Introduction

Review of regulations issued under the Obama Administration, with the possibility of their modification or repeal, was the main focus of interest on Clean Air Act issues in the 115th Congress and in the executive and judicial branches in 2017 and 2018. This will likely continue in the 116th Congress—although with a different emphasis, given the new majority in the House. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules to regulate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from power plants, cars and trucks, and the oil and gas sector have been of particular interest.

EPA's Greenhouse Gas Regulations

A continuing focus of congressional interest under the Clean Air Act (CAA)1 has been EPA regulatory actions to limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions using existing CAA authority. Since 2007, the Supreme Court has ruled on two separate occasions that the Clean Air Act authorizes the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to set standards for emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs). In the first case, Massachusetts v. EPA,2 the Court held that GHGs are air pollutants within the Clean Air Act's definition of that term and that EPA must regulate their emissions from motor vehicles if the agency found that such emissions cause or contribute to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare. In the second case, American Electric Power, Inc. v. Connecticut,3 the Court held that corporations cannot be sued for GHG emissions under federal common law, because the Clean Air Act delegates the management of carbon dioxide and other GHG emissions to EPA: "... Congress delegated to EPA the decision whether and how to regulate carbon-dioxide emissions from power plants; the delegation is what displaces federal common law."4

EPA actions have focused on six gases or groups of gases that multiple scientific studies have linked to climate change. Of the six gases, carbon dioxide (CO2), which is produced by combustion of fossil fuels and is the most prevalent, accounts for about 80% of annual emissions of the combined group when measured as CO2 equivalents.5

Of the GHG emission standards promulgated by EPA, four sets of standards, which have had the broadest impacts, are discussed below: those for power plants, the oil and gas industry, trucks, and light-duty vehicles (the latter two topics are combined under the heading "Standards for Motor Vehicles"). EPA finalized GHG standards for power plants in August 2015; set GHG emission standards for oil and gas industry sources in June 2016; finalized a second round of GHG standards for trucks in August 2016; and completed a Mid-Term Evaluation (MTE) of the already promulgated GHG standards for model years 2022-2025 light-duty vehicles (cars and light trucks) in January 2017. Most of these rules are under review at EPA; the agency has proposed repeal or modification in several cases.

Standards for Power Plants (Clean Power Plan and NSPS)

The electricity sector has historically accounted for the largest percentage of anthropogenic U.S. CO2 emissions, though transportation activities have more recently accounted for a slightly larger share. In 2016, the electricity sector accounted for 28.4% of total U.S. GHG emissions and transportation activities accounted for 28.5%.6 EPA finalized GHG (CO2) emission standards under CAA Section 111 for new, existing, and modified fossil-fueled power plants in August 2015.7 The standards would primarily affect coal-fired units, which emit twice the amount of CO2 that would be emitted by an equivalent natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) electric generating unit.8 The final rules were controversial: EPA received more than 4 million public comments as it considered the proposed standards for existing units, by far the most comments on a rulemaking in the agency's 48-year history.

The Clean Power Plan (CPP), which is the rule for existing units, would set state-specific goals for CO2 emissions or emission rates from existing fossil-fueled power plants. EPA established different goals for each state based on three "building blocks": improved efficiency at coal-fired power plants; substitution of NGCC generation for coal-fired power; and zero-emission power generation from increased renewable energy, such as wind or solar. The goals would be phased in, beginning in 2022, with final average emission rates for each state to be reached by 2030.

Independently of the CPP, the period since its proposal in 2014 has seen rapid changes in the electric power industry. Coal-fired power plants have been retired in record numbers and cleaner sources of electric power (both renewable and natural-gas-fired) have taken their place.9 Coal, which accounted for 39% of electric power generation in 2014, declined to 28% of the total in 2018; natural gas generation rose from 28% to 35% of the total, and wind and solar from 7% to 11% in the same period.10

As a result of this shift in power sources, emissions of CO2 from the electric power sector have declined faster than would have been required by the CPP.11 Cheap and abundant natural gas, state and federal incentives to develop wind and solar power, and tighter EPA standards for non-CO2 emissions12 from coal-fired power plants have all played a role in this transition.

New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) for new and modified power plants, promulgated at the same time as the CPP, would affect fewer plants, but they too are controversial, because of the technology the rule assumed could be used to reduce emissions at new coal-fired units. As promulgated in 2015, the NSPS would have relied in part on carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology to reduce emissions by about 20% compared to the emissions of a state-of-the-art coal-fired plant without CCS. Critics stated that CCS is a costly and unproven technology, and because of this, the NSPS would effectively have prohibited the construction of new coal-fired plants. No operating commercial U.S. power plant was capturing and storing CO2 as of the date the rule was promulgated. (The first commercial CCS facility in the United States, the Petra Nova project at the W.A. Parish Generating Station in Texas, came on line in 2016.) For additional information on the Clean Power Plan and the 2015 NSPS, see CRS Report R44744, Clean Air Act Issues in the 115th Congress: In Brief.

Implementation of the CPP has been stayed by the Supreme Court since February 2016, pending the completion of judicial review. Prior to the stay, challenges to the rule were filed with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit by more than 100 parties, including 27 states. These challenges were consolidated into a single case, West Virginia v. EPA. The D.C. Circuit heard oral argument in the case in September 2016; as of this writing, the court has not issued a decision. (For a discussion of the legal issues, see CRS Report R44480, Clean Power Plan: Legal Background and Pending Litigation in West Virginia v. EPA.) The NSPS have also been challenged (North Dakota v. EPA). EPA requested (and the court granted) a pause in that litigation to give EPA time to conduct a review.

Under the Trump Administration, EPA has reviewed both the CPP and the NSPS. This review concluded, among other things, that the CPP exceeded EPA's statutory authority by using measures that applied to the power sector as a whole rather than measures carried out within an individual facility. The agency therefore proposed repeal of the CPP on October 16, 2017,13 and a rule to replace it (the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule) on August 21, 2018.14 The ACE rule would apply a narrower interpretation than the CPP of the best system of emission reduction (BSER), defining it as on-site heat rate improvements for existing coal-fired units.15 The rule would not establish a numeric performance standard for existing coal-fired units. Instead, EPA proposed a list of candidate technologies that would constitute the BSER. The ACE rule does not establish BSER for other types of existing power plants, such as natural gas single cycle or combined cycle plants or petroleum-fired plants.

EPA proposed two additional actions in ACE—one to revise regulations that implement CAA Section 111(d) and another to modify an applicability determination for a CAA preconstruction permitting program for new and modified stationary sources, known as New Source Review (NSR). The former seeks to codify EPA's current legal interpretation that states have broad discretion to establish emission standards consistent with BSER. The latter would revise the NSR applicability test for certain power plants and, according to EPA, prevent NSR from discouraging the installation of energy-efficiency measures. For more information about the ACE proposal, see CRS Report R45393, EPA's Affordable Clean Energy Proposal.

The agency has also proposed to replace the NSPS, on December 6, 2018.16 In the December 2018 proposal, EPA determined that the BSER for newly constructed coal-fired units, would be the most efficient demonstrated steam cycle in combination with the best operating practices. This proposed BSER would replace the determination from the 2015 rule, which identified the BSER as partial carbon capture and storage. According to the agency, "the primary reason for this proposed revision is the high costs and limited geographic availability of CCS."17

Another issue of interest to Congress relates to the agency's legal basis for the 2015 NSPS, including EPA's conclusion in 2015 that power plants emit a significant amount of CO2. Prior to the power sector GHG rules, EPA made two findings under CAA Section 202: (1) that GHGs currently in the atmosphere potentially endanger public health and welfare and (2) that new motor vehicle emissions cause or contribute to that pollution. These findings are collectively referred to as the endangerment finding. The endangerment finding triggered EPA's duty under CAA Section 202(a) to promulgate emission standards for new motor vehicles.18

In the 2015 NSPS rule, EPA concluded that it did not need to make a separate endangerment finding under Section 111, which directs EPA to list categories of stationary sources that cause or contribute significantly to "air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."19 EPA reasoned that because power plants had been listed previously under Section 111, it was unnecessary to make an additional endangerment finding for a new pollutant emitted by a listed source category.20 The agency also argued that, even if it were required to make a finding, electric generating units (EGUs) would meet that endangerment requirement given the significant amount of CO2 emitted from the source category.21

While neither ACE nor the 2018 NSPS rule proposes to reconsider the endangerment finding or the conclusions related to the endangerment finding in the 2015 NSPS, the 2018 NSPS requested comments on these issues, "either as a general matter or specifically applied to GHG emissions."22 For example, EPA noted that power sector GHG emissions are declining and requested comment on whether EPA has "a rational basis for regulating CO2 emissions from new coal-fired" units.23 EPA also requested comment on whether the CAA requires the agency to make an endangerment finding once for a source category or if the Act requires EPA to make a new endangerment finding each time it regulates an additional pollutant from a listed source category.

The repeal and replacement of these rules is still at the proposal stage. Repealing or replacing a promulgated rule requires the agency to follow the administrative steps involved in proposing and promulgating a new rule, including allowing public comment, and responding to significant comments upon promulgation of a final rule.24 Following promulgation, the repeal action and replacement rules are subject to judicial review. A large group of stakeholders, including some states, are seen as likely to oppose the changes associated with repealing the CPP and replacing it with ACE.

The EPA and judicial processes could be short-circuited by Congress, through legislation overturning, modifying, or affirming the CPP or NSPS. Congressional action is considered unlikely, however, as the threat of a filibuster, requiring 60 votes to proceed, could prevent Senate action.

The new House majority has expressed a strong interest in addressing climate change. As a result, oversight hearings are considered likely as EPA finalizes actions on the ACE rule and NSPS.

Standards for the Oil and Gas Industry

On June 3, 2016, EPA promulgated a suite of New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) under Section 111 of the Clean Air Act to set controls for the first time on methane emissions from sources in the crude oil and natural gas production sector and the natural gas transmission and storage sector.25 The rule builds on the agency's 2012 NSPS for volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions26 and would extend controls for methane and VOC emissions beyond the existing requirements to include new or modified hydraulically fractured oil wells, pneumatic pumps, compressor stations, and leak detection and repair at well sites, gathering and boosting stations, and processing plants. The Obama Administration stated that the rule was a key component under the "Climate Action Plan," and that the plan's Strategy to Reduce Methane Emissions27 was needed to set the United States on track to achieve the Administration's goal to cut methane emissions from the oil and gas sector by 40%-45% from 2012 levels by 2025, and to reduce all domestic greenhouse gas emissions by 26%-28% from 2005 levels by 2025.

Methane—the key constituent of natural gas—is a potent greenhouse gas with a global warming potential (GWP) more than 25 times greater than that of carbon dioxide. According to EPA's Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, methane is the second most prevalent GHG emitted in the United States from human activities, and over 30% of those emissions come from oil production and the production, transmission, and distribution of natural gas.28

EPA projected that the standards for new, reconstructed, and modified sources would reduce methane emissions by 510,000 tons in 2025, the equivalent of reducing 11 million metric tons of carbon dioxide.29 In conjunction with the proposal, EPA conducted a Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) that looked at the illustrative benefits and costs of the proposed NSPS: in 2025, EPA estimated the rule will have costs of $530 million and climate benefits of $690 million (in constant 2012 dollars). The rule would also reduce emissions of VOCs and hazardous air pollutants (HAPs). EPA was not able to quantify the benefits of the VOC/HAP reductions.

The methane rule is among the rules subject to review under Executive Order (E.O.) 13783, signed by President Trump on March 28, 2017. Section 7 of the E.O. directed EPA to review the rule for consistency with policies that the E.O. enumerates, and, if appropriate, as soon as practicable, to "suspend, revise, or rescind the guidance, or publish for notice and comment proposed rules suspending, revising, or rescinding those rules."30

On March 12, 2018, EPA published a final rule to make two "narrow" revisions to the 2016 NSPS. The rule removes the requirement that leaking components be repaired during unplanned or emergency shutdowns and provides separate monitoring requirements for well sites located on the Alaskan North Slope.31

On October 15, 2018, EPA proposed a larger set of amendments to the 2016 NSPS.32 The proposed changes would decrease the frequency for monitoring fugitive emissions at well sites and compressor stations; decrease the schedule for making repairs; expand the technical infeasibility provision for pneumatic pumps to all well sites; and amend the professional engineer certification requirements to allow for in-house engineers. Upon the proposal's release, the agency stated that it "continues to consider broad policy issues in the 2016 rule, including the regulation of greenhouse gases in the oil and natural gas sector," and that "these issues will be addressed in a separate proposal at a later date."33 The comment period for the proposed amendments closed on December 17, 2018.

Standards for Motor Vehicles

Controversy regarding GHG standards promulgated by the Obama EPA for new motor vehicles has surfaced under the Trump Administration. In May 2009, President Obama reached agreement with major U.S. and foreign auto manufacturers, the state of California (which has separate authority to set motor vehicle emission standards, if EPA grants a waiver), and other stakeholders regarding the substance of GHG emission and related fuel economy standards.34 A second round of standards for cars and light trucks, promulgated in October 2012,35 was also preceded by an agreement with the auto industry and key stakeholders. Under the agreements, EPA, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT, which has authority to set fuel economy standards), and California would establish "One National Program" for GHG emissions and fuel economy. The auto industry supported national standards, in part, to avoid having to meet standards on a state-by-state basis.

The second round of GHG standards for cars and light trucks is being phased in over model years (MY) 2017-2025. It would reduce GHG emissions from new light-duty vehicles (i.e., cars, SUVs, crossovers, minivans, and most pickup trucks) by about 50% compared to 2010 levels, and average fuel economy will rise to nearly 50 miles per gallon (mpg) when fully phased in, in 2025. As part of the rulemaking, EPA made a commitment to conduct a Mid-Term Evaluation (MTE) for the MY2022-2025 standards by April 2018. The agency deemed an MTE appropriate given the long time frame at issue, with the final standards taking effect as long as 12 years after promulgation. Through the MTE, EPA was to determine whether the standards for MYs 2022-2025 were still appropriate given the latest available data and information, with the option of strengthening, weakening, or retaining the standards as promulgated.

On November 30, 2016, EPA released a proposed determination under the MTE stating that the MY2022-2025 standards remained appropriate and that a rulemaking to change them was not warranted. EPA based its findings on a Technical Support Document, a previously released Draft Technical Assessment Report (which was issued jointly by EPA, DOT, and the California Air Resources Board [CARB]), and input from the auto industry and other stakeholders. The proposed determination opened a public comment period that ran through December 30, 2016. On January 12, 2017, the EPA Administrator made a final determination to retain the MY2022-2025 standards as originally promulgated.

This action accelerated the original timeline for the MTE (which called for a final determination by April 2018), and EPA announced it separately from any DOT (fuel economy) or California (GHG standard) process (California subsequently reaffirmed its commitment to the MY2022-2025 standards, on March 24, 2017). Critics reacted to the accelerated timetable by vowing to work with the Trump Administration to revisit EPA's determination—citing a "rush to judgment" that they argued contradicted the objectives of the One National Program. Among the potential revisions suggested by critics has been better harmonization of the existing EPA/DOT/CARB standards, easing the MY2022-2025 standards, or eliminating them entirely.

The Trump Administration reopened the MTE in mid-March 2017. On April 2, 2018, EPA released a revised final determination, stating that the MY2022-2025 standards are "not appropriate in light of the record before EPA and, therefore, should be revised." The notice stated that the January 2017 final determination was based on "outdated information, and that more recent information suggests that the current standards may be too stringent."36

Following the revised final determination, on August 24, 2018, EPA and DOT proposed amendments to the existing fuel economy and GHG emission standards. The proposal offers eight alternatives. The agencies' preferred alternative, if finalized, is to retain the existing standards through MY2020 and then to freeze the standards at this level for both programs through MY2026. The preferred alternative also removes the current CO2 equivalent air conditioning refrigerant leakage, nitrous oxide, and methane requirements after MY2020.37 The proposed standards would lead to an estimated average fuel economy of 37 mpg for MY2020-MY2026 vehicles, causing a projected increase in fuel consumption of about 0.5 million barrels per day, according to EPA and DOT. The agencies project a net benefit from revising the standards, relying on new estimates of compliance costs, fatalities, and injuries. The proposed standards were subject to public comment for 60 days following their publication in the Federal Register. Until the new rulemaking is completed, the standards promulgated in 2012 remain in effect. (For additional information, see CRS In Focus IF10871, Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards.)

Further, under the proposal, EPA aims to withdraw California's CAA preemption waiver for its vehicle GHG standards applicable to MYs 2021-2025. DOT contends that the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), which authorizes the department's fuel economy standards, preempts California's GHG emission standards. DOT argues that state laws regulating or prohibiting tailpipe CO2 emissions are related to fuel economy and can therefore be preempted under EPCA. The agencies accepted comments on the proposal through October 26, 2018.

EPA and DOT have also promulgated joint GHG emission and fuel economy standards for medium- and heavy-duty trucks,38 which have generally been supported by the trucking industry and truck and engine manufacturers. This rule was finalized on August 16, 2016.39 The new standards cover MYs 2018-2027 for certain trailers and model years MYs 2021-2027 for semi-trucks, large pickup trucks, vans, and all types and sizes of buses and work trucks. According to EPA,

The Phase 2 standards are expected to lower CO2 emissions by approximately 1.1 billion metric tons, save vehicle owners fuel costs of about $170 billion, and reduce oil consumption by up to 2 billion barrels over the lifetime of the vehicles sold under the program.40

In the Regulatory Impact Analysis accompanying the rule's promulgation, EPA projected the total cost of the Phase 2 standards at $29-$31 billion over the lifetime of MY2018-2029 trucks. The standards would increase the cost of a long haul tractor-trailer by as much as $13,500 in MY2027, according to the agency; but the buyer would recoup the investment in fuel-efficient technology in less than two years through fuel savings. In EPA's analysis, fuel consumption of 2027 model tractor-trailers will decline by 34% as a result of the rule.41

In general, the truck standards have been well received. The American Trucking Associations, for example, described themselves as "cautiously optimistic" that the rule would achieve its targets: "We are pleased that our concerns such as adequate lead-time for technology development, national harmonization of standards, and flexibility for manufacturers have been heard and included in the final rule."42 The Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association highlighted its work providing input to assure that EPA and DOT established a single national program, and concluded: "A vitally important outcome is that EPA and DOT have collaborated to issue a single final rule that includes a harmonized approach to greenhouse gas reductions and fuel efficiency improvements."43

To date, neither group has filed a petition for judicial review of the rule. The only challengers were the Truck Trailer Manufacturers Association and the Racing Enthusiasts and Suppliers Coalition. In April 2017, EPA took steps to review the rule, asking the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals to hold the legal challenge (Truck Trailer Manufacturers Association v. EPA) in abeyance while EPA conducts a review of the standards. The court granted EPA's request on May 8, 2017. On October 27, 2017, the D.C. Circuit Court granted the Truck Trailer Manufacturers Association's request to stay certain requirements for trailers pending the judicial review of the medium- and heavy-duty vehicles rule.44 The rest of the rule remains in effect. (For additional information, see CRS In Focus IF10927, Phase 2 Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Fuel Efficiency Standards for Medium- and Heavy-Duty Engines and Vehicles.)

The truck rule also established emission standards for vehicles manufactured from "glider kits" (truck bodies produced without a new engine, transmission, or rear axle). On November 16, 2017, EPA proposed a repeal of the emission standards and other requirements on heavy-duty glider vehicles, glider engines, and glider kits based on a proposed interpretation of the CAA.45 EPA's proposed repeal has not been finalized, and efforts to expedite the proposal and/or provide regulatory relief to the industry have been met with resistance from a number of states, environmental groups, and stakeholders in the trucking sector. EPA's fall 2018 regulatory agenda characterizes its glider rulemaking as a "long-term action," which is defined as a measure for which the agency "does not expect to have a regulatory action within" a year of publishing the agenda. (For additional information, CRS Report R45286, Glider Kit, Engine, and Vehicle Regulations.)

Air Quality Standards

Background

Air quality has improved substantially since the passage of the Clean Air Act in 1970. Annual emissions of the six air pollutants for which EPA has set national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS)—ozone, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and lead—have declined by more than 70%, despite major increases in population, motor vehicle miles traveled, and economic activity.46 Nevertheless, the goal of clean air continues to elude many areas, in part because evolving scientific understanding of the health effects of air pollution has caused EPA to tighten standards for most of these pollutants. Congress anticipated that the understanding of air pollution's effects on public health and welfare would change with time, and it required, in Section 109(d) of the act, that EPA review the NAAQS at five-year intervals and revise them, as appropriate.

The most widespread air quality problems involve ozone and fine particles (often referred to as "smog" and "soot," respectively). A 2013 study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology concluded that emissions of particulate matter (PM) and ozone caused 210,000 premature deaths in the United States in 2005.47 Many other studies have found links between air pollution, illness, and premature mortality, as well. EPA summarizes these studies in what are called Integrated Science Assessments (ISAs) and Risk Analyses when it reviews a NAAQS. The most recent ISA for particulate matter—a draft version that EPA published as part of the PM NAAQS review currently underway—concludes that there is a "causal relationship" between total mortality and both short-term and long-term exposure to PM.48 The most recent ozone ISA states that there is "likely to be a causal relationship" between short-term exposures to ozone and total mortality.49

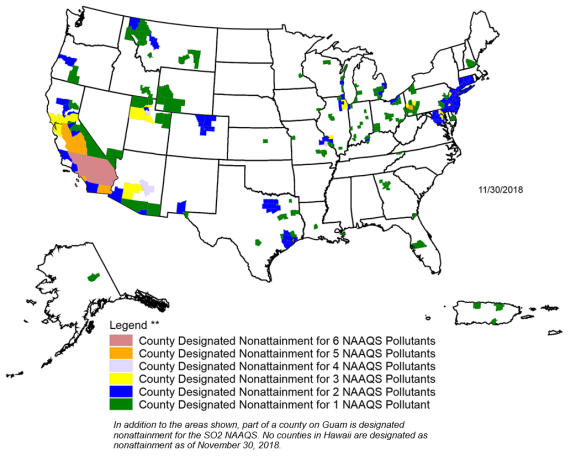

With input from the states, EPA identifies areas where concentrations of pollution exceed the NAAQS following its promulgation. As of November 30, 2018, 124 million people lived in areas classified as "nonattainment" for the ozone NAAQS; 31 million lived in areas that were nonattainment for the fine particulate matter (PM2.5) NAAQS.50

Figure 1 identifies areas that had not attained one or more of the NAAQS as of November 30, 2018.

|

Figure 1. Counties Designated Nonattainment for One or More NAAQS |

|

|

Source: U.S. EPA Green Book, https://www3.epa.gov/airquality/greenbook/map/mapnpoll.pdf. Map shows areas designated nonattainment as of November 30, 2018. Partial counties, those with part of the county designated nonattainment and part attainment, are shown as full counties on the map. In addition to the areas shown, part of a county on Guam is designated nonattainment for the SO2 NAAQS. No counties in Hawaii are designated as nonattainment as of November 30, 2018. |

EPA's Review of the NAAQS

EPA's statutorily mandated reviews of the ozone and particulate matter NAAQS are underway and may be more contentious than usual. The Clean Air Act has minimal requirements for how the agency is to conduct NAAQS reviews, leaving the details to the EPA Administrator. Congress may undertake oversight, as EPA moves forward with these reviews.

EPA also intends to streamline NAAQS reviews and obtain Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC) advice regarding background pollution and potential adverse effects from NAAQS compliance strategies.51 In October 2018, EPA made an unprecedented change and eliminated the pollutant-specific scientific review panels, which have historically helped agency staff conduct the five-year reviews. Specifically, EPA disbanded the Particulate Matter Review Panel, which was appointed in 2015, and stated that it would not form an Ozone Review Panel. Instead, the seven-member CASAC is to lead "the review of science for any necessary changes" to the ozone or particulate matter NAAQS.52 Several members of the current CASAC, however, raised concerns about the lack of a scientific ozone review panel and commented that EPA should form one.53 Others, including former members of CASAC and previous ozone review panels, stated that the current CASAC lacks the depth and breadth of expertise required for the ozone review.54 Additional stakeholder views—in particular, those that may support this particular change—are not readily available.

2020 Review of the Ozone NAAQS

Since 2008, review of the NAAQS for ozone has sparked recurrent controversy. In 2008, EPA promulgated a more stringent ozone NAAQS, and for the first time ever, the Administrator chose a health-based standard outside the range recommended by the independent scientific review committee established by the Clean Air Act. In 2015, EPA strengthened the ozone NAAQS again.55

The final ozone standards were released on October 1, 2015, and appeared in the Federal Register, October 26, 2015. Areas of the United States exceeding the new NAAQS were identified on May 1 and July 17, 2018. The standards have been challenged in court; the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral argument in the case on December 18, 2018.56

The 2015 revision sets more stringent standards than the 2008 ozone NAAQS, lowering both the primary (health-based) and secondary (welfare-based) standards57 from 75 parts per billion (ppb)—the level set in 2008—to 70 ppb. EPA has identified 52 "nonattainment" areas with a combined population of 124 million, where air quality exceeds the new NAAQS: 201 counties or partial counties in 22 states, the District of Columbia, and 2 tribal areas. EPA's analysis of the rule's potential effects undertaken when the rule was promulgated showed all but 14 of the nonattainment counties could reach attainment with a 70 ppb ozone NAAQS by 2025 as a result of already promulgated standards for power plants, motor vehicles, gasoline, and other emission sources.58

EPA estimated the cost of meeting a 70 ppb ozone standard in all states except California at $1.4 billion annually in 2025.59 Because most areas in California would have until the 2030s to reach attainment,60 EPA provided separate cost estimates for California ($0.8 billion in 2038). These cost estimates are substantially less than widely circulated estimates from the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) and other industry sources. For a discussion of the differences, see CRS Report R43092, Implementing EPA's 2015 Ozone Air Quality Standards.

EPA faces a statutory deadline of October 2020 to complete a review of the ozone NAAQS and decide whether to modify or retain it. As previously noted, the agency announced plans to speed up the review process and declined to convene a scientific review panel. EPA is expected to grapple with issues raised during the 2015 ozone review, such as background ozone. In addition, EPA stated that it intends to seek CASAC advice regarding potential adverse effects from NAAQS compliance strategies.61

2020 Review of Particulate Matter NAAQS

EPA completed its most recent review of the particulate matter NAAQS in late 2012 and promulgated revisions to strengthen the standards.62 During the 2012 particulate matter review, congressional deliberations focused on the regulatory costs associated with implementing more stringent standards as well as the potential impacts on economic growth, employment, and consumers. Some Members of Congress also raised concerns about potential impacts that more stringent particulate matter standards may have on industry and agricultural operations. For more information about the 2012 revision and related congressional deliberations, see CRS Report R42934, Air Quality: EPA's 2013 Changes to the Particulate Matter (PM) Standard.

EPA initiated the current particulate matter review in 2014.63 In October 2018, EPA released a draft version of its Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter to CASAC for review and public comment.64 The Integrated Science Assessment, which summarizes the scientific literature published since the last NAAQS review, serves as the scientific basis for reviewing the NAAQS. EPA stated that it intends to complete the particulate matter NAAQS review by December 2020.65

Other Issues

Other issues are likely to arise as EPA continues to review CAA regulations. Three regulations currently under review involve air toxics emitted by power plants, particulate matter from wood heaters, and air toxics from brick and ceramic kilns.

Air Toxics from Power Plants

EPA is reviewing the benefit-cost analysis it prepared in 2011 for the Mercury and Air Toxics (MATS) rule, raising questions about whether the agency will take additional action on the rulemaking in 2019. Promulgated in February 2012, the MATS rule established Maximum Achievable Control Technology (MACT) standards under Section 112 of the CAA to reduce mercury and acid gases from most existing coal- and oil-fired power plants.66 EPA's 2011 analysis estimated that the annual benefits of the MATS rule, including the avoidance of up to 11,000 premature deaths annually, would be between $37 billion and $90 billion.67 Virtually all of the avoided deaths and monetized benefits come from the rule's effect on emissions of particulates, rather than from identified effects of reducing mercury and air toxics exposure. Numerous parties petitioned the courts for review of the rule, contending in part that EPA had failed to conduct a benefit-cost analysis in its initial determination that control of air toxics from electric power plants was "appropriate and necessary." In June 2015, the Supreme Court agreed with the petitioners, remanding the rule to the D.C. Circuit for further consideration.

EPA prepared a supplemental "appropriate and necessary" finding based on the agency's review of the 2012 rule's estimated costs in 2016. The 2016 supplemental finding concluded that it is appropriate and necessary to regulate air toxics, including mercury, from power plants after including a consideration of the costs.68

As of this writing, the MATS rule remains in effect and litigation remains on hold, at the agency's request. On December 27, 2018, however, in a "Revised Supplemental Cost Finding," EPA proposed to reverse the 2016 finding that it is appropriate and necessary to regulate air toxics under Section 112. The proposal, even when finalized, would not revoke the MATS rule. That would require a separate regulatory action, which EPA has not proposed.69

Wood Heaters

In 2015, EPA published final emission standards for new residential wood heaters, including wood stoves, pellet stoves, hydronic heaters, and forced air furnaces. The 2015 wood heater regulations generated a substantial amount of interest, particularly in areas where wood is used as a heating fuel. House and Senate hearings in the 115th Congress highlighted concerns about inadequate time to demonstrate compliance with emission standards by the 2020 deadline. Others have expressed concerns about the air quality impacts of delaying the 2020 deadline. On March 7, 2018, the House passed H.R. 1917, which would have delayed implementation of the standards for three years.

More recently, EPA proposed to add a two-year "sell-through" period for new hydronic heaters and forced-air furnaces.70 Specifically, EPA's proposal would allow all affected new hydronic heaters and forced-air furnaces that are manufactured or imported before the May 2020 deadline to be sold at retail through May 2022. In addition, EPA published an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPR) in late 2018 on new residential wood heaters, new residential hydronic heaters, and new residential air furnaces. The 2018 ANPR does not propose specific changes to the standards, but it requests comments on various regulatory issues "in order to inform future rulemaking to improve these standards and related test methods."71 Citing stakeholder feedback about ways to improve implementation of the 2015 NSPS, EPA requested comment on 10 topics, including the cost and feasibility of meeting the emission limits that become effective in 2020, the timing of the 2020 compliance date, and test methods used for certification. For additional information on the wood heater rule, see CRS Report R43489, EPA's Wood Stove / Wood Heater Regulations: Frequently Asked Questions.

Brick and Clay Maximum Achievable Control Technology

Emission standards that EPA promulgated for brick, structural clay, and ceramic clay kilns in 2015 may also garner interest in the 116th Congress. The 2015 rulemaking established standards for mercury, particulate matter, acid gases, dioxins, and furans. EPA estimated the cost of the rule at $25 million annually, with monetized co-benefits three to eight times the cost. The Brick Industry Association called the proposal "a much more reasonable rule than the one EPA first envisioned several years ago," but they and others have continued to express concerns regarding the cost and achievability of the standards. Environmental groups and an association of state air pollution officials are concerned for different reasons: in their view, EPA improperly set standards under a section of the CAA that allows an alternative to the MACT requirement that generally applies to hazardous air pollutant standards. After reviewing petitions filed by industry groups and environmental groups, the D.C. Circuit in 2018 ordered EPA to revise the 2015 standards but did not vacate them.