The development of offshore oil, gas, and other mineral resources in the United States is shaped by a number of interrelated legal regimes, including international, federal, and state laws. International law provides a framework for establishing national ownership or control of offshore areas, and U.S. domestic law has, in substance, adopted these internationally recognized principles. U.S. domestic law further defines U.S. ocean resource jurisdiction and ownership of offshore minerals, dividing regulatory authority and ownership between the states and the federal government based on the resource's proximity to the shore. This report explains the nature of U.S. authority over offshore areas pursuant to international and domestic law. It also describes state and federal laws governing development of offshore oil and gas and litigation under these legal regimes. The report also discusses recent executive action and legislative proposals concerning offshore oil and natural gas exploration and production.

Ocean Resource Jurisdiction

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,1 coastal nations are entitled to exercise varying levels of authority over a series of adjacent offshore zones. Nations may claim a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea, over which they may exercise rights comparable to, in most significant respects, sovereignty. Nations may also claim an area, termed the contiguous zone, which extends 24 nautical miles from the coast (or baseline). Coastal nations may regulate their contiguous zones, as necessary, to protect their territorial seas and to enforce their customs, fiscal, immigration, and sanitary laws. Further, in the contiguous zone and an additional area, the exclusive economic zone (EEZ), coastal nations have sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve, and manage marine resources and assert jurisdiction over

i. the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations and structures;

ii. marine scientific research; and

iii. the protection and preservation of the marine environment.2

The EEZ extends 200 nautical miles from the baseline from which a nation's territorial sea is measured (usually near the coastline).3 This area overlaps substantially with another offshore area designation, the continental shelf. International law defines a nation's continental shelf as the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond either "the natural prolongation of [a coastal nation's] land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance."4 In general, however, under UNCLOS, a nation's continental shelf cannot extend beyond 350 nautical miles from its recognized coastline regardless of submarine geology.5 In this area, as in the EEZ, a coastal nation may claim "sovereign rights" for the purpose of exploring and exploiting the natural resources of its continental shelf.6

Federal Jurisdiction

While a signatory to UNCLOS, the United States has not ratified the treaty. Regardless, many of its provisions are now generally accepted principles of customary international law and, through a series of executive orders, the United States has claimed offshore zones that are virtually identical to those described in the treaty.7 In a series of related cases long before UNCLOS, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed federal control of these offshore areas.8 Federal statutes also refer to these areas and, in some instances, define them as well. Of particular relevance, the primary federal law governing offshore oil and gas development indicates that it applies to the "outer Continental Shelf," which it defines as "all submerged lands lying seaward and outside of the areas ... [under state control] and of which the subsoil and seabed appertain to the United States and are subject to its jurisdiction and control...."9 Thus, the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) would appear to comprise an area extending at least 200 nautical miles from the official U.S. coastline and possibly farther where the geological continental shelf extends beyond that point. The federal government's legal authority to provide for and to regulate offshore oil and gas development therefore applies to all areas under U.S. control except where U.S. waters have been placed under the primary jurisdiction of the states.

State Jurisdiction

In accordance with the federal Submerged Lands Act of 1953 (SLA),10 coastal states are generally entitled to an area extending three geographical miles11 from their officially recognized coast (or baseline).12 In order to accommodate the claims of certain states, the SLA provides for an extended three-marine-league13 seaward boundary in the Gulf of Mexico if a state can show such a boundary was provided for by the state's "constitution or laws prior to or at the time such State became a member of the Union, or if it has been heretofore approved by Congress."14 After enactment of the SLA, the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Gulf coast boundaries of Florida and Texas do extend to the three-marine-league limit; other Gulf coast states were unsuccessful in their challenges.15

Within their offshore boundaries, coastal states have "(1) title to and ownership of the lands beneath navigable waters within the boundaries of the respective states, and (2) the right and power to manage, administer, lease, develop and use the said lands and natural resources...."16 Accordingly, coastal states have the option of developing offshore oil and gas within their waters; if they choose to develop, they may regulate that development.

Coastal State Regulation

State laws governing oil and gas development in state waters vary significantly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In addition to state statutes and regulations aimed specifically at oil and gas development, a variety of other laws could impact offshore development, such as environmental and wildlife protection laws and coastal zone management regulation. In states that authorize offshore oil and gas leasing, the states decide which offshore areas under their jurisdiction will be opened for development.

Federal Resources

The primary federal law governing development of oil and gas in federal waters is the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA).17 As stated above, the OCSLA codifies federal control of the OCS, declaring that the submerged lands seaward of the state's offshore boundaries appertain to the U.S. federal government. More than simply declaring federal control, the OCSLA has as its primary purpose "expeditious and orderly development [of OCS resources], subject to environmental safeguards, in a manner which is consistent with the maintenance of competition and other national needs...."18 To effectuate this purpose, the OCSLA extends application of federal laws to certain structures and devices located on the OCS;19 provides that the law of adjacent states will apply to the OCS when it does not conflict with federal law;20 and, significantly, provides a comprehensive leasing process for certain OCS mineral resources and a system for collecting and distributing royalties from the sale of these federal mineral resources.21 The OCSLA thus provides comprehensive regulation of the development of OCS oil and gas resources.

Federal Offshore Energy Development Moratoria and Withdrawals

In general, the OCSLA requires the federal government to prepare, revise, and maintain an oil and gas leasing program. However, at various times some offshore areas have been withdrawn from disposition under the OCSLA. These withdrawals have usually fallen under three broad categories applicable to OCS oil and gas leasing: those imposed directly by Congress, those imposed by the President under authority granted by the OCSLA,22 and other statutory or administrative protections intended to protect marine or coastal resources.

Congressional/Legislative Moratoria

Appropriations-based congressional moratoria first appeared in the appropriations legislation for FY1982. The language of the appropriations legislation barred the expenditure of funds by the Department of the Interior (DOI) for leasing and related activities in certain areas in the OCS.23 Similar language appeared in every DOI appropriations bill through FY2008. However, starting with FY2009, Congress has not included this language in appropriations legislation. As a result, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the agency within the Department of the Interior that administers and regulates the OCS oil and gas leasing program, is free to use appropriated funds to fund all leasing, preleasing, and related activities in any OCS areas not withdrawn by other legislation or by executive order.24 Language used in the legislation that funds DOI in the future will determine whether, and in what form, budget-based restrictions on OCS leasing might return.

The Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA), enacted as part of the Omnibus Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006,25 is another example of a legislative moratorium. The act created a new congressional moratorium over "leasing, preleasing or any related activity"26 in portions of the OCS. The 2006 legislation explicitly permits oil and gas leasing in areas of the Gulf of Mexico,27 but also established a new moratorium on preleasing, leasing, and related activity in the eastern Gulf of Mexico through June 30, 2022.28 This moratorium is independent of any appropriations-based congressional moratorium, and thus would continue even if Congress reinstated the annual appropriations-based moratorium.

OCSLA Section 12(a)

In addition to the congressional moratoria, Section 12(a) of the OCSLA authorizes the President to issue moratoria on offshore drilling in many areas. The first withdrawal covering substantial offshore areas was issued by President George H. W. Bush on June 26, 1990.29 This memorandum, issued pursuant to the authority vested in the President under Section 12(a) of the OCSLA, placed under presidential moratoria those areas already under an appropriations-based moratorium pursuant to P.L. 105-83, the Interior Appropriations legislation in place at that time. That appropriations-based moratorium prohibited "leasing and related activities" in the areas off the coast of California, Oregon, and Washington, and the North Atlantic and certain portions of the eastern Gulf of Mexico. The legislation further prohibited leasing, preleasing, and related activities in the North Aleutian basin, other areas of the eastern Gulf of Mexico, and the Mid- and South Atlantic. The presidential moratorium was extended by President Bill Clinton by a memorandum dated June 12, 1998.30

On July 14, 2008, President George W. Bush issued an executive memorandum that rescinded the executive moratorium on offshore drilling created by President George H. W. Bush in 1990 and renewed by President Bill Clinton in 1998.31 President George W. Bush's memorandum revised the language of the previous memorandum to withdraw from disposition only areas designated as marine sanctuaries.

President Barack Obama exercised the authority granted by Section 12(a) of the OCSLA to issue moratoria on exploration and production activities in certain areas off the coast of Alaska. On March 31, 2010, President Obama issued an executive memorandum pursuant to his Section 12(a) authority to "withdraw from disposition by leasing through June 30, 2017, the Bristol Bay area of the North Aleutian Basin in Alaska."32 This withdrawal was superseded on December 16, 2014, with a broader withdrawal "for a time period without specific expiration the area of the Outer Continental Shelf currently designated by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management as the North Aleutian Basin Planning Area ... including Bristol Bay."33 A month later, President Obama once again exercised his authority under Section 12(a) of the OCSLA to withdraw certain areas in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas off the coast of Alaska.34 Finally, on December 16, 2016, President Obama issued two more withdrawals under Section 12(a) of the OCSLA. One of these withdrew from disposition the entirety of the designated Chukchi Sea and Beaufort Sea Planning areas;35 the other withdrew from disposition areas "associated with 26 major canyons and canyon complexes offshore the Atlantic Coast."36

In 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13795, which modified the July 2008, January 2015, and December 2016 withdrawals to eliminate all of the areas withdrawn by those orders except "those areas of the Outer Continental Shelf designated as of July 14, 2008 as Marine Sanctuaries under the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972."37 As a result, only the North Aleutian Basin Planning Area and Bristol Bay, along with the aforementioned Marine Sanctuaries, are currently withdrawn from disposition pursuant to Section 12 of the OCSLA.

Other Statutory or Administrative Protections

While the OCSLA is the primary statute governing federal offshore energy exploration and production, other statutes play a role in determining what activities may take place in various offshore areas. All offshore activity must comply with generally applicable federal laws, those that protect the environment and public health. In addition, some statutes and administrative actions protect specific offshore regions from certain activities. For example, the National Marine Sanctuaries Act38 authorizes the Secretary of Commerce to "designate any discrete area of the marine environment as a national marine sanctuary" based on the criteria set forth in the act.39 It is unlawful to "destroy, cause the loss of, or injure any sanctuary resource,"40 a prohibition which effectively prohibits oil and natural gas exploration and production in the area, although as noted above these areas have also been withdrawn pursuant to Section 12 of the OCSLA. Similarly, Presidents have designated a handful of "marine national monuments" pursuant to their authority under the Antiquities Act.41 Such designations may explicitly or implicitly prohibit oil and natural gas exploration and production.42

Leasing and Development

In 1978, the OCSLA was significantly amended to increase the role of coastal states in the leasing process.43 The amendments also revised the bidding process and leasing procedures; set stricter criteria to guide the environmental review process; and established new safety and environmental standards to govern drilling operations.44 The OCS leasing process consists of four distinct stages: (1) the five-year planning program;45 (2) preleasing activity and the lease sale;46 (3) exploration;47 and (4) development and production.48

The Five-Year Program

Section 18 of the OCSLA directs the Secretary of the Interior to prepare a five-year leasing program that governs any offshore leasing that takes place during the period of coverage.49 Each five-year program establishes a schedule of proposed lease sales, providing the timing, size, and general location of the leasing activities. This program is to be based on multiple considerations, including the Secretary's determination as to what will best meet national energy needs for the five-year period and the extent of potential economic, social, and environmental impacts associated with development.50

During the development of the program, the Secretary must solicit and consider comments from the governors of affected states, and at least 60 days prior to publication of the program in the Federal Register, the Secretary must submit the program to the governor of each affected state for further comments.51 After publication, the Attorney General is also authorized to submit comments regarding potential effects on competition.52 Subsequently, at least 60 days prior to its approval, the Secretary must submit the program to Congress and the President, along with any received comments and the reasons for rejecting any comment.53 Once the program is approved by the Secretary, areas covered by the program become available for leasing, consistent with the terms of the program.54 The OCSLA also requires the Secretary to "review the leasing program approved under this section at least once each year" and authorizes the Secretary to "revise and re-approve such program, at any time."55 However, any "significant" revisions must comply with the requirements applicable to the original five-year program.56

The development of the five-year program is considered a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment and as such requires preparation of an environmental impact statement (EIS) under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).57 Thus, the NEPA review process complements and informs the preparation of a five-year program under the OCSLA.58

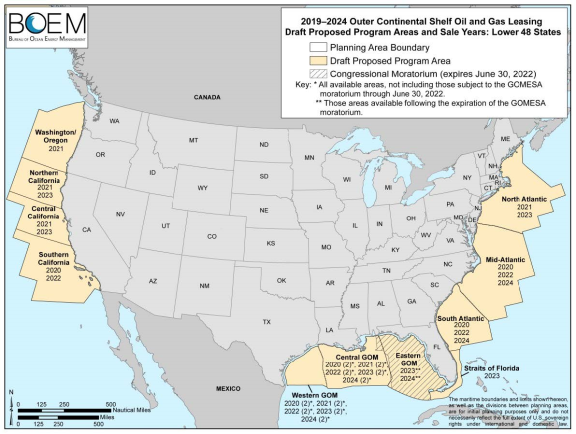

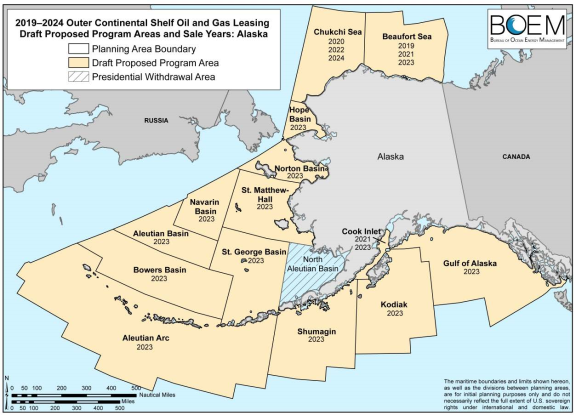

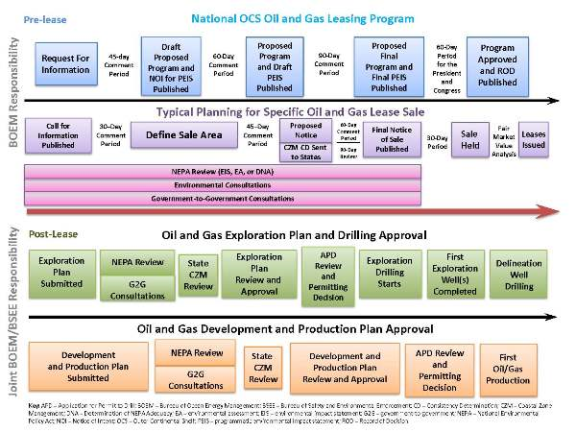

The current Five-Year Program received final approval from the Secretary of the Interior on January 17, 2017.59 The Program schedules 11 potential lease sales, "ten in portions of the three Planning Areas in the Gulf of Mexico not subject to moratorium and one in the Cook Inlet offshore Alaska."60 The Program notes that "[t]hese areas have high resource potential, existing infrastructure and Federal or state leases, and more manageable potential environmental and coastal conflicts with development" than other areas not included in the Program.61 The Trump Administration has proposed a superseding Five-Year Program, and published a Draft Proposed Program for 2019-2024 in January 2018.62 The planning areas and proposed dates of lease sales in each area are depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2 below, while Figure 3 depicts the process for consideration and adoption of a Five-Year Program and the accompanying Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement.

|

|

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, https://www.boem.gov/National-OCS-Program/. |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, https://www.boem.gov/National-OCS-Program/. |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, https://www.boem.gov/National-OCS-Program/. |

Lease Sales

The lease sale process involves multiple steps as well. Leasing decisions are impacted by a variety of federal laws; however, Section 8 of the OCSLA and its implementing regulations establish the mechanics of the leasing process.63

The process begins when the Director of BOEM publishes a call for information and nominations regarding potential lease areas. The Director is authorized to receive and consider these various expressions of interest in specific parcels and comments on which areas should receive special concern and analysis.64 The Director then considers all available information and performs environmental analysis under NEPA to craft a list of areas recommended for leasing and any proposed lease stipulations.65 BOEM submits the list to the Secretary of the Interior and, upon the Secretary's approval, publishes it in the Federal Register and submits it to the governors of potentially affected states.66

The OCSLA and its regulations authorize the governor of an affected state and the executive of any local government within an affected state to submit to the Secretary any recommendations concerning the size, time, or location67 of a proposed lease sale within 60 days after notice of the lease sale.68 The Secretary must accept the governor's recommendations (and has discretion to accept a local government executive's recommendations), if the Secretary determines that the recommendations reasonably balance the national interest and the well-being of the citizens of an affected state.69

The Director of BOEM publishes the approved list of lease sale offerings in the Federal Register (and other publications) at least 30 days prior to the date of the sale.70 This notice must describe the areas subject to the sale and any stipulations, terms, and conditions of the sale.71 The bidding is to occur under conditions described in the notice and must be consistent with certain baseline requirements established in the OCSLA.72

Although the statute establishes base requirements for the competitive bidding process and sets forth a variety of possible bid formats,73 some of these requirements are subject to modification at the discretion of the Secretary.74 Before the acceptance of bids, the Attorney General is also authorized to review proposed lease sales to analyze any potential effects on competition, and may subsequently recommend action to the Secretary of the Interior as may be necessary to prevent violation of antitrust laws.75 The Secretary is not bound by the Attorney General's recommendation, and likewise, the antitrust review process does not affect private rights of action under antitrust laws or otherwise restrict the powers of the Attorney General or any other federal agency under other law.76 Assuming compliance with these bidding requirements, the Secretary may grant a lease to the highest bidder, although deviation from this standard may occur under some circumstances.77

In addition, the OCSLA prescribes many minimum conditions that all lease instruments must contain. The statute supplies generally applicable minimum royalty or net profit share rates, as necessitated by the bidding format adopted, subject, under certain conditions, to secretarial modification.78 Several provisions authorize royalty reductions or suspensions. Royalty rates or net profit shares may be reduced below the general minimums or eliminated to promote increased production.79 For leases located in "the Western and Central Planning Areas of the Gulf of Mexico and the portion of the Eastern Planning Area of the Gulf of Mexico encompassing whole lease blocks lying west of 87 degrees, 30 minutes West longitude and in the Planning Areas offshore Alaska," a broader authority is also provided, allowing the Secretary, with the lessee's consent, to make "other modifications" to royalty or profit share requirements to encourage increased production.80 Royalties may also be suspended under certain conditions by BOEM pursuant to the Outer Continental Shelf Deep Water Royalty Relief Act, discussed infra.

The OCSLA generally requires successful bidders to furnish a variety of up-front payments and performance bonds upon being granted a lease.81 Additional provisions require that leases provide that certain amounts of production be sold to small or independent refiners. Further, leases must contain the conditions stated in the sale notice and provide for suspension or cancellation of the lease in certain circumstances.82 Finally, the law indicates that a lease entitles the lessee to explore for, develop, and produce oil and gas, conditioned on applicable due diligence requirements and the approval of a development and production plan, discussed below.83

Exploration

Lessees planning exploration for oil and gas pursuant to an OCSLA lease must prepare and comply with an approved exploration plan.84 Detailed information and analysis must accompany the submission of an exploration plan, and, upon receipt of a complete proposed plan, the relevant BOEM regional supervisor is required to submit the plan to the governor of an affected state and the state's Coastal Zone Management agency.85

Under the Coastal Zone Management Act, federal actions and federally permitted projects, including those in federal waters, must be submitted for state review.86 The purpose of this review is to ensure consistency with state coastal zone management programs as contemplated by the federal law. When a state determines that a lessee's plan is inconsistent with its coastal zone management program, the lessee must either reform its plan to accommodate those objections and resubmit it for BOEM and state approval or succeed in appealing the state's determination to the Secretary of Commerce.87 Simultaneously, the BOEM regional supervisor is to analyze the environmental impacts of the proposed exploration activities under NEPA; however, regulations prescribe that BOEM complete its action on the plan review within 30 days. Hence, extensive environmental review at this stage may be constrained or rely heavily upon previously prepared NEPA documents.88 If the regional supervisor disapproves the proposed exploration plan, the lessee is entitled to a list of necessary modifications and may resubmit the plan to address those issues.89 Even after an exploration plan has been approved, drilling associated with exploration remains subject to the relevant BOEM district supervisor's approval of an application for a permit to drill. This approval hinges on a more detailed review of the specific drilling plan filed by the lessee.

Development and Production

While exploration often will involve drilling wells, the scale of such activities is likely to increase significantly during the development and production phase. Accordingly, additional regulatory review and environmental analysis are typically required before this stage begins.90 Operators are required to submit a Development and Production Plan for areas where significant development has not occurred before91 or a less extensive Development Operations Coordination Document for those areas, such as certain portions of the Western Gulf of Mexico, where significant activities have already taken place.92 The information required to accompany submission of these documents is similar to that required at the exploration phase, but must address the larger scale of operations.93 As with the processes outlined above, the submission of these documents complements any environmental analysis required under NEPA. It may not always be necessary to prepare a new EIS at this stage, and environmental analysis may be tied to previously prepared NEPA documents.94 In addition, affected states are allowed, under the OCSLA, to submit comments on proposed Development and Production Plans and to review these plans for consistency with state coastal zone management programs.95 Also, if the drilling project involves "non-conventional production or completion technology, regardless of water depth," applicants might also submit a Deepwater Operations Plan (DWOP) and a Conceptual Plan.96 This allows BOEM to review the engineering, safety, and environmental impacts associated with these technologies.97

As with the exploration stage, actual drilling requires approval of an Application for Permit to Drill (APD).98 An APD focuses on the specifics of particular wells and associated machinery. Thus, an application must include a plat indicating the well's proposed location, information regarding the various design elements of the proposed well, and a drilling prognosis, among other things.99

Lease Suspension and Cancellation

The OCSLA authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to promulgate regulations on lease suspension and cancellation.100 The Secretary's discretion over the use of these authorities is specifically limited to a set number of circumstances established by the OCSLA. These circumstances are described below.

Suspension of otherwise authorized OCS activities may generally occur at the request of a lessee or at the direction of the relevant BOEM Regional Supervisor, given appropriate justification.101 Under the statute, a lease may be suspended (1) when it is in the national interest; (2) to facilitate proper development of a lease; (3) to allow for the construction or negotiation for use of transportation facilities; or (4) when there is "a threat of serious, irreparable, or immediate harm or damage to life (including fish and other aquatic life), to property, to any mineral deposits (in areas leased or not leased), or to the marine, coastal, or human environment...."102 The regulations also indicate that leases may be suspended for other reasons, including (1) when necessary to comply with judicial decrees; (2) to allow for the installation of safety or environmental protection equipment; (3) to carry out NEPA or other environmental review requirements; or (4) to allow for "inordinate delays encountered in obtaining required permits or consents...."103 Whenever suspension occurs, the OCSLA generally requires that the term of an affected lease or permit be extended by a length of time equal to the period of suspension.104 This extension requirement does not apply when the suspension results from a lessee's "gross negligence or willful violation of such lease or permit, or of regulations issued with respect to such lease or permit...."105

If a suspension period reaches five years,106 the Secretary may cancel a lease upon holding a hearing and finding that (1) continued activity pursuant to a lease or permit would "probably cause serious harm or damage to life (including fish and other aquatic life), to property, to any mineral (in areas leased or not leased), to the national security or defense, or to the marine, coastal, or human environment"; (2) "the threat of harm or damage will not disappear or decrease to an acceptable extent within a reasonable period of time"; and (3) "the advantages of cancellation outweigh the advantages of continuing such lease or permit in force...."107

Upon cancellation, the OCSLA entitles lessees to certain damages. The statute calculates damages at the lesser of (1) the fair value of the canceled rights on the date of cancellation108 or (2) the excess of the consideration paid for the lease, plus all of the lessee's exploration- or development-related expenditures, plus interest, over the lessee's revenues from the lease.109

The OCSLA also indicates that the "continuance in effect" of any lease is subject to a lessee's compliance with the regulations issued pursuant to the OCSLA, and failure to comply with the provisions of the OCSLA, an applicable lease, or the regulations may authorize the Secretary to cancel a lease as well.110 Under these circumstances, a nonproducing lease can be canceled if the Secretary sends notice by registered mail to the lease owner and the noncompliance with the lease or regulations continues for a period of 30 days after the mailing.111 Similar noncompliance by the owner of a producing lease can result in cancellation after an appropriate proceeding in any U.S. district court with jurisdiction as provided for under the OCSLA.112

Lease Assignments and Transfers

The OCSLA also provides the framework for federal oversight of transfers of offshore oil and gas exploration and production leases. Section 5(b) of the OCSLA states that "[t]he issuance and continuance in effect of any lease, or of any assignment or other transfer of any lease, under the provisions of this Act shall be conditioned upon compliance with regulations issued under this Act."113 The OCSLA further provides that "[n]o lease issued under this Act may be sold, exchanged, assigned, or otherwise transferred except with the approval of the Secretary [of the Interior, whose authority is exercised by BOEM]. Prior to any such approval, the Secretary shall consult with and give due consideration to the views of the Attorney General."114 These two requirements—of continued compliance with the OCSLA and the regulations issued pursuant to it, and of obtaining BOEM approval prior to transfer—are the only restrictions placed upon transfers by the OCSLA.115

The terms of the lease itself create obligations for offshore oil and natural gas exploration and production lessees. BOEM employs a form lease, so all lessees are bound by virtually identical lease terms and conditions. With respect to transfers, Section 20 of the form lease provides that "[t]he lessee shall file for approval with the appropriate regional BOEM OCS office any instrument of assignment or other transfer of any rights or ownership interest in this lease in accordance with applicable regulations."116 This filing requirement is the only new restriction or condition placed on transfers by the terms of the lease. However, the regulations issued by the agency pursuant to its OCSLA authority set forth more detailed requirements applicable to transfers of all or part of the lease.117

Royalty Collection and Revenue Distribution

As noted above, most leases obligate the lessee to pay royalties based on the "amount or value of the production saved, removed or sold" by the lessee.118 Most leases obligate the lessee to pay a royalty rate of at least 12.5%,119 although some leases are exempt from payment pursuant to a statutory or administratively determined exemption.120 The Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR) is the agency tasked with collection and disbursement of royalties from both onshore and offshore oil and gas production on federal lands.

Most of the revenue collected by the ONRR from royalty payments and any other payments associated with offshore oil and gas leases is "deposited in the Treasury of the United States and credited to miscellaneous receipts."121 However, a few statutory provisions direct some revenue to state and local governments in an effort to offset the disparate impacts of some offshore oil and gas exploration and production activity borne by coastal states and localities.

Section 8(g) of OCSLA addresses leasing details for "lands containing tracts wholly or partially within three nautical miles of the seaward boundary of any coastal State,"122 that is, the first three nautical miles of federal waters which border on state waters and, in most cases, are within several miles of the state's shoreline. Under the terms of Section 8(g), all revenue from leases wholly within that three-nautical-mile range must be deposited in a dedicated account in the Treasury.123 For leases partially within the three-nautical-mile range of state waters, a corresponding portion of the revenue from the lease must be deposited in the special account.124 The Secretary then must transfer to the coastal state 27% of the revenues collected from leases near their coastal waters.125 If the tract in question lies only partly within the first three nautical miles of federal waters, the disbursement to the coastal state is adjusted based on the percentage of the tract that lies within those three nautical miles.126 OCSLA also establishes a procedure for the resolution of boundary disputes.127

Certain revenue from certain leases in the Gulf of Mexico is also diverted from the general treasury by operation of law. Under GOMESA,128 50% of "qualified Outer Continental Shelf revenues" are to be deposited into a special account.129 The Secretary then must disburse 75% of the revenue deposited in that special account (or 37.5% of the total revenue) to the "Gulf Producing States" in accordance with a formula based in part on each state's distance from the lease tract, including further allocation to political subdivisions within the states.130 The states and political subdivisions are free to spend that money for any of the "authorized uses" set forth in GOMESA, including mitigation of various types of environmental harms that may result from offshore oil and gas exploration and production.131 The remaining 25% of the revenue deposited in the special account (or 12.5% of the total revenue) is directed to the states for expenditure in accordance with Section 6 of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965,132 which provides for apportionment of funds to the states for purposes of land acquisition, planning, and development for recreational purposes.133

Legal Challenges to Offshore Leasing

Multiple statutes govern aspects of offshore oil and gas development, and therefore, may give rise to legal challenges. The Marine Mammal Protection Act,134 Endangered Species Act,135 and other environmental laws provide mechanisms for challenging actions associated with offshore oil and gas production in the past.136 Of primary interest here, however, are legal challenges to agency action with respect to the planning, leasing, exploration, and development phases under the procedures mandated by the OCSLA itself and the related environmental review required by the National Environmental Policy Act.

The following paragraphs provide an overview of the existing case law, including legal challenges to the five-year plan and other aspects of the leasing process as well as controversies over revenue collection and distribution.

Suits Under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act

Jurisdiction to review agency actions taken in approving the five-year program is vested in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit pursuant to Section 23 of the OCSLA, subject to appellate review by writ of certiorari from the U.S. Supreme Court.137 A few challenges to five-year programs have been brought. The first, California ex. rel. Brown v. Watt,138 involved a variety of challenges to the 1980-1985 program and established the standard for review for legal challenges to Five-Year Programs. When reviewing "findings of ascertainable fact made by the Secretary," the court required the Secretary's decisions to be supported by "substantial evidence" as per the language of Section 23(c)(6) of the OCSLA.139 However, the court noted that many of the decisions that inform the Five-Year Program involve policy determinations, and held that such determinations should be subject to a less searching standard.140 The court summarized this review standard for challenges to Five-Year Programs:

When reviewing findings of ascertainable fact made by the Secretary, the substantial evidence test guides our inquiry. When reviewing the policy judgments made by the Secretary, including those predictive and difficult judgmental calls the Secretary is called upon to make, we will subject them to searching scrutiny to ensure that they are neither arbitrary nor irrational—in other words, we must determine whether "the decision is based on a consideration of the relevant factors and whether there has been a clear error of judgment."141

The court also noted that statutory interpretation by the agency would be subject to stricter scrutiny than either fact or policy judgments because "the interpretation of statutes is a matter which ultimately lies in the province of the judiciary."142 Based on these standards the court vacated a number of the Secretary's findings in the 1980-1985 Five-Year Program and remanded to the Secretary for revision of the Program.143

Although the reference to "arbitrary" administrative decisionmaking is reminiscent of the review standard for challenges to agency action under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), the court explained in a footnote that the agency's decisions to reject certain state recommendations before promulgating the Five-Year Program were not subject to APA review. The court noted the following:

First, the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act itself contains provisions requiring the Secretary to respond to state comments and to explain and articulate his decision ... We see no reason to engraft other provisions onto those found in this comprehensive statute ... Second, the APA itself exempts from its reach "matters relating to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts." ... Since the leasing program related to agency management of the OCS, which is undoubtedly public property ... the APA itself would appear to take the leasing program outside its scope.144

The standards for review outlined in Watt have been upheld in subsequent litigation related to the five-year program.145

Litigation under the OCSLA has also challenged actions taken during the leasing phase. As described above, the OCSLA authorizes states to submit comments during the notice of lease sale stage and directs the Secretary to accept a state's recommendations if they "provide for a reasonable balance between the national interest and the well-being of the citizens of the affected State."146 According to the cases from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, because the OCSLA does not provide clear guidance on how to balance the national interest with state considerations, agency action will generally be upheld so long as "some consideration of the relevant factors ..." takes place.147 Cases from the federal courts in Massachusetts, including a decision affirmed by the First Circuit Court of Appeals, have, while embracing this deferential standard, found the Secretary's balancing of interests insufficient.148 However, it should be noted that the Massachusetts cases reviewed agency action that was not supported by explicit analysis of the sort challenged in the Ninth Circuit. Thus, it is possible that, given a more thorough record of the Secretary's decision, these courts may afford more significant deference to the Secretary's determination.

Other litigation has focused on mandatory royalty relief provisions. In Kerr-McGee Oil & Gas Corp. v. Allred, the plaintiff, an oil and gas company operating offshore wells in the Gulf of Mexico pursuant to federal leases, challenged actions by the department to collect royalties on deepwater oil and gas production.149 The plaintiff alleged the department does not have authority to assess royalties based on an interpretation of amendments to the OCSLA found in the 1995 Outer Continental Shelf Deep Water Royalty Relief Act (DWRRA), that the act requires royalty-free production until a statutorily prescribed threshold volume of oil or gas production has been reached, and does not permit a price-based threshold for this royalty relief.150

The DWRRA separates leases into three categories based on date of issuance. These categories are (1) leases in existence on November 28, 1995; (2) leases issued after November 28, 2000; and (3) leases issued in between those periods, that is, during the first five years after the act's enactment. The third category of leases is the source of current controversy. According to Kerr-McGee, its leases, which were issued during the initial five-year period after the DWRRA's enactment, are subject to different legal requirements from those applicable to the other two categories. Kerr-McGee argued that the department has a nondiscretionary duty under the DWRRA to provide royalty relief on its deepwater leases, and that the statute does not provide an exception to this obligation based on any preset price threshold. To the extent any price threshold has been included in these leases, Kerr-McGee argued that such provisions are contrary to DOI's statutory authority and unenforceable.

Section 304 of the DWRRA, which addresses deepwater leases151 issued within five years after the DWRRA's enactment, directs that such leases use the bidding system authorized in Section 8(a)(1)(H) of the OCSLA, as amended by the DWRRA. Section 304 of the DWRRA also stipulates that leases issued during the five-year post-enactment time frame must provide for royalty suspension on the basis of volume. Specifically, Section 304 states the following:

[A]ny lease sale within five years of the date of enactment of this title, shall use the bidding system authorized in section 8(a)(1)(H) of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, as amended by this title, except that the suspension of royalties shall be set at a volume of not less than the following:

(1) 17.5 million barrels of oil equivalent for leases in water depths of 200 to 400 meters;

(2) 52.5 million barrels of oil equivalent for leases in 400 to 800 meters of water; and

(3) 87.5 million barrels of oil equivalent for leases in water depths greater than 800 meters.152

It is possible to interpret this provision as authorizing leases issued during the five-year period to contain only royalty suspension provisions that are based on production volume with no allowance at all for a price-related threshold in addition. Such an intent might be gleaned from the language of the quoted section alone; in this provision, Congress provides for a specific royalty suspension method and does not clearly authorize the Secretary to alter or supplement it. Kerr-McGee's challenge to the Secretary's authority to impose price-based thresholds on royalty suspension was based on this interpretation of the statutory language above.

The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Louisiana agreed with Kerr-McGee's interpretation of the language discussed above. The court found that the DWRRA allowed only for volumetric thresholds on royalty suspension for leases issued between 1996 and 2000, and that the Secretary did not have authority under the DWRRA to attach price-based thresholds to royalty suspension for those leases.153 On January 12, 2009, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit issued a decision affirming the district court's ruling,154 and on October 5, 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari.155

In Center for Biological Diversity v. U.S. Department of the Interior,156 the plaintiff challenged the five-year program for 2007-2012 on several grounds, including that DOI had failed to satisfy Section 18(a)(2)(G) of the OCLSA, which requires DOI to consider "the relative environmental sensitivity and marine productivity of different areas of the outer Continental Shelf."157 The court found that DOI's analysis, which relied solely on "physical characteristics" of different shoreline areas, did not satisfy the Section 18(a)(2)(G) requirements because it failed to consider non-shoreline areas of the OCS.158 The court therefore vacated the five-year program and remanded it to DOI for reconsideration. In a later order, the court clarified that this relief related only to those portions of the five-year program that addressed leasing in the Chukchi, Beaufort, and Bering Seas, as the environmental sensitivity analysis for these areas was the only analysis that was found to be deficient.159

Suits Under the National Environmental Policy Act

In the context of proposed OCS development, NEPA regulations generally require the agency to publish notice of an intent to prepare an EIS, to review comments on the scope of the EIS, to prepare a draft EIS, to hold a comment period on the draft EIS, and to publish a final EIS addressing all comments received at each stage of the leasing process where government action will significantly affect the environment.160 As described above, NEPA figures heavily in the OCS planning and leasing process and requires various levels of environmental analysis prior to agency decisions at each phase in the leasing and development process.161 Lawsuits brought under NEPA may indirectly challenge agency decisions by questioning the adequacy of the agency's environmental analysis.

In Natural Resources Defense Council v. Hodel,162 the plaintiff challenged the adequacy of the alternatives examined in the EIS and the level of consideration paid to cumulative effects of offshore drilling activities. The court held that the agency did not have to examine every possible alternative, and that the determination as to adequacy was subject to the "rule of reason."163 This standard appears to afford some level of deference to the Secretary, and his choice of alternatives was found to be sufficient by the court in this instance.164 However, without significant explanation of the standard of review to be applied, the court found that the Secretary's failure to analyze certain cumulative impacts was a violation of NEPA.165 Thus, the Secretary was required to include this analysis, although final decisions based on that analysis remained subject to the Secretary's discretion, with review only under the arbitrary and capricious standard.166

As mentioned above, NEPA plays a role in the leasing phase as well. The NEPA procedures and standard of review remain the same at this phase; however, due to the structure of the OCSLA process, more specific information is generally required.167 Still, courts are deferential at the lease sale phase. In challenges to the adequacy of environmental review, courts have stressed that inaccuracies and more stringent NEPA analysis will be available at later phases.168 Thus, because there will be an opportunity to cure any defects in the analysis as the OCSLA process continues, challenges under NEPA at this phase are often unsuccessful.

It is also possible to challenge exploration and development plans under NEPA. In Edwardsen v. U.S. Department of the Interior, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals applied the typical "rule of reason" to determine if the EIS adequately addressed the probable environmental consequences of the development and production plan, and held that, despite certain omissions in the analysis and despite an MMS decision to tier its NEPA analysis to an EIS prepared for a similar lease sale, the requirements of NEPA were satisfied.169 Thus, while additional analysis was required to account for the greater specificity of the plans and to accommodate the "hard look" at environmental impacts NEPA mandates, the reasonableness standard applied to what must be examined in an EIS did not allow for a successful challenge to agency action.