CVN-81 in FY2019.19

|

FY19 (enacted) |

FY20 (req.) |

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY20-FY24 Total |

|

|

Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine |

1 |

1 |

2 |

||||

|

Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarine |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|

Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class destroyer |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

13 |

|

Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) |

3 |

0 |

|||||

|

FFG(X) frigate |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

9 |

|

|

LHA amphibious assault ship |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

LPD-17 Fight II amphibious ship |

1 |

1 |

2 |

||||

|

Expeditionary Sea Base (ESB) ship |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF) ship |

1 |

0 |

|||||

|

John Lewis (TAO-205) class oiler |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

7 |

|

TATS towing, salvage, and rescue ship |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

TAGOS(X) ocean surveillance ship |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|||

|

TOTAL |

13 |

12 |

10 |

9 |

13 |

11 |

55 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on FY2020 Navy budget submission.

Notes: Ships shown are battle force ships—ships that count against 355-ship goal. The figures in the table reflect a Navy decision to show the aircraft carrier CVN-81 as a ship to be procured in FY2020 rather than a ship that was procured in FY2019. Congress, as part of its action on the Navy's proposed FY2019 budget, authorized the procurement of CVN-81 in FY2019.

As shown in Table 2, the Navy's proposed FY2020 budget requests funding for the procurement of 12 new ships, including one Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier, three Virginia-class attack submarines, three DDG-51 class Aegis destroyers, one FFG(X) frigate, two John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers, and two TATS towing, salvage, and rescue ships. If the Navy had listed CVN-81 as a ship procured in FY2019 rather than a ship to be procured in FY2020, then the total numbers of ships in FY2019 and FY2020 would be 14 and 11, respectively.

As also shown Table 2, the Navy's FY2020 five-year (FY2020-FY2024) shipbuilding plan includes 55 new ships, or an average of 11 new ships per year. The Navy's FY2019 budget submission also included a total of 55 ships in the period FY2020-FY2024, but the mix of ships making up the total of 55 for these years has been changed under the FY2020 budget submission to include one additional attack submarine, one additional FFG(X) frigate, and two (rather than four) LPD-17 Flight II amphibious ships over the five-year period. The FY2020 submission also makes some changes within the five-year period to annual procurement quantities for DDG-51 destroyers, ESBs, and TAO-205s without changing the five-year totals for these programs.

Compared to what was projected for FY2020 itself under the FY2019 budget submission, the FY2020 request accelerates from FY2023 to FY2020 the aircraft carrier CVN-81 (as a result of Congress's action to authorize the ship in FY2019), adds a third attack submarine, accelerates from FY2021 into FY2020 a third DDG-51, defers from FY2020 to FY2021 an LPD-17 Flight II amphibious ship to FY2021, defers from FY2020 to FY2023 an ESB ship, and accelerates from FY2021 to FY2020 a second TAO-205 class oiler.

FY2020 30-Year (FY2020-FY2049) Shipbuilding Plan

Table 3 shows the Navy's FY2020-FY2049 30-year shipbuilding plan. In devising a 30-year shipbuilding plan to move the Navy toward its ship force-structure goal, key assumptions and planning factors include but are not limited to ship construction times and service lives, estimated ship procurement costs, projected shipbuilding funding levels, and industrial-base considerations. As shown in Table 3, the Navy's FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan includes 304 new ships, or an average of about 10 per year.

|

FY |

CVNs |

LSCs |

SSCs |

SSNs |

LPSs |

SSBNs |

AWSs |

CLFs |

Supt |

Total |

|

20 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|||

|

21 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

||

|

22 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

||||

|

23 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

13 |

|||

|

24 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

||

|

25 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

|||

|

26 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

||

|

27 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

||

|

28 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

|

|

29 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

||

|

30 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

||

|

31 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

13 |

||

|

32 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

|

|

33 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

||

|

34 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|||

|

35 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

||||

|

36 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

37 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

||||||

|

38 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

7 |

|||||

|

39 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|||||

|

40 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

41 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|||||

|

42 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

43 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|||||

|

44 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

45 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|||

|

46 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

||||

|

47 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

||||

|

48 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

||

|

49 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

13 |

|||

|

Total |

7 |

76 |

58 |

61 |

5 |

12 |

28 |

27 |

30 |

304 |

Source: U.S. Navy, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2020, Table A2-1 on page 13.

Key: FY = Fiscal Year; CVNs = aircraft carriers; LSCs = surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers); SSCs = small surface combatants (i.e., Littoral Combat Ships [LCSs] and frigates [FFG(X)s]); SSNs = attack submarines; LPSs = large payload submarines; SSBNs = ballistic missile submarines; AWSs = amphibious warfare ships; CLFs = combat logistics force (i.e., resupply) ships; Supt = support ships.

Projected Force Levels Under FY2020 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Overview

Table 4 shows the Navy's projection of ship force levels for FY2020-FY2049 that would result from implementing the FY2020 30-year (FY2020-FY2049) 30-year shipbuilding plan shown in Table 3.

|

CVNs |

LSCs |

SSCs |

SSNs |

SSGN/LPSs |

SSBNs |

AWSs |

CLFs |

Supt |

Total |

|

|

355-ship goal |

12 |

104 |

52 |

66 |

0 |

12 |

38 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY20 |

11 |

94 |

30 |

52 |

4 |

14 |

33 |

29 |

34 |

301 |

|

FY21 |

11 |

92 |

33 |

53 |

4 |

14 |

34 |

30 |

34 |

305 |

|

FY22 |

11 |

93 |

33 |

52 |

4 |

14 |

34 |

31 |

39 |

311 |

|

FY23 |

11 |

95 |

32 |

51 |

4 |

14 |

35 |

31 |

41 |

314 |

|

FY24 |

11 |

94 |

35 |

47 |

4 |

14 |

36 |

32 |

41 |

314 |

|

FY25 |

10 |

95 |

35 |

44 |

4 |

14 |

37 |

32 |

42 |

313 |

|

FY26 |

10 |

96 |

36 |

44 |

2 |

14 |

38 |

31 |

43 |

314 |

|

FY27 |

9 |

100 |

38 |

42 |

1 |

13 |

37 |

32 |

44 |

316 |

|

FY28 |

10 |

102 |

41 |

42 |

13 |

38 |

32 |

44 |

322 |

|

|

FY29 |

10 |

104 |

43 |

44 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

44 |

325 |

|

|

FY30 |

10 |

107 |

45 |

46 |

11 |

36 |

32 |

44 |

331 |

|

|

FY31 |

10 |

110 |

47 |

48 |

11 |

36 |

32 |

43 |

337 |

|

|

FY32 |

10 |

112 |

49 |

49 |

11 |

36 |

32 |

44 |

343 |

|

|

FY33 |

10 |

115 |

50 |

51 |

11 |

38 |

32 |

44 |

351 |

|

|

FY34 |

10 |

117 |

52 |

53 |

11 |

36 |

32 |

44 |

355 |

|

|

FY35 |

10 |

114 |

55 |

54 |

11 |

34 |

32 |

45 |

355 |

|

|

FY36 |

10 |

109 |

57 |

56 |

11 |

35 |

32 |

45 |

355 |

|

|

FY37 |

10 |

107 |

58 |

58 |

10 |

35 |

32 |

45 |

355 |

|

|

FY38 |

10 |

108 |

59 |

57 |

10 |

35 |

32 |

44 |

355 |

|

|

FY39 |

10 |

105 |

61 |

58 |

10 |

37 |

32 |

42 |

355 |

|

|

FY40 |

9 |

105 |

62 |

59 |

10 |

37 |

32 |

41 |

355 |

|

|

FY41 |

10 |

104 |

61 |

59 |

11 |

37 |

32 |

41 |

355 |

|

|

FY42 |

9 |

106 |

60 |

61 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

|

FY43 |

9 |

108 |

57 |

61 |

1 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY44 |

9 |

109 |

55 |

62 |

1 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY45 |

10 |

107 |

55 |

63 |

1 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY46 |

9 |

106 |

54 |

64 |

2 |

12 |

37 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY47 |

9 |

107 |

54 |

65 |

2 |

12 |

35 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY48 |

9 |

109 |

51 |

66 |

2 |

12 |

35 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY49 |

10 |

108 |

50 |

67 |

3 |

12 |

35 |

31 |

39 |

355 |

Source: U.S. Navy, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2020, Table A2-4 on page 13.

Note: Figures for support ships include five JHSVs transferred from the Army to the Navy and operated by the Navy primarily for the performance of Army missions.

Key: FY = Fiscal Year; CVNs = aircraft carriers; LSCs = surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers); SSCs = small surface combatants (i.e., frigates, Littoral Combat Ships [LCSs], and mine warfare ships); SSNs = attack submarines; SSGNs/LPSs = cruise missile submarines/large payload submarines; SSBNs = ballistic missile submarines; AWSs = amphibious warfare ships; CLFs = combat logistics force (i.e., resupply) ships; Supt = support ships.

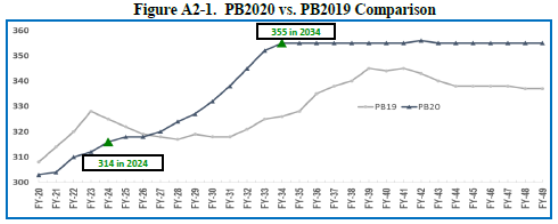

As shown in Table 4, if the FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan is implemented, the Navy projects that it will achieve a total of 355 ships by FY2034. This is about 20 years sooner than projected under the Navy's FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan. This is not primarily because the FY2020 30-year plan includes more ships than did the FY2019 plan: The total of 304 ships in the FY2020 plan is only three ships higher than the total of 301 ships in the FY2019 plan. Instead, it is primarily due to a decision announced by the Navy in April 2018, after the FY2019 budget was submitted, to increase the service lives of all DDG-51 destroyers—both those existing and those to be built in the future—to 45 years. Prior to this decision, the Navy had planned to keep older DDG-51s (referred to as the Flight I/II DDG-51s) in service for 35 years and newer DDG-51s (the Flight II/III DDG-51s) for 40 years. Figure 2 shows the Navy's projections for the total number of ships in the Navy under the Navy's FY2019 and FY2020 budget submissions. As can be seen in the figure, the Navy projected under the FY2019 plan that the fleet would not reach a total of 355 ships any time during the 30-year period.

Adjustment Needed for Withdrawn Proposal Regarding CVN-75 RCOH

The projected number of aircraft carriers in Table 4, the projected total number of all ships in Table 4, and the line showing the total number of ships under the Navy's FY2020 budget submission in Figure 2 all reflect the Navy's proposal, under its FY2020 budget submission, to not fund the mid-life nuclear refueling overhaul (called a refueling complex overhaul, or RCOH) of the aircraft carrier Harry S. Truman (CVN-75), and to instead retire CVN-75 around FY2024. On April 30, 2019, however, the Administration announced that it was withdrawing this proposal from the Navy's FY2020 budget submission. The Administration now supports funding the CVN-75 RCOH and keeping CVN-75 in service past FY2024.

As a result of the withdrawal of its proposal regarding the CVN-75 RCOH, the projected number of aircraft carriers and consequently the projected total number of all ships are now one ship higher for the period FY2022-FY2047 than what is shown in Table 4, and the line in Figure 2 would be adjusted upward by one ship for those years.20 (The figures in Table 4 are left unchanged from what is shown in the FY2020 budget submission so as to accurately reflect what is shown in that budget submission.)

355-Ship Total Attained 20 Years Sooner; Mix Does Not Match FSA Mix

As shown in Table 4, although the Navy projects that the fleet will reach a total of 355 ships in FY2034, the Navy in that year and subsequent years will not match the composition called for in the FY2016 FSA. Among other things, the Navy will have more than the required number of large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers) from FY2030 through FY2040 (a consequence of the decision to extend the service lives of DDG-51s to 45 years), fewer than the required number of aircraft carriers through the end of the 30-year period, fewer than the required number of attack submarines through FY2047, and fewer than the required number of amphibious ships through the end of the 30-year period. The Navy acknowledges that the mix of ships will not match that called for by the 2016 FSA but states that if the Navy is going to have too many ships of a certain kind, DDG-51s are not a bad type of ship to have too many of, because they are very capable multi-mission ships.

Issues for Congress

Whether New FSA Will Change 355-Ship Goal and, If So, How

One issue for Congress is whether the new FSA that the Navy is conducting will change the 355-ship force-level objective established by the 2016 FSA and, if so, in what ways. As discussed earlier, Navy officials have suggested in their public remarks that this new FSA could shift the Navy toward a more distributed force architecture, which could change the 355-ship figure, the planned mix of ships, or both. The issue for Congress is how to assess the appropriateness of the Navy's FY2020 shipbuilding plans when a key measuring stick for conducting that assessment—the Navy's force-level goal and planned force mix—might soon change.

Affordability of 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Overview

Another oversight issue for Congress concerns the prospective affordability of the Navy's 30-year shipbuilding plan. This issue has been a matter of oversight focus for several years, and particularly since the enactment in 2011 of the Budget Control Act, or BCA (S. 365/P.L. 112-25 of August 2, 2011). Observers have been particularly concerned about the plan's prospective affordability during the decade or so from the mid-2020s through the mid-2030s, when the plan calls for procuring Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines as well as replacements for large numbers of retiring attack submarines, cruisers, and destroyers.21

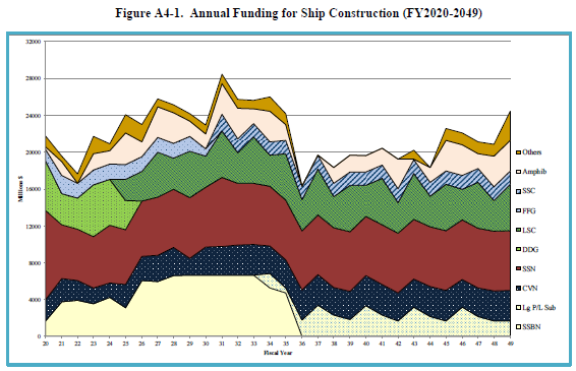

Figure 3 shows, in a graphic form, the Navy's estimate of the annual amounts of funding that would be needed to implement the Navy's FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan. The figure shows that during the period from the mid-2020s through the mid-2030s, the Navy estimates that implementing the FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan would require roughly $24 billion per year in shipbuilding funds.

Concern Regarding Potential Impact of Columbia-Class Program

As discussed in the CRS report on the Columbia-class program,22 the Navy since 2013 has identified the Columbia-class program as its top program priority, meaning that it is the Navy's intention to fully fund this program, if necessary at the expense of other Navy programs, including other Navy shipbuilding programs. This led to concerns that in a situation of finite Navy shipbuilding budgets, funding requirements for the Columbia-class program could crowd out funding for procuring other types of Navy ships. These concerns in turn led to the creation by Congress of the National Sea-Based Deterrence Fund (NSBDF), a fund in the DOD budget that is intended in part to encourage policymakers to identify funding for the Columbia-class program from sources across the entire DOD budget rather than from inside the Navy's budget alone.

Several years ago, when concerns arose about the potential impact of the Columbia-class program on funding available for other Navy shipbuilding programs, the Navy's shipbuilding budget was roughly $14 billion per year, and the roughly $7 billion per year that the Columbia-class program is projected to require from the mid-2020s to the mid-2030s (see Figure 3) represented roughly one-half of that total. With the Navy's shipbuilding budget having grown in more recent years to a total of roughly $24 billion per year, the $7 billion per year projected to be required by the Columbia-class program during those years does not loom proportionately as large as it once did in the Navy's shipbuilding budget picture. Even so, some concerns remain regarding the potential impact of the Columbia-class program on funding available for other Navy shipbuilding programs.

Potential for Cost Growth on Navy Ships

If one or more Navy ship designs turn out to be more expensive to build than the Navy estimates, then the projected funding levels shown in Figure 3 would not be sufficient to procure all the ships shown in the 30-year shipbuilding plan. As detailed by CBO23 and GAO,24 lead ships in Navy shipbuilding programs in many cases have turned out to be more expensive to build than the Navy had estimated. Ship designs that can be viewed as posing a risk of being more expensive to build than the Navy estimates include Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carriers, Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines, Virginia-class attack submarines equipped with the Virginia Payload Module (VPM), Flight III versions of the DDG-51 destroyer, FFG(X) frigates, LPD-17 Flight II amphibious ships, and John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers, as well as other new classes of ships that the Navy wants to begin procuring years from now.

CBO Estimate

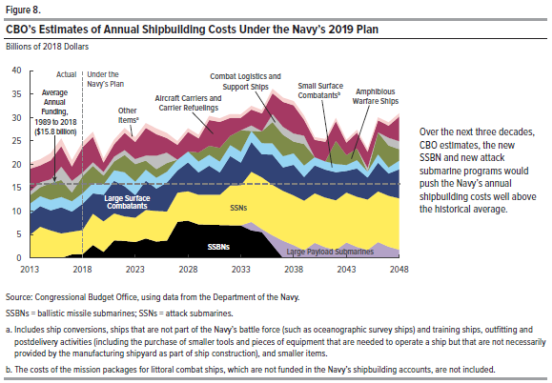

The statute that requires the Navy to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan each year (10 U.S.C. 231) also requires CBO to submit its own independent analysis of the potential cost of the 30-year plan (10 U.S.C. 231[d]). CBO is now preparing its estimate of the cost of the Navy's FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan. In the meantime, Figure 4 shows, in a graphic form, CBO's estimate of the annual amounts of funding that would be needed to implement the Navy's FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan. This figure might be compared to the Navy's estimate of its FY2020 30-year plan as shown in Figure 3, although doing so poses some apples-vs.-oranges issues, as the Navy's FY2019 and FY2020 30-year plans do not cover exactly the same 30-year periods, and for the years they do have in common, there are some differences in types and numbers of ships to be procured in certain years.

CBO analyses of past Navy 30-year shipbuilding plans have generally estimated the cost of implementing those plans to be higher than what the Navy estimated. Consistent with that past pattern, as shown in Table 5, CBO's estimate of the cost to implement the Navy's FY2019 30-year (FY2019-FY2048) shipbuilding plan is about 27% higher than the Navy's estimated cost for the FY2019 plan. (Table 5 does not pose an apples-vs.-oranges issue, because both the Navy and CBO estimates in this table are for the Navy's FY2019 30-year plan.) More specifically, as shown in the table, CBO estimated that the cost of the first 10 years of the FY2019 30-year plan would be about 2% higher than the Navy's estimate; that the cost of the middle 10 years of the plan would be about 13% higher than the Navy's estimate; and that the cost of the final 10 years of the plan would be about 27% higher than the Navy's estimate.25

Table 5. Navy and CBO Estimates of Cost of FY2019 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Funding for new-construction ships, in billions of constant FY2018 dollars

|

First 10 years of the plan |

Middle 10 years of the plan |

Final 10 years of the plan |

Entire 30 years of the plan |

|

|

Navy estimate |

19.7 |

22.7 |

21.1 |

21.0 |

|

CBO estimate |

20.0 |

25.7 |

28.6 |

26.7 |

|

% difference between Navy and CBO estimates |

2% |

13% |

36% |

27% |

Source: Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2019 Shipbuilding Plan, October 2018, Table 4 on page 13.

Treatment of Inflation

The growing divergence between CBO's estimate and the Navy's estimate as one moves from the first 10 years of the 30-year plan to the final 10 years of the plan is due in part to a technical difference between CBO and the Navy regarding the treatment of inflation. This difference compounds over time, making it increasingly important as a factor in the difference between CBO's estimates and the Navy's estimates the further one goes into the 30-year period. In other words, other things held equal, this factor tends to push the CBO and Navy estimates further apart as one proceeds from the earlier years of the plan to the later years of the plan.26

Designs of Future Classes of Ships

The growing divergence between CBO's estimate and the Navy's estimate as one moves from the first 10 years of the 30-year plan to the final 10 years of the plan is also due to differences between CBO and the Navy about the costs of certain ship classes, particularly classes that are projected to be procured starting years from now. The designs of these future ship classes are not yet determined, creating more potential for CBO and the Navy to come to differing conclusions regarding their potential cost. For the FY2019 30-year plan, the largest source of difference between CBO and the Navy regarding the costs of individual ship classes was a new class of SSNs that the Navy wants to begin procuring in FY2034 as the successor to the Virginia-class SSN design. This new class of SSN, CBO says, accounted for 42% of the difference between the CBO and Navy estimates for the FY2019 30-year plan, in part because there were a substantial number of these SSNs in the plan, and because those ships occur in the latter years of the plan, where the effects of the technical difference between CBO and the Navy regarding the treatment of inflation show more strongly.

The second-largest source of difference between CBO and the Navy regarding the costs of individual ship classes was a new class of large surface combatant (i.e., cruiser or destroyer) that the Navy wants to begin procuring in the future, which accounted for 20% of the difference, for reasons that are similar to those mentioned above for the new class of SSNs. The third-largest source of difference was the new class of frigates (FFG[X]s) that the Navy wants to begin procuring in FY2020, which accounts for 9% of the difference. The remaining 29% of difference between the CBO and Navy estimates was accounted for collectively by several other shipbuilding programs, each of which individually accounts for between 1% and 4% of the difference. The Columbia-class program, which accounted for 4%, is one of the programs in this final group.27

Sustainment Cost

As mentioned earlier, in addition to the issue of the cost to build new ships, the Navy in its FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan highlighted a concern over the potential costs to sustain a larger fleet. On this issue, the FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan states in part

Coincident with the relatively new dynamic of purchasing more ships to grow the force instead of simply replacing ships or shrinking the force, is the responsibility to "own" the additional inventory when it arrives.

Consistent annual funding in the shipbuilding account is foundational for an efficient industrial base in support of steady growth and long-term maintenance planning, but equally important is the properly phased, additional funding needed for operations and sustainment accounts as each new ship is delivered—the much larger fiscal burden over the life of a ship and the essence of the challenge to remain balanced across the three integral elements of readiness–capability–capacity. Because the Navy [until recently] has been shrinking not growing, and because of the disconnected timespan from purchase to delivery, often five years or more and often beyond the FYDP, there is risk of underestimating the aggregate sustainment costs looming over the horizon that must now be carefully considered in fiscal forecasting.

For a ship, the rough rule of thumb for cost is 30 percent for procurement and 70 percent for operating and sustainment; for example, a ship that costs $1B to buy costs $3.3B to own, amortized over its lifespan. Accordingly, multi-ship deliveries can add hundreds of millions of dollars to a budget year, and then require the same funding per year thereafter, compounded by additional deliveries in subsequent years and only offset by ship retirements, which lag deliveries when growing the force. A similar dynamic occurs when the life of a ship is extended. Sustainment resources programmed to shift from a retiring ship to a new ship must now stay in place – for the duration of the extension. The burden continues to grow until equilibrium is reached at the desired higher inventory, when deliveries match retirements and all resourcing accounts reach steady-state at a higher, enduring sustainment cost.

For perspective, the current budget, among the largest ever, supports a modern fleet of approximately 300 ships, nearly 20 percent fewer than the goal of 355. The battle force inventory… rises from 301 ships in FY2020 to [a projected figure of] 314 ships in FY2024, and then 355 in FY2034. The programmed sustainment cost… is $24B [billion] in FY2020 and rises to $30B [billion in FY2024 in TY$ [then-year dollars]. When the battle force inventory reaches 355 in FY2034, [the] estimated cost to sustain that fleet will approach $40B (TY$), 32% higher than in FY2024. For now, included in this sustainment estimate are only personnel, planned maintenance, and some operations; representing those costs tied directly to owning and operating a ship, easily modeled today, and already line-item accounted for in the budget. Equally important additional costs, but not yet included in the future estimate, are those not easily associated with individual ships and require complex modeling for long-term forecasting (beyond 3 to 5 years), such as the balance of the operations accounts (market and schedule driven), modernization and ordnance (threat and technology driven), infrastructure and training (services spread across many ships), aviation detachments, networks and cyber support, plus others….

Less of a challenge when shrinking the force, the Navy is now working towards developing the complex model needed to capture indirect costs for growing the force. Until then, macro ratios are helpful in estimating rough orders of magnitude beyond the FYDP and for identifying future areas of concern. Similar to procurement, estimates will be less precise deeper into the plan. Recovering from the long-term investment imbalance has proven to be costly, particularly in the readiness accounts. As readiness becomes more accurately defined, the modeling will improve and so will the ability to more accurately forecast. However, no matter the method, the anticipated cost of sustaining the proper mix of 355 ships is anticipated to be substantial, and reform efforts and balanced scalability will continue to be the drivers going forward.28

Legislative Activity for FY2020

CRS Reports Tracking Legislation on Specific Navy Shipbuilding Programs

Detailed coverage of legislative activity on certain Navy shipbuilding programs (including funding levels, legislative provisions, and report language) can be found in the following CRS reports:

- CRS Report R41129, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. (This report also covers the issue of the Administration's FY2020 budget proposal, which the Administration withdrew on April 30, to not fund a mid-life refueling overhaul [called a refueling complex overhaul, or RCOH] for the aircraft carrier Harry S. Truman [CVN-75], and to retire CVN-75 around FY2024.)

- CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report R44972, Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report RL33741, Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report R43543, Navy LPD-17 Flight II Amphibious Ship Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. (This report also covers the issue of funding for the procurement of an amphibious assault ship called LHA-9.)

- CRS Report R43546, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

- CRS Report R45757, Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Legislative activity on individual Navy shipbuilding programs that are not covered in detail in the above reports is covered below.

Summary of Congressional Action on FY2020 Funding Request

The Navy's proposed FY2020 budget requests funding for the procurement of 12 new ships:

- 1 Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier;

- 3 Virginia-class attack submarines;

- 3 DDG-51 class Aegis destroyers;

- 1 FFG(X) frigate;

- 2 John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers; and

- 2 TATS towing, salvage, and rescue ships.

As noted earlier, the above list of 12 ships reflects a Navy decision to show the aircraft carrier CVN-81 as a ship to be procured in FY2020 rather than a ship that was procured in FY2019. Congress, as part of its action on the Navy's proposed FY2019 budget, authorized the procurement of CVN-81 in FY2019.

The Navy's proposed FY2020 shipbuilding budget also requests funding for ships that have been procured in prior fiscal years, and ships that are to be procured in future fiscal years, as well as funding for activities other than the building of new Navy ships.

Table 6 summarizes congressional action on the Navy's FY2020 funding request for Navy shipbuilding. The table shows the amounts requested and congressional changes to those requested amounts. A blank cell in a filled-in column showing congressional changes to requested amounts indicates no change from the requested amount.

Table 6. Summary of Congressional Action on FY2020 Funding Request

Millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth; totals may not add due to rounding

|

Line number |

Program |

Request |

Congressional changes to requested amounts |

|||||

|

Authorization |

Appropriation |

|||||||

|

HASC |

SASC |

Conf. |

HAC |

SAC |

Conf. |

|||

|

Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN) appropriation account |

||||||||

|

001 |

Columbia-class SSBN AP |

1,698.9 |

125.0 |

125.0 |

-86.9 |

|||

|

002 |

CVN-78 aircraft carrier |

2,347.0 |

-395.0 |

-281.0 |

||||

|

003 |

Virginia-class SSN |

7,155.9 |

-550.0 |

-2,464.0 |

-2,963.6 |

|||

|

004 |

Virginia-class SSN AP |

2,769.6 |

1,500.0 |

1,497.0 |

||||

|

005 |

CVN refueling overhaul |

647.9 |

-211.0 |

-50.0 |

20.0 |

|||

|

006 |

CVN refueling overhaul AP |

0 |

17.0 |

16.9 |

16.9 |

|||

|

007 |

DDG-1000 |

155.9 |

||||||

|

008 |

DDG-51 |

5,099.3 |

-86.0 |

-20.0 |

-84.0 |

|||

|

009 |

DDG-51 AP |

224.0 |

260.0 |

|||||

|

010 |

LCS |

0 |

||||||

|

011 |

FFG(X) |

1,281.2 |

-15.0 |

|||||

|

012 |

LPD-17 Flight II |

0 |

100.0 |

525.0 |

||||

|

013 |

LPD-17 Flight II AP |

247.1 |

-100.0 |

-247.1 |

-247.1 |

|||

|

014 |

ESB |

0 |

||||||

|

015 |

LHA |

0 |

650.0 |

|||||

|

016 |

LHA AP |

0 |

||||||

|

017 |

EPF |

0 |

49.0 |

|||||

|

018 |

TAO-205 |

981.2 |

-374.0 |

|||||

|

019 |

TAO-205 AP |

73.0 |

-73.0 |

|||||

|

020 |

TATS |

150.3 |

||||||

|

021 |

Oceanographic ships |

0 |

||||||

|

022 |

LCU 1700 landing craft |

85.7 |

-2.0 |

|||||

|

023 |

Outfitting |

754.7 |

-111.1 |

-50.0 |

-18.4 |

|||

|

024 |

Ship-to-shore connector (SSC) |

0 |

84.8 |

65 |

||||

|

025 |

Service craft |

56.3 |

25.5 |

|||||

|

026 |

LCAC landing craft |

0 |

||||||

|

027 |

USCG icebreakers AP |

0 |

||||||

|

028 |

Completion of prior-year ships |

55.7 |

-30.0 |

49.0 |

||||

|

029 |

Ship-to-Shore connector AP |

0 |

40.4 |

|||||

|

TOTAL |

23,783.7 |

-1,569.3 |

360.7 |

-2,084.2 |

||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy FY2020 budget submission, committee reports, and explanatory statements on the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act and FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act.

Notes: Millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth. A blank cell indicates no change to requested amount. Totals may not add due to rounding. AP is advance procurement funding; HASC is House Armed Services Committee; SASC is Senate Armed Services Committee; HAC is House Appropriations Committee; SAC is Senate Appropriations Committee; Conf. is conference report.

FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2500/S. 1790)

House

The House Armed Services Committee, in its report (H.Rept. 116-120 of June 19, 2019) on H.R. 2500, recommended the funding levels shown in the HASC column of Table 6.

Section 118 of H.R. 2500 as reported by the committee states

SEC. 118. NATIONAL DEFENSE RESERVE FLEET VESSEL.

(a) In General.--Subject to the availability of appropriations, the Secretary of the Navy, acting through the executive agent described in subsection (e), shall seek to enter into a contract for the construction of one sealift vessel for the National Defense Reserve Fleet.

(b) Delivery Date.--The contract entered into under subsection (a) shall specify a delivery date for the sealift vessel of not later than September 30, 2026.

(c) Design and Construction Requirements.--

(1) Use of existing design.--The design of the sealift vessel shall be based on a domestic or foreign design that exists as of the date of the enactment of this Act.

(2) Commercial standards and practices.--Subject to paragraph (1), the sealift vessel shall be constructed using commercial design standards and commercial construction practices that are consistent with the best interests of the Federal Government.

(3) Domestic shipyard.--The sealift vessel shall be constructed in a shipyard that is located in the United States.

(d) Certificate and Endorsement.--The sealift vessel shall meet the requirements necessary to receive a certificate of documentation and a coastwise endorsement under chapter 121 of tile 46, United States Code, and the Secretary of the Navy shall ensure that the completed vessel receives such a certificate and endorsement.

(e) Executive Agent.--

(1) In general.--The Secretary of the Navy shall seek to enter into a contract or other agreement with a private-sector entity under which the entity shall act as executive agent for the Secretary for purposes of the contract under subsection (a).

(2) Responsibilities.--The executive agent described in paragraph (1) shall be responsible for--

(A) selecting a shipyard for the construction of the sealift vessel;

(B) managing and overseeing the construction of the sealift vessel; and

(C) such other matters as the Secretary of the Navy determines to be appropriate

(f) Use of Incremental Funding.--With respect to the contract entered into under subsection (a), the Secretary of the Navy may use incremental funding to make payments under the contract.

(g) Sealift Vessel Defined.--In this section, the term ``sealift vessel'' means the sealift vessel constructed for the National Defense Reserve Fleet pursuant to the contract entered into under subsection (a).

Section 806 of H.R. 2500 as reported by the committee states

SEC. 806. REQUIREMENT THAT CERTAIN SHIP COMPONENTS BE MANUFACTURED IN THE NATIONAL TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRIAL BASE.

(a) Additional Procurement Limitation.--Section 2534(a) of title 10, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following new paragraph:

``(6) Components for auxiliary ships.--Subject to subsection (k), the following components:

``(A) Auxiliary equipment, including pumps, for all shipboard services.

``(B) Propulsion system components, including engines, reduction gears, and propellers.

``(C) Shipboard cranes.

``(D) Spreaders for shipboard cranes.''.

(b) Implementation.--Such section is further amended by adding at the end the following new subsection:

``(k) Implementation of Auxiliary Ship Component Limitation.--Subsection (a)(6) applies only with respect to contracts awarded by the Secretary of a military department for new construction of an auxiliary ship after the date of the enactment of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 using funds available for National Defense Sealift Fund programs or Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy. For purposes of this subsection, the term `auxiliary ship' does not include an icebreaker.''.

Section 1022 of H.R. 2500 as reported by the committee states

SEC. 1022. USE OF NATIONAL DEFENSE SEALIFT FUND FOR PROCUREMENT OF TWO USED VESSELS.

Pursuant to section 2218(f)(3) of title 10, United States Code, and using amounts authorized to be appropriated for Operation and Maintenance, Navy, for fiscal year 2020, the Secretary of the Navy shall seek to enter into a contract for the procurement of two used vessels.

Section 1024 of H.R. 2500 as reported by the committee states

SEC. 1024. REPORT ON SHIPBUILDER TRAINING AND THE DEFENSE INDUSTRIAL BASE.

Not later than 180 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Secretary of Defense shall submit to the Committees on Armed Services of the Senate and House of Representatives a report on shipbuilder training and hiring requirements necessary to achieve the Navy's 30-year shipbuilding plan and to maintain the shipbuilding readiness of the defense industrial base. Such report shall include each of the following:

(1) An analysis and estimate of the time and investment required for new shipbuilders to gain proficiency in particular shipbuilding occupational specialties, including detailed information about the occupational specialty requirements necessary for construction of naval surface ship and submarine classes to be included in the Navy's 30-year shipbuilding plan.

(2) An analysis of the age demographics and occupational experience level (measured in years of experience) of the shipbuilding defense industrial workforce.

(3) An analysis of the potential time and investment challenges associated with developing and retaining shipbuilding skills in organizations that lack intermediate levels of shipbuilding experience.

(4) Recommendations concerning how to address shipbuilder training during periods of demographic transition, including whether emerging technologies, such as augmented reality, may aid in new shipbuilder training.

(5) Recommendations concerning how to encourage young adults to enter the defense shipbuilding industry and to develop the skills necessary to support the shipbuilding defense industrial base.

Section 3118 of H.R. 2500 as reported by the committee states

SEC. 3118. PROGRAM FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT OF ADVANCED NAVAL NUCLEAR FUEL SYSTEM BASED ON LOW-ENRICHED URANIUM.

(a) Establishment.--Not later than 60 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Administrator for Nuclear Security shall establish a program to assess the viability of using low-enriched uranium in naval nuclear propulsion reactors, including such reactors located on aircraft carriers and submarines, that meet the requirements of the Navy.

(b) Activities.--In carrying out the program under subsection (a), the Administrator shall carry out activities to develop an advanced naval nuclear fuel system based on low-enriched uranium, including activities relating to--

(1) down-blending of high-enriched uranium into low-enriched uranium;

(2) manufacturing of candidate advanced low-enriched uranium fuels;

(3) irradiation tests and post-irradiation examination of these fuels; and

(4) modification or procurement of equipment and infrastructure relating to such activities.

(c) Report.--Not later than 120 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Administrator shall submit to the congressional defense committees a plan outlining the activities the Administrator will carry out under the program established under subsection (a), including the funding requirements associated with developing a low-enriched uranium fuel.

H.Rept. 116-120 states

Future Fleet Architecture

The committee notes that the National Defense Strategy indicates that the United States is in a great powers competition to include the Russian Federation and the People's Republic of China. The committee also believes that this great powers competition will heavily rely on our naval force structure to optimally address Russia and China in both the Pacific and the Arctic, as well as impending tensions with the Iranian regime in the Persian Gulf. The committee believes that it is imperative to include a larger long-term force structure to address these global challenges. The committee also believes that to ensure a continued projection of naval power around the world, the Navy should include in their forthcoming 2019 Force Structure Assessment necessary vessels to address sufficient operations in the Arctic. Therefore, the committee directs the Secretary of the Navy to brief the House Committee on Armed Services by December 31, 2019 regarding the force structure plan to compete with adversaries in the Pacific and Arctic Oceans and the Persian Gulf. This briefing should also address the defense industrial base and any associated maritime sector weaknesses that need to be addressed to support the expanded force structure. (Pages 18-19)

H.Rept. 116-120 also states

Sourcing of Domestic Components for U.S. Navy Ships

The committee is concerned with the sourcing of non-domestic components on U.S. Navy ships. The committee directs the Secretary of the Navy to provide a report to the congressional defense committees by December 1, 2019, on the feasibility of sourcing domestic components such as: auxiliary equipment, including pumps; propulsion system components, including engines, reduction gears, and propellers; shipboard cranes and spreaders for shipboard cranes; and other components on all Navy ships. (Page 186)

H.Rept. 116-120 also states

Low-Enriched Uranium Fuel for Naval Reactors

The committee notes that since September 11, 2001, the U.S. Government has sought to remove weapons-usable highly enriched uranium (HEU) containing 20 percent or more uranium-235 from as many locations as possible because of concerns related to nuclear terrorism. The committee notes that the primary focus of this strategy has been on replacing HEU civilian research reactor fuel and targets used in the production of medical radioisotopes, with non-weapons-usable low-enriched uranium (LEU) fuel and targets. This program to reduce the use of HEU for civilian purposes has been successful in reducing the amount of HEU worldwide that could have been at risk of theft of diversion. However, this effort did not address the use of HEU for military purposes. Naval reactors account for the largest share of global HEU use other than nuclear weapons, and in the United States, the fuel is fabricated in civilian, not military, facilities. The committee has been supportive of efforts to assess the feasibility of using low-enriched uranium for naval reactors as such use would not only benefit nuclear non-proliferation efforts but also maintain the research and development skills necessary to sustain innovation and expertise with regard to naval fuel as research and development efforts on the Columbia-class reactor end. The committee continues to support efforts to assess the feasibility of using LEU in naval reactors to meet military requirements for aircraft carriers and submarines.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (Public Law 115–91) required a nuclear submarine study. However, this study lacked sufficient detail to respond to the congressional mandate. Therefore, the committee directs the Administrator for Nuclear Security, in coordination with the Secretary of the Navy, to provide a report to the congressional defense committees not later than December 15, 2019, assessing the feasibility of a design of the reactor module of the Virginia-Class replacement nuclear powered attack submarine that retains the existing hull diameter but leaves sufficient space for an LEU-fueled reactor with a life of the ship core, possibly with an increased module length. If a life of the ship core is unattainable, the report should include the feasibility of a reactor design with the maximum attainable core life and a configuration that enables rapid refueling. (Page 343)

Senate

The Senate Armed Services Committee, in its report (S.Rept. 116-48 of June 11, 2019) on S. 1790, recommended the funding levels shown in the SASC column of Table 6. S.Rept. 116-48 states

Outfitting

The budget request included $754.7 million in line number 23 of Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN), for outfitting.

Based on planned delivery dates, the committee notes that post-delivery funding is early-to-need for LCS-21 ($5.0 million). The committee also notes the unjustified outfitting cost growth for SSN-793, SSN-794, SSN-795, and SSN-796 ($20.0 million). The committee further notes unjustified post-delivery cost growth for DDG-1000 ($25.0 million).

Therefore, the committee recommends a decrease of $50.0 million in line number 23 of SCN.

Service craft

The budget request included $56.3 million in line number 25 of Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN), for service craft.

In order to increase training opportunities for Surface Warfare Officer candidates from all accession sources, the committee believes that the Navy should replace the six YP-676 class craft slated for disposal with upgraded YP-703 class craft that incorporate modernization, training, and habitability improvements derived from lessons learned with existing YP-703 craft.

The committee urges the Secretary of the Navy to release a request for proposals for the detail design and construction of upgraded YP-703 class craft not later than fiscal year 2020. The committee notes that the Navy's current cost estimate for acquisition of the first upgraded YP-703 class craft is $25.5 million.

Therefore, the committee recommends an increase of $25.5 million in line number 25 of SCN.

Expeditionary Fast Transport (T-EPF 14) conversion

The budget request included $55. 7 million in line number 28 of Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN), for completion of prior year shipbuilding programs.

The committee notes that the Chief of Naval Operations' unfunded priority list states that additional funding could provide for the conversion of an Expeditionary Fast Transport (T-EPF 14) into an Expeditionary Medical Transport to better fulfill distributed maritime medical requirements.

Therefore, the committee recommends an increase of $49.0 million in line number 28 of SCN.

Ship to shore connector advance procurement

The budget request included no funding in line number 29 of Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN), for ship to shore connector advance procurement.

The committee understands that additional funding could provide needed stability for certain suppliers in the ship to shore connector program.

Therefore, the committee recommends an increase of $40.4 million in line number 29 of SCN. (Pages 24-25)

Section 821 of S. 1790 as reported by the committee states

SEC. 821. Naval vessel certification required before Milestone B approval.

Section 2366b(a) of title 10, United States Code, is amended—

(1) in paragraph (3)(O), by striking "; and" and inserting a semicolon;

(2) in paragraph (4), by striking the period at the end and inserting "; and"; and

(3) by adding at the end the following new paragraph:

"(5) in the case of a naval vessel program, certifies compliance with the requirements of section 8669b of this title.".

Section 861 of S. 1790 as reported by the committee states:

SEC. 861. Notification of Navy procurement production disruptions.

(a) In general.—Chapter 137 of title 10, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following new section:

"§ 2339b. Notification of Navy procurement production disruptions

"(a) Requirement for contractor To provide notice of delays.—The Secretary of the Navy shall require prime contractors of any Navy procurement program to report within 15 calendar days any stop work order or other manufacturing disruption of 15 calendar days or more, by the prime contractor or any sub-contractor, to the respective program manager and Navy technical authority.

"(b) Quarterly reports.—The Secretary of the Navy shall submit to the congressional defense committees not later than 15 calendar days after the end of each quarter of a fiscal year a report listing all notifications made pursuant to subsection (a) during the preceding quarter.".

(b) Clerical amendment.—The table of sections at the beginning of chapter 137 of title 10, United States Code, is amended by inserting after the item relating to section 2339a the following new item:

"2339b. Notification of Navy procurement production disruptions.".

Regarding Section 861, S.Rept. 116-48 states

Notification of Navy procurement production disruptions (sec. 861)

The committee recommends a provision that would require the Secretary of the Navy to require prime contractors of any Navy procurement program to report, within 15 calendar days of any contractor or subcontractor stop work order or within 15 days of a contractor or subcontractor manufacturing disruption that has lasted 15 calendar days, to the respective program manager and Navy technical authority. The provision would also require the Secretary of the Navy to provide a quarterly notification of such disruptions to the congressional defense committees.

The committee is concerned by the delay in reporting of recent stop work orders and other manufacturing disruptions to Navy program management officials. The committee notes that multiple shipbuilding programs have been negatively impacted by unacceptable delays in reporting such disruptions. The committee believes that more timely notifications of such disruptions will decrease the time required to initiate and complete corrective actions necessary to resume production. (Page 221)

Section 1016 of S. 1790 as reported by the committee states

SEC. 1016. Modification of authority to purchase vessels using funds in National Defense Sealift Fund.

(a) In general.—Section 2218(f)(3)(E) of title 10, United States Code, is amended—

(1) in clause (i), by striking "ten new sealift vessels" and inserting "ten new vessels that are sealift vessels, auxiliary vessels, or a combination of such vessels"; and

(2) in clause (ii), by striking "sealift".

(b) Effective date.—The amendments made by subsection (a) shall take effect on October 1, 2019, and shall apply with respect to fiscal years beginning on or after that date.

Section 1017 of S. 1790 as reported by the committee states