Introduction

Thirty years after having enacted it, Congress is reviewing the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reform Act.1 Deeply controversial at the time, Goldwater-Nichols augmented command relationships, strengthened the role of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, enhanced joint procurement, and redesigned personnel incentives in order to prioritize "jointness" among the services—a characteristic that the U.S. Department of Defense demonstrably lacked prior to the reforms. Congress is now determining whether further reforms are needed, and if so, what those might be. To that end, the Senate Armed Services Committee has held a number of hearings over the second session of the 114th Congress, specifically focused on defense reform. Spurred on by congressional interest, the DOD has undertaken its own "Goldwater-Nichols" review of its internal structures, and plans to present suggested legislative changes to Congress in the coming weeks and months.2

Among defense scholars, observers, and practitioners there has been a near-constant drumbeat to reform one aspect or another of the DOD since its inception in 1947.3 Most observers agree that after 30 years, a comprehensive review of the Goldwater-Nichols legislation is warranted.4 Further, there appears to be a broad consensus among observers that DOD must retain its strength while becoming considerably more agile in order to enable the United States to meet a variety of critical emerging national security challenges.5

Yet agreement seemingly ends there. There appears to be little consensus regarding what changes are needed within DOD and what specific direction reform ought to take. Discussions have begun to coalesce around a number of proposals, including reforming defense acquisition processes, further strengthening the Joint Staff, reducing Pentagon staffs, and better empowering the services in the "joint" arena. However, ideas vary on how, specifically, to accomplish those goals. Disagreement also exists as to whether or not reorganizing DOD alone will be sufficient. Some observers maintain that a reform of the broader interagency system on national security matters is needed.6

This lack of consensus appears to result from diverging ideas as to what are the key challenges with the way DOD—and the national security architecture more broadly—is organized and operates. The variety of views reflects the complexity of these institutions. One observer refers to the present DOD reform debate as akin to a "Rorschach test," noting that defense experts tend to diagnose what they believe to be critical national security challenges based on their own experiences and priorities.7 Without a common understanding of the root causes of these organizational frictions, solutions to the national security organization challenge differ considerably. The complex nature of the Pentagon and national security bureaucracies adds to the many challenges of DOD management reform.8

Despite these obstacles, the case for reforming the Department of Defense is gaining traction among observers. The international security environment has grown ever more complex, in manners unforeseen when the Goldwater-Nichols legislation was enacted.9 This report is designed to assist Congress as it evaluates the many different defense reform proposals suggested by the variety of stakeholders and institutions within the U.S. national security community. It includes an outline of the strategic context for defense reform, both in the Goldwater-Nichols era and today. It then builds a framework to understand the DOD management challenge, and situates some of the most-discussed reform proposals within that framework. It concludes with some questions Congress may ponder as it exercises oversight over the Pentagon.

The Strategic Context Leading to the Goldwater-Nichols Act

The changes that the Goldwater-Nichols legislation made to the Department of Defense, and in particular, the way that DOD conducts military operations, are in many ways central to how the Department conducts military operations today. Indeed, many organization design decisions that were taken—in particular, clarifying the chain of command for more effective prosecution of joint operations and improving the quality of military advice provided to senior leaders—are so fundamental to the way DOD does business today that it is difficult to recall that it once conducted its operations quite differently.

DOD Challenges Prosecuting Joint Operations

Nearly 35 years ago, the Reagan Administration came into office largely convinced that the Pentagon was highly inefficient in its business and acquisition practices, and therefore established a Blue Ribbon Commission on Defense Management on July 15, 1985. The commission, which was headed by David Packard (founder of Hewlett-Packard and former Deputy Secretary of Defense), was instructed to "study defense management policies and procedures, including the budget process, the procurement system, legislative oversight, and the organizational and operational arrangements, both formal and informal, among the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Organization of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Unified and Specified Command system, the Military Departments, and the Congress."10 While the study explored many facets of the DOD and its management, the overall objective was to identify efficiencies and associated cost savings.

Yet several prominent shortcomings with the manner in which DOD conducted its military operations suggested to some observers that deeper organizational and structural challenges were plaguing the Department, and that these issues were not being sufficiently addressed by the Packard Commission. Congress therefore saw deep concerns develop as examples mounted that significant reforms to the Department of Defense were needed. Those examples included after action reviews of the following incidents: Desert One, Operations in Grenada, and the Marine barracks bombing in Beirut.

Desert One, 1980

After six months of planning, preparation, and training, in 1980 the U.S. military initiated a raid to rescue 53 American hostages being held in Tehran after the 1979 uprising in Iran. The operation failed. Only six of the eight helicopters arrived at Desert One, the rendezvous point in the middle of Iran, and a further helicopter suffered significant mechanical problems. Determining that the remaining helicopters did not have sufficient capacity to proceed, the mission was aborted. As the helicopters departed, one crashed into a C-130 aircraft carrying fuel and other servicemembers. All told, the United States lost eight military personnel, seven helicopters, and one C-130 aircraft, and left behind weapons, communications equipment, secret documents, and maps, all without making contact with the enemy.11

After action reviews of the mission suggested that a key underlying problem with the mission was that the services were unable to operate together. As one observer wrote:

[T]he participating units trained separately; they met for the first time in the desert in Iran, at Desert One. Even there, they did not establish command and control procedures or clear lines of authority. Colonel James Kyle, U.S. Air Force, who was the senior commander at Desert One, would recall that there were, "four commanders at the scene without visible identification, incompatible radios, and no agreed-upon plan."12

The inability of the services to operate together effectively led many to believe that the needs and interests of the individual military services were being prioritized over joint mission requirements. As the President's National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee:

One basic lesson [to be learned from the failure of the mission] is that interservice interests dictated very much the character of the force that was used. Every service wished to be represented in this enterprise and that did not enhance cohesion and integration.13

Grenada, 1983

Although Operation Urgent Fury (the 1983 U.S. military operation in Grenada to rescue U.S. medical students and other American Nationals after a Marxist coup) was generally viewed as a success, tactical and operational shortcomings marred the mission and became the subject of subsequent controversy. A primary issue was that units from the different U.S. military services conducting the mission proved unable to communicate with each other.14 Army elements could not use their equipment to communicate with sailors on the USS Guam to coordinate naval air support, and at times took drastic action to find ways to correct the problem. For example, some Army officers from the 82nd Airborne Division flew by helicopter to the USS Guam to begin coordinating air support, and even borrowed a Navy UHF radio to continue to do so while back in Grenada. Unfortunately, the Army officers operating the borrowed radio did not have the appropriate Navy clearance codes, rendering the equipment useless. It was also reported that one 82nd Airborne officer, frustrated with the situation, used an AT&T calling card from a civilian pay phone to call Fort Bragg and ask their higher headquarters to address the problem.15 Subsequent analysis led observers to conclude that the inability of the services to formulate and execute joint equipment and communications requirements was at the heart of the problem.16

After action reviews also concluded that fire support from the Navy to the Army was a "serious problem," and that the coordination between the two services ranged from "poor to non-existent."17 The two services did not coordinate their assault plans prior to the operation, and went into combat without any real sense of each other's requirements, leading observers to conclude that the episode illustrated the "inadequate attention paid to the conduct of joint operations."18 Another issue was the lack of sophisticated mapping capabilities. Troops had to use tourist maps.19 In conjunction with the aforementioned communications challenges, the lack of intelligence led to what some believed were unnecessary casualties. U.S. Navy Corsair airplanes accidentally attacked a mental hospital; two days later, they hit an a 82nd Airborne brigade headquarters building, wounding 17 U.S. soldiers.20 These issues, in conjunction with others including the lack of a designated ground commander and logistics issues, led a Senate study to conclude:

The operation in Grenada was a success, and organizational shortcomings should not detract from that success or from the bravery and ingenuity displayed by American servicemen.

However, serious problems resulted from organizational shortfalls which should be corrected. URGENT FURY demonstrated that there are major deficiencies in the ability of the Services to work jointly when deployed rapidly. The Services are aware of some of these problems and have created a number of unites and procedures to coordinate communications... However, in Grenada, they either were not used or did not work. More fundamentally, one must ask why such coordinating mechanisms are necessary. Is it not possible to buy equipment that is compatible rather than having to improvise and concoct cumbersome bureaucracies so that the Services can talk to one another? Are the unified commands so lacking in unity that they cannot mount joint operations without elaborate coordinating mechanisms?

It further concluded:

The inability to work together has its roots in organizational shortcomings. The Services continue to operate as largely independent agencies, even at the level of the unified commands.21

Beirut, 1983

Another major incident prompting congressional concern was the terrorist bombing of the Marine Barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, in October 1983, which killed 241 servicemen. Subsequent reviews of the tragic incident revealed significant shortcomings in the chain of command, which in the case of the Marine mission in Lebanon was described as "long, complex and clumsy."22 Analysis also revealed that the Unified Combatant Commander, in this instance, the Commander of United States European Command, had limited authority to direct service components within his area of responsibility to improve standards, especially when those components came from a different service. Despite the fact that U.S. European Command sought to improve the security for U.S. forces in Lebanon, its actual authority to do so was limited. General Smith, Deputy Commander of U.S. European Command at the time, said:

I really felt the Marines didn't work directly for me. On paper, they were under our command, but in reality, they worked for the commander in chief, U.S. Naval Forces Europe, our naval component. They had their own operational and administrative command lines, which flowed from the naval component commander. I felt that antiterrorism training was primarily a navy and marine service issue. We didn't have any control over that. We could advise, of course, but no more.23

Prior to the enactment of the Goldwater-Nichols legislation, the services played a much larger role in the prosecution of military campaigns than they do today. The formal, de facto operational chain of command led from the President, to the Secretary of Defense, to the Unified Combatant Commanders via the Joint Chiefs of Staff.24 The services were responsible for administrative functions. In practice, however, the situation was quite different. The services played a direct role in operations through their component commands (today, examples of service component commands include U.S. Army Pacific or U.S. Navy Europe).25 Each service had a component command within a Combatant Commander's area of responsibility, and these service component commands often prioritized orders from their service's headquarters in Washington over those of their Unified Combatant Commander.26 This dynamic was described by former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Crowe:

Like every other unified [combatant] commander, I could only operate through the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine component commanders, who stood between me and the forces in the field.... Component commanders reported to their own service chiefs for administration, logistics and training matters, and the service chiefs could use this channel to outflank the unified commander. There was sizeable potential for confusion and conflict.27

This dynamic played out during U.S. operations in Lebanon:

Washington was bypassing EUCOM.... An investigation uncovered thirty-one units in Beirut that reported directly to the Pentagon. Orders to the carrier battle group off Lebanon came "straight from the jury-rigged 'Navy only' chain of command" that originated with the Chief of Naval Operations. Only after the Navy had set plans for fleet operations were superiors in the operational chain of command informed.28

Taken together, the Desert One, Grenada, and Marine Barracks bombing incidents suggested to Congress that deeper systemic and organizational issues were at work, preventing DOD from prosecuting joint operations successfully. In particular, issues with the operational chain of command, the quality of military advice given to civilian leaders, and the dominance of the services within the Department of Defense at the expense of joint requirements were all areas that Congress believed needed significant improvement.

The Goldwater-Nichols Legislation

Over time, many in Congress became convinced that the package of reforms identified by the Packard Commission–primarily focused on efficiency–were necessary, but not sufficient, to meet the challenges besetting the Pentagon at the time. Pointing to perceived operational shortcomings, some legislators, Administration officials, and military leaders became convinced that the organizational design of the Pentagon itself needed significant restructuring. The point was hammered home by then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff David Jones, who testified:

It is not sufficient to just have resources, dollars and weapon systems; we must also have an organization which will allow us to develop the proper strategy, necessary planning, and the full warfighting capability.... We do not have an adequate organizational structure today.29

The House and Senate Armed Services committees therefore decided to conduct their own independent reviews of the Pentagon's structure, processes, and incentives, a process that lasted almost five years. Through this process, Congress drew the conclusion that the structure of the Department of Defense, as configured at that time, was organized primarily to serve the needs and priorities of the military services. While sensible in theory given the history of the U.S. Armed Forces, as a practical matter this encouraged inter-service rivalry that, in turn, led to operational failures.

|

The Joint Chiefs of Staff Prior to the passage of the Goldwater-Nichols Act, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS)—and the Joint Staff (JS) that supported it—were both very different organizations than they are today. Just prior to the passage of the Goldwater-Nichols Act, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the service chiefs of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps were all statutory members. Their collective responsibility was to provide military advice to the Secretary of Defense, the National Security Council and the President. The Joint Chiefs of Staff was also tasked with supervising, but not commanding, the Combatant Commands, maintaining command and control networks with forces worldwide, and consulting with foreign militaries. The Joint Staff, which was dwarfed in size by the staffs of the services, supported the work of all four service chiefs and the Chairman. The structure was the result of a 1958 compromise between President Eisenhower, on the one hand, who sought to bring greater unity of command to Pentagon structures and, on the other, the military services, which sought to ensure that the needs and requirements of their individual departments were effectively represented during national security discussions. By the 1980s, it became clear to some observers in the Pentagon and Congress that the system was not operating effectively and that the Joint Chiefs of Staff was rendering to national leaders what amounted to poor quality joint military advice. Former Secretary of State Dean Acheson is said to have quipped, "JCS papers reminded him of the little old lady who didn't know how she felt until she heard what she had to say."30 Reasons for this inadequate advice included the following:

The Goldwater-Nichols Act sought to address these structural deficiencies by making the Chairman, rather than the collective Joint Chiefs of Staff, the principal military advisor to the President, creating the position of Vice-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, making the Joint Staff responsible to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and creating career incentives for officers to acquire experience working in joint environments. Sources: David C. Jones, "Reform: The Beginnings," as found in: Dennis J. Quinn (ed), The Goldwater-Nichols DOD Reorganization Act: A Ten-Year Retrospective (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 199); David C. Jones, "Why the Joint Chiefs of Staff Must Change," Presidential Studies Quarterly (vol 12, no. 2, Spring 1982); Barry M. Blechman and William J. Lynn, Toward a More Effective Defense: Report of the Defense Organization Project (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Ballinger Publishing Company, 1985). |

Contents of the Act

The Goldwater-Nichols Act sought to accomplish a number of objectives designed to improve the overall effectiveness of the Department. Still, the legislation's primary thrust was to improve the interoperability, or jointness among the military services at strategic and operational levels. Section 3 of P.L. 99-433 stated:

In enacting this Act, it is the intent of Congress, consistent with the congressional declaration of policy in section 2 of the National Security Act of 1947 (50 U.S.C. 401)—

(1) to reorganize the Department of Defense and strengthen civilian authority in the Department;

(2) to improve the military advice provided to the President, the National Security Council, and the Secretary of Defense;

(3) to place clear responsibility on the commanders of the unified and specified combatant commands for the accomplishment of missions assigned to those commands;

(4) to ensure that the authority of the commanders of the unified and specified combatant commands is fully commensurate with the responsibility of those commanders for the accomplishment of missions assigned to their commands;

(5) to increase attention to the formulation of strategy and to contingency planning;

(6) to provide for more efficient use of defense resources;

(7) to improve joint officer management policies; and

(8) otherwise to enhance the effectiveness of military operations and improve the management and administration of the Department of Defense.

It sought to accomplish these goals through a number of changes, including the following:31

- Clarifying the military chain of command from operational commanders through the Secretary of Defense to the President;

- Giving service chiefs responsibility for training and equipping forces, while making clear that they were not in the chain of command for military operations;

- Elevating the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff relative to other service chiefs by making him/her the principal military advisor to the President, creating a Vice Chairman position, and specifying that the Joint Staff worked for the chairman;

- Requiring military personnel entering strategic leadership roles to have experience working with their counterparts from other services (so-called "joint" credit);32 and

- Creating mechanisms for military services to collaborate when developing capability requirements and acquisition programs, and reducing redundant procurement programs through the establishment of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition.33

Despite Congress's considerable deliberations, at the time consensus did not exist that significant DOD reforms were needed. Opposition to the Goldwater-Nichols Act was fierce in some quarters, in particular the Navy and Marine Corps; they believed that its implementation would severely degrade the ability of the services to wage the nation's wars.34 The legislation itself passed committee by one vote.35

Evaluations of the Goldwater-Nichols Legislation

Five years later, the U.S. military successfully conducted Operation Desert Storm and other associated operations (such as Operation Provide Comfort). The clarification of the operational chain of command, as well as the advances in jointness that were made as a result of the Goldwater-Nichols legislation, were viewed by many as instrumental to that success.36 Then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell testified that, "You will notice in Desert Storm nobody is accusing us of logrolling and service parochialism and the Army fighting the Air Force and the Navy fighting the Marine Corps. We are now a team. The Goldwater-Nichols legislation helped that."37 Indeed, as Admiral Leighton Smith wrote about the mission to provide humanitarian relief to the Kurds in Northern Iraq (Operation Provide Comfort):

The good news about this operation was that from a command relationship perspective, Jim Jamerson, and later our Chairman, General Shalikashvili, knew exactly for whom they worked and to whom they reported. That joint task force, like the five others we put together during my 21 months in the J-3 [Joint Staff Operations] job, all reported directly to the CINC, bypassing the component commanders ... and the inevitable service guidance that existed in the Pentagon in the pre-Goldwater-Nichols days ... there was none of the direct calls from Washington to the commander in Turkey or the individual service component commanders, to give operational guidance or demand information that should rightfully go through the unified commander.38

Still, some observers maintain that the act has produced unintended consequences that ought to be mitigated. Namely, some contend that Goldwater-Nichols may have gone too far in prioritizing joint over individual service requirements and that a better balance must be struck.39 Specifically, one of the most commonly voiced criticisms pertains to the act's provisions for joint personnel management, and whether the joint officer requirements lead to the development of officers with an appropriate mix of service and joint experiences.40 Others maintained (and still do) that the act did little to address perceived inefficiencies in defense spending. It also failed to curtail the growth of staffing in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Defense Agencies.41 Finally, while many believe that the quality of military advice provided to the Secretary of Defense and the President has improved as a result of the act's strengthening of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff position, some contend the Department still has room for improvement when developing its strategies and plans.42

Another school of thought maintains that the act introduced changes that were necessary, but not sufficient, to meet the challenges of the post-Cold War environment, and that further reform of the national security architecture was needed. In particular, the experience of post-Cold War contingency and stability operations demonstrated the benefit of adequately trained and resourced interagency partners (for example, State, USAID, Treasury, and so on).43 Ten years after the initial passage of the Goldwater-Nichols Act, then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Shalikashvili observed:

A strong, well-understood link among the Departments of Defense, State, Justice, Commerce and the entire interagency community will be vital. Look at many of the most recent challenges to U.S. national interests around the world: Rwanda and Zaire, Bosnia, Haiti, the Arabian Gulf. In every one of these operations, success required the involvement of a wide variety of interagency participants.44

On balance, the Goldwater-Nichols Act has generally been lauded as a major breakthrough in effective defense management, but there are differences of opinion on the ultimate outcome of the Goldwater-Nichols legislation. Some contend that the act may have produced unintended consequences and unnecessarily diminished the services; in the view of others, there are areas in which the reform agenda did not go far enough. As described in the next section, some of these views are being carried forward into the current debate on defense reform.

The Strategic Context in 2016

Thirty years later, the strategic environment has shifted dramatically. Since the enactment of the Goldwater-Nichols legislation, a number of important historical events have taken place, starting with the end of the Cold War. Subsequently, the United States performed crisis management and contingency operations globally, in theaters including Iraq, the Balkans, Somalia, and Colombia. After the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, the United States undertook major counterinsurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as a number of smaller operations as part of its "global war on terror."

Emerging Threats

The international security environment was already demanding when the Goldwater-Nichols legislation was enacted, yet most observers agree it has become significantly more complex and unpredictable in recent years.45 This is challenging the United States to respond to an increasingly diverse set of requirements.46 As evidence, observers point to a number of recent events, including (but not limited to)

- the rise of the Islamic State, including its military successes in northern Iraq and Syria;

- the strength of drug cartels in South and Central America;

- Russian-backed proxy warfare in Ukraine;

- heightened North Korean aggression;

- Chinese "island building" in the South China Sea;

- terror attacks in Europe;

- the ongoing civil war in Syria and its attendant refugee crisis; and

- the Ebola outbreak in 2014.

Indeed, as Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter remarked before the House Armed Services Committee in March 2016:

Today's security environment is dramatically different—and more diverse and complex in the scope of its challenges—than the one we've been engaged with for the last 25 years, and it requires new ways of thinking and new ways of acting.47

What makes today's issues uniquely problematic—perhaps even unprecedented—is the speed with which each of them has developed, the scale of their impact on U.S. interests and those of our allies, and the fact that many of these challenges have taken place—and have demanded responses—nearly simultaneously.48 Further complicating matters, U.S. adversaries appear to be using tactics and operations that are provocative, but which tend to fall short of necessitating a large-scale military response. Adapting U.S. military and civilian defense institutions to operate effectively in these "grey zone" conflict spaces, wherein adversaries are not immediately obvious, and interests are advanced using a combination of military and nonmilitary tactics, is becoming an increasingly important priority for DOD leaders.49 Altogether, these dynamics have created the extremely high degree of complexity with which the United States must grapple, placing increasing demands on the U.S. national security architecture generally, and the Department of Defense in particular.

The Fiscal Challenge

These changes in the international security landscape are occurring against a backdrop of U.S. defense "austerity," a common shorthand term for fiscal restrictions on the DOD budget. According to some observers as early as 2010:

The aging of the inventories and equipment used by the services, the decline in the size of the Navy, escalating personnel entitlements, overhead and procurement costs, and the growing stress on the force means that a train wreck is coming in the areas of personnel, acquisition and force structure.50

|

Background: The Federal Deficit and the Budget Control Act The Budget Control Act of 2011 was enacted in response to congressional concern about rapid growth in the federal debt and deficit. The federal budget has been in deficit (spending exceeding revenue) since FY2002, and incurred particularly large deficits from FY2009 to FY2013. Increases in spending on defense, lower tax receipts, and responses to the recent economic downturn all contributed to deficit increases in that time period. In FY2010, spending reached its highest level as a share of GDP since FY1946, while revenues reached their lowest level as a share of GDP since FY1950. The BCA placed statutory caps on most discretionary spending from FY2012 through FY2021. The caps essentially limit the amount of spending through the annual appropriations process for that time period, with adjustments permitted for certain purposes. The limits could be adjusted to accommodate (1) changes in concepts and definitions; (2) appropriations designated as emergency requirements; (3) appropriations for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO; e.g., for military activities in Afghanistan); (4) appropriations for continuing disability reviews and redeterminations; (5) appropriations for controlling health care fraud and abuse; and (6) appropriations for disaster relief. Source: CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects, by Grant A. Driessen and Marc Labonte |

Yet some have argued that the Budget Control Act of 2011 (and subsequent amendments) placed significant constraints on the Department's ability to address these challenges, allocate monies toward critical priorities, and effectively divest from obsolete facilities and equipment programs.51 As the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review Panel asserted:

the defense budget cuts mandated by the Budget Control Act of 2011, coupled with the additional cuts and constrains on defense management under the law's sequestration provision ... have created significant investment shortfalls in military readiness and both present and future capabilities. Unless reversed, these shortfalls will lead to greater risk to our forces, posture and security in the near future.52

The impact of financial reductions imposed by the Budget Control Act, along with the way DOD resources are allocated, has led many observers to conclude that there has been a significant, deleterious impact on the readiness and capability of the force.53 Yet the United States now spends over $600 billion per year on activities associated with the DOD (including the base budget and Overseas Contingency Operations account)54 which is, according to some estimates, comparable to the total spent by the next eight largest defense spending countries combined.55 This often perceived mismatch between inputs and outputs appears to be one key strategic-level impetus for the reform of DOD's acquisition systems. According to H.Rept. 114-102:

The committee believes that reform of the Department of Defense is necessary to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the defense enterprise to get more defense for the dollar. This is necessary to improve the military's agility and the speed at which it can adapt and respond to the unprecedented technological challenges faced by the nation.56

In summary, compared to the strategic context 30 years ago, the current international security environment is generally characterized by increased, and more dynamic, security challenges. Despite the considerable size of the DOD budget, fiscal constraints have forced the Department to make tough choices on priorities, and have significantly affected force readiness, among other things. In short, some scholars have found that requirements are going up while resources are plateauing, at best.57 This is leading many observers to wonder whether necessary programmatic "belt tightening" will sufficiently enable the Department of Defense to effectively meet today's and tomorrow's threats.

Why Reform DOD Today?

It is within this context that Congress has undertaken its review of the Goldwater-Nichols legislation, as well as a broader review of DOD's organization and structure. Observers in this process seem to approach the problem differently, based upon their own experiences with, or within, the Department of Defense.58 Some maintain that Goldwater-Nichols led to the positioning of the United States military as the "finest fighting force" in the world, and therefore question whether major DOD reforms are needed.59 Yet there are several fundamental, first order questions that seem to be driving the current examination of DOD's structure. These include, but are not limited to the following:

- Why, after the expenditure of nearly $1.6 trillion and over 15 years at war in Iraq and Afghanistan, has the United States had such perceived difficulty translating tactical and operational victories into sustainable political outcomes?60

- Why, despite the expenditure of now over $600 billion per year on defense, is the readiness of the force approaching critically low levels, according to senior military officials, while the number of platforms and capabilities being produced are generally short of perceived requirements?61

- Why, despite tactical and operational level adaptations around the world, is DOD often seen as having difficulty formulating strategies and policies in sufficient time to adapt to and meet the increasingly dynamic threat environment of the 21st century?62

- What challenges, in either structure or process (or both), might lead to perceived DOD difficulties in executing current military operations while simultaneously planning for and obtaining resources for future capabilities?

No single answer exists for these questions. No one decision, no one individual, no one process led to these arguably less than desirable outcomes. Taken together, however, the issues raised by these questions suggest the systemic nature of the challenges with which the Department of Defense appears to be grappling. In other words, they suggest that DOD's organizational architecture and culture may merit serious review and analysis.

|

A Secretary at War In his memoirs, former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates expresses considerable frustration with the manner in which the Pentagon prosecuted wars. "Even though the nation was waging two wars, neither of which we were winning, life at the Pentagon was largely business as usual."63 He goes on to identify a number of structural issues he experienced with DOD, including the following:

Noting DOD's overall lack of agility, Gates finally concludes that "[t]he Department of Defense is structured to plan and prepare for war, but not to fight one." Source: Robert M. Gates, Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Press, 2014) |

The Defense Management and Reform Challenge

DOD's mission is to "provide the military forces needed to deter war and protect the security of our country."64 In order to do so, DOD must plan for current and future threats and then prepare military forces with the training and other military capabilities necessary to meet those threats. It must also propose and manage a budget appropriate to the nation's defense needs and articulate acceptable levels and areas of risk. While simple in theory, orchestrating and synchronizing these activities is a highly complex endeavor.

Hundreds of studies, comprising thousands of recommendations and tens of thousands of pages, have been dedicated to reforming the Department of Defense and its many facets. The scale and complexity of the DOD make it a uniquely challenging organization to manage. As one management expert stated in 1997:

The most difficult problem in the entire world right now is the transformation of Russia into a democratic, free-market economy. You may not realize that the second most difficult problem I can possibly envision is that of reforming the Defense Department.65

Over the duration of the Department's history, a number of Administrations have sought to improve its management and efficiency. These reforms have generally taken one of three approaches. The first advocates for more centralization, shifting more authority and resources from the military departments to joint institutions and/or Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) control in order to improve interoperability and efficiency. The second approach favors more decentralization, through retaining or bolstering semi-autonomous military services, properly guided by OSD decisionmaking and resource allocation processes, thereby promoting creativity and innovation through competition. The third "business matrix" approach attempts to infuse business management structures into existing Pentagon architectures using cross-functional teams, boards, and councils to promote collaboration.

Yet, as noted by the U.S. Commission on National Security in the 21st Century (the Hart-Rudman Commission):

The current structure of DOD's major staffs (and their functions) represents a meshwork of all three models, and the net result has been a diffusion of authority, responsibility and accountability. In many cases, the three different paradigms work at cross-purposes to obstruct and block each other. This dilutes the Department's ability to transform itself internally. It hinders the identification of problems, the development of alternative solutions, and the elevation of decisions to senior officials for resolution.66

Conceptualizing DOD's Enterprise-Level Functions

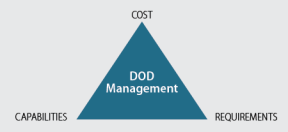

The diagram below depicts one way to think about managing the defense enterprise (see Figure 1). On behalf of the President, the Secretary of Defense must oversee and balance three distinct but highly interrelated functions that support all of DOD's activities: requirements, capabilities, and costs. These broad functions can usefully be conceptualized as three points of a triangle.

- The first, requirements, refers to the Department's work to analyze the current and future threat environment, define the missions and tasks that different DOD components must be prepared to accomplish, and organize itself in order to do so (i.e, through the Unified Command Plan).67

- DOD must then define, develop, and manage the military capabilities—in terms of equipment, training, and posture—necessary to accomplish those missions and tasks.

- Finally, DOD must manage its costs in a manner that accounts for current and future expenditures on its worldwide operations, as well as the personnel, facilities, and processes comprising the defense institution itself.

In each of these "points," the Department must identify, and to the extent possible mitigate, any risks associated with under- or over-prioritizing any particular activity or program.

|

Figure 1. DOD Enterprise-Level Management Three Core Activities |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Managing a government organization the size of the Department of Defense—with over 3 million civilian and military employees (of which 450,000 are overseas) and several hundred thousand individual buildings and structures located at more than 5,000 different locations—cannot, nor will it ever, be straightforward.68 This, in turn, makes managing and balancing the "points" of the triangle comprising DOD's activities extremely difficult.

Each point of the triangle in Figure 1 represents the actions and programs of hundreds of different organizations and units, at multiple echelons at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. The enormity of the DOD management challenge is exacerbated by the Department's internal complexity and the wide variety of external stakeholders in DOD's operations and activities (including Congress, industry, allies, and partners). As such, in many ways the challenge of DOD reform presents the characteristics of a "wicked" problem, commonly thought of as a social or cultural problem that is difficult or impossible to solve, and one in which solving one aspect of the problem often leads to new, equally formidable challenges.69 If past trends hold, reforming one aspect of the Department will almost inevitably have unintended consequences that will create new problems, likely necessitating further reform.

Efficiency vs. Effectiveness

Efficiency and effectiveness are often conflated in the defense reform debate. This is because a number of scholars and practitioners maintain that reforming the Department of Defense in order to improve its overall efficiency—defined as the "ability to do something or produce something without wasting materials, time, or energy"—will also improve DOD's effectiveness, or, its ability to accomplish its assigned tasks.70 As the logic goes, taking actions such as constraining the resources associated with DOD's bureaucracy and headquarters, or requiring the services to procure equipment in conjunction with each other, forces the Department to better prioritize its activities and allocate its resources. Yet while effectiveness and efficiency can be interrelated objectives, it is important to note that they are not the same thing. In fact, if not carefully managed, the two goals can actually work at cross-purposes with each other when pursued simultaneously.

Within the Department of Defense, the reduction and subsequent increase in the acquisition workforce may provide an example of efficiency coming at the expense of effectiveness. According to the Government Accountability Office:

The acquisition workforce of the Department of Defense (DOD) must be able to effectively award and administer contracts totaling more than $300 billion annually. The contracts may be for major weapons systems, support for military bases, consulting services, and commercial items, among others. A skilled acquisition workforce is vital to maintaining military readiness, increasing the department's buying power, and achieving substantial long-term savings through systems engineering and contracting activities.71

Concerns during the 1980s that the acquisition workforce (AW) was under-skilled and over-manned prompted the Department to reduce the number of personnel associated with the AW in the 1990s. As part of Defense budget reductions and efficiency improvements, the civilian and military acquisition workforce was reduced by 14%, and the Department began relying on contractors to perform a variety of acquisition-related functions.72 DOD also lost workers with critical acquisition skill sets.73 Subsequently, experts found that the AW was ill-prepared or suited to manage the complex and urgent contracting requirements associated with expeditionary operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.74 The Section 1423 report also noted, "[i]n general, the demands placed on the acquisition workforce have outstripped its capacity."75 Efforts to reconstitute the acquisition workforce in order to make it more effective began in earnest in 2009.76

Headquarters Reductions

Reducing the size of various headquarters has been a consistent theme of defense reformers for decades. Indeed, participants in the Goldwater-Nichols debates over 30 years ago saw the growth in Pentagon and headquarters bureaucracy as a key challenge to DOD efficiency and effectiveness. Today, the preponderance of defense scholars and experts maintain that reducing DOD bureaucracy and headquarters staffs is necessary in order to improve the Department's decisionmaking and agility while simultaneously controlling costs.77 In their view, doing so will force components across the Department to prioritize their activities and divest themselves of unnecessary functions. This rationale has, in part, led DOD to reduce its headquarters staff by 25% and Congress to restrict the amount of funding available to DOD for headquarters, administrative, and support activities.78

Implementing these reductions, however, is proving problematic. Many of the roles and missions performed by different offices around the Department have been mandated by senior leaders or Congress; staff reductions mean that the same workload is being shouldered by fewer people, leading in some instances to overworked staffs.79 Unless the Department finds ways to divest itself of certain functions or tasks, headquarters reductions could compromise DOD's effectiveness. As one observer describes this dynamic:

[A]ny reduction in staff will save a commensurate amount of resources, but it will not—without needed reforms—generate greater effectiveness. Just cutting staff ignores real problems, like our inability to collaborate across organizational lines on multifunctional problems.80

Efforts to improve fiscal efficiency without balancing the ramifications for overall mission effectiveness can create significant challenges for the Department. A number of observers maintain that the Department of Defense is a bloated organization, with too many staffs at higher headquarters. Yet the fact remains that most offices or agencies are responsible for a task or mission that was, at least at one point (if not at present), deemed critical. For example, one reason the Joint Staff is now 4,000 persons—considered by many to be too large—is due to the fact that during the disestablishment of Joint Forces Command, essential joint service functions were transferred to the Joint Staff.81 Unless or until Congress or DOD leadership deems those functions no longer indispensable, cutting staffs to improve efficiency may result in degraded mission effectiveness.

|

The Challenge of Organization Design In some ways, the design of an organization can be likened to the plumbing of a house: unseen, yet essential to its functioning. Much like plumbing, when the design of an organization proves unable to enable its intended functions, the consequences can be ugly. As an example, some maintain that one of the critical reasons that Kodak has deteriorated to such a significant degree was because it could not adapt its organization to better comprehend, and then respond to, changing market circumstances.82 As one management scholar writes, "[p]oor organizational design and structure results in a bewildering morass of contradictions; confusion within roles, a lack of coordination among functions, failure to share ideas, and slow decision-making, bring[ing] managers unnecessary complexity, stress and conflict."83 Optimizing an organization's design is a challenge that is not unique to the Department of Defense. Every organization—be it a business or public sector agency—must organize its people, processes, and structures in a manner that enables the group as a whole to achieve its objectives. Accordingly, there is no one "right" answer to organization design; rather, an organization is effectively structured when it helps its leaders define their strategy and enables that strategy to be predictably executed.84 This is why many large companies routinely revisit their organizational structures in order to remain competitive in the marketplace. Organization design theory offers an analytic lens through which observers can evaluate whether DOD is effectively structured to meet current and future objectives. Different management consultants utilize a variety of different models when testing whether an organization's structures enable the group to accomplish its objectives. In so doing, some of the key questions they ask include:85 |

|

|

Design Question |

... Applied to DOD |

|

The "First Principles" Test. What is the business's value proposition and its sources of competitive advantage? Rationale: A clear statement of what a business is good at, relative to other competitors, illuminates the core activities around which an organization ought to be designed. |

What are DOD's unique advantages in the advancement of national security, relative to other agencies and departments? Challenge: The international security environment in which DOD must operate has arguably led the Department to take on roles and missions, such as post-conflict stabilization, that some observers believe it is not ideally suited toward. |

|

The Market Advantage Test. Which organizational activities directly deliver on that value proposition—and by contrast, which activities can the company afford to perform in a way equivalent to its competition? Does the design direct sufficient management attention to the sources of competitive advantage in each market? Rationale: Those activities that are crucial to delivering on a value proposition should be prioritized and resourced above other functions. |

What are the activities DOD engages in that enable it to make its unique contribution to national security? What are the functions or areas in which the Department must build and maintain excellence? Are there functions or tasks that are better suited to other USG agencies? Challenge: the blurring of lines between peacetime and conflict, as well as DOD's assumption of many tasks that have historically been accomplished elsewhere in the executive branch, has made it difficult to establish what tasks must be accomplished to advance U.S. interests, and whether the Department of Defense ought to be prepared to conduct those broader national security missions that fall outside of military engagement. |

|

The People Test. Does the design reflect the strengths, weaknesses, and motivations of its people? What kind of leadership and culture are needed to achieve the value proposition? Which organizational practices are required to reinforce organizational intent? Rationale: Cultural values are woven into the way people behave in the workplace. Without addressing leadership and culture, employees often adhere to old practices and work around, instead of working with, a new system. |

What kinds of behavior ought DOD incentivize to achieve its organizational aims, such as promoting innovation? Challenge: augmenting personnel systems is significantly more challenging to leaders in the federal government than their counterparts in the private sector, due to the variety of internal and external stakeholders, including Congress, that influence personnel decisions. This often leads to risk-averse management, which can stifle innovation. |

|

The Redundant-Hierarchy Test. Does the design of the organization have too many levels? What, specifically, does each level of the organization add to the accomplishment of core tasks? How do "parent" units enable subordinate teams to accomplish key missions? Rationale: Too much hierarchy within an organization can impede agile decisionmaking and stifle innovation (seven or eight layers between an employee and CEO is generally believed to be the maximum supportable number of layers).86 Those levels within an organization that cannot demonstrate their value added could be candidates for elimination. |

What levels might DOD usefully eliminate in order to improve agility and encourage innovation? Challenge: In part due the fact that DOD has taken on so many roles and missions, DOD is now an organization that is simultaneously highly vertical (with many layers of management) and highly horizontal (with many offices "clearing" on any given memorandum). This is leading to what Former Under Secretary for Policy Michele Flournoy describes as the "tyranny of consensus," and poor-quality civilian and military advice.87 |

|

Drawing analogies between DOD and the private sector has clear limitations. Unlike businesses, the Department of Defense is not organized to deliver profits to its stakeholders. Further, the consequences of risks taken are measured in casualties; while failing corporations go bankrupt, DOD failure can result in national failure. Still, these design questions can help observers understand whether the organizational architecture of the Department of Defense is optimized—or not—to enable its personnel to meet current and emerging national security challenges. |

|

Framing the Problem: Current DOD Reform Concepts

While consensus on specific reform solutions remains elusive, many scholars and practitioners agree on the characteristics that DOD must have if it is to grapple effectively with current and emerging strategic challenges. Namely, many believe that the Department must be better able to respond to multiple complex contingencies around the world, both anticipated and unforeseen. Rapid adaptation and "agility" is therefore necessary.88 With respect to the latter point, as noted by Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee Mac Thornberry in January 2016:

I think there are two primary characteristics that describe the military capability that we need. And they are strength and agility. We know from sports that you can't do with one and not the other. You have to have both.89

In March 2016, Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain fleshed out his own concept of what DOD must be able to do:

I believe we have a rather clear definition of the challenge that we all must address. The focus of Goldwater-Nichols was operational effectiveness, improving our military's ability to fight as a joint force. The challenge today is strategic integration. By that, I mean improving the ability of the Department of Defense to develop strategies and integrate military power globally to confront a series of threats, both states and non-state actors, all of which span multiple regions of the world and numerous military functions.90

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) "Open Letter on Defense Reform," signed by a bipartisan group of senior defense observers and practitioners, frames the DOD reform challenge slightly differently. Instead of articulating the desired characteristics of a future DOD, they focus on some of the key organizational problems that, in their view need to be overcome:

the Defense Department, and even more so the broader U.S. national security complex, appear[s] sclerotic in their planning, prioritization, and decision-making processes. We should identify better ways to pace and get ahead of this changing environment.

Second, the defense enterprise is too inefficient. These two problems are intertwined. There appears to be significant duplication of responsibilities and layering of structure, which contributes materially to the perception that we are at risk of being outpaced and outwitted by adversaries. Moreover, our military and defense civilian personnel systems, requirements and acquisition systems, security cooperation and foreign military sales systems, and strategy, planning, programming, and budgeting systems reflect twentieth-century approaches that often seem out of step with modern best practices.91

While experts convened by CSIS could not agree on specific reform proposals, they did note that two principles should guide defense reform efforts:

First, we must sustain civilian control of the military through the secretary of defense and the president of the United States and with the oversight of Congress.

Second, military advice should be independent of politics and provided in the truest ethos of the profession of arms.92

On April 5, 2016, Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter articulated his ideas regarding defense reform and the areas within the Department that need improvement:

It's time that we consider practical updates to this critical organizational framework, while still preserving its spirit and intent. For example, we can see in some areas how the pendulum between service equities and jointness may have swung too far, as in not involving the service chiefs enough in acquisition decision-making and accountability; or where subsequent world events suggest nudging the pendulum further, as in taking more steps to strengthen the capability of the Chairman and the Joint Chiefs to support force management, planning, and execution across the combatant commands, particularly in the face of threats that cut across regional and functional combatant command areas of responsibility, as many increasingly do.93

Secretary Carter further intimated that DOD will be augmenting some of its internal processes as well as submitting statutory changes to Congress for consideration.

|

Lessons Encountered from the Long War Seeking to enable the Department of Defense to better prepare itself for future conflicts, the National Defense University conducted a study of the strengths and weaknesses of the U.S. approach to its post-September 11th campaigns. Some of the key outcomes from that study include the following: Civilian-military relations. The study identified significant strategic-level disconnects between the military staffs and the civilian leadership they supported in both the Bush and Obama Administrations. As conditions on the ground in Iraq deteriorated in 2006, President Bush decided to go against the recommendations of his military and defense leadership, and instead authorized a "Surge" of forces that was advocated by external advisors. After a series of unfortunate media missteps by several senior military leaders under the Obama Administration, a "perception formed in the minds of senior White House staff that the military had failed to bring forward realistic and feasible options, limiting serious consideration to only one, and that it had attempted to influence the outcome by trying the case in the media, circumventing the normal policy process" (p. 412). In summary, "[t]he military did not give President Bush a range of options for Iraq in 2006 until he insisted on their development, nor did they give President Obama a range of options for Afghanistan in 2009" (p. 143). Strategy Formulation and Adaptation. A gap in overall national strategy formulation and evaluation was identified by the authors. In the first instance, the authors maintain that the United States failed to fully appreciate the strategic context in which it was operating, as well as the on-the-ground political and military realities in Iraq and Afghanistan. With respect to Iraq, the study also points out that the lack of mechanisms for strategic-level reevaluation and adaptation prevented needed reassessment—and readjustment—until it was clear that the United States was on the verge of failing (p. 143). National-level decisionmaking. Noting that "both civilian and military leaders are required to cooperate to make effective strategy, yet their cultures vary widely," the authors maintain that "[c]ivilian national security decision-makers need a better understanding of the complexity of military strategy and the military's need for planning guidance." The authors go on to note that "strategy often flounders on poorly defined or overly broad objectives that are not closely tied to available means" (p. 413). In their view, military leaders must improve their ability to work with their civilian counterparts in strategy formulation. Unity of Effort. "Whole-of-government efforts are essential in irregular conflicts.... The United States was often unable to knit its vast interagency capabilities together for best effect." Furthermore, "Policy discussions too often focused on the familiar military component (force levels, deployment timelines and so forth) and too little on the larger challenge of state-building and host-nation capacity" (p. 145). Strategic Communications. "Making friends, allies, and locals understand our intent has proved difficult.... our disabilities in this area—partly caused by too much bureaucracy and too little empathy—stand in contradistinction to the ability of clever enemies to package their message and beat us at a game that was perfected in Hollywood and on Madison Avenue" (p. 15). DOD guidance has specified that the United States will no longer plan to conduct large-scale counterinsurgency or stability operations. Still, some observers maintain that these challenges, if left unresolved, will hamper DOD's efforts to wage any future military campaigns, and particularly those that require U.S. military forces to operate in "grey zone" conflicts. Source: Richard D. Hooker and Joseph J. Collins, Lessons Encountered: Learning from the Long War, (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press) 2015. |

Current Defense Reform Proposals

As noted earlier in this report, no consensus currently exists regarding specific recommendations to "fix" the Pentagon. This, in part, stems from a lack of agreement on the nature of the bureaucratic challenges currently besetting the Department of Defense and preventing it from accomplishing what many perceive to be core tasks.

During hearings held in the second session of the 114th Congress, experts recommended scores of proposals to reform DOD. These are in addition to the many other proposals advocated by a variety of scholars and practitioners across the defense and national security policy community. For purposes of bringing a degree of analytic coherence and clarity to the present discussion, CRS grouped together and condensed similar DOD reform proposals raised by experts in their testimonies to the Senate Armed Services Committee. Reform suggestions tabled outside the context of the hearings were not included. CRS then sought to better link each set of recommendations with the problems they are attempting to solve through organizing the proposals into one of four categories. Three of these categories align with the core areas of defense enterprise management articulated earlier in this report: managing costs, formulating requirements and building capabilities. The fourth category includes proposals for reforming the broader interagency national security system. This listing of defense reform proposals should be treated as illustrative of the state of the debate at present; evaluating the relative strengths and weaknesses of each set of proposals is beyond the scope of this report.

External Defense Expert Reform Proposals

During the second session of the 114th Congress, the Senate Armed Services Committee held a series of hearings to discuss areas ripe for reform within the Department of Defense. Through the duration of the proceedings, various national security experts proposed over 160 different recommendations for reforming the Pentagon. What follows below is an illustrative sample, rather than an exhaustive listing, of the many proposals suggested by experts.

Formulating Requirements

There is widespread belief among observers that the processes the Department uses to formulate its strategies and strategic requirements in order to grapple with current and emerging security challenges are "broken."94 Still, there is very little agreement on what ought to be done to address this. This category of recommendations pertains to problems identified with the way in which the Department prepares its strategies, particularly global strategies,95 and organizes itself to execute its policies. Proposals for possible reform include the following.

- Improving DOD strategy-making by:

- Generating better strategy documents. Proposals included replacing the Quadrennial Defense Review (now the Defense Strategy Review) with a classified internal defense strategy, and creating a comprehensive strategy review akin to President Eisenhower's Project Solarium.96

- Reforming the central institutions for strategy formulation. Proposals included creating an Operations versus Plans division of labor within the Office of the Secretary of Defense (akin to the J3/J5); institutionalizing "red teaming" of strategies; building a competitive process for alternative future force planning, run by the Deputy Secretary of Defense; and creating a Joint General Staff exclusively focused on strategy formulation (more on this recommendation below).

- Improving the way DOD organizes itself to accomplish strategic objectives and execute operations by:

- Augmenting the Unified Command Plan. Proposals vary, but included the elevation of United States Cyber Command to a four-star Unified Combatant Command (COCOM), the collapse of U.S. European Command and U.S. Africa Command into one COCOM,97 and the collapse of U.S. Northern Command and U.S. Southern Command into another single COCOM. Others recommended against merging the regional combatant commands. Another recommendation was to revisit altogether the regions of responsibility for geographic Combatant Commands.

- Augmenting existing command structures. Proposals vary, and are in some ways in opposition. These included placing the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the operational chain of command; giving Service Secretaries more authority for military operations and operational planning; retaining the current "J-code" staff structures of the Joint Staff; and disestablishing service component commands and instead replacing them with Joint Task Forces. It should be noted that the proposal to grant greater operational responsibility to the Service Secretaries (promoting decentralization) is in some ways the opposite recommendation to putting the CJCS in the operational chain of command (promoting jointness). Others recommended against any proposal that diminishes the authority of the Secretary of Defense to make key decisions, including placing the CJCS (or others) in the operational chain of command.

- Creating New Services, Agencies, and Institutions. Proposals included elevating U.S. Special Operations Command to a military service rather than a Combatant Command; the creation of a new U.S. cyber service; creating a Remotely Piloted Aircraft agency; and establishing a separate Joint General Staff (in addition to the current Joint Staff) that focuses exclusively on strategic-level issues, reports to CJCS, and has its own career path (rather than drawing personnel from the services). Others recommended against the creation of new services.

- Revisiting roles and missions. Proposals included reforming Special Operations Command to become the preferred option for irregular conflict; establishing a commission to review roles and missions for space; shrinking regional Combatant Commands and focusing them on engagement and relationships with foreign counterparts; and creating a better division of labor on irregular warfare.

- Streamlining and improving the decisionmaking by:

- Removing unnecessary management layers. Proposals included consolidating Secretariats and Service Staffs while retaining the Service Secretary positions; reducing the number of management layers in the bureaucracy; encouraging the Department to conduct a top-down de-layering study according to pre-agreed organization design principles, and examining areas of overlap between different DOD components (for example OSD and the Joint Staff) with a view to eliminating redundancy; reducing the number of three- and four-star commands; and eliminating the Joint Requirements Oversight Council.

- Empowering the DOD workforce. Proposals included increasing the bureaucracy's autonomy; providing staffs with better training; building greater expertise in the civilian workforce through stopping frequent assignment rotations; and better facilitating horizontal collaboration across DOD components at lower levels than the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

- Extending the tenure of the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Proposals included shifting from a two-year renewable term to one four-year term or shifting to a five-year (or longer) term.

Managing Costs98

Responding to perceptions that DOD has difficulty reigning in its finances and delivering an "appropriate" (however defined) return on its investments, recommendations in this category pertain to perceived issues in the way the Department of Defense accounts for and controls its costs. Since the Department's establishment, many of its leaders have taken issue with the way the Department manages its finances; a number of reform efforts have therefore been focused on controlling DOD costs and identifying more efficient ways to do business. In terms of recent proposals for reform proposed by defense experts in their testimonies during the first and second sessions of the 114th Congress, areas such as acquisition reform and efforts to improve efficiency, eliminate redundancies, and better prepare defense budgets are included in this group. Recommended changes include the following:

- Creating Efficiencies: Proposals included immediately cutting every program behind schedule or over budget; minimizing documentation requirements for program managers; avoiding "gold plating" (shorthand for incorporating costly and unnecessary features) of procurements; shifting jobs from active duty personnel to civilians or contractors; reviewing command relationships for cost savings; reviewing Combatant Command J-8 functions (responsible for evaluating and developing force structure requirements) to avoid duplication; authorizing another round of Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC); and outsourcing depot maintenance.

- Improving collaboration with industry. Proposals included loosening requirements to share all relevant information on technologies with commercial analogues with the government; revising contract incentives to reward success and penalize failure; reauthorizing A-76 public-private competitions processes; and encouraging leaders from industry to serve in DOD.

- Improving business practices. Proposals included running DOD personnel management like a business; taking more leaders from industry into Pentagon positions; removing requirements for incoming political appointees to divest their assets or equity in companies doing business with DOD; creating greater transparency among stakeholders; changing the measure of a program's merit from unit cost to cost per effect (i.e., cost per target engaged); establishing a management "reserve" account to address execution risks inherent in every program; and creating a Deputy Secretary position for business transformation.

- Cutting overhead/civilian workforce management. Proposals included establishing a performance management system for civilian employees; creating greater flexibility in civilian pay levels; reducing the civilian workforce but increasing compensation for high-level civilians; cutting the civilian system in half or more; permitting DOD to downsize or eliminate inefficient healthcare systems; combining the Defense Logistics Agency and Transportation Command; and legislating end strengths for military, civilians, and contractors associated with overhead and infrastructure.

Building Capabilities

Other observers have focused on whether DOD is acquiring the right personnel and materiel capabilities, in sufficient quantities and with sufficient readiness to meet 21st century security challenges. Recommendations in this category include suggested augmentations to military personnel management and training; more effectively leveraging emerging technologies; and suggested priority areas for capability development:

- Augmenting military career paths by99

- Improving military training and education. Proposals included strengthening top-level (above O-6 & O-6) military education; unifying service professional military education under a joint three-star General or Flag officer; and giving the CJCS authority to direct joint training.

- Creating more flexibility in military careers. Proposals included giving technical track officers opportunities equal to those of their colleagues in the command track; expanding "early promote" quotas and accelerating rates of advancement; reviewing DOPMA to create a more dynamic management system; making it easier to seek out and promote promising young officers; relaxing joint duty requirements; and shifting requirements for joint credit to O-8 or O-9 levels.

- Prioritizing key skill sets. Proposals included augmenting the selection and promotion of general and flag officers to prioritize strategic-level thinking; adding psychological resilience to recruiting standards; and developing foreign language requirements for serving in regional combatant commands.

- Building and leveraging technology by creating processes and systems for rapid prototyping of new capabilities. Proposals included following the JIEDDO model for lower risk technologies;100 and adopting a more tolerant approach to risk and failure on technology development.

- Revisiting force structure decisions. Proposals included increasing overall military size and end strength; maintaining superiority in undersea and strike warfare, electronic warfare operations, and air warfare; focusing the Marine Corps and United States Special Operations Command on irregular warfare; and focusing the Army on decisive land battle rather than full-spectrum operations.

Interagency Reform

A number of observers point out that DOD is but one part of a broader set of U.S. national security institutions. In this view, other institutions (State and USAID, for example) are often better suited to take on security tasks that do not involve the application of military power. Better enabling the United States to grapple with emerging threats may therefore require revisiting interagency national security structures. As one observer noted, "the brokenness of the overall national security system will hamper the effectiveness of U.S. foreign and security policy no matter how well DOD transforms its internal operations or its performance at the operational level of war."101 Accordingly, recommendations included in this category were proposals to better synchronize DOD efforts with other U.S. government departments and agencies, and strengthen other, non-DOD national security institutions:

- Synchronizing DOD activities with those of other USG departments. Proposals included adjusting Combatant Command headquarters to accommodate increased collaboration with U.S. government agencies and international partners; merging the Department of State and Department of Defense at the regional level; renaming Combatant Commands to "Unified Commands" to signal a whole-of-government approach; expanding the number of State Department foreign policy advisors (or "Political Advisors") at Combatant Commands; better aligning how the Department of State and DOD divide up geographic regions of the world; and giving regional COCOMs a civilian deputy.

- Augmenting and strengthening interagency institutions. Proposals included creating interagency regional centers as regional headquarters for foreign and defense policy; increasing funding for the National Security Council; and designing a "Goldwater-Nichols" act for the interagency. Other observers recommended against such an interagency reform act.

While many of these recommendations are interrelated and could be mutually reinforcing if executed properly, others are in tension with each other. For example, some maintain that adopting proposals currently being tabled such as establishing a Joint General Staff, or placing the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the chain of command, would diminish the Secretary of Defense's control over the Department of Defense.102 Another example pertains to more effective interagency collaboration. Some believe that a "Goldwater-Nichols" for the broader, interagency national security establishment is needed in order to better prepare the Department to conduct complex operations.103 Others believe that top-down interagency organizational reform might be counterproductive.104

The Pentagon's View on Reform Proposals

Using the congressional interest as an impetus, in the fall of 2015 Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter initiated "a comprehensive review of Goldwater-Nichols legislation and related organizational issues in the DOD."105 To that end, a series of working groups was established in order to "assess key issue areas," and find "additional opportunities for efficiencies and other improvements in the Department's organization."106 The published results of their deliberations, including recommendations that are supported and not supported by the Department, are organized into the DOD management framework outlined above (the text below is taken directly from the DOD document, with only small alterations for clarification):107

Formulating Requirements

Actions recommended: