Political and Economic Situation

Political Background and Colombia's Internal Conflict

Colombia, one of the oldest democracies in the Western Hemisphere and the third most populous Latin American country, has endured a multisided civil conflict for more than five decades until President Juan Manuel Santos declared the conflict over in August 2017 at the end of a U.N.-monitored disarmament.1 According to the National Center for Historical Memory 2013 report, presented to the Colombian government as part of the peace process to end the fighting, some 220,000 Colombians died in the armed conflict through 2012, 81% of them civilians.2

|

Colombia at a Glance Population: 49 million (2017, IMF) Area: 439,736 sq. miles, slightly less than twice the size of Texas GDP: $309.2 billion (2017, current prices, IMF) Per Capita Income: $6,273 (2017, current prices, IMF) Life Expectancy: 75 (2016 est., CIA) Ethnic Makeup: Mestizos 49%, Caucasian 37%, Afro-Colombian 10.6%, and Indigenous 3.4%. (Colombian Ministry of the Environment, 2017) Key Trading Partners: United State (26.9%), China (12.8%) Mexico (5.9%), (2017, total trade, GTA) Legislature: Bicameral Congress, with 102-member Senate and 166-member Lower House. (12 additional seats set aside in 2018, due to constitutional change and peace accord requirements, so 280 seats in the FY2018-2022 Congress) Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF); U.S. Department of State; Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); Global Trade Atlas (GTA), accessed March 2018. |

The report also provided statistics quantifying the scale of the conflict, which has taken a huge toll on Colombian society: more than 23,000 selective assassinations between 1981 and 2012; internal displacement of more than 5 million Colombians due to land seizure and violence; 27,000 kidnappings between 1970 and 2010; and 11,000 deaths or amputees from anti-personnel land mines laid primarily by Colombia's main insurgent guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).3 To date, more than 8 million Colombians, or roughly 15% of the population, have registered as conflict victims.

Although the violence has scarred Colombia, the country has achieved a significant turnaround. Once considered a likely candidate to become a failed state, Colombia, over the past two decades, has overcome much of the violence that had clouded its future. For example, between 2000 and 2016, Colombia saw a 94% decrease in kidnappings and a 53% reduction in homicides (below 25 per 100,000 in 2016).4 Coupled with success in lowering violence, Colombia has opened its economy and promoted trade, investment, and growth. Colombia has become one of Latin America's most attractive locations for foreign direct investment. Yet, after steady growth over several years, Colombia's economy slowed to 3.1% growth in 2015 and declined to 1.7% in 2017.5 Many analysts identified Colombia's dependence on oil and other commodity exports as the primary cause.

Between 2012 and 2016, the Colombian government held formal peace talks with the FARC, Colombia's largest guerrilla organization. Upon taking office for a second term in August 2014, President Santos declared peace, equality, and education as his top priorities, although achieving the peace agreement remained his major focus. In August 2016, the government and FARC negotiators announced they had concluded their talks and achieved a 300-page peace agreement. The accord was subsequently narrowly defeated in a popular referendum held in early October 2016, but was revised by the Santos government and agreed to by the FARC and then ratified by the Colombian Congress at the end of November 2016.

Roots of the Conflict

The Colombian conflict predates the formal founding of the FARC in 1964, as the FARC had its beginnings in the peasant self-defense groups of the 1940s and 1950s. Colombian political life has long suffered from polarization and violence based on the significant disparities and inequalities suffered by landless peasants in the country's peripheral regions. In the late 19th century and a large part of the 20th century, the elite Liberal and Conservative parties dominated Colombian political life. Violence and competition between the parties erupted in a period of extreme violence in Colombia, known as La Violencia, set off in 1948 by the assassination of Liberal presidential candidate Jorge Gaitán. The violence continued for the next decade.

After a brief military rule (1953-1958), the Liberal and Conservative parties agreed to a form of coalition governance, known as the National Front. Under the arrangement, the presidency of the country alternated between Conservatives and Liberals, each holding office in turn for four-year intervals. This form of government continued for 16 years (1958-1974). The power-sharing formula did not resolve the tension between the two historic parties, and many leftist, Marxist-inspired insurgencies took root in Colombia, including the FARC, launched in 1964, and the smaller National Liberation Army (ELN), which formed the following year. The FARC and ELN conducted kidnappings, committed serious human rights violations, and carried out a campaign of terrorist activities to pursue their goal of unseating the central government in Bogotá.

Rightist paramilitary groups formed in the 1980s when wealthy ranchers and farmers, including drug traffickers, hired armed groups to protect them from the kidnapping and extortion plots of the FARC and ELN. In the 1990s, most of the paramilitary groups formed an umbrella organization, the United-Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). The AUC massacred and assassinated suspected supporters of the insurgents and directly engaged the FARC and ELN in military battles. The Colombian military has long been accused of close collaboration with the AUC, accusations ranging from ignoring their activities to actively supporting them. Over time, the AUC became increasingly engaged in drug trafficking, and other illicit businesses. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the U.S. government designated the FARC, ELN, and AUC as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs).6 The AUC was formally dissolved in a collective demobilization between 2003 and 2006 after many of its leaders stepped down. However, former paramilitaries joined armed groups (called criminal bands, or Bacrim, by the Colombian government) who continued to participate in the lucrative drug trade and commit other crimes and human rights abuses. When the FARC demobilized in 2017, other illegally armed groups began aggressive efforts to take control of former FARC territory and its criminal enterprises as FARC forces withdrew. (For more, see "The Current Security Environment," below.)

|

Departments and Capitals shown |

|

The Uribe Administration (2002-2010)

The inability of Colombia's two dominant parties to address the root causes of violence in the country led to the election of an independent, Álvaro Uribe, in the presidential contest of 2002. Uribe, who served two terms, came to office with promises to take on the violent leftist guerrillas, address the paramilitary problem, and combat illegal drug trafficking.

During the 1990s, Colombia had become the region's—and the world's—largest producer of cocaine. Peace negotiations with the FARC under the prior administration of President Andrés Pastrana (1998-2002) had ended in failure; the FARC used a large demilitarized zone located in the central Meta department (see map, Figure 1) to regroup and strengthen itself. The central Colombian government granted the FARC this demilitarized zone, a traditional practice in Colombian peace negotiations, but the FARC used it to launch terror attacks, conduct operations, and increase the cultivation of coca and its processing, while failing to negotiate seriously. Many analysts, noting the FARC's strength throughout the country, feared that the Colombian state might fail and some Colombian citizens thought the FARC might at some point successfully take power.7 The FARC was then reportedly at the apogee of its strength, numbering an estimated 16,000 to 20,000 fighters under arms.

This turmoil opened the way for the aggressive strategy advocated by Uribe. At President Uribe's August 2002 inauguration, the FARC showered the event with mortar fire, signaling the group's displeasure at the election of a hardliner, who believed a military victory over the Marxist rebels was possible. In his first term (2002-2006), President Uribe sought to shore up and expand the country's military, seeking to reverse the armed forces' losses by aggressively combating the FARC. He entered into peace negotiations with the AUC.

President Pastrana had refused to negotiate with the rightist AUC, but Uribe promoted the process and urged the country to back a controversial Justice and Peace Law that went into effect in July 2005 and provided a framework for the AUC demobilization. By mid-2006, some 31,000 AUC paramilitary forces had demobilized. The AUC demobilization, combined with the stepped-up counternarcotics efforts of the Uribe administration and increased military victories against the FARC's irregular forces, helped to bring down violence, although a high level of human rights violations still plagued the country.8 Uribe became widely popular for the effectiveness of his security policies, a strategy he called "Democratic Security." Uribe's popular support was evident when Colombian voters approved a referendum to amend their constitution in 2005 to permit Uribe to run for a second term.

Following his reelection in 2006, President Uribe continued to aggressively combat the FARC. For Uribe, 2008 was a critical year. In March 2008, the Colombian military bombed the camp of FARC's second-in-command, Raul Reyes (located inside Ecuador a short distance from the border), killing him and 25 others. Also in March, another of FARC's ruling seven-member secretariat was murdered by his security guard. In May, the FARC announced that their supreme leader and founder, Manuel Marulanda, had died of a heart attack. The near-simultaneous deaths of three of the seven most important FARC leaders were a significant blow to the organization. In July 2008, the Colombian government dramatically rescued 15 long-time FARC hostages, including three U.S. defense contractors who had been held captive since 2003 and Colombian senator and former presidential candidate Ingrid Bentancourt. The widely acclaimed, bloodless rescue further undermined FARC morale.9

Uribe's success and reputation, however, were marred by several scandals. They included the "parapolitics" scandal in 2006 that exposed links between illegal paramilitaries and politicians, especially prominent members of the national legislature. Subsequent scandals that came to light during Uribe's tenure included the "false positive" murders allegedly carried out by the military (primarily the Colombian Army) in which innocent civilians were executed and then dressed to look like guerilla fighters to increase the military's rebel body count. In 2009, the media revealed another scandal of illegal wiretapping and other surveillance by the government intelligence agency, the Department of Administrative Security (DAS), to discredit journalists, members of the judiciary, and political opponents of the Uribe government. (In early 2012, the tarnished national intelligence agency was replaced by Uribe's successor, Juan Manuel Santos.) Despite the controversies, President Uribe remained popular and his supporters urged him to run for a third term in 2010. Another referendum was proposed to alter the constitution to allow a third term; however, it was turned down by Colombia's Constitutional Court.

The Santos Administration (2010-2018)

Once it became clear that President Uribe was constitutionally ineligible to run again, Juan Manuel Santos of the pro-Uribe National Unity party (or Party of the U) quickly consolidated his preeminence in the 2010 presidential campaign. Santos, a centrist, who came from an elite family that once owned the country's largest newspaper, had served as Uribe's defense minister through 2009. In 2010, Santos campaigned on a continuation of the Uribe government's approach to security and its role encouraging free markets and economic opening, calling his reform policy "Democratic Prosperity." In the May 2010 presidential race, Santos took almost twice as many votes as his nearest competitor, Antanas Mockus of the centrist Green Party, but he did not win a majority. Santos won the June runoff with 69% of the vote. Santos's "national unity" ruling coalition formed during his campaign included the center-right National Unity and Conservative parties, the centrist Radical Change Party, and the center-left Liberal party.10

On August 7, 2010, President Santos said in his first inauguration speech that he planned to follow in the path of President Uribe, but that "the door to [peace] talks [with armed rebels] is not locked."11 The Santos government was determined to improve relations with Ecuador and Venezuela, which had become strained under Uribe. Santos sought to increase cooperation on cross-border coordination and counternarcotics. He attempted to reduce tensions with Venezuela that had become fraught under Uribe, who claimed that Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez had long harbored FARC and ELN forces.

During his first two years in office, President Santos reorganized the executive branch and built on the market opening strategies of the Uribe administration and secured a free-trade agreement with the United States, Colombia's largest trade partner, which went into effect in May 2012. To address U.S. congressional concerns about labor relations in Colombia, including the issue of violence against labor union members, the United States and Colombia agreed to an "Action Plan Related to Labor Rights" (Labor Action Plan) in April 2011. Many of the steps prescribed by the plan were completed in 2011 while the U.S. Congress was considering the free trade agreement.

Significantly, the Santos government maintained a vigorous security strategy and struck hard at the FARC's top leadership. In September 2010, the Colombian military killed the FARC's top military commander, Victor Julio Suárez (known as "Mono Jojoy"), in a bombing raid. In November 2011, the FARC's supreme leader, Guillermo Leon Saenz (aka "Alfonso Cano") was assassinated. He was replaced by Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri (known as "Timoleón Jiménez" or "Timochenko"), the group's current leader.

While continuing the security strategy, the Santos administration began to re-orient the Colombian government's stance toward the internal armed conflict through a series of reforms. The first legislative reform that moved this new vision along, signed by President Santos in June 2011, was the Victims' and Land Restitution Law (Victims' Law), to provide comprehensive reparations to an estimated (at the time) 4 million to 5 million victims of the conflict. Reparations under the Victims' Law included monetary compensation, psycho-social support and other aid for victims, and the return of millions of hectares of stolen land to those displaced.12 The law was intended to process an estimated 360,000 land restitution cases.13 The government's implementation of this complex law began in early 2012.14 Between 2011 and 2016, there were more than 100,000 applications for restitution and 5,000 properties, or about 5%, were resolved by judges.15

The Victims' Law, while not a land reform measure, tackled issues of land distribution including the restitution of stolen property to displaced victims. Given the centrality of land issues to the rural peasant-based FARC, passage of the Victims' Law was a strong indicator that the Santos government shared its interest in addressing land and agrarian concerns. In June 2012, another government initiative—the Peace Framework Law, also known as the Legal Framework for Peace—was approved by the Colombian Congress, which signaled that congressional support for a peace process was growing.16

In August 2012, President Santos announced he had opened exploratory peace talks with the FARC and was ready to launch formal talks. The countries of Norway, Cuba, Venezuela, and Chile each held an international support role, with Norway and Cuba serving as peace talk hosts and "guarantors." Following the formal start in Norway, the actual negotiations began a month later in mid-November 2012 in Cuba, where the FARC-government talks continued until their conclusion in August 2016.

In the midst of extended peace negotiations, Colombia's 2014 national elections presented a unique juncture for the country. During the elections, the opposition Centro Democrático (CD) party gained 20 seats in the Senate and 19 in the less powerful Chamber of Representatives,17 and its leader, former President Uribe, became a popular senator. His presence in the Senate challenged the new ruling coalition that backed President Santos.

During his second-term inaugural address in August 2014, President Santos declared three pillars—peace, equality, and education—as his focus, yet his top priority was to conclude the peace negotiations with the FARC. In February 2015, the Obama Administration provided support to the peace talks by naming Bernard Aronson, a former U.S. assistant secretary of state for Inter-American Affairs, as the U.S. Special Envoy to the Colombian peace talks.

Talks with the FARC concluded in August 2016. In early October, to the surprise of many, approval of the accord was narrowly defeated in a national plebiscite by less than a half percentage point of the votes cast, indicating a polarized electorate. Regardless, President Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2016, in part demonstrating strong international support for the peace agreement. In response to the voters' criticisms, the Santos government and the FARC crafted a modified agreement, which they signed on November 24, 2016. Rather than presenting this agreement to a plebiscite, President Santos sent it directly to the Colombian Congress, where it was ratified on November 30, 2016. Although both chambers of Colombia's Congress approved the agreement unanimously, members of the opposition CD party criticized various provisions in the accord that they deemed inadequate and boycotted the vote.

The peace process was recognized as the most significant achievement of the Santos presidency and lauded outside of Colombia and throughout the region. Over the course of two terms, the President's approval ratings rose and fell rather significantly. His crowning achievement, the accord negotiated over 50 rounds of talks, covered five substantive topics: rural development and agricultural reform; political participation by the FARC; an end to the conflict, including demobilization, disarmament and reintegration; a solution to illegal drug trafficking; and justice for victims. A sixth topic provided for mechanisms to implement and monitor the peace agreement.

A New Legislature and President in 2018

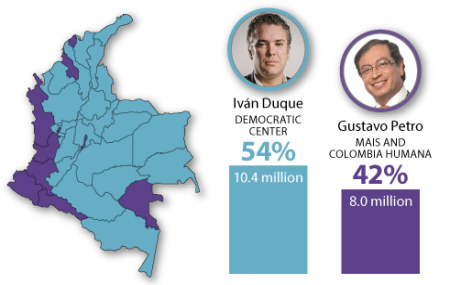

Colombians elected a new congress in March 2018 and a new president in June 2018. Because no presidential candidate won more than 50% of the vote on May 27, 2018, as required for a victory in the first round, a second-round runoff was held June 17 between the rightist candidate Iván Duque and the leftist candidate Gustavo Petro (see results for presidential contest, Figure 3). Duque was carried to victory with almost 54% of the vote. Runner-up Petro, a former mayor of Bogotá, a former Colombian Senator, and once a member of the M-19 guerilla insurgency, nevertheless did better than any leftist candidate in a presidential race in the past century; he won 8 million votes and nearly 42% of the votes cast. Around 4.2% were protest votes, signifying Colombian voters who cast blank ballots.

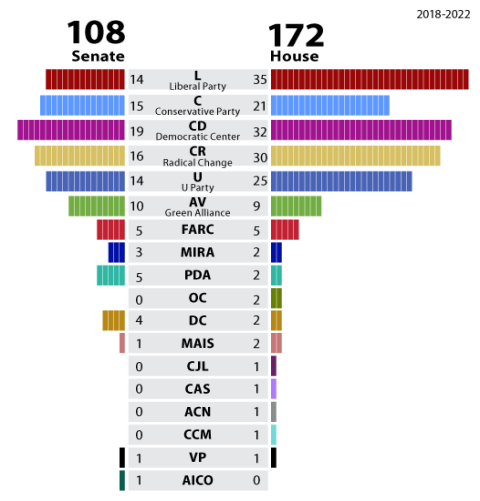

Through alliance building, Duque achieved a functional majority or a "unity" government, which involved the Conservative Party, Santos's prior National Unity or Party of the U, joining the CD, although compromise was required to keep the two centrist parties in sync with the more conservative CD. In the new Congress, two extra seats, for the presidential and vice presidential runners up, became automatic seats in the Colombian Senate and House, due to a constitutional change in 2015, allowing presidential runner up Gustavo Petro to return to the Senate. The CD party, which gained seats in both houses in the March vote, won the majority in the Colombian Senate (see Figure 2 for seat breakouts by party).

|

Figure 2. Legislative Election Results (March 11, 2018, results and the 12 automatic seats shown) |

|

|

Source: "Nueva Composición del Senado a Partir del 20 Julio," Senado de Colombia, March 14, 2018, at http://www.senado.gov.co/noticiero-del-senado/item/27756-nueva-composicion-del-senado-a-partir-del-20-julio; http://especiales.semana.com/big-data-electoral/distribucion-camara-representantes/index.html. Notes: FARC=Revolutionary Alternative Common Force; MIRA=Absolute Renovation Independent Movement; PDA=Alternative Democratic Pole; OC=Citizens' Option; DC=Decentes; MAIS=Alternative Indigenous and Social Movement; CJL=Colombia Justa Libres; CAS=Alternate Santander Coalition; ACN=Ancestral Afro-Colombian Communal Council of Playa Renaciente; CCM=La Mamuncia Communal Council; VP (Second Place Presidential in the Senate; Second Place Vice Presidential in House); AICO=Indigenous Authorities of Colombia. |

|

Figure 3. Presidential Second-Round Vote Results on June 17, 2018 |

|

|

Source: CRS. Notes: Drawn from data in http://www.eltiempo.com/elecciones-colombia-2018/presidenciales/mapa-de-resultados-de-la-segunda-vuelta-presidencial-en-colombia-232010. |

Duque, who was inaugurated on August 7, 2018, at the age of 42, was the youngest Colombian president elected in a century. He possessed limited experience in Colombian politics. Duque was partially educated in the United States and worked for at decade at the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington, DC. He was the handpicked candidate of former president Uribe, who vocally opposed many of Santos's policies. Disgruntled Colombians perceived Santos as an aloof president whose energy and political capital were expended accommodating an often-despised criminal group, the FARC. President Duque appeared to be technically oriented and interested in economic reform, presenting himself as a modernizer.

During his campaign, Duque called for economic renewal and lower taxes, fighting crime, and building renewed confidence in the country's institutions through some reforms. On September 26, 2018, in a speech before the U.N. General Assembly, the new president outlined his policy objectives.18 Duque called for increasing legality, entrepreneurship, and fairness by (1) promoting peace; (2) combating drug trafficking and recognizing it as a global menace, and (3) fighting corruption, which he characterized as a threat to democracy. He also maintained that the humanitarian crisis in neighboring Venezuela, resulting in more than 1 million migrants fleeing to Colombia, was an emergency that threatened to destabilize the region. Duque proposed a leadership role for Colombia in denouncing the authoritarian government of President Nicolás Maduro and containing his government's damage. By late November 2018, 1.2 million Venezuelans already present in Colombia were putting increasing pressure on the government's finances, generating a burden estimated at nearly 0.5% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP).19

President Duque, along with his vice president, Marta Lucía Ramírez, who initially ran as the Conservative Party candidate in the first round, recommended that drug policy shift back to a stricter counterdrug approach rather than a model endorsed in the peace accord, which focuses on voluntary eradication and economic support to peasant farmers to transition away from illicit drug crops. Duque campaigned on returning to spraying coca crops with the herbicide glyphosate. This would reverse Colombia's decision in mid-2015 to end aerial spraying, which had been a central—albeit controversial—feature of U.S.-Colombian counter-drug cooperation for two decades.20

Colombians' concerns with corruption became particularly acute during the 2018 elections, as major scandals were revealed. Similar to many countries in the region, government officials, including Santos during his 2014 campaign for reelection and the opposition candidate during that campaign were accused of taking payoffs (bribes) from the Odebrecht firm, the Brazilian construction company that became embroiled in a region-wide corruption scandal. In December 2018, presidential runner up Gustavo Petro was accused of taking political contributions from Odebrecht in a video released by a CD senator, indicating that both the left and the right of the Colombian political spectrum has been tainted by corruption allegations.21

In June 2017, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration arrested Colombia's top anti-corruption official, Gustavo Moreno. In mid-September 2017, the former chief justice of Colombia's Supreme Court was arrested for his alleged role in a corruption scandal that involved other justices accused of taking bribes from Colombian congressmen, some with ties to illegal paramilitary groups. The series of corruption charges made against members of Colombia's judicial branch, politicians, and other officials made the issue a prominent one in Colombian politics and was the focus of a left-centrist candidate's campaign in the presidential contest.

In late August 2018, an anti-corruption referendum was defeated by narrowly missing a high vote threshold by less than a half percentage point, although the actual vote favored all seven proposed changes on the ballot. President Duque endorsed the referendum and maintains he will seek to curb many of the abuses identified in the referendum through legislation that his administration will propose.

The Duque Administration's first budget for 2019 presented in late October 2018 was linked to an unpopular tax reform that would expand a value-added tax to cover basic food and agricultural commodities (some 36 items in the basic basket of goods, such as eggs and rice, previously exempted). The 2019 budget totals $89.7 billion, providing the education, military and police, and health sectors with the biggest increases, and reducing funding for peace accord implementation.22 Duque's own Democratic Center party split with him on the value-added tax, which quickly sank his approval ratings from 53% in early September 2018 to a low of 27% in November 2018,23 among the lowest levels in the early part of a presidential mandate in recent Colombian history.

Economic Background

Colombia's economy is the fourth largest in Latin America after Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina. The World Bank characterizes Colombia as an upper middle-income country, although its commodities-dependent economy has been hit by oil price declines and peso devaluation related to the erosion of fiscal revenue. Between 2010 and 2014, Colombia's economy grew at an average of more than 4%, but slowed to 3.1% GDP growth in 2015. In 2017, Colombia's GDP growth slowed further to 1.7%. Despite its relative economic stability, high poverty rates and inequality have contributed to social upheaval in Colombia for decades. The poverty rate in 2005 was slightly above 45%, but declined to below 27% in 2016. The issues of limited land ownership and high rural poverty rates remain a problem.24

According to a United Nations study published in 2011, 1.2% of the population owned 52% of the land,25 and data revealed in 2016 that about 49% of Colombians continued to work in the informal economy. Colombia is often described as a country bifurcated between metropolitan areas with a developed, middle-income economy, and some rural areas that are poor, conflict-ridden, and weakly governed. The fruits of the growing economy have not been shared equally with this ungoverned, largely rural periphery. Frequently these more remote areas are inhabited by ethnic minorities or other disadvantaged groups, such as Afro-Colombians, indigenous populations, or landless peasants and subsistence farmers, who are vulnerable to illicit economies due to few connections to the formal economy.

The United States is Colombia's leading trade partner. Colombia accounts for a small percentage of U.S. trade (approximately 1%), ranking 22nd among U.S. export markets and 27th among foreign exporters to the United States in 2017.26 Colombia has secured free trade agreements with the European Union, Canada, and the United States, and with most nations in Latin America. Colombian officials have worked over the past decade to increase the attractiveness of investing in Colombia, and foreign direct investment (FDI) grew by 16% between 2015 and 2016. This investment increase came not only from the extractive industries, such as petroleum and mining, but also from such areas as agricultural products, transportation, and financial services.

Promoting more equitable growth and ending the internal conflict were twin goals of the two-term Santos administration. Unemployment, which historically has been high at over 10%, fell below that double-digit mark during Santos's first term and remained at 9.2% in 2016 but rose slightly to an estimated 9.6% in 2018.27

Although Colombia is ranked highly for business-friendly practices and has a favorable regulatory environment that encourages trade across borders, it is still plagued by persistent corruption and an inability to effectively implement institutional reforms it has undertaken, particularly in regions where government presence is weak. According to the U.S. State Department in its analysis of national investment climates, Colombia has demonstrated a political commitment to create jobs, develop sound capital markets, and achieve a legal and regulatory system that meets international norms for transparency and consistency.

Despite its macroeconomic stability, several issues remain, such as a still-complicated tax system, a high corporate tax burden, and continuing piracy and counterfeiting issues. Colombia's rural-sector protestors formed strikes and blockades beginning in 2013 with demands for long-term and integrated-agricultural reform in a country with one of the most unequal patterns of land ownership.28 In October and November 2018, Colombian secondary and university students protested in high numbers during six large mobilizations, taking place over 60 days, to demand more funding for education.29

Peace Accord Implementation

The four-year peace talks between the FARC and the Santos administration started in Norway and moved to Cuba where negotiators worked through a six-point agenda during more than 50 rounds of talks that produced agreements on six major topics. The final topic—verification to enact the programs outlined in the final accord—all parties knew would be the most challenging, especially with a polarized public and many Colombians skeptical of whether the FARC would be held accountable for its violence and crimes during the years of conflict.30

Some analysts have estimated that to implement the programs required by the commitments in the accord to ensure stable post-conflict development may require 15 years and cost from $30 billion to $45 billion.31 The country faces steep challenges to underwrite the post-accord peace programs in an era of declining revenues. While progress has been uneven, some programs (those related to drug trafficking) had external pressure to move forward quickly and some considered urgent received "fast track" treatment to expedite their regulation by Congress. The revised peace accord that was approved by the Colombian Congress in late 2016 was granted fast track implementation by the Colombian Constitutional Court in a ruling on December 13, 2016, particularly applied to the FARC's disarmament and demobilization. However, in May 2017, a new ruling by the high court determined that all legislation related to the implementation of the accord needed to be fully debated rather than passed in an expedited fashion, which some analysts maintain started to slow the process of implementing the accord significantly.

The Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame is responsible for monitoring and implementing the agreement. It issued two interim reports in November 2017 and August 2018. At the end of the last reporting period (June 2018), the Kroc Institute estimated that 63% of the 578 peace accord commitments have begun implementation.32 In relation to other peace accords it had studied, the Kroc Institute found that the implementation of Colombia's accord was on course as about average, although that progress took place prior to President Duque's election.

The first provision undertaken was the demobilization of the FARC, monitored by a U.N. mission that was approved by the U.N. Security Council to verify implementation of the accords. U.N. monitors also emptied large arm caches identified by FARC leaders, seizing the contents of more than 750 of the reported nearly 1,000 caches by the middle of 2017. With the final disarmament, President Santos declared the conflict over in mid-August 2017. The U.S. State Department reported in its Country Reports on Terrorism 201, that by September 25, 2017, the United Nations had verified the collection of 8,994 arms, 1.7 million rounds, and more than 40 tons of explosives. The report states that the Colombian government had accredited "roughly 11,000 ex-combatants for transition to civilian life."33

The FARC also revealed its hidden assets in September 2017, listing more than $330 million in mostly real estate investments. This announcement drew criticism from several analysts who note that the FARC assets are likely much greater. In July 2017, the U.N. Security Council voted to expand its mandate and launch a second mission for three years to verify the reintegration of FARC guerrillas into civil society beginning September 20, 2017.34

One of Colombia's greatest challenges continues to be ensuring security for ex-combatants and demobilized FARC. The FARC's reintegration into civil society is a charged topic because the FARC's efforts in the 1980s to start a political party, known as the Patriotic Union, or the UP by its Spanish acronym, resulted in more than 3,000 party members being killed by rightwing paramilitaries and others.35 As of the end of 2018, reportedly 85 FARC members and their close relatives had been killed.36 In addition to unmet government guarantees of security, the FARC also has criticized the government for not adequately preparing for the group's demobilization. According to observers, the government failed to provide basic resources to FARC gathered throughout the country in specially designated zones for disarmament and demobilization (later renamed reintegration zones). The demobilization areas or cantonments had been so little prepared in early 2017 that the FARC had in many cases to construct their own housing and locate food and other provisions.

Reintegration of former combatants has proceeded slowly. The Constitutional Court's May 2017 ruling to restrict fast track, and controversy about the new court to try war crimes and other serious violations, the "Special Jurisdiction of Peace" led to further delays. Peace process advocates have cited limited attention to include ethnic Colombians, such as Afro-Colombian leaders and indigenous communities, into the accord's implementation, as required by the "ethnic chapter" of the peace accord. A U.N. deputy human rights official warned in October 2017 that after a successful demobilization it would be dangerous not to reintegrate FARC former combatants by providing them realistic options for income and delaying effective reintegration could undermine peace going forward.37

Under the peace accord, Territorially Focused Development Programs (PDETs in Spanish) are a tool for planning and managing a broad rural development process, with the aim of transforming170 municipalities (covering 16 subregions) most affected by the armed conflict. PDETs target those municipalities in Colombia with the highest number of displacements and those that have experienced the most killings, massacres, and forced disappearances. These marginal areas generally have experienced chronic poverty, high inequality, the presence of illicit crops such as coca, and low levels of local government institutional performance. Violence and forced displacements in some of the PDET municipalities increased in the last half of 2018.

Colombia's Constitutional Court determined in October 2017 that over the next three presidential terms (until 2030), Colombia must follow the peace accord commitments negotiated by the Santos administration and approved by the Colombian Congress in 2016.38 The Special Jurisdiction of Peace, set up to adjudicate the most heinous crimes of Colombia's decades-long armed conflict, began to hear cases in July 2018. However, Colombians remain skeptical of its capacity. A key challenge is the case of a FARC leader and lead negotiator in the peace process, Jesús Santrich, alleged to have committed drug trafficking crimes in 2017 after the accord was ratified, who has been jailed.39

The Current Security Environment

Colombia has confronted a complex security environment of armed groups: two violent leftist insurgencies, the FARC and the ELN, and groups that succeeded the AUC following its demobilization during the Uribe administration.

The FARC, whittled down by the government's military campaign against it, continued to conduct a campaign of terrorist activities during peace negotiations with the government through mid-2015, but it imposed successive temporary unilateral cease-fires that significantly reduced violence levels. In August 2016, the FARC and the government concluded negotiations on a peace accord that was subsequently approved by Congress with modifications in November 2016.40 Authorities and some analysts maintain that since the peace accord was ratified, 5% to 10% of the FARC have become dissidents who reject the peace settlement, although other estimates suggest a higher percentage. These armed individuals remain a threat.41

As agreed in the peace accord, the demobilized rebels transitioned to a political party that became known as the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force (retaining the acronym FARC) in September 2017.42 On November 1, 2017, the FARC announced their party's presidential ticket: current FARC leader Rodrigo Londoño (aka Timochenko) for president and Imelda Daza for vice president.43 The FARC Party ran several candidates in congressional races but failed to win any additional congressional race for which it competed in the March 2018 legislative elections, so the automatic seats in Congress were the only ones that it filled.

The ELN, like the FARC, became deeply involved in the drug trade and used extortion, kidnapping, and other criminal activities to fund itself.44The ELN, with diminished resources and reduced offensive capability, according to government estimates, declined to fewer than 2,000 fighters, although some analysts maintain in 2018 the forces grew as high as 3,400, including former FARC who were recruited to join the ELN as the larger rebel group demobilized. In 2015, ELN leadership began exploratory peace talks with the Santos government in Ecuador, although the ELN continued to attack oil and transportation infrastructures and conduct kidnappings and extortions, at least periodically. Formal talks with the ELN finally opened in February 2017 in Quito, Ecuador. After the talks moved to Cuba in May 2018, at the request of Ecuador's President Lenín Moreno, several negotiating sessions took place. The ELN's central leadership, including Nicolás Rodríguez Bautista (aka "Gabino"), arrived in Cuba to continue the talks. However, President Duque in September 2018 suspended the talks and recalled the government negotiating team. The ELN is far more regionally oriented, decentralized, and nonhierarchical in its decisionmaking than the FARC. Late in 2018, a Colombian political online magazine claimed a meeting had been held two months earlier between FARC dissident groups and the ELN in Venezuela in which the parties discussed how to increase their coordination.45

On January 17, 2019, a car bomb attack at a National Police academy in southern Bogotá shattered illusions that Colombia's long internal conflict with insurgents was coming to an end. The bombing, allegedly carried out by an experienced ELN bomb maker, killed 20 police cadets and the bomber and injured more than 65 others. The ELN took responsibility for the attack in a statement published on January 21. Large demonstrations took place in Bogotá protesting the return of violence to Colombia's capital city. The Duque government ended peace talks with the ELN, which had been ongoing sporadically since 2017.46 The Duque government then requested extradition of the ELN's delegation of negotiators to the peace talks in Cuba on terrorism charges. The Cuban government, which condemned the bombing, responded that the protocols for the peace talks required that the negotiators be returned to Colombia without arrest. The Duque government has persisted in requesting the negotiators to be extradited.47

The AUC, the loosely affiliated national umbrella organization of paramilitaries, officially disbanded a decade ago. The organization was removed from the State Department's Foreign Terrorist Organizations list in July 2014. More than 31,000 AUC members demobilized between 2003 and 2006, and many AUC leaders stepped down. However, as noted, many former AUC paramilitaries continued their illicit activities or re-armed and joined criminal groups—known as Bacrim. Many observers view the Bacrim as successors to the paramilitaries,48 and the Colombian government has characterized these groups as the biggest threat to Colombia's security since 2011. The Bacrim do not appear to be motivated by the dream of defeating the national government, but they seek territorial control and appear to provide rudimentary justice in ungoverned parts of the country.49

In 2013, the criminal group Los Urabeños, launched in 2006, emerged as the dominant Bacrim. Over its lifetime, the group has been referred to as the Gaitanistas, the Clan Úsuga, and most recently El Clan del Golfo, growing to about 3,000 members by 2015.50 The Urabeños organization is heavily involved in cocaine trafficking as well as arms trafficking, money laundering, extortion, gold mining, human trafficking, and prostitution.51 Early leaders of the group, such as founder Daniel Rendón Herrera (alias "Don Mario") and his brother Feddy Rendón Herrera were designated drug kingpins under the U.S. Kingpin Act in 2009 and 2010, respectively. However, because these men had been part of the AUC peace process, they could not be extradited to the United States until they had served time and paid reparations.

In June 2015, the Justice Department unsealed indictments against 17 alleged Urabeños members.52 The Colombian government's efforts to dismantle the Urabeños and interrupt its operations began to result in the capture of top leaders and gradually to disrupt its illicit activities.53 The Urabeños faced an intense enforcement campaign by the Colombian police and military, especially after the Urabeños reportedly advertised and paid rewards to its subcontracted assassins to murder Colombian police.54 In September 2017, the Urabeños top leader, Dairo Antonio Úsuga (alias "Otoniel"), requested terms of surrender from the Santos government after the arrest of his wife and the killing or arrest of siblings and co-leaders, but this offer was never formalized. Colombia captured a vast amount of cocaine, approximately 12 metric tons, linked to the the Urabeños in November 2017.55

Splinter groups of the large Colombian drug cartels of the 1980s and 1990s, such as the Medellin Cartel and Cali Cartel, have come and gone in Colombia, including the powerful transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) the Norte del Valle Cartel and Los Rastrajos. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration's 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment maintains "large-scale Colombian TCOs" work closely with Mexican and Central American TCOs to export large quantities of cocaine out of Colombia every year.56 Traditionally, the FARC and ELN had cooperated with Bacrim and other Colombian crime groups in defense of drug trafficking and other illicit activities despite the groups' ideological differences.

Venezuela is a major transit corridor for Colombian cocaine.57 According to the State Department's 2018 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, Venezuela's porous western border with Colombia, current economic crisis, weak judicial system, sporadic international drug control cooperation, and a permissive and corrupt environment make it a preferred trafficking route for illicit drugs. A May 2018 report by Insight Crime identified more than 120 high-level Venezuelan officials who have engaged in criminal activity.58 The report analyzes how the Venezuelan military, particularly the National Guard, has been involved in the drug trade since 2002 and colluded with other illegally armed groups.

Another Bacrim, Los Rastrojos, reportedly controls important gasoline smuggling routes between Venezuela and Colombia in 2018. Similarly, in the past year, ELN guerrillas reportedly have moved from seeking safe haven in Venezuela to taking control of illicit gold mining areas near Venezuela's border with Guyana.59 Both the ELN, which is still engaged in armed conflict with the Colombian government, and its rival, the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), reportedly recruit Venezuelans to cultivate coca in Colombia. Human trafficking and sexual exploitation of Venezuelan migrants throughout Colombia is prevalent. Dissident FARC guerrillas are using border areas and other remote areas in the countryside to regroup and could eventually seek to consolidate into a more unified organization or coordinate with other criminal groups sheltering in Venezuela.60

The State Department's 2017 terrorism report published in April 2018 maintained that the number of terrorist incidents in Colombia—carried out by the FARC and ELN—decreased significantly, by 40%, over the already much-diminished level of 2016. ELN aggression included high-impact attacks, such as launching mortars at police stations and bombing pipelines, although the report also states that ELN demobilizations and surrenders have increased.

Instability in Venezuela Drives a Regional Migrant Crisis61

The humanitarian crisis in Venezuela has set in motion a mass exodus of desperate migrants, who have come temporarily (or for extended stays) to Colombia. Although Venezuela has experienced hyperinflation (the highest in the world), a rapid contraction of its economy, and severe shortages of food and medicine, as of November 2018 Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has refused most international humanitarian assistance. Based on estimates from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as of November 2018, more than 3 million Venezuelans were living outside Venezuela; of these, an estimated 2.3 million left after 2015. As conditions in Venezuela have continued to deteriorate, increasing numbers of Venezuelans have left the country. Neighboring countries, particularly Colombia, are straining to absorb a migrant population that is often malnourished and in poor health. The spread of previously eradicated diseases, such as measles, is also a major regional concern.

|

Colombia's Response to Venezuelan Migrants Colombia has received the majority of Venezuelan migrants amid its own political transition and other pressures. Officially, there are about 1 million Venezuelans throughout the country, but the actual figure is unknown. According to Colombian officials, this is no longer only a border crisis; 60% of Venezuelans now live in other parts of the country. The government's response to the mixed migration flows is focused on four groups

The Colombian government estimates that the costs of providing emergency health care, education, vaccinations and other services could exceed 0.5% of the country's GDP. Colombia has asked for more international aid, better donor coordination, and equal burden sharing among countries. The ongoing violence and criminality in parts of Colombia has added to the complexity of the humanitarian response, particularly in areas where these situations overlap. Aid agencies are especially concerned about conditions in Colombia's eastern and southern border regions (near Ecuador), where armed groups are active, and the northwestern Catatumbo region near Venezuela, where migrants reportedly are being forced into smuggling and coca cultivation. The government continues to weigh options for how best to provide shelter to Venezuelan arrivals while managing the impact on local Colombian communities. |

In January 2019, the Trump Administration announced backing for the president of the Venezuelan National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, as interim president of Venezuela. The Trump Administration has called for Maduro's departure, and Colombia joined many other countries in Latin America and Europe to recognize Guaidó. U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo announced that the United States was prepared to provide $20 million in humanitarian assistance to the people of Venezuela.62 Colombia joined 11 countries in the Lima Group that declared on February 4, 2019, their desire to hasten a return to democracy in Venezuela by working with Guaidó for a peaceful transition without the use of force.

Ongoing Human Rights Concerns

Colombia's multisided internal conflict over the last half century generated a lengthy record of human rights abuses. Although it is widely recognized that Colombia's efforts to reduce violence, combat drug trafficking and terrorism, and strengthen the economy have met with success, many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and human rights groups continue to report significant human rights violations, including violence targeting noncombatants, that involves killings, torture, kidnappings, disappearances, forced displacements, forced recruitments, massacres, and sexual attacks.

The Center for Historical Memory report issued to the Colombian government in July 2013 traces those responsible for human rights violations to the guerrillas (the FARC and ELN), the AUC paramilitaries and successor paramilitary groups, and the Colombian security forces. In analyzing nearly 2,000 massacres between 1980 and 2012 documented in the center's database, the report maintains that 58.9% were committed by paramilitaries, 17.3% by guerrillas, and 7.9% by public security forces.63 According to the U.S. State Department's annual report on human rights covering 2017, Colombia's most serious human rights abuses centered on extrajudicial and unlawful killings; torture and detentions; rape and sexual crimes. In addition to the State Department, numerous sources report regularly on human rights conditions in Colombia. (See Appendix.)

Colombia continues to experience murders and threats of violence against journalists, human rights defenders, labor union members, social activists such as land rights leaders, and others. Crimes of violence against women, children, Afro-Colombian and indigenous leaders, and other vulnerable groups continue at high rates. In December 2018, the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights defenders came out with strong criticism of heightened murders of human rights defenders, which he maintained were committed by hitmen paid no more than $100 per murder, according to reports he heard from activists and other community members whom he met with during a trip to Colombia.64 These ongoing issues reflect constraints of the Colombian judicial system to effectively prosecute crimes and overcome impunity.

Extrajudicial Executions and "False Positives"

For many years, human rights organizations have raised concerns about extrajudicial executions committed by Colombian security forces, particularly the military. In 2008, it was revealed that several young men from the impoverished community of Soacha—who had been lured allegedly by military personnel from their homes to another part of the country with the promise of employment—had been executed. When discovered, the Soacha murder victims had been disguised as guerrilla fighters to inflate military claims of enemy body counts, resulting in the term false positives. Following an investigation into the Soacha murders, the military quickly fired 27 soldiers and officers, including three generals, and the army's commander resigned. The Colombian prosecutor general's criminal investigations of soldiers and officers who allegedly participated in the Soacha executions have proceeded quite slowly. Some 48 of the military members eventually charged with involvement in the Soacha cases were released due to the expiration of the statute of limitations. Whereas some soldiers have received long sentences, few sergeants or colonels have been successfully prosecuted.65

In 2009, the false positive phenomenon was investigated by the U.N.'s Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions, who issued a report that concluded with no finding that such killings were a result of an official government policy. However, the Special Rapporteur did find, "the sheer number of cases, their geographic spread, and the diversity of military units implicated, indicate that these killings were carried out in a more or less systematic fashion by significant elements within the military."66 The majority of the cases took place between 2004 and 2008, when U.S. assistance to Colombia peaked. In recent years, the number of new alleged false positive cases declined steeply, but human rights NGOs still reported a few cases in 2012

through 2015.

To address the military's human rights violations, the Santos administration proposed a change to policy that did not prevail. This reform was a constitutional change to expand the jurisdiction of military courts and, it was approved by the Colombian Congress in late December 2012 by a wide margin despite controversy.67 Human rights groups criticized the legislation's shift in the jurisdiction over serious human rights crimes allegedly committed by Colombia's public security forces from the civilian to the military justice system.68 In its review of the constitutional amendment, the Colombian Constitutional Court struck down the law over procedural issues in October 2013.69

Human Rights Watch in a 2015 report on the false positive cases noted that prosecutors in the Human Rights Unit of the Prosecutor General's Office conducted investigations into more than 3,000 false positive homicide cases allegedly committed by army personnel that resulted in about 800 convictions, mostly of lower-ranking soldiers.70 Only a few of those convictions involved former commanders of battalions or other tactical units, and none of the investigations of 16 active and retired army generals had produced charges. In 2016, the prosecutions against generals accused of responsibility for false positives continued, although a few were closed and 12 remained under investigation at year's end. Additionally, in October 2016, the Colombian prosecutor general indicted Santiago Uribe, the brother of former President Uribe, on charges of murder and association to commit crimes for his alleged role in the paramilitary group "The 12 Apostols" in the 1990s.71 The State Department human rights report covering 2017, maintains that during the year through July, four new cases involving "aggravated homicide" committed by security forces and 11 new convictions were reached for "simple homicide" by security force members.72

Human Rights Defenders and Journalists

Although estimates diverge, the number of human rights defenders murdered in 2016 totaled 80 and another 51 in the first half of 2017, according to Somos Defensores ("We are Defenders"), a Colombian NGO that tracks violence against defenders and is cited by the State Department.73 Some groups, such as the Colombian think tank, Indepaz, say the numbers are higher, up to 117 murders in 2016.74 In the two years since the approval of the 2016 peace accord, social leaders, ethnic community leaders, and human rights defenders have suffered from continued high levels of violence. Human rights organizations cite the murders of more than 100 activists in 2017 and in 2018. Of the 109 human rights and civil society activists killed in 2018 through November, some were leaders of efforts to implement the 2016 peace accord.75 For instance, 13 social leaders were assassinated in the southwest department of Cauca in the first six months of the year, a department in Colombia with the fourth largest area devoted to coca cultivation in the country and host to several peace accord programs associated with rural development, including voluntary eradication of drug crops. Few, if any, of those accused of making threats and ordering or carrying out assassinations have been prosecuted. According to these activists, perpetrators still have little to fear of legal consequences.

Since early 2012, violence against land rights activists has risen sharply with the start of implementation of the Victims' Law that authorized the return of stolen land. A September 2013 report by Human Rights Watch pointing to the rise in violence against land activists and claimants maintained that the environment had turned so threatening that claimants who had received land judgments were too frightened to return, and the government had received more than 500 serious threats against claimants in less than 18 months. According to Human Rights Watch, many of the threats and killings have been conducted by paramilitary-influenced Bacrim, although they may be operating at the behest of third-party "landowners," who are trying to protect their land from seizure.

For more than a decade, the Colombian government tried to suppress violence against groups facing extraordinary risk through the National Protection Unit (UPN) programs. Colombia's UPN provides protection measures, such as body guards and protective gear, to individuals in at-risk groups, including human rights defenders, journalists, trade unionists, and others. However, according to international and Colombian human rights groups, the UPN has been plagued by corruption issues and has inadequately supported the prosecution of those responsible for attacks. According to the State Department's Report on Human Rights Practices covering 2017, the UPN protected roughly 6,067 at-risk individuals, including 575 human rights activists, with a budget of $150 million.76 Journalists, a group that has traditionally received protection measures from the UPN, continue to operate in a dangerous environment in Colombia. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), 47 journalists have been killed in work-related circumstances since 1992. Three Ecuadorian journalists were killed by a FARC dissident group close to the border of Ecuador in 2018, leading to the end of the Colombian government's peace talks with the ELN in Ecuador and their subsequent move to Cuba.

To help monitor and verify that human rights were respected throughout implementation of the peace accord, the government formally renewed the mandate of the U.N.'s High Commissioner of Human Rights in 2016 for three years.

Violence and Labor

The issue of violence against the labor movement in Colombia has sparked controversy and debate for years. Many human rights groups and labor advocates have maintained that Colombia's poor record on protecting its trade union members and leaders from violence is one reason to avoid closer trade relations with Colombia. The U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (also known as the U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement) could not be enacted without addressing the deep concern of many Members of Congress that Colombia must enforce basic labor standards and especially measures to mitigate the alleged violence against trade union members and bring perpetrators of such violence to justice.

In April 2011, the United States and Colombia agreed to an "Action Plan Related to Labor Rights" (the Labor Action Plan, LAP), which contained 37 measures that Colombia would implement to address violence, impunity, and workers' rights protection. Before the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement entered into force in April 2012, the U.S. Trade Representative determined that Colombia had met all the important milestones in the LAP to date.77

Despite the programs launched and measures taken to implement the LAP, human rights and labor organizations claim that violence targeting labor union members continues. (Some analysts continue to debate whether labor activists are being targeted because of their union activities or for other reasons.) The Colombian government has acknowledged that violence and threats continue, but points to success in reducing violence generally and the number of homicides of labor unionists specifically. Violence levels in general are high in Colombia, but have steadily been decreasing. According to the data reported by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in its annual homicide report, rates have decreased dramatically since 2002, when the homicide rate was at 68.9 per 100,000.78 The Colombian Ministry of Defense reported in 2016 that the homicide rate had declined to 24.4 per 100,000.79

In this context of an overall steady decline in homicides, the number of labor union killings has also declined. For many years, the government and the leading NGO source that tabulates these crimes did not agree on the number of labor union murders because they used different methodologies. Both sources recorded a decline, but the government generally saw a steeper decline. According to the Colombian labor rights NGO and think tank, the National Labor School (Escuela Nacional Sindical, ENS), there has been a significant decline from 191 labor union murders in 2001 to 20 reported in 2012.80 In 2017, through the month of August the ENS reported 14 labor murders.81 Of the cases covering homicides between January 2011 and August 2017, 162 homicide cases in which victims were labor union members, were 409 convictions, 31 for cases after 2011 and 378 for cases before 2011.82

In addition, labor advocates note that tracking homicides does not capture the climate of intimidation that Colombian labor unions face. In addition to lethal attacks, trade union members encounter increased death threats, arbitrary detention, and other types of harassment. Measures to strengthen the judicial system to combat impunity for such crimes are also part of the Labor Action Plan. Nevertheless, many analysts maintain there remains a large backlog of cases yet to be investigated involving violent crimes against union members.

Internal Displacement

The internal conflict has been the major cause of a massive displacement of the civilian population that has many societal consequences, including implications for Colombia's poverty levels and stability. Colombia has one of the largest populations of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the world. Most estimates place the total at more than 7 million IDPs, or more than 10% of Colombia's estimated population of 49 million.83 This number of Colombians, forcibly displaced and impoverished as a result of the armed conflict, continues to grow and has been described by many observers as a humanitarian crisis. Indigenous and Afro-Colombian people make up an estimated 15%-22% of the Colombian population.84 They are, however, disproportionately represented among those displaced. The leading Colombian NGO that monitors displacement, Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES), reports that 36% of the victims of forced displacement nationwide in 2012 came from the country's Pacific region where Afro-Colombian and indigenous people predominate.85

The Pacific region has marginal economic development as a result of weak central government presence and societal discrimination. (Some 84% of the land in the Pacific region is subject to collective-title rights granted to Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities.86) Illegal armed groups are active in usurping land in this region, which is valued for its proximity to a major port and drug trafficking routes, and the Afro- and indigenous communities are also caught in the middle of skirmishes between illegal groups and Colombian security forces.

IDPs suffer stigma and poverty and are often subject to abuse and exploitation. In addition to the disproportionate representation of Colombia's ethnic communities among the displaced, other vulnerable populations, including women and children, have been disproportionally affected. Women, who make up more than half of the displaced population in Colombia, can become targets for sexual harassment, violence, and human trafficking. Displacement is driven by a number of factors, most frequently in more remote regions of the country where armed groups compete and seek to control territory or where they confront Colombian security forces. Violence that uproots people includes threatened or actual child recruitment or other forced recruitment by illegal armed groups, as well as physical, psychological, and sexual violence. Other contributing factors reported by NGOs include counternarcotics measures such as aerial spraying, illegal mining, and large-scale economic projects in rural areas. Inter-urban displacement is a growing phenomenon in cities such as Buenaventura and Medellin, which often results from violence and threats by organized crime groups.

The Victims' Law of 2011, which began to be implemented in 2012, is the major piece of legislation to redress Colombian displacement victims with the return of their stolen land. The historic law provides restitution of land to those IDPs who were displaced since January 1, 1991. The law aims to return land to as many as 360,000 families (impacting up to 1.5 million people) who had their land stolen. The government notes that some 50% of the land to be restituted has the presence of land mines and that the presence of illegally armed groups in areas where victims have presented their applications for land restitution has slowed implementation of the law.

Between 2011 and 2016, 100,000 applications for land restitution were filed and approximately 5,000 properties (roughly 5% of applications) were successfully returned following judgements on the cases. With the international support from U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and other donors, a Victims Unit was established to coordinate the range of services for victims, including financial compensation and psychosocial services, provided by a host of government agencies. The 2011 Victims' Law is considered a model and particularly the implementation of a Victims' registry, which was supported by USAID. Through its Victims Unit, the Colombian government had provided financial reparations to over 800,000 victims and psychosocial support to 700,000 as of October 2018.

The Global Report on Internal Displacement from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) reported, however, displacement inside Colombia continued with more than 171,000 internally displaced in 2016.

As the political crisis in Venezuela has grown, a wave of refugees and migrants have come across the border into Colombia reversing an earlier trend. Venezuelans were fleeing political instability and economic turmoil in Colombia's once-wealthy neighboring nation.87 Venezuela's economic crisis worsened throughout 2018, prompting a sharp increase in migrants seeking to escape into Colombia.88 In response to the growing flood of Venezuelans, former President Santos initially announced that he would impose stricter migratory controls and deploy thousands of new security personnel along the frontier. Nevertheless, he acknowledged that Venezuela had once served as a vital escape valve for Colombian refugees fleeing their half century internal conflict, for which he was grateful.89

Regional Relations

Colombia shares long borders with neighboring countries, and some of these border areas have been described as porous to illegal armed groups that threaten regional security. Colombia has a 1,370-mile border with Venezuela, approximately 1,000-mile borders with both Peru and Brazil, and shorter borders with Ecuador and Panama. Much of the territory is remote and rugged and suffers from inconsistent state presence. Although all of Colombia's borders have been problematic and subject to spillover effects from Colombia's armed conflict, the most affected are Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama.

Over the years, Colombia's relations with Venezuela and Ecuador have been strained by Colombia's counterinsurgency operations, including cross-border military activity. The FARC and ELN insurgents have been present in shared-border regions and in some cases the insurgent groups used the neighboring countries to rest, resupply, and shelter.

Former President Uribe accused the former Venezuelan government of Hugo Chávez of harboring the FARC and ELN and maintained that he had evidence of FARC financing the 2006 political campaign of Ecuador's leftist President Rafael Correa. Relations between Ecuador and Colombia remained tense following the Colombian military bombardment of a FARC camp inside Ecuador in March 2008. Ecuador severed diplomatic relations with Colombia for 33 months. Also in 2008, Ecuador filed a suit against Colombia in the International Court of Justice (ICJ), claiming damages to Ecuadorian residents affected by spray drift from Colombia's aerial eradication of drug crops. In September 2013, Colombia reached an out-of-court settlement awarding Ecuador $15 million.

Once in office, President Santos reestablished diplomatic ties with both countries and in his first term (2010-2014) cooperation greatly increased between Colombia and Venezuela on border and security issues and with Ecuador's Correa. However, concerns about Venezuelan links to the FARC and the continued use of Venezuela by the FARC and ELN as a safe haven to make incursions into Colombia remained an irritant in Colombian-Venezuelan relations. Nevertheless, the Venezuelan and Colombian governments committed to jointly combat narcotics trafficking and illegal armed group activities along the porous Venezuelan-Colombian border and Venezuela remained a supporting government of the FARC-government peace talks (along with Chile, Norway, and Cuba) through 2016, even after former President Chávez died in office in March 2013. Ecuador's government hosted exploratory talks between the ELN and the Santos government beginning in 2015, which became formal talks hosted in Quito in February 2017, although Ecuador's president requested that the talks move to Cuba in May 2018, due to a spate of border violence that could have been related to the ELN.

For many years, the region in Panama that borders Colombia, the Darien, was host to a permanent presence of FARC soldiers who used the remote area for rest and resupply as well to transit drugs north. By 2015, according to the State Department, the FARC was no longer maintaining a permanent militarized presence in Panamanian territory, in part due to effective approaches taken by Panama's National Border Service in coordination with Colombia. Nevertheless, the remote Darien region still faces challenges from smaller drug trafficking organizations and criminal groups such as Bacrim and experiences problems with human smuggling with counterterrorism implications.90

Colombia's Role in Training Security Personnel Abroad

When Colombia hosted the Sixth Summit of the Americas in April 2012, President Obama and President Santos announced a new joint endeavor, the Action Plan on Regional Security Cooperation. This joint effort, built on ongoing security cooperation, addresses hemispheric challenges, such as combating transnational organized crime, bolstering counternarcotics, strengthening institutions, and fostering resilient communities.91 The Action Plan focuses on capacity building for security personnel in Central America and the Caribbean by Colombian security forces (both Colombian military and police). To implement the plan, Colombia undertook several hundred activities in cooperation with Panama, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and the Dominican Republic, and between 2013 and 2017 trained almost 17,000 individuals (see Figure 4).92 The Colombian government notes that this program grew dramatically from 34 executed activities in 2013 to 441 activities planned for 2018.93

Colombia has increasingly trained military and police from other countries both under this partnership and other arrangements, including countries across the globe. According to the Colombian Ministry of Defense, around 80% of those trained were from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. U.S. and Colombian officials maintain that the broader effort is designed to export Colombian expertise in combating crime and terrorism while promoting the rule of law and greater bilateral and multilateral law enforcement cooperation.

Critics of the effort to "export Colombian security successes" maintain that human rights concerns have not been adequately addressed.94 Some observers question the portion of these activities that are funded by the U.S. government and want to see more transparency.95 In one analysis of the training, a majority of the training was provided by Colombian National Police rather than the Colombian Army, in such areas as ground, air, maritime, and river interdiction; police testimony; explosives; intelligence operations; psychological operations; and Comando JUNGLA, Colombia's elite counternarcotics police program.96

Other analysts praise the Colombian training and maintain that U.S. assistance provided in this way has helped to improve, professionalize, and expand the Colombian military, making it the region's second largest. As that highly trained military shifts from combating the insurgency and the Colombian National Police take the dominant role in guaranteeing domestic security, Colombia may play a greater role in regional security and even in coalition efforts internationally.97 In September 2017, President Trump announced that he had considered designating Colombia in noncompliance with U.S. counternarcotics requirements, but noted that he had not proceeded with the step in part because of Colombian training efforts to assist others in the region with combating narcotics and related crime.98

U.S. Relations and Policy

Colombia is a key U.S. ally in the region. With diplomatic relations that began in the 19th century following Colombia's independence from Spain, the countries have enjoyed close and strong ties. Because of Colombia's prominence in the production of illegal drugs, the United States and Colombia forged a close partnership over the past 16 years. Focused initially on counternarcotics, and later counterterrorism, a program called Plan Colombia laid the foundation for a strategic partnership that has broadened to include sustainable development, human rights, trade, regional security, and many other areas of cooperation. Between FY2000 and FY2016, the U.S. Congress appropriated more than $10 billion in assistance from U.S. State Department and Department of Defense (DOD) accounts to carry out Plan Colombia and its follow-on strategies. During this time, Colombia made notable progress combating drug trafficking and terrorist activities and reestablishing government control over much of its territory. Its economic and social policies have reduced the poverty rate and its security policies have lowered the homicide rate.

Counternarcotics policy has been the defining issue in U.S.-Colombian relations since the 1980s because of Colombia's preeminence as a source country for illicit drugs. Peru and Bolivia were the main global producers of cocaine in the 1980s and early 1990s. However, successful efforts there in reducing supply pushed cocaine production from those countries to Colombia, which soon surpassed both its Andean neighbors. The FARC and other armed groups in the country financed themselves primarily through narcotics trafficking, and that lucrative illicit trade provided the gasoline for the decades-long internal armed conflict at least since the 1990s.99 Colombia emerged to dominate the cocaine trade by the late 1990s. National concern about the crack cocaine epidemic and extensive drug use in the United States led to greater concern with Colombia as a source. As Colombia became the largest producer of coca leaf and the largest exporter of finished cocaine, heroin produced from Colombian-grown poppies was supplying a growing proportion of the U.S. market.100 Alarm over the volumes of heroin and cocaine being exported to the United States was a driving force behind U.S. support for Plan Colombia at its inception.

The evolution of Plan Colombia took place under changing leadership and changing conditions in both the United States and Colombia. Plan Colombia was followed by successor strategies such as the National Consolidation Plan, described below, and U.S.-Colombia policy has reached a new phase anticipating post-conflict Colombia.

Plan Colombia and Its Follow-On Strategies

Announced in 1999, Plan Colombia originally was a six-year strategy to end the country's decades-long armed conflict, eliminate drug trafficking, and promote development. The counternarcotics and security strategy was developed by the government of President Andrés Pastrana in consultation with U.S. officials.101 Colombia and its allies in the United States realized that for the nation to gain control of drug trafficking required a stronger security presence, the rebuilding of institutions, and extending state presence where it was weak or nonexistent.