Introduction

The federal government provides elementary and secondary education and educational assistance to Indian1 children, either directly through federally funded schools or indirectly through educational assistance to public schools. The Bureau of Indian Education (BIE)2 in the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) oversees the federally funded BIE system of elementary and secondary schools. The BIE system is funded primarily by the BIE but also receives considerable funding from the U.S. Department of Education (ED). The public school systems of the states receive federal funding from ED, the BIE, and other federal agencies.

Federal provision of educational services and assistance to Indian children is based not on race/ethnicity but primarily on their membership in, eligibility for membership in, or familial relationship to members of Indian tribes, which are political entities. Federal Indian education programs are intended to serve Indian children who are members of, or, depending on the program, are at least second-degree descendants of members of, one of the 567 tribal entities recognized and eligible for funding and services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) by virtue of their status as Indian tribes.3 The federal government considers its Indian education programs to be based on its trust relationship with Indian tribes, a responsibility derived from federal statutes, treaties, court decisions, executive actions, and the Constitution (which assigns authority over federal-Indian relations to Congress).4 Despite this trust relationship, Indian education programs are discretionary and not an entitlement like Medicare.

Indian children, as enrollees in public education, are also eligible for the federal government's general programs of educational assistance, but such programs are not Indian education programs and will not be discussed in this report.

This report provides a brief history of federal Indian education programs, a discussion of students served by these programs, an overview of programs and their funding, and brief discussions of selected issues in Indian education.

Brief History of Federal Indian Education Activities

U.S. government concern with the education of Indians began with the Continental Congress, which in 1775 appropriated funds to pay expenses of 10 Indian students at Dartmouth College.5 Through the rest of the 18th century, the 19th century, and much of the 20th century, Congress's concern was for the civilization of the Indians, meaning their instruction in Euro-American agricultural methods, vocational skills, and habits, as well as in literacy, mathematics, and Christianity. The aim was to change Indians' cultural patterns into Euro-American ones—in a word, to assimilate them.6

From the Revolution until after the Civil War, the federal government provided for Indian education either by directly funding teachers or schools on a tribe-by-tribe basis pursuant to treaty provisions or by funding religious and other charitable groups to establish schools where they saw fit. The first Indian treaty providing for any form of education for a tribe—in this case, vocational—was in 1794.7 The first treaty providing for academic instruction for a tribe was in 1803.8 Altogether over 150 treaties with individual tribes provided for instructors, teachers, or schools, whether vocational, academic, or both, either permanently or for a limited period of time.9 The first U.S. statute authorizing appropriations to "promote civilization" among Indian tribes was the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act of 1793,10 but the Civilization Act of 1819 was the first authorization and appropriation specifically for instruction of Indian children near frontier settlements in reading, writing, and arithmetic.11 Civilization Act funds were expended through contracts with missionary and benevolent societies. Besides treaty schools and "mission" schools, some additional schools were initiated and funded directly by Indian tribes. The state of New York also operated schools for its Indian tribes. The total of such treaty, mission, tribal, and New York schools reached into the hundreds by the Civil War.12

After the Civil War, the U.S. government began to create a federal Indian school system, with schools not only funded but also constructed and operated by DOI's BIA with central policies and oversight.13 In 1869, the Board of Indian Commissioners—a federally appointed board that jointly controlled with DOI the disbursement of certain funds for Indians14—recommended the establishment of government schools and teachers.15 In 1870, Congress passed the first general appropriation for Indian schools not provided for under treaties.16 The initial appropriation was $100,000, but both the amount appropriated and the number of schools operated by the BIA rose swiftly thereafter.17 The BIA created both boarding and day schools, including off-reservation industrial boarding schools on the model of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (established in 1879).18 Most BIA students attended on- or off-reservation boarding schools.19 BIA schools were chiefly elementary and vocational schools.20

An organizational structure for BIA education began with a Medical and Education Division during 1873-1881, appointment of a superintendent of education in 1883, and creation of an education division in 1884.21 The education of Alaska Native children, however, along with that of other Alaskan children, was assigned in 1885 to DOI's Office of Education, not the BIA.22 Mission, tribal,23 and New York state schools continued to operate, and the proportion of school-age Indian children attending a BIA, mission, tribal, or New York school rose slowly.24

A major long-term shift in federal Indian education policy, from federal schools to public schools, began in FY1890-FY1891 when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, using his general authority in Indian affairs, contracted with a few local public school districts to educate nearby Indian children for whose schooling the BIA was responsible.25 After 1910, the BIA pushed to move Indian children to nearby public schools and to close BIA schools.26 Congress provided some appropriations to pay public schools for Indian students, although they were not always sufficient and moreover were not paid where state law entitled Indian students to public education.27

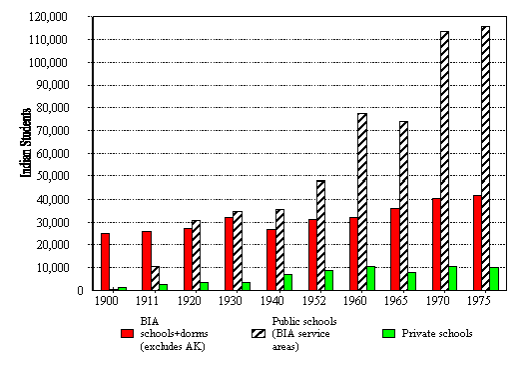

By 1920, more Indian students were in public schools than BIA schools.28 Figure 1 displays the changing number of Indian students in BIA, public, and other schools from 1900 to 1975. The shift to public schools accompanied the increase in the percentage of Indian youths attending any school, which rose from 40% in 1900 to 60% in 1930.29 Comparable data are no longer available.

In 1921, Congress passed the Snyder Act30 in order to authorize all programs the BIA was then carrying out. Most BIA programs at the time, including education, lacked authorizing legislation. The Snyder Act continues to provide broad and permanent authorization for federal Indian programs.

In 1934, to simplify the reimbursement of public schools for educating Indian students, Congress passed the Johnson-O'Malley (JOM) Act,31 authorizing the BIA to contract with the states, except Oklahoma, and the territories for the education of Indians (and other services to Indians).32

In the 1920s and 1930s, the BIA began expanding some of its own schools' grade levels to secondary education. Under the impetus of the Meriam Report and New Deal leadership, the BIA also began to shift its students toward its local day schools instead of its boarding schools, and, to some extent, to move its curriculum from solely Euro-American subjects to include Indian culture and vocational education.33 In addition in 1931, responsibility for Alaska Native education was transferred to the BIA.34

The first major non-DOI federal funding for Indian education in the 20th century began in 1953, when the Federal Assistance for Local Educational Agencies Affected by Federal Activities program,35 now known as Impact Aid, was amended to cover Indian children eligible for BIA schools.36 Impact Aid pays public school districts to help fund the education of children in "federally impacted areas." Further changes to the Impact Aid law in 1958 and the 1970s increased the funding that was allocated according to the number of children on Indian lands.37 Congressional appropriations for Impact Aid increased as the JOM funding decreased.

In 1966 Congress added further non-DOI funding for Indian education by amending the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965,38 the major act authorizing federal education aid to public school districts, to add set-asides for BIA schools to the program of grants to help educate students from low-income families; school library resources, textbook, and instructional materials; and supplementary educational centers and services.39

A congressional study of Indian education in 196940 that was highly critical of federal Indian education programs led to further expansion of federal non-DOI assistance for Indian education, embodied in the Indian Education Act of 1972, now known as ESEA Title VI.41 The Indian Education Act established the Office of Indian Education (OIE) within the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and authorized OIE to make grants to local educational agencies (LEAs) with Indian children.42 The OIE was the first organization outside of DOI (since DOI's birth in 1849) that was created expressly to oversee a federal Indian education program.

Federal Indian education policy also began to move toward greater Indian control of federal Indian education programs, in both BIA and public schools. In 1966, the BIA signed its first contract with an Indian group to operate a BIA school (the Rough Rock Demonstration School on the Navajo Reservation).43 In 1975, through enactment of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA),44 Congress authorized all Indian tribes and tribal organizations, such as tribal school boards, to contract to operate their BIA schools. Three years later, in Title XI, Part B, of the Education Amendments of 1978, Congress required the BIA "to facilitate Indian control of Indian affairs in all matters relating to education."45 This act created statutory standards and administrative and funding requirements for the BIA school system and separated control of BIA schools from BIA area and agency officers by creating a BIA Office of Indian Education Programs (OIEP) and assigning it supervision of all BIA education personnel.46 Ten years later, the Tribally Controlled Schools Act (TCSA) of 198847 authorized grants to tribes and tribal organizations to operate their BIA schools. These laws provide that grants and self-determination contracts be for the same amounts of funding as the BIA would have expended on operation of the same schools.48

Indian control in public schools received an initial boost from the 1972 Indian Education Act. The ESEA Title VI requires that public school districts applying for its grants prove adequate participation by Indian parents and tribal communities in program development, operation, and evaluation.49 The 1972 Indian Education Act also amended the Impact Aid program to mandate Indian parents' consultation in school programs funded by Impact Aid.50 In 1975, the ISDEAA added to the JOM a requirement that public school districts with JOM contracts have either a majority-Indian school board or an Indian parent committee that has approved the JOM program.51 Finally, the Improving America's Schools Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-382, Section 9112(b)) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA; P.L. 114-95) have expanded eligibility under the current ESEA Title VI formula grant program to Indian tribes; Indian organizations; Indian community-based organizations; and consortia of LEAs, Indian tribes, Indian organizations, and Indian community-based organizations.

Starting in the 1960s, the number of schools in the BIA school system began to shrink through administrative consolidation and congressional closures. For example, all BIA-funded schools in Alaska were transferred to the state of Alaska between 1966 and 1985, removing an estimated 120 schools from BIA responsibility.52 The number of BIA-funded schools and dormitories stood at 233 in 193053 and 277 in 1965,54 but fell to 227 in 1982 and to 180 in 1986 before rising to 185 by 1994;55 it currently stands at 183.56 Since the 1990s, Congress has limited both the number of BIA schools and the grade structure of the schools.57 The number of Indian students educated at BIA schools has numbered approximately 48,000 over the last 15 years.58 In 2006, the Secretary of the Interior separated the BIA education programs in the Office of Indian Education Programs from the rest of the BIA and placed them in a new Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) under the Assistant Secretary–Indian Affairs.59

Students Served by Federal Indian Education Programs

It is commonly estimated that BIE schools serve less than 10% of Indian students, public schools serve over 90%, and private schools serve 1% or less. These general percentages, however, are not certain. Data on Indian students come from differing programs and sources. Different federal Indian education programs serve different, though overlapping, sets of Indian students. Their student data also differ (and overlap). In addition, it is unlikely that every school or school district that enrolls at least one Indian student receives funding from a federal program designed to serve Indian students or funded based on numbers of Indian students.

Although different federal Indian education programs have different eligibility criteria, none of the eligibility criteria are based solely on race/ethnicity. Eligibility is based on the political status of the groups of which the students are members or descendants of members.

The BIE school system, for instance, serves students who are members of federally recognized Indian tribes or who are at least one-fourth degree Indian blood descendants of members of such tribes, and who reside on or near a federal Indian reservation or are eligible to attend a BIE off-reservation boarding school.60 Many Indian tribes allow less than one-fourth degree of tribal or Indian blood for membership, so many BIE Indian students have less than one-fourth Indian blood. Separately, the BIE's JOM program, according to its regulations, serves students in public schools who are at least one-fourth degree Indian blood and recognized by the BIA as eligible for BIA services.61

The ED ESEA Title VII-A programs, on the other hand, serve a broader set of students: (1) members of federally recognized tribes and their first and second degree descendants; (2) members of two types of nonfederally recognized tribes, state-recognized tribes and tribes whose federal recognition was terminated after 1940, and their first and second degree descendants; (3) members of an organized Indian group that received a grant under the ED Indian Education formula grant program as it was in effect before the passage of the Improving America's Schools Act of 1994;62 (4) Eskimos, Aleuts, or other Alaska Natives; and (5) individuals considered to be Indian by the Secretary of the Interior, for any purpose.63 Public school districts must have a minimum number or percentage of ESEA Title VII-eligible Indian students to receive a grant. The ESEA Title VII grants are administered by ED, so ED is the source of data on the ESEA Title VII students.

Another major ED program, the Impact Aid program, funds public schools whose students reside on "Indian lands" or are federally connected children.64 The students residing on Indian lands for whom Impact Aid is provided need not, however, be Indian.

Status of Indian and American Indian/Alaska Native Education

Although there is no source for the status of Indian educational achievement nationally, the educational environment and achievements of BIE students and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) students are reported. Students who identify their race/ethnicity as AI/AN may not be members or descendants of members of federally recognized Indian tribes, and not all members of such tribes may identify as AI/AN. For example, ED's National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), which collects and analyzes student and school data and produces the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP),65 publishes reports on AI/AN students' characteristics and academic achievements. NCES data are based on race/ethnicity (except most data on BIE students), so the data will include students who identify as AI/AN even though they are not members of tribes and do not fall into the eligibility categories of federal Indian education programs. NCES's race/ethnicity-based AI/AN student population is not the same as the student population served by federal Indian education programs. The two populations overlap, but the degree of overlap has not been determined. NCES data based on race/ethnicity, then, cannot be assumed to accurately represent the Indian student population served by federal Indian programs.

BIE Schools and Students

The BIE funds a system consisting of elementary and secondary schools, which provide free education to eligible Indian students, and "peripheral dormitories" (discussed below).66 In 2014 and before, the BIE system was administered by a director and headquarters offices in Washington, DC, and Albuquerque, NM; three Associate Deputy Directors (ADDs) in the west, east, and Navajo area; and 22 education line offices (ELOs) across Indian Country. ELOs provided leadership, technical support, and instructional support for the schools and peripheral dorms.67 Starting in June 2014, the Secretary began restructuring the BIE in an effort to increase tribal capacity to operate schools and improve educational outcomes. The planned structure maintains a director in Washington, DC. It has separate oversight through three ADDs—one serving schools serving the Navajo nation, one serving the remaining BIE operated schools, and one serving tribally operated schools. Fifteen Education Resource Centers (ERC), renamed and restructured ELOs, report to the ADDs.68

The BIE-funded school system includes day and boarding schools and peripheral dormitories. The majority of BIE-funded schools are day schools, which offer elementary or secondary classes or combinations thereof and are located on Indian reservations. BIE boarding schools house students in dorms on campus and also offer elementary or secondary classes, or combinations of both levels, and are located both on and off reservations. Approximately one-third of BIE schools are K-8; while another one-third are either K-12 or K-6.69 Peripheral dormitories house students who attend nearby public or BIE schools; these dorms are also located both on and off reservations.

Elementary and secondary schools funded by the BIE may be operated either directly by the BIE or by tribes and tribal organizations through grants or contracts authorized under the Tribally Controlled Schools Act (TCSA) of 1988 or the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA) of 1975, respectively. (See the discussion of these two acts in "Statutory Authority for BIE Elementary and Secondary Schools," below.) In addition, some schools are operated through a cooperative agreement with a public school district.70 In accordance with state law, the three BIE schools in Maine receive state funding.71 There are eight charter schools co-located at BIE schools.72

BIE funds 169 schools and 14 peripheral dorms. Table 1 shows the number of BIE-funded schools and peripheral dorms, by type of operator. The majority of BIE-funded schools are tribally operated.73

|

Schools and Peripheral |

Tribally |

BIE- |

Total |

|

Total |

130 |

53 |

183 |

|

Elementary/Secondary Schools |

117 |

52 |

169 |

|

Day schools |

92 |

26 |

118 |

|

Boarding schools |

25 |

26 |

51 |

|

Peripheral Dormitories |

13 |

1 |

14 |

Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs, Budget Justifications Fiscal Year 2018 (hereinafter referred to as the FY2018 Budget).

In the mid-1990s, Congress became concerned that adding new BIE schools or expanding existing schools would, in circumstances of limited financial resources, "diminish funding for schools currently in the system."74 As a consequence, the total number of BIE schools and peripheral dorms, the class structure of each school, and co-located charter schools has been limited by Congress. Through annual appropriation acts from FY1994 through FY2011, Congress prohibited BIE from funding schools that were not in the BIE system as of September 1, 1996, and from FY1996 through FY2011 prohibited the use of BIE funds to expand a school's grade structure beyond the grades in place as of October 1, 1995. Appropriations acts since FY2000 have prohibited the establishment of co-located charter schools.

Beginning in FY2012, Congress has begun to loosen restrictions on the size and scope of the BIE school system. The FY2012 appropriations act maintained the aforementioned prohibitions except in the instance of schools and school programs that were closed and removed from the BIE school system between 1951 and 1972 and whose respective tribe's relationship with the federal government was terminated.75 As a result in July 2012, BIE began funding grades 1-6 of Jones Academy in Hartshorne, OK. Jones Academy was previously funded by BIE as a peripheral dormitory for students attending schools in grades 1-12, and by the local public school district as a grades 1-6 elementary school. The appropriations acts since FY2014 have authorized the Secretary to support the expansion of up to one additional grade to accomplish the BIE's mission. As a result, in 2014 the BIE approved funding for the tribally funded 6th grade of the otherwise BIE-funded Shoshone-Bannock Junior High.76 Finally, appropriations acts since FY2015 have authorized the BIE to approve satellite locations of BIE schools at which an Indian tribe may provide language and cultural immersion educational programs as long as the BIE is not responsible for the facilities-related costs. Accordingly, in AY2015-2106 the Nay-Ah-Shing School in Minnesota opened the Pine Grove Satellite Learning Center using broadband and reducing transportation times and costs.77

Only Indian children attend the BIE school system, with few exceptions. In SY2016-2017, BIE-funded schools and peripheral dorms serve approximately 48,000 Indian students representing almost 250 tribes in 23 states.78 For SY2012-2013–SY2014-2015, approximately 62% of BIE-funded schools and dorms averaged 200 or fewer children in attendance.79

BIE schools and dormitories are not evenly distributed across the country. From SY2012-2013 to SY2014-2015, almost 66% of BIE schools and dormitories and approximately 65% of BIE students were located in 3 of the 23 states: Arizona (29% of students), New Mexico (21%), and South Dakota (16%). Table 2 shows the distribution of BIE schools and students across the 23 states. There are no BIE schools or students in Alaska, a circumstance directed by Congress (see "Brief History of Federal Indian Education Activities," above).80

Table 2. BIE Schools and Peripheral Dormitories and Students: Number and Percent, by State, Average SY2012-2013 to SY2014-2015

Descending order by the number of students

|

Schools and Dorms |

Students |

|||

|

State |

Number |

Percentage |

Number |

Percentage |

|

Arizona |

54 |

30% |

11,892 |

29% |

|

New Mexico |

44 |

24% |

8,551 |

21% |

|

South Dakota |

22 |

12% |

6,438 |

16% |

|

North Dakota |

11 |

6% |

3,674 |

9% |

|

Mississippi |

8 |

4% |

2,100 |

5% |

|

Washington |

8 |

4% |

1,696 |

4% |

|

Oklahoma |

5 |

3% |

1,165 |

3% |

|

North Carolina |

1 |

1% |

971 |

2% |

|

Wisconsin |

3 |

2% |

854 |

2% |

|

Minnesota |

4 |

2% |

612 |

1% |

|

California |

2 |

1% |

464 |

1% |

|

Montana |

3 |

2% |

436 |

1% |

|

Michigan |

2 |

1% |

397 |

1% |

|

Oregon |

1 |

1% |

344 |

1% |

|

Maine |

3 |

2% |

293 |

1% |

|

Iowa |

1 |

1% |

258 |

1% |

|

Utaha |

2 |

1% |

254 |

1% |

|

Florida |

2 |

1% |

251 |

1% |

|

Idaho |

2 |

1% |

198 |

0% |

|

Wyoming |

1 |

1% |

188 |

0% |

|

Louisiana |

1 |

1% |

93 |

0% |

|

Nevada |

2 |

1% |

79 |

0% |

|

Kansas |

1 |

1% |

54 |

0% |

|

Totalb |

183 |

100.0% |

41,263 |

100.0% |

Source: FY2017 Budget, Appendix 2.

Notes: Student counts are based on the three-year average daily membership, which counts students attendance during the entire year.

a. Student counts and number of schools and dorms exclude Sevier-Richfield Public Schools in Utah, which receive BIE funds for the education of out-of-state students residing at the BIE-funded Richfield Dormitory.

One measure of a school system's quality and the academic achievement of students is the average score of students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading and mathematics assessments.81 Table 3 indicates that, on average, students in BIE schools score below students in public schools on the NAEP assessment. For example, on the 4th grade 2013 NAEP reading assessment all BIE school students scored an average of 181 while all public school students scored an average of 221.

|

Average NAEP Score |

||||

|

Type of School |

Grade 4 Reading |

Grade 8 Reading |

Grade 4 Math |

Grade 8 Math |

|

2013 |

||||

|

BIE schools |

181 |

235 |

212 |

250 |

|

Public schools |

221 |

266 |

241 |

284 |

|

2015 |

||||

|

BIE schools |

NA |

236 |

NA |

252 |

|

Public schools |

221 |

264 |

240 |

281 |

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Data Explorer, available at http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/naepdata/.

Notes: NA means reporting standards not met.

Public Schools and AI/AN Students

There were approximately 50 million public school students enrolled in elementary and secondary schools in fall 2013, and 523,000 (1.0%) were AI/ANs.82 In fall 2013 (the latest data available), approximately 80% of AI/AN students lived in 16 states. These states, presented in descending order of their number of AI/AN students, are Oklahoma, Arizona, California, New Mexico, Alaska, North Carolina, Texas, Montana, New York, South Dakota, Minnesota, Washington, Michigan, Wisconsin, Oregon, and Florida.83 A greater than average proportion of AI/AN students live in poverty and require services for students with disabilities.84 The percentage of AI/AN children under age 18 in families living in poverty was 35% in 2014.85 In SY2013–2014, the percentage of AI/AN children ages 3–21 who were served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) as a percentage of total enrollment in public schools was highest for AI/AN students (17%), the highest among all racial/ethnic groups.86 The percentage of 16- through 24-year-old AI/AN students who were not enrolled in school and had not earned a high school credential was 12% in 2014, compared to 6% for all 16- through 24-year-olds.87

The educational achievement of AI/AN students in public schools can be deduced from the average scores of AI/AN and non AI/AN students on the NAEP. Table 4 presents results of the 2015 NAEP for AI/AN and non AI/AN students in grades 4, 8, and 12. The average NAEP score for AI/AN students is consistently lower than that for white and Asian/Pacific Islander students. Although it is generally above the scores for black students and similar to the scores of Hispanic students.

Table 4. Average Public School Scores in NAEP Reading and Math, by Assessment and Student Race/Ethnicity: 2015

|

Average NAEP Score |

||||||

|

Student Race/Ethnicity |

Grade 4 Reading |

Grade 8 Reading |

Grade 12 Reading |

Grade 4 Math |

Grade 8 Math |

Grade 12 Math |

|

AI/AN |

206 |

253 |

278 |

228 |

267 |

137 |

|

White |

232 |

273 |

294 |

248 |

291 |

159 |

|

Black |

206 |

247 |

265 |

224 |

260 |

129 |

|

Hispanic |

208 |

253 |

275 |

230 |

229 |

138 |

|

Asian/Pacific Islander |

238 |

279 |

297 |

256 |

305 |

169 |

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Data Explorer, available at http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/naepdata/.

Notes: AI/AN means American Indian/Alaska Native.

Federal Indian Elementary and Secondary Education Programs and Services

Federal Indian elementary and secondary education programs serve Indian elementary and secondary students in public schools, private schools, and the BIE system. Except for one BIE program, public schools do not generally receive BIE funding. Public schools instead receive most of their federal assistance for Indian education through the U.S. Department of Education (ED). BIE-funded schools, on the other hand, receive funding both from the BIE and from ED. The BIE estimates that it provides about 75% of BIE-funded schools' overall federal funding, and ED provides the remainder.88 This section of the report profiles first the BIE programs and second those ED programs that provide significant funding for Indian education.

Statutory Authority for BIE Elementary and Secondary Schools

Currently, BIE-funded schools, dorms, and programs are administered under a number of statutes. The key statutes are summarized here.

Snyder Act of 192189

This act provides a broad and permanent authorization for federal Indian programs, including for "[g]eneral support and civilization, including education." The act was passed because Congress had never enacted specific statutory authorizations for most BIA activities, including BIA schools. Congress had instead made detailed annual appropriations for BIA activities. Authority for Indian appropriations in the House had been assigned to the Indian Affairs Committee after 1885 (and in the Senate to its Indian Affairs Committee after 1899). Rules changes in the House in 1920, however, moved Indian appropriations authority to the Appropriations Committee, making Indian appropriations vulnerable to procedural objections because they lacked authorizing acts. The Snyder Act was passed in order to authorize all the activities the BIA was then carrying out. The act's broad language, however, may be read as authorizing—though not requiring—nearly any Indian program, including education, for which Congress enacts appropriations.

Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (ISDEAA)90

ISDEAA, as amended, provides for tribal administration of certain federal Indian programs, including BIA and BIE programs. The act allows tribes to assume some control over the management of BIE-funded education programs by negotiating "self-determination contracts" or Title IV "self-governance compacts" with BIE. Under a self-determination contract, BIE transfers to tribal control the funds it would have spent for the contracted school or dorm, so the tribe may operate it. Tribes or tribal organizations may contract to operate one or more schools.91 As of February 2017, only one BIE school, Miccosukee Indian School in Florida, is funded through an ISDEAA contract.92

Education Amendments Act of 197893

Title XI of this act, as amended by the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB; P.L. 107-110), "declares" federal policy on Indian education and establishes requirements and guidelines for the BIE-funded elementary and secondary school system. As amended, the act covers academic accreditation and standards, a funding allocation formula, BIE powers and functions, criteria for boarding and peripheral dorms, personnel hiring and firing, the role of school boards, facilities standards, a facilities construction priority system, and school closure rules, among other topics. It also authorizes several BIE grant programs, including administrative cost grants for tribally operated schools (described below), early childhood development program grants (also described below), and grants and technical assistance for tribal departments of education.

Tribally Controlled Schools Act (TCSA) of 198894

TCSA added grants as another means, besides ISDEAA contracts, by which Indian tribes and tribal organizations may operate BIE-funded schools. The act requires that each grant include all funds that BIE would have allocated to the school for operation, administrative cost grants, transportation, maintenance, and ED programs. Because ISDEAA contracts were found to be a more cumbersome means of Indian control of schools, most tribally operated schools are grant schools.95

BIE Elementary and Secondary Education Programs

Funding for and operation of BIE-funded schools are carried out through a number of different programs. The major BIE funding programs are "forward-funded"—that is, the BIE programs' appropriations for a fiscal year are used to fund the school year that begins during that fiscal year.96 Forward funding in the case of elementary and secondary education programs was designed to allow additional time for school officials to develop budgets in advance of the beginning of the school year. These forward-funded appropriations are specified through provisions in the annual appropriations bill.

Indian School Equalization Program (ISEP)97

The Indian School Equalization Program (ISEP) is the formula-based grant program through which congressional appropriations for BIE-funded schools' academic (and, if applicable, residential) operating costs are allocated among the schools. ISEP grant funds are the primary funding for basic and supplemental educational programs for Indian students attending BIE-funded schools. In addition, ISEP grant funds pay tuition to Sevier Public Schools in Utah for out-of-state Indian students living in the nearby BIE Richfield peripheral dormitory. The ISEP allocation formula, although authorized under the Education Amendments of 1978, is specified not in statute but in federal regulations. The formula is based on a count of student "average daily membership" (ADM) that is weighted to take into account schools' grade levels and students' residential-living status (e.g., in boarding schools or peripheral dorms) and is then supplemented with weights or adjustments for gifted and talented students, language development needs, supplemental education programs, and a school's size. The final weighted figure is called the "weighted student unit" (WSU). A three-year WSU average is calculated for each school and nationally. Each school receives a portion of the ISEP appropriation that is the same proportion that the school's three-year WSU average is to the national three-year average WSU.98

Before allocation under the funding formula, part of ISEP funds are set aside for program adjustments, contingencies, and appeals. In recent years, program adjustments have funded safety and security projects, behavior intervention programs, targeted education projects to increase academic achievement, police services, and parental participation projects. The targeted education project from SY2005-2006 to SY2015-2016 was the FOCUS program, which supported at-risk students in schools that were close to making adequate yearly progress (AYP) by providing for technical assistance on effective teaching practices and data-driven instructional decision-making.99 The targeted program starting in SY2016-2017 is intended to build school staff capacity with respect to budget and programming.

Student Transportation

To transport its students, both day and boarding, the BIE funds an extensive student transportation system. Student transportation funds provide for buses, fuel, maintenance, and bus driver salaries and training, as well as certain commercial transportation costs for some boarding school students. Because of largely rural and often remote school locations, many unimproved and dirt roads, and the long distances from children's homes to schools, transportation of BIE students can be expensive. Student transportation funds are distributed on a formula basis, using commercial transportation costs and the number of bus miles driven (with an additional weight for unimproved roads).100

Early Child and Family Development

BIE's early childhood development program provides grants to tribes and tribal organizations for services for pre-school Indian students and their parents.101 The program includes early childhood education for children under six years old, and parenting skills and adult education for their parents to improve their employment opportunities. The grants are distributed by formula among applicant tribes and organizations who meet the minimum tribal size of 500 members. From 1991 to 2013, FACE served over 19,000 adults and 21,000 children at 61 different schools.102 In SY 2015-2016, the last full year for which data are available, 2,129 adults and 2,265 children were served.103

Tribal Grant Support Costs (Administrative Cost Grants)

Tribal grant support costs,104 formerly known as administrative cost grants, pay administrative and indirect costs for tribally operated TCSA-grant schools. Administrative costs for BIE-operated schools are funded through BIE program management appropriations. By providing assistance for direct and indirect administrative costs that may not be covered by ISEP or other BIE funds, administrative cost grants are intended to encourage tribes to take control of their schools. These are formula grants based on an "administrative cost percentage rate" for each school, with a minimum grant of $200,000. For the first time in FY2016, appropriations fully funded the statutorily determined grant amounts without the need for a ratable reduction.

Facilities Operations

This program funds the operation of educational facilities at all BIE-funded schools and dorms. Operating expenses may include utilities, supplies, equipment, custodians, trash removal, maintenance of school grounds, minor repairs, and other services, as well as monitoring for fires and intrusions. This is not a forward-funded program. These funds are available at the beginning of the fiscal year for a period of 24 months.

Facilities Maintenance

This program funds preventive, routine cyclic, and unscheduled maintenance for all school buildings, equipment, utility systems, and ground structures. Like facilities operations funds, the funds are available at the beginning of the fiscal year for a period of 24 months. Appropriations for facilities maintenance were transferred from the BIA Construction account to the BIE account in FY2012.

Education Program Enhancements

Education Program Enhancements receive a line item in the appropriations request. This program allows the BIE discretion to provide targeted improvements and interventions. Examples of activities funded in recent years include supporting BIE reorganization efforts, providing leadership training and professional development, funding the Sovereignty in Indian Education (SIE) Enhancement program, and developing partnerships with tribally controlled colleges. In addition, funding has been used to develop tribal education departments.

Residential Education Placement Program

The Residential Education Placement program ensured that eligible Indian students with disabilities or social or emotional needs received an appropriate education in the least restrictive environment and as close to home as possible. Services included physical and occupational therapy, counseling, and alcohol and substance abuse treatment. In SY2008-2009, the BIE served 59 institutionalized students.105 The program was last funded in FY2011.

Juvenile Detention Education

The Juvenile Detention Education program supported educational services for children in BIA-funded detention facilities. This is not a forward-funded program. The program was funded in FY2007-FY2011 and then again in FY2016.

Tribal Education Department Grants106

The Secretary is authorized to make grants and provide technical assistance to tribes for the development and operation of tribal departments of education (TEDs) for the purpose of planning and coordinating all educational programs of the tribe. Beginning in FY2015, funds have been awarded under the authority to promote tribal control and operation of BIE-funded schools on their reservations. Funds have also been awarded to begin restructuring school governance, build capacity for academic success, and develop academically rigorous and culturally relevant curricula.

Johnson O'Malley Program (BIE Assistance to Public Schools)107

There is one program by which the BIE provides assistance to tribes, tribal organizations, states, and LEAs for Indian students attending public schools. The Johnson O'Malley (JOM) program provides supplementary financial assistance, through contracts, to meet the unique and specialized educational needs of eligible Indian students in public schools and non-sectarian private schools. Eligible Indian students, according to BIE regulations, are students in public schools who are at least one-quarter degree Indian blood and recognized by the BIA as eligible for BIA services.108 BIE contracts with tribes and tribal organizations to distribute funds to schools or other programs providing JOM services, and it also contracts directly with states and public school districts for JOM programs. Most JOM funds are distributed through tribal contractors—88% as of FY2012.109 Prospective contractors must have education plans that have been approved by an Indian education committee made up of parents of Indian students. Funds are to be used for supplemental programs, such as tutoring, other academic support, books, supplies, Native language classes, cultural activities, summer education programs, after-school activities, or a variety of other education-related needs. JOM funds may be used for general school operations only when a public school district cannot meet state educational standards or requirements without them, and enrollment in the district is at least 70% eligible Indian students.110 This is not a forward-funded program.

BIA School Facilities Repair and Construction and Faculty Housing

The BIA funds repair, improvement, and construction activities for BIE schools and school facilities. Activities may include replacing all facilities on an existing BIE school campus, replacing individual buildings, or making minor and major repairs and improvements. Included in the education construction program is improvement and repair of BIE employee housing units. Construction may be administered either by the BIA or by tribes under the ISDEAA or the TCSA. In order to prioritize projects and guide expenditures, the BIA maintains an aggregate Facilities Condition Index (FCI), Asset Priorities Index (API), a Replacement School Construction Priority list, a Five Year Deferred Maintenance and Construction Plan, an Asset Management Plan (AMP), a list of necessary emergency repairs, and a list of deficiencies with respect to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA; 42 U.S.C. §12101 et seq.), Uniform Federal Accessibility Standards (UFAS; 42 U.S.C. §§4151-4157), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), and other requirements.

BIE and BIA Elementary and Secondary Education Appropriations

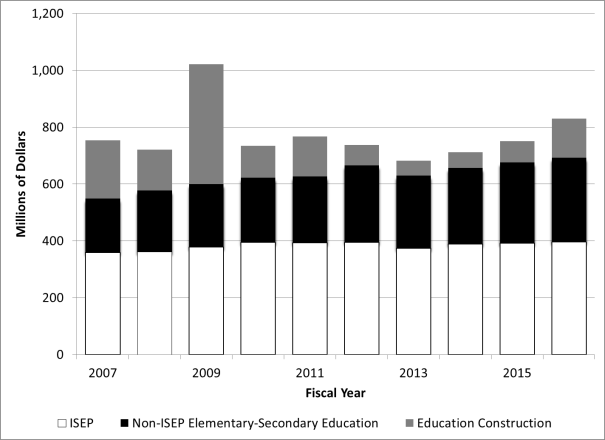

Indian affairs (the budgetary combination of BIA and BIE functions) appropriations for elementary and secondary education are divided between program funds, expended through the BIE, and construction and related spending carried out through the BIA. Table 5 shows detailed appropriations for BIE programs and BIA education construction for FY2007-FY2016.

In nominal dollars, total BIA and BIE spending on elementary-secondary education and construction has increased 10% over the 10-year period, from $754 million to $831 million. In constant FY2016 dollars, total BIA and BIE spending on elementary-secondary education and construction has decreased 5% over the same 10-year period.111 Educational programming appropriations in nominal dollars for BIE elementary-secondary programs have risen 26% over the same period, from $549 million in FY2007 to $693 million in FY2016 in nominal dollars.112 Most of the increase is attributable to increased appropriations for ISEP and Tribal Grant Support Costs, and transferring appropriations for facilities maintenance from the BIA Education Construction account to the BIE Elementary-Secondary Education account. As illustrated in Figure 2, and with the exception of FY2009, BIA education construction appropriations in nominal dollars have fallen 33%, from $205 million in FY2007 to $138 million in FY2016. Besides the facilities maintenance appropriation account transfer, this decrease is a result of lower appropriations for school and facility construction.

|

Figure 2. Appropriations for BIE Operations and BIA Education Construction, FY2007-FY2016 (in current dollars) |

|

|

Source: Figure prepared by CRS based on U.S. Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Years 2007-2017. Notes: BIA Education Construction includes a small amount of funds for BIA postsecondary institutions. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5) appropriated $292 million for replacement school construction and facilities improvement and repair. |

Table 5. Appropriations for BIE Elementary-Secondary Education Programs and BIA Education Construction, FY2007-FY2016

(current dollars in thousands)

|

FY2007 |

FY2008 |

FY2009 |

FY2009 ARRAa |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

|

|

BIE Elementary-Secondary Education |

549,293 |

577,863 |

600,881 |

— |

622,609 |

626,903 |

666,752 |

630,285 |

657,074 |

676,556 |

692,872 |

|

Elementary/Secondary (forward-funded) |

458,310 |

479,895 |

499,470 |

— |

518,702 |

520,048 |

522,247 |

493,701 |

518,318 |

536,897 |

533,458 |

|

ISEP Formula Funds |

351,817 |

358,341 |

375,000 |

— |

391,699 |

390,361 |

390,707 |

368,992 |

384,404 |

386,565 |

391,837 |

|

ISEP Program Adjustments |

7,533 |

3,205 |

3,266 |

— |

3,338 |

3,331 |

5,278 |

5,019 |

5,324 |

5,353 |

5,401 |

|

Tribal Education Departments (TEDs) |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

2,000 |

2,000 |

|

Student Transportation |

42,833 |

47,844 |

50,500 |

— |

52,808 |

52,692 |

52,632 |

49,870 |

52,796 |

52,945 |

53,142 |

|

Early Childhood Development |

12,067 |

15,024 |

15,223 |

— |

15,374 |

15,341 |

15,345 |

14,564 |

15,451 |

15,520 |

15,620 |

|

Tribal Grant Support Costsb |

44,060 |

43,373 |

43,373 |

— |

43,373 |

46,280 |

46,253 |

43,834 |

48,253 |

62,395 |

73,276 |

|

Education Program Enhancements |

— |

12,108 |

12,108 |

— |

12,110 |

12,043 |

12,032 |

11,422 |

12,090 |

12,119 |

12,182 |

|

Elementary/Secondary Programs |

72,390 |

74,621 |

75,126 |

— |

77,379 |

76,939 |

122,534 |

116,326 |

118,402 |

119,195 |

134,263 |

|

Facilities Operation |

56,047 |

56,504 |

56,972 |

— |

59,410 |

59,149 |

58,565 |

55,521 |

55,668 |

55,865 |

63,098 |

|

Facilities Maintenancec |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

50,665 |

48,190 |

48,396 |

48,591 |

55,887 |

|

Residential Education Placement Programd |

3,713 |

3,715 |

3,737 |

— |

3,760 |

3,755 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Juvenile Detention Education |

630 |

620 |

620 |

— |

620 |

619 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

500 |

|

Johnson-O'Malley Program |

12,000 |

13,782 |

13,797 |

— |

13,589 |

13,416 |

13,304 |

12,615 |

14,338 |

14,739 |

14,778 |

|

Education Management |

18,593 |

23,347 |

26,285 |

— |

26,528 |

29,916 |

21,971 |

20,258 |

20,354 |

20,464 |

25,151 |

|

BIA Education Constructione |

204,956 |

142,935 |

128,837 |

292,311 |

112,994 |

140,509 |

70,826 |

52,779 |

55,285 |

74,501 |

138,245 |

|

Replacement School Construction |

83,891 |

46,716 |

22,405 |

141,634 |

5,964 |

21,463 |

17,807 |

— |

954 |

20,165 |

45,504 |

|

Replacement Facility Construction |

26,873 |

9,748 |

17,013 |

— |

17,013 |

29,466 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

11,935 |

|

Employee Housing Repair |

1,973 |

1,942 |

4,445 |

— |

4,451 |

4,438 |

4,428 |

4,405 |

11,935 |

3,823 |

7,565 |

|

Education Facilities Improvement and Repair |

92,219 |

84,529 |

84,974 |

150,677 |

85,566 |

85,142 |

48,591 |

48,374 |

50,513 |

50,513 |

73,241 |

|

Total: BIE Elementary-Secondary Education and Education Construction |

754,249 |

720,798 |

729,718 |

292,311 |

735,603 |

767,412 |

737,578 |

683,064 |

712,359 |

751,057 |

831,117 |

Source: "Annual comprehensive budget table," in U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Years 2007-2017.

Notes: In this table, "BIA" includes all Indian programs under the Assistant Secretary–Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior. Totals for BIE elementary-secondary education were calculated by CRS. N/A = not applicable.

Abbreviations:

BIA—Bureau of Indian Affairs

BIE—Bureau of Indian Education

ISEP—Indian School Equalization Program

a. FY2009 ARRA funds were appropriated by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; P.L. 111-5).

b. Tribal grant support costs were previously entitled Administrative Cost Grants.

c. Appropriations for facilities maintenance were transferred from the BIA Education Construction account to the BIE Elementary-Secondary Education account in FY2012.

d. The Residential Education Placement Program was formerly called the Institutionalized Disabled Program.

e. Education construction includes a small amount of funds for BIA postsecondary education institutions.

U.S. Department of Education Elementary and Secondary Indian Education Programs

The U.S. Department of Education (ED) provides funding specifically for Indian elementary and secondary education to both public and BIE schools. About three-quarters of this Indian education-specific funding goes to public schools and related organizations (see Table 6 below).

ED's assistance specifically for Indian education is not to be confused with its general assistance to elementary and secondary education nationwide. Indian students benefit from ED's general assistance as they attend public schools. This section covers ED Indian assistance—that is, assistance statutorily specified for Indians or allotted according to the number of Indians—not general ED assistance that may also benefit Indian students.

ED Indian education funding to public and BIE schools flows through a number of programs, most authorized under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) or the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), although other acts also authorize Indian education assistance. ESEA amendments enacted through the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA; P.L. 114-95) become effective for AY2017-2018 for the programs described herein. For more information on IDEA programs, see CRS Report R41833, The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B: Key Statutory and Regulatory Provisions, by Kyrie E. Dragoo; and CRS Report R43631, The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part C: Early Intervention for Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities, by Kyrie E. Dragoo.

Major ED Indian programs are profiled below. Some general ED programs have set-asides for BIE schools, while other programs either may be intended solely for Indian students, may specifically include Indian and non-Indian students, or may mention Indian students as a target of the assistance. In many instances, BIE schools are included in the definition of local educational agency (LEA) in the ESEA113 and IDEA,114 so many ED programs may provide funding to BIE schools even when the programs have no BIE set-aside or other specific provision for BIE schools, but these programs are not discussed here. Tribes, tribal organizations, the BIE, and BIE schools are also specifically eligible to apply for certain programs, which are not described here.

ESEA Title I-A Grants to Local Educational Agencies

Title I, Part A, of the ESEA authorizes formula grants to LEAs for the education of disadvantaged children. ESEA Title I-A grants provide supplementary educational and related services to low-achieving and other students attending pre-kindergarten through grade 12 schools with relatively high concentrations of students from low-income families. ESEA, as amended by ESSA, reserves 0.4% for the outlying areas and 0.7% for DOI unless the set-asides result in the states receiving less than their aggregate FY2016 amount, in which case the provisions under ESEA prior to the enactment of ESSA are in effect.115 DOI funds are for BIE schools and for out-of-state Indian students being educated in public schools under BIE contracts (e.g., students in peripheral dorms).

ESEA Title I-B State Assessment Grants

The ESEA authorizes formula grants to states to support the development and implementation of state assessments and standards as required under ESEA Title I-A. ESEA Title I-B, as amended by ESSA, provides a set-aside of 0.5% for BIE.

ESEA Title II-A Supporting Effective Instruction

The ESEA authorizes formula grants to states that may be used for a variety of purposes related to the recruitment, retention, and professional development of K-12 teachers and school leaders. The ESEA Title II-A program, as amended by ESSA, provides a 0.5% set-aside of appropriations for programs in BIE schools.

ESEA Title III-A English Language Acquisition

Title III, Part A of the ESEA authorizes formula grants to states to provide programs for and services to English learners (ELs), also known as limited English proficient (LEP) students, and immigrant students. The program is designed to help ensure that ELs and immigrant students attain English proficiency, develop high levels of academic achievement in English, and meet the same state academic standards that all students are expected to meet. The program provides a set-aside equal to the greater of 0.5% of appropriations or $5 million for Native American and Alaska Native Children in School. The set-aside is available to eligible Indian tribes, tribally sanctioned educational authorities, Native Hawaiian or Native American Pacific Islander native language educational organizations, BIE elementary and secondary schools, and consortia of BIE elementary and secondary schools.

ESEA Title IV-B 21st Century Community Learning Centers

Title IV, Part B, of the ESEA authorizes formula grants to states for activities that provide learning opportunities for school-aged children during non-school hours. States award competitive subgrants to LEAs and community organizations for before- and after-school activities that will advance student academic achievement. The program provides a set-aside of no more than 1% of Title IV-B appropriations for the BIE and the outlying areas. The portion of the 1% that goes to the BIE is determined by the Secretary of Education.

ESEA Title VI-A Indian Education Programs

Title VI, Part A, Subpart 1 of the ESEA, as amended by ESSA, authorizes formula grants for supplementary education programs to meet the educational and cultural needs of Indian students. LEAs, Indian tribes, Indian organizations, Indian community-based organizations, consortia of the aforementioned entities, and BIE schools are eligible for grants. For an LEA to be eligible, at least 10 Indian students must be enrolled or at least 25% of its total enrollment must be Indians (exempted from these requirements are LEAs in Alaska, California, and Oklahoma and LEAs located on or near an Indian reservation). An LEA's application must be approved by a local committee of family members of Indian students and other stakeholders.

The Indian Education programs also authorize special competitive grant programs. One provides demonstration grants to develop innovative services and programs to improve Indian students' educational opportunities and achievement. Another competitive program provides for professional development grants to colleges, or tribes or LEAs in consortium with colleges, to train Indian individuals as teachers or other professionals.

In addition, the Indian Education programs authorize national programs. For example, grants to tribes for education administrative planning and development are authorized. Funds are also authorized for the National Advisory Council on Indian Education (NACIE), which advises the Secretary of Education and Congress on Indian education.

ESEA Title VI-C Alaska Native Education Equity

Title VI, Part C, of the ESEA authorizes competitive grants to Alaska Native organizations, educational entities with Native experience, and cultural and community organizations for supplemental education programs that address the educational needs of Alaska Native students, parents, and teachers. Grants may be used for development of curricula and educational materials, student enrichment in science and math, professional development, family literacy, home preschool instruction, cultural exchange, dropout prevention, and other programs.

ESEA Title VII Impact Aid

Title VII of the ESEA, as amended by ESSA, authorizes Impact Aid Basic Support Payments. Impact Aid provides financial assistance to school districts whose tax revenues are significantly reduced, or whose student enrollments are significantly increased, because of the impacts of federal property ownership or federal activities. Among such impacts are having a significant number of children enrolled who reside on "Indian lands,"116 which is defined as Indian trust and restricted lands,117 lands conveyed to Alaska Native entities under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971,118 public lands designated for Indian use, and certain lands used for low-rent housing. Impact Aid funds are distributed by formula directly to LEAs and are used for basic operating costs, special education, and facilities construction and maintenance. There is no requirement that the funds be used specifically or preferentially for the education of Indian students. There is, however, a requirement that Indian children participate on an equal basis with non-Indian children in all of the educational programs and activities provided by the LEA, including but not limited to those funded by Impact Aid. There is also a requirement that the LEA consult with the parents and tribes of children who reside on "Indian lands" concerning their education and to ensure that these children receive equal educational opportunities. A few BIE schools receive Impact Aid funding. ED indicates that about 113,000 students residing on Indian lands were used to determine formula allocations under Impact Aid for FY2015.119 The amount of Impact Aid funding going to LEAs based on the number of children residing on Indian lands makes it the largest ED Indian education program.

IDEA Part B Special Education Grants to States

Part B of the IDEA authorizes formula grants to states to help them provide a free appropriate public education to children with disabilities. States make subgrants to LEAs. Funds may be used for salaries of teachers or other special education personnel, education materials, transportation, special education services, and occupational therapy or other related services. Section 611(b)(2) of the IDEA reserves 1.226% of state-grant appropriations for DOI. Each appropriations act since the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2006 (P.L. 109-149) has limited the DOI set-aside to the prior-year set-aside amount increased for inflation.120 As a consequence, in FY2016 the DOI set-aside is 0.79%. Section 611(h) of the IDEA directs the Secretary of the Interior to allocate 80% of the funds to BIE schools for special education for children aged 5-21 and 20% to tribes and tribal organizations on reservations with BIE schools for early identification of children with disabilities aged 3-5, parent training, and provision of direct services.

IDEA Part C Early Intervention for Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities

Part C of the IDEA authorizes a grant program to aid each state in implementing a system of early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families. Section 643(b) of the IDEA reserves 1.25% of state-grant appropriations for DOI to distribute to tribes and tribal organizations for the coordination of assistance in the provision of early intervention services by the states to infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families on reservations served by BIE schools.

MVHAA Education for Homeless Children and Youths

Title VII, Part B, of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (MVHAA; 42 U.S.C. §§11431-11435) authorizes the Education for Homeless Children and Youth (EHCY) program. The program provides assistance to SEAs to ensure that all homeless children and youth have equal access to the same free appropriate public education, including public preschool education that is provided to other children and youth. The program provides a 1.0% set-aside of the appropriation to DOI for services provided by BIE to homeless children and youth.

Perkins Native American Career and Technical Education Program (NACTEP)

Title I of the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006 (Perkins IV; P.L. 109-270) authorizes formula grants to states to support the development of career and technical skills among students in secondary and postsecondary education. The program provides a 1.25% set-aside for the Native American Career and Technical Education Program (NACTEP). Eligible entities for NACTEP funds include federally organized Indian tribes, tribal organizations, Alaska Native entities, and consortia of such, as well as BIE schools.121

ED Elementary and Secondary Indian Education Funding

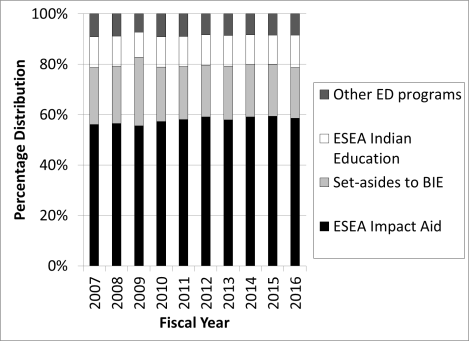

ED Indian education funding primarily supports public schools. With the exception of FY2009, less than a quarter of ED Indian education funds are set aside for BIE schools (see Figure 3); however, this constitutes a significant source of BIE school funding. FY2009 funding was augmented by additional appropriations from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; P.L. 111-5).

In nominal dollars, the total ED Indian education program funding pattern during FY2007-FY2016 showed a steady increase, excluding funding from ARRA, from FY2007 ($.981 billion) to FY2012 ($1.084 billion), followed by a 6% decline in FY2013. The FY2013 decline was primarily a result of sequestration.122 Funding has increased since FY2013 to a 10-year high in nominal dollars in FY2016 ($1.119 billion), excluding funding from ARRA (see Table 6). In constant FY2016 dollars, total ED Indian education program spending on elementary-secondary education has decreased 1% over the same 10-year period.123

Impact Aid is the largest single ED elementary and secondary Indian education program, as Figure 3 illustrates. The second-largest funding stream is the BIE set-asides from several ESEA formula grant programs, especially IDEA Part B and ESEA Title I-A. The ESEA Indian Education programs provide over 10% of the total funding. Other ED programs—focused on Alaska Natives, career and technical education, early childhood education, and English language acquisition—account for about 8% of the ED funding provided for Indian education.

Table 6. Estimated Funding for Department of Education's Indian Elementary-Secondary Education Programs, in Descending Order of FY2015 Funding: FY2007-FY2016

(current dollars in thousands)

|

Education Department (ED) Programs |

FY2007 |

FY2008 |

FY2009 |

FY2009 ARRAa |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

|

Total ED Indian Elementary-Secondary Education Programs |

980,780 |

1,003,941 |

1,059,633 |

170,457 |

1,059,807 |

1,070,522 |

1,084,371 |

1,017,562 |

1,049,657 |

1,060,280 |

1,119,481 |

|

Subtotal of ED Funds Set-Aside for the BIE |

222,078 |

228,676 |

235,295 |

98,758 |

229,009 |

225,986 |

223,480 |

216,666 |

217,872 |

216,883 |

225,198 |

|

Percentage of Total |

23% |

23% |

22% |

58% |

22% |

21% |

21% |

21% |

21% |

20% |

20% |

|

ESEA Title I-A Grants to Local Educational Agencies |

91,754 |

96,688 |

101,126 |

72,314 |

100,671 |

101,456 |

98,209 |

93,299 |

92,597 |

93,711 |

99,640 |

|

IDEA Part B Special Education Grants to States |

87,433 |

88,767 |

92,012 |

- |

92,012 |

92,012 |

92,910 |

92,910 |

93,805 |

94,009 |

94,170 |

|

ESEA Title II-A Improving Teacher Quality State Grants |

14,365 |

14,603 |

14,665 |

- |

14,665 |

12,263 |

12,271 |

11,631 |

11,690 |

11,690 |

11,690 |

|

ESEA Title IV-B 21st Century Community Learning Centers |

7,129 |

8,070 |

8,163 |

- |

8,433 |

8,304 |

8,416 |

7,650 |

8,055 |

7,892 |

8,244 |

|

IDEA Part C Grants for Infants and Families with Disabilities |

5,388 |

5,378 |

5,623 |

- |

5,623 |

5,291 |

5,342 |

5,181 |

5,414 |

5,414 |

5,661 |

|

ESEA Title I, Section 1003 School Improvement Grantsb |

877 |

3,322 |

3,793 |

20,870 |

3,682 |

3,671 |

3,332 |

3,152 |

3,091 |

3,091 |

2,808 |

|

ESEA State Assessment Grants |

2,000 |

2,000 |

2,000 |

- |

2,000 |

1,900 |

1,900 |

1,801 |

1,845 |

- |

1,845 |

|

MVHAA Title VII-B Homeless Children and Youth |

619 |

641 |

654 |

700 |

654 |

653 |

652 |

618 |

650 |

650 |

700 |

|

ESEA Title VI-B Rural Education |

422 |

430 |

430 |

- |

437 |

436 |

448 |

425 |

425 |

425 |

440 |

|

ESEA Title IV-A Safe and Drug-Free Schoolsc |

4,750 |

4,750 |

4,750 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

300 |

- |

- |

|

ESEA Title II-D Educational Technology State Grantsc |

2,001 |

1,966 |

1,984 |

4,875 |

735 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

ESEA Title I-B-4 Literacy through School Librariesb |

195 |

96 |

96 |

- |

96 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

ESEA Title I-B Reading Firstb |

5,146 |

1,965 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Subtotal of Other ED Funds for Indian Education |

758,702 |

775,265 |

824,339 |

71,698 |

830,798 |

844,536 |

860,891 |

800,897 |

831,785 |

843,396 |

894,282 |

|

Percentage of Total |

77% |

77% |

78% |

42% |

78% |

79% |

79% |

79% |

79% |

80% |

80% |

|

ESEA Impact Aid—Basic Supportd |

520,436 |

528,558 |

573,448 |

- |

577,105 |

592,445 |

602,846 |

555,688 |

591,392 |

592,642 |

626,138 |

|

ESEA Indian Education—LEA Grants |

95,331 |

96,613 |

99,331 |

- |

104,331 |

104,122 |

105,851 |

100,381 |

100,381 |

100,381 |

100,381 |

|

Voc. Rehab. For AIs with Disabilities |

34,444 |

34,892 |

36,113 |

- |

42,899 |

43,550 |

37,898 |

37,224 |

37,201 |

39,160 |

43,000 |

|

ESEA Indian Education—Special Programs |

19,399 |

19,060 |

19,060 |

- |

19,060 |

19,022 |

18,796 |

17,993 |

17,993 |

17,993 |

37,993 |

|

ESEA Alaska Native Education Equity |

33,907 |

33,315 |

33,315 |

- |

33,315 |

33,248 |

32,853 |

31,453 |

31,453 |

31,453 |

32,453 |

|

ESEA Impact Aid—Disabilities |

21,345 |

20,972 |

21,163 |

- |

20,676 |

20,293 |

20,047 |

21,550 |

19,827 |

19,827 |

20,688 |

|

Perkins Native American Career and Technical Education Program |

14,780 |

14,511 |

14,511 |

- |

14,511 |

14,027 |

14,038 |

13,306 |

13,970 |

13,970 |

13,970 |

|

ESEA Impact Aid—Construction "Formula" |

8,910 |

- |

- |

21,208 |

8,755 |

8,737 |

- |

- |

8,703 |

- |

8,703 |

|

ESEA Indian Education—National Programs |

3,960 |

3,891 |

3,891 |

- |

3,891 |

3,883 |

5,852 |

5,565 |

5,565 |

5,565 |

5,656 |

|

ESEA Title III-A English Language Acquisition |

5,000 |

4,990 |

5,000 |

- |

5,000 |

4,950 |

5,000 |

5,000 |

5,000 |

5,000 |

5,000 |

|

Special Ed. Parent Info. Centers |

- |

- |

- |

- |

259 |

259 |

269 |

209 |

300 |

- |

300 |

|

ESEA Impact Aid—Construction "Discretionary"e |

- |

17,509 |

17,509 |

50,490 |

- |

- |

17,441 |

12,529 |

- |

17,406 |

- |

|

ESEA Title I-B-3 Even Startb |

1,189 |

954 |

997 |

- |

997 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Budget Service, unpublished tables, transmitted on various dates, 2008-2017. The most recent table was transmitted February 13, 2017.

Notes: Columns may not sum to totals due to rounding.

Abbreviations:

ED—U.S. Department of Education

ESEA—Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

IDEA—Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

LEA—Local educational agency (school district)

MVHAA—McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act

Perkins—Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006.

a. FY2009 ARRA funds were appropriated by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; P.L. 111-5).

b. This program was not reauthorized by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA; P.L. 114-95).

c. This program was not specifically reauthorized by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA; P.L. 114-95). The ESSA authorizes the Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grants program (Title IV-A-1), which provides a 0.5% set-aside for BIE schools to support a well-rounded education, school safety, and technology use.

Issues in Indian Education

Some of the issues of concern with regard to Indian education pertain to the comparatively poor academic outcomes of Indian students, Indian communities' desire for greater control of education, the effect of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) on Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) schools, the poor condition of BIE school facilities, and the allocation of Johnson O'Malley funds. The federal government has been actively engaged in addressing these issues in a holistic manner in hopes of ultimately increasing the academic achievement of Indian students.

In 2011, the President signed Executive Order 13592, Improving American Indian and Alaska Native Educational Opportunities and Strengthening Tribal Colleges and Universities. The order commits Department of the Interior (DOI) and Department of Education (ED) to tribal self-determination; Native language, culture, and history education; and to working to provide a quality education for American Indians and Alaska Natives. As a consequence of the order, the departments signed a 2012 agreement to cement and designate the responsibilities of their collaboration toward fulfilling the order.

In recent years, Congress has also supported efforts to address these issues. Beginning in 2012, Congress appropriated funds specifically to promote tribal self-determination with respect to public schools. Several ESEA provisions adopted through ESSA are designed to increase Indian and tribal influence in public schools. In recent years, authorizing and appropriating committees have held hearings on the condition of BIE school facilities. In addition, Congress has required BIE to address the process for reallocating Johnson O'Malley funds.

Poor Academic Achievement and Outcomes

There are significant gaps in educational outcomes for Indian students in BIE schools and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) students in public schools compared to other students. For more information on educational outcomes, see the earlier section entitled "Status of Indian and American Indian/Alaska Native Education." As noted in the ESEA, "it is the policy of the United States to fulfill the federal government's unique and continuing trust relationship with and responsibility to the Indian people for the education of Indian children."124 Title 25 of the U.S. Code also refers to "the federal responsibility for and assistance to education of Indian children."125

Native Language Instruction

In prior decades, there were consistent calls to increase the use of native language instruction to increase cultural relevance and improve overall academic performance. One argument contends that language, culture, and identity are intertwined and thus are important to the tribal identity. A counter argument is that native language instruction detracts from the core curriculum. In recent years, Congress has expanded program authorities and appropriated funds to permit native language instruction.

There is not consensus in the research literature regarding the relative effectiveness of native language instruction. One commonly cited review of research studies with control groups, for instance, suggests that bilingual instruction in some instances was found to improve English reading proficiency in comparison to English immersion, but in other instances it had no impact. This review focused principally on studies conducted prior to 1996 and examining instruction for Spanish-speaking elementary school children, and many of the studies have limitations. The one study of Indian native language students included in the review found no significant difference in English reading outcomes between bilingual and English-immersion instruction.126 Some longitudinal studies prior to 2007 indicated that native language immersion students achieved higher scores on assessments of English and math than native students who did not receive native language immersion.127 However, a more recent review of the literature suggests that rigorous Native language and culture programs sustain non-English academic achievement, build English proficiency, and enhance student motivation.128

There are several federal programs that support native language acquisition: