Introduction

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), Title XIV of the Public Health Service Act, is the key federal law for protecting public water supplies from harmful contaminants. First enacted in 1974 and substantially amended in 1986, 1996, and 2016, the act is administered through programs that establish standards and treatment requirements for public water supplies, finance drinking water infrastructure projects, promote water system compliance, and control the underground injection of fluids to protect underground sources of drinking water. The 1974 law established the current federal-state arrangement in which states may be delegated primary implementation and enforcement authority for the drinking water program. The state-administered Public Water Supply Supervision (PWSS) Program remains the basic program for regulating the nation's public water systems, and 49 states have assumed this authority. In the SDWA amendments of 1996, Congress reauthorized appropriations for most SDWA programs through FY2003. Although the authorization of appropriations has expired for most provisions, Congress has continued to appropriate funds for the ongoing SDWA programs. Enacted in December 2016, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WINN) Act, P.L. 114-322, made numerous amendments to the SDWA, with significant focus on addressing lead in public water systems and increasing compliance assistance for small or disadvantaged communities. Table 1 identifies the original enactment and subsequent amendments.

|

Year |

Act |

Public Law Number |

|

1974 |

Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 |

|

|

1977 |

Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1977 |

|

|

1979 |

Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments |

|

|

1980 |

Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments |

|

|

1986 |

Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1986 |

|

|

1988 |

Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988 |

|

|

1996 |

Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1996 |

|

|

2002 |

Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 |

|

|

2011 |

Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act |

|

|

2013 |

Community Fire Safety Act of 2013 |

|

|

2015 |

Drinking Water Protection Act |

|

|

2015 |

Grassroots Rural and Small Community Water Systems Assistance Act |

|

|

2016 |

Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act |

This report summarizes the act's major provisions, programs, and requirements and provides statistics on the universe of regulated public water systems. Located at the end of the report, Table 2 cross-references sections of the act with the major U.S. Code sections of the codified statute, and Table 3 identifies authorizations of appropriations under the act.

Background

As indicated by Table 1, the SDWA has been amended several times since enactment of the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-523). Congress passed this law after nationwide studies of community water systems revealed widespread water quality problems and health risks resulting from poor operating procedures, inadequate facilities, and uneven management of public water supplies in communities of all sizes. The 1974 law gave the EPA substantial discretionary authority to regulate drinking water contaminants and gave states the lead role in implementation and enforcement.

The first major amendments (P.L. 99-339), enacted in 1986, were largely intended to increase the pace at which the EPA regulated contaminants and to increase the protection of ground water. From 1974 until 1986, the EPA had regulated just one additional contaminant beyond the 22 standards previously developed by the Public Health Service. The 1986 amendments required the EPA to (1) issue regulations for 83 specified contaminants by June 1989 and for 25 more contaminants every three years thereafter, (2) promulgate requirements for disinfection and filtration of public water supplies, (3) limit the use of lead pipes and lead solder in new drinking water systems, (4) establish an elective wellhead protection program around public wells, (5) establish a demonstration grant program for state and local authorities having designated sole-source aquifers to develop ground water protection programs, and (6) issue rules for monitoring underground injection wells that inject hazardous wastes below a drinking water source. The amendments also increased the EPA's enforcement authority.

Congress again amended SDWA with the Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-572). These provisions were intended to reduce exposure to lead in drinking water by requiring the recall of lead-lined water coolers and requiring the EPA to issue a guidance document and testing protocol for states to help schools and day care centers identify and correct lead contamination in school drinking water.

After the regulatory schedule mandated in the 1986 amendments proved to be unworkable for the EPA, states, and public water systems, the 104th Congress made sweeping changes to the act with the SDWA Amendments of 1996 (P.L. 104-182). As over-arching themes, the amendments targeted resources to address the greatest health risks, increased regulatory flexibility, and authorized funding for federal drinking water mandates. Congress revoked the requirement that the EPA regulate 25 new contaminants every three years and created a risk-based approach for selecting contaminants for regulation.

Among other changes, Congress added some flexibility to the standard-setting process, required the EPA to conduct health risk reduction and cost analyses for new rules, authorized a drinking water state revolving loan fund (DWSRF) program to help water systems finance infrastructure projects needed to comply with SDWA regulations and protect public health, added programs to improve small system compliance, expanded consumer information requirements, increased the act's focus on pollution prevention with a state source water assessment program, and streamlined the act's enforcement provisions. P.L. 104-182 authorized appropriations under the act through FY2003. Authorizations of appropriations under the SDWA are identified in Table 3.

In 2002, several drinking water security provisions were added to the SDWA through the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-188). Title IV of that act included requirements for community water systems serving more than 3,300 individuals to conduct vulnerability assessments and prepare emergency response plans. The law increased criminal and civil penalties for tampering with water supplies and required the EPA to conduct research on preventing and responding to terrorist or other attacks.

Signed into law on January 4, 2011, the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act, P.L. 111-380, tightened the SDWA definition of "lead free" and added specific exemptions from the ban on the use or sale of lead pipes and plumbing fittings and fixtures that are not lead free. (A subsequent amendment [P.L. 113-64] explicitly exempted fire hydrants from coverage under the act's lead plumbing restrictions.1) Enacted August 7, 2015, the Drinking Water Protection Act (P.L. 114-45) directed EPA to develop a strategic plan to assess and manage the risks associated with algal toxins in public drinking water supplies. Enacted December 11, 2015, the Grassroots Rural and Small Community Water Systems Assistance Act (P.L. 114-98) revised and reauthorized the small system technical assistance program and extended the authorization of appropriations for the program through FY2020.

In December 2016, Congress made numerous revisions to the SDWA through the WIIN Act (P.L. 114-322; Title II, the Water and Waste Act of 2016). Among other amendments, the WIIN Act authorized new grant programs to (1) help public water systems serving small or disadvantaged communities meet SDWA requirements; (2) support lead reduction projects, including lead service line replacement; and (3) establish a voluntary program for testing for lead in drinking water at schools and child care programs.2

Regulated Public Water Systems

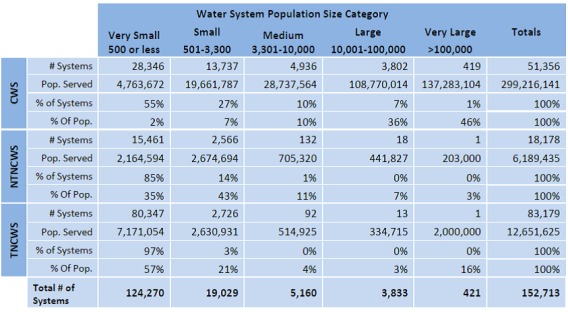

Federal drinking water regulations apply to the approximately 152,700 privately and publicly owned water systems that provide piped water for human consumption to at least 15 service connections or that regularly serve at least 25 people. These water systems vary greatly in size and type, ranging from large municipal systems to homeowner associations, schools, and campgrounds.

Some 51,350 of the regulated public water systems are community water systems (CWSs) that serve the same residences year-round. These water systems provide water to more than 299 million people. All federal regulations apply to these systems. Most community water systems (82%) are relatively small, serving 3,300 or fewer individuals. Despite this large percentage, these systems provide water to just 9% of the total population served by community water systems. Fully 92% of CWSs serve populations of 10,000 or fewer, and 55% serve populations of 500 or fewer. In contrast, 8% of CWSs serve populations of 10,000 or more but provide water to 82% of the population served (more than 246 million individuals). Among the community water systems, 71% rely on ground water, and 29% rely on surface water.

Another 18,178 public water systems are non-transient non-community water systems, such as schools or factories, which have their own water supplies and generally serve the same individuals for more than six months but not year-round. Most drinking water regulations apply to these systems. Of these water systems, 99% serve populations of 3,300 or fewer and provide water to 83% of the population served by these systems.

Nearly 83,200 other public water systems are transient non-community water systems, such as campgrounds and gas stations, which provide their own water to transitory customers. Only regulations for contaminants that pose immediate health risks apply to these systems.3

Approximately 95,800 of the nearly 101,400 non-community water systems (transient and non-transient systems combined) serve 500 or fewer people.

These statistics give some insight into the scope of financial, managerial, and technological challenges small public water systems may face in meeting federal drinking water regulations and maintaining water infrastructure to ensure the delivery of safe and sufficient water supplies. (Figure 1 provides statistics on community water systems, non-transient non-community water systems, and transient non-community water systems.)

|

Figure 1. Public Water System Statistics (water systems regulated under the SDWA) |

|

|

Source: EPA, Fiscal Year 2011 Drinking Water and Ground Water Statistics, EPA 816-R-13-003, March 2013, p. 8, http://water.epa.gov/scitech/datait/databases/drink/sdwisfed/upload/epa816r13003.pdf. Notes: The EPA has established three broad categories of public water systems. A community water system (CWS) serves the same population year-round. A non-transient non-community water system (NTNCWS) regularly supplies water to at least 25 of the same people at least six months per year but not year-round (e.g., schools, factories, office buildings, and hospitals that have their own wells). Transient non-community water systems (TNCWS) provide water in places where people do not remain for long periods of time, such as gas stations and campgrounds. |

National Drinking Water Regulations

A key component of SDWA is the requirement that EPA promulgate national primary drinking water regulations for contaminants that may pose health risks and are likely to be present in public water supplies. Section 1412 instructs EPA on how to select contaminants for regulation and specifies how and when the EPA must establish regulations once a contaminant has been selected. The regulations apply to privately and publicly owned "public water systems" that provide piped water for human consumption to at least 15 service connections or that regularly serve at least 25 people. The EPA has issued regulations for more than 90 contaminants, including regulations setting standards or treatment techniques for drinking water disinfectants and their byproducts, microorganisms (e.g., Cryptosporidium and Legionella), radionuclides, organic chemicals (e.g., benzene and many pesticides), and inorganic chemicals (e.g., arsenic and lead).4

Contaminant Selection and Regulatory Schedules

The SDWA, as amended in 1996, directs EPA to promulgate a drinking water regulation for a contaminant if the Administrator determines that the following three criteria are met:

- the contaminant may have adverse health effects;

- it is known, or there is a substantial likelihood, that the contaminant will occur in public water systems with a frequency and at levels of public health concern; and

- its regulation presents a meaningful opportunity for health risk reduction for persons served by public water systems.5

Every five years, EPA must publish a list of unregulated contaminants that are known or anticipated to occur in public water systems and that may require regulation (known as a contaminant candidate list [CCL]).6 The SDWA further directs EPA to administer a monitoring program for unregulated contaminants to facilitate the collection of occurrence data for contaminants that are not regulated but are suspected to be present in public water supplies. Every five years, EPA must publish a rule (Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule [UCMR]) listing no more than 30 unregulated contaminants to be monitored by public water systems.7 This list is based on the contaminant candidate lists as well as other data.8 Every five years, EPA is required to make a regulatory determination (whether or not to regulate) for at least five of the contaminants included on the CCL.

Standard Setting

For each contaminant that EPA determines requires regulation, EPA must set a nonenforceable maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG) at a level at which no known or anticipated adverse health effects occur and allows an adequate margin of safety.9 EPA must then set an enforceable standard, a maximum contaminant level (MCL), as close to the MCLG as is "feasible" using best technology, treatment techniques, or other means available (taking costs into consideration). Once the Administrator makes a determination to regulate a contaminant, EPA must propose a rule within 24 months and promulgate a "national primary drinking water regulation" within 18 months after the proposal.10

EPA may set a standard at other than the feasible level if the feasible level would lead to an increase in health risks by increasing the concentration of other contaminants or by interfering with the treatment processes used to comply with other SDWA regulations. In such cases, the standard or treatment techniques must minimize the overall health risk. Also, when proposing a regulation, EPA must publish a determination as to whether or not the benefits of the standard justify the costs. If EPA determines that the benefits do not justify the costs, the agency may, with certain exceptions, promulgate a standard that maximizes health risk reduction benefits at a cost that is justified by the benefits.11

Referencing legislative history, the agency generally sets standards based on technologies that are affordable for large communities; however, as amended by P.L. 104-182, the act requires EPA, when issuing a regulation for a contaminant, to list any technologies or other means that comply with the MCL and are affordable for small public water systems serving populations of 10,000 or fewer. If EPA does not identify "compliance" technologies that are affordable for small systems, then the agency must identify small system "variance" technologies or other means that may not achieve the MCL but are protective of public health.

New regulations generally become effective three years after promulgation. Up to two additional years may be allowed if EPA (or a state in the case of an individual system) determines the time is needed for capital improvements. EPA is required to review and strengthen, as appropriate, each drinking water regulation every six years.12 (Section 1448 outlines procedures for judicial review of EPA actions involving the establishment of SDWA regulations and other final EPA actions.)

Risk Assessment and Cost-Benefit Analysis

In the 1996 amendments, Congress added risk assessment and risk communication provisions to SDWA.13 When developing regulations, EPA is required to (1) use the best available, peer-reviewed science and supporting studies and data; and (2) make publicly available a risk assessment document that discusses estimated risks, uncertainties, and studies used in the assessment. When proposing drinking water regulations, EPA must publish a "health risk reduction and cost analysis." For each drinking water standard and each alternative standard being considered, EPA must publish and take comment on quantifiable and nonquantifiable health risk reduction benefits and costs and also conduct other specified analyses. EPA may promulgate an interim standard without first preparing a health risk reduction and cost analysis or making a determination as to whether the benefits of a regulation would justify the costs if the Administrator determines that a contaminant presents an urgent threat to public health.

Variances and Exemptions

In anticipation that some systems, particularly smaller ones, could have difficulty complying with every regulation, Congress included in the SDWA provisions for variances and exemptions. Section 1415 authorizes a state to grant a public water system a variance from a standard if raw water quality prevents meeting the standard despite application of best technology and the variance does not result in an unreasonable risk to health.

Subsection 1415(e) authorizes variances specifically for small systems, based on application of best affordable technology. When developing a regulation, if EPA cannot identify a technology that meets the standard and is affordable for small systems, EPA must identify variance technologies that are affordable but do not necessarily meet the standard. In cases where EPA has identified variance technologies, then states may grant small system variances to systems serving 3,300 or fewer persons if the system cannot afford to comply with a standard (through treatment, an alternative water source, or restructuring) and the variance ensures adequate protection of public health. A state may then grant a variance to a small system, allowing the system to use a variance technology to comply with a regulation. With EPA approval, states may also grant variances to systems serving between 3,301 and 10,000 persons. Variances are not available for microbial contaminants. The EPA has determined that affordable compliance technologies are available for all existing standards. Thus, small system variances are not available.

Section 1416 authorizes states to grant public water systems temporary exemptions from standards or treatment techniques if a system cannot comply for other compelling reasons (including costs). An exemption is intended to give a water system more time to comply with a regulation and can be issued only if it will not result in an unreasonable health risk. A qualified system may receive an exemption for up to three years beyond the compliance deadline. Systems serving 3,300 or fewer persons may receive a maximum of three additional two-year extensions for total exemption duration of nine years.

Oversight of Public Water Systems: State Primacy

Section 1413 authorizes states and Indian tribes to assume primary oversight and enforcement responsibility (primacy) for public water systems when EPA determines that statutory criteria are met.14 Currently, 55 of 57 states and territories have primacy authority for the public water system supervision (PWSS) program.15 Too assume primacy, a state16 must adopt regulations at least as stringent as national requirements, develop adequate procedures for enforcement (including conducting monitoring and inspections), adopt authority for administrative penalties, conduct inventories of water systems, maintain records and compliance data, and make reports as EPA may require. Further, a state must develop a plan for providing safe drinking water under emergency circumstances.

To help states cover the costs of administering the PWSS program, Congress authorized to be appropriated $100 million annually (FY1997-FY2003) for EPA to make grants to the states (Section 1443). EPA is required to allot the sums among the states "on the basis of population, geographical area, number of public water systems, and other relevant factors." Additionally, states may use a portion their annual DWSRF grant under Section 1452 to cover the costs of administering the PWSS program.17

Enforcement, Consumer Information, and Citizen Suits

The SDWA requires public water systems to monitor their water supplies to ensure compliance with drinking water standards and to report monitoring results to the states. States review monitoring data submitted by public water systems, and also conduct their own monitoring, to determine system compliance with drinking water regulations. EPA monitors public water system compliance primarily by reviewing the violation data submitted by the states.

Section 1414 requires that, whenever EPA finds that a public water system in a state with primary enforcement authority does not comply with regulations, the agency must notify the state and the system and provide assistance to bring the system into compliance. If the state fails to commence enforcement action within 30 days after the notification, EPA is authorized to issue an administrative order or commence a civil action. In a nonprimacy state, EPA must notify an elected local official (if any has jurisdiction over the water system) before commencing an enforcement action against the system.

The 1996 amendments strengthened enforcement authorities, streamlined the process for issuing federal administrative orders, increased administrative penalty amounts, made more sections of the act clearly subject to EPA enforcement, and required states (as a condition of primacy) to have administrative penalty authority. The amendments also provided that no enforcement action may be taken against a public water system that has a plan to consolidate with another system.18

Consumer Information and Reports

Enforcement provisions also require public water systems to notify customers of violations of drinking water standards or other requirements, such as monitoring and reporting requirements. Under Section 1414, systems must notify customers within 24 hours of any violations that have the potential to cause serious health effects. The WIIN Act, Section 2106, added public notification requirements for water system exceedances of the lead action level under EPA's Lead and Copper Rule (or subsequent promulgated lead level). Notification requirements previously applied to violations of standards and other applicable requirements but not to exceedances. Water systems must now notify the public, the state, and EPA of system lead action level exceedances. Further, for an exceedance that has potential to cause serious adverse health effects from short-term exposure, a water system must notify the public, the state, and EPA within 24 hours. If the state or water system does not provide the required notice, EPA must notify the public within 24 hours after the Administrator is notified.

The WIIN Act further amended the SDWA to address lead action level exceedances at households. EPA is required to develop a strategic plan for providing targeted outreach, education, and technical assistance to populations affected by lead in the water system. Also, if EPA develops or receives data indicating that a household's water exceeds the lead action level, EPA is required to forward the data and testing information to the water system and the state. The water system is required to provide the data and other specified information to the affected households. Within 24 hours of learning that a water system has failed to do so, EPA is required to consult with the governor and, using the strategic plan, provide the information to the households no later than 24 hours after the end of the consultation period.

Section 1414 also requires community water systems to mail to all customers an annual "consumer confidence report" on contaminants detected in their drinking water. States are required to prepare annual reports on the compliance of public water systems and to make summaries available to EPA and the public; EPA must prepare annual national compliance reports.19

Citizen Suits

Section 1449 provides for citizens' civil actions. Citizen suits may be brought against any person or agency allegedly in violation of provisions of the act or against the EPA Administrator for alleged failure to perform any action or duty that is not discretionary.

Emergency Powers

Under Section 1431, the Administrator has emergency powers to issue orders and commence civil action if (1) a contaminant likely to enter a public drinking water supply system poses a substantial threat to public health, and (2) state or local officials have not taken adequate action. The Bioterrorism Act amended this section to specify that the EPA's emergency powers include the authority to act when there is a threatened or potential terrorist attack or other intentional act to disrupt the provision of safe drinking water or to impact the safety of a community's drinking water supply.

Lead in Drinking Water

Several SDWA provisions specifically address lead in drinking water. In addition to the public notification provisions discussed above, the SDWA strictly limits the amount of lead in pipes and plumbing materials used to provide drinking water, imposes public notice and education requirements on states and EPA, and includes two grant programs (authorized in the WIIN Act). These provisions are outlined below.

Lead-Free Plumbing

Section 1417 broadly prohibits the use of any pipe, pipe or plumbing fitting or fixture, solder, or flux in the installation or repair of public water systems or plumbing in residential or other facilities providing drinking water that is not "lead free" (as defined in the act). This section also makes it unlawful to sell solder or flux that is not lead-free (unless it is properly labeled) or pipes, plumbing fittings, or fixtures that are not lead-free, with the exception of pipes used in manufacturing or industrial processing or other specific exceptions.20 Added in 1986, Section 1417(d) defined "lead free" to mean not more than 0.2% lead for solders and fluxes and not more than 8% lead for pipes and pipe fittings. The law gives states, not EPA, the responsibility to enforce the prohibitions.

In 1996, Congress added Section 1417(e), directing the EPA to issue regulations setting health-based performance standards limiting the amount of lead that may leach from new plumbing fittings and fixtures unless a voluntary industry standard was established within one year of enactment. An industry standard was established.

Enacted January 4, 2011, the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act (P.L. 111-380) amended Section 1417 to revise the SDWA definition of "lead free" and to add new exemptions from prohibitions on the use or sale of lead pipes, plumbing, and fittings and fixtures. The act reduced the allowable level of lead in products in contact with drinking water from 8.0% to 0.25% (weighted average)21 and exempted from the general prohibitions (A) "pipes, pipe fittings, plumbing fittings, or fixtures, including backflow preventers, that are used exclusively for nonpotable services such as ... industrial processing, irrigation, outdoor watering or any other uses where the water is not anticipated to be used for human consumption" (emphasis added); and (B) various specified products including tub fillers, shower valves, service saddles, or water distribution main gate valves at least 2 inches in diameter.

P.L. 111-380 removed the reference to Section 1417(e), which required that plumbing fittings and fixtures "intended by the manufacturer to dispense water for human ingestion" must comply with the industry standard. Rather, these products became subject to the definition of "lead free" in Section 1417(d). The provisions of P.L. 111-380 became effective on January 4, 2014, and any product that does not meet the 0.25% lead limit may no longer be sold or installed unless it is exempt from the general prohibitions.22 EPA proposed a rule to revise existing regulations to conform to the provisions of P.L. 111-380 on January 17, 2017.23

Added in 1986, Section 1417(a)(2) requires owners or operators of public water systems to provide notice to persons that may be affected by lead contamination of their drinking water if the source of contamination results from the construction materials of the water system or from corrosivity of the water. Subsection 1417(f), added in the WIIN Act, requires EPA to make educational information regarding lead in drinking water broadly available to the public.

Lead Reduction Project Grants

Also added by the WIIN Act, SDWA Section 1459B directs EPA to establish a grant program for projects and activities that reduce lead in drinking water, including replacement of lead service lines and corrosion control. Grants may be used to provide assistance to low-income homeowners to replace their portions of lead service lines. Eligible recipients include community water systems, tribal systems, schools, states, and municipalities. EPA must give funding priority to disadvantaged communities for projects that address lead action level exceedances, lead in water at schools and day care facilities, or other EPA priorities. EPA may waive the 20% nonfederal cost share requirement. This section authorizes to be appropriated $60 million per year for FY2017 through FY2021.

Lead in School Drinking Water

The WIIN Act, Section 2107, replaced SDWA Subsection 1464(d) to require EPA to establish a voluntary program for testing for lead in drinking water at schools and child care programs under the jurisdiction of local education agencies (LEAs).24 States or LEAs may apply to EPA for grants. To support this grant program, Congress authorized to be appropriated $20 million per year for FY2017 through FY2021.

Compliance Capacity and Assistance Programs

The 1996 amendments added two state-administered programs aimed at improving public water system compliance with drinking water regulations: the operator certification program and the capacity development program. Section 1419 required states to adopt programs for training and certifying operators of community and non-transient non-community systems (e.g., schools and workplaces that have their own wells). EPA is required to withhold 20% of a state's annual DWSRF grant unless the state adopts and implements an operator certification program. Relatedly, Section 1420 required states to establish capacity development programs, also based on EPA guidance. Congress specified that the programs must include (1) legal authority to ensure that new systems have the technical, financial, and managerial capacity to meet SDWA requirements; and (2) a strategy to assist existing systems that are experiencing difficulties to come into compliance. EPA is required to withhold a portion of SRF grants from states that do not have capacity development strategies. The agency has not had to withhold funds under either of these programs.

Small System Technical Assistance

In addition to the above compliance assistance programs, the act authorizes EPA and states to provide compliance assistance to public water systems and particularly to small systems (serving from 25 to 10,000 customers). Accounting for 92% of community water systems, these small systems frequently lack both economies of scale and the financial, managerial, and technical capacity to meet SDWA requirements.

Added in 1996, Subsection 1442(e) authorizes EPA to provide technical assistance to small public water systems. In this subsection, Congress authorized to be appropriated $15 million annually for FY1997 through FY2003 for EPA to provide technical assistance to small water systems through nonprofit organizations or other means. The Grassroots Rural and Small Community Water Systems Assistance Act (P.L. 114-98), enacted December 11, 2015, revised this program and extended the authorization of appropriations through FY2020. The technical assistance is intended to enable small systems to achieve and maintain compliance with drinking water regulations and may include circuit-rider and multi-state regional technical assistance programs, training, and assistance in implementing regulations, source water protection plans, monitoring plans, water security enhancements, etc. The WIIN Act amended Section 1442 to specify that technical assistance grants to tribes may be used for operator training and certification.

Relatedly, SDWA Section 1452, establishing the DWSRF program, authorized another source of funding for this technical assistance. SDWA Section 1452(q) authorized EPA to set aside up to 2% of the total funds appropriated for the DWSRF program for each of FY1997 through FY2003 to carry out the provisions of Section 1442(e) (relating to technical assistance for small systems, not to exceed the amount authorized in Section 1442(e)).25 In the WINN Act (P.L. 114-322, Section 2110), Congress extended this set-aside authority through FY2021.

Grant Assistance for Small and Disadvantaged Communities

Another provision added by the WIIN Act to the SDWA (Section 1459A) directs EPA to establish a grant program to assist disadvantaged communities and also small communities that are unable to finance projects needed to comply with SDWA. Eligible projects include investments needed for SDWA compliance, household water quality testing, and assistance that primarily benefits a community on a per-household basis. EPA must give funding priority to projects and activities that benefit underserved communities (i.e., communities that lack household water or wastewater services or that violate or exceed a SDWA requirement). EPA may make grants to public water systems, tribal water systems, or states on behalf of an underserved community. EPA may waive all or some of the 45% nonfederal share of project costs. Section 1459A(j) authorizes to be appropriated $60 million per year for FY2017 through FY2021.

Ground Water Protection Programs

Underground Injection Control Programs

Most public water systems rely on ground water as a source of drinking water, and Part C of the act focuses on ground water protection.26 Section 1421 authorized the establishment of state underground injection control (UIC) programs to protect underground sources of drinking water (USDWs). In 1977, EPA issued mandated regulations that contained minimum requirements for state UIC programs to prevent underground injection that endangers drinking water sources and required states to prohibit any underground injection not authorized by state permit. The law specified that the regulations could not interfere with the underground injection of brine from oil and gas production or recovery of oil unless USDWs would be affected.27

Section 1422 authorized affected states to submit plans to EPA for implementing UIC programs and, if approved, to assume primary enforcement responsibility. If a state's plan has not been approved, or the state has chosen not to assume program responsibility, then EPA must implement the program.28 For oil and gas injection operations only, states with UIC programs are delegated primary enforcement authority without meeting EPA regulations under Section 1421, provided that states demonstrate that they have an effective program that prevents underground injection that endangers drinking water sources.29 EPA has delegated primacy for all classes of wells to 35 states; it shares implementation responsibility with seven states and two Indian tribes and implements the UIC program for all well classes in nine states.

To implement this program, EPA has established six classes of UIC wells based on similarity in the fluids injected, construction, injection depth, design, and operating techniques and issued regulations that establish performance criteria for each class.30 Most recently, EPA issued regulations for Class VI wells establishing requirements for the underground injection of carbon dioxide (CO2). Class VI wells are intended to be used for the long-term geologic sequestration of CO2 as a tool for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants and other large stationary sources of carbon dioxide.

Other SDWA Groundwater Protection Programs

The act contains four other state programs aimed specifically at protecting groundwater.

- 1. Sole Source Aquifer Protection Program. Included in the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-523), Section 1424(e) authorizes EPA to make determinations—either on EPA's initiative or upon petition—that an aquifer is the sole or principal drinking water source for an area. In areas that overlie a designated sole-source aquifer, no federal funding may be committed for projects that EPA determines may contaminate such an aquifer.31 Any person may petition for sole source aquifer designation. Nationwide, EPA has designated 77 sole source aquifers.32

- 2. Sole Source Aquifer Demonstration Program. Section 1427, added in 1986, established procedures for demonstration programs to develop, implement, and assess critical aquifer protection areas already designated by the Administrator as sole source aquifers.

- 3. State Wellhead Protection Programs. Section 1428, also added in 1986, established an elective state program for protecting wellhead areas around public water system wells. If a state established a wellhead protection program by 1989 and EPA approved the state's program, then EPA may award grants covering between 50% and 90% of the costs of implementing the program.

- 4. State Groundwater Protection Grants. Section 1429, added in 1996, authorizes EPA to make 50% grants to states to develop programs to ensure coordinated and comprehensive protection of ground water within the states.

For these programs, appropriations were authorized through FY2003 as follows: $15 million per fiscal year for Section 1427, $30 million per fiscal year for Section 1428, and $15 million per fiscal year for Section 1429. Additionally, states may use a portion of their DWSRF capitalization grant under Section 1452(k) for certain groundwater protection activities.

Source Water Assessment and Protection Programs

The 1996 amendments expanded the act's pollution prevention focus to embrace protection of surface water as well as ground water. Section 1453 required EPA to publish guidance for states to implement source water assessment programs that delineate boundaries of the areas from which systems receive water and identify the origins of regulated contaminants (and also any contaminants selected by the state) in those areas to determine systems' susceptibility to contamination. States with approved assessment programs may adopt alternative monitoring requirements for water systems as provided for in Section 1418. Section 1452 (k)(1)(C) authorized states to use up to 10% of their DWSRF capitalization grant for FY1996 and FY1997 to delineate and assess source water protection areas.

Section 1454 authorized a source water petition program based on voluntary partnerships between state and local governments. States may establish a program under which a community water system or local government may submit a petition to the state requesting assistance in developing a voluntary source water quality protection partnership to (1) reduce the presence of contaminants in drinking water, (2) receive financial or technical assistance, and (3) develop a long-term source water protection strategy. This section authorized $5 million each year for grants to states to support petition programs. Also, states may use up to 10% of their DWSRF grant to support various source water protection activities, including the petition program.

State Revolving Funds

In 1996, Congress authorized the DWSRF program to help systems finance improvements needed to comply with SDWA regulations.33 EPA is authorized to make grants to states to capitalize DWSRFs, which states may then use to make loans to public water systems. States must match 20% of the federal grant. Grants are allotted based on the results of needs surveys.34 Each state and the District of Columbia must receive at least 1% of the appropriated funds.

Drinking water SRFs may be used to provide loans for expenditures that EPA has determined will facilitate compliance or significantly further the act's health protection objectives. States must make available 15% of their annual allotment for loan assistance to systems that serve 10,000 or fewer persons to the extent that funds can be obligated for eligible projects. States may use up to 30% of their DWSRF grant to provide loan subsidies (including forgiveness of principal) to help economically disadvantaged communities. Also, Section 1452(g) authorizes states to use a portion of funds for technical assistance, source water protection and capacity development programs, and operator certification.

The law authorized appropriations of $599 million for FY1994 and $1 billion per year for FY1995 through FY2003 for DWSRF capitalization grants. EPA was directed to reserve, from annual DWSRF appropriations, 0.33% for financial assistance to several trusts and territories, $10 million for health effects research on drinking water contaminants, $2 million for the costs of monitoring for unregulated contaminants, and up to 2% for technical assistance. The EPA may use 1.5% of funds each year for making grants to Indian tribes and Alaska Native villages.35

The WIIN Act (P.L. 114-322; Section 2113) made several amendments to the DWSRF provisions. Among other changes, the amendments increased the portion of the annual DWSRF capitalization grant that states may use to cover program administration costs. Further, the WIIN Act amended Section 1452(a) to require, with some exceptions, that funds made available from a state DWSRF during FY2017 may not be used for water system projects unless all iron and steel products to be used in the project are produced in the United States.

Drinking Water Security

The 107th Congress passed the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-188) to address a wide range of security issues. Title IV of the Bioterrorism Act amended the SDWA to address threats to drinking water security. Key provisions are summarized below.

Vulnerability Assessments

Under new SDWA Section 1433, each community water system serving more than 3,300 people was required to conduct an assessment of the system's vulnerability to terrorist attacks or other intentional acts intended to disrupt the provision of a safe and reliable drinking water supply. This provision established deadlines, based on system size, for community water systems to certify to the EPA that they had conducted a vulnerability assessment and to submit to the EPA a copy of the assessment. Section 1433 exempted the contents of the vulnerability assessments from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act (except for information contained in the certification identifying the system and the date of the certification), and it provides for civil and criminal penalties for inappropriate disclosure of information by government officials.

Section 1433 further required each of these community water systems to prepare an emergency response plan incorporating the results of the vulnerability assessment. EPA was directed to provide guidance to smaller systems on how to conduct vulnerability assessments, prepare emergency response plans, and address threats.

Section 1433(e) authorized the appropriation of $160 million for FY2002, and such sums as may be necessary for FY2003 through FY2005, to provide financial assistance to community water systems to conduct vulnerability assessments and prepare response plans and for expenses and contracts to address basic security enhancements and significant threats.

The Bioterrorism Act also added Sections 1434 and 1435 to SDWA, directing the EPA Administrator to review methods by which terrorists or others could contaminate or otherwise disrupt the provision of safe water supplies. These provisions require the EPA to review methods for preventing, detecting, and responding to such disruptions and methods for providing alternative drinking water supplies if a water system is destroyed or impaired. Section 1435(e) authorized $15 million for FY2002 and such sums as may be necessary for FY2003 through FY2005 to carry out Sections 1434 and 1435.

Tampering with Public Water Systems

Section 1432 provides for civil and criminal penalties against any person who tampers, attempts to tamper, or makes a threat to tamper with a public water system. Amendments made by the Bioterrorism Act increased criminal and civil penalties for tampering, attempting to tamper, or making threats to tamper with public water supplies. The maximum prison sentence for tampering increased from 5 to 20 years. The maximum prison sentence for attempting to tamper, or making threats to tamper, increased from 3 to 10 years. The maximum fine that may be imposed for tampering increased from $50,000 to $1 million. The maximum fine for attempting to tamper, or threatening to tamper, increased from $20,000 to $100,000. Relatedly, see "Emergency Powers" section.

Emergency Assistance

SDWA Subsection 1442(b) authorizes EPA to provide technical assistance and make grants to states and public water systems to assist in responding to and alleviating emergency situations. The Bioterrorism Act amended Subsection 1442(d) to authorize appropriations for such emergency assistance of not more than $35 million for FY2002 and such sums as may be necessary for each fiscal year thereafter. Congress has not appropriated funds for this purpose.

Additional SDWA Provisions

Research, Technical Assistance, and Training

Section 1442 authorizes EPA to conduct research, studies, and demonstrations related to the causes, treatment, control, and prevention of diseases resulting from contaminants in water. The agency is directed to provide technical assistance to the states and municipalities in administering their public water system regulatory responsibilities. This section authorized $15 million annually for technical assistance to small systems and Indian tribes and $25 million for health effects research. (Title II of P.L. 104-182, the 1996 amendments, authorized additional appropriations for drinking water research not to exceed $26.6 million annually for FY1997 through FY2003.)

Innovative Technology Grants

The WIIN Act amended Section 1442(a) to authorize EPA to conduct research on innovative water technologies and provide technical assistance to public water systems to facilitate use of such technologies. New Section 1442(f) authorizes to be appropriated $10 million for each of FY2017 through FY2021.

Demonstration Grants

The Administrator may make grants to develop and demonstrate new technologies for providing safe drinking water and investigate health implications involved in the reclamation/reuse of waste waters.36

Records, Inspections, and Monitoring

Section 1445 states that persons subject to requirements under the SDWA must establish and maintain records, conduct water monitoring, and provide any information that the Administrator may require by regulation to carry out the requirements of the act. Section 1445(b) authorizes the Administrator or a representative, after notifying the state in writing, to enter and inspect the property of water suppliers or other persons subject to the act's requirements to determine whether the person is in compliance with the act. Failure to comply with these provisions may result in civil penalties.

This section also directs EPA to promulgate regulations establishing the criteria for a monitoring program for unregulated contaminants. Beginning in 1999 and every five years thereafter, EPA must issue a list of not more than 30 unregulated contaminants to be monitored by public water systems. States are permitted to develop representative monitoring plan to assess the occurrence of unregulated contaminants in small systems, and the section authorized $10 million to be appropriated for each of FY1999 through FY2003 to provide grants to cover the costs of monitoring for small systems. All monitoring results are to be included in a national drinking water occurrence data base created under the 1996 amendments.

National Drinking Water Advisory Council

The act established a National Drinking Water Advisory Council, composed of 15 members (with at least two representing rural systems), to advise, consult, and make recommendations to the Administrator on activities and policies derived from the act.37

Federal Agencies

Any federal agency having jurisdiction over federally owned public water systems must comply with all federal, state and local drinking water requirements as well as any underground injection control programs. The act provides for waivers in the interest of national security.38

Drinking Water Assistance to Colonias39

Added in 1996, Section 1456 authorized EPA and other appropriate federal agencies to award grants to Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas to provide assistance (not more than 50% of project costs) to colonias where the residents are subject to a significant health risk attributable to the lack of access to an adequate and affordable drinking water system. Congress authorized appropriations of $25 million for each of fiscal years 1997 through 1999. (See also "Wastewater Assistance to Colonias.")

Estrogenic Substances

Section 1457 authorized EPA to use the estrogenic substances screening program created in the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-170) to provide for testing of substances that may be found in drinking water if the Administrator determines that a substantial population may be exposed to such substances.

Drinking Water Studies

Section 1458 directed EPA to conduct drinking water studies involving subpopulations at greater risk and biological mechanisms. EPA was also directed to conduct studies to support specific regulations, including those for disinfectants and disinfection byproducts and Cryptosporidium.

Algal Toxin Risk Assessment and Management

The Drinking Water Protection Act (P.L. 114-45), enacted August 7, 2015, added Section 1459. It directs EPA to develop—and submit to Congress in 90 days—a strategic plan to assess and manage the risks associated with algal toxins in public drinking water supplies. Section 1459 requires EPA to include in the plan steps and schedules for EPA to (1) assess health risks of algal toxins in drinking water, (2) publish a list of toxins likely to pose risks and summarize their health effects, (3) determine whether to issue health advisories for listed toxins, (4) publish guidance on feasible methods to identify and measure the algal toxins in water, (5) recommend feasible treatment and source water protection options, and (6) provide technical assistance to states and water systems. The new provisions also call for the Government Accountability Office to report to Congress on federal funds expended for each of FY2010 through FY2014 to examine toxin-producing cyanobacteria and algae or address public health concerns related to harmful algal blooms.40

Selected P.L. 104-182 Provisions Not Amending SDWA

The 104th Congress included a variety of drinking-water-related provisions in the 1996 SDWA amendments that did not amend the SDWA. Several of these provisions are described below.

Transfer of Funds

Section 302 authorized states to transfer as much as 33% of their annual drinking water state revolving fund grant to the Clean Water Act (CWA) SRF or an equivalent amount from the CWA SRF to the DWSRF through FY2001. In several subsequent conference reports for EPA appropriations, Congress authorized states to continue making transfers between the two funds, and in P.L. 109-54, Congress made this authority permanent.41

Grants to Alaska

Section 303 of the 1996 amendments authorized EPA to make grants to the state of Alaska to pay 50% of the costs of improving sanitation for rural and Alaska Native villages. Grants are for construction of public water and wastewater systems and for training and technical assistance programs. Appropriations were authorized at $15 million for each of FY1997 through FY2000. (In P.L. 106-457, Congress reauthorized appropriations for these rural sanitation grants at a level of $40 million for each of FY2001 through FY2005.)

Bottled Water

Section 305 revised Section 410 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to require the Secretary of Health and Human Services to issue bottled drinking water standards for contaminants regulated under SDWA within 180 days after EPA promulgates the new standards unless the Secretary determines that a standard is not necessary.

Wastewater Assistance to Colonias

Section 307 authorized EPA to make grants to colonias for wastewater treatment works. Appropriations were authorized at $25 million for each of FY1997 through FY1999. (See also "Drinking Water Assistance to Colonias.")

Additional Infrastructure Funding

Section 401 authorized additional assistance, up to $50 million for each of FY1997 through FY2003, for a grant program for infrastructure and watershed protection projects.

Table 2. U.S. Code Sections of the Safe Drinking Water Act

(Title XIV of the Public Health Service Act)

(42 U.S.C. 300f-300j-26)

|

42 U.S.C. |

Section Title |

SDWA |

|

Chapter 6A |

Public Health Service |

|

|

Subchapter XII |

Safety of Public Drinking Water Systems |

|

|

Part A |

Definitions |

|

|

300f |

Definitions |

§1401 |

|

Part B |

Public Water Systems |

|

|

300g |

Coverage |

§1411 |

|

300g-1 |

National drinking water regulations |

§1412 |

|

300g-2 |

State primary enforcement responsibility |

§1413 |

|

300g-3 |

Enforcement of drinking water regulations |

§1414 |

|

300g-4 |

Variances |

§1415 |

|

300g-5 |

Exemptions |

§1416 |

|

300g-6 |

Prohibitions on the use of lead pipes, solder, and flux |

§1417 |

|

300g-7 |

Monitoring of contaminants |

§1418 |

|

300g-8a |

Operator certification |

§1419 |

|

300g-9a |

Capacity development |

§1420 |

|

Part C |

Protection of Underground Sources of Drinking Water |

|

|

300h |

Regulations for state programs |

§1421 |

|

300h-1 |

State primary enforcement responsibility |

§1422 |

|

300h-2 |

Enforcement of program |

§1423 |

|

300h-3 |

Interim regulation of underground injections |

§1424 |

|

300h-4 |

Optional demonstration by states relating to oil and natural gas |

§1425 |

|

300h-5 |

Regulation of state programs |

§1426 |

|

300h-6a |

Sole source aquifer demonstration program |

§1427 |

|

300h-7a |

State programs to establish wellhead protection areas |

§1428 |

|

300h-8a |

State ground water protection grants |

§1429 |

|

Part D |

Emergency Powers |

|

|

300i |

Emergency powers |

§1431 |

|

300i-1 |

Tampering with public water systems |

§1432 |

|

300i-2a |

Terrorist and other intentional acts |

§1433 |

|

300i-3 |

Contaminant prevention, detection, and response |

§1434 |

|

300i-4a |

Supply disruption prevention, detection and response |

§1435 |

|

Part E |

General Provisions |

|

|

300j |

Assurance of availability of adequate supplies of chemicals necessary for treatment of water |

§1441 |

|

300j-1a |

Research, technical assistance, information, training of personnel |

§1442 |

|

300j-2a |

Grants for state programs |

§1443 |

|

300j-3a |

Special project grants and guaranteed loans |

§1444 |

|

300j-4a |

Records and inspections |

§1445 |

|

300j-5 |

National Drinking Water Advisory Council |

§1446 |

|

300j-6 |

Federal agencies |

§1447 |

|

300j-7 |

Judicial reviews |

§1448 |

|

300j-8 |

Citizen civil actions |

§1449 |

|

300j-9 |

General provisions |

§1450 |

|

300j-11 |

Indian tribes |

§1451 |

|

300j-12a |

State revolving loan funds |

§1452 |

|

300j-13 |

Source water quality assessment |

§1453 |

|

300j-14a |

Source water petition program |

§1454 |

|

300j-15 |

Water conservation plan |

§1455 |

|

300j-16a |

Assistance to colonias |

§1456 |

|

300j-17 |

Estrogenic substances screening program |

§1457 |

|

300j-18a |

Drinking water studies |

§1458 |

|

300j-19 |

Algal toxin risk assessment and management |

§1459 |

|

300j-19aa |

Assistance for small and disadvantaged communities |

§1459A |

|

300j-19ba |

Reducing lead in drinking water |

§1459B |

|

Part F |

Additional Requirements to Regulate the Safety of Drinking Water |

|

|

300j-21 |

Definitions |

§1461 |

|

300j-22 |

Recall of drinking water coolers with lead-lined tanks |

§1462 |

|

300j-23 |

Drinking water coolers containing lead |

§1463 |

|

300j-24a |

Lead contamination in school drinking water |

§1464 |

|

300j-26 |

Certification of testing laboratories |

|

Note: This table shows only the major code sections. For more detail and to determine when a section was added, consult the official printed version of the U.S. Code.

a. These sections include authorizations of appropriations.

b. This provision was added by the Lead Contamination Control Act (P.L. 100-572, §4), which did not amend SDWA.

|

42 U.S.C. |

Purpose |

Last Authorized Amount |

Last Fiscal Year of Authorization |

SDWA, as amended |

|

300g-8(d) |

Small public water system operator training and certification |

$30,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1419(d) |

|

300g-9(f) |

Small public water systems technology assistance centers |

$5,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1420(f) |

|

300g-9(g) |

Environmental finance centers |

$1,500,000 |

FY2003 |

§1420(g) |

|

300h-6(m) |

Sole source aquifer demonstration program |

$15,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1427(m) |

|

300h-7(k) |

State programs to establish wellhead protection areas |

$30,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1428(k) |

|

300h-8(f) |

State groundwater protection grants |

$15,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1429(f) |

|

300i-2(e) |

Community water system security enhancement grants |

Such sums as may be necessary |

FY2005 |

§1433(e) |

|

300i-4(e) |

Review of methods by which terrorists or others may disrupt or contaminate water supplies and methods to prevent, detect, and respond to such actions |

Such sums as may be necessary |

FY2005 |

§1435(e) |

|

300j-1(d) |

Emergency grants and technical assistance |

Such sums as may be necessary |

Indefinite |

§1442(d) |

|

300j-1(e) |

Technical assistance for small system compliance |

$15,000,000 |

FY2020 |

§1442(e) |

|

300j-1(e) |

Technical assistance for innovative water technologies |

$10,000,000 |

FY2021 |

§1442(f) |

|

300j-2(a) |

State Public Water System Supervision program grants |

$100,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1443(a) |

|

300j-2(b) |

State Underground Injection Control program grants |

$15,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1443(b) |

|

300j-2(d) |

New York City Watershed Protection grants |

$15,000,000 |

FY2010 |

§1443(d) |

|

300j-3(c) |

Special demonstration projects grants |

$10,000,000 |

FY1977 |

§1444(c) |

|

300j-4(a) |

Monitoring program for unregulated contaminants |

$10,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1445(a) |

|

300j-19a |

Assistance for small and disadvantaged communities |

$60,000,000 |

FY2021 |

§1449A(j) |

|

300j-19b |

Reducing lead in drinking water |

$60,000,000 |

FY2021 |

§1449B(d) |

|

300j-12(m) |

State Revolving Loan Fund program grants |

$1,000,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1452(m) |

|

300j-14(e) |

State Source Water Petition program grants |

$5,000,000 |

FY2003 |

§1454(e) |

|

300j-16(e) |

Grants to colonias for safe drinking water |

$25,000,000 |

FY1999 |

§1456(e) |

|

300j-18(c) |

Studies on harmful contaminants in drinking water |

$12,500,000 |

FY2003 |

§1458(c) |

|

300j-18(d) |

Waterborne disease occurrence study |

$3,000,000 |

FY2001 |

§1458(d) |

|

300j-24 |

Voluntary school and child care program lead testing grant program |

$20,000,000 |

FY2021 |

§1464(d) |

Source: Prepared by the Congressional Research Service based on a search of authorizations of appropriations in the Safe Drinking Water Act, as amended, and codified in the U.S. Code.

Notes: The 1996 amendments (P.L. 104-182) included several related authorizations of appropriations in provisions that did not amend the SDWA: (1) P.L. 104-182, Section 201, Drinking Water Research Authorization, authorized to be appropriated through FY2003 additional sums as may be necessary for drinking water research, not to exceed an annual total of $26,593,000; (2) Section 303, Grants to Alaska to Improve Sanitation in Rural and Native Villages, authorized appropriations of $15,000,000 annually from FY1997 to FY2000; and (3) Title IV, Additional Assistance for Water Infrastructure and Watersheds (§401(d)), provided an unconditional authorization of appropriations of $25,000,000 annually from FY1997 to FY2003 and a conditional authorization of appropriations of $25,000,000 annually from FY1997 to FY2003.