Introduction

This report provides background information and issues for Congress on two types of amphibious ships being procured for the Navy: LPD-17 Flight II class amphibious ships and LHA-type amphibious assault ships. Both types are built by Huntington Ingalls Industries/Ingalls Shipbuilding (HII/Ingalls) of Pascagoula, MS.

The Navy's FY2021 budget submission poses multiple issues for Congress concerning these two types of ships, including potentially significant institutional issues regarding the preservation and use of Congress's power of the purse under Article 1 of the Constitution, and for maintaining Congress as a coequal branch of government relative to the executive branch. Congress's decisions on the LPD-17 Flight II and LHA programs could also affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements and the shipbuilding industrial base.

For an overview of the strategic and budgetary context in which amphibious ship and other Navy shipbuilding programs may be considered, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Background

Amphibious Ships in General

Roles and Missions

Navy amphibious ships are operated by the Navy, with crews consisting of Navy personnel. The primary function of Navy amphibious ships is to lift (i.e., transport) embarked U.S. Marines and their equipment and supplies to distant operating areas, and enable Marines to conduct expeditionary operations ashore in those areas. Although amphibious ships are designed to support Marine landings against opposing military forces, they are also used for operations in permissive or benign situations where there are no opposing forces. Due to their large storage spaces and their ability to use helicopters and landing craft to transfer people, equipment, and supplies from ship to shore without need for port facilities,1 amphibious ships are potentially useful for a range of combat and noncombat operations.2

On any given day, some of the Navy's amphibious ships, like some of the Navy's other ships, are forward-deployed to various overseas operating areas. Forward-deployed U.S. Navy amphibious ships are often organized into three-ship formations called amphibious ready groups (ARGs).3 On average, two or perhaps three ARGs might be forward-deployed at any given time. Amphibious ships are also sometimes forward-deployed on an individual basis to lower-threat operating areas, particularly for conducting peacetime engagement activities with foreign countries or for responding to smaller-scale or noncombat contingencies.

Types of Amphibious Ships

Navy amphibious ships can be divided into two main groups—the so-called "big-deck" amphibious assault ships, designated LHA and LHD, which look like medium-sized aircraft carriers, and the smaller (but still sizeable) amphibious ships designated LPD or LSD, which are sometimes called "small-deck" amphibious ships.4 The LHAs and LHDs have large flight decks and hangar decks for embarking and operating numerous helicopters and vertical or short takeoff and landing (V/STOL) fixed-wing aircraft, while the LSDs and LPDs have much smaller flight decks and hangar decks for embarking and operating smaller numbers of helicopters. The LHAs and LHDs, as bigger ships, in general can individually embark more Marines and equipment than the LSDs and LPDs.

Current Amphibious Force-Level Goal

The Navy's 355-ship force-level goal, released in December 2016, calls for achieving and maintaining a 38-ship amphibious force that includes 12 LHA/LHD-type ships, 13 LPD-17 class ships, and 13 LSD/LPD-type ships (12+13+13).5 The goal for achieving and maintaining a force of 38 amphibious ships relates primarily to meeting wartime needs for amphibious lift. Navy and Marine Corps officials have testified in the past that fully meeting U.S. regional combatant commander requests for day-to-day forward deployments of amphibious ships would require a force of 50 or more amphibious ships.6

Potential Change in Amphibious Force-Level Goal

Overview

The Navy's ship force-level goals, including its force-level goal for amphibious ships, are determined in a Navy analysis called a Force Structure Assessment (FSA). The Navy conducts a new FSA (or updates the most recent FSA) once every few years. The Navy recently completed a new FSA to succeed the one whose results were released in December 2016. Navy officials have stated that the new FSA is undergoing final review within DOD and may be released sometime during 2020.7 Statements from the Commandant of the Marine Corps suggest that the new FSA will change the Navy's amphibious ship force to an architecture based on a new amphibious lift target and a new mix of amphibious ships.

The current 38-ship amphibious ship force-level goal is intended to meet a requirement for having enough amphibious lift to lift the assault echelons of two Marine Expeditionary Brigades (MEBs), a requirement known as the 2.0 MEB lift requirement. The 2.0 MEB lift requirement dates to 2006. The translation of this lift requirement into a Marine Corps-preferred force-level goal of 38 ships dates to 2009, and the Navy's formal incorporation of the 38-ship goal (rather than a more fiscally constrained goal of 33 or 34 ships) into the Navy's overall ship force-structure goal dates to the 2016 FSA, the results of which were released in December 2016.8

In July 2019, General David H. Berger, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, released a document entitled Commandant's Planning Guidance that states that the Marine Corp wants to, among other things, move away from the 38-ship amphibious ship force-level goal and the 2.0 MEB lift force-planning metric, and shift to a new and different mix of amphibious ships that includes not only LHA/LHD-type amphibious assault ships and LPD/LPD-type amphibious ships, but other kinds of ships as well, including smaller amphibious ships, ships like the Navy's Expeditionary Sea Base (ESB) and Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF) ships, ships based on commercial-ship hull designs, and unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). The Commandant's Planning Guidance, which effectively announces a once-in-a-generation change in Marine Corps thinking on this and other issues relating to the Marine Corps, states in part (emphasis as in the original):

Our Nation's ability to project power and influence beyond its shores is increasingly challenged by long-range precision fires; expanding air, surface, and subsurface threats; and the continued degradation of our amphibious and auxiliary ship readiness. The ability to project and maneuver from strategic distances will likely be detected and contested from the point of embarkation during a major contingency. Our naval expeditionary forces must possess a variety of deployment options, including L-class [amphibious ships] and E-class [expeditionary ships] ships, but also increasingly look to other available options such as unmanned platforms, stern landing vessels, other ocean-going connectors, and smaller more lethal and more risk-worthy platforms. We must continue to seek the affordable and plentiful at the expense of the exquisite and few when conceiving of the future amphibious portion of the fleet.

We must also explore new options, such as inter-theater connectors and commercially available ships and craft that are smaller and less expensive, thereby increasing the affordability and allowing acquisition at a greater quantity. We recognize that we must distribute our forces ashore given the growth of adversary precision strike capabilities, so it would be illogical to continue to concentrate our forces on a few large ships. The adversary will quickly recognize that striking while concentrated (aboard ship) is the preferred option. We need to change this calculus with a new fleet design of smaller, more lethal, and more risk-worthy platforms. We must be fully integrated with the Navy to develop a vision and a new fleet architecture that can be successful against our peer adversaries while also maintaining affordability. To achieve this difficult task, the Navy and Marine Corps must ensure larger surface combatants possess mission agility across sea control, littoral, and amphibious operations, while we concurrently expand the quantity of more specialized manned and unmanned platforms….

We will no longer use a "2.0 MEB requirement" as the foundation for our arguments regarding amphibious ship building, to determine the requisite capacity of vehicles or other capabilities, or as pertains to the Maritime Prepositioning Force. We will no longer reference the 38-ship requirement memo from 2009, or the 2016 Force Structure Assessment, as the basis for our arguments and force structure CRS Report RL34476, Navy LPD-17 Amphibious Ship Procurement: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourkejustifications. The ongoing 2019 Force Structure Assessment will inform the amphibious requirements based upon this guidance. The global options for amphibs [types of amphibious ships] include many more options than simply LHAs, LPDs, and LSDs. I will work closely with the Secretary of the Navy and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) to ensure there are adequate numbers of the right types of ships, with the right capabilities, to meet national requirements.

I do not believe joint forcible entry operations (JFEO) are irrelevant or an operational anachronism; however, we must acknowledge that different approaches are required given the proliferation of anti-access/area denial (A2AD) threat capabilities in mutually contested spaces. Visions of a massed naval armada nine nautical miles off-shore in the South China Sea preparing to launch the landing force in swarms of ACVs [amphibious combat vehicles], LCUs [utility landing craft], and LCACs [air-cushioned landing craft]are impractical and unreasonable. We must accept the realities created by the proliferation of precision long-range fires, mines, and other smart-weapons, and seek innovative ways to overcome those threat capabilities. I encourage experimentation with lethal long-range unmanned systems capable of traveling 200 nautical miles, penetrating into the adversary enemy threat ring, and crossing the shoreline—causing the adversary to allocate resources to eliminate the threat, create dilemmas, and further create opportunities for fleet maneuver. We cannot wait to identify solutions to our mine countermeasure needs, and must make this a priority for our future force development efforts….

Over the coming months, we will release a new concept in support of the Navy's Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) Concept and the NDS called – Stand-in Forces. The Stand-in Forces concept is designed to restore the strategic initiative to naval forces and empower our allies and partners to successfully confront regional hegemons that infringe on their territorial boundaries and interests. Stand-in Forces are designed to generate technically disruptive, tactical stand-in engagements that confront aggressor naval forces with an array of low signature, affordable, and risk-worthy platforms and payloads. Stand-in forces take advantage of the relative strength of the contemporary defense and rapidly-emerging new technologies to create an integrated maritime defense that is optimized to operate in close and confined seas in defiance of adversary long-range precision "stand-off capabilities."

Creating new capabilities that intentionally initiate stand-in engagements is a disruptive "button hook" in force development that runs counter to the action that our adversaries anticipate. Rather than heavily investing in expensive and exquisite capabilities that regional aggressors have optimized their forces to target, naval forces will persist forward with many smaller, low signature, affordable platforms that can economically host a dense array of lethal and nonlethal payloads.

By exploiting the technical revolution in autonomy, advanced manufacturing, and artificial intelligence, the naval forces can create many new risk-worthy unmanned and minimally-manned platforms that can be employed in stand-in engagements to create tactical dilemmas that adversaries will confront when attacking our allies and forces forward.9

Potential New Light Amphibious Warship (LAW) Program

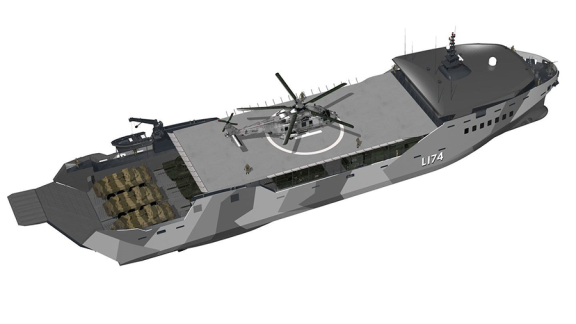

As one possible reflection of the potential change in the amphibious force-level goal discussed above, a February 20, 2020, press report about a potential new type of stern-landing amphibious ship called the Light Amphibious Warship (LAW) (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3) states

The Navy's research and development portfolio will devote $30 million to a "next-generation medium amphibious ship design" that will likely be based on an Australian designer's stern landing vessel….

The Navy and Marines announced in the Fiscal Year 2021 budget request that they will seek a medium amphibious ship that can support the kind of dispersed, agile, constantly relocating force described in the Littoral Operations in Contested Environment (LOCE) and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concepts the Marine Corps has written, as well as the overarching Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) from the Navy. According to a budget overview document, "a next-generation medium amphibious ship will be a stern landing vessel to support amphibious ship-to-shore operations."

"FY 2021 funds support concept evaluation/design, industry studies and exploration for a medium-lift intra-theater amphibious support vessel. Efforts include requirements development, systems engineering, naval architecture and marine engineering, and operations research analysis," reads a justification book that accompanies the budget request.

The Navy and Marines had previously cited the Offshore Support Vessel as a possible inspiration for their new design….

However, since that time, Marine Corps planners took another look at the features they'd need on this medium amphibious ship, rather than limiting their talks to existing ship designs, USNI News understands. Those talks led to a realization that they not only wanted a ship that could move Marines around with some range, but they also wanted the ship to be able to beach itself like a landing craft does, to help offload gear and vehicles as needed. These talks led to a new focus on the stern landing vessel designed by Australian company Sea Transport, which could serve as the new inspiration for the medium amphibious vehicle as requirements development and EABO wargaming and simulations take place….

The Navy and Marines are not committed yet to this design or to Sea Transport, but USNI News understands that something like a SLV would combine a surface ship's ability to have great enough endurance and range to be operationally useful to commanders and a landing craft's ability to beach itself to offload larger equipment.10

A March 26, 2020, press report stated:

The Navy is asking industry for input on a future Light Amphibious Warship, as the Marine Corps recalculates its force design to prepare for a near-peer fight in the Pacific.

A recent request for information says the Navy will hold a virtual industry day on April 9….

The Navy anticipates purchasing the first ships in fiscal year 2023, according to slides from the March 4 industry day. A preliminary schedule anticipates the service buying three vessels in FY-23, six in FY-24, 10 in FY-25 and nine in FY-26. The Navy also envisions utilizing a commercial design that it could alter for the military.11

A May 5, 2020, press report stated:

The U.S. Navy wants to buy as many as 30 of a new class of Light Amphibious Warships that would be significantly smaller and cheaper to operate than its existing fleets of large amphibious ships. The service is already exploring possible designs, including a roll-on-roll-off type with a stern ramp.…

Navy officials… said that the "objective number" of Light Amphibious Warships (LAW) it hopes to buy is between 28 and 30 at a briefing for defense industry representatives on Apr. 9, 2020….

The Navy is still in an information-gathering phase, but does already have some key requirements for any potential LAW design, which it expects to be about 200 feet long overall and have 8,000 square feet of cargo space in total. Each LAW will have a crew of no more than 40 sailors and be able to accommodate at least 75 Marines….

The Navy says that it is willing to consider either adapting an existing commercial design, using a commercial hullform as a starting place, or a so-called "Build to Print" ship based on proven design elements and components. The goal in all of these courses of action is to focus on relatively low-risk, low-cost, mature designs, or at least design features, in order to both keep the ships cheap and make them faster and easier to build. The Navy has said it is interested in awarding at least one preliminary design contract by the end of this year with the hope that it could begin buying actual ships as early as late 2022.

The service has also indicated that it might be willing to accept ship designs with relatively short expected service lives in order to help keep production costs low and speed up construction. The requirements now say that the LAWs have to have a life span of just 10 years, at a minimum.12

Current and Projected Force Levels

The Navy's force of amphibious ships at the end of FY2019 included 32 ships, including 9 amphibious assault ships (1 LHA and 8 LHDs), 11 LPD-17 Flight I ships, and 12 LSD-41/49 class ships. The LSD-41/49 class ships, which are the ships to be replaced by LPD-17 Flight II ships, are discussed in the next section.

The Navy's FY2020 30-year (FY2020-FY2049) shipbuilding plan projects that the Navy's force of amphibious ships will increase gradually to 38 ships by FY2026, remain at a total of 36 to 38 ships in FY2027 to FY2034, decline to 34 or 35 ships in FY2035-FY2038, increase to 36 or 37 ships in FY2039-FY2046, and remain at 35 ships in FY2047-FY2049. Over the entire 30-year period, the force is projected to include an average of about 35.8 ships, or about 94% of the required figure of 38 ships, although the resulting amount of lift capability provided by the ships would not necessarily equate to about 94% of the amphibious lift goal, due to the mix of ships in service at any given moment and their individual lift capabilities.

Existing LSD-41/49 Class Ships

The Navy's 12 aging Whidbey Island/Harpers Ferry (LSD-41/49) class ships (Figure 4) were procured between FY1981 and FY1993 and entered service between 1985 and 1998.13 The class includes 12 ships because they were built at a time when the Navy was planning a 36-ship (12+12+12) amphibious force. They have an expected service life of 40 years; the first ship will reach that age in 2025. The Navy's FY2020 30-year shipbuilding plan projects that the 12 ships will retire between FY2026 and FY2038.

Amphibious Warship Industrial Base

Huntington Ingalls Industries/Ingalls Shipbuilding (HII/Ingalls) of Pascagoula, MS, is the Navy's current builder of both LPDs and LHA-type ships, although other U.S. shipyards could also build amphibious ships.14 The amphibious warship industrial base also includes many supplier firms in numerous U.S. states that provide materials and components for Navy amphibious ships. HII states that the supplier base for its LHA production line, for example, includes 457 companies in 39 states.15

|

|

Source: U.S. Navy photo accessed May 7, 2014, at http://www.navy.mil/gallery_search_results.asp?terms=lsd+52&page=4&r=4. The Navy's caption for the photo states that the photo is dated July 13, 2013, and that it shows the Pearl Harbor (LSD-52) anchored off Majuro atoll in the Republic of the Marshall Islands during an exercise called Pacific Partnership 2013. |

LPD-17 Flight II Program

Program Name

The Navy decided in 2014 that the LSD-41/49 replacement ships would be built to a variant of the design of the Navy's San Antonio (LPD-17) class amphibious ships. (A total of 13 LPD-17 class ships [LPDs 17 through 29] were procured between FY1996 and FY2017.) Reflecting that decision, the Navy announced on April 10, 2018, that the replacement ships would be known as the LPD-17 Flight II ships.16 By implication, the Navy's original LPD-17 design became the LPD-17 Flight I design. The first LPD-17 Flight II ship is designated LPD-30. Subsequent LPD-17 Flight II ships are to be designated LPD-31, LPD-32, and so on.

Whether the LPD-17 Flight II ships constitute their own shipbuilding program or an extension of the original LPD-17 shipbuilding program might be a matter of perspective. As a matter of convenience, this CRS report refers to the Flight II shipbuilding effort as a separate program. Years from now, LPD-17 Flight I and Flight II ships might come to be known collectively as either the LPD-17 class, the LPD-17/30 class, or the LPD-17 and LPD-30 classes.

On October 10, 2019, the Navy announced that LPD-30, the first LPD-17 Flight II ship, will be named Harrisburg, for the city of Harrisburg, PA.17 As a consequence, LPD-17 Flight II, if treated as a separate class, would be referred to as Harrisburg (LPD-30) class ships.

Design

Compared to the LPD-17 Flight I design, the LPD-17 Flight II design (Figure 5) is somewhat less expensive to procure, and in some ways less capable—a reflection of how the Flight II design was developed to meet Navy and Marine Corps operational requirements while staying within a unit procurement cost target that had been established for the program.18 In many other respects, however, the LPD-17 Flight II design is similar in appearance and capabilities to the LPD-17 Flight I design. Of the 13 LPD-17 Flight I ships, the final two (LPDs 28 and 29) incorporate some design changes that make them transitional ships between the Flight I design and the Flight II design.

Procurement Quantity

Consistent with the Navy's 38-ship amphibious force-level goal, the Navy wants to procure a total of 13 LPD-17 Flight II ships.

Procurement Schedule

Overview

The Navy's FY2021 budget submission presents the second LPD-17 Flight II amphibious ship, LPD-31, as a ship requested for procurement in FY2021. Consistent with congressional action on the Navy's FY2020 budget, this CRS report treats LPD-31 as a ship that Congress procured (i.e., authorized and provided procurement—not advance procurement—funding for) in FY2020. (For additional discussion, see the Appendix.)19 Under the Navy's FY2021 budget submission, the third and fourth LPD-17 Flight II class ships (i.e., LPDs 32 and 33) are programmed for procurement in FY2023 and FY2025.

|

Figure 5. LPD-17 Flight II Design Artist's rendering |

|

|

Source: Huntington Ingalls Industries rendering accessed April 22, 2019, at https://www.huntingtoningalls.com/lpd-flight-ii/. |

Procurement Cost

The Navy's FY2021 budget submission estimates the procurement costs of LPDs 30, 31, 32, and 33 as $1,819.6 million, $2,029.9 million, $1,847.6 million, and $1,864.7 million, respectively (i.e., about $1.8 billion, $2,0 billion, $1.8 billion, and $1.9 billion, respectively).

LHA-9 Amphibious Assault Ship

LHA-type amphibious assault ships are procured once every few years. LHA-8 (Figure 6) was procured in FY2017; the Navy's FY2021 budget submission estimates its cost at $3,832.0 million (i.e., about $3.8 billion).

The Navy's FY2020 budget submission projected the procurement of the next amphibious assault ship, LHA-9, for FY2024. Some in Congress have been interested in accelerating the procurement of LHA-9 from FY2024 to an earlier year, such as FY2020 or FY2021, in part to achieve better production learning curve benefits in shifting from production of LHA-8 to LHA-9 and thereby reduce LHA-9's procurement cost in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms. As part of its action on the Navy's proposed FY2019 budget, Congress provided $350 million in unrequested advance procurement (AP) funding for LHA-9, in part to encourage the Navy to accelerate the procurement of LHA-9 from FY2024 to an earlier fiscal year, such as FY2020 or FY2021. As part of its action on the Navy's proposed FY2020 budget, Congress provided an additional $650 million in procurement (not AP) funding for the ship, and included a provision (Section 127) in the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1790/P.L. 116-92 of December 20, 2019) that authorizes the Navy to enter into a contract for the procurement of LHA-9 and to use incremental funding provided during the period FY2019-FY2025 to fund the contract.

The Navy's FY2021 budget submission presents LHA-9 as a ship projected for procurement in FY2023. Consistent with the above-noted congressional action on the Navy's FY2020 budget, this CRS report treats LHA-9 as a ship that Congress procured (i.e., authorized and provided procurement—not advance procurement—funding for) in FY2020. (For additional discussion, see Appendix.)20

The Navy's FY2021 budget submission estimates the procurement cost of LHA-9, if procured in FY2023, at $3,873.5 million (i.e., about $3.9 billion). The Navy's FY2021 budget submission, which the Navy submitted to Congress on February 10, acknowledges the $350 million in FY2019 advanced procurement (AP) funding and $650 million in FY2020 procurement funding that Congress provided for the ship, but does not program any further funding for the ship until FY2023.

On February 13, the Administration submitted a reprogramming action that transfers about $3.8 billion in DOD funding to Department of Homeland Security (DHS) counter-drug activities, commonly reported to mean the construction of the southern border wall. Included in this action is the $650 million that Congress appropriated in FY2020 for LHA-9.21 The reprogramming action acknowledges that LHA-9 is a congressional special interest item, meaning one that Congress funded at a level above what DOD had requested. (The Navy's FY2020 budget submission requested no funding for the ship.) The reprogramming action characterizes the $650 million as "early to current programmatic need," even though it would be needed for a ship whose construction would begin in FY2020. In discussing its FY2021 budget submission, Navy officials characterize LHA-9 not as ship whose procurement the Navy is proposing to delay from FY2020 to FY2023, but as a ship whose procurement the Navy is proposing to accelerate from FY2024 (the ship's procurement date under the Navy's FY2020 budget submission) to FY2023.

Issues for Congress

Potential Impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Situation

One issue for Congress concerns the potential impact of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) situation on the execution of U.S. military shipbuilding programs, including the LPD-17 Flight II and LHA programs. For additional discussion of this issue, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Procurement Dates of LPD-31 and LHA-9, and Congress's Power of the Purse

A potentially significant institutional issue for Congress concerns the treatment in the Navy's proposed FY2021 budget of the procurement dates of LPD-31 and LHA-9. As discussed earlier, the Navy's FY2021 budget submission presents LPD-31 as a ship requested for procurement in FY2021 and LHA-9 as a ship projected for procurement in FY2023. Consistent with congressional action on the Navy's FY2020 budget regarding the procurement of LPD-31 and LHA-9 (see the Appendix), this CRS report treats LPD-31 and LHA-9 as ships that Congress procured (i.e., authorized and provided procurement funding for) in FY2020. Potential oversight issues for Congress include the following:

- By presenting LPD-31 as a ship requested for procurement in FY2021 (instead of a ship that was procured in FY2020) and LHA-9 as a ship projected for procurement in FY2023 (instead of a ship that was procured in FY2020), is DOD, in its FY2021 budget submission, disregarding or mischaracterizing the actions of Congress regarding the procurement dates of these three ships? If so:

- Is DOD doing this to inflate the apparent number of ships requested for procurement in FY2021 and the apparent number of ships included in the five-year (FY2021-FY2025) shipbuilding plan?

- Could this establish a precedent for DOD or other parts of the executive branch in the future to disregard or mischaracterize the actions of Congress regarding the procurement or program-initiation dates for other Navy ships, other Navy programs, other DOD programs, or other federal programs? If so, what implications might that have for the preservation and use of Congress's power of the purse under Article 1 of the Constitution, and for maintaining Congress as a coequal branch of government relative to the executive branch?

Reprogramming of $650 Million for LHA-9 and Congress's Power of the Purse

Another potentially significant institutional issue for Congress concerns the Administration's reprogramming of $650 million in FY2020 procurement funding for LHA-9 to DHS counter-drug activities, commonly reported to mean the construction of the southern border wall, even though the reprogramming action acknowledges that LHA-9 is a congressional special interest item, meaning one that Congress funded at a level above what DOD had requested. As discussed earlier, some in Congress have been interested in accelerating the procurement of LHA-9 from FY2024 to an earlier year, such as FY2020 or FY2021, and Congress has provided funding in both FY2019 and FY2020 in support of that goal. Potential oversight issues for Congress include the following:

- By reprogramming this funding to another purpose, is DOD, in its FY2021 budget submission, disregarding the expressed intent of Congress regarding the procurement of LHA-9?

- If so, could this establish a precedent for DOD or other parts of the executive branch in the future to disregard the intent of Congress regarding the procurement or program-initiation dates for other Navy ships, other Navy programs, other DOD programs, or other federal programs? What implications might that have for the preservation and use of Congress's power of the purse under Article 1 of the Constitution, and for maintaining Congress as a coequal branch of government relative to the executive branch?

Potential Change in Required Number of LPD-17 Flight II and LHA-Type Ships

Another potential issue for Congress is whether the Navy's next FSA will change the required number of LPD-17 Flight II and LHA-type amphibious ships, and if so, whether that might change Navy plans for procuring these ships in future fiscal years. As discussed earlier, statements from the Commandant of the Marine Corps suggest that the new FSA that is to be completed by the end of 2019 might change the Navy's amphibious ship force to an architecture based on a new amphibious lift target and a new mix of amphibious ships.

Technical and Cost Risk in LPD-17 Flight II and LHA Programs

Another potential issue for Congress is technical and cost risk in the LPD-17 Flight II and LHA programs.

Technical Risk

Regarding technical risk in the LPD-17 Flight II program, a May 2019 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report—the 2019 edition of GAO's annual report surveying DOD major acquisition programs—states the following about the LPD-17 Flight II program:

Current Status

The Navy planned to accelerate purchase of LPD 30—the first fully configured Flight II ship—after Congress appropriated $1.8 billion above the fiscal year 2018 budget request, according to program officials. The Navy reported that it awarded contracts in August 2018 for LPD 30 long lead time materials and in March 2019 for lead ship construction.

The Navy based the Flight II design on Flight I, with modifications to reduce costs and meet new requirements. According to program officials, roughly 200 design changes will distinguish the two flights including replacing the composite mast with a steel stick. Officials stated that the design would not rely on any new technologies. However, the Navy plans to install a new radar, the Enterprise Air Surveillance Radar, which is still in development. The Navy expects live radar system testing through November 2019, with a complete radar prototype in February 2020. Although program officials consider these activities to be low risk, the Navy will make its decision to begin ship construction by December 2019 without incorporating lessons learned from radar testing into the design. Starting construction before stabilizing the design could require the Navy to absorb costly design changes and rework during ship construction.

The Navy initially pursued a limited competition for LX(R), but now has a non-competitive acquisition strategy for LPD 17 Flight II. The Navy plans to award sole-source contracts to Huntington Ingalls—the only shipbuilder of Flight I ships—for Flight II construction. Further, the program did not request a separate independent cost estimate for Flight II prior to awarding the LPD 30 detail design and construction contract. At the same time, the Navy identified no plans to establish a cost baseline specific to Flight II. Without this baseline, the Navy would report full LPD 17 program costs—rather than Flight II specific costs—constraining visibility into Flight II.

Program Office Comments

We provided a draft of this assessment to the program office for review and comment. The program office provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate The program office stated that LPD Flight II is included under the existing LPD 17 acquisition program baseline, and that no other viable contractor responded to a public notice regarding the Navy's plan to award Huntington Ingalls the LPD 30 construction contract.22

Regarding technical risk in the LHA program, the May 2019 GAO report stated the following about the LHA program:

Current Status

In June 2017, the Navy exercised a contract option for detail design and construction of the LHA 8. The LHA 8 incorporates significant design changes from earlier ships in the LHA 6 class, but Navy officials were unable to quantify the changes. The Navy started construction in October 2018 and LHA 8 is scheduled to be delivered in January 2024.

The LHA 8 program office has not identified any critical technologies. However, the ship is relying on technology that is currently being developed by another Navy program, the Enterprise Air Surveillance Radar (EASR), with delivery expected in August 2021. EASR, intended to provide self-defense and situational awareness capabilities, is derived from the pre-existing Air and Missile Defense Radar program, but will be a different size and will rotate. LHA 8 program officials have identified the radar as the program's highest development risk. If the radar is not delivered on schedule, Navy officials report that this could lead to out-of-sequence design and delayed installation and testing. Officials responsible for developing the radar, however, stated that the radar is approaching maturity and is on schedule to be delivered to the shipbuilder when needed.

The Navy began construction with about 61 percent of the LHA 8 product model completed—an approach inconsistent with shipbuilding best practices. These best practices call for 100 percent completion of 3D product modeling prior to construction start to minimize the likelihood of costly re-work and out of sequence work that can drive schedule delays. The Navy, however, estimates that the LHA 8 shipbuilder will not complete 100 percent of the ship's 3D product model until June 2019, almost 8 months after the start of construction.

Program Office Comments

We provided a draft of this assessment to the program office for review and comment. The program office provided technical comments, which we incorporated where appropriate. The program office stated that the Navy understands all design changes incorporated on the LHA 8, such as reintroducing the well deck and incorporating EASR. According to the program office, the Navy does not begin construction on any section of the LHA 8 ship before completing that respective section's design.23

Cost Risk

Regarding cost risk in the LPD-17 Flight II program, an October 2019 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on the cost of the Navy's shipbuilding programs states the following:

The Navy estimates that the LPD-17 Flight IIs would cost $1.6 billion each, on average, and that the lead ship would cost $1.7 billion to $1.8 billion.… To achieve its cost goal for the LPD-17 Flight II, the Navy plans to further alter the LPD-17 design and, perhaps, to change the way it buys them: The Flight II variant would have substantially less capability than the LPD-17 class, and the Navy might use block-buy or multiyear authority to purchase the ships, although it has not yet stated an intention to do so. Such authority would commit the government to buying a group of ships over several years, thereby realizing savings as a result of the predictable and steady work provided to the construction shipyard and to the vendors that provide parts and components to the shipbuilder. The authority would be similar to that provided for the Arleigh Burke class destroyers, Virginia class attack submarines, and LCSs [Littoral Combat Ships].

CBO estimates that the LPD-17 Flight II class would cost an average of $1.9 billion per ship. The agency [CBO] used the existing LPD-17 hull as the starting point for its estimate and then adjusted the ship's size to reflect the reduced capability it expects for the Flight II. CBO's estimate reflects the assumption that the Navy would ultimately use multiyear or block-buy procurement authority to purchase the ships.24

Regarding cost risk in the LHA program, the October 2019 CBO report states the following:

The Navy estimates that the LHA-6 class amphibious assault ships would cost $3.4 billion each …. Under the 2020 plan, a seven-year gap separates the last LHA-6 class ship ordered in 2017 and the next one, slated to be purchased in 2024, which in CBO's estimation would effectively eliminate any manufacturing learning gleaned from building the first 3 ships of the class. As a result, CBO's estimate is higher than the Navy's, at $3.9 billion per ship.25

Legislative Activity for FY2021

Summary of Congressional Action on FY2021 Funding Request

Table 1 summarizes congressional action on the Navy's FY2021 funding request for LPD-31 and LHA-9.

Table 1. Summary of Congressional Action on FY2021 Procurement Funding Request

Millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth

|

Request |

Authorization |

Appropriation |

|||||

|

HASC |

SASC |

Conf. |

HAC |

SAC |

Conf. |

||

|

LPD-31 |

1,155.8 |

||||||

|

LHA-9 |

0 |

||||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy's FY2021 budget submission, committee and conference reports, and explanatory statements on FY2021 National Defense Authorization Act and FY2021 DOD Appropriations Act.

Notes: HASC is House Armed Services Committee; SASC is Senate Armed Services Committee; HAC is House Appropriations Committee; SAC is Senate Appropriations Committee; Conf. is conference agreement.

Appendix. Procurement Dates of LPD-31 and LHA-9

This appendix presents background information on congressional action regarding the procurement dates of LPD-31 and LHA-9. In reviewing the bullet points presented below, it can be noted that procurement funding is funding for a ship that is either being procured in that fiscal year or has been procured in a prior fiscal year, while advance procurement (AP) funding is funding for a ship that is to be procured in a future fiscal year.26

LPD-31—an LPD-17 Flight II Amphibious Ship

The Navy's FY2021 budget submission presents LPD-31, an LPD-17 Flight II amphibious ship, as a ship requested for procurement in FY2021. This CRS report treats LPD-31 as a ship that Congress procured (i.e., authorized and provided procurement funding for) in FY2020, consistent with the following congressional action on the Navy's FY2020 budget regarding the procurement of LPD-31:

- The House Armed Services Committee's report (H.Rept. 116-120 of June 19, 2019) on H.R. 2500, the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act, recommended authorizing the procurement of an LPD-17 Flight II ship in FY2020, showing a quantity increase of one ship above the Navy's request and recommending procurement (not just AP) funding for the program.27

- The Senate Armed Services Committee's report (S.Rept. 116-48 of June 11, 2019) on S. 1790, the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act, recommended authorizing the procurement of an LPD-17 Flight II ship in FY2020, showing a quantity increase of one ship above the Navy's request and recommending procurement (rather than AP) funding for the program.28

- The conference report (H.Rept. 116-333 of December 9, 2019) on S. 1790/P.L. 116-92 of December 20, 2019, the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act, authorized the procurement of an LPD-17 Flight II ship in FY2020, showing a quantity increase of one ship above the Navy's request and recommending procurement (rather than AP) funding for the program.29 Section 129 of S. 1790/P.L. 116-92 authorizes the Navy to enter into a contract, beginning in FY2020, for the procurement of LPD-31, and to use incremental funding to fund the contract.

- The Senate Appropriations Committee's report (S.Rept. 116-103 of September 12, 2019) on S. 2474, the FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act, recommended funding for the procurement of an LPD-17 Flight II ship in FY2020, showing a quantity increase of one ship above the Navy's request and recommending procurement (rather than AP) funding for the program.30

- The final version of the FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act (Division A of H.R. 1158/P.L. 116-93 of December 20, 2019) provides procurement (not AP) funding for an LPD-17 Flight II ship. The paragraph in this act that appropriates funding for the Navy's shipbuilding account, including this ship, includes a provision stating "Provided further, That an appropriation made under the heading 'Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy' provided for the purpose of 'Program increase—advance procurement for fiscal year 2020 LPD Flight II and/or multiyear procurement economic order quantity' shall be considered to be for the purpose of 'Program increase—advance procurement of LPD–31'." This provision relates to funding appropriated in the FY2019 DOD Appropriations Act (Division A of H.R. 6157/P.L. 115-245 of September 28, 2018) for the procurement of an LPD-17 Flight II ship in FY2020, as originally characterized in the explanatory statement accompanying that act.31

LHA-9 Amphibious Assault Ship

The Navy's FY2021 budget submission presents the amphibious assault ship LHA-9 as a ship projected for procurement in FY2023. This CRS report treats LHA-9 as a ship that Congress procured (i.e., authorized and provided procurement funding for) in FY2020, consistent with the following congressional action on the Navy's FY2020 budget regarding the procurement of LHA-9:

- The Senate Armed Services Committee's report (S.Rept. 116-48 of June 11, 2019) on S. 1790, the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act, recommended authorizing the procurement of LHA-9 in FY2020, showing a quantity increase of one ship above the Navy's request and recommending procurement (rather than AP) funding for the program.32

- The conference report (H.Rept. 116-333 of December 9, 2019) on S. 1790/P.L. 116-92 of December 20, 2019, the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act, authorized the procurement of LHA-9 in FY2020, showing a quantity increase of one ship above the Navy's request and recommending procurement (rather than AP) funding for the program.33 Section 127 of S. 1790/P.L. 116-92 authorizes the Navy to enter into a contract for the procurement of LHA-9 and to use incremental funding provided during the period FY2019-FY2025 to fund the contract.

- The Senate Appropriations Committee's report (S.Rept. 116-103 of September 12, 2019) on S. 2474, the FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act, recommended funding for the procurement of an LHA amphibious assault ship in FY2020, showing a quantity increase of one ship above the Navy's request and recommending procurement (rather than AP) funding for the program.34

- The final version of the FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act (Division A of H.R. 1158/P.L. 116-93 of December 20, 2019) provides procurement (not AP) funding for an LHA amphibious assault ship. The explanatory statement for Division A of H.R. 1158/P.L. 116-93 states that the funding is for LHA-9.35