Introduction

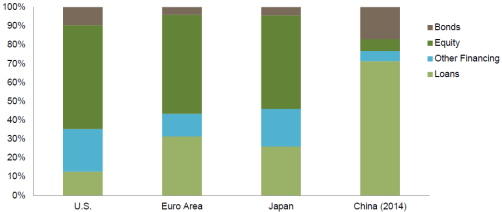

Companies turn to a variety of sources to access the funding they need to grow. Capital markets are the largest source of financing for U.S. nonfinancial companies, representing 65% of all financing for such companies in 2016 (Figure 1).1 Capital markets are segments of the financial system in which funding is raised through equity or debt securities.2 Equity, also called stocks or shares, refers to ownership of a firm. And debt, such as bonds, refers to the indebtedness or creditorship of a firm. In addition to capital markets, companies obtain funding from bank loans (13%) and other financing (23%).3

|

|

Sources: Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, National Bureau of Statistics of China. SIFMA, U.S. Capital Markets Deck, September 2017, at https://www.sifma.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/US-Capital-Markets-Deck-2017-09-11-SIFMA.pdf. Notes: "Bonds" and "equity" include both public and private offerings. "Loans" include all bank financing. "Other financing" includes insurance reserves, pension reserves, trade credit, and other accounts payable. |

U.S. capital markets are considered the deepest and most liquid in the world. U.S. companies are more reliant on capital markets for funding than companies in the euro area, Japan, or China, which rely more on bank loans (see Figure 1).4

Access to capital allows businesses to fund their growth, to innovate, to create jobs, and to ultimately help raise society's overall standard of living. Given the importance of U.S. capital markets and their role in allocating funding, issues affecting the markets generally warrant policy attention. Some of the most discussed recent trends include the decline in the number of public companies and the increased tendency of public capital to concentrate in larger companies. In addition, there are indications that private capital—which has less regulation and information disclosure—is growing in usage. Also of concern is the emergence of financial technology that both enables new methods of capital formation and poses significant regulatory challenges.

To address some of the trends mentioned above, Congress passed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act of 2012 (JOBS Act; P.L. 112-106; see text box below), which established a number of new options for expanding capital access especially for smaller companies. As discussed later in this report, some of the changes made by the JOBS Act have been successful in facilitating capital formation, but in other areas the same concerns remain. In response, the 115th Congress has considered many proposals to boost capital markets.

This report provides background and analysis on proposals related to capital formation through the two main ways of raising capital—public and private offerings—and the regulatory environment in which they operate.5 The report also explores key policy issues and their connection to legislative discussions. It provides general background for more than a dozen current legislative proposals, allowing for discussion of each proposal within its own policy context as well as providing a framework for viewing the proposals in aggregate. For easy navigation, legislative proposals are highlighted in text boxes within each relevant policy issue section.

|

Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act; P.L. 112-106) The JOBS Act was designed to reduce regulatory burdens on certain types of capital formation, especially for smaller companies. As a legislative response to the slow growth coming out of the 2007-2009 recession, the act was passed with bipartisan support in 2012. The JOBS Act established a number of new options to expand capital access through both public and private offerings. For example, it established the IPO On-Ramp as a scaled-down version of a standard initial public offering (IPO) for smaller companies. It also expanded access to existing private offerings traditionally serving smaller companies' funding needs—for example, the expansion of capital access through Regulation A+, the Threshold Rule, and Regulation D. The JOBS Act also established a new type of offering for crowdfunding. Some of these program changes have already generated significant issuer participation and impact. Much of the specifics of the JOBS Act are discussed in the relevant sections of this report. Though signed into law in 2012, it took several years to implement the JOBS Act. Effective implementation dates for JOBS Act provisions were as follows:

|

Raising Capital Through Securities Offerings

As the principal regulator of U.S. capital markets, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires that offers and sales of securities—whether debt or equity—either be registered with the SEC or be undertaken with an exemption from registration.6 Companies seeking funding through securities offering are referred to as issuers. Registered offerings, often called public offerings, are available to all types of investors and are not limited in the amount of funds that can be raised or resold. Registered offerings include a significant amount of disclosure about the company (the issuer), its financial status, and the funds that are being raised. A key attribute of public securities offerings is investors' ability to resell the securities on public secondary markets through national exchanges to all investor types.7 By contrast, securities offerings that are exempt from SEC registration are referred to as private offerings, private placements, or unregistered offerings. They are mainly available to those perceived to be more sophisticated financial institutions or individual investors thought to be better positioned to absorb the risk and make informed decisions with the reduced information disclosed in a private offering. Because of the restrictions on who may purchase them, private offerings generally do not trade on stock exchanges. In general, private offerings provide firms with more control over their internal affairs and lower compliance costs, whereas public offerings provide broader access to potential investors.

Public Offerings

Public offerings consist of initial public offerings (IPOs), the first time a company offers its shares of stock to the general public in exchange for cash, and subsequent public offerings. The IPO process, which is the source of much of the policy debate surrounding public offerings, is commonly regarded as the turning point for companies "going public." By going public, a company's shares can be owned by the public at large rather than just by the original owners, venture capital funds, and the relatively small pool of those perceived to be more sophisticated investors. SEC registration, which is a key requirement for going public, enables public disclosure of key company financial information.8 Companies may choose to go public to access capital that would allow founders to cash out their investments, to provide substantial stock and stock options9 to employees and through management incentive plans, and to fuel the company's future growth. Public companies may also benefit from a "liquidity premium," which translates into better share pricing compared with stock from comparable private offerings.10 Other potential benefits include publicity and brand awareness.11

There are also a number of drawbacks to going public. From an issuer's perspective, two of the most discussed drawbacks are compliance costs and certain changes to business operations.

- Compliance Costs. Some believe the costs of registration are disproportionately burdensome for small and medium-sized businesses, including startup firms. The direct costs include underwriting, external auditing, legal fees, and financial reporting fees.

- Business Operations. Public companies are often perceived to face incremental market pressure to perform well over the short term, to reduce insider control and decisionmaking flexibility, and to contend with increased shareholder activism (which sometimes can benefit a firm financially). Some research has indicated that going public can adversely affect corporate innovation; however, there are also many examples of innovative public companies.

Initial Public Offering

An IPO is the first time a company offers its shares of capital stock to the general public.12 An IPO gives the investing public the opportunity to own and participate in the growth of a formerly private company. The process begins with the company's selection of underwriters, lawyers, and accountants to prepare for the issuance of the securities, and, along with the company's top executives, they form an IPO working group. The process generally consists of three phases.

Prefiling Period. As part of an IPO, a company must file a registration statement and other documents that contain information about the company and the funds it is attempting to raise. During the prefiling period, the public filings are prepared and the planning begins with a thorough review of the company's operations, procedures, financials, and management, as well as its competitive positioning and business strategy.13 The disclosure documents serve the dual purpose of satisfying SEC registration requirements and communicating with investors.14

Waiting Period. Once the key disclosures are filed, the company waits for the SEC to review and provide approval of its draft registration statements. The company then concurrently addresses SEC comments and prepares roadshow presentations as well as legal documents. Roadshows are presentations made by an issuer's senior management to market the upcoming securities offering to prospective investors. Roadshows can commence only after the filing of registration statements because Section 5(c) of the Securities Act prohibits public offers of securities prior to the filing of a registration statement.15

Posteffective Period. The actual sales to investors take place after the SEC declares that the IPO registration is effective. The posteffective period extends from the effective date of the registration statements to the completion of distribution of the securities.16 With the completion of the IPO, a security generally continues to trade on a stock exchange.

IPO On-Ramp and Emerging Growth Company

Title I of the JOBS Act established streamlined compliance options for companies that meet the definition of a new type of issuer, called an emerging growth company (EGC).17 The streamlined process available to an EGC is also referred to as the "IPO On-Ramp," because it is a scaled-down version of a traditional IPO. This new process reduces regulatory requirements for companies to go public.

To qualify as an EGC, an issuer must have total annual gross revenues of less than $1 billion during its most recently completed fiscal year.18 EGCs maintain their status for five years after an IPO or when their gross revenue exceeds $1 billion, whichever occurs first, among other conditions. Relative to a standard IPO, EGCs' IPOs can take advantage of the following forms of relief:19

- Scaled disclosure requirements in which EGCs (1) need to provide two years of financial statements certified by independent auditors, instead of three years for a traditional IPO; and (2) are not required to provide compensation committee reports, among other things.

- EGCs are exempted from auditor attestations of internal control over financial reporting that are required by Sarbanes-Oxley Act Section 404(b).20

- "Test-the-waters" communications mean EGCs may meet with qualified institutional buyers and institutional accredited investors to gauge their interest in a potential offering during the registration process, an activity prohibited during a normal IPO.21

- A confidential SEC review process allows companies to submit draft registration statements to the SEC for a confidential review prior to making the filings public. While initially limited to EGCs, the SEC expanded this benefit to all companies as of July 10, 2017.

Whereas the first two compliance-related forms of relief would appear to generate cost savings for all EGC status holders, the test-the-waters and confidential review features may be especially valuable for companies in industries where valuation is uncertain and the timing of the IPO depends on regulatory or other approval (e.g., the biotech and pharmaceutical industries).22 The ability to submit confidentially and to "test-the-waters" with prospective investors can provide additional flexibility to company issuers. EGCs that take advantage of these can either continue the IPO process or withdraw after receiving feedback from the SEC and prospective investors, prior to making public disclosures.

Following the SEC's expansion of the confidential review option to all companies, most companies now use the process to incorporate feedback prior to public disclosure and announcement. IPO processes that used to take up to seven months from announcement to trading now take less than 50 days, with the reduced time due mostly to shifting of the review time to prior to announcements.23

Private Offerings

Both public and private companies could conduct private offerings to offer or sell securities in accordance with registration exemptions under the Securities Act. To raise capital through a private offering, a company must use one of the key registration exemptions under federal securities laws, including the following:

- Regulation D24 is the most frequently used exemption to sell securities in unregistered offerings. Companies relying on a Regulation D exemption do not need to register their offerings with the SEC, but they face limitations regarding investor type and resale restrictions of their offerings.25 Regulation D includes two SEC rules—Rules 504 and 506, which provide different maximum offering amounts, among other conditions.26

- Regulation A27 facilitates capital access for small to medium-sized companies. It has fewer disclosure requirements than the conventional securities registration process. Due to the JOBS Act, Regulation A was updated in 2015 with a two-tiered structure (Regulation A+) to exempt from registration offerings of up to $50 million annually, if specified requirements are met.28

- Regulation Crowdfunding29 permits companies to offer and sell securities through crowdfunding, which generally refers to the use of the internet by small businesses to raise capital through limited investments from a large number of investors.30

- Rule 144A31 is for resale transactions only. Issuers generally use it in a two-step process to first facilitate an offering on an exempt basis to financial intermediaries, and then resell to qualified institutional buyers, or QIBs (corporations deemed to be accredited investors).32

- Rule 147A33 permits companies to raise money from investors within their home state by registering at the state level, without concurrently having to register the offers and sales at the federal level.34

Regulatory Framework for Capital Markets

Regulatory Entities and Approaches

U.S. capital markets are mainly regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), state securities regulators, self-regulatory organizations (SROs), and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which generally regulates derivatives markets.35

As the principal regulator of capital markets, the SEC is responsible for overseeing significant parts of the nation's securities markets and certain primary participants such as broker-dealers, investment companies, investment advisors, clearing agencies, transfer agents, credit rating agencies, and securities exchanges, as well as SROs such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), and Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB).36

The SEC uses a combination of rules, enforcement, and examinations to construct a three-pronged regulatory approach that focuses on (1) disclosure-based rules, (2) an antifraud regime, and (3) rules governing securities market participants (for example, exchanges, broker-dealers, and investment advisors).37

Securities Disclosure Through Registration

One of the cornerstones of securities regulation—the Securities Act of 1933—is often referred to as the "truth in securities" law.38 As the phrase suggests, disclosures pertaining to securities allow investors to make informed judgments about whether to purchase specific securities by ensuring that investors receive financial and other significant information on the securities being offered for public sale. The SEC does not make recommendations as to whether to invest.39 The disclosure-based regulatory philosophy is consistent with Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis's famous dictum that "sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman."40

As mentioned previously, the types of disclosure vary based on whether a company is making a public or private offering. For public companies, the registration process requires companies to file with the SEC essential facts, including financial statements certified by independent accountants, information about the management of the company, a description of the security to be offered for sale, and a description of the company's properties and business.41 Registration statements generally become public shortly after the company files them with the SEC. As such, registering an offering with the SEC would make a company a public company.42 Private offerings also involve a registration process, but the process is scaled back, and these offerings are generally limited to more sophisticated investors who are perceived as better positioned to comprehend or tolerate the risks associated with less disclosure.

For more on disclosure, see the "Disclosure Requirements" section of this report.

Securities and Banking Regulation Compared

Capital market regulation differs from banking regulation in its regulatory philosophy and structural setup. Stocks, bonds, and other securities are not guaranteed by the government and can lose value for investors. As such, the SEC's primary concerns are promoting the disclosure of important market-related information, maintaining fair dealing, and protecting against fraud.43 This is designed to help investors make informed investment decisions. Although the SEC requires that the information provided be accurate, it does not guarantee it. Investors who purchase securities and suffer losses have recovery rights if they can prove incomplete or inaccurate disclosure of important information.

Banking regulation's prudential regulatory approach, on the other hand, emphasizes risk control and mitigation for the safety and soundness of individual institutions as well as the financial system as a whole.44 One rationale behind banking regulation is that, because bank deposits are guaranteed by the federal government, banks may have an incentive to take additional risks that they would not take in the absence of insurance on deposits. The government examines the operations of banks to safeguard taxpayer money and ensure that banks are not taking excessive risks.

These two different approaches have led to different agency designs and budget allocations. For example, banking regulators are heavily focused on examination programs that closely monitor and oversee financial institutions' operations and risk mitigation methods. One of the major banking regulators, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, allocates half of its annual budget toward mostly examination-based supervision and consumer protection programs.45 SEC regulation, in contrast, relies less on examinations.46 The SEC cedes certain examinations to SROs like FINRA and focuses its own examinations on selected priority areas, instead of a broader examination coverage of all securities issuers.47

Policy Issues

Some in Congress have called for modifying capital market regulations to make it easier for companies to raise capital. They argue that the existing regulatory structure unnecessarily restricts access to capital markets, making it more difficult for companies to grow and create jobs. Others have argued that certain approaches to expanding capital market access could put investors at risk of making uninformed decisions or becoming victims of fraud and other abuses.

This section analyzes key policy issues in public and private capital markets and assesses proposals to facilitate access to capital in each segment. In addition, emerging financial technology ("fintech") issues related to crowdfunding and initial coin offerings are also analyzed.

Crosscutting Themes

For many of the proposals discussed below, two themes apply—the relationship between capital formation and investor protection, and a scaled regulatory approach. The section starts with an explanation of each.

Capital Formation and Investor Protection

The policy debate surrounding efforts to promote capital access illustrates the perceived tradeoffs between investor protection and capital formation, two of the SEC's statutory mandates. Expanding capital access promotes capital formation and arguably "democratizes" capital markets by allowing for greater access to investment opportunities for more investors. Investor protection is considered to be important for healthy and efficient capital markets because some research suggests that investors would be more willing to provide capital, and even at a lower cost, if they have faith in the integrity and transparency of the underlying markets.

Maintaining a balance between these two goals can pose challenges for policymakers. For example, capital formation needs may be better met if issuers could choose their preferred methods of fundraising without regard to SEC registration. This is because the registration process raises the costs of accessing securities markets, which could potentially deter investment activities and reduce funding to businesses. At the same time, the reduced disclosure may expose retail investors of limited financial means to additional risks if they are not aware of key risk factors prior to making investment decisions (see "Investor Access to Private Offerings" for a discussion of "accredited investors").

A Scaled Regulatory Approach

The relationship between public and private offerings used to be more clearly defined; registration requirements were generally more substantial for public offerings than for private offerings prior to the 2012 JOBS Act. The public and private offering dichotomy started to blur following the JOBS Act, offering a more scaled regulatory approach. The act created a number of "hybrid" offerings that incorporate design features of both public and private offerings. The most obvious example is Regulation A+, a private offering that could potentially trade on public exchanges to a greater extent. As such, capital access regulation is less "one size fits all" than before, though the debate about whether regulation has been appropriately tailored is ongoing.

Table 1 highlights a number of key attributes that determine each securities offering's capital access capacity. These attributes should not be viewed in isolation, as they work together to form a holistic design for meeting each offering's policy goal. Below are examples of key attributes of major offering programs.

- Maximum Offering Amount. This is the upper limit of the offering program. For example, Regulation Crowdfunding currently has a size limit of around $1 million for any given year, limiting the program to smaller firms. In contrast, public offerings have no maximum amount, but issuers must undergo full disclosure.

- Filing Requirements. As mentioned previously, disclosure is at the core of securities regulation and is also the dividing point between public and private offerings.48 Generally, a higher level of disclosure (which may be associated with higher costs) leads to larger offering size limits and broader investor access, as well as reduced resale restrictions.

- Nonaccredited Investor Access. This attribute limits the kinds of investors allowed to participate in an offering. Generally, the higher the amount of disclosure, the more open an offering is to nonaccredited investors, who are perceived as less sophisticated.49

- Resale Restrictions. Resale pertains to owners of securities transferring ownership to others for cash. Resale restrictions determine whether the instruments could enter secondary markets.50 Resale capability is a given for publicly traded shares, but for private offerings, resale is generally restricted. For example, the private offering with the largest volume—Regulation D—faces resale restrictions, meaning investors have fewer exit options.

- Preemption of State Registration or Qualification. States impose certain securities regulations concurrent with SEC regulations.51 Certain offering programs—for example, Regulation A-Tier 1—face requirements to register securities with the states, which have regulatory responsibility and expertise over small and local securities. This could be challenging and costly for issuers if the offering operates in multiple states, each with different registration requirements. In contrast, Regulation A-Tier 2, Regulation D-Rule 506, and Regulation Crowdfunding preempt state laws.

The various attributes are structured so as to create a relatively tailored system in which smaller companies have available to them less burdensome approaches to raising capital. In a 2017 public speech, SEC Chairman Jay Clayton emphasized the importance of a scaled regulatory approach in securities regulation.

Recently, Congress and the SEC have taken significant steps to further develop a capital formation ecosystem that includes a scaled disclosure regime. Now, for example, a small company may begin with a Regulation A mini-public offering of up to $50 million, then move to a fully registered public offering as a smaller reporting company (EGC), and eventually develop into a larger, more seasoned issuer (Full-disclosure IPO). This is a potentially significant development and I believe there remains room for improving our approach to the regulation of capital formation over the life cycle of a company—to be clear, improvements that also serve the best interests of long-term retail investors.52

Reflecting the same consideration for companies of different sizes and needs, the 115th Congress is considering a number of legislative proposals to further expand this scaled approach, building on existing JOBS Act measures. Many of the proposals either modify the attributes listed in Table 1 so as to expand a particular type of offering or to create new types of offerings. Examples of these proposals are presented in text boxes throughout the remainder of this report.

Source: CRS, based on SEC reporting.

Note: The descriptions in the table apply to general conditions only; they are not inclusive of all conditions and exceptions.

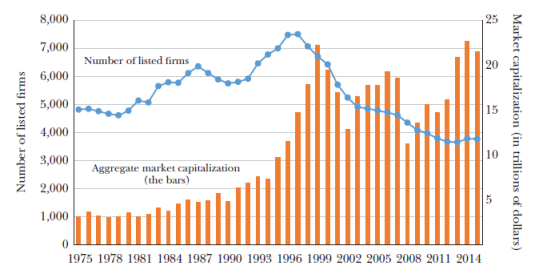

Facilitating Public Offerings

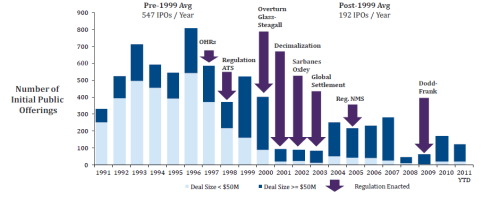

Once a company goes through SEC registration and public disclosure, it is generally referred to as a public company. A public offering was traditionally viewed as a significant funding source for growing companies, but its importance has generally deteriorated in the last two decades. The number of U.S.-listed domestic public companies has declined by half from the previous peak in the mid-1990s, as seen in Figure 2, whereas listings rose by half in other developed countries over the same time period.53 According to data provider Dealogic, U.S. IPOs raised $49.3 billion through 189 offerings in 2017, more than double 2016's level of $24.2 billion raised through 111 offerings.54 Nevertheless, 2017's number of IPOs remains far below the pre-1999 average of 547 IPOs per year (Figure 3), though there is some debate as to whether the period around the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s is the best comparison.

|

Figure 2. Number of U.S.-Listed Public Companies and Aggregate Market Capitalization |

|

|

Source: Center for Research in Security Prices and Kathleen M. Kahle and René M. Stulz, "Is the U.S. Public Corporation in Trouble?" Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, no. 3 (2017), pp. 67-88, at http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.31.3.67. Notes: Number of listed firms by year on the NYSE, Nasdaq, and Amex, and market capitalization from 1975 to 2015; market capitalization in 2015 dollars. |

The companies that fundraise through public offerings are increasingly large companies. The average size of public companies has grown four-fold between 1996 and 2017. As of early 2017, more than half of all U.S. market capitalization55 was held by around 140 companies with $50 billion or more in market value. Around 29% of total market capitalization was held by the largest 1% of public companies. The average market capitalization of a U.S.-listed company was $7.3 billion as of early 2017, compared to $1.8 billion (inflation adjusted) in 1996.56 In addition, aggregate market capitalization in 2014 and 2015 remained close to the all-time high (Figure 2). These trends indicate that although the absolute number of publicly listed companies has decreased, their average size has increased (through mergers, acquisitions, organic growth, or delisting of smaller public companies), aggregating to a total market capitalization that has showed no signs of decline in recent years.

Research indicates that smaller-company IPOs were down substantially prior to the JOBS Act (Figure 3), and that smaller firms are particularly likely to experience losses and earn lower returns.57 Following enactment of the JOBS Act, smaller companies' relative difficulty accessing capital through public offerings improved somewhat through the EGC program (as discussed in the "Expansion of "IPO On-Ramp"—Emerging Growth Company Status" section of this report). However, some argue that the total number of IPOs has not increased significantly following enactment of the JOBS Act and is still below its long-term average, suggesting that improvements are not meaningfully reflected in the number of IPOs.

|

Figure 3. Pre-JOBS Act IPO Trends Smaller IPOs Decreased Significantly |

|

|

Sources: JMP Securities, Dealogic, Capital Markets Advisory Partners, and Grant Thornton. |

Although there is a general consensus that regulatory relief could reduce entry barriers and the costs of going public, disagreement persists regarding the nature of the decline in the number of IPOs and whether the issue warrants regulatory intervention.58 Some argue that companies' decisions to shift from public offerings to private offerings are a structural change within the economy that does not require a regulatory fix. Others argue that the IPO decline is a consequence of the high costs of disclosure—an issue that could be remedied by policy. The main arguments concerning the IPO decline are summarized below.

Regulatory Explanations

- Regulatory Compliance. Some argue that increased regulation can have unintended consequences for companies trying to access capital. Specifically, critics of securities regulation point to laws and regulations enacted during the past two decades that have significantly affected the amount of public company compliance requirements. These laws and regulations include National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) order-handling rules (1996);59 the 1999 passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (P.L. 106-102); the Regulation Fair Disclosure (2000);60 the launch of decimalization (2001);61 the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002; P.L. 112-106); the 2003 Global Settlement ruling restricting conflicts of interest between equity research and investment banking;62 the Regulation National Market System (2005);63 and the Dodd-Frank Act (2010; P.L. 111-203), among others. (Figure 3).

- Costs of Going Public. According to the IPO Task Force,64 public companies in 2011 faced a one-time initial regulatory compliance cost of around $2.5 million and annual ongoing compliance costs of $1.5 million.65 These costs may outweigh the benefits and discourage some companies from going public.

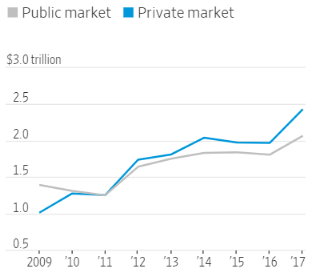

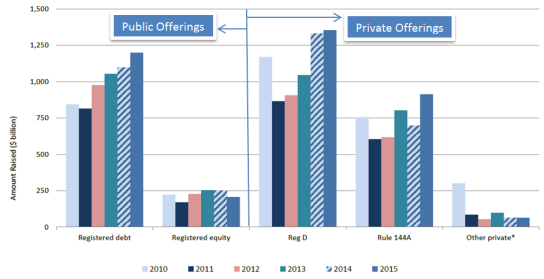

- "Deregulation" of Private Offerings. Some argue that the increased disclosure obligations for public companies coupled with the "unleashing" of investors in the "disclosure-lite" private markets have contributed to the increased use of private offerings as an alternative to public offerings, resulting in a decline in the number of public companies.66 According to the Wall Street Journal and data provider Dealogic, U.S. companies raised $2.43 trillion privately in 2017, around $0.36 trillion or 17% higher than the $2.06 trillion raised from public markets.67 The 2017 volumes represent the widest differential between the two methods since private capital reportedly surpassed public capital in 2011 (Figure 4).68

|

Figure 4. Public and Private Capital Raised by U.S. Companies (2009-2017) |

|

|

Source: Dealogic and Wall Street Journal Analysis of SEC Filings, "The Fuel Powering Corporate America: $2.4 Trillion in Private Fundraising," at https://www.wsj.com/articles/stock-and-bond-markets-dethroned-private-fundraising-is-now-dominant-1522683249. |

Structural Explanations

- Economies of "Scope." Economies of scope may exist when it is more efficient for smaller companies to be acquired than to operate as standalone entities.69 Some argue that long-term structural changes in product markets have led to declining profitability for smaller companies, whether public or private. In addition, even after going public, smaller companies are said generally to have low liquidity and limited analyst coverage,70 leaving them unable to reap the full benefits of public listing.71 These interpretations coincide with increased merger and acquisition activities, which some observers identify as being largely responsible for the delisting of public companies over the last decade.72

- Market Infrastructure. Some observers argue the market infrastructure needed to support smaller IPOs—such as specialized investment banks and analyst coverage of smaller public companies—is lacking, especially when compared to the market infrastructure for larger IPOs.73

- Agency Conflict. Agency conflict refers to the conflict between owners and managers over the control and use of corporate resources—conflicts that can potentially undermine corporate financial health and efficiency. In corporate finance, the owners of firms are generally referred to as stockholders. Some argue that some organizations may choose to rely more heavily on public and private debt, rather than public equity, thus potentially avoiding certain agency conflict issues because of the absence of public stockholders. As such, capital funding through private offerings could reduce agency conflicts for those companies and generate operational efficiency and productivity.74

- Financial Globalization. Financial globalization refers to the ease by which capital can flow around the world to find its most valued use. Financial globalization has increased significantly as countries have removed barriers to capital flows and new tools have facilitated cross-border investments. Several recent studies show that although the rest of the world has witnessed more IPOs due to greater financial globalization, U.S. IPO activity has not similarly benefited.75 A related study does not directly attribute U.S. IPO decline to financial globalization; however, it explains U.S. decline in relative terms when compared to the rest of the world. It is also evident that the global capital flow could affect the demand and supply dynamics of the U.S. domestic capital markets, thus impacting IPO-related capital needs.

In response to issues relating to public offerings, the 115th Congress is considering further expansion of EGC benefits as well as other regulatory-relief proposals, including amendments to disclosure requirements and the expansion of certain preemptions to state "blue sky" laws. The following sections analyze several of these proposals.

Expansion of "IPO On-Ramp"—Emerging Growth Company Status

As noted previously, to address the decline in the number of IPOs over the last two decades and to reduce barriers preventing smaller companies from accessing public offerings, the bipartisan JOBS Act of 2012 created a scaled-down alternative to standard IPOs for smaller companies that meet the criteria to be deemed emerging growth company (EGC) issuers. This streamlined process is referred to as an IPO On-Ramp.

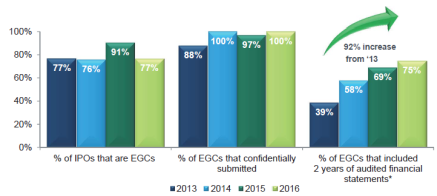

The IPO On-Ramp is a widely used JOBS Act provision. Around 87% of firms filing for an IPO after April 2012 were EGCs, meaning that only 13% of all IPOs since April 2012 were still subject to the conventional IPO process.76 Key EGC features—for example, the option to obtain confidential SEC review prior to public disclosure and elect for reduced disclosure of audited financials—are features adopted by the majority of IPO firms through the EGC status (Figure 5).

|

|

Source: Proskauer, 2017 IPO Study, at http://www.proskauer.com/files/uploads/Proskauer-2017-IPO-Study.pdf. Notes: Excludes two EGCs in 2015 and three in 2016 that provided financial statements since inception (i.e., the period of time since inception of the company, which may be less than two years). The study includes IPOs listed on a U.S. exchange with minimum initial base deal of $50 million in first public filing. |

Following the rapid adoption of EGC status, new proposals in the 115th Congress would further expand the length of time an EGC could maintain its status, and would also expand certain EGC benefits to all IPOs.

Proponents of regulatory relief stated that the EGC regime has enabled deeper capital formation without sacrificing investor protection, arguing that many private companies are still reluctant to go public, and suggesting further action.77 Some proponents believe the EGC program serves as a model for additional capital-formation-related regulation.78 As mentioned in the "Raising Capital Through Securities Offerings" section of the report, the test-the-waters and confidential-review features of the EGC framework can be particularly valuable for companies in industries where stock valuation is uncertain and the timing of the IPO depends on regulatory or other approval. For example, biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries reportedly have especially benefited from the EGC status. An executive from one biotechnology company that went public as an EGC testified in support of further expanding the EGC program, noting that 212 emerging biotech companies went public under EGC status as of March 2017, relative to 55 biotech IPOs in the five years leading up to the JOBS Act. The company argued this makes the EGC framework a significant capital access tool for biotechnology innovation.79

Critics point to the lighter regulatory standards under EGC, on top of other disclosure-related investor protection risks. They believe EGC is a regulatory label indicating lighter standards for listing. The EGC regime, they argue, appears to have enabled many relatively financially weak companies to conduct IPOs. The opponents believe that EGC companies tend to be lower in quality from a listing and investment perspective. In addition, these companies experienced underpricing relative to similarly sized companies prior to the JOBS Act.80 Underpricing refers to IPOs that are issued at below market value, leaving less money to fund company growth.

|

Examples of Bills That Would Expand IPO On-Ramp EGC Term Extension—Section 441 of H.R. 10, Title III of H.R. 3978, S. 2126, and H.R. 1645, Fostering Innovation Act. The bills would extend the exemption until the earlier of 10 years after the EGC went public, the end of the fiscal year in which the EGC's average gross revenues exceed $50 million, or when the EGC qualifies with the SEC as a large accelerated filer ($700 million public float, which is the number of shares that are able to trade freely among investors that are not controlled by corporate officers or promoters). Expand EGC Benefits to Non-EGCs—Section 499 of H.R. 10, S. 2347, and H.R. 3903, Encouraging Public Offerings Act. Under these bills, all issuers making an initial public offering would be allowed to communicate with potential investors before the offering and file confidential draft registration statements with the SEC. These benefits were previously available only to EGC status companies. (The SEC expanded the EGC confidential review benefit to all companies effective on July 10, 2017.)81 |

Disclosure Requirements

SEC registration and disclosure are at the core of securities regulation. They are also central components of securities valuation and price discovery. Firms need capital and investors need information to evaluate investment conditions. Issuers have incentives to disclose information if they are to compete successfully for funds against alternative investment opportunities. Consistent with this understanding, early research shows that voluntary disclosure reduces firms' cost of capital. Early evidence also shows that firms voluntarily disclose significant amounts of information beyond what is mandated by securities regulators.82 Despite the strong support of required and even voluntary disclosure identified in earlier research, current debates about disclosure are more focused on disclosure costs and information overload.

As discussed previously, issuers currently have to provide a significant amount of disclosure of company information throughout the SEC registration process. The SEC requires that offers and sales of securities either be registered with the SEC or be undertaken with an exemption from registration. Different levels of filings and disclosures are required for both public and private offerings. Column three of Table 1 presents these disclosure requirements. The disclosure-based approach is not without drawbacks. Some question the efficacy of disclosures and suggest they could be so exhaustive as to be counterproductive.83 Concerns also exist regarding whether both retail and institutional investors could comprehend the disclosed information.

Disclosure "Materiality"

Some companies struggle to determine precisely what information must be disclosed as part of the registration process. A general standard governing information to be disclosed under the securities laws is the concept of "materiality." Materiality pertains generally to the likely importance of a disclosure to a reasonable investor. SEC Rule 405 states, "When used to qualify a requirement for the furnishing of information as to any subject, [materiality] limits the information required to those matters to which there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would attach importance in determining whether to purchase the security registered."84 There is also significant case law concerning the concept of "materiality" in the courts, and it is generally defined in terms of whether a reasonable investor would have viewed the undisclosed information as having "significantly altered the total mix of information available."85

Ideally, from an economic perspective, the securities disclosures would neither be so restrictive that they omit essential information, nor so voluminous that they create information overflow or exhaust resources on irrelevant information.

The concept of materiality has always posed challenges for regulators and issuers, as it is often difficult to apply consistent standards for determining materiality at the level of individual companies. Certain discretion has been given to companies through a principle-based approach, which means the companies would have some flexibility to provide disclosures that they believe are material to reasonable investors.86 A principle-based approach may provide additional flexibility for companies to make decisions about materiality on a case-by-case basis, which is also how the courts generally assess materiality, but the lack of a "bright line" about what exactly must be disclosed can make it difficult for both investors and companies. One recent example is that different companies interpreted the threshold for disclosing material cyber breaches vastly differently.87 There is generally no bright-line approach on materiality. It is difficult, if not impossible, to provide a clean-cut approach as to materiality for all situations; thus, companies reportedly struggle to know when to disclose and when to hold back.88

Disclosure Costs and Readability

Public offerings generally face more rigorous and costly disclosure requirements relative to private offerings. Public company disclosure starts with an initial registration statement that includes a detailed description of the business, the security offered, and the management team, as well as audited financial statements, among other things. The reporting continues with the ongoing disclosure of quarterly and annual financials as well as the disclosure of key operational changes and corporate-governance-related information and events for shareholder voting.89 Public company regulatory compliance costs were estimated in 2011 to average about $2.5 million, with annual ongoing compliance costs of $1.5 million.90

Although disclosure requirements and related costs have increased over time, readability of disclosed information has become a regulatory concern in recent years. One of the most-cited examples is the size of Walmart's IPO prospectus in 1970, which totaled less than 30 pages.91 This compares to the hundreds of pages commonly expected of today's IPO filings. Studies show that the median text length of certain key SEC filings doubled between 1996 and 2013, yet the readability and the mix of "hard" information, which refers to the informative numbers in the text, have decreased.92 According to former SEC Chair Mary Jo White, most of this evolution was due to increased SEC rules and guidance that have required increasingly specific and detailed disclosures. This development eventually triggered regulatory discussions regarding "information overload," a term for the high volume of disclosure that can make it difficult for investors to find the most relevant information.93

The issue is further complicated when considering the types of investors to which the disclosed information is tailored. The majority of outstanding publicly traded U.S. company stocks are held by institutional investors. Their information needs and preferences may differ from those of retail investors.94 For example, more sophisticated institutional investors may find detailed reporting useful, whereas retail investors may have a harder time navigating the "information overload" and find "plain English" an easier way to comprehend investment disclosures. Some of these divergent preferences could be too costly to reconcile, because the current disclosure regime does not require different versions of disclosure by investor type.95 As such, the investor type that should serve as the benchmark for disclosure and reporting requirements continues to be a topic of debate.

Current Congressional and SEC Actions

Several current legislative proposals and agency actions would ease disclosures. Recent agency actions include SEC's rulemaking initiatives on Regulation S-K, which concerns disclosure of information not found on financial statements. As required by Congress through Section 108 of the JOBS Act and Section 72003 of the Fixing America's Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, the SEC completed two studies on disclosure requirements, aiming to "modernize and simplify" disclosures.96 The SEC subsequently proposed amendments to Regulation S-K on October 11, 2017, incorporating recommendations from the studies.97

Regulation S-K is a key part of the integrated disclosure regime. Issuers of securities offerings, especially public offerings, must file various disclosure documents that include, but are not limited to, Regulation S-K, Regulation S-X (financial statement disclosure requirements), and Regulation S-T (electronic filing regulations).98 The first version of Regulation S-K included only two disclosure requirements—a description of business and a description of properties. Over time, new disclosure requirements were added to Regulation S-K, and now it is the repository for the nonfinancial statement disclosure requirements under the Securities Act and the Exchange Act.99

As one law firm points out, the SEC rulemaking proposal to amend Regulation S-K includes approximately 30 discrete changes. Although none of the changes are likely to have a significant impact individually, taken together they could affect the preparation and presentation of disclosure documents, potentially reducing costs associated with disclosures.100

In addition to the agency initiatives, Congress has proposed a number of bills to further amend disclosure requirements (see text box below). Most of these amendments relate to the exemption of issuers from specific registration and reporting requirements. There is also a proposal to expand eligibility for smaller companies to use a more simplified registration form.

Some may argue that these proposals could circumvent the previously discussed tradeoff between capital formation and investor protection by increasing readability and usefulness of disclosures without coming at the expense of the exclusion of material information. Others argue that any decrease in regulation or disclosure would affect the effectiveness of investment decisionmaking and increase the risks facing investors.

|

Examples of Bills That Would Amend Disclosure Requirements Section 411 of H.R. 10, Subtitle C–Small Company Disclosure Simplification. The bill would exempt from requirements to use Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) for SEC filings (1) emerging growth companies (i.e., companies with revenues below a specified threshold); and (2) on a temporary basis, certain other smaller companies. Section 426 of H.R. 10 and H.R. 4529, Accelerating Access to Capital Act. The bills would amend the SEC's Form S-3 registration statement for certain smaller reporting companies that have a class of common equity securities listed and registered on a national securities exchange to qualify for a simplified registration and reporting process. Section 509 of P.L. 115-174, Section 499A of H.R. 10, and H.R. 4279, Expanding Investment Opportunities Act. The law allows certain types of investment companies (closed-end funds) to qualify for a streamlined securities registration and reporting process. Section 507 of P.L. 115-174, Section 406 of H.R. 10, H.R. 1343, and S. 488. The law requires the SEC to increase, from $5 million to $10 million, the 12-month sales threshold beyond which an issuer is required to provide investors with additional disclosures related to compensatory benefit plans. Section 857 of H.R. 10. The bill would repeal the Dodd-Frank Act requirement that companies calculate and disclose the CEO-to-median-worker pay ratio. |

Preemption of State "Blue Sky" Laws

Another source of compliance costs for issuers is the fact that certain securities offerings have to navigate both federal- and state-level regulations. Although the SEC regulates and enforces federal securities laws, each state has its own securities regulator who enforces "blue sky" laws. These laws cover many of the same activities the SEC regulates, such as the sale of securities and those who sell them, but are confined to securities sold or persons who sell them within each state.101

The SEC and the states differ in their approach to securities regulation. SEC securities regulation requires disclosure of information about securities and their issuers, whereas the majority of states adopt "merit-based" securities regulation.102 Merit-based regulation generally refers to the authority to deny registration to an offering on the ground that it is substantively unfair or presents excessive risk to investors.103 In other words, merit regulation prohibits specific conduct upon review. The issuers would have to convince the states that the offerings are fair to investors.

State securities laws predate the first federal securities statute, the Securities Act of 1933, by a couple of decades. Although some federal statutes preempt state securities laws, state regulators retain the ability to police their own jurisdictions. In addition, there is said to be a separate line of tension between federal securities laws and state corporate law.104 For example, companies' bylaws of incorporation, which affect their corporate governance practices, are traditionally regulated through state corporate law. Some argue that certain federal provisions relating to executive compensation and shareholder voting, among other provisions, have challenged the decisionmaking authority of state regulation.105

Public offerings trading on one of the national exchanges—New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), American Stock Exchange (AMEX),106 and Nasdaq—received preemption of state registration through the enactment of the National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996 (NSMIA; P.L. 104-290). NSMIA was a milestone for "covered securities," which are preempted from blue sky laws' registration and qualification requirements. Under NSMIA, covered securities generally include securities (1) listed, or from a listed issuer, on certain national securities exchanges; (2) issued by a registered investment company; (3) sold only to SEC-defined qualified purchasers; or (4) that meet certain exemptions.107

Public offerings that do not meet the criteria for covered securities may have to comply with certain state-level regulations. Some argue that state laws adversely affect the deployment of securities offerings that are not part of the covered securities universe. States have regulatory responsibility and expertise over small and local securities. However, an issuer operating in multiple states without preemption of state regulation would have to meet different regulatory requirements in each state, increasing operational complexity and costs. On the other hand, proponents argue state regulations prevent fraud or manipulation of securities offerings locally, and are unlikely to be eliminated because of various political reasons.108

The National Securities Exchange Regulatory Parity Act (see text box below) is an example of a current legislative proposal that would affect blue sky laws. Under current law, a security, generally through public offering, must be listed, or authorized for listing, on one of the three specified national securities exchanges as discussed above, in order to be exempt from state registration requirements. The bill instead would require that a security be listed, or authorized for listing on any national securities exchanges that have been approved by the SEC.109 This amendment would allow public offerings to trade on other exchanges, in addition to the currently specified three, to be potentially exempt from state registration. Although the bill was generally considered a technical fix, opponents believe that it creates confusion and encourages a race to the bottom, as exchanges could potentially lower listing standards to compete for business.110

|

Examples of Bills to Preempt State Regulation Section 501 of P.L. 115-174, Section 496 of H.R. 10, Title IV of H.R. 3978, and H.R. 4546, National Securities Exchange Regulatory Parity Act. The law exempts from state regulation securities designated as qualified for trading in the national market system. |

Facilitating Private Offerings

Private offerings have outpaced public offerings in recent years to become the more frequently used option for raising capital, as measured by aggregate capital raised (Figure 6).111 According to an SEC staff white paper, private debt and equity offerings for 2012 through 2016 combined exceeded public offerings by about 26%.112

Going public is arguably less of a necessity for certain private companies to raise capital, at least up to a certain size. Institutional investors, including mutual funds, hedge funds, and sovereign-wealth funds, are contributing to the trend of capital markets' increased reliance on private offerings as one of the key factors. For example, although these investors are not traditionally known for investing in startups, they are now allocating capital toward private offerings of high-tech "unicorns."113 The term "unicorn" refers to startup companies that have achieved a valuation of at least $1 billion, while remaining privately funded.

However, concerns persist that smaller companies face difficulties accessing capital. Private offerings are especially important for smaller companies, since they are traditionally viewed as the funding tool for smaller, pre-IPO firms. Some argue that the JOBS Act has not revived public capital access for smaller companies with market capitalization of less than $75 million.114 The SEC's Advisory Committee on Small and Emerging Companies stated in May 2017 that "identifying potential investors is one of the most difficult challenges for small businesses trying to raise capital."115

|

Figure 6. Aggregate Capital Raised in Securities Markets by Offering Methods |

|

|

Sources: SEC Division of Economic and Risk Analysis, EDGAR Form D and Form D/A filings for Rule 504, 505, and 506 offerings; Thomson Financial for all others. Notes: Other private offerings include Regulation S and other Section 4a (2) offerings. The graph does not reflect some of the new private offering programs or new changes to existing programs that became effective after June 2015. Of special note are Regulation Crowdfunding and Regulation A+, which are covered in more detail in the "Policy Issues" section of the report. |

Smaller companies' relative difficulty accessing capital through public offerings has encouraged the use of private offerings as an alternative funding source. All else equal, the increased use of private offerings could reduce companies' need to go public. It is within this context that Congress has initiated a number of policy changes and legislative proposals focusing on a scaled regulatory approach that would ease firms' access to private offerings. These proposals fall into three categories: (1) the expansion of investor access to private offerings, (2) the increase in the upper limit and issuer eligibility for Regulation A+, and (3) the creation of a new exemption for micro offerings.

Investor Access to Private Offerings

As shown in Table 1, private offerings are often limited in the kinds of investors to which they can be offered. One approach to expanding capital access for private offerings is to expand investor availability. As explained below, policymakers could expand (1) the type of eligible investors by widening the accredited investor definition, (2) the number of eligible investors by increasing the number of nonaccredited investors allowed to participate in private offerings, or (3) the communication to eligible investors by allowing broader outreach. A number of legislative proposals in the 115th Congress (listed in the text box below) would increase investors' access to private offerings along these lines.

As mentioned in the "Capital Formation and Investor Protection" section of the report, investor protection concerns are generally viewed alongside capital formation needs in a policy context. Some have argued that increasing investor access would improve capital formation by creating a larger eligible investor pool for certain securities offerings and would "democratize" investment opportunities by permitting a wider array of investors to participate. However, there are concerns regarding investor protection. Unlike offerings registered with the SEC, certain unregistered offerings lack disclosure of material information, thus exposing investors to higher risk.

Accredited Investors

As mentioned earlier, generally only "accredited" investors are allowed to invest in private offerings. According to federal securities regulations, accredited investors are institutional investors or individual investors who (1) are financially sophisticated, (2) have the wherewithal to sustain financial losses, and (3) have the ability to fend for themselves if faced with adverse circumstances.116

The purpose of the accredited investor concept is to identify entities and persons who can bear the economic risk of investing in unregistered securities and to protect ordinary investors from excess risk and potential fraud. According to the SEC, an accredited investor, in the context of an individual, is defined using a number of income and net worth measures: (1) earned income that exceeded $200,000 (or $300,000 together with a spouse) in each of the prior two years, and can reasonably be expected to be the same for the current year; or (2) net worth over $1 million, either alone or together with a spouse (excluding the value of the person's primary residence). Around 10% of U.S. households qualified as accredited investors in 2013.117

An accredited investor, in the context of an institution, includes certain entities with over $5 million in assets, as well as regulated entities such as banks and registered investment companies that are not subject to the assets test.118

Qualifying as an accredited investor is significant because accredited investors may participate in investment opportunities that are generally not available to nonaccredited investors, such as investments in private companies and offerings by hedge funds, private equity funds, and venture capital funds.119

The income- and net-worth-based definition of an accredited investor has generated criticism, as it arguably suggests that higher net worth equates to investing sophistication. The definition also generates concerns about its sufficiency in capturing those who need investor protection. Some question, for example, whether a widow who relies on her existing net worth for financial security should be eligible for higher-risk investing.

The application of the accredited investor definition faces additional challenges. A definition relying on numeric thresholds provides a clear criterion or guideline for implementation that could produce predictable and consistent results in application. By reading the definition, investors would know if they are accredited investors or not. This approach, however, poses a challenge because certain measures of financial sophistication cannot be easily tracked through standardized numerical approaches or be determined based on income or wealth. This has led some to object to the current accredited investor definition, which is solely based on income and net worth measures.120

Threshold Rule

The SEC Threshold Rule (§12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934) restricts the maximum number of nonaccredited investors allowed to participate in private securities offerings. It establishes the thresholds at which an issuer is required to register a class of securities with the SEC.121 Prior to the JOBS Act, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 required a private company to register securities with the SEC if it had total assets exceeding $10 million and shares held by 500 or more shareholders, without regard to nonaccredited investor status.122 Effective in 2012, the JOBS Act raised the shareholder registration threshold to either 2,000 persons, or 500 persons who are nonaccredited investors.123 In addition, to address the "Facebook problem"—when companies were forced to go public because the number of shareholders triggered threshold requirements for registration—employee compensation plan holders were no longer considered holders of record.124

General Solicitation

Issuers often market their private offerings at promotional events. The events are often sponsored by angel investors (early-stage investors, mostly high-net-worth individuals), venture capital associations, nonprofits, or universities and are used to communicate that a company is interested in, if not actively seeking, investor financing. Certain types of general promotion or advertising were banned for Regulation D private offerings prior to the JOBS Act to prevent nonaccredited investors from inadvertently investing. The JOBS Act created a new private offering category under Regulation D, wherein issuers are allowed to engage in general solicitations to accredited investors while taking "reasonable steps" to verify their accredited status.125

Some market participants have advocated for a further removal of certain general solicitation restrictions, a move welcomed by trade groups that would benefit from reduced compliance costs and reduced uncertainty. Critics of these efforts, however, raise concerns about investor protection, especially given the potential participation of nonaccredited investors in promotional events intended for accredited investors.126

|

Examples of Bills That Would Expand Investor Access to Private Offerings Accredited Investor Definition Section 860 of H.R. 10, and H.R. 1585. The bills would amend the Securities Act of 1933 accredited investor definition by including certain nonaccredited investors who could demonstrate their relevant financial education and experience. The bills would include, among other investors, those with

H.R. 3972. The Family Office Technical Correction Act would specify that family offices and family clients are accredited investors under Regulation D. Family offices are entities established by wealthy families to manage their wealth and provide other services to family members, such as tax and estate planning services.127 Threshold Rule Section 497 of H.R. 10, and H.R. 5051. The provision would expand the number of nonaccredited investors allowed for private offerings under the SEC registration threshold. The provision raises the SEC threshold for companies to register as public reporting companies to 2,000 nonaccredited investors from 500 nonaccredited investors, among other amendments. General Solicitation Section 452 of H.R. 10, H.R. 79, and Section 913 of H.R. 3280. The provisions would direct the SEC to revise Regulation D, which exempts certain offerings from SEC registration requirements but prohibits general solicitation or general advertising with respect to such offerings. Under this provision, the prohibition would not apply to events with specified kinds of sponsors, including "angel investor groups" that are unconnected to broker-dealers or investment advisers, if specified requirements are met. |

"Mini-IPO"—Regulation A+

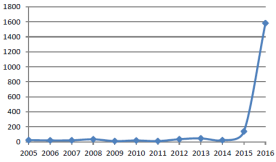

Another way that some propose to facilitate capital formation is the further expansion of Regulation A+. Regulation A+, or "Mini-IPO," is a private exemption to facilitate private offering capital access for small- to medium-sized companies. A mini-IPO is like a regular IPO in the sense that it has no resale restrictions and could potentially list on public stock exchanges. But unlike an IPO, it is subject to offering size limits and certain investment limits on nonaccredited investor access, as summarized in Table 1. Regulation A+, which expanded the existing Regulation A, became effective on June 19, 2015, a few years after the signing of the JOBS Act in 2012. Regulation A was a little-used regulatory regime prior to the JOBS Act; starting from the enactment of Regulation A+, the offerings have significantly expanded as measured by the number of total qualified offerings and the aggregate qualified offerings amounts sought (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7. Aggregate Capital Raised in Qualified Regulation A Offerings 2005-2016 (in millions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: SEC Division of Economic and Risk Analysis. SEC report to Congress, Access to Capital and Market Liquidity, August 2017, at https://www.sec.gov/files/access-to-capital-and-market-liquidity-study-dera-2017.pdf. Note: Not inflation-adjusted. |

Regulation A+ provides two tiers of offerings:128

- Tier 1, which allows securities offerings of up to $20 million in a 12-month period, with not more than $6 million in offers by selling to security-holders that are affiliates of the issuer. Tier 1 is subject to both state and federal registration and qualification requirements.

- Tier 2, which allows securities offerings of up to $50 million in a 12-month period, with not more than $15 million in offers by selling to security-holders that are affiliates of the issuer. Certain qualified purchasers of Tier 2 offerings are exempt from state securities law registration and qualification requirements.

Despite the regime's perceived high potential and upward trend, some contend it has fallen short of expectations for the following reasons:129

- Capital Raised Is Relatively Low. Regulation A+'s aggregate capital raised in qualified offerings, less than $2 billion as of 2016, seems low compared to the total private market debt and equity issuance of $1.68 trillion in 2016.130

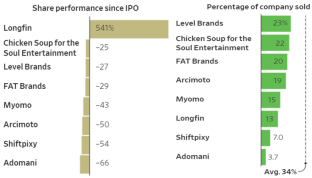

- Public Trading Is Rare. Although securities issued under Regulation A+ have traded on public exchanges in a few cases, the entering of Regulation A+ into public trading platforms is still uncommon.131 According to the Wall Street Journal, there were eight listed mini-IPOs in 2017. Seven of the eight were trading at an average of 42% below their offer prices (relative to average price rise of 22% for a traditional IPO in 2017). On average, around 15% of mini-IPO companies' total stock was available to trade in 2017, relative to 34% for all U.S.-listed IPOs, making the stocks harder to trade and more volatile (Figure 8).132

- Financial Industry Is the Heaviest User So Far. The program is not broadly adopted; around 37% of Regulation A+ filings and half of proceeds go to finance, insurance, and real estate companies.133

|

Figure 8. Stock Performance of Publicly Listed Regulation A+ Companies |

|

|

Sources: Corrie Driebusch and Juliet Chung, "IPO Shortcuts Put Burden on Investors to Identify Risk," Wall Street Journal and Dealogic, February 6, 2018, at https://www.wsj.com/articles/ipo-shortcuts-put-burden-on-investors-to-identify-risk-1517913000. |

There are legislative proposals in the 115th Congress to further expand Regulation A+'s upper limit (H.R. 4263) and to broaden its eligible issuer base (H.R. 2864).

Some have proposed expanding the upper limit of Regulation A+, arguing that in its current form it still faces hurdles in gaining market acceptance because such offerings cost more than a traditional private placement, but tend not to attract major underwriters, broker-dealers, and research coverage, because the deal sizes are small relative to a traditional IPO. Some believe that further lifting the upper limit would potentially alleviate size-related concerns for market intermediaries.134 Proponents of a proposal to broaden the Regulation A+ eligible issuer base also argue that thousands of SEC reporting companies are currently not able to access Regulation A+. By allowing more companies to use Regulation A+, it would enhance capital formation.135

Others consider the expansion of Regulation A+ to potentially reduce incentives for companies to go public, thus undermining public securities markets.136 This could be to the detriment of both investors and markets, as public offerings provide greater investor protection and liquidity for trading.137 Some observers argue against immediate expansion, raising concerns that the regime is still in its early stages, and that demand and participation have not yet stabilized. In 2015, the upper limit for Regulation A+ was increased 10 times, to $50 million from $5 million. The program's long-term effects have not been observed in full,138 leading some to question whether now is the optimal time to extend the program, especially given that the SEC already has the discretion to change the size limit under the current rule.139

|

Example of Bills That Would Expand Mini-IPOs Section 498 of H.R. 10, and H.R. 4263, Regulation A+ Improvement Act of 2017. The provision would increase the upper limit of offerings that are exempt from registration, subject to eligibility, disclosure, and other matters as specified in Regulation A+. Section 508 of P.L. 115-174, and H.R. 2864, Improving Access to Capital Act. The provision directs the SEC to expand Regulation A+ rules to include "fully reporting" companies.140 Regulation A+ currently applies to nonreporting companies only. |

Micro Offering

There is considerable demand for seed and startup capital for U.S. small businesses, some of which may be at the forefront of technological innovation and job creation. Yet some companies may be too small to realistically issue private offerings under existing exemptions. For example, an official from the U.S. Small Business Administration stated that 25% of startups report having no startup capital, while 20% cite lack of access to capital as a primary constraint to their business health and growth.141 Proposals related to what are referred to as micro offerings are intended to assist small businesses that are deemed to have insufficient capital access. Specifically, the Micro Offering Safe Harbor Act142 proposes a new private offering that would exempt certain micro funding from federal registration as well as state blue sky laws. The exempted micro offerings would also be required to meet each of the following requirements:143

- Each investor has a substantive preexisting relationship with an owner.

- There are 35 or fewer purchasers.

- The amount does not exceed $500,000.

Proponents believe it would more easily allow small businesses and startups to raise limited amounts of capital from their personal network of family and friends without running afoul of federal and state securities laws.144 Business trade groups have stated that the micro offering legislation would "appropriately scale" federal rules and regulatory compliance for small businesses.145

Opponents, however, raise investor protection concerns stemming from reduced disclosures and the absence of provisions to disqualify "bad actors" with criminal records, among other things. One point of contention is that micro offerings would not be subject to resale restrictions, meaning they could be immediately sold off to other qualified investors. The lack of a resale restriction for unregistered securities could expose investors to potential "pump and dump" schemes,146 a form of securities fraud that involves artificially boosting the price of a security in order to sell it for more.147

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that only a relatively small number of securities transactions would be covered under the expanded exemption that are not currently covered by other existing exemptions.148

|

Examples of Bills That Would Expand Micro Offerings Section 461 of H.R. 10, and H.R. 2201, Micro Offering Safe Harbor Act. The provisions would exempt certain micro offerings from (1) state regulation of securities offerings, and (2) federal prohibitions related to interstate solicitation. This exemption would allow for the participation of small offerings without triggering the Securities Act registration and state blue sky securities laws. |

Facilitating Fintech Offerings

The development of financial technology ("fintech")149 has disrupted industries and led to new capital access options not previously overseen by the SEC regulatory regime. Policymakers are now considering whether these new innovations fit well within the existing regulatory framework, or whether the framework should be adapted to address the risks and benefits that they pose. This development affects not only the SEC, but also other financial regulators within the United States and across various global jurisdictions.

Crowdfunding and initial coin offerings (ICOs) are two of the most popular fintech capital access tools that are regulated by the SEC, if they fall within the definition of being securities.150

Securities-Based Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding generally refers to a financing method in which money is raised through soliciting relatively small individual investments or contributions from a large number of people.151 Four kinds of crowdfunding exist: (1) donation crowdfunding, where contributors give money to a campaign and receive in return, at most, an acknowledgment; (2) reward crowdfunding, where contributors give to a campaign and receive in return a product or a service; (3) peer-to-peer lending crowdfunding, where investors offer a loan to a campaign and receive in return their capital plus interest; and (4) equity crowdfunding, where investors buy stakes in a company and receive in return company stocks.152 Generally, equity crowdfunding and certain peer-to-peer lending crowdfunding could be subject to SEC regulation if they conform to the definition of securities.

Title III of the JOBS Act created a new exemption from registration for internet-based securities offerings of up to $1 million (inflation-adjusted) over a 12-month period. Title III intends to help small and startup businesses conduct low-dollar capital fundraising from a broad and mostly retail investor base over the internet. The JOBS Act includes a number of investor protection provisions, including investment limitations, issuer disclosure requirements, and a requirement to use regulated intermediaries. The crowdfunding final rule became effective on May 16, 2016.153

New Capital Access Venue and the "Wisdom of the Crowd"

Crowdfunding allows investors and entrepreneurs to connect directly, potentially creating access to new investment opportunities and allowing investors to tap into the collective opinions of a large group, often referred to as "the wisdom of the crowd."154 These new opportunities could provide much-needed seed capital to entrepreneurs who would otherwise lack capital access. To illustrate this point, one SEC staff white paper indicates that the issuers of securities-based crowdfunding tend to be small, young, prerevenue, and not profitable.155 The effects of crowdfunding facilitating business growth are illustrated by a study that indicated around 70% of reward-based crowdfunding projects resulted in the creation of startups.156