Introduction: Major Issues for U.S.-Israel Relations

Israel (see Appendix A) has forged close bilateral cooperation with the United States in many areas; issues with significant implications include the following.

- Israeli domestic political issues, especially questions surrounding the new unity government forged by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Benny Gantz during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Israeli-Palestinian issues and U.S. policy, including the Trump Administration's peace plan released in January 2020 and issues surrounding possible Israeli West Bank annexation.

- Israel's security cooperation with the United States.

- Shared U.S.-Israel concerns about Iran's nuclear program and regional influence, including with Lebanon-based Hezbollah, Syria, and Iraq.

For background information and analysis on these and other topics, including aid, arms sales, and missile defense cooperation, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti; and CRS Report RL33222, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, by Jeremy M. Sharp.

Domestic Issues: Unity Government, Possible West Bank Annexation, and COVID-19

On May 17, 2020, Prime Minister Netanyahu of the Likud party and his main political rival Benny Gantz of the Kahol Lavan (Blue and White) party formed a unity government with majority backing from the Israeli Knesset that was elected on March 2 (see Appendix B). Under the unity agreement, Netanyahu is expected to serve as prime minister and Gantz as alternate prime minister and defense minister for the first 18 months of that time, at which point Gantz is set to become prime minister for the next 18 months, with Netanyahu as his alternate.1

Two previous elections—in April and September 2019—did not produce a government backed by a Knesset majority, and the Netanyahu-Gantz agreement prevented Israel from going to an election later this year that would have been the fourth in two years. Netanyahu and Gantz cited the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to address its public health, economic, and other implications for Israel as a major reason for forming a unity government and averting a fourth election.

|

COVID-19: Implications for Israel Relative to many developed countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has not led to a systemic public health crisis to date in Israel. Measures that significantly constrained economic activity in March and April 2020 are gradually being phased out. The Netanyahu-Gantz unity deal envisions that the government will focus largely on issues related to COVID-19 for its first few months. According to projections, Israel's generally vibrant and diversified economy could experience continuing hardship into 2021 or beyond (see Appendix A), with a number of possible factors influencing the intensity and duration of the downturn.2 Israel has been coordinating on COVID-19 measures with Palestinian officials in both the West Bank and Gaza. |

Gantz's decision in March to accept the principle of a unity government departed from his campaign pledge not to join with Netanyahu because of the criminal indictments against him for corruption (see Appendix C). At the time of this decision, Gantz had previously received Knesset majority support to lead government formation efforts and consider legislation to prevent Netanyahu from serving as prime minister. However, two members of his own party (Kahol Lavan) stalemated those government formation efforts by refusing to serve in a coalition supported by the Arab-led Joint List. When Gantz decided to pursue a unity government, Kahol Lavan split, with other key members Yair Lapid and Moshe Ya'alon denouncing Gantz's decision and leading their Yesh Atid-Telem party into the opposition.

|

Key Aspects of Unity Government Observers analyzing the Netanyahu-Gantz deal have identified various perceived benefits to the unity agreement for both sides.3 Potential benefits for Netanyahu include his continuation as prime minister and apparent ability to remain in government until he exhausts all appeals (if convicted), his ability to hold votes on West Bank annexation, an effective veto over appointments of key judiciary and justice sector officials, and holding sway with the Knesset's right-of-center majority even during Gantz's time as prime minister. Potential benefits for Gantz include Netanyahu's lack of immunity from criminal proceedings, safeguards intended to ensure that Gantz will become prime minister 18 months through the government's term (as agreed), co-ownership of the governing and legislative agenda, and effective control over half the cabinet and positions (including the defense, foreign, and justice ministries) with significant influence on national security and rule of law in Israel. Despite the details of this political agreement, it is unclear whether either party would be able to compel its legal enforcement, as in the case if Netanyahu were to refuse to step down as prime minister.4 New elections would take place in the event that the government is dissolved. Although under the terms of the unity agreement, Gantz would serve as caretaker prime minister before such elections if Netanyahu is responsible for the dissolution, some commentators assert that Netanyahu could hold an advantage—and perhaps even gain a mandate to pass legislation reinstating himself—given various factors, including his enduring political appeal and Kahol Lavan's March 2020 split.5 Some of the elements of the unity agreement that have been codified in Israeli law remain subject to legal challenge in Israel's Supreme Court.6 Some critics have voiced concern that certain provisions crafted to accommodate the political exigencies of the Netanyahu-Gantz deal by diminishing the Knesset's role could undermine democracy in Israel.7 |

Arguably, the most significant aspect of the Netanyahu-Gantz deal for U.S. policy is that it explicitly allows the cabinet and Knesset to vote on annexing West Bank territory—in coordination with the United States—after July 1, 2020. Pursuant to the Trump Administration's January 2020 peace plan, a U.S.-Israel joint committee has been meeting to finalize the geographical contours of West Bank areas—including Jewish settlements and much of the Jordan Valley8—that the U.S. plan anticipates would be part of Israel. U.S. officials have stated support for Israel annexing these areas after the committee generates these detailed maps. The Palestinians, Arab states, many other international actors, and some Members of Congress oppose Israeli annexation of West Bank areas because of concerns that it could contravene international law and existing Israeli-Palestinian agreements, and negatively affect regional cooperation. It is unclear whether this opposition will affect Israeli or Trump Administration actions. For more detailed information, see "Possible Israeli West Bank Annexation" and "Regional and International Views" below.

The issue of annexation has become increasingly prominent in Israeli domestic politics. In each of Israel's three recent electoral campaigns (April 2019, September 2019, March 2020), Netanyahu said he would move forward with annexation if he could form a government. Some observers assert that Netanyahu's rhetorical support for annexation helps him maintain support among right-of-center constituencies for political survival amid his legal difficulties, and thus question how much he will actually pursue annexation.9 Gantz, in connection with the release of the U.S. plan in January 2020, stated his support for annexation to the extent that it could be coordinated with the international community. The Netanyahu-Gantz deal calls for Israel to engage in dialogue with international actors on the annexation issue "with the aim of preserving security and strategic interests including regional security, preserving existing peace agreements and working towards future peace agreements."10 However, the unity agreement does not permit Gantz to block efforts by Netanyahu to bring the issue to a vote. During his unity negotiations with Netanyahu, Gantz reportedly expressed a preference for a limited plan of annexation that would apply Israeli law to areas with a high concentration of settlers.11

Israeli-Palestinian Issues Under the Trump Administration12

President Trump has expressed interest in helping resolve the decades-old Israeli-Palestinian conflict. However, his policies have largely favored Israeli positions, thus alienating Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman and Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas.

Selected U.S. Actions Impacting Israeli-Palestinian Issues

|

December 2017 |

President Trump recognizes Jerusalem as Israel's capital, prompting the PLO/PA to cut off high-level diplomatic relations with the United States |

|

May 2018 |

U.S. embassy opens in Jerusalem |

|

August 2018 |

Administration ends contributions to U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) |

|

September 2018 |

Administration reprograms FY2017 economic aid for the West Bank and Gaza to other locations; announces closure of PLO office in Washington, DC |

|

January 2019 |

As a result of the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-253), the Administration ends all bilateral U.S. aid to the Palestinians |

|

March 2019 |

The U.S. consulate general in Jerusalem—previously an independent diplomatic mission to the Palestinians—is subsumed under the authority of the U.S. embassy to Israel; President Trump recognizes Israeli sovereignty in the Golan Heights |

|

June 2019 |

At a meeting in Bahrain, U.S. officials roll out $50 billion economic framework for Palestinians in the region tied to the forthcoming peace plan; PLO/PA officials reject the idea of economic incentives influencing their positions on core political demands |

|

November 2019 |

Secretary of State Michael Pompeo says that the Administration disagrees with a 1978 State Department legal opinion stating that Israeli West Bank settlements are inconsistent with international law |

|

January 2020 |

President Trump releases peace plan |

On January 28, President Trump released a long-promised "Peace to Prosperity" plan for Israel and the Palestinians,13 after obtaining expressions of support from both Netanyahu and Gantz. Prospects for holding negotiations seem dim given concerted opposition from Abbas and other Palestinian leaders, and Netanyahu's announced intention to annex parts of the West Bank. Members of Congress have had mixed reactions to the plan.14

Key Points of the U.S. Plan

The plan suggests the following key outcomes as the basis for future Israeli-Palestinian negotiations:15

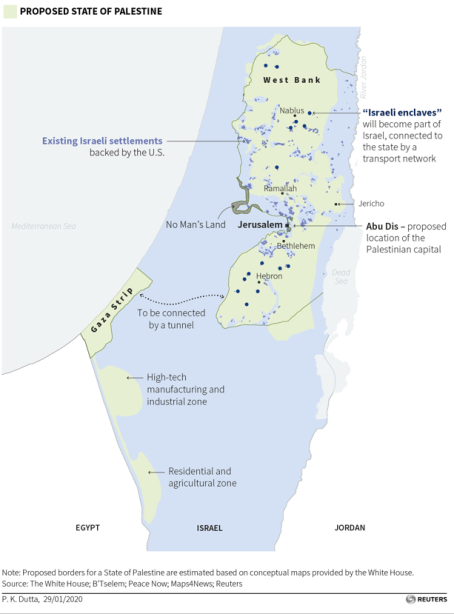

- Borders and settlements. Israel would acquire sovereignty over about 30% of the West Bank (see Figure D-1), including settlements and most of the Jordan Valley.16 The Palestinians could eventually acquire a limited form of sovereignty (as described below) over the remaining territory. This includes areas that the Palestinian Authority (PA) currently administers, along with some territory currently belonging to Israel (with few Jewish residents) that the Palestinians would acquire via swaps to partially compensate for West Bank territory taken by Israel. Some areas with minimal contiguity would be connected by roads, bridges, and tunnels (see Figure D-2). Neither Israeli settlers nor Palestinian West Bank residents would be forced to move. The plan anticipates that an agreement could transfer some largely Israeli Arab communities—including an area called the "Arab Triangle"—to a future Palestinian state. In the days after the plan's release, hundreds of residents of the Triangle communities protested the possibility that their citizenship could change, prompting senior Israeli officials to state the Triangle communities would not be involved in any border revision.17

- Jerusalem and its holy sites. Israel would have sovereignty over nearly all of Jerusalem, with the Palestinians able to obtain some small East Jerusalem areas on the other side of an Israeli separation barrier.19 Taken together, the plan and its accompanying White House fact sheet say that the "status quo" on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif—which prohibits non-Muslim worship there—would continue, along with Jordan's custodial role regarding Muslim holy sites.20 However, the plan also says, "People of every faith should be permitted to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, in a manner that is fully respectful to their religion, taking into account the times of each religion's prayers and holidays, as well as other religious factors." A day after the plan's release, U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman clarified that the status quo would not change absent the agreement of all parties, while adding that the Administration hoped that an eventual accord would allow Jews to pray on the Temple Mount as part of greater openness "to religious observance everywhere."21

- Security. Israel would retain overall security control over the entire West Bank permanently, though Palestinians would potentially assume more security responsibility, over time, in territory they administer.22

- Palestinian refugees. Palestinian refugee claims would be satisfied through internationally funded compensation and resettlement outside of Israel (i.e., no "right of return" to Israel) in the West Bank, Gaza, and third-party states.

- Palestinian statehood. The Palestinians could obtain a demilitarized state within the areas specified in Figure D-2 and Figure C-3, with a capital in Abu Dis or elsewhere straddling the East Jerusalem areas mentioned above and their outskirts.23 Statehood would depend on the Palestinians meeting specified criteria over the next four years that present considerable domestic and practical challenges.24 Such criteria include disarming Hamas in Gaza, ending certain international initiatives and financial incentives for violence, and recognizing Israel as "the nation state of the Jewish people."25

|

Settlement-Related Announcements After the Plan's Release In February, Netanyahu and his caretaker government announced intentions to move forward with plans or construction for Jewish settlements in areas of East Jerusalem (where some refer to settlements as neighborhoods) and the West Bank—including an area known as E-1—that could significantly obstruct territorial contiguity between Palestinian population centers.18 |

Possible Israeli West Bank Annexation

After the release of the U.S. plan, statements from Trump Administration officials influenced Prime Minister Netanyahu's timetable for having the Israeli government annex West Bank settlements and the Jordan Valley. Netanyahu's initial proposal to act immediately—supported by some comments from U.S. ambassador to Israel David Friedman26—changed in light of January 30 remarks by White House Senior Adviser Jared Kushner. Kushner said that technical discussions involving a U.S.-Israel committee to pinpoint areas earmarked for eventual Israeli sovereignty (see Figure D-1) could begin immediately, but that finalizing them would take "a couple of months." Kushner also said that an Israeli government would need to be in place "in order to move forward" with annexation.27 The U.S.-Israel mapping committee began meeting in February.28 On March 5, one source reported that Kushner told Members of Congress that the United States would be ready to support Israeli annexation within a matter of months if the Palestinians are unwilling to negotiate with Israel on the basis of the U.S. plan.29

As discussed above, the Israeli government formed in May 2020 has the authority to bring annexation to a vote starting in July. After the government's swearing-in on May 17, Netanyahu stated his intent to bring the issue quickly to a cabinet vote.30 Whether and how a vote takes place may depend on various considerations, including the progress of the U.S.-Israel mapping committee and challenges in achieving consensus among Israeli officials and other key stakeholders.31 A senior State Department official has been cited as saying that the government could "take a while" to reach consensus on annexation in view of various factors, including concerns among Arab states.32 In early May, Ambassador Friedman indicated that the United States is prepared to recognize Israel's application of sovereignty over areas identified by the mapping committee if Israel agrees not to expand settlements beyond those areas, and remains willing to negotiate with Palestinians for their statehood on the basis of the U.S. plan.33 During a May 13 visit to Israel, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo said that Israel has the "right and the obligation" to decide whether and how to proceed with annexation, while also saying that he discussed with Netanyahu and Gantz how to "bring about an outcome in accordance with the [U.S.] vision of peace" and that they would need to "find a way together to proceed."34

Annexation could potentially worsen Israeli-Palestinian tensions and the prospects of reaching a negotiated two-state solution. On May 13, PLO Chairman and PA President Abbas said that the Palestinians would reconsider their position and be absolved of all agreements and understandings with Israel and the United States if Israel declares the annexation of "any part of our occupied lands."35 According to three former senior Israeli security officials, annexation could increase rather than decrease Israel's responsibility for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza if it reduces Palestinian willingness to coordinate on security and observe cease-fires.36 Two prominent former U.S. officials have argued that annexation of all settlements and the Jordan Valley would "doom Israel to becoming a binational state that fundamentally alters its identity," while a more limited plan of annexation might not foreclose a two-state solution.37

|

Annexation Under Israeli Law Since Israel's founding in 1948, it has effectively annexed two territories: East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, both of which Israel captured in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. Shortly after the war, the Israeli government expanded Jerusalem's municipal boundaries to include all of the previously Jordanian-held East Jerusalem and some surrounding West Bank territory, and proclaimed the municipality to be Israel's capital. The Knesset passed a Basic Law in July 1980 stating that the jurisdiction of Jerusalem runs throughout the expanded municipal boundaries. In December 1981, the Knesset passed a law stating that the "Law, jurisdiction and administration of the state [of Israel] shall apply to the Golan Heights."38 The U.N. Security Council, in Resolutions 478 (1980) and 497 (1981), respectively, affirmed that both Knesset laws were violations of international law. According to one Israeli legal scholar, under domestic law Israel can apply its law to new territory via governmental decree (if the territory was previously part of the British Mandate of Palestine) or Knesset legislation.39 Some norms of Israeli law already apply to West Bank settlements, "either through application of personal jurisdiction over the settlers, or through military decrees that incorporated Israeli law into the law applicable to all or parts of the West Bank."40 According to one article citing various Israeli legal experts, Israel could take a range of approaches to annexation or applying its law to West Bank areas.41 The full application of Israeli law to settlements could necessitate significant adaptation in matters such as property registry and land-use planning. Also, if Israel applies its civilian law to the Jordan Valley or other West Bank areas with Palestinian populations currently subject to Jordanian and military law, the legal transition could potentially impact individual property rights and business licenses.42 Since 2016, various Knesset members have reportedly proposed bills that would apply Israeli law, jurisdiction, administration, and formal sovereignty in specified West Bank areas.43 |

Annexation may be contrary to international law,44 including various U.N. Security Council resolutions and existing Israeli-Palestinian agreements (the Oslo Accords of the 1990s) that provide for resolving the status of the West Bank and Gaza Strip via negotiations.45 U.N. Security Council Resolution 2334, adopted in December 2016 with the United States (under the Obama Administration) abstaining, stated that settlements established by Israel in "Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, including East Jerusalem," constitute "a flagrant violation under international law" and a "major obstacle" to a two-state solution and a "just, lasting and comprehensive peace." In December 2019, the House (by a vote of 226-188, with two voting present) passed H.Res. 326, which called for any future U.S. peace proposal to expressly endorse a two-state solution and discouraged steps such as "unilateral annexation of territory or efforts to achieve Palestinian statehood status" outside negotiations.

Responses by Congress or other U.S. actors to Israeli annexation could depend on various factors. These may include how closely any annexation might be coordinated with the Administration; responses from Palestinians, Arab states, and other international actors; and the timing, territorial extent, legal nature, and physical enforcement of any annexation.46

Regional and International Views

The U.S. plan and the possibility of Israeli West Bank annexation have elicited various regional and international reactions. While some key actors have voiced hope that the plan's release would lead to the resumption of Israeli-Palestinian talks, others have expressed caution or criticism about the plan and its possible implications.

The impact of the plan or possible Israeli annexation on neighboring Jordan is an important issue.47 Israeli security officials regard Jordan, with which Israel has a peace treaty, as a key regional buffer for Israel. Jordan also hosts key U.S. military assets. While Jordan's monarchy maintains discreet security cooperation with Israel, much of its population—a majority of which is of Palestinian origin—holds negative views about Israel-Jordan relations,48 which have become strained over the past year.49 Additionally, Palestinians might look to Jordan to take greater responsibility for them if their own national aspirations remain unfulfilled.50

Jordanian officials have expressed concerns about the plan and possible annexation. After the plan's release, Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi warned against the "dangerous consequences of unilateral Israeli measures, such as the annexation of Palestinian lands, the building and expansion of illegal Israeli settlements on occupied Palestinian lands and encroachments on the Holy Sites in Jerusalem, that aim at imposing new realities on the ground."51 Following the announcement of the Israeli unity government in April, Foreign Minister Safadi reportedly asked several foreign governments to discourage Israel from annexing the Jordan Valley and other parts of the West Bank.52 Then, in a May interview, King Abdullah II said, "If Israel really annexed the West Bank in July, it would lead to a massive conflict with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan." When asked if he would suspend Jordan's peace treaty with Israel, the King said, "I don't want to make threats and create an atmosphere of loggerheads, but we are considering all options."53

Arab states' positions could influence U.S. and Israeli actions.54 Some observers have surmised that some key Arab states' shared interests with Israel on Iran and other matters may lead them to be less insistent than in the past on Israel meeting Palestinian demands.55 After a meeting of the foreign ministers of the League of Arab States on February 1, the Arab League issued a communique saying that it would not cooperate with the United States to implement the U.S. plan and that Israel should not forcibly carry it out.56 It stated its view that the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002 remains the proper basis for a negotiated Israeli-Palestinian peace.57 After a virtual meeting of Arab League foreign ministers on April 30, the ministers issued a joint statement saying that annexation of any part of the lands occupied in 1967 would be a "new war crime" against the Palestinians and urged the United States to withdraw its support from enabling Israel's plans.58

Other international reactions have encouraged the idea of resuming Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, but raised concerns about parts of the U.S. plan or possible Israeli annexation.59 Senior European Union (EU) and United Nations officials have warned Israel that annexation by its new government would violate international law,60 and reports suggest that the EU or its member states may consider reducing some forms of economic cooperation with Israel in response to annexation.61 Additionally, annexation could come under investigation by the International Criminal Court (ICC),62 given that the ICC prosecutor has announced her intention to investigate possible war crimes in the West Bank and Gaza if a pre-trial chamber decides that the ICC has jurisdiction there.63

Gaza and Its Challenges

The Gaza Strip—controlled by the Sunni Islamist group Hamas (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization)—faces difficult and complicated political, economic, and humanitarian conditions.64 Palestinian militants in Gaza regularly clash with Israel's military as it patrols Gaza's frontiers with Israel, and the clashes periodically escalate toward larger conflict. Hamas and Israel are reportedly working through Egypt and Qatar in efforts to establish a long-term cease-fire around Gaza that could ease Israel-Egypt access restrictions for people and goods.

U.S. Security Cooperation

While Israel maintains robust military and homeland security capabilities, it also cooperates closely with the United States on national security matters. U.S. law requires the executive branch to take certain actions to preserve Israel's "qualitative military edge," or QME.65 Additionally, a 10-year bilateral military aid memorandum of understanding (MOU)—signed in 2016—commits the United States to provide Israel $3.3 billion in Foreign Military Financing and to spend $500 million annually on joint missile defense programs from FY2019 to FY2028, subject to congressional appropriations. The United States and Israel do not have a mutual defense treaty or agreement that provides formal U.S. security guarantees,66 though some discussions about the possibility of a treaty have apparently taken place since September 2019.67

Iran and the Region

Israeli officials cite Iran as a primary concern to Israeli officials, largely because of (1) antipathy toward Israel expressed by Iran's revolutionary regime, (2) Iran's broad regional influence (especially in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon),68 and (3) Iran's nuclear and missile programs and advanced conventional weapons capabilities. Israel and Arab Gulf states have cultivated closer relations with one another in efforts to counter Iran.

Iranian Nuclear Issue and Regional Tensions

Prime Minister Netanyahu has sought to influence U.S. decisions on the international agreement on Iran's nuclear program (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA). He opposed the JCPOA when it was negotiated by the Obama Administration, and welcomed President Trump's May 2018 withdrawal of the United States from the JCPOA and accompanying reimposition of U.S. sanctions on Iran's core economic sectors. Facing the intensified U.S. sanctions, Iran has reduced its compliance with the 2015 agreement.

U.S.-Iran tensions since the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA have led to greater regional uncertainty, with implications for Israel.69 Some Israelis have voiced worries about how Iran's apparent ability to penetrate Saudi air defenses and target Saudi oil facilities could transfer to efforts in targeting Israel.70

Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon

Hezbollah

Lebanese Hezbollah is Iran's closest and most powerful non-state ally in the region. Hezbollah's forces and Israel's military have sporadically clashed near the Lebanese border for decades—with the antagonism at times contained in the border area, and at times escalating into broader conflict.71 Speculation persists about the potential for wider conflict and its regional implications.72 Israeli officials have sought to draw attention to Hezbollah's buildup of mostly Iran-supplied weapons—including reported upgrades to the range, precision, and power of its projectiles—and its alleged use of Lebanese civilian areas as strongholds.73

Ongoing tension between Israel and Iran raises questions about the potential for Israel-Hezbollah conflict. Various sources have referenced possible Iran-backed Hezbollah initiatives to build precision-weapons factories in Lebanon.74 In late 2018 and early 2019, Israel's military undertook an effort—dubbed "Operation Northern Shield"—to seal six Hezbollah attack tunnels to prevent them from crossing into Israel.75 In August 2019, Israel may have conducted airstrikes targeting Hezbollah personnel and advanced drone and missile technology in Syria and Lebanon.76 Hezbollah appeared to respond to Israel in early September with cross-border fire from Lebanon targeting an Israeli military unit,77 amid reports that Hezbollah sought to retaliate but avoid escalation toward war.78 One April 2020 media report cited examples to suggest that Israel and Hezbollah may be providing warnings and other signals that are meant to deter one another without leading to military escalation—with Israeli security officials debating whether such leniency with Hezbollah serves Israeli interests.79

Syria and Iraq: Reported Israeli Airstrikes Against Iran-Backed Forces

Israel has reportedly undertaken airstrikes in conflict-plagued Syria and Iraq based on concerns that Iran and its allies could pose threats to Israeli security from there. Iran's westward expansion of influence into Iraq and Syria over the past two decades has provided it with more ways to supply and support Hezbollah, apparently leading Israel to broaden its regional theater of military action.80 The U.S. base at At Tanf in southern Syria reportedly serves as an impediment to Iranian efforts to create a land route for weapons from Iran to Lebanon.81 Russia, its airspace deconfliction mechanism with Israel, and some advanced air defense systems that it has deployed or transferred to Syria also influence the various actors involved.82

Since 2018, Israeli and Iranian forces have repeatedly targeted one another in Syria or around the Syria-Israel border. After Iran helped Syria's government regain control of much of the country, Israeli leaders began pledging to prevent Iran from constructing and operating bases or advanced weapons manufacturing facilities in Syria.83 In April 2020, then-Defense Minister Naftali Bennett said that Israeli policy has shifted from blocking Iran's entrenchment in Syria to forcing it out entirely.84 Some Israeli observers cite signs that Iran may be scaling down its activities in Syria.85

In Iraq, reports suggest that in the summer of 2019, Israel conducted airstrikes against weapons depots or convoys that were connected with Iran-allied Shiite militias. A December 2019 media report citing U.S. officials claimed that Iran had built up a hidden arsenal of short-range ballistic missiles in Iraq that could pose a threat to U.S. regional partners, including Israel.86 Perhaps owing to sensitivities involving U.S. forces in Iraq, then-Defense Minister Bennett suggested in February 2020 that Israel would avoid further direct involvement there—leaving any efforts to counter Iran-backed forces in Iraq to the United States.87

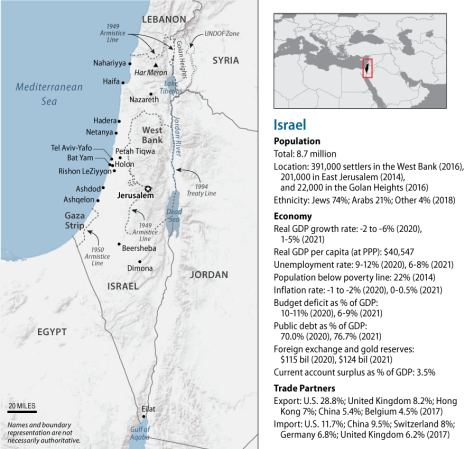

Appendix A. Map and Basic Facts

|

|

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by Hannah Fischer using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2013); the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency GeoNames Database (2015); DeLorme (2014). Fact information from CIA, The World Factbook; Economist Intelligence Unit; IMF World Economic Outlook Database. All numbers are estimates as of 2020 unless specified. Numbers for 2021 are projections. Notes: According to the U.S. executive branch: (1) The West Bank is Israeli occupied with current status subject to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement; permanent status to be determined through further negotiation. (2) The status of the Gaza Strip is a final status issue to be resolved through negotiations. (3) The United States recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital in 2017 without taking a position on the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty. (4) Boundary representation is not necessarily authoritative. Additionally, the United States recognized the Golan Heights as part of Israel in 2019; however, U.N. Security Council Resolution 497, adopted on December 17, 1981, held that the area of the Golan Heights controlled by Israel's military is occupied territory belonging to Syria. The current U.S. executive branch map of Israel is available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/attachments/maps/IS-map.gif. |

Appendix B. Israeli Political Parties in the Knesset and Their Leaders

|

RIGHT |

|

|

|

Likud (Consolidation) – 36 Knesset seats (Coalition) Leader: Binyamin Netanyahu |

|

|

Yisrael Beitenu (Israel Our Home) – 7 seats (Opposition) Leader: Avigdor Lieberman |

|

|

Yamina (Right) – 5 seats (Opposition) Leader: Naftali Bennett |

|

LEFT |

|

|

|

Labor (Avoda) – 3 seats (Coalition) Leader: Amir Peretz |

|

|

Meretz (Vigor) – 3 seats (Opposition) Meretz is a pro-secular Zionist party that supports initiatives for social justice and peace with the Palestinians, and former Prime Minister Ehud Barak's Israel Democratic Party. Leader: Nitzan Horowitz |

|

CENTER |

|

|

|

Kahol Lavan (Blue and White) – 15 seats (Coalition) Centrist party largely formed as an alternative to Prime Minister Netanyahu, ostensibly seeking to preserve long-standing Israeli institutions such as the judiciary, articulate a vision of Israeli nationalism that is more inclusive of Druze and Arab citizens, and have greater sensitivity to international opinion on Israeli-Palestinian issues. Leader: Benny Gantz |

|

|

Yesh Atid-Telem – 16 seats (Opposition) Yesh Atid (There Is a Future) is a centrist party in existence since 2012 that has championed socioeconomic issues such as cost of living and has taken a pro-secular stance. Telem (Hebrew acronym for National Statesman-like Movement) formed in January 2019 by former Defense Minister Moshe Ya'alon as a center-right, pro-nationalist alternative to Netanyahu. The parties merged with Hosen L'Yisrael in early 2019, then split from it in March 2020. Leader: Yair Lapid |

|

|

Derech Eretz (Way of the Land) – 2 seats (Coalition) Center-right faction formed from the split of Kahol Lavan in March 2020. Leaders: Zvi Hauser and Yoaz Hendel |

|

|

|

|

|

Shas (Sephardic Torah Guardians) – 9 seats (Coalition) Leader: Aryeh Deri |

|

|

United Torah Judaism – 7 seats (Coalition) Leader: Yaakov Litzman |

|

|

|

|

|

Joint List – 15 seats (Opposition) Electoral slate featuring four Arab parties that combine socialist, Islamist, and Arab nationalist political strains: Hadash (Democratic Front for Peace and Equality), Ta'al (Arab Movement for Renewal), Ra'am (United Arab List), Balad (National Democratic Assembly). Leader: Ayman Odeh |

Sources: Various open sources.

Note: Knesset seat numbers based on results from the March 2, 2020, election. The Gesher (Bridge) party has a single member of the Knesset, Orly Levi-Abekasis, who is part of the coalition. Rafi Peretz split from the Yamina party to join the coalition.

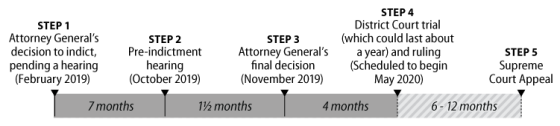

Appendix C. Indictments Against Netanyahu and Steps of the Legal Process

|

Indictments |

|

Case 1000: Netanyahu received favors from Hollywood mogul Arnon Milchan and Australian billionaire James Packer, in return for taking actions in Milchan's favor. The charge: Fraud and breach of trust Netanyahu's defense: There is no legal problem in receiving gifts from friends; did not know that his family members requested gifts. |

|

Case 2000: Netanyahu and Yedioth Ahronoth publisher Arnon Mozes struck a deal: Favorable coverage for Netanyahu in return for limiting the circulation of the Sheldon Adelson-owned newspaper Israel Hayom. The charge: Fraud and breach of trust Netanyahu's defense: He had no intention of implementing the deal, and relations between politicians and the media should not be criminalized. |

|

Case 4000: As communication minister, Netanyahu took steps that benefited Shaul Elovitch who controlled telecom company Bezeq—in return for favorable coverage in Bezeq's Walla News site The charge: Bribery, fraud and breach of trust Netanyahu's defense: There is no evidence that he was aware of making regulations contingent on favorable coverage. |

|

Selected Steps in the Legal Process, and |

|

|

Sources: For "Indictments," the content comes from Ha'aretz graphics adapted by CRS. For "Selected Steps in the Legal Process, and the Time Between Them," CRS prepared the graphic and made slight content adjustments to underlying source material from Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre. The interval listed between Steps 4-5 is an estimate.

Appendix D. Maps Related to U.S. Plan

|

|

Source: White House, Peace to Prosperity: A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinian and Israeli People, January 2020. |

|

|

Source: White House, Peace to Prosperity: A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinian and Israeli People, January 2020. |

|

|

Notes: Green lines on map represent 1949-1967 Israel-Jordan armistice line (for West Bank) and 1950-1967 Israel-Egypt armistice line (for Gaza). All borders are approximate. |