Introduction

In February 2016, the United States signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with 11 countries: Canada, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei.1 The TPP, now subject to approval and implementation by Congress, is termed by its participants as a comprehensive and high-standard agreement, designed to eliminate and reduce trade barriers and establish and enhance trade rules and disciplines among the parties. If implemented, it would be the largest plurilateral FTA by value of trade, encompassing roughly 40% of world GDP, and could serve further to integrate the United States in the dynamic Asia-Pacific region. As a "living agreement," it has the potential to negotiate new rules and expand its membership. It could also mark a shift to the negotiation of "mega-regional" trade liberalization agreements in lieu of bilateral FTAs and broader multilateral trade liberalization in the World Trade Organization (WTO).2

In considering TPP and other trade agreements, discussions often focus on potential economic effects, and especially on potential gains or losses in employment.3 In addition, some observers have tied U.S. trade deficits to existing U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) by arguing that the agreements have worsened the trade deficit and, thereby, have negatively affected U.S. employment and wages. According to many economists, trade in general provides economy-wide net positive benefits for consumers as a whole and for producers, especially for firms in export-oriented industries. They also note, conversely, that economic adjustment costs stemming from lower trade barriers may be highly concentrated, affecting some workers, firms, and communities disproportionately. The relationship between trade and jobs, however, is complicated and subject to a number of different and, at times, opposing forces. In addition, impediments in local labor markets may raise adjustments costs for some workers, firms, and communities in ways that may not be fully reflected in traditional trade models.

This report examines recent studies on the potential economic impact of the TPP. It also provides a limited discussion of the role of trade agreements in the economy and examines selected studies on the impact of TPP. For a broader treatment of some of these issues see CRS Report R44546, The Economic Effects of Trade: Overview and Policy Challenges, by James K. Jackson.

In general, economists and others use various economic models and approaches to estimate the magnitude of changes in U.S. economic activity and employment that could arise from a trade agreement. Both proponents and opponents of trade agreements often cite the results of these studies to support their respective positions. These models, however, differ in the estimates they produce, reflecting different assumptions and differences in the structure of the models themselves. While all the various models and approaches have strengths and weaknesses, although not always in equal proportions, they vary in the degree to which they reflect economic reality, and they are highly sensitive to the assumptions they use.4

Estimating the Economic Effects of Trade Agreements

The TPP, considered by participants to be a high-standard and comprehensive agreement, is designed to eliminate and reduce trade barriers and establish and enhance trade rules and disciplines of the trading system among the parties to the agreement. The agreement covers goods, services, investment, and a number of other issues including trade facilitation, digital trade, intellectual property rights, and standards, or technical barriers to trade. Due to the limitations of data and other theoretical and practical issues involved with services, investment, and non-tariff barriers, most estimates of the economic and employment effects of trade and trade agreements focus narrowly on the goods sector, where data on trade and tariff rates are available, to estimate how demand for these goods may change as a result of changes in tariffs. Accordingly, such estimates do not represent the total impact of the agreement on the economy.

Costs and Benefits of Trade

Most economists argue that liberalized trade creates both economic costs and benefits, as indicated in Table 1, but that the long-run net effect on the economy as a whole is positive. They contend that the economy as a whole operates more efficiently as a result of competition through international trade and that consumers throughout the economy benefit by having available to them a wider variety of goods and services at varying levels of quality and price than would be possible in an economy closed to international trade. They also contend that trade may have a long-term positive dynamic effect on an economy that enhances both production and employment. In addition, trade agreements of the type currently being negotiated by the United States comprise a broad range of issues that could have far-ranging economic effects on trade and commercial relations over the long run between the negotiating parties, particularly for developing and emerging economies.

|

Economy-wide benefits |

Concentrated adjustment costs |

|

Efficiency gains as a result of greater competition. |

Potential job losses in some sectors. |

|

Consumption gains for consumers throughout the economy by having access to a wider variety of goods and services at varying levels of quality and price. |

Potential lower wages for some workers. |

|

Gains in real income for consumers and producers by having access to lower priced goods and services. |

Concentrated adjustments costs. Some workers and firms may experience a disproportionate share of the adjustment costs. Recent research is shedding new light on the extent to which these adjustment costs are concentrated in some communities. |

|

Long-term positive dynamic effects arising through increased productivity and technological development. |

The benefits and costs to the economy do not accrue at the same speed: the costs to the economy in the form of job losses are experienced in the initial stages, while the benefits to the economy accrue over time. |

|

Potential economic gains achieved through trade agreements that affect trade and commercial relations over the long run. |

Source: CRS.

Most economists acknowledge that international trade and trade agreements can entail some negative effects through greater access to markets and increased competition, with the effects falling more heavily on some workers and firms. Generally, the costs and benefits associated with trade agreements do not accrue to the economy at the same speed; costs to the economy are felt in the initial stages of the agreement, while benefits to the economy accrue over time. The expected costs to the economy in the form of job losses and downward pressure on wages in some sectors and some segments of the labor force are experienced in the initial stages of the agreement, while the anticipated benefits to the economy in terms of enhanced consumer welfare and improvements in resource utilization accrue over time.

In addition, while research is ongoing, most economists have concluded that trade liberalization, or international trade more broadly, has not been a major factor affecting the distribution of income, whether in the United States, or in other economies, developed or developing.5 Some economists also estimate that international trade and trade liberalization have a different impact on workers in various occupations in the economy, termed by some as the occupational exposure to international trade. 6 This means that trade liberalization can have a disproportionate impact on workers and firms not only in different sectors of the economy, but even within the same industry. Such types of microeconomic analysis at the firm level generally are not within the scope of trade models.

Data Limitations

The lack of data in areas other than direct trade in goods and services means that data on traded goods and some services can drive policy debates. Economists and others face numerous challenges in their efforts to estimate precisely the economic and employment effects that are associated with agreements that reduce or eliminate barriers to trade and investment flows, including non-tariff barriers to trade in services and other sectors. Trade in services, in particular, is characterized by a broad array of formal and informal barriers that complicate efforts to translate the barriers into tariff-equivalent values. Also, little analysis has been done to date on the potential economic effects of removing or reducing technical barriers to trade.7 Reduced barriers to trade in services potentially could have a large and positive impact on the U.S. economy, since informal barriers to trade in services are numerous, the United States is highly competitive in a number of services sectors, and U.S. direct investment abroad often spurs exports.

The economic environment within which trade occurs is also being constantly shaped by domestic and international activities in ways that may be difficult to model and may not be fully reflected in the time series data that are the fundamental building blocks of trade models. For instance, the sharp decline in energy and raw material prices in 2015-2016 and the slowdown in global trade since 2011 are altering the global economy in ways that arguably exceed any potential trade agreement. It is unlikely that the complete effects of these changes have been fully reflected in global economic and trade data. Trade models also do not explicitly incorporate exchange rates, in part due to the difficulty involved in estimating future movements in exchange rates. Such models, therefore, rely on existing trade patterns that may limit their ability to estimate the impact of new trade patterns that could arise from a multi-country agreement.

Trade models also generally treat exports and imports as strictly domestic or foreign goods. However, the rapid growth of global value chains (GVCs) and intra-industry trade (importing and exporting goods in the same industry) have significantly increased the amount of trade in intermediate goods in ways that challenge traditional concepts of domestic versus foreign firms and blur the distinction between exports and imports. For instance, foreign value added accounts for about 28% of the content on average of global exports.8 As a result of the growth in GVCs, traditional methods of counting trade may obscure the actual sources of goods and services and the allocation of resources that are used in producing those goods and services. Trade in intermediate goods also means that imports may be essential for exports and that countries that impose trade measures restricting imports may negatively affect their own exports.9 This complex process of cross-border production and trade in intermediate goods also utilizes a broad range of services in ways that have expanded and redefined the role that services play in international trade. Increased trade in intermediate goods has also meant that the number of jobs in the economy tied directly and indirectly to international trade has increased in ways that are not captured fully by trade models.

Current Trade Arrangements

Efforts to estimate the economic impact of the proposed TPP are further complicated by the existence of overlapping trade agreements among the TPP countries: the United States already has FTAs with six TPP partners: Australia, Canada, Chile, Mexico, Peru, and Singapore.10 In addition, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei are members of the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) FTA. Such agreements have both trade creating and trade diverting dimensions that can interact in tandem or in opposite ways that may complicate the trade environment. While it may not be possible for any trade model to incorporate all the economic effects that potentially could arise from overlapping trade agreements, such agreements may be reshaping trade patterns that ostensibly could be enhanced further by the TPP.

In addition to the direct economic effects expected to result from cuts in tariffs, the TPP may offer additional long-term indirect benefits to bilateral and regional trade through changes in domestic non-tariff trade barriers that form the structure under which trade is conducted. In broad terms, the TPP incorporates rules and disciplines for open, transparent, non-discriminatory treatment for participants. These rules are expected to reduce market-distorting activities that not only reduce the overall level of trade, but create market inefficiencies. Some TPP participants have indicated that they intend to use the rules and disciplines in the TPP to support a reform agenda within their own economies. To the extent that countries undertake such reforms, the TPP potentially could provide long-term economic benefits to the countries themselves and to other TPP participants.

Anticipated Changes in Trade Patterns

Preferential multi-country trade agreements, such as the TPP, generally are expected to alter trade relations among the participants, stimulate economic growth, and improve overall economic welfare. By eliminating and reducing tariffs, trade agreements alter the external market conditions under which nations trade, while removing internal trade barriers alters the domestic structure under which trade is organized and conducted. Removing formal barriers to trade, primarily in the form of tariffs and quotas, directly lowers the prices of traded goods and thereby increases competition. In turn, lower prices are expected to alter trade patterns by increasing the amount of trade that occurs (trade creation) and by shifting trade away from countries that are not party to the agreement to those that are in the agreement (trade diversion). As a result, trade agreements may alter the composition of trade among a nation's various trading partners and alter the mix of goods and services that are traded. At times, countries are motivated to participate in trade agreements to forestall this type of trade diversion.

The magnitude of trade creation and trade diversion effects that may arise from the TPP are expected to depend on a number of factors, including the difference between pre-and post-agreement tariff rates, the speed with which tariff cuts are implemented, and other external economic factors that may affect global trade as a whole. In addition, the impact of tariff cuts under the TPP may be muted to some extent by the multiplicity of trade agreements that already exist among the participants and the already-low average tariff rates that are characteristic of trade among a number of the participants, although countries may have currently high tariffs on specific products.

For some countries, trade agreements may serve as a driving force for economic change in ways that cannot be quantified. Comprehensive free trade agreements as they currently are negotiated by the United States and others include a range of policy issues that have potentially significant cross-border implications, including trade in goods and services, investment, regulatory and other non-tariff barriers, government procurement, e-commerce, agricultural barriers, intellectual property rights, state-owned enterprises, worker rights, and the environment. As such, these trade agreements potentially can serve as catalysts for economic growth and development in ways that can affect a nation's economy beyond what would be predicted from traditional trade models. This can be particularly important for developing countries that are trying to raise their own standards and see trade agreements as important tools for integrating themselves into regional and global economies and for implementing domestic economic reforms. In addition, trade agreements may attempt to standardize such governance issues as dispute resolution procedures that work to enforce and ensure that trade commitments are implemented.11

Potential Changes in Employment

Estimating the impact of trade and trade agreements on employment and wages in the economy is particularly challenging, because trade is only one among a number of factors that affect the overall level of employment and wages in an economy in both the short run and long run. In addition, most trade models lack the detailed industry and employment data that are necessary to make forecasts beyond broad categories of employment to identify specific jobs that may be affected positively or negatively. It is also difficult in most circumstances to disentangle the myriad number and types of forces within the economy that can affect employment and wages at the micro, or firm, level. Additionally, a broad range of internal and external activities can affect national economies to a greater degree than most trade agreements in ways that cannot be factored in ahead of time. These activities can complicate efforts to derive cause and affect relationships.

Most economists argue that macroeconomic forces within the economy are the dominant factors that shape trade and foreign investment relationships. Nevertheless, changes at the microeconomic level associated with new technologies can affect particular industries or sectors of the economy in ways that are unrelated to international trade. In addition, changes in currency exchange rates, technology, interest rates, and the business cycle, among other things, can affect the overall state of the economy in ways that can outweigh the effects of trade agreements, given the already highly open nature of the U.S. economy. For the United States, exports account for about 13% of U.S. GDP and support over 11 million jobs, or about 8% of a total of 141 million workers in the U.S. economy.12 Imports also support a broad spectrum of jobs, including wholesale and retail trade, transportation, and various other services, among others. As a result of the small share of trade-related jobs in the U.S. economy relative to other sectors, most economists argue that international trade is only one among a number of forces that determine total U.S. employment, real wages, or the distribution of income.13

Labor Supply

Over the long run, the national birth rate, improvements in productivity, and flows of immigration/emigration, among other things, affect the overall supply of labor in the economy. Although trade agreements arguably have no impact on the fundamental supply of labor in the economy, the level and extent of globalization of the economy has broadened the definition of the labor market. As a result, the labor market itself has become more globalized, especially with the opening of major markets to international trade and the growing use of new technologies. The shares of national income that go to labor as wages also depend on the overall demand for labor in the economy relative to the supply and the overall level of utilization of the other factors of production in the economy, all of which can change over the course of the business cycle and during periods of pronounced structural transformation.

As an economy expands, greater demands are placed on labor and other factors of production. At some stages of the business cycle, labor may reap a larger share of the rewards of production, while at other stages, a greater share of the rewards may accrue to the owners of production. In addition, structural changes in the economy can reshuffle capital and labor in the economy in ways that may alter the share of income that goes to labor and capital. Such structural changes also can reflect changes in technology that place a greater emphasis on certain types of skills. In addition, as technology is spread internationally, emerging economies can similarly experience improvements in productivity that may place additional competitive pressures on U.S. workers in some industries and at some skill levels. While such structural changes can be unsettling to some workers and sectors of the economy, other conditions such as economic stagnation are potentially more unsettling since all workers and sectors in the economy would be affected negatively.14

Firm and Job Turnover

In a dynamic economy such as the United States, firms and jobs are constantly being created and replaced as some economic activities expand, while others contract, reflecting both microeconomic and macroeconomic developments. These processes would be expected to occur during the implementation period of a trade agreement, but they would occur even in the absence of international trade. This constant change, however, complicates efforts to isolate the impact of a trade agreement on the structure of the economy from other dynamic forces that are constantly reshaping the economy. Moreover, various industries and sectors evolve over time at different speeds, reflecting differences in technological advancement, productivity, and efficiency. International trade may add to these forces to provide added impetus to both growing and declining industries.

Those sectors of the economy that are the most successful in developing or incorporating new technological advancements generate greater economic rewards and are capable of attracting greater amounts of capital and labor. In contrast, those sectors or individual firms that lag behind are less capable of attracting capital and labor and confront ever-increasing competitive challenges. Indeed, depending on the overall state of the economy, some sectors may need to relinquish some capital and labor in order for others sectors to grow to avoid economic stagnation. Also, advances in communications, technology, and transportation have facilitated a global transformation of economic production into sophisticated supply chains that span national borders and defy traditional concepts of trade that potentially can involve a greater share of the labor force in trade-related activities.15 How firms respond to these challenges likely will determine their long-term viability in the market place.

Job Churning

Another factor that complicates attempts to equate a specific trade agreement, or even trade in general, with job gains or losses in the economy is the constant turnover in jobs, referred to as "churn," taking place in the U.S. economy. At the plant level, job openings may come from new business openings or expansions at existing facilities, including those that are used to support increased exports. Job losses may come from voluntary departures, involuntary discharges, or business closures for any reason, including bankruptcy, personal choice, an inability to compete in the domestic market, import competition, or production shifts. In 2015, there was an average of 141.1 million jobs in the U.S. economy, of which 11.7 million jobs, or about 8%, were supported directly and indirectly by exports. At the same time, there were 7.6 million gross jobs gained in the economy and 6.7 million gross jobs lost, accounting for 5.4% and 4.8%, respectively, of the total number of jobs in the economy.16 This combined share of 14.3% (the combined shares of gross jobs gained and lost) reflects annual churning in the labor market, or an amount that is greater than both the number of jobs in the economy that are supported by exports and the projected impact on labor that potentially could arise from the TPP.

Adjustment Costs

International trade may not have a determinative role in shaping the U.S. economy as a whole, but economic theory recognizes that trade can affect the economy through a number of channels, including through increased competition. Economic theory also recognizes that some workers, firms, and communities in the economy may experience a disproportionate share of the short-term adjustment costs associated with shifts in resources stemming from greater international competition. There may also be instances in which foreign firms engage in unfair competition or trade-distorting practices. Most trade models do not contain enough consumer information to estimate these potential costs and benefits or enough industry and employment data to determine which specific jobs or which specific firms might be affected negatively or positively by a particular trade agreement. Although the attendant adjustment costs for businesses and workers are difficult to measure, some estimates indicate that they potentially are significant over the short-run. For some communities, closed plants can result in depressed commercial and residential property values and lost tax revenues, with effects on schools, public infrastructure, and community viability.17

Some estimates indicate that the short-run costs to workers who attempt to switch occupations or switch industries in search of new employment opportunities as a result of trade-related dislocations may be "substantial."18 In a study of the impact of trade liberalization on occupations, a number of economists used detailed microeconomic data to conclude that trade liberalization has a small effect on wages and jobs at the industry level, but that it provided an additional impetus within the economy for workers to shift their employment among sectors of the economy, particularly from the manufacturing sector to the services sector.19 The study also concluded that workers who switched jobs as a result of trade liberalization generally experienced a reduction in their wages, particularly in occupations where workers performed routine tasks. These negative income effects were especially pronounced in occupations exposed to imports from lower-income countries. In contrast, occupations that were associated with exports, generally higher skilled jobs, experienced a positive relationship between rising incomes and the growth in export shares.

Trade Models

Trade models used to analyze FTAs are part of a class of economic models referred to as computable general equilibrium models (CGE) that incorporate data on trade and a range of domestic economic variables, including an industry input-output (I-O) table,20 employment, and labor data, on as many as 100 countries. The most commonly used CGE economic model and database is the Global Trade Atlas Project (GTAP), located at Purdue University,21 that is used to estimate changes in trade (exports and imports) from changes in tariff rates and tariff rate quotas.22 CGE trade models are widely used and have proven to be helpful in estimating the effects of trade liberalization in such sectors as agriculture and manufacturing where the barriers to trade are more easily identifiable and quantifiable. The United States International Trade Commission (USITC), economists Peter A. Petri and Michael G. Plummer, and the World Bank all use the GTAP model for their simulations. In contrast, economists Jeronim Capaldo and Alex Izurieta use a different model to develop their estimates of the impact of TPP. Due to the unique nature of the model and the approach used by Capaldo and Izurieta, this model and its estimates are given a relatively lengthy treatment in this report.

CGE models are long-run microeconomic models that have been used widely and tested thoroughly. The models provide estimates of the distribution of potential gains and losses expressed as proportional effects (percentage increases or decreases in trade) for various sectors, relative to certain baseline economic projections. Modelers argue that the microeconomic approach is justified because trade policies operate through microeconomic channels by tracing changes in trade policy to national productivity levels, wages, and incomes.23 Although the limitations of the models are well-known (see earlier sections), the models arguably represent a rigorous, data-centric approach to estimating the economic effects of trade agreements. Trade models also use data that represent well-established trade relationships between countries, which means they are limited in their ability to estimate the impact of a new trade agreement on goods or services that previously had not been traded due to barriers or on trade between countries that previously had a limited trade relationship.

Given the size and complexity of the CGE models, they must necessarily operate with a number of assumptions. One such assumption is that the economies in question are operating at full employment. While some experts question the assumption of full employment, it does not seem unreasonable considering the long-term time frame generally required for most trade agreements to be fully implemented. During this time, the economy would be expected to return to its long-term growth path at or near full employment. Over the estimating period, a persistently low level of unemployment is unlikely to have a significant impact on the results of the models, given the multitude of other assumptions involved in generating the estimates. In addition, during the implementation period, it seems questionable to assume that the rate of unemployment would persist at levels that would be high enough to have a significant impact on the estimates. In most cases, either the economy would be expected to return to full employment solely through market forces, or the government would be expected to intervene by adopting Keynesian-style stimulative macroeconomic policies (changes in tax rates or government spending) to move the economy toward full employment.

As a result of the large number of countries that often are included in trade models and the vast amounts of trade data used, the models necessarily must sacrifice some level of precision in their estimating abilities. The models are intended to provide insight into the mechanisms by which changes in tariffs or other parameters may affect changes in trade flows among a set of countries. As a consequence, trade models aggregate vast amounts of data into a manageable size, for instance by reducing more than 17,000 individual commodities into about 50 categories and over 150 countries into 29 different country and geographic regions. As a result, tariffs in the models represent weighted averages of tariffs for the commodities that are aggregated into these basic groups. This procedure tends to mask the importance of those products within the aggregate that have high tariffs rates, which often are the target of new trade agreements.

Trade models generally do not incorporate assumptions about the speed with which tariff changes affect the relevant economies, leaving it to the modelers to make assumptions about how quickly changes in tariff rates will be passed along in goods prices and about the timing of any adjustments. These models also make no assumptions about the basic input-output structure of the economy and do not attempt to adjust this structure to account for economic or technical changes that lead an industry to substitute one factor for another. This assumption is important, because standard economic theory indicates that changes in goods prices, whether from changes in tariff rates or from some other source, give rise to changes in the demand for labor and capital and, therefore, that price changes ultimately will alter the basic input-output structure of the economy. Since most large trade models originally were developed with the intent of analyzing the economic effects of such broad multi-country trade agreements as the Uruguay Round, this lack of precision was not considered to be an important drawback. However, this lack of precision may be an issue when the models are used to estimate the effects of bilateral and plurilateral free trade agreements where the overall amount of trade, and therefore the impact of the agreement, generally would be expected to be less than that of a WTO-style multilateral agreement.

Trade models such as the CGE differ from large macroeconomic models that are used to forecast changes in the rate of growth of gross domestic product (GDP), wages, taxes, or jobs. As a result, trade models do not yield precise estimates of the number of jobs that will be affected by any particular trade agreement. In response, some groups have used various methods and proxy estimators to assess the potential impact of trade agreements on jobs, which have produced a wide range of estimates. As examples of these approaches, some groups have used such indicators as trade deficits, or estimates of the number of jobs in the economy that are supported by exports, to develop estimates of the impact of trade and trade agreements on jobs in the economy. These models may face important limitations of data and theoretical and practical issues that make it difficult to derive precise estimates of the impact of a particular trade agreement on the economy.24

Overview of Economic Estimates of the TPP

This section provides an overview of various studies, their assumptions and a description of the models used to estimate the economic impact of the proposed TPP on U.S. trade, employment, and GDP relative to a baseline projection. The studies were selected because they are widely cited and are affecting the public policy debate about TPP.

United States International Trade Commission

The United States International Trade Commission (ITC) is tasked by Congress to provide economic assessments of U.S. trade agreements:25 it released a comprehensive assessment of the economic impact of the TPP agreement in May 2016. The ITC used the GTAP model (see above) to estimate changes in trade (exports and imports) from changes in tariff rates and tariff rate quotas. The ITC also adjusted the GTAP model to provide a more detailed estimate of the impact of the TPP on foreign investment and trade in services. In addition, the ITC:

- Used a qualitative approach to estimate the economic impact commitments on government procurement, competition, state-owned enterprises, and intellectual property.26

- Made some assumptions about the evolution of the U.S. and world economies without the TPP in five-year steps to 2047, including a straight-line projection of annual U.S. growth rate of 2%.

- Attempted to make the traditional GTAP model more dynamic by incorporating projections of capital accumulation, labor availability, and growth rates for population and gross domestic product (GDP) developed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the International Labor Organization (ILO). The model simulations also include potential trade policy changes that would be expected to occur in the absence of TPP.

- Modified the standard GTAP model to include the 12 TPP countries and to include various regions27 and 56 industry sectors.

- Adjusted the model to account for dynamic labor supply effects by assuming that labor supply would expand or contract as real wages rise or fall and that skilled and unskilled labor would receive the largest share of the gains in GDP. The GTAP model does not capture the employment and age effects in the short run, but reflects such changes in its long-run forecasts 28

- The simulations assume that nations are at full employment and will take full advantage of reduced tariffs and increases in tariff-rate quotas.

The results of the GTAP model are expressed as proportional effects (percentage increases or decreases or changes in dollar amounts) for a number of variables, relative to a projection of the economy, which serves as the baseline condition for the modelling exercise. According to this analysis, by 2032, U.S. annual real income would be $57.3 billion (0.23 percent) higher than the baseline projections, real GDP would be $42.7 billion (0.15 percent) higher, annual employment would be 0.07 percent higher (128,000 full-time equivalents), and the capital stock would increase by 0.18% with TPP, as indicated in Table 2.

Table 2. ITC Estimated Economy-Wide Effects of TPP

(in billions of dollars; percentage change from baseline projections to 2032 and 2047)

|

2032 |

2047 |

|||

|

Real Income |

$57.3 |

0.23% |

$82.5 |

0.28% |

|

Real GDP |

$42.7 |

0.15% |

$67.0 |

0.18% |

|

Employment (full time equivalents, thousands) |

128.2 |

0.07% |

174.3 |

0.09% |

|

Capital stock |

$171.5 |

0.18% |

$343.5 |

0.24% |

Source: Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Likely Impact on the U.S. Economy and on Specific Industry Sectors, United States International Trade Commission, Publication No. 4607, May 2016, p. 70.

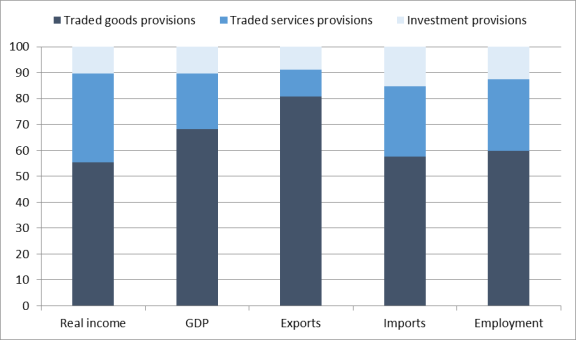

The ITC also estimated the share of the dynamic U.S. economy-wide effects of TPP by 2032 related to three groups of provisions: traded goods, services, and investment on five economic areas—real income, GDP, exports, imports, and employment—indicated in Figure 1. This analysis indicates that the largest share of the overall gains from TPP arise from provisions related to traded goods (reductions in tariffs, tariff quotas, and non-tariff measures).

|

Figure 1. ITC Estimated Share of Gains in U.S. Real Income, GDP, Exports, Imports, and Employment From Major Provisions of TPP (shares in percentage) |

|

|

Source: International Trade Commission. |

In addition, annual U.S. exports and U.S. imports with TPP partners are projected to be $57.2 billion (5.6%) and $47.5 billion (3.5%) higher, respectively, relative to baseline projections, as indicated in Table 3. Of this amount, annual exports and imports with new FTA partners under TPP are projected to increase by $34.6 billion (18.7%) and $23.4 billion (10.4%), respectively by 2032. This data indicate that the majority of growth in U.S. exports is with new TPP partners. Overall, annual U.S. exports to the world are projected to increase by $27.2 billion and imports are projected to increase by $48.9 billion by 2032 under TPP, reflecting projected increases in U.S. real incomes, changes in real international prices, and some diverting of trade away from non-TPP countries toward TPP countries.

Table 3. ITC Estimated Effects of TPP on U.S. Trade

(in billions of dollars; changes relative to baseline projections to 2032 and 2047)

|

Exports |

Imports |

|||

|

Trade with TPP partners |

$57.2 |

5.6% |

$47.5 |

3.5% |

|

New FTA partners |

$34.6 |

18.7% |

$23.4 |

10.4% |

|

Existing FTA partners |

$22.6 |

2.7% |

$24.2 |

2.1% |

|

Trade with the world |

$27.2 |

1.0% |

$48.9 |

1.1% |

Source: Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Likely Impact on the U.S. Economy and on Specific Industry Sectors, United States International Trade Commission, Publication No. 4607, May 2016, p. 71.

Similar to previous studies of FTAs, the ITC analysis of the TPP estimated the effects of liberalizing tariffs and nontariff measures (NTMs) on goods. The largest U.S. tariff reductions for TPP countries that currently do not have a trade agreement with the United States are for certain footwear, sugars and sugar-containing products, titanium downstream products, and wearing apparel. The largest reduction in tariffs on U.S. exports by TPP countries that currently do not have a trade agreement with the United States include exports of beef, footwear, and corn grain.29

The ITC study also examined the effects of TPP on specific industries. According to this analysis, gains in output and employment would be driven by changes in the agriculture and food sector, while output and employment in the manufacturing, natural resources and energy sectors would fall slightly as resources would be shifted from these sectors to other sectors in the economy, as indicated in Table 4. Shifts in employment and changes in the use of resources reflect the changes in tariff rates that would provide incentives for resources to shift from other sectors of the economy to those sectors in which foreign tariff rates were reduced. Global U.S. exports of services were estimated to be $4.8 billion higher by 2032, while services exports to TPP countries was projected to be 10.8 % ($16.6 billion) higher, and exports of services to non-TPP countries were projected to be 1.9% ($11.8 billion) lower.

Table 4. ITC Estimated Broad Sector-Level Effects of TPP on U.S. Output, Employment, and Trade

(in billions of dollars; changes relative to baseline estimates in 2032)

|

Exports |

Imports |

Output |

Employment |

||||

|

Agriculture and food |

$7.2 |

2.6% |

$2.7 |

1.5% |

$10.0 |

0.5% |

0.5% |

|

Manufacturing, natural resources, and energy |

$15.2 |

0.9% |

$39.2 |

1.1% |

$-10.8 |

-0.1% |

-0.2% |

|

Services Trade Total |

$4.8 |

0.6% |

$7.0 |

1.2% |

$42.3 |

0.1% |

0.1% |

|

Services Trade with TPP countries |

$16.6 |

10.8% |

$2.1 |

2.5% |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

Services Trade with non-TPP countries |

$-11.8 |

-1.9% |

$4.9 |

1.0% |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Source: Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Likely Impact on the U.S. Economy and on Specific Industry Sectors, United States International Trade Commission, Publication No. 4607, May 2016, p. 73, and p. 337-338.

The ITC study also examined the effects of the agreement on removing certain non-tariff measures on trade in services and cross-border investment among member economies. In order to estimate changes in services trade as a result of the TPP, ITC adjusted the standard GTAP model to reflect the impact of liberalizing cross border trade in services by estimating the tariff equivalent value of existing barriers to trade in services.30 This estimating process used data published in academic articles and an indirect approach to derive tariff equivalents of barriers to trade in services. The TPP would remove restrictions on trade in services on a negative list basis, meaning that all services that are not explicitly excepted would be covered by the agreement's provisions. In addition, it includes broad disciplines on ensuring the ability to transmit data across borders and prohibiting data-localization measures (except for services). These estimates indicate that output for the U.S. services sector would be $42.3 billion higher (0.1% increase) under TPP relative to the 2032 baseline, as indicated in Table 5. Services exports were projected to increase by 0.6% and services imports by 1.2% by 2032. Employment in all services sectors except transportation was projected to be higher by 2032 under TPP.

Table 5. ITC Estimated Effects of TPP on U.S. Output, Employment,

and Trade in Services

(in millions of dollars; changes relative to baseline estimates in 2032)

|

Exports |

Imports |

Output |

Employ-ment |

||||

|

Services |

$4,797.4 |

0.6% |

$6,962.5 |

1.2% |

$42,342.6 |

0.1% |

0.1% |

|

Wholesale and retail trade |

$848.7 |

2.5% |

$542.4 |

1.2% |

$7,447.5 |

0.1% |

0.1% |

|

Transportation, logistics, travel, and tourism |

$-1,258.4 |

-1.1% |

$1,770.5 |

1.5% |

$-719.9 |

0.0% |

-0.1% |

|

Communications |

$877.7 |

2.8% |

$306.4 |

1.2% |

$2,845.6 |

0.2% |

0.1% |

|

Financial services |

$-12.1 |

0.0% |

$787.8 |

1.1% |

$1,520.0 |

0.1% |

0.1% |

|

Insurance |

$34.4 |

0.1% |

$703.5 |

1.1% |

$707.9 |

0.1% |

0.0% |

|

Business services |

$4,575.5 |

1.6% |

$2,031.5 |

1.2% |

$11,576.0 |

0.2% |

0.1% |

|

Recreational and other services |

$-687.8 |

-1.5% |

$199.3 |

0.9% |

$1,749.8 |

0.1% |

0.1% |

Source: Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Likely Impact on the U.S. Economy and on Specific Industry Sectors, United States International Trade Commission, Publication No. 4607, May 2016, p. 35.

The ITC adjusted its modelling process to account for potential changes in direct investment that could stem from the TPP. The ITC used a four-step process to make its estimate. In the first step, the ITC calculated how much the TPP would change investment restrictions by using the OECD's (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) foreign direct investment Regulatory Restrictiveness Index [RRI], which covers 42 sectors and subsectors in 31 countries.31 Next, the ITC calculated how changes in the RRI would affect foreign affiliate sales for host countries and foreign affiliate home countries. In the third step, the ITC used a modified GTAP model to calculate how changes in foreign affiliate sales would affect productivity in each sector in each TPP country. Finally, the ITC estimated how the changes in productivity would affect macroeconomic variables in the United States.32 Since the United States is considered to be largely open to foreign direct investment, the ITC concluded that TPP is not expected to alter investment inflows in a significant way. The United States does not have FTAs with five of the TPP countries (Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Vietnam); the ITC estimates that the TPP could increase U.S. direct investment into these countries.33

Peterson Institute for International Economics

An analysis conducted by Peter A. Petri and Michael G. Plummer and published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics34 also used the GTAP model, assumed full employment, and made some adjustments to the standard GTAP model to estimate the economic impact of the TPP. These adjustments generated a more positive impact on trade in services and a greater response by foreign investment than the ITC study. This estimate concluded that the agreement would increase U.S. income and directly generate jobs in the U.S. economy. The study also estimated that the TPP could increase U.S. annual GDP by $131 billion, or 0.5% of GDP, and could increase annual exports by $357 billion, or 9.1% of U.S. exports, by 2030 when the TPP would be expected to be fully in force, as indicated in Table 6.

Table 6. PIIE Estimated Changes in Baseline GDP With the TPP, 2015-2030

(in billions of 2015 dollars)

|

Baseline (billions of dollars (2015) |

Change with TPP (billions of dollars (2015) |

||||||

|

2015 |

2020 |

2025 |

2030 |

2020 |

2025 |

2030 |

|

|

TPP members |

$28,969 |

$32,971 |

$37,094 |

$41,011 |

$98 |

$291 |

$465 |

|

United States |

18,154 |

20,736 |

23,372 |

25,754 |

29 |

88 |

131 |

|

Japan |

4,214 |

4,462 |

4,693 |

4,924 |

39 |

91 |

125 |

|

Canada |

1,981 |

2,227 |

2,472 |

2,717 |

8 |

22 |

37 |

|

Australia |

1,704 |

1,986 |

2,292 |

2,590 |

1 |

8 |

15 |

|

Mexico |

1,339 |

1,598 |

1,868 |

2,169 |

3 |

11 |

22 |

|

Malaysia |

349 |

444 |

553 |

675 |

7 |

28 |

52 |

|

Singapore |

320 |

380 |

437 |

485 |

2 |

8 |

19 |

|

Chile |

269 |

329 |

397 |

463 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

|

Vietnam |

209 |

281 |

378 |

497 |

7 |

22 |

41 |

|

Peru |

219 |

287 |

363 |

442 |

1 |

6 |

11 |

|

New Zealand |

192 |

217 |

241 |

264 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

|

Brunei |

20 |

24 |

27 |

31 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Non-TPP members |

$52,066 |

$63,652 |

$77,596 |

$92,790 |

$13 |

$28 |

$27 |

|

Europe |

17,893 |

19,746 |

21,451 |

23,189 |

12 |

34 |

48 |

|

China |

11,499 |

16,058 |

21,689 |

27,839 |

-1 |

-8 |

-18 |

|

India |

2,210 |

3,086 |

4,197 |

5,487 |

0 |

-2 |

-5 |

|

Korea |

1,384 |

1,672 |

1,967 |

2,243 |

-1 |

-5 |

-8 |

|

Indonesia |

927 |

1,240 |

1,687 |

2,192 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

|

Taiwan |

511 |

619 |

707 |

776 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Thailand |

411 |

516 |

656 |

812 |

-1 |

-4 |

-7 |

|

Philippines |

329 |

436 |

547 |

680 |

0 |

-1 |

-1 |

|

Hong Kong |

300 |

358 |

412 |

461 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

|

WORLD |

$81,035 |

$96,623 |

$114,690 |

$133,801 |

$111 |

$319 |

$492 |

Source: Petri, Peter A.; and Michael G. Plummer, The Economic Effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership: New Estimates, Working Paper Series, WP 16-2, The Peterson Institute for International Economics, January 2016.

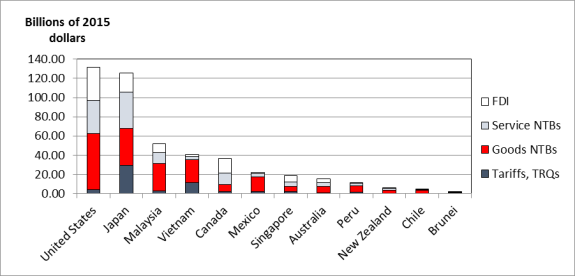

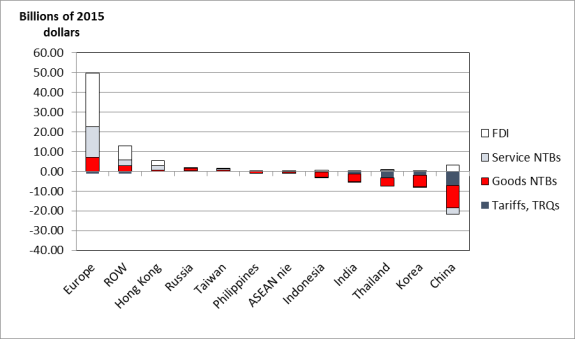

In the short run, the model scenario estimated that the potential for unemployment in the U.S. economy would be equivalent to about 0.1% of U.S. annual GDP.35 This increase in GDP is comprised of four components: (1) increased flows in foreign direct investment; (2) reduced non-tariff barriers (NTBs) to trade in goods; (3) reduced in non-tariff barriers to trade in services; and (4) cuts in tariff rates, as indicated in Figure 2. Similar in some respects to the ITC study, which attributed the largest gains from TPP to provisions in the agreement that affect traded goods, the authors estimate that the largest economic gains from TPP will arise from reductions in non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for goods and services. While incorporating estimates of NTBs allows for a more complete analysis, it also introduces an increased degree of uncertainty, since the value of NTBs is not observed directly, but must be estimated. Also, the authors estimate that annual global GDP will increase by $492 billion by 2030, and Japan, Malaysia, and Vietnam will experience large increases in GDP, in large part because they are the countries with the highest existing trade barriers in certain sectors. Countries potentially experience the largest economic gains from trade agreements by lowering trade barriers and increasing domestic competition.

Among non-TPP countries, Europe is projected to experience an increase in GDP of about $50 billion by 2030, due to increased exports to TPP countries that experience gains in real incomes and by increases in exports of services due to liberalization of services trade and foreign investment by TPP members. China, India, and Thailand, which are direct competitors to TPP countries, are projected to lose income. South Korea is projected to lose some of the economic gains it has experienced under the South Korea-United States FTA, as indicated in Figure 3.

The authors also estimate that the TPP likely will raise U.S. wages, and alter the composition of jobs in the economy, but not alter the overall level of U.S. employment, similar to the estimates by the ITC. Both capital and labor are expected to benefit from the agreement, although labor's share is projected to increase somewhat more as a proportionate share of the total amount of benefits. Given these benefits, the authors argue that each year the agreement is delayed will result in a $94 billion permanent loss to the U.S. economy. The authors further estimate that the agreement could add about 19,000 jobs annually to the overall number of jobs gained and lost annually in the economy, or jobs that are eliminated in one sector, but added in another, or job churn. The authors also project that using a different and more expansive, but potentially unrealistic, approach would be to estimate all jobs that are directly and indirectly displaced by imports, which potentially could total 53,000 U.S. jobs, adding an estimated 0.1% to annual labor market turnover.36

The estimates by Petri, et. al. are based on projections of annual growth in GDP and national income for the participants in the TPP agreement from 2015 to 2030, relative to the baseline projections, with a large share of the benefits accruing after 2020. The model incorporates provisions agreed upon in the final version of the agreement, but also necessarily incorporates some subjective assessments of the nature and economic impact of the 30 chapters that comprise the agreement. The analysis also projects increased inward and outward investment flows, reflecting reduced barriers to foreign investment and a more attractive investment climate. This analysis projects that U.S. exports of certain types of goods will increase, including, primary goods (agriculture and mining), advanced manufacturing, and services, while imports are expected to increase in labor-intensive manufacturing products and in some types of services.

According to the authors, the projection of investment flows in the model attempts to reflect the dynamic nature of economic activity in the TPP economies by assuming that the agreement potentially could induce additional firms into exporting. Such an assumption likely would make the estimated impact of the agreement larger than would projections using models that did not incorporate this assumption. This assumption also would require a number of subjective decisions, since trade models generally do not contain the types of microeconomic behavioral data on firms that would be necessary to forecast accurately which firms might decide to engage in exporting directly as a consequence of a particular trade agreement. The model also relies on estimates of the annual value of national income for the participants that stems from the trade agreement and a projection of the annual rates of GDP growth for the countries involved.

The authors projected U.S. GDP in 2025 of $20 trillion and by dividing the GDP projection by the projected number of workers in the U.S. labor force in 2025 of 168 million, they derive an equivalent value of $121,000 ($20 trillion / 168 million) for the average income for each U.S. worker in 2025. The authors also estimate the FTA will generate annual gains in income for the U.S. economy that will rise to $59 billion annually, rising slowly to reach $79 billion annually by 2025.37 The authors argue that the estimated annual income effect can be equated to an annual increase in employment, which some observers have interpreted to mean that the data imply a net positive annual gain in employment over the baseline projection of 487,000 jobs ($59 billion / $121,000) by 2025, more than twice the number of annual job gains projected by the ITC.

The authors argue, however, that the estimated employment effects will consist primarily of shifts in employment among sectors of the economy as a result of the full employment assumption. The authors caution that

the trade-employment relationship is complicated and not well understood. For one thing, the relationship is very sensitive to underlying macroeconomic circumstances. The macroeconomic analysis of employment effects, in turn, requires very different models from those used to understand the microeconomics of international competition.38

The authors also state that they purposely did not attempt to estimate the number of jobs that might arise from the agreement.39 They argue that "[t]he reason we don't project employment is that, like most trade economists, we don't believe that trade agreements change the labor force in the long run. The consequential factors are demography, immigration, retirement benefits, etc. Rather, trade agreements affect how people are employed, and ideally substitute more productive jobs for less productive ones and thus raise real income."40

World Bank

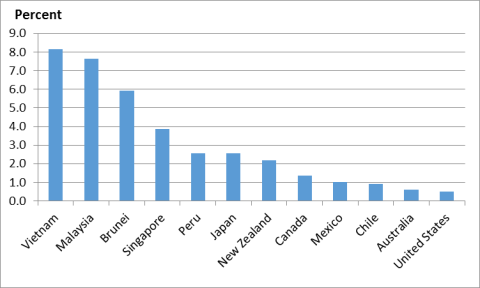

Another estimate of the potential economic impact of the TPP was published by the World Bank, based in part on the study by Petri and Plummer, who served as co-authors.41 The estimate also used the GTAP model, with some adjustment, and the full employment assumption. These adjustments assume that trade in goods and services will increase as a result of regulatory convergence among TPP and non-TPP members. The model simulation projects that by 2030 relative to baseline projections, the TPP would increase member country GDP on average by 1.1%, ranging from over 8% for Vietnam to 0.5% for the United States, or about the same as the projections by Petri and Plummer for the Peterson Institute, as indicated in Figure 4. This upward shift in GDP stems from model simulations that the agreement would stimulate a shift in resources towards more productive firms and sectors and expand export markets, as indicated by conventional trade theory. The impact on members of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA: United States, Canada, and Mexico) would be about 0.6% of GDP, due to the low share of trade in GDP, primarily in the United States, and the already-low average tariff rates.

Spillover effects on non-TPP countries are expected to be small, but positive as a result of greater regulatory harmonization. For non-TPP members, the trade diversion effects are projected to be limited, as a result of the large share of trade that currently occurs among TPP countries. Consequently, aggregate losses to non-TPP countries are estimated to amount to 0.1% of GDP by 2030. Only South Korea, Thailand, and some other Asian economies are expected to experience losses exceeding 0.3% of GDP. The study also projects that the agreement will lift trade among the TPP members by 11% by 2030.

According to the authors, the benefits of the agreement will materialize slowly, but accelerate towards the end of the projection period. These benefits would be derived mostly from reductions in non-tariff measures and measures that benefit services. The authors estimate that 15% of the projected increase in GDP would be due to lower tariff rates, while non-tariff measures would account for 53% of the increase in exports of goods and 51% of the increase in exports of services.42 This estimate also "allows for the emergence of trade in products not previously traded between pairs of countries."43

The authors adopt three assumptions that are important to deriving their results:

- 1. Cumulative rules of origin—are expected to encourage regional production networks. The authors estimate that the rules of origin will lead to the replacement of 40% of imported inputs with higher-cost inputs from TPP members to qualify for low TPP tariffs.

- 2. Existing services barriers—estimated indirectly from bilateral trade flows, based in part on results from the U.S.-South Korea FTA.

- 3. Non-discriminatory trade liberalization—more transparent regulatory approaches are expected to facilitate increased trade with non-TPP members.44

The authors expect that over the long run the TPP will accelerate shifts among the various sectors of the economy. For advanced economies, these shifts likely will favor traded services, advanced manufacturing, and for some resource-rich economies, primary products and investments. Developing countries are projected to experience growth in manufacturing, especially in unskilled labor-intensive industries, and in some production of primary products. These shifts translate into a higher value placed on skilled workers in the advanced economies and an increase in wages of unskilled workers in developing economies. For the United States, the authors project that changes in real (adjusted for inflation) wages are expected to be small as wages for unskilled and skilled wages increase by 0.4% and 0.6%, respectively, by 2030, or that wages for skilled workers are expected to rise by more than wages for unskilled workers.

This approach attempts to incorporate the effects of the agreement's rules of origin and potential economic benefits that arise from greater regulatory convergence among the TPP members. The authors conclude that a common rules approach will increase intra-regional trade in affected industries.45 In the model, trade with non-TPP members depends on existing standards in non-member counties and on hypothetical mutual recognition agreements on the rules of origin. Such agreements would provide limited preferential treatment to some trade with non-TPP members, but such countries currently are not party to the agreement. As a result of changes in regulatory standards alone, trade with non-TPP members are projected to vary by the level of economic development. Trade with non-TPP developed economies is expected to increase, while trade with non-TPP developing economies is expected to decrease, because firms in developing countries are expected to be hurt more by more stringent regulatory standards in some markets and are less able to gain from the types of economies of scale that are available to firms in developed economies. Trade between TPP and non-TPP countries is also expected to be affected by rules of origin with countries that have adopted mutual recognition with permissive rules of origin and are likely to fare better than countries with more restrictive rules.

The authors conclude by arguing that

Against the background of slowing trade growth, rising non-tariff impediments to trade, and insufficient progress in global negotiations, the TPP represents an important milestone. The TPP stands out among FTAs for its size, diversity, and rulemaking. Its ultimate implications, however, remain unclear. Much will depend on whether the TPP is quickly adopted and effectively implemented, and whether it triggers productive reforms in developing and developed countries. Broader systemic effects, in turn, will require expanding such reforms to global trade, whether through TPP enlargement, competitive effects on other trade agreements, or new global rules.46

Tufts University, Global Development and Environment Institute

Tufts University's Global Development and Environment Institute sponsored another study of the economic impact of the TPP, using the United Nations Global Policy Model (GPM).47 This study differs markedly from the previous studies, because the GPM model is not a GTAP-type CGE model and the structure of the model and the assumptions that are used differ substantially from those used in the three previous examples. As a result of these differences, the authors reach the non-standard conclusion that all TPP members will experience job losses, which are projected to total 771,000 jobs, with the largest losses occurring in the United States, as indicated in Table 7.

The study also estimates that the TPP will negatively affect growth and employment in non-TPP countries, with Europe losing 879,000 jobs and non-TPP developing countries projected to lose about 4.5 million jobs by 2025. The authors argue that these effects increase the risk of "global instability and a race to the bottom, in which labor incomes will be under increasing pressure."48 The authors also argue that their model is based on "more realistic assumptions about economic adjustment and income distribution," than the standard CGE model.49 They term their model a "demand-driven, global econometric" macroeconomic model, compared with the microeconomic feature of the GTAP model. Previously, the authors used this model to develop estimates of the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP), a study that has come under critical review by trade economists.50

Table 7. Capaldo and Izurieta Estimated Changes With TPP, 2015-2025

(in percentage change and thousands)

|

Net Exports (% of GDP) |

GDP Growth (%) |

Employment (thousands) |

|

|

Total TPP |

-771 |

||

|

United States |

0.20% |

-0.54% |

-448 |

|

Canada |

-0.58 |

0.28 |

-58 |

|

Japan |

1.54 |

-0.12 |

-74 |

|

Australia |

0.71 |

0.87 |

-39 |

|

New Zealand |

2.13 |

0.77 |

-6 |

|

Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam |

1.69 |

2.18 |

-55 |

|

Chile and Peru |

1.18 |

2.84 |

-14 |

|

Mexico |

0.20 |

0.98 |

-78 |

|

Non-TPP, Developed |

-3.77 |

-879 |

|

|

Non-TPP, Developing |

-5.24 |

-4,450 |

Source: Capaldo, Jeronim and Alex Izurieta, Trading Down: Unemployment, Inequality, and other Risks of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, GDAE Working Paper No. 16-01, Global Development and Environment Institute, Tufts University, January, 2016.

Basic Assumptions

The authors reject the standard CGE model on a number of grounds. In particular, they argue that the standard model (1) incorporates "dubious" assumptions about full employment; (2) does not distinguish between wage-earners and profit-earners in ways that obscure potential changes in the distribution of income; (3) assumes that real wages increase at the same rate as the growth in productivity; (4) assumes constant balances in the government account and in the current account; and (5) assumes that there will be an increase in foreign direct investment.51 Due to these assumptions and the nature of the GPM model, the analysis that follows is necessarily more detailed and expansive than that for the previous studies, which are more conventional in their approach.

The UN GPM model is not a trade model under conventional definitions in large part because the model uses very little trade data. Similar to other models, the UN model provides estimates of the impact of the TPP on a limited number of individual countries (the United States, Japan, Mexico, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, in the case of this analysis), while it aggregates all other countries into regional blocs. In contrast to the GTAP model, however, the GRM model includes only four broad international trade sectors: energy products; primary commodities; manufacturing; and services. The authors argue that this aggregation is not significant, because their study focuses on "macroeconomic impacts."52

In deriving their results, the authors borrow estimates from other studies, generated primarily from CGE models, of the potential trade effects of the TPP, since the GPM model itself does not contain enough trade data to generate such estimates. As previously explained, CGE models typically estimate changes in goods trade only unless they are modified to estimate changes in services trade, investment, or consumer welfare. The authors offer the unconventional conclusion that the TPP will result in job losses not only in each TPP country, but negative dislocations in non-TPP countries as well. Without a detailed explanation of the results by the authors, it is difficult to assess how the model derived the results, or how various assumptions may have affected the results. The authors proceed by

- Following the "widely held belief" that TPP would affect international competition by "pushing countries to increase trade performance." This is accomplished by producers in each country lowering their prices and cutting their costs in order to preserve their market shares. The authors "assume" that this process would lower nominal unit labor costs through the combined actions of business managers and "policymakers" who negotiate lower wages;

- Contending that this process would affect the distribution of income between labor and business profits in favor of profits for businesses, thereby lowering labor's share of income, because the TPP would affect the incentives for countries to "tilt income distribution in favor of profits," which the authors analyze by "estimating the impact of changes in unit labor costs on international market shares;"53

- Assuming that economic sectors of the economy that are affected negatively by the TPP agreement would create a demand shortfall in the economy, because, as a sector contracts, "other sectors may suffer as well," leading to "large job losses and drive the economy into recession;"54

- Arguing that the TPP would push firms and other borrowers to seek higher returns in order to avoid losing investors. The authors assume that a higher profit rate necessarily requires a lower labor share of income;

- Asserting that inflows of foreign income "depend on a country's fiscal policy," which would require countries to adjust to attract foreign capital; and

- Concluding by asserting that, "since all TPP countries would want to preserve their market shares, we assume that they will engage in a race to the bottom, pushing labor shares downward across the whole TPP bloc."55

Other Assumptions

This series of steps requires assumptions and assertions that, in a number of cases, contradict standard economic concepts, often without explanation or the requisite theoretical or analytical basis. As previously indicated, standard trade theory indicates that trade agreements such as the TPP generally are expected to generate a number of economic effects, both positive and negative, although the net sum is expected to be positive for all participating countries. This study, however, focuses exclusively on the negative effects, or on the adjustments costs, even though trade models are not capable of precisely estimating these adjustment costs. As noted above, the costs and benefits associated with trade agreements do not accrue to the economy at the same speed: costs to the economy in the form of job losses generally are experienced in the initial stages of the agreement, while the benefits to the economy generally accrue over time.

The authors also criticize the typical CGE model assumption of full employment. Given the long-term time horizon of most trade agreements to be fully implemented, assumptions of full employment generally are not thought to be unreasonable, since economic activity is expected to adjust to shocks by returning to its long-run growth pattern of full employment.56 The adjustment of the economy to shocks is thought to be either automatic through market adjustments, or through deliberate adjustments in macroeconomic policies (either through fiscal policies including adjustments in tax rates or in government spending, or in monetary policies). Also, at an unemployment rate of 4.7%, the United States is effectively nearing its theoretical full-employment limit. Concurrently, measures of capacity utilization, or the amount of slack productive capacity in the economy, indicate that levels in early 2016 are below long-run rates of utilization. With excess productive capacity and with tightening labor markets, benefits going to labor may well rise relative to returns to businesses as firms compete for workers by offering higher wages.

The net positive economic effects from trade agreements are expected to arise from lower tariff rates that, in turn, increase the amount of trade among all TPP participants. Lower import costs increase choices for consumers, improve their real purchasing power, and improve long-run productivity in ways that affect the overall efficiency of the economy. In the TPP, businesses are anticipated to improve their performance through the mutual lowering of market-distorting tariffs and non-tariff barriers during the implementation period rather than through a "race to the bottom," as assumed by the authors. The TPP also is expected to yield other long-term productivity gains through mutual reductions in informal market barriers that can stifle competition within national economies, create market inefficiencies, and distort international trade.

Adjustment Costs

As previously indicated, the negative effects of trade agreements, generally thought to be economic inefficiencies in production, job losses, and downward pressure on wages in import-competing industries, are referred to as "adjustment costs," because economies are expected to shift, or adjust, capital and labor within the economy from declining sectors to growing sectors of the economy in response to market forces. The authors, however, make no assumptions about shifting resources within the economy in response to market signals to more productive activities and base their analyses exclusively on the negative adjustment costs. International trade, both bilaterally and multilaterally, can also be affected by a broad range of economic factors, including economic recessions or financial crises and such new entrants into the global economy as the former Eastern European countries, India, and China, that can affect the global supply of labor and, therefore, the wages of workers in certain import-sensitive industries.

According to the IMF, for instance, the effective global labor market quadrupled over the past two decades through the opening of China, India, and the former Eastern bloc countries. The United States and other developed economies access this global labor market through (1) imports of final goods and services, including intermediate goods; (2) offshoring of production; and (3) immigration. According to the IMF, the internationalization of labor contributed to rising labor compensation in the advanced economies by increasing productivity and output, while emerging market economies benefited from rising wages.57 Increased exports from labor-intensive developing economies would be expected to push down wages, adjusted for productivity, for unskilled workers in developed economies, thereby reducing labor's share of income. Nevertheless, workers in developed economies could still be better off if the positive effects of increased trade and productivity on the economy are positive, as expected. The IMF also concluded that globalization is only one of several factors that have acted to reduce the share of income accruing to labor in advanced economies and that technological change likely has played a larger role in affecting the distribution of income in the economy, especially for workers in lower-skilled sectors.58

Estimates of losses of jobs and GDP generated by the GPM model are weighted exclusively in favor of the projected adjustment costs of the TPP, since the model is not capable of capturing the full range of economic effects that are expected with the TPP. In addition, the demand-driven GPM macro model does not incorporate important supply side effects that arise from trade agreements and, therefore, assumes large losses in employment, output, and wages in all TPP partners. As a result, the GPM estimates adjustment costs in a way that precludes any positive gains for either consumers or producers in contravention of traditional economic thought and decades of experience.

GPM Model Limitations

In part, the author's estimates of losses in jobs and in GDP arise from the limited amount of trade data and the absence of tariff or industry data in the GPM model. While the authors argue that such limited trade data are not necessary in the context of their macroeconomic model, trade agreements affect the economy as a whole through the accumulated effects at the microeconomic level. As a result, without detailed micro data on tariffs, trade, and industry-specific employment and output, it is not clear how the GPM macro model captures either the trade creation or the trade diversion effects, or the benefits to consumers' choices or real incomes that arise from increased access to a greater variety of goods and services and to lower-priced imports. The GPM model also does not capture the gains in productivity and efficiency that arise in the economy from the adjustment of capital and labor from import-sensitive sectors to other sectors of the economy.

The GPM model seems to preclude any shift in capital and labor among sectors within the economy from declining sectors to more productive sectors. Also, the authors focus on wages as a key government policy variable. Among economies that possess differing levels of technological development and productivity, however, trade likely is driven more by the value of wages relative to the level of productivity than a simple comparison of nominal wages across countries. Although the United States is a relatively high wage country, it also is a high productivity country, which makes it possible to export high capital-intensive, high technology-intensive products. Even U.S. agriculture is considered to be a high technology export activity relative to other countries given the vast amount of land available for agriculture in the United States and a high degree of mechanization.

Wages and the Distribution of Income

The authors assume, without providing any evidence from their model in their report, that the TPP will generate only negative adjustment costs. They also assume that businesses and policymakers will undertake to negotiate lower wages for all workers in the economy. This assumption seems to suggest that the government will replace private labor markets by injecting itself into the process of negotiating private labor contracts and setting wage rates throughout the economy. This assumption also seems to arise from the notion that international trade comprises such a commanding role in the economy that the adjustment costs of trade agreements will force wages down throughout the economy and worsen the distribution of income between workers and owners. This assumption seems to be imposed on the model, since the GPM model itself lacks any detailed industry, production, or labor occupational data. As previously indicated, lower tariffs increase opportunities for export-oriented industries. Also, the limited role of trade in the U.S. economy relative to other forces and the relative openness of the economy seem to be at variance with the commanding role that trade plays in the authors' estimates.

Anticipated Economic Gains