Introduction

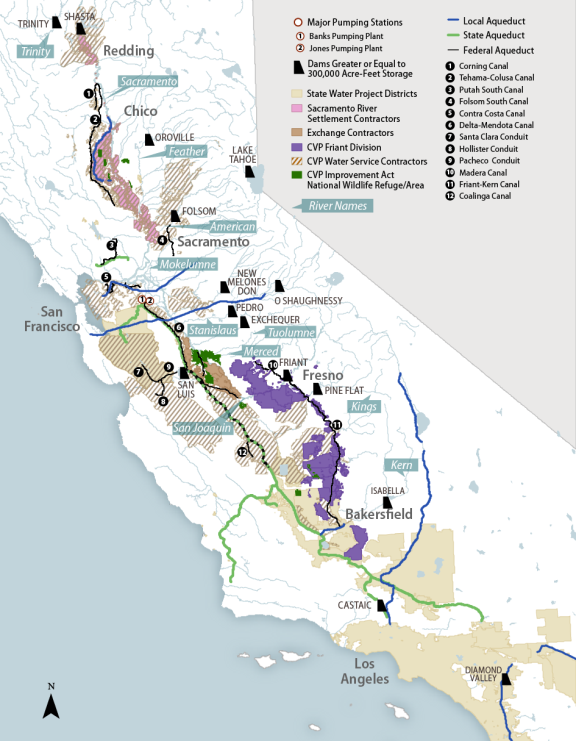

The Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), part of the Department of the Interior (DOI), operates the multipurpose federal Central Valley Project (CVP) in California, one of the world's largest water storage and conveyance systems. The CVP runs approximately 400 miles in California, from Redding to Bakersfield (Figure 1). It supplies water to hundreds of thousands of acres of irrigated agriculture throughout the state, including some of the most valuable cropland in the country. It also provides water to selected state and federal wildlife refuges, as well as to some municipal and industrial (M&I) water users. The CVP's operations are coordinated with the state's other largest water supply project, the state-operated State Water Project (SWP).

This report provides information on hydrologic conditions in California and their impact on state and federal water management, with a focus on deliveries related to the federal CVP. It also summarizes selected issues for Congress related to the CVP.

Recent Developments

The drought of 2012-2016, widely considered to be among California's most severe droughts in recent history, resulted in major reductions to CVP contractor allocations and economic and environmental impacts throughout the state.1 These impacts were of interest to Congress, which oversees federal operation of the CVP. Although the drought ended with the wet winter of 2017, many of the water supply controversies associated with the CVP predated those water shortages and remain unresolved. Absent major changes to existing hydrologic, legislative, and regulatory baselines, most agree that at least some water users are likely to face ongoing constraints to their water supplies. Due to the limited water supplies available, proposed changes to the current operations and allocation system are controversial.

As a result of the scarcity of water in the West and the importance of federal water infrastructure to the region, western water issues are regularly of interest to many lawmakers. Legislation enacted in the 114th Congress (Title II of the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation [WIIN] Act; P.L. 114-322) included several CVP-related sections.2 These provisions directed pumping to "maximize" water supplies for the CVP (including pumping or "exports" to CVP water users south of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers' confluence with the San Francisco Bay, known as the Bay-Delta or Delta) in accordance with applicable biological opinions (BiOps) for project operations.3 They also allowed for increased pumping during certain storm events generating high flows, authorized actions to facilitate water transfers, and established a new standard for measuring the effects of water operations on species. In addition to operational provisions, the WIIN Act authorized funding for construction of new federal and nonfederal water storage projects. CVP projects are among the most likely recipients of this funding.

Due to increased precipitation and disagreements with the state, among other factors, the WIIN Act's operational authorities generally did not yield significant new water exports south of the Delta in 2017-2019. However, Reclamation received funding for WIIN Act-authorized water storage project design and construction in FY2017-FY2020, and the majority of this funding has gone to CVP-related projects.

CVP and SWP water allocations for 2020 were once again reduced due to extremely limited precipitation in the winter months. Separate state and federal plans under the Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act, respectively, would alter water allocation and operational criteria in markedly different ways and have generated controversy. In mid-2018, the State of California proposed revisions to its Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan (developed pursuant to the Clean Water Act [CWA; 33 U.S.C. §§1251-138]). These changes would require that more flows from the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers reach the California Bay-Delta for water quality and fish and wildlife enhancement (and would thus further reduce water supplies for CVP and SWP users). Separately, in February 2020, the Trump Administration finalized an operational plan to increase water supplies for users and issued a new biological opinion under the Endangered Species Act (ESA; 87 Stat. 884, 16 U.S.C. §§1531-1544) that reflects these changes. Both plans are the subject of ongoing litigation.

Background

California's Central Valley encompasses almost 20,000 square miles in the center of the state (Figure 1). It is bound by the Cascade Range to the north, the Sierra Nevada to the east, the Tehachapi Mountains to the south, and the Coast Ranges and San Francisco Bay to the west. The northern third of the valley is drained by the Sacramento River, and the southern two-thirds of the valley are drained by the San Joaquin River. Historically, this area was home to significant fish and wildlife populations.

The CVP was originally conceived as a state project; the state studied the project as early as 1921, and the California state legislature formally authorized it for construction in 1933. After it became clear that the state was unable to finance the project, the federal government (through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, or USACE) assumed control of the CVP as a public works construction project under authority provided under the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1935.4 The Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration subsequently transferred the project to Reclamation.5 Construction on the first unit of the CVP (Contra Costa Canal) began in October 1937, with water first delivered in 1940. Additional CVP units were completed and came online over time, and some USACE-constructed units have also been incorporated into the project.6 The New Melones Unit was the last unit of the CVP to come online; it was completed in 1978 and began operations in 1979.

The CVP made significant changes to California's natural hydrology to develop water supplies for irrigated agriculture, municipalities, and hydropower, among other things. Most of the CVP's major units, however, predated major federal natural resources and environmental protection laws such as ESA and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA; 42 U.S.C. §§4321 et seq.), among others. Thus, much of the current debate surrounding the project revolves around how to address the project's changes to California's hydrologic system that were not major considerations when it was constructed.

Today, CVP water serves a variety of different purposes for both human uses and fish and wildlife needs. The CVP provides a major source of support for California agriculture, which is first in the nation in terms of farm receipts.7 CVP water supplies irrigate more than 3 million acres of land in central California and support 7 of California's top 10 agricultural counties. In addition, CVP M&I water provides supplies for approximately 2.5 million people per year. CVP operations are also critical for hydropower, recreation, and fish and wildlife protection. In addition to fisheries habitat, CVP flows support wetlands, which provide habitat for migrating birds.

Overview of the CVP and California Water Infrastructure

The CVP (Figure 1) is made up of 20 dams and reservoirs, 11 power plants, and 500 miles of canals, as well as numerous other conduits, tunnels, and storage and distribution facilities.8 In an average year, it delivers approximately 5 million acre-feet (AF) of water to farms (including some of the nation's most valuable farmland); 600,000 AF to M&I users; 410,000 AF to wildlife refuges; and 800,000 AF for other fish and wildlife needs, among other purposes. A separate major project owned and operated by the State of California, the State Water Project (SWP), draws water from many of the same sources as the CVP and coordinates its operations with the CVP under several agreements. In contrast to the CVP, the SWP delivers about 70% of its water to urban users (including water for approximately 25 million users in the San Francisco Bay, Central Valley, and Southern California); the remaining 30% is used for irrigation.

At their confluence, the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers flow into the San Francisco Bay (the Bay-Delta, or Delta). Operation of the CVP and SWP occurs through the storage, pumping, and conveyance of significant volumes of water from both river basins (as well as trans-basin diversions from the Trinity River Basin in Northern California) for delivery to users. Federal and state pumping facilities in the Delta near Tracy, CA, export water from Northern California to Central and Southern California and are a hub for CVP operations and related debates. In the context of these controversies, north of Delta (NOD) and south of Delta (SOD) are important categorical distinctions for water users.

CVP storage is spread throughout Northern and Central California. The largest CVP storage facility is Shasta Dam and Reservoir in Northern California (Figure 2), which has a capacity of 4.5 million AF. Other major storage facilities, from north to south, include Trinity Dam and Reservoir (2.4 million AF), Folsom Dam and Reservoir (977,000 AF), New Melones Dam and Reservoir (2.4 million AF), Friant Dam and Reservoir (520,000 AF), and San Luis Dam and Reservoir (1.8 million AF of storage, of which half is federal and half is nonfederal).

The CVP also includes numerous water conveyance facilities, the longest of which are the Delta-Mendota Canal (which runs for 117 miles from the federally operated Bill Jones pumping plant in the Bay-Delta to the San Joaquin River near Madera) and the Friant-Kern Canal (which runs 152 miles from Friant Dam to the Kern River near Bakersfield).

Non-CVP water storage and infrastructure is also spread throughout the Central Valley and in some cases is integrated with CVP operations. Major non-CVP storage infrastructure in the Central Valley includes multiple storage projects that are part of the SWP (the largest of which is Oroville Dam and Reservoir in Northern California), as well as private storage facilities (e.g., Don Pedro and Exchequer Dams and Reservoirs) and local government-owned dams and infrastructure (e.g., O'Shaughnessy Dam and Hetch-Hetchy Reservoir and Aqueduct, which are owned by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission).

In addition to its importance for agricultural water supplies, California's Central Valley also provides valuable wetland habitat for migratory birds and other species. As such, it is home to multiple state, federal, and private wildlife refuges north and south of the Delta. Nineteen of these refuges (including 12 refuges within the National Wildlife Refuge system, 6 State Wildlife Areas/Units, and 1 privately managed complex) provide managed wetland habitat that receives water from the CVP and other sources. Five of these units are located in the Sacramento River Basin (i.e., North of the Delta), 12 are in the San Joaquin River Basin, and the remaining 2 are in the Tulare Lake Basin.9

|

|

Source: Bureau of Reclamation. |

Central Valley Project Water Contractors and Allocations

In normal years, snowpack accounts for approximately 30% of California's water supplies and is an important factor in determining CVP and SWP allocations. Water from snowpack typically melts in the spring and early summer, and it is stored and made available to meet water needs throughout the state in the summer and fall. By late winter, the state's water supply outlook is typically sufficient for Reclamation to issue the amount of water it expects to deliver to its contractors.10 At that time, Reclamation announces estimated deliveries for its 250 CVP water contractors in the upcoming water year.11

More than 9.5 million AF of water per year is potentially available from the CVP for delivery based on contracts between Reclamation and CVP contractors.12 However, most CVP water contracts provide exceptions for Reclamation to reduce water deliveries due to hydrologic conditions and other conditions outside Reclamation's control.13 As a result of these stipulations, Reclamation regularly makes cutbacks to actual CVP water deliveries to contractors due to drought and other factors.

Even under normal hydrological circumstances, the CVP often delivers much less than the maximum contracted amount of water; since the early 1980s, an average of about 7 million AF of water has been made available to CVP contractors annually (including 5 million AF to agricultural contractors). However, during drought years deliveries may be significantly less. In the extremely dry water years of 2012-2015, CVP annual deliveries averaged approximately 3.45 million AF.14

CVP contractors receive varying levels of priority for water deliveries based on their water rights and other related factors, and some of the largest and most prominent water contractors have a relatively low allocation priority. Major groups of CVP contractors include water rights contractors (i.e., senior water rights holders such as the Sacramento River Settlement and San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors, see box below), North and South of Delta water service contractors, and Central Valley refuge water contractors. The relative locations for these groups are shown in Figure 1.

|

Water Rights Contractors California's system of state water rights has a profound effect on who gets how much water and when, particularly during times of drought or other restrictions on water supply. Because the waters of California are considered to be "the property of the people of the State," anyone wishing to use those waters must acquire a right to do so. California follows a dual system of water rights, recognizing both the riparian and prior appropriation doctrines. Under the riparian doctrine, a person who owns land that borders a watercourse has the right to make reasonable use of the water on that land (riparian rights). Riparian rights are reduced proportionally during times of shortage. Under the prior appropriation doctrine, a person who diverts water from a watercourse (regardless of his location relative thereto) and makes reasonable and beneficial use of the water acquires a right to that use of the water (appropriated rights). Appropriated rights are filled in order of seniority during times of shortage. Before exercising the right to use the water, appropriative users must obtain permission from the state through a permit system run by the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). Both the Central Valley Project (CVP) and the State Water Project (SWP) acquired rights for water use from the State of California, receiving several permits for water diversions at various points between 1927 and 1967. Since the Bureau of Reclamation found it necessary to take the water rights of other users to construct the CVP, it entered into settlement or exchange contracts with water users who had rights predating the CVP (and thus were senior users in time and right). Many of these special contracts were entered into in areas where water users were diverting water directly from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. Sacramento River Settlement Contractors include the contractors (both individuals and districts) that diverted natural flows from the Sacramento River prior to the CVP's construction and executed a settlement agreement with Reclamation that provided for negotiated allocation of water rights. San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors are the irrigation districts that agreed to "exchange" exercising their water rights to divert water on the San Joaquin and Kings Rivers for guaranteed water deliveries from the CVP (typically in the form of deliveries from the Delta-Mendota Canal and waters north of the Delta). In contrast to water service contractors, water rights contractors receive 100% of their contracted amounts in most water-year types. During water shortages, their annual maximum entitlement may be reduced but not by more than 25%. |

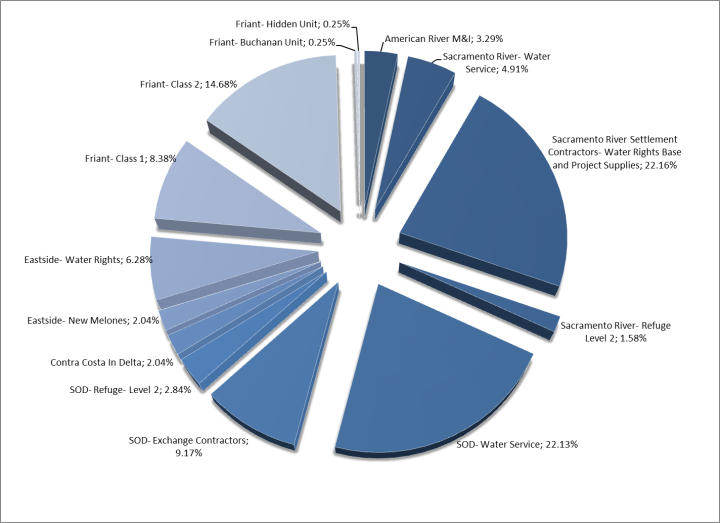

The largest contract holders of CVP water by percentage of total contracted amounts are Sacramento River Settlement Contractors, located on the Sacramento River. The second-largest group are SOD water service contractors (including Westlands Water District, the CVP's largest contractor), located in the area south of the Delta. Other major contractors include San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors, located west of the San Joaquin River and Friant Division contractors, located on the east side of the San Joaquin Valley. Central Valley refuges and several smaller contractor groups (e.g., Eastside Contracts, In-Delta-Contra Costa Contracts, and SOD Settlement Contracts) also factor into CVP water allocation discussions.15 Figure 3 depicts an approximate division of maximum available CVP water deliveries pursuant to contracts with Reclamation. The largest contractor groups and their relative delivery priority are discussed in more detail in the Appendix to this report.

|

Figure 3. Central Valley Project: Maximum Contract Amounts (relative share of total maximum contracted CVP supplies) |

|

|

Source: CRS, using 2016 Bureau of Reclamation contractor data. Notes: SOD = South-of-Delta; M&I = municipal and industrial water service contractors. Sacramento River Settlement Contractors includes both "base" water rights supplies (18.6%) and additional CVP "project" supplies (3.5%). For SOD Refuges, chart does not reflect "Level 4" supplies (for more information on Level 4 supplies, see below section, "Central Valley Wildlife Refuges"). |

CVP Allocations

Reclamation provided its allocations for the 2020 water year in February 2020 (Table 1) and subsequently revised these allocations on multiple occasions in April and May 2020. Compared with the last two years, water allocation levels were decreased significantly due to diminished precipitation in 2020. Reclamation stated that the allocations took into account newly finalized biological opinions for CVP operations (see below section, "Endangered Species Act") but that dry conditions left "little to no room to realize operational improvements under the biological opinions."16

The most senior water rights contractors and some refuges were initially allocated 100% of their maximum contract allocations in 2020, but this estimate was subsequently revised downward to 75% in April due to a determination that 2020 was a "Shasta Critical Year" (i.e., forecasted inflows to Shasta Lake of 3.2 million acre-feet or less). SOD agricultural water service contractors, who have been critical of operations prior to the recent changes, were allocated 20% of their contracted supplies in 2020. They have received their full contract allocations only four times since 1990: 1995, 1998, 2006, and 2017.17 Friant Class 1 contractors received multiple revisions upward for their allocation, from 20% to 55% to 60%, due to late season precipitation in the Central Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Table 1. CVP Water Allocations by Water Year, 2011-2020

(percentage of maximum contract allocation made available)

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

North-of-Delta Users |

||||||||||

|

Agricultural |

100% |

100% |

75% |

0% |

0% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

50% |

|

M&I |

100% |

100% |

100% |

50% |

25% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

|

Settlement Contractors |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

75% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

|

Refuges (Level 2) |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

75% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

|

American River M&I |

100% |

100% |

75% |

50% |

25% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

|

In Delta- Contra Costa |

100% |

100% |

75% |

50% |

25% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

|

South-of-Delta Users |

||||||||||

|

Agricultural |

80% |

40% |

20% |

0% |

0% |

5% |

100% |

50% |

75% |

20% |

|

M&I |

100% |

75% |

70% |

50% |

25% |

55% |

100% |

70% |

100% |

70% |

|

Exchange Contractors |

100% |

100% |

100% |

65% |

75% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

75% |

|

Refuges (Level 2) |

100% |

100% |

100% |

65% |

75% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

Eastside Division |

100% |

100% |

100% |

55% |

0% |

0% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

Friant Class I |

100% |

50% |

62% |

0% |

0% |

65% |

100% |

88% |

100% |

60% |

|

Friant Class 2 |

20% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

13% |

100% |

9% |

0% |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, CVP Historical Water Supply Allocations and 2019 Allocations, available at https://www.usbr.gov/mp/cvo/vungvari/water_allocations_historical.pdf.

Notes: CVP = Central Valley Project. M&I = municipal and industrial water contractors. "Settlement" refers to contractors on the Sacramento River, and "Exchange" refers to contractors on the San Joaquin River; both groups have contracts and minimum delivery levels recognizing water rights predating those acquired by Reclamation for the CVP. Contra Costa, Eastside Division, and Friant Class 1 and Class 2 represent individual or groups of water contractors.

a. "Uncontrolled" Class 2 releases for Friant Contractors were available through June 30, 2019.

State Water Project Allocations

The other major water project serving California, the SWP, is operated by California's Department of Water Resources (DWR). The SWP primarily provides water to M&I users and some agricultural users, and it integrates its operations with the CVP. Similar to the CVP, the SWP has considerably more contracted supplies than it typically makes available in its deliveries. SWP contracted entitlements are 4.17 million AF, but average annual deliveries are typically considerably less than that amount.

SWP water deliveries were at their lowest point in 2014 and 2015, and they were significantly higher in the wet year of 2017. SWP water supply allocations for water years 2012-2020 are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. California State Water Project (SWP) Allocations by Water Year, 2012-2020

(percentage of maximum contract allocation)

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 (est.) |

|

|

State Water Project |

65% |

35% |

5% |

20% |

60% |

85% |

35% |

75% |

15% |

Source: California Department of Water Resources, "Notices to State Water Project Contractors," at https://water.ca.gov/Programs/State-Water-Project/Management/SWP-Water-Contractors.

Combined CVP/SWP Operations

The CVP and SWP are operated in conjunction under the 1986 Coordinated Operations Agreement (COA), which was executed pursuant to P.L. 99-546.18 COA defines the rights and responsibilities of the CVP and SWP with respect to in-basin water needs and provides a mechanism to account for those rights and responsibilities. Several major changes to California water supply allocations that occurred since 1986 (e.g., water delivery reductions pursuant to the Central Valley Project Improvement Act, the Endangered Species Act requirements, and new Delta Water Quality Standards, among other things) caused some to argue for renegotiation of the agreement's terms.19 Dating to 2015, Reclamation and DWR conducted a mutual review of COA but were unable to agree on revisions. On August 17, 2018, Reclamation provided a Notice of Negotiations to DWR.20 Following negotiations in the fall of 2018, Reclamation and DWR agreed to an addendum to COA in December 2018.21 Whereas the original 1986 agreement included a fixed ratio of 75% CVP/25% SWP for the sharing of regulatory requirements associated with storage withdrawals for Sacramento Valley in-basin uses (e.g., curtailments for water quality and species uses), the revised addendum adjusted the ratio of sharing percentages based on water year types (Table 3).

Table 3. COA Regulatory Requirements for CVP/SWP In-basin Storage Withdrawals

(requirements pursuant to 1986 and 2018 agreements)

|

Water Year Type |

1986 COA |

COA with 2018 Addendum |

|

All |

75% CVP, 25% SWP |

NA |

|

Wet & Above Normal |

NA |

80% CVP, 20% SWP |

|

Below Normal |

NA |

75% CVP, 25% SWP |

|

Dry |

NA |

65% CVP, 35% SWP |

|

Critically Dry |

NA |

60% CVP, 40% SWP |

Source: Addendum to the Agreement Between the United States of America and the Department of Water Resources of the State of California for Coordinated Operation of the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project, December 12, 2018.

The 2018 addendum also adjusted the sharing of export capacity under constrained conditions. Whereas under the 1986 COA, export capacity was shared evenly between the CVP and the SWP, under the revised COA the split is to be 60% CVP/40% SWP during excess conditions, and 65% CVP/35% SWP during balanced conditions.22 Finally, the state also agreed in the 2018 revisions to transport up to 195,000 AF of CVP water through the SWP's California Aqueduct during certain conditions. Recent disagreements related to CVP and SWP operational changes by the federal and state governments, in particular those under the ESA, have called into question the future of coordinated operations under COA. These developments are discussed further in the below section, "Endangered Species Act."

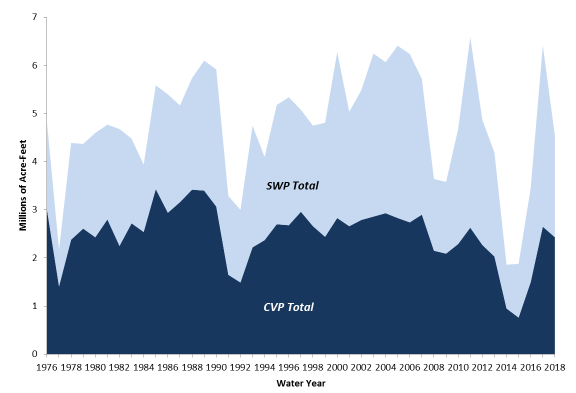

CVP/SWP Exports

Combined CVP and SWP exports (i.e., water transferred from north to south of the Delta) is of interest to many observers because it reflects trends over time in the transfer of water from north to south (i.e., exports) by the two projects, in particular through pumping. Exports of the CVP and SWP, as well as total combined exports since 1978, have varied over time (Figure 4). Most recently, combined exports dropped significantly during the 2012-2016 drought but have rebounded since 2016. Prior to the drought, overall export levels had increased over time, having averaged more from 2001 to 2011 than over any previous 10-year period. The 6.42 million AF of combined exports in 2017 was the second most on record, behind 6.59 million AF in 2011.

Over time, CVP exports have decreased on average, whereas SWP exports have increased. Additionally, exports for agricultural purposes have declined as a subset of total exports, in part due to those exports being made available for other purposes (e.g., fish and wildlife).

Constraints on CVP Deliveries

Concerns over CVP water supply deliveries persist in part because even in years with high levels of precipitation and runoff, some contractors (in particular SOD water service contractors) have regularly received allocations of less than 100% of their contract supplies. Allocations for some users have declined over time; additional environmental requirements in recent decades have reduced water deliveries for human uses. Coupled with reduced water supplies available in drought years, some have increasingly focused on what can be done to increase water supplies for users. At the same time, others that depend on or advocate for the health of the San Francisco Bay and its tributaries, including fishing and environmental groups and water users throughout Northern California, have argued for maintaining or increasing existing environmental protections (the latter of which would likely further constrain CVP exports).

Hydrology and state water rights are the two primary drivers of CVP allocations. However, at least three other regulatory factors affect the timing and amount of water available for delivery to CVP contractors and are regularly the subject of controversy:

- State water quality requirements pursuant to state and the federal water quality laws (including the Clean Water Act [CWA, 33 U.S.C. §§1251-138]);

- Regulations and court orders pertaining to implementation of the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA, 87 Stat. 884. 16 U.S.C. §§1531-1544);23 and

- Implementation of the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA; P.L. 102-575).24

Each of these factors is discussed in more detail below.

Water Quality Requirements: Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan

California sets water quality standards and issues permits for the discharge of pollutants in compliance with the federal CWA, enacted in 1972.25 Through the Porter-Cologne Act (a state law), California implements federal CWA requirements and authorizes the State Water Resources Control Board (State Water Board) to adopt water quality control plans, or basin plans.26 The CVP and the SWP affect water quality in the Bay-Delta depending on how much freshwater the projects release into the area as "unimpaired flows" (thereby affecting area salinity levels).

The first Water Quality Control Plan for the Bay-Delta (Bay-Delta Plan) was issued by the State Water Board in 1978. Since then, there have been three substantive updates to the plan—in 1991, 1995, and 2006. The plans have generally required the SWP and CVP to meet certain water quality and flow objectives in the Delta to maintain desired salinity levels for in-Delta diversions (e.g., water quality levels for in-Delta water supplies) and fish and wildlife, among other things. These objectives often affect the amount and timing of water available to be pumped, or exported, from the Delta and thus at times result in reduced Delta exports to CVP and SWP water users south of the Delta.27 The Bay-Delta Plan is currently implemented through the State Water Board's Decision 1641 (or D-1641), which was issued in 1999 and placed responsibility for plan implementation on the state's largest two water rights holders, Reclamation and the California DWR.28

Pumping restrictions to meet state-set water quality levels—particularly increases in salinity levels—can sometimes be significant. However, the relative magnitude of these effects varies depending on hydrology. For instance, Reclamation estimated that in 2014, water quality restrictions accounted for 176,300 AF of the reduction in pumping from the long-term average for CVP exports.29 In 2016, Reclamation estimated that D-1641 requirements accounted for 114,500 AF in reductions from the long-term export average.

Bay-Delta Plan Update

In mid-2018, the State Water Board released the final draft of the update to the 2006 Bay Delta Plan (i.e., the Bay-Delta Plan Update) for the Lower San Joaquin River and Southern Delta. It also announced further progress on related efforts under the update for flow requirements on the Sacramento River and its tributaries.30 The Bay-Delta Plan Update requires additional flows to the ocean (generally referred to in these documents as "unimpaired flows") from the San Joaquin River and its tributaries (i.e., the Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced Rivers). Under the proposal, the unimpaired flow requirement for the San Joaquin River would be 40% (within a range of 30%-50%); average unimpaired flows currently range from 21% to 40%.31 The state estimates that the updated version of the plan would reduce water available for human use from the San Joaquin River and its tributaries by between 7% and 23%, on average (depending on the water year type), but it could reduce these water supplies by as much as 38% during critically dry years.32

A more detailed plan for the Sacramento River and its tributaries is also expected in the future. A preliminary framework released by the state in July 2018 proposed a potential requirement of 55% unimpaired flows from the Sacramento River (within a range of 45% to 65%).33 According to the State Water Board, if the plan updates for the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers are finalized and water users do not enter into voluntary agreements to implement them, the board could take actions to require their implementation, such as promulgation of regulations and conditioning of water rights.34

Reclamation and its contractors would likely play key roles in implementing any update to the Bay-Delta Plan, as they do in implementing the current plan under D-1641. Pursuant to Section 8 of the Reclamation Act of 1902,35 Reclamation generally defers to state water law in carrying out its authorities, but the proposed Bay Delta Plan Update has generated controversy. In a July 2018 letter to the State Water Board, the Commissioner of Reclamation opposed the proposed standards for the San Joaquin River, arguing that meeting them would necessitate decreased water in storage at New Melones Reservoir of approximately 315,000 AF per year (a higher amount than estimated by the State Water Board). Reclamation argued that such a change would be contrary to the CVP prioritization scheme as established by Congress.36

On December 12, 2018, the State Water Board approved the Bay Delta Plan Update in Resolution 1018-0059.37 According to the state, the plan establishes a "starting point" for increased river flows but also makes allowances for reduced river flows on tributaries where stakeholders have reached voluntary agreements to pursue both flow and "non-flow" measures.38 The conditions in the Bay-Delta Plan Update would be implemented through water rights conditions imposed by the State Water Board; these conditions are to be implemented no later than 2022.

On March 28, 2019, the Department of Justice and DOI filed civil actions in federal and state court against the State Water Board for failing to comply with the California Environmental Quality Act.39

Endangered Species Act

Several species that have been listed under the federal ESA are affected by the operations of the CVP and the SWP.40 One species, the Delta smelt, is a small pelagic fish that is susceptible to entrainment in CVP and SWP pumps in the Delta; it was listed as threatened under ESA in 1993. Surveys of Delta smelt in 2017 found two adult smelt, the lowest catch in the history of the survey.41 These results were despite the relatively wet winter of 2017, which is a concern for many stakeholders because low population sizes of Delta smelt could result in greater restrictions on water flowing to users. It also raises larger concerns among stakeholders about the overall health and resilience of the Bay-Delta ecosystem. In addition to Delta smelt, multiple anadromous salmonid species were listed under ESA dating to 1991, including the endangered Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon, the threatened Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon, the threatened Central Valley steelhead, threatened Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast coho salmon, and the threatened Central California Coast steelhead.42

Federal agencies consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) in DOI or the Department of Commerce's (DOC's) National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to determine if a federal project or action might jeopardize the continued existence of a species listed under ESA or adversely modify its habitat. If an effect is possible, formal consultation is started and usually concludes with the appropriate agency issuing a biological opinion (BiOp) on the potential harm the project poses and, if necessary, issuing reasonable and prudent measures to reduce the harm.

CVP and SWP BiOps have been challenged and revised over time. Until 2004, a 1993 winter-run Chinook salmon BiOp and a 1995 Delta smelt BiOp (as amended) governed Delta exports for federal ESA purposes. In 2004, a proposed change in coordinated operation of the SWP and CVP (including increased Delta exports), known as OCAP (Operations Criteria and Plan) resulted in the development of new BiOps. Environmental groups challenged the agencies' 2004 BiOps; this challenge resulted in the development of new BiOps by the FWS and NMFS in 2008 and 2009, respectively.43 These BiOps placed additional restrictions on the amount of water exported via SWP and CVP Delta pumps and other limitations on pumping and release of stored water.44 Since then, the CVP and SWP have been operated in accordance with these BiOps, both of which concluded that the coordinated long-term operation of the CVP and SWP, as proposed in Reclamation's 2008 Biological Assessment, was likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed species and destroy or adversely modify designated critical habitat. Both BiOps included reasonable and prudent alternatives (RPAs) designed to allow the CVP and SWP to continue operating without causing jeopardy to listed species or destruction or adverse modification to designated critical habitat. Reclamation accepted the BiOps and then began project operations consistent with the FWS and NMFS RPAs.

In August 2016, Reclamation and DWR requested reinitiation of consultation on long-term, system-wide operations of the CVP and the SWP based on new information related to multiple years of drought, species decline, and related data.45 In December 2017, the Trump Administration gave formal notice of its intent to prepare an environmental impact statement analyzing potential long-term modifications to the coordinated operations of the CVP and the SWP.46

On October 19, 2018, President Trump issued a memorandum on western water supplies that, among other things, directed DOI to issue its final biological assessment (BA) proposing changes for the operation of the CVP and SWP by January 31, 2019; it also directed that FWS and NOAA issue their final BiOps in response to the BA within 135 days of that time.47 Reclamation completed the BA and sent it to FWS and NMFS for review on January 31, 2019.48 The BA discussed the operational changes proposed by Reclamation and mitigation factors to address listed species. According to Reclamation, the changes in the BA reflected a shift to pumping based on real-time monitoring rather than calendar-based targets, as well as updated science and monitoring information and a revised plan for cold water management and releases at Shasta Dam. The BA also stated that nonoperational activities would be implemented to augment and bolster listed fish populations. These activities include habitat restoration and introduction of hatchery-bred Delta smelt, among other things.

FWS and NOAA simultaneously issued BiOps for Reclamation's proposed CVP operations on October 21, 2019.49 In contrast to the 2008 and 2009 BiOps, the agencies concluded that Reclamation's proposed operations would not jeopardize threatened or endangered species nor adversely modify their designated critical habitat. In coming to these conclusions, FWS and NMFS reported that they worked with Reclamation to modify the proposed action to reduce potential threats to the species and their critical habitat and to increase mitigation measures such as habitat restoration to support listed species. Some of the changes in the final action included adding performance metrics for real-time monitoring, implementing cold-water management in Lake Shasta, increasing habitat restoration, and introducing a process for independent scientific review, among other things.50

After issuing the BiOps, Reclamation completed its review of environmental impacts of the proposed action under NEPA. Reclamation concluded its NEPA review by issuing an environmental impact statement (EIS) on December 19, 2019, regarding the anticipated environmental effects of the action.51 The EIS evaluated four alternatives and selected a preferred alternative, Alternative 1, which included a combination of flow-related actions, habitat restoration, and measures to increase water deliveries and protect fish and wildlife.52 Having completed ESA and NEPA review, Reclamation's proposed changes were finalized in a Record of Decision on February 20, 2020.53

For the state and federal projects to be operated in a coordinated manner and to avoid management confusion, the state also must approve SWP operations pursuant to a permit under the California Endangered Species Act.54 Historically, DWR received coverage for the SWP's state law requirements through state "consistency determinations" that federal protections complied with the California Endangered Species Act. However, in April 2019, the state announced that it would develop a permit for the SWP that does not rely on the federal process and has since taken steps to improve protections for fish and wildlife. In November 2019, the state announced it had determined that Reclamation's proposed changes did not adequately protect species and state interests,55 and it finalized its incidental take permit for the SWP on March 31, 2020.56 The permit calls for additional protective actions beyond those provided for in Reclamation's operational plans.

On February 20, 2020, California sued the federal government for violations of the ESA, NEPA, and Administrative Procedure Act (APA).57 Among other relief sought, California asked that the court enjoin Reclamation from implementing any actions that rely on the BiOps.58 Separately, a group of nongovernmental organizations also sued the federal government for alleged violations stemming from the BiOps and Record of Decision and similarly asked that the court prohibit implementation of the new operations.59

Both the nongovernmental organizations and California have also requested that the court prohibit Reclamation from implementing the operational changes while the litigation is pending.60 While the nongovernmental organizations requested an injunction until the court resolves the merits of the case,61 California's motion focused specifically on the harm that might be caused through May 31, 2020, from operational changes connected to an RPA that NMFS included in its 2009 BiOp62 but omitted in its 2019 BiOp.63 On May 11, 2020, the court granted the motions in part based on California's narrower request, finding that NMFS's failure to carry forward the identified RPA from the 2009 BiOp was likely to cause irreparable harm to the California Central Valley Steelhead.64 The court's order required Reclamation to implement the RPA from the 2009 BiOp instead of any conflicting operational changes through May 31, 2020.65 The court stated that it would address other aspects of the nongovernmental organizations' motion and any additional injunctive relief in a separate order.66

|

How Much Water Do ESA Restrictions Account For? The exact magnitude of reductions in pumping due to ESA restrictions compared to the aforementioned water quality restrictions has varied considerably over time. In absolute terms, ESA-driven reductions are typically greater in wet years than in dry years, but the proportion of ESA reductions relative to deliveries depends on numerous factors. For instance, Reclamation estimated that ESA restrictions accounted for a reduction in deliveries of 62,000 AF from the long-term average for CVP deliveries in 2014 and 144,800 AF of CVP delivery reductions in 2015 (both years were extremely dry). In 2016 (a wet year), ESA reductions accounted for a much larger amount (528,000 AF, when more water was delivered. During the 2012-2016 drought, implementation of the RPAs (which generally limit pumping under specific circumstances and call for water releases from key reservoirs to support listed species) was modified due to temporary urgency change orders (TUCs). These TUCs, issued by the California State Water Resources Control Board in 2014 and again in 2015, were deemed consistent with the existing BiOps by NMFS and FWS. Such changes allowed more water to be pumped during certain periods based on real-time monitoring of species and water conditions. DWR estimates that approximately 400,000 AF of water was made available in 2014 for export due to these orders. Sources: Reclamation, "Water Year 2016 CVIPA §3406(b)(2) Accounting," at https://www.usbr.gov/mp/cvo/vungvari/FINAL_wy16_b2_800TAF_table_20170930.pdf, and California Environmental Protection Agency and State Water Resources Control Board, "March 5, 2015 Order Modifying an Order That Approved in Part and Denied in Part a Petition for Temporary Urgency Changes to Permit Terms and Conditions Requiring Compliance with Delta Water Quality Objectives in Response to Drought Conditions," p. 4, at http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/waterrights/water_issues/programs/drought/docs/tucp/tucp_order030515.pdf. |

Central Valley Project Improvement Act

In an effort to mitigate many of the environmental effects of the CVP, Congress in 1992 passed the CVPIA as Title 34 of P.L. 102-575. The act made major changes to the management of the CVP. Among other things, it formally established fish and wildlife purposes as an official project purpose of the CVP and called for a number of actions to protect, restore, and enhance these resources. Overall, the CVPIA's provisions resulted in a combination of decreased water availability and increased costs for agricultural and M&I contractors, along with new water and funding sources to restore fish and wildlife. Thus, the law remains a source of tension, and some would prefer to see it repealed in part or in full.

Some of the CVPIA's most prominent changes to the CVP included directives to

- double certain anadromous fish populations by 2002 (which did occur);67

- allocate 800,000 AF of "(b)(2)" CVP yield (600,000 AF in drought years) to fish and wildlife purposes;68

- provide water supplies (in the form of "Level 2" and "Level 4" supplies) for 19 designated Central Valley wildlife refuges;69 and

- establish a fund, the Central Valley Project Restoration Fund (CVPRF), to be financed by water and power users for habitat restoration and land and water acquisitions.

Pursuant to court rulings since enactment of the legislation, CVPIA (b)(2) allocations may be used to meet other state and federal requirements that reduce exports or require an increase from baseline reservoir releases. Thus, in a given year, the aforementioned export reductions due to state water quality and federal ESA restrictions are counted and reported on annually as (b)(2) water, and in some cases overlap with other stated purposes of CVPIA (e.g., anadromous fish restoration). The exact makeup of (b)(2) water in a given year typically varies. For example, in 2014 (a critically dry year), out of a total of 402,000 AF of (b)(2) water, 176,300 AF (44%) was attributed to export reductions for Bay-Delta Plan water quality requirements.70 Remaining (b)(2) water was comprised of a combination of reservoir releases classified as CVPIA anadromous fish restoration and NMFS BiOp compliance purposes (163,500 AF) and export reductions under the 2009 salmonid BiOp (62,200 AF).71 In 2016 (a wet year), 793,000 AF of (b)(2) water included 528,000 AF (66%) of export pumping reductions under FWS and NMFS BiOps and 114,500 AF (14%) for Bay-Delta Plan requirements. The remaining water was accounted for as reservoir releases for the anadromous fish restoration programs, the NMFS BiOp, and the Bay-Delta Plan.72

Ecosystem Restoration Efforts

Development of the CVP made significant changes to California's natural hydrology. In addition to the aforementioned CVPIA efforts to address some of these impacts, three ongoing, congressionally authorized restoration initiatives also factor into federal activities associated with the CVP:

- The Trinity River Restoration Program (TRRP), administered by Reclamation, attempts to mitigate impacts and restore fisheries impacted by construction of the Trinity River Division of the CVP.

- The San Joaquin River Restoration Program (SJRRP) is an ongoing effort to implement a congressionally enacted settlement to restore fisheries in the San Joaquin River.

- The California Bay-Delta Restoration Program aims to restore and protect areas within the Bay-Delta that are affected by the CVP and other activities.

In addition to their habitat restoration activities, both the TRRP and the SJRRP involve the maintenance of instream flow levels that use water that was at one time diverted for other uses. Each effort is discussed briefly below.

Trinity River Restoration Program

TRRP—administered by DOI—aims to mitigate impacts of the Trinity Division of the CVP and restore fisheries to their levels prior to the Bureau of Reclamation's construction of this division in 1955. The Trinity Division primarily consists of two dams (Trinity and Lewiston Dams), related power facilities, and a series of tunnels (including the 10.7-mile tunnel Clear Creek Tunnel) that divert water from the Trinity River Basin to the Sacramento River Basin and Whiskeytown Reservoir. Diversion of Trinity River water (which originally required that a minimum of 120,000 AF be reserved for Trinity River flows) resulted in the near drying of the Trinity River in some years, thereby damaging spawning habitat and severely depleting salmon stocks.

Efforts to mitigate the effects of the Trinity Division date back to the early 1980s, when DOI initiated efforts to study the issue and increase Trinity River flows for fisheries. Congress authorized legislation in 1984 (P.L. 98-541) and in 1992 (P.L. 102-575) providing for restoration activities and construction of a fish hatchery, and directed that 340,000 AF per year be reserved for Trinity River flows (a significant increase from the original amount). Congress also mandated completion of a flow evaluation study, which was formalized in a 2000 record of decision (ROD) that called for additional water for instream flows,73 river channel restoration, and watershed rehabilitation.74

The 2000 ROD forms the basis for TRRP. The flow releases outlined in that document have in some years been supplemented to protect fish health in the river, and these increases have been controversial among some water users. From FY2013 to FY2018, TRRP was funded at approximately $12 million per year in discretionary appropriations from Reclamation's Fish and Wildlife Management and Development activity.

San Joaquin River Restoration Program

Historically, the San Joaquin River supported large Chinook salmon populations. After the Bureau of Reclamation completed Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River in the late 1940s, much of the river's water was diverted for agricultural uses and approximately 60 miles of the river became dry in most years. These conditions made it impossible to support Chinook salmon populations upstream of the Merced River confluence.

In 1988, a coalition of environmental, conservation, and fishing groups advocating for river restoration to support Chinook salmon recovery sued the Bureau of Reclamation. A U.S. District Court judge eventually ruled that operation of Friant Dam was violating state law because of its destruction of downstream fisheries.75 Faced with mounting legal fees, considerable uncertainty, and the possibility of dramatic cuts to water diversions, the parties agreed to negotiate a settlement instead of proceeding to trial on a remedy regarding the court's ruling. This settlement was agreed to in 2006 and implementing legislation was enacted by Congress in 2010 (Title X of P.L. 111-11).

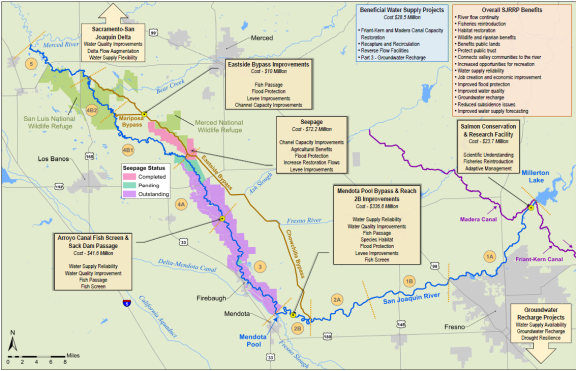

The settlement agreement and its implementing legislation form the basis for the SJRRP, which requires new releases of CVP water from Friant Dam to restore fisheries (including salmon fisheries) in the San Joaquin River below Friant Dam (which forms Millerton Lake) to the confluence with the Merced River (i.e., 60 miles). The SJRRP also requires efforts to mitigate water supply delivery losses due to these releases, among other things. In combination with the new releases, the settlement's goals are to be achieved through a combination of channel and structural modifications along the San Joaquin River and the reintroduction of Chinook salmon (Figure 5). These activities are funded in part by federal discretionary appropriations and in part by repayment and surcharges paid by CVP Friant water users that are redirected toward the SJRRP in P.L. 111-11.

|

Figure 5. San Joaquin River Restoration Program: Costs, Benefits, and Project Status (program details as of May 2018) |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Reclamation, San Joaquin River Restoration Program, May 2018, at http://www.restoresjr.net/?wpfb_dl=2131. |

Because increased water flows for restoring fisheries (known as restoration flows) would reduce CVP diversions of water for off-stream purposes, such as irrigation, hydropower, and M&I uses, the settlement and its implementation have been controversial. The quantity of water used for restoration flows and the quantity by which water deliveries would be reduced are related, but the relationship is not necessarily one-for-one, due to flood flows in some years and other mitigating factors. Under the settlement agreement, no water would be released for restoration purposes in the driest of years; thus, the agreement would not reduce deliveries to Friant contractors in those years. Additionally, in some years, the restoration flows released in late winter and early spring may free up space for additional runoff storage in Millerton Lake, potentially minimizing reductions in deliveries later in the year—assuming Millerton Lake storage is replenished. Consequently, how deliveries to Friant water contractors may be reduced in any given year is likely to depend on many factors. Regardless of the specifics of how much water may be released for fisheries restoration vis-à-vis diverted for off-stream purposes, the SJRRP will impact existing surface and groundwater supplies in and around the Friant Division service area and affect local economies. SJRRP construction activities are in the early stages, but planning efforts have targeted a completion date of 2024 for the first stage of construction efforts.76

CALFED Bay-Delta Restoration Program

The Bay-Delta Restoration Program is a cooperative effort among the federal government, the State of California, local governments, and water users to proactively address the water management and aquatic ecosystem needs of California's Central Valley. The CALFED Bay-Delta Restoration Act (P.L. 108-361), enacted in 2004, provided new and expanded federal authorities for six agencies related to the 2000 ROD for the CALFED Bay-Delta Program's Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement.77 These authorities were extended through FY2019 under the WIIN Act. The interim action plan for CALFED has four objectives: a renewed federal-state partnership, smarter water supply and use, habitat restoration, and drought and floodplain management.78

From FY2013 to FY2018, Reclamation funded its Bay-Delta restoration activities at approximately $37 million per year; the majority of this funding has gone for projects to address the degraded Bay-Delta ecosystem and includes federal activities under California WaterFix (see below section, "California WaterFix").79 Other agencies receiving funding to carry out authorities under CALFED include DOI's U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Geological Survey; the Department of Agriculture's Natural Resources Conservation Service; the Department of Defense's Army Corps of Engineers; the Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; and the Environmental Protection Agency. Similar to Reclamation, these agencies report on CALFED expenditures that involve a combination of activities under "base" authorities and new authorities that were provided under the CALFED authorizing legislation. The annual CALFED crosscut budget records the funding for CALFED across all federal agencies. The budget is generally included in the Administration's budget request and contains CALFED programs, their authority, and requested funding. For FY2019, the Administration requested $474 million for CALFED activities. This figure is an increase from the FY2018 enacted level of $415 million.

New Storage and Conveyance

Reductions in available water deliveries due to hydrological and regulatory factors have caused some stakeholders, legislators, and state and federal government officials to look at other methods of augmenting water supplies. In particular, proposals to build new or augmented CVP and/or SWP water storage projects have been of interest to some policymakers. Additionally, the State of California is pursuing a major water conveyance project, the California WaterFix, with a nexus to CVP operations.

New and Augmented Water Storage Projects

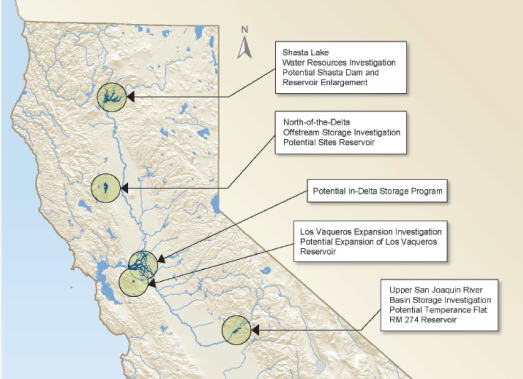

The aforementioned CALFED legislation (P.L. 108-361) also authorized the study of several new or augmented CVP storage projects throughout the Central Valley that have been ongoing for a number of years. These studies include Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation, North of the Delta Offstream Storage Investigation (also known as Sites Reservoir), In-Delta Storage, Los Vaqueros Reservoir Expansion, and Upper San Joaquin River/Temperance Flat Storage Investigation (Figure 6). Although the recommendations of these studies would normally be subject to congressional approval, Section 4007 of the WIIN Act authorized $335 million in Reclamation financial support for new or expanded federal and nonfederal water storage projects and provided that these projects could be deemed authorized, subject to a finding by the Administration that individual projects met certain criteria.80

|

|

Source: California Department of Water Resources, A Resource Management Strategy of the California Water Plan, July 29, 2016. |

In 2018 reporting to Congress, Reclamation recommended an initial list of seven projects that it concluded met the WIIN Act criteria. The projects were allocated $33.3 million in FY2017 funding that was previously appropriated for WIIN Act Section 4007 projects. Congress approved the funding allocations for these projects in enacted appropriations for FY2018 (P.L. 115-141). Four of the projects receiving FY2017 funds ($28.05 million) were CALFED studies that would address water availability in the CVP:81

- Shasta Dam and Reservoir Enlargement Project ($20 million for design and preconstruction);

- North-of-Delta Off-Stream Storage Investigation/Sites Reservoir Storage Project ($4.35 million for feasibility study);

- Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation ($1.5 million for feasibility study); and

- Friant-Kern Canal Subsidence Challenges Project ($2.2 million for feasibility study).

The enacted FY2018 Energy and Water appropriations bill further stipulated that $134 million of the amount set aside for additional water conservation and delivery projects be provided for Section 4007 WIIN Act storage projects (i.e., similar direction as FY2017). The enacted FY2019 bill set aside another $134 million for these purposes.82 Future reporting and appropriations legislation is expected to propose allocation of this and any other applicable funding. Congress also may consider additional directives for these and other efforts to address water supplies in the CVP, including approval of physical construction for one or more of these projects.

Funding by the State of California may also influence the viability and timing of construction for some of the proposed projects. For example, in June 2018, the state announced significant bond funding for Sites Reservoir ($1.008 billion), as well as other projects.83

California WaterFix

In addition to water storage, some have advocated for a more flexible water conveyance system for CVP and SWP water. An alternative was the California WaterFix, a project initiated by the State of California in 2015 to address some of the water conveyance and ecosystem issues in the Bay-Delta. The objective of this project was to divert water from the Sacramento River, north of the Bay-Delta, into twin tunnels running south along the eastern portion of the Bay-Delta and emptying into existing pumps that feed water into the CVP and SWP. In the spring of 2019, Governor Newsom of California canceled the plans for this project and introduced an alternative plan for conveying water through the Delta.

DWR is creating plans to construct a single tunnel to convey water from the Sacramento River to the existing pumps in the Bay-Delta. DWR's stated reasons for supporting this approach are to protect water supplies from sea-level rise, saltwater intrusion, and earthquakes.84 The new plan is expected to take a "portfolio" approach that focuses on a number of interrelated efforts to make water supplies climate resilient. This approach includes actions such as strengthening levees, protecting Delta water quality, and recharging groundwater, according to DWR.85 This project will require a new environmental review process for federal and state permits. It is being led by the Delta Conveyance Design and Construction Authority, a joint powers authority created by public water agencies to oversee the design and construction of the new conveyance system.86 DWR is expected to oversee the planning effort. The cost of the project is anticipated to be largely paid by public water agencies. The federal government's role in this project beyond evaluating permit applications and maintaining related CVP operations has not been defined.

Congressional Interest

Congress plays a role in CVP water management and has previously attempted to make available additional water supplies in the region by facilitating efforts such as water banking, water transfers, and construction of new and augmented storage. In 2016, Congress enacted provisions aiming to benefit the CVP and the SWP, including major operational changes in the WIIN Act and additional appropriations for western drought response and new water storage that have benefited (or are expected to benefit) the CVP. Congress also continues to consider legislation that would further alter CVP operational authorities and responsibilities related to individual units of the project. The below section discusses some of the main issues related to the CVP that may receive attention by Congress.

CVP Operations Under the WIIN Act and Other Authorities87

According to Reclamation, there was limited implementation of many of the WIIN Act's operational authorities. Reportedly, pursuant to the WIIN Act, communication and transparency between Reclamation and other agencies have on occasion increased for some operational decisions, allowing for reduced or rescheduled pumping restrictions.88 Additionally, in the spring of 2018, WIIN Act allowances of relaxed restrictions on inflow-to-export ratios were used to effect a transfer resulting in additional exports of 50,000-60,000 AF of water.89 Reclamation noted, however, that hydrology during 2017 and 2018 affected the agency's ability to implement some of the act's provisions. In some cases, Reclamation proposed other federal operational changes pursuant to the WIIN Act that reportedly were deemed incompatible with state requirements.90

Most of the WIIN Act's operational provisions are set to expire in 2021 (five years after the bill's enactment) and have not been proposed for extension in the 116th Congress. However, even though the provisions may expire, Reclamation has stated that its recently revised BiOps (see below) are consistent with congressional direction to maximize water supplies found in Section 4001 of the WIIN Act. Reclamation also reports that the general principles in Sections 4002-4003 of the WIIN Act have been incorporated into its recent operational changes.91 Thus, even if the WIIN Act's CVP directives expire, many of them will remain manifest in CVP operations.

As previously noted, the Administration has finalized changes to CVP operations. Congress may be interested in oversight of these modified operations and the process underpinning these changes. Observers are likely to focus on the extent to which the changes provide for increased water deliveries relative to pre-reconsultation baselines for CVP and SWP contractors and any related effects on species and water quality. Congress also may be interested in recent disagreements between state and federal project operators related to proposed operating procedures and species protections, including how these disagreements may affect the historical norms of coordinated project operations and what this might mean for water deliveries. Proposed voluntary agreements under the Bay Delta Water Quality Plan may also receive congressional attention in this context.

Previous Congresses have considered legislation proposing other changes to CVP operations. For instance, in the 115th Congress, H.R. 23, the Gaining Responsibility on Water Act (GROW Act), incorporated a number of provisions that were included in previous California drought legislation in the 112th, 113th, and 114th Congresses but were not enacted in the WIIN Act. The GROW Act included provisions that would have relaxed some environmental protections and restrictions imposed by CVPIA, ESA, CWA, and SJRRP, and had the potential to increase SOD water exports under some scenarios. This legislation was not enacted.

New Water Storage Projects

As previously noted, Reclamation and the State of California have funded the study of new water storage projects in recent years. Congress may opt to provide additional direction for these and other efforts to develop new water supplies for the CVP in future appropriations acts and reports. In addition, Congress may consider oversight, authorization, and/or funding for these projects. Some projects, such as the Shasta Dam and Reservoir Enlargement Project, have the potential to augment CVP water supplies but have also generated controversy for their potential to conflict with the intent of certain state laws.92 Although Reclamation has indicated its interest in pursuing the Shasta Dam raise project, the state opposed the project under Governor Jerry Brown's Administration and has continued its opposition during Governor Gavin Newsom's Administration; it is unclear how such a project might proceed absent state regulatory approvals and financial support. As previously noted, in early 2018, Reclamation proposed and Congress agreed to $20 million in design and preconstruction funding for the project.93 The Trump Administration recommended an additional $75 million in February 2019, but this funding was not approved in enacted Energy and Water Development appropriations for FY2020.94

In addition to the Shasta Dam and Reservoir Enlargement Project, Congress approved Reclamation-recommended study funding for Sites Reservoir/North of Delta Offstream Storage (NODOS), Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation, and the Friant-Kern Canal Subsidence Challenges Project. From FY2017 to FY2020, Congress provided Reclamation with $469 million for new water storage projects authorized under Section 4007 of the WIIN Act. A significant share of this total is expected to be used on CVP and related water storage projects in California. Once the appropriations ceiling for these projects has been reached, funding for storage projects under Section 4007 would need to be extended by Congress before projects could proceed further. S. 1932, the Drought Resiliency and Water Supply Infrastructure Act, would amend and extend the authorization for new storage provisions under Section 4007.

Legislation in the 116th Congress has been introduced to expedite certain water storage studies in the Central Valley and could also provide funding for their eventual construction. For instance, Section 5 of H.R. 2473 would direct the Secretary of the Interior to complete, as soon as practicable, the ongoing feasibility studies associated with Sites Reservoir, Del Puerto Canyon Reservoir, Los Vaqueros Reservoir, and San Luis Reservoir. Section 2 of the same legislation would authorize $100 million per year for fiscal years 2030 to 2060, without further appropriation (i.e., mandatory funding) for new Reclamation surface or groundwater storage projects. Separately, H.R. 5316 would authorize $200 million in funding from FY2020 to FY2023, at a maximum federal cost share of 50%, for acceleration and completion of repairs to projects in reclamation states that have lost 50% or more of their design carrying capacity. Presumably, repairs to the Friant-Kern Canal would be eligible for this funding. The same legislation would also increase authorized appropriations for the SJRRP by $200 million.

Concluding Observations

The CVP is one of the largest and most complex water storage and conveyance projects in the world. Congress has regularly expressed interest in CVP operations and allocations, in particular pumping in the Bay-Delta. In addition to ongoing oversight of project operations and previously enacted authorities, a number of developing issues and proposals related to the CVP have been of interest to congressional decisionmakers. These include study and approval of new water storage and conveyance projects, updates to the state's Bay-Delta Water Quality Plan, and a multipronged effort by the Trump Administration to make available more water for CVP water contractors, in particular those south of the Delta. Future drought or other stressors on California water supplies are likely to further magnify these issues.

Appendix. CVP Water Contractors

The below sections provide a brief discussion some of the major contractor groups and individual contractors served by the CVP.

Sacramento River Settlement Contractors and San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors (Water Rights Contractors)

CVP water is generally made available for delivery first to those contractors north and south of the Delta with water rights that predate construction of the CVP: the Sacramento River Settlement Contractors and the San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors. (These contractors are sometimes referred to collectively as water rights contractors.) Water rights contractors typically receive 100% of their contracted amounts in most water year types. During water shortages, their annual maximum entitlement may be reduced, but not by more than 25%.

Sacramento River Settlement Contractors include the 145 contractors (both individuals and districts) that diverted natural flows from the Sacramento River prior to the CVP's construction and executed a settlement agreement with Reclamation that provided for negotiated allocation of water rights. Reclamation entered into this agreement in exchange for these contractors withdrawing their protests related to Reclamation's application for water rights for the CVP.

The San Joaquin River Exchange Contractors are four irrigation districts that agreed to "exchange" exercising their water rights to divert water on the San Joaquin and Kings Rivers for guaranteed water deliveries from the CVP (typically in the form of deliveries from the Delta-Mendota Canal and waters north of the Delta). During all years except for when critical conditions are declared, Reclamation is responsible for delivering 840,000 AF of "substitute" water to these users (i.e., water from north of the Delta as a substitute for San Joaquin River water). In the event that Reclamation is unable to make its contracted deliveries, these Exchange Contractors have the right to divert water directly from the San Joaquin River, which may reduce water available for other San Joaquin River water service contactors.

CVP's Friant Division contractors receive water stored behind Friant Dam (completed in 1944) in Millerton Lake. This water is delivered through the Friant-Kern and Madera Canals. The 32 Friant Division contractors, who irrigate roughly 1 million acres on the San Joaquin River, are contracted to receive two "classes" of water: Class 1 water is the first 800,000 AF available for delivery;95 Class 2 water is the next 1.4 million AF available for delivery. Some districts receive water from both classes. Generally, Class 2 waters are released as "uncontrolled flows" (i.e., for flood control concerns), and may not necessarily be scheduled at a contractor's convenience.

Deliveries to the Friant Division are affected by a 2009 congressionally enacted settlement stemming from Friant Dam's effects on the San Joaquin River.96 The settlement requires reductions in deliveries to Friant users for protection of fish and wildlife purposes. In some years, some of these "restorations flows" have been made available to contractors for delivery as Class 2 water.

Unlike most other CVP contractors, Friant Division contractors have converted their water service contracts to repayment contracts and have repaid their capital obligation to the federal government for the development of their facilities. In years in which Reclamation is unable to make contracted deliveries to Exchange Contractors, these contractors can make a "call" on water in the San Joaquin River, thereby requiring releases from Friant Dam that otherwise would go to Friant contractors.

South-of-Delta (SOD) Water Service Contractors: Westlands Water District

As shown in Figure 3, SOD water service contractors account for a large amount (2.09 million AF, or 22.1%) of the CVP's contracted water. The largest of these contractors is Westlands Water District, which consists of 700 farms covering more than 600,000 acres in Fresno and Kings Counties. In geographic terms, Westlands is the largest agricultural water district in the United States; its lands are valuable and productive, producing more than $1 billion of food and fiber annually.97 Westlands' maximum contracted CVP water is in excess of 1.2 million AF, an amount that makes up more than half of the total amount of SOD CVP water service contracts and significantly exceeds any other individual CVP contactor.98 However, due to a number of factors, Westlands often receives considerably less water on average than it did historically.

Westlands has been prominently involved in a number of policy debates, including proposals to alter environmental requirements to increase pumping south of the Delta. Westlands is also involved in a major proposed settlement with Reclamation, the San Luis Drainage Settlement. The settlement would, among other things, forgive Westlands' share of federal CVP repayment responsibilities in exchange for relieving the federal government of its responsibility to construct drainage facilities to deal with toxic runoff associated with naturally occurring metals in area soils.

Central Valley Wildlife Refuges

The 20,000 square mile California Central Valley provides valuable wetland habitat for migratory birds and other species. As such, it is the home to multiple state and federally-designated wildlife refuges north and south of the Delta. These refuges provide managed wetland habitat that receives water from the CVP and other sources.

The Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA; P.L. 102-575),99 enacted in 1992, sought to improve conditions for fish and wildlife in these areas by providing them coequal priority with other project purposes. CVPIA also authorized a Refuge Water Supply Program to acquire approximately 555,000 AF annually in water supplies for 19 Central Valley refuges administered by three managing agencies: California Department of Fish and Wildlife, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Grassland Water District (a private landowner). Pursuant to CVPIA, Reclamation entered into long-term water supply contracts with the managing agencies to provide these supplies.

Authorized refuge water supply under CVPIA is divided into two categories: Level 2 and Level 4 supplies. Level 2 supplies (approximately 422,251 AF, except in critically dry years, when the allocation is reduced to 75%) are the historical average of water deliveries to the refuges prior to enactment of CVPIA.100 Reclamation is obligated to acquire and deliver this water under CVPIA, and costs are 100% reimbursable by CVP contractors through a fund established by the act, the Central Valley Project Restoration Fund (CVPRF; see previous section, "Central Valley Project Improvement Act"). Level 4 supplies (approximately 133,264 AF) are the additional increment of water beyond Level 2 supplies for optimal wetland habitat development. This water must be acquired by Reclamation through voluntary measures and is funded as a 75% federal cost (through the CVPRF) and 25% state cost.

In most cases, the Level 2 requirement is met; however, Level 4 supplies have not always been provided in full for a number of reasons, including a dearth of supplies due to costs in excess of available CVPRF funding and a lack of willing sellers. In recent years, costs for the Refuge Water Supply Program (i.e., the costs for both Level 2 and Level 4 water) have ranged from $11 million to $20 million.