Introduction

Foreign assistance is one of the tools the United States employs to advance U.S. interests in Latin America and the Caribbean. The focus and funding levels of aid programs change along with broader U.S. policy goals.1 Current aid programs reflect the diverse needs of the countries in the region (see Figure 1 for a map of Latin America and the Caribbean). Some countries receive the full range of U.S. assistance as they struggle with political, socioeconomic, and security challenges. Others have made major strides in consolidating democratic governance and improving living conditions; these countries no longer receive traditional U.S. development assistance but typically receive some U.S. support to address security challenges, such as transnational crime.

Congress authorizes and appropriates foreign assistance to the region and conducts oversight of aid programs and the executive branch agencies charged with managing them. The Trump Administration has proposed significant reductions in foreign assistance expenditures to shift resources to other budget priorities. The Administration also is reassessing the objectives of U.S. foreign assistance efforts, including those in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, Congress would have to approve any shifts in aid funding levels or priorities.

This report provides an overview of U.S. assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean. It examines historical and recent trends in aid to the region; the Trump Administration's FY2019 budget request for aid administered by the State Department, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Inter-American Foundation; and FY2019 foreign aid appropriations legislation. It also analyzes how the Administration's efforts to scale back assistance could affect U.S. policy in Latin America and the Caribbean.

|

Report Notes To more accurately compare the Administration's FY2019 foreign assistance request to previous years' appropriations, aid figures in this report (except where otherwise indicated) refer only to bilateral assistance that is managed by the State Department or the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and is requested for individual countries or regional programs. Nearly 70% of the assistance obligated by all U.S. agencies in Latin America and the Caribbean from FY2013 to FY2016 was provided through the foreign assistance accounts that are examined in this report. Nevertheless, there are several other sources of U.S. assistance to the region. Some countries in Latin America and the Caribbean receive U.S. assistance through State Department- and USAID-managed foreign assistance accounts, such as International Disaster Assistance, Migration and Refugee Assistance, and Transition Initiatives. Likewise, some nations receive assistance from U.S. agencies such as the Department of Defense, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the Peace Corps. Moreover, multilateral organizations that the United States supports financially, such as the Organization of American States, provide additional aid to some countries in the region. Those accounts and agencies are excluded from this analysis because they do not request assistance for individual countries and because country-level figures are not publicly available until after the fiscal year has passed. Source: USAID, Overseas Loans and Grants: Obligations and Loan Authorizations, July 1, 1945-September 30, 2016, 2017, p. 88, at http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pbaah600.pdf. |

|

|

Source: Map Resources, edited by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

Trends in U.S. Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean

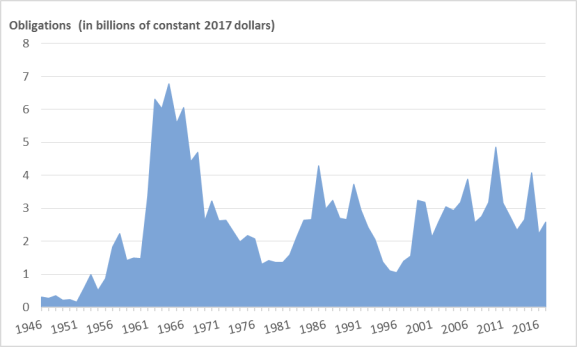

The United States has long been a major contributor of foreign assistance to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Between 1946 and 2017, the United States provided the region with more than $88 billion ($181 billion in constant 2017 dollars) of assistance.2 U.S. assistance to the region spiked in the early 1960s following the introduction of President John F. Kennedy's Alliance for Progress, an anti-poverty initiative that sought to counter Soviet and Cuban influence in the aftermath of Fidel Castro's 1959 seizure of power in Cuba. After a period of decline, U.S. assistance to the region increased again following the 1979 assumption of power by the leftist Sandinistas in Nicaragua. Throughout the 1980s, the United States provided considerable support to Central American governments battling leftist insurgencies to prevent potential Soviet allies from establishing political or military footholds in the region. U.S. aid flows declined in the mid-1990s, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Central American conflicts (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. U.S. Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean: FY1946-FY2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Foreign Aid Explorer: The Official Record of U.S. Foreign Aid, December 19, 2018, at https://explorer.usaid.gov/data.html. Notes: Includes aid obligations from all U.S. government agencies. Data for FY2018 are not yet available. |

U.S. foreign assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean began to increase once again in the late 1990s and remained on a generally upward trajectory through 2010. The higher levels of assistance were partially the result of increased spending on humanitarian and development assistance. In the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch in 1998, the United States provided extensive humanitarian and reconstruction assistance to several countries in Central America. The establishment of the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in 2003 and the Millennium Challenge Corporation in 2004 also provided a number of countries in the region with new sources of U.S. assistance.3 In addition, the United States provided significant assistance to Haiti in the aftermath of a massive earthquake in 2010.

Increased funding for counternarcotics and security programs also contributed to the rise in U.S. assistance. Beginning with President Bill Clinton and the 106th Congress in FY2000, successive Administrations and Congresses provided substantial amounts of foreign aid to Colombia and its Andean neighbors to combat drug trafficking in the region and end Colombia's long-running internal armed conflict. Spending received another boost in FY2008, when President George W. Bush joined with his Mexican counterpart to announce the Mérida Initiative, a package of U.S. counter-drug and anti-crime assistance for Mexico and Central America. In FY2010, Congress and the Obama Administration split the Central American portion of the Mérida Initiative into a separate Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) and created a similar program for the countries of the Caribbean known as the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI).

U.S. assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean began to decline again in FY2011. Although the decline was partially the result of reductions in the overall U.S. foreign assistance budget in the aftermath of the U.S. recession, it also reflected changes in the region. Due to stronger economic growth and more effective social policies, the percentage of people living in poverty in Latin America fell from 45% in 2002 to 30% in 2017.4 Some nations, such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay, are now in a position to provide technical assistance to other countries in the region. Other nations, such as Bolivia and Ecuador, have expelled U.S. personnel and opposed U.S. assistance projects, leading to the closure of USAID offices. Collectively, these changes have resulted in the U.S. government concentrating foreign assistance resources in fewer countries and sectors. Aid levels have rebounded since FY2014, largely due to a renewed focus on Central America in response to recent migration trends, but appropriations remain below the FY2008-FY2013 average.

Trump Administration's FY2019 Foreign Assistance Budget Request5

The Trump Administration requested $1.1 billion for Latin America and the Caribbean through foreign assistance accounts managed by the State Department and USAID in FY2019. That amount would have been $581 million, or 34%, less than the estimated $1.7 billion of assistance Congress appropriated for the region in FY2018 (see Table 1). The Administration also proposed eliminating the Inter-American Foundation—a small, independent U.S. foreign assistance agency that promotes grassroots development in Latin America and the Caribbean—and consolidating its programs into USAID. The proposed reductions for the region were slightly greater than the 28% reduction proposed for the global foreign aid budget.6 Congress ultimately did not adopt many of the Administration's proposed cuts (see "Legislative Developments," below).

Foreign Assistance Categories and Accounts7

About $515.9 million (46%) of the Administration's proposed FY2019 foreign aid budget for Latin America and the Caribbean was requested through a new Economic Support and Development Fund (ESDF). The ESDF foreign assistance account would have consolidated aid that currently is provided through the Development Assistance (DA) and Economic Support Fund (ESF) accounts to support democracy, the rule of law, economic reform, education, agriculture, and natural resource management.8 Whereas the DA account is often used for long-term projects to foster broad-based economic progress and social stability in developing countries, the ESDF account, like the ESF account, would focus more on countries and programs that are deemed critical to short-term U.S. security and strategic objectives. The FY2019 request included $296.4 million (36%) less funding for the ESDF account than was provided to the region through the DA and ESF accounts combined in FY2018.

Another $151.4 million (14%) of the Administration's FY2019 request for the region would have been provided through the two Global Health Programs (GHP) accounts. This amount includes $119.2 million requested through the State Department GHP account for HIV/AIDS programs and $32.2 million requested through the USAID GHP account to support maternal and child health, nutrition, and malaria programs. Under the FY2019 request for the region, funding for the State Department GHP account would have declined by $17.5 million (13%) and funding for the USAID GHP account would have declined by $31.2 million (49%) compared with the FY2018 estimate.

The remaining $442.9 million (40%) of the Administration's FY2019 request for Latin America and the Caribbean would have supported security assistance programs, including the following:

- $390 million requested through the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) account for counter-narcotics and civilian law enforcement efforts and projects intended to strengthen judicial institutions. INCLE funding for the region would have declined by $152.2 million (28%) compared with the FY2018 estimate.

- $21.9 million requested through the Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR) account, which funds efforts to counter global threats, such as terrorism and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and humanitarian demining programs. NADR funding would have declined by $1.7 million (7%) compared with the FY2018 estimate.

- $11.1 million requested through the International Military Education and Training (IMET) account to train Latin American and Caribbean military personnel. IMET funding would have declined by $1.5 million (12%) compared with the FY2018 estimate.

- $20 million requested through the Foreign Military Financing account to provide U.S.-made defense equipment to Colombia. FMF funding would have declined by $66 million (77%) compared with the FY2018 estimate.

Table 1. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean by Account: FY2014-FY2019 Request

(appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

Account |

FY2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

DA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

ESF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

ESDF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

GHP (USAID) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

GHP (State) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

P.L. 480 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

INCLE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

NADR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

IMET |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

FMF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, FY2016-FY2019, at http://www.state.gov/f/releases/iab/index.htm; and "FY 2018 653(a) Allocations – FINAL," 2018.

Notes: DA = Development Assistance; ESF = Economic Support Fund; ESDF=Economic Support and Development Fund; GHP = Global Health Programs; P.L. 480 = Food for Peace/Food Aid; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; IMET = International Military Education and Training; and FMF = Foreign Military Financing.

a. The FY2019 request consolidates development and economic assistance into a new ESDF foreign assistance account. The FY2019 ESDF request is compared with the combined FY2018 DA and ESF amounts.

b. In FY2017 and FY2018, Congress appropriated an additional $9 million for ESF that is not included in this amount, because it was provided as multilateral assistance through the Organization of American States (OAS). In prior years, such assistance was provided through the International Organizations and Programs (IO&P) foreign assistance account.

Major Country and Regional Programs

The Trump Administration's FY2019 foreign assistance request would have reduced funding for nearly every country and regional program in Latin America and the Caribbean (see Table 2). Some of the most notable reductions that the Administration proposed are discussed below.

The FY2019 request included $435.5 million to continue the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, which would have been a $191 million (30%) cut compared with the FY2018 estimate.9 The strategy is designed to address the underlying conditions driving irregular migration from the Central America to the United States by promoting good governance, economic prosperity, and improved security in the region. The request included $252.8 million for CARSI (-21%), $45.7 million for El Salvador (-21%), $69.4 million for Guatemala (-42%), $65.8 million for Honduras (-18%), and $1.8 million combined for Belize, Costa Rica, and Panama (-82%). It did not include any democracy assistance to support civil society groups in Nicaragua; such assistance totaled $10 million in FY2018.

Colombia would have remained the single largest recipient of U.S. assistance in Latin America and the Caribbean under the Administration's FY2019 request; however, aid would have fallen to $265.4 million—a $125.8 million (32%) reduction compared with the FY2018 estimate. Colombia has received significant amounts of U.S. assistance to support counternarcotics and counterterrorism efforts since FY2000. The FY2019 request included funds to support implementation of the Colombian government's peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC); it sought to foster reconciliation within Colombian society, expand state presence to regions historically under FARC control, and support rural economic development in marginalized communities. The request also included funds to support Colombia's drug eradication and interdiction efforts.10

Haiti, which has received high levels of aid for many years as a result of its significant development challenges, would have remained the second-largest recipient of U.S. assistance in the region in FY2019 under the Administration's request. U.S. assistance increased significantly after a massive earthquake struck Haiti in 2010 but has gradually declined from those elevated levels. The Administration's FY2019 request would have provided $170.5 million to Haiti to improve food security, increase economic opportunity, promote good governance, and address health challenges (particularly HIV/AIDS). This would have been a $13.9 million (8%) cut compared with the FY2018 estimate.11

Mexico would have received $78.9 million of assistance under the FY2019 request, which would have been a $73.8 million (48%) cut compared with the FY2018 estimate. Mexico traditionally had not been a major U.S. aid recipient due to its middle-income status, but it began receiving larger amounts of counternarcotics and anti-crime assistance through the Mérida Initiative in FY2008. The Administration's FY2019 request for Mexico included funds to strengthen the rule of law; secure borders and ports; and combat transnational organized crime, including opium poppy cultivation and heroin production.12

The FY2019 request included $36.2 million for the CBSI, which would have been a $21.5 million (37%) cut compared with the FY2018 estimate. The CBSI funds maritime and aerial security cooperation, law enforcement capacity building, border and port security, justice-sector reform, and crime prevention programs in the Caribbean.13

Table 2. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean by Country or Regional Program: FY2014-FY2019 Request

(appropriations in thousands of current U.S. dollars)

|

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 (estimate) |

FY2019 (request) |

% Change FY2018-FY2019 |

|

|

Argentina |

589 |

576 |

579 |

624 |

2,900 |

600 |

-79% |

|

Bahamas |

172 |

200 |

207 |

173 |

100 |

200 |

+100% |

|

Belize |

1,234 |

1,058 |

1,243 |

1,241 |

1,250 |

200 |

-84% |

|

Bolivia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

— |

|

Brazil |

13,858 |

11,586 |

12,858 |

11,690 |

11,425 |

575 |

-95% |

|

Chile |

1,082 |

1,032 |

670 |

689 |

400 |

500 |

+25% |

|

Colombia |

330,601 |

307,776 |

299,434 |

386,269 |

391,253 |

265,400 |

-32% |

|

Costa Rica |

1,731 |

1,673 |

1,819 |

5,718 |

5,725 |

400 |

-93% |

|

Cuba |

20,000 |

20,000 |

20,000 |

20,000 |

20,000 |

10,000 |

-50% |

|

Dominican Republic |

23,248 |

22,350 |

21,615 |

13,736 |

20,209 |

5,045 |

-75% |

|

Ecuador |

2,000 |

0 |

2,000 |

1,789 |

1,789 |

1,500 |

-16% |

|

El Salvador |

21,631 |

46,549 |

67,900 |

72,759 |

57,735 |

45,700 |

-21% |

|

Guatemala |

65,278 |

113,099 |

131,226 |

140,446 |

120,069 |

69,409 |

-42% |

|

Guyana |

6,904 |

4,692 |

243 |

277 |

200 |

200 |

0% |

|

Haiti |

300,796 |

242,922 |

190,744 |

184,426 |

184,341 |

170,455 |

-8% |

|

Honduras |

41,847 |

71,191 |

98,250 |

95,260 |

79,800 |

65,750 |

-18% |

|

Jamaica |

6,670 |

5,573 |

5,065 |

10,597 |

1,600 |

500 |

-69% |

|

Mexico |

206,768 |

165,168 |

160,156 |

138,566 |

152,660 |

78,910 |

-48% |

|

Nicaragua |

8,400 |

12,054 |

10,000 |

9,679 |

10,000 |

0 |

-100% |

|

Panama |

2,986 |

4,077 |

3,346 |

3,271 |

3,225 |

1,200 |

-63% |

|

Paraguay |

7,528 |

7,980 |

8,620 |

6,150 |

4,400 |

1,900 |

-57% |

|

Peru |

82,649 |

84,079 |

74,898 |

64,473 |

73,734 |

47,400 |

-36% |

|

Suriname |

212 |

199 |

215 |

269 |

200 |

100 |

-50% |

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

179 |

308 |

325 |

343 |

300 |

150 |

-50% |

|

Uruguay |

725 |

550 |

499 |

498 |

400 |

300 |

-25% |

|

Venezuela |

4,298 |

4,256 |

6,500 |

7,000 |

15,000 |

9,000 |

-40% |

|

Barbados and Eastern Caribbean |

16,734 |

24,692 |

26,425 |

26,629 |

24,195 |

9,639 |

-60% |

|

USAID Caribbean Development |

0 |

4,000 |

4,000 |

3,000 |

4,000 |

0 |

-100% |

|

USAID Central America Regional |

33,492 |

50,762 |

39,761 |

38,316 |

19,930 |

5,419 |

-73% |

|

USAID South America Regional |

16,500 |

12,000 |

12,000 |

14,000 |

18,065 |

0 |

-100% |

|

USAID Latin America and Caribbean Regional |

29,050 |

22,500 |

28,360 |

26,700 |

51,600 |

30,050 |

-42% |

|

State Western Hemisphere Regional |

230,449 |

341,938 |

478,668 |

425,471 |

414,795 |

289,810 |

-30% |

|

[CARSI] |

[161,500] |

[270,000] |

[348,500] |

[329,225] |

[319,225] |

[252,800] |

-21% |

|

[CBSI] |

[63,500] |

[58,500] |

[57,721] |

[57,700] |

[57,700] |

[36,200] |

-37% |

|

Total |

1,477,611 |

1,584,840 |

1,707,626 |

1,710,059 |

1,691,300 |

1,110,312 |

-34% |

Sources: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, FY2016-FY2019, at http://www.state.gov/f/releases/iab/index.htm; U.S. Department of State, "FY 2018 653(a) Allocations – FINAL," 2018; and "Explanatory Statement Submitted by Mr. Frelinghuysen, Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, Regarding the House Amendment to Senate Amendment on H.R. 1625," Congressional Record, vol. 164, no. 50—book III (March 22, 2018), p. H2851.

Notes: CARSI = Central America Regional Security Initiative; CBSI = Caribbean Basin Security Initiative. CARSI and CBSI are funded through the State Western Hemisphere Regional program. USAID and State Department regional programs fund region-wide initiatives as well as activities that cross borders or take place in non-presence countries.

Inter-American Foundation

In addition to the proposed reductions to State Department and USAID-managed assistance for the region, discussed above, the Trump Administration's FY2019 budget request proposed eliminating the Inter-American Foundation (IAF) and consolidating its programs into USAID. The IAF is an independent U.S. foreign assistance agency established through the Foreign Assistance Act of 1969 (22 U.S.C. §290f). Congress created the agency after conducting a comprehensive review of previous assistance efforts and determining that programs at the government-to-government level had largely failed to promote social and civic change in the region despite fostering economic growth.14 With annual appropriations of $22.5 million in recent years, the IAF provides grants and other targeted assistance directly to the organized poor to foster economic and social development and to encourage civic engagement in their communities. The IAF is active in 20 countries in the region—including eight countries in which USAID no longer has a presence—and has focused particularly on migrant-sending communities in Central America since 2014.

The Trump Administration asserted that merging the IAF's small grants programs into USAID would "better integrate them with USAID's existing global development programs, more cohesively serve U.S. foreign policy objectives, and increase organizational efficiencies through reducing duplication and overhead."15 The FY2019 request included $3.5 million to conduct an orderly IAF closeout and $20 million under USAID's Latin America and Caribbean Regional program to continue providing small grants to poor and remote communities throughout the region (see Table 3). Opponents of the merger noted that Congress specifically created the IAF as an alternative to other U.S. agencies. They argued that USAID would not be able to maintain the IAF's distinct model and flexibility, which have allowed it to invest in innovative projects and work with groups that otherwise would be unable or unwilling to partner with the U.S. government.

Table 3. Inter-American Foundation Appropriations: FY2014-FY2019 Request

(appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 (estimate) |

FY2019 (request) |

% Change FY2018-FY2019 |

|

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

22.5 |

3.5 |

-84% |

Sources: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, FY2016-FY2019, at http://www.state.gov/f/releases/iab/index.htm; and "Explanatory Statement Submitted by Mr. Frelinghuysen, Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, Regarding the House Amendment to Senate Amendment on H.R. 1625," Congressional Record, vol. 164, no. 50—book III (March 22, 2018), p. H2851.

Notes: The Inter-American Foundation (IAF) has received some additional funding through inter-agency transfers. For example, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) included a $10 million transfer from the Development Assistance account to the IAF to support the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America.

Legislative Developments

On February 15, 2019, nearly four and a half months into the fiscal year, President Trump signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6). Division F of the act—the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2019—includes funding for foreign assistance programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. The measure was preceded by three short-term continuing resolutions (P.L. 115-245, P.L. 115-298, and P.L. 116-5), which funded foreign assistance programs at the FY2018 level, and a 35-day lapse in appropriations from December 22, 2018, to January 25, 2019. Although the House and Senate Appropriations Committees had approved their FY2019 foreign assistance appropriations measures (H.R. 6385 and S. 3108, respectively) in June 2018, neither bill received floor consideration prior to the end of the 115th Congress.

P.L. 116-6 and the accompanying joint explanatory statement do not specify foreign assistance appropriations levels for every Latin American and Caribbean nation. Nevertheless, the amounts designated for key U.S. initiatives in Central America, Colombia, and Mexico significantly exceed the Administration's request (see Table 4).

Table 4. U.S. Foreign Assistance for Select Countries and Initiatives: FY2019 Appropriations Legislation

(appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

|

|

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

FY2019 |

|||||||||||

|

Caribbean Basin Security Initiative |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Colombia |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Cuba |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Inter-American Foundation |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Mexico |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Venezuela |

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: U.S. Department of State, "FY 2018 653(a) Allocations – FINAL," 2018; "Explanatory Statement Submitted by Mr. Frelinghuysen, Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, Regarding the House Amendment to Senate Amendment on H.R. 1625," Congressional Record, vol. 164, no. 50—book III (March 22, 2018), p. H2851; U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Appendix 2, Fiscal Year 2019, March 14, 2018; H.Rept. 115-829; S.Rept. 115-282; and the joint explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 116-6.

Note: These figures include amounts specified in the bill texts, committee reports, and explanatory statements.

Central America. According to the joint explanatory statement, the act provides $527.6 million to continue implementation of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America. That amount is $92 million more than the Administration requested but $99 million less than Congress appropriated for the initiative in FY2018. Unlike previous years, the measure provides the Secretary of State with significant flexibility to decide how to allocate the funds among the nations of the region. The joint explanatory statement notes that the Secretary of State should take into account the political will of Central American governments, including their demonstrated commitment to implement reforms "to reduce illegal migration and reduce corruption and impunity."

Colombia. The act provides "not less than" $418.3 million for Colombia, which is nearly $153 million more than the Administration requested and $27 million more than Congress appropriated in FY2018. The joint explanatory statement notes that the additional funding for FY2019, appropriated through the INCLE account, is intended to "bolster Colombia's drug eradication and interdiction efforts and enhance rural security."

Mexico. According to the joint explanatory statement, the act provides $162.7 million for Mexico. That amount is nearly $84 million more than the Administration requested and $10 million more than Congress appropriated for Mexico in FY2018. The additional funding for FY2019 is intended to support security and rule-of-law efforts, such as "programs to assist the Government of Mexico in securing its borders and reducing poppy cultivation and heroin and synthetic drug production."

Venezuela. The act provides "not less than" $17.5 million for programs to promote democracy and the rule of law in Venezuela. The joint explanatory statement notes that the legislation also includes assistance for Venezuelan refugees and migrants who have been forced to leave the country.

Inter-American Foundation. The act provides $22.5 million for the IAF, which is the same amount Congress appropriated for the agency in FY2018. The joint explanatory statement designates an additional $10 million, appropriated through the DA account, as a transfer to the IAF to carry out programs in Central America.

Implications for U.S. Policy

The Trump Administration's efforts to scale back U.S. foreign assistance could have significant implications for U.S. policy in Latin America and the Caribbean in the coming years. In particular, they could accelerate U.S. efforts to transition countries in the region away from traditional development assistance and toward other forms of bilateral engagement. They also could result in the Department of Defense (DOD) taking on a larger role in U.S. security cooperation with the region. Moreover, many argue the Administration's proposed foreign assistance cuts, combined with other U.S. policy shifts and the region's growing economic ties with other countries, such as China, could contribute to a relative decline in U.S. influence in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Aid Transitions

Over the past three decades, many Latin American and Caribbean countries have made major strides in consolidating democratic governance and improving living conditions for their citizens. As nations have achieved more advanced levels of development, the U.S. government has reduced the amount of assistance it provides to them while attempting to sustain long-standing relationships through other forms of engagement. Budget cuts often have accelerated this process by forcing U.S. agencies to refocus their assistance efforts on fewer countries. In the mid-1990s, for example, budget constraints compelled USAID to close its field offices in Argentina, Belize, Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay. Similarly, budget cuts in the aftermath of the 2007-2009 U.S. recession contributed to USAID's decision to close its field offices in Guyana and Panama.

The Trump Administration's desire to reduce foreign assistance funding could contribute to a new round of aid transitions. The FY2019 budget request would have zeroed out traditional development assistance for Brazil, Jamaica, and Nicaragua, and would have reduced it significantly for several other countries in the region. Although it appears as though many of those reductions were not enacted in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6), the Administration may push for further cuts in the coming years. The Administration's National Security Strategy, released in December 2017, asserts that the United States "will shift away from a reliance on assistance based on grants to approaches that attract private capital and catalyze private sector activity."16 Likewise, USAID has begun to reorient all of its country partnerships around the concept of "self-reliance," placing a greater emphasis on supporting countries' abilities to plan, finance, and implement solutions to their own development challenges.17

Some development experts caution that such transitions should be done in a strategic manner to ensure that partner countries are able to sustain the progress that has been made with past U.S. investments and to prevent ruptures in bilateral relations that could be exploited by competing powers or compromise U.S. interests. These experts argue that successful transitions require careful planning and close coordination across the U.S. government, as well as with partner-country governments, local stakeholders, and other international donors. In their view, a timeline of three to five years, at a minimum, is necessary for the transition process.18

A decision to no longer appropriate new foreign aid funds for a given country would not necessarily lead to an abrupt end to ongoing U.S. assistance programs. In recent years, Congress has appropriated most aid for Latin America and the Caribbean through foreign assistance accounts that provide the State Department and USAID with up to two fiscal years to obligate the funds and an additional four years to expend them.19 As a result, U.S. agencies often have a pipeline of previously appropriated funds available to be expended on assistance programs.

If aid transitions do occur, the United States could remain engaged with its partners in the region in several ways. As large-scale development programs are closed out, the U.S. government could use smaller, more nimble programs, such as those managed by the IAF, to maintain its presence in remote areas and continue to build relationships with local leaders. As grant assistance is withdrawn, the U.S. government could help partner countries mobilize private capital by entering into trade and investment agreements or by providing loan guarantees and technical assistance through the newly authorized U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC).20 As former aid recipients look to share their development expertise with other nations, the U.S. government could enter into trilateral cooperation initiatives to jointly fund and implement programs in third countries that remain priorities for U.S. assistance.

Congress has demonstrated an interest in influencing the pace and shape of aid transitions. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) directed the USAID Administrator to submit a report to Congress describing the conditions and benchmarks under which aid transitions may occur, the actions required by USAID to facilitate such transitions, descriptions of the associated costs, and plans for ensuring post-transition development progress.21 The report, submitted in October 2018, notes that USAID has selected 17 publicly available, third-party metrics to help the agency assess the relative self-reliance of every country. If, after taking into account additional country-specific information, the agency determines a country is ready to transition, USAID is to begin an in-depth, consultative assessment process to consider potential models for continued partnership. The results of that process are to inform an implementation plan that will lay out the activities, resources, and sequencing needed to ensure a successful transition. Jamaica is one of two countries worldwide that USAID is using to test the new strategic transition process.22

Congress could require USAID to provide additional information as the agency continues to develop its framework for strategic transitions and moves forward with the pilot project in Jamaica. For example, in the 115th Congress, H.R. 6385 would have required the USAID Administrator to regularly consult with Congress and development stakeholders on "efforts to transition nations from assistance recipients to enduring diplomatic, economic, and security partners."

Changes in Security Cooperation

The Trump Administration's approach toward Latin America and the Caribbean has focused heavily on U.S. national security objectives. For example, the Administration described the FY2019 foreign assistance request for the region as an effort to "break the power of transnational criminal organizations and networks; shut down the illicit pathways used to traffic humans, drugs, money and weapons; and address the underlying causes that contribute to outmigration."23 The Administration's FY2019 budget proposal, however, would have reduced State Department-managed security assistance to the region (INCLE, NADR, IMET, and FMF) by 33% compared with the FY2018 estimate.

Some analysts have noted that any cuts to State Department-managed security assistance programs in Latin America and the Caribbean could be offset by increased support from DOD.24 Congress has authorized DOD to provide a wide range of security assistance to foreign nations (referred to as security cooperation by DOD) including many activities that overlap with those traditionally managed by the State Department.25 For example, 10 U.S.C. §333 authorizes DOD, with the concurrence of the State Department, to train and equip foreign security forces for counterterrorism operations, counter-weapons of mass destruction operations, counter-illicit drugs operations, counter-transnational organized crime operations, and maritime and border security operations, among other purposes.

Given the number of security challenges the United States faces around the globe, however, it is unclear whether DOD would devote increased funding to security cooperation in Latin America and the Caribbean. As a result of a provision (10 U.S.C. §381) enacted as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2017 (P.L. 114-328), DOD is required to submit formal, consolidated budget requests for security cooperation efforts, including the specific countries or regions where they are to take place, "to the extent practicable." For FY2019, DOD requested $55.1 million for security cooperation in the areas of responsibility of U.S. Northern Command and U.S. Southern Command, which encompass the Latin American and Caribbean region.26 That amount would be slightly less than the estimated $58.6 million DOD obligated for security cooperation in the region in FY2018.27 Both of those figures exclude funds for drug interdiction and counter-drug activities, which account for the vast majority of DOD security cooperation funding for Latin America and the Caribbean. In FY2017 (the most recent year for which data are available), DOD obligations for drug interdiction and counter-drug activities in the region totaled $210.8 million.28

The exclusion of drug interdiction and counter-drug activities and the lack of country-by-country data in DOD's FY2019 security cooperation request make it difficult to assess the scope of DOD's planned activities in the region and the extent to which those activities may overlap with State Department security assistance programs. This lack of information may hinder congressional efforts to establish budget priorities and shape the relative balance of U.S. assistance in Latin America and the Caribbean. It also may weaken Congress's ability to incentivize policy changes in recipient nations as State Department-managed assistance withheld to comply with legislative conditions could be replaced with less transparent DOD support. DOD asserts that "in the long-term" it intends to include "some budgeting figures by country."29 Congress could use legislation to clarify the breadth of information it expects to receive from DOD in its annual security cooperation budget requests.

Potential Decline in U.S. Influence

Although the relative importance of foreign assistance in U.S. relations with Latin American and Caribbean nations has declined since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. government continues to use assistance to advance key policy initiatives in the region. In recent years, U.S. assistance has supported efforts to reduce illicit drug production and end the long-running internal conflict in Colombia, combat transnational organized crime in Mexico, and address the root causes that drive unauthorized migration to the United States from Central America. This assistance has enabled the U.S. government to influence partner countries' policies, including the extent to which they dedicate resources to activities that they otherwise may not consider top priorities.

Some analysts and Latin American officials view the Administration's efforts to cut foreign aid as part of a broader trend of U.S. disengagement from the region. They note that President Trump withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement and imposed tariffs on several Latin American nations, has been slow to fill diplomatic posts in the region, and was the first U.S. president in 25 years to skip the triennial Summit of the Americas.30 They contend that this has created a leadership vacuum in the region that other powers have begun to fill. For example, some analysts warn that China, which has provided more than $140 billion in state-backed finance to Latin American and Caribbean nations since 2005,31 has begun to leverage its significant commercial ties into other forms of power that could come at the expense of the United States.32 Others note that it may not be a zero-sum game and that the region's increased ties with China do not necessarily portend a loss of U.S. influence.33

Research suggests that foreign aid can influence perceptions of U.S. leadership,34 which have declined significantly in Latin America and the Caribbean over the past two years. In 2018, 31% of the region approved of "the job performance of the leadership of the United States," an 18-point decline compared to 2016.35 Consistently high disapproval ratings could constrain Latin American and Caribbean leaders' abilities to support Trump Administration initiatives and conclude agreements with the United States.36

Many in Congress also have expressed concerns that significant foreign assistance cuts could weaken U.S. influence around the world. In H.Rept. 115-829, for example, the House Appropriations Committee asserted that "the magnitude of the reductions proposed for United States diplomatic and development operations and programs in the fiscal year 2019 request would be counterproductive to the economic and security interests of the nation and would undermine our relationships with key partners and allies." Similarly, in S.Rept. 115-282, the Senate Appropriations Committee asserted that the "proposed reduction to the International Affairs budget…reinforces the perception that the United States is retreating from its preeminent role as the world's superpower." These concerns may have influenced Congress's decision not to adopt many of the Administration's proposed foreign assistance cuts for FY2019.

Appendix A. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean by Account and Country or Regional Program: FY2017

Table A-1. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean: FY2017

(appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

DA |

ESFa |

GHP-USAID |

GHP-State |

P.L. 480 |

INCLE |

NADR |

IMET |

FMF |

Total |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Argentina |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bahamas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bolivia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brazil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colombia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cuba |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dominican Republic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ecuador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Guyana |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Haiti |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jamaica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mexico |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Paraguay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Peru |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Suriname |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Trinidad & Tobago |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Uruguay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Venezuela |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Barbados & Eastern Caribbean |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Caribbean Developmentb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Central America Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID South America Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Latin America and Caribbean Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

State Western Hemisphere Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

[CARSI]c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

[CBSI]c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Appendix 2, Fiscal Year 2019, March 14, 2018.

Notes: Figures may not sum to totals due to rounding. DA = Development Assistance; ESF = Economic Support Fund; GHP = Global Health Programs; P.L. 480 = Food for Peace/Food Aid; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; IMET = International Military Education and Training; FMF = Foreign Military Financing; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development; CARSI = Central America Regional Security Initiative; and CBSI = Caribbean Basin Security Initiative.

a. This amount does not include an additional $9 million of ESF for the region that Congress appropriated in FY2017, because it was provided as multilateral assistance through the Organization of American States.

b. USAID and State Department regional programs fund region-wide initiatives as well as activities that cross borders or take place in non-presence countries.

c. CARSI and CBSI are funded through the State Western Hemisphere Regional program.

Appendix B. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean by Account and Country or Regional Program: FY2018 Estimate

Table B-1. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean: FY2018 Estimate

(estimated appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

DA |

ESFa |

GHP-USAID |

GHP-State |

P.L. 480 |

INCLE |

NADR |

IMET |

FMF |

Totala |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Argentina |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bahamas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bolivia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brazil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colombia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cuba |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dominican Republic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ecuador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Guyana |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Haiti |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jamaica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mexico |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Paraguay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Peru |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Suriname |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Trinidad & Tobago |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Uruguay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Venezuela |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Barbados & Eastern Caribbean |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Caribbean Developmentb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Central America Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID South America Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Latin America and Caribbean Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

State Western Hemisphere Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

[CARSI]b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

[CBSI]b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, "FY 2018 653(a) Allocations – FINAL," 2018; and "Explanatory Statement Submitted by Mr. Frelinghuysen, Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, Regarding the House Amendment to Senate Amendment on H.R. 1625," Congressional Record, vol. 164, no. 50—book III (March 22, 2018), p. H2851.

Notes: Figures may not sum to totals due to rounding. DA = Development Assistance; ESF = Economic Support Fund; GHP = Global Health Programs; P.L. 480 = Food for Peace/Food Aid; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; IMET = International Military Education and Training; FMF = Foreign Military Financing; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development; CARSI = Central America Regional Security Initiative; and CBSI = Caribbean Basin Security Initiative.

a. This amount does not include an additional $9 million of ESF for the region that Congress appropriated in FY2018, because it was provided as multilateral assistance through the Organization of American States.

b. USAID and State Department regional programs fund region-wide initiatives as well as activities that cross borders or take place in non-presence countries

c. CARSI and CBSI are funded through the State Western Hemisphere Regional program.

Appendix C. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean by Account and Country or Regional Program: FY2019 Request

Table C-1. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean: FY2019 Request

(estimated appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

ESDFa |

GHP-USAID |

GHP-State |

P.L. 480 |

INCLE |

NADR |

IMET |

FMF |

Total |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Argentina |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Bahamas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Bolivia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Brazil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Chile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Colombia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Cuba |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Dominican Republic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Ecuador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Guyana |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Haiti |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Jamaica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Mexico |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Paraguay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Peru |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Suriname |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Trinidad & Tobago |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Uruguay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Venezuela |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Barbados & Eastern Caribbean |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Caribbean Developmentb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Central America Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID South America Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Latin America and Caribbean Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

State Western Hemisphere Regionalb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

[CARSI]c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

[CBSI]c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Appendix 2, Fiscal Year 2019, March 14, 2018.

Notes: Figures may not sum to totals due to rounding. ESDF = Economic Support and Development Fund; GHP = Global Health Programs; P.L. 480 = Food for Peace/Food Aid; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; IMET = International Military Education and Training; FMF = Foreign Military Financing; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development; CARSI = Central America Regional Security Initiative; and CBSI = Caribbean Basin Security Initiative.

a. The FY2019 request would consolidate assistance previously provided through the Development Assistance and Economic Support Fund accounts into a new ESDF account.

b. USAID and State Department regional programs fund region-wide initiatives as well as activities that cross borders or take place in non-presence countries.

c. CARSI and CBSI are funded through the State Western Hemisphere Regional program.