Introduction

Persistent annual budget deficits and a large and increasing federal debt have generated discussions over the long-term sustainability of current budget projections. Federal budget deficits declined from 9.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in FY2009 to 3.8% of GDP in FY2018.1 However, recent estimates forecast that the government will run deficits (i.e., federal expenditures will exceed revenues) in every year through FY2029. Federal debt totaled $21.516 trillion at the end of FY2018, and as a percentage of GDP (106.0%) was at its highest value since FY1947; $15.761 trillion of that debt (or 77.8% of GDP) was held by the public. This report explores distinctions in the concept and composition of deficits and debt and explains how they interact with economic conditions and other aspects of fiscal policy.

Background

What Is a Deficit?

A deficit describes one of the three possible outcomes for the federal budget.2 The federal government incurs a deficit (also known as a net deficit) when its total outgoing payments (outlays) exceed the total money it collects (revenues). If instead federal revenues are greater than outlays, then the federal government generates a surplus. A balanced budget describes the case where federal receipts equal federal expenditures.3 The size of a deficit or surplus is equal to the difference between the levels of spending and receipts. Deficits are measured over the course of a defined period of time—in the case of the federal government, a fiscal year.4

Federal budget outcomes incorporate both "on-budget" activities, which represent the majority of federal taxes and spending, and "off-budget" government activities, which include revenues and outlays from Social Security trust funds and the Postal Service. For federal credit programs, the subsidy cost of government activities is included in deficit and surplus calculations.5 The federal budget is constructed in a manner that provides for lower net deficits in more robust economic conditions, attributable to higher revenues (from taxes on increased output) and, to a smaller degree, lower spending levels (from reduced demand for programs like unemployment insurance).

The federal government incurred a deficit of $779 billion in FY2018, equivalent to 3.8% of GDP. From FY1969 to FY2018, the average net deficit equaled 2.9% of annual GDP ($587 billion in 2018 dollars). Over the FY1969-FY2018 period, the government generated a surplus on five occasions: in FY1969 and in each year from FY1998 through FY2001. In all other years, the federal government incurred a net deficit.6

What Is the Debt?

The federal debt is the money that the government owes to its creditors, which include private citizens, institutions, foreign governments, and other parts of the federal government. Debt measurements may be taken at any time and represent the accumulation of all previous government borrowing activity. Federal debt increases when there are net budget deficits, outflows made for federal credit programs (net of the subsidy costs already included in deficit calculations), and increases in intragovernmental borrowing. Federal credit programs include loans issued for college tuition payments, small business programs, and other activities the government may seek to support.7 In those cases, debt levels increase as additional loans are granted and decrease as money for such programs is repaid.

Intragovernmental debt is generated when trust funds, revolving funds, and special funds receive money from tax payments, fees, or other revenue sources that is not immediately needed to make payments. In those cases the surpluses are used to finance other government activities, and Government Account Series (GAS) securities are issued to the trust fund. GAS securities may then be redeemed when trust fund expenditures exceed revenue levels. Intragovernmental debt may be thought of as money that one part of the government owes another part.

The Department of the Treasury is responsible for managing federal debt. The primary objective of Treasury's debt management strategy is to fulfill the government's borrowing needs at the lowest cost over time.8 Treasury finances federal borrowing activities by issuing government-backed securities that generate interest payments for their owners. Treasury securities are typically sold to the public through an auction process, and have maturity periods (the length of time that they are held before repayment) of anywhere from several weeks to 30 years.9

Comparing Debt Held by the Public and Intragovernmental Debt

Federal debt may be divided into two major categories: (1) debt held by the public, which is the sum of accrued net deficits and outstanding money from federal credit programs; and (2) intragovernmental debt. As of February 28, 2019, the amount of federal debt outstanding was $22.087 trillion, with 73.6% of that debt held by the public and 26.4% held as intragovernmental debt.10 Table 1 summarizes the composition of debt held by the public and intragovernmental debt.

|

Publicly Held Debt |

Intragovernmental Debt |

|

|

Origin |

Budget deficits and the federal loan portfolio |

Federal trust fund surpluses |

|

Ownership |

Individuals and institutions (domestic and foreign); state and local governments; foreign governments |

Federal government accounts |

|

Debt outstanding |

$16.251 trillion (73.6%) |

$5.836 trillion (26.4%) |

|

Share of marketable securities |

$15.741 trillion (96.9%) |

$0.029 trillion (0.5%) |

|

Financial market presence |

Debt issuances may compete for private assets exchanged in the financial market |

Debt issuances do not appear in public markets and thus do not compete for private assets |

Source: U.S. Treasury, Monthly Statement of the Public Debt, February 2019, at http://treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/2019/opds022019.pdf.

Note: Debt values as of February 28, 2019.

Individuals, firms, the Federal Reserve, state and local governments, and foreign governments are all eligible to purchase publicly held debt. Debt may be acquired directly through the auction process, from which most publicly held debt is initially sold, or on the secondary market if the debt is deemed "marketable" or eligible for resale.11 The total amount of publicly held debt outstanding was $16.251 trillion as of February 28, 2019.

The majority of publicly held debt is marketable, and includes all Treasury Notes, Bonds, Bills, Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), and Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) issued by Treasury. Nonmarketable debt held by the public is composed of U.S. Savings Bonds, State and Local Government Securities (SLGS), and other, smaller issues. As of February 28, 2019, 96.8% of publicly held issues, or $15.741 trillion, was marketable.

Intragovernmental debt is debt where the federal government is both the creditor and the borrower. Intragovernmental debt issuances are almost exclusively nonmarketable, as marketable debt comprised only $0.029 trillion (0.5%) of the $5.836 trillion in total intragovernmental debt on February 28, 2019. The majority of nonmarketable intragovernmental debt was held by trust funds devoted to Social Security and military and federal worker retirement. Marketable intragovernmental debt is composed primarily of debt held by the Federal Financing Bank, which is a government corporation created to reduce the cost of federal borrowing.

Since intragovernmental debt is held only in government accounts, such debt cannot be accessed by institutions outside the federal government. Conversely, the bonds that finance publicly held debt activity may compete for assets in private and financial markets. Public debt issues may be a particularly attractive collateral option on the secondary market if the federal government is perceived as a safe credit risk.

Deficit and Debt Interaction

Federal deficit and debt outcomes are interdependent; budget deficits increase federal debt levels, which in turn increase future net deficits because of the need to service higher interest payments on the nation's debt. The nature of the relationship between deficits and debt varies depending on the type of debt considered. This section describes the relationship between federal deficits and debt.

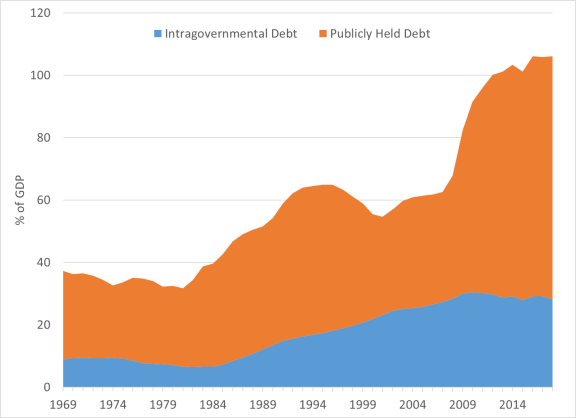

How Deficits Contribute to Debt

Budget deficits are the principal contributor to debt held by the public. To finance budget deficits, Treasury sells debt instruments. The value of those debt holdings (which include interest payments) represents the vast majority of publicly held debt. From FY1969 to FY2018, annual nominal budget deficits and surpluses of the federal government summed to $13.745 trillion; over the same period, total debt held by the public increased by $15.473 trillion.12 Publicly held debt has been the biggest determinant of historical changes in the total stock of federal debt. Figure 1 shows changes in federal debt levels from FY1969 through FY2018. Though there has been a gradual increase in intragovernmental debt in recent decades, the decline in real debt following World War II and subsequent increase in debt levels beginning in the late 1970s were each caused primarily by similar changes in the stock of publicly held debt over those time periods.

|

Figure 1. Federal Debt, FY1969-FY2018 (as a % of GDP) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Budget Office. |

How Debt Contributes to Deficits

Present borrowing outcomes affect future budgeting outcomes. Publicly held debt contributes directly to federal deficits through interest payments on debt issuances. Interest payments are made to both debt held by the public and intragovernmental debt. As the government serves as buyer and seller of intragovernmental debt, interest payments on those holdings do not affect the federal budget deficit.13 However, interest payments made on publicly held debt represent new federal spending, and are recorded in the budget as outlays when payments are made. The government incurs interest costs when it opts to finance spending through borrowing rather than through increased revenues. Net interest payments represent the amount paid from the government to debt holders in a given time period, less interest payments received for federal loan programs.14

For investors, purchasing a debt issuance represents both a loss of liquidity relative to currency holdings (money paid for the debt holding can be used immediately, while the debt issuance may only be resold on the secondary market or held until the date of maturity) and an opportunity cost (the money used for the purchase could have been spent on other items, invested elsewhere, or saved). Debt holders are compensated for those costs by receiving interest payments from Treasury on their issuances.

|

Determinants of Net Interest Payments The amount of net interest payments owed by the federal government depends on the existing stock of federal debt and the interest rate on outstanding debt instruments. The structure of the interest payments may be fixed or variable, depending on the type of debt issuance. In either case, the terms of interest are agreed to in advance of sale. Interest rates on debt vehicles are largely determined by prevailing economic conditions. Situations where the private cost of borrowing (interest rate) is high will raise interest rates on federal debt and thereby increase net interest payments. Increases in the amount of existing debt will also lead to a rise in net interest payments, as they increase the base on which a given interest rate is applied. |

From FY1969 to FY2018 net interest payments averaged 2.0% of annual GDP, equivalent to about $407 billion annually in 2018 dollars. High interest rates and increasing debt levels caused the net interest burden to peak in the 1980s and 1990s. Recent net interest payments have been lower than their long-term averages; in FY2018, net interest payments were $325 billion, or 1.6% of GDP. FY2018 payments were the product of real low interest rates and relatively high levels of real debt. Unless the federal debt is reduced, net interest payments will likely increase if interest rates shift toward their long-term averages. In its most recent forecast, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that real net interest payments will increase to 3.0% of GDP by FY2029.15

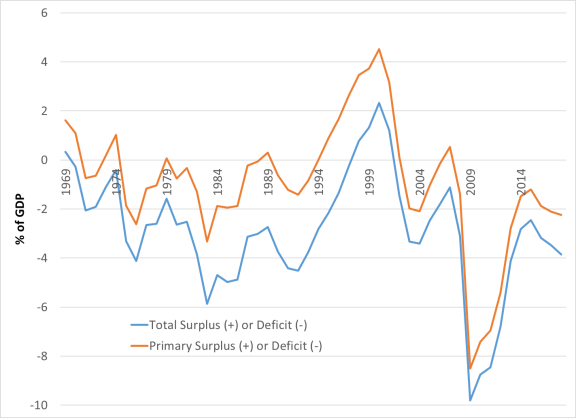

One way to measure the effect of debt on future deficits is to examine the relationship between total federal deficits and the primary deficit, which measures the balance of revenues and expenditures with net interest payments excluded. Figure 2 shows total and primary budget outcomes from FY1969 through FY2018. The gap between the total and primary outcomes in a given year is explained by net interest payments. The primary deficit averaged 0.9% of GDP from FY1969 to FY2018, as compared to the average total budget deficit of 2.9% of GDP recorded over the same time period. While the federal government recorded a budget surplus five times from FY1969 to FY2018, in nine other years it registered a primary surplus, most recently in 2007.

|

Figure 2. Total and Primary Federal Budget Outcomes, FY1969-FY2018 (as a % of GDP) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Budget Office; CRS calculations. |

Economic Theory, Deficits, and Debt: In Brief

This section provides a primer of how government deficits and debt are integrated into the larger economy in both the short and long run, and provides some ways to measure such interactions. The nature of interaction between fiscal outcomes and economic performance may have ramifications for how Congress wishes to distribute its activity both within a recession or expansion and for what fiscal targets it wishes to set in the long run.

How Deficits and Debt Contribute to the Economy: Short-Run Effects

In the short run, when economic output is assumed to be fixed, output is a function of both private and public activity. Equation (1), also known as the national accounting identity, shows the different choices that can be made with all economic output in a given time period. It states that output (Y) in a given economy is equal to the sum of private consumption (C), private investment (I), net government investment (G), and net exports (X). Put another way, equation (1) asserts that output is the sum of private consumption, private saving, and net government activity. The net government deficit, or G, is shown in equation (2) as spending (S) less revenues (R). Absent a monetary policy intervention by the Federal Reserve (which makes monetary decisions independently), G must be obtained through government borrowing, or debt.16

(1) Y = C + I + G + X

(2) G = S - R

Since the levels of output (Y) and consumption (C) in a given time period are fixed, increases in government investment (G) will reduce private investment (I), net exports (X), or some combination thereof. Government borrowing increases that reduce private investment are commonly categorized as "crowding out," and represent a shift from private investment to public investment.

Increased government borrowing that reduces net exports (generated by borrowing from foreign sources) represents an expansion of the short-term money supply, as money is being brought into the economy now at the expense of the future stock of money (as foreign borrowing is repaid). Such a fiscal expansion increases the quantity of money demanded, which drives up interest rates (or cost of borrowing).17

The federal government may choose to generate short-run budget deficits for a few reasons. Deficit financing, or payment for federal government activity at least partly through debt increases, increases the total level of spending in the economy. Most economists believe that the implementation of deficit financing can be used to generate a short-term stimulus effect, either for a particular industry or for the entire economy. In this view, increases in expenditures and tax reductions can be used to generate employment opportunities and consumer spending and reduce the intensity of stagnant economic periods.

Deficit financing is a less effective countercyclical strategy when it leads to "crowding out," or when government financing merely replaces private-sector funding instead of inducing new economic activity, and is more likely to occur in periods of robust economic growth. Deficit reduction when the economy is operating near or at full potential can help prevent the economy from overheating and avoid "crowding out" of private investment, which could have positive implications for intergenerational equity and long-term growth.

Deficit financing may also be used as part of a structurally balanced budget strategy, which alters government tax and spending levels to smooth the effect of business cycles. Smoothing budgetary changes may reduce the economic shocks deficits induce among businesses and households. Governments may also use federal deficits or surpluses to spread the payment burden of long-term projects across generations. This sort of intergenerational redistribution is one justification for the creation of long-run trust funds, such as those devoted to Social Security.

How Deficits and Debt Contribute to the Economy: Long-Run Effects

In the long run, when economic output is affected by supply-side choices, the effect of government borrowing on economic growth depends on how amounts borrowed are used relative to what would have otherwise been done with those savings (i.e., an increase in private investment or net exports) if such borrowing had not taken place. As shown in equation (3), economic growth, or the change (Δ) in output (Y), is a function (f) of the stock of labor (L, or the number of people working and hours that they work), the stock of capital (K, which includes equipment, machines, and all other nonlabor factors), and the knowledge and technological capability (A) that determines the productivity of labor and capital.

(3) ΔY= f(ΔL, ΔK, ΔA)

Assuming that the stock of labor is insensitive to fiscal policy choices, the effect of federal debt on economic growth depends on how the additional government activity affects the capital stock and productivity of labor and capital relative to what would have happened had amounts borrowed been invested privately or increased net exports. If that government activity (debt-financed spending) contributes to those factors more than the economic activity it replaced, than that debt financing will have had a positive effect on future economic growth (or potential). Alternatively, if such activity contributes less to those factors than the replaced private investment and net exports, it will reduce long-term economic potential.

Changes in federal debt levels shift economic resources across time periods, a process sometimes described as an intertemporal transfer. Federal debt issuances represent an increase in the current level of federal resources and a decrease in future federal resources. Net interest payments, or the total interest payments made by the federal government (to creditors) on borrowed money less interest payments received (from individuals and institutions borrowing from the federal government or debtors), may be thought of as the total expense associated with past federal borrowing. Those resources cannot be allocated to other government services.

Total borrowing is constrained by the money available for investment (savings in dollars) at a given point in time. This limit means that the amount of federal debt relative to output cannot increase indefinitely. The trajectory of federal debt is therefore thought to be unsustainable if debt taken as a share of output (measured in this report with gross domestic product, or GDP) rises continuously in long-term projections. This happens when growth in the stock of debt outpaces total economic growth, which can cause a variety of adverse outcomes, including reduced output, increased unemployment, higher inflation, higher private interest rates, and currency devaluation.18

Recent international experiences speak to the complexity of borrowing capacity. Both Greece and Japan experienced rapid growth in government debt in the past decade. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data on general government debt (including municipal government debt) indicate that Greek debt rose from 115% of GDP in 2006 to 189% of GDP in 2017, while Japanese debt rose from 180% of GDP to 234% of GDP over the same time period. A loss in market confidence in Greek debt led to a severe recession, with GDP contracting by 9 percentage points in 2011 and long-term interest rates reaching 22% in 2012. Japanese borrowing was viewed to be more sustainable despite being higher, with relatively flat GDP levels and long-term interest rates close to zero in recent years. Among 31 OECD countries, the United States had the fifth-largest level of general government debt (136% of GDP, including debt from state and local governments) in 2017, the most recent year for which full data are available.

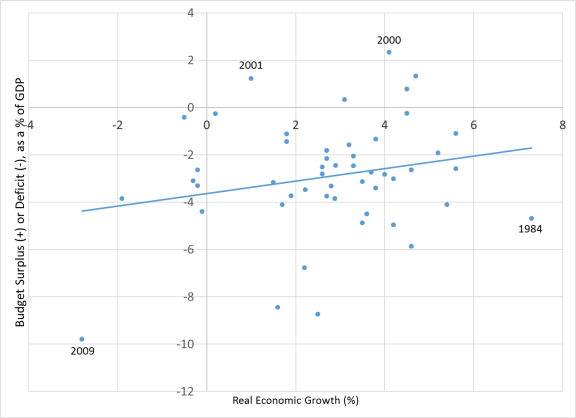

How the Economy Contributes to Deficits

The deficit's cyclical pattern can be attributed in part to "automatic stabilizers," or spending programs and tax provisions that cause the budget deficit to move in tandem with the business cycle without any change in law. More robust economic periods generally produce lower net deficits (or higher net surpluses), due to increases in receipts (from greater tax revenues) and reduced expenditures (from decreased demand for public assistance). The opposite effect occurs during recessions: as incomes and employment fall, the existing structure of the federal tax system automatically collects less revenue, and spending on mandatory income security programs, such as unemployment insurance, automatically rises. CBO estimates that the share of the deficit attributable to automatic stabilizers fell from 1.9% of GDP in FY2010 to 0.0% of GDP in FY2018. In other words, the budget deficit recorded in FY2018 (3.8% of GDP) is nearly identical to the "structural deficit" that economists would expect with automatic stabilizer effects removed from the budget.

Figure 3 shows the real economic growth (as a percentage on the horizontal axis) and the federal budget outcome (as a percentage of GDP, on the vertical axis) in each fiscal year from FY1969 through FY2018. The positive correlation between economic outcomes and budget outcomes is picked up by the general direction of the trend line from the lower left part of the graph to the upper right area.

How the Economy Contributes to Debt

All else equal, higher levels of nominal GDP make a given amount of debt easier to repay by eroding its real value. For example, the highest measurement of debt since 1940 occurred in 1946, when the federal debt level was 118.9% of GDP, or $271 billion in (nominal) FY1946 dollars. In contrast, $271 billion was equivalent to only 1.3% of GDP in FY2018.19 Increases in nominal GDP may be caused by productivity increases, economic inflation—which measures the purchasing power of currency—or a combination of each factor.20

Though changes in economic growth rates typically have a relatively small effect on real debt levels in the short run, long-run changes in economic productivity can have a significant effect on the trajectory and sustainability of the debt burden. For instance, from FY2009 through FY2018, federal deficits averaged 5.3% of GDP, and real economic growth averaged 1.76% per year over the same period; those factors combined to increase federal publicly held debt from 39% of GDP at the beginning of FY2008 to 78% of GDP at the end of FY2018.21 Though real deficits were actually larger from FY1943 to FY1952 (averaging 7.3% of GDP), robust real economic growth over that period (3.6% per year) meant that the change in publicly held debt in that decade was smaller (45% of GDP to 60% to GDP) than in the FY2009-FY2018 period.

Deficit and Debt Outlook

The FY2018 real deficit equaled 3.8% of GDP, which was higher than the average federal deficit from FY1969 to FY2018 (2.9% of GDP). Both real deficits and real debt are projected to increase over the course of the 10-year budget window, which runs through FY2029. In its latest economic forecast, the CBO projected that the total burden of U.S. debt held by the public would steadily increase over the course of the budget window, from 77.8% of GDP in FY2018 to 92.7% of GDP in FY2029.22

Table 2 provides the most recent forecasts for publicly held debt issued by the CBO. Each forecast projects an increase in publicly held debt over the next 5, 10, and 25 fiscal years.

|

Federal Debt Held by the Public |

|||||

|

Projection |

Forecast Date |

FY2019 |

FY2024 |

FY2029 |

FY2049 |

|

CBO Baseline |

January 2019 |

78 |

85 |

93 |

n/a |

|

CBO Alternative Fiscal Scenario |

January 2019 |

78 |

87 |

97 |

n/a |

|

CBO Long-Term Baseline |

January 2019 |

78 |

86 |

93 |

147 |

Source: CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2019 to 2029, January 2019. CRS calculations.

Notes: All baselines operate largely on a current law basis unless otherwise noted. CBO's Alternative Fiscal Scenario assumes that (1) discretionary spending rises with inflation after 2019; (2) emergency nondefense funding is provided at amounts consistent with their historical averages; and (3) roughly 30 tax provisions scheduled to expire under current law are extended.

The CBO baseline assumes that current law continues as scheduled. Specifically, the CBO baseline assumes that discretionary budget authority from FY2020 through FY2021 will be restricted by the caps created by the Budget Control Act (BCA; P.L. 112-25), as amended, and that certain tax policy changes enacted in the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) and in other laws will expire as scheduled under current law.23 CBO also provides alternative projections where such assumptions are revised. If discretionary spending increases with inflation after FY2019, instead of proceeding in accordance with the limits instituted by the BCA, and if tax reductions in the 2017 tax revision are extended, CBO projects that federal debt held by the public would increase to 97% of GDP by FY2029.

CBO also produces a long-term baseline that uses a number of additional assumptions to extend its standard baseline an additional 20 years (thus the 2018 long-term baseline runs through FY2049). The current long-term forecast projects that publicly held federal debt will equal 147% of GDP in FY2049, which would exceed the highest stock of federal debt experienced in the FY1940-FY2018 period (106% of GDP in FY1946).

CBO projects increases in both interest rates and publicly held federal debt over the next 10 years, leading to a significant rise in U.S. net interest payments. As noted above, CBO projects that publicly held federal debt will rise from 77.8% of GDP in FY2018 to 92.7% of GDP in FY2029, and projects that the average interest rate on three-month Treasury bills will rise from 1.66% in FY2017 to 2.81% in FY2029. Those factors combine to generate federal net interest payments of 3.0% of GDP in FY2029 under the CBO projections, which would be just under the highest amount paid from FY1940 through FY2017 (3.2% of GDP in FY1991).

International Context

It may be useful to compare the recent U.S. federal borrowing trajectory with the practices of international governments, because future interest rate and fiscal space considerations will both be affected by the behavior of other major actors. Table 3 includes the general government debt history and projections for G-7 countries and the European Area from FY2000 to FY2023.24

Table 3. IMF General Gross Debt for Selected Countries, 2000-2023

(as a percentage of GDP; change from preceding column in parentheses)

|

Country |

2000-2009 Average |

2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

|

United States |

65.4 |

104.9 (+39.5) |

106.1 (+1.2) |

117.0 (+10.9) |

|

Canada |

74.6 |

85.8 (+11.2) |

87.3 (+1.5) |

76.6 (-10.7) |

|

European Area |

68.8 |

91.5 (+22.7) |

84.4 (-7.1) |

74.5 (-9.9) |

|

France |

65.6 |

93.4 (+27.8) |

96.7 (+3.3) |

93.9 (-3.8) |

|

Germany |

63.9 |

77.5 (+13.6) |

59.8 (-17.7) |

44.6 (-15.2) |

|

Italy |

103.2 |

129.0 (+25.8) |

130.3 (+1.3) |

125.1 (-5.2) |

|

Japan |

168.9 |

232.5 (+63.6) |

238.2 (+5.7) |

235.4 (-2.8) |

|

United Kingdom |

41.6 |

85.8 (+44.2) |

87.4 (+1.6) |

84.0 (-3.4) |

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, Table A8, October 2018.

Notes: General gross debt includes debt held by municipal governments and includes only publicly held debt. IMF projections for the United States use data from the April 2018 CBO baseline and incorporate budgetary changes from the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) and the Bipartisan Budget Agreement of 2018 (P.L. 115-123).

The worldwide impact of the Great Recession led to increased general gross debt levels for all G-7 countries in 2013 relative to their 2000-2009 average. As shown in Table 3, U.S. debt levels rose by 40% of GDP over that time period, which was larger than increases in Canada and the European Area but smaller than rises in the United Kingdom and Japan. General debt levels largely stabilized from 2013 to 2018, with decreases in Germany and the European Area and small increases in other countries.

Future projections of debt included in Table 3 are characterized by a divergence between U.S. general gross debt levels and those in other G-7 countries. The IMF forecast projects that U.S. general gross debt will rise from 106% to 117% from 2018 to 2023, while those same projections forecast a decrease in debt owed by all other G-7 governments and in the European Area.

Addressing the potential consequences of those projections will likely involve policy adjustments that reduce future budget deficits, either through tax increases, reductions in spending, or a combination of the two. Under CBO's extended baseline, maintaining the debt-to-GDP ratio at today's level (78%) in FY2048 would require an immediate and permanent cut in noninterest spending, increase in revenues, or some combination of the two in the amount of 1.9% of GDP (or about $400 billion in FY2018 alone) in each year. Maintaining this debt-to-GDP ratio beyond FY2047 would require additional deficit reduction. If policymakers wanted to lower future debt levels relative to today, the annual spending reductions or revenue increases would have to be larger. For example, in order to bring debt as a percentage of GDP in FY2048 down to its historical average over the past 50 years (40% of GDP), spending reductions or revenue increases or some combination of the two would need to generate net savings of roughly 3.0% of GDP (or $630 billion in FY2018 alone) in each year.25