Introduction

Surface transportation "devolution" refers to shifting most current federal responsibility for building and maintaining highways and public transportation facilities from the federal government to the states. Devolution would involve reducing the federal taxes on motor fuels that currently provide most of the federal funding distributed to states and local transit authorities. States would then have the option of making up for the reduction in federal funding by raising state motor fuel taxes or providing funds from other sources, as they see fit. The federal government would maintain a much smaller program to meet limited purposes such as building and maintaining roads on federal lands and Indian reservations and providing funds for repairs after disasters. This program could be paid for either by appropriations from the general fund or by retaining federal motor fuel taxes at lower rates.

Devolution would reduce the scope of many of the requirements that are attached to the use of federal funds. Federal regulation and oversight of project construction, prevailing wage requirements, federal construction standards, and federal environmental regulation would no longer apply to surface transportation projects funded exclusively with state and local resources. Advocates of devolution contend that elimination of these requirements would reduce the cost of constructing transportation projects and speed their completion.

Arguments for devolution of surface transportation programs have emerged periodically since the administration of President Ronald Reagan.1 In 1987, devolution was recommended in a detailed report by the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations.2 However, Congress has given the states greater authority over the expenditure of federal highway funds in recent years, addressing one of the factors leading to calls for devolution. In addition, financial and policy concerns have deterred serious consideration of devolution proposals.

How the Surface Transportation Program Operates

Highway construction has involved a federal-state partnership since passage of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 (39 Stat. 355).3 The highway program has had three basic attributes: a required state match of federal funds, a designated network of roads eligible for federal funding, and formula apportionment of funds to the states. The Federal Aid Highway and Highway Revenue Acts of 1956 (70 Stat. 374, 387), which authorized the construction of the Interstate System, increased federal involvement in highway planning and construction. The act raised federal highway taxes and channeled the receipts into a new Highway Trust Fund (HTF), removing highway funding from the normal appropriations process.

Congress subsequently created many separate programs to require that states spend shares of their HTF apportionments for specific purposes. This proliferation of programs was reversed in 2012 by the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21; P.L. 112-141), which consolidated 92% of the act's funding into five large formula-driven programs. State departments of transportation (state DOTs) largely determine which projects are funded, let the contracts, and oversee project development and construction.4

The federal government has provided funding for public transportation through the HTF since 1982. Unlike the federal-state relationship in the federal-aid highway program, the federal mass transit program generally involves a relationship between the federal government and a transit authority.5

All spending on the federal-aid highway program and about 80% of spending on public transportation are funded from the HTF, which has two accounts: the highway account and the mass transit account. The primary revenue sources for the HTF are an 18.3-cent-per-gallon federal tax on gasoline and a 24.3-cent-per-gallon federal tax on diesel fuel. Although the HTF has other sources of revenue, such as truck registration fees and a truck tire tax, and is also credited with interest paid on the fund balances held by the U.S. Treasury, fuel taxes have in recent years provided roughly 85% of the amounts paid into the fund by highway users. The mass transit account receives 2.86 cents per gallon of fuel taxes, with the remainder of the tax revenue credited to the highway account.

Every year since 2008, there has been a gap between the dedicated tax revenues flowing into the HTF and the cost of surface transportation spending Congress has authorized. Congress has filled these shortfalls with a series of transfers, largely from the Treasury's general fund. These transfers have shifted a total of $143.6 billion to the HTF. The last $70 billion of these transfers were authorized in the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act; P.L. 114-94), which was signed by President Barack Obama on December 4, 2015.6 The FAST Act funds federal surface transportation programs from FY2016 through FY2020. When the act expires, the de facto policy of relying on general fund transfers to sustain the HTF will be 12 years old.

Opposition to raising the federal fuels tax rates has left the rates unchanged since 1993. The taxes have lost roughly 40% of their purchasing power since then.

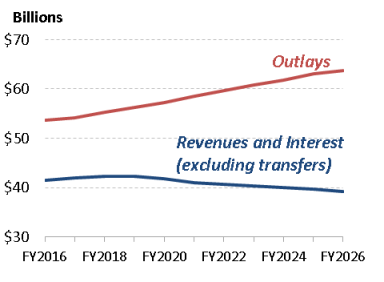

Figure 1 shows the trust fund's financial outlook. The gap between tax revenues coming into the HTF and outlays from the fund is projected to widen. The general fund transfers authorized under the FAST Act will fill this gap through FY2020. Thereafter, Congress will need either to reduce federal spending for surface transportation or find additional resources to fund highway and public transportation programs.

The difficult situation of the Highway Trust Fund poses an obstacle to devolution. The federal taxes that flow into the HTF are insufficient to fund the surface transportation program that Congress has authorized. If most of the program were to be devolved to the states and the related federal taxes were to be replaced by state taxes, total revenue would still be insufficient to support the current magnitude of highway and public transportation spending.

|

|

Source: Congressional Budget Office. |

The Case for Devolution

Advocates of devolution have generally made the following case since the 1980s:

- The federal government is overinvolved in the planning and construction of highways and public transportation. The states have a much better understanding of their own highway needs, and federal involvement should be limited to highways that have a clear national purpose.

- Public transportation is inherently local and should be a local or state responsibility with no federal involvement.

- Some states receive more federal surface transportation funding, relative to the highway taxes paid by their motorists, than other states. Devolution would eliminate this discrepancy by giving each state control of its motorists' tax payments.

- The maintenance and reconstruction of the Interstate System highways, federal lands highways, and perhaps, existing federal programs supporting transportation research and highway safety are valid federal responsibilities and should remain with the federal government.

- Eliminating federal funding for most surface transportation projects would reduce regulatory burdens on states and localities, leading to efficiencies and cost reductions.

The Case Against Devolution

Critics of devolution have typically made the following claims:

- National interests are too great to be addressed without a strong federal role. All states benefit from a broad, properly functioning national highway network. This network could be in jeopardy with less federal support, as state capital project funding may prove less reliable than federal funding.7

- Devolution would make it more difficult for states or groups of states to concentrate funds for large projects of regional or national significance because local interests will more likely trump national needs.

- Some parts of the nation are less well off than others and would have trouble paying for the roads and bridges they need to support economic development and national connectivity.

- Regulations tied to federal funding of highways and public transportation help ensure implementation of national goals such as highway and transit safety, clean air and water, and civil rights, and may save money by leveling the playing field among contractors and encouraging national competition for bids.

- Devolution would require major funding transfers to pay for the transition.

- Changes during the last two surface transportation reauthorization acts have given states greater control over highway expenditures, and Congress has adhered to an earmark ban since 2011. These changes have addressed some of the complaints that originally led to calls for devolution.

|

Selected Legislation Addressing Devolution* Transportation Empowerment Act of 1996 (Representative Kasich and Senator Mack, sponsors, H.R. 3840/S. 1971, 104th Congress). The act adhered to recommendations of the Advisory Council on Intergovernmental Relations, limiting the federal role to Interstate maintenance, federal lands highways, national security highways, emergency relief, and a special Infrastructure Special Assistance Fund. The responsibilities for other programs were to be taken over by the states. A four-year phase-out of 12 cents of the 18.4-cent-per-gallon federal gasoline tax was to mirror the declining federal role. The bills were never reported out of committee. However, the Kasich/Mack devolution proposal was voted on in Congress as part of the amendment process of surface transportation reauthorization legislation.8 Transportation Empowerment Act of 2002 (Senator Inhofe, sponsor, S. 2861, 107th Congress). This was a modified version of the 1996 act that included funding for transportation research and a share table for the apportionment of Interstate Maintenance funds to the states. Similar versions were introduced each Congress through the 112th Congress.9 Highway Fairness and Reform Act of 2009 (Senator Hutchinson, sponsor, S. 903, 111th Congress). This bill would have allowed a state to opt out of the Federal-Aid Highway Program and instead receive a federal transfer equal to the state's payments to the highway account of the Highway Trust Fund, less the state's prorated share of funding for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the Federal Motor Carrier Administration, as determined by DOT. The mass transit account was not made available for opt out. State Transportation Flexibility Act of 2011 (Representative Lankford and Senator Coburn, sponsors, H.R. 1585/S. 1446, 112th Congress). This bill would have allowed states to opt out of both the federal highway and public transportation programs. Amounts equal to a state's payments to the HTF would have been transferred back to the state.10 Transportation Empowerment Act of 2013 (Representative Graves, of Georgia, and Senator Lee, sponsors, H.R. 3486/S. 1702, 113th Congress). This bill would have modified the Kasich/Mack/Inhofe proposals to adjust for the programmatic changes made in MAP-21. The act would have funded the federal lands programs, highway research and development, the Emergency Relief Program, and administrative expenses. The National Highway System would have been designated the Federal-aid System. No funds were to be provided for other discretionary programs. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, and the Federal Transit Administration would not have been funded. The bill would have eliminated all the nonfuel highway taxes at the end of FY2016. It would have continued existing motor fuels tax rates through FY2019 and then reduced the rates to 3.7 cents per gallon for gasoline and 5.0 cents per gallon for diesel. All proceeds would have been deposited in the highway account of the HTF, and mass transit account balances would have been transferred to the highway account. The bill would have gradually reduced apportioned funding of the formula highway programs via a declining "core financing rate." As the revenues apportioned to the programs declined each year under the declining core financing rate, the remaining "excess" tax receipts would have increased from year to year and been rebated to the states at the beginning of each year (FY2016 through FY2018). The act did not make clear how the receipts were to be distributed before they were collected. Transportation Empowerment Act of 2015 (Representative DeSantis and Senator Lee, H.R. 2716/S. 1541, 114th Congress). This bill would have devolved the programmatic structure much in the way that the 2013 bill would have. The bill language was modified in response to an FHWA analysis showing that the bill would have required about $50 billion in general fund transfers to pay for outstanding federal obligations to the states.11 In response, H.R. 2716/S. 1541 would have delayed the core financing rate reductions until the third year of the bill and would not have eliminated the nonfuel highway taxes. Even so, the bill would likely have required general fund transfers to pay outstanding obligations for highway projects completed by the states without ending nearly all new federal-aid highway spending. The act would have retained federal motor fuels taxes, but at rates too low to cover reconstruction of the Interstate System. * To date, no surface transportation devolution legislation has passed either chamber of Congress. |

What Might a Devolved Transportation System Look Like?

Surface transportation devolution proposals generally have certain characteristics in common: they would reduce or eliminate existing federal programs, reduce the federal taxes on motor fuels, and leave the states to provide replacement funding for highway purposes if they wish to do so. Most devolution proposals would retain existing federal programs to maintain roads on federal lands, fund transportation research, and provide relief to rebuilt roads and bridges damaged in natural disasters. Nearly all transportation devolution proposals would eliminate the federal public transportation program.

At the same time, devolution proposals have taken differing approaches to a number of important matters. Some would retain a federal role in maintaining the Interstate Highway System and important bridges, while others would not. Some have retained the major highway formula grant programs, albeit on a far smaller scale, while others have proposed to eliminate those programs. The treatment of two federal safety agencies, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, has also been a point of contention; no proposal to date would have devolved those agencies' responsibilities to the states, but elimination of the Highway Trust Fund would leave Congress the choice of letting the programs expire or funding them from the Treasury's general fund.

Upfront Costs

Devolving the current federal highway and transit programs to the states would involve substantial upfront costs. Under the current programs, surface transportation funding is usually authorized in multiyear authorization bills. Each year of funding is available for obligation for the current year and the three subsequent years. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) uses its contract authority to legally obligate the federal government to pay its share of a project's cost prior to construction. The state lets the contracts, oversees construction, pays the contractor, and submits vouchers to FHWA for reimbursement. As projects frequently take several years to complete, in any given year FHWA is making payments to the states based on commitments made several years earlier. These payments are made mostly from the current year's HTF receipts.12 Public transportation funding works in a similar manner, with the sponsoring transit agency signing contracts for approved expenditures and the Federal Transit Administration providing reimbursement as portions of the work are completed.

At any time there is a build-up of outstanding obligations for which the federal government is legally responsible. At the end of FY2016, outstanding obligations totaled $65.5 billion for the highway account and $18.6 billion for the mass transit account.13 These figures represent the amount of previously approved activities for which the federal government must pay when vouchers are submitted for repayment by the states or transit authorities.

Thus, devolution may require a period of higher overall motor fuel taxation. Even if the federal government hands responsibility for funding new highway and public transportation projects to the states, it would need to retain motor fuels taxes or some other revenue source to assure repayment of outstanding obligations. This taxation would have to continue alongside whatever new taxes states impose until outstanding HTF obligations are completely paid for, a period that likely would last three or four years.

Federal Revenue Losses

Although devolution would reduce federal spending on transportation, the net savings to the federal government would be less than the amount of the spending reduction because many states extensively use tax-exempt bonds as part of their financing mechanisms. If states were to make up for the elimination of federal surface transportation funding by issuing more tax-exempt bonds, the U.S. Treasury would lose revenue.14

Replacing the Relinquished Federal Taxes

Virtually all surface transportation devolution proposals would reduce or phase out most of the federal motor fuels taxes (and in most cases also eliminate the other taxes on highway users) over several years. The presumption is that state governments would use this period to adjust their own taxes accordingly. The simplest way to do this would be for the states to increase their own taxes on gasoline and highway diesel fuel by the same amount as the reduction in the federal taxes.

However, there are reasons to believe that replacing federal motor fuels taxes with state fuels taxes on a cent-for-cent basis would not provide sufficient revenue to fund the current level of spending on highways and public transportation. One reason is that a large share of federal spending on surface transportation now comes from the general fund, not from taxes dedicated to the Highway Trust Fund. On average, the states would need to raise their taxes on motor fuels by 5 or 6 cents per gallon more than the amount of motor fuels taxes relinquished by the federal government to make up for the loss of the general fund transfers that Congress has been providing. Adding this to the relinquished taxes would mean state legislatures would face, on average, passing increases of about 20 to 21 cents per gallon in their state taxes on gasoline and diesel fuel.15

In addition, states that currently receive relatively large amounts of federal highway funding, relative to the amount their motorists pay in federal fuel taxes, would have to increase their state fuel taxes even more to maintain current spending. Among these are states with small populations, including several geographically large, sparsely populated western states. Alaska, for example, would likely have to increase its fuels taxes by over $1 per gallon to make up for the lost federal funds under devolution. Several other states, including Vermont, Rhode Island, and Montana, would likely have to enact replacement fuel taxes of roughly 30 to 40 cents per gallon more than the reduction in federal taxes to maintain current spending.16 Assuming a 15-cent-per-gallon reduction in federal taxes, these states would be facing total increases in state fuel taxes in the range of 45 to 55 cents per gallon to maintain the current level of spending.

On the other hand a few states, notably Texas, might be able to reduce the total fuels tax paid by their motorists. These states currently receive less in federal highway funding than the national average, relative to their motorists' payments of federal fuel taxes, and would therefore benefit more than other states from devolution.

Devolution would not require that replacement fuel taxes be enacted. State legislatures could decide to dedicate other taxes to surface transportation or rely on their general revenues to fund highways and public transportation. States could also pass the cost downward by requiring local governments to pick up some of the costs of the devolved programs. States might consider expanded use of tolling in lieu of higher taxes. Some might choose not to make up for the reduction in federal grants and instead spend less on transportation.

Institutional Changes

Devolution would lead to changes at the U.S. Department of Transportation, principally at the Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Transit Administration.17 About two-thirds of FHWA's roughly 2,750 employees work at its field offices. There is at least one division office in each state.18 The level of staffing at these offices might be greatly reduced depending on the degree to which project oversight responsibilities are reduced or eliminated. However, FHWA would continue to have responsibility for some programs and projects, as well as certain inspection and safety activities. The agency would need to determine whether district offices would be necessary to conduct these activities. The need for the Federal Transit Administration's roughly 550 full-time-equivalent positions would depend on the extent to which Congress retains a federal role in public transportation.19

Congress and the Administration would also face a determination of what, if any, role the federal government would have in transportation planning. Current federal law sets planning requirements that must be met at the state and regional levels to receive federal funds for transportation and certain other activities. For example, each state must maintain a state transportation improvement plan, and federal funds may be used only for projects listed in the plan. Federal law requires the participation of many stakeholders in the planning process, public notification of certain actions, identification of state and regional goals, and development of short- and long-range state and metropolitan plans. Metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) exist primarily because of federal planning requirements. Devolution legislation might need to address whether federal mandates for state and metropolitan planning would continue and, if so, how they might be changed in view of the diminished federal role in surface transportation.

The states would have to determine how they would respond to devolution of responsibility for public transportation. In most states, the bulk of public transportation activities are conducted by local governments or by special-purpose authorities established by the legislature, rather than directly by the state government. States might need to create new mechanisms for overseeing and funding public transportation if the federal government were to retreat from those roles.

Federal incentives and sanctions are used to encourage state actions for highway safety purposes. For example, states receive additional federal highway funds or forfeit funds to which they otherwise would be entitled if they fail to enforce a minimum drinking age of 21 years; if they do not set a blood alcohol level of 0.08 beyond which a driver is considered impaired; if they lack laws prohibiting open containers of alcoholic beverages in vehicles; or if they do not require use of safety belts. It is unclear how these incentives would be provided if states were no longer to receive federal highway funding. Devolution could reduce the federal safety role and leave states with greater discretion over safety policies.20 In the past, this has led to relaxation of safety regulations. For example, in the early 1970s Congress enacted funding penalties for states that did not require motorcyclists to wear helmets. By 1975, 49 states had such laws. In 1976 Congress repealed the law; many of the states then repealed their helmet laws.

Cutting Back the Federal Requirements

Congress has attached numerous requirements to the use of federal surface transportation funds. Advocates of devolution have argued that federal requirements, especially when taken as a whole, negatively impact the cost efficiency of the federal-aid programs.21 An important consideration in devolving highway programs to the states is the extent to which these requirements would continue to apply.

Eliminating federal funding for highways and transit projects would not eliminate all requirements on state departments of transportation in regard to development and construction of those projects. A number of federal requirements would remain in effect.

Prevailing Wages

The Davis-Bacon Act (40 U.S.C. §§3141-3144, 3146-3147) requires that companies with public works construction contracts with the federal government or the District of Columbia valued in excess of $2,000 pay locally prevailing wages and fringe benefits. Prevailing wage rates are determined by the U.S. Secretary of Labor in consultation with the state highway departments and are often based on union wage scales. If devolution were to result in states building highway projects without federal funding, federal prevailing wage requirements would no longer apply. However, 30 states have prevailing wage requirements of their own. These states would continue to require highway contractors to pay prevailing wages, as determined under state law.22 Whether this would result in lower highway construction costs is unclear; recent studies find little connection between payment of prevailing wages and the cost of constructing highway projects because of the higher skill sets of workers attracted by higher pay and the increased use of machinery on high-wage job sites, which lead to more productive use of a smaller workforce.23

Brooks Act

The Brooks Act (40 U.S.C. §§1101-1104) requires the selection of contractors for engineering and design-related services to be based on the bidder's demonstrated competence and qualifications for the type of professional services required and the negotiation of fair and reasonable compensation. Highway projects would not be subject to these requirements if no federal funding were involved.

Construction Standards

Currently, projects on the National Highway System (which includes the Interstate System and most state highways and totals 223,000 miles of the 1,223,000 of highway mileage eligible for federal aid)24 must meet engineering standards developed under the auspices of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Other roads must meet state standards.25 All bridge projects using federal funds must meet the standards set forth in the AASHTO Bridge Design Specifications.26 States are free to use whatever design standards they wish for projects that do not involve federal funds, and this would presumably apply to a much larger number of projects if the highway program were to be devolved to the states.

The change would be most significant for small county or township bridges that currently are eligible for federal "off-system" bridge funding. Rebuilding projects using such funds must meet federal bridge standards. Some local officials see compliance with these standards as excessively costly for bridges that handle relatively low volumes of traffic.

Geographic Contractor Preferences

Under 23 U.S.C. §112, states must allow firms based anywhere in the United States to bid on highway construction contracts, and contracts must be awarded to the submitter of the lowest bid that meets the criteria in the request for bids. States are generally not allowed to limit bidding on federally funded projects to in-state companies or to companies based in a particular locality. Devolution would greatly increase the number of road and bridge projects funded entirely with state and local funds. Depending on state law, the responsible agencies could be free to reserve such contracts to in-state or local companies, which might result in fewer bids and higher average bid costs.

Nondiscrimination Requirements

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination in employment on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. The equal employment opportunity protections of Title VII apply to employers and contractors whether or not they receive federal funds. Title VII would be unaffected by devolution.27

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination in federally funded programs or activities on the basis of race, color, or national origin.28 Other statutes expand this protection to cover sex, age, and disability. FHWA division offices and FTA regional offices are responsible for ensuring that all funding recipients (state DOTs or transit agencies) have approved Title VI nondiscrimination plans and have effective programs to monitor their subrecipients' (e.g., local agencies') efforts to implement the nondiscrimination requirements. Title VI applies to all of a recipient's programs and activities, whether specific activities are federally funded or not.29 Because state DOTs are likely to continue to receive some federal funds after devolution, even if not for highway or transit construction, all of their contracts, including those for construction and professional services, would remain subject to Title VI. This is likely true as well for public transportation agencies, virtually all of which are creations of a city or state.30

The Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program is designed to give businesses owned by people from socially and economically disadvantaged groups equal opportunity to compete for and obtain federally funded contracts and business development opportunities.31 Each state DOT is required to establish an approved Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program that sets participation goals and monitors program activities. Although these requirements are based on federal project spending, the state programs would have to be maintained with respect to any projects for which states receive federal highway funds. However, the number of contracts affected by Disadvantaged Business Enterprise requirements might be much smaller after devolution.

U.S. DOT also has affirmative action requirements in the contractor compliance program.32 These requirements apply only to federally funded contracts. A nondiscrimination provision is included in every federal-aid contract. Under devolution, the hiring requirement under the contractor compliance program would apply to fewer contracts for highway work.33

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended, require civil rights protections for individuals with disabilities.34 Public agencies, including state DOTs and transit agencies, must ensure that their facilities are accessible to and usable by persons with disabilities, regardless of whether federal funding is involved. For example, ADA requires the availability of paratransit for individuals with disabilities who are unable to use fixed-route transportation systems.35 Devolution would not affect ADA's application.

Buy America Requirements

Buy America requirements apply to federally funded projects carried out by state and local governments, and thus have considerable impact on highway and public transit projects.36 Devolution proposals would greatly reduce the number of projects that would be subject to Buy America. However, MAP-21 specified that FHWA Buy America requirements apply to all contracts eligible for assistance within the scope of a project's National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) document, if at least one contract for the project is federally funded. Thus, even if states no longer receive formula grants for highway and bridge construction grants, Buy America would apply to a state-funded project if any other federal highway funds are to be used for any portion of the project.

Environmental Compliance37

DOT approval of a project to receive federal-aid highway funds is conditioned on the project sponsor meeting applicable federal environmental requirements. "Environmental" requirements include a broad array of requirements that could apply to a project based on its potential to have adverse impacts on community, natural, and cultural resources. Many of these requirements are specified in the National Environmental Policy Act and related regulations, executive orders, and policies.38 Under devolution, NEPA and a number of other environmental requirements may no longer apply.

With respect to federal-aid highway projects, many of those requirements apply only to "federal" actions (e.g., a project funded in part by or entirely using federal program funds). In some cases, environmental requirements apply explicitly to federal-aid highway projects. If devolution were to mean that a state's decision to approve a transportation project would no longer be considered a federal action and would no longer be subject to requirements applicable to federal-aid highways, the following federal requirements would no longer apply:39

- Requirements applicable only to "federal" actions. In addition to NEPA, these include, but are not limited to, requirements established under the National Historic Preservation Act, the Farmland Protection Policy Act of 1981, the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act, and executive orders intended to address adverse impacts on minority and low-income populations and to control impacts to wetlands and floodplains.

- Requirements applicable explicitly to federal-aid highway projects. These include standards, procedures, and conditions established under Title 23 of the U.S. Code and implemented largely in accordance with DOT regulations applicable to "Right-of-Way and Environment,"40 such as requirements concerning highway beautification, noise abatement, the mitigation of impacts on wetlands and natural habitats, and the identification of environmental impacts (under NEPA and additional requirements in Title 23). They also include procedures related to the "Section 4(f)"41 prohibition on the use of federal-aid highway funds for projects that adversely affect parks and recreation areas, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and historic sites.

It is difficult to determine the number of states that currently have or may choose to adopt similar requirements, absent a directive to do so in federal law.

Devolution would not eliminate all environmental requirements that affect highway projects. Some environmental standards established by the federal government could apply to any construction project, even if no federal funding is involved, based on its potential to affect certain resources protected under federal law. For example, devolution of the federal highway program likely would not eliminate requirements established under the Endangered Species Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, or the Rivers and Harbors Act.