Introduction

Under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which took effect in January 1994, motor vehicle and vehicle parts manufacturers have integrated their production operations in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. President Donald Trump has criticized the agreement, and on May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration notified Congress of its intent to renegotiate the agreement, as required by the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA).1 The 115th Congress may consider legislation for a "modernization" of NAFTA under TPA, a process by which Congress agrees to expeditiously consider implementing legislation for a trade agreement negotiated by the President, provided he meets certain statutory negotiating objectives and congressional notification and consultation requirements. On July 17, 2017, the Administration announced its objectives in forthcoming negotiations.

This report discusses the development of U.S. motor vehicle production under NAFTA and analyzes the North American motor vehicle market, including production, plant locations, and continental trade patterns. It summarizes the motor vehicle rules of origin in NAFTA and compares them with similar requirements in other trade agreements, and examines how the potential changes in NAFTA might affect the motor vehicle and motor vehicle parts industries in the United States.2

U.S. Motor Vehicle Industry

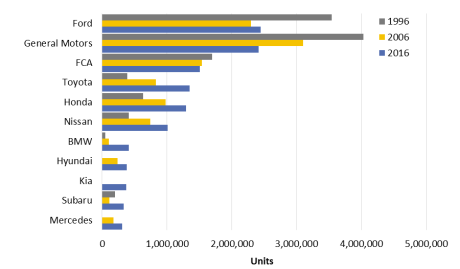

U.S. motor vehicle manufacturing has changed significantly since NAFTA took effect. While U.S. domestic production of finished vehicles has fluctuated somewhat, Mexico has become a major center of parts and motor vehicle manufacturing, fully integrated into the U.S. and Canadian supply chains. The number of European, Japanese, and South Korean automakers with U.S. vehicle production has also grown during this time (Figure 1).

|

|

Source: Ward's Datasheet, U.S. Vehicle Production by Manufacturer. Notes: FCA = Fiat Chrysler Automobile; Chrysler was an independent company until it merged with Daimler in 1998; Daimler sold its Chrysler ownership to Cerberus Capital Management in 2007; Chrysler entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2009; the reorganized company emerged from bankruptcy in June 2009 with Fiat owning a 20% share; Chrysler was merged into Fiat Chrysler in 2014 after Fiat acquired all outstanding shares. Fiat previously had no U.S. automobile production. Hyundai and Mercedes did not produce vehicles in the United States in 1996; Kia did not manufacture vehicles in the United States until after 2006. |

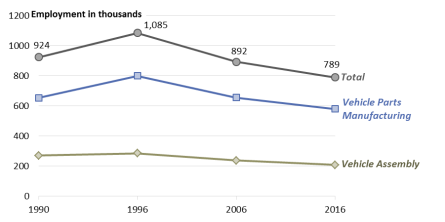

There were nearly 800,000 jobs in U.S. motor vehicle and parts manufacturing in 2016 (Figure 2), with the largest share of employment in parts manufacturing (580,000 in 2016). Since 1996, both vehicle assembly and parts manufacturing employment have decreased by 27%. There are many reasons for changing employment levels, including economic conditions, trade patterns, and technological change.3

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Survey, based on NAICS Codes 3361 (motor vehicle manufacturing), and 3363 (motor vehicle parts and manufacturing). |

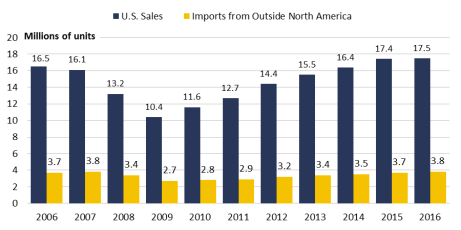

Domestic sales of motor vehicles have recovered from their major decline during the recent recession, and the bankruptcies and restructurings of GM and Chrysler. Sales in 2016 reached 17.5 million units, the highest annual figure on record.4 Imported vehicles—those manufactured outside of North America—have maintained a relatively constant share of total sales (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. U.S. Light Vehicle Sales and Imports Passenger cars, light trucks, and SUVs |

|

|

Source: Ward's Automotive Yearbooks, Ward's Datasheets, and CRS. |

Integration Across North America

Integration of the U.S., Canadian, and Mexican automotive industries began decades before NAFTA. Nevertheless, tariffs and nontariff barriers added additional cost and complicated the flow of components and finished vehicles among the three countries. In some cases, this led manufacturers to produce similar engines, transmissions, or other products in each country, even when it might have been more efficient to manufacture them in a single location. A series of trade agreements and domestic policy changes in each country enabled much closer integration of North American motor vehicle manufacturing.

U.S.-Canada Agreements Before NAFTA

The Canada-U.S. Auto Pact of 1965 was the first step in opening automotive markets in North America.5 Previously, the United States and Canada each imposed tariffs on imported assembled motor vehicles and parts. Although several manufacturers had assembly plants in both countries, if a manufacturer wished to produce an engine in one country and install it in a vehicle assembled in the other country, the engine would be subject to tariffs.

The Auto Pact eliminated tariffs on vehicles and parts for "designated" manufacturers that agreed to maintain minimum production levels in Canada. The pact also required that vehicles and parts have at least 50% U.S. or Canadian content in order to benefit from the tariff exemption. No Japanese or European auto manufacturers produced vehicles in the United States or Canada at the time, and when they later opened plants, they did not benefit from tariff-free movement of parts and vehicles across the border.6 The effect of the Auto Pact was to create an integrated U.S. and Canadian market for motor vehicles and parts, while ensuring that a specified share of vehicle manufacturing remained in Canada.7

As a result of the Auto Pact, U.S. and Canadian motor vehicle industries were generally integrated by the 1980s.8 The agreement did not lead to major changes affecting automotive trade, although it adjusted the system of tariffs applied to imports from Europe, Japan, and other sources outside North America.9 The Auto Pact was incorporated into the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUFTA) that went into force in January 1989.10

Mexico's Manufacturing and NAFTA

Although Mexico was not a party to the 1965 Auto Pact or the 1989 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, the Mexican government took steps during the same time period to encourage the development and growth of manufacturing in Mexico. Mexico's export-oriented industries began in 1965 with the establishment of the maquiladora program, which allowed foreign-owned businesses to set up assembly plants in Mexico to produce for export, as part of the Border Industrialization Program created under President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz.

The Border Industrialization Program was a response to the 1964 termination of the U.S. Bracero Program, which had allowed Mexican workers to cross into the United States for seasonal employment. Under the industrialization program, maquiladoras could import intermediate materials duty-free with the condition that a certain percentage of the final product be exported. Maquiladoras were originally restricted to the U.S.-Mexico border region and normally participated in production sharing with their U.S. facilities.11 Manufacturers in other regions of Mexico faced much more restrictive trade and investment barriers, which were eventually eliminated after NAFTA.

Under Mexico's Border Investment Program, maquiladoras operated under the following special rules:

- lower trade and foreign investment restrictions than other sectors in Mexico;

- access to duty-free imports of intermediate materials with the condition that a percentage of the final production was exported;

- duty-free import of manufacturing equipment with the condition that it would be exported if the company ceased to operate under the program; and

- exemption from Mexican laws requiring majority Mexican ownership and from prohibitions on foreign ownership of real estate near borders and coastlines.

Maquiladora operations increased rapidly during the 1970s and 1980s. As Mexican labor costs were very low compared with those in the United States, U.S.-based automotive manufacturers initially used maquiladoras to make labor-intensive products such as wire harnesses, assemblies of wires that carry electricity to lights, dashboard indicators, and other components. Over time, manufacturers began producing more sophisticated components, such as brakes and suspensions, in maquiladoras.

Maquiladora production of auto parts was intended to supply auto assembly plants in the United States and Canada, and it was not integrated with domestic assembly of automobiles in Mexico. At the time, companies such as General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, and Volkswagen, which were assembling vehicles in Mexico, were subject to trade and investment restrictions under a series of Mexican auto decrees that also required a minimum proportion of Mexican content. (See box below on Mexico's Auto Decrees.) Automobiles produced in Mexico were generally not exported to the United States and Canada and in some cases did not meet U.S. or Canadian safety and emissions standards. Imports of new vehicles from the United States and Canada into Mexico were not allowed prior to 1989.

|

Mexico's Restrictive Auto Decrees Prior to NAFTA Beginning in the 1960s, Mexico had a restrictive import substitution policy through a series of Auto Decrees in which the government sought to supply the entire Mexican market through domestically produced automotive goods. The decrees

In 1989, the government of Mexico liberalized rules governing the auto industry, but did not entirely eliminate them. At the time of NAFTA negotiations, auto manufacturers were still required to have a certain percentage of domestic content in their products and meet export requirements, both of which were considered huge impediments to the industry. In addition, Mexico had tariffs of 20% or more on imports of automobiles and auto parts. These trade restrictions were eliminated under NAFTA.12 |

After NAFTA took effect, Mexico merged the maquiladora operations and Mexican domestic assembly-for-export plants into one program called Maquiladora Manufacturing Industry and Export Services (IMMEX). NAFTA regulations continued to allow maquiladoras to import products duty-free into Mexico, regardless of the country of origin of the products. This phase also allowed maquiladora operations to increase sales to the Mexican domestic market. However, in 2001, rules of origin established in NAFTA replaced the previous special tariff provisions that applied only to maquiladora operations, so that any products that qualified as North American origin could be imported duty-free into Mexico for any purpose. At the same time, some inputs imported by maquiladoras from non-NAFTA countries became subject to Mexican tariffs, raising costs for maquiladoras that imported from countries such as Japan or China.

NAFTA Provisions and the Auto Sector

The market-opening provisions of NAFTA gradually eliminated all tariffs and most nontariff barriers on goods produced and traded within North America over a period of 15 years starting in 1994. Most of the market-opening measures of NAFTA resulted in the removal of tariffs and quotas applied by Mexico on imports from the United States and Canada. Mexican tariffs were substantially higher than those of the United States at the time NAFTA was negotiated. Moreover, many Mexican products entered the United States duty-free under the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences. Prior to NAFTA, the United States assessed the following tariffs on imports from Mexico: 2.5% on automobiles, 25% on light-duty trucks, and a trade-weighted average of 3.1% for automotive parts. In comparison, Mexico's more restrictive tariffs on U.S. and Canadian automotive products were 20% on automobiles and light trucks and 10%-20% on auto parts.13

NAFTA helped lock in Mexico's automotive-industry reforms by phasing out the restrictive auto decrees. It also included the gradual removal of many nontariff barriers to trade, provided for uniform country-of-origin provisions, enhanced protection of intellectual property rights, required less restrictive procurement practices by the Mexican government, and eliminated performance requirements on investors from other NAFTA countries.

North American Integration

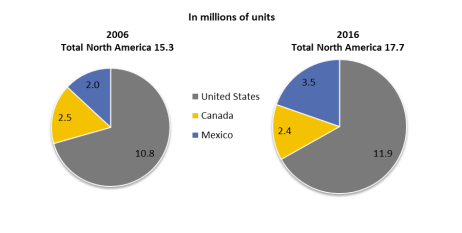

Since NAFTA, North American motor vehicle manufacturing has become highly integrated, with major Asia- and Europe-based automakers constructing their own supply chains within the region.14 The major recent growth in the North American market occurred largely in Mexico, which now accounts for about 20% of total continental vehicle production (Figure 4).15 In general, recent investments in U.S. and Canadian assembly plants have involved modernization or expansion of existing facilities, while Mexico has seen new assembly plants.

In addition, many parts manufacturers have opened plants in Mexico to be close to the growing number of vehicle assembly plants.16 Parts plants in all three countries supply manufacturers of automotive systems (such as brake and seating systems) and motor vehicle assembly plants in the other NAFTA countries. Estimates show that some motor vehicle parts and components cross the U.S. border more than eight times in the production and assembly process.17 Parts trade has grown more rapidly than trade in assembled vehicles. Mexico's exports of parts to the United States have increased by 85% since 2010; U.S. exports of parts to Mexico have grown by 64% over the same period (Figure 5).

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, "U.S. Exports and Imports of Automotive Parts," April 24, 2017, http://www.trade.gov/td/otm/assets/auto/AP_Trade.pdf. |

At least three factors have spurred Mexico's rise as a motor vehicle manufacturing center, in addition to the removal of trade barriers in NAFTA. These include Mexico's lower labor costs,18 the Mexican government's investment in its educational system to graduate engineers and technicians to operate and manage vehicle and parts plants,19 and Mexico's growing network of free trade agreements with many countries outside the NAFTA region. In some cases, Mexico's vehicle exports have tariff-free access to countries that impose tariffs on vehicles made in the United States or Canada.20 The impact of these factors on U.S. and Mexican motor vehicle manufacturing exports is reflected in Table 1.

In the absence of NAFTA, it is possible that vehicles assembled in North America would potentially use more Asian- and European-produced parts. For example, of the vehicle engines imported into the United States in 2015, about 60% originated in Mexico or Canada, but engines were also imported from Japan (11%), Germany (nearly 6%), and South Korea (more than 5%). Similar competition exists for transmissions, power trains, electric and electronic equipment, steering and suspension parts, brake systems, and vehicle lighting equipment.21 U.S. tariffs on auto parts imports from most countries with large automotive industries are about 1.7%, compared to zero in NAFTA, so favorable tariff treatment alone does not generally provide a large incentive to produce parts in Mexico for the U.S. market.22

Table 1. Total Per Vehicle Export Cost Advantages

Based on Generic $25,000 Vehicle Produced in Mexico for U.S. or European Markets

|

Cost Advantages |

Difference Between U.S. and Mexican Production for Vehicle Sold in the United States |

Difference Between U.S. and Mexican Production for Vehicle Sold in Europe |

|

Assembly plant labor |

$600 less in Mexico |

|

|

Parts |

$1,500 less in Mexicoa |

|

|

Transportation to the market |

$900 more to ship a vehicle from Mexico to the United States than to ship a U.S.-made vehicle internally |

$300 more to ship a vehicle from Mexico to EU than to ship a vehicle from the United States to Europe |

|

FTA tariff advantages |

No tariff when shipped within NAFTA area |

EU tariff of $2,500 on a U.S.-made vehicle, but no tariff on a Mexican vehicleb |

|

Total cost advantage |

$1,200 less costly to deliver Mexican-made vehicle than U.S.-made vehicle for final sale in the United States |

$4,300 less costly to deliver Mexican-made vehicle than U.S.-made vehicle for final sale in Europe |

Source: CRS, based on conversation with the author, Bernard Swiecki, The Growing Role of Mexico in the North American Automotive Industry (Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Automotive Research, 2016), p. 46.

a. According to author Bernard Swiecki, Mexican components such as engines and transmissions produced in Mexico are often less expensive than their U.S. counterparts because of lower Mexican labor costs.

b. Mexico has a free trade agreement with the European Union; the EU tariff on imported motor vehicles is 10%.

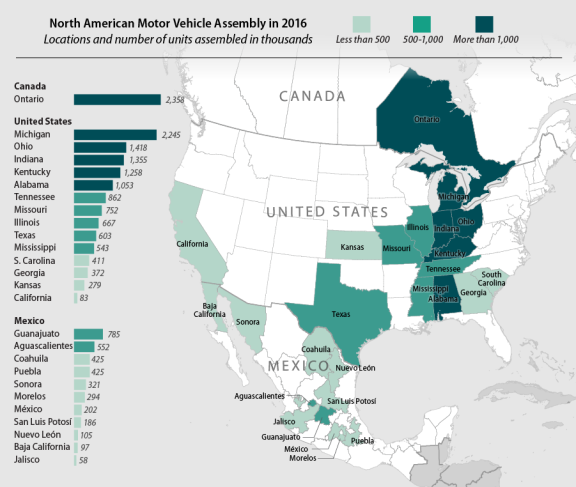

Motor vehicle assembly plants are found in 14 U.S. states; Canada's province of Ontario; and in 11 Mexican states (Figure 6), showing the concentrated north-south corridor in the United States from Mississippi and Alabama north to Michigan that is often called "automobile alley." Motor vehicle parts manufacturing plants, not included in the map, are located in nearly every state.

Motor Vehicle and Parts Trade

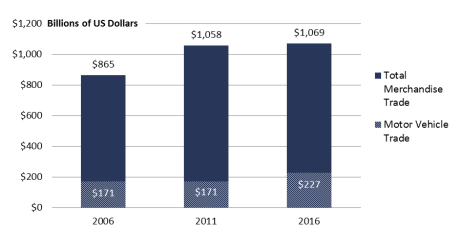

Motor vehicle and parts trade accounted for more than 20% of U.S. merchandise trade with other NAFTA signatories in 2016, slightly more than the shares in 2006 and 2007 before the recession (Figure 7).23

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, "Global Patterns of Merchandise Trade," interactive table April 12, 2017, http://tse.export.gov/TSE/TSEHome.aspx. |

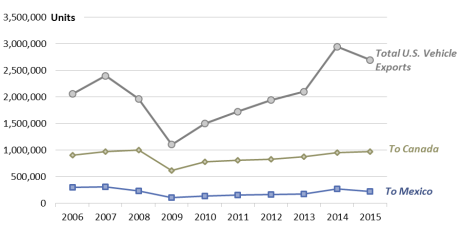

The United States exports more than 2 million motor vehicles a year; Canada and Mexico are the two largest markets for those vehicles (Figure 8).24

|

|

Source: Ward's Datasheets, U.S. Vehicle Exports by Country of Destination, 1990-2015. |

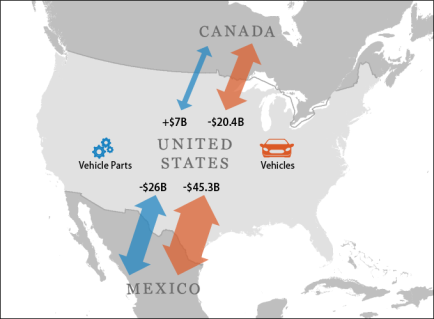

The United States has trade deficits in assembled vehicles with both Canada and Mexico (Figure 9). In 2016, the United States trade balance on vehicle trade with Canada was -$20.4 billion, and with Mexico, -$45.3 billion. Similarly, the United States imported more vehicle parts from Mexico than it exported, resulting in a $26 billion deficit in 2016. Only in U.S. motor vehicle parts trade with Canada did the United States record a surplus ($7 billion) in 2016. The vehicle parts exported from the United States to Canada (and Mexico) often come back to the United States in finished motor vehicles.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, "Global Patterns of Merchandise Trade," interactive table, April 12, 2017. |

Official trade statistics such as those showing the motor vehicle and parts trade balance include both intermediate inputs and final products. In effect, gross exports double count the value of intermediate goods that cross international borders more than once. This is of special relevance in the motor vehicle industry: a vehicle assembled in the United States has more than 10,000 parts that come from multiple producers in different countries and may travel back and forth across borders several times. One company producing seats for motor vehicles, for example, incorporates components from four different U.S. states and four Mexican locations into its products, with final assembly in the Midwest.25

Because of the complexities of modern supply chains, economists studying manufacturing tend to examine value added rather than trade flows. An industry's value added is an estimation of the difference between its sales and its purchases of components and other inputs.

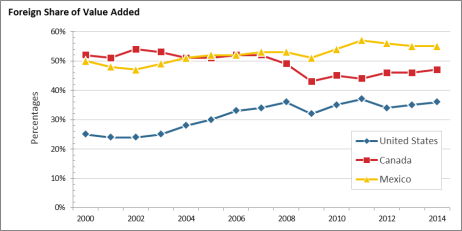

Mexico uses relatively more foreign content in its automotive industry than Canada and the United States: 55% of the value added of Mexican automotive exports came from foreign sources in 2014 (Figure 10). In contrast, the United States had an import intensity of 36%, while Canada was an intermediate 47%. This indicates that U.S. motor vehicle manufacturing retains a large base of U.S. component and assembly operations that has not been displaced by imports. Foreign value added in U.S. motor vehicle manufacturing rose significantly between 2002 and 2008, due in part to increasing flows of parts and components from Mexico and China, but the share of foreign content has stabilized since 2008. In Mexico, however, the share of foreign value added rose through at least 2011. This may be due to new investments in assembly plants that are using imported engines and other components.

|

|

Source: World Input-Output Database. |

Rules of Origin

An important objective of any trade agreement is to ensure that preferential treatment confers primarily to products of signatory countries. A second goal is to limit the negative impact of the agreement on import-sensitive domestic industries.26 Thus, agreements such as NAFTA include rules of origin to make certain that transshipment and light processing of goods largely produced in non-NAFTA countries—such as simple assembly or repackaging—are not used to circumvent higher duties.27 Determining the country of origin is fairly straightforward when a product is "wholly obtained" from, or manufactured in, only one country. However, when a finished product's component parts are manufactured in many countries, determining origin can be a complex process.28

Rules-of-origin requirements differ in each trade agreement because they are individually negotiated among the parties to the agreement. For importers to benefit from a trade agreement, they must demonstrate that their imports meet the respective rules-of-origin criteria.

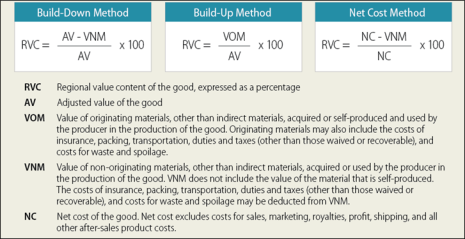

In NAFTA, the rules of origin affecting motor vehicles and parts are established by a method intended to ensure that a certain percentage of the value of a manufactured product (as determined by the cost of inputs, labor, and other direct costs of processing operations) originates in the NAFTA region. This regional value content (RVC) test involves specific equations to determine the value of originating materials, the adjusted value of the product, the value of non-originating materials,29 and other costs, such as processing operations and shipping (Figure 11).

In U.S. trade agreements, including NAFTA, three alternative methods are often used to calculate RVC in automotive products. Trade agreements often give manufacturers and importers more than one option for calculating the RVC, because one method of calculation may be more beneficial than the other for particular companies or industries. The three types of RVC calculations are the following:

- "Build-Down" Method: determines the regional value content by subtracting the value of the non-originating merchandise from the adjusted value of the finished product. The adjusted value includes all costs, profit, general expenses, parts and materials, labor, shipping, marketing, and packing. Since the build-down method allows manufacturers to count all the costs involved in building and marketing the final automobile or the component, a higher percentage (55%) is associated with this calculation in comparison to the other two allowable methods of calculating regional value content.

- "Build-Up" Method: starts with the value of originating materials. The value of NAFTA inputs is added together, and if their total value exceeds 35% of the adjusted value of the vehicle or the component, the product would qualify for the benefits of the agreement. The build-up method is included in trade agreements principally to benefit manufacturers of exports other than automobiles.

- "Net Cost" Method: captures only the costs involved in manufacturing, including factory labor, materials, and direct overhead. Other costs, such as sales promotion, marketing, royalties, and profit, are excluded from the calculation.30 The use of a small, easily identifiable set of input costs is thought to make the net cost method easier to use in calculating RVC.31 As the net cost method excludes selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs, profits, expenses, royalties, and promotional costs, its 35% RVC requirement is approximately equivalent to the 55% RVC requirement under the build-down method described above.32

|

|

Source: CRS, using rules-of-origin chapters in various U.S. free trade agreements. |

NAFTA Motor Vehicle Rules of Origin Requirements

The use of an RVC test to determine the origin of motor vehicles and parts under NAFTA was intended to accommodate the global sourcing strategies of vehicle manufacturers by creating incentives for them to source from within the NAFTA region. However, it is possible that the savings on tariffs from sourcing within the NAFTA region may not provide sufficient inducement to alter an already established supply chain. The U.S. tariff rate for imports of passenger cars from most countries is 2.5% of the value of the import, and avoiding this relatively low tariff alone would be unlikely to prompt manufacturers to build cars in the NAFTA region. The substantially higher U.S. light truck tariff at 25%, however, results in significant savings for manufacturers that build trucks in the NAFTA region to serve the U.S. market. This high tariff on imported trucks is possibly one reason why nearly all pick-up trucks sold in the United States are manufactured in North America.

U.S. free trade agreements have had a range of rules of origin (Table 2). NAFTA has the highest RVC requirement for automotive products, at 62.5% (meaning that the majority of the parts in the vehicle have to originate in the NAFTA region to receive the tariff benefit).33 This reflects the fact that the North American auto market was already highly integrated at the time of the negotiation of NAFTA. RVC rules in other trade agreements vary by percentage from 30% to 50%. The 1989 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement considered a vehicle to be domestic if it had at least 50% U.S. or Canadian content.

Since tariff rates on motor vehicles tend to be higher in the markets of U.S. trade partners than in the United States, tariff savings in the foreign market could provide an incentive for vehicle manufacturers in the United States to meet preferential rules-of-origin requirements. For example, tariffs for automobiles in Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement trading partners can be as high as 20%.34 This underscores the asymmetrical benefits that can accrue to manufacturers in the United States if tariffs are eliminated through a free trade agreement.

|

Free Trade Agreement |

Entry into Force |

Motor Vehicle Product Rules of Origin to Obtain FTA Benefits |

|

Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUFTA) |

1989 |

At least 50% domestic content requirement. |

|

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) |

1994 |

Regional value content (RVC) of at least 62.5% using the net cost requirement for passenger automobiles, light trucks, and their engines and transmissions; for other vehicles and auto parts, the threshold is 60%. |

|

U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement |

2004 |

RVC of not less than 30% when the build-up method is used, or 50% when the build-down method is used. Auto manufacturers can elect which method to use. |

|

U.S.-Singapore Free Trade Agreement |

2004 |

RVC of not less than 30% based on the build-up method for automotive products. |

|

U.S.-Australia Free Trade Agreement |

2005 |

RVC of not less than 50% under the net cost method for automotive products. |

|

Peru Trade Promotion Agreement |

2009 |

RVC of not less than 35% based on the net cost method. |

|

Dominican Republic – Central America (CAFTA-DR) Free Trade Agreement (Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic) |

Signed 2004; entered into force with individual countries from 2006 through 2009 |

Rules of Origin were largely modeled upon NAFTA and the U.S.-Chile FTA; include RVC of not less than 35% under net cost; not less than 35% under build-up; or not less than 50% under build-down. Auto manufacturers can elect which method to use. |

|

U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement |

2012 |

One of three RVC tests can be used: not less than 55% under build-down; not less than 35% under build-up; and not less than 35% under the net cost method. Motor vehicle manufacturers can elect which method to use. |

|

U.S.-Panama Trade Promotion Agreement |

2012 |

One of three RVC tests can be used: not less than 50% under build-down; not less than 35% under build-up; and not less than 35% under the net cost method. Motor vehicle manufacturers can elect which method to use. |

|

U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement |

2012 |

RVC of not less than 35% under the net cost method. |

|

Trans-Pacific Partnership |

United States withdrew in 2017 |

RVC of not less than 45% under the net cost method; not less than 55% under the build-down method. Motor vehicle manufacturers can elect which method to use. For a limited set of auto parts, RVC may partially be met if certain operations are completed in the region (see notes below). |

Source: Compiled by CRS based on a review of the regional value content (RVC) requirements for motor vehicle products in selected free trade agreements. U.S. free trade agreements with Israel, Jordan, Morocco, and Oman do not include motor vehicle-specific content requirements.

Notes: Motor vehicle products are mainly covered in Section 87 of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS). Passenger cars are covered by HTS 8703 (motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of persons), and light trucks are found in HTS 8704 (motor vehicles for the transport of goods). Other motor vehicle products covered in this section of the HTS include 8707 (bodies for motor vehicles) and 8708 (parts and accessories for motor vehicles).

Trans-Pacific Partnership, Annex 3-D, Appendix 1, "Provisions Related to the Product-Specific Rules of Origin for Certain Vehicles and Parts of Vehicles," provides that a limited set of parts used in the production of motor vehicles may be considered originating or count toward the RVC of the finished vehicle: (1) if the part meets the applicable requirements for the material under the Annex, or (2) if one or more of certain operations used in the manufacture of the part are performed in one or more of the parties to the agreement. These parts include tempered or laminated safety glass, motor vehicle bodies, bumpers, body stampings and door assemblies, and drive-axles. The manufacturing operations that may be performed on these items include complex assembly, complex welding, die or other casting, extrusion, forging, heat treating (including glass or metal tempering), machining, metal forming, moulding, and stamping. For certain other auto parts, including engines, chassis, bumpers, seat belts, and brakes, these manufacturing operations may count toward RVC requirements up to a certain threshold, generally 5%-10%.

NAFTA Renegotiation Process

A renegotiation of NAFTA is likely to be considered by Congress under Trade Promotion Authority. On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Mexico and Canada to renegotiate or modernize the free trade agreement as required by TPA.35 NAFTA provides, "The Parties may agree on any modification of or addition to this Agreement. When so agreed, and approved in accordance with the applicable legal procedures of each party, a modification or addition shall constitute an integral part of the agreement."36

Under TPA, the President must consult with Congress before giving the required 90-day notice of his intention to start negotiations.37 The Trump Administration's consultations included meetings between U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and members of the House Ways and Means Committee and Senate Finance Committee and with members of the House and Senate Advisory Groups on Negotiations.38 USTR received more than 12,000 public comments on NAFTA renegotiation.39

On July 17, 2017, USTR published a summary of the Trump Administration's specific objectives with respect to the negotiations, and later announced that negotiations with Mexico and Canada would start on August 16, 2017.40

In order to use the expedited procedures of TPA, the President must notify and consult with Congress before initiating and during negotiations, and adhere to several reporting requirements following the conclusion of any negotiations resulting in an agreement. The President must conduct the negotiations based on the negotiating objectives set forth by Congress in the 2015 TPA authority. If the President adheres to these and other requirements, then implementing legislation from the resulting agreement can be considered under expedited procedures, including guaranteed time-limited consideration, no amendments, and an up-or-down vote.

Implementation of a renegotiated agreement in domestic law would likely take one of two forms: (1) a renegotiated agreement that would require changes to U.S. law or (2) changes to the agreement that could be made effective by presidential proclamation.41 If renegotiation is expected to require changes to U.S. law, the President likely would seek expedited treatment of the implementing legislation under TPA.42 On the other hand, the President could proclaim (i.e., declare) some modifications to NAFTA pursuant to existing statutory authority.43 These could include certain tariff modifications, or changes to basic and specific rules of origin, and some customs provisions.

Certain consultation and layover requirements are applicable to proclamations concerning rules of origin changes for autos and auto parts:

- modifications to specific tariff-shift rules of origin (Annex 401);

- automotive tracing requirements for specific parts (Annexes 403.1, 403.2);

- regional value-content provisions for certain Canadian autos (Annex 403.3); and

- modification of rules of origin definitions.44

Renegotiation of other provisions of NAFTA requiring changes to U.S. law likely would need implementing legislation. Such legislation could be considered under TPA. TPA currently is in effect until July 1, 2021, provided that Congress does not pass an extension disapproval resolution in the 60 days prior to July 1, 2018.

NAFTA Motor Vehicle Policy Recommendations

The federal government's senior trade advisory panel, the Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations (ACTPN), issued its report and recommendations for modernizing NAFTA on June 28, 2017, stating that "it is time to bring NAFTA into the 21st Century and to turn it into a high standards agreement in accordance with the negotiating objectives of the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)." ACTPN did not make specific recommendations with regard to motor vehicle trade, but its report does address some of the specific issues raised by motor vehicle industry and union organizations. For example, with regard to rules of origin, the majority of ACTPN members—but not its labor union members—

urge caution in making changes to the rules of origin to ensure that they do not disrupt efficient supply chains and raise production costs, undercut U.S. competitiveness, and potentially backfire and lead to job losses in the U.S. and less sourcing because companies will import components and pay the Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariff.

The ACTPN report also discusses general recommendations for other policy issues of interest to the motor vehicle industry and unions, including government procurement, customs procedures, environmental and labor standards, worker rights, currency manipulation, and investor state dispute settlement.

Each of these issues was raised when the USTR held a series of public hearings seeking recommendations on NAFTA negotiating objectives from June 27 to June 29, 2017, taking testimony from a broad range of witnesses. The USTR hearings were conducted by the NAFTA Modernization panel45 and included officials who sit on the Trade Policy Staff Committee,46 including representatives from USTR and the Departments of Commerce, Treasury, State, and Agriculture.

The industry representatives—Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, the Association of Global Automakers, Motor and Equipment Manufacturers Association (MEMA), the Auto Care Association, and the American Automotive Policy Council (AAPC)—spoke about the evolution of the current supply chain and the benefits they see it has brought to the North American vehicle market. They advocate changes to enhance the agreement and support the current NAFTA rules of origin, which they say strike the right supply chain balance, promote exports from North America, and reduce costs. The motor vehicle associations argued for NAFTA modernization, including changes that would

- update customs procedures, including e-commerce, to reduce border delays;

- expand intellectual property protection;

- remove technical barriers to trade by improving regulatory cooperation on future vehicle standards and recognize current U.S. Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards so U.S.-certified vehicles will be accepted across the region;

- align data protection and privacy laws so data can be exchanged across borders more easily; and

- update labor and environmental provisions consistent with more recent free trade agreements.

In addition, AAPC called for inclusion of enforceable provisions to deter currency manipulation47 and elimination of investor-state dispute settlement provisions.48

The United Auto Workers union (UAW), testifying separately on June 29, argued that a new agreement is needed to provide more benefits to workers in all three signatory countries. The UAW called NAFTA a "failure" and said it supports renegotiation in order to reverse the U.S. deficit in motor vehicle trade and raise worker wages. The UAW also supports new provisions that would

- curb currency manipulation;

- add labor and environmental standards with enforcement mechanisms;49

- bar investor-state dispute settlement provisions;

- eliminate the federal procurement chapter of NAFTA;

- ensure that Buy America provisions are retained; and

- strengthen the rules of origin to prevent non-NAFTA countries from benefiting from the agreement. The UAW also supports retention of the current documentation and product tracing requirements that establish the origin of motor vehicle parts.

Links to statements submitted by the industry and labor union representatives to USTR in June 2017 are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Motor Vehicle Industry and Union Comments

on NAFTA Negotiating Objectives

Submissions to USTR

|

Organization |

Links to Comments |

|

Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers |

|

|

Association of Global Automakers |

|

|

Motor and Equipment Manufacturers Association |

|

|

Auto Care Association |

|

|

American Automotive Policy Council |

|

|

UAW |

Source: "Requests for Comments: Negotiating Objectives Regarding Modernization of North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico," https://www.regulations.gov/docket?D=USTR-2017-0006.

Note: The industry and union comments were submitted in mid-June before the USTR held its NAFTA hearings on June 27-29, 2017.

Trump Administration's NAFTA Renegotiation Objectives

The Trump Administration's announced objectives do not include specific motor vehicle industry goals, unlike some of the specific objectives for agricultural goods and textiles and apparel.50 However, its broad objectives are consistent with a number of recommendations cited by speakers at USTR's late June 2017 hearings, including

- maintaining existing duty-free market access for industrial goods and removing nontariff barriers;

- promoting greater regulatory compatibility and cooperation and removing technical barriers to trade;

- updating customs procedures;

- strengthening the rules of origin to "ensure that the benefits of NAFTA go to products genuinely made in the United States and North America" and ensuring that such rules "incentivize the sourcing of goods and materials from the United States and North America";51

- preventing the establishment of restrictions on cross-border data flows;

- improving intellectual property protection;

- bringing labor and environmental provisions into the main NAFTA agreement, instead of in side agreements, while expanding their scope; and

- developing a mechanism "to ensure that the NAFTA countries avoid manipulating exchange rates in order to prevent effective balance of payments adjustment or to gain an unfair competitive advantage."52