Introduction

This report presents background information and issues for Congress concerning the Navy's force structure and shipbuilding plans. The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the rate of Navy ship procurement, and the prospective affordability of the Navy's shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years.

The Navy's FY2019 budget submission includes proposed increases in shipbuilding rates that are intended as initial steps for increasing the size of the Navy toward a goal of a fleet with 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The Navy's proposed FY2019 budget requests funding for the procurement of 10 new ships, including two Virginia-class attack submarines, three DDG-51 class Aegis destroyers, one Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), two John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers, one Expeditionary Sea Base ship (ESB), and one TATS towing, salvage, and rescue ship.

The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy's proposed FY2019 shipbuilding program and the Navy's longer-term shipbuilding plans. Decisions that Congress makes on this issue can substantially affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements, and the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base.

Detailed coverage of certain individual Navy shipbuilding programs can be found in the following CRS reports:

- CRS Report R41129, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report R44972, Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RL33741, Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report R43543, Navy LX(R) Amphibious Ship Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. (This report also covers the issue of funding for the procurement of San Antonio [LPD-17] class amphibious ships.)

- CRS Report R43546, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

For a discussion of the strategic and budgetary context in which U.S. Navy force structure and shipbuilding plans may be considered, see Error! Reference source not found..

Background

Navy's 355-Ship Ship Force-Structure Goal

Introduction

On December 15, 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal is the result of a Force Structure Assessment (FSA) conducted by the Navy in 2016. An FSA is an analysis in which the Navy solicits inputs from U.S. regional combatant commanders (CCDRs) regarding the types and amounts of Navy capabilities that CCDRs deem necessary for implementing the Navy's portion of the national military strategy, and then translates those CCDR inputs into required numbers of ships, using current and projected Navy ship types. The analysis takes into account Navy capabilities for both warfighting and day-to-day forward-deployed presence.1 The Navy conducts an FSA every few years, as circumstances require, to determine its force-structure goal.

The 355-ship force-level goal replaced a 308-ship force-level goal that the Navy released in March 2015. Table 1 compares the 355-ship force-level goal to the previous 308-ship force-level goal. As can be seen in the table, compared to the 308-ship goal, the 355-ship goal includes 47 additional ships, or about 15% more ships, including one aircraft carrier, 18 attack submarines (SSNs), 16 large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers), four amphibious ships, three oilers, three ESBs, and two command and support ships. The 34 additional SSNs and large surface combatants account for about 72% of the 47 additional ships.

The 355-ship force-level goal is the largest force-level goal that the Navy has released since a 375-ship force-level goal that was in place in 2002-2004. In the years between that 375-ship goal and the 355-ship goal, Navy force-level goals were generally in the low 300s (see Appendix B). The force level of 355 ships is a goal to be attained in the future; the actual size of the Navy in recent years has generally been between 270 and 290 ships.

Made U.S. Policy by FY2018 NDAA

Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act, or NDAA (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115-91 of December 12, 2017) states:

SEC. 1025. Policy of the United States on minimum number of battle force ships.

(a) Policy.—It shall be the policy of the United States to have available, as soon as practicable, not fewer than 355 battle force ships, comprised of the optimal mix of platforms, with funding subject to the availability of appropriations or other funds.

(b) Battle force ships defined.—In this section, the term "battle force ship" has the meaning given the term in Secretary of the Navy Instruction 5030.8C.

The term battle force ships in the above provision refers to the ships that count toward the quoted size of the Navy in public policy discussions about the Navy.2

|

Ship type |

355-ship goal of December 2016 |

308-ship goal of March 2015 |

Difference |

Difference (%) |

Number of ships that would need to be added to 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve and maintain 355-ship fleet (unless the Navy extends the service lives of existing ships beyond currently planned figures and/or reactivates recently retired ships) |

|

|

CRS 2017 estimate of addition to Navy FY17 30-year (FY17-FY46) shipbuilding plan to maintain 355-ship fleet through end of 30-year period (i.e., through FY2046) |

CBO 2017 estimate of addition to notional FY18 30-year (FY18-FY47) shipbuilding plan to maintain 355-ship fleet 10 years beyond end of 30-year period (i.e., through FY2057) |

|||||

|

Ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) |

12 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Attack submarines (SSNs) |

66 |

48 |

18 |

37.5 |

19 |

16 to 19 |

|

Aircraft carriers (CVNs) |

12 |

11 |

1 |

9.1 |

2 |

4 |

|

Large surface combatants (LSCs) (i.e., cruisers and destroyers) |

104 |

88 |

16 |

18.2 |

23 |

24 to 25 |

|

Small surface combatants (i.e., LCSs, frigates, mine warship ships) |

52 |

52 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

10 |

|

Amphibious ships |

38 |

34 |

4 |

11.8 |

0 to 5 |

7 |

|

Combat logistic force (CLF) ships (i.e., resupply ships) |

32 |

29 |

3 |

10.3 |

2 or 3 |

5 |

|

Expeditionary Fast transports (EPFs) |

10 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Expeditionary Support Base ships (ESBs) |

6 |

3 |

3 |

100 |

3 |

3 |

|

Command and support ships |

23 |

21 |

2 |

9.5 |

0 to 4 |

4 |

|

TOTAL |

355 |

308 |

47 |

15.3 |

57 to 67 |

73 to 77 |

|

Average additional shipbuilding funds per year needed over 30-year period, compared to amounts needed to implement FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan |

$4.6 billion per year to $5.1 billion per year in additional funds, using today's shipbuilding costs |

About $5.4 billion per year in additional funds, in constant FY2017 dollars |

||||

|

Average additional shipbuilding funds + ship operation and support (O&S) costs per year to maintain Navy's 355-ship fleet once it is achieved |

not estimated |

$11 billion per year to $23 billion per year in FY2017 dollars, not including additional costs for manned aircraft, unmanned systems, and weapons. |

||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on U.S. Navy data and information provided to CRS by CBO on April 26, 2017. The CRS and CBO estimates shown in the final two columns assume no service life extensions of existing Navy ships and no reactivations of retired Navy ships.

Notes: EPFs were previously called Joint High Speed Vessels (JHSVs). ESBs were previously called Afloat Forward Staging Base ships (AFSBs). The figures for additional small surface combatants shown in the final two columns are the net results of adding 12 small surface combatants in the earlier years of the 30-year plan and removing 4 or 2 small surface combatants, respectively, from the later years of the 30-year plan.

Part of Navy the Nation Needs (NNN) Vision

The Navy's 355-ship force-level goal forms part of a Navy vision for its future that the Navy refers to as the Navy the Nation Needs (NNN). The Navy says the NNN vision consists of six pillars—readiness, capability, capacity, manning, networks, and operating concepts.3 The 355-force-level goal is arguably most closely associated with the capacity pillar. The Navy states:

The Navy's overarching plan in support of the NDS [National Defense Strategy] is referred to as the Navy the Nation Needs (NNN). The six pillars of the NNN are Readiness, Capability, Capacity, Manning, Networks, and Operating Concepts. These six pillars must remain balanced and scalable in order to field the needed credible naval power, guarding against over-investment in one area that might disadvantage another. This disciplined approach ensures force structure growth accounts for commensurate, properly phased investments across all six pillars—a balanced warfighting investment strategy to fund the total ownership cost of the Navy (manning, support, training, infrastructure, etc.)....

[The] Navy will proactively invest above the baseline steady [shipbuilding] profiles [shown in the FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan] if [the Navy is] also able to remain balanced [in terms of investments] across the [six] NNN pillars.4

Apparent Reasons for Increasing Force-Level Goal from 308 Ships

The roughly 15% increase in the 355-ship goal over the previous 308-ship goal can be viewed as a Navy response to, among other things, China's continuing naval modernization effort;5 resurgent Russian naval activity, particularly in the Mediterranean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean;6 and challenges that the Navy has sometimes faced, given the current total number of ships in the Navy, in meeting requests from the various regional U.S. combatant commanders for day-to-day in-region presence of forward-deployed Navy ships.7 To help meet requests for forward-deployed Navy ships, Navy officials in recent years have sometimes extended deployments of ships beyond (sometimes well beyond) the standard length of seven months, leading to concerns about the burden being placed on Navy ship crews, wear and tear on Navy ships, and fleet readiness.8 Navy officials have testified that fully satisfying requests from regional U.S. military commanders for forward-deployed Navy ships would require a fleet of substantially more than 308 ships. For example, Navy officials testified in March 2014 that fully meeting such requests would require a Navy of 450 ships.9 In releasing its 355-ship goal on December 15, 2016, the Navy stated that

Since the last full FSA was conducted in 2012, and updated in 2014, the global security environment changed significantly, with our potential adversaries developing capabilities that challenge our traditional military strengths and erode our technological advantage. Within this new security environment, defense planning guidance directed that the capacity and capability of the Joint Force must be sufficient to defeat one adversary while denying the objectives of a second adversary.10

Compared to Trump Campaign Organization Goal of 350 Ships

The figure of 355 ships appears close to an objective of building toward a fleet of 350 ships that was mentioned by the Trump campaign organization during the 2016 presidential election campaign. The 355-ship goal, however, is a product of the Navy's 2016 FSA, and thus reflects the national military strategy that was in place in 2016 (i.e., the Obama Administration's national military strategy),11 while the Trump campaign organization's 350-ship goal appears to have had a different origin.12 In addition, the 355-ship goal is a fully delineated force-level goal, with specified numbers for various ship types that add up to 355 ships, while the 350-ship figure was a topline number only, without a supporting set of specified numbers for various ship types.13

Additional Shipbuilding Needed to Achieve and Maintain 355-Ship Fleet

CRS and CBO Estimates

Although the 355-ship force-level goal includes 47 more ships than the previous 308-ship force-level goal, as shown in the final two columns of Table 1, more than 47 ships would need to be added to the Navy's previous 30-year shipbuilding plan—the FY2017 30-year (FY2017-FY2046) shipbuilding plan14—to achieve and maintain the Navy's 355-ship fleet, unless the Navy extends the service lives of existing ships beyond currently planned figures and/or reactivates recently retired ships. This is because the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan did not include enough ships to fully populate all elements of the 308-ship fleet across the entire 30-year period, and because some ships that will retire over the 30-year period that would not need to be replaced to maintain the 308-ship fleet would need to be replaced to maintain the 355-ship fleet. As shown in the final two columns of Table 1:

- CRS estimated in 2017 that 57 to 67 ships would need to be added to the Navy's FY2017 30-year (FY2017-FY2046) shipbuilding plan to achieve the Navy's 355-ship fleet and maintain it through the end of the 30-year period (i.e., through FY2046), unless the Navy extends the service lives of existing ships beyond currently planned figures and/or reactivates recently retired ships.

- The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated in 2017 that 73 to 77 ships would need to be added to a CBO-created notional version of the Navy's FY2018 30-year (FY2018-FY2047) shipbuilding plan15 to achieve the Navy's 355-ship fleet and maintain it not only through the end of the 30-year period (i.e., through FY2047), but another 10 years beyond the end of the 30-year period (i.e., through FY2057), unless the Navy extends the service lives of existing ships beyond currently planned figures and/or reactivates recently retired ships.16

Time Needed to Achieve 355-Ship Fleet

Even with increased shipbuilding rates, achieving certain parts of the 355-ship force-level goal—particularly the 12-ship goal for aircraft carriers and the 66-boat goal for SSNs—could take many years. CBO estimated in 2017 that the earliest the Navy could achieve all elements of the 355-ship fleet would be 2035.17 Extending the service lives of existing ships and/or reactivating retired ships could accelerate the attainment of certain parts of the 355-ship force structure.18

Cost to Achieve and Maintain 355-Ship Fleet

Shipbuilding Costs

Procuring the additional ships needed to achieve and maintain the Navy's 355-ship fleet would require several billion dollars per year in additional shipbuilding funds. As shown in Table 1:

- CRS estimated in 2017 that procuring the 57 to 67 ships that would need to be added to the Navy's FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve the Navy's 355-ship fleet and maintain it through FY2046 (unless the Navy extends the service lives of existing ships beyond currently planned figures and/or reactivates recently retired ships) would notionally cost an average of roughly $4.6 billion to $5.1 billion per year in additional shipbuilding funds over the 30-year period, using today's shipbuilding costs.

- CBO estimated in 2017 that procuring the 73 to 77 ships that would need to be added to the CBO-created notional version of the Navy's FY2018 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve the Navy's 355-ship fleet and maintain it through FY2057 (unless the Navy extends the service lives of existing ships beyond currently planned figures and/or reactivates recently retired ships) would cost, in constant FY2017 dollars, an average of $5.4 billion per year in additional shipbuilding funds over the 30-year period.19

Aircraft Procurement Costs

CBO estimated in 2017 that procuring the additional ship-based aircraft associated with the Navy's 355-ship force-level goal—including an additional carrier air wing for an aircraft carrier, plus additional aircraft (mostly helicopters) for surface combatants and amphibious ships—would require about $15 billion in additional funding for aircraft procurement.20

Shipbuilding Plus Operation and Support (O&S) costs

As shown in Table 1, the above additional shipbuilding and aircraft procurement funds are only a fraction of the total costs that would be needed to achieve and maintain the Navy's 355-ship fleet instead of the Navy's previously envisaged 308-ship fleet. CBO estimated in 2017 that, adding together both shipbuilding costs and ship operation and support (O&S) costs, the Navy's 355-ship fleet would cost an average of about $11 billion to $23 billion more per year in constant FY2017 dollars than the Navy's previously envisaged 308-ship fleet. This figure does not include additional costs for manned aircraft, unmanned systems, and weapons.21

As noted earlier, the 355-ship force-level goal is 47 ships higher than the previous 308-ship force-level goal. CRS estimated in 2017 that a total of roughly 15,000 additional sailors and aviation personnel would be needed at sea to operate those 47 additional ships.22 The Navy testified in May 2017 that the Navy would need a total of 20,000 to 40,000 more sailors both at sea and ashore to operate and provide shore-based support for a fleet of about 350 ships, depending on the composition of that 350-ship fleet, than the Navy in 2017 had both at sea and ashore for operating and providing shore-based support for the 2017 fleet of about 275 ships.23

Industrial Base Ability for Taking on Additional Shipbuilding Work

The U.S. shipbuilding industrial base has some unused capacity to take on increased Navy shipbuilding work, particularly for certain kinds of surface ships, and its capacity could be increased further over time to support higher Navy shipbuilding rates. Navy shipbuilding rates could not be increased steeply across the board overnight—time (and investment) would be needed to hire and train additional workers and increase production facilities at shipyards and supplier firms, particularly for supporting higher rates of submarine production. Depending on their specialties, newly hired workers could be initially less productive per unit of time worked than more experienced workers.

Some parts of the shipbuilding industrial base, such as the submarine construction industrial base, could face more challenges than others in ramping up to the higher production rates required to build the various parts of the 355-ship fleet. Over a period of a few to several years, with investment and management attention, Navy shipbuilding could ramp up to higher rates for achieving a 355-ship fleet over a period of 20 to 30 years. An April 2017 CBO report stated that

all seven shipyards [currently involved in building the Navy's major ships] would need to increase their workforces and several would need to make improvements to their infrastructure in order to build ships at a faster rate. However, certain sectors face greater obstacles in constructing ships at faster rates than others: Building more submarines to meet the goals of the 2016 force structure assessment would pose the greatest challenge to the shipbuilding industry. Increasing the number of aircraft carriers and surface combatants would pose a small to moderate challenge to builders of those vessels. Finally, building more amphibious ships and combat logistics and support ships would be the least problematic for the shipyards. The workforces across those yards would need to increase by about 40 percent over the next 5 to 10 years. Managing the growth and training of those new workforces while maintaining the current standard of quality and efficiency would represent the most significant industrywide challenge. In addition, industry and Navy sources indicate that as much as $4 billion would need to be invested in the physical infrastructure of the shipyards to achieve the higher production rates required under the [notional] 15-year and 20-year [buildup scenarios examined by CBO]. Less investment would be needed for the [notional] 25-year or 30-year [buildup scenarios examined by CBO].24

For additional background information on the ability of the industrial base to take on the additional shipbuilding work associated with achieving and maintaining the Navy's 355-ship force-level goal, see Appendix H.

Employment Impact of Additional Shipbuilding Work

Depending on the number of additional ships per year that might be added to the Navy's shipbuilding effort, building the additional ships that would be needed to achieve and maintain the 355-ship fleet could create thousands of additional manufacturing and other jobs at shipyards, associated supplier firms, and elsewhere in the U.S. economy. A 2015 Maritime Administration (MARAD) report states,

"Considering the indirect and induced impacts, each direct job in the shipbuilding and repairing industry is associated with another 2.6 jobs in other parts of the US economy; each dollar of direct labor income and GDP in the shipbuilding and repairing industry is associated with another $1.74 in labor income and $2.49 in GDP, respectively, in other parts of the US economy."25

A March 2017 press report states, "Based on a 2015 economic impact study, the Shipbuilders Council of America [a trade association for U.S. shipbuilders and associated supplier firms] believes that a 355-ship Navy could add more than 50,000 jobs nationwide."26 The 2015 economic impact study referred to in that quote might be the 2015 MARAD study discussed in the previous paragraph. An estimate of more than 50,000 additional jobs nationwide might be viewed as a higher-end estimate; other estimates might be lower. A June 14, 2017, press report states the following: "The shipbuilding industry will need to add between 18,000 and 25,000 jobs to build to a 350-ship Navy, according to Matthew Paxton, president of the Shipbuilders Council of America, a trade association representing the shipbuilding industrial base. Including indirect jobs like suppliers, the ramp-up may require a boost of 50,000 workers."27

Extending Service Lives of Existing Ships and Reactivating Retired Ships

As one possible option for increasing the size of the Navy beyond or more quickly than what could be accomplished solely through increased rates of construction of new ships, Navy officials stated in 2017 that they explored options for increasing the service lives of certain existing surface ships (particularly DDG-51 class destroyers) and attack submarines (SSNs).

As a second possible option for increasing the size of the Navy—particularly in the nearer term, before increased rates of construction of new ships could produce significant results—Navy officials stated in 2017 that they explored options for reactivating recently retired conventional surface ships, particularly several Oliver Hazard Perry (FFG-7) class frigates. The technical feasibility and potential cost effectiveness of these reactivation options was not clear.28

In its FY2019 budget submission, the Navy is proposing surface life extensions for six Ticonderoga (CG-47) class Aegis cruisers, four mine countermeasures (MCM) ships, and one Los Angeles (SSN-688) class SSN (which the Navy says would be the first of potentially five Los Angeles-class attack submarines to receive a service life extension).29 The Navy is not proposing to extend the surface lives of any DDG-51s or reactivate any FFG-7 class frigates.30

Navy's Five-Year and 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans

FY2019 Five-Year (FY2019-FY2023) Shipbuilding Plan

Table 2 shows the Navy's FY2019 five-year (FY2019-FY2023) shipbuilding plan. The table also shows, for reference purposes, the ships requested for procurement in the Navy's amended FY2018 budget submission, and the ships funded for procurement in the enacted FY2018 DOD appropriations act (Division C of H.R. 1625/P.L. 115-141 of March 23, 2018).31

|

FY18 (req.) |

FY18 (enacted) |

FY19 (req.) |

FY20 |

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY19-FY23 Total |

|

|

Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine |

1 |

1 |

||||||

|

Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarine |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

|

Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class destroyer |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

14 |

|

FFG(X) frigate |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

|||

|

Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

LHA(R) amphibious assault ship |

0 |

|||||||

|

LX(R) amphibious ship |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|||

|

John Lewis (TAO-205) class oiler |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

|

Towing, salvage, and rescue ship (TATS) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

|

TAGOS(X) ocean surveillance ship |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||||

|

Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF) ship |

1 |

0 |

||||||

|

Expeditionary Support Base (ESB) ship |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

||||

|

TOTAL |

9 |

13 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

11 |

13 |

54 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on FY2019 Navy budget submission and P.L. 115-141.

Note: Ships shown are battle force ships—i.e., ships that count against 355-ship goal; FY2018 requested figures shown for reference. In addition to the battle force ships shown in the FY18 (enacted) column, Congress funded the procurement of an additional TAGS oceanographic survey ship. This ship is not a battle force ship.

As shown in the table, the Navy's proposed FY2019 budget requests funding for the procurement of 10 new ships, including two Virginia-class attack submarines, three DDG-51 class Aegis destroyers, one Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), two John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers, one Expeditionary Sea Base ship (ESB), and one TATS towing, salvage, and rescue ship. The total of 10 new ships is

- one more than the nine that the Navy requested in its amended FY2018 budget submission;

- three less than the 13 battle force ships that were funded in the FY2018 DOD appropriations act (Division C of H.R. 1625/P.L. 115-141 of March 23, 2018);32 and

- three more than the seven that were projected for FY2019 in the Navy's FY2018 budget submission. The three added ships include one DDG-51 class destroyer, one TAO-205 class oiler, and one ESB.

As also shown in the table, the Navy's FY2019 five-year (FY2019-FY2023) shipbuilding plan includes 54 new ships, or an average of 10.8 new ships per year. The total of 54 new ships is 12 more (an average of 2.4 more per year) than the 42 that were included in the Navy's FY2018 five-year (FY2018-FY2022) shipbuilding plan, and 11 more (an average of 2.2 more per year) than the 43 that the Navy says were included in the five-year period FY2019-FY2023 under the Navy's FY2018 budget submission. (The FY2023 column was not visible to Congress in the Navy's FY2018 budget submission.) The 11 ships that have been added to the five-year period FY2019-FY2023, the Navy says, are four DDG-51 class destroyers (the third ship in FY2019, FY2021, FY2022, and FY2023), three TAO-205 class oilers (the second ship in FY2019, FY2021, and FY2023), the two ESBs, one TATS (the second ship in FY2020), and one TAGOS ocean surveillance ship (the one in FY2023).

FY2019 30-Year (FY2019-FY2048) Shipbuilding Plan

Table 3 shows the Navy's FY2019-FY2048 30-year shipbuilding plan. In devising a 30-year shipbuilding plan to move the Navy toward its ship force-structure goal, key assumptions and planning factors include but are not limited to ship construction times and service lives, estimated ship procurement costs, projected shipbuilding funding levels, and industrial-base considerations.

As shown in Table 3, the Navy's FY2019 30-year (FY2019-FY2048) shipbuilding plan includes 301 new ships, or an average of about 10 per year. The total of 301 ships is 47 more than the 254 that were included in the Navy's FY2017 30-year (FY2017-FY2046) shipbuilding plan. (The Navy did not submit an FY2018 30-year shipbuilding plan.)

|

FY |

CVNs |

LSCs |

SSCs |

SSNs |

LPSs |

SSBNs |

AWSs |

CLFs |

Supt |

Total |

|

19 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

||||

|

20 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

10 |

|||

|

21 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

|||

|

22 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

|||

|

23 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

||

|

24 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

||

|

25 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

|||

|

26 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

||

|

27 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

||

|

28 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

|

|

29 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

||

|

30 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

11 |

||

|

31 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

13 |

||

|

32 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

|

|

33 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

||

|

34 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

|||

|

35 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

||||

|

36 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

37 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

||||||

|

38 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

7 |

|||||

|

39 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|||||

|

40 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

41 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|||||

|

42 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

43 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|||||

|

44 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

||||

|

45 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|||

|

46 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

||||

|

47 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

||||

|

48 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

||

|

Total |

7 |

76 |

57 |

60 |

5 |

12 |

28 |

27 |

29 |

301 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy's FY2019 30-year (FY2019-FY2048) shipbuilding plan.

Key: FY = Fiscal Year; CVNs = aircraft carriers; LSCs = surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers); SSCs = small surface combatants (i.e., Littoral Combat Ships [LCSs] and frigates [FFG(X)s]); SSNs = attack submarines; LPSs = large payload submarines; SSBNs = ballistic missile submarines; AWSs = amphibious warfare ships; CLFs = combat logistics force (i.e., resupply) ships; Supt = support ships.

Projected Force Levels Under FY2019 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Table 4 shows the Navy's projection of ship force levels for FY2019-FY2048 that would result from implementing the FY2019 30-year (FY2019-FY2048) 30-year shipbuilding plan shown in Table 3.

|

CVNs |

LSCs |

SSCs |

SSNs |

SSGN/LPSs |

SSBNs |

AWSs |

CLFs |

Supt |

Total |

|

|

355-ship goal |

12 |

104 |

52 |

66 |

0 |

12 |

38 |

32 |

39 |

355 |

|

FY19 |

11 |

92 |

31 |

52 |

4 |

14 |

33 |

29 |

33 |

299 |

|

FY20 |

11 |

95 |

34 |

53 |

4 |

14 |

33 |

29 |

35 |

308 |

|

FY21 |

11 |

98 |

37 |

52 |

4 |

14 |

34 |

30 |

34 |

314 |

|

FY22 |

12 |

99 |

35 |

52 |

4 |

14 |

34 |

31 |

37 |

318 |

|

FY23 |

12 |

101 |

39 |

51 |

4 |

14 |

35 |

31 |

39 |

326 |

|

FY24 |

12 |

104 |

32 |

48 |

4 |

14 |

36 |

32 |

39 |

321 |

|

FY25 |

11 |

103 |

32 |

46 |

4 |

14 |

36 |

32 |

40 |

318 |

|

FY26 |

11 |

101 |

33 |

45 |

2 |

14 |

37 |

32 |

40 |

315 |

|

FY27 |

11 |

101 |

35 |

44 |

1 |

13 |

36 |

32 |

41 |

314 |

|

FY28 |

11 |

100 |

37 |

42 |

13 |

37 |

32 |

41 |

313 |

|

|

FY29 |

11 |

99 |

39 |

44 |

12 |

37 |

32 |

41 |

315 |

|

|

FY30 |

11 |

97 |

41 |

45 |

11 |

37 |

31 |

41 |

314 |

|

|

FY31 |

11 |

93 |

43 |

47 |

11 |

37 |

32 |

40 |

314 |

|

|

FY32 |

11 |

92 |

45 |

49 |

11 |

37 |

32 |

41 |

317 |

|

|

FY33 |

11 |

91 |

46 |

50 |

11 |

39 |

32 |

41 |

321 |

|

|

FY34 |

11 |

90 |

48 |

52 |

11 |

37 |

32 |

41 |

322 |

|

|

FY35 |

11 |

88 |

51 |

54 |

11 |

35 |

32 |

42 |

324 |

|

|

FY36 |

11 |

89 |

54 |

56 |

11 |

36 |

32 |

42 |

331 |

|

|

FY37 |

11 |

90 |

55 |

58 |

10 |

36 |

32 |

42 |

334 |

|

|

FY38 |

11 |

93 |

56 |

58 |

10 |

36 |

32 |

40 |

336 |

|

|

FY39 |

11 |

95 |

58 |

59 |

10 |

38 |

32 |

39 |

342 |

|

|

FY40 |

10 |

96 |

59 |

59 |

10 |

37 |

32 |

38 |

341 |

|

|

FY41 |

11 |

96 |

58 |

59 |

11 |

37 |

32 |

38 |

342 |

|

|

FY42 |

10 |

95 |

57 |

61 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

38 |

341 |

|

|

FY43 |

10 |

94 |

54 |

61 |

1 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

38 |

338 |

|

FY44 |

10 |

93 |

52 |

62 |

1 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

38 |

336 |

|

FY45 |

11 |

92 |

51 |

63 |

1 |

12 |

36 |

32 |

38 |

336 |

|

FY46 |

10 |

91 |

50 |

64 |

2 |

12 |

37 |

32 |

38 |

336 |

|

FY47 |

10 |

91 |

51 |

65 |

2 |

12 |

35 |

32 |

38 |

336 |

|

FY48 |

9 |

92 |

49 |

66 |

2 |

12 |

35 |

32 |

38 |

335 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy's FY2019 30-year (FY2019-FY2048) shipbuilding plan.

Note: Figures for support ships include five JHSVs transferred from the Army to the Navy and operated by the Navy primarily for the performance of Army missions.

Key: FY = Fiscal Year; CVNs = aircraft carriers; LSCs = surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers); SSCs = small surface combatants (i.e., frigates, Littoral Combat Ships [LCSs], and mine warfare ships); SSNs = attack submarines; SSGNs/LPSs = cruise missile submarines/large payload submarines; SSBNs = ballistic missile submarines; AWSs = amphibious warfare ships; CLFs = combat logistics force (i.e., resupply) ships; Supt = support ships.

Consistent with CRS and CBO estimates from 2017 shown in Table 1, the Navy projects that the 47 additional ships included in the Navy's FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan would not be enough the achieve a 355-ship fleet during the 30-year period. As shown in Table 4, the Navy projects that if the FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan were implemented, the fleet would peak at 342 ships in FY2039 and FY2041, and then drop to 335 ships by the end of the 30-year period. The Navy projects that under the FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan, a 355-ship fleet would not be attained until the 2050s (and the aircraft carrier force-level goal within the 355-ship goal would not be attained until the 2060s).

Also consistent with CRS and CBO estimates from 2017, the Navy estimates that adding another 20 to 25 ships to the earlier years of the Navy's FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan (and thus procuring a total of 321 to 326 ships in the 30-year plan, or 67 to 72 ships more than the 254 included in the FY2017 30-year plan) could accelerate the attainment of a 355-ship fleet to about 2036 or 2037.33

The Navy's report on its FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan includes notional options for inserting numerous ships into various years of the 30-year shipbuilding program,34 including (CRS estimates) up to 52 or so ships that could be added early enough in the 30-year plan to be in service by about 2037. These 52 or so ships include up to three SSNs, up to six large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers), up to 14 or so small surface combatants, up to 12 or so amphibious ships, up to 12 or so combat logistics force (CLF) ships, and up to five command and support ships.35 Adding 20 to 25 of these 52 or so ships early enough in the 30-year shipbuilding plan could produce a 355-ship fleet by about 2037, although not necessarily one matching the Navy's desired composition for a 355-ship fleet.

Issues for Congress

The overall issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy's proposed FY2019 shipbuilding program and the Navy's longer-term shipbuilding plans. Regarding the Navy's proposed FY2019 shipbuilding program, one issue that Congress may consider is whether the Navy has accurately priced the shipbuilding work it is proposing to do in FY2019. The sections below explore additional issues that can bear on whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy's proposed FY2019 shipbuilding program and the Navy's longer-term shipbuilding plans.

Appropriateness of 355-Ship Goal

One potential oversight issue for Congress concerns the appropriateness of the Navy's 355-ship force-level objective. Potential oversight questions include the following:

- Is the 355-ship goal appropriate and affordable in terms of planned fleet size and composition, given current and projected strategic and budgetary circumstances as discussed in Error! Reference source not found.? Would it provide an appropriate and affordable amount of capacity and capability for responding to Chinese naval modernization and resurgent Russian naval activity, and for meeting requests from U.S. regional combatant commanders for day-to-day forward deployments of Navy ships?

- As noted earlier, the 355-ship goal is the result of a Force Structure Assessment (FSA) conducted by the Navy in 2016, and thus reflects the national military strategy that was in place in 2016 (i.e., the Obama Administration's national military strategy). Is the 355-ship goal appropriate for implementing the Trump Administration's National Security Strategy (NSS), released in December 2017, and National Defense Strategy (NDS), released in January 2018?36 In light of the release of the Trump Administration's NSS and NDS, should the Navy update the 2016 FSA or conduct a new FSA?

At a March 6, 2018, hearing before the Seapower and Projection Forces subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee regarding that subcommittee's portion of the Department of the Navy's proposed FY2019 budget, Representative Gallagher asked the Navy witnesses whether, in light of the Trump Administration's NSS and NDS, the Navy intended to undertake a new FSA. In reply, Vice Admiral William Merz, the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare systems stated: "We intend to do another FSA with the new national defense strategy." Merz added that

We have done multiple studies on the architecture of the Navy and the size of the Navy. Every single one of them says we have to grow. And we have to grow with these fundamental types of ships. So we don't expect much of that to change with the next FSA.

There may be some changes on the margin, there may be another number that we're shooting for, but it's going to be bigger than we are today. So we have to move out and we have to move out aggressively as we—as we go forward....

This will probably be done sometime over the next year as soon as we can. We are eager to get this new FSA completed, but the undeniable fact is we still need to get bigger....37

Navy's Proposed Shipbuilding Plan in Relation to 355-Ship Goal

Another potential oversight question for Congress concerns the relationship of the Navy's proposed shipbuilding plan to the 355-ship force-level goal. Potential oversight questions for Congress include the following:

- Do the Navy's FY2019 five-year and 30-year shipbuilding plans include an appropriate number of ships in relation to the Navy's 355-ship force-level goal? Should policymakers aim to achieve the Navy's 355-ship goal in the 2050s (and the aircraft carrier portion of that goal in the 2060s), as proposed by the Navy, or by a date that is sooner or later than that?

- How does the projected date for attaining the 355-ship fleet relate to the current and projected strategic and budgetary circumstances as discussed in Error! Reference source not found., including the issues of responding to Chinese naval modernization and resurgent Russian naval activity, and providing forces for meeting requests from U.S. regional combatant commanders for day-to-day forward deployments of Navy ships?

- If policymakers decide to achieve the 355-ship goal sooner than the 2050s (and the aircraft carrier portion of that goal sooner than the 2060s), how many ships of what types should be added in which specific years to the Navy's five-year and 30-year shipbuilding plans?

- In a situation of finite defense spending, what impact might adding ships to the shipbuilding plan (and operating and supporting those additional ships once they enter service) have on funding available for other Navy or DOD programs? If adding ships to the shipbuilding plan requires reducing funding for other Navy or DOD programs, what would be the resulting net impact on Navy and DOD capabilities?

Affordability of 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Overview

Another oversight issue for Congress concerns the prospective affordability of the Navy's 30-year shipbuilding plan. This issue has been a matter of oversight focus for several years, and particularly since the enactment in 2011 of the Budget Control Act, or BCA (S. 365/P.L. 112-25 of August 2, 2011). Observers have been particularly concerned about the plan's prospective affordability during the decade or so from the mid-2020s through the mid-2030s, when the plan calls for procuring Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines as well as replacements for large numbers of retiring attack submarines, cruisers, and destroyers.38

As discussed in the CRS report on the Columbia-class program,39 the Navy since 2013 has identified the Columbia-class program as its top program priority, meaning that it is the Navy's intention to fully fund this program, if necessary at the expense of other Navy programs, including other Navy shipbuilding programs. This has led to concerns that in a situation of finite Navy shipbuilding budgets, funding requirements for the Columbia-class program could crowd out funding for procuring other type of Navy ships. These concerns led to the creation by Congress of the National Sea-Based Deterrence Fund (NSBDF), a fund in the DOD budget that is intended in part to encourage policymakers to identify funding for the Columbia-class program from sources across the entire DOD budget rather than from inside the Navy's budget alone.40

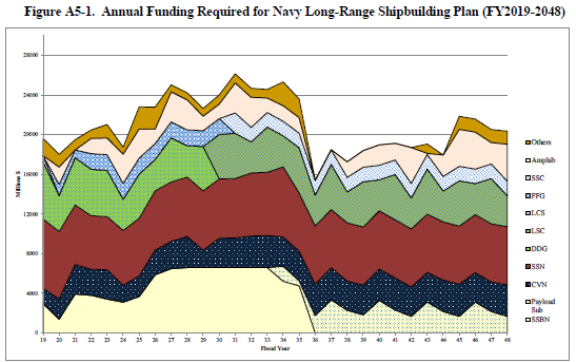

Figure 1 shows the Navy's estimate of the annual amounts of funding that would be needed to implement the Navy's FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan. The figure shows that during the period from the mid-2020s through the mid-2030s, the Navy estimates that implementing the FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan would require roughly $24 billion per year in shipbuilding funds.

As noted earlier, the FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan does not include enough ships to achieve a 355-ship fleet inside the plan's 30-year period—under the 30-year plan, a 355-ship fleet would not be achieved until the 2050s (and the aircraft-carrier portion of the 355-ship goal would not be achieved until the 2060s). As also noted earlier, adding 20 to 25 additional ships to the earlier years of the plan would accelerate the attainment of a 355-ship fleet to 2036 or 2037. Adding those 20 to 25 ships, however, would increase annual funding requirements for the earlier years of the 30-year plan to levels even higher than those shown in Figure 1.

CBO vs. Navy Estimates of Cost of 30-Year Plan

If one or more Navy ship designs turn out to be more expensive to build than the Navy estimates, then the projected funding levels shown in Figure 1 will not be sufficient to procure all the ships shown in the 30-year shipbuilding plan. Ship designs that can be viewed as posing a risk of being more expensive to build than the Navy estimates include Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carriers, Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines, Virginia-class attack submarines equipped with the Virginia Payload Module (VPM), Flight III versions of the DDG-51 destroyer, FFG(X) frigates, LX(R) amphibious ships, and John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers.

The statute that requires the Navy to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan each year (10 U.S.C. 231) also requires CBO to submit its own analysis of the potential cost of the 30-year plan (10 U.S.C. 231[d]). CBO is currently preparing its estimate of the cost of the Navy's FY2019 30-year shipbuilding plan. CBO analyses of past Navy 30-year shipbuilding plans have generally estimated the cost of implementing those plans to be higher than what the Navy estimated.

For example, CBO's estimate of the cost of the Navy's FY2017 30-year (FY2017-FY2046) shipbuilding plan was about 11.1% higher than the Navy's estimated cost for that plan. More specifically, CBO estimated that the cost of the first 10 years of the FY2017 30-year plan would be about 2.0% higher than the Navy's estimate for those 10 years; that the cost of the middle 10 years of the plan would be about 5.9% higher than the Navy's estimate; and that the cost of the final 10 years of the plan would be about 14.6% higher than the Navy's estimate.

The growing divergence between CBO's estimate and the Navy's estimate as one moves from the first 10 years of the plan to the final 10 years of the plan is due in part to a technical difference between CBO and the Navy regarding the treatment of inflation. This difference compounds over time, making it increasingly important as a factor in the difference between CBO's estimates and the Navy's estimates the further one goes into the 30-year period. In other words, other things held equal, this factor tends to push the CBO and Navy estimates further apart as one proceeds from the earlier years of the plan to the later years of the plan.

The Columbia-class program has accounted for some of the difference between the CBO estimate and the Navy estimate, but it has not been the largest source of difference—a future large surface combatant that the Navy shows in the later years of the 30-year plan has accounted for a larger share of the difference between the CBO and Navy estimates, in part because there is a relatively large number of these future large surface combatants in the plan, and because those ships occur in the latter years of the plan, where the effects of the technical difference between CBO and the Navy regarding the treatment of inflation show more strongly.

Legislative Activity for FY2019

CRS Reports Tracking Legislation on Specific Navy Shipbuilding Programs

Detailed coverage of legislative activity on certain Navy shipbuilding programs (including funding levels, legislative provisions, and report language) can be found in the following CRS reports:

- CRS Report R41129, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report R44972, Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report RL33741, Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

- CRS Report R43543, Navy LX(R) Amphibious Ship Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. (This report also covers the issue of funding for the procurement of San Antonio [LPD-17] class amphibious ships.)

- CRS Report R43546, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

Legislative activity on individual Navy shipbuilding programs that are not covered in detail in the above reports is covered below.

Summary of Congressional Action on FY2019 Funding Request

The Navy's proposed FY2019 budget, requests the procurement of 10 new ships:

- 2 Virginia-class attack submarines;

- 3 DDG-51 class Aegis destroyers;

- 1 Littoral Combat Ship (LCS);

- 2 John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers;

- 1 Expeditionary Sea Base ship (ESB); and

- 1 TATS towing, salvage, and rescue ship.

The Navy's proposed FY2018 shipbuilding budget also requests funding for ships that have been procured in prior fiscal years, and ships that are to be procured in future fiscal years, as well as funding for activities other than the building of new Navy ships.

Table 5 summarizes congressional action on the Navy's FY2019 funding request for Navy shipbuilding. The table shows the amounts requested and congressional changes to those requested amounts. A blank cell in a filled-in column showing congressional changes to requested amounts indicates no change from the requested amount.

Table 5. Summary of Congressional Action on FY2019 Funding Request

(Millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth; totals may not add due to rounding)

|

Line number |

Program |

Request |

Congressional changes to requested amounts |

|||||

|

Authorization |

Appropriation |

|||||||

|

HASC |

SASC |

Conf. |

HAC |

SAC |

Conf. |

|||

|

Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN) appropriation account |

||||||||

|

001 |

Ohio replacement AP |

3,005.3 |

||||||

|

002 |

CVN-78 |

1,598.2 |

||||||

|

003 |

CVN-78 AP |

0 |

||||||

|

004 |

Virginia class |

4,373.4 |

||||||

|

005 |

Virginia class AP |

2,796.4 |

||||||

|

006 |

CVN refueling overhaul |

0 |

||||||

|

007 |

CVN refueling overhaul AP |

449.6 |

||||||

|

008 |

DDG-1000 |

271.1 |

||||||

|

009 |

DDG-51 |

5,253.3 |

||||||

|

010 |

DDG-51 AP |

391.9 |

||||||

|

011 |

LCS |

646.2 |

||||||

|

012 |

LPD-17 |

0 |

||||||

|

013 |

ESB |

650.0 |

||||||

|

014 |

LHA(R) |

0 |

||||||

|

015 |

EPF |

0 |

||||||

|

016 |

TAO-205 |

977.1 |

||||||

|

017 |

TAO-205 AP |

75.0 |

||||||

|

018 |

TATS |

80.5 |

||||||

|

019 |

Moored Training Ship (MTS) |

0 |

||||||

|

020 |

LCU 1700 |

41.5 |

||||||

|

021 |

Outfitting |

634.0 |

||||||

|

022 |

Ship-to-Shore Connector |

325.4 |

||||||

|

023 |

Service Craft |

72.1 |

||||||

|

024 |

LCAC SLEP |

23.3 |

||||||

|

025 |

Coast Guard icebreakers |

0 |

||||||

|

026 |

Coast Guard icebreakers AP |

0 |

||||||

|

027 |

YP Craft maint./ROH/SLEP |

0 |

||||||

|

028 |

Completion of PY shipbldg. |

207.1 |

||||||

|

029 |

Adjustment to match CR |

0 |

||||||

|

TOTAL |

21,871.4 |

|||||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy FY2019 budget submission, committee reports, and explanatory statements on the FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act and FY2019 DOD Appropriations Act.

Notes: Millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth. A blank cell indicates no change to requested amount. Totals may not add due to rounding. AP is advance procurement funding; HASC is House Armed Services Committee; SASC is Senate Armed Services Committee; HAC is House Appropriations Committee; SAC is Senate Appropriations Committee; Conf. is conference report.

Legislative Activity for FY2018

Summary of Congressional Action on FY2018 Funding Request

The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget, as amended on May 24, 2017 (with supporting documentation for that amendment provided on June 29, 2017), requested the procurement of nine new ships, including the following:

- 1 Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier,

- 2 Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarines,

- 2 Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class destroyers,

- 2 Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs),

- 1 John Lewis (TAO-205) class oiler, and

- 1 towing, salvage, and rescue ship.

The Navy's proposed FY2018 shipbuilding budget also requested funding for ships that have been procured in prior fiscal years, and ships that are to be procured in future fiscal years, as well as funding for activities other than the building of new Navy ships.

Table 6 summarizes congressional action on the Navy's FY2018 funding request for Navy shipbuilding. The table shows the amounts requested (as amended on May 24, 2017, with supporting documentation for that amendment provided on June 29, 2017) and congressional changes to those requested amounts. A blank cell in a column showing congressional changes to requested amounts indicates no change from the requested amount.

Table 6. Summary of Congressional Action on FY2018 Funding Request

(Millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth; totals may not add due to rounding; request column reflects June 29 Administration budget amendment document increasing by $499.9 million the amount requested in Line 011 [LCS] and the total shown at bottom)

|

Line number |

Program |

Request |

Congressional changes to requested amounts |

|||||

|

Authorization |

Appropriation |

|||||||

|

HASC |

SASC |

Conf. |

HAC |

SAC |

Conf. |

|||

|

Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN) appropriation account |

||||||||

|

001 |

Ohio replacement AP |

842.9 |

+19.0 |

|||||

|

002 |

CVN-78 |

4,441.8 |

-700.0 |

-300.0 |

-11.1 |

-300.0 |

-311.1 |

|

|

003 |

CVN-78 AP |

0 |

+200.0 |

|||||

|

004 |

Virginia class |

3,305.3 |

+943.0 |

+175.0 |

||||

|

005 |

Virginia class AP |

1,920.6 |

+1,173.0 |

+698.0 |

+225.0 |

|||

|

006 |

CVN refueling overhaul |

1,604.9 |

-423.3 |

-35.2 |

-35.2 |

-35.2 |

||

|

007 |

CVN refueling overhaul AP |

75.9 |

||||||

|

008 |

DDG-1000 |

224.0 |

-50.0 |

-50.0 |

-59.0 |

-7.0 |

||

|

009 |

DDG-51 |

3,499.1 |

+1,896.8 |

+1,559.0 |

+1,784.0 |

-170.0 |

-142.0 |

|

|

010 |

DDG-51 AP |

90.3 |

+45.0 |

+300.0 |

+250.0 |

|||

|

011 |

LCS |

1,136.1 |

+533.1 |

-540.0 [subsequently amended in floor debate to +60.0] |

+400.0 |

+430.9 |

+430.9 |

|

|

012 |

LX(R) |

0 |

+1,000.0 |

+1,000.0 |

+1,800.0 |

|||

|

012A |

LX(R) AP |

0 |

+100.0 |

|||||

|

013 |

LPD-17 |

0 |

+1,786.0 |

+1,500.0 [to be used for either LX(R) or LPD-17] |

||||

|

014 |

ESB (formerly AFSB) |

0 |

+635.0 |

+661.0 |

+635.0 |

+635.0 |

+635.0 |

|

|

015 |

LHA-8 |

1,710.9 |

-500.0 |

-15.9 |

||||

|

016 |

LHA-8 AP |

0 |

||||||

|

017 |

EPF (formerly JHSV) |

0 |

+225.0 |

+225.0 |

||||

|

018 |

TAO-205 (formerly TAO[X]) |

466.0 |

-16.6 |

-8.0 |

||||

|

019 |

TAO-205 AP |

75.1 |

||||||

|

020 |

TATS |

76.2 |

-76.2 |

|||||

|

021 |

Moored training ship |

0 |

||||||

|

022 |

Moored training ship AP |

0 |

||||||

|

023 |

LCU 1700 landing craft |

31.9 |

-31.9 |

-31.9 |

||||

|

023A |

TAGS oceanographic ship |

0 |

+150.0 |

+180.0 |

||||

|

024 |

Outfitting |

548.7 |

-38.2 |

-6.1 |

-6.1 |

-59.6 |

-59.6 |

|

|

025 |

Ship to Shore Connector |

212.6 |

+312.0 |

+297.0 |

+312.0 |

+178.0 |

+312.0 |

+312.0 |

|

026 |

Service craft |

24.0 |

+39.0 |

+39.0 |

+39.0 |

+39.0 |

+39.0 |

|

|

027 |

LCAC SLEP |

0 |

||||||

|

028 |

YP craft |

0 |

||||||

|

029 |

Completion of prior-year shipbuilding programs |

117.5 |

||||||

|

031 |

Polar icebreakers (AP) |

0 |

+150.0 |

+150.0 |

||||

|

032 |

Cable ship |

0 |

+250.0 |

+250.0 |

||||

|

TOTAL |

20,403.6 |

+4,866.6 |

+4,350.8 [subsequently amended in floor debate to +4,950.8] |

+5,776.7 |

+1,100.0 |

+1,413.3 |

+3,421,1 |

|

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy FY2018 budget submission, June 29, 2017, Administration budget amendment document, committee reports, and explanatory statements on the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act and FY2018 DOD Appropriations Act.

Notes: Millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth. A blank cell indicates no change to requested amount. Totals may not add due to rounding. AP is advance procurement funding; HASC is House Armed Services Committee; SASC is Senate Armed Services Committee; HAC is House Appropriations Committee; SAC is Senate Appropriations Committee; Conf. is conference report.

The amount shown in the table as requested for the LCS program (line 011) ($1,136.1 million) and the total requested amount shown at the bottom of the table ($20,403.6 million) reflect the Navy's May 24, 2017, announced amendment to its proposed FY2018 budget and a June 29, 2017, Administration budget amendment document detailing the resulting changes to its proposed FY2018 budget. The changes increase the requested amount in line 011 and the requested total shown at the bottom by $499.9 million.

The HASC, SASC, and HAC reports on the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act and FY2018 DOD appropriations Act use the Navy's pre-amendment (i.e., May 23, 2017) budget submission, which requests one LCS for $636.1 million. In the table above, however, the HASC-, SASC-, and HAC-recommended changes to line 011 are calculated against the amended budget request for two LCSs at a combined cost of $1,136.1 million. For example, the HAC report recommends procuring three LCSs at a combined cost of $1,567.0 million. The HAC report shows this as an increase of $930.8 million over the originally requested figure of $636.1 million. The table above, however, shows it as an increase of $430.9 million over the amended requested figure of $1.136.1 million.

HASC funding changes are the combined result of figures shown on pages 377-378 (procurement) and 419-420 (procurement for overseas contingency operations for base requirements) of H.Rept. 115-200 of July 6, 2017, on H.R. 2810.

The funding line for ESB (formerly AFSB)—line 014—is shown in the SASC report (S.Rept. 115-125 of July 10, 2017) as line 030.

HAC funding changes do not include any additional funding for shipbuilding programs that may result from $12,622.9 million (i.e., about $12.6 billion) in DOD procurement funding included in the National Defense Restoration Fund. Line-item allocations for this $12.6 billion are to be determined after the Administration submits a new national defense strategy. (See pages 4-5 and 208 of H.Rept. 115-219 of July 13, 2017, on H.R. 3219.)

Things to note about the table including the following:

- The amount shown in the table as requested for the LCS program (line 011) ($1,136.1 million) and the total requested amount shown at the bottom of the table ($20,403.6 million) reflect the Navy's May 24, 2017, announced amendment to its proposed FY2018 budget and a June 29, 2017, Administration budget amendment document detailing the resulting changes to its proposed FY2018 budget. The changes increase the requested amount in line 011 and the requested total shown at the bottom by $499.9 million.41

- The HASC, SASC, and HAC reports on the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act and FY2018 DOD appropriations Act use the Navy's pre-amendment (i.e., May 23, 2017) budget submission, which requests one LCS for $636.1 million. In Table 6 below, however, the HASC-, SASC-, and HAC-recommended changes to line 011 are calculated against the amended budget request for two LCSs at a combined cost of $1,136.1 million. For example, the HAC report recommends procuring three LCSs at a combined cost of $1,567.0 million. The HAC report shows this as an increase of $930.8 million over the originally requested figure of $636.1 million. Table 6 below, however, shows it as an increase of $430.9 million over the amended requested figure of $1.136.1 million.

- HASC funding changes are the combined result of figures shown on pages 377-378 (procurement) and 419-420 (procurement for overseas contingency operations for base requirements) of H.Rept. 115-200 of July 6, 2017, on H.R. 2810.

- The funding line for ESB (formerly AFSB)—line 014—is shown in the SASC report (S.Rept. 115-125 of July 10, 2017) as line 030.

- HAC funding figures do not include any additional funding for shipbuilding programs that may result from $12,622.9 million (i.e., about $12.6 billion) in DOD procurement funding included in the National Defense Restoration Fund. Line-item allocations for this $12.6-billion fund are to be determined after the Administration submits a new national defense strategy. (See pages 4-5 and 208 of H.Rept. 115-219 of July 13, 2017, on H.R. 3219.)

- On September 18, 2017, as part of its consideration of H.R. 2810, the Senate by unanimous consent agreed to S.Amdt. 1086, increasing LCS procurement funding (line 011) by $600 million, offset by a $600 million increase in a DOD budget line item relating to fuel savings.

FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/S. 1519)

House

The House Armed Services Committee, in its report (H.Rept. 115-200 of July 6, 2017) on H.R. 2810, recommends the funding levels for shipbuilding programs shown in the HASC column of Table 6. These recommended funding levels are the combined result of figures shown on pages 377-378 (procurement) and 419-420 (procurement for overseas contingency operations for base requirements) of H.Rept. 115-200. Among other things, H.Rept. 115-200 recommends funding for the following:

- 1 additional DDG-51 class destroyer;

- 1 additional LCS (for a total of 3 LCSs, compared to 2 LCSs in the Navy's amended budget request);

- 1 additional LPD-17 class amphibious ship;

- 1 additional Expeditionary Support Base (ESB) ship; and

- 5 additional Ship-to-Shore Connector (SSC) landing craft.

Section 121(b) of H.R. 2810 as reported states the following:

SEC. 121. Aircraft carriers

...

(b) Increase in number of operational aircraft carriers.—

(1) INCREASE.—Section 5062(b) of title 10, United States Code, is amended by striking "11 operational aircraft carriers" and inserting "12 operational aircraft carriers".

(2) EFFECTIVE DATE.—The amendment made by paragraph (1) shall take effect on September 30, 2023.

Section 127(a) of H.R. 2810 as reported states the following:

SEC. 127. Extensions of authorities relating to construction of certain vessels.

(a) Extension of authority to use incremental funding for LHA Replacement.—Section 122(a) of the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2017 (114–328; 130 Stat. 2030) is amended by striking "for fiscal years 2017 and 2018" and inserting "for fiscal years 2017, 2018, and 2019".

Section 1015 of H.R. 2810 as reported states the following:

SEC. 1015. Availability of funds for retirement or inactivation of Ticonderoga-class cruisers or dock landing ships.

None of the funds authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise made available for the Department of Defense for fiscal year 2018 may be obligated or expended—

(1) to retire, prepare to retire, or inactivate a cruiser or dock landing ship; or

(2) to place more than six cruisers and one dock landing ship in the modernization program under section 1026(a)(2) of the Carl Levin and Howard P. "Buck" McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 (Public Law 113–291; 128 Stat. 3490).

Section 1016 of H.R. 2810 as report states the following:

SEC. 1016. Policy of the United States on minimum number of battle force ships.

It shall be the policy of the United States to have available, as soon as practicable, not fewer than 355 battle force ships, with funding subject to the annual authorization of appropriation and the annual appropriation of funds.

Section 1035 of H.R. 2810 as reported states the following:

SEC. 1035. Prohibition on use of funds for retirement of legacy maritime mine countermeasures platforms.

(a) Prohibition.—Except as provided in subsection (b), the Secretary of the Navy may not obligate or expend funds to—

(1) retire, prepare to retire, transfer, or place in storage any AVENGER-class mine countermeasures ship or associated equipment;

(2) retire, prepare to retire, transfer, or place in storage any SEA DRAGON (MH–53) helicopter or associated equipment;

(3) make any reductions to manning levels with respect to any AVENGER-class mine countermeasures ship; or

(4) make any reductions to manning levels with respect to any SEA DRAGON (MH–53) helicopter squadron or detachment.

(b) Waiver.—The Secretary of the Navy may waive the prohibition under subsection (a) if the Secretary certifies to the congressional defense committees that the Secretary has—

(1) identified a replacement capability and the necessary quantity of such systems to meet all combatant commander mine countermeasures operational requirements that are currently being met by any AVENGER-class ship or SEA DRAGON helicopter to be retired, transferred, or placed in storage;

(2) achieved initial operational capability of all systems described in paragraph (1); and

(3) deployed a sufficient quantity of systems described in paragraph (1) that have achieved initial operational capability to continue to meet or exceed all combatant commander mine countermeasures operational requirements currently being met by the AVENGER-class ships and SEA DRAGON helicopters to be retired, transferred, or placed in storage.

Section 1257 of H.R. 2810 as reported states the following:

SEC. 1257. Sense of Congress on enhancing maritime capabilities.

Congress notes the 2016 Force Structure Assessment (FSA) that increased the requirement for fast attack submarine (SSN) from 48 to 66 and supports an acquisition plan that enhances maritime capabilities that address this requirement.

Section 3116 of H.R. 2810 as reported states the following:

SEC. 3116. Research and development of advanced naval reactor fuel based on low-enriched uranium.

(a) Prohibition on availability of funds for fiscal year 2018.—

(1) RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT.—Except as provided by paragraph (2), none of the funds authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise made available for fiscal year 2018 for the Department of Energy or the Department of Defense may be obligated or expended to plan or carry out research and development of an advanced naval nuclear fuel system based on low-enriched uranium.

(2) EXCEPTION.—Of the funds authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise made available for fiscal year 2018 for defense nuclear nonproliferation, as specified in the funding table in division D—

(A) $5,000,000 shall be made available to the Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors of the National Nuclear Security Administration for low-enriched uranium activities (including downblending of high-enriched uranium fuel into low-enriched uranium fuel, research and development using low-enriched uranium fuel, or the modification or procurement of equipment and infrastructure related to such activities) to develop an advanced naval nuclear fuel system based on low-enriched uranium; and

(B) if the Secretary of Energy and the Secretary of the Navy determine under section 3118(c)(1) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 1196) that such low-enriched uranium activities and research and development should continue, an additional $30,000,000 may be made available to the Deputy Administrator for such purpose.

(b) Prohibition on availability of funds regarding certain accounts and purposes.—

(1) RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT AND PROCUREMENT.—Chapter 633 of title 10, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following new section:

"§ 7319. Requirements for availability of funds relating to advanced naval nuclear fuel systems based on low-enriched uranium

"(a) Authorization.—Low-enriched uranium activities may only be carried out using funds authorized to be appropriated or otherwise made available for the Department of Energy for atomic energy defense activities for defense nuclear nonproliferation.

"(b) Prohibition regarding certain accounts.— (1) None of the funds described in paragraph (2) may be obligated or expended to carry out low-enriched uranium activities.

"(2) The funds described in this paragraph are funds authorized to be appropriated or otherwise made available for any fiscal year for any of the following accounts:

"(A) Shipbuilding and conversion, Navy, or any other account of the Department of Defense.

"(B) Any account within the atomic energy defense activities of the Department of Energy other than defense nuclear nonproliferation, as specified in subsection (a).

"(3) The prohibition in paragraph (1) may not be superseded except by a provision of law that specifically supersedes, repeals, or modifies this section. A provision of law, including a table incorporated into an Act, that appropriates funds described in paragraph (2) for low-enriched uranium activities may not be treated as specifically superseding this section unless such provision specifically cites to this section.

"(c) Low-enriched uranium activities defined.—In this section, the term 'low-enriched uranium activities' means the following:

"(1) Planning or carrying out research and development of an advanced naval nuclear fuel system based on low-enriched uranium.

"(2) Procuring ships that use low-enriched uranium in naval nuclear propulsion reactors.".

(2) CLERICAL AMENDMENT.—The table of sections at the beginning of such chapter is amended by adding at the end the following new item:

"7319. Requirements for availability of funds relating to advanced naval nuclear fuel systems based on low-enriched uranium".

(c) Reports.—

(1) SSN(X) SUBMARINE.—Not later than 180 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the Navy and the Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors shall jointly submit to the Committees on Armed Services of the House of Representatives and the Senate a report on the cost and timeline required to assess the feasibility, costs, and requirements for a design of the Virginia-class replacement nuclear attack submarine that would allow for the use of a low-enriched uranium fueled reactor, if technically feasible, without changing the diameter of the submarine.

(2) RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT.—Not later than 60 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors shall submit to the Committees on Armed Services of the House of Representatives and the Senate a report on—

(A) the planned research and development activities on low-enriched uranium and highly enriched uranium fuel that could apply to the development of a low-enriched uranium fuel or an advanced highly enriched uranium fuel; and

(B) with respect to such activities for each such fuel—

(i) the costs associated with such activities; and

(ii) a detailed proposal for funding such activities.

H.Rept. 115-200 states the following:

Implications of a 355-ship Navy on Naval and Marine Corps Aviation force structure requirements

The committee notes that the Navy's most recent Force Structure Assessment indicates a need to increase Navy force structure to 355 ships, which includes a 12th aircraft carrier. The committee also notes that this greater fleet size may in turn impact Navy and Marine Corps Aviation force structure requirements.