Freight System Components

The U.S. freight system is a complex network including four principal modes of transportation:

- The National Truck Network comprises 209,000 miles of highways that can accommodate large trucks, including the 47,000-mile Interstate Highway System.

- Railroads, largely in private ownership, carry freight on 140,000 miles of track.

- Barge and ship lines utilize 12,000 miles of shallow-draft inland waterways and about 3,500 inland and coastal port terminal facilities.

- Air carriers provide cargo service to more than 5,000 public use airports, including more than 100 airports that handle all-cargo aircraft.

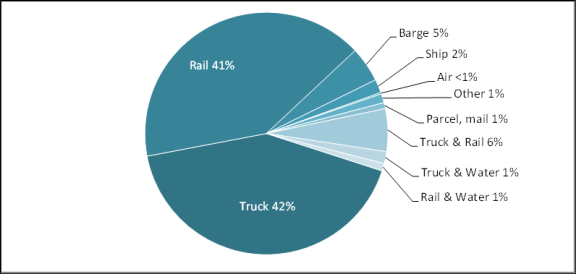

About two-fifths of freight within the United States, measured in ton-miles, moves by truck, and another two-fifths moves by rail (Figure 1). About 9% moves by multiple modes. Trucking accounts for almost three-quarters of freight movement when measured in either tons or cargo value. Air freight has an exceptionally high value to weight ratio, and 30% of the nation's exports (by value) move this way. Waterborne freight accounts for 7% of domestic tonnage, but almost 20% of import and export tonnage.1

The Federal Role in Planning

The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) has described freight transportation planning as "convoluted" and "de-centralized."2 This has both advantages and disadvantages. An advantage of decentralized planning, from the standpoint of a local government, is that it can advance local capacity building even if freight capacity is available in other localities. One disadvantage frequently cited by shippers is that freight projects do poorly in the public planning processes of state departments of transportation and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), the government entities that are largely responsible for deciding which road projects get built, because the general public values improvements to passenger travel more highly than improvement of freight movements. Planners in the public sector also can be uncomfortable advocating for projects with direct benefits to the private sector.3 Additionally, as the National Freight Advisory Committee claimed in 2014, freight projects may lose out "because their benefits spread nationally or regionally, beyond the boundaries of the funding entity."4

One of the freight policy goals stated in the 2015 surface transportation law, the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act; P.L. 114-94), is "to improve the flexibility of States to support multi-State corridor planning and the creation of multi-State organizations to increase the ability of States to address multimodal freight connectivity" (§8001). Addressing major freight bottlenecks with federal grants can be difficult politically because it entails allocating large sums to relatively few, narrowly defined geographic areas. Also, federal funding decisions in freight transportation have the potential to create winners and losers. For example, a federal expenditure to deepen one harbor but not another could shift the flow of freight and the location of business investments and jobs.

The important role of multi-modal transportation in freight movement creates a particular challenge in setting spending priorities. Federal transportation programs are typically focused on a single mode; surface transportation, aviation, and maritime programs are authorized in separate laws and overseen by separate agencies within and outside DOT, complicating assistance to multi-modal projects, which are common in freight infrastructure. Recent changes in law have sought to reduce this artificial separation of transportation modes by allowing limited funds raised by federal taxes paid by highway users to be spent on projects that benefit entities such as railroads and water carriers, but this raises questions about the equity of cross-subsidization.

Under current policy, reiterated in the FAST Act, state departments of transportation are encouraged to establish freight advisory committees including industry representatives, and to develop state freight plans that include lists of priority projects. To develop better plans, many state and city transportation planners seek more robust information on freight shipments through their districts. In the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21; P.L. 112-141, §1115(h)(1)(C)), and again in the FAST Act (§8001), Congress requested DOT to "consider any improvements to existing freight flow data collection efforts that could reduce identified freight data gaps and deficiencies."

Infrastructure Funding and Support

Highway Freight Funding

Trucks pay a federal diesel fuel tax of 24.3 cents per gallon, as well as taxes on trucks and tires. The proceeds of these taxes, along with money from the U.S. Treasury general fund, are deposited into the Highway Trust Fund, which makes approximately $45 billion available annually for the Federal-Aid Highway Program. In the FAST Act, Congress set aside roughly 5% of this amount to focus more narrowly on freight movements. This represents a significant change from previous law, which did not dedicate federal surface transportation funds to freight.5

National Highway Freight Network

The FAST Act requires DOT, in coordination with states and MPOs, to identify roadways that are heavily used by trucks. These roadways include a "Primary Highway Freight System" (PHFS) designated by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), "critical rural freight corridors" designated by state departments of transportation, and "critical urban freight corridors" designated by either states or MPOs (depending on the population size of an urban area). The PHFS currently comprises 41,518 miles of highway that FHWA has identified as critical to freight movement, but PHFS mileage could increase by 3% every five years, based on changes in truck movements.6

Congress directed that $1.2 billion per year of federal funds apportioned to the states by formula be used for projects on this designated freight network.7 It also specified that up to 10% of a state's apportionment may be directed toward projects "within the boundaries of public or private freight rail or water facilities (including ports); and that provide surface transportation infrastructure necessary to facilitate direct intermodal interchange, transfer, and access into or out of the facility."

Nationally Significant Freight and Highway Project Grant Program

In addition, the FAST Act created a competitive grant program for freight projects of about $900 million per year.8 Public entities, including states and groups of states, MPOs, local governments, port authorities, and tribal governments, may apply for these funds to build highway projects, railway-highway grade crossing projects, connections to ports and intermodal freight facilities, and elements of private freight rail projects that provide public benefits. Although these competitive grants may provide no more than 60% of a project's cost, other federal assistance can be used to provide up to a total of 80%.

The competitive grant program is designed primarily for relatively high-cost projects; each grant awarded must be at least $25 million and the project must have eligible costs amounting to at least $100 million or a significant share of a state's highway funding apportionment the previous fiscal year (at least 30% in the case of a project within a single state). However, 10% of grant funds are reserved for smaller projects, with a minimum grant size of $5 million. The Trump Administration has named this program Infrastructure for Rebuilding America (INFRA) grants.9

Border Infrastructure

Congress also specified that states bordering Canada or Mexico may use up to 5% of their Surface Transportation Block Grant Program funds (defined in §1109 of the FAST Act) for highway infrastructure supporting cross-border movements.10

Railroad Improvements

Railroads rely primarily on their own revenues and borrowings to maintain and improve their facilities. The large Class I railroads spend about $10 billion annually on their roadways and structures.11

Congress removed most federal oversight of railroad freight rates in the 1980s. While freight railroads publish rates that are available to any shipper, most railroad freight moves at rates agreed in confidential contracts between railroads and shippers. In those contract negotiations, railroads seek to charge rates that will cover the cost of maintaining and improving their infrastructure, pay for operations, and provide a profit.

Surface Transportation Board Reform

The Surface Transportation Board (STB), an independent agency housed in DOT, judges the reasonableness of rail rates in markets where the railroad is determined to have "market dominance," generally where a shipper is served by only one railroad and cannot ship economically by truck or water. The STB is tasked with balancing the need for railroad revenues adequate for reinvestment with the need for competitive rail rates and service. When Congress reauthorized the STB in 2015, it expanded the board from three to five commissioners and modified procedures with the intent of making the rail rate review process faster and less costly.12 Some STB practices may be outdated, according to a study by the Transportation Research Board requested by Congress. The study found that a number of STB practices and procedures date back to the period before rate deregulation in 1980.13

Rail Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing

Congress has sought to encourage investment in rail infrastructure through the Rail Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) program, which provides loans and credit assistance to sponsors of public and private rail projects. Eligible projects include acquiring, improving, or rehabilitating rail equipment, refinancing existing debt for these purposes, or developing new rail facilities. Loans can be used to finance 100% of project costs with repayment up to 25 years. To date, almost all the recipients of freight-related loans have been shortline railroads, which typically own small pieces of track to serve local shippers, or regional railroads, which may own longer track segments, but most of their freight is transferred to or from the large "Class I" railroads.14

Navigation Infrastructure

While Congress has largely left it to the states to determine which highway infrastructure projects will receive federal funding, it is closely involved in determining which navigation infrastructure projects will be funded. Project funding is controlled through authorizations and appropriations to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Civil Works program. The Army Corps builds, maintains, and operates locks, dredges channels, and builds and maintains breakwaters to support both inland and deepwater navigation. Federal funding is focused on the "waterside" portion of marine infrastructure; "landside" infrastructure—that is, terminal infrastructure on port grounds—is primarily funded by private terminal operators and publicly owned port authorities, and ultimately paid for by charges on carriers and shippers.

Inland Waterway Trust Fund

The Inland Waterway Trust Fund, funded via a tax of 29 cents per gallon on barge fuel, is used to fund half the cost of new construction/major rehabilitation on inland rivers. General Treasury funds provide the other half, and fund 100% of inland waterway operations and maintenance. A handful of waterway segments generate negligible traffic but consume about a third of the operating and maintenance budget.15 A study by an expert panel assembled by the Transportation Research Board suggests dedicating revenues from user fees to operation and maintenance instead of only capital expenditures in order to protect the value of existing waterway assets.16 Inland waterway shippers are concerned that the level of user fees not divert cargo from the waterways.

Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund

The Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF), funded via a tax of $1.25 per $1,000 of cargo moving through coastal and Great Lakes ports, provides half of federal expenditures on harbor maintenance, such as dredging to maintain a harbor's depth, with the general fund covering the other half. The general fund also pays 100% of the federal share of harbor improvements, such as deepening a harbor. Projects to deepen harbors with federal funds require specific congressional approval and, in many cases, a state or local financial contribution. About a third of HMTF expenditures is used for cargo ports, with the remainder spent to maintain recreational and fishing harbors or on other government activities.17

Enlargement of the Panama Canal has spurred interest in deepening ports on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts to accommodate larger ships. Since ship operators pay none of the cost of dredging, they do not consider this cost when calculating the costs and benefits of larger ships. Yet only a handful of "load center" ports can realistically expect to see larger containerships or tankers.18 Under the present financing method and planning process, each port deepening project is initiated at the local level and evaluated in isolation from other port projects, potentially leading to excess port capacity in a region or nationally. However, this approach allows communities to determine their harbor's development.

Shipyard Assistance

An important law influencing U.S. freight patterns is the requirement that any vessel transporting cargo between U.S. points be built in the United States. This requirement originates from the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (§27), and is commonly referred to as the Jones Act.19 The act's supporters contend it helps preserve U.S. shipbuilding capability that is necessary for national security reasons. Shippers claim this requirement severely limits the availability of ships and raises the cost of coastal shipping. Currently, two active U.S. shipyards build oceangoing cargo ships, but can deliver only two to three ships per year. The cost of a U.S.-built ship is generally three to five times the cost of a foreign-built ship. For example, a U.S.-built coastal oil tanker might cost $135 million, while a foreign-built tanker of similar size might cost $35 million.20

Loan Guarantees and Grants

In addition to banning foreign shipbuilding in domestic waterborne commerce, the federal government supports domestic shipbuilding with loan guarantees and grants. The Title XI program (46 U.S.C. §53702) provides loan guarantees to vessel operators for the purpose of financing the construction of vessels in U.S. shipyards. Loan guarantees cannot exceed 87.5% of the project's cost, and the repayment period cannot exceed 25 years from vessel delivery. A 2015 DOT Inspector General audit found $644 million in default under this program.21

The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2009 (P.L. 110-417) established the Assistance to Small Shipyards Grant Program. U.S. shipyards with less than 1,200 production employees are eligible to receive matching grants from DOT's Maritime Administration (MARAD) to finance capital improvements and equipment purchases. About $5 million to $15 million a year has typically been made available for this program annually, except that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided $100 million.

Capital Construction Fund

The Capital Construction Fund (CCF; 46 U.S.C. §53501) enables U.S. vessel owners to defer federal taxes by depositing their income in a CCF. Amounts held in a CCF may be used only to finance the construction, reconstruction, or acquisition of a vessel built or rebuilt in a U.S. shipyard. The fund is established by the ship owner subject to MARAD regulations and reporting requirements.22 About 180 domestic ship owners have established a CCF.

Duty on Foreign Ship Repairs

Under the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, U.S. vessel operators are liable for a 50% duty on maintenance and repairs performed on their vessels at overseas shipyards. The duty is intended to encourage U.S.-flag operators to perform repairs in domestic shipyards.

Freight Performance Issues

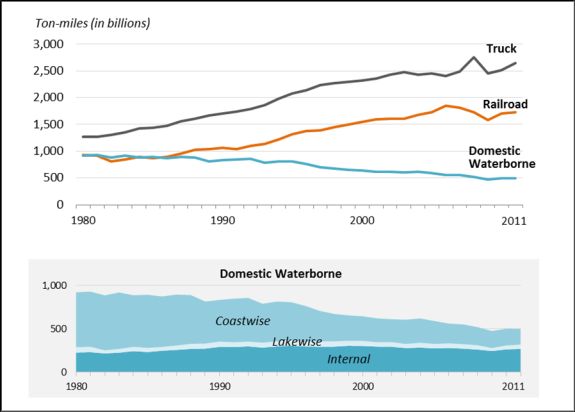

As Figure 2 illustrates, truck ton-miles over the last three decades have more than doubled, and railroad ton-miles have nearly doubled. Domestic waterborne ton-miles, in contrast, are approximately half of what they were in 1980. As the figure indicates, the decline is mostly in coastal shipping; shipping on the Great Lakes and the inland rivers has been comparatively stable. At least a third of the decline in coastal shipping can be explained by a decrease in the amount of Alaska crude oil shipped to Washington and California refineries.23 However, excluding Alaska oil, coastwise shipping tonnage today is about 45% less than it was in the mid-1970s, before shipments of Alaska oil began.

|

|

Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics, National Transportation Statistics, Table 1-50; tabulated July 2014. Notes: Lakewise is shipping on the Great Lakes. Internal is shipping on inland rivers. |

The decline of waterborne shipping shown in Figure 2 pertains only to domestic commerce. Waterborne shipping has maintained its market share relative to truck and rail in moving freight to and from Canada and Mexico. The volume of U.S. overseas commerce carried by ship has increased 60% since 1980. Very little U.S. international maritime trade is carried out by U.S.-built or U.S.-crewed vessels.24

Congestion has been a prominent policy concern for truckers and truck shippers. Port congestion has been an issue for some international maritime shippers and periodically for rail shippers; congestion on some rail routes was severe in 2014, but has since abated as rail freight volume declined.

Truck Congestion

Highway congestion frustrates trucking's ability to provide precise and reliable scheduling. Unreliability is costly because it requires manufacturers and retailers to carry buffer stock, reducing an efficient "just-in-time" (JIT) logistics strategy to a "just-in-case" strategy.25 Highway congestion is particularly pronounced in major urban areas that contain important freight hubs such as ports, airports, border crossings, and rail yards. As identified by DOT, the 25 most congested segments for trucks are generally urban Interstate Highway interchanges.26 Five of the 25 most congested segments are in Houston. A trucking industry study estimates that 89% of the total costs of congestion for trucks is concentrated on 12% of Interstate Highway mileage.27 One difficulty in addressing infrastructure pinchpoints is that much of the benefit may flow to distributors and manufacturers located outside the state where the congestion occurs.

The expense and difficulty of widening highways in urban areas has prompted discussions on a host of alternative measures for mitigating congestion. One alternative discussed is diversion of truck freight to rail and water modes, but there are economic and policy obstacles to diverting truck freight to these modes.

Rail Pinchpoints

In corridors with sufficient cargo volume, railroads are cost-competitive with trucks in moving trailers and containers for distances exceeding 500 miles. Freight rail congestion has been episodic, and in 2014 was largely attributable to poor weather, demand surges, and bottlenecks in Chicago, the nation's largest railroad hub. In 2014, a boom in movements of crude oil from North Dakota, combined with a bumper harvest and a residual backlog of shipments stemming from the severe winter of 2013-2014, caused delays in rail service in the Upper Midwest that reverberated across the nation.28 As a result of this experience, the STB requires railroads to report weekly on their performance nationally, and in Chicago particularly, so that service levels can be monitored.29

Railroads generally have room to increase capacity and reduce congestion by adding parallel tracks over much of their networks in rural areas. However, they face constraints in expanding their terminals in urban areas. The increasing popularity of intercity and commuter passenger rail services has placed additional demands on rail infrastructure. Some railroad operators have received federal, state, or local government support for infrastructure improvements that also benefit freight service in return for hosting more passenger trains.

Coastal Shipping's Decline

Ships are a transportation mode capable of providing lower-cost alternatives to overland transport. Their inherent economy stems from being able to carry more cargo per trip, not incurring the cost of maintaining rights-of-way,30 and having fewer limitations on cargo dimensions and weight.

Despite these cost advantages, coastal shipping is typically not price-competitive with overland modes in the United States. U.S. coastal shipping provides almost no competition to railroads and trucks. Most coastal shipping services link the U.S. mainland with Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico on routes where land modes are not an option, or deliver fuel to Florida and New England on routes where pipeline service is not available.31 The requirement that coastal shipping be conducted in vessels that meet Jones Act requirements, including U.S. construction, at least 75% ownership by U.S. citizens, and crews comprising mainly U.S. citizens, may be waived if deemed "necessary in the interest of national defense." Such waivers were granted temporarily after hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria in September 2017.

Seagoing Barges Favored over Ships

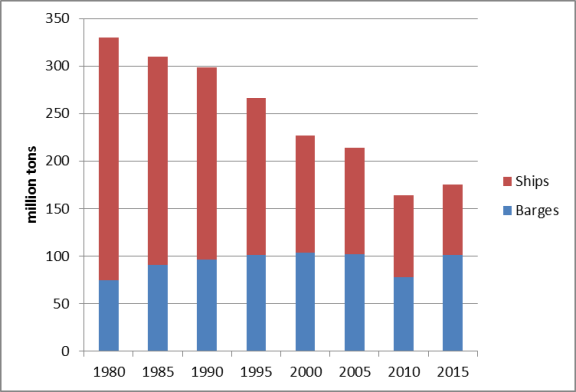

Seagoing barges are more prevalent than ships in U.S. coastal service because they cost less to build and, due to Coast Guard regulations governing manning of vessels, require one-third to one-half the number of crew. Due to such cost differences, some domestic routes may utilize barges where otherwise they would be served by ships. In the 1980s, ships carried about 70% of domestic coastwise tonnage and barges carried 30%, but since then there has been a steady decline in coastwise ship tonnage while coastwise barge tonnage has remained relatively stable (Figure 3).

|

|

Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Waterborne Commerce Statistics, National Summaries, Table 1-12. |

Operating at slower speeds than ships, barges can operate economically only over shorter distances. As a result, the average haul in coastwise service has declined from around 2,000 miles in the 1980s to less than 1,000 miles today. Barges are also more limited than ships by sea conditions.

While coastwise services today are less efficient than in the 1980s, carrying less cargo tonnage but using more vessels and trips to do so, their modal competitors have been improving efficiency. Railroads carry 40% more tons per train today than they did in the 1980s by using larger railcars and longer trains, and pipelines carry more petroleum with less mileage by increasing pipe diameters.

High Operating Costs

The domestic ship fleet is significantly older, on average, than the world fleet, because high construction costs discourage replacement of older U.S.-built vessels. Older ships are more costly to operate because they are less fuel-efficient, have less automation and therefore require more crew, and have higher maintenance costs. A statutory requirement affecting crew size dates back to 1915, when vessels were powered by steam boilers and turbines that required round-the-clock attention.32 This law requires at least three crew shifts per 24-hour period (i.e., three mariners per position), and prohibits mariners from working in both the deck and engine departments, which discourages the adoption of new technology, according to one study.33

Marine Highways Initiative

In 2007, Congress authorized an initiative called "Marine Highways" that seeks to divert truck or rail freight from congested corridors to water routes by providing federal grants for terminal equipment and vessel upgrades.34 Initially, this program was limited to only those projects that intended to divert freight from a congested parallel highway or railway, but Congress expanded it in 2012 to include routes between all U.S. ports (including ports with no contiguous landside connection).35

Marine highway operations involving transfer of containers from ships to barges or from large oceangoing ships to smaller ones are common abroad, but they face a number of financial obstacles in the United States. These include the need to use U.S.-built vessels for the domestic leg, relatively high crewing costs, unattractive port labor arrangements, and collection of the 0.125% cargo tax to fund the HMTF twice on transshipped cargo. A study of the feasibility of a marine highway along the East Coast found it was uneconomical unless the two largest cost components, labor cargo-handling costs and vessel capital costs, could be reduced.36 On the West Coast, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which represents dockworkers, has objected to the Marine Highways initiative, contending that it will be used to drive down wages and encourage operations at non-union ports.37

Container Port Efficiency

A labor-management dispute that slowed container throughput at West Coast ports in late 2014 drew congressional attention to the efficiency of U.S. ports. At a congressional hearing examining the labor-management dispute, one railroad official testified that "Improving efficiency will be as important as infrastructure expansion, and certainly less costly, in achieving the throughput that the nation requires from its ports. U.S. port efficiency is among the lowest of world trading partners."38

In the FAST Act (§6018), Congress directed DOT to establish a port performance statistics program that would report annually on capacity and throughput at the nation's leading ports. Shippers of containerized cargo suggest that port performance be measured by the amount of time it takes to process conveyances, including the average time needed to unload and load a vessel (adjusted for its size), the average time trucks wait outside terminal gates, and the average time required to pick up or drop off a container once a truck has entered the port.39 Such metrics may be more useful for monitoring performance at individual facilities over time rather than comparing ports, as port characteristics vary considerably. Port and terminal operators point out that some metrics widely used to compare ports internationally, such as the average number of container crane movements per hour, may be affected by factors beyond their control, such as the average size of vessels serving a port. DOT's first annual report, published in 2016, was a preliminary report that did not provide data that would be useful to shippers in evaluating port performance.40

Containerships calling at the largest U.S. ports are now carrying, on average, twice as many containers as they did a decade ago.41 This has increased pressure for further automation and more rapid distribution of containers in and out of ports. A handful of terminals have been redesigned around driverless cranes for sorting containers within the terminal. The reduction in workforce and change in the required skill set from equipment operators to equipment mechanics and software engineers are a concern of longshore unions.

Congestion at truck gates has been a persistent problem at some container ports. Unlike truck distribution centers and rail terminals that typically operate 24/7, port terminal gates typically operate 9-5 on weekdays only (and close during lunch breaks), charging significantly higher rates if off-hours work is requested. In many cases, import containers awaiting truck pickup are stacked in the terminal yard in random sequence, because the terminal operator does not know when a particular container will be collected. This situation requires inefficient reshuffling of container stacks. Ports are seeking to move to more organized truck pickup, but the prevalence of independent truckers, typically paid by the trip to the port, frustrates coordinated information processing and contributes to long truck waiting times. The Federal Maritime Commission, which regulates international ocean shipping, held a series of forums at ports around the country in 2014 examining the causes and proposed solutions to truck gate congestion.42 The agency recommends that ports develop a nationwide information portal system that would help truckers and shippers better plan their container movements through ports.43