Introduction

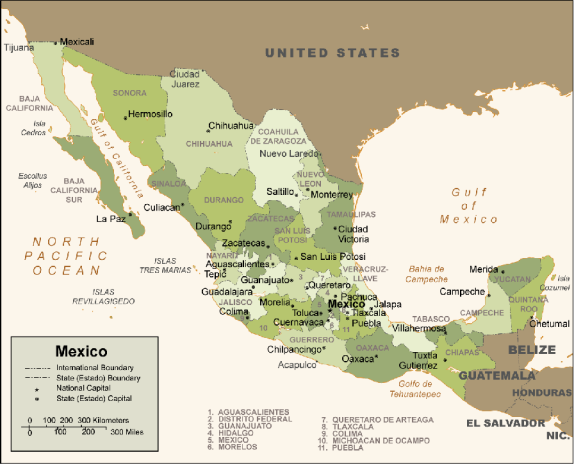

The U.S.-Mexico bilateral economic relationship is of key interest to the United States because of Mexico's proximity, the extensive cultural and economic ties between the two countries, and the strong economic relationship with Mexico under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).1 The United States and Mexico share many common economic interests related to trade, investment, and regulatory cooperation. The two countries share a 2,000-mile border and have extensive interconnections through the Gulf of Mexico. There are also links through migration, tourism, environmental issues, health concerns, and family and cultural relationships.

Congress has maintained an active interest on issues related to NAFTA renegotiations and the recently signed U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement (USMCA); U.S.-Mexico trade and investment relations; Mexico's economic reform measures, especially in the energy sector; the Mexican 2018 presidential elections; U.S.-Mexico border management; and other related issues.2 Congress has also maintained an interest in the ramifications of possible withdrawal from NAFTA. Congress may also take an interest in the economic policies of Mexico's new President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the populist leader of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party, who won the July 2018 election with 53% of the vote. MORENA's coalition also won majorities in both chambers of the legislature that convened on September 1, 2018. Former President Enrique Peña Nieto successfully drove numerous economic and political reforms that included, among other measures, opening up the energy sector to private investment, countering monopolistic practices, passing fiscal reform, making farmers more productive, and increasing infrastructure investment.3

This report provides an overview and background information regarding U.S.-Mexico economic relations, trade trends, the Mexican economy, NAFTA, the proposed USMCA, and trade issues between the United States and Mexico. It will be updated as events warrant.

U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations

Mexico is one of the United States' most important trading partners, ranking second among U.S. export markets and third in total U.S. trade (imports plus exports). Under NAFTA, the United States and Mexico have developed significant economic ties. Trade between the two countries has more than tripled since the agreement entered into force in 1994. Through NAFTA, the United States, Mexico, and Canada form one of the world's largest free trade areas, with about one-third of the world's total gross domestic product (GDP). Mexico has the second-largest economy in Latin America after Brazil. It has a population of 129 million people, making it the most populous Spanish-speaking country in the world and the third-most populous country in the Western Hemisphere (after the United States and Brazil).

Mexico's gross domestic product (GDP) was an estimated $1.15 trillion in 2017, about 6% of U.S. GDP of $19.39 trillion. Measured in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP),4 Mexican GDP was considerably higher, $2.35 trillion, or about 12% of U.S. GDP. Per capita income in Mexico is significantly lower than in the United States. In 2017, Mexico's per capita GDP in purchasing power parity was $17,743, or 30% of U.S. per capita GDP of $59,381 (see Table 1). Ten years earlier, in 2007, Mexico's per capita GDP in purchasing power parity was $13,995, or 29% of the U.S. amount of $48,006. Although there is a notable income disparity with the United States, Mexico's per capita GDP is relatively high by global standards, and falls within the World Bank's upper-middle income category.5 Mexico's economy relies heavily on the United States as an export market. The value of exports equaled 37% of Mexico's GDP in 2017, as shown in Table 1, and approximately 80% of Mexico's exports were headed to the United States.

|

Mexico |

United States |

|||||||

|

2007 |

2017a |

2007 |

2017 |

|||||

|

Population (millions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Nominal GDP (US$ billions)b |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Nominal GDP, PPPc Basis (US$ billions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Per Capita GDP (US$) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Per Capita GDP in $PPPs |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Nominal exports of goods & services (US$ billions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Exports of goods & services as % of GDPd |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Nominal imports of goods & services (US$ billions) |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Imports of goods & services as % of GDPd |

|

|

|

|

||||

Source: Compiled by CRS based on data from Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) online database.

a. Some figures for 2017 are estimates.

b. Nominal GDP is calculated by EIU based on figures from World Bank and World Development Indicators.

c. PPP refers to purchasing power parity, which reflects the purchasing power of foreign currencies in U.S. dollars.

U.S.-Mexico Trade

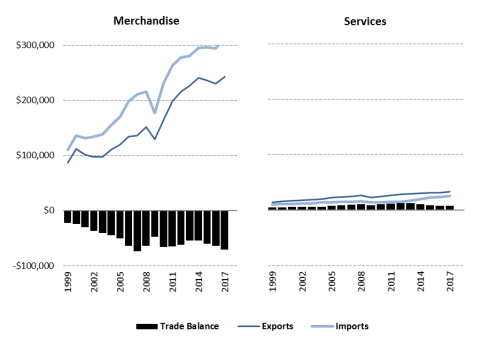

The United States is, by far, Mexico's leading partner in merchandise trade, while Mexico is the United States' third-largest trade partner after China and Canada. Mexico ranks second among U.S. export markets after Canada, and is the third-leading supplier of U.S. imports. U.S. merchandise trade with Mexico increased rapidly since NAFTA entered into force in January 1994. U.S. exports to Mexico increased from $41.6 billion in 1993 (the year prior to NAFTA's entry into force) to $265.0 billion in 2018. U.S. imports from Mexico increased from $39.9 billion in 1993 to $346.5 billion in 2018. The merchandise trade balance with Mexico went from a surplus of $1.7 billion in 1993 to a widening deficit that reached $74.3 billion in 2007 and then increased to an all-time high of $81.5 billion in 2018.

The United States had a surplus in services trade with Mexico of $7.4 billion in 2017 (latest available data), as shown in Figure 1. U.S. services exports to Mexico totaled $32.8 billion in 2017, up from $14.2 billion in 1999, while imports were valued at $25.5 billion in 2017, up from $9.7 billion in 1999.6

|

Figure 1. U.S. Trade with Mexico: 1999-2017 (U.S. $ in millions) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. |

U.S. Imports from Mexico

Leading U.S. merchandise imports from Mexico in 2018 included motor vehicles ($64.5 billion or 19% of imports from Mexico), motor vehicle parts ($49.8 billion or 14% of imports), computer equipment ($26.6 billion or 8% of imports), oil and gas ($14.5 billion or 4% of imports), and electrical equipment ($11.9 billion or 3% of imports), as shown in Table 2. U.S. imports from Mexico increased from $295.7 billion in 2014 to $346.5 billion in 2018. Oil and gas imports from Mexico have decreased sharply, dropping from $39.6 billion in 2011 to $7.6 billion in 2016, partially due to a decrease in oil production but also because of the drop in the price of oil around the world. In 2017, U.S. oil and gas imports from Mexico increased to $14.5 billion.

|

Items (NAIC 4-digit) |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

% Total Imports from Mexico |

|

Motor vehicles |

46.2 |

50.0 |

49.3 |

57.4 |

64.5 |

19% |

|

Motor vehicle parts |

40.3 |

43.9 |

46.0 |

45.5 |

49.8 |

14% |

|

Computer equipment |

13.8 |

17.1 |

18.2 |

20.2 |

26.6 |

8% |

|

Oil and gas |

27.8 |

12.5 |

7.6 |

10.1 |

14.5 |

4% |

|

Electrical equipment |

10.1 |

10.5 |

10.5 |

11.1 |

11.9 |

3% |

|

Other |

157.5 |

162.4 |

162.3 |

170 |

179.2 |

52% |

|

Total |

295.7 |

296.4 |

293.9 |

314.3 |

346.5 |

Source: Compiled by CRS using USITC Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb at http://dataweb.usitc.gov: North American Industrial Classification (NAIC) 4-digit level.

Note: Nominal U.S. dollars.

U.S. Exports to Mexico

Leading U.S. exports to Mexico in 2018 consisted of petroleum and coal products ($28.8 billion or 11% of exports to Mexico), motor vehicle parts ($20.2 billion or 8% of exports), computer equipment ($17.4 billion or 7% of exports), semiconductors and other electronic components ($13.1 billion or 5% of exports), and basic chemicals ($10.3 billion or 4% of exports), as shown in Table 3.

|

Items (NAIC 4-digit) |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

% Total Imports from Mexico |

|

Petroleum and coal products |

19.6 |

15.4 |

15.9 |

21.6 |

28.8 |

11% |

|

Motor vehicle parts |

18.4 |

20.8 |

19.8 |

19.8 |

20.2 |

8% |

|

Computer equipment |

15.9 |

16.2 |

16.5 |

15.7 |

17.4 |

7% |

|

Semiconductors and other electronic components |

10.9 |

11.4 |

12 |

12.2 |

13.1 |

5% |

|

Basic chemicals |

10.1 |

8.5 |

8.1 |

9.4 |

10.3 |

4% |

|

Other |

166.1 |

164.2 |

157.8 |

164.6 |

175.2 |

66% |

|

Total |

241.0 |

236.5 |

230.1 |

243.3 |

265.0 |

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using USITC Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb at http://dataweb.usitc.gov: NAIC 4-digit level.

Note: Nominal U.S. dollars.

Bilateral Foreign Direct Investment

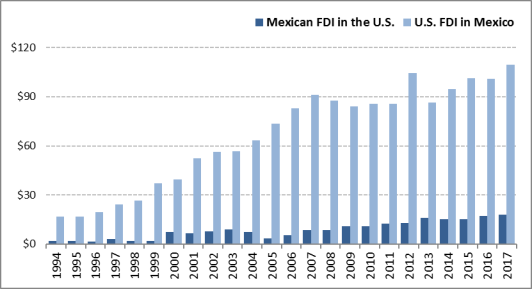

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been an integral part of the economic relationship between the United States and Mexico since NAFTA implementation. The United States is the largest source of FDI in Mexico. The stock of U.S. FDI increased from $17.0 billion in 1994 to a high of $109.7 billion in 2017. While the stock Mexican FDI in the United States is much lower, it has increased significantly since NAFTA, from $2.1 billion in 1994 to $18.0 billion in 2017 (see Figure 2).

The liberalization of Mexico's restrictions on foreign investment in the late 1980s and the early 1990s played an important role in attracting U.S. investment to Mexico. Up until the mid-1980s, Mexico had a very protective policy that restricted foreign investment and controlled the exchange rate to encourage domestic growth, affecting the entire industrial sector. A sharp shift in policy in the late 1980s that included market opening measures and economic reforms helped bring in a steady increase of FDI flows. These reforms were locked in through NAFTA provisions on foreign investment and resulted in increased investor confidence. NAFTA investment provisions give North American investors from the United States, Mexico, or Canada nondiscriminatory treatment of their investments as well as investor protection. NAFTA may have encouraged U.S. FDI in Mexico by increasing investor confidence, but much of the growth may have occurred anyway because Mexico likely would have continued to liberalize its foreign investment laws with or without the agreement.

|

Figure 2. U.S. and Mexican Foreign Direct Investment Positions 1994-2017 Historical Cost Basis |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

Manufacturing and U.S.-Mexico Supply Chains

Many economists and other observers have credited NAFTA with helping U.S. manufacturing industries, especially the U.S. auto industry, become more globally competitive through the development of supply chains. Much of the increase in U.S.-Mexico trade, for example, can be attributed to specialization as manufacturing and assembly plants have reoriented to take advantage of economies of scale. As a result, supply chains have been increasingly crossing national boundaries as manufacturing work is performed wherever it is most efficient. A reduction in tariffs in a given sector not only affects prices in that sector but also in industries that purchase intermediate inputs from that sector. Some analysts believe that the importance of these direct and indirect effects is often overlooked. They suggest that these linkages offer important trade and welfare gains from free trade agreements and that ignoring these input-output linkages could underestimate potential trade gains.7

A significant portion of merchandise trade between the United States and Mexico occurs in the context of production sharing as manufacturers in each country work together to create goods. Trade expansion has resulted in the creation of vertical supply relationships, especially along the U.S.-Mexico border. The flow of intermediate inputs produced in the United States and exported to Mexico and the return flow of finished products greatly increased the importance of the U.S.-Mexico border region as a production site. U.S. manufacturing industries, including automotive, electronics, appliances, and machinery, all rely on the assistance of Mexican manufacturers.

In the auto sector, for example, trade expansion has resulted in the creation of vertical supply relationships throughout North America. The flow of auto merchandise trade between the United States and Mexico greatly increased the importance of North America as a production site for automobiles. According to industry experts, the North American auto industry has "multilayered connections" between U.S. and Mexican suppliers and assembly points. A Wall Street Journal article describes how an automobile produced in the United States has tens of thousands of parts that come from multiple producers in different countries and travel back and forth across borders several times.8 A company producing seats for automobiles, for example, incorporates components from four different U.S. states and four Mexican locations into products produced in the Midwest. These products are then sold to major car makers.9 The place where final assembly of a product is assembled may have little bearing on where its components are made.

The integration of the North American auto industry is reflected in the percentage of U.S. auto imports that enter the United States duty-free under NAFTA. In 2017, 99% of U.S. motor vehicle imports from Mexico entered the United States duty-free under NAFTA, compared to 76% of motor vehicle parts. Only 56% of total U.S. imports from Mexico received duty-free treatment under NAFTA; the remainder entered the United States under other programs.10

Mexico's Export Processing Zones

Mexico's export-oriented assembly plants, a majority of which have U.S. parent companies, are closely linked to U.S.-Mexico trade in various labor-intensive industries such as auto parts and electronic goods. Foreign-owned assembly plants, which originated under Mexico's maquiladora program in the 1960s,11 account for a substantial share of Mexico's trade with the United States. These export processing plants use extensive amounts of imported content to produce final goods and export the majority of their production to the U.S. market.

NAFTA, along with a combination of other factors, contributed to a significant increase in Mexican export-oriented assembly plants, such as maquiladoras, after its entry into force. Other factors that contributed to manufacturing growth and integration include trade liberalization, wages, and economic conditions, both in the United States and Mexico. Although some provisions in NAFTA may have encouraged growth in certain sectors, manufacturing activity likely has been more influenced by the strength of the U.S. economy and relative wages in Mexico.

Private industry groups state that these operations help U.S. companies remain competitive in the world marketplace by producing goods at competitive prices. In addition, the proximity of Mexico to the United States allows production to have a higher degree of U.S. content in the final product, which could help sustain jobs in the United States. Critics of these types of operations argue that they have a negative effect on the economy because they take jobs from the United States and help depress the wages of low-skilled U.S. workers.

Maquiladoras and NAFTA

Changes in Mexican regulations on export-oriented industries after NAFTA merged the maquiladora industry and Mexican domestic assembly-for-export plants into one program called the Maquiladora Manufacturing Industry and Export Services (IMMEX).

NAFTA rules for the maquiladora industry were implemented in two phases, with the first phase covering the period 1994-2000, and the second phase starting in 2001. During the initial phase, NAFTA regulations continued to allow the maquiladora industry to import products duty-free into Mexico, regardless of the country of origin of the products. This phase also allowed maquiladora operations to increase maquiladora sales into the Mexican domestic market.

Phase II made a significant change to the industry in that the new North American rules of origin determined duty-free status for U.S. and Canadian products exported to Mexico for maquiladoras. In 2001, the North American rules of origin determined the duty-free status for a given import and replaced the previous special tariff provisions that applied only to maquiladora operations. The initial maquiladora program ceased to exist and the same trade rules applied to all assembly operations in Mexico.

The elimination of duty-free imports by maquiladoras from non-NAFTA countries under NAFTA caused some initial uncertainty for the companies with maquiladora operations. Maquiladoras that were importing from third countries, such as Japan or China, would have to pay applicable tariffs on those goods under the new rules.

Worker Remittances to Mexico

Remittances are one of the three highest sources of foreign currency for Mexico, along with foreign direct investment and tourism. Most remittances to Mexico come from workers in the United States who send money back to their relatives. Mexico receives the largest amount of remittances in Latin America. Remittances are often a stable financial flow for some regions as workers in the United States make efforts to send money to family members. Most go to southern states where poverty levels are high. Women tend to be the primary recipients of the money, and usually use it for basic needs such as rent, food, medicine, and/or utilities.

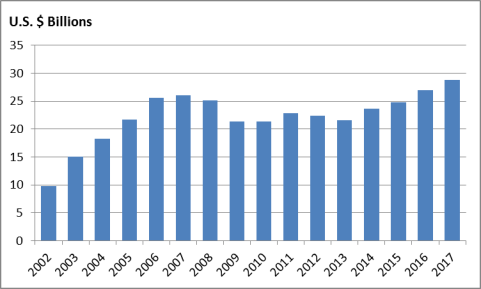

The year 2017 was a record-breaking one for remittances to Mexico, with a total of $28.8 billion, which represents an increase of 7.5% over the 2016 level. In 2016, annual remittances to Mexico increased by 8.7% to a record high at the time of $27.0 billion (see Figure 3).12 Some analysts contend that the increase is partially due to the sharp devaluation of the Mexican peso after the election of President Donald Trump, while others state that it is a shock reaction to President Trump's threat to block money transfers to Mexico to pay for a border wall.13 The weaker value of the peso has negatively affected its purchasing power in Mexico, especially among the poor, and many families have had to rely more on money sent from their relatives in the United States. Since the late 1990s, remittances have been an important source of income for many Mexicans. Between 1996 and 2007, remittances increased from $4.2 billion to $26.1 billion, an increase of over 500%, and then declined by 15.2%, in 2009, likely due to the global financial crisis. The growth rate in remittances has been related to the frequency of sending, exchange rate fluctuations, migration, and employment in the United States.14

Electronic transfers and money orders are the most popular methods to send money to Mexico. Worker remittance flows to Mexico have an important impact on the Mexican economy, in some regions more than others. Some studies report that in southern Mexican states, remittances mostly or completely cover general consumption and/or housing. A significant portion of the money received by households goes for food, clothing, health care, and other household expenses. Money also may be used for capital invested in microenterprises throughout urban Mexico. The economic impact of remittance flows is concentrated in the poorer states of Mexico.

|

Figure 3. Remittances to Mexico (from all countries) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from the Inter-American Development Bank, Multilateral Investment Fund; and Mexico's Central Bank. |

Bilateral Economic Cooperation

The United States has engaged in bilateral efforts with Mexico, and also with Canada, to address issues related to border security, trade facilitation, economic competitiveness, regulatory cooperation, and energy integration.

High Level Economic Dialogue (HLED)

The United States and Mexico launched the High Level Economic Dialogue (HLED) on September 20, 2013, to help advance U.S.-Mexico economic and commercial priorities that are central to promoting mutual economic growth, job creation, and global competitiveness. The initiative is led at the Cabinet level and is co-chaired by the U.S. Department of State, Department of Commerce, the Office of the United States Trade Representative, and their Mexican counterparts.15

Major goals of the HLED are meant to build on, but not duplicate, a range of existing bilateral dialogues and working groups. The United States and Mexico aim to promote competitiveness in specific sectors such as transportation, telecommunications, and energy, as well as to promote greater two-way investment.16

The HLED is organized around three broad pillars, including

- 1. Promoting competitiveness and connectivity;

- 2. Fostering economic growth, productivity, and innovation; and

- 3. Partnering for regional and global leadership.

The HLED is also meant to explore ways to promote entrepreneurship, stimulate innovation, and encourage the development of human capital to meet the needs of the 21st century economy, as well as examine initiatives to strengthen economic development along the U.S.-Mexico border region.

High-Level Regulatory Cooperation Council

Another bilateral effort is the U.S.-Mexico High-Level Regulatory Cooperation Council (HLRCC), launched in May 2010. The official work plan was released by the two governments on February 28, 2012, and focuses on regulatory cooperation in numerous sectoral issues including food safety, e-certification for plants and plant products, commercial motor vehicle safety standards and procedures, nanotechnology, e-health, and offshore oil and gas development standards. U.S. agencies involved in regulatory cooperation include the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Agriculture, Department of Transportation, Office of Management and Budget, Department of the Interior, and Occupational Safety and Health Administration.17

21st Century Border Management

The United States and Mexico are engaged in a bilateral border management initiative under the Declaration Concerning 21st Century Border Management that was announced in 2010. This initiative is a bilateral effort to manage the 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border through the following cooperative efforts: expediting legitimate trade and travel; enhancing public safety; managing security risks; engaging border communities; and setting policies to address possible statutory, regulatory, and/or infrastructure changes that would enable the two countries to improve collaboration.18 With respect to port infrastructure, the initiative specifies expediting legitimate commerce and travel through investments in personnel, technology, and infrastructure.19 The two countries established a Bilateral Executive Steering Committee (ESC) composed of representatives from the appropriate federal government departments and offices from both the United States and Mexico. For the United States, this includes representatives from the Departments of State, Homeland Security, Justice, Transportation, Agriculture, Commerce, Interior, and Defense, and the Office of the United States Trade Representative. For Mexico, it includes representatives from the Secretariats of Foreign Relations, Interior, Finance and Public Credit, Economy, Public Security, Communications and Transportation, Agriculture, and the Office of the Attorney General of the Republic.20

North American Leaders Summits

Since 2005, the United States, Canada, and Mexico have made efforts to increase cooperation on economic and security issues through various endeavors. President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama, with the leaders of Mexico and Canada, participated in trilateral summits known as the North American Leaders' Summits (NALS). The first NALS took place in March 2005, in Waco, Texas, and was followed by numerous trilateral summits in Mexico, Canada, and the United States. President Obama participated in the last summit on June 29, 2016, in Ottawa, Canada, with an agenda focused on economic competitiveness, climate change, clean energy, the environment, regional and global cooperation, security, and defense.21 President Donald Trump has not indicated whether his Administration plans to continue NALS efforts.

The United States has pursued other efforts with Canada and Mexico, many of which have built upon the accomplishments of the working groups formed under the NALS. These efforts include the North American Competitiveness Work Plan (NACW) and the North American Competitiveness and Innovation Conference (NACIC).22

Proponents of North American competitiveness and security cooperation view the initiatives as constructive to addressing issues of mutual interest and benefit for all three countries, especially in the areas of North American regionalism; inclusive and shared prosperity; innovation and education; energy and climate change; citizen security; and regional, global, and stakeholder outreach to Central America and other countries in the Western Hemisphere. Some critics believe that the summits and other trilateral efforts are not substantive enough and that North American leaders should make their meetings more consequential with follow-up mechanisms that are more action oriented. Others contend that the efforts do not go far enough in including human rights issues or discussions on drug-related violence in Mexico.

The Mexican Economy

Mexico's economy is closely linked to the U.S. economy due to the strong trade and investment ties between the two countries. Economic growth has been slow in recent years. The forecast over the next few years projects economic growth of above 2%, a positive outlook, according to some economists, given external constraints but falling short of what the country needs to make a significant cut in poverty and to create jobs.23

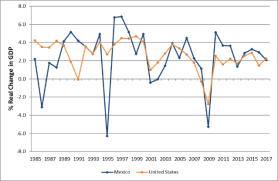

Over the past 30 years, Mexico has had a low economic growth record with an average growth rate of 2.6%. Mexico's GDP grew by 2.4% in 2017 and 2.1% in 2016. The country benefitted from important structural reforms initiated in the early 1990s, but events such as the U.S. recession of 2001 and the global economic downturn of 2009 adversely affected the economy and offset the government's efforts to improve macroeconomic management.

|

|

Source: CRS using data from the Economist Intelligence Unit. |

The OECD outlook for Mexico for 2018 states that there are some encouraging signs for potential economic growth, including improvements in fiscal performance, responsible and reliable monetary policy to curb inflation, growth in manufacturing exports and inflows of foreign direct investment, and positive developments due to government reforms in telecommunications, energy, labor, education, and other structural reforms. According to the OECD, full implementation of Mexico's structural reforms could add as much as 1% to the annual growth rate of the Mexican economy.24 While these achievements may be positive, Mexico continues to face significant challenges in regard to alleviating poverty, decreasing informality, strengthening judicial institutions, addressing corruption, and increasing labor productivity.25

Trends in Mexico's GDP growth generally follow U.S. economic trends, as shown in Figure 4, but with higher fluctuations. Mexico's economy is highly dependent on manufacturing exports to the United States, as approximately 80% of Mexico's exports are destined for the United States. The country's outlook will likely remain closely tied to that of the United States, despite Mexico's efforts to diversify trade.

Informality and Poverty

Part of the government's reform efforts are aimed at making economic growth more inclusive, reducing income inequality, improving the quality of education, and reducing informality and poverty. Mexico has a large informal sector that is estimated to account for a considerable portion of total employment. Estimates on the size of the informal labor sector vary widely, with some sources estimating that the informal sector accounts for about one-third of total employment and others estimating it to be as high as two-thirds of the workforce. Under Mexico's legal framework, workers in the formal sector are defined as salaried workers employed by a firm that registers them with the government and are covered by Mexico's social security programs. Informal sector workers are defined as nonsalaried workers who are usually self-employed. These workers have various degrees of entitlement to other social protection programs. Salaried workers can be employed by industry, such as construction, agriculture, or services. Nonsalaried employees are defined by social marginalization or exclusion and can be defined by various categories. These workers may include agricultural producers; seamstresses and tailors; artisans; street vendors; individuals who wash cars on the street; and other professions.

Many workers in the informal sector suffer from poverty, which has been one of Mexico's more serious and pressing economic problems for many years. Although the government has made progress in poverty reduction efforts, poverty continues to be a basic challenge for the country's development. The Mexican government's efforts to alleviate poverty have focused on conditional cash transfer programs. The Prospera (previously called Oportunidades) program seeks to not only alleviate the immediate effects of poverty through cash and in-kind transfers, but to break the cycle of poverty by improving nutrition and health standards among poor families and increasing educational attainment. Prospera has provided cash transfers to the poorest 6.9 million Mexican households located in localities from all 32 Mexican states. It has been replicated in about two dozen countries throughout the world.26 The program provides cash transfers to families in poverty who demonstrate that they regularly attend medical appointments and can certify that children are attending school. The government also provides educational cash transfers to participating families. Programs also provide nutrition support to pregnant and nursing women and malnourished children.27

Some economists cite the informal sector as a hindrance to the country's economic development. Other experts contend that Mexico's social programs benefitting the informal sector have led to increases in informal employment.

Structural and Other Economic Challenges

For years, numerous political analysts and economists have agreed that Mexico needs significant political and economic structural reforms to improve its potential for long-term economic growth. President Peña Nieto was successful in breaking the gridlock in the Mexican government and passing reform measures meant to stimulate economic growth. The OECD stated that the main challenge for the government is to ensure full implementation of the reforms and that it needed to progress further in other key areas. According to the OECD, Mexico must improve administrative capacity at all levels of government and reform its judicial institutions. Such actions would have a strong potential to boost living standards substantially, stimulate economic growth, and reduce income inequality. The OECD stated that issues regarding human rights conditions, rule of law, and corruption were also challenges that needed to be addressed by the government, as they too affect economic conditions and living standards.28

According to a 2014 study by the McKinsey Global Institute, Mexico had successfully created globally competitive industries in some sectors, but not in others.29 The study described a "dualistic" nature of the Mexican economy in which there was a modern Mexico with sophisticated automotive and aerospace factories, multinationals that could compete in global markets, and universities that graduated high numbers of engineers. In contrast, the other part of Mexico, consisting of smaller, more traditional firms, was technologically backward, unproductive, and operated outside the formal economy.30 The study stated that three decades of economic reforms had failed to raise the overall GDP growth. Government measures to privatize industries, liberalize trade, and welcome foreign investment created a side to the economy that was highly productive in which numerous industries had flourished, but the reforms had not yet been successful in touching other sectors of the economy where traditional enterprises had not modernized, informality was rising, and productivity was plunging.31

Energy

Mexico's long-term economic outlook depends largely on the energy sector. The country is one of the largest oil producers in the world, but its oil production has steadily decreased since 2005 as a result of natural production declines. According to industry experts, Mexico has the potential resources to support a long-term recovery in total production, primarily in the Gulf of Mexico. However, the country does not have the technical capability or financial means to develop potential deepwater projects or shale oil deposits in the north. Reversing these trends is a goal of the 2013 historic constitutional energy reforms sought by President Peña Nieto and enacted by the Mexican Congress. The reforms opened Mexico's energy sector to production-sharing contracts with private and foreign investors while keeping the ownership of Mexico's hydrocarbons under state control. They will likely expand U.S.-Mexico energy trade and provide opportunities for U.S. companies involved in the hydrocarbons sector, as well as infrastructure and other oil field services.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) excluded foreign investment in Mexico's energy sector. Under NAFTA's energy chapter, parties confirmed respect for their constitutions, which was of particular importance for Mexico and its 1917 Constitution establishing Mexican national ownership of all hydrocarbons resources and restrictions of private or foreign participation in its energy sector. Under NAFTA, Mexico also reserved the right to provide electricity as a domestic public service.

In the NAFTA renegotiations (see section below on "NAFTA Renegotiation and the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)"), the United States sought to preserve and strengthen investment, market access, and state-owned enterprise disciplines benefitting energy production and transmission. In addition, the negotiating objectives stated that the United States supports North American energy security and independence, and promotes the continuation of energy market-opening reforms.32 Mexico specifically called for a modernization of NAFTA's energy provisions. The USMCA retains recognition of Mexico's national ownership of all hydrocarbons.

Some observers contend that much is at stake for the North American oil and gas industry in the bilateral economic relationship, especially in regard to Mexico as an energy market for the United States. Although Mexico was traditionally a net exporter of hydrocarbons to the United States, the United States had a trade surplus in 2016 of almost $10 billion in energy trade as a result of declining Mexican oil production, lower oil prices, and rising U.S. natural gas and refined oil exports to Mexico. The growth in U.S. exports is largely due to Mexico's reforms, which have driven investment in new natural gas-powered electricity generation and the retail gasoline market. Some observers contend that dispute settlement mechanisms in NAFTA and the proposed USMCA will defend the interests of the U.S. government and U.S. companies doing business in Mexico. They argue that the dispute settlement provisions and the investment chapter of the agreement will help protect U.S. multibillion-dollar investments in Mexico. They argue that a weakening of NAFTA's dispute settlement provisions would result in less protection of U.S. investors in Mexico and less investor confidence.33

Mexico's Regional Trade Agreements

Mexico has had a growing commitment to trade integration and liberalization through the formation of FTAs since the 1990s, and its trade policy is among the most open in the world. Mexico's pursuit of FTAs with other countries not only provides domestic economic benefits, but could also potentially reduce its economic dependence on the United States.

Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) Agreement

Mexico signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a negotiated regional free trade agreement (FTA), but which has not entered into force, among the United States, Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam.34 In January 2017, the United States gave notice to the other TPP signatories that it does not intend to ratify the agreement.

On March 8, 2018, Mexico and the 10 remaining signatories of the TPP signed the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP parties announced the outlines of the agreement in November 2017 and concluded the negotiations in January 2018. The CPTPP, which will enact much of the proposed TPP without the participation of the United States, is set to take effect on December 30, 2018. It requires ratification by 6 of the 11 signatories to become effective. As of October 31, 2018, Mexico, Canada, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and Singapore had ratified the agreement. Upon entry into force, it will reduce and eliminate tariff and nontariff barriers on goods, services, and agriculture. It could enhance the links Mexico already has through its FTAs with other signatories—Canada, Chile, Japan, and Peru—and expand its trade relationship with other countries, including Australia, Brunei, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam.

Mexico's Free Trade Agreements

Mexico has a total of 11 free trade agreements involving 46 countries. These include agreements with most countries in the Western Hemisphere, including the United States and Canada under NAFTA, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Peru, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. In addition, Mexico has negotiated FTAs outside of the Western Hemisphere and entered into agreements with Israel, Japan, and the European Union.

Given the perception of a rising protectionist sentiment in the United States, some regional experts have suggested that Mexico is seeking to negotiate new FTAs more aggressively and deepen existing ones.35 In addition to being a party to the CPTPP, Mexico and the EU renegotiated their FTA and modernized it with updated provisions. Discussions included government procurement, energy trade, IPR protection, rules of origin, and small- and medium-sized businesses. The new agreement is expected to replace a previous agreement between Mexico and the EU from 2000.36 The agreement is expected to allow almost all goods, including agricultural products, to move between Europe and Mexico duty-free. Mexico is also a party to the Pacific Alliance, a regional integration initiative formed by Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru in 2011. Its main purpose is to form a regional trading bloc and stronger ties with the Asia-Pacific region. The Alliance has a larger scope than free trade agreements, including the free movement of people and measures to integrate the stock markets of member countries.37

NAFTA

NAFTA has been in effect since January 1994.38 Prior to NAFTA, Mexico was already liberalizing its protectionist trade and investment policies that had been in place for decades. The restrictive trade regime began after Mexico's revolutionary period, and remained until the early to mid-1980s, when it began to shift to a more open, export-oriented economy. For Mexico, an FTA with the United States represented a way to lock in trade liberalization reforms, attract greater flows of foreign investment, and spur economic growth. For the United States, NAFTA represented an opportunity to expand the growing export market to the south, but it also represented a political opportunity to improve the relationship with Mexico.

NAFTA Renegotiation and the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)

On November 30, 2018, the United States, Canada, and Mexico signed the proposed USMCA. Concluded on September 30, 2018, USMCA would revise and modernize NAFTA.39 The proposed USMCA would have to be approved by Congress and ratified by Mexico and Canada before entering into force. Pursuant to trade promotion authority (TPA), the preliminary agreement with Mexico was notified to Congress on August 31, 2018, in part to allow for the signing of the agreement prior to Mexico's president-elect Andreas Manuel Lopez Obrador taking office on December 1, 2018. TPA contains certain notification and reporting requirements that likely will push any consideration of implementing legislation into the 116th Congress.40

USMCA, comprised of 34 chapters and 12 side letters, retains most of NAFTA's chapters, making notable changes to market access provisions for autos and agriculture products, and to rules such as investment, government procurement, and intellectual property rights (IPR). New issues, such as digital trade, state-owned enterprises, anticorruption, and currency misalignment, are also addressed.

NAFTA renegotiation provided opportunities to modernize the 1994 agreement by addressing issues not covered in the original text and updating others. Many U.S. manufacturers, services providers, and agricultural producers opposed efforts to withdraw from NAFTA and asked the Trump Administration to "do no harm" in the negotiations because they have much to lose if the United States pulls out of the agreement. Contentious issues in the negotiations reportedly included auto rules of origin, a "sunset clause" related to the trade deficit, dispute settlement provisions, and agriculture provisions on seasonal produce.

Possible Effect of Withdrawal from NAFTA

President Trump stated on December 1, 2018, that he intends to notify Mexico and Canada that he intends to withdraw from NAFTA with a notice of six months. A NAFTA withdrawal by the United States prior to congressional approval of the proposed USMCA would have significant implications going forward for U.S. trade policy and U.S.-Mexico economic relations. Numerous think tanks and economists have written about the possible economic consequences of U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA:

- An analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) finds that a withdrawal from NAFTA would cost the United States 187,000 jobs that rely on exports to Mexico and Canada. These job losses would occur over a period of one to three years. By comparison, according to the study, between 2013 and 2015, 7.4 million U.S. workers were displaced or lost their jobs involuntarily due to companies shutting down or moving elsewhere globally. The study notes that the most affected states would be Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Indiana. The most affected sectors would be autos, agriculture, and nonauto manufacturing.41

- A 2017 study by ImpactEcon, an economic analysis consulting company, estimates that if NAFTA were to terminate, real GDP, trade, investment, and employment in all three NAFTA countries would decline.42 The study estimates U.S. job losses of between 256,000 and 1.2 million in three to five years, with about 95,000 forced to relocate to other sectors. Canadian and Mexican employment of low-skilled workers would decline by 125,000 and 951,000 respectively.43 The authors of the study estimate a decline in U.S. GDP of 0.64% (over $100 billion).

- The Coalition of Services Industries (CSI) argues that NAFTA continues to be a remarkable success for U.S. services providers, creating a vast market for U.S. services providers, such as telecommunications and financial services. CSI estimates that if NAFTA is terminated, the United States risks losing $88 billion in annual U.S. services exports to Canada and Mexico, which support 587,000 high-paying U.S. jobs.44

Opponents of NAFTA argue that it has resulted in thousands of lost jobs to Mexico and has put downward pressure on U.S. wages. A study by the Economic Policy Institute estimates that, as of 2010, U.S. trade deficits with Mexico had displaced 682,900 U.S. jobs.45 Others contend that workers need more effective protections in trade agreements, with stronger enforcement mechanisms. For example, the AFL-CIO states that current U.S. FTAs have no deadlines or criteria for pursuing sanctions against a trade partner that is not enforcing its FTA commitments. The AFL-CIO contends that the language tabled by the United States in the renegotiations does nothing to improve long-standing shortcomings in NAFTA.46

Canada and Mexico likely would maintain NAFTA between themselves if the United States were to withdraw. U.S.-Canada trade could be governed either by the Canada-U.S. free trade agreement (CUSFTA), which entered into force in 1989 (suspended since the advent of NAFTA), or by the baseline commitments common to both countries as members of the World Trade Organization. If CUSFTA remains in effect, the United States and Canada would continue to exchange goods duty free and would continue to adhere to many provisions of the agreement common to both CUSFTA and NAFTA. Some commitments not included in the CUSFTA, such as intellectual property rights, would continue as baseline obligations in the WTO.47 It is unclear whether CUSFTA would remain in effect as its continuance would require the assent of both parties.48

Selected Bilateral Trade Disputes

The United States and Mexico have had a number of trade disputes over the years, many of which have been resolved. These issues have involved trade in sugar, country of origin labeling, tomato imports from Mexico, dolphin-safe tuna labeling, and NAFTA trucking provisions.

Section 232 and U.S. Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum Imports

The United States and Mexico are currently in a trade dispute over U.S. actions to impose tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum. The United States claims its actions are due to national security concerns; however, Mexico contends that U.S. tariffs are meant to protect domestic industries from import competition and are inconsistent with the World Trade Organization (WTO) Safeguard Agreement.49

On March 8, 2018, President Trump issued two proclamations imposing tariffs on U.S. imports of certain steel and aluminum products, respectively, using presidential powers granted under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.50 Section 232 authorizes the President to impose restrictions on certain imports based on an affirmative determination by the Department of Commerce that the targeted import products threaten to impair national security. The proclamations outlined the President's decisions to impose tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum imports, with some flexibility on the application of tariffs by country. On March 22, the President issued proclamations temporarily excluding Mexico, Canada, and numerous other countries, giving a deadline of May 1, by which time each trading partner had to negotiate an alternative means to remove the "threatened impairment to the national security by import" for steel and aluminum in order to maintain the exemption. After the temporary exception expired on May 31, 2018, the United States began imposing a 25% duty on steel imports and a 10% duty on aluminum imports from Mexico and Canada.51

The conclusion of the proposed USMCA did not resolve or address the Section 232 tariffs on imported steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico. The three parties continue to discuss the tariffs, which some analysts believe could result in quotas on imports of Mexican and Canadian steel and aluminum.

In response to the U.S. action, Mexico and several other major partners initiated dispute settlement proceedings and announced their intention to retaliate against U.S. exports. Mexico announced it would impose retaliatory tariffs on 71 U.S. products, covering an estimated $3.7 billion worth of trade, as shown in Table 4.52 Mexico is a major U.S. partner for both steel and aluminum trade. In 2017, Mexico ranked second, after Canada, among U.S. trading partners for both steel and aluminum. U.S.-Mexico trade in steel and aluminum totaled $10.3 billion in 2017, as shown in Table 5.

|

U.S. exports targeted for retaliation |

Value of U.S. exports to Mexico, 2017 |

Additional tariffs on U.S. exports |

|

Pork products |

$1,399 |

15-25% |

|

Steel products |

$753 |

7-25% |

|

Other processed food and beverages |

$611 |

20-25% |

|

Cheese |

$383 |

20-25% |

|

Apples |

$276 |

20% |

|

All other |

$268 |

20-25% |

|

Total |

$3,691 |

7-25% |

Source: U.S. exports estimated by using Mexico's import data for 2017, via Global Trade Atlas. Commodities were identified in Mexico's retaliatory notice (Ministry of Finance (Mexico), "Decree modifying the Tariff of the General Import and Export Tax Law," Federal Register (Diario Oficial de la Federacion), June 5, 2018, available at: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5525036&fecha=05/06/2018).

Notes: One commodity code listed on the Mexican notice is newly established and does not have any reported data for 2017; to estimate the amount of trade, CRS used the higher-level, 6-digit version of the code (160100).

a. Examples include bourbon, stewed cranberries, and prepared potatoes.

|

Exports to Mexico |

Imports from Mexico |

Trade Balance |

Total Trade |

Additional tariffs on imports from Mexico |

||||

|

Steel |

25% |

|||||||

|

Value (USD, mil.) |

$4,432 |

$2,494 |

$1,937 |

$6,926 |

||||

|

% of U.S. steel trade |

33.1% |

8.6% |

-- |

16.3% |

||||

|

Aluminum |

|

10% |

||||||

|

Value (USD, mil.) |

$3,095 |

$262 |

$2,833 |

$3,358 |

|

|||

|

% of U.S. aluminum trade |

43.4% |

1.5% |

-- |

13.7% |

|

|||

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, accessed via Global Trade Atlas.

Notes: Steel and aluminum are defined according to the commodity codes detailed in the U.S. Commerce Department's Section 232 Investigation Reports.

Dolphin-Safe Tuna Labeling Dispute

The United States and Mexico are currently involved in a trade dispute under the WTO regarding U.S. dolphin-safe labeling provisions and tuna imports from Mexico. Mexico has long argued that U.S. labeling rules for dolphin-safe tuna negatively affect its tuna exports to the United States. The United States contends that Mexico's use of nets and chasing dolphins to find large schools of tuna is harmful to dolphins. The most recent development in the long trade battle took place on April 25, 2017, when a WTO arbitrator determined that Mexico is entitled to levy trade restrictions on imports from the United States worth $163.2 million per year. The arbitrator made the decision based on a U.S. action from 2013 (see section below on "WTO Tuna Dispute Proceedings"), but did not make a compliance judgment on the U.S. 2016 dolphin-safe tuna labeling rule that the United States has said brings it into compliance with the WTO's previous rulings.53

Dispute over U.S. Labeling Provisions

The issue relates to U.S. labeling provisions that establish conditions under which tuna products may voluntarily be labeled as "dolphin-safe." Products may not be labeled as dolphin-safe if the tuna is caught by means that include intentionally encircling dolphins with nets. According to the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), some Mexican fishing vessels use this method when fishing for tuna. Mexico asserts that U.S. tuna labeling provisions deny Mexican tuna effective access to the U.S. market.54

The government of Mexico requested the United States to broaden its dolphin-safe rules to include Mexico's long-standing tuna fishing technique. It cites statistics showing that modern equipment has greatly reduced dolphin mortality from its height in the 1960s and that its ships carry independent observers who can verify dolphin safety.55 However, some environmental groups that monitor the tuna industry dispute these claims, stating that even if no dolphins are killed during the chasing and netting, some are wounded and later die. In other cases, they argue, young dolphin calves may not be able to keep pace and are separated from their mothers and later die. These groups contend that if the United States changes its labeling requirements, cans of Mexican tuna could be labeled as "dolphin-safe" when it is not. However, an industry spokesperson representing three major tuna processors in the United States, including StarKist, Bumblebee, and Chicken of the Sea, contends that U.S. companies would probably not buy Mexican tuna even if it is labeled as dolphin-safe because these companies "would not be in the market for tuna that is not caught in the dolphin-safe manner."56

WTO Tuna Dispute Proceedings

The tuna labeling dispute began over 10 years ago. In April 2000, the Clinton Administration lifted an embargo on Mexican tuna under relaxed standards for a dolphin-safe label. This was in accordance with internationally agreed procedures and U.S. legislation passed in 1997 that encouraged the unharmed release of dolphins from nets. However, a federal judge in San Francisco ruled that the standards of the law had not been met, and the Federal Appeals Court in San Francisco sustained the ruling in July 2001. Under the Bush Administration, the Commerce Department ruled on December 31, 2002, that the dolphin-safe label may be applied if qualified observers certify that no dolphins were killed or seriously injured in the netting process. Environmental groups, however, filed a suit to block the modification. On April 10, 2003, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California enjoined the Commerce Department from modifying the standards for the dolphin-safe label. On August 9, 2004, the federal district court ruled against the Bush Administration's modification of the dolphin-safe standards and reinstated the original standards in the 1990 Dolphin Protection Consumer Information Act. That decision was appealed to the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled against the Administration in April 2007, finding that the Department of Commerce did not base its determination on scientific studies of the effects of Mexican tuna fishing on dolphins.

In late October 2008, Mexico initiated WTO dispute proceedings against the United States, maintaining that U.S. requirements for Mexican tuna exporters prevent them from using the U.S. "dolphin-safe" label for its products. The United States requested that Mexico refrain from proceeding in the WTO and that the case be moved to the NAFTA dispute resolution mechanism. According to the USTR, however, Mexico "blocked that process for settling this dispute."57 In September 2011, a WTO panel determined that the objectives of U.S. voluntary tuna labeling provisions were legitimate and that any adverse effects felt by Mexican tuna producers were the result of choices made by Mexico's own fishing fleet and canners. However, the panel also found U.S. labeling provisions to be "more restrictive than necessary to achieve the objectives of the measures."58 The Obama Administration appealed the WTO ruling.

On May 16, 2012, the WTO's Appellate Body overturned two key findings from the September 2011 WTO dispute panel. The Appellate Body found that U.S. tuna labeling requirements violate global trade rules because they treat imported tuna from Mexico less favorably than U.S. tuna. The Appellate Body also rejected Mexico's claim that U.S. tuna labeling requirements were more trade-restrictive than necessary to meet the U.S. objective of minimizing dolphin deaths.59 The United States had a deadline of July 13, 2013, to comply with the WTO dispute ruling. In July 2013, the United States issued a final rule amending certain dolphin-safe labelling requirements to bring it into compliance with the WTO labeling requirements. On November 14, 2013, Mexico requested the establishment of a WTO compliance panel. On April 16, 2014, the chair of the compliance panel announced that it expected to issue its final report to the parties by December 2014.60 In April 2015, the panel ruled against the United States when it issued its finding that the U.S. labeling modifications unfairly discriminated against Mexico's fishing industry.61

On November 2015, a WTO appellate body found for a fourth time that U.S. labeling rules aimed at preventing dolphin bycatch violate international trade obligations. The United States expressed concerns with this ruling and stated that the panel exceeded its authority by ruling on acts and measures that Mexico did not dispute or were never applied.62 On March 16, 2016, Mexico announced that it would ask the WTO to sanction $472.3 million in annual retaliatory tariffs against the United States for its failure to comply with the WTO ruling. The United States counterargued that Mexico could seek authorization to suspend concessions of $21.9 million. On March 22, 2016, the United States announced that it would revise its dolphin-safe label requirements on tuna products to comply with the WTO decision. The revised regulations sought to increase labeling rules for tuna caught by fishing vessels in all regions of the world, and not just those operating in the region where Mexican vessels operate. The new rules did not modify existing requirements that establish the method by which tuna is caught in order for it to be labeled "dolphin-safe." The Humane Society International announced that it was pleased with U.S. actions to increase global dolphin protections.63

Sugar Disputes

2014 Mexican Sugar Import Dispute

On December 19, 2014, the U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) signed an agreement with the Government of Mexico suspending the U.S. countervailing duty (CVD) investigation of sugar imports from Mexico. The DOC signed a second agreement with Mexican sugar producers and exporters suspending an antidumping (AD) duty investigation on imports of Mexican sugar. The agreements suspending the investigations alter the nature of trade in sugar between Mexico and the United States by (1) imposing volume limits on U.S. sugar imports from Mexico and (2) setting minimum price levels on Mexican sugar.64

After the suspension agreement was announced, two U.S. sugar companies, Imperial Sugar Company and AmCane Sugar LLC, requested that the DOC continue the CVD and AD investigations on sugar imports from Mexico. The two companies filed separate submissions on January 16, 2015, claiming "interested party" status. The companies claimed they met the statutory standards to seek continuation of the probes. The submissions to the DOC followed requests to the ITC, by the same two companies, to review the two December 2014 suspension agreements.65 The ITC reviewed the sugar suspension agreements to determine whether they eliminate the injurious effect of sugar imports from Mexico. On March 19, 2015, the ITC upheld the agreement between the United States and Mexico that suspended the sugar investigations. Mexican Economy Minister Ildefonso Guajardo Villarreal praised the ITC decision, stating that it supported the Mexican government position.66

The dispute began on March 28, 2014, when the American Sugar Coalition and its members filed a petition requesting that the U.S. ITC and the DOC conduct an investigation, alleging that Mexico was dumping and subsidizing its sugar exports to the United States. The petitioners claimed that dumped and subsidized sugar exports from Mexico were harming U.S. sugar producers and workers. They claimed that Mexico's actions would cost the industry $1 billion in 2014. On April 18, 2014, the DOC announced the initiation of AD and CVD investigations of sugar imports from Mexico.67 On May 9, 2014, the ITC issued a preliminary report stating that there was a reasonable indication a U.S. industry was materially injured by imports of sugar from Mexico that were allegedly sold in the United States at less than fair value and allegedly subsidized by the Government of Mexico.68

In August 2014, the DOC announced in its preliminary ruling that Mexican sugar exported to the United States was being unfairly subsidized. Following the preliminary subsidy determination, the DOC stated that it would direct the U.S. Customs and Border Protection to collect cash deposits on imports of Mexican sugar. Based on the preliminary findings, the DOC imposed cumulative duties on U.S. imports of Mexican sugar, ranging from 2.99% to 17.01% under the CVD order. Additional duties of between 39.54% and 47.26% were imposed provisionally following the preliminary AD findings.69 The final determination in the two investigations was expected in 2015 and had not been issued when the suspension agreements were signed.

The Sweetener Users Association (SUA), which represents beverage makers, confectioners, and other food companies, argues that the case is "a diversionary tactic to distract from the real cause of distortion in the U.S. sugar market—the U.S. government's sugar program."70 It contends that between 2009 and 2012, U.S. sugar prices soared well above the world price because of the U.S. program, providing an incentive for sugar growers to increase production. According to the sugar users association, this resulted in a surplus of sugar and a return to lower sugar prices.71 The SUA has been a long-standing critic of the U.S. sugar program.72

Sugar and High Fructose Corn Syrup Dispute Resolved in 2006

In 2006, the United States and Mexico resolved a trade dispute involving sugar and high fructose corn syrup. The dispute involved a sugar side letter negotiated under NAFTA. Mexico argued that the side letter entitled it to ship net sugar surplus to the United States duty-free under NAFTA, while the United States argued that the sugar side letter limited Mexican shipments of sugar. In addition, Mexico complained that imports of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) sweeteners from the United States constituted dumping. It imposed antidumping duties for some time, until NAFTA and WTO dispute resolution panels upheld U.S. claims that the Mexican government colluded with the Mexican sugar and sweetener industries to restrict HFCS imports from the United States.

In late 2001, the Mexican Congress imposed a 20% tax on soft drinks made with corn syrup sweeteners to aid the ailing domestic cane sugar industry, and subsequently extended the tax annually despite U.S. objections. In 2004, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) initiated WTO dispute settlement proceedings against Mexico's HFCS tax, and following interim decisions, the WTO panel issued a final decision on October 7, 2005, essentially supporting the U.S. position. Mexico appealed this decision, and in March 2006, the WTO Appellate Body upheld its October 2005 ruling. In July 2006, the United States and Mexico agreed that Mexico would eliminate its tax on soft drinks made with corn sweeteners no later than January 31, 2007. The tax was repealed, effective January 1, 2007.

The United States and Mexico reached a sweetener agreement in August 2006. Under the agreement, Mexico can export 500,000 metric tons of sugar duty-free to the United States from October 1, 2006, to December 31, 2007. The United States can export the same amount of HFCS duty-free to Mexico during that time. NAFTA provides for the free trade of sweeteners beginning January 1, 2008. The House and Senate sugar caucuses expressed objections to the agreement, questioning the Bush Administration's determination that Mexico is a net-surplus sugar producer to allow Mexican sugar duty-free access to the U.S. market.73

Country-of-Origin Labeling (COOL)

The United States was involved in a country-of-origin labeling (COOL) trade dispute under the World Trade Organization (WTO) with Canada and Mexico for several years, which has now been resolved.74 Mexican and Canadian meat producers claimed that U.S. mandatory COOL requirements for animal products discriminated against their products. They contended that the labeling requirements created an incentive for U.S. meat processors to use exclusively domestic animals because they forced processors to segregate animals born in Mexico or Canada from U.S.-born animals, which was very costly. They argued that the COOL requirement was an unfair barrier to trade. A WTO appellate panel in June 2013 ruled against the United States. The United States appealed the decision. On May 18, 2015, the WTO appellate body issued findings rejecting the U.S. arguments against the previous panel's findings.75 Mexico and Canada were considering imposing retaliatory tariffs on a wide variety of U.S. exports to Mexico, including fruits and vegetables, juices, meat products, dairy products, machinery, furniture and appliances, and others.76

The issue was resolved when the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-113) repealed mandatory COOL requirements for muscle cut beef and pork and ground beef and ground pork. USDA issued a final rule removing country-of-origin labeling requirements for these products. The rule took effect on March 2, 2016.77 The estimated economic benefits associated with the final rule are likely to be significant, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).78 According to USDA, the estimated benefits for producers, processors, wholesalers, and retailers of previously covered beef and pork products are as much as $1.8 billion in cost avoidance, though the incremental cost savings are likely to be less as affected firms had adjusted their operations.

The dispute began on December 1, 2008, when Canada requested WTO consultations with the United States concerning certain mandatory labeling provisions required by the 2002 farm bill (P.L. 107-171) as amended by the 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-246). On December 12, 2008, Mexico requested to join the consultations. U.S. labeling provisions include the obligation to inform consumers at the retail level of the country of origin in certain commodities, including beef and pork.79

USDA labeling rules for meat and meat products had been controversial. A number of livestock and food industry groups opposed COOL as costly and unnecessary. Canada and Mexico, the main livestock exporters to the United States, argued that COOL had a discriminatory trade-distorting impact by reducing the value and number of cattle and hogs shipped to the U.S. market, thus violating WTO trade commitments. Others, including some cattle and consumer groups, maintained that Americans want and deserve to know the origin of their foods.80

In November 2011, the WTO dispute settlement panel found that (1) COOL treated imported livestock less favorably than U.S. livestock and (2) it did not meet its objective to provide complete information to consumers on the origin of meat products. In March 2012, the United States appealed the WTO ruling. In June 2012, the WTO's Appellate Body upheld the finding that COOL treats imported livestock less favorably than domestic livestock and reversed the finding that it does not meet its objective to provide complete information to consumers. It could not determine if COOL was more trade restrictive than necessary.

In order to meet a compliance deadline by the WTO, USDA issued a revised COOL rule on May 23, 2013, that required meat producers to specify on retail packaging where each animal was born, raised, and slaughtered, which prohibited the mixing of muscle cuts from different countries. Canada and Mexico challenged the 2013 labeling rules before a WTO compliance panel. The compliance panel sided with Canada and Mexico; the United States appealed the decision.81

NAFTA Trucking Issue

The implementation of NAFTA trucking provisions was a major trade issue between the United States and Mexico for many years because the United States delayed its trucking commitments under NAFTA. NAFTA provided Mexican commercial trucks full access to four U.S.-border states in 1995 and full access throughout the United States in 2000. Mexican commercial trucks have authority under the agreement to operate in the United States, but they cannot operate between two points within the country. This means that they can haul cross-border loads but cannot haul loads that originate and end in the United States. The proposed USMCA would cap the number of Mexican-domiciled carriers that can receive U.S. operating authority and would continue the prohibition on Mexican-based carriers hauling freight between two points within the United States. Mexican carriers that already have authority under NAFTA to operate in the United States would continue to be allowed to operate in the United States.

The United States delayed the implementation of NAFTA provisions because of safety concerns. The Mexican government objected to the delay and claimed that U.S. actions were a violation of U.S. commitments. A dispute resolution panel supported Mexico's position in February 2001. President Bush indicated a willingness to implement the provision, but the U.S. Congress required additional safety provisions in the FY2002 Department of Transportation Appropriations Act (P.L. 107-87). The United States and Mexico cooperated to resolve the issue over the years and engaged in numerous talks regarding safety and operational issues. The United States had two pilot programs on cross-border trucking to help resolve the issue: the Bush Administration's pilot program of 2007 and the Obama Administration's program of 2011.

A significant milestone in implementation of U.S. NAFTA commitments occurred on January 9, 2015, when the Department of Transportation's Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) announced that Mexican motor carriers would be allowed to conduct long-haul, cross-border trucking services in the United States. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters filed a lawsuit on March 20, 2015, in the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, seeking to halt FMCSA's move. On March 15, 2017, a three-judge panel heard the oral arguments of the legal challenge by the Teamsters, the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, and two other organizations. These organizations argued that the FMCSA did not generate enough inspection data during the pilot program to properly make a determination about expanding the program. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the lawsuit on June 29, 2017, stating that FMCSA has the law-given discretion to grant operating authority to Mexican carriers.82

Bush Administration's Pilot Program of 2007

On November 27, 2002, with safety inspectors and procedures in place, the Bush Administration began the process to open U.S. highways to Mexican truckers and buses. Environmental and labor groups went to court in early December to block the action. On January 16, 2003, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that full environmental impact statements were required for Mexican trucks to be allowed to operate on U.S. highways. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed that decision on June 7, 2004.

In February 2007, the Bush Administration announced a pilot project to grant Mexican trucks from 100 transportation companies full access to U.S. highways. In September 2007, the Department of Transportation (DOT) launched a one-year pilot program to allow approved Mexican carriers beyond the 25-mile commercial zone in the border region, with a similar program allowing U.S. trucks to travel beyond Mexico's border and commercial zone. Over the 18 months that the program existed, 29 motor carriers from Mexico were granted operating authority in the United States. Two of these carriers dropped out of the program shortly after being accepted, while two others never sent trucks across the border. In total, 103 Mexican trucks were used by the carriers as part of the program.83

In the FY2008 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 110-161), signed into law in December 2007, Congress included a provision prohibiting the use of FY2008 funding for the establishment of the pilot program. However, the DOT determined that it could continue with the pilot program because it had already been established. In March 2008, the DOT issued an interim report on the cross-border trucking demonstration project to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. The report made three key observations: (1) the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) planned to check every participating truck each time it crossed the border to ensure that it met safety standards; (2) there was less participation in the project than was expected; and (3) the FMCSA implemented methods to assess possible adverse safety impacts of the project and to enforce and monitor safety guidelines.84

In early August 2008, DOT announced that it would extend the pilot program for an additional two years. In opposition to this action, the House approved on September 9, 2008 (by a vote of 396 to 128), H.R. 6630, a bill that would have prohibited DOT from granting Mexican trucks access to U.S. highways beyond the border and commercial zone. The bill also would have prohibited DOT from renewing such a program unless expressly authorized by Congress. No action was taken by the Senate on the measure.

On March 11, 2009, the FY2009 Omnibus Appropriations Act (P.L. 111-8) terminated the pilot program. The FY2010 Consolidated Appropriations Act, passed in December 2009 (P.L. 111-117), did not preclude funds from being spent on a long-haul Mexican truck pilot program, provided that certain terms and conditions were satisfied. Numerous Members of Congress urged President Obama to find a resolution to the dispute in light of the effects that Mexico's retaliatory tariffs were having on U.S. producers (see section below on "Obama Administration's 2011 Pilot Program").

Mexico's Retaliatory Tariffs of 2009 and 2010

In response to the abrupt end of the pilot program, the Mexican government retaliated in 2009 by increasing duties on 90 U.S. products with a value of $2.4 billion in exports to Mexico. Mexico began imposing tariffs in March 2009 and, after reaching an understanding with the United States, eliminated them in two stages in 2011. The retaliatory tariffs ranged from 10% to 45% and covered a range of products that included fruit, vegetables, home appliances, consumer products, and paper.85 Subsequently, a group of 56 Members of the House of Representatives wrote to the then-United States Trade Representative, Ron Kirk, and DOT Secretary Ray LaHood requesting the Administration to resolve the trucking issue.86 The bipartisan group of Members stated that they wanted the issue to be resolved because the higher Mexican tariffs were having a "devastating" impact on local industries, especially in agriculture, and area economies in some states. One reported estimate stated that U.S. potato exports to Mexico had fallen 50% by value since the tariffs were imposed and that U.S. exporters were losing market share to Canada.87

A year after the initial 2009 list of retaliatory tariffs, the Mexican government revised the list of retaliatory tariffs to put more pressure on the United States to seek a settlement for the trucking dispute.88 The revised 2010 list added 26 products to and removed 16 products from the original list of 89, bringing the new total to 99 products from 43 states with a total export value of $2.6 billion. Products added to the list included several types of pork products, several types of cheeses, sweet corn, pistachios, oranges, grapefruits, apples, oats and grains, chewing gum, ketchup, and other products. The largest in terms of value were two categories of pork products, which had an estimated export value of $438 million in 2009. Products removed from the list included peanuts, dental floss, locks, and other products.89 The revised retaliatory tariffs were lower than the original tariffs and ranged from 5% to 25%. U.S. producers of fruits, pork, cheese, and other products that were bearing the cost of the retaliatory tariffs reacted strongly at the lack of progress in resolving the trucking issue and argued, both to the Obama Administration and to numerous Members of Congress, that they were potentially losing millions of dollars in sales as a result of this dispute.

In March 2011, President Obama and Mexican President Calderón announced an agreement to resolve the dispute. By October 2011, Mexico had suspended all retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports to Mexico.

Obama Administration's 2011 Pilot Program

In January 2011, the Obama Administration presented an "initial concept document" to Congress and the Mexican government for a new long-haul trucking pilot program with numerous safety inspection requirements for Mexican carriers. It would put in place a new inspection and monitoring regime in which Mexican carriers would have to apply for long-haul operating authority. The project involved several thousand trucks and would eventually bring as many vehicles as are needed into the United States.90

The concept document outlined three sets of elements: