Introduction

Waste discharges from municipal sewage treatment plants into inland and coastal waters are a significant source of water quality problems throughout the country.1 Pollutants associated with municipal discharges include nutrients (which can stimulate growth of algae that can deplete dissolved oxygen or produce harmful toxins), bacteria and other pathogens (which may impair drinking water supplies and recreation uses), and metals and toxic chemicals from industrial and commercial activities and households.

The collection and treatment of wastewater remains among the most important public health interventions in human history and has contributed to a significant decrease in waterborne diseases during the past century.2 Funding these systems continues to be of interest to federal, state, and local officials and the general public.

Background

The Clean Water Act (CWA)3 establishes performance levels to be attained by municipal sewage treatment plants in order to prevent the discharge of harmful quantities of waste into surface waters and to ensure that residual sewage sludge meets environmental quality standards. It requires secondary treatment of sewage (equivalent to removing 85% of raw wastes),4 or treatment more stringent than secondary, where needed to achieve water quality standards necessary for recreational and other uses of a river, stream, or lake.

Over the past 40-plus years since the CWA was enacted, the nation has made considerable progress in controlling and reducing certain kinds of chemical pollution of rivers, lakes, and streams, much of it because of investments in wastewater treatment. Between 1968 and 1995, oxygen-depleting pollution5 discharged from sewage treatment plants nationwide declined by 45% despite increased industrial activity and a 35% growth in population. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and others argue that without continued infrastructure improvements, future population growth will erode many of the CWA achievements made to date in pollution reduction.6

The total population served by sewage treatment plants that provide a minimum of secondary treatment increased from 85 million in 1972 to 234 million in 2012,7 representing 74% of the U.S. population at that time.8 About four million people are served by facilities that provide less than secondary treatment, but, according to EPA, these facilities have CWA conditional waivers from the secondary treatment requirement.9 About 21% of households are served by on-site septic systems, not by centralized municipal treatment facilities.10

Despite improvements, other water quality problems related to municipalities remain to be addressed. A key concern is "wet weather" pollution: overflows from combined sewers (sewers that carry sanitary and industrial wastewater, groundwater infiltration, and stormwater runoff that may discharge untreated wastes into streams) and sanitary sewers (sewers that carry only sanitary waste). Untreated discharges from these sewers, which typically occur during rainfall events, can cause serious public health and environmental problems, yet costs to control wet weather problems are high in many cases. In addition, toxic wastes discharged from industries and households to sewage treatment plants cause water quality impairments, operational upsets, and contamination of sewage sludge.

Estimated Funding Needs

Although approximately $95 billion in CWA assistance has been provided since 1972, funding needs for wastewater infrastructure remain high. According to the most recent estimate by the EPA and the states,11 the nation's wastewater treatment facilities will need $271 billion over the next 20 years to meet the CWA's water quality objectives. This estimate includes

- $197 billion for wastewater treatment and collection systems, which represent 73% of all needs;12

- $48 billion for combined sewer overflow corrections;

- $19 billion for stormwater management; and

- $6 billion to build systems to distribute recycled water.

These estimates do not include potential costs, largely unknown, to upgrade physical protection of wastewater facilities against possible terrorist attacks that could threaten water infrastructure systems, an issue of significant interest since September 11, 2001.

Needs for small communities represent about 12% of the total. The largest needs in small communities are for new conveyance systems (e.g., pipes), secondary treatment, system repair, and advanced treatment. Five states—New York, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Texas, and Alabama—accounted for 30% of the small community needs.

Funding for Wastewater Treatment Activities

In addition to prescribing municipal treatment requirements, the CWA authorizes the principal federal program to support wastewater treatment plant construction and related eligible activities. Congress established this program in the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 (P.L. 92-500), significantly enhancing what had previously been a modest grant program. Since then, Congress has appropriated approximately $95 billion to assist cities in complying with the act and achieving the overall objectives of the act: restoring and maintaining the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters.

Title II of P.L. 92-500 authorized grants to states for wastewater treatment plant construction under a program administered by the EPA. Federal funds were provided through annual appropriations under a state-by-state allocation formula contained in the act. The formula (which has been modified several times since 1972) was based on states' financial needs for treatment plant construction and population. States used their allotments to make grants to cities to build or upgrade categories of wastewater treatment projects, including treatment plants, related interceptor sewers, correction of infiltration/inflow of sewer lines, and sewer rehabilitation.

Amendments enacted in 1987 (P.L. 100-4) initiated a new program to support, or capitalize, State Water Pollution Control Revolving Funds (SRFs). States continue to receive federal grants, but now they provide a 20% match and use the combined funds to make loans to communities. Monies used for construction are repaid to states to create a "revolving" source of assistance for other communities.

In FY1989 and FY1990, Congress provided appropriations for both the Title II and Title VI programs. The SRF program fully replaced the Title II program in FY1991. However, during the transition from Title II to Title VI, Congress began to provide earmarked water infrastructure grants to individual communities and regions. In subsequent years, the earmarked funds accounted for a significant amount of the total appropriation. General opposition to congressional earmarking stopped the practice in FY2011. Special project appropriations since that time have supported Alaska Native Village and U.S.-Mexico Border projects.13

Federal contributions to SRFs were intended to assist a transition to full state and local financing by FY1995. SRFs were to be sustained through repayment of loans made from the fund after that date. The intention was that states would have greater flexibility to set priorities and administer funding in exchange for an end to federal aid after 1994, when the original CWA authorizations expired. However, although most states believe that the SRF is working well today, early funding and administrative problems plus remaining funding needs (discussed below) delayed the anticipated shift to full state responsibility. Congress has continued to appropriate funds to assist wastewater construction activities.

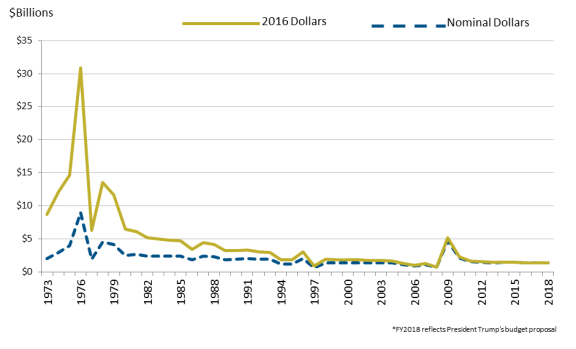

Figure 1 illustrates the history of EPA wastewater infrastructure appropriations in both nominal dollars and constant (2016) dollars. The increase in FY2009 is due to a $4.0 billion increase in supplemental funds under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). As the figure indicates, the funding level has remained relatively stable over the past seven fiscal years. In both FY2016 and FY2017, Congress provided $1.394 billion for the clean water SRF program. The President's FY2018 budget proposal requests the same amount as the previous two fiscal years.

|

Figure 1. EPA Wastewater Infrastructure Annual Appropriations Nominal and Constant (2016) Dollars |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS. Constant dollars calculated from Office of Management of Budget, Table 10.1, "Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940–2022," https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals. Notes: FY2009 appropriation total included $4.0 billion in supplemental funds under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). |

Clean Water State Revolving Fund Program

The SRF program represented a major shift in how the nation finances wastewater treatment needs. In contrast to the Title II construction grants program, which provided grants directly to localities, SRFs are loan programs. States use their SRFs to provide several types of loan assistance to communities, including project construction loans made at or below market interest rates, refinancing of local debt obligations, providing loan guarantees, and purchasing insurance. States may also provide additional loan subsidies (including forgiveness of principal and negative interest loans) in certain instances. Loans are to be repaid to the SRF within 30 years beginning within one year after project completion, and the locality must dedicate a revenue stream (from user fees or other sources) to repay the loan to the state.

States must agree to use SRF monies first to ensure that wastewater treatment facilities are in compliance with deadlines, goals, and requirements of the act. After meeting this "first use" requirement, states may also use the funds to support other types of water quality programs specified in the law, such as those dealing with nonpoint source pollution and protection of estuaries. The CWA identifies a number of types of projects and activities as eligible for SRF assistance. The Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 amended the list by adding several projects and activities.14 The current list includes15

- wastewater treatment plant construction,

- stormwater treatment and management,

- replacement of decentralized treatment systems (e.g., septic tanks),

- energy-efficiency improvements at treatment works,

- reuse and recycling of wastewater or stormwater, and

- security improvements at treatment works.

States must also agree to ensure that communities meet several specifications (such as requiring that locally prevailing wages be paid for wastewater treatment plant construction pursuant to the Davis-Bacon Act).16 In addition, SRF recipients must use American-made iron and steel products in their projects.17

As under the previous Title II program, decisions on which projects will receive assistance are made by states using a priority ranking system that typically considers the severity of local water pollution problems, among other factors. States also evaluate financial considerations of the loan agreement (interest rate, repayment schedule, the recipient's dedicated source of repayment) under the SRF program.

All states have established the legal and procedural mechanisms to administer the loan program and are eligible to receive SRF capitalization grants. Some with prior experience using similar financing programs moved quickly. Others had difficulty in making a transition from the previous grants program to one that requires greater financial management expertise for all concerned. More than half of the states currently leverage their funds by using federal capital grants and state matching funds as collateral to borrow in the public bond market for purposes of increasing the pool of available funds for project lending. Cumulatively since 1988, leveraged bonds have comprised about 35% of total SRF funds available for projects; loan repayments comprise about 40%.18

Small communities and states with large rural populations have had challenges with the SRF program. Many small towns did not participate in the previous grants program and were more likely to require major projects to achieve compliance with the law. Yet many have limited financial, technical, and legal resources and encountered difficulties in qualifying for and repaying SRF loans. These communities often lack an industrial tax base and thus face the prospect of very high per capita user fees to repay a loan for the full capital cost of sewage treatment projects. Compared with larger cities, many are unable to benefit from economies of scale, which can affect project costs. However, since 1989, 66% of all loans and other assistance (comprising 22% of total funds loaned) have gone to assist towns and cities with populations of less than 10,000.19

Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program

The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act of 2014 (WIFIA) program provides another source of financial assistance for water infrastructure. Congress established the WIFIA program in the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA, P.L. 113-121).20 The act, among other provisions, authorizes EPA to provide credit assistance (e.g., secured/direct loans or loan guarantees) for a range of wastewater and drinking water projects. Project costs must be $20 million or larger to be eligible for credit assistance. In rural areas (defined as populations of 25,000 or less), project costs must be $5 million or more. To fund this five-year pilot program, Congress authorized to be appropriated a total of $1.75 billion from FY2015 through FY2019.

In 2016, Congress appropriated the first funds to cover the subsidy cost of the program,21 providing $20 million to EPA to begin making loans, and allowed the agency to use up to $3 million of the total for administrative purposes. In May 2017, Congress provided an additional $8 million for EPA to apply toward loan subsidy costs and an additional $2 million for EPA's administrative expenses.22

EPA expects to issue its first WIFIA loans in 2017.23 From the federal perspective, an advantage of WIFIA is that it can provide a large amount of credit assistance relative to the amount of budget authority provided. The volume of loans and other types of credit assistance that the programs can provide is determined by the size of congressional appropriations and calculation of the subsidy amount. EPA stated that the combined appropriation for subsidy costs ($25 million) will allow the agency to lend approximately $1.5 billion for water infrastructure projects.24 The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget proposal requested $29 billion to cover subsidy costs, which it estimated could provide $1.9 billion in credit assistance.25

Other Federal Assistance Programs26

In addition to the water infrastructure assistance programs discussed above, which are administered by EPA, other federal agencies implement broader programs that may provide assistance for wastewater infrastructure projects.

Department of Agriculture

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) operates grant and loan programs for drinking water supply and wastewater facilities in rural areas, defined as areas of not more than 10,000 persons. For FY2017, Congress appropriated $571 million for USDA water and waste disposal grants and loans. For FY2018, the President's budget request proposed to eliminate funding for these programs.

Department of Housing and Urban Development

The Department of Housing and Urban Development administers the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. For FY2017, Congress provided $3.1 billion for these funds. Water and waste disposal projects compete with many other CDBG-funded public activities and have accounted for approximately 10% of total grant disbursements in recent years.27

Department of Commerce

The Department of Commerce's Economic Development Administration (EDA) provides project grants for construction of public facilities—including, but not limited to, water and sewer systems—as part of approved overall economic development programs in areas of lagging economic growth. For FY2017, the public works and economic development program is funded at $100 million.

How Localities Pay for Construction Costs

The federal government directly funds only a small portion of the nation's annual wastewater treatment capital investment. State and local governments provide the majority of needed funds. Local governments have primary responsibility for wastewater treatment: They own and operate approximately 15,000 treatment plants nationwide.28 Construction of these facilities has historically been financed with revenues from federal grants, state grants to supplement federal aid, and broad-based local taxes (property tax, retail sales tax, or, in some cases, local income tax). Where grants are unavailable—and especially since SRFs were established—local governments often seek financing by issuing bonds and then levying fees or charges on users of public services to repay the bonds in order to cover all or a portion of local capital costs. Almost all such projects are debt-financed (not financed on a pay-as-you-go basis from ongoing revenues to the utility). The principal financing tool that local governments use is issuance of tax-exempt municipal bonds. The vast majority of U.S. water utilities rely on municipal bonds and other debt to some degree to finance capital investments.29

Shifting the CWA aid program from categorical grants to the SRF loan program had the practical effect of making localities ultimately responsible for nearly 100% of project costs rather than less than 50% of costs.30 This has occurred concurrently with other financing challenges—including the need to fund other environmental services, such as drinking water and solid waste management—and increased operating costs. (New facilities with more complex treatment processes are more costly to operate.) Options that localities face, if intergovernmental aid is not available, include raising additional local funds (through bond issuance, increased user fees, developer charges, or general or dedicated taxes), reallocating funds from other local programs, or failing to comply with federal standards. Each option carries with it certain practical, legal, and political problems.

Legislative Activity

Historical Activity

Authorizations of appropriations for SRF capitalization grants expired in FY1994, making this an issue of congressional interest. Appropriations have continued, as shown in Figure 1. In the 104th Congress, the House passed a comprehensive reauthorization bill (H.R. 961), which included SRF provisions to address problems that have arisen since 1987, including assistance for small and disadvantaged communities and expansion of projects and activities eligible for SRF assistance. However, no legislation was enacted because of controversies over other parts of the bill.

One focus has been on projects needed to control wet weather water pollution (i.e., overflows from combined and separate stormwater sewer systems). The 106th Congress authorized $1.5 billion of CWA grant funding specifically for wet weather sewerage projects (in P.L. 106-554), because under the SRF program, wet weather projects compete with other types of eligible projects for available funds. However, authorization for these wet weather project grants expired in FY2003 and has not been renewed. No funds were appropriated.

In several Congresses since the 107th, House and Senate committees have approved bills to extend the act's SRF program and increase authorization of appropriations for SRF capitalization grants, but no legislation has been enacted until recently. Issues debated in connection with these bills included extending SRF assistance to help states and cities meet the estimated funding needs, modifying the program to assist small and economically disadvantaged communities, and enhancing the SRF program to address a number of water quality priorities beyond traditional treatment plant construction—particularly the management of wet weather pollutant runoff from numerous sources, which is the leading cause of stream and lake impairment nationally.

The 113th Congress enacted considerable changes to the SRF provisions of the CWA in 2014 (P.L. 113-121). These amendments addressed several issues, including extending loan repayment terms from 20 years to 30 years, expanding the list of SRF-eligible projects, increasing assistance to Indian tribes, and imposing "Buy American" requirements on SRF recipients. The act also added a new provision that allows SRF grants to be used for "forgiveness of principal" and "negative interest loans" under certain conditions.

The 2014 amendments did not address other long-standing or controversial issues, such as authorization of appropriations for SRF capitalization grants (which expired in FY1994), state-by-state allocation of capitalization grants,31 and applicability of prevailing wage requirements under the Davis-Bacon Act (which currently apply to use of SRF monies).

As noted, the 2014 legislation also included provisions authorizing a five-year pilot program (WIFIA) for a new type of financing. The WIFIA program authorizes federal loans and loan guarantees for various types of wastewater and public drinking water infrastructure projects. The WIFIA program is intended to assist large water infrastructure projects, especially projects of regional and national significance, and to supplement but not replace other types of financial assistance, such as SRFs. In the Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 114-254), enacted in December 2016, Congress appropriated $20 million to EPA to begin making loans, and it allowed the agency to use up to $3 million of the total for administrative purposes. The Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2017, signed by President Trump on May 5, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), provided an additional $8 million for EPA to apply toward loan subsidy costs and an additional $2 million for EPA's administrative expenses. EPA expects to issue its first WIFIA loans in 2017.32

In the 114th Congress, the Senate passed the Water Resources Development Act (S. 2848), which included several provisions involving wastewater funding. For the most part, these provisions were not included in the final version of this legislation, which Congress enacted in December 2016 (Water Infrastructure and Improvements for the Nation Act, P.L. 114-322).33

Legislative Proposals in the 115th Congress

Although interest in meeting the nation's water infrastructure needs is strong and likely to continue, proposals to provide financial assistance to local communities will compete with other objectives, including deficit reduction. It is uncertain how infrastructure programs will fare in these debates.

Legislative proposals introduced in the 115th Congress that include wastewater infrastructure related provisions are highlighted below.34

- H.R. 465 (Water Quality Improvement Act of 2017) would codify an integrated plan and permit approach into the CWA,35 direct EPA to carry out a pilot program to work with at least 15 communities desiring to implement an integrated CWA compliance plan, and require EPA to update its 1997 combined sewer overflow affordability guidance document. It includes provisions that may alter the existing CWA framework.

- H.R. 1068 (Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 2017) and H.R. 1071 (Assistance, Quality, and Affordability Act of 2017) would incorporate in the statute a governor's authority to transfer as much as 33% of the annual drinking water SRF or clean water SRF capitalization grant to the other fund.36

- H.R. 1647 (Water Infrastructure Trust Fund Act of 2017) would direct the Secretary of the Treasury to establish a voluntary product labeling system informing consumers that the manufacturer, producer, or other stakeholder is participating in the Water Infrastructure Investment Trust Fund and contributing to clean water. The Secretary would provide a label for a fee of 3 cents per unit. Funds would be made available only when the clean water SRF appropriation is not less than the average of the five preceding fiscal years. Funds made available for a fiscal year would be split equally between the clean water and drinking water SRF programs.

- H.R. 1673 (Water Affordability, Transparency, Equity, and Reliability Act of 2017) would (1) establish a trust fund with funds going to EPA to support clean water and drinking water SRFs and activities and to the USDA for household water well systems; (2) direct EPA to report on water affordability nationwide, discriminatory practices of water and sewer service providers, and water system regionalization; (3) require states to use at least 50% of their capitalization grants to provide additional subsidization to disadvantaged communities; and (4) require states to permit recipients of SRF assistance to enter into project labor agreements under the National Labor Relations Act.

- H.R. 1971, H.R. 2355, and S. 692 (Water Infrastructure Flexibility Act) would codify an integrated plan and permit approach into the CWA, establish an Office of the Municipal Ombudsman to provide assistance to municipalities, and require EPA to update its 1997 combined several overflow affordability guidance document. It includes provisions that may alter the existing CWA permitting and compliance framework.

- H.R. 2510 (Water Quality Protection and Job Creation Act of 2017) would, among other provisions, amend the CWA (33 U.S.C. §2512) to authorize EPA to issue grants to nonprofit entities to provide technical assistance to rural, small, and tribal municipalities regarding wastewater financing and related issues; reauthorize appropriations for the pollution control grant program (Section 1256); authorize appropriations for the watershed pilot program in Section 1274; amend appropriation authorization for the nonpoint source management program in Section 1329; amend the SRF grant agreement section (Section 1382) to require states to use at least 15% of their SRF grants to provide assistance to municipalities of fewer than 10,000 individuals that meet affordability criteria; amend SRF project eligibility (Section 1383) to allow states to provide a limited amount of grants to (1) treatment works in small (less than 10,000) communities and (2) treatment works for energy and water efficiency activities; amend the priority list provisions (Section 1383) to, among other things, allow for the inclusion of nonpoint source projects; reauthorize appropriations for the SRF program; and reauthorize appropriations for the sewer overflow grant program in Section 1301.

- H.R. 3009 (Sustainable Water Infrastructure Investment Act of 2017) would amend the tax code to provide that the volume cap for private activity bonds shall not apply to bonds for sewage (and drinking water) facilities.

- S. 181 would require the Government Accountability Office to publish a report determining whether a domestic content preference requirement (e.g., iron, steel, and manufactured products) applies to identified federal public works and infrastructure programs, including the clean water SRF. No federal funds or credit assistance could be made available for a program that lacks a domestic content preference.

- S. 518 (Small and Rural Community Clean Water Technical Assistance Act) would authorize EPA to issue grants to qualified nonprofit entities to provide technical assistance to owners and operators of "small" and "medium" wastewater treatment facilities.

- S. 1137 (Clean Safe Reliable Water Infrastructure Act) would codify in statute EPA's existing WaterSense Program and reauthorize combined sewer overflow grants under CWA Section 221.