Overview

The U.S. and Afghan governments, along with partner countries, remain engaged in combat with a resilient Taliban-led insurgency. U.S. military officials increasingly refer to "momentum" against the Taliban,1 however, by some measures insurgents are in control of or contesting more territory today than at any point since 2001.2 The conflict also involves an array of other armed groups, including active affiliates of both Al Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS, ISIL, or by the Arabic acronym Da'esh). Since early 2015, the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan, known as "Resolute Support Mission" (RSM), has focused on training, advising, and assisting Afghan government forces, although combat operations by U.S. counterterrorism forces, along with some partner forces, continue and have increased since 2017.

The United States has contributed more than $120 billion in various forms of aid to Afghanistan over the past decade and a half, from building up the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) to economic development. This assistance has increased Afghan government capacity, but prospects for stability in Afghanistan appear distant. President Donald Trump announced what he termed "a new strategy" for Afghanistan and South Asia in August 2017 that prioritizes "fighting to win," downplays "nation building," and includes a stronger line against Pakistan, a larger role for India, no set timetables, expanded targeting authorities for U.S. forces, and additional troops.3 A series of large-scale Taliban-linked attacks in urban areas in late 2017 and early 2018 may be a response to elements of the new strategy.4 Administration officials state that a political settlement is the end goal of U.S. strategy, but sporadic efforts by the Afghan government and others to mitigate and eventually end the conflict through peace talks have been complicated by ethnic divisions, political rivalries, and the unsettled military situation.

The Afghan government faces domestic criticism for its failure to guarantee security and prevent insurgent gains, and for internal divisions that have spurred the formation of new political opposition coalitions. In September 2014, the United States brokered a compromise to address the disputed 2014 presidential election, in which both candidates claimed victory, but subsequent parliamentary and district council elections were postponed; after years of delay, they are now tentatively scheduled for October 2018. The Afghan government has made some notable progress in reducing corruption and implementing its budgetary commitments, and almost all measures of economic and human development have improved since the U.S.-led overthrow of the Taliban in 2001. Some U.S. policymakers still hope that the country's largely underdeveloped natural resources and/or geographic position at the crossroads of future global trade routes could improve the economic, and by extension the social and political, life of the country. Nevertheless, Afghanistan's economic and political outlook remains uncertain, if not negative, in light of ongoing hostilities.

Political Situation

The U.S.-brokered leadership partnership (referred to as the national unity government) between President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Abdullah Abdullah has encountered extensive difficulties but remains intact.5 Outward signs of tensions between the two seem to have receded in the past year, and in September 2017 the U.N.'s Special Representative for Afghanistan described them as having a "good working relationship."6 However, a trend in Afghan society and governance that worries some observers is increasing fragmentation along ethnic and ideological lines.7 Such fractures have long existed in Afghanistan but were largely contained during Hamid Karzai's presidency.8 These divisions are sometimes seen as a driving force behind some of the opposition movements that have emerged in the past year to challenge Ghani's government.

In October 2016, Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum criticized Ghani's government for favoring Pashtuns and indirectly threatened an armed challenge unless he and his Uzbek constituency were accorded greater representation.9 Several months later, Dostum was accused of engineering the kidnapping and assault of a political rival in his northern redoubt, perhaps taking advantage of central government weakness. In May 2017, Dostum left Afghanistan for Turkey, where he had sought refuge in the past, prompting speculation that his departure was an attempt to avoid facing justice in Afghanistan.10 Ghani blocked Dostum's attempt to return to Afghanistan in July 2017.

In May 2017, representatives of several ethnic parties, all of them senior government officials, visited Dostum and announced from Ankara the formation of a new political coalition.11 The group called on President Ghani to implement political reforms and introduce a less-centralized decisionmaking process. While some analysts have cast doubt on the new coalition's long-term viability, its formation represents public discontent with the government and its evident inability to provide security.12 A May 31, 2017, bombing in central Kabul that killed more than 150 people (the largest such attack in Kabul) led to large antigovernment protests in which several demonstrators were killed by security forces.13

Another group, called Mehwar-e Mardom-e Afghanistan (the People's Axis of Afghanistan), was formed in July 2017 and criticizes the NUG as "unconstitutional" because of its failure to hold elections as scheduled and other unmet conditions of the September 2014 agreement. Mehwar is seen as being aligned with former president Karzai, who may harbor ambitions to return to power and has been an increasingly vocal critic in recent months of the NUG.14 Ghani's dismissal of Atta Mohammad Noor, the powerful governor of the northern province of Balkh who defied Ghani by remaining in office for several months before resigning in March 2018, may also portend more serious political divisions, possibly along ethnic lines, in 2018.15

Parliamentary and district council elections are scheduled for October 20, 2018.16 In February 2018 testimony, Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan said, "It is vital that parliamentary ... elections take place this year."17 However, in light of the current delay (parliament's mandate expired in June 2015 but was extended indefinitely by a presidential decree due to security concerns), some are skeptical of that timeline. Continued contention among electoral commissioners18 and an ethnically motivated dispute over electronic identity cards may further challenge the government's ability to hold elections this year.19 Some observers have called for district council elections to be delayed further and held alongside the 2019 presidential election, arguing that holding them before broader questions of local governance and autonomy are settled "risks perpetuating the long-standing fallacy in Afghan statebuilding: if subnational structures are built on paper, state legitimacy will follow."20

Reconciliation Efforts and Obstacles

For years, the U.S. and Afghan governments and various neighboring states have engaged in efforts to bring about a political settlement with insurgents.21 Because of many insurgents' views on religious freedom, women's rights, and other issues, a settlement is likely to require compromises that could adversely affect human rights in Afghanistan. The Obama Administration backed reconciliation with the stipulation that any settlement be Afghan-led and require insurgent leaders to (1) cease fighting, (2) accept the Afghan constitution, and (3) sever any ties to Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.22

In 2011, U.S. diplomats held their first meetings with Taliban officials of the post-2001 period, and subsequent U.S.-Taliban meetings led to the May 31, 2014, release of U.S. prisoner of war Bowe Bergdahl in exchange for the release to Qatar of five senior Taliban captives from the Guantanamo detention facility. An agreement to reopen the Taliban office in Qatar (first opened in June 2013 and closed shortly thereafter under U.S. pressure) also was reached in 2014, and that office remains the Taliban's sole official representation. President Trump and others in the U.S. and Afghan governments reportedly support closing the office, criticizing its evident failure to contribute to a meaningful political settlement.23 Others warn that the office's closure could strengthen the hands of hardliners in the Taliban who argue that the Afghan government is not serious about talks.24

It is unclear what precedence reconciliation takes in President Trump's new approach to Afghanistan. In his August 2017 speech laying out the new strategy (more below), he referred to a "political settlement" as an outcome of an "effective military effort," but did not elaborate on what U.S. goals or conditions might be as part of this putative political process. In remarks the next day, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson rejected the idea of preconditioning talks on the Taliban's acceptance of certain arrangements, saying "the Government of Afghanistan and the Taliban representatives need to sit down and sort this out. It's not for the U.S. to tell them it must be this particular model, it must be under these conditions."25

Messages from the Trump Administration since the announcement of the new strategy have been mixed. U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley said in January 2018 that "they [the Afghan government] are starting to see the Taliban concede, they are starting to see them move towards coming to the table,"26 while Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan stated that same month that "there has been no reciprocal interest on the part of the Taliban" in response to the Afghan government's desire for peace talks.27 The latter assessment aligns with one analysis that described 2017 as "a lost year for Afghan peace" and stated that "a political breakthrough is not on the horizon" in 2018.28 President Trump in late January 2018 expressed a similar judgment on the lack of talks, adding that "We don't want to talk to the Taliban," in what has been described as "an apparent contradiction of his own strategy."29

In June 2017, President Ghani launched the Kabul Process on Peace and Security, the first Afghan-led forum to work toward a negotiated settlement. Speaking at the second meeting of the Kabul Process in February 2018, President Ghani offered direct talks with the Taliban "without preconditions" and proposed confidence-building measures such as prisoner exchanges.30 The Taliban has not responded to that offer (it has rejected similar overtures from Kabul in the past) but has long declared its willingness to negotiate directly with the United States.31 That is a nonstarter for the United States; the official U.S. position is that the Taliban can only negotiate with the Afghan government.32

Military and Security Situation

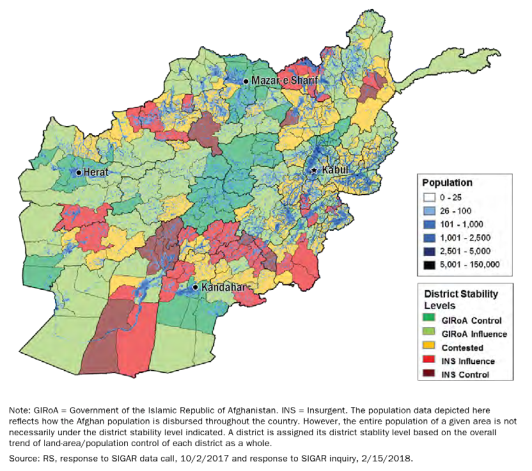

While U.S. commanders assert that the ANDSF is performing well despite taking heavy casualties, insurgent forces retain, and by some measures are increasing, their ability to contest and hold territory as well as to launch high profile attacks. The Taliban has made gains in Helmand province (of which the Taliban controls about half) and elsewhere in the south, which is considered to be the group's stronghold, while showing signs of strength even outside their traditional bases of operations (see Figure 1). The Taliban's week-long capture of Kunduz city in northern Afghanistan in September 2015 was the first seizure of a significant city since the Taliban regime fell in 2001. In the years since, the Taliban has encroached on other population centers throughout Afghanistan but has ultimately failed to take any provincial capitals despite multiple attempts, a fact often repeated by U.S. officials.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Joseph Dunford testified in September 2016 that the battlefield situation represented "roughly a stalemate," an assessment that was echoed by RSM Commander General John Nicholson in February 2017 and again in November 2017.33 In early 2018, Dunford, Nicholson, and other U.S. officials describe themselves as more encouraged, citing the new strategy (more below) to justify their optimism.34 Outside assessments are generally more negative; in February 2018, former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel called the situation in Afghanistan "worse than it's ever been," adding that "the American military can't fix the problems in Afghanistan."35

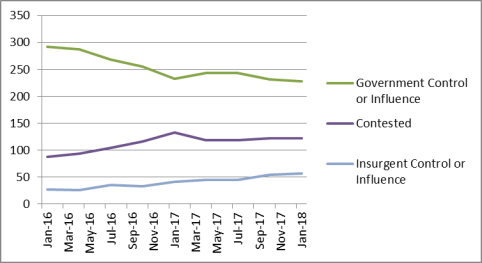

Arguably complicating assessments that the situation in Afghanistan is a "stalemate" or improving, the extent of territory controlled or contested by the Taliban has steadily grown in recent years by most measures. In its January 2018 report, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) reported that the percentage of districts under government control or influence has fallen to 56%, the lowest level recorded in the two years SIGAR has reported that metric, with 14% under the control or influence of insurgents, and the remaining 30% contested.36 Perhaps a more serious threat is the Taliban's continued ability to inflict on Afghan forces a level of casualties described by SIGAR as "shocking," although ANDSF casualty rates were recently classified.37

|

Figure 1. Insurgent Activity in Afghanistan by District As of October 15, 2017 |

|

|

Source: SIGAR, Addendum to January 2018 Quarterly Report. |

The May 2016 killing of then-Taliban head Mullah Mansour by a U.S. strike demonstrated Taliban vulnerabilities to U.S. intelligence and combat capabilities, although it did not have a measurable effect on Taliban effectiveness. It is unclear to what extent current leader Haibatullah Akhundzada exercises effective control over the group and how he is viewed within its ranks.38 In November 2017, General Nicholson said "we are seeing signs of friction and disagreement within the Taliban leadership ranks" and that, having failed to capture any cities, "the Taliban failed to meet any of their military objectives" in 2017.39

|

|

Source: SIGAR Quarterly Reports. Notes: The y-axis represents the number of districts, of which the U.S. government counts 407 in Afghanistan. |

A series of large-scale Taliban-linked attacks in Kabul in recent months (including an assault on the Intercontinental Hotel that killed more than 40, including 4 Americans, and a bombing in a central Kabul market that killed more than 100, both in January 2018) has led to speculation that the group is now pursuing a new strategy more focused on urban attacks. Some argue that the strategy reflects the long-standing Taliban goal of "undermining the state" and sowing "chaos" by carrying out "attacks in Kabul that expose the government's weakness."40 Others link the trend directly to the increased level of U.S. military action against the Taliban in its traditional bases of operation in the rural south as part of the new U.S. strategy; one outlet, quoting a Taliban source, reports that "U.S. airstrikes have forced a lot of Taliban to lie low and stay calm in the countryside.... As a result, to keep the heat up, we are attacking more and more in Kabul."41 The Trump Administration's recent decision to hold back some aid to Pakistan is also seen by some as potentially tied to the recent string of attacks.42

Beyond the anti-Taliban effort, a significant share of U.S. operations are aimed at the local IS affiliate, known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP). This group appears to be a growing factor in U.S. and Afghan strategic planning, although there is debate over the degree of threat the group poses.43 According to media accounts, of the 14 U.S. battlefield casualties in 2017, as many as 9 were killed in anti-ISKP operations,44 along with at least 2 CIA personnel.45 ISKP and Taliban fighters have sometimes fought over control of territory or because of political or other differences.46 However, some sources claim that the two groups have also conducted joint operations, an indication of the increasingly fluid and complex militant landscape, particularly in the north.47 ISKP has claimed responsibility for a number of large-scale attacks, including multiple bombings targeting Afghanistan's Shiite minority in what is generally seen as an attempt to foment sectarian conflict.

ANDSF Development and Deployment

The effectiveness of the ANDSF is key to the security of Afghanistan. Since 2014, the United States generally has provided around 75% of the estimated $5 billion a year to fund the ANDSF, with the balance coming from U.S. partners ($1 billion annually) and the Afghan government ($500 million). Congress appropriated $4.1 billion for the ANDSF in FY2015 and $3.65 billion in FY2016 (slightly lower than the $3.75 billion requested by the Obama Administration). The FY2018 NDAA conference report authorizes the full request of $4.9 billion for the Afghanistan Security Forces Fund, and sets as a goal the use of $41 million to increase the recruitment of women to the ANDSF.

Major concerns about the ANDSF raised by SIGAR, DOD, and others include

- absenteeism and the fact that about 35% of the force does not reenlist each year, and that the rapid recruitment might dilute the force's quality;48

- widespread illiteracy within the force;49

- credible allegations of child sexual abuse and other potential human rights abuses;50 and

- casualty rates often described as unsustainable, including over 6,700 combat deaths in 2016 (up from 5,500 the previous year) and "about 10,000" in 2017.51

Key metrics related to ANDSF performance, such as casualties, attrition rates, and personnel strength, were classified by U.S. Forces-Afghanistan (USFOR-A) in the October 2017 SIGAR quarterly report and remain withheld; SIGAR previously published those metrics as part of its quarterly reports.52

Components of the ANDSF include:

The Afghan National Army (ANA). Of its authorized size of 195,000, the ANA (all components) has about 175,000 personnel. Its special operations component, trained by U.S. Special Operations Forces, numbers nearly 20,000, and is used extensively to reverse Taliban gains: their efforts reportedly make up 70%-80% of the fighting.53

Afghan Air Force (AAF). Afghanistan's Air Force has emerged as a key component of the ANDSF's efforts to combat the insurgency, and is an increasing focus of U.S. advisory and support operations. It has been mostly a support force but, since 2014, has progressively increased its bombing operations in support of coalition ground forces, mainly using the Brazil-made A-29 Super Tucano. In May 2018, Afghan pilots are scheduled to begin flying U.S. UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters; the United States is slated to procure around 30 Black Hawks for the AAF by the end of 2018 as part of a plan to replace the current Afghan fleet of 46 aging Russian-origin Mi-17s with 159 Black Hawks by 2023.54 The AAF has had about 8,400 personnel, its target size, for several years. Since FY2010, the United States has obligated more than $3.2 billion for the AAF, including nearly $1 billion for equipment and aircraft, resulting in some "notable accomplishments."55

Afghan National Police (ANP). U.S. and Afghan officials believe that a credible and capable national police force is critical to combating the insurgency. However, many outside assessments of the ANP are negative, asserting that there is rampant corruption to the point where citizens mistrust and fear the ANP. DOD reports acknowledge that the force has a higher desertion rate than does the ANA, substantial illiteracy, and involvement in local factional or ethnic disputes. The target size of the ANP, including all forces under the ANP umbrella (except the Afghan Local Police), is 162,000 personnel. The force has about 150,000 personnel, of which about 3,200 are women.

U.S. Troop Levels and Authorities

At a February 2017 Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, General Nicholson indicated that the United States has a "shortfall of a few thousand" troops that, if filled, could help break the "stalemate." He further clarified that while the number of Special Operations forces is sufficient to conduct operations, more troops are needed for advising and training Afghan forces, particularly at lower levels in the chain of command.56 Initial reports indicated that the Trump Administration was likely to approve Nicholson's request. However, a National Security Council-led review of U.S. strategy that included plans for more troops was reportedly held up due to disagreements within the Administration over the path forward in Afghanistan.57 Some participants reportedly expressed skepticism that a few thousand more troops could meaningfully impact dynamics on the ground, pointing to previous "surges" that did not do so, and raised concerns about an open-ended U.S. commitment in a country where U.S. troops have already been deployed for nearly two decades. Others countered that the relative cost of the U.S. commitment in Afghanistan is a worthy investment when viewed against the cost of a terrorist attack the absence of U.S. forces might allow, comparing it to "term-life insurance."58

In August 2017, media outlets reported that the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan, estimated at around 8,400 by the Pentagon, was actually around 11,000 on any given day due to units rotating in and out of theater;59 that level was officially confirmed by the Pentagon later that month. President Trump delegated to Secretary Mattis the authority to set force levels, reportedly limited to around 3,500 additional troops, in June 2017; Secretary Mattis signed orders to deploy them in September 2017.60 As of September 30, 2017, those additional forces (all of which are dedicated to RSM) have arrived in Afghanistan, putting the total number of U.S. troops in the country at around 15,000, with the deployment of another 1,000 reportedly under consideration.61

|

NATO Contribution The current train, advise, and assist mission in Afghanistan, Resolute Support Mission (RSM), is led by NATO, and NATO partners have been heavily engaged in Afghanistan since 2001. At its height in 2012, the number of NATO and non-NATO partner forces in Afghanistan reached 130,000, around 100,000 of whom were American. As of May 2017 (the last month NATO released official troop level data), RSM was made up of around 13,000 troops from 39 countries, of whom 6,900 were American. In his South Asia strategy speech, President Trump alluded to NATO supporting the new strategy with "additional troop and funding increases in line with our own." In November 2017, NATO announced plans to increase forces in Afghanistan by around 3,000, bringing the RSM level to about 16,000.62 NATO also confirmed that it will continue to fund the ANDSF through at least 2020. |

Beyond additional troops, U.S. forces now have broader authority to operate independently of Afghan forces and "attack the enemy across the breadth and depth of the battle space," expanding the list of targets to include those related to "revenue streams, support infrastructure, training bases, infiltration lanes."63 This was demonstrated in a November 2017 operation against Taliban drug labs in Helmand province. The operation, highlighted by U.S. and Afghan officials, sought to degrade what is widely viewed as one of the Taliban's most important sources of revenue, namely the cultivation, production, and trafficking of narcotics.64 It was carried out by U.S. B-52 and F-22 combat aircraft (the first use of the latter in combat in Afghanistan) alongside Afghan A-29s. Some have questioned the impact of these strikes, especially in the context of the United States' overall counternarcotics strategy.65 In November 2017, the United Nations reported that the total area used for poppy cultivation in 2017 reached an all-time high of 328,000 hectares, an increase of 63% from 2016 and 46% higher than the previous record in 2014; similarly, opium production increased by 87%.66 Overall, the amount of U.S. munitions used in Afghanistan has increased significantly, with 4,361 weapons released in 2017 (up from 1,337 in 2016), the highest annual figure since 2011. In early 2018, "Afghanistan has become CENTCOM's main effort" as U.S. operations in Iraq and Syria wind down.67

|

New U.S. Strategy In a national address on August 21, 2017, President Trump announced a "new strategy" for Afghanistan and South Asia that includes several pillars:

Despite widespread expectations that he would describe specific elements of the new strategy, particularly the prospects for the deployment of additional troops, President Trump stated "we will not talk about numbers of troops or our plans for further military activities."68 Criticizing the previous Administration's use of "arbitrary timetables," the President did not specify what conditions on the ground might necessitate or allow for alterations to the strategy going forward. Some have characterized the strategy as "short on details" and serving "only to perpetuate a dangerous status quo."69 Others welcomed the strategy, contrasting it favorably with proposed alternatives such as a full withdrawal of U.S. forces (which President Trump conceded was his "original instinct") or heavy reliance on contractors.70 General John Nicholson, the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, has cited both new troops and expanded authorities in saying that, with the new strategy, "we've set all the conditions to win,"71 a line echoed by other senior U.S. military leaders.72 |

Pakistan and Other Neighbors

Afghanistan has been a participant in numerous regional security and economic platforms, and the United States has encouraged Afghanistan's neighbors to support a stable and economically viable Afghanistan.

The neighbor considered most crucial to Afghanistan's security is Pakistan. President Trump has issued harsh rhetoric about Pakistan's role in "housing the very terrorists that we are fighting."73 Afghan leaders, along with U.S. military commanders, attribute much of the insurgency's power and longevity either directly or indirectly to Pakistan; President Ghani said in June 2017 that Pakistan was waging an "undeclared war of aggression" on his country.74 Experts debate the extent to which Pakistan is committed to Afghan stability or is attempting to exert control in Afghanistan through ties to insurgent groups, most notably the Haqqani Network, which is an official, semiautonomous component of the Taliban.75 DOD reports on Afghan stability have repeatedly identified militant safe havens in Pakistan as a threat to security in Afghanistan, though some question the validity of that charge in light of the Taliban's increased territorial control within Afghanistan itself.76

Pakistan sees Afghanistan as potentially providing it with strategic depth against India.77 Pakistan may also view a weak and destabilized Afghanistan as preferable to a strong, unified Afghan state (particularly one led by a Pashtun-dominated government in Kabul). However, at least some Pakistani leaders have expressed the belief that instability in Afghanistan could rebound to Pakistan's detriment; Pakistan faces an indigenous Islamist insurgency of its own.78 Pakistan may also anticipate that improved relations with Afghanistan's leadership could limit India's influence in Afghanistan.

About 2 million Afghan refugees have returned from Pakistan since 2001, but approximately 2.5 million more remain in Pakistan and Pakistan is pressing many of them to return; the forced return of several hundred thousand since 2016 may raise questions about international law and exacerbate humanitarian problems in Afghanistan.79 Afghanistan-Pakistan relations are further complicated by a long-standing border dispute over which violence has broken out on several occasions (Kabul does not accept the 1893 "Durand Line" as a legitimate international border).

Afghanistan largely maintains cordial ties with its other neighbors, including the post-Soviet states of Central Asia, though some warn that rising instability in Afghanistan may complicate those relations.80 In the past year, multiple U.S. commanders have warned of increased levels of assistance, and perhaps even material support, for the Taliban from Russia and Iran, both of which cite IS presence in Afghanistan to justify their activities.81 Both nations were opposed to the Taliban government of the late 1990s, but reportedly see the Taliban as a useful point of leverage vis-a-vis the United States.

Revised Regional Approach

In his August 2017 speech, President Trump identified a new approach to Pakistan, saying "We can no longer be silent about Pakistan's safe havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban, and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond."82 In the same speech, President Trump praised Pakistan as a "valued partner," citing the close U.S.-Pakistani military relationship. U.S.-Pakistan cooperation in the October 2017 operation to free American citizen Caitlin Coleman and her family, who were held by the Haqqani network for five years, was praised by the Administration as a "sign that [Pakistan] is honoring America's wishes for it to do more to provide security in the region."83

However, the Trump Administration announced in January 2018 plans to suspend security assistance to Pakistan in a decision that could impact hundreds of millions of dollars in aid.84 The move could also provoke retaliatory measures from Pakistan, including the closure of air and ground supply routes used to supply U.S. and coalition forces, though no such actions have been taken to date.85 In February 2018, CENTCOM Commander General Joseph Votel stated, "Recently we have started to see an increase in communication, information sharing, and actions on the ground," but that these "positive indicators" have "not yet translated into the definitive actions we require Pakistan to take against Afghan Taliban or Haqqani leaders."86

President Trump also praised India in his speech, encouraging it to play a greater role in Afghanistan's economic development; this, along with other Administration messaging, has compounded traditional Pakistani concerns over Indian activity in Afghanistan.87 India has been the largest regional contributor to Afghan reconstruction, but New Delhi has not shown an inclination to pursue a deeper defense relationship with Kabul. Afghans themselves may be divided on the wisdom of actively cultivating stronger ties with India.88 Neither Iran nor Russia was mentioned in the President's speech, and it is unclear how, if at all, the U.S. approach to them might change as part of the new strategy.

Economy and U.S. Aid

Economic development is pivotal to Afghanistan's long-term stability, though indicators of future growth are mixed. Decades of war have stunted the development of most domestic industries, including mining.89 The economy has also been hurt by a steep decrease in the amount of aid provided by international donors. Afghanistan's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has grown an average of 7% per year since 2003, but aid cutbacks and political uncertainty about the post-2104 security situation caused a slowing to 2% growth in 2013 and a further reduction in growth to between 1% and 2% 2014-2017, with a slight recovery forecast for 2018.90 Social conditions in Afghanistan remain equally mixed. On issues ranging from human trafficking91 to religious freedom to women's rights, Afghanistan has, by all accounts, made significant progress since 2001, but future prospects in these areas remain uncertain.

Congress has appropriated more than $120 billion in aid for Afghanistan since FY2002, with about 63% for security and 28% for development (and the remainder for civilian operations, mostly budgetary assistance, and humanitarian aid).92 President Trump's FY2019 budget requests $5.2 billion for the ANDSF, $500 million in Economic Support Funds, and smaller amounts to help the Afghan government with tasks like combatting narcotics trafficking. This is roughly even with the overall FY2017 enacted level of about $5.6 billion (down from nearly $17 billion in FY2010). This figure does not include the cost of U.S. combat operations in Afghanistan (including related regional support activities), which was estimated at a total of $752 billion since FY2001 in a July 2017 DOD report, with approximately $45 billion requested for each of FY2017 and FY2018.93

Outlook

Given the continued battlefield stalemate, and the Trump Administration's new, mostly military-focused strategy intended to reverse it, many view the termination of the conflict as the most important determinant of Afghanistan's future and the success of U.S. efforts there. Meanwhile, the increase in Taliban attacks throws the security challenge into sharp relief, and insurgent and terrorist groups may make further gains in 2018. Nevertheless, political dynamics, particularly the increasing willingness of political actors to directly challenge the legitimacy and authority of the central government, even by extralegal means, may pose an even more serious threat to Afghan stability in 2018 and beyond.94

After 16 years of war, Members of Congress and other U.S. policymakers may seek to challenge or broaden their conceptions of what "victory" in Afghanistan looks like, examining the array of potential outcomes, how these outcomes might harm or benefit U.S. interests, and what the relative levels of U.S. engagement required to attain them are.95 U.S. policymakers seek to achieve an insurmountable advantage over the insurgency on the battlefield through increased U.S. military presence and by capitalizing on the enhanced capacity of the ANDSF. At the same time, they may also examine how the United States can leverage its assets, influence, and experience in Afghanistan, as well as those of Afghanistan's neighbors and international organizations, to encourage and perhaps incentivize more equal and inclusive service delivery and governance.