In the midst of ongoing concerns about illicit drug use and abuse, there has been heightened attention to the issue of opioid abuse—including both prescription opioids and nonprescription opioids such as heroin.1 The increased attention to opioid abuse and addiction first centered on the abuse of prescription painkillers. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), about 3.3 million individuals were current (at least once in the past month) nonmedical users of prescription pain relievers such as OxyContin in 2016.2 Mirroring the nation's concern about prescription drug abuse, there has been corresponding unease regarding the rise in heroin abuse.

According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, there were an estimated 948,000 individuals (0.4% of the 12 and older population) who reported using heroin within the past year—up from 0.2% to 0.3% of this population reporting use in the previous decade.3 In addition, about 626,000 individuals (0.2% of the 12 and older population) had a heroin use disorder in 2016.4 While this is similar to the proportion of the 12 and older population with a heroin use disorder from 2011 to 2015, it is significantly greater than the proportion from 2002 to 2010. Further, heroin overdose deaths increased by about 20% nationally between 2015 and 2016,5 and the Midwest and Northeast regions have been highlighted as areas of particular concern.6

In addition to increases in heroin use and abuse, there has been a simultaneous increase in its availability in the United States over the past decade.7 This has been fueled by a number of factors, including increased production and trafficking of heroin—principally by Mexican criminal networks. Mexican drug traffickers have been expanding their control of the U.S. heroin market, though the United States still receives some heroin from South America and Southwest Asia as well.8 Notably, while the majority of the world's opium is produced in Afghanistan,9 only a small proportion of that feeds the U.S. heroin market.

Policymakers may want to examine U.S. efforts to counter heroin trafficking as a means of addressing opioid abuse in the United States. This report provides an overview of heroin trafficking into and within the United States. It includes a discussion of links between the trafficking of heroin and the illicit movement of related substances such as controlled prescription opioids and synthetic substances like fentanyl. The report also outlines existing U.S. efforts to counter heroin trafficking and possible congressional considerations going forward.10

Heroin Traffickers

Mexican transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) "remain the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States; no other group is currently positioned to challenge them."11 They are the major suppliers and key producers of most illegal drugs smuggled into the United States, and they have been increasing their share of the U.S. drug market—particularly with respect to heroin.12

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) notes that Mexican criminal organizations move most of their illegal goods over the Southwest border through ports of entry in passenger vehicles or tractor trailers.13 In passenger vehicles, the drugs may be held in secret compartments; while in tractor trailers, the drugs are often mingled with other legitimate goods. Less commonly used methods to move drugs into the United States include smuggling them through cross-border underground tunnels and on commercial cargo trains, small boats, and ultralight aircraft.14

|

Heroin Production Created from the morphine molecule of the opium poppy, heroin can be produced in a number of purity grades (white powder heroin being the most pure and black tar heroin being the least) and can be administered through a number of means (e.g., smoking, snorting, or injecting). In the process of creating heroin, "[w]hite heroin is made by isolating morphine from opium and then synthesizing heroin from morphine."15 Producing black tar heroin, however, "skips the intermediate step of morphine isolation and synthesizes heroin straight from the opium."16 As such, producing black tar heroin is faster and less costly than producing white heroin and thus it may be a cheaper high for opioid abusers. |

Mexican criminal networks have not always featured so prominently (or broadly) in the U.S. heroin market. Historically, Colombian criminal organizations controlled heroin markets in the Midwest and on the East Coast.17 Now, supply for these markets also comes directly from Mexican traffickers. The DEA indicates that "[s]ince 2015 most of the heroin sold in the U.S. is from Mexico."18 Mexican poppy cultivation reportedly increased by 35% from 2016 to 2017; officials project that the estimated 44,100 hectares cultivated in 2017 allowed for about 111 metric tons of pure heroin production.19

The DEA has observed that "[t]he increased role of Mexican traffickers is affecting heroin trafficking patterns."20 Historically, Mexican-produced black tar and brown powder heroin have been consumed in markets west of the Mississippi River, while markets east of the Mississippi have consumed more white powder heroin from South America. However, as the Mexican traffickers have taken on a larger role in the U.S. heroin market and have developed techniques to produce white powder heroin, they have moved their white powder heroin into both eastern and western U.S. markets.21

To facilitate the distribution and local sale of drugs in the United States, Mexican drug traffickers have sometimes formed relationships with U.S. gangs.22 Trafficking and distribution of illicit drugs is a primary source of revenue for these gangs23 and among the most common of their criminal activities.24 Gangs may work with a variety of drug trafficking organizations, and are often involved in selling multiple types of drugs besides heroin or other opioids.25

Heroin Seizures

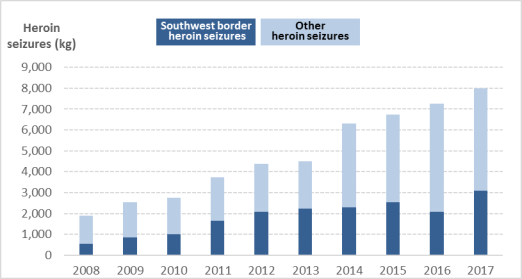

The majority of heroin making its way to the United States originates in Mexico and, to a lesser degree, Colombia.26 The amount of heroin seized across the United States, including at the Southwest border, has generally increased over the past decade, as illustrated in Figure 1. Nationwide heroin seizures reached 7,979 kg in 2017, with 3,090 kg (39%) seized at the Southwest border.27

|

Figure 1. Heroin Seized in the United States 2008–2017 |

|

|

Source: National Seizure System data, as provided to CRS by the DEA, July 27, 2018. |

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has outlined how seizure data can be used in combination with data on drug prices and purity to help serve as a drug market indicator. The UNODC notes that "[f]alling seizures in combination with rising drug prices and falling purity levels may suggest a decline in overall drug supply, while rising seizures in combination with falling drug prices and rising purity levels are usually considered a good indicator of an increase in drug supply."28

The UNODC's model can be applied to heroin seizure data to help assess the scope of the heroin market in the United States. Notably, heroin seizures have generally been increasing, as illustrated in Figure 1. In addition, the average purity of retail-level heroin has been between 31% and 39% from 2012 to 2016;29 while the purity has fluctuated somewhat, it has remained elevated relative to levels in the 1980s.30 And while the retail-level price per gram has vacillated over the past couple of decades, it has remained lower than prices in the 1980s.31 This combination of seizures, purity, and price could indicate that there is an increased heroin supply for the U.S. market. Experts have noted an increase in Mexican heroin production, which is primarily destined for the United States.

The increase in seizures, however, may reflect more than just increases in the heroin supply and demand in the U.S. market. This could also be driven by factors such as enhanced U.S. law enforcement efforts to interdict and seize the contraband and/or by less stringent efforts by traffickers and buyers to conceal the drugs.

Arrests and Prosecutions

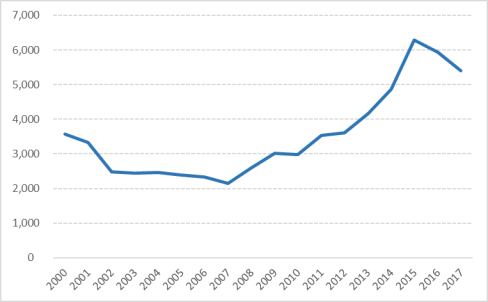

Data from the DEA indicate that many of their heroin-related arrests are for trafficking-related offenses. In 2017, the DEA made 5,408 heroin-related arrests. The bulk of these were made for conspiracy (35%), distribution (24%), possession with intent32 (23%), and simple possession (11%). Other offense categories for which a much smaller proportion of arrests were made include importation, manufacture, RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization), and CCE (continuing criminal enterprise).33 In other words, more of these heroin-related arrests were for offenses that may be considered to fall under the umbrella of trafficking rather than simple possession.34 DEA heroin arrest data indicate that since remaining relatively flat in the mid-2000s, overall heroin arrests generally increased through 2015 before declining through 2017 (see Figure 2).35

|

2000–2017 |

|

|

Source: Data provided to CRS by the DEA, July 27, 2018. |

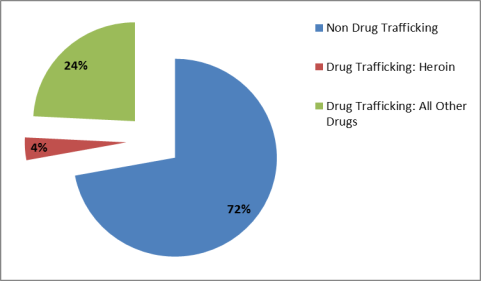

The U.S. Sentencing Commission reports that 2,658 individuals were sentenced for heroin trafficking offenses in U.S. District Courts in FY2017.36 While this was a decrease from FY2016, the number of individuals sentenced for heroin trafficking has generally moved upward over the past decade.37 FY2017 data indicate that of the 19,240 cases involving individuals sentenced for drug trafficking offenses, 2,658 (13.8%) involved individuals who were sentenced for heroin trafficking.38 That amounts to 4% of all cases sentenced in U.S. District Courts. (See Figure 3.)

Links to Related Substances

Prescription Opioids

Some have theorized that prescription opioid abuse may lead to, or be a "gateway" for, abuse of nonprescription opioids such as heroin. Results from one SAMHSA study indicate that the "recent (12 months preceding interview) heroin incidence rate was 19 times higher among those who reported prior nonmedical pain reliever (NMPR) use than among those who did not (0.39% vs. 0.02%)."39 However, while "four out of five recent heroin initiates (79.5%) previously used NMPR ... the vast majority of NMPR users have not progressed to heroin use."40 The 2016 National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary notes that about 4% of individuals who abuse prescription drugs will go on to use heroin.41

One factor that may sway opioid abusers' shifts from prescription opioids to heroin may be the cost. If users cannot afford prescription opioids, they may switch to heroin as a lower-cost alternative. While estimates vary, some have noted that an 80 mg pill of OxyContin (a prescription opioid containing oxycodone) can cost $80 on the street; a bag of heroin can cost $5-$10.42 The DEA reported that drug trafficking organizations have responded to the demand for lower cost opioids by sometimes shifting heroin trafficking operations to areas with higher prevalence of nonmedical prescription drug use.43

Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is approximately 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine. There are both legal and illegal forms of fentanyl. Legal fentanyl has pharmaceutical uses for treating post-operative pain and chronic pain associated with late stage cancer, and illicit fentanyl is sold on the black market and used/abused in similar ways as other opioid drugs.

Most cases of fentanyl-related overdoses are associated with non-pharmaceutical, illegal fentanyl;44 non-pharmaceutical fentanyl is often mixed with heroin and/or other drugs, sometimes without the consumer's knowledge. Some have purported that fentanyl is easier to mix with white powder heroin than with the black tar variety.45 As such, there have reportedly been more fentanyl-related overdose deaths in U.S. markets fueled by white powder heroin than those dominated by the black tar form. However, this could change as distributors are finding ways to incorporate fentanyl into the black tar heroin.46

Non-pharmaceutical fentanyl found in the United States is manufactured in China and Mexico.47 It is trafficked into the United States across the Southwest border or delivered through mail couriers directly from China, or from China through Canada.48 In addition, fentanyl-related substances—substances that are in the fentanyl chemical family but have minor variations in chemical structure—may be attractive to traffickers because the analogs are often unscheduled or unregulated.49 Like fentanyl, they can be sold as, or mixed in with, heroin or pressed into counterfeit pills.

The DEA indicates that the majority of seized fentanyl samples analyzed involved fentanyl in powder form.50 However, law enforcement is concerned about the risks from fentanyl being pressed into counterfeit pills, in part, because there are more abusers of prescription pain pills than of heroin. As such, fentanyl pressed into counterfeit pills could ultimately affect a larger population of individuals.51

U.S. Heroin Trafficking Enforcement Efforts

The United States confronts the drug problem through a combination of efforts targeting both the supply of and demand for drugs. As such, the Administration has directed resources into the areas of law enforcement initiatives, prevention, and treatment. In targeting one element of the drug problem—trafficking—U.S. efforts have centered on law enforcement initiatives.

There are a number of federal law enforcement activities aimed specifically at (or which may be tailored to) curbing heroin trafficking. This section contains a snapshot of some of these efforts.

DEA 360 Strategy

The DEA has developed a 360 Strategy aimed at "tackling the cycle of violence and addiction generated by the link between drug cartels, violent gangs, and the rising problem of prescription opioid and heroin abuse."52 The strategy was launched in November 2015 as a pilot program in Pittsburgh, PA, and has since expanded to other cities.53 It leverages federal, state, and local law enforcement, diversion control, and community outreach organizations. As the program is relatively new, there have only been anecdotal reports of the operations that fall under the 360 Strategy framework, and an outcome evaluation of the strategy has not been conducted.

Heroin and Fentanyl Signature Programs

The DEA operates a heroin signature program (HSP) and a heroin domestic monitor program (HDMP), with the goal of identifying the geographic source of heroin found in the United States. The HSP analyzes wholesale-level samples of "heroin seized at U.S. ports of entry (POEs), all non-POE heroin exhibits weighing more than one kilogram, randomly chosen samples, and special requests for analysis."54 Chemical analysis of a given heroin sample can identify its "signature," which indicates a particular heroin production process that has been linked to a specific geographic source region. The HDMP assesses the signature source of retail-level heroin seized in the United States. This program samples retail-level heroin seized in 27 cities across the country and provides data on the price, purity, and geographic source of the heroin.55 The results from the HSP and HDMP can be used to help understand trafficking and distribution patterns throughout the country. The HSP started in 1977, and the HDMP began in 1979.

The HSP tests about 600-900 heroin samples annually.56 In 2016, the HSP tested 744 samples from seizures totaling 1,632 kg—slightly more than 22% of the total heroin seized that year.57 Of the heroin analyzed in the HSP in 2016, 86% was identified as originating from Mexico, 10% was inconclusive,58 4% was from South America, and less than 1% was from Southwest Asia. Wholesale-level Mexican white powder heroin produced with South American techniques had an average purity of 82%.59 Data from the HDMP indicate that retail-level Mexican white powder heroin produced with South American techniques had an average purity of 39.7% in 2016.60

The DEA has also started a Fentanyl Signature Profiling Program (FSPP), analyzing samples from fentanyl seizures to help "identify the international and domestic trafficking networks responsible for many of the drugs fueling the opioid crisis."61 In 2017, the FSPP analyzed 520 fentanyl powder samples from seizures totaling 960 kg of fentanyl. While the average purity was 5%, the DEA has indicated that fentanyl shipped directly from China often has purity levels above 90%, while fentanyl trafficked over the Southwest border from Mexico often has purity levels below 10%.62

HIDTA

The High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) program provides assistance to law enforcement agencies—at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels—that are operating in regions of the United States that have been deemed critical drug trafficking areas. There are 29 designated HIDTAs throughout the United States and its territories.63 Administered by the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), the program aims to reduce drug production and trafficking through four means:

- promoting coordination and information sharing between federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement;

- bolstering intelligence sharing between federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement;

- providing reliable intelligence to law enforcement agencies such that they may be better equipped to design effective enforcement operations and strategies; and

- promoting coordinated law enforcement strategies that rely upon available resources to reduce illegal drug supplies not only in a given area, but throughout the country.64

The HIDTA program does not mandate that all regional HIDTAs focus on the same drug threat—such as heroin trafficking; rather, funds can be used to support the most pressing drug threats in the region. As such, when heroin trafficking is found to be a top priority in a HIDTA region, funds may be used to support initiatives targeting it.

In 2015, ONDCP launched the Heroin Response Strategy (HRS), "a multi-HIDTA, cross-disciplinary approach that develops partnerships among public safety and public health agencies at the Federal, state and local levels to reduce drug overdose fatalities and disrupt trafficking in illicit opioids."65 Within the HRS, a Public Health and Public Safety Network coordinates teams of drug intelligence officers and public health analysts in each state. The HRS not only provides information to these participating entities on drug trafficking and use, but it has "developed and disseminated prevention activities, including a parent helpline and online materials."66

Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF)

The OCDETF program targets—with the intent to disrupt and dismantle—major drug trafficking and money laundering organizations. Federal agencies that participate in the OCDETF program include the DEA; Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI); Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF); U.S. Marshals; Internal Revenue Service (IRS); U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); U.S. Coast Guard (USCG); Offices of the U.S. Attorneys; and the Department of Justice's (DOJ's) Criminal Division. These federal agencies also collaborate with state and local law enforcement on task forces.67 There are 14 OCDETF strike forces around the country and an OCDETF Fusion Center that gathers and analyzes intelligence and information to support OCDETF operations. The OCDETFs target those organizations that have been identified on the Consolidated Priority Organization Targets (CPOT) List, the "most wanted" list for leaders of drug trafficking and money laundering organizations. During FY2017, 20% (932) of active OCDETF investigations were linked to valid CPOTs.68 Notably, 50% of the FY2017 CPOT investigations involved heroin trafficking.69

COPS Anti-Heroin Task Force Program

Within DOJ, the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Office's Anti-Heroin Task Force (AHTF) Program provides funding assistance to state law enforcement agencies to investigate illicit activities related to the trafficking or distribution of heroin or diverted prescription opioids. While the AHTF program is not a federal enforcement program, it is a federal grant program that exclusively provides money targeted specifically for heroin trafficking enforcement efforts.70 Funds cannot be used for treatment or other purposes because the program focuses on trafficking and distribution. Further, the program focuses its funding on state law enforcement agencies with multi-jurisdictional reach and interdisciplinary team structures—such as task forces.71 For FY2017, grants were awarded to entities in eight states.72

Going Forward

Adequacy of Data on Heroin Flows

What is known about heroin trafficking flows is contingent on a number of factors surrounding the collection and reporting of these data, which are both multifaceted and incomplete. Data on various elements (e.g., production, price, purity, seizures, etc.) can help provide insight into the landscape of heroin trafficking, though these data are sometimes imprecise.

For example, as the bulk of heroin consumed in the United States has been traced to Mexico, one central piece of data in understanding trafficking flows to the United States is the total potential production in the source countries. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has noted, however, that "[o]nly partial information about the extent of opium poppy cultivation and heroin production in the Americas is available."73 The DEA's 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment estimates that Mexico may have cultivated 44,100 hectares of opium poppy in 2017, potentially yielding 111 metric tons of pure heroin.74 This is 38% higher than the estimated production in 2016. In the past, officials have noted that crop yield data are unreliable,75 and it is unclear whether the newer data are more reliable. Even with these questions about the data's reliability, U.S. officials state that production of heroin in Mexico has increased. While much of Mexican-produced heroin is reportedly destined for the United States, that proportion is unknown.

In addition, it is unknown how much pure heroin is making its way into the United States. Data on seizures are available, but these reflect an unknown portion of total drugs traversing U.S. borders. In addition, as noted, officials have estimated heroin availability in the United States based, in part, on estimated production, known seizures, and the price and purity of select samples of wholesale and retail-level heroin, but these numbers collectively represent an imprecise picture of heroin trafficking. Policymakers may, in their oversight of efforts to counter the flow of heroin into the country, assess means to bolster the accuracy and completeness of data.

Prioritizing Heroin Trafficking Enforcement

Over the past few years, officials have repeatedly referred to heroin as a top drug threat in the United States. The 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment notes that heroin is one of the most significant drug threats.76 This is largely based on the health risks—overdose and death—posed by these substances. Nationally, however, federal law enforcement seizures of heroin have generally increased in the past several years, as illustrated in Figure 1. Policymakers may question whether federal enforcement efforts prioritize curbing heroin trafficking to an extent commensurate with the reported threat of the drug. While seizures have generally increased both along the Southwest border and throughout the country, it is unclear whether enforcement efforts should, or are able to, increasingly target heroin trafficking networks.

In addition, law enforcement data indicate that there have been changes in heroin trafficking patterns along the Southwest border. For instance, from 2016 to 2017 heroin trafficking, by weight, increased 238% in the El Centro corridor, 174% in the Del Rio corridor, and 104% in the Yuma corridor, while it declined in other areas such as the Rio Grande Valley (by 24%).77 Policymakers may ask if heroin enforcement efforts are nimble and able to respond (and if so, how) to shifts in heroin trafficking patterns and maximize seizures in the areas where heroin flows are increasing.

ONDCP has noted that the "responsibility for curbing heroin production and trafficking lies primarily with the source countries."78 Policymakers may examine the balance of resources targeted toward domestic efforts to reduce drug trafficking through interdiction and prosecution relative to resources dedicated to eradication, alternative economic development, and other options abroad.79

Evaluating Goals and Outcomes of U.S. Strategies

The United States has a number of strategies and initiatives targeting illicit drugs. While they do not all focus on drug trafficking per se—or even more specifically, heroin trafficking—their goals include reducing drug trafficking. Policymakers may evaluate whether these strategies and initiatives are sufficient to effectively respond to the threat of heroin trafficking in the United States as well as to the role heroin trafficking may play in the opioid epidemic. If not, how might a strategy look that focuses specifically on heroin/opioid trafficking, and would such a strategy be nimble enough to counter the constantly evolving drug trafficking threats facing the United States? Examples of existing efforts are outlined here.

National Drug Control Strategy

ONDCP is charged with coordinating federal drug control policy.80 In doing so, ONDCP is responsible for producing the annual National Drug Control Strategy (strategy), the purpose of which is to outline a plan to reduce illicit drug consumption in the United States and the consequences of such use.81 The most recent strategy was released in 2016.82 The 2016 strategy prioritizes seven approaches to reduce both illicit drug use and its consequences:

- preventing drug use in U.S. communities;

- seeking early intervention opportunities in health care;

- increasing access to treatment and supporting recovery;

- reforming the criminal justice system to better address substance use disorders;

- disrupting domestic drug trafficking and production;

- bolstering international partnerships; and

- improving information systems for analysis, assessment, and management.83

Each of these approaches is based on several principles and fosters certain federal drug control activities.84 While these approaches and principles are not necessarily directed at countering heroin trafficking, they focus on confronting the top drug threats, which have in recent years involved heroin trafficking and its role in the opioid epidemic. Notably, the 2016 strategy identified the greatest drug threat to the United States as "the continuing opioid epidemic, which began with the overprescribing of powerful long-acting, time-released opioid medications … [and] was further complicated by a sharp increase in the supply and subsequent use of high purity, low cost heroin produced in Mexico and Colombia and the trafficking of illicitly produced fentanyl."85 It is unclear whether the Trump Administration will release a strategy or how prominently countering heroin trafficking as it contributes to the opioid epidemic may feature in that strategy.

National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy

The National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy (NSBCS) was first launched in 2009, and it outlines domestic and transnational efforts to reduce the flow of illegal drugs, money, and contraband across the Southwest border. It has a number of strategic objectives:

- enhance intelligence and information sharing capabilities and processes;

- reduce the flow of drugs, drug proceeds, and associated instruments of crime that cross the Southwest border;

- develop strong, resilient communities that resist criminal activity and promote healthy lifestyles;

- disrupt and dismantle TCOs operating along the Southwest border;

- stem the flow of illicit proceeds across the Southwest border; and

- enhance U.S.-Mexican-Central American cooperation on joint counterdrug efforts.86

The 2016 NSBCS focuses on drug trafficking broadly, noting that the Southwest border is the primary entry point for many illegal drugs arriving in the United States. Nonetheless, it mentions that "the threat posed by heroin in the United States is serious and continues to intensify."87 The objectives and action items, however, target the broader array of drug and criminal threats at the border. It is unclear whether the Trump Administration will use the NSBCS, modify it, or develop other measures and strategies to counter the threats—including those posed by heroin trafficking—at the Southwest border.

National Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime

In July 2011, the Obama Administration released the Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime: Addressing Converging Threats to National Security.88 The strategy provided the federal government's first broad conceptualization of "transnational organized crime," highlighting it as a national security concern.89 It highlights 10 primary categories of threats posed by transnational organized crime, one of which is the expansion of drug trafficking. Additionally, the strategy outlines six key priority actions to counter threats posed by transnational organized crime:

- taking shared responsibility and identifying what actions the United States can take to protect against the threat and impact of transnational organized crime;

- enhancing intelligence and information sharing;

- protecting the financial system and strategic markets;

- strengthening interdiction, investigations, and prosecutions;

- disrupting drug trafficking and its facilitation of other transnational threats; and

- building international capacity, cooperation, and partnerships.

While this strategy is not tailored solely to drug trafficking (or more specifically, heroin trafficking) activities of criminal networks, it includes a discussion of the threat. Additionally, the strategy notes that a number of the threats outlined in the strategy may be facilitated by drug trafficking and the proceeds generated by those activities. For instance, the illicit drugs trade is at times linked to crimes such as weapons trafficking or human trafficking. Similar to the case with the NSBCS, it is unclear whether the Trump Administration will rely upon this strategy either broadly or more specifically to counter heroin trafficking.

Executive Orders

The Trump Administration has issued executive orders that could affect federal efforts to counter heroin trafficking, though they do not focus solely on them. For instance, the executive order Enforcing Federal Law with Respect to Transnational Criminal Organizations and Preventing International Trafficking,90 issued in February 2017, relies in part on the Threat Mitigation Working Group—which was established as part of the Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime—to, among other things, support and bolster U.S. efforts to counter criminal organizations. However, the executive order does not speak to the larger strategy or specific efforts to counter heroin trafficking. In addition, President Trump issued the executive order Establishing the President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis91 in March 2017. The commission's final report recommended a number of actions, including providing enhanced penalties for the trafficking of fentanyl and its analogues as well as bolstering tools and technologies to detect fentanyl before it enters the United States.92

National Heroin Task Force

The National Heroin Task Force was convened by DOJ and ONDCP in March 2015 pursuant to P.L. 113-235. The task force examined the Administration's efforts to tackle the heroin epidemic from various angles including criminal enforcement, prevention, and substance use disorder treatment and recovery services, and it developed a set of recommendations to "curtail the escalating overdose epidemic and death rates."93 The report's recommendations target the public safety and public health aspects of the opioid epidemic, and several specifically address countering heroin trafficking.

The task force suggested, for instance, that the federal government prioritize prosecutions of heroin distributors and enhance investigation and prosecution techniques to target the heroin supply chain—particularly when the drug caused a death. The report noted that identifying the source of particularly potent heroin and cutting off the flow of heroin from the source may ultimately save lives. It also noted that prominent prosecutions of distributors and traffickers can help serve as a deterrent to other potential drug dealers.94

The task force also recommended using coordinated, real time data sharing to disrupt drug supply and to focus prevention, treatment, and intervention resources on the areas that need them most. It highlights the HIDTA program and the OCDETF program as examples of task forces that can be leveraged for information sharing purposes;95 while these programs have information sharing capacities, it is unclear how rapidly this sharing could be executed to fulfill the task force's recommendation of striving for "real time" information sharing.