Congressional Context

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA) and its affiliated health centers (called Planned Parenthood Affiliated Health Centers or PPAHCs) have been topics of debate within the 114th and 115th Congresses. Legislation in both the 114th and 115th Congresses has proposed federal funding bans that would range from one year to permanent.1 These discussions have raised questions about the services that PPAHCs provide and the availability of alternative facilities to provide similar services to disadvantaged populations.

In the 115th Congress, House Speaker Paul D. Ryan and Vice President Michael R. Pence informed the press that legislation to repeal and replace the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended) includes language that would ban federal funding that is made available to PPFA and PPAHCs.2 The resulting bill, H.R. 1628, the American Health Care Act of 2017 (AHCA), includes a one-year funding prohibition.3 The bill passed the House on May 4, 2017, and is currently under consideration in the Senate. AHCA's proposed funding moratorium would primarily apply to federal funds that PPFA receives from providing care to beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid, a federal-state health program. It is not clear how a ban would affect the overall operations of PPFA, because federal funding is only one source of PPFA's revenue. In addition, PPFA does not receive a direct appropriation.4

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has published costs estimates on the impact of defunding PPFA in AHCA and as part of efforts to repeal the ACA in the 114th Congress.5 This report summarizes these costs estimates. Both the current and older estimate are discussed because the CBO's discussion of the effects of PPFA defunding on access to care, undertaken to evaluate proposals in the 114th Congress, may still be instructive.

The earlier proposal is also discussed because the ACA repeal bill in the 114th Congress made explicit references to redirecting PPFA funds to federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), entities that receive federal grants to provide health care to underserved populations. Among other requirements, they must provide reproductive health services and must accept Medicaid.6 In particular, H.R. 3762—the ACA repeal bill that passed both the House and Senate in the 114th Congress—proposed that "All funds that are no longer available to Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. and its affiliates and clinics pursuant to this Act will continue to be made available to other eligible entities to provide women's health care services."7 H.R. 3134, which passed the House in the 114th Congress, would have defunded PPFA and would have reallocated federal funds to FQHCs. Those bills drew on CBO's estimate of the savings that the PPFA one-year ban would have created and then appropriated the same amount ($235 million) to FQHCs.8

The AHCA would appropriate an additional $422 million to FQHCs for FY2017. The language in H.R. 1628 does not explicitly link this new funding to the PPFA ban, but congressional leaders have made this link in their discussions of the bill. For example, Speaker Ryan noted that the bill would end funding for PPFA and send that money to community health centers.9 Similarly, Representative Kevin Brady, chairman of the House Committee on Ways and Means, also stated that the bill would defund PPFA and redirect funds to community health centers.10 The CBO score for AHCA estimates that a one-year ban would reduce direct spending by $156 million over the 10-year period of 2017-2026.11

FQHCs are one of many types of health care facilities that could provide care to Medicaid beneficiaries, but they may be particularly relevant for several reasons. First, federal law requires that all state Medicaid programs cover services provided at FQHCs for eligible beneficiaries.12 Second, FQHCs receive federal grants that require them to provide family planning (among other services) to Medicaid beneficiaries.13 As a result of Medicaid program requirements and the federal grants that FQHCs receive, the federal government may have leverage over FQHCs to direct their services, which it may not have over other types of providers, such as physicians in private practice. Consequently, recent legislation has focused on FQHCs as an alternative to PPAHCs.14

If Medicaid reimbursements were no longer available to PPAHCs, Medicaid beneficiaries would have several potential options. They could

- remain at the PPAHC and pay for services themselves or receive services paid for with nonfederal (e.g., state or donated PPFA) funds,

- receive services at another (non-FQHC) provider,

- obtain services at an FQHC, or

- no longer receive services.

Various factors may affect which of these options Medicaid beneficiaries would pursue. Access to health care varies by location, as health systems and options vary considerably across states and localities. In some areas, one facility may be as accessible as another and may provide (or may be able to begin to provide) the same set of services. In other areas, this may not occur because, for example, only one provider exists, either in general or for a particular service type. Moreover, facilities located in the same geographic area may not be equally accessible for patients, as one facility may be located near public transportation routes while another may not. Even in areas where one facility could provide the same services as another, these facilities may be challenged to do so in the short term because they may need to hire additional providers, acquire medical equipment, or construct additional exam rooms to be able to expand services.

Constraints in providing services in the short term may include factors that affect patient access to care. PPAHCs provide a narrow range of services to a more targeted population (i.e., family planning and related services to individuals of reproductive age), whereas FQHCs provide primary care, dental, and behavioral health services to individuals of all ages. As part of that mission, FQHC services do overlap with those provided by PPAHCs, but these services are not the focus of most FQHCs, whereas they are the focus of all PPAHCs. In addition, nearly all FQHCs have provider vacancies, which makes providing care to their current patient base challenging and may strain FQHCs' ability to absorb new patients.15 Given these issues, it is possible that a sudden influx of former PPAHC patients could strain FQHCs.16 Patient awareness and preferences are also relevant factors. For access to be maintained, patients need to be aware that provider alternatives exist that will meet their needs. Medicaid beneficiaries are not required to seek services at a particular provider, although some may be enrolled in managed care plans that may limit access to particular providers.17 Even in cases where Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care, they have a choice of where to seek family planning services as identified in their state's managed care contract. Given this, Medicaid beneficiaries who seek care at PPAHCs do so because PPAHCs are accessible and meet their needs or because there are not alternate accessible providers (e.g., because these providers will not accept Medicaid).18 PPAHCs, by specializing in family planning services, may be well-suited to meet their patients' needs as compared to a more generalized provider. For example, researchers have found that some patients prefer to use specialized family planning clinics, including PPAHCs, for family planning services, for a number of reasons, including that patients can receive longer-term contraceptive supplies.19

Organization of This Report

This report focuses on services that can be provided with federal funding, because recent policy debates discuss removing federal funding from PPFA while attempting to maintain the services that the federal government would otherwise have paid PPFA to provide. Given this focus, this report contains only a limited discussion of abortion services because federal funds are generally not available to pay for abortions, except in cases of rape, incest, or endangerment of the mother's life.20

For one health facility to begin to provide services to patients that had previously been seen at a different facility, one could argue that the receiving facility should

- provide similar services,

- serve a similar population, and

- be located in a similar geographic area.

This report is organized around these three dimensions and presents national-level data for both PPAHCs and FQHCs. The report makes a number of comparisons using national-level data; although national-level data are the best data available, health care varies by locality and national data obscure local variation. In some cases, the national data available for PPAHCs and FQHCs vary; FQHCs are required to report a number of data elements because they receive federal grants for their overall operations. In contrast, PPAHCs may be required to report certain services they provide as a condition of receiving a particular type of grant, but do not have similar overall reporting requirements.

As such, comparisons in this report are limited by the data available. These comparisons are also limited because the reporting years for PPFA and FQHCs differ. Specifically, FQHCs report data on calendar years or based on the federal fiscal year (October 1-September 30). PPFA's annual reports include data that cover different time periods. Their revenue data cover the PPFA fiscal year—July 1 through June 30—while service data are presented in calendar year or the federal fiscal year. The report then discusses CBO cost estimates for AHCA and for legislation considered in the 114th Congress that would have enacted a one-year ban on federal Medicaid funds being provided to PPFA and PPAHCs. As noted, the cost estimates in the 114th Congress provide additional analyses on the effects of a PPFA ban on Medicaid beneficiaries that may be useful for evaluating AHCA and other efforts to restrict funding to PPFA in the 115th Congress. Finally, the report concludes with a discussion of some published research that examines the effects of state funding restrictions to PPAHCs on women's health.

Comparison of PPAHCs and FQHCs

In comparing PPAHCs and FQHCs, it is important to understand that they are not equivalent entities. Both are outpatient clinics, but they vary in size and the scope of services offered. There are fewer PPAHCs and a central body (the PPFA affiliate) decides where to locate facilities. In addition, these facilities are more coordinated with each other than are FQHCs. A patient who receives services at one PPAHC can expect similar services, organization, and standards followed at a different PPAHC.21 In contrast, FQHCs are more numerous, but are generally independent from one another and have no central governing body. FQHCs also receive federal grants for their operations and must be located in a medically underserved area (or serve a medically underserved population) as a condition of receiving those grants. PPAHCs do not receive federal grants for general facility support and do not have location requirements. Both entities may receive reimbursements from federal health programs for providing services to enrolled beneficiaries. Both facility types report that Medicaid is their largest source of federal revenue. In addition, both PPAHCs and FQHCs may compete and receive grants from federal grant programs for which they are eligible.

PPAHCs and FQHCs have different goals and orientations. PPAHCs focus on providing family planning and related services to individuals of reproductive age (15-44 years), whereas FQHCs' focus is to provide more comprehensive services to individuals throughout an individual's lifespan. Although there is some overlap, their focus is different. Information about both facility types is provided below, using the most recent and consistent data available.

Planned Parenthood Affiliated Health Centers (PPAHCs)

PPFA is the umbrella organization supporting 59 independent affiliates that operate 661 health centers across the United States (called PPAHCs), according to their 2014-2015 annual report.22 Affiliates generally oversee PPAHCs in a geographic area ranging from parts of states to several states. Although consistent data are not available in each year, it appears that the number of affiliates and facilities has declined since 2009-2010, when PPFA reported having 88 affiliates (a 32% decline) and 840 health centers (a 22% decline).23 PPFA, as a result of its internal policies, provides discounted services to individuals who cannot afford to pay; it also helps patients enroll in federal and state programs (e.g., Medicaid) when patients meet the program's eligibility criteria. PPAHCs that receive federal funds from the Title X Family Planning Program must also provide discounted contraception services.24

Federal Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)25

FQHCs are outpatient facilities that focus on primary care and receive federal grants—authorized under the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) Section 330—for general support of their facilities. Section 330 grants are administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These grants are awarded competitively with some preference given to sites in rural areas. In addition to supporting operations, Section 330 grants can be used to expand services and, in limited cases, to construct facilities.26 Most FQHCs are independently operated, although some may be affiliated and some FQHCs operate multiple sites. As of March 6, 2017, there were 10,560 FQHC delivery sites.27 The number of FQHC delivery sites has increased by 32% since 2009. Part of this increase is due to the creation of a multi-billion-dollar Community Health Center Fund in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).28 The ACA's investment in FQHCs was an attempt to provide access to care for those who gained insurance coverage under the ACA. FQHCs have served as a provider for those who gained insurance (including those who became eligible for Medicaid), but in some cases researchers have found that FQHCs have longer wait times for new appointments for Medicaid patients than do other types of facilities.29

Community health centers are the most common type of FQHC because they provide care to a generally underserved population. Section 330 grants also support three other FQHC types: (1) health centers for the homeless; (2) health centers for residents of public housing; and (3) migrant health centers, each of which serve a more targeted population than do community health centers. No PPAHCs currently receive Section 330 grants.

As a condition of receiving a Section 330 grant, FQHCs are required to provide services to the entire population of their designated service area, regardless of an individual's ability to pay. To do so, health centers establish a discounted fee schedule (i.e., sliding-scale fees), which is then further discounted or waived based on a patient's ability to pay, as determined by the patient's income relative to the federal poverty level30 and the patient's family size.31 FQHCs are also required to coordinate with state Medicaid programs to provide care to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Section 330 grantees are designated as FQHCs for purposes of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. This designation entitles them to receive higher reimbursement rates for providing services to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Specifically, FQHCs receive higher payment rates than physicians' offices or other outpatient facilities without that designation (e.g., PPAHCs) for providing the same services. The FQHC payment designation was created because FQHCs provide additional supportive services that are generally not reimbursed by insurance. The higher payment rates are also intended to minimize the use of Section 330 grant funds to subsidize Medicare and Medicaid patients receiving services at FQHCs.32

Revenue Sources

PPFA Revenue Sources

PPFA is a not-for-profit organization that receives nonfederal and federal funds for its operations. It receives grants (federal and nonfederal), donations, patient fees, and reimbursements including those received for providing services to patients enrolled in government health care programs (e.g., Medicaid).33 Federal funds are only available when PPFA provides services that are covered by the applicable federal program. Federal funds are generally not available to pay for abortions, except in cases of rape, incest, or endangerment of a mother's life.34

For their fiscal year that ended June 30, 2015 (referred to as 2014-2015 data in this report), PPFA and its affiliates reported total revenue of $1.29 billion. The largest source ($553.7 million, or 43%) was from government reimbursements received from government programs for health services provided (e.g., Medicaid) and grants (e.g., the Title X Family Planning Program).35 This category included funds from federal, state, and local governments. For example, it includes both state and federal shares of Medicaid reimbursements for covered services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries.36 See Table 1.

|

2013-2014 |

2014-2015 |

|||

|

Millions of Dollars |

Percent of Total Revenue |

Millions of Dollars |

Percent of Total Revenue |

|

|

Government Health Services Grants and Reimbursements |

$528.4 |

41% |

$553.7 |

43% |

|

Private Contributions and Bequests |

$391.8 |

30% |

$353.5 |

27% |

|

Nongovernment Health Services Revenue |

$305.3 |

23% |

$309.2 |

24% |

|

Other operating revenue |

$77.9 |

6% |

$79.7 |

6% |

|

Total |

$1,303.4 |

100% |

$1,296.1 |

100% |

Source: Planned Parenthood Federation of America Inc., 2014-2015 Annual Report, pp. 32-33, https://www.plannedparenthood.org/files/2114/5089/0863/2014-2015_PPFA_Annual_Report_.pdf.

Notes: The category "Government Health Services, Grants, and Reimbursements" includes federal, state, and local funding. PPFA reports revenues for the year ending on June 30; for example, the "2014-2015" sources of revenue are for the year ending June 30, 2015.

According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and CBO, Medicaid reimbursements for providing services to covered beneficiaries are the largest source of government revenue for PPFA. In a study of 2012 revenue, GAO found that PPFA affiliates reported $400.56 million in Medicaid reimbursements (including both federal and state dollars).37 In a 2015 cost estimate, CBO estimated that PPFA received $390 million in annual federal and state Medicaid reimbursements, making these reimbursements the largest source of federal support for PPFA.38

PPFA also receives funds from government grant programs, either as a direct grantee or through a state or another organization. The largest source of federal grant support, according to GAO's analysis of FY2012 data, was the Family Planning Program under Title X of the Public Health Service Act, with PPFA affiliates spending $64.35 million in Title X funding in FY2012 (see text box).39 Title X grantee data from August 2016 indicate that 15 PPFA affiliates are among the current Title X grantees.40 PPAHCs also receive Title X funds indirectly through contracts with other grantees (i.e., state agencies); more than 350 PPAHCs are included in the database of Title X sites.41 The Guttmacher Institute found that in 2010, PPAHCs made up 13% of Title X clinics, but served 37% of Title X clients.42

|

Title X Family Planning Program The Title X Family Planning Program—authorized in Title X of the Public Health Service Act—provides grants to public and nonprofit agencies for family planning services, research, and training. No Title X funds can be used to pay for abortions. The Title X program funds more than 4,000 service sites. Entities that receive Title X grants are required to comply with program rules, which include providing discounted services, providing a range of family planning services, and ensuring client confidentiality, in particular when providing services for adolescents or young adults. Some Title X clients have dependent health coverage through a parent's or partner's private health insurance policy. However, for confidentiality reasons, they may not wish to bill family planning or STD services to that policy. According to HHS, Title X clinics "commonly forgo billing" health insurers in order to maintain confidentiality. Confidentiality is a common reason cited by women when asked why they choose specialized family planning clinics over other providers. Sources: 42 U.S.C. 300a-6; CRS Report RL33644, Title X (Public Health Service Act) Family Planning Program, by [author name scrubbed]; CRS In Focus IF10051, Title X Family Planning Program, by [author name scrubbed]; Jennifer J. Frost, Rachel Benson Gold, Lori Frohwirth, et al., Variation in Service Delivery Practices Among Clinics Providing Publicly Family Planning Services in 2010, Guttmacher Institute, May 2012, https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/clinic-survey-2010.pdf; and HHS, Office of Population Affairs, FY14 Announcement of Availability of Funds for Family Planning Affordable Care Act (ACA) Impact Analysis Research Cooperative Agreements, March 7, 2014, pp. 5-6, 10-11, https://www.grantsolutions.gov/gs/preaward/previewPublicAnnouncement.do?id=49223. |

In addition to Medicaid reimbursements and Title X Family Planning Program grants, GAO found, in FY2012, that PPFA affiliates expended funds from other HHS programs, as well as programs administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Agriculture. PPFA received some of these funds directly from federal agencies, and some indirectly as sub-awards passed through state agencies or other federal grantees.

It should be noted that GAO's data are from FY2012. Data are not available to assess whether the programs that provided funding to PPFA affiliates in FY2012 are currently providing funds to PPFA affiliates. For example, a number of the federal programs that had provided funds to PPFA in FY2012 are competitive grant programs. A competitive grant that was active in FY2012 may have ended subsequently, a PPFA affiliate may have chosen not to apply for a particular program, or a PPFA affiliate may not have competed successfully for funds. Furthermore, a number of programs from which PPFA affiliates received funds in FY2012 were block grants to states (e.g., Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant). A state may choose not to contract with PPFA for a particular service, choosing to use a different entity to provide that service. Conversely, PPFA affiliates may have successfully competed for grant programs active since FY2012 or may have begun to contract with states when they previously have not done so.43 Data are not available on the extent to which such situations have occurred since FY2012.

FQHC Revenue Sources

FQHCs receive both federal and nonfederal funds. Available data on FQHC revenue are aggregate program-level data; the revenue sources of any individual FQHC may vary. FQHCs generally receive two types of federal funds—reimbursements and grants. For FY2016, FQHCs had total revenue of $23.4 billion (see Table 2). The largest source of revenue (42.2%) was reimbursements from Medicaid, which provided roughly twice the support provided by Section 330 grants (21.7%). Medicaid reimbursements may be particularly important because FQHCs receive higher payments rates than do other outpatient provider types by being designated as an FQHC.44 FQHCs also receive grants from other government programs. For example, Title X grantee data from August 2016 indicate that there is one FQHC among the current Title X grantees.45 FQHCs also receive Title X funding through state agencies (or other entities) that serve as the primary program grantee. In 2010, researchers found that FQHCs administer 38% of Title X clinics and serve 16% of overall Title X clients.46 This percentage may have changed given that fewer FQHCs are direct Title X grantees in more recent years and the number of FQHCs receiving funds from a state grantee may have changed. State grantee data are not available to assess whether such changes have occurred.

|

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

||||

|

Millions of Dollars |

Percent of Program Revenuea |

Millions of Dollars |

Percent of Program Revenuea |

||

|

Section 330 Authorized Grants |

|||||

|

Section 330 Grants |

$4,210 |

19.7% |

$5,091 |

21.7% |

|

|

Subtotal (Section 330 authorized grants) |

$4,210 |

19.7% |

$5,091 |

21.7% |

|

|

Reimbursements |

|||||

|

Medicaid |

$8,910b |

41.7% |

$9,870 |

42.2% |

|

|

CHIPc |

$320 |

1.5% |

$255 |

1.1% |

|

|

Medicare |

$1,235 |

5.8% |

$1,300 |

5.6% |

|

|

Other third party payers (e.g., private insurance) |

$2,130 |

10.0% |

$2,100 |

9.0% |

|

|

Patient Feesd |

$1,045 |

4.9% |

$1,100 |

4.7% |

|

|

Subtotal (Reimbursements) |

$13,640 |

63.8% |

$14,625 |

62.5% |

|

|

Other Federal Grants |

|||||

|

Other Federal Grants |

$445 |

2.8% |

$445 |

1.9% |

|

|

Subtotal (Other Federal Grants) |

$445 |

2.8% |

$445 |

1.9% |

|

|

State, Local, and Private Grants and Contracts |

|||||

|

State, Local, Other |

$3,090 |

14.4% |

$3,250 |

13.9% |

|

|

Subtotal (State, Local, and Private Grants and Contracts) |

$3,090 |

14.4% |

$3,250 |

13.9% |

|

|

Total (all sources) |

$21,385 |

100% |

$23,411 |

100% |

|

GAO also examined federal funding made available to FQHCs. According to GAO, in FY2012, FQHCs received federal grants from programs administered by the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Housing and Urban Development, and Interior, and by the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Science Foundation.47 GAO also found that, in addition to the HRSA grants that FQHCs receive to operate facilities, they also receive grants, cooperative agreements, and contracts from programs administered by other HHS agencies.48

Health Care and Medical Services

PPAHCs and FQHCs both provide outpatient and preventive services. However, their service focus differs: PPAHCs focus on family planning services, and FQHCs focus on general primary care. There are many more FQHCs than there are PPAHCs; thus FQHCs provide far more services in a given year than do PPAHCs.49 However, despite the fact that there are nearly 15 times the number of FQHCs than there are PPAHCs, FQHCs in total provide fewer contraceptive services than do PPAHCs. Specifically, PPAHCs provided 2.9 million contraceptive services in 2014-2015 while FQHCs provided 1.3 million of these services in calendar year 2015. In addition, each individual FQHC provides far fewer contraceptive services than does the typical PPAHC. In an analysis that CBO requested, the Guttmacher Institute examined 2010 data and found that the average FQHC saw 330 contraceptive clients per year; in contrast, the average PPAHC saw 2,950 contraceptive clients per year.50

The data discussed below are aggregate data; as such, individual facilities may provide different services. Comparisons of these data may be limited because PPAHCs and FQHCs define services differently and FQHCs do not report all services provided. Specifically, PPFA defines a service as "a discrete clinical interaction, such as the administration of a physical exam or STI test or the provision of a birth control method."51 FQHCs, in contrast, only require their facilities to report providing selected services and derive their data based on diagnoses included in patient records.52 Thus FQHC data undercount total services provided.

These data also represent total services provided and do not indicate who received or who paid for these services (e.g., these data do not indicate the number and type of services that Medicaid beneficiaries received at either of these facility types). Finally, these data show services regardless of whether they were paid for with federal funds.

Services Provided by PPAHCs

PPAHCs provide a range of contraceptive services and nearly all PPAHCs stocked common contraceptive methods.53 When compared to other provider types, 99% of PPAHCs provided at least 10 reversible contraceptive methods on site as compared to 71%-81% of other provider types.54 In recent years, medical guidance has shifted to recommending long-acting reversible contraceptives called LARCs (e.g., IUDs) to women who do not want to become pregnant within two years.55 Researchers have found that LARCs are "20 times more effective than oral contraceptive pills."56 Nearly all PPAHCs (96%-98%) both stocked LARCs and were able to provide patients with same-day insertion. In contrast, researchers found that 75% of public-funded clinics that offered family planning services were able to offer any requested LARC method on-site.57

PPFA data on services provided are not available consistently over time. In addition, PPFA data do not specify the type of contraceptive method provided, which could affect the number of visits needed. For example, more women opting for LARCs in more recent years should decrease the need for subsequent patient visits. Given these data constraints, it is difficult to compare how services provided have changed. However, for some comparison, Table 3 shows services reported in PPFA's annual reports for 2009-2010 (i.e., calendar year 2010) and 2014-2015 (i.e., FY2014).58 In 2009-2010, PPFA provided an estimated 11.0 million services; in contrast, in 2014-2015, PPFA provided an estimated 9.4 million services. The data in Table 3 represent those services provided overall by PPAHCs; some facilities may not provide all of these services (e.g., some facilities do not provide abortion services), and some facilities may have a different distribution of services provided.

Table 3 shows that the percentage of services related to testing or treating sexually transmitted infections/sexually transmitted diseases (STI/STD) has increased. Services related to STI/STD are the most common service provided at PPAHCs in both time periods. The share of contraceptive services compared to all services remained relatively stable comparing the two time periods. The percentage of services classified as cancer screenings declined from the 2009-2010 report to what was reported in the 2014-2015 annual report. In the intervening years, expert recommendations for cancer screenings changed; it is possible that this change could explain the decline, but PPFA data are not specific enough to determine this.59 In both years, abortion services comprised 3% of PPFA services. This translates to 323,999 abortions in 2014-2015 and 329,445 abortions in 2009-2010.60 For context, a national study of abortion providers found that 926,200 abortions were performed in 2014.61 As noted above, the data on services represent all services provided by PPAHCs and are not differentiated by payer. Federal funds may only be used to pay for abortions in cases of rape, incest, or endangerment of a mother's life.62

|

Service |

2009-2010a |

Percentage of Servicesb |

2014-2015c |

Percentage of Servicesb |

|

STI/STD Testsd |

4,179,053 |

38% |

4,218,149 |

45% |

|

Contraception |

3,685,437 |

34% |

2,945,059 |

31% |

|

Cancer Screening and Prevention |

1,596,741 |

15% |

682,208 |

7% |

|

Other Women's Health Servicese |

1,144,558 |

10% |

1,190,408 |

13% |

|

Abortion Servicesf |

329,445 |

3% |

323,999 |

3% |

|

Other Servicesg |

68,132 |

1% |

95,759 |

1% |

|

Total Services |

11,003,366 |

100% |

9,455,582 |

100% |

Sources: Planned Parenthood Federation of America Inc., 2014-2015 Annual Report, pp. 32-33, https://www.plannedparenthood.org/files/2114/5089/0863/2014-2015_PPFA_Annual_Report_.pdf and Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Annual Report 2009-2010, http://liveaction.org/research/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/2009-2010-Planned-Parenthood-Annual-Report.pdf.

Services Provided by FQHCs

FQHCs, as a condition of receiving a HRSA grant, are required to provide primary, preventive, and emergency health services.63 Primary health services are those provided by physicians or physician extenders (physicians' assistants, nurse clinicians, and nurse practitioners) to diagnose, treat, or refer patients.64 Primary health services include relevant diagnostic laboratory and radiology services. Preventive health services include well-child care, prenatal and postpartum care, immunization, voluntary family planning, health education, and preventive dental care. Emergency health services refer to the requirement that health centers have defined arrangements with outside providers for emergent cases that the center is not equipped to treat and for after-hours care. FQHCs can provide additional services; however, these services must be in addition to, and not in lieu of, the required services. In addition to these three types of services (primary, preventive, and emergency), health centers must provide diabetes self-management training for patients with diabetes or renal disease.65

FQHCs are required to report the provisions of certain services to HRSA for the agency to evaluate the program's effectiveness.66 The services reports are generally related to primary and preventive care including cancer screenings. Because only subsets of services are reported, there are limited data on the total number of services that FQHCs provide. However, the number of these selected primary and preventive care services has increased over time. In 2015, FQHCs provided 20.6 million medical services, based on the subset of medical services that FQHCs report. This was an increase from the 16.2 million selected medical services provided in 2009. This increase primarily occurred because of the program's ACA funding expansion.67 Of the selected services reported, some are similar to those provided at PPAHCs; these services are reported in Table 4. In 2015, services provided related to reproductive health (i.e., STD/STI treatment and prevention, contraception, and cancer screening and prevention) were about one-third (6.9 million) of the selected medical services provided at FQHCs.

|

Service |

2009 |

Percentage of Selected Services Provided |

2015 |

Percentage of Selected Services Provided |

|

STI/STD Testing & Treatment |

||||

|

HIV Tests |

691,280 |

2.4% |

1,297,113 |

4.3% |

|

Hepatitis B Test |

N/A |

N/A |

436,665 |

1.4% |

|

Hepatitis C Test |

N/A |

N/A |

527,431 |

1.7% |

|

Contraception |

||||

|

Contraceptive Management |

1,072,413 |

3.8% |

1,384,635 |

4.6% |

|

Cancer Screening and Prevention |

||||

|

Mammograms |

320,456 |

1.1% |

521,568 |

1.7% |

|

Pap Tests |

1,840,570 |

6.5% |

1,863,957 |

6.1% |

|

Prenatal Care |

||||

|

Prenatal Patients |

480,441 |

1.7% |

552,150 |

1.8% |

|

Prenatal Patients who Delivered |

N/A |

N/A |

292,286 |

1.0% |

|

Totals |

||||

|

Total (Selected Reproductive Health Related Services) |

4,405,160 |

19.4% |

6,875,805 |

22.6% |

|

Total (Selected Medical Services Reported to HRSA) |

16,166,416 |

71.1% |

20,616,149 |

67.8% |

|

Total (All Selected Services)a |

22,723,910 |

100% |

30,391,588. |

100% |

Source: HRSA, Uniform Data System (UDS), National Report, various years, at http://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacomparisons.aspx.

Notes: The data reported above are for selected services that FQHCs provide. Data are reported for each calendar year and they do not represent the entirety of services provided by FQHCs. N/A means that data were not available; it does not indicate that the service was not provided in a particular year.

As mentioned above, FQHCs provide voluntary family planning services as part of their required services. In cases when an FQHC receives a Title X Family Planning Program grant (either directly or through the primary grantee), the facility is subject to the Title X program's confidentiality policies—including policies related to forgoing billing for services to maintain confidentiality.68 FQHCs that do not receive these grants are not required to maintain similar confidentiality policies.

Some recent research suggests that not all FQHCs provide comprehensive family planning services and that this is more likely the case at smaller FQHCs.69 Surveys have found variation in how frequently FQHCs provide specific contraceptive methods. For example, one study found that 36% of FQHCs offered on-site contraceptive implants.70 Another study found that 37% offered on-site refills of oral contraception.71 Other research focusing on LARCs found variation in their availability. They found that slightly more than half of FQHCs provided IUDs, but more than more than 90% provided three-month injectables.72

Comparisons of Services Provided by PPAHCs and FQHCs

The relative scope of services provided by PPAHCs and FQHCs differs. Even in categories where services are comparable, there are some key differences worth noting. FQHCs provide more limited contraception services, particularly in terms of methods available.73 In 2015, more than two-thirds of FQHCs (71%) provided access to at least 10 reversible contraceptive methods compared to 99% of PPAHCs.74 This may be particularly important because recent research suggests that providing access to a comprehensive mix of contraceptive methods, and counseling patients on the differences between various options, reduced rates of unintended pregnancy, unintended births, and abortions.75

Researchers have also examined services at FQHCs and PPAHCs and found differences in how they deliver the same services. FQHCs tend to provide shorter-term prescriptions for oral contraceptives than do PPAHCs.76 Although both FQHCs and PPAHCs that receive Title X funding are more likely to offer a range of contraceptives than do those that do not receive Title X funding, PPAHCs overall (i.e., regardless of Title X funding status) are more likely to provide LARC on-site than any other type of clinic; 98% compared to a range of 69% to 77%.77 PPAHCs are also more likely to provide LARC insertion as a same-day service; 98% of PPAHCs surveyed in 2010 were able to offer same-day insertions compared to 87% of FQHCs that were able to do so.78 A survey of clinics in 2015 found that 98% of PPAHCs offer any LARC method compared to 69% of FQHCs, and that the overall percentage of clinics stocking any LARC had increased from 66% in 2010 to 75% in 2015.79 Differences related to offering LARCS (at all or a particular type) may be important to Medicaid patients because, in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)—the agency that administers the Medicaid program—released policy guidance to state Medicaid programs that included ways to improve access to LARCs for Medicaid beneficiaries.80

In addition, FQHCs, unless they also receive Title X grants, may have less developed confidentiality policies than do PPAHCs or other types of Title X family planning clinics.81 In particular, FQHCs are required to seek outside reimbursements, so they may not forgo billing in order to maintain confidentiality, like many Title X clinics do.82

Regarding cancer screening, FQHCs provide more radiological services, including mammograms, than do PPAHCs. This may reflect the age of the patients served, as routine mammograms are not recommended for younger women,83 the dominant population served by PPAHCs. Also, facilities offering mammography must meet certain requirements under the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA).84 Often it is not cost effective or feasible for smaller clinics, such as PPAHCs, to meet these requirements. These clinics instead refer their patients to other providers for mammography.

Another difference is that some PPAHCs provide abortion services and do so in instances where government funds would not be available for reimbursement; FQHCs generally do not provide abortion services. Abortion services would be outside of the scope of the health center grant and would have to be approved by an individual FQHC's governing board. In addition, these services cannot be supported with the health center's grant so would have to be financially self-sustaining. Given that many health center patients have limited ability to pay for services and that there are limited sources of reimbursement for abortions, it is likely that few health centers are performing abortions.85

Population Served by PPAHCs and FQHCs

In 2013, PPAHCs reported seeing 2.7 million patients. Of those, 78% had incomes at or below 150% of the federal poverty level, and approximately 60% were either enrolled in Medicaid or were accessing services through the Title X Family Planning Program, which provides free or discounted family planning services.86 PPAHCs also serve a diverse population. In 2014, approximately one-quarter (23%) of the population served was Latino and 15% was African American.87 Although PPAHCs are primarily thought of as women's health providers, they have increased the number of men served, primarily for STI/STD related services, in recent years, although no specific numbers are available.88 PPFA facilities serve some adolescents; however, PPFA reports that 84% of the patients seen in 2014 were 20 years old or older.89

The data available on the FQHC service population are more extensive than those available for PPAHCs. Overall, FQHCs have increased the number of patients seen in each year since 2009. The total number of patients increased from 2009 to 2015, growing from 18.9 million patients seen in 2009 to 24.3 million in 2015. Like PPFA, FQHCs report serving a low-income population; for example, more than half of all patients served report having incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level. In addition, nearly half of FQHC patients are enrolled in Medicaid or the State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP).90

The FQHC service population is also diverse. Over half of all patients served are nonwhite (see Table 5). FQHCs serve the population throughout their lifespan; for example, approximately one-third of patients are children. This contrasts to PPAHCs, which focus on providing services for patients of reproductive ages (i.e., ages 15-44).91

Table 5. Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics of FQHC Patients (2009-2015)

(expressed as percentage of total patients)

|

Patient Demographics |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

Income as Percent of Poverty Level |

|||||||

|

100% and Below |

54 |

55 |

55 |

55 |

54 |

53 |

52 |

|

101%-150% |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

|

151%-200% |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

Over 200% |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

|

Unknown |

25 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

|

Gender |

|||||||

|

Female |

59 |

59 |

59 |

59 |

59 |

58 |

58 |

|

Male |

41 |

41 |

41 |

41 |

41 |

42 |

42 |

|

Age |

|||||||

|

0-17 |

33 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

31 |

31 |

|

Age |

|||||||

|

18-64 |

60 |

61 |

61 |

61 |

61 |

61 |

61 |

|

65 and older |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

8 |

8 |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

|||||||

|

Non-Hispanic White |

48 |

51 |

53 |

43 |

42 |

42 |

41 |

|

Hispanic/Latino |

35 |

34 |

35 |

34 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

|

Black/African American |

27 |

26 |

25 |

24 |

24 |

23 |

23 |

|

Asian |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

American Indian/Alaska Native |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

More than one race |

5 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

Source: CRS analysis of HRSA's Uniform Data System National reports, various years.

Note: Percentages may be greater than 100%.

Locations of PPAHCs and FQHCs

PPFA affiliates are independent organizations and may choose the location of their facilities. PPFA reports that the majority of PPAHCs are located in health professional shortage areas (HPSAs), medically underserved areas (MUAs), or rural areas (see text box).92 Unlike PPAHCs, FQHCs have location requirements. Specifically, they are required to be located in MUAs or serve a medically underserved population, which are automatically designated as HPSAs (see text box). Like PPAHCs, FQHCs can be located in either urban or rural areas.

|

Health Professional Shortage Areas and Medically Underserved Areas/Populations Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs): Areas—rural or urban—with provider shortages in primary medical care, dental, or mental health. Specific population groups (e.g., populations with unusually high needs for health services, as indicated by measures such as the poverty rate and the infant mortality rate) and specific facilities (e.g., a community health center, or a facility operated by the Indian Health Service) may also be designated as HPSAs. The HPSA designation is made based on ratios of provider per population where specified ratio changes based on the type of HPSA (e.g., primary care or mental health). For example, an area may be designated a primary care HPSA if it has a full-time equivalent primary care physician ratio of at least 3,500 patients for each primary care physician or has a ratio of between 3,500 to 3,000 patients for each primary care physician and has a population with high health care needs. Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs): Areas of varying size—whole counties, groups of contiguous counties, civil divisions, or a group of urban census tracts—where residents have a shortage of health care services. Source: Health Resources and Services Administration, Shortage Designation: Health Professional Shortage Areas & Medically Underserved Areas/Populations, at http://www.hrsa.gov/shortage/index.html. |

As noted earlier there are far fewer PPAHCs (661) than FQHCs (10,560). However, there is some overlap in the location of PPAHCs and FQHCs. Table 6 shows that 352 counties had both a PPAHC and an FQHC in 2016. It also shows that nearly two-thirds (61.6%) of U.S. counties have an FQHC, while only 8.7% have a PPAHC. Approximately half of all U.S counties have an FQHC, but not a PPAHC, and approximately one-third of U.S. counties have neither facility type. As discussed, FQHCs must be located in shortage areas or serve a shortage population; this location requirement may explain why some counties do not have an FQHC. Table 6 presents data on the number of counties that have either a PPAHC or an FQHC, or both facility types.

|

County or County Equivalentsa |

2015 Count |

2015 Percentage |

2016 Count |

2016 Percentage |

|

Counties or county equivalents with a PPAHC |

393 |

12.2% |

8.7% |

|

|

Counties or county equivalents with more than one PPAHC |

108 |

3.3% |

105 |

3.2% |

|

Counties or county equivalents with an FQHC |

1,912 |

59.1% |

1,992 |

61.6% |

|

Counties or county equivalents with more than one FQHC |

1,185 |

36.7% |

1,246 |

38.5% |

|

Counties or county equivalents with a PPAHC and an FQHC |

358 |

11.1% |

352 |

10.9% |

|

Counties or county equivalents with a PPAHC, but not an FQHC |

37 |

1.1% |

30 |

0.9% |

|

Counties or county equivalents with an FQHC, but not PPAHC |

1,546 |

47.8% |

1,640 |

47.8% |

|

Counties or county equivalents without a PPAHC or an FQHC |

1,272 |

39.3% |

1,192 |

36.9% |

|

Counties or county equivalents in the United States |

3,233 |

N/Ab |

3,233 |

N/Ab |

Source: CRS analysis of geocoded PPFA and HRSA data.

a. Of the 50 U.S. states, 48 states are divided into a total of 3,007 counties. Louisiana is divided into 64 parishes, which are considered to be county equivalents and are included in the county estimates in the table. Similarly, Alaska is divided into 19 organized boroughs and one unorganized borough. These data are also included in this table as county equivalents. Several states also have independent cities, which are not considered parts of counties; these are also considered to be county equivalents in the table. In total, the table includes 3,233 counties or county equivalents. See U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 Tiger/Line Shapefiles: Counties (and equivalent), http://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2016&layergroup=Counties+%28and+equivalent%29.

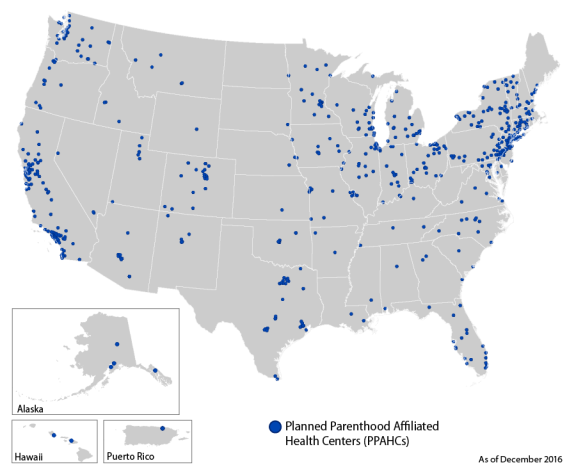

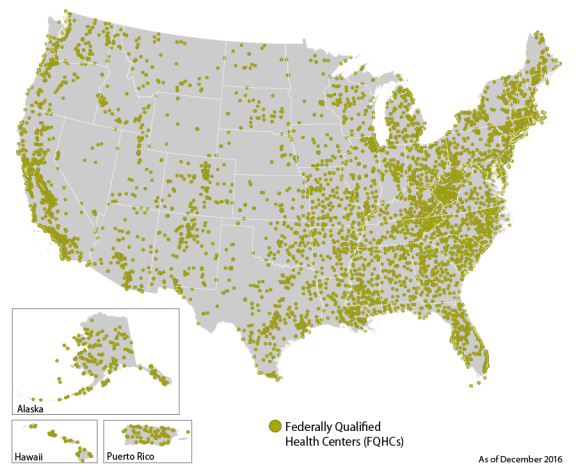

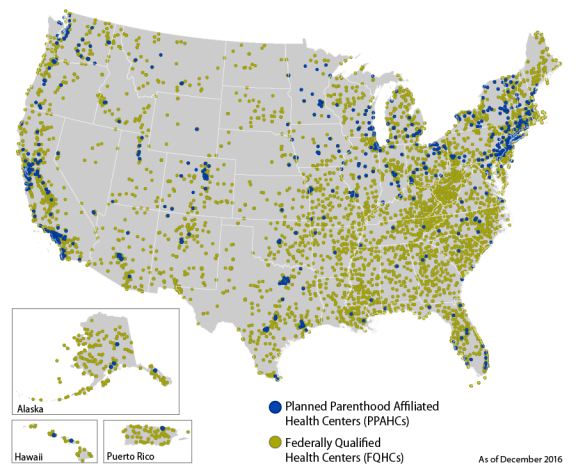

Figure 1 and Figure 2 below present the location of PPAHCs and FQHCs on separate maps; a third map (Figure 3) presents both facilities together. These maps present only a portion of the health services available in any particular area; as such, they are not sufficient to infer meaningful information about the local health care system. For example, they do not include hospitals, other inpatient facilities, or physician offices. Nor do these maps include all federally supported health services in a particular area; for example, the maps do not include facilities funded by the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the Indian Health Service. Notably, these maps also do not include Title X clinic sites, which provide family planning and other services that overlap with PPAHCs and FQHCs.

Figure 1 presents a map of PPAHCs. These appear to be more common in the Northeast and on the West Coast.

|

Figure 1. Planned Parenthood Affiliated Health Centers (PPAHCs) |

|

|

Source: CRS Analysis of Planned Parenthood Sites from http://www.plannedparenthood.org. Note: The clinic pictured in Puerto Rico is an affiliate of the International Planned Parenthood Federation. |

The second map presents the location of FQHCs, which are widely distributed throughout the United States (see Figure 2).

|

|

Source: CRS Analysis of HRSA data. Note: Some of the U.S. territories (not pictured) also have FQHCs. |

The final map presents both FQHCs and PPAHCs, illustrating that these facilities are often, but not always, located in similar locations. The map also shows that some areas have neither facility type (see Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. Planned Parenthood Affiliated Health Centers (PPAHCs) and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) |

|

|

Source: CRS Analysis of Planned Parenthood Sites from http://www.plannedparenthood.org and analysis of HRSA data. Notes: In high density areas, facilities may overlap and both facilities may not be visible on the map. Some of the U.S. territories (not pictured) are served by the International Planned Parenthood Federation and also have FQHCs. The PPAHC pictured in Puerto Rico is an affiliate of the International Planned Parenthood Federation. |

Comparisons of Locations of PPAHCs and FQHCs

As noted, PPAHCs are a less numerous facility type than are FQHCs; as such, there are areas where the loss of access to a PPAHC for Medicaid beneficiaries may have less of an impact because there is currently no PPAHC in that location. Conversely, the map also shows that there are areas where there are both PPAHCs and FQHCs; this may indicate that FQHCs could provide care to PPAHC patients, but the maps do not show whether these facilities are as accessible at a local level to patients. The maps also show that there are areas where there are PPAHCs with no nearby FQHC; patients in these areas may be more affected by a reduction in services or the loss of the ability to use Medicaid at a PPAHC. As noted, these maps do not show other health care facilities in an area that may be able to absorb additional patients. The maps also do not indicate whether a similarly located facility is as accessible to patients. For example, one facility may be located near public transportation, while another facility may not be. As such, being located in the same area may not be sufficient to serve as an alternate provider to patients.93

CBO Cost Estimates of PPFA-Related Legislation Considered in the 114th Congress

The potential effects of imposing a ban on federal funding to PPFA are uncertain. This section discusses the findings of a series of cost estimates undertaken by the CBO that examined the effects of a short- or long-term prohibition on federal funds going to PPFA. CBO stated that it did not have the basis to evaluate the effects of a ban on federal funding on the operations of PPFA or any individual PPAHC; instead, it focused its estimates on the costs to the federal government and access to care. CBO also noted that its estimates were highly uncertain and focused primarily on Medicaid, because CBO assumed that discretionary grants—such as those awarded through the Title X Family Planning Program—could be reallocated to other providers.94

In its estimate of the AHCA, CBO estimated that the funding prohibition would reduce direct federal spending by $178 million in FY2017 and $234 million over the 2017-2026 time period. CBO noted that these savings were partially offset by increased spending primarily for births that would be paid for by Medicaid because some women who were using PPAHCs for family planning services would lose access to care, forgo services, and become pregnant. CBO estimated that this prohibition would result in several thousand additional births, which would increase Medicaid spending by $21 million in FY2017 and $77 million over the 2017-2026 time period. Overall, CBO estimates that the net savings generated by the PPFA ban would be $156 million. CBO also estimated that, as a result of the PPFA funding prohibition, 15% of people who use Medicaid at PPAHCs would lose access to care.

In analyses of bans considered in the 114th Congress, CBO provided more comprehensive analyses of the effects of a PPFA ban on access to care for women covered by Medicaid. These estimates focused on where Medicaid patients would receive the services they would have otherwise received at PPAHCs. CBO expected that some Medicaid beneficiaries who had received services at a PPAHC would obtain services at another facility that accepts Medicaid reimbursement, which would mean little change in Medicaid spending. However, this assumption may be more uncertain if a large percentage of these patients switched to FQHCs because the FQHC payment rate is higher than the rate paid for services provided at PPAHCs, so it is possible that redirecting care to FQHCs could increase Medicaid costs. However, CBO's estimates did not address how likely this scenario was.

CBO also noted that while it expected that some patients would find alternate providers, not all would be able to do so, because alternate providers are not available in some areas. Specifically, CBO estimated that between 5% and 25% of the 2.6 million people served by PPFA would be unable to access care in the first year of a funding prohibition (i.e., 2016). CBO noted that alternate providers might begin to serve these areas eventually, but that this process could take time. As such, CBO estimates that by 2020, 2% of those who lost access would not have found an alternate provider.

To derive its cost estimates, CBO used a midrange estimate. It assumed that 15% of Medicaid beneficiaries served by PPFA would lose access to care in the first year. Given that some people would forgo services, CBO estimates that there would be some immediate declines in the use of Medicaid services, which would result in cost savings. CBO estimated that $235 million would be the midrange estimate of the 10-year cost savings associated with a 1-year ban on federal funds to PPFA. CBO noted that their estimates were uncertain, in part, because some of the services forgone at PPFA may be for contraception. CBO also estimated that the reduced use of contraceptive services would lead to additional births and could lead to increased federal spending over a longer term both because of the costs associated with births and because some of the children may qualify for Medicaid or other federal programs. Specifically, CBO predicts that the additional costs would be $20 million in the first year and $60 million over a 10-year period. The $235 million that CBO estimates a one-year ban would save is estimated net of these increased costs. As discussed above, the AHCA estimate was more explicit in that it stated that it would expect that the number of births in the Medicaid program would increase by several thousand. This most recent estimate also noted that Medicaid pays for 45% of all births and that it is likely that some of the children themselves would qualify for other federal programs.95

In reviewing other legislation introduced in the 114th Congress (H.R. 3134), CBO also estimated the costs associated with a permanent ban to PPFA and found that because of declines in access to care, primarily family planning care, a permanent ban would increase spending by $130 million over a 10-year period (2016-2025). Most of the increased Medicaid spending would be for increased births that would be paid by the Medicaid program, as CBO estimates that, in the first few years of a permanent ban, the number of births would increase by several thousand per year.

CBO's estimates also discussed the provisions that would redirect funds to FQHCs and noted that it did not expect that the additional funds appropriated to FQHCs would be sufficient to mitigate the predicted loss of access that would occur under the ban. CBO estimates that this would be the case because HHS would not be able to award funds to FQHCs in time to prevent immediate disruptions in access.96 In addition, CBO states that the legislation that would reallocate funds to FQHCs may not be specific enough to avert access disruptions. CBO states that these funds could be used generally by FQHCs for primary care or preventive services. As such, these funds may not be used to increase family planning services or other women's health services that may have otherwise been provided to Medicaid beneficiaries at PPAHCs.

State Restrictions on PPFA Funding

Federal restrictions on funds to PPFA are currently pending, but some states also have made it difficult for PPFA to participate in state programs or have excluded PPFA and PPAHCs from receiving funds from state programs. In 2013, Texas excluded PPFA (and other abortion providers) from its family planning program (the Texas Women's Health Program). This exclusion followed a 2011 funding reduction of two-thirds of program funding available and a change in the program's funding preference toward comprehensive health care facilities over those that provide more limited family planning related services. Several studies evaluated the effects of the program changes on women's health and access to care.

A 2016 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine examined Medicaid claims data for women of reproductive age and found that the number of LARC claims decreased by 35.5% and Medicaid spending for childbirth services increased by 27.1%. In addition, they found differences in the rate of women receiving follow-up shots for injectable contraception in counties that did and did not have a PPAHC. In particular, women who lived in a county that had a PPAHC affiliate that was no longer eligible for Medicaid reimbursement were less likely to receive an on-time follow-up contraceptive injection (a difference of 22.9% in the county comparisons).97

Another study by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)98 found that the U.S. maternal mortality rate overall increased from 2000 to 2014 and that the maternal mortality rate in the United States was higher than previously reported because of underreporting of maternal deaths. Their study examined the rates of California and Texas separately and found that while California's rate decreased over the time period, Texas had a sudden increase in its rate between 2011 and 2012, when its rate doubled. The authors note that this increase occurred several years after Texas had revised its methods of reporting maternal death and that Texas had not made any reporting changes during the period when the increase occurred. The authors suggest that the sudden increase could be due to the changes in the Texas Women's Health Program, but note that available data are not sufficient to definitely determine causality. Despite this, the authors state that the changes that occurred were not due to reporting changes and that there were no other conditions such as a natural disaster or adverse economic conditions that could otherwise explain the large increase. Researchers from the Texas Department of State Health Services and the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force dispute the NCHS author's attribution of the mortality increase to the Texas Women's Health Program policy changes. They agree that there was an increase in 2011 to 2012, but dispute that it doubled. Instead, they argue that the data used to categorize whether a woman was pregnant or had recently given birth at the time of her death are unreliable and that the magnitude of the increase observed varies depending on which method is used to make the determination of pregnancy or recent pregnancy.99

As another example, Wisconsin, in 2011, excluded PPAHCs from receiving Title X funding and state Maternal Child Health Block Grant funds.100 The state legislation that enacted this exclusion also prohibited state laboratories from reading cancer screening tests that were performed at excluded providers (i.e., at PPAHCs). As a result of the funding loss and the lab restrictions, researchers found that several clinics in Wisconsin and in neighboring Minnesota closed. Researchers have examined the impact of these program changes on the receipt of preventive screenings and found that as the distance to a provider increased, low-income women were less likely to have preventive screenings such as mammograms. Declines in receipt of mammograms were more common among women who had lower levels of education. The authors of this study examined both Texas and Wisconsin and found somewhat stronger results for Texas because there were fewer nearby non-PPAHC providers to care for the patients who could no longer use PPAHCs.101

A number of states have also sought to terminate PPFA and PPAHC participation in their state's Medicaid programs. As of the date of this publication, these terminations have not occurred, and therefore no data exist to evaluate the potential effects. States have also considered restricting PPFA from participating in family planning programs administered using state funds received from the Federal Title X program. A regulation was released in 2016 and became effective on January 18, 2017, that says states may not exclude providers from Title X for reasons other than their ability to provide Title X services.102 In 2017, the House and Senate passed H.J.Res. 43, a bill to nullify this regulation. The President signed this measure into law on April 13, 2017.103 This report may be updated if changes occur.

Appendix. Acronyms Used in this Report

|

ACA |

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, as amended |

|

AHCA |

American Health Care Act of 2017 |

|

CBO |

Congressional Budget Office |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

CHIP |

Children's Health Insurance Program |

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

FDA |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

|

FMAP |

federal medical assistance percentage |

|

FPL |

federal poverty guideline |

|

FQHC |

Federally Qualified Health Center |

|

GAO |

Government Accountability Office |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HIV |

human immunodeficiency virus |

|

HPSA |

health professional shortage area |

|

HRSA |

Health Resources and Services Administration |

|

IUD |

intrauterine device |

|

JCT |

Joint Committee on Taxation |

|

LARC |

long-acting reversible contraceptives |

|

MQSA |

Mammography Quality Standards Act |

|

MUA |

medically underserved area |

|

NACHC |

National Association of Community Health Centers |

|

NAF |

National Abortion Federation |

|

NCHS |

National Center for Health Statistics |

|

OPA |

Office of Population Affairs |

|

PPAHC |

Planned Parenthood Affiliated Health Center |

|

PPFA |

Planned Parenthood Federation of America |

|

STD |

sexually transmitted disease |

|

STI |

sexually transmitted infections |

|

UDS |

Uniform Data System |

|

USPSTF |

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force |