Overview

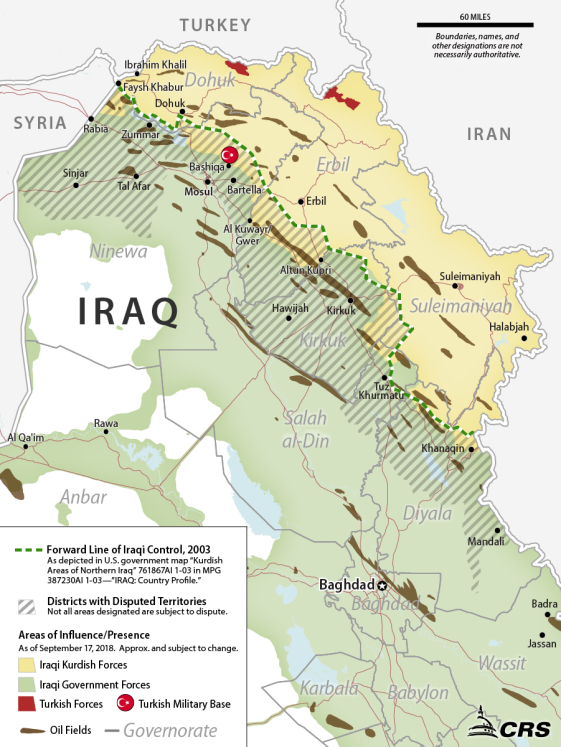

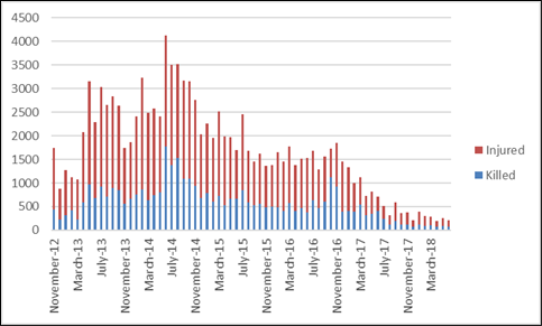

Iraq's government declared military victory against the Islamic State organization (IS, aka ISIS/ISIL) in December 2017, but insurgent attacks by remaining IS fighters threaten Iraqis as they shift their attention toward recovery and the country's political future. Security conditions have improved since the Islamic State's control of territory was disrupted (Figure 1 and Figure 2), but IS fighters are active in some areas of the country and security conditions are fluid. Meanwhile, daunting resettlement, reconstruction, and reform needs occupy citizens and leaders. Ethnic, religious, regional, and tribal identities remain politically relevant in Iraq, as do partisanship, personal rivalries, economic disparities, and natural resource imbalances.

National legislative elections were held in May 2018, but results were not certified until August, delaying the formal start of required steps to form the next government. Turnout was low relative to past national elections, and campaigning reflected issues stemming from the 2014-2017 conflict with the Islamic State as well as preexisting internal disputes and governance challenges.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi sought reelection, but his electoral list's third-place showing and lack of internal cohesion undermined his chances for a second term. He is serving in a caretaker capacity as government-formation negotiations continue. In September 2018, a statement from the office of leading Shia religious leader Grand Ayatollah Ali al Sistani called for political forces to choose a prime minister from beyond the ranks of current or former officials. Nevertheless, on October 2, Iraq's Council of Representatives chose former Kurdistan Regional Government Prime Minister and former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Barham Salih as Iraq's President. Salih, in turn, named former Oil Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi as Prime Minister-designate and directed him to assemble a slate of cabinet officials for approval by the Council of Representatives (COR).

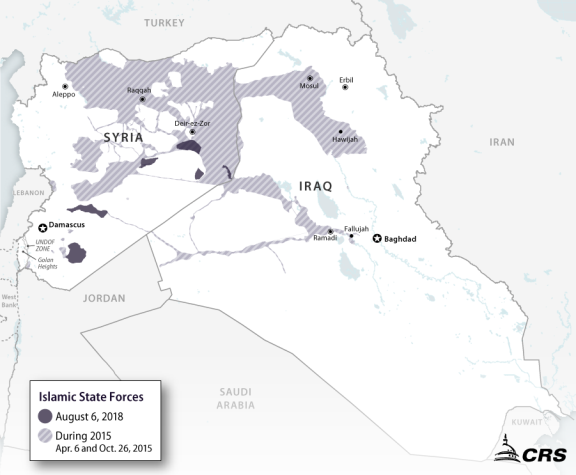

Paramilitary forces have grown stronger and more numerous since 2014, and have yet to be fully integrated into national security institutions. Some figures associated with the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) militias that were organized to fight the Islamic State participated in the 2018 election campaign and won seats in the COR, including individuals with ties to Iran.

Since the ouster of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraq's Shia Arab majority has exercised new power in concert with the Sunni Arab and Kurdish minorities. Despite ethnic and religious diversity and political differences, many Iraqis advance similar demands for improved security, government effectiveness, and economic opportunity. Large, volatile protests in southern Iraq during August and September 2018 highlighted some citizens' outrage with poor service delivery and corruption. Iraqi politicians have increasingly employed cross-sectarian political and economic narratives in an attempt to appeal to disaffected citizens, but identity-driven politics continue to influence developments across the country. Iraq's neighbors and other outsiders, including the United States, are pursuing their respective interests in the country, at times in competition.

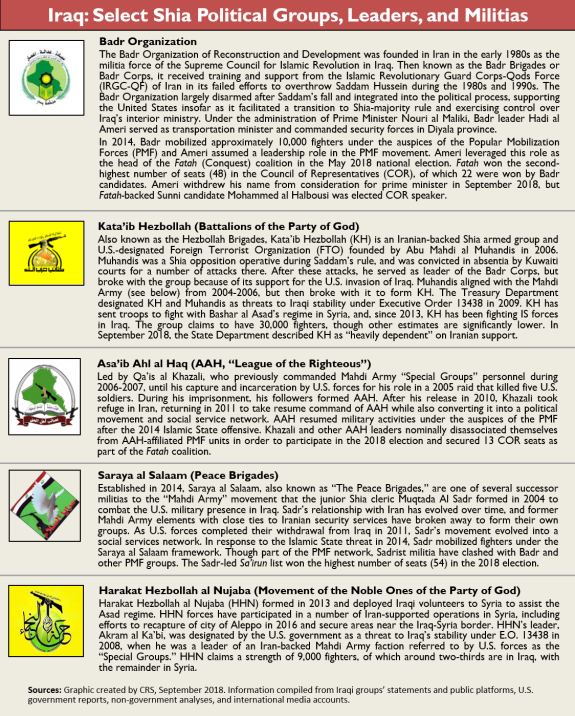

The Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq (KRI) enjoys considerable administrative autonomy under the terms of Iraq's 2005 constitution, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) held legislative elections on September 30, 2018. The KRG had held a controversial advisory referendum on independence in September 2017, amplifying political tensions with the national government and prompting criticism from the Trump Administration and the United Nations Security Council. In October 2017, the national government imposed a ban on international flights to and from the KRI, and Iraqi security forces moved to reassert security control of disputed areas that had been secured by Kurdish forces after the Islamic State's mid-2014 advance. Much of the oil-rich governorate of Kirkuk—long claimed by Iraqi Kurds—returned to national government control, and resulting controversies have riven Kurdish politics. Iraqi and Kurdish security forces remain deployed across from each other along contested lines of control while their respective leaders are engaged in negotiations over a host of sensitive issues.

Internally displaced Iraqis are returning home in greater numbers, but stabilization and reconstruction needs in areas liberated from the Islamic State are extensive. An estimated 1.9 million Iraqis remain as internally displaced persons (IDPs), and Iraqi authorities have identified $88 billion in reconstruction needs over the next decade.

In general, U.S. engagement with Iraqis since 2011 has sought to reinforce Iraq's unifying tendencies and avoid divisive outcomes. At the same time, successive U.S. Administrations have sought to keep U.S. involvement and investment minimal relative to the 2003-2011 era, pursuing U.S. interests through partnership with various entities in Iraq and the development of those partners' capabilities—rather than through extensive deployment of U.S. military forces. U.S. economic assistance bolsters Iraq's ability to attract lending support and is aimed at improving the government's effectiveness and public financial management. The United States is the leading provider of humanitarian assistance to Iraq and also supports post-IS stabilization activities across the country through grants to United Nations agencies and other entities.

The Trump Administration has sustained a cooperative relationship with the Iraqi government and has requested funding to support Iraq's stabilization and continue security training for Iraqi security forces. The size and missions of the U.S. military presence in Iraq has evolved as conditions on the ground have changed since 2017 and could change further if newly elected Iraqi officials revise their requests for U.S. and other international assistance.

To date, the 115th Congress has appropriated funds to continue U.S. military operations against the Islamic State and to provide security assistance, humanitarian relief, and foreign aid for Iraq. Appropriations and authorization legislation enacted or under consideration for FY2019 would largely continue U.S. policies and programs on current terms. For background on Iraq and its relations with the United States, see CRS Report R45025, Iraq: Background and U.S. Policy.

|

Figure 1. Estimated Iraqi Civilian Casualties from Conflict and Terrorism |

|

|

Source: United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq. Some months lack data from some governorates. |

|

|

|

Area: 438,317 sq. km (slightly more than three times the size of New York State) Population: 39.192 million (July 2017 estimate), ~59% are 24 years of age or under Internally Displaced Persons: 1.9 million (September 15, 2018) Religions: Muslim 99% (55-60% Shia, 40% Sunni), Christian <0.1%, Yazidi <0.1% Ethnic Groups: Arab 75-80%; Kurdish 15-20%; Turkmen, Assyrian, Shabak, Yazidi, other ~5%. Gross Domestic Product [GDP; growth rate]: $197.7 billion (2017 est); -0.8% (2017 est.) Budget (revenues; expenditure; balance): $77.42 billion, $88 billion, -$10.58 billion (2018 est.) Percentage of Revenue from Oil Exports: 87% (June 2017 est.) Current Account Balance: $1.42 billion (2017 est.) Oil and natural gas reserves: 142.5 billion barrels (2017 est., fifth largest); 3.158 trillion cubic meters (2017 est.) External Debt: $73.43 billion (2017 est.) Foreign Reserves: ~$47.02 billion (December 2017 est.) |

Sources: Graphic created by CRS using data from U.S. State Department and Esri. Country data from CIA, The World Factbook, September 2018, Iraq Ministry of Finance, and International Organization for Migration.

Developments in 2017 and 2018

Iraq Declares Victory against the Islamic State, Pursues Fighters

In July 2017, Prime Minister Haider al Abadi visited Mosul to mark the completion of major combat operations there against the Islamic State forces that had taken the city in June 2014. Iraqi forces subsequently retook the cities of Tal Afar and Hawijah, and launched operations in Anbar Governorate in October amid tensions elsewhere in territories disputed between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and national authorities. On December 9, 2017, Iraqi officials announced victory against the Islamic State and declared a national holiday. Although the Islamic State's exclusive control over distinct territories in Iraq has now ended, the U.S. intelligence community told Congress in February 2018 that the Islamic State "has started—and probably will maintain—a robust insurgency in Iraq and Syria as part of a long-term strategy to ultimately enable the reemergence of its so-called caliphate."1

|

Figure 2. Islamic State Territorial Control in Syria and Iraq, 2015-2018 |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service using IHS Markit Conflict Monitor, ESRI, and U.S. State Department data. |

As of October 2018, Iraqi security operations are ongoing in Anbar, Ninewa, Diyala, and Salah al Din against IS fighters. These operations are intended to disrupt IS fighters' efforts to reestablish themselves and keep them separated from population centers. Iraqi officials warn of IS efforts to use remaining safe havens in Syria to support infiltration of Iraq. Press reports and U.S. government reports describe continuing IS attacks, particularly in rural areas of governorates the group formerly controlled. Independent analysts describe dynamics in these areas in which IS fighters threaten, intimidate, and kill citizens in areas at night or where Iraq's national security forces are absent.2 In some areas, new displacement is occurring as civilians flee IS attacks.

May 2018 Election, Unrest, and Government Formation

|

Iraq's 2018 National Legislative Election Seats won by Coalition/Party

Source: Iraq Independent High Electoral Commission. |

On May 12, 2018, Iraqi voters went to the polls to choose national legislators for four-year terms in the 329-seat Council of Representatives, Iraq's unicameral legislature. Turnout was lower in the 2018 COR election than in past national elections, and reported irregularities led to a months-long recount effort that delayed certification of the results until August. Nevertheless, since May, the results have informed Iraqi negotiations aimed at forming the largest bloc within the COR—the parliamentary majority charged with proposing a prime minister and new Iraqi cabinet. Senior officials from Iran and the United States are monitoring the talks closely and consulting with leading Iraqi figures.

The Sa'irun (On the March) coalition led by populist Shia cleric and longtime U.S. antagonist Muqtada al Sadr's Istiqama (Integrity) list placed first in the election (54 seats), followed by the predominantly Shia Fatah (Conquest) coalition led by Hadi al Ameri of the Badr Organization (48 seats). Fatah includes several individuals formerly associated with the mostly Shia Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) militias that helped fight the Islamic State, including figures and movements with ties to Iran (see Figure 3 and "Popular Mobilization Forces and Iraqi Security Forces" below). Prime Minister Haider al Abadi's Nasr (Victory) coalition underperformed to place third (42 seats), and Abadi, who has been prime minister since 2014, is now serving in a caretaker role.

Former prime minister Nouri al Maliki's State of Law coalition, Ammar al Hakim's Hikma (Wisdom) list, and Iyad Allawi's Wataniya (National) list also won significant blocs of seats. Among Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) won the most seats, and smaller opposition lists protested alleged irregularities.

Escalating frustration in southern Iraq with unemployment, corruption, and electricity and water shortages has driven widespread popular unrest since the May election, amplified in some instances by citizens' anger about heavy-handed responses by security forces and militia groups. Dissatisfaction exploded in the southern province of Basra during August and September, culminating in several days and nights of mass demonstrations and the burning by protestors of the Iranian consulate in Basra and the offices of many leading political groups and militia movements. Reports from Basra in the weeks since the unrest suggest that some protestors have been intimidated or killed by unknown assailants.

Several pro-Iran groups and figures have accused the United States and other outside actors of instigating the unrest, in line with Iran-linked figures' broader accusations about alleged U.S. meddling in government formation talks.3 U.S. officials have attributed several rocket attacks near U.S. facilities in Iraq to Iran, stating that the United States would respond directly to attacks on U.S. facilities or personnel by Iranian-backed entities. 4 On September 28, the Trump Administration announced it would temporarily remove U.S. personnel from the U.S. Consulate in Basra in response to threats from Iran and Iranian-backed groups.5

The government-formation process in Iraq is ongoing, and leaders have taken formal steps to fill key positions since election results were finalized on August 19. In successive governments, Iraq's Prime Minister has been a Shia Arab, the President has been a Kurd, and the Council of Representatives Speaker has been a Sunni Arab, reflecting an informal agreement among leaders of these communities. On September 3, the first session of the newly elected COR was held, and, on September 15, members elected Mohammed al Halbousi, the governor of Anbar, as Speaker. Hassan al Kaabi of the Sa'iroun list and Bashir Hajji Haddad of the KDP were elected as First and Second Deputy Speaker, respectively.

On October 2, the COR met to elect Iraq's President, with rival Kurdish parties nominating competing candidates.6 COR members chose the PUK candidate - former KRG Prime Minister and former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Barham Salih - in the second round of voting. President Salih immediately named former Minister of Oil Adel Abd al Mahdi as the Prime Minister-designate of the largest bloc of COR members and directed him to form a government for COR consideration. Within thirty days (by November 1), the Prime Minister-designate is to present a slate of cabinet members and a government platform for COR approval.

|

Figure 3. Select Iraqi Shia Political Groups, Leaders, and Militias |

|

The contest to form the largest bloc and designate a prime minister candidate was shaped by the protests and attacks described above, with candidates drawn from the ranks of former officialdom disadvantaged by the public's apparent anti-incumbent mood. On September 7, the representative of Iraqi Shia supreme religious authority Grand Ayatollah Ali al Sistani decried Iraq's transformation into "an arena for regional and international conflicts" and said, "there should be pressure toward forming a new government that is different from the previous ones and to ensure that it takes into consideration the standards of efficiency, integrity, courage, firmness, and loyalty to the country and people as a basis for the selection of senior officials."7

A subsequent statement issued by Sistani's office denied rumors that Sistani had intervened to select or reject specific prime ministerial candidates and emphasized the prerogatives and duties of Iraq's elected leaders to do so.8 Notably, this second statement further attributed to Sistani the view that current and former Iraqi officials should not lead Iraq's next government. In the wake of these messages from Grand Ayatollah Al Sistani's office, Prime Minister Abadi announced that he would not "cling to power," which many observers regarded as the end of his public campaign for a second term.9 Badr Organization and Fatah coalition leader Hadi al Ameri also announced that would not pursue the position of prime minister.

Many observers of Iraqi politics regard Adel Abd al Mahdi as a compromise candidate acceptable to coalitions that have formed around the Fatah list on the one hand and the Sa'irun list on the other. While some in Congress have expressed concern about reported Iranian involvement in negotiations that led to Abd al Mahdi's nomination, Administration responses have highlighted past U.S. work with him and suggest they view the nomination as acceptable.10

Abd al Mahdi has been a key interlocutor for U.S. officials since shortly after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion that overthrew Saddam Hussein's regime. At the same time, he has been a prominent figure in the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), which has historically received substantial backing from Iran. He served as Minister of Finance in Iraq's appointed interim government and led the country's debt relief initiatives. He has publicly supported an inclusive approach to sensitive political, religious, and inter-communal issues, but his relationships with other powerful Iraqi Shia forces and Iran raise some questions about his ability to lead independently.11 Looking ahead, the new government's viability and the Prime Minister's freedom of action on controversial issues will be shaped by the durability of agreements among Iraqi coalitions and progress on citizens' priorities.

Popular Mobilization Forces and Iraqi Security Forces

Since its founding in 2014, Iraq's Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC) and its associated militias—the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF)—have contributed to Iraq's fight against the Islamic State. Despite appreciating those contributions, some Iraqis and outsiders have raised concerns about the future of the PMC/PMF and some of its members' ties to Iran.12 At issue has been the apparent unwillingness of some PMC/PMF entities to subordinate themselves to the command of Iraq's elected government and the ongoing participation in PMC/PMF operations of groups reported to receive direct Iranian support. In February 2018, the U.S. intelligence community told Congress that Iranian support to the PMC and "Shia militants remains the primary threat to U.S. personnel in Iraq." The community assessed that "this threat will increase as the threat from ISIS recedes, especially given calls from some Iranian-backed groups for the United States to withdraw and growing tension between Iran and the United States."13

Many PMF-associated groups and figures participated in the May 2018 national elections under the auspices of the Fatah coalition headed by Ameri.14 Ameri and other prominent PMF-linked figures such as Asa'ib Ahl al Haq (League of the Righteous) leader Qa'is al Khazali nominally disassociated themselves from the PMF in late 2017, in line with legal prohibitions on the participation of PMF officials in politics.15 Nevertheless, their movements' supporters and associated units remain integral to some ongoing PMF operations, and the Fatah coalition's campaign was arguably boosted by its members' past PMF activities.

During the election and in its aftermath, the key unresolved issue with regard to the PMC/PMF has remained the incomplete implementation of a 2016 law calling for the PMF to be incorporated as a permanent part of Iraq's national security establishment. In addition to outlining salary and benefit arrangements important to individual PMF volunteers, the law calls for all PMF units to be placed fully under the authority of the commander-in-chief [Prime Minister] and to be subject to military discipline and organization.

Through mid-2018, some PMF units were being administered in accordance with the law, but others have remained outside the law's directive structure. This includes some units associated with Shia groups identified by U.S. government reports as receiving or as having received Iranian support.16 According to August 2018 oversight reporting on Operation Inherent Resolve, Defense Department sources report that electioneering and government formation talks had "prevented any meaningful efforts to integrate the PMF into the ISF or the Ministries of Defense or Interior" through mid-year.

In general, the popularity of the PMF and broadly expressed popular respect for the sacrifices made by individual volunteers in the fight against the Islamic State create complicated political questions. From an institutional perspective, one might assume Iraqi political leaders would share incentives to assert full state control over all PMF units and other armed groups and to ensure the full implementation of the 2016 PMF law. However, in practice, different figures appear to favor different approaches, with some Iran-aligned figures appearing to prefer a model that preserves the relative independence of units loyal and responsive to them. Iraqi leaders arguably benefit politically from continuing to embrace the PMF and its personnel and from supporting volunteers during their demobilization or transition into security sector roles. Nevertheless, there also may be political costs to appearing too supportive of the PMF relative to other national security forces or to embracing Iran-linked units in particular.

Proposals for fully dismantling the PMC/PMF structure appear to be politically untenable at present, and, given the ongoing role PMF units are playing in security operations against remnants of the Islamic State in some areas, might create opportunities for IS fighters to exploit. Forceful confrontation between Iraqi security forces and Iran-backed groups within the PMF structure or outside of it could precipitate civil conflict and a crisis in Iraq-Iran relations. Attempts by Iraqi Security Forces to investigate allegations of illicit activity by some PMF units and Shia armed groups have resulted in violence in 2018. The Fatah coalition reacted angrily to Abadi's August 2018 decision to dismiss Fatah-aligned National Security Advisor and PMC head Falih al Fayyadh, calling the decision "illegal."17

Grand Ayatollah Al Sistani's office and his personal representatives have spoken directly about the importance of establishing and maintaining institutional control of all security forces in Iraq. This suggests that Sistani could make further public statements on the issue in the event that a figure with a different view takes office as prime minister or if some armed factions resist future government efforts at security force integration.

Though in a caretaker role, Prime Minister Abadi has made some recent attempts to assert the authority of the prime minister's office over the PMC/PMF and has expressed his desire to see U.S. military support for Iraq's security forces continue. Sa'irun leader Muqtada al Sadr remains critical of U.S. policy toward Iraq and the broader Middle East, but has not publicly called for the immediate withdrawal of foreign forces since the election. According to Defense Department sources cited in recent oversight reporting, Ameri and some Iran-aligned groups "appeared to have set aside hostility to the United States" through mid-2018 and "signaled a willingness to accept a continued United States military presence to train Iraqi forces."18 To date, there are no clear public indications that Iraq's emerging government will seek to substantially change current patterns of U.S.-Iraq cooperation or abandon plans for the integration of the PMF within the Iraqi Security Forces.

The Kurdistan Region and Relations with Baghdad

Following the Kurdistan region of Iraq's September 2017 referendum on independence from Iraq (see textbox below), already tense relations between the semi-autonomous federal region and the national government in Baghdad grew more strained.19 Kurdish parties had been divided among themselves over the wisdom of the referendum and relations with Baghdad, and post-referendum changes in territorial control in the disputed territories upended the Kurds' oil-based financial prospects and created new political differences among Iraqi Kurds.

|

The Kurdistan Region's September 2017 Referendum on Independence The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) held an official advisory referendum on independence from Iraq on September 25, 2017, despiterequests from the national government of Iraq, the United States, and other external actors to delay or cancel it. Kurdish leaders held the referendum on time and as planned, with more than 72% of eligible voters participating and roughly 92% voting "Yes." The referendum was held across the KRI and in other areas that were then under the control of Kurdish forces, including some areas subject to territorial disputes between the KRG and the national government, such as the multiethnic city of Kirkuk, adjacent oil-rich areas, and parts of Ninewa governorate populated by religious and ethnic minorities. Kurdish forces had secured many of these areas following the retreat of national government forces in the face of the Islamic State's rapid advance across northern Iraq in 2014. In the wake of the referendum, Iraqi national government leaders imposed a ban on international flights to and from the Kurdistan region, and, in October 2017, Prime Minister Abadi ordered Iraqi forces to return to the disputed territories that had been under the control of national forces prior to the Islamic State's 2014 advance, including Kirkuk. Iraqi authorities rescinded the international flight ban in 2018 after agreeing on border control, customs, and security at Kurdistan's international airports. Iraqi security forces and KRG peshmerga forces remain deployed across from each other at various fronts throughout the disputed territories, including deployments near the strategically sensitive tri-border area of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey (Figure 4). |

Elections for the Kurdistan National Assembly were delayed in November 2017 and held on September 30, 2018. Preliminary results suggest that the KDP won a plurality of the 111 seats, with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and smaller opposition and Islamist parties winning the balance.

U.S. officials have encouraged Kurds and other Iraqis to engage on issues of dispute and to avoid unilateral military actions that could further destabilize the situation. Iraqi national government and KRG officials continue to engage U.S. counterparts on related issues.

Economic and Fiscal Challenges Continue

The public finances of the national government and the KRG remain strained, amplifying the pressure on leaders working to address the country's security and service-provision challenges. On a national basis, the combined effects of lower global oil prices from 2014 through mid-2017, expansive public-sector liabilities, and the costs of the military campaign against the Islamic State have exacerbated budget deficits.20 The IMF estimated Iraq's 2017-2018 financing needs at 19% of GDP. Oil exports provide nearly 90% of public-sector revenue in Iraq, while non-oil sector growth has been hindered over time by insecurity, weak service delivery, and corruption.

Iraq's oil production and exports have increased since 2016, but fluctuations in oil prices undermined revenue gains until the latter half of 2017. Revenues have since improved, but Iraq has agreed to manage its overall oil production in line with mutually agreed Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) output limits. In August 2018, Iraq exported an average of 4 million barrels per day (mbd, including KRG-administered oil exports), above the March 2018 budget's 3.8 mbd export assumption and at prices well above the budget's $46 per barrel benchmark.21 The IMF projects modest GDP growth over the next five years and expects growth to be stronger in the non-oil sector if Iraq's implementation of agreed measures continues as oil output and exports plateau.

Fiscal pressures are more acute in the Kurdistan region, where the fallout from the national government's response to the September 2017 referendum has further sapped the ability of the KRG to pay salaries to its public-sector employees and security forces. The KRG's loss of control over significant oil resources in Kirkuk governorate coupled with changes implemented by national government authorities over shipments of oil from those fields via the KRG-controlled export pipeline to Turkey have contributed to a sharp decline in revenue for the KRG.

Related issues shaped consideration of the 2018 budget in the COR, with Kurdish representatives criticizing the government's budget proposal to allocate the KRG a smaller percentage of funds in 2018 than the 17% benchmark reflected in previous budgets. National government officials argue that KRG resources should be based on a revised population estimate, and the 2018 budget adopted in March 2018 does not specify a fixed percentage or amount for the KRG and requires the KRG to place all oil exports under federal control in exchange for financial allocations for verified expenses.

Humanitarian Issues and Stabilization

Humanitarian Conditions

U.N. officials report several issues of ongoing humanitarian concern including harassment by armed actors and threats of forced return.22 Humanitarian conditions remain difficult in many conflict-affected areas of Iraq, but December 2017 marked the first month since December 2013 that Iraqis who returned to their home areas outnumbered those who remained as internally displaced persons (IDPs) or became newly displaced. As of September 15, more than 4 million Iraqis had returned to their districts since 2014, while more than 1.9 million individuals remained displaced.23 These figures include those who were displaced and returned home in disputed areas in the wake of the September 2017 KRG referendum on independence.24 Ninewa governorate is home to the largest number of IDPs, reflecting the lingering effects of the intense military operations against the Islamic State in Mosul and other areas during 2017 (Table 2). Estimates suggest thousands of civilians were killed or wounded during the Mosul battle, which displaced more than 1 million people. The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) hosts nearly 38% of the remaining IDP population in Iraq.

IDP numbers in the KRI have declined since 2017, though not as rapidly as in some other governorates. Conditions for IDPs in Dohuk governorate remain the most challenging in the KRI, with more than 57% of Dohuk-based IDPs living in camps or critical shelters as of September 2018 according to International Organization for Migration surveys.

The U.N.'s 2018 Iraq humanitarian appeal expected that as many as 8.7 million Iraqis would require some form of humanitarian assistance in 2018 and sought $569 million to reach 3.4 million of them.25 As of October 2018, the appeal was 60% met with $342 million in funds provided and more than $250 million in additional funds provided outside the plan.26

|

IOM Estimates of IDPs by Location of Displacement |

% Change since 2017 |

|||

|

Governorate |

January 2017 |

January 2018 |

September 2018 |

|

|

Suleimaniyah |

153,816 |

188,142 |

151,164 |

-2% |

|

Erbil |

346,080 |

253,116 |

217,548 |

-37% |

|

Dohuk |

397,014 |

362,670 |

349,656 |

-12% |

|

KRI Total |

896,910 |

806,976 |

718,368 |

-20% |

|

Ninewa |

409,020 |

795,360 |

595,632 |

+46% |

|

Salah al Din |

315,876 |

241,404 |

158,346 |

-50% |

|

Baghdad |

393,066 |

176,700 |

82,494 |

-79% |

|

Kirkuk |

367,188 |

172,854 |

117,444 |

-68% |

|

Anbar |

268,428 |

108,894 |

71,190 |

-73% |

|

Diyala |

75,624 |

81,972 |

61,644 |

-18% |

Source: International Organization for Migration, Iraq Displacement Tracking Monitor Data.

Stabilization and Reconstruction

At a February 2018 reconstruction conference in Kuwait, Iraqi authorities described more than $88 billion in short- and medium-term reconstruction needs, spanning various sectors and different areas of the country.27 Countries participating in the conference offered approximately $30 billion worth of loans, investment pledges, export credit arrangements, and grants in response. The Trump Administration actively supported the participation of U.S. companies in the conference and announced its intent to pursue $3 billion in Export-Import Bank support for Iraq.

U.S. stabilization assistance to areas of Iraq that have been liberated from the Islamic State is directed through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP)-administered Funding Facility for Stabilization (FFS).28 According to UNDP data, the FFS has received more than $690 million in resources since its inception in mid-2015, with 1,100 projects reported completed and a further 1,250 projects underway or planned with the support of UNDP-managed funding.29 In August 2018, UNDP identified a "funding gap" of $505 million for stabilization projects in what it describes as "strategic red box zones" (i.e., "the areas that are most vulnerable to the re-emergence of violent extremism and were last to be liberated") in Ninewa, Anbar, and Salah al Din governorates.30 UNDP highlights unexploded ordnance, customs clearance delays, and the growth in volume and scope of FFS projects as challenges to its ongoing work.31

Iraqi leaders hope to attract considerable private sector investment to help finance its reconstruction needs and underwrite a new economic chapter for the country. The size of Iraq's internal market and its advantages as a low-cost energy producer with identified infrastructure investment needs help make it attractive to investors, but overcoming persistent concerns about security, service reliability, and corruption may prove challenging. The formation of the new Iraqi government and its reform plans may provide key signals to parties exploring investment opportunities.

Issues in the 115th Congress

As Congress has considered the Trump Administration's requests for FY2019 foreign assistance and defense funding, Iraqis have been engaged in competitive electioneering and government formation negotiations, while working to rebuild war-torn areas of their country. The final FY2018 appropriations acts approved in March 2018 (P.L. 115-141) made additional U.S. funding available for U.S. defense programs and contributions to immediate post-IS stabilization efforts, while also renewing authorities for U.S. economic loan guarantees to Iraq.

Defense authorization (P.L. 115-232) and appropriation (Division A of P.L. 115-245) legislation enacted for FY2019 extends congressional authorization for U.S. training, equipping, and advisory programs for Iraqi security forces until December 2020 and makes $850 million in additional defense funding available for security assistance programs through FY2020. Congress has limited the availability of these funds, authorizing the obligation or expenditure of no more than $450 million for Iraq train and equip efforts until the Administration submits required strategy and oversight reporting.32

The FY2018 NDAA [Section 1224(c) of P.L. 115-91] modified the authority of the Office of Security Cooperation at the U.S. Embassy in Iraq (OSC-I) to widen the range of forces that the office may engage with professionalization and management assistance from Ministry of Defense and Counter Terrorism Service personnel to include all "military and other security forces with a national security mission."33 The Administration's FY2019 defense funding request outlines plans for U.S. training of Iraqi border security forces, energy security forces, emergency response police units, Counterterrorism Service forces, and ranger units.

The FY2019 Continuing Appropriations Act (Division C of P.L. 115-245) makes funds available for foreign operations programs in Iraq on the terms and at the levels provided for in FY2018 appropriations through December 7, 2018. Foreign operations appropriations bills considered by the House and Senate would appropriate FY2019 funds for Iraq programs differently.

- The House version of the FY2019 Foreign Operations Appropriations bill (H.R. 6385) would make funds available "to promote governance and security, and for stabilization programs, including in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq …in accordance with the Constitution of Iraq." The accompanying report (H.Rept. 115-829) would direct $50 million in funds made available by the act for stabilization and recovery be used "for assistance to support the safe return of displaced religious and ethnic minorities to their communities in Iraq."

- The Senate version (S. 3108) and accompanying report (S.Rept. 115-282) would make $429.4 million available in FY2019 funding across various accounts, including $250 million in Foreign Military Financing assistance not requested by the Trump Administration. The Senate version also would direct that additional assistance monies in various accounts be made available for a $250 million Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF) for areas liberated or at risk from the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations, and the accompanying report contains a further direction that $100 million in funds appropriated for RRF purposes in prior acts be made available for programs in Iraq.

The Trump Administration signaled that decisions about future U.S. assistance efforts will be shaped by the outcome of Iraqi government formation talks. In September 2018, U.S. officials suggested they would like to see prevailing patterns of U.S. assistance continue, but an unnamed senior U.S. official also said that the Administration is prepared to reconsider U.S. support to Iraq if individuals perceived to be close to or controlled by Iran assume positions of authority in Iraq's new government.34 Legislation enacted and under consideration in the second session of the 115th Congress would require annual reporting on Iraqi entities and individuals receiving Iranian support and would codify authorities currently available to the President under executive order to place sanctions on individuals threatening the security or stability of Iraq (see "The United States and Iran in Iraq" below).

U.S. Military Operations

Iraqi military and counterterrorism operations against scattered supporters of the Islamic State group are ongoing, and the United States military and its coalition partners continue to provide support to those efforts at the request of the Iraqi government. U.S. military operations against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria are organized under the command of Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR).

The Trump Administration, like the Obama Administration, has cited the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF, P.L. 107-40) as the domestic legal authorization for U.S. military operations against the Islamic State in Iraq and refers to both collective and individual self-defense provisions of the U.N. Charter as the relevant international legal justifications for ongoing U.S. operations in Iraq and Syria. The U.S. military presence in Iraq is governed by an exchange of diplomatic notes that reference the security provisions of the 2008 bilateral Strategic Framework Agreement.35 This arrangement has not required approval of a separate security agreement by Iraq's Council of Representatives. In July 2018, NATO inaugurated a "non-combat training and capacity-building mission" at the request of the Iraqi government.

The overall volume and pace of U.S. strikes against IS targets in Iraq has diminished since the end of 2017, with U.S. training efforts for various Iraqi security forces ongoing at various locations, including in the Kurdistan region, pursuant to the authorities granted by Congress for the Iraq Train and Equip Program and for the activities of the OSC-I.36 As of August 2018, U.S. and coalition training had benefitted more than 150,000 Iraqi security personnel since 2014. From FY2015 through FY2019, Congress authorized and appropriated more than $5.8 billion for train and equip assistance in Iraq (Table 3).

|

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 Requests |

FY2018 Iraq-Specific Request |

FY2019 Iraq-Specific Request |

|

|

Iraq Train and Equip Fund |

1,618,000 |

715,000 |

630,000 |

- |

- |

|

289,500 (FY17 CR) |

|||||

|

Additional Counter-ISIL |

- |

- |

446,400 |

1,269,000 |

850,000 |

|

Total |

1,618,000 |

715,000 |

1,365,900 |

1,269,000 |

850,000 |

Source: Executive branch appropriations requests and appropriations legislation.

The Trump Administration has not reported the number of U.S. personnel in Iraq since September 2017.37 In February 2018, General Joseph Votel, Commander of U.S. Central Command, stated that there has been a reduction in the number of U.S. military personnel and changes in U.S. capabilities in Iraq from 2017 levels.38 U.S. military sources have stated that the "continued coalition presence in Iraq will be conditions-based, proportional to the need, and in coordination with the government of Iraq."39 As of October 2018, 67 U.S. military personnel and DOD civilians have been killed or have died as part of OIR, and 72 U.S. persons have been wounded. Through March 2018, OIR operations since August 2014 had cost $23.5 billion.40

|

Assistance to the Kurdistan Regional Government and in the Kurdistan Region Congress has authorized the President to provide U.S. assistance to the Kurdish peshmerga and certain Sunni and other local security forces with a national security mission in coordination with the Iraqi government, and to do so directly under certain circumstances. Pursuant to a 2016 U.S.-KRG memorandum of understanding (MOU), the United States has offered more than $400 million in defense funding and in-kind support to the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq, delivered in smaller monthly installments. The December 2016 continuing resolution (P.L. 114-254) included $289.5 million in FY2017 Iraq training program funds to continue support for peshmerga forces. In 2017, the Trump Administration requested an additional $365 million in defense funding to support programs with the KRG and KRG-Baghdad cooperation as part of the FY2018 train and equip request. The Administration also proposed a sale of infantry and artillery equipment for peshmerga forces that Iraq agreed to finance using a portion of its U.S.-subsidized Foreign Military Financing loan proceeds. The Administration's FY2019 Iraq Train and Equip program funding request refers to the peshmerga as a component of the ISF and discusses the peshmerga in the context of a $290 million request for potential ISF-wide sustainment aid. The conference report (H.Rept. 115-952) accompanying the FY2019 Defense Appropriations Act (Division A of P.L. 115-245) says the United States "should" provide this amount for "operational sustainment" for Ministry of Peshmerga forces. Kurdish officials report that U.S. training support and consultation on plans to reform the KRG Ministry of Peshmerga and its forces continue. The Department of Defense reports that it has resumed paying the salaries of peshmerga personnel in units aligned by the Ministry of Peshmerga, after a pause following the September 2017 independence referendum. Congress has directed in recent years that U.S. foreign assistance, humanitarian aid, and loan guarantees be implemented in Iraq in ways that benefit Iraqis in all areas of the country, including in the Kurdistan region. |

U.S. Foreign Assistance

In recent years, the U.S. government has provided State Department- and USAID-administered assistance to Iraq to support a range of security and economic objectives. U.S. Foreign Military Financing (FMF) funds have supported the costs of continued loan-funded purchases of U.S. defense equipment and helped fund Iraqi defense institution building efforts. Congressionally authorized U.S. loan guarantees also have supported successful Iraqi bond issues to help Baghdad cover its fiscal deficits. Since 2014, the United States has contributed more than $1.7 billion to humanitarian relief efforts in Iraq,41 including more than $607 million in humanitarian support in FY2017 and FY2018.42

The Administration's FY2019 request seeks more than $199 million for stabilization and other non-military assistance programs in Iraq (Table 4). The Senate version of the FY2019 foreign operations appropriations act (S. 3108, S.Rept. 115-282) would appropriate $150 million in ESF, along with $250 million in Foreign Military Financing and other security assistance funds. The Senate version also would direct that $50 million in FY2019 ESF funds be provided for stabilization in Iraq, in addition to $100 million in previously appropriated Relief and Recovery Fund-designated monies.43 The report accompanying the House version of the bill (H.Rept. 115-829, H.R. 6385) would direct $50 million in FY2019 funds available for stabilization programs "for assistance to support the safe return of displaced religious and ethnic minorities to their communities in Iraq."

Table 4. U.S. Assistance to Iraq: Select Obligations, Allocations, and Requests

in millions of dollars

|

Account |

FY2012 Obligated |

FY2013 Obligated |

FY2014 Obligated |

FY2015 Obligated |

FY2016 Obligated |

FY2017 Actual |

FY2018 Req. |

FY2019 Req. |

|

FMF |

79.555 |

37.290 |

300.000 |

150.000 |

250.000 |

250.00 |

- |

- |

|

ESF/ ESDF |

275.903 |

128.041 |

61.238 |

50.282 |

116.452 |

553.50 |

300.000 |

150.000 |

|

INCLE |

309.353 |

- |

11.199 |

3.529 |

- |

0.20 |

- |

2.000 |

|

NADR |

16.547 |

9.460 |

18.318 |

4.039 |

38.308 |

56.92 |

46.860 |

46.860 |

|

DF |

0.540 |

26.359 |

18.107 |

- |

.028 |

- |

- |

|

|

IMET |

1.997 |

1.115 |

1.471 |

0.902 |

0.993 |

0.70 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

|

Total |

683.895 |

202.265 |

410.333 |

208.752 |

405.781 |

1061.12 |

347.860 |

199.860 |

Sources: Obligations data derived from U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants (Greenbook), January 2017. FY2016-FY2019 data from State Department Congressional Budget Justification and other executive branch documents.

Notes: FMF = Foreign Military Financing; ESF/ESDF = Economic Support Fund/Economic Support and Development Fund; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; DF = Democracy Fund; IMET = International Military Education and Training.

The FY2018 foreign operations appropriations act (Division K, P.L. 115-141) stated that funds shall be available for stabilization in Iraq, and U.S. support to stabilization programs is ongoing using funds appropriated in FY2017. Since mid-2016, the executive branch has notified Congress of its intent to obligate $265.3 million in assistance funding to support UNDP FFS programs, including post-IS stabilization funding made available in the December 2016 continuing resolution (Division B of P.L. 114-254, see textbox below).44 Trump Administration requests for FY2018 and FY2019 monies for Iraq programs included requests to fund continued U.S. contributions to post-IS stabilization programs. No new contributions to U.N.-managed stabilization programs have been announced in 2018.

The United States also contributes to Iraqi programs to stabilize the Mosul Dam on the Tigris River, which remains at risk of collapse due to structural flaws, overlooked maintenance, and its compromised location. The State Department notes that Iraq is working to stabilize the dam, but "it is impossible to accurately predict the likelihood of the dam's failing…."45

|

Stabilization and Issues Affecting Religious and Ethnic Minorities State Department reports on human rights conditions and religious freedom in Iraq have documented the difficulties faced by religious and ethnic minorities in the country for years. In some cases, these difficulties and security risks have driven members of minority groups to flee the country or to take shelter in different areas of the country, whether with fellow group members or in new communities. Minority groups that live in areas subject to long-running territorial disputes between Iraq's national government and the KRG face additional interference and exploitation by larger groups for political, economic, or security reasons. Members of diverse minority communities express a variety of territorial claims and administrative preferences, both among and within their own groups. While much attention is focused on potential intimidation or coercion of minorities by majority groups, disputes within and among minority communities also have the potential to generate tension and violence. In October 2017, Vice President Mike Pence said in a speech that the U.S. government would direct more support to persecuted religious minority groups in the Middle East, including in Iraq. As part of this initiative, the Trump Administration has negotiated with UNDP to direct U.S. contributions to the UNDP Funding Facility for Stabilization (FFS) to the Ninewa Plains and other minority populated areas of northern Iraq. In October 2017, USAID solicited proposals in a Broad Agency Announcement for cooperative programs "to facilitate the safe and voluntary return of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) to their homes in the Ninewa plains and western Ninewa of Iraq and to encourage those who already are in their communities to remain there."46 In parallel, USAID notified Congress of its intent to obligate $14 million in FY2017 ESF-OCO for stabilization programs. In January 2018, USAID officials released to UNDP a $75 million first tranche of stabilization assistance from an overall pledge of $150 million that had been announced in July 2017 and notified for planned obligation to Congress in April 2017. According to the January 2018 announcement, USAID "renegotiated" the contribution agreement with UNDP so that $55 million of the $75 million payment "will address the needs of vulnerable religious and ethnic minority communities in Ninewa Province, especially those who have been victims of atrocities by ISIS" with a focus on "restoring services such as water, electricity, sewage, health, and education."47 USAID Administrator Mark Green visited Iraq in June 2018 and engaged with ethnic and religious minority groups in Ninewa. He also announced $10 million in awards under USAID's October 2017 proposal solicitation. Inclusive of the January announcement, the United States has provided $198.65 million to support the FFS—which remains the main international conduit for post-IS stabilization assistance in liberated areas of Iraq. According to UNDP, overall stabilization priorities for the FFS program are set by a steering committee chaired by the government of Iraq, with governorate-level Iraqi authorities directly responsible for implementation. UNDP officials report that earmarking of funding by donors "can result in funding being directed away from areas highlighted by the Iraqi authorities as being in great need."48 At the end of the second quarter of 2018, UNDP reported that 214 projects in minority communities of were complete out of 416 overall projects completed, planned, or under way in the Ninewa Plains.49 |

The United States and Iran in Iraq

The Trump Administration seeks to more proactively challenge, contain, and roll back Iran's regional influence, while attempting to solidify a long-term partnership with the government of Iraq and ensure Iraq's economic stability.50 These dual, and sometimes competing, goals raise several policy questions for U.S. officials and Members of Congress to consider. These include questions about

- the makeup and viability of the emergent Iraqi government,

- Iraqi leaders' approaches to Iran-backed groups and the future of militia forces mobilized to fight the Islamic State,

- Iraq's compliance with U.S. sanctions on Iran,

- the future extent and roles of the U.S. military presence in Iraq,

- the terms and conditions associated with U.S. security assistance to Iraqi forces,

- U.S. relations with Iraqi constituent groups such as the Kurds, and

- potential responses to U.S. efforts to contain or confront Iran-aligned entities in Iraq or elsewhere in the region.

The 115th Congress has considered proposals to direct the Administration to impose U.S. sanctions on some Iran-aligned Iraqi groups, and has enacted legislation containing reporting requirements focused on Iranian support to non-state actors in Iraq and other countries.

- The FY2018 NDAA augmented annual reporting requirements on Iran to include reporting on the use of the Iranian commercial aviation sector to support U.S.-designated terrorist organization Kata'ib Hezbollah and other groups (Section 1225 of P.L. 115-91).

- An amendment adopted to the House version of the FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act would have required the President to impose specified sanctions on Asa'ib Ahl al Haq, Harakat Hezbollah al Nujaba, and certain associated persons (Section 1230F of H.R.5515EH). The provision was not included in the conference version of the bill (P.L. 115-232). The conference report encourages the Secretary of State "to continuously review whether groups that are affiliated with Iran meet the criteria for designation as a foreign terrorist organization or the application of sanctions pursuant to Executive Order 13224." S. 3431, introduced in September 2018, would also require the imposition of sanctions on those groups. A similar bill, H.R. 4238, was introduced in the House in November 2017.

- The House version of the FY2019 National Intelligence Authorization Act would require the Director of National Intelligence to report within 90 days of enactment on Iranian government spending on terrorist and military activities outside Iran's borders including support to "proxy forces" in Iraq (Section 2515 of H.R. 6237EH). The annually required report on Iran's military power includes criteria focused on Iranian support to non-state groups around the world.

- In September 2018, the House Foreign Affairs Committee approved and reported to the House an amended version of H.R. 4591, which, subject to national security waiver, would direct the President to impose sanctions on "any foreign person that the President determines knowingly commits a significant act of violence that has the direct purpose or effect of—(1) threatening the peace or stability of Iraq or the Government of Iraq; (2) undermining the democratic process in Iraq; or (3) undermining significantly efforts to promote economic reconstruction and political reform in Iraq or to provide humanitarian assistance to the Iraqi people."

- H.R. 4591 would further require the Secretary of State to submit a determination as to whether Asa'ib Ahl al Haq, Harakat Hizballah al Nujaba, or affiliated persons and entities meet terrorist designation criteria or the sanctions criteria of the bill. The bill also would direct the Secretary of State to prepare, maintain, and publish a "a list of armed groups, militias, or proxy forces in Iraq receiving logistical, military, or financial assistance from Iran's Revolutionary Guard Corps or over which Iran's Revolutionary Guard Corps exerts any form of control or influence."

Iran-linked actors in Iraq have directly targeted U.S. forces in the past, and some maintain the ability and state their willingness to do so again under certain circumstances. U.S. officials blamed these groups for apparent indirect weaponry attacks on U.S. diplomatic facilities in Basra and Baghdad in late September. These attacks followed reports that Iran had transferred short range ballistic missiles to Iran-backed militias in Iraq, reportedly including Kata'ib Hezbollah. Efforts to punish or sideline these groups, via sanctions or other means, could reduce Iran's influence in Iraq in ways that could serve U.S. national security interests. However, U.S. efforts to counter Iranian activities in Iraq, and elsewhere in the region, have the potential to complicate other U.S. interests in Iraq. Aggressively confronting Iran and its allies in Iraq could disrupt relations among parties to the emerging government in Baghdad, or even precipitate further civil conflict, undermining the U.S. goal of ensuring the stability and authority of the Iraqi government.

Additionally, while a wide range of Iraqi actors have ties to Iran, the nature of those ties differs, and treating these diverse groups uniformly risks ostracizing potential U.S. partners or neglecting opportunities to create divisions between these groups and Iran. With regard to the imposition of U.S. sanctions, some analysts have argued, "the timing and sequencing of any such move is critical to maximizing desired effects and minimizing Tehran's ability to exploit Iraqi blowback."51

While much attention focuses on the future of Iran-backed armed groups, the new Iraqi government's decisions about compliance with U.S. sanctions on Iran also may prove sensitive in coming months. Newly elected COR Speaker Halbousi has said that "Iraq will always be alongside the Iranian people" and that he and others in the COR "opposed the exercise of any economic pressure and embargo on Iran."52

Iraq's relations with the Arab Gulf states also shape the balance of Iranian and U.S. interests. U.S. officials have praised Saudi efforts since 2015 to reengage with the Iraqi government and support normalization of ties between the countries. In December 2015, Saudi officials reopened the kingdom's diplomatic offices in Iraq after a 25-year absence, and border crossings between the two countries have been reopened. Saudi Arabia and the other GCC states have not offered major new economic or security assistance or new debt relief initiatives to help stabilize Iraq, but actively engaged in and supported the February 2018 reconstruction conference held by Iraq in Kuwait. Saudi and other GCC state officials generally view the empowerment of Iran-linked Shia militia groups in Iraq with suspicion and, like the United States, seek to limit Iran's ability to influence political and security developments in Iraq.

Outlook

Negotiations among Iraqi factions following the May 2018 election have not fully resolved outstanding questions about the future of U.S.-Iraqi relations. Prime Minister Abadi, with whom the U.S. government worked closely, could not translate his list's third-place finish into a mandate for a second term. His designated successor, Prime Minister-designate Adel Abd al Mahdi served in Abadi's government and is an individual with whom U.S. officials have worked positively in the past. Yet, the nature and durability of the political coalition arrangements supporting his leadership are unclear, and he lacks a strong personal electoral mandate. Similarly, Iraqi President Barham Salih is familiar to U.S. officials as a leading and friendly figure among Iraqi Kurds, but his election comes at time of significant political differences among Kurds and amid strained relations between Kurds and the national government.

There is little public indication at present that Iraqi authorities intend to request that the United States dramatically alter its assistance approach to or end its military presence in Iraq, including with regard to the Kurdistan region. However, the United States could face countervailing requests from its various Iraqi partners in the event that anti-U.S. political forces emerge more empowered from remaining government formation steps or through the new government's policies. It remains possible that the national government could more strictly assert its sovereign prerogatives with regard to the presence of foreign military forces and foreign assistance to sub-state entities, and/or that KRG representatives could seek expanded or more direct foreign support.

Some Iraqi groups, such as the Shia militant organization Kata'ib Hezbollah, remain vocally critical of the remaining U.S. and coalition military presence in the country and argue that the defeat of the Islamic State's main forces means that U.S. and other foreign forces should depart. These and similar groups also accuse the United States of seeking to undermine the Popular Mobilization Forces or otherwise subordinate Iraq to U.S. preferences. Most mainstream Iraqi political movements or leaders did not use the U.S. military presence as a major wedge issue in the run-up to or aftermath of the May 2018 election and have not directly called for an end to security partnership with the United States.

Members of Congress and U.S. officials face difficulties in developing policy options that can secure U.S. interests on specific issues without provoking levels of opposition from Iraqi constituencies that may jeopardize wider U.S. goals. Debates over U.S. military support to Iraqi national forces and sub-state actors in the fight against the Islamic State illustrated this dynamic, with some U.S. proposals for the provision of aid to all capable Iraqi forces facing criticism from Iraqi groups suspicious of U.S. intentions or fearful that U.S. assistance could empower their domestic rivals. U.S. aid to the Kurds to date has been provided with the approval of the Baghdad government, though some Members have advocated for assistance to be provided directly to the KRG.

U.S. assistance to Baghdad is provided on the understanding that U.S. equipment will be responsibly used by its intended recipients, and some Members have expressed concerns about the use of U.S.-origin defense equipment by actors or in ways that Congress has not intended, including a now-resolved case involving the possession and use of U.S.-origin tanks by elements of the Popular Mobilization Forces. The strained relationship between national government and Kurdish forces along the disputed territories and the future of the Popular Mobilization Forces implicate these issues directly and may remain relevant to debates over the continuation of prevailing patterns of U.S. assistance.

Once negotiations over cabinet positions are completed and a new government is seated, debate over the 2019 budget, reform of the water and electricity sectors, employment initiatives, and national security issues are expected to define the political agenda in Iraq. It seems reasonable to expect that Iraqis will continue to assess and respond to U.S. initiatives (and those of other outsiders) primarily through the lenses of their own domestic political rivalries, anxieties, and agendas. Reconciling U.S. preferences and interests with Iraq's evolving politics and security conditions may thus require continued creativity, flexibility, and patience.