Background

Prior to World War I, the territories comprising modern-day Lebanon were governed as separate administrative regions of the Ottoman Empire. After the war ended and the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement divided the empire's Arab provinces into British and French zones of influence. The area constituting modern day Lebanon was granted to France, and in 1920, French authorities announced the creation of Greater Lebanon. To form this new entity, French authorities combined the Maronite Christian enclave of Mount Lebanon—semiautonomous under Ottoman rule—with the coastal cities of Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon, and Tyre and their surrounding districts. These latter districts were (with the exception of Beirut) primarily Muslim and had been administered by the Ottomans as part of the vilayet (province) of Syria.

|

|

Population: 6,229,794 (2017 est., includes Syrian refugees) Religion: Muslim 54% (27% Sunni, 27% Shia), Christian 40.5% (includes 21% Maronite Catholic, 8% Greek Orthodox, 5% Greek Catholic, 6.5% other Christian), Druze 5.6%, very small numbers of Jews, Baha'is, Buddhists, Hindus, and Mormons. Note: 18 religious sects recognized Land: (Area) 10,400 sq km, 0.7 the size of Connecticut; (Borders) Israel, 81 km; Syria, 403 km GDP: (PPP, growth rate, per capita 2017 est.) $87.8 billion, 1.5%, $19,500 Budget: (spending, deficit, 2017 est.) $15.99 billion, -9.7% of GDP Public Debt: (2017 est.) 142.2% of GDP |

Source: Created by CRS using ESRI, Google Maps, and Good Shepherd Engineering and Computing. CIA, The World Factbook data, June 7, 2018.

These administrative divisions created the boundaries of the modern Lebanese state; historians note that "Lebanon, in the frontiers defined on 1 September 1920, had never existed before in history."1 The new Muslim residents of Greater Lebanon—many with long-established economic links to the Syrian interior—opposed the move, and some called for integration with Syria as part of a broader postwar Arab nationalist movement. Meanwhile, many Maronite Christians—some of whom also self-identified as ethnically distinct from their Arab neighbors—sought a Christian state under French protection. The resulting debate over Lebanese identity would shape the new country's politics for decades to come.

Independence. In 1943, Lebanon gained independence from France. Lebanese leaders agreed to an informal National Pact, in which each of the country's officially recognized religious groups were to be represented in government in direct relation to their share of the population, based on the 1932 census. The presidency was to be reserved for a Maronite Christian (the largest single denomination at that time), the prime minister post for a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of parliament for a Shia. Lebanon has not held a census since 1932, amid fears (largely among Christians) that any demographic changes revealed by a new census—such as a Christian population that was no longer the majority—would upset the status quo.2

Civil War. In the decades that followed, Lebanon's sectarian balance remained a point of friction between communities. Christian dominance in Lebanon was challenged by a number of events, including the influx of (primarily Sunni Muslim) Palestinian refugees as a result of the Arab-Israeli conflict, and the mobilization of Lebanon's Shia Muslim community in the south—which had been politically and economically marginalized. These and other factors would lead the country into a civil war that lasted from 1975 to 1990 and killed an estimated 150,000 people. While the war pitted sectarian communities against one another, there was also significant fighting within communities.

Foreign Intervention. The civil war drew in a number of external actors, including Syria, Israel, Iran, and the United States. Syrian military forces intervened in the conflict in 1976, and remained in Lebanon for another 29 years. Israel sent military forces into Lebanon in 1978 and 1982, and conducted several subsequent airstrikes in the country. In 1978, the U.N. Security Council established the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) to supervise the withdrawal of Israeli forces from southern Lebanon, which was not complete until 2000.3 In the early 1980s, Israel's military presence in the heavily Shia area of southern Lebanon began to be contested by an emerging militant group that would become Hezbollah, backed by Iran. The United States deployed forces to Lebanon in 1982 as part of a multinational peacekeeping force, but withdrew its forces after the 1983 marine barracks bombing in Beirut, which killed 241 U.S. personnel.

Taif Accords. In 1989, the parties signed the Taif Accords, beginning a process that would bring the war to a close the following year. The agreement adjusted and formalized Lebanon's confessional system, further entrenching what some described as an unstable power dynamic between different sectarian groups at the national level. The political rifts created by this system allowed Syria to present itself as the arbiter between rivals, and pursue its own interests inside Lebanon in the wake of the war. The participation of Syrian troops in Operation Desert Storm to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait reportedly facilitated what some viewed as the tacit acceptance by the United States of Syria's continuing role in Lebanon. The Taif Accords also called for all Lebanese militias to be dismantled, and most were reincorporated into the Lebanese Armed Forces. However, Hezbollah refused to disarm—claiming that its militia forces were legitimately engaged in resistance to the Israeli military presence in southern Lebanon.

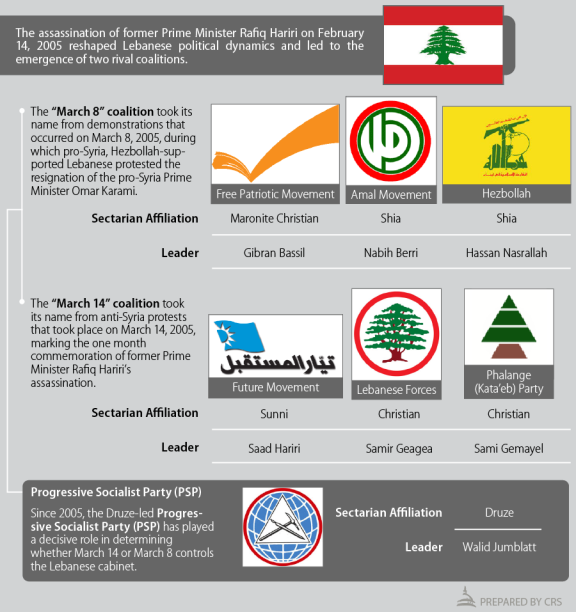

Hariri Assassination. In February 2005, former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri—a prominent anti-Syria Sunni politician—was assassinated in a car bombing in downtown Beirut. The attack galvanized Lebanese society against the Syrian military presence in the country and triggered a series of street protests known as the "Cedar Revolution." Under pressure, Syria withdrew its forces from Lebanon in the subsequent months, although Damascus continued to influence domestic Lebanese politics. While the full details of the attack are unknown, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) has indicted five members of Hezbollah and is conducting trials in absentia.4 The Hariri assassination reshaped Lebanese politics into the two major blocks known today: March 8 and March 14, which represented pro-Syria and anti-Syria segments of the political spectrum, respectively (see Figure 2).

2006 Hezbollah-Israel War. In July 2006, Hezbollah captured two Israeli soldiers along the border, sparking a 34-day war. The Israeli air campaign and ground operation aimed at degrading Hezbollah resulted in widespread damage to Lebanon's civilian infrastructure, killing roughly 1,190 Lebanese, and displacing a quarter of Lebanon's population.5 In turn, Hezbollah launched thousands of rockets into Israel, killing 163 Israelis.6 U.N. Security Council Resolution 1701 brokered a cease-fire between the two sides.

2008 Doha Agreement. In late 2006, a move by the Lebanese government to endorse the STL led Hezbollah and its political ally Amal to withdraw from the government, triggering an 18-month political crisis. In May 2008, a cabinet decision to shut down Hezbollah's private telecommunications network—which the group reportedly viewed as critical to its ability to fight Israel—led Hezbollah fighters to seize control of parts of Beirut. The resulting sectarian violence raised questions regarding Lebanon's risk for renewed civil war, as well as concerns about the willingness of Hezbollah to deploy its militia force in response to a decision by Lebanon's civilian government. Qatar helped broker a political settlement between rival Lebanese factions, which was signed on May 21, 2008, and became known as the Doha Agreement.

War in Syria. In 2011, unrest broke out in neighboring Syria. Hezbollah moved to support the Asad regime, eventually mobilizing to fight inside Syria. Meanwhile, prominent Lebanese Sunni leaders sided with the Sunni rebels. As rebel forces fighting along the Lebanese border were defeated by the Syrian military—with Hezbollah assistance—rebels fell back, some into Lebanon. Syrian refugees also began to flood into the country. Beginning in 2013, a wave of retaliatory attacks targeting Shia communities and Hezbollah strongholds inside Lebanon threatened to destabilize the domestic political balance as each side accused the other of backing terrorism. The Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) and Hezbollah have both worked to contain border attacks by Syria-based groups such as the Islamic State and the Nusra Front.

Issues for Congress

U.S. policy in Lebanon has sought to limit threats posed by Hezbollah both domestically and to Israel, bolster Lebanon's ability to protect its borders, and build state capacity to deal with the refugee influx. At the same time, Iranian influence in Lebanon via its ties to Hezbollah, the potential for renewed armed conflict between Hezbollah and Israel, and Lebanon's internal political dynamics complicate the provision of U.S. assistance. Lebanon continues to be an arena for conflict between regional states, as local actors aligned with Syria and Iran vie for power against those that seek support from Saudi Arabia and the United States.

As Congress reviews aid to Lebanon, Members continue to debate the best ways to meet U.S. policy objectives:

- Weakening Hezbollah and building state capacity. The United States has sought to weaken Hezbollah over time, yet without provoking a direct confrontation with the group that could undermine Lebanon's stability. Obama Administration officials argued that U.S. assistance to the Lebanese Armed Forces is essential to building the capability of the LAF to serve as the sole legitimate guarantor of security in Lebanon, and to counter the role of Hezbollah and Iran.7 However, some Members argued that Hezbollah has increased cooperation with the LAF, and questioned the Obama Administration's request for continuing Foreign Military Financing (FMF) assistance to Lebanon.8 Adjacent Hezbollah and LAF operations along the Syrian border in mid-2017 against Islamic State and Al Qaeda-affiliated militants raised additional questions about de-confliction and coordination between the military and Hezbollah fighters.

- Defending Lebanon's borders. Beginning in late 2012, Lebanon faced a wave of attacks from Syria-based groups, some of which sought to gain a foothold in Lebanon. U.S. policymakers have sought to ensure that the Lebanese Armed Forces have the tools they need to defend Lebanon's borders against encroachment by the Islamic State and other armed nonstate groups.

- Assisting Syrian refugees. While seeking to protect Lebanon's borders from infiltration by the Islamic State and other terrorist groups, the United States also has called for Lebanon to keep its border open to Syrian refugees fleeing violence. The United States has provided more than $1.5 billion in humanitarian aid to Lebanon since FY2012,9 much of it designed to lessen the impact of the refugee surge on host communities.

- Strengthening government institutions. U.S. economic aid to Lebanon aims to strengthen Lebanese institutions and their capacity to provide essential public services. Slow economic growth and high levels of public debt have limited government spending on basic public services, and this gap has been filled in part by sectarian patronage networks, including some affiliated with Hezbollah. U.S. programs to improve education, increase service provision, and foster economic growth are intended to make communities less vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups.

Politics

Lebanon is a parliamentary republic. The confessional political system established by the 1943 National Pact and formalized by the 1989 Taif Accords divides power among Lebanon's three largest religious communities (Christian, Sunni, Shia) in a manner designed to prevent any one group from dominating the others. Major decisions can only be reached through consensus, setting the stage for prolonged political deadlock.

2018 Legislative Elections

Lebanon was due for parliamentary elections in 2013. However, disagreements over the details of a new electoral law (passed in June 2017) delayed the elections until May 6, 2018.

The results of the May elections gave parties allied with Hezbollah an increase in their share of seats from roughly 44% to 53%. The political coalition known as March 8, which includes Hezbollah, the Shia Amal Movement, the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) and allied parties, won 68 seats according to Lebanese vote tallies.10 This is enough to secure a simple majority (65 out of 128 seats) in parliament, but falls short of the two-thirds majority needed to push through major initiatives such as a revision to the constitution. Hezbollah itself did not gain any additional seats.

The rival March 14 coalition (which includes the Sunni Future Movement, the Maronite Lebanese Forces, and allied MPs) lost 10 seats. Prime Minister Hariri's Future Movement absorbed the largest loss (roughly a third of its seats) but remains the largest Sunni bloc in parliament. The Lebanese Forces party was among the largest winners, increasing its share of seats from 8 to 14. For additional information, see CRS Insight IN10900, Lebanon's 2018 Elections, by [author name scrubbed].

Government Formation

The conclusion of legislative elections clears the way for the formation of a new government, in the shape of a new cabinet. Known formally as the Council of Ministers, the cabinet is comprised of 30 ministerial posts, currently distributed among 10 parties. On May 24, President Aoun reappointed Saad Hariri as prime minister and charged him with forming a new government. This will be Hariri's third term as prime minister (he previously served from 2009 to 2011 and 2016 to 2018). Hariri is expected to hold consultations with political blocs to form a cabinet, and present those ministers to the president for his approval.

Hezbollah has held either one or two seats in each of the six Lebanese governments formed since July 2005, complicating U.S. engagement with successive Lebanese administrations. In mid-May 2018, the United States imposed additional sanctions on Hezbollah officials, and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorist Financing Marshall Billingslea told the Lebanese newspaper Daily Star that, "We are gravely concerned by the role that Hezbollah is trying to play in the government and I would urge extreme caution for any future government for the inclusion of this terrorist group in the political system."11 It is unclear whether U.S. preferences will affect government formation. In response to a question about whether Hezbollah would be excluded from the new government, Hariri stated, "When we are talking about a government that [ensures] agreement in the country [then] it [will include] everyone."12

|

Hariri's Temporary Resignation In November 2017, Prime Minister Hariri unexpectedly announced his resignation during a visit to Saudi Arabia, issuing a statement condemning the role of Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon. The move was widely viewed as orchestrated by Riyadh, which has sought to isolate Iran and Hezbollah in the region.13 Lebanese President Michel Aoun stated that he would not accept Hariri's resignation or begin the process of forming a new government until the prime minister returned to Lebanon. Lebanese from across the political spectrum also called for the return of the prime minister, and criticized Saudi Arabia for what many viewed as undue influence in Lebanese internal affairs. Hariri withdrew his resignation a month later, upon his return to Lebanon. The Lebanese cabinet unanimously endorsed a policy statement calling on all Lebanese groups, including Hezbollah, to recommit to the policy of dissociation from regional conflicts (as established by the 2012 Baabda Declaration.) Since then, Hariri has sought to repair his relationship with Saudi Arabia, and visited the kingdom in March 2018. |

2016 Presidential Election

On October 31, 2016, Lebanon's parliament elected Christian leader and former LAF commander Michel Aoun [pronounced AWN] as president, filling a post that had stood vacant since the term of former President Michel Sleiman expired in May 2014. More than 40 attempts by the parliament to convene an electoral session had previously failed, largely due to boycotts by various parties that prevented the body from attaining the necessary quorum for the vote.14 Those most frequently boycotting sessions were MPs allied with the FPM and Hezbollah.15

In addition to creating an electoral stalemate, boycotts had also prevented parliament from attaining the necessary quorum to convene regular legislative sessions, effectively paralyzing many functions of the central government. In 2015, the country saw mass protests over the government's failure to collect garbage. Over the past two years, some parties have used legislative boycotts as a way to block the consideration of controversial issues, such as the proposal for a new electoral law.

The election of a president in 2016 was made possible in part by a decision by Future Movement leader Saad Hariri—head of the largest single component of the March 14 coalition—to shift his support from presidential candidate Suleiman Franjieh to Michel Aoun, giving Aoun the votes necessary to secure his election. In return, Aoun was expected to appoint Hariri as prime minister. In December 2016, a new 30-member cabinet was announced, headed by Hariri.

Aoun is a former military officer and a long-standing fixture of the Lebanese political scene. Founder of the Maronite Christian Free Patriotic Movement, he has been allied with Hezbollah since 2005. At the same time, he represents a Christian community which views Hezbollah's interference in Syria as endangering Lebanese stability.

|

Figure 2. Lebanon's Political Coalitions Reflects those parties with the largest number of seats in Parliament |

|

Evolution of March 8 and March 14 Political Coalitions

Many observers and Lebanese political leaders contend that the alliances that previously defined March 8 and March 14 have evolved since the formation of the two coalitions in 2005, with some arguing that the coalitions—particularly March 14—are weakened or defunct. However, the broad contours of March 8 and March 14 may still impact government formation.

Security Challenges

Lebanon faces numerous security challenges from a combination of internal and external sources. Some of these stem from the conflict in neighboring Syria, while others are rooted in long-standing social divisions and the marginalization of some sectors of Lebanese society. The Syria conflict appears to have exacerbated some of the societal cleavages.

According to the State Department's 2016 Country Reports on Terrorism (released in July 2017), Lebanon remains a safe haven for certain terrorist groups:

The Lebanese government did not take significant action to disarm Hizballah or eliminate its safe havens on Lebanese territory, nor did it seek to limit Hizballah's travel to and from Syria to fight in support of the Assad regime or to and from Iraq. The Lebanese government did not have complete control of all regions of the country, or fully control its borders with Syria and Israel. Hizballah controlled access to parts of the country and had influence over some elements within Lebanon's security services, which allowed it to operate with relative impunity.16

The report also noted that in 2016, ungoverned areas along Lebanon's border with Syria served as safe havens for extremists groups such as the Islamic State and the Al Qaeda-linked Syrian militants (such as the Nusra Front, part of which evolved into Ha'ia Tahrir al Sham, or HTS). In mid-2017 both the LAF and Hezbollah carried out operations aimed at clearing the border area of Islamic State and HTS forces (see "2017 Border Operations," below).

Spillover from Syria Conflict

Despite the Lebanese government's official policy of disassociation from the war in neighboring Syria, segments of Lebanese society have participated to varying degrees in the conflict, resulting in a range of security repercussions for the Lebanese state.

In May 2013, Hezbollah leader Hasan Nasrallah publicly announced Hezbollah's military involvement in the Syria conflict in support of the Asad government. In July 2013, Nusra Front leader Abu Muhammad Al Jawlani warned that Hezbollah's actions in Syria "will not go unpunished."17 In December 2013, a group calling itself the Nusra Front in Lebanon released its first statement. The group claimed responsibility for a number of suicide attacks in Lebanon, which it described as retaliation for Hezbollah's involvement in Syria.18

The Islamic State has also conducted operations inside Lebanon targeting Shia Muslims and Hezbollah. In November 2015, the Islamic State claimed responsibility for twin suicide bombings in the Beirut suburb of Burj al Barajneh—a majority Shia area. The attack killed at least 43 and wounded more than 200.19 As a result of the targeting of Shia areas, Hezbollah has worked in parallel to the Lebanese Armed Forces to counter the Nusra Front and the Islamic State in Lebanon. In 2016, U.S. defense officials described the relationship between Hezbollah and the LAF as one of "de-confliction."20

While Hezbollah backed the Asad government, sympathy for the largely Sunni Syrian opposition was widespread among Lebanon's Sunni community. Some areas of Lebanon's border region became an enclave for armed groups. In 2013, fighting in the Qalamoun mountain region located between Syria and Lebanon transformed the Lebanese border town of Arsal into a rear base for Syrian armed groups.21

In August 2014, clashes broke out between the LAF and Islamic State/Nusra Front militants in Arsal. Nineteen LAF personnel and 40 to 45 Lebanese and Syrians were killed, and 29 LAF and Internal Security Forces were taken hostage.22 It was generally believed that nine of the hostages were still being held by the Islamic State, until the location of their remains was disclosed as part of an August 2017 cease-fire arrangement with the group. U.S. officials described the August 2014 clashes between the Islamic State and the LAF in Arsal as a watershed moment for U.S. policy toward Lebanon, accelerating the provision of equipment and training to the LAF.23 The situation in Arsal was compounded by the refugee crisis—by 2016, the border town hosted more than 40,000 refugees, exceeding the Lebanese host population by more than 15%.24

Security Issues and Antirefugee Sentiment

Some Lebanese have described the country's growing Syrian refugee population as a risk to Lebanon's security. In June 2016, eight suicide bombers attacked the Christian town of Al Qaa near the Syrian border, killing five and wounding dozens. The attack heightened antirefugee sentiment, as the attackers were initially suspected to be Syrians living in informal refugee settlements inside the town. Lebanese authorities arrested hundreds of Syrians following the attack, although Lebanon's interior minister later stated that seven out of the eight bombers had traveled to Lebanon from the Islamic State's self-declared capital in Raqqah, Syria, and were not residing in Lebanon.25

In June 2017, five suicide bombers struck two refugee settlements in Arsal, killing a child and wounding three LAF soldiers. The attacks came during an LAF raid against IS militants thought to be hiding in the area. In the wake of the attacks, the LAF detained some 350 people, including several alleged IS officials.26 Four Syrian detainees died in LAF custody, drawing criticism from Syrian opposition groups and human rights organizations. A Lebanese military prosecutor ordered an investigation into the deaths. Following the attack, Hezbollah released a statement supporting LAF operations around Arsal and calling for "coordinated efforts" to prevent terrorist infiltration across Lebanon's eastern border.27 In a cabinet meeting on July 5, President Aoun praised LAF efforts to combat terrorism and warned that Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon were turning into "enabling environments for terrorism."28

Some Lebanese officials continue to describe the country's Syrian refugee population as destabilizing, and argue that Syrian refugees should return home. In May 2018, President Aoun reiterated his call for the repatriation of Syrian refugees, stating that their return would "end the repercussions of this displacement on Lebanon socially, economically, educationally, and in terms of security."29 Aoun has said that the return of refugees should not be contingent on a political solution to the Syrian conflict.30 However, Prime Minister Hariri has stated that Lebanon will not force Syrian refugees to return to Syria.31

For additional details on the refugee situation in Lebanon, see "Syrian and Palestinian Refugees and Lebanese Policy."

2017 Border Operations

In an effort to counter the infiltration of militants from Syria, both the LAF and Hezbollah have deployed forces at various points along Lebanon's eastern border. In May 2017, Hezbollah withdrew from a 67 km area stretching from the Masnaa border crossing with Syria (the primary official land crossing between the two countries) to Arsal, and was replaced by LAF forces.32 In July 2017, Hezbollah launched an operation to clear HTS militants from Arsal. In August, the LAF conducted a separate operation to clear Islamic State militants from border areas north of Arsal. Hezbollah's role in operations along Lebanon's eastern border has been controversial, with some Lebanese politicians arguing that the job of clearing militants from the area should rest with the Lebanese government alone.33

Hezbollah Offensive Near Arsal

In late July 2017, Hezbollah began operations around Arsal. Within days, Nasrallah announced that Hezbollah had retaken most of the territory held by HTS. On July 27, a cease-fire was announced between Hezbollah and HTS fighters, brokered by Lebanon's Chief of General Security.34 As part of the agreement, HTS fighters agreed to relocate with their families to Syria's Idlib province. Nasrallah stated that "we will be ready to hand all the recaptured Lebanese lands and positions over to the Lebanese Army if the army command requests this and is ready to take responsibility for them."35 Prime Minister Hariri said that the LAF did not participate in Hezbollah's operations around Arsal.36 However, in a public address, Nasrallah stated that the LAF secured the area to the west of Arsal to ensure that HTS militants along the border did not escape into Lebanon.37 Praising the role of the LAF in the July Arsal operation, Nasrallah stated, "What the Lebanese Army did around Aarsal, on the outskirts of Aarsal, and along the contact line within the Lebanese territories was essential for scoring this victory."38 It is unclear whether Nasrallah's praise of the LAF is intended in part to complicate the LAF's relationship with international partners, including the United States.

LAF Border Operation Against the Islamic State

In August 2017, the Lebanese government launched a 10-day offensive to clear Islamic State militants from the outskirts of the towns of Ras Baalbeck and Al Qaa, north of Arsal along Lebanon's northeast border. According to media reports, the LAF operation occurred in conjunction with a separate but simultaneous attack on the militants by Syrian government and Hezbollah forces from the Syrian side of the border, trapping the militants in a small enclave.39 On August 30, LAF Commander General Joseph Aoun declared the operation, which resulted in the deaths of seven LAF soldiers and dozens of IS fighters, complete.40 In a phone call with CENTCOM Commander General Votel, General Aoun "confirmed that the U.S. aid provided to the LAF had an efficient and main role in the success of this operation."41

The conclusion of the operation also involved an agreement to allow the roughly 300 IS fighters to withdraw from their besieged enclave along with their families, and head to IS-controlled Abu Kamal on the Syrian border with Iraq. In return, the Islamic State revealed the location of the remains of nine LAF soldiers captured in 2014, as well as the bodies of five Hezbollah fighters.42

Domestic Sunni Extremism

Since the start of the Syria conflict, some existing extremist groups in Lebanon who previously targeted Israel refocused on Hezbollah and Shia communities. The Al Qaeda-linked Abdallah Azzam Brigades (AAB), formed in 2009, initially targeted Israel with rocket attacks. However, the group began targeting Hezbollah in 2013 and is believed to be responsible for a series of bombings in Hezbollah-controlled areas of Beirut, including a November 2013 attack against the Iranian Embassy that killed 23 and wounded at least 150.43

In addition to the AAB, there are numerous Sunni extremist groups based in Lebanon that predate the Syria conflict. These include Hamas, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Fatah al Islam, and Jund al Sham. These groups operate primarily out of Lebanon's 12 Palestinian refugee camps. Due to an agreement between the Lebanese government and the late Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) chairman Yasser Arafat, Lebanese forces generally do not enter Palestinian camps in Lebanon, instead maintaining checkpoints outside them. These camps operate as self-governed entities, and maintain their own security and militia forces outside of government control.44

Hezbollah

Lebanese Hezbollah, a Shia Islamist movement, is Iran's most significant nonstate ally. Iran's support for Hezbollah, including providing thousands of rockets and short-range missiles, helps Iran acquire leverage against key regional adversaries such as Israel and Saudi Arabia. It also facilitates Iran's intervention on behalf of a key ally, the Asad regime in Syria. The Asad regime has been pivotal to Iran and Hezbollah by providing Iran a secure route to deliver weapons to Hezbollah. Iran has supported Hezbollah through the provision of "hundreds of millions of dollars" to the group, in addition to training "thousands" of Hezbollah fighters inside Iran.45 In June 2018, Treasury Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Sigal Mandelker estimated that Iran provides Hezbollah with more than $700 million per year,46 significantly more than previously released U.S. government estimates.47

Clashes with Israel

Hezbollah emerged in the early 1980s during the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon. Israel invaded Lebanon in 1978 and again in 1982, with the goal of pushing back (in 1978) or expelling (in 1982) the leadership and fighters of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)—which used Lebanon as a base to wage a guerrilla war against Israel until the PLO's relocation to Tunisia in 1982.48 In 1985 Israel withdrew from Beirut and its environs to southern Lebanon—a predominantly Shia area. Shia leaders disagreed about how to respond to the Israeli occupation, and many of those favoring a military response gradually coalesced into what would become Hezbollah.49 The group launched attacks against Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and U.S. military and diplomatic targets, portraying itself as the leaders of resistance to foreign military occupation.

In May 2000, Israel withdrew its forces from southern Lebanon, but Hezbollah has used the remaining Israeli presence in the Sheb'a Farms (see below) and other disputed areas in the Lebanon-Syria-Israel triborder region to justify its ongoing conflict with Israel—and its continued existence as an armed militia alongside the Lebanese Armed Forces.

|

The Sheb'a Farms Dispute When Israel withdrew from southern Lebanon in 2000, several small but sensitive territorial issues were left unresolved, notably, a roughly 10-square-mile enclave at the southern edge of the Lebanese-Syrian border known as the Sheb'a Farms. Israel did not evacuate this enclave, arguing that it is not Lebanese territory but rather is part of the Syrian Golan Heights, which Israel occupied in 1967. Lebanon, supported by Syria, asserts that this territory is part of Lebanon and should have been evacuated by Israel when the latter abandoned its self-declared security zone in May 2000. Ambiguity surrounding the demarcation of the Lebanese-Syria border has complicated the task of determining ownership over the area. France, which held mandates for both Lebanon and Syria, did not define a formal boundary between the two, although it did separate them by administrative divisions. Nor did Lebanon and Syria establish a formal boundary after gaining independence from France in the aftermath of World War II—in part due to the influence of some factions in both Syria and Lebanon who regarded the two as properly constituting a single country. Advocates of a "Greater Syria" in particular were reluctant to establish diplomatic relations and boundaries, fearing that such steps would imply formal recognition of the separate status of the two states. The U.N. Secretary General noted in May 2000 that "there seems to be no official record of a formal international boundary agreement between Lebanon and the Syrian Arab Republic."50 Syria and Lebanon did not establish full diplomatic relations until 2008.51 |

2006 Hezbollah-Israel War

Hezbollah's last major clash with Israel occurred in 2006—a 34-day war that resulted in the deaths of approximately 1,190 Lebanese and 163 Israelis,52 and the destruction of large parts of Lebanon's civilian infrastructure. The war began in July 2006, when Hezbollah captured two members of the IDF along the Lebanese-Israeli border. Israel responded by carrying out air strikes against suspected Hezbollah targets in Lebanon, and Hezbollah countered with rocket attacks against cities and towns in northern Israel. Israel subsequently launched a full-scale ground operation in Lebanon with the stated goal of establishing a security zone free of Hezbollah militants. Hostilities ended following the issuance of U.N. Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1701, which imposed a cease-fire.

In the years since the 2006 war, Israeli officials have sought to draw attention to Hezbollah's weapons buildup—including reported upgrades to the range and precision of its projectiles—and its alleged use of Lebanese civilian areas as strongholds.53 In addition, Israel has reportedly struck targets in Syria or Lebanon in attempts to prevent arms transfers to Hezbollah in Lebanon.54 In February 2016, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu said the following:

We will not agree to the supply of advanced weaponry to Hezbollah from Syria and Lebanon. We will not agree to the creation of a second terror front on the Golan Heights. These are the red lines that we have set and they remain the red lines of the State of Israel.55

Some media reporting in 2017 has focused on claims that Iran has helped Hezbollah set up underground factories in Lebanon to manufacture weapons previously only available from outside the country.56 In August 2017, the former commander of the Israel Air Force (IAF) claimed that Israel had hit convoys of weapons headed to Hezbollah almost 100 times since civil war broke out in Syria in 2012.57 In September 2017, the IAF allegedly struck an area in northwestern Syria—reportedly targeting a Syrian chemical weapons facility58 and/or a factory producing precision weapons transportable to Hezbollah.59 In October, the IAF acknowledged striking a Syrian antiaircraft battery that apparently targeted Israeli aircraft flying over Lebanon.60 Russia's actions could affect future Israeli operations, given that it maintains advanced air defense systems and other interests in Syria.

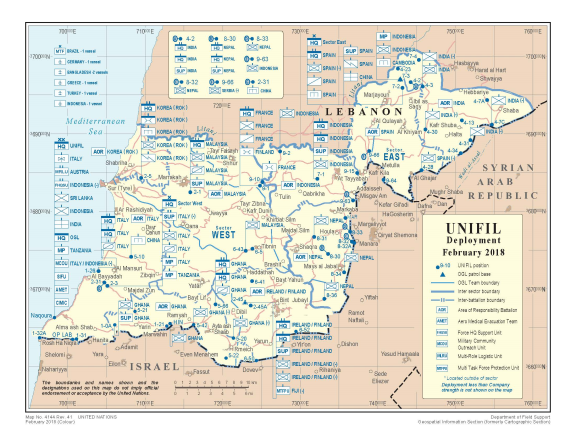

United Nations Force in Lebanon

Since 1978, the United Nations Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) has been deployed in the Lebanon-Israel-Syria triborder area.61 UNIFIL's initial mandate was to confirm the withdrawal of Israeli forces from southern Lebanon, restore peace and security, and assist the Lebanese government in restoring its authority in southern Lebanon (a traditional Hezbollah stronghold). In May 2000, Israel withdrew its forces from southern Lebanon. The following month, the United Nations identified a 120 km line between Lebanon and Israel to use as a reference for the purpose of confirming the withdrawal of Israeli forces. The Line of Withdrawal, commonly known as the Blue Line, is not an international border demarcation between the two states.

Following the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war, UNIFIL's mandate was expanded via UNSCR 1701 (2006) to including monitoring the cessation of hostilities between the two sides, accompanying and supporting the Lebanese Armed Forces as they deployed throughout southern Lebanon, and helping to ensure humanitarian access to civilian populations. UNSCR 1701 also authorized UNIFIL to assist the Lebanese government in the establishment of "an area free of any armed personnel, assets and weapons other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL" between the Blue Line and the Litani River. In 2007, Israel and Lebanon agreed to visibly mark the Blue Line on the ground. As of July 2017, UNIFIL has measured 282 points along the Blue Line and constructed 268 Blue Line Barrels as markers.62

UNIFIL is headquartered in the Lebanese town of Naqoura and maintains more than 10,500 peacekeepers drawn from 40 countries.63 This includes more than 9,600 ground troops and over 850 naval personnel of the Maritime Task Force. U.S. personnel do not participate in UNIFIL, although U.S. contributions to U.N. peacekeeping programs support the mission. The United States provides security assistance to the Lebanese Armed Forces aimed at supporting Lebanese government efforts to implement UNSCR 1701.

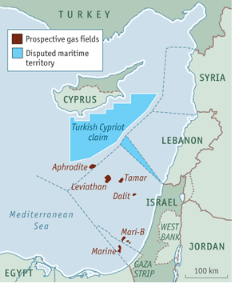

Since the discovery in 2009 of large offshore gas fields in the Mediterranean, unresolved issues over the demarcation of Lebanon's land border with Israel have translated into disputes over maritime boundaries, and in 2011 Lebanese authorities called on the U.N. to establish a maritime equivalent of the Blue Line. UNIFIL has maintained a Maritime Task Force since 2006, which assists the Lebanese Navy in preventing the entry of unauthorized arms or other materials to Lebanon. However, U.N. officials have stated that UNIFIL does not have the authority to establish a maritime boundary.64 (For more information, see "Eastern Mediterranean Energy Resources and Disputed Boundaries," below.)

UNIFIL continues to monitor violations of UNSCR 1701 by all sides, and the U.N. Secretary General reports regularly to the U.N. Security Council on the implementation of UNSCR 1701. These reports have listed violations by Hezbollah—including an April 2017 media tour along the Israeli border—as well as violations by Israel—including "almost daily" violations of Lebanese airspace.65

In January 2017, UNIFIL underwent a strategic review. The scope of the review did not include the mandate of the mission or its authorized maximum strength of 15,000 troops. In March, the results of the strategic review were presented to the Security Council. The review found that "overall, the Force was well configured to implement its mandated tasks," and also outlined a number of recommendations.66

On August 30, 2017, the U.N. Security Council voted to renew UNIFIL's mandate for another year. The vote followed what U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Nikki Haley described as "tense negotiations" over the mission's mandate,67 with the United States and Israel reportedly pushing for changes that would allow UNIFIL to access and search private property for illicit Hezbollah weapons stockpiles or other violations of UNSCR 1701.68 Ambassador Haley has been critical of UNIFIL, which she argues has failed to prevent Hezbollah violations of UNSCR 1701 and whose patrols in southern Lebanon are sometimes restricted by roadblocks.69

Changes to UNIFIL's mandate were opposed by countries contributing troops to the mission, including France and Italy.70 Lebanon's Foreign Minister also called on the Security Council to renew the mission's mandate without change. Other critics of the proposed changes questioned whether troop-contributing countries would be willing to deploy forces for a mission that could require direct confrontation with Hezbollah in heavily Shia areas of southern Lebanon.71

The renewal of UNIFIL's mandate in UNSCR 2373 included limited wording changes, which were praised by all sides.72 The new language requests that the existing U.N. Secretary General's reports on the implementation of UNSCR 1701 include, among other things, "prompt and detailed reports on the restrictions to UNIFIL's freedom of movement, reports on specific areas where UNIFIL does not access and on the reasons behind these restrictions."73

|

Figure 3. United Nations Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) Deployment and Lebanon-Syria-Israel Triborder Area |

|

|

Source: U.N. Geospatial Information Section. |

Domestic Politics

Hezbollah was widely credited for forcing the withdrawal of Israeli troops from southern Lebanon in 2000, and this elevated the group into the primary political party among Lebanese Shia.74 In addition, Hezbollah—like other Lebanese confessional groups—vies for the loyalties of its constituents by operating a vast network of schools, clinics, youth programs, private business, and local security. These services contribute significantly to the group's popular support base, although some Lebanese criticize Hezbollah's vast apparatus as "a state within the state." The legitimacy that this popular support provides compounds the challenges of limiting Hezbollah's influence.

Hezbollah has participated in elections since 1992, and it has achieved a modest but steady degree of electoral success. Hezbollah entered the cabinet for the first time in 2005, and has held one or two seats in each of the six Lebanese governments formed since then. Hezbollah candidates have also fared well in municipal elections, winning seats in conjunction with allied Amal party representatives in many areas of southern and eastern Lebanon.

On May 6, 2018, Lebanon held its first legislative elections in nine years. The results showed that parties allied with Hezbollah increased their share of seats from roughly 44% to 53%. The political coalition known as March 8 (see Figure 2), which includes Hezbollah, Amal, the FPM, and allied parties, won 68 seats according to Lebanese vote tallies.75 This is enough to secure a simple majority (65 out of 128 seats) in parliament, but falls short of the two-thirds majority needed to push through major initiatives such as a revision to the constitution. Hezbollah itself did not gain any additional seats. For additional details on the May 2018 elections, see CRS Insight IN10900, Lebanon's 2018 Elections, by [author name scrubbed].

Hezbollah has at times served as a destabilizing political force, despite its willingness to engage in electoral politics. In 2008, Hezbollah-led fighters took over areas of Beirut after the March 14 government attempted to shut down the group's private telecommunications network—which Hezbollah leaders described as key to the group's operations against Israel.76 Hezbollah has also withdrawn its ministers from the cabinet to protest steps taken by the government (in 2008 when the government sought to debate the issue of Hezbollah's weapons, and in 2011 to protest the expected indictments of Hezbollah members for the Hariri assassination). On both occasions, the withdrawal of Hezbollah and its political allies from the cabinet caused the government to collapse. At other times, Hezbollah leaders have avoided conflict with other domestic actors, possibly in order to focus its resources elsewhere—such as on activities in Syria.

Top Lebanese leaders have acknowledged that despite their differences with Hezbollah, they do confer with the group on issues deemed to be critical to Lebanon's security. In July 2017, Prime Minister Saad Hariri stated that although he disagreed with Hezbollah on politics,

when it comes for the sake of the country, for the economy, how to handle those 1.5 million refugees, how to handle the stability, how to handle the governing our country, we have to have some kind of understanding, otherwise we would be like Syria. So, for the sake of the stability of Lebanon, we agree on certain things, and we disagree on political issues that we—until today, we disagree. So, …there is an understanding or a consensus in the country, with all political parties including the president, [and it] is how to safeguard Lebanon.77

Intervention in Syria

Syria is important to Hezbollah because it serves as a key transshipment point for Iranian weapons. Following Hezbollah's 2006 war with Israel, the group worked to rebuild its weapons cache with Iranian assistance, a process facilitated or at minimum tolerated by the Syrian regime. While Hezbollah's relationship with Syria is more pragmatic than ideological, it is likely that Hezbollah views the prospect of regime change in Damascus as a fundamental threat to its interests—particularly if the change empowers Sunni groups allied with Saudi Arabia.

Hezbollah has played a key role in helping to suppress the Syrian uprising, in part by "advising the Syrian Government and training its personnel in how to prosecute a counter insurgency."78 Hezbollah fighters in Syria have worked with the Syrian military to protect regime supply lines, and to monitor and target rebel positions. They also have facilitated the training of Syrian forces by the IRGC-QF.79 The involvement of Hezbollah in the Syrian conflict has evolved since 2011 from an advisory to an operational role, with forces fighting alongside Syrian troops—most recently around Aleppo.80 The International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated in 2016 that Hezbollah maintains between 4,000 and 8,000 fighters in Syria.81 In mid-September, Nasrallah declared that "we have won the war (in Syria)" and described the remaining fighting as "scattered battles."82

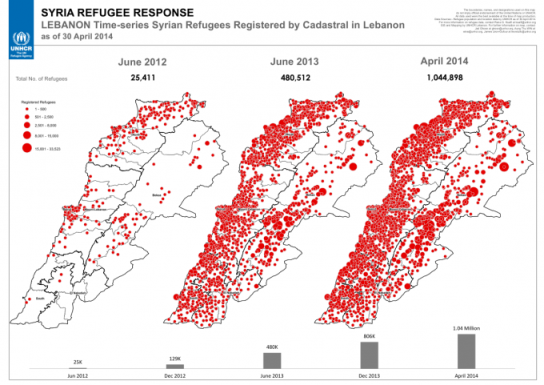

Syrian and Palestinian Refugees and Lebanese Policy

Refugees began to stream into Lebanon in 2011, following the outbreak of conflict in neighboring Syria. Initially, Lebanon maintained an open-border policy, permitting refugees to enter without a visa and to renew their residency for a nominal fee. By 2014, Lebanon had the highest per capita refugee population in the world, with refugees equaling one-quarter of the resident population.83 (See Figure 4.) In May 2015, UNHCR suspended new registration of refugees in response to the government's request. Thus, while roughly 1 million Syrian refugees were registered with UNHCR in late 2016, officials estimate that the actual refugee presence is closer to 1.2 million to 1.5 million (Lebanon's prewar population was about 4.3 million).

In addition, there are 450,000 Palestinian refugees registered with the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in Lebanon, although not all of those registered reside in Lebanon. A 2017 census of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon found that roughly 174,422 Palestinians live in 12 formal camps and 156 informal "gatherings."84 About 20,725 other refugees and asylum seekers are registered in Lebanon; 84% of these are Iraqi refugees.85

As the number of refugees continued to increase, it severely strained Lebanon's infrastructure, which was still being rebuilt following the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. It also created growing resentment among Lebanese residents, as housing prices increased and some felt as though an influx of cheap Syrian labor was displacing Lebanese from their jobs. The influx has also affected the Lebanese education system, as roughly 500,000 of the Syrian refugees in Lebanon are estimated to be school-age children.86

|

|

Source: UNHCR, accessed through reliefweb.int. |

The Lebanese government has been unwilling to take steps that it sees as enabling Syrians to become a permanent refugee population akin to the Palestinians—whose militarization in the 1970s was one of the drivers of Lebanon's 15-year civil war. Some Christian leaders also fear that the influx of largely Sunni refugees could upset the country's sectarian balance. The government has blocked the construction of refugee camps like those built to house Syrian refugees in Jordan and Turkey, presumably to prevent Syrian refugees from settling in Lebanon permanently. As a result, most Syrian refugees in Lebanon have settled in urban areas, in what UNCHR describes as "sub-standard shelters" (garages, worksites, unfinished buildings) or apartments. Less than 20% live in informal tented settlements. Syrian refugees have also settled in existing Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, and in some cases outnumber the Palestinian residents of those camps.87

Entry Restrictions. In May 2014, the government enacted entry restrictions effectively closing the border to Palestinian refugees from Syria.88 In January 2015, the Lebanese government began to implement new visa requirements for all Syrians entering Lebanon, raising concerns among U.S. officials.89 Under the new requirements, Syrians can only be admitted if they are able to provide documentation proving that they fit into one of the seven approved categories for entry, which do not include fleeing violence.90 While there is an entry category for displaced persons, the criteria specifically apply to "unaccompanied and/or separated children with a parent already registered in Lebanon; persons living with disabilities with a relative already registered in Lebanon; persons with urgent medical needs for whom treatment in Syria is unavailable; persons who will be resettled to third countries."91

Legal Status. Refugees registered with UNHCR are required to provide a notarized pledge not to work, as a condition of renewing their residency. Nevertheless, the January 2015 regulations increased the costs of residency renewal to an annual fee of $200 per person over 15 years of age, beyond the means of the 70% of Syrian refugee households living at or below the poverty line. As a result, most Syrian refugees in Lebanon lost their legal status. To survive, many sought employment in the informal labor market. According to a Human Rights Watch report, the loss of legal status for refugees in Lebanon made them vulnerable to labor and sexual exploitation by employers.92 In February 2017, Lebanese authorities lifted the $200 residency fee for Syrian refugees registered with UNHCR. The waiver will not apply to the estimated 500,000 Syrian refugees who arrived after the Lebanese government directed UNHCR to stop registering refugees in May 2015, or to refugees who renewed their residency through a Lebanese sponsor.93

Palestinian Refugees. Palestinian refugees have been present in Lebanon for at least 70 years, as a result of displacements stemming from various Arab-Israeli wars. Like Syrian refugees, Palestinian refugees and their Lebanese-born children cannot obtain Lebanese citizenship.94 Unlike Syrian refugees, Palestinian refugees are prohibited from accessing public health or other social services, and Palestinian children cannot attend Lebanese public schools.95 Palestinian refugees and their descendants cannot purchase or inherit property in Lebanon, and are barred from most skilled professions, including medicine, engineering, and law. As a result, many continue to depend on UNRWA for basic services.

In January 2018, the Trump Administration announced that it would withhold $65 million from UNRWA (about half of its anticipated tranche of funding). The Administration for the first time placed a geographic limitation on its UNRWA contribution, stating that the $60 million in voluntary contributions could only be used for eligible Palestinians registered in Gaza, Jordan, and the West Bank. Lebanon was not mentioned.96

The long-standing presence of Palestinians in Lebanon has shaped the approach of Lebanese authorities to the influx of Syrian refugees. It is unclear whether Lebanese authorities will take a comparable approach to the Syrian population over the long term, particularly as a new generation of Syrian children comes to share Palestinian refugees' status as stateless persons. Some observers worry that government policies limiting nationality, mobility, and employment for refugees and their descendants risk creating a permanent underclass vulnerable to recruitment by terrorist groups.

|

International Humanitarian Funding The U.N. Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP) is a coordinated regional framework designed to address the impact of the Syria crisis on the five most affected neighboring countries: Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Turkey, and Egypt. The 2018 3RP appeal seeks $3.5 billion and as of June 2018 was funded at 27%.97 The Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP) is nested within the broader 3RP, and targets not only the roughly 1.5 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon but also vulnerable Lebanese communities whose economic security has been adversely affected by the refugee influx. The LCRP also focuses on strengthening the stability of the Lebanese state and civil society. The 2018 LCRP was launched in February 2018 and seeks $2.68 billion. As of April it was funded at 9.4%.98 |

Return of Syrian Refugees

Since 2017, the LAF and the Directorate for General Security (DGS) have played a role in facilitating the return of several thousand refugees to Syria.99 As part of the arrangement, many refugees have been transferred to rebel-held portions of Syria's Idlib province, as well as to villages in the province of Rural Damascus. It is unclear whether all refugees departed voluntarily.100

The government's facilitation of refugee return has generated some tension between Lebanese officials and international humanitarian actors. In June 2018, a UNHCR spokesperson stated, "in our view, conditions in Syria are not yet conducive for an assisted return."101 Lebanese Foreign Minister Gibran Bassil has accused UNHCR of discouraging refugees from returning to Syria, and on June 8 ordered a freeze on the renewal of residency permits for UNHCR staff in Lebanon.102 UNHCR released a statement emphasizing, "we do not discourage returns that are based on individual free and informed decisions."103 The statement also noted that,

UNHCR is very concerned at Friday's announcement by Foreign Minister Bassil on freezing the issuance of residence permits to international staff of UNHCR in Lebanon. This affects our staff and their families and directly impacts UNHCR's ability to effectively carry out critical protection and solutions work in Lebanon.104

Economy and Fiscal Issues

Lebanon's economy is service oriented (69.5% of GDP), and primary sectors include banking and financial services as well as tourism. The country faces a number of economic challenges, including high unemployment and the third-highest debt-to-GDP ratio in the world (142%, 2017 est).105 In addition, the war in neighboring Syria has significantly affected Lebanon's traditional growth sectors—tourism, real estate, and construction. Economic growth has slowed from an average of 8% between 2007 and 2009 to 1% to 2% since the outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011 and the resulting refugee influx.106 Foreign direct investment fell 68% during the first year of the Syria conflict (from $3.5 billion to $1.1 billion),107 but reached $2.5 billion in 2016.108

The Lebanese government is unable to consistently provide basic services such as electricity, water, and waste treatment, and the World Bank notes that the quality and availability of basic public services is significantly worse in Lebanon than both regional and world averages.109 As a result, citizens rely on private providers, many of whom are affiliated with political parties. The retreat of the state from these basic functions has enabled a patronage network whereby citizens support political parties—including Hezbollah—in return for basic services.

Unresolved political dynamics have exacerbated Lebanon's economic and fiscal struggles. Between 2014 and 2016, when the office of the presidency remained unfilled, Lebanon lost international donor funding when parliamentary boycotts prevented the body from voting on key matters, including the ratification of loan agreements. In October 2017, Parliament voted to pass the budget—the first time since 2005 that a state budget has been approved.110

Lebanon's economy is also affected by fluctuations in the country's relationship to the Gulf states, which are a key source of tourism, foreign investment, and aid. In early 2016, Saudi Arabia suspended $3 billion in pledged aid to Lebanon's military after Lebanon's foreign minister declined to endorse an otherwise unanimous Arab League statement condemning attacks against Saudi diplomatic missions in Iran.111 Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states instituted a travel warning to Lebanon and urged their citizens to leave the country—impacting Lebanon's real estate and tourism sectors, which depend on spending by wealthy Gulf visitors. Lebanon's relationship with Saudi Arabia continues to fluctuate (see "Hariri's Temporary Resignation" above).

Despite these numerous challenges, the Central Bank of Lebanon under the leadership of long-serving Governor Riad Salameh has played a stabilizing role. The Central Bank maintains more than $43 billion in foreign reserves,112 and the Lebanese pound, which is pegged to the dollar, has remained stable. Despite sporadic violence targeting Lebanese banks, Salameh has supported the implementation of the Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act, which seeks to bar from the U.S. financial system any bank that knowingly engages with Hezbollah.

The Capital Investment Plan

At the CEDRE international donor conference, held in Paris in April 2018, Lebanese officials presented the Capital Investment Plan (CIP). The plan, which was endorsed by the Lebanese cabinet, seeks $20 billion in funding (in the form of public-private partnerships, grants, and concessional loans). The project would fund the rehabilitation and expansion of Lebanon's aging and overstretched infrastructure, although funding the project would significantly increase Lebanon's public debt.

The Paris CEDRE conference generated $11.8 billion, mainly in soft loans, with significant pledges from the World Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, the Islamic Development Bank, and others. Regional and Western states also pledged funding, including Saudi Arabia, France, Qatar, and the United States.113

Eastern Mediterranean Energy Resources and Disputed Boundaries

|

Figure 5. Eastern Mediterranean Maritime Territory Disputes and Energy Resources |

|

|

Source: The Economist. Notes: Boundaries and locations are approximate and not necessarily authoritative. |

In 2010, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that there are considerable undiscovered oil and gas resources that may be technically recoverable in the Levant Basin, an area that encompasses coastal areas of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Gaza, and Egypt and adjacent offshore waters.114 A 2018 report by Lebanon's Bank Audi estimated that Lebanon could generate over $200 billion in revenues from offshore gas exploration, with the potential to significantly reduce the country's debt to GDP ratio.115

However, maritime boundary disputes persist between Lebanon and Israel. The two states hold differing views of the correct delineation points for their joint maritime boundary relative to the Israel-Lebanon 1949 Armistice Line that serves as the de facto land border between the two countries.116 Lebanon objects to an Israeli-Cypriot agreement that draws a specific maritime border delineation point relative to the 1949 Israel-Lebanon Armistice Line and claims roughly 330 square miles of waters that overlap with areas claimed by Israel. Resolution of Israel-Lebanon disputes over the Armistice Line are further complicated by Israel's military presence in the Sheba'a Farms area claimed by Lebanon adjacent to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, captured from Syria in 1967.

After a three-year delay, Lebanon's Energy Ministry in January 2017 announced that it would auction energy-development rights to five offshore areas. The announcement followed the approval by the Lebanese cabinet of two decrees defining the exploration blocks and setting out conditions for tenders and contracts. In February 2018, Lebanon signed its first offshore oil and gas exploration agreement for two blocks, including one disputed by Israel. A consortium of Total (France), Eni (Italy), and Novatek (Russia) was awarded two licenses to explore blocks 4 and 9. Israel has disputed part of Block 9. Total has said that drilling, which will begin in 2019, will be more than 15 miles from the border claimed by Israel.

For additional information, see CRS Report R44591, Natural Gas Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean, by [author name scrubbed].

U.S. Policy

The United States has sought to bolster forces that could serve as a counterweight to Syrian and Iranian influence in Lebanon through a variety of military and economic assistance programs. U.S. security assistance priorities reflect increased concern about the potential for Sunni jihadist groups such as the Islamic State to target Lebanon, as well as long-standing U.S. concerns about Hezbollah and preserving Israel's qualitative military edge (QME). U.S. economic aid to Lebanon is designed to promote democracy, stability, and economic growth, particularly in light of the challenges posed by the ongoing conflict in neighboring Syria. Congress places several certification requirements on U.S. assistance funds for Lebanon annually in an effort to prevent their misuse or the transfer of U.S. equipment to Hezbollah or other designated terrorists. Hezbollah's participation in the Syria conflict on behalf of the Asad government is presumed to have strengthened the group's military capabilities and has increased concern among some in Congress over the continuation of U.S. assistance to the LAF.

Current Funding and the FY2019 Request

According to the FY2019 Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations, the executive branch obligated $208 million in assistance for Lebanon during 2017, including $110 million in Economic Support Fund (ESF) aid and $80 million in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) aid. President Trump's FY2018 budget request sought $103 million in total aid to Lebanon, mostly in economic aid ($85 million). The FY2018 appropriations act makes economic and military aid available for Lebanon on conditional terms, and the explanatory statement accompanying the act allocates $115 million in ESF for Lebanon.

FMF has been one of the primary sources of U.S. funding for the LAF, along with the Counter-ISIL Train and Equip Fund (CTEF). The FY2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-141) provides $1.8 billion for CTEF, some of which may be made available to enhance the border security of nations adjacent to conflict areas—including Lebanon. The act and explanatory statement also require the Administration to submit by September 1, 2018, a report on military assistance to Lebanon, including an assessment of the capability and performance of the LAF over time in strengthening border security and combatting terrorism, securing Lebanon's borders, interdicting arms shipments, preventing the use of Lebanon as a safe haven for terrorist groups, and implementing U.N. Security Council Resolution 1701.

The Administration's FY2019 aid request for Lebanon seeks $152 million in total funding, including $85 million in economic aid (ESDF) and $50 million in FMF.

Economic Aid

The influx of over 1 million Syrian refugees into Lebanon has strained the country's already weak infrastructure. Slow economic growth and high levels of public debt have limited government spending on basic public services, and this gap has been filled by various confessional groups affiliated with local politicians. In light of these challenges, U.S. programs are aimed at increasing the capacity of the public sector to provide basic services to both refugees and Lebanese host communities. This includes reliable access to potable water, sanitation, and health services. It also involves increasing the capacity of the public education system to cope with the refugee influx. Other U.S. programs are designed to foster inclusive economic growth, particularly among impoverished and underserved communities. This includes efforts to extend financial lending to small firms, create more jobs, and increase incomes. Taken together, these programs also aim to make communities less vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups.117

Military Aid

The United States has provided more than $1.7 billion to LAF since 2006.118 Following the legislative elections in early May, the State Department released a statement reiterating,

U.S. assistance for the LAF is a key component of our policy to reinforce Lebanon's sovereignty and secure its borders, counter internal threats, and build up its legitimate state institutions. Additionally, U.S. security assistance supports implementation of UN Security Council Resolutions 1559, 1680, and 1701, and promotes the LAF's ability to extend full governmental control throughout the country in conjunction with the UN Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL).119

In June 2018, the United States delivered four A-29 Super Tucano aircraft to the LAF, completing a delivery of six. U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon Elizabeth Richard noted that six MD-530G light attack helicopters would be forthcoming. The helicopters, valued at $94 million, were announced in December 2017 during the visit of U.S. Central Command Commander General Joseph Votel to Lebanon, together with an additional $27 million package that includes unmanned aerial vehicles and communications and electronic equipment.120

Since late 2014, the United States (in some cases using grants from Saudi Arabia) has also delivered Hellfire air-to-ground missiles, precision artillery, TOW-II missiles, M198 howitzers, small arms, and ammunition to Lebanon. Related U.S. training and advisory support is ongoing. The United States conducts annual bilateral military exercises with the LAF. Known as Resolute Response, these exercises include participants from the U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and Army. In June 2018, Ambassador Richard noted that the United States has trained over 32,000 Lebanese troops.121

In August 2017, a Pentagon spokesperson confirmed the presence of U.S. Special Operations Forces in Lebanon, which he described as providing training and support to the LAF.122 While he would not comment on the size of the contingent, some observers estimate that more than 70 Special Operations Command Central (SOCCENT) trainers and support personnel operate in Lebanon at any given time.123 According to a U.S. Army publication, U.S. Special Operations Forces have been deployed to Lebanon since at least 2012.124

U.S. assistance for border security improvements in Lebanon has drawn particular attention from Congress because of threats stemming from the conflict in Syria. As noted above, both Hezbollah and the LAF have deployed forces to the mountainous border area separating Lebanon and Syria in a bid to halt infiltrations. Longer-standing U.S. concerns about improving Lebanon's border control and security capabilities focus on stemming flows of weapons to Hezbollah and other armed groups in Lebanon, as called for by UNSCR 1701.

The FY2017 NDAA realigned CTPF funding to Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide, and made it available for a wide range of security cooperation activities. In FY2017, Lebanon received $42.9 million via CTPF-funded border security improvement programs authorized by Section 1226 of the FY2016 NDAA (P.L. 114-92). Under Section 1226, as amended, DOD may, with State Department concurrence, provide security assistance to the armed forces of Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and Tunisia in support of border security improvement efforts on their respective borders with Syria, Iraq, and Libya.

Table 1. Select U.S. Foreign Assistance Funding for Lebanon-Related Programs

$, millions, Fiscal Year of Appropriation unless noted

|

Account/Program |

FY2016 |

FY2017 Actual |

FY2018 Request |

FY2019 Request |

|

FMF |

- |

- |

- |

50 |

|

FMF-OCO |

85.9 |

80 |

- |

- |

|

ESF-OCO |

110 |

110 |

- |

- |

|

ESDF |

- |

- |

- |

85 |

|

ESDF-OCO |

- |

- |

85 |

- |

|

IMET |

2.79 |

2.6 |

2.75 |

2.75 |

|

INCLE |

10 |

- |

- |

6.2 |

|

INCLE-OCO |

10 |

10 |

6.25 |

- |

|

NADR |

4.76 |

- |

- |

8.8 |

|

NADR-OCO |

1.8 |

5.7 |

9.82 |

- |

Source: U.S. State Department FY2018 and FY2019 Budget Request Materials.

Notes: Table does not reflect all funds or programs related to Lebanon. Does not account for all reprogramming actions of prior year funds or obligation notices provided to congressional committees of jurisdiction. Some programs may be designed and implemented in ways that also meet non-IS related objectives.

FMF = Foreign Military Financing; ESF = Economic Support Fund; ESDF = Economic Support and Development Fund; IMET = International Military Education and Training; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs.

|

Authority or Appropriation Category |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

|

CTPF |

48,339 |

42,032 |

118,357 |

- |

|

10 U.S.C. 333 |

- |

- |

- |

110,445 |

Source: U.S. Defense Department Obligation Notifications to Congress, 2017-2018.

Notes: Figures provided by year of obligation/expenditure, as reported in the appendices of DOD obligation notifications to Congress. Figures for FY2017 and FY2018 are for notified amounts to Congress only. Since CTPF was only an authorized DOD appropriations account for FY2015-FY2016, CTPF funds listed in FY2017 are for funds appropriated in prior years. CTPF = Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund.

Funds include notifications for military and security force train and equip assistance as well as funds for border security enhancement authorized by Section 1226 of the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA P.L. 114-92), as amended. Section 1204 of the Senate version of the FY2019 NDAA (H.R. 5515 EAS) would extend and aim to clarify this authority with regard to Lebanon and other countries.

Recent Legislation

Annual appropriations bills have established conditions for ESF and security assistance for Lebanon. Most recently, Section 7041(e) of the 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-141) states that funding for the Lebanese Internal Security Forces (ISF) and the LAF may not be appropriated if either body is controlled by a U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organization. ESF funding for Lebanon may be made available notwithstanding Section 1224 of the FY2003 Foreign Relations Authorization Act, (P.L. 107-228), which states that ESF funds for Lebanon may not be obligated until the President certifies to the appropriate congressional committees that the LAF has been deployed to the Israeli-Lebanese border and that the government of Lebanon is effectively asserting its authority in the area in which the LAF is deployed. FMF assistance to the LAF may not be obligated until the Secretary of State submits to the appropriations committees a spend plan, including actions to be taken to ensure equipment provided to the LAF is used only for intended purposes.

Hezbollah Sanctions

Hezbollah, as an entity, is listed as a Specially Designated Terrorist (1995); a Foreign Terrorist Organization (1997); and a Specially Designated Global Terrorist or SDGT (2001). Hezbollah was designated again in 2012 under E.O. 13582, for its support to the Syrian government. Several affiliated individuals and entities have also been designated, including Secretary-General Hasan Nasrallah (1995) and the Hezbollah-run satellite television network Al Manar.

In May, the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) announced a set of additional sanctions on Hezbollah members:

- On May 15, OFAC designated Muhammad Qasir as a SDGT. Qasir served as a conduit for financial disbursements from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force to Hezbollah.

- On May 16, OFAC together with six Arab Gulf states designated members of Hezbollah's Shura Council, the group's primary decisionmaking body.

- On May 17, OFAC designated two additional Hezbollah members as SDGTs: Hezbollah financier Muhammad Ibrahim Bazzi, and Hezbollah's representative to Iran, Abdullah Safi al Din.

Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act of 2015

In December 2015, the 114th Congress enacted a sanctions bill targeting parties that facilitate financial transactions for Hezbollah's benefit (H.R. 2297, P.L. 114-102). The Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act of 2015 (HIFPA) requires, inter alia, that the President, subject to a waiver authority, prohibit or impose strict conditions on the opening or maintaining in the United States of a correspondent account or a payable-through account by a foreign financial institution that knowingly

- facilitates a transaction or transactions for Hezbollah;

- facilitates a significant transaction or transactions of a person on specified lists of specially designated nationals and blocked persons, property, and property interests for acting on behalf of or at the direction of, or being owned or controlled by, Hezbollah;

- engages in money laundering to carry out such an activity; or

- facilitates a significant transaction or provides significant financial services to carry out such an activity.

Some Lebanese observers have expressed concern that the legislation could inadvertently damage Lebanon's economy or banking sector if regulations written or actions taken to implement the law broadly target Lebanese financial institutions or lead other jurisdictions to forgo business in Lebanon because of difficulties associated with distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate institutions and activities.125 Items of particular interest to Lebanese parties, as U.S. Treasury officials craft implementing regulations for the law, include whether or not the United States will consider Lebanese government payments of salaries to Hezbollah members who hold public office to be activities of terrorist financing or money laundering concern.

Hezbollah's leader, Hassan Nasrallah, has sought to downplay the effects of this law, stating the following in a June 2016 speech:

Hizballah's budget, salaries, expenses, arms and missiles are coming from the Islamic Republic of Iran. Is this clear? This is no one's business. As long as Iran has money, we have money. Can we be any more frank about that? Our allocated money is coming to us, not through the banks. Just as we receive rockets with which we threaten Israel, our money is coming to us. No law can prevent this money from reaching us.126

At the same time, Nasrallah also criticized Lebanese banks for what he described as overcompliance with the legislation, saying, "[...] there are banks in Lebanon that went too far. They were American more than the Americans. They did some things that the Americans did not even ask them to do."127

Some analysts have questioned the effect of U.S. sanctions on Hezbollah, noting that the group maintains a largely cash-based economy and that Iran is still able to use land and air corridors to conduct cash transfers.128

Lebanese leaders have raised concerns about potential unintended consequences of any new sanctions on groups with ties to Hezbollah, given that Hezbollah is deeply embedded in Lebanon's political and social spheres through its membership in Lebanon's governing coalition and management of a vast network of social services. Some have also noted that sanctions imposing new regulations on the Lebanese banking sector could lower the inflow of foreign remittances into Lebanon, estimated at 15% of the country's GDP.129 According to one analyst, "expatriate remittances support the solvency of Lebanon's banks, thus consolidating the banks' potential to finance the economy, in particular their ability to buy Lebanese treasury bonds."130

Since the enactment of HIFPA in late 2015, congressional leaders raised the possibility of imposing additional sanctions on Hezbollah and/or groups that maintain political or economic ties to Hezbollah. Some analysts have argued for the use of secondary sanctions under HIFPA to target Hezbollah associates or allies, emphasizing the involvement of Hezbollah in a range of transnational criminal activities.131 U.S. policymakers have stressed that any new sanctions would seek to target Hezbollah, not the broader Lebanese state.

Hizballah International Financing Prevention Amendments Act of 2017

In July 2017, the Hizballah International Financing Prevention Amendments Act of 2017 was introduced by Representatives Royce and Engel in the House (H.R. 3329) and by Senators Rubio and Shaheen in the Senate (S. 1595).132 In October 2017, H.R. 3329 was passed by the House as amended and S. 1595 was passed by the Senate as amended.

The bill expands upon HIFPA 2015 in a number of ways. It would require the President to impose sanctions on foreign persons that he determines to have knowingly provided "significant support" to a fixed list of Hezbollah-linked entities (including, but not limited to, Al Manar TV), as well as sanctions on foreign persons determined to be engaged in fundraising or recruitment activities for Hezbollah. It would require a report on foreign financial institutions that are owned or located in the territory of state sponsors of terrorism, or which facilitate financial transactions for such institutions. It would also require the President to impose sanctions on any agency of a foreign state that knowingly provides significant financial or material support to Hezbollah, as well as sanctions on Hezbollah for transnational criminal activities. The bill includes a national security waiver which would allow the Administration to waive the imposition of sanctions.