This report contains two main parts: a section describing recent events and a longer background section on key elements of the U.S.-Japan relationship.

Recent Developments

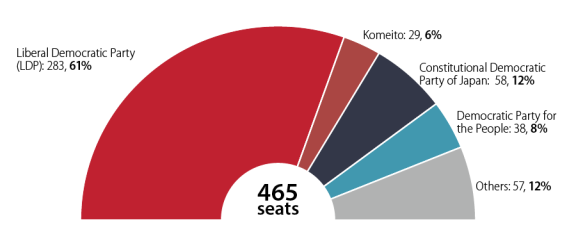

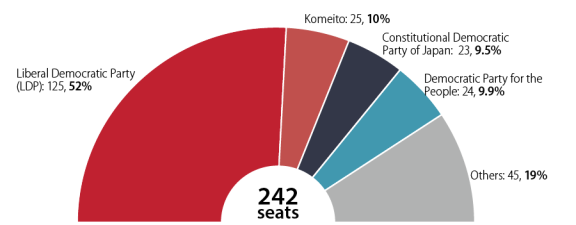

Abe Secures Another Term, Could be Premier Until 2021

Shinzo Abe has been Japan's prime minister since December 2012, and in 2017 he succeeded in extending the LDP's term-limit rules for party president from two consecutive three-year terms to three consecutive terms. In September 2018, Abe's Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) held an internal party leadership vote in which Abe defeated former Defense Minister Shigeru Ishiba, securing a three-year term as party president. With the LDP and its coalition partner, the much smaller Komeito party, firmly in control of Japan's legislature, Abe's victory in the LDP leadership contest means that he will continue serving as premier. If Abe remains in power beyond November 2019, he will become the longest-serving prime minister in the history of modern Japan.1

Shortly after his victory, Abe appointed a new Cabinet, retaining the members in charge of foreign affairs and U.S. relations, a likely indication of continuity in Japanese foreign and trade policy. Abe's new Cabinet includes one woman, down from two, despite Abe's campaign to increase women's representation in government and participation in the workforce. (See "Emphasis on "Womenomics"'" section below.)

Abe's next electoral test will come in July 2019, when half the seats of Japan's Upper House of the bicameral legislature (called the Diet) will be chosen. In a reflection of the disarray of Japan's opposition parties, the LDP's approval ratings in most early October 2018 polls were between 40% and 50%, while none of Japan's other parties received more than 10% support. The September 2018 LDP vote exposed a gap between the LDP's Diet members, over 80% of whom voted for Abe, and the LDP's rank-and-file members, over 55% of whom voted for Abe's opponent, Ishiba. (For background on Japanese politics, see the "Japanese Politics" section.)

Cracks Emerge on North Korean Policy

At the outset of the Trump presidency, a shared approach to confronting the North Korean threat appeared to cement the U.S.-Japan relationship. Beginning at their first summit in Mar-a-Lago in February 2017, Abe and Trump presented a united front on dealing with Pyongyang's nuclear weapon test and multiple missile launches. The two leaders met multiple times and spoke often by phone, and Abe wholeheartedly endorsed the Trump Administration's "maximum pressure" strategy.

Since the beginning of 2018, Trump has pursued a rapprochement with Pyongyang and held a friendly summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. Many Japanese are unconvinced that North Korea will give up its nuclear weapons or missiles and fear that Tokyo's interests vis-à-vis Pyongyang will be marginalized if U.S.-North Korea relations continue to warm. Chief among those issues are the abduction of Japanese citizens by North Korean agents in the 1970s and 1980s, an issue on which Abe built his political career. Abe has said he would be willing to meet with Kim to resolve the abduction issue but analysts doubt that Kim has reason to conciliate Abe given his newfound stature in international diplomacy.

Trump's shift on North Korea—including his decision to suspend U.S.-South Korean military exercises to obtain greater concessions from Pyongyang—and his statements critical of the value of alliances generally and Japan specifically have increased questions among Japanese policymakers about the depth and durability of the U.S. commitment to Japan's security.

Trade Tensions High as New Bilateral Talks Announced

U.S. trade policy under the Trump Administration has focused partly on reducing U.S. bilateral trade deficits. This has strained U.S. trade relations with Japan, which accounted for $70 billion or 9% of the total U.S. goods trade deficit in 2017, with a deficit in auto trade alone of over $50 billion. As part of its focus on reducing the trade deficit and encouraging domestic manufacturing, among other rationales, the Administration has proclaimed increased tariffs and other import restrictions under rarely used U.S. trade laws.2 In addition to raising concerns over potential economic costs in the United States, these tariff actions have heightened tensions with U.S. trading partners. Japan, given its longstanding close alliance with the United States, has taken particular issue with the steel and aluminum tariffs imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Act of 1962, which are based on an investigation into the potential threat to national security posed by the imports. An ongoing Section 232 investigation on motor vehicles may pose a larger threat to the Japanese economy. U.S. imports of Japanese autos and parts were nearly $56 billion, about one-third of total U.S. imports from Japan in 2017.3

On September 26, 2018, the United States and Japan announced their intent to start new formal bilateral trade negotiations.4 On October 16, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) gave Congress official notification to that effect, allowing negotiations to start under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) procedures after 90 days.5 Japan was reluctant to agree to such negotiations, but likely saw the talks as a way to avoid the possible increased U.S. motor vehicle tariffs.6 As it did in talks with the EU, the Trump Administration has agreed not to impose new tariffs while bilateral negotiations remain ongoing. The agreement may be negotiated in stages and be less comprehensive than a typical U.S. free trade agreement (FTA), though the scope of talks is unclear. Instead of bilateral talks, Japan had urged the Trump Administration to return to the regional Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). After the U.S. withdrawal from TPP in 2017, Japan took the lead in negotiating revisions to the agreement among the remaining 11 members, suspending certain commitments largely sought by the United States. The new deal, called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) or TPP-11, was signed in July 2018 and requires ratification by six participants to take effect.7 Australia, Japan, Mexico, and Singapore have ratified the agreement to date, and Canada's parliament is in the final stages of ratification.

China and Japan Look to Stabilize Relations

Despite an ongoing territorial dispute in the East China Sea, Japan and China appear to be seeking stability in their bilateral relationship, a trend that has accelerated in the past several months. Abe is scheduled to visit Beijing in late October, the first dedicated leaders' summit between the two countries since 2011. On the agenda is deepening economic cooperation and increasing people-to-people exchanges. The emphasis on economic issues has emerged as the two sides have sought to manage tensions in the security realm. In May 2018, Tokyo and Beijing established a hotline for senior defense officials to avoid an unintended escalation in the event of a crisis over maritime disputes in the East China Sea. (See "Territorial Dispute with China in the East China Sea" for more background.) Abe's government has reversed its initial opposition to China's Belt and Road Initiative, which calls for building infrastructure projects in various regions around the world, saying that under the proper conditions it will cooperate with Beijing in providing infrastructure development.8 Some analysts posit that the mutual interest in improving relations may be driven by both countries' trade friction with the United States and more general sense of uncertainty about the durability of U.S. presence in the region. Although deep-seated historical distrust and regional rivalry are likely to endure in the long-run, relations appear to be on the upswing.

Japan's Uneasy Relations with South Korea

Japan's relations with South Korea remain precarious despite a rapprochement in 2016. Koreans hold strong grievances about Japan's colonial rule over the peninsula (1910-1945), particularly on the issue of Korean comfort women who were forced to provide sex to Japanese soldiers in the World War II era. (See "Japan's Ties with South Korea" section.) After South Korea's progressive president, Moon Jae-in, was elected in May 2017, Seoul said it would uphold a U.S.-supported 2015 agreement on how to resolve the comfort women issue, but public mistrust suggests that it will remain a diplomatic irritant. Moon also has continued to participate in a 2016 ROK-Japan military intelligence-sharing agreement, which the United States helped to broker, but trilateral defense cooperation has flagged.

Even when official relations are steady, historical grievances are just beneath the surface and can flare unexpectedly. In early October 2018, the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force pulled out of an international fleet review in South Korea after the hosts asked Japan to refrain from hoisting its ensign, which is identical to Japan's pre-World War II imperial "rising sun" flag. In addition, Moon has suggested that his government plans to shut down the foundation established to oversee compensating comfort women after the 2015 agreement was signed, likely in response to public opinion that is critical of the arrangement. Recently, Abe has emphasized publicly that he wants to improve ties with South Korea, possibly reflecting the central role that Seoul has taken in driving international diplomacy with North Korea.

The warming of relations between North and South Korea since early 2018 presents additional challenges to the relationship between the two U.S. allies. The North Korean threat has traditionally driven closer U.S.-Japan-South Korea trilateral coordination, and North Korea's consistent provocations in the past have provided both the motivation and the political room for South Korea and Japan to expand security cooperation. Japan is wary of Seoul's outreach to North Korea and Pyongyang's "smile diplomacy," however, particularly if it is not accompanied by significant tangible reductions in North Korean nuclear and missile capabilities.

|

|

Source: Map Resources. Adapted by CRS. |

|

Japan Country Data Population: 126,451,398 (July 2017 est.)

Source: CIA, The World Factbook, October 2018. |

Japan's Foreign Policy and U.S.-Japan Relations

U.S.-Japan Relations in the Trump Presidency

Although candidate Donald Trump made statements critical of Japan during his campaign, relations have remained strong on the surface throughout several visits and leaders' meetings. After Trump's victory, Abe was the first foreign leader to visit the President-Elect, and the second leader to visit the White House after the U.S. inauguration. Abe and Trump displayed a strong personal rapport and issued a joint statement that echoed many of the previous tenets of the bilateral alliance. However, Trump's long-standing wariness of Japan's trade practices and skepticism of the value of U.S. alliances abroad may have unnerved Tokyo. With Abe's political position ensured, he has looked to hedge against Japan's strong dependency on the United States by championing regional trade deals, stabilizing relations with China, and reaching out to other partners such as Russia, India, Australia, and the European Union.

Japan remains committed to the alliance with the United States, and security cooperation at the working level continues to be robust. In some ways, U.S. pressure to provide more in the security realm may boost Abe's efforts aimed at increasing the flexibility and capabilities of Japan's military. The Japanese public remains somewhat wary of moving away from a strictly self-defense armed force, as well as of altering Japan's constitution to allow for more offensive capabilities.

As a baseline, the Trump Administration has reaffirmed several key statements seen as crucial to Japan. Tokyo was likely reassured by the joint statement from the leaders' first summit, in February 2017. The United States provided a three-fold affirmation on the Senkaku Islands (the small islands are also claimed by China and Taiwan, and known as Diaoyu and Diaoyutai, respectively): recognizing Japanese administration of the islands, stating that Article 5 of the mutual defense treaty applies to the islands, and stating that it opposed "any unilateral action that seeks to undermine" Japan's administration of the islands. The Secretaries of State and Defense further affirmed the United States' "steadfast commitment" to Japan, and President Trump called the alliance "the cornerstone of peace and stability in the Pacific region."

Some analysts have expressed concern about the differences in approach to global issues between the Trump Administration and Tokyo. Internationally, the two countries traditionally have cooperated on scores of multilateral issues, from nuclear nonproliferation to climate change to pandemics. Japan is a firm supporter of the United Nations as a forum for dealing with international disputes and concerns. In the past Japan and the United States have worked closely in fora such as the East Asia Summit and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum. The shared sense of working together to forge a rules- and norms-based international order has long been a key component of the bilateral relationship.

The Trump Administration, however, has expressed skepticism of multilateral organizations. To cite one example, several Japanese cabinet members expressed disappointment in the Trump Administration's decision to withdraw from the Paris climate accord.9 Additionally, under the President's "America First" approach, a shift away from the United States' role as the guarantor of regional stability raises broader questions for Japan and other countries in the region about the durability of the alliance.10 If Japan perceives the United States is moving away from its traditional security role, many experts believe Japan may decide to form other partnerships with like-minded countries and adjust its foreign policy to allow more flexibility to independently pursue its own national interests.

|

Donald Trump Statements on Japan as a Presidential Candidate "But right now we're protecting, we're basically protecting Japan, and we are, every time North Korea raises its head, you know, we get calls from Japan and we get calls from everybody else, and 'Do something.' And there'll be a point at which we're just not going to be able to do it anymore. Now, does that mean nuclear? It could mean nuclear.... And, would I rather have North Korea have them with Japan sitting there having them also? You may very well be better off if that's the case." "... if we are attacked, [the Japanese] don't have to do anything. If they're attacked, we have to go out with full force.... That's a pretty one-sided agreement, right there.... And that is a, that's a real problem." —Statements made to the New York Times in interview on March 26, 2016 "So, North Korea has nukes. Japan has a problem with that. I mean, they have a big problem with that. Maybe they would in fact be better off if they defend themselves from North Korea.... Including with nukes, yes, including with nukes." —Statement made in interview with Chris Wallace, Fox News, April 2016 [CNN's Wolf Blitzer: "You're ready to let Japan and South Korea become nuclear powers?"] Trump: "I am prepared to, if they're not going to take care of us properly, we cannot afford to be the military and police for the world." —Statement made in interview with Wolf Blitzer on CNN, May 2, 2016 "Our allies must contribute toward the financial, political and human costs of our tremendous security burden. But many of them are simply not doing so.... We have spent trillions of dollars over time—on planes, missiles, ships, equipment—building up our military to provide a strong defense for Europe and Asia. The countries we are defending must pay for the cost of this defense—and, if not, the U.S. must be prepared to let these countries defend themselves. —Prepared speech remarks on April 27, 2016 |

Abe's Leadership

If Abe remains in office through November 2019, as expected, he will become the longest-serving prime minister in post-war Japan. After his first stint as premier in 2006-2007, Abe led the conservative LDP back into power in late 2012 following a six-year period in which six different prime ministers served. Since then, he appears to have stabilized Japanese politics and emphasized strong defense ties with the United States. Under Abe's leadership, the government increased the defense budget after a decade of decline, passed a set of controversial bills that are reforming Japanese security policies, and won approval from a previous Okinawan governor for the construction of a new U.S. Marine Corps base on Okinawa. Abe also led Japan into the TPP FTA negotiations and has attempted to revitalize Japan's economy, including seeking a number of economic reforms favored by many in the United States.

Abe and Historical Issues

Historical issues have long colored Japan's relationships with its neighbors, particularly China and South Korea, which argue that the Japanese government has neither sufficiently "atoned" for nor adequately compensated them for Japan's occupation and belligerence in the first half of the 20th century. Abe's selections for his cabinet posts over the years include a number of politicians known for advocating nationalist, and in some cases ultra-nationalist, views that many argue appear to glorify Imperial Japan's actions. Some of Abe's positions—such as changing the interpretation of Japan's constitution to allow for Japanese participation in collective self-defense—largely have been welcomed by U.S. officials eager to advance military cooperation. Other statements, however, suggest that Abe embraces a revisionist view of Japanese history that rejects the narrative of Imperial Japanese aggression and victimization of other Asians. He has been associated with groups arguing that Japan has been unjustly criticized for its behavior as a colonial and wartime power. Among the positions advocated by these groups, such as Nippon Kaigi Kyokai, are that Japan should be applauded for liberating much of East Asia from Western colonial powers, that the 1946-1948 Tokyo War Crimes tribunals were illegitimate, and that the killings by Imperial Japanese troops during the 1937 "Nanjing massacre" were exaggerated or fabricated.11

In December 2013, Abe paid a highly publicized visit to Yasukuni Shrine, a shrine that was established to house the "spirits" of Japanese soldiers who died during war, but also includes 14 individuals who were convicted as Class A war criminals after World War II.12 The U.S. Embassy in Tokyo directly criticized the move, releasing a statement that said, "The United States is disappointed that Japan's leadership has taken an action that will exacerbate tensions with Japan's neighbors."13 Since then, despite the U.S. statement, sizeable numbers of LDP lawmakers have periodically visited the Shrine on ceremonial days, including the sensitive date of August 15, the anniversary of Japan's surrender in World War II. Abe has refrained from visiting since 2013, although LDP lawmakers and cabinet ministers have periodically paid respects at the shrine.14

Since 2013, Abe himself has largely avoided language and actions that could upset regional relations. After some waffling on key government statements made by past Japanese leaders—chief among them the 1995 "Murayama Statement" that apologized for Japan's wartime action and the 1993 "Kono Statement" that apologized to the "comfort women" (see the "Japan and the Korean Peninsula" section below)—Abe reaffirmed the official government expressions of remorse after pressure from many forces, including U.S. government officials and Members of Congress. Abe appears to have responded to criticism that his handling of these controversial issues could be damaging to Japan's and—to some extent—the United States' national interests.

Territorial Dispute with China in the East China Sea

Japan and China have engaged in a diplomatic and at times physical struggle over a group of uninhabited land features in the East China Sea known as the Senkaku Islands in Japan, Diaoyu in China, and Diaoyutai in Taiwan. The territory, administered by Japan but also claimed by China and Taiwan, has been a subject of contention for years, despite modest attempts by Tokyo and Beijing to jointly develop the potentially rich energy deposits nearby, most recently in 2008-2010. China and Japan also dispute maritime rights in the East China Sea more broadly, with Japan arguing for a "median line" equidistant from each country's claimed territorial border dividing the two countries' exclusive economic zones in the East China Sea; China rejects Japan's claimed median line, arguing it has maritime rights beyond this line.15

The Senkakus dispute has been in a state of varying tension since 2010, when the Japan Coast Guard arrested and detained the captain of a Chinese fishing vessel after it collided with two Japan Coast Guard ships near the Senkakus. The incident resulted in a diplomatic standoff, with Beijing suspending high-level exchanges and restricting exports of rare earth elements to Japan.16 In August 2012, the Japanese government purchased three of the five land features from a private landowner in order to preempt their sale to Tokyo's nationalist governor at the time, Shintaro Ishihara.17 Claiming that this act amounted to "nationalization" and thus violated the tenuous status quo, Beijing issued sharp objections. Chinese citizens held massive anti-Japan protests, and the resulting tensions led to a drop in Sino-Japanese trade. In April 2013, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said for the first time that China considered the islands a "core interest," indicating to many analysts that Beijing was unlikely to make concessions on this sensitive sovereignty issue.

Starting in the fall of 2012, China began regularly deploying maritime law enforcement ships near the islands and stepped up what it called "routine" patrols to assert jurisdiction in "China's territorial waters."18 In 2013, near-daily encounters occasionally escalated: both countries scrambled fighter jets, and, according to the Japanese government, a Chinese navy ship locked its fire-control radar on a Japanese destroyer and helicopter on two separate occasions. The number of Chinese vessels entering the territorial seas19 surrounding the islands decreased to a steady level of 7-10 vessels per month in 2014 and 2015, spiked to over 20 in August of 2016, before shifting to the 8-12 vessels per month range for most of the January-August 2017 period and decreasing again to 6-8 vessels per month in the first eight months of 2018.20 Most of these patrols are conducted by the China Coast Guard, which has been instrumental in advancing China's interests in disputed waters in the East and South China Seas.21 In 2016, for example, several China Coast Guard vessels escorted between 200 and 300 Chinese fishing vessels to waters near the Senkakus in an apparent demonstration of Chinese sovereignty. 22

China-Japan tensions have played out in the airspace above and around the Senkakus as well. Chinese aircraft activity in the area contributed to an eightfold increase in the number of scramble takeoffs by Japan Air Self Defense Force aircraft between Fiscal Year 2010 (96 scrambles) and 2016 (842 scrambles); the number of scrambles decreased somewhat to 602 in 2017, and there were 278 in the first half of 2018.23 In November 2013, China abruptly established an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea covering the Senkakus as well as airspace that overlaps with the existing ADIZs of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. China's announcement of the ADIZ produced indignation and anxiety in the region and in Washington for several reasons: the ADIZ represented a new step to pressure—to coerce, some experts argue—Japan's conciliation in the territorial dispute over the islets; the requirements for flight notification in China's proclaimed ADIZ go beyond international norms and impinge on the freedom of navigation; and the overlap of ADIZs could lead to accidents or unintended clashes, thus raising the risk of conflict in the East China Sea.

Tensions have subsided somewhat after peaking in 2016, with Beijing and Tokyo seemingly committed to preventing a crisis or armed clash over the Senkakus. For example, in May 2018, China and Japan announced the establishment of a "hotline" for senior defense officials from both countries to communicate and deescalate in the event of a maritime clash.24 In addition, Chinese authorities in August 2018 reportedly banned Chinese fishermen from operating near the Senkakus.25 Efforts by both countries to defend their claims have played out primarily in the "gray zone," or the ambiguous space between peace and conflict, with non-military actors like coast guards, fishermen, and China's maritime militia on the front lines. China's approach to the dispute (as well as its disputes in the South China Sea) appears to be aimed at exploiting the gray zone to gradually consolidate its control and influence over contested space without escalating to armed conflict. 26 In response, Japan has prioritized enhancing its ability to counter gray zone activities, in addition to strengthening its traditional military capabilities.27

Japan's administration of the Senkakus is the basis of the U.S. treaty commitment to defend that territory. U.S. administrations going back at least to the Nixon Administration have stated that the United States takes no position on the territorial disputes. However, it also has been U.S. policy since 1972 that the 1960 U.S.-Japan Security Treaty covers the Senkakus, because Article 5 of the treaty stipulates that the United States is bound to protect "the territories under the Administration of Japan," and Japan administers the Senkakus.28 In its own attempt to address this perceived gap, Congress inserted in the FY2013 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4310, P.L. 112-239) a resolution stating, among other items, that "the unilateral action of a third party will not affect the United States' acknowledgment of the administration of Japan over the Senkaku Islands."29

The conflict in the East China Sea in many ways embodies Japan's security challenges. The maritime confrontation with Beijing is a concrete manifestation of the threat Japan has faced for years from China's rising regional power. It also brings into relief Japan's dependence on the U.S. security guarantee and its anxiety that Washington will not defend Japanese territory if Japan goes to war with China, particularly over a group of uninhabited land features.

In contrast to Japan's and China's inability to reach an agreement on sharing undersea resources in the disputed area, in April 2013 Japan and Taiwan agreed to jointly share and administer the fishing resources in their overlapping claimed EEZs Senkakus (Diaoyu/Diaoyutai). The agreement, which had been discussed for 17 years, addressed neither the two sides' conflicting sovereignty claims, nor the question of fishing rights in the islands' territorial waters. On July 29, 2013, the Senate passed S.Res. 167, which described the pact as a "model for other such agreements."

Japan and the Korean Peninsula

Japan's Ties with South Korea

In the 21st century, Japan's relationship with South Korea has fluctuated between troubled and tentatively cooperative, depending on external circumstances and the leaders in power.30 Washington has generally encouraged closer ties between Tokyo and Seoul as two of its most important alliance partners; the two countries have shared security concerns, developed economies, and a commitment to open markets, international rules and norms, and regional stability. A poor relationship between Seoul and Tokyo jeopardizes U.S. interests by complicating trilateral cooperation on North Korea policy and on responding to China's rise. Tense relations also complicate Japan's desire to expand its military and diplomatic influence as well as the potential creation of an integrated U.S.-Japan-South Korea ballistic missile defense system.

The North Korean threat has traditionally driven closer trilateral coordination, even when Tokyo and Seoul have faced political tension. Under North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, North Korea's consistent provocations from 2011 to 2017 provided both the motivation and the political room for South Korea and Japan to forge more cooperative stances, despite lingering mutual distrust. For example, in late June 2016, the three countries held their first joint military training exercise with Aegis ships that focused on tracking North Korean missile launches by sharing intelligence.

The persistent Japan-Korea discord centers on historical issues. Officials in Japan have referred to rising "Korea fatigue" among their public and expressed frustration that for years South Korean leaders have not recognized and in some cases have rejected the efforts Japan has made to acknowledge and apologize for Imperial Japan's actions during the 35 years following its annexation of the Korean Peninsula in 1910. In addition to the comfort women issue (see below), the perennial issues of how Japan's behavior before and during World War II is depicted in Japanese school textbooks and a territorial dispute between Japan and South Korea continue to periodically rile relations. A group of small islands in the Sea of Japan, known as Dokdo in Korean and Takeshima in Japanese (the U.S. government refers to them as the Liancourt Rocks), are administered by South Korea but claimed by Japan. Japanese statements about the claim in defense documents or by local prefectures routinely spark official criticism and public outcry in South Korea. Similarly, Seoul expresses disapproval of some of the history textbooks approved by Japan's Ministry of Education that South Koreans claim diminish or whitewash Japan's colonial-era atrocities.

Comfort Women Issue

The most prominent stumbling block to better Japan-South Korean relations involves the "comfort women," a literal translation of the Japanese euphemism referring to women who were forced to provide sexual services for Japanese soldiers during the imperial military's conquest and colonization of several Asian countries in the 1930s and 1940s. The long-standing controversy became more heated under Abe's leadership. In the past, Abe supported the claims made by many conservatives in Japan that the women were not directly coerced into service by the Japanese military.

In 2015, Abe and then-President Park Geun-hye of South Korea concluded an agreement that included a new apology from Abe and the provision of 1 billion yen (about $8.3 million) from the Japanese government to a new Korean foundation that supports surviving victims.31 The two governments' foreign ministers agreed that this long-standing bilateral rift would be "finally and irreversibly resolved" pending the Japanese government's implementation of the agreement.32 Although the main elements of the agreement appeared to be implemented in 2016, the deal remains deeply unpopular with the South Korea public. The issue continues to be an irritant in bilateral relations: Japan objects to a comfort woman statue that stands in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, and in 2018 Seoul suggested it would disband the foundation established by the agreement.

The issue of the so-called comfort women has gained visibility in the United States, due in part to Korean-American activist groups. These groups have pressed successfully for the erection of monuments in California and New Jersey commemorating the victims, passage of a resolution on the issue by the New York State Senate, the naming of a city street in the New York City borough of Queens in honor of the victims, and approval to erect a memorial to the comfort women in San Francisco. In 2007, U.S. House of Representatives passed H.Res. 121 (110th Congress), calling on the Japanese government to "formally acknowledge, apologize, and accept historical responsibility in ... an unequivocal manner" for forcing young women into military prostitution.

Japan's North Korea Policy

Since 2009, Washington and Tokyo have been largely united in their approach to North Korea, driven by Pyongyang's string of missile launches and nuclear tests. In February 2017, North Korea launched the first of many missiles of that year during Abe's summit with Trump, setting the stage for the two leaders to bond over the North Korean threat. Japan has employed a hardline policy toward North Korea, including a virtual embargo on all bilateral trade and vocal leadership at the United Nations to punish Pyongyang for its human rights abuses and military provocations. When the Six-Party Talks were active, Japan was considered a key actor in a possible resolution of problems on the Korean peninsula, but the multilateral format has been dormant since 2009 and appears to be all but abandoned.

Japan is directly threatened by North Korea given the demonstrated capability of Pyongyang's medium-range missiles; in 2017, North Korea twice tested missiles that flew over Japanese territory. North Korea has long-standing animosity toward Japan for its colonialism of the Korean peninsula in the early 20th century. In addition, U.S. bases in Japan could be targeted by the North Koreans in any military contingency. Aside from these direct security concerns, Japan has prioritized the long-standing issue of Japanese citizens kidnapped by North Korean agents decades ago. In 2002, then-North Korean leader Kim Jong-il admitted to the abductions and returned five survivors, claiming the others had perished from natural causes. Japan officially identifies 17 individuals as abductees.33 Abe, then serving as Chief Cabinet Secretary to then-Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, has since been a passionate champion for the abductees' families and pledged as a leader to bring home all surviving Japanese. President Trump mentioned the abductee issue during his 2017 U.N. General Assembly address, and said that he also raised the issue with Kim Jong-un during the Singapore Summit in 2018.

Renewed Relations with India, Australia, and ASEAN

The Abe Administration's foreign policy has displayed elements of both power politics and an emphasis on democratic values, international laws, and norms. Shortly after returning to office in 2012, Abe released an article outlining his foreign and security policy strategy titled "Asia's Democratic Security Diamond," which described how the democracies of Japan, Australia, India, and the United States could cooperate to deter Chinese aggression on its maritime periphery.34 In Abe's first year in office, Japan held numerous high-level meetings with Asian countries to bolster relations and, in many cases, to enhance security ties. Abe had summit meetings in India, Russia, Great Britain, all 10 countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and several countries in the Middle East and Africa. Japan has particularly focused on issues of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, in part because of the implications for Japan's trade flows and for the East China Sea dispute. Since 2012, even before Abe came into office, Japan had been working to strengthen the maritime capabilities of Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines, and Abe has accelerated these efforts, which the Obama Administration supported as part of its "Asia Rebalance" strategy.35 This energetic diplomacy indicates a desire to balance China's growing influence with a loose coalition of Asia-Pacific powers, but this strategy of realpolitik is couched in the rhetoric of international laws and democratic values.

Abe's international outreach has yielded positive results, according to many observers. Despite a failed submarine deal, bilateral ties with Australia are robust. Abe's highly publicized July 2014 visit to Canberra yielded new economic and security arrangements, including an agreement to transfer defense equipment and technology. Japan-India ties have blossomed under Abe and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, including expanded military exercises and negotiations on defense export agreements. Even as cracks have appeared in the U.S.-Philippines alliance, Abe has made efforts to maintain Japan-Philippines defense relations.

Japan-Russia Relations

Part of Abe's international diplomacy push has been to reach out to Russia. Japan and the Soviet Union never signed a peace treaty following World War II due to a territorial dispute over four islands north of Hokkaido in the Kuril Chain. The islands are known in Japan as the Northern Territories and were seized by the Soviets in the waning days of the war. Both Japan and Russia face security challenges from China and may be seeking a partnership to counter Beijing's economic and military power. Particularly in the past several years, however, China and Russia have developed closer relations and cooperate in multiple areas. Tokyo's ambitious plans to revitalize relations with Moscow, including resolution of the disputed islands, however, do not appear to have made progress. Russia's aggression in Ukraine in 2014 disrupted the improving relationship. Tokyo signed on to the subsequent G7 statement condemning Russia's action and implemented sanctions and asset freezes. Japan attempted to salvage the potential breakthrough by imposing only relatively mild sanctions despite pressure from the United States and other Western powers. With many countries in the West isolating Moscow, Russia and China appear to have grown closer.36

U.S. World-War II-Era Prisoners of War (POWs)

For decades, U.S. soldiers who were held captive by Imperial Japan during World War II have sought official apologies from the Japanese government for their treatment. A number of Members of Congress have supported these campaigns. The brutal conditions of Japanese POW camps have been widely documented.37 In May 2009, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States attended the last convention of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor to deliver a cabinet-approved apology for their suffering and abuse. In 2010, with the support and encouragement of the Obama Administration, the Japanese government financed a Japanese/American POW Friendship Program for former American POWs and their immediate family members to visit Japan, receive an apology from the sitting Foreign Minister and other Japanese Cabinet members, and travel to the sites of their POW camps. Annual trips were held from 2010 to 2017.38

In the 112th Congress, three resolutions—S.Res. 333, H.Res. 324, and H.Res. 333—were introduced thanking the government of Japan for its apology and for arranging the visitation program.39 The resolutions also encouraged the Japanese to do more for the U.S. POWs, including by continuing and expanding the visitation programs as well as its World War II education efforts. They also called for Japanese companies to apologize for their or their predecessor firms' use of un- or inadequately compensated forced laborers during the war. In July 2015, Mitsubishi Materials Corporation (a member of the Mitsubishi Group) became the first major Japanese company to apologize to U.S. POWs on behalf of its predecessor firm, which ran several POW camps that included over 1,000 Americans.40 In addition, they made a one-time grant of $50,000 to a library in West Virginia to maintain a collection of POW materials.

Energy and Environmental Issues

Under the Obama Administration, Japan and the United States cooperated on a wide range of environmental initiatives both bilaterally through multiple agencies and through multilateral organizations, such as the UNFCCC, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Clean Energy Ministerial (CEM), the International Energy Forum (IEF), and the East Asian Summit (EAS). Japan was generally regarded by U.S. officials as closely aligned with the Obama Administration in international climate negotiations in its position that any international climate agreement must be legally binding in a symmetrical way, with all major economies agreeing to the same elements. However, because of the shutdown of Japan's nuclear reactors (see below), international observers raised concerns about losing Japan as a global partner in promoting nuclear safety and nonproliferation measures and in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.41

President Trump's 2017 decision to withdraw the United States from the UNFCCC Paris Agreement, an international climate accord designed to reduce global emissions, removed one channel through which the United States and Japan cooperated closely. Japanese officials expressed dismay when the United States withdrew from the Agreement, with the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs calling the decision "regrettable"; the then Minister for the Environment had a stronger response, saying, "It's as if they've turned their back on the wisdom of humanity…. In addition to being disappointed, I'm also angry."42 Although Japanese officials—including Abe—emphasize the importance of acting on climate change both domestically and in coordination with the international community, some experts assess Japan's greenhouse gas emissions reduction plan is insufficiently ambitious, particularly in light of Japan's expansion of coal power plants.43

Nevertheless the two countries continue to cooperate on energy issues under a Japan-United States Strategic Energy Partnership established in November 2017. The partnership focuses on advanced nuclear energy technologies, clean coal technologies, natural gas market development, and energy infrastructure in the developing world.44 This effort dovetails with the Trump Administration's Asia-EDGE (Enhancing Development and Growth through Energy) initiative, one of the economic and commercial pillars of the Administration's Indo-Pacific strategy announced in July 2018. Among other things, Asia-EDGE aims to strengthen energy security in the region and grow Asian markets for U.S. energy products, particularly liquefied natural gas (LNG);45 Japan is the world's largest LNG buyer and has become a destination for U.S. LNG exports.46

|

March 2011 "Triple Disaster" On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake jolted a wide swath of Honshu, Japan's largest island. The quake, with an epicenter located about 230 miles northeast of Tokyo, generated a tsunami that pounded Honshu's northeastern coast, causing widespread destruction in Miyagi, Iwate, Ibaraki, and Fukushima prefectures. Some 20,000 lives were lost, and entire towns were washed away; over 500,000 homes and other buildings and around 3,600 roads were damaged or destroyed. Up to half a million Japanese were displaced. Damage to several reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant complex led the government to declare a state of emergency and evacuate nearly 80,000 residents within a 20-kilometer radius due to dangerous radiation levels. In many respects, Japan's response to the multifaceted disaster was remarkable. Over 100,000 troops from the Self Defense Forces (SDF), Japan's military, were deployed quickly to the region. After rescuing nearly 20,000 individuals in the first week, the troops turned to a humanitarian relief mission in the displaced communities. Construction of temporary housing began a week after the quake. Foreign commentators marveled at Japanese citizens' calm resilience, the lack of looting, and the orderly response to the strongest earthquake in the nation's modern history. Japan's preparedness—strict building codes, a tsunami warning system that alerted many to seek higher ground, and years of public drills—likely saved tens of thousands of lives. Appreciation for the U.S.-Japan alliance surged after the two militaries worked effectively together to respond to the earthquake and tsunami. Years of joint training and many interoperable assets facilitated the integrated alliance effort. "Operation Tomodachi," using the Japanese word for "friend," was the first time that SDF helicopters used U.S. aircraft carriers to respond to a crisis. The USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier provided a platform for air operations as well as a refueling base for Japanese SDF and Coast Guard helicopters. Other U.S. vessels transported SDF troops and equipment to the disaster-stricken areas. For the first time, U.S. military units operated under Japanese command in actual operations. Despite this response to the initial event, the uncertainty surrounding the nuclear reactor meltdowns and the failure to present longer-term reconstruction plans led many to question the government's handling of the disasters. As reports mounted about heightened levels of radiation in the air, tap water, and produce, criticism emerged regarding the lack of clear guidance from political leadership. Concerns about the government's excessive dependence on information from Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the firm that owns and operates the power plant, amplified public skepticism and elevated criticism about conflicts of interest between regulators and utilities. |

Nuclear Energy Policy

Japan is undergoing a national debate on the future of nuclear power, with major implications for businesses operating in Japan, U.S.-Japan nuclear energy cooperation, and nuclear safety and nonproliferation measures worldwide. Prior to 2011, nuclear power was providing roughly 30% of Japan's power generation capacity, and the 2006 "New National Energy Strategy" had set out a goal of significantly increasing Japan's nuclear power generating capacity. However, the policy of expanding nuclear power was abruptly reversed in the aftermath of the March 11, 2011, natural disasters and meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Public trust in the safety of nuclear power collapsed, and a vocal antinuclear political movement emerged. This movement tapped into an undercurrent of antinuclear sentiment in modern Japanese society based on its legacy as the victim of atomic bombing in 1945. As the nation's 54 nuclear reactors were shut down one by one for their annual safety inspections in the months after March 2011, the Japanese government did not restart them for several years (except a temporary reactivation for two reactors at one site in central Japan). No reactors were operating from September 2013 until August 2015. As of October 2018, only eight reactors are in operation.47

The drawdown of nuclear power generation resulted in many short- and long-term consequences for Japan: rising electricity costs for residences and businesses; heightened risk of blackouts in the summer, especially in the Kansai region near Osaka and Kyoto; widespread energy conservation efforts by businesses, government agencies, and ordinary citizens; significant losses for and near-bankruptcy of major utility companies; and increased fossil fuel imports. Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry estimated the direct cost of the decommissioning of the Fukushima Daiichi plant and compensation of victims to be $187 billion, and the cost of fossil fuel imports to replace power from subsequently shutdown reactors to be $31.3 billion in FY2013 alone.48 The Institute of Energy Economics, Japan, calculated that the nuclear shutdowns led to the loss of 420,000 jobs in 2012.49

The LDP has promoted a relatively pronuclear policy, despite persistent antinuclear sentiment among the public. The Abe Administration released a Strategic Energy Plan in April 2014 that identifies nuclear power as an "important base-load power source," and in 2015 announced it would seek for nuclear energy to account for 20-22% of Japan's power supply by 2030. In the coming years, the government likely will approve the restart of many of Japan's existing 42 operable nuclear reactors, but as many as half, or even more, may never operate again. Approximately 55% of the Japanese public opposes the restart of nuclear reactors, compared to approximately 25% in favor.50 The Abe Cabinet faces a complex challenge: how to balance concerns about energy security, promotion of renewable energy sources, the viability of electric utility companies, the health of the overall economy, and public concerns about safety. And if Japan closes down its nuclear power industry, some analysts wonder whether it will continue to play a lead role in promoting nuclear safety and nonproliferation around the world.

Alliance Issues

The U.S.-Japan alliance has long been an anchor of the U.S. security role in Asia. Forged in the U.S. occupation of Japan after its defeat in World War II, the alliance provides a platform for U.S. military readiness in the Pacific under the 1960 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan. About 50,000 U.S. troops are stationed in Japan and have the exclusive use of approximately 90 facilities (see Figure 2). In exchange, the United States guarantees Japan's security, including through extended deterrence, known colloquially as the U.S. "nuclear umbrella." The U.S.-Japan alliance, which many believe was missing a strategic rationale after the end of the Cold War, may have found a new guiding rationale in shaping the environment for China's rise. In addition to serving as a hub for forward-deployed U.S. forces, Japan provides its own advanced military assets, many of which complement U.S. assets.51

During the 2016 presidential campaign, candidate Trump repeatedly asserted that Tokyo did not pay enough to ease the U.S. cost of providing security for Japan. In response, Japanese and U.S. officials have defended the system of host nation support that has been negotiated and renegotiated over the years. Defenders of the alliance point to the strategic benefits as well as the cost saving of basing some of the most advanced capabilities of the U.S. military in Japan, including a forward-deployed aircraft carrier. The question of how much Japan spends, particularly when including the Japanese government's payments to compensate base-hosting communities and to shoulder the costs of U.S. troop relocation in the region, remains a thorny area with few easily quantifiable answers. Japan appears to anticipate new demands from the United States, and Abe has already stated that Japan will no longer cap its defense spending at the customary 1% of GDP.

Since the early 2000s, the United States and Japan have taken strides to improve the operational capability of the alliance as a combined force, despite political and legal constraints. Japan's own defense policy has continued to evolve, and its major strategic documents reflect a new attention to operational readiness and flexibility. The original, asymmetric arrangement of the alliance has moved toward a more balanced security partnership in the 21st century, and Japan's 2014 decision to engage in collective self-defense may accelerate that trend. Unlike 25 years ago, the Japan Self-Defense Force (SDF) is now active in overseas missions, including efforts in the 2000s to support U.S.-led coalition operations in Afghanistan and the reconstruction of Iraq. Japanese military contributions to global operations like counter-piracy patrols relieve some of the burden on the U.S. military to manage security challenges. Due to the colocation of U.S. and Japanese command facilities in recent years, coordination and communication have become more integrated. The joint response to the March 2011 tsunami and earthquake in Japan demonstrated the interoperability of the two militaries. The United States and Japan have been steadily enhancing bilateral cooperation in many other aspects of the alliance, such as ballistic missile defense, cybersecurity, and military use of space. Alongside these improvements, Japan continues to pay nearly $2 billion per year to defray the cost of stationing U.S. forces in Japan. (See "Burden-Sharing Issues" section below.)

|

|

Source: Map Resources. Adapted by CRS. Notes: MCAS is the abbreviation for Marine Corps Air Station. NAF is Naval Air Facility. |

Revised Mutual Defense Guidelines

In late April 2015, the United States and Japan announced the completion of the revision of their bilateral defense guidelines, a process that began in late 2013. First codified in 1978 and later updated in 1997, the guidelines outline how the U.S. and Japanese militaries will interact in peacetime and in war as the basic framework for defense cooperation based on a division of labor. The new guidelines account for developments in military technology, improvements in interoperability of the U.S. and Japanese militaries, and the complex nature of security threats in the 21st century. For example, the revision addresses bilateral cooperation on cybersecurity, the use of space for defense purposes, and ballistic missile defense, none of which were mentioned in the 1997 guidelines. The 2015 guidelines lay out a framework for bilateral, whole-of-government cooperation in defending Japan's outlying islands. They also significantly expand the scope of U.S.-Japan security cooperation to include defense of sea lanes and, potentially, Japanese contributions to U.S. military operations outside East Asia. The Abe Administration pushed through controversial legislation in fall 2015 to provide a legal basis for these far-reaching defense reforms, despite vocal opposition from opposition parties and the Japanese public. Japan's implementation of the new guidelines and related defense reforms has been slow and incremental, perhaps because of the controversy that surrounded passage of the new security legislation.

The bilateral defense guidelines also seek to improve alliance coordination. The guidelines establish a new standing Alliance Coordination Mechanism (ACM), which will involve participants from all the relevant agencies in the U.S. and Japanese governments, as the main body for coordinating a bilateral response to any contingency. This new mechanism removes obstacles that had inhibited alliance coordination in the past. The previous ACM only would have assembled if there was a state of war, meaning that there was no formal organization to coordinate military activities in peacetime, such as during the disaster relief response to the March 2011 disasters in northeast Japan. The U.S. and Japanese governments have convened the ACM to coordinate responses to North Korea's January 2016 nuclear weapon test, the earthquakes near Kumamoto, on Japan's western island of Kyushu in April 2016, and other episodes affecting East Asian regional security.

Collective Self-Defense

Perhaps the most symbolically significant—and controversial—security reform of the Abe Administration has been Japan's potential participation in collective self-defense. Dating back to his first term in 2006-2007, Abe has shown a determination to adjust this highly asymmetric aspect of the alliance: the inability of Japan to defend U.S. forces or territory under attack. According to the traditional Japanese government interpretation, Japan possesses the right of collective self-defense, which is the right to defend another country that has been attacked by an aggressor,52 but under Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, Japan has given up that right.53 However, Japan has interpreted Article 9 to mean that it can maintain a military for national defense purposes and, since 1991, has allowed the SDF to participate in noncombat roles overseas in a number of U.N. peacekeeping missions and in the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq.

In July 2014, the Abe Cabinet announced a new interpretation, under which collective self-defense would be constitutional as long as it met certain conditions. These conditions, developed in consultation with the LDP's dovish coalition partner Komeito and in response to cautious public sentiment, are rather restrictive and could limit significantly Japan's latitude to craft a military response to crises outside its borders. The security legislation package that the Diet passed in September 2015 provides a legal framework for new SDF missions, but institutional obstacles in Japan may inhibit full implementation in the near term. However, the removal of the blanket prohibition on collective self-defense will enable Japan to engage in more cooperative security activities, like noncombat logistical operations and defense of distant sea lanes, and to be more effective in other areas, like U.N. peacekeeping operations. For the U.S.-Japan alliance, this shift could mark a step toward a more equal and more capable defense partnership. Chinese and South Korean media, as well as some Japanese civic groups and media outlets, have been critical, implying that collective self-defense represents an aggressive, belligerent security policy for Japan.

Realignment of the U.S. Military Presence on Okinawa

Due to the legacy of the U.S. occupation and the island's key strategic location, Okinawa hosts a disproportionate share of the U.S. military presence in Japan. About 25% of all facilities used by U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ) and over half of USFJ military personnel are located in the prefecture, which comprises less than 1% of Japan's total land area. The attitudes of native Okinawans toward U.S. military bases are generally characterized as negative, reflecting a tumultuous history and complex relationships with both "mainland" Japan and with the United States. Because of these widespread concerns among Okinawans, the sustainability of the U.S. military presence in Okinawa remains a critical challenge for the alliance.54

The United States and Japan have faced decades of delay in an agreement to relocate a Marine Air Base. The new facility, slated to be built on the existing Camp Schwab in the sparsely populated Henoko area of Nago City, would replace the functions of Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Futenma, located in the center of a crowded town in southern Okinawa. The encroachment of residential areas around the Futenma base over decades has raised the risks of a fatal aircraft accident, which could create a backlash on Okinawa and threaten to disrupt the alliance. Most Okinawans oppose the construction of a new U.S. base for a mix of political, environmental, and quality-of-life reasons. A U.S. military official testified to Congress in 2016 that the expected completion of the new base at Henoko had been delayed from 2022 to 2025.

Tokyo and Okinawa agreed in March 2016 to a court-recommended mediation process, suspending construction of the Futenma replacement facility while central government and Okinawan prefectural officials resumed ultimately fruitless negotiations. A December 2016 Japanese Supreme Court decision ruled that then-Okinawa Governor Takeshi Onaga could not revoke the previous governor's landfill permit needed to build the offshore runways at Camp Schwab. Also in December 2016, the United States returned nearly 10,000 acres of land in the northern part of the island to Japan.55 Onaga passed away in August 2018, triggering a special election to replace him. Denny Tamaki, son of an Okinawan woman and U.S. Marine, won by a large margin and vowed to pursue further obstruction tactics to prevent the construction.

Burden-Sharing Issues

Calculating how much Tokyo pays to defray the cost of hosting the U.S. military presence in Japan is difficult and depends heavily on how the contributions are counted. Further, the two governments present estimations based on different data depending on the political aims of the exercise; because of the skepticism among some Japanese about paying the U.S. military, for example, the Japanese government may use different baselines in justifying its contributions to the alliance when arguing for its budget in the Diet. Other questions make it challenging to assess the value and costs of the U.S. military presence in Japan. Is the U.S. cost determined based strictly on activities that provide for the defense of Japan, in a narrow sense? Or is the system of American bases in Japan valuable because it enables the United States to more quickly, easily, and cheaply disperse U.S. power in the Western Pacific? U.S. defense officials often cite the strategic advantage of forward-deploying the most advanced American military capabilities in the Asia-Pacific at a far lower cost than stationing troops on American soil.

Determining the percentage of overall U.S. costs that Japan pays is even more complicated. According to DOD's 2004 Statistical Compendium on Allied Contributions to the Common Defense (the last year for which the report was required), Japan provided 74.5% of the U.S. stationing cost.56 In January 2017, Japan's Defense Minister provided data that set the Japanese portion of the total cost for U.S. forces stationed in Japan at over 86%.57 Other estimates from various media reports are in the 40-50% range. Most analysts concur that there is no authoritative, widely shared view on an accurate figure that captures the percentage that Japan shoulders.

Host Nation Support

One component of the Japanese contribution is the Japanese government's payment of nearly $2 billion per year to offset the cost of stationing U.S. forces in Japan. All Japanese contributions are provided in-kind. The United States spends $2.7 billion per year (on top of the Japanese contribution) on nonpersonnel costs for troops stationed in Japan.58

Japanese host nation support is composed of two funding sources: Special Measures Agreements (SMAs) and the Facilities Improvement Program (FIP). Each SMA is a bilateral agreement, generally covering five years, which obligates Japan to pay a certain amount for utility and labor costs of U.S. bases and for relocating training exercises away from populated areas. Under the current SMA, covering 2016-2020, the United States and Japan agreed to keep Japan's host nation support at roughly the same level as it had been paying in the past. Japan will contribute ¥189 billion ($1.6 billion) per year under the SMA and contribute at least ¥20.6 billion ($175 million) per year for the FIP. Depending on the yen-to-dollar exchange rate, Japan's host nation support likely will be in the range of $1.7-$2.1 billion per year.

The amount of FIP funding is not strictly defined, other than the agreed minimum, and thus the Japanese government adjusts the total at its discretion. Tokyo also decides which projects receive FIP funding, taking into account, but not necessarily deferring to, U.S. priorities.

Additional Japanese Contributions

In addition to host nation support, which offsets costs that the U.S. government would otherwise have to pay, Japan spends approximately ¥128 billion ($1.2 billion) annually on measures to subsidize or compensate base-hosting communities.59 These are not costs that would be necessarily passed on to the United States, but U.S. and Japanese alliance managers may argue that the U.S. bases would not be sustainable without these payments to areas affected by the U.S. military presence.

Based on its obligations defined in the U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty, Japan also pays the cost of relocating U.S. bases within Japan and rent to any landowners of U.S. military facilities in Japan. Japan pays for the majority of the costs associated with three of the largest international military base construction projects since World War II: the Futenma Replacement Facility in Okinawa (Japan provides $12.1 billion), construction at the Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni (Japan pays 94% of the $4.8 billion), and facilities on Guam to support the move of 4,800 marines from Okinawa (Japan pays $3.1 billion, about a third of the cost of construction).60

Japan also procures over 90% of its defense acquisitions from U.S. companies. Japan's annual U.S. Foreign Military Sales are valued at about $11 billion. Recent major acquisitions include Lockheed Martin F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, Boeing KC-46 Tankers, Northrup Grumman E2D Hawkeye airborne early warning aircraft, General Dynamics Advanced Amphibious Assault Vehicles, and Boeing/Bell MV-22 Ospreys.

Extended Deterrence

The growing concerns in Tokyo about North Korean nuclear weapons development and China's modernization of its nuclear arsenal in the 2000s garnered renewed attention to the U.S. policy of extended deterrence, commonly known as the "nuclear umbrella." The United States and Japan initiated the bilateral Extended Deterrence Dialogue in 2010, recognizing that Japanese perceptions of the credibility of U.S. extended deterrence were critical to its effectiveness.61 The dialogue is a forum for the United States to assure its ally and for both sides to exchange assessments of the strategic environment. The views of Japanese policymakers (among others) influenced the development of the 2010 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review.62 Reportedly, Tokyo discouraged a proposal to declare that the "sole purpose" of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack. Tokyo also reportedly discouraged the Obama Administration from declaring a "no first use" policy on the rationale that it would weaken deterrence against North Korea.

A lack of confidence in the U.S. security guarantee could lead Tokyo to reconsider its own status as a non-nuclear weapons state. As discussed above, as a presidential candidate Donald Trump in spring 2016 stated that he was open to Japan developing its own nuclear arsenal to counter the North Korean nuclear threat.63 Japanese leaders, however, have repeatedly rejected developing their own nuclear weapon arsenal. Analysts point to the potentially negative consequences for Japan if it were to develop its own nuclear weapons, including significant costs; reduced international standing in the campaign to denuclearize North Korea; the possible imposition of economic sanctions that would be triggered by leaving the global nonproliferation regime; and potentially encouraging South Korea to develop nuclear weapons capability. For the United States, analysts note that encouraging Japan to develop nuclear weapons could mean diminished U.S. influence in Asia, the unraveling of the U.S. alliance system, and the possibility of creating a destabilizing nuclear arms race in Asia.64

Japan also plays an active role in extended deterrence through its ballistic missile defense (BMD) capabilities. The United States and Japan have cooperated closely on BMD technology development since the earliest programs, conducting joint research projects as far back as the 1980s. Japan's purchases of U.S.-developed technologies and interceptors after 2003 give it the second-most potent BMD capability in the world. The U.S. and Japanese militaries both have ground-based BMD units deployed on Japanese territory and BMD-capable vessels operating in the waters near Japan.65 In February 2017, the joint program achieved a significant milestone in a test off of Hawaii, when a new interceptor from a guided-missile destroyer hit a medium-range missile for the first time.66

Economic Issues

U.S. trade and economic ties with Japan are viewed by many experts and policymakers as highly important to the U.S. national interest. By the most conventional method of measurement, the United States and Japan are the world's largest and third-largest economies (China is number two), accounting for nearly 30% of the world's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017. Furthermore, their economies are closely intertwined by two-way trade in goods and services, and by foreign investment.

Overview of the Bilateral Economic Relationship

Japan is a significant economic partner of the United States. Japan was the United States' fifth-largest export market for goods and services (behind Canada, Mexico, China, and the United Kingdom) and the fourth-largest source of U.S. imports (behind China, Canada, and Mexico) in 2017. Japan accounted for 5% of total U.S. exports in 2017 ($115 billion) and 6% of total U.S. imports ($171 billion).67 The United States was Japan's largest goods export market and second-largest source of goods imports (after China) in 2017.68 Japan is also a major investor in the United States accounting for more than 10% of the stock of inward U.S. direct investment in 2017 ($469 billion).

The relative significance of the bilateral economic relationship, however, has arguably declined as other countries, including China, have become increasingly important global economic actors. Over the past decade, U.S. goods exports to the world grew by nearly 20%, while exports to Japan grew by less than 2%. Similarly, U.S. goods imports from the world grew by 10% while U.S. imports from Japan fell. Some of this shift stems from structural changes in the global economic landscape, including the growth of global supply chains. U.S. import numbers probably underestimate the importance of Japan in U.S. trade since, in particular, Japanese firms export intermediate goods to China and other countries that are then used to manufacture finished goods that Chinese enterprises export to the United States.

Major economic events also have influenced U.S.-Japan trade patterns over the past decade. The global economic downturn stemming from the 2008 financial crisis had a significant impact on U.S.-Japan trade: both U.S. exports and imports declined in 2009 from 2008. Although trade flows recovered quickly, they peaked in 2012 and have declined or grown only modestly in most years since that time, as measured in U.S. dollars. (See Table 1.) The decline in the value of the Japanese yen since 2012, tied to aggressive monetary stimulus in Japan as part of "Abenomics" (described below) has likely affected both the value and quantity of trade—measured in yen. U.S. trade with Japan has largely risen over the same time period.

|

Year |

Goods Exports |

Goods Imports |

Goods Balance |

Services Exports |

Services Imports |

Services Balance |

||||||||||||

|

2005 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2006 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), International Transactions Tables. Balance of payment basis. Accessed 10/11/2018.

Under the Trump Administration, U.S. trade policy has increasingly focused on "unfair" trading practices, U.S. import competition, and bilateral trade deficits, leading to greater strain in U.S. economic relations, including with Japan. Issues of ongoing U.S. attention include concerns over market access for U.S. products such as autos and agricultural goods, and various nontariff barriers, which U.S. companies argue favor domestic Japanese products over U.S. goods and services.69 Despite this recent shift, the major trend in bilateral economic relations over the past two decades has largely been an easing of tension, in contrast with the contentious and frequent trade frictions at the fore of the bilateral relationship in the 1980s and early 1990s. A number of factors may have contributed to this trend:

- Japan's slow economic growth—beginning with the burst of the asset bubble in the 1990s—has changed the general U.S. perception of Japan from one as an economic competitor to one as a "humbled" economic power;

- significant Japanese investment in the United States including in automotive manufacturing facilities has linked production of some Japanese branded products with U.S. employment;

- the successful conclusion of the multilateral Uruguay Round agreements in 1994 led to further market openings in Japan, and established the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its enhanced dispute settlement mechanism, which has provided a forum used by both Japan and the United States to resolve trade disputes;

- the rise of China as an economic power and trade partner has caused U.S. policymakers to shift attention from Japan to China as a primary source of concern; and

- the growth in the complexity and number of countries involved in global supply chains has likely diffused or shifted concerns over import competition as many Japanese products are now imported into the United States as components in finished products from other countries, thereby reducing the bilateral trade deficit.

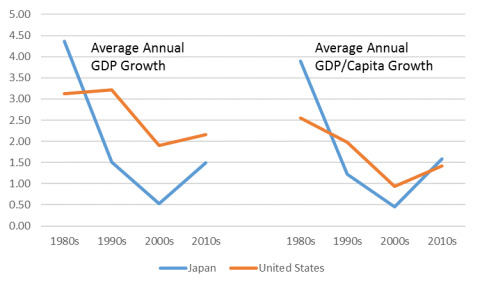

Japan's Growing Economy and Abenomics

Between the end of World War II and 1980s, Japan experienced high levels of economic growth. It was dubbed an "economic miracle" until the collapse of an economic bubble in Japan in the early 1990s brought an end to rapid economic growth. Many economists have argued that, despite the government's efforts, Japan has never fully recovered from the 1990s crisis. For decades Japan's economy suffered from chronic deflation (falling prices) and low growth. In the late 2000s, Japan's economy was also hit by two economic crises: the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, and the March 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear reactor meltdowns in northeast Japan. As a result, since the 1980s, Japan's average GDP growth has been consistently lower than that of the United States (Figure 3).70 In sharp contrast to the booming years of the 1980s, this decades-long history of economic stagnation coupled with, and in part a result of, the demographic challenge of a shrinking and ageing population has led to a narrative in the media and elsewhere of Japan as a nation in decline, particularly vis-à-vis the rapid economic growth and growing global influence of neighboring China and South Korea.

|

Figure 3. Average Annual GDP and GDP/Capita Growth (10-year average, U.S. and Japan) |

|

|

Source: World Economic Outlook, October 2018. |

In the face of domestic anxiety caused by this shift, Prime Minister Abe came into office in 2012 with a goal to reinvigorate the Japanese economy. Specifically, the Abe Administration made it a priority to boost economic growth and to eliminate deflation. Abe has promoted a three-pronged, or "three arrow," economic program, nicknamed "Abenomics." The three arrows include monetary stimulus, fiscal stimulus, and structural reforms to improve the competitiveness of Japan's economy. Most economists agree that progress across the three arrows has been uneven.

- The first arrow of Abenomics, monetary stimulus to reverse deflation, has been implemented most aggressively. In the spring of 2013, Japan's central bank (Bank of Japan, or BOJ) announced a continued loose monetary policy with interest rates of 0%, quantitative easing measures, and a target inflation rate of 2%. The BOJ began a second round of quantitative easing in October 2014, after the economy slipped back into recession. The BOJ continued adopting new expansionary monetary policies in 2016, including negative interest rates for a portion of bank reserves and targeting 0% interest rates on 10-year government bonds. In July 2018, BOJ Governor Kuroda announced the BOJ would maintain Japan's loose monetary policy, acknowledging that the BOJ's 2% inflation target would not be reached before 2021.71 Japan's inflation rate was 0.5% in 2017 and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts inflation of 1.2% in 2018.72 The BOJ actions contrast the Federal Reserve's steady tightening of U.S. monetary policy over the past year.

- The Japanese government has taken some steps to use fiscal policy to stimulate the economy (the second arrow), initially implementing fiscal stimulus packages worth about $145 billion, aimed at spending on infrastructure, particularly in the areas affected by the March 2011 disaster. The Abe government has also approved additional supplementary budget packages, including $32 billion in 2016.73 The government's willingness to use expansionary fiscal policies has been constrained by concerns about its public debt levels, the highest in the world at nearly 240% of GDP. To address fiscal pressures, the government raised the sales tax from 5% to 8% in April 2014. However, many economists argued that the sales tax increase was responsible for pushing Japan into recession in 2014. The government twice has postponed a planned second sales tax increase, to 10%, which now is scheduled to occur in October 2019, four years later than originally planned. The IMF urges Japan to implement mitigating fiscal policies to minimize the short-term downward pressure on demand expected from the tax hike.74

- Progress on the third arrow, structural reforms, has been more uneven.75 The government has advanced measures to liberalize energy and agriculture sectors, promote trade and investment, reform corporate governance, and improve labor market functions. The IMF argues, however, that more reforms are needed, particularly: (1) labor market reforms to increase productivity and boost wages (such as reforming Japan's two-tier labor market system by implementing complementary measures to make recent equal pay for equal work legislation more effective); (2) reforms to increase private investment and long-term growth (such as deregulation and encouraging business investment); and (3) measures to diversify and enhance the labor supply (such as encouraging more female participation in the work force including by increasing availability of childcare).