The United States has initiated renegotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico. The Administration's agriculture-related objectives in the renegotiation include a contentious proposal to establish trade remedies for perishable and seasonal products.1 The proposal would establish separate domestic provisions for seasonal products such as fruits and vegetables in anti-dumping and countervailing duties (AD/CVD) proceedings, making it easier to initiate a trade remedy case against (mostly Mexican) exports to the United States. While some in Congress support adding a seasonal AD/CVD proposal as part of NAFTA renegotiations, others in Congress and most U.S. food and agricultural groups—including U.S. fruit and vegetable producer groups—oppose the proposal. Some also worry that efforts to push for seasonal protections, among other U.S. proposals, could derail agricultural provisions in the NAFTA renegotiation.

USTR's Agriculture-Related NAFTA Objectives

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative's (USTR) agriculture-related NAFTA negotiating objectives cover agricultural market access and regulatory cooperation, sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS)2 measures (including agricultural biotechnology), geographical indications (GIs),3 and trade remedies for perishable and seasonal products in AD/CVD proceedings, among other general provisions addressing dispute settlement and regulatory harmonization.4 Selected USTR agriculture-related objectives are shown in the text box below. The Administration's most recent market access objectives for U.S. agriculture specifically target remaining Canadian tariffs on imports of U.S. dairy, poultry, and egg products that are subject to tariff-rate quotas (TRQs)5 and certain technical barriers to U.S. grain and alcohol beverages.

Potential opportunities for the U.S. food and agriculture industries as part of the ongoing NAFTA renegotiation include the following: improve agricultural market access by liberalizing remaining dutiable agricultural products that were exempted from the original agreement; update NAFTA's SPS provisions by "going beyond" existing World Trade Organization (WTO) obligations regarding risk assessment, transparency, notification, response and enforcement; and address certain outstanding agricultural trade disputes between the United States and its NAFTA partners, including concerns regarding dairy, fruits, vegetables, wine, and a range of SPS and GI concerns.6

|

Summary of USTR's Agriculture-Related NAFTA Negotiating Objectives Agricultural Goods

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS)

Selected Provisions in Other Chapters

|

USTR's Objectives Regarding Seasonal Protections

One of the more controversial agricultural proposals considered by U.S. negotiators would establish seasonal protections for U.S. agriculture in trade remedy cases. The U.S. proposal would "[s]eek a separate domestic industry provision for perishable and seasonal products in AD/CVD proceedings."7 Although the precise text of the proposal is not publicly available,8 the proposal would reportedly protect certain U.S. fruit and vegetable producers by making it easier to initiate trade remedy cases against (mostly) Mexican seasonal exports to the United States. The proposal responds to complaints by some fruit and vegetable producers, mostly in Southeastern states, who claim to be adversely affected by import competition from Mexico.9

Antidumping (AD) and Countervailing Duties (CVD)

Antidumping (AD) and countervailing duties (CVD) address unfair trade practices by providing relief to U.S. industries and workers that are "materially injured," or threatened with injury, due to imports of like products that are sold in the U.S. market at less than fair value (AD) or where production has been subsidized by a foreign government or public entity (CVD). Dumping refers to a form of price discrimination whereby goods are sold in one export market at prices lower than the prices of comparable goods in the home market or in other export markets. Unfair subsidies refer to financial payments and other forms of government support to foreign manufacturers or exporters that might give them an unfair advantage over U.S. producers and comparable domestic goods.

At the end of an investigative process, in AD cases, the remedy is an additional duty placed on the imported merchandise to offset the difference between the price (or cost) in the foreign market and the price in the U.S. market. In CVD cases, a duty equivalent to the amount of subsidy is placed on the imports. The U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) determines if a U.S. industry has suffered material injury, and, if so, the International Trade Administration (ITA) of the U.S. Department of Commerce then determines the existence and amount of dumping or subsidy.10

AD and CVD provisions in U.S. law are in Title VII of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1671-1677n, as amended). U.S. laws and those of other WTO members must comply with obligations under the WTO Antidumping and Subsidies Agreements.11 There are no seasonal provisions under current U.S. laws governing AD/CVD.

CVD law and regulation establish standards for determining when an unfair subsidy has been conferred by a foreign government and is intended to offset any unfair competitive advantage that foreign manufacturers or exporters might have over U.S. producers because of foreign countervailable subsidies. Such subsidies provide financial assistance to benefit the production, manufacture, or exportation of goods (e.g., either through direct cash payments, export subsidies, import substitution subsidies, credits against taxes, or loans at terms below market rates). The amount of subsidies the foreign producer receives from the government is the basis for the subsidy rate by which the subsidy is offset, or "countervailed," through higher import duties.

AD law and regulations authorize higher duties on imported goods if ITA determines that an imported product is being sold at less than its fair value and if the USITC determines that a U.S. producer is thereby being injured.

If an AD/CVD investigation results in final affirmative determinations by both agencies, the ITA issues an AD or CVD order directing U.S. Customs and Border Protection to collect duties on the imported merchandise.

Previous USITC investigations have highlighted the increased competitive market and trade pressures on U.S. fruit producers from lower-cost foreign fruit and vegetable producers (such as those in China, Thailand, Chile, Argentina, and South Africa) as well as from countries with subsidized fruit and vegetable production (such as in the European Union, including Spain).12 Import injury investigations initiated by the United States further highlight concerns that some countries might be supplying imports at prices below fair market value. Since the 1990s, dumping petitions filed by the U.S. fruit and vegetable sectors have included charges against imports of fresh tomatoes (Canada, Mexico), frozen raspberries (Chile), apple juice concentrate (China), frozen orange juice (Brazil), lemon juice (Argentina, Mexico), fresh garlic (China), preserved mushrooms (China, Chile, India, Indonesia), canned pineapple (Thailand), table grapes (Chile, Mexico), and tart cherry juice (Germany, former Yugoslavia).13 Many of these petitions were decided in favor of U.S. domestic producers and resulted in higher tariffs being assessed on U.S. imported products from some of these countries.

In addition, seasonal tariffs—for example, higher import tariffs for certain fruits and vegetables imported during U.S. peak season—are already part of the U.S. tariff schedule for many fruits and vegetables imported from countries under most-favored-nation (MFN) status.14 In the United States, higher MFN seasonal tariffs apply to berries, melons, citrus, pears, stonefruit, tomatoes, cucumbers, asparagus, eggplant, cole crops,15 legumes, and tropical products.

USTR's Seasonal AD/CVD Proposal

Specific details regarding USTR's perishable and seasonal proposal for NAFTA are not publicly available. However, according to groups that are supporting such a provision, the proposal would establish new rules for seasonal and perishable products, such as fruits and vegetables, and ensure that producers who are susceptible to trade surges at certain times of the year have recourse to trade remedies.16 It would also address practices that adversely affect trade in perishable and cyclical crops while also improving import relief mechanisms. Other reports indicate that the proposal seeks to modify U.S. AD/CVD laws by allowing growers to bring an injury case by domestic region and draw on seasonal data.17

This differs from current law, which requires that an injury case be supported by a majority (at least 50%) of the domestic industry, whereas USTRs seasonal proposal would allow regional groups representing less than 50% of nationwide seasonal growers to initiate an injury.18 This would make it easier for a group of regional producers to initiate trade remedy cases even if the majority of producers within the industry, or in other regions, do not support initiating an injury case. As will be discussed later, such a change to U.S. trade laws could further deepen divisions in the fruit and vegetable industry regarding the proposal. Also, under current law, three years of annual data are necessary to prove injury, whereas the proposal would allow for the use of seasonal data to prove injury.19 Although an industry can currently initiate an AD/CVD case under U.S. law, such efforts can often be costly to initiate, time-consuming, and difficult to prove. USTR's proposal would require a change in AD/CVD requirements, making it easier for a group of regional producers to initiate an injury case and make it easier to prove injury and thus institute higher tariffs on imported products.

Produce Imports from Mexico

Trends in U.S. Imports

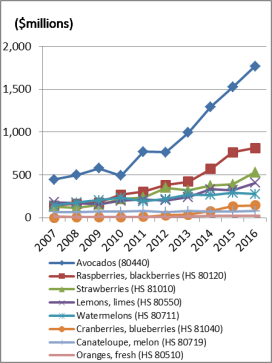

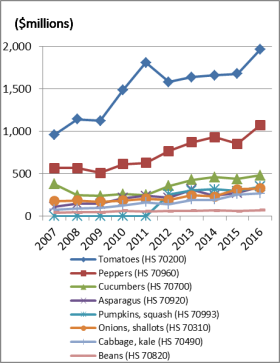

Mexico's production of some fruits and vegetables—tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, squash, berries, and melons—has increased sharply in recent years. Increased supplies have contributed to increased U.S. imports for many types of fruits and vegetables from Mexico, particularly for tomatoes, avocados, peppers, and berries (Figure 1, Figure 2). Researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) report that Mexico is the largest foreign supplier of U.S. imports of vegetables and fruits (excluding bananas).20

In large part, Mexico's increased production and export supplies are attributable to its investment in large-scale greenhouse production facilities and other types of technological innovations, among other factors.21 Studies have highlighted that Mexico's "protected agriculture" represents a "fast-growing activity in Mexico with a large potential to increase yield, quality, and market competiveness."22 Over the years, USDA has conducted a series of studies regarding greenhouse tomato production. These studies also highlight how rapidly increased greenhouse production has impacted North American markets, resulting in a series of AD cases among the NAFTA countries.23 The most well-known case dates back to 1996, when the U.S. tomato industry filed an AD petition alleging that Mexican tomato producers/exporters were selling tomatoes in the United States at less than fair value, which lasted until 2013 under an agreement suspending the AD investigation on fresh tomatoes from Mexico.24

|

|

|

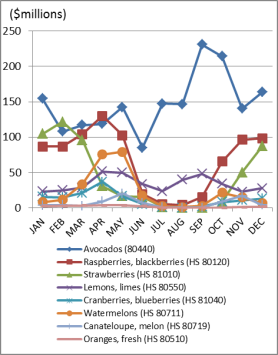

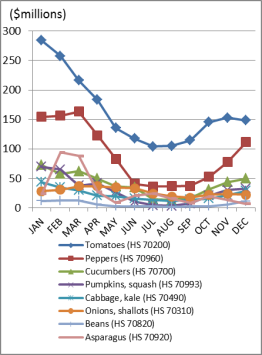

Rising imports from Mexico are generally regarded as supporting rising consumer demand for fruits and vegetables by ensuring year-round counter-seasonal supplies of products, including during the U.S. off-season (or winter months) for some products. Counter-seasonal fruit and vegetable imports are said to complement U.S. production and are generally considered to have a positive impact on U.S. consumer demand by ensuring year-round supply.25 Fruit (Figure 3) and vegetable (Figure 4) imports from Mexico tend to be higher during the winter months (complementary). Counter-seasonal imports may also benefit consumers through lower costs, given a wider supply network, and may also stimulate additional demand by introducing new products and varieties. However, technological and production improvements may be further altering this trend. For example, greenhouse production may allow for year-round production, including during U.S. peak season. In addition, the development of early- and late-maturing varieties has expanded U.S. production seasons, allowing producers to grow many types of fruits and vegetables throughout the year. Improvements in transportation and refrigeration have also made it easier to ship fresh horticultural products.

|

|

|

As the U.S. production season has expanded, the winter window for some imports has narrowed, and imports of some fruits and vegetables are now directly competing with U.S. production. Across all countries importing to the United States, products facing steeper competition from imports include fresh tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, onions, cucumbers, melons, citrus, grapes, apples, and other tree fruits. Imports of processed fruit and vegetable products, including fruit juices, directly compete with U.S. processed products year-round.

With respect to U.S. imports from Mexico under NAFTA, analysis from USDA researchers suggest that although imports continue to supplement U.S. supplies during the year, imports from Mexico may be outcompeting certain Florida-grown crops, particularly for tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, raspberries, and blueberries, particularly of greenhouse-grown crops.26 Rising imports also exacerbate an already sizeable and widening trade deficit in U.S. fruit and vegetable trade.27

Imports as a Share of Total U.S. Supplies

As imports have risen, so have imports as a share of total U.S. domestic supplies and consumption for some fresh and processed fruits and vegetables, according to data from USDA (Table 1). Total imports from all U.S. suppliers accounted for 32% of all U.S. fresh fruit supplies (excluding bananas) in 2007, rising to 38% in 2016. Fresh vegetable imports accounted for 20% of all U.S. supplies in 2007, rising to 31% in 2016. These averages mask even larger import shares for some fruits and vegetables. For example, imports of fresh cucumbers accounted for 52% of U.S. supplies in 2007, rising to 74% in 2016. Imports of fresh tomatoes rose from 41% of supplies in 2007 to 57% in 2016. Imports of avocados accounted for 86% in 2016, up from 65% a decade earlier. Imports of asparagus now account for nearly all U.S. supplies.

|

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

|

|

(Import percentage) |

||||

|

All fresh fruit, excluding bananas |

32 |

32 |

36 |

38 |

|

Avocados, fresh |

65 |

73 |

83 |

86 |

|

Blueberries, fresh |

44 |

49 |

52 |

57 |

|

Raspberries, fresh |

48 |

51 |

58 |

48 |

|

Strawberries, fresh |

8 |

9 |

13 |

14 |

|

Oranges, fresh |

11 |

8 |

9 |

12 |

|

All fresh vegetables |

20 |

24 |

27 |

31 |

|

Asparagus, fresh |

78 |

89 |

90 |

96 |

|

Broccoli, fresh |

11 |

15 |

17 |

19 |

|

Cucumbers, fresh |

52 |

62 |

69 |

74 |

|

Bell peppers, total |

48 |

53 |

59 |

60 |

|

Tomatoes, fresh |

41 |

53 |

53 |

57 |

Source: CRS from USDA data: Fruit and Tree Nut Yearbook Tables (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/fruit-and-tree-nut-data/fruit-and-tree-nut-yearbook-tables/) and other Yearbook Tables covering fresh and processed vegetables (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/vegetables-and-pulses-data/yearbook-tables/).

Notes: Calculated from available import data compared to either total supplies or commercial disappearance.

Support for Mexico's Protected Agriculture28

The Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association (FFVA) claims that Mexico's investment in its greenhouse production has been supported by government subsidies that should be addressed through higher CVDs on U.S. imports of some products.29 Concerns have mostly centered on U.S. imports of tomatoes, peppers, strawberries, raspberries, and blueberries.

Limited information is available regarding support or incentives for Mexico's fruit and vegetable sectors. Available information indicates that Mexico's agricultural ministry, SAGARPA, does not provide direct financial support to its produce growers. SAGARPA's primary agricultural support program, PROAGRO Productivo, comprises most of its agricultural budget. In general, Mexico's farm programs support rural and/or entrepreneurial development, including production by new farmers and women, and also domestic feeding programs.30 Overall, Mexico's producers of sugar, corn, and milk receive the highest level of support across all programs.31 (The Appendix provides additional information regarding the Mexican government's support for its agricultural sectors.) However, available support may be part of Mexico's overall support geared to rural and business development and other productivity improvements in Mexico's horticultural sectors.32 Such support may be assisting the cost of investments in Mexican greenhouses and shade houses but cannot be confirmed based on publicly available information.

FFVA claims that SAGARPA spent $50 million from 2001 to 2008 on 1,220 hectares of greenhouses and other forms of protected agriculture and spent $189.2 million from 2009 to 2010 on 2,500 hectares of protected agriculture.33 FFVA claims that expenditures for 2009-2010 covered greenhouses (65%), shade houses (25%), macro-tunnels (7%), and micro-tunnels (3%). FFVA claims this support focused on production of tomatoes, cucumbers, bell peppers, berries, zucchini, grapes, brussels sprouts, habanero peppers, and green peppers, among other specialty products. Another 2010 study also highlights that support for greenhouse tomatoes was available from the Mexican government's Alianza program, which is still in operation.34

FFVA claims that SAGARPA has continued to provide support for its protected agriculture sectors. It contends that existing "regulations specifically authorize greenhouse 'incentives' of up to $48,000 per hectare" while "subsidies for new greenhouse installations are as high as $162,000 per agricultural project." 35 FFVA claims that greenhouse funds can cover up to 50% of the investment costs and may be used to purchase materials, equipment, and infrastructure and for the management, conservation, and processing of greenhouse products.

In addition, FFVA also claims that Mexico's fruit and vegetable imports are sold to the United States at prices below the cost of production and alternatively could be countered by imposing higher AD duties. FFVA further claims that Mexico's labor cost advantage in fruit and vegetable production gives Mexico additional competitive advantage over U.S. produce growers.36

Support and Opposition for a Seasonal Provision

The perishable and seasonal provisions in USTR's NAFTA objectives have divided the U.S. fruit and vegetable industry, and opinions are split between producers in some Southeastern states and producers in other states, such as California. Opinions in Congress are also divided. For example, at a House Agriculture Committee hearing in July 2017, producer groups representing FFVA broadly claimed that import competition from Mexico of fruits and vegetables under NAFTA is affecting producers across the United States, claiming that "all the specialty crop producers in this country are having a problem with the current NAFTA trade relationship."37 This claim was in part countered by a committee member, Representative Jimmy Panetta, who stated that NAFTA is benefitting fruit and vegetable producers in California and that countercyclical production between California and Mexico is complementary, as some producers have production facilities in both the United States and Mexico.38 Information on the extent that U.S. companies may be engaged in fruit and vegetable production in Mexico is not available.

Some in Congress support USTR's seasonal proposal, claiming that it is necessary to address perceived unfair trading practices by Mexican exporters of fresh fruits and vegetables.39 Others in Congress oppose including the proposal, contending that seasonal production complements rather than competes with U.S. growing seasons. They also worry that it could open the door to an "uncontrolled proliferation of regional, seasonal, perishable remedies against U.S. exports."40 Most U.S. food and agricultural groups, including some U.S. fruit and vegetable producer groups, also oppose seasonal proposals.41 Some worry that efforts to push for seasonal protections, among other U.S. proposals, could derail agricultural provisions in the NAFTA renegotiation. Some claim that the proposal is intended to favor a few "politically-connected, wealthy agribusiness firms from Florida" at the expense of others in the U.S. produce industry42 and at the expense of both consumers and growers in other fruit and vegetable producing states, such California and Washington.43 In general, the U.S. agricultural sectors have not broadly supported proposals that could potentially damage existing export markets under NAFTA.44

Mexican trade officials do not support seasonal proposals, nor do they support limiting access for some products.45 Reports indicate that the United States intended to table the proposal during the first round of the negotiations, but pushback forced it to hold the proposal back.46 Other reports indicate that Mexico is considering retaliation by including its own list of protected products in response to the U.S. proposal. Such a list could include certain grain and pork products and other types of limitations to protect Mexican products in certain production areas. Some U.S. agricultural groups have expressed concerns about "negotiating at the edges" and carving out certain products for special treatment as part of the NAFTA renegotiation.47 Former U.S. trade officials have also expressed skepticism about whether efforts to limit imports would benefit U.S. producers.48

American food and agricultural producers continue to express concerns about the Trump Administration's threats to withdraw from the agreement. A broad coalition of U.S. agricultural groups claim that "withdrawal from NAFTA would result in substantial harm to the U.S. economy generally, and U.S. food and agriculture producers, in particular."49 Agriculture groups also remain concerned about growing uncertainty in U.S. trade policy and the potential for the ongoing NAFTA renegotiation to disrupt U.S. export markets.50 Economic studies commissioned by some U.S. agriculture groups claim that 43.3 million jobs—about one-fourth of all U.S. employment—are connected to the food and agriculture industries.51 Some in Congress continue to support maintaining U.S. agricultural export markets under most preferential trade agreements, including NAFTA.

The U.S. food and agriculture industries have much at stake in the current NAFTA renegotiations. Canada and Mexico are the United States' two largest trading partners, accounting for 28% of the total value of U.S. agricultural exports and 39% of its imports in 2016. Under NAFTA, U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico have increased sharply, rising from $8.7 billion in 1992 to $38.1 billion in 2016.52 The United States supplies 58% of Canada's and 71% of Mexico's agricultural imports.53

Appendix. Government Support for Mexico's Agricultural Sectors

Mexico's agricultural policies have undergone a series of changes in the past few decades. Previously, Mexico's policies were a combination of price support and general consumption subsidies. Starting in the 1980s, Mexico initiated unilateral reforms to its agricultural sector, eliminating its state enterprises related to agriculture and removing price supports and subsidies for staple commodities.54 In addition, as part of reforms to Mexico's agrarian laws, lands that had been distributed to rural community groups following the 1910 revolution were allowed to privatize. Additional domestic reforms in agriculture coincided with negotiations under NAFTA beginning in 1991 and continued beyond the implementation of NAFTA in 1994. Another major reform was the 1999 abolishment of CONASUPO, Mexico's primary agency for government intervention in agriculture.55

In 1993, Mexico introduced PROCAMPO (now named PROAGRO Productivo), a domestic agricultural support program with a budget of about U.S. $1 billion (2013 data) across all agricultural sectors.56 According to USDA:

The program was created to facilitate the transition under NAFTA to more market oriented policies from the previous system of guaranteed prices. It provides direct cash payments at planting time on a per hectare basis to growers of many crops, including feed grains as well as oilseeds. Initially, PROCAMPO was designed to be in place until the 2008-2009 fall-winter crop cycles. However, the Felipe Calderon administration (2006-2012) decided to extend the program until 2012 with some minor changes.57

PROAGRO Productivo continues to target rural development and poverty alleviation and is intended to help producers cope with lower trade protections and the removal of direct price supports through direct payments to rural producers.58 The program grants direct supports to growers with farms in operation that are appropriately registered in the PROAGRO directory. It provides a flat rate payment to farmers with production areas based on the size of their production unit as follows:59

- Subsistence growers with up to five hectares (about 12.4 acres) of non-irrigated land and 0.2 hectares (about 0.5 acres) of irrigated land, as well as subsistence growers with up to three hectares (about 7.4 acres) of non-irrigated land for units located within specific municipalities;

- Transition growers with more than five hectares and up to 20 hectares (about 50 acres) of non-irrigated land and more than 0.2 hectares and up to five hectares of irrigated land; and

- Commercial growers with more than 20 hectares non-irrigated land and more than five hectares irrigated land.

"Subsistence" growers located within specific municipalities with up to three hectares of non-irrigated land receive the largest amount of support payment per hectare for their production units at 1,500 pesos (about $82/hectare or $33/acre). Others outside these municipalities get about 1,300 pesos (about $71/hectare or $29/acre). "Transition" production units receive 800 pesos per hectare (about $44/hectare or $18/acre) and "commercial" production units receive 700 pesos per hectare (about $38/hectare or $15/acre). The maximum subsidy amount that a grower can receive under PROAGRO Productivo cannot exceed 100,000 pesos (roughly U.S. $7,750) per crop cycle.

Available information indicates that PROAGRO mostly supports corn, sorghum, wheat, and rice production.60 Other information further indicates that, overall, Mexico's producers of sugar, corn, and milk receive the highest level of support across all programs.61

As a member of the WTO, Mexico has committed to abide by WTO rules and disciplines, including those that govern domestic farm policy. The WTO's Agreement on Agriculture spells out the rules for countries to determine whether their policies for any given year are potentially trade-distorting, how to calculate the costs of any distortion, and how to report those costs to the WTO in a public and transparent manner. As part of each member's obligations and commitments, each country is required to file periodic notifications of its agricultural domestic support measures and export subsidies for review by the relevant bodies of the WTO.62

Mexico's most recent notification to the WTO of its domestic farm program spending lists the following agricultural support measures:63

- Food Support Programme;

- Rural Supply Programme;

- Milk Supply Programme;

- PROMUSAG: Programme for Women Working in the Agricultural Sector;

- PROMETE: Programme in Support of Production Projects by Women Entrepreneurs;

- FAPPA: Support Fund for Production Projects in Agrarian Clusters;

- Young Rural Entrepreneur Programme;

- COUSSA: Conservation and Sustainable Use of Soil and Water;

- Small-Scale Hydraulic Works Construction Programme;

- Native Mexican Maize (Corn) Conservation Programme;

- PRODEZA: Arid Zone Development Programme;

- PESA: Strategic Food Security Programme; and

- PROAGRO Productivo (formerly PROCAMPO).

In general, these programs provide support for rural and/or entrepreneurial development focused on poverty alleviation, domestic feeding programs, and production by new farmers and women.

Mexico identifies each of these programs to be non-trade-distorting (i.e., "green box" programs that are considered to be minimally or non-trade distorting and are not subject to any spending limits under WTO rules). Overall, Mexico's producers of sugar, corn, and milk receive the highest level of support across all programs.64 There do not appear to be domestic farm programs that provide direct support to Mexico's fruit and vegetable growers among the notified programs listed above. Limited other information is available regarding support or incentives for Mexico's fruit and vegetable sectors. Available information indicates that Mexico does not provide direct financial support to its produce growers, which is similar to the situation that prevails in the United States.

Mexico's notification of its agricultural export subsidies covers only maize (corn), beans, wheat, sorghum, and sugar.65 Available information does not indicate existing export subsidies benefitting Mexico's fruit and vegetable growers.

For purposes of comparison with U.S. government support for its fruit and vegetable sectors, see CRS Report R42771, Fruits, Vegetables, and Other Specialty Crops: Selected Farm Bill and Federal Programs, and also CRS Report R43632, Specialty Crop Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79).