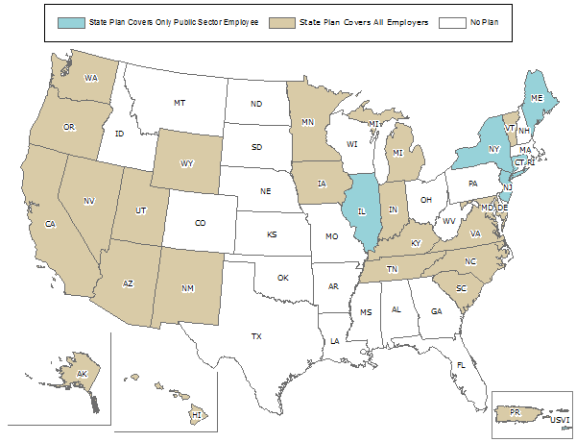

State Occupational Safety and Health Plans

Under the provisions of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act),1 the federal government, through the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), has the primary responsibility for establishing and enforcing workplace safety standards.2 However, Section 18 of the OSH Act permits any state or territory to preempt federal jurisdiction over occupational safety and health by establishing an approved state occupational safety and health plan.3

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) map created with data from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) website at https://www.osha.gov/dcsp/osp/index.html. |

Figure 1 and Table 1 highlight that 21 states and Puerto Rico currently have state plans that cover private- and public-sector employers and 5 states and the U.S. Virgin Islands have plans that cover only state and local government employers, who are not covered by OSHA. In addition, Maine is currently in the process of establishing a state plan for state and local government employers, and New Jersey, which has a state plan for public-sector workers only, is in the process of extending its state plan to cover all employers. OSHA estimates that 40% of all American workers are covered by a state occupational safety and health plan.4

|

Covers Private- and Public-Sector Workers |

Covers Only Public-Sector Workers |

|

|

Alaska |

New Mexico |

Connecticut |

|

Arizona |

North Carolina |

Illinois |

|

California |

Oregon |

Maine |

|

Hawaii |

Puerto Rico |

New Jersey |

|

Indiana |

South Carolina |

New York |

|

Iowa |

Tennessee |

U.S. Virgin Islands |

|

Kentucky |

Utah |

|

|

Maryland |

Vermont |

|

|

Michigan |

Virginia |

|

|

Minnesota |

Washington |

|

|

Nevada |

Wyoming |

|

Source: Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) website at https://www.osha.gov/dcsp/osp/index.html.

State Plan Requirements

In general, for a state occupational safety and health plan to be approved, it must be "at least as effective" as the standards established and enforced by OSHA at providing for workplace safety. Specifically, Section 18(c) of the OSH Act requires OSHA to approve a state plan if the plan

- designates a state agency or agencies that are responsible for administering the plan throughout the state;

- provides for the development and enforcement of safety and health standards relating to one or more safety or health issues, which standards (and the enforcement of such standards) are or will be at least as effective in providing safe and healthful employment and places of employment as the standards promulgated under Section 6 [of the OSH Act] relating to the same issues, and which standards, when applicable to products that are distributed or used in interstate commerce, are required by compelling local conditions and do not unduly burden interstate commerce;

- provides for a right of entry and inspection of all workplaces subject to the act that is at least as effective as that provided in Section 8 [of the OSH Act], and includes a prohibition on advance notice of inspections;

- contains satisfactory assurances that such agency or agencies have or will have the legal authority and qualified personnel necessary for the enforcement of such standards;

- gives satisfactory assurances that such state will devote adequate funds to the administration and enforcement of such standards;

- contains satisfactory assurances that such state will, to the extent permitted by its law, establish and maintain an effective and comprehensive occupational safety and health program applicable to all employees of public agencies of the state and its political subdivisions, which program is as effective as the standards contained in an approved plan;

- requires employers in the state to make reports to the Secretary [of Labor] in the same manner and to the same extent as if the plan were not in effect; and

- provides that the state agency will make such reports to the Secretary in such form and containing such information, as the Secretary shall from time to time require.5

State Plan Approval Process

Any state or territory may submit a state plan to OSHA for approval. The first step in the approval process is for a state to submit a Developmental Plan to OSHA. Required elements of a developmental plan include

- state legislation,

- regulations and procedures for establishing occupational safety and health standards,

- enforcement systems,

- appeals processes, and

- sufficient staffing to implement the state plan.

In addition, a developmental plan must demonstrate that within three years the state will have the necessary infrastructure to be effective.

- The state plan is eligible for Certification once a state has submitted a developmental plan. OSHA provides certification once a state demonstrates that it has the necessary infrastructure in place as outlined in its developmental plan. The OSHA Certification process does not render any judgment on the effectiveness of the state plan and does not result in the preemption of federal jurisdiction.

- When OSHA determines that a state is capable of meeting the statutory state plan requirements, including the requirement that the plan is "at least as effective" as the federal system, OSHA and the state may enter into an Operational Status Agreement that outlines which employers will be under state jurisdiction and which will remain under federal jurisdiction.

- A state plan may receive Final Approval at least one year after certification. Final approval is the formal decision of OSHA that the plan is meeting its statutory requirements and that the plan is as least as effective as the federal system. After final approval is granted, all employers, except those under federal jurisdiction as a matter of law, are under state, rather than federal, jurisdiction.6

- A state dissatisfied with OSHA's decision not to grant approval to its state plan may request a hearing before an administrative law judge of the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission (OSHRC).

- A plan may operate indefinitely under an operational status agreement without ever receiving final approval from OSHA, which may be modified upon agreement between the state and OSHA. For example, the largest state plan, administered by the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA), received certification in 1977 and has been operating under an operational status agreement since that time without having received final approval from OSHA. Currently, seven states and territories are operating state plans under operational status agreements rather than final approvals.7

Monitoring of State Plans

OSHA monitors approved state plans to ensure that they remain at least as effective as the federal system in providing for occupational safety and health through the Federal Annual Monitoring Evaluation (FAME) process. Monitoring state plans includes (1) reviewing state laws and standards to ensure effectiveness; (2) reviewing the operation and administration of state plans; and (3) assessing state progress toward meeting performance goals. Each year, OSHA issues a FAME report for each state plan.8 If OSHA finds deficiencies in a state's plan, it can require changes to the plan and ultimately reconsider its decision to approve the state plan such that OSHA reasserts partial or full jurisdiction over occupational safety and health in the state.

State Plan Funding

Section 23(g) of the OSH Act authorizes the Department of Labor (DOL) to make matching grants to states to cover up to 50% of the cost of the administration of approved state occupational safety and health plans.9 A state may overmatch the federal grant amount with state funds. The total amount available for state plan grants comes from the discretionary appropriation to the DOL for OSHA. The FY2016 appropriation for OSHA state plan grants was $100.850 million and DOL requested $104.377 million for state plan grants for FY2017.10

Examples of State Occupational Safety and Health Plans

Detailed information on each of the approved state occupational safety and health plans is available on the OSHA website.11 This section will focus on two state plans that are involved with current controversial occupational safety and health issues. The California state plan exceeds OSHA's standards and includes specific requirements that employers must fulfill when their employees are working outdoors during periods of high temperatures. The Arizona state plan includes a residential construction fall protection standard that has recently been deemed insufficient by OSHA and may result in OSHA reconsidering its approval of the state plan.

California

The California state occupational safety and health plan is administered by Cal/OSHA. The California plan is unique in that it includes a specific occupational safety and health standard that applies in cases of employees working outdoors during periods of high temperatures with the goal of reducing heat-related illnesses. Unlike the California state plan, OSHA does not have a specific standard addressing the hazards of working outdoors in high temperatures. Thus, the California state plan exemplifies going beyond the statutory requirement of providing a state plan that is at least as effective as the federal system and implementing standards to address hazards not specifically covered by OSHA.

OSHA and Heat Illness

There is no federal occupational safety and health standard that specifically addresses the hazards of working outdoors in high temperatures. Rather, OSHA relies on the following existing section of the OSH Act and federal standards to attempt to reduce heat-related illnesses and injuries:

- Section 5(a)(1) of the OSH Act, commonly referred to as the General Duty Clause, requires that each employer "shall furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees";12

- the personal protective equipment (PPE) standards require each employer to assess potential hazards to employees and provide employees with appropriate PPE to protect against these hazards;13

- the sanitation standards require employers to provide employees with access to potable water;14 and

- the safety training and education standard for construction requires construction employers to "instruct each employee in the recognition and avoidance of unsafe conditions" in the workplace.15

|

|

Source: OSHA website at https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/heatillness/edresources.html. |

In addition, OSHA has developed a smartphone application that allows employers and workers to determine the current heat index and risk level for heat illness and provides recommended protection measures based on the current risk level. OSHA has also launched a heat illness prevention safety campaign that includes the use of materials, such as the poster shown in Figure 2, developed by Cal/OSHA as part of California's state occupational safety and health plan.

Cal/OSHA's Heat Illness Prevention Standard

In 2005, Cal/OSHA established a heat illness prevention standard as part of California's state occupational safety and health plan and updated this standard in 2015.16 The Cal/OSHA standard requires all employers with outdoor places of employment to

- provide training in the risks and prevention of heat illness to all employees and supervisors before engaging in work that may expose employees to high temperatures; and

- in temperatures of at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit, provide access to shade or other cooling systems, such as misters, and permit employees to take breaks of at least five minutes whenever they feel it necessary to protect against heat illness.

The Cal/OSHA standard has additional rules regarding periods of high heat (at least 95 degrees Fahrenheit) that apply to the following industries:

- agriculture,

- construction,

- landscaping,

- oil and gas extraction, and

- transportation of agricultural production, construction materials, or other heavy items unless the employee is in an air-conditioned vehicle and is not involved in the loading or unloading of the vehicle.

At temperatures of at least 95 degrees Fahrenheit, covered employers must maintain communication with all employees; observe employees for signs of heat illness, especially new employees not yet acclimated to high heat conditions; and remind employees to drink water. In addition, agricultural employers must provide workers with at least a 10-minute rest period every two hours when temperatures reach 95 degrees.

Arizona

The Arizona state occupational safety and health plan received final approval from OSHA in 1985 and is administered by the Arizona Occupational Safety and Health Division (ADOSH) of the Industrial Commission of Arizona (ICA). In February 2015, OSHA announced that it was rejecting the residential construction fall protection standard in the Arizona state plan, which prompted Arizona, in accordance with state law, to adopt the OSHA standard.

OSHA's Residential Construction Fall Protection Standard

OSHA's residential construction fall protection standard requires that each employee who works in residential construction activities at a height of at least 6 feet above the ground or the next lower level be protected from falls by a guardrail, safety net, or personal fall arrest system (known as conventional fall protection).17 This standard was initially issued on August 1994, but concerns over its feasibility led OSHA to issue interim compliance procedures in December 1995 that permitted employers to use nonconventional fall protection systems, such as slide guards, rather than the safety systems required by the standard.18 On December 16, 2010, OSHA cancelled its interim guidance and announced that the residential construction fall protection standard would go into effect in June 2011.19 This effective date was later postponed by OSHA to September 22, 2011.20

Arizona's Residential Construction Fall Protection Legislation

On June 16, 2011, ADOSH adopted the federal residential fall protection standard. However, the next day the ICA stayed enforcement of the standard. The stay was lifted on November 20, 2011, effective January 1, 2012. On March 27, 2012, SB 1441 was enacted into law in Arizona.21 The legislation requires conventional fall protection only when an employee is working at a height of at least 15 feet or when the slope of the roof is steeper than 7:12 (measured as the ratio of rise to run). The legislation also created an exception in cases in which conventional fall protection is not feasible or creates a greater hazard.22 ADOSH adopted the provisions of SB 1441 as a standard as part of its state occupational safety and health plan.23

OSHA's Response to Arizona's Legislation

On March 19, 2014, OSHA sent the Arizona ICA a show-cause letter asking the ICA to demonstrate why OSHA should not begin proceedings to reject the state's residential construction fall protection statute and reconsider final approval of the Arizona state plan on the grounds that the standard is not at least as effective as the federal standard. Arizona's response to this letter focused on the changes to the initial legislation made by the enactment of SB 1307 as discussed below.

Arizona's Amended Standard

On April 22, 2014, Arizona enacted SB 1307, which made minor changes to the residential construction fall protection standard while maintaining the minimum height of 15 feet for the use of conventional fall protection. In addition, Section 7 of SB 1307 includes a provision that repeals the provisions in the Arizona Revised Statutes created by SB 1441 that contain the residential construction fall protection standard if OSHA publishes a notice rejecting the state statute.

OSHA's Rejection of the Arizona Standard

On February 6, 2015, OSHA published a notice in the Federal Register that it was formally rejecting the Arizona residential construction fall protection standard and excluding this standard from Arizona's state plan.24 Because of the provision in SB 1307 repealing the Arizona residential construction fall protection legislation upon notice of its rejection by OSHA, OSHA stated that it expected Arizona to now incorporate the federal standard into its state plan and would defer any decision on reconsidering final approval of the Arizona state plan pending the state's action.

The same day that OSHA rejected the Arizona fall protection standard, the Arizona ICA announced that due to OSHA's decision and in accordance with SB 1307, the Arizona fall protection standard was automatically repealed and that, effective February 7, 2015, all Arizona employers would be required to comply with the OSHA fall protection standard.25