Introduction

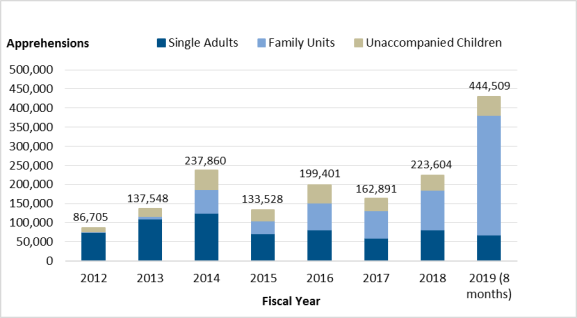

Instability in Central America—particularly the "Northern Triangle" nations of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—is one of the most pressing challenges for U.S. policy in the Western Hemisphere. These countries are struggling with widespread insecurity, fragile political and judicial systems, and high levels of poverty and unemployment. The inability of the Northern Triangle governments to address those challenges effectively has had far-reaching implications for the United States. Transnational criminal organizations have taken advantage of the situation, utilizing the region to traffic approximately 90% of cocaine destined for the United States, among other illicit activities.1 The region has also become a significant source of mixed migration flows of asylum-seekers and economic migrants to the United States.2 In the first eight months of FY2019, U.S. authorities apprehended nearly 445,000 unauthorized migrants from the Northern Triangle at the southwest border; more than 81% of those apprehended were unaccompanied minors or families, many of whom were seeking humanitarian protection (see Figure 1).

The Obama Administration determined that it was "in the national security interests of the United States" to work with Central American governments to improve security, strengthen governance, and promote economic prosperity in the region.3 Accordingly, the Obama Administration launched a new, whole-of-government U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and requested significant increases in foreign assistance to implement the strategy, primarily through the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Congress has appropriated nearly $2.6 billion in aid for the region since FY2016 but has required the Northern Triangle governments to address a series of concerns prior to receiving U.S. support.

The Trump Administration initially maintained the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America while adjusting the initiative to place more emphasis on preventing illegal immigration, combating transnational crime, and generating export and investment opportunities for U.S. businesses.4 The Administration has also sought to scale back U.S. assistance to Central America. Congress has rejected some of the Administration's proposed reductions, but annual assistance for the region has declined by nearly 30% since FY2016 (see Table 5).

The future of the Central America strategy is now in question, however, as the Trump Administration announced in March 2019 that it intends to end U.S. foreign assistance programs in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The announcement came after more than a year of threats from President Trump to cut off assistance to the Northern Triangle due to the continued northward flow of migrants and asylum-seekers from the region. Some Members of Congress have objected to the Administration's abrupt policy shift and have introduced legislation that would restrict the Administration's ability to transfer funds away from the region. The decisions made by the 116th Congress could play a crucial role in determining the direction of U.S. policy toward Central America in the coming years.

This report examines the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, including its formulation, objectives, funding, and relationship to the Alliance for Prosperity plan put forward by the Northern Triangle governments. The report also analyzes the preliminary results of the strategy and several policy issues that the 116th Congress may assess as it considers the future of U.S. policy in Central America. These issues include the potential implications of terminating U.S. assistance to the Northern Triangle; the extent to which Central American governments are addressing their domestic challenges; the utility of conditions placed on assistance to the region; and how changes in U.S. immigration, trade, and drug control policies could affect conditions in the region.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) Graphics. Notes: The "Northern Triangle" countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) are pictured in orange. |

U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America

Background and Formulation

Central America is a diverse region that includes the Northern Triangle nations of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, which are facing acute economic, governance, and security challenges; the former British colony of Belize, which is stable politically but faces a difficult economic and security situation; Nicaragua, which has comparatively low levels of crime but a de facto single-party government and high levels of poverty; and Costa Rica and Panama, which have comparatively prosperous economies and strong institutions but face growing security challenges (see Table 1).5 Given the geographic proximity of the region (see Figure 2), the United States has historically maintained close ties to Central America and played a prominent role in the region's political and economic development. It has also provided assistance to Central American nations designed to counter perceived threats to the United States, ranging from Soviet influence during the Cold War to illicit narcotics and irregular migration today.

|

People |

Geography |

Economy |

Leadership |

|||

|

Population (2018 est.) |

Land Area |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP, 2018 est.) |

Head of Government |

|||

|

Belize |

0.4 million |

22,806 |

|

Prime Minister Dean Barrow |

||

|

Costa Rica |

5.0 million |

51,060 |

|

President Carlos Alvarado |

||

|

El Salvador |

6.4 million |

20,721 |

|

President Nayib Bukele |

||

|

Guatemala |

16.8 million |

107,159 |

|

President Jimmy Morales |

||

|

Honduras |

9.2 million |

111,890 |

|

President Juan Orlando Hernández |

||

|

Nicaragua |

6.3 million |

119,990 |

|

President Daniel Ortega |

||

|

Panama |

4.1 million |

74,340 |

|

President Juan Carlos Varela |

Sources: Population estimates from U.N. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2018, March 2019; land area data from Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook, 2019; GDP estimates from International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook Database April 2019, April 9, 2019.

Note: President-elect Laurentino Cortizo of Panama is scheduled to take office on July 1, 2019.

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America is the latest in a series of U.S. efforts over the past 20 years designed to produce sustained improvements in living conditions in the region. During the Administration of President George W. Bush, U.S. policy toward Central America primarily focused on boosting economic growth through increased trade. The George W. Bush Administration negotiated the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) and the U.S.-Panama Free Trade Agreement.6 It also awarded Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador $851 million of Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) aid intended to improve productivity and connect individuals to markets.7

U.S. policy toward Central America shifted significantly near the end of the George W. Bush Administration to address escalating levels of crime and violence in the region. The George W. Bush Administration launched a security assistance package for Mexico and Central America known as the Mérida Initiative in FY2008, and the Obama Administration rebranded the Central America portion of the aid package as the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) in FY2010. Congress appropriated nearly $1.2 billion in aid between FY2008 and FY2015 to provide Central American partners with equipment, training, and technical assistance to improve narcotics interdiction and disrupt criminal networks; strengthen the capacities of Central American law enforcement and justice sector institutions; and support community-based crime and violence prevention efforts in the region.8

By the beginning of President Obama's second term, the Administration had concluded that although the resources provided through MCC, CARSI, and other U.S. initiatives had "contributed to localized gains and proof-of-concept policy examples," they had "not yielded sustained, broad-based improvements" in Central America.9 As a result, the Obama Administration had already begun to develop a new strategy for U.S. policy in Central America when an unexpected surge of unaccompanied minors and families from the Northern Triangle began to arrive at the U.S. border in 2014. The new strategy was approved by the National Security Council in August 2014 and became technically binding on all U.S. agencies in September 2014.10 Congress directed the Trump Administration to review and revise the strategy, but the updated version, released in August 2017, maintains the objectives and sub-objectives that the Obama Administration approved in 2014.11

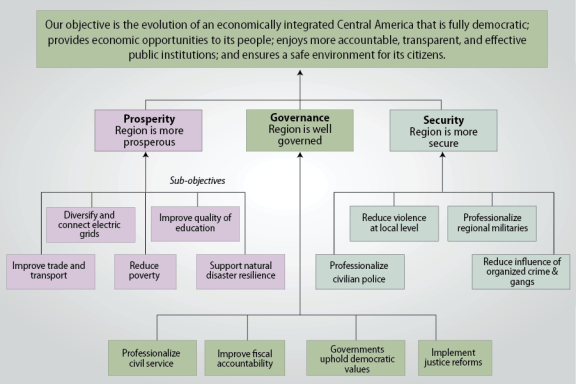

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America is intended to take a broader, more comprehensive approach than previous U.S. initiatives in the region. Its stated objective is "the evolution of an economically integrated Central America that is fully democratic; provides economic opportunities to its people; enjoys more accountable, transparent, and effective institutions; and ensures a safe environment for its citizens."12 Whereas other U.S. efforts over the past 20 years generally emphasized a single objective, such as economic growth or crime reduction, the current strategy is based on the premise that prosperity, security, and governance are "mutually reinforcing and of equal importance."13

The current strategy also prioritizes interagency coordination more than previous initiatives. Many analysts criticized CARSI as a collection of "stove-piped" programs, with each U.S. agency implementing its own activities and pursuing its own objectives, which sometimes conflicted with those of other agencies, international donors, or regional partners.14 The U.S. Strategy for Engagement is a whole-of-government effort that provides an overarching framework for all U.S. government interactions in Central America. While U.S. agencies continue to carry out a wide range of programs, the strategy is intended to ensure their efforts—and the messages they deliver to partners in the region—are coordinated. The strategy also seeks to combine U.S. resources with those of other donors and ensure that Central American governments are committed to carrying out complementary reforms.

Three Lines of Action

To achieve its objectives, the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America supports activities grouped under three overarching lines of action:

- 1. promoting prosperity and regional integration,

- 2. strengthening governance, and

- 3. improving security.

Promoting Prosperity and Regional Integration

With the exceptions of Costa Rica and Panama, the countries of Central America are among the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. Land ownership and economic power have historically been concentrated in the hands of a small group of elites, leaving behind a legacy of extreme inequality that has been exacerbated by gender discrimination and the social exclusion of ethnic minorities. Although the adoption of market-oriented economic policies in the 1980s and 1990s produced greater macroeconomic stability and facilitated the diversification of Central America's once predominantly agricultural economies, the economic gains have not translated into improved living conditions for many of the region's residents. Central America is the midst of a demographic shift in which the working age population, as a proportion of the total population, has grown significantly and is expected to continue growing in the coming decades. Although this presents a window of opportunity to boost economic growth, the region is failing to generate sufficient employment to absorb the growing labor supply (see Table 2).

|

Per Capita Income |

Poverty |

Economic Growth Rate |

Youth Disconnection |

||||||||

|

GDP per Capita (2018 est.) |

% of Population Living on less than $5.50 per day (2017)a |

Annual % Growth in GDP (2018 est.) |

% of Youth Aged 15-24 not in Employment, Education, or Training (2017)b |

||||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

Sources: Per capita income and economic growth data from the IMF, World Economic Outlook Database April 2019, April 9, 2019; poverty data from the World Bank DataBank, accessed in June 2019; youth disconnection data from the International Labour Organization (ILO), ILOSTAT, accessed in June 2019.

a. Poverty data use 2011 international prices. Data from 2014 for Guatemala and Nicaragua.

b. Youth disconnection data from 2018 for Costa Rica and 2012 for Nicaragua.

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America seeks to address these challenges through a variety of actions designed to promote prosperity and regional integration. The strategy aims to facilitate increased trade by helping the region take advantage of the opportunities provided by CAFTA-DR and other trade agreements. For example, USAID seeks to strengthen the capacities of regional organizations, including the Central America Integration System,15 to analyze, formulate, and implement regional trade policies.16 Likewise, the Department of Commerce is providing training and technical assistance intended to improve customs and border management and facilitate trade.17

The strategy also seeks to diversify and connect electric grids in Central America to bring down the region's high electricity costs, which are a drag on economic growth. For example, the State Department's Bureau of Energy Resources aims to strengthen the Central American power market and regional transmission system and to enhance sustainable energy financing mechanisms to increase energy trade and attract investment in energy infrastructure.18 Similarly, USAID is working with regional governments to develop uniform procurement processes and transmission rights as well as regulations to facilitate investment in renewable power generation projects.19

Other activities carried out under the Central America strategy aim to reduce poverty in the region and to help those living below the poverty line meet their basic needs. In Honduras, for example, USAID supports a multifaceted food security program designed to reduce extreme poverty and chronic malnutrition by helping subsistence farmers diversify their crops and increase household incomes. The program is introducing farmers to new crops, technologies, and sanitary processes intended to increase agricultural productivity, improve farming practices and natural resource management, and enable farmers to enter into business relationships and export their products.20

Facilitating access to quality education is another way in which the strategy seeks to promote prosperity in Central America. For example, USAID funds basic education programs in Nicaragua, including efforts to improve teacher training and student reading performance.21 In El Salvador, USAID seeks to develop partnerships between academia and the private sector and to better link tertiary education with labor-market needs. Among other activities, USAID is providing support for career centers, internship programs, and academic programs in priority economic sectors.22

Finally, the Central America strategy seeks to build resiliency to external shocks, such as the drought and coffee fungus outbreak that have devastated rural communities in recent years. For instance, USAID is working with communities in the Western Highlands of Guatemala to reduce the region's vulnerability to climate change. USAID has supported efforts to increase access to climate information to inform community decisions, strengthen government capacity to address climate risks, and disseminate agricultural practices that are resilient to climate impacts.23

Strengthening Governance

A legacy of conflict and authoritarian rule has inhibited the development of strong democratic institutions in most of Central America. The countries of the region, with the exception of Costa Rica and Belize, did not establish their current civilian democratic regimes until the 1980s and 1990s, after decades of political repression and protracted civil conflicts.24 Although every Central American country now holds regular elections, several have been controversial, and other elements of democracy, such as the separation of powers, remain only partially institutionalized. Moreover, failures to reform and dedicate sufficient resources to the public sector have left many Central American governments weak and susceptible to corruption. As governments in the region have become embroiled in scandals and have struggled to address citizens' concerns effectively, popular support for democracy has declined (see Table 3).

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America seeks to strengthen governance in the region in a variety of ways. It calls for the professionalization of Central American civil services to improve the technical competence of government employees, depoliticize government institutions, and ensure continuity across administrations. In El Salvador, for example, USAID is supporting civil society efforts to advocate for civil service reforms and the implementation of merit-based systems.25

|

Political Rights and Civil Liberties |

Government Effectiveness |

Public-Sector Corruption |

Satisfaction with Democracy |

|||||

|

Freedom House Score and Classification; 0-100, Least Free to Most Free (2018) |

Percentile Rank Globally; 0-100, Least Effective to Most Effective (2017) |

Perceptions; 0-100, Highly Corrupt to Very Clean (2018) |

% of Population Satisfied with How Democracy Functions in Their Country (2018) |

|||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

Sources: Political rights and civil liberties data from Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2019, February 4, 2019; government effectiveness data from World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2018; public sector corruption data from Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2018, January 29, 2019; satisfaction with democracy data from Corporación Latinobarómetro, Informe 2018, November 9, 2018.

The strategy also seeks to improve Central American governments' capacities to raise revenues while ensuring public resources are managed responsibly. For example, the Department of the Treasury is providing technical assistance to Guatemala's Ministry of Finance intended to improve treasury management operations and develop an investment policy to ensure financial resources are used efficiently and transparently.26 At the same time, USAID is training Guatemalan civil society organizations about transparency laws to strengthen the organizations' capacities to hold the government accountable.27

Other activities are designed to ensure governments in the region uphold democratic values and practices, including respect for human rights. For example, in Nicaragua, where President Daniel Ortega's government has moved to repress all dissent, USAID has supported independent media as well as civil society organizations working to promote and defend democracy.28 The State Department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) works throughout the region to support human rights defenders and civil society organizations that face threats and attacks as a result of their work. DRL assistance helps individuals avoid or mitigate threats, withstand attacks, and continue advocacy efforts domestically and internationally.29

Finally, the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America seeks to improve governance in the region by advancing justice sector reforms designed to decrease impunity. The State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) is providing training and technical assistance to prosecutors, judges, and other justice sector actors on issues such as case management and justice sector administration. INL is also providing specialized training and equipment designed to strengthen forensic capabilities, internal affairs offices, and investigative skills in the region. Moreover, INL is partially funding the operations of the U.N.-backed International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG by its Spanish acronym) and the Organization of American States (OAS)-backed Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH by its Spanish acronym), which assist Guatemalan and Honduran prosecutors in the investigation and prosecution of complex corruption cases.30

Improving Security

Violence has long plagued Central America, and Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras continue to have some of the highest homicide rates in the world. Common crime is also widespread. A number of interrelated factors have contributed to the poor security situation, including high levels of poverty, fragmented families, and a lack of legitimate employment opportunities, which leave many youth in the region susceptible to recruitment by gangs or other criminal organizations. In addition, the region serves as an important drug-trafficking corridor due to its location between cocaine-producing countries in South America and consumers in the United States. Heavily armed and well-financed transnational criminal organizations have sought to secure trafficking routes through Central America by battling one another and local affiliates and seeking to intimidate and infiltrate government institutions. Security forces and other justice sector institutions in the region generally lack the personnel, equipment, and training necessary to respond to these threats and have struggled with systemic corruption. As a result, most crimes are committed with impunity (see Table 4).

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America aims to improve security in the region in a number of ways, including through the professionalization of civilian police forces. For example, INL is carrying out a number of activities designed to improve the quality and strengthen the capacity of the Honduran National Police. Among other activities, INL is supporting efforts to vet police officers, improve police academy curricula and training, and enhance police engagement with civil society.31 U.S. assistance has also funded regional efforts to employ intelligence-led policing, such as the expansion of the comparative statistics (COMPSTAT) model, which allows real-time mapping and analysis of criminal activity.32

The strategy also expands crime and violence prevention efforts. USAID and INL have adopted a "place-based" approach that integrates their respective prevention and law enforcement interventions in the most violent Central American communities. USAID interventions include primary prevention programs that work with communities to create safe spaces for families and young people, secondary prevention programs that identify the youth most at risk of engaging in violent behavior and provide them and their families with behavior-change counseling, and tertiary prevention programs that seek to reintegrate juvenile offenders into society.33 INL interventions include primary prevention programs working to reduce gang affiliation and increase job prospects for inmates who are eligible for early release and the development of "model police precincts," which are designed to build local confidence in law enforcement by converting police forces into more community-based, service-oriented organizations.34

|

Homicide Rate |

Crime Victimization |

Rule of Law |

||||

|

Murders per 100,000 Residents (2018) |

% of Population Reporting They Were the Victim of a Crime in the Past Year (2016/17) |

Percentile Rank Globally; 0-100, Weakest to Strongest (2017) |

||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

Sources: Homicide rates from Chris Dalby and Camilo Carranza "Insight Crime's 2018 Homicide Round-Up," Insight Crime, January 22, 2019; and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, Observatorio de la Violencia, "Muertos por Homicidio; Enero a Diciembre 2018, Datos Preliminares," 2019; crime victimization data from Mollie J. Cohen, Noam Lupu, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister (eds.), Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2016/17, Vanderbilt University, Latin American Public Opinion Project, August 2017; rule-of-law data from World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2018.

Note: The homicide rate is not available for Nicaragua, where government repression led to more than 300 deaths in 2018 according to human rights organizations. In 2017, Nicaragua registered 431 total murders and a homicide rate of 7 per 100,000.

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America also continues long-standing U.S. assistance designed to professionalize regional armed forces. The strategy aims to encourage Central American militaries to transition out of internal law enforcement roles, strengthen regional defense cooperation, and enhance respect for human rights and civilian control of the military.35 U.S. support for regional militaries also aims to increase their capabilities and strengthen military-to-military relationships. Central American armed forces personnel have received training on topics such as intelligence, defense acquisition, and search and rescue planning at military institutions in the United States.36

In addition, the strategy seeks to reduce the influence of organized crime and gangs. Some U.S. assistance is designed to extend the reach of the region's security forces. For example, the U.S. government is helping Panama's national border service deploy tactical mobility vehicles and sustain fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft to protect its maritime and land borders.37 INL is using other U.S. assistance to maintain specialized law enforcement units that are vetted by, and work with, U.S. personnel to investigate and disrupt the operations of transnational gangs and organized crime networks.38

Congressional Funding

Congress has appropriated nearly $2.6 billion for efforts under the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America. This figure includes $750 million in FY2016, $684.8 million in FY2017, an estimated $614.5 million in FY2018, and an estimated $527.6 million in FY2019 (see Table 5 and the Appendix).39 The State Department and USAID have allocated the vast majority of the aid to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, including at least 75% of the funding appropriated in FY2016 and FY2017.40 Congress has placed strict conditions on aid to those three countries, however, requiring the Northern Triangle governments to address a range of concerns to receive assistance (see "Conditions on Assistance," below). Due to those legislative requirements, delays in the budget process, and congressional holds, assistance has been slow to arrive in the region.

The Trump Administration has requested $445 million to continue implementing the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America in FY2020. If enacted, aid to the region would decline by 16% compared to the FY2019 estimate. Nevertheless, assistance would remain above the pre-strategy average of $376 million between FY2010 and FY2014.41 The House Appropriations Committee reported the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2020, H.R. 2839 (incorporated into H.R. 2740), in May 2019. The bill would appropriate $540.9 million for the Central America strategy in FY2020, which is about $96 million more than the Administration requested. The Senate Appropriations Committee has not yet marked up its annual foreign aid appropriations bill.

To date, Congress has appropriated all funds for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America to the State Department and USAID, with the exception of $2 million appropriated to the Overseas Private Investment Corporation in FY2016 and two $10 million transfers designated for the Inter-American Foundation in FY2018 and FY2019. Nevertheless, many other U.S. agencies are carrying out programs intended to advance the objectives of the strategy using their own resources and/or funds transferred from the State Department and USAID. The other agencies involved include the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Commerce, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Justice, the Department of Labor, the Department of the Treasury, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency.

Table 5. Funding for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America by Country: FY2016-FY2020

(appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 (estimate) |

FY2019 (estimate) |

FY2020 (request) |

% Change 2018-2020 |

|||||||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

CARSI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Other Regional Assistance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, Fiscal Years 2018-2020, available at https://www.state.gov/plans-performance-budget/international-affairs-budgets/; and H.Rept. 116-9.

Notes: CARSI = Central America Regional Security Initiative. "Other Regional Assistance" includes assistance appropriated or requested for the entire Central American region through funding accounts such as the State Department's Western Hemisphere Regional program, USAID's Central America Regional program, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the Inter-American Foundation. The State Department does not consider health assistance provided through USAID's Central America Regional program to be part of the strategy.

a. For FY2019, Congress appropriated most assistance for Central America as regional aid, giving the State Department flexibility in allocating the resources among the seven nations of the isthmus.

b. H.Rept. 116-9 stipulates that $32.5 million of CARSI assistance is to be allocated to Costa Rica.

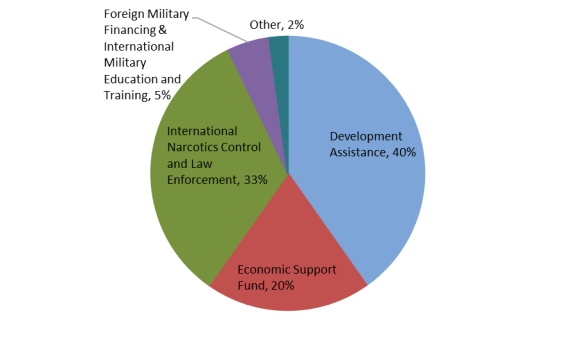

Although many of the activities supported by the Central America strategy are not new, higher levels of assistance have allowed the U.S. government to significantly scale up programs focused on prosperity and governance and expand ongoing security efforts. For FY2016-FY2019, Congress allocated funding for the Central America strategy in the following manner:

- 40% was appropriated through the Development Assistance account, which is designed to foster sustainable, broad-based economic progress and social stability by supporting long-term projects in areas such as democracy promotion, economic reform, agriculture, education, and environmental protection.

- 33% was appropriated through the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement account, with the funds roughly evenly divided between programs to support law enforcement and programs designed to strengthen other justice sector institutions.

- 20% was appropriated through the Economic Support Fund account, which funds USAID crime and violence prevention programs as well as efforts to promote economic reform and other more traditional development projects.

- 5% was appropriated through the Foreign Military Financing and International Military Education and Training accounts, which provide equipment and personnel training to regional militaries (see Figure 4).

|

Figure 4. Funding for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America by Foreign Assistance Account: FY2016-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, Fiscal Years 2018-2020, available at https://www.state.gov/plans-performance-budget/international-affairs-budgets/; and H.Rept. 116-9. Notes: "Other" includes funding appropriated through the Global Health Programs account (2%); the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (0.1%); and the Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related programs account (0.1%). |

Conditions on Assistance

Congress has placed strict conditions on assistance to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras in each of the foreign aid appropriations measures enacted since FY2016 in an attempt to bolster political will in the region and improve the effectiveness of U.S. programs. For example, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) stipulated that 25% of the "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" could not be obligated until the Secretary of State certified that each government was

- informing its citizens of the dangers of the journey to the southwest border of the United States;

- combating human smuggling and trafficking;

- improving border security, including preventing illegal migration, human smuggling and trafficking, and trafficking of illicit drugs and other contraband; and

- cooperating with U.S. government agencies and other governments in the region to facilitate the return, repatriation, and reintegration of illegal migrants arriving at the southwest border of the United States who do not qualify for asylum, consistent with international law.

The State Department certified that all three countries met those conditions in FY2016, FY2017, and FY2018, issuing the most recent certifications in August 2018.42

The act also stipulated that another 50% of the "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" could not be obligated until the Secretary of State certified the each government was

- working cooperatively with an autonomous, publicly accountable entity to provide oversight of the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle in Central America;43

- combating corruption, including investigating and prosecuting current and former government officials credibly alleged to be corrupt;

- implementing reforms, policies, and programs to improve transparency and strengthen public institutions, including increasing the capacity and independence of the judiciary and the Office of the Attorney General;

- implementing a policy to ensure that local communities, civil society organizations (including indigenous and other marginalized groups), and local governments are consulted in the design, and participate in the implementation and evaluation of, activities of the [Alliance for Prosperity] that affect such communities, organizations, and governments;

- countering the activities of criminal gangs, drug traffickers, and organized crime;

- investigating and prosecuting in the civilian justice system government personnel, including military and police personnel, who are credibly alleged to have violated human rights, and ensuring that such personnel are cooperating in such cases;

- cooperating with commissions against corruption and impunity and with regional human rights entities;

- supporting programs to reduce poverty, expand education and vocational training for at-risk youth, create jobs, and promote equitable economic growth, particularly in areas contributing to large numbers of migrants;

- implementing a plan that includes goals, benchmarks, and timelines to create a professional, accountable civilian police force and end the role of the military in internal policing, and make such plan available to the Department of State;

- protecting the right of political opposition parties, journalists, trade unionists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists to operate without interference;

- increasing government revenues, including by implementing tax reforms and strengthening customs agencies; and

- resolving commercial disputes, including the confiscation of real property, between United States entities and such government.

The State Department issued certifications related to those conditions for all three countries in FY2016 and FY2017 but has not yet certified any of the countries for FY2018.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) maintained all 16 of those conditions, with some slight variations in wording. However, it consolidated the two separate certification requirements attached to 75% of assistance for the central governments into a single certification requirement attached to 50% of assistance for the central governments.44 The State Department has not issued any certifications for FY2019.

Relationship to the Alliance for Prosperity

Many observers have confused the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America with the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle, which was drafted with technical assistance from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and announced by the Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran governments in September 2014. Originally envisioned as a five-year, $22 billion initiative, the Alliance for Prosperity aims to accelerate structural changes in the Northern Triangle that would create incentives for people to remain in their own countries. It includes four primary objectives and strategic actions to achieve them:

- 1. Stimulate the productive sector, by supporting strategic sectors (such as textiles, agro-industry, light manufacturing, and tourism); creating special economic zones to attract new investment; modernizing and expanding infrastructure; deepening regional trade and energy integration; and supporting the development of micro, small, and medium enterprises and their integration into regional production chains.

- 2. Develop human capital, by improving access to, and the quality of, education and vocational training; expanding access to health care and adequate nutrition; expanding social protection systems, including conditional cash transfer programs for the most vulnerable; and strengthening protection and reintegration mechanisms for migrants.

- 3. Improve public safety and access to justice, by investing in violence prevention programs; ensuring schools are safe spaces; furthering the professionalization of the police, including through the adoption of community policing practices; enhancing the capacity of investigators and prosecutors; and strengthening prison systems.

- 4. Strengthen institutions and promote transparency, by improving tax administration and revenue collection; professionalizing human resources; strengthening government procurement processes; and increasing budget transparency and access to public information.45

The Northern Triangle governments collectively allocated approximately $7.2 billion for the Alliance for Prosperity from 2016 to 2018 (see Table 6). They have also budgeted $2.8 billion for the initiative in 2019, though final allocations may be lower given that planned funding significantly exceeded actual funding in prior years. The resources allocated to the initiative have included government revenues as well as loans from the IDB and other international financial institutions. About 39% of the funds budgeted for the Alliance for Prosperity have been dedicated to developing human capital, 36% to stimulating the productive sector, 19% to improving public security and access to justice, and 7% to strengthening institutions and promoting transparency.46 Some analysts argue that the Alliance for Prosperity should focus more on the region's most pressing challenges, such as reducing the size of the informal economy, and that the funds allocated to the plan could be better targeted toward the communities most in need of support.47

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 (planned) |

Total |

||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: "Montos Presupuestados y Ejecutados Alineados al PAPTN," document provided to CRS by the Inter-American Development Bank, June 2019.

Note: 2018 data for Honduras reflects planned funding rather than final allocations.

Although the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and the Alliance for Prosperity have broadly similar objectives and fund complementary efforts, they prioritize different activities. Whereas the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America is designed to advance U.S. interests in all seven nations of the isthmus, the Alliance for Prosperity represents the agendas of the three Northern Triangle governments. For example, the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America devotes significant funding to efforts intended to strengthen the capacity of civil society groups, which—to date—have played relatively minor roles in the Alliance for Prosperity. Similarly, the Alliance for Prosperity has partially focused on large-scale infrastructure projects, which are not funded by the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America.48

Preliminary Results

Although the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America was adopted nearly five years ago and Congress first appropriated funding for the strategy more than three and a half years ago, it is too early to assess the full impact of the initiative. Due to delays in the budget process, certification requirements, and congressional holds, approximately 80% of the funding for the Central America strategy that Congress appropriated for FY2016 was obligated (i.e., agencies entered into contracts or submitted purchase orders for goods or services) from March to September 2017.49 Consequently, implementation of the strategy has been under way for less than two years.

The State Department and USAID have selected 39 performance indicators to track progress toward each sub-objective of the strategy. Some of the metrics measure outputs, such as the number of civilian police trained by U.S. personnel, and others measure outcomes, such as the percentage of citizens in the region who trust the police. In FY2018, U.S. agencies reportedly met or exceeded their targets on 14 indicators while falling short on eight. INL apparently did not establish targets for the other 17 indicators. The State Department's most recent monitoring and evaluation report, issued in May 2019, does not include any targets for FY2019 since the Administration announced its intention to end foreign assistance programs in the Northern Triangle.50

Many activities funded by the Central America strategy build upon previous U.S. assistance efforts that have proven successful. For example, USAID is expanding its community-based crime and violence prevention programs throughout the region. A three-year impact evaluation, published in 2014, found that communities where such programs were implemented reported 19% fewer robberies, 51% fewer extortion attempts, and 51% fewer murders than would have otherwise been expected based on trends in similar communities.51 USAID is also scaling up rural development efforts in the Northern Triangle. Since 2011, the agency's agriculture programs have reportedly lifted approximately 90,000 Hondurans out of extreme poverty, leading the Honduran government to invest $56 million to replicate the model.52

Although country-level indicators measure factors outside the control of the U.S. government, the State Department and USAID assert that U.S. programs can contribute to nationwide improvements over the longer term.53 The most recent statistics available suggest the Northern Triangle nations, which have received the vast majority of U.S. assistance, have achieved mixed results in recent years.

- Security conditions have improved in some respects, as homicide rates declined by 51% in El Salvador, 27% in Guatemala, and 32% in Honduras from 2015 to 2018.54 Nevertheless, many individuals continue to feel insecure, and the percentage of individuals reporting they were victims of crime increased in all three Northern Triangle nations between 2014 and 2017.55

- Economic growth has remained steady since 2014, averaging 2.3% per year in El Salvador, 3.5% in Guatemala, and 3.9% in Honduras.56 The stable macroeconomic situation has not translated into better living conditions for many residents, however, as national poverty rates remain relatively unchanged in all three countries.57

- Attorneys general in all three Northern Triangle countries, with the backing of CICIG in Guatemala and MACCIH in Honduras, have taken on high-profile corruption cases that have implicated presidents, cabinet ministers, and legislators. Those efforts to improve governance could be undermined or even reversed, though, as they face considerable opposition from political and economic elites in the region.58 Moreover, Freedom House has documented erosions in political rights and/or civil liberties in all three Northern Triangle nations since 2014.59

Policy Issues for Congress

Congress may examine a number of policy issues as it deliberates on potential changes to the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and future appropriations for the initiative. These issues include the potential implications of terminating U.S. assistance to the Northern Triangle; the extent to which Central American governments are demonstrating the political will to undertake domestic reforms; the utility of the conditions placed on assistance to Central America; and how changes in U.S. immigration, trade, and drug control policies could affect U.S. objectives in the region.

Potential Implications of Terminating Assistance to the Northern Triangle

As noted above, the Trump Administration announced in March 2019 that it intends to end foreign assistance programs for El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras due to the continued northward flow of migrants and asylum-seekers from the Northern Triangle. Although the Administration has yet to provide details of its plans, the State Department has indicated that it intends to reprogram approximately $450 million in FY2018 appropriations.60 That total appears to include nearly all of the bilateral assistance appropriated for El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, as well as the portion of CARSI assistance that the State Department and USAID intended to allocate to the Northern Triangle. In May 2019, however, Attorney General William Barr announced that some assistance for law enforcement in the Northern Triangle would continue.61 The Administration is also reviewing grants funded with FY2017 appropriations. It remains unclear how the President's decision may affect assistance appropriated in FY2019 or if the Administration intends to revise its FY2020 budget proposal, which requested $445 million for Central America, including at least $180 million for the Northern Triangle.

The Northern Triangle governments have reacted to the Trump Administration's announcement with a mixture of frustration and concern. Salvadoran officials noted that joint security efforts had made significant progress over the past three years and that the improvements appeared to have contributed to a decline in Salvadorans seeking entry into the United States.62 Similarly, the Honduran government expressed irritation with the "contradictory policies" of the U.S. government, noting that President Juan Orlando Hernández had just hosted then-Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen in Tegucigalpa, where they signed a new security cooperation agreement.63 Despite those frustrations, all three Northern Triangle governments issued a joint statement warning their citizens about the dangers of irregular migration and reaffirming their commitments to combatting human trafficking and associated offenses.64

The Northern Triangle governments' joint statement suggests that they are likely to continue working with the U.S. government while it reassesses assistance to the region. While the prospect of losing aid could pressure some governments into bolstering their efforts to address U.S. concerns, the decision could also lead some officials to question the reliability of the United States and begin to seek out other international partners. The president of the Salvadoran Congress, for example, reportedly responded to the potential aid termination by noting that China is offering to cooperate with the country.65 An extended suspension of U.S. assistance could incentivize the region to further diversify its foreign and trade relationships.

An aid termination would likely not have a major impact on economies in the region, especially if it were short-lived. In 2017, U.S. assistance was equivalent to about 0.3% of GDP in Guatemala, 0.5% of GDP in El Salvador, and 0.8% of GDP in Honduras.66 If U.S.-funded social assistance programs shut down, however, the impact would disproportionately affect the marginalized communities where U.S. development efforts are concentrated. Aid organizations argue that the loss of U.S. support could accelerate out-migration from such areas.67

Ending U.S. assistance could also lead the Northern Triangle governments to scale back security cooperation with the United States. In 2017, U.S. assistance was equivalent to about 2% of government spending in El Salvador and 3% of government spending in Guatemala and Honduras.68 The Northern Triangle governments would likely prioritize domestic concerns if they had to decide whether to assume financial responsibility for programs previously funded by the United States. An increased focus on domestic matters could mean less focus on transnational issues, such as migrant smuggling and drug trafficking. For example, without continued U.S. funding, governments could disband some of the specialized units established by U.S. law enforcement agencies and reassign their personnel to focus on other issues.

In addition to those socio-economic and security concerns, the Northern Triangle is at serious risk of backsliding with respect to governance and rule of law. U.S. assistance has offered crucial technical and diplomatic support to prosecutors combating high-level corruption, allowing them to take on unprecedented cases in recent years. Their tentative progress has generated fierce backlash from political and economic elites who benefit from the status quo.69 Terminating U.S. assistance could undercut U.S. allies within the Northern Triangle governments and empower the sectors most resistant to change.

Although many Members of Congress have expressed concerns about the Administration's decision to end foreign assistance programs in the Northern Triangle, Congress appears to have provided the President with significant discretion to do so. As noted previously, Section 7045(a) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) requires the State Department to withhold 75% of assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras until the Secretary of State certifies that those governments are addressing 16 congressional concerns. It also empowers the Secretary of State to suspend those funds and reprogram them elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean if he/she determines the governments have made "insufficient progress." It appears as though the Administration could make additional cuts using the broad transfer and reprogramming authorities granted in annual appropriations legislation and the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (22 U.S.C. §2151 et seq.).70 Administrations typically consult with the Appropriations Committees and provide detailed justifications prior to taking such actions.

If Congress thinks the Administration is using these authorities in ways that do not reflect congressional intent, it could enact legislation to restrict the Administration's ability to transfer or reprogram funding appropriated for Central America. For example, the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2020 (H.R. 2839, incorporated into H.R. 2740), would modify FY2017 (P.L. 115-31), FY2018 (P.L. 115-141), and FY2019 (P.L. 116-6) appropriations legislation to strengthen the funding directives for aid to Central America. The Central America Reform and Enforcement Act (S. 1445, Schumer) would go further, prohibiting the reprogramming of any assistance appropriated for the Northern Triangle nations since FY2016.

Congress could also consider a foreign assistance authorization for Central America to guide aid levels and priorities and reassure partners in the region that the United States is committed to a long-term effort. S. 1445 would require the Secretary of State to develop a new five-year interagency strategy to advance reforms in Central America and would authorize $1.5 billion in FY2020 to carry out certain activities in support of the new strategy. The United States-Northern Triangle Enhanced Engagement Act (H.R. 2615, Engel) would require the State Department, in coordination with other agencies, to develop five-year strategies to support inclusive economic growth, combat corruption, strengthen democratic institutions, and improve security conditions in the Northern Triangle. It would authorize $577 million for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America in FY2020, including "not less than" $490 million for the Northern Triangle.

Political Will in Central America

Although many analysts assert that Central American nations will require external support to address their challenges, they also contend that significant improvements in the region ultimately will depend on Central American leaders carrying out substantial internal reforms.71 That contention is supported by multiple studies conducted over the past decade, which have found that aid recipients' domestic political institutions play a crucial role in determining the relative effectiveness of foreign aid.72 Some scholars argue that this conclusion is also supported by the region's history:

How did Costa Rica do so much better by its citizens than its four northern neighbors since 1950? The answer, we contend, stems from the political will of Costa Rican leaders. Even though they shared the same disadvantageous economic context of the rest of Central America, Costa Rica's leaders adopted and kept democracy, abolished the armed forces, moderated income inequality, and invested in education and health over the long haul. The leaders of the other nations did not make these choices, at least not consistently enough to do the job.73

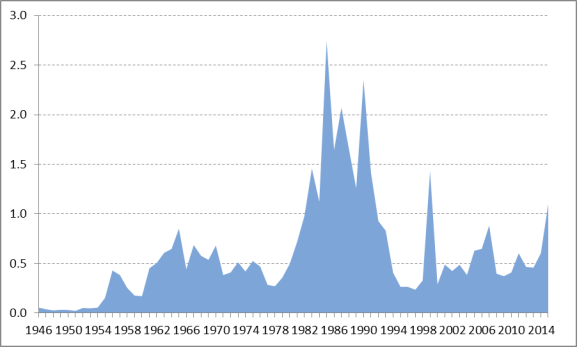

One of the underlying assumptions of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America is that "Central American governments will continue to demonstrate leadership and contribute significant resources to address challenges" if they are supported by international partners.74 Such political will cannot be taken for granted, however, given that previous U.S. efforts to ramp up assistance to Central America—including substantial increases in development aid during the 1960s under President John F. Kennedy's Alliance for Progress and massive aid flows in the 1980s during the Central American conflicts (see Figure 5 below)—were not always matched by far-reaching domestic reforms in the region.75

Over the past few years, Central American governments have demonstrated varying levels of commitment to internal reform. As discussed previously, the three Northern Triangle governments worked together to develop the Alliance for Prosperity, which includes numerous policy commitments. Among other actions, El Salvador has begun implementing a comprehensive security plan; Guatemala has adopted reforms to improve the transparency of the national tax agency, including the creation of a new internal affairs unit; and Honduras has begun to restructure the police force with new training and evaluation protocols.76 At the same time, tax collection has remained relatively flat in the region, leaving governments without the resources necessary to address chronic poverty or other challenges.77 Moreover, as noted above, elected officials in the Northern Triangle have sought to undermine the anti-corruption efforts of their attorneys general, CICIG, and MACCIH.78

|

Figure 5. U.S. Assistance to Central America: FY1946-FY2015 (obligations in billions of constant 2015 U.S. dollars) |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from USAID, U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants: Obligations and Loan Authorizations, July 1, 1945-September 30, 2015, January 10, 2017, at https://explorer.usaid.gov/reports.html. Note: Includes aid obligations from all U.S. government agencies. |

Congress could consider a number of actions to support reform efforts in the region. In addition to placing legislative conditions on aid, which is discussed in the following section (see "Aid Conditionality"), Congress could continue to offer vocal and financial support to individuals and institutions committed to change. For example, H.Rept. 116-9, notes that the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), "supports efforts to strengthen the rule of law by combating corruption and impunity in Central America" by providing $6 million for CICIG, $5 million for MACCIH, and $20 million for the attorneys general of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. The report also states that "the Secretary of State should consider the capacity, record, and commitment to the rule of law of each office" when allocating funds.

Congress could also continue to call attention to individuals in the region who seek to subvert reform efforts. For example, a reporting requirement in S.Rept. 115-282, made binding by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), required the Secretary of State to produce an assessment of grand corruption in the Northern Triangle. The report was required to include a list of senior Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran officials known, or credibly alleged, to have committed or facilitated such corruption and a description of steps taken to impose sanctions pursuant to the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (P.L. 114-328). The report, issued in May 2019, lists more than 60 current and former officials. It also notes that between January and April 2019, the State Department used its various sanctions authorities to revoke the visas of 85 individuals from the Northern Triangle suspected of corrupt acts.79

Congress could put additional pressure on corrupt individuals and attempt to deter others by enacting legislation to establish new economic sanctions regimes or by recommending sanctions pursuant to existing law. For example, the Guatemala Rule of Law Accountability Act (H.R. 1630, Torres) would direct the President to impose targeted sanctions (asset blocking and visa restrictions) against any current or former Guatemalan official who has knowingly (1) committed or facilitated significant corruption; (2) obstructed Guatemalan investigations or prosecutions of such corruption; (3) misused U.S. equipment provided to the Guatemalan military or police to combat drug trafficking or secure the border; (4) disobeyed rulings of the Guatemalan constitutional court; or (5) impeded or interfered with the work of any U.S. government agency or any institution that receives contributions from the U.S. government, including CICIG. Similarly, the United States-Northern Triangle Enhanced Engagement Act (H.R. 2615, Engel) would direct the President to impose targeted sanctions against any person the President determines to be engaged in an act of significant corruption that affects a Northern Triangle country, including corruption related to government contracts, bribery and extortion, or the facilitation or transfer of the proceeds of corruption.

Aid Conditionality

As noted previously, Congress has placed strict conditions on foreign aid for Central America in an attempt to bolster political will in the region and ensure U.S. assistance is used as effectively as possible (see "Conditions on Assistance"). Although U.S. officials acknowledge that aid restrictions give them leverage with partner governments, some argue that recent appropriations measures have included too many conditions and have withheld too much aid. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), requires the State Department to withhold 50% of "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" until the Secretary of State certifies that those governments are addressing 16 different issues of congressional concern. Some U.S. officials contend that Congress should focus on a few key priorities given the limited capacities of the Northern Triangle governments. Moreover, they assert that it requires significant time to track the Northern Triangle governments' efforts to meet the conditions and that U.S. resources would be better used overseeing implementation of the Central America strategy.

U.S. officials also argue that by subjecting "assistance for the central governments" to withholding requirements, Congress effectively prevents U.S. agencies from carrying out some programs that would advance U.S. interests and help the governments meet the conditions. For example, the State Department is required to withhold U.S. assistance to support police reform efforts until it can certify that each government is "creating a professional, accountable civilian police force and ending the role of the military in internal policing." Similarly, the State Department is required to withhold U.S. assistance to strengthen tax collection agencies until it can certify that each government is "implementing tax reforms."80 Congress could prevent such unintended consequences by waiving withholding requirements for certain types of assistance. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), for example, states that the withholding requirements on assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala "shall not apply to funds appropriated" for CICIG, MACCIH, humanitarian assistance, or food security programs.81

Additionally, U.S. officials note that withholding requirements have contributed to delays in the implementation of the Central America strategy. In FY2016, the first year Congress approved funding for the strategy, Congress enacted full-year appropriations legislation on December 18, 2015. The State Department did not issue the final certification (for Honduras), however, until September 30, 2016—the last day of the fiscal year. Due to the certification requirements, as well as delays in the budget process and congressional holds, most aid did not begin to be delivered to the region until mid-2017. Although U.S. agencies obligated some aid not subject to the withholding requirements at earlier dates, they were hesitant to commit resources to specific activities until they knew whether they would have access to the remaining funding. Similar delays have occurred during the past three fiscal years.

Nevertheless, some Members of Congress and civil society organizations have occasionally criticized the State Department for issuing certifications too quickly, particularly with regard to human rights conditions. For example, on November 28, 2017, the State Department certified that Honduras had met the conditions necessary to receive assistance appropriated for FY2017, including by taking effective steps to "protect the right of political opposition parties, journalists, trade unionists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists to operate without interference."82 The State Department issued the certification two days into Honduras's disputed presidential election, and just days before the Honduran government declared a state of emergency to suspend certain constitutional rights and human rights organizations began to document the use of excessive force by security forces to disperse opposition protests.83 Human rights groups and some Members of Congress criticized the certification, with one Honduran union leader reportedly declaring, "They're practically giving carte blanche so they can violate human rights in this country under the umbrella of the United States."84

Studies of aid conditionality have found that conditions generally fail to alter aid recipients' behavior when recipients think donors are unlikely to follow through on their threats to withhold aid.85 Members of Congress who are concerned that the State Department is issuing certifications too quickly and thereby weakening the effectiveness of human rights conditions could seek changes to the certification process. For example, Congress could set more specific and/or measureable criteria for the Northern Triangle governments to meet prior to receiving assistance. The Berta Cáceres Human Rights in Honduras Act (H.R. 1945, H. Johnson) would suspend all U.S. security assistance to Honduras and direct U.S. representatives at multilateral development banks to oppose all loans for Honduran security forces until the State Department certifies that Honduras has effectively investigated and prosecuted a series of specific human rights abuses and satisfied several other conditions.

Implications of Other U.S. Policy Changes

Given Central America's geographic proximity and close migration and commercial ties to the United States, changes in U.S. immigration, trade, and drug control policies can have far-reaching effects in the region. As Congress considers the future of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, it may also wish to evaluate how changes to other U.S. policies might support or hinder the strategy's objectives.

Immigration

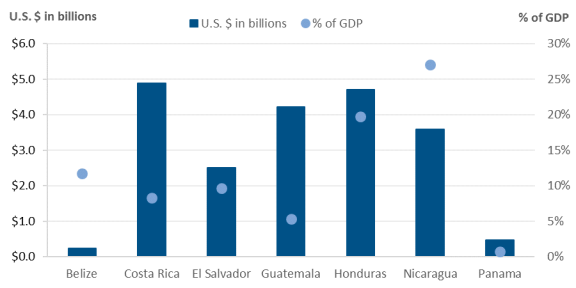

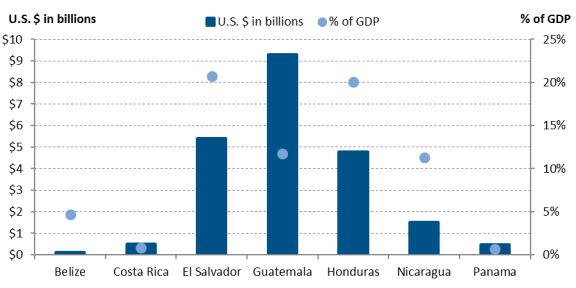

Central American nations have strong migration ties to the United States. In 2017, an estimated 3.3 million individuals born in Central America were living in the United States, including more than 1.3 million Salvadorans; 924,000 Guatemalans; 603,000 Hondurans; and 252,000 Nicaraguans.86 Those immigrant populations play crucial roles in Central American economies. Remittances from Central American migrants abroad—the vast majority (79%) of whom live in the United States87—totaled nearly $22 billion in 2018 and were equivalent to 11% of GDP in Nicaragua, 12% of GDP in Guatemala, 20% of GDP in Honduras, and nearly 21% of GDP in El Salvador (see Figure 6 below).

Many Central Americans reside in the United States in an unauthorized status, however, and are therefore at risk of being removed (deported) from the country. The Pew Research Center estimates that nearly 1.9 million (about 58%) of the Central Americans residing in the United States in 2016 were unauthorized.88 In FY2018, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) removed nearly 96,000 Central Americans, including approximately 50,000 Guatemalans, 29,000 Hondurans, and 15,000 Salvadorans.89

The Trump Administration's immigration policies could accelerate removals from the United States. Since September 2017, for example, the Administration has terminated Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which provides relief from removal, for approximately 4,500 Nicaraguans and 81,000 Hondurans who have lived in the United States since 1998 and 252,000 Salvadorans who have lived in the United States since 2001. TPS was scheduled to expire on January 5, 2019, for Nicaraguans, but it remains in place pending the resolution of a lawsuit challenging the Administration's termination decision. Lawsuits have also temporarily halted the termination of TPS for Salvadorans, scheduled for September 9, 2019, and the termination of TPS for Hondurans, scheduled for January 5, 2020.90 Although some individuals may be able to obtain another lawful status, the remainder would be subject to removal once TPS expires. In June 2019, the House passed the American Dream and Promise Act of 2019 (H.R. 6, Roybal-Allard), which would provide a path toward permanent resident status for some TPS holders.

|

|

Sources: CRS, using remittance data from each nation's central bank and GDP data from IMF, World Economic Outlook Database April 2019, April 9, 2019. |

Central American officials are concerned that increased deportations could aggravate social tensions and fuel instability in the region. Although deportees could bring new skills and financial resources back to their countries of origin, they could also displace local workers competing for scarce employment opportunities.91 In addition, increased deportations could exacerbate poverty, as some 3.5 million households in the region reportedly depend on remittances for more than half of their household income.92 During the 1990s, U.S. deportations played a key role in the spread of gang violence in Central America. Consequently, many observers are concerned that a new wave of deportations could exacerbate security challenges in the region.93 Although most Central Americans at risk of deportation today have no connections to gangs, deported youth could become vulnerable to gang recruitment.94

If deportations accelerate, Congress could help mitigate the impact on the region (and potentially reduce the likelihood of repeat migration) by appropriating increased assistance for reintegration efforts. Since FY2014, USAID has provided approximately $27 million to the International Organization for Migration to provide short-term assistance to migrants returning to the Northern Triangle and support deportees' reintegration into their communities of origin.95

Trade

Most Central American nations have close commercial ties to the United States, and they have become more integrated into U.S. supply chains since the adoption of CAFTA-DR. In 2018, U.S. merchandise trade with the seven nations of Central America totaled nearly $51.5 billion. Although Central America accounts for a small portion (1.2%) of total U.S. trade, the United States is a major market for Central American goods.96 In 2018, the value of merchandise exports to the United States was equivalent to about 10% of GDP in El Salvador, 12% of GDP in Belize, 20% of GDP in Honduras, and 27% of GDP in Nicaragua (see Figure 7).

Given the economic importance of access to the U.S. market, Central American nations have closely tracked recent developments in U.S. trade policy. Some in the region were relieved by President Trump's decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed trade agreement among 12 Asia-Pacific countries.97 The agreement would have allowed Vietnam and other nations to export apparel to the United States duty-free, which could have eliminated much of the competitive advantage now enjoyed by Central American apparel producers.98 The Salvadoran government and the Central American-Dominican Republic Apparel and Textile Council estimated that the first year of TPP implementation would have led to a 15%-18% contraction in industrial employment in the CAFTA-DR region.99 If the United States enters into a similar trade agreement in the future, Congress could consider granting Central American nations trade preferences equal to those included in the new agreement to ameliorate the shock to economies in the region.100

In October 2017, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer reportedly asserted that the Trump Administration intends to modernize trade agreements throughout Latin America.101 Central American leaders think the Administration is unlikely to prioritize the renegotiation of CAFTA-DR and the U.S.-Panama Free Trade Agreement, however, since President Trump has focused primarily on reducing U.S. trade deficits and the United States ran a $10.3 billion trade surplus with Central America in 2018.102 Nevertheless, other potential changes to trade policy, such as imposing tariffs on imports, could be detrimental to Central American economies. In 2017, the IDB estimated that if the United States increased the average tariff for imports from Central America by 20% of their value, the region's GDP would decline by 2.2-4.4 percentage points.103

Drug Control

Although illicit drug production and consumption remain relatively limited in Central America,104 the region is seriously affected by the drug trade due to its location between cocaine producers in South America and consumers in the United States. In 2017, the State Department reported that about 90% of cocaine trafficked to the United States transits through Central America, along with unknown quantities of opiates, cannabis, and methamphetamine.105 The criminal groups that move cocaine through the region receive immense profits; in 2016, a security analyst estimated that trafficking generated $700 million per year in Honduras and similar amounts in Guatemala and El Salvador.106 Violence in the region has escalated as rival criminal organizations have fought for control over the lucrative drug trade and gangs have battled to control local distribution. The illicit funds produced by drug trafficking have also fostered corruption and impunity in Central America as criminal organizations have financed political campaigns and parties; distorted markets by channeling proceeds into legitimate and illegitimate businesses; and bribed security forces, prosecutors, and judges.107

Upon the launch of the Mérida Initiative in 2008, the George W. Bush Administration pledged to reduce drug demand in the United States as part of its "shared responsibility" to address the challenges posed by transnational crime.108 The Trump Administration, like the Obama Administration before it, has reiterated that pledge, asserting that the United States "recognizes its responsibility to address the demand for illegal drugs."109 Between FY2009 and FY2019, U.S. expenditures on drug demand reduction efforts (i.e., prevention and treatment) increased from $9.2 billion to $17.3 billion and the portion of the U.S. drug control budget dedicated to demand reduction increased from $37% to 52%.110 The estimated number of individuals aged 12 or older currently using (past month use of) cocaine declined from about 1.9 million in 2008 to 1.4 million in 2011. It has climbed significantly since then, however, reaching nearly 2.2 million in 2017.111

Legislative measures to expand or improve the effectiveness of programs to reduce cocaine and other illicit drug consumption in the United States would complement efforts under the Central America strategy and would maintain the sense of "shared responsibility" that has guided U.S. relations with the region over the past decade. The 116th Congress could build on measures adopted during the 115th Congress to address substance abuse and treatment, such as the Support for Patients and Communities Act (P.L. 115-271).112 The 116th Congress could also engage in a broader reassessment of U.S. drug control policy. It may draw on the work of the recently launched Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission, authorized by the Department of State Authorities Act, Fiscal Year 2017 (P.L. 114-323), which is charged with conducting a comprehensive review of U.S. counternarcotics policies in the region.

Outlook

Congress has appropriated nearly $2.6 billion of foreign aid since FY2016 to promote prosperity, strengthen governance, and improve security in Central America. Those are difficult, long-term endeavors, however, and U.S. efforts are little more than two years into implementation. Although Central American nations have made some tentative progress in addressing long-standing challenges, the region is at serious risk of backsliding. Political and economic elites that benefit from the status quo are working to undermine anti-corruption efforts, and the Trump Administration has begun to withdraw the diplomatic pressure and foreign aid that had incentivized structural reforms. To achieve success in the medium and long terms, Central American nations would need to redouble their efforts to strengthen institutions, bolster their tax bases, and create opportunities for young people, and international donors would need to provide extensive support over an extended period. Absent such efforts, conditions are likely to remain poor in several Central American countries, contributing to political and social instability that—as demonstrated by recent migration flows—is likely to affect the United States.

Appendix. Appropriations for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America by Country and Foreign Assistance Account: FY2016-FY2020

Table A-1. FY2016 Funding for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America

(appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

DA |

GHP |

ESF |

INCLE |

NADR |

IMET |

FMF |

OPIC |

Total |

|

|

Belize |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.2 |

1.0 |

— |

1.2 |

|

Costa Rica |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.4 |

1.4 |