Background

Many governments hold that environmental degradation and climate change pose international and trans-boundary risks to human populations, economies, and ecosystems, as well as potential risks to national security. To confront these challenges, governments have negotiated various international agreements to protect the environment, reduce pollution, conserve natural resources, and promote sustainable growth. While some agreements call upon industrialized countries to take the lead in addressing these issues, many recognize that efforts by wealthier countries alone are unlikely to be sufficient without similar measures being taken in lower-income countries. However, lower-income countries, which tend to prioritize poverty reduction and economic growth, may not have the financial resources, technological expertise, or institutional capacity to deploy environmentally protective measures on their own. Therefore, international financial assistance has been a principal method for governments to support actions on global environmental problems in lower-income countries.

U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 1992)1 was the first international treaty to acknowledge and address human-driven climate change. The United States ratified the treaty in 1992 (U.S. Treaty Number: 102-38). Among the obligations outlined in Article 4, higher-income Parties (i.e., those listed in Annex II of the Convention, which were members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in 1992) committed themselves to seek to provide unspecified amounts of "new and additional financial resources to meet the agreed full costs incurred by developing country Parties in complying with their obligations" under the Convention. Further, "the implementation of these commitments shall take into account the need for adequacy and predictability in the flow of funds and the importance of appropriate burden sharing among the developed country Parties."2

Over the past several decades, the United States has delivered financial and technical assistance for climate change activities in the developing world through a variety of bilateral and multilateral programs. U.S.-sponsored bilateral assistance has come through programs at the U.S. Agency for International Development, the U.S. Department of State, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, the Export-Import Bank, and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, among others. U.S.-sponsored multilateral assistance has come through contributions by the U.S. Departments of State and the Treasury to environmental funds at various international financial institutions and organizations such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF),3 the Green Climate Fund (GCF),4 the U.N. Development Program, the U.N. Environment Program, the UNFCCC's Special Climate Change Fund and Least Developed Country Fund, the World Bank's Climate Investment Funds (including the Clean Technology Fund and the Strategic Climate Fund),5 and the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, among others.

Global Environment Facility

To facilitate the provision of climate finance under the UNFCCC, the Convention establishes a financial mechanism to provide funds to developing country Parties. Article 11 of the Convention states that the operation of the financial mechanism can be entrusted to one or more existing international entities. The GEF was established in 1991 and subsequently became an official operating entity of the financial mechanism of several international environmental agreements, including the UNFCCC.6 The relationship between the UNFCCC and the GEF is outlined in a memorandum of understanding contained in UNFCCC decisions 12/CP.2 and 12/CP.3.7

The George H. W. Bush Administration supported the establishment of the GEF in 1991. The United States has made commitments to all six GEF resource replenishments, including $430 million in 1994, $430 million in 1998, $430 million in 2002, $320 million in 2006, $575 million in 2010, and $546 million in 2014, for a total of $2.732 billion. U.S. commitments correspond to about 13% of GEF's total during the history of the institution. U.S. disbursements to the GEF since 1994 have totaled approximately $2.2 billion.

The Copenhagen Accord and the Cancun Agreement

In 2009, the Conference of Parties (COP)8 to the UNFCCC in Copenhagen, Denmark, took note of a non-legal political document called the Copenhagen Accord.9 The following year, in Cancun, Mexico, the COP officially adopted many of the accord's elements in the Cancun Agreements,10 including several quantified financial arrangements:

- Fast start financing. The agreement puts forth a collective commitment by developed country Parties (not specified in the text) to seek to provide new and additional resources approaching $30 billion for the period 2010-2012 to address the climate finance needs of developing countries (1/CP.16§95).

- 2020 pledge. The agreement takes note of the pledge by developed country Parties (not specified in the text) to achieve a goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion per year by 2020 to address the climate finance needs of developing countries (1/CP.16§98).

- Sources. The agreement states that "funds provided to developing country Parties may come from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources" (1/CP.16§99).

The Paris Agreement

In 2015, the COP to the UNFCCC in Paris, France, adopted the Paris Agreement (PA).11 The PA builds upon the Convention and—for the first time—brings all nations into a common framework to undertake efforts to combat climate change, adapt to its effects, and support developing countries in their efforts.

Article 9 of the PA reiterates the obligation in the Convention for developed country Parties, including the United States, to seek to mobilize financial support to assist developing country Parties with climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts (Article 9.1). Also, for the first time under the UNFCCC, the PA encourages all Parties to provide financial support voluntarily, regardless of their economic standing (Article 9.2). The agreement states that developed country Parties should take the lead in mobilizing climate finance and that the mobilized resources may come from a wide variety of sources. It adds that the mobilization of climate finance "should represent a progression beyond previous efforts" (Article 9.3).

The COP Decision to carry out the PA (1/CP.21)12 uses exhortatory language to restate the collective pledge by developed countries of $100 billion annually by 2020 and calls for continuing this collective mobilization through 2025. In addition, the Parties agree to set, prior to their 2025 meeting, a new collective quantified goal for mobilizing financial resources of not less than $100 billion annually to assist developing country Parties.

On June 1, 2017, President Donald Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the PA. Under the provisions of the PA, this could not be completed before November 4, 2020. Other CRS products examine the legal13 and policy14 implications of this announcement.

The Green Climate Fund

The 2009 Copenhagen Accord opened the way for the GCF15 to be designated as an operating entity of the financial mechanism of the UNFCCC (similar to the GEF). Parties agreed to the design of the GCF during the 2011 COP in Durban, South Africa. The GCF is intended to operate at arm's length from the UNFCCC, with an independent board, trustee, and secretariat. The GCF is to be "accountable to and function under the guidance of the Conference of Parties"16 (i.e., similar in legal structure to the GEF), as opposed to "accountable to and function under the guidance and authority of the Conference of Parties" (i.e., similar in legal structure to the Adaptation Fund).

The purpose of the fund is to assist developing countries in their efforts to combat climate change through the provision of grants and other concessional financing.17 The GCF is capitalized by "financial inputs from developed country Parties to the Convention" and "may also receive financial inputs from a variety of other sources, public and private, including alternative sources."18

The GCF became operational in the summer of 2014. Parties have pledged approximately $10.3 billion for the initial capitalization of the fund. The Barack Obama Administration pledged $3 billion over four years in November 2014. The U.S. Department of State made two contributions of $500 million to the GCF on March 8, 2016, and on January 17, 2017. The funds were obligated with FY2016 budget authority from the agency's Economic Support Fund—an account under the function 150 and Other International Programs budget. The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (P.L. 87-195; part II, Chapter 4), provides the President authority to use the Economic Support Fund "to furnish assistance to countries and organizations, on such terms and conditions as he may determine, in order to promote economic or political stability." No contribution has been made to the GCF with FY2017 budget authority.

The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget request,19 released on May 23, 2017, proposes to "eliminate U.S. funding for the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in FY2018, in alignment with President Trump's promise to cease payments to the United Nations' climate change programs." President Trump has denounced the GCF, stating that the fund would "redistribute wealth out of the United States" and that "billions of dollars that ought to be invested right here in America will be sent to the very countries that have taken our factories and our jobs away from us."20 Nevertheless, the U.S. disbursement of $1 billion to the GCF under the Obama Administration ensures that the United States remains a member of the GCF board through the initial phase of capitalization. The Trump Administration has not stated whether it will retain its board membership. A State Department official reportedly said that "future U.S. engagement with the GCF will be decided as part of the wider internal process to further develop our policy on climate change."21

The relationship of the GCF to the United States' other climate finance commitments can be outlined as follows:

- UNFCCC 2020 pledges. The collective pledge by developed country Parties to the goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion per year by 2020 is not tied directly to the GCF, nor is it tied directly to public funding. The Cancun negotiating text makes clear that "funds provided to developing country Parties may come from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources."22 The GCF is one of many possible public and multilateral sources. While any financing that is channeled through the GCF would likely be considered a part of the $100 billion goal, the entirety of the $100 billion goal is not expected to be provided solely by the GCF, and no estimation of the GCF's presumed share has been agreed to officially. Many Parties have stated that development bank instruments, carbon markets, and—especially—private capital would be critical to mobilizing assistance at the level pledged.

- Bilateral aid. The GCF would not interfere with bilateral climate change assistance to developing countries. The GCF would be another multilateral mechanism for climate change assistance that would exist alongside bilateral activities, much the way that the GEF currently does and the World Bank's Climate Investment Funds did. U.S. allocations among bilateral and multilateral assistance channels would continue through authorized congressional appropriations.

- Other multilateral aid. The GCF board has been tasked with determining the complementarity of the GCF with respect to other U.N. multilateral mechanisms. Thus, future negotiations may alter the multilateral choices provided by the UNFCCC. Presumably, choices would remain available to donor countries. U.S. allocations among multilateral assistance channels would remain based on congressional guidance and would continue through authorized congressional appropriations.

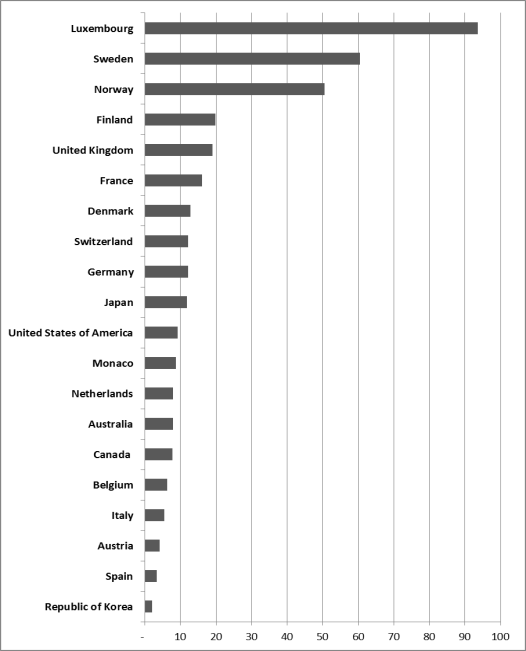

Table 1 lists donor Parties to the GCF, their pledges, and disbursements (in U.S. dollar equivalents as calculated by the GCF) as of June 2, 2017. Figure 1 presents the top 20 donor countries in order of pledges per capita.23

Possible Implications of Withdrawal

Withdrawal from the PA, including its financial commitments—and, more broadly, the cessation of financial assistance to "United Nations' climate change programs"—may have both positive and negative implications for the United States, depending on a variety of uncertain factors. Possible benefits might include:

- Fiscal savings. Under the Obama Administration, the U.S. government provided about $1 billion annually for climate finance in the developing world. These funds accounted for approximately 3% of the U.S. foreign operations budget. Some observers have criticized national and international institutions that dispense financial assistance for bureaucratic inefficiencies, lack of transparency, and misuse of funds. Further, they question the overall effectiveness of international financial assistance in spurring economic development and reform in lower-income countries and, more specifically, in mitigating climate change and its risks. Reductions in international financial assistance could make these funds available for other priorities.

- Commercial interests. Climate finance is intended to assist developing countries in reducing their demand for GHG-intensive fuels and technologies. Reductions in international financial assistance could help sustain markets for these products, including U.S. exports.

- U.S. sovereignty. Some stakeholders contend that U.S. withdrawal from the commitments under the PA helps redefine U.S. international relations—highlighting issues of sovereignty, national interest, and internal control of domestic economics, legal systems, and political values and structures.

Possible repercussions might include:

- Investment efficiencies. Some economists and other stakeholders theorize that the future costs of responding to tomorrow's climate-related catastrophes may be significantly higher than the costs of preventing them today. Further, they suggest that economic efficiencies may be found more readily in developing countries because the cost of adopting new technologies is usually less than the cost of retrofitting existing ones. Thus, reductions in international financial assistance could theoretically produce greater economic inefficiencies. Additionally, some have argued that the provision of climate finance—specifically adaptation assistance—may support the humanitarian and security interests of the United States. For example, the U.S. Central Command has reported that the impacts of global climate change may worsen poverty, social tensions, environmental degradation, and political institutions across the developing world.24 Reductions in international financial assistance could increase the susceptibility of lower-income countries to these threats—to the detriment of both the country and the interests of the United States.

- Commercial interests. Climate finance in developing countries may benefit U.S. businesses that support low-emissions technologies. Reductions in international financial assistance could reduce demand and restrict global economic activity for these goods and services, including U.S. exports.

- International leadership. Financial commitments under the PA—and foreign assistance in general—are a means through which the United States may increase its global environmental leadership. Through such leadership, the United States may influence and set important international economic and environmental policies, practices, and standards. Without it, some observers have argued that the United States may cede such influence to other nations and non-state actors.

While a withdrawal from the PA would release the United States from specific obligations under the PA, it would not release the United States from the general commitments under the UNFCCC to provide "new and additional financial resources to meet the agreed full costs incurred by developing country Parties in complying with their obligations" or the collective pledge by developed country Parties to achieve "a goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion per year by 2020." The Administration has not made a statement regarding its intentions under these prior obligations.

In sum, the influence of the Trump Administration's announced withdrawal from the PA and the announced cessation of U.S. payments to United Nations' climate change programs would rely on assumptions regarding the efficiencies of these programs and the effects of the collective assistance provided by other nations, regional governments, states, cities, and the private sector. Some analysis suggests the impacts could be minimal if other public and private investments compensate for the lack of U.S. assistance. However, the decision could erode international efforts to help developing countries confront climate change.

Ultimately, U.S. contributions to developing countries for climate change-related activities are determined by the U.S. Congress. Congress is responsible for several activities in regard to this assistance, including (1) authorizing federal agency programs, (2) authorizing and enacting periodic appropriations for these programs and multilateral fund contributions, (3) providing guidance to the agencies, and (4) overseeing U.S. interests in the programs. Congressional committees of jurisdiction for international climate change assistance include the U.S. House of Representatives Committees on Foreign Affairs, Financial Services, and Appropriations and the U.S. Senate Committees on Foreign Relations and Appropriations.

Table 1. Status of Pledges for GCF's Initial Resource Mobilization

(In millions of U.S. $ equivalent)

|

Donor Country |

Pledged |

Disbursed |

Pledged Per Capita |

|

Australia |

187.6 |

122.17 |

7.92 |

|

Austria |

34.8 |

18.74 |

4.09 |

|

Belgium |

66.9 |

66.90 |

6.22 |

|

Bulgaria |

0.1 |

0.10 |

0.02 |

|

Canada (Grant) |

155.1 |

155.10 |

7.80 |

|

Canada (Loan) |

101.6 |

- |

- |

|

Canada (Cushion) |

20.3 |

- |

- |

|

Chile |

0.3 |

0.30 |

0.02 |

|

Colombia |

0.3 |

0.30 |

0.12 |

|

Cyprus |

0.50 |

- |

0.40 |

|

Czech Republic |

5.30 |

5.30 |

0.50 |

|

Denmark |

71.80 |

44.88 |

12.82 |

|

Estonia |

1.30 |

1.30 |

1.00 |

|

Finland |

46.40 |

46.40 |

19.82 |

|

France (Grant) |

577.90 |

330.95 |

16.03 |

|

France (Loan) |

381.30 |

- |

- |

|

France (Cushion) |

76.30 |

- |

- |

|

Germany |

1,003.30 |

501.65 |

12.13 |

|

Hungary |

4.30 |

4.30 |

0.40 |

|

Iceland |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

|

Indonesia |

0.30 |

0.20 |

>0.01 |

|

Ireland |

2.70 |

2.70 |

0.59 |

|

Italy |

267.50 |

133.75 |

5.47 |

|

Japan |

1,500.00 |

750.00 |

11.81 |

|

Latvia |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.23 |

|

Liechtenstein |

0.10 |

0.10 |

1.50 |

|

Lithuania |

0.10 |

0.10 |

0.04 |

|

Luxembourg |

33.40 |

26.72 |

93.60 |

|

Malta |

0.20 |

0.20 |

0.20 |

|

Mexico |

10.00 |

10.00 |

0.08 |

|

Monaco |

1.30 |

1.30 |

8.80 |

|

Netherlands |

133.80 |

45.49 |

7.96 |

|

New Zealand |

2.60 |

2.60 |

0.56 |

|

Norway |

257.90 |

128.95 |

50.56 |

|

Panama |

1.00 |

1.00 |

0.26 |

|

Poland |

0.10 |

0.10 |

>0.01 |

|

Portugal |

2.70 |

2.70 |

0.30 |

|

Republic of Korea |

100.00 |

36.70 |

2.02 |

|

Romania |

0.10 |

0.10 |

>0.01 |

|

Spain |

160.50 |

2.68 |

3.40 |

|

Sweden |

581.20 |

581.20 |

60.54 |

|

Switzerland |

100.00 |

100.00 |

12.20 |

|

United Kingdom |

1,211.00 |

675.64 |

19.07 |

|

United States of America |

3,000.00 |

1,000.00 |

9.30 |

Source: Green Climate Fund, "Status of Pledges for GCF's Initial Resource Mobilization (IRM)," as of June 2, 2017.

Notes: United States dollars equivalent (USD eq.) based on the reference exchange rates established for GCF's High-Level Pledging Conference (GCF/BM-2015/Inf.01). USD eq. is based on the foreign exchange rate as of May 31, 2017. Depending on the rate at the time of conversion, the USD eq. amount will fluctuate accordingly. GCF's initial resource mobilization period lasts from 2015 to 2018, and the fund accepts new pledges on an ongoing basis.