Overview

The United States has not used conscription to fill manpower requirements for over four decades; however, the Selective Service System and the requirement for young men to register for the draft remain today. Men who fail to register are subject to penalties in the form of lost benefits and criminal action. Some have questioned the need to maintain this agency and the registration requirements. Others have questioned whether the current requirements for registration are fair and equitable.

This report provides Congress with information about how the Military Selective Service Act (MSSA), the Selective Service System (SSS), and associated requirements for registration have evolved over time. It explains why the United States developed the SSS, what the system looks like today, how constituents are affected by the MSSA requirements, and what the options and considerations may be for the future of the Selective Service.

The first section of the report provides background and history on the Military Selective Service Act, the Selective Service System, and the implementation of the draft in the United States. The second section discusses statutory registration requirements, processes for registering, and penalties for failing to register. The third section discusses the current organization, roles, and resourcing of the Selective Service System. The final section discusses policy options and consideration for Congress for the future of the MSSA and the Selective Service System.

This report does not discuss the state of the all-volunteer force or whether it is adequate to meet the nation's current or future manpower needs. In addition, it does not provide an analysis of other options for military manpower resourcing such as universal military service or universal military training. Finally, this report does not evaluate whether the SSS, as currently structured, is adequately resourced and organized to perform its statutory mission. These questions and others were reviewed by the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service established by the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2017 (P.L. 114-328). The commission released its final report on March 26, 2020 and a brief discussion of its findings with relation to the SSS are included in this report.

Background

The United States has used federal conscription at various times since the Civil War era, primarily in times of war, but also during peacetime in the aftermath of World War II. When first adopted in 1863, national conscription was a marked departure from the traditional military policy of the United States, which from the founding era had relied on a small volunteer force that could be augmented by state militias in times of conflict. Conscription was used as a mechanism to provide military manpower during times of need until the adoption of the all-volunteer force (AVF) in 1973. At this time, authority to induct new draftees under the Military Selective Service Act ceased.1 Nevertheless, a standby draft mechanism still exists to furnish manpower above and beyond that provided by the active and reserve components of the Armed Forces in the case of a major military contingency. If the federal government were to reinstate the draft, draftees would likely be required to fill all authorized positions to include casualty replacements, billets in understrength units, and new military units activated to expand the wartime force.

1863 Enrollment Act and Civil War Conscription

During the Civil War, due to high demand for military manpower, weaknesses in the system for calling up state militia units, and an insufficient number of volunteers for active federal service, President Abraham Lincoln signed the 1863 Enrollment Act.2 This marked the first instance of the federal government calling individuals into compulsory federal service through conscription.3 All male citizens between the ages of 20 and 45 who were capable of bearing arms were liable to be drafted. The law allowed exemptions for dependency and employment in official positions. The Enrollment Act also established a national Provost Marshal Bureau, led by a provost marshal general and was responsible for enforcing the draft.4 Under the act, the President had authority to establish enrollment districts and to appoint a provost marshal to each district to serve under the direction of the Secretary of War in a separate bureau under the War Department. The provost marshal general was responsible for establishing a district board for processing enrollments and was given authority under the law to make rules and regulations for the operation of the boards and to arrest draft dodgers and deserters. Government agents went door-to-door to enroll individuals, followed by a lottery in each congressional district based on district quotas.5

Some observers criticized the Enrollment Act as favoring the wealthiest citizens, because it allowed for either the purchase of a substitute who would serve in the draftee's place or payment by the draftee of a fee up to $300.6 In addition, volunteers were offered bounties by both the federal government and some local communities. Under this system, fraud and desertions were common.7 Enforcement of the draft also incited rioting and violence in many cities across the United States, most famously in New York City. On July 13, 1863, the intended date of the second draft drawing in New York City, an angry mob attacked the assistant Ninth District provost marshal's office, smashing the lottery selection wheel and setting the building on fire.8 Several days of rioting and violence ensued until federal troops were called in to restore order. The draft call was suspended in New York City during the rioting and was not resumed until August 19, 1863.

The total number of men that served in the Union forces during the course of the war was 2,690,401. The number drafted was 255,373. Of the total draftees, 86,724 avoided military service by the payment of commutation, and 117,986 furnished substitutes.9 Volunteerism during this war was likely driven in part by the bounty system.

Selective Service Act of 1917 and World War I Conscription

After the Civil War, the federal government did not use conscription again until World War I (WWI). By then a new concept for a draft system termed "Selective Service" had been developed that would apportion requirements for manpower to the states and through the states to individual counties.10 By 1915, Europe was in all-out war; the United States had a small volunteer Army of approximately 100,000 men. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war, and on May 18, 1917, he signed an act commonly known as the Selective Service Act of 1917 into law.11 This new law allowed the President to draft the National Guard into federal service (rather than calling the militia into federal service) and made all male citizens between the ages of 21 and 31 liable for the draft.12 On July 15, 1917, Congress enacted a provision that all conscripted persons would be released from compulsory service within four months of a presidential proclamation of peace.13 In 1918, Congress extended the eligible draft age to include all males between the ages of 18 and 45. World War I was the first instance of conscription of United States citizens for overseas service.

A key aspect of the Selective Service Act of 1917 was that it allowed the federal government to select individuals from a pool of registrants for federal service. Unlike the Civil War, a shortage of volunteers was not the primary concern in enacting this legislation. The selective aspects of the WWI draft law were driven by concerns that indiscriminate volunteerism could adversely affect the domestic economy and industrial base. In support of the selective service law, Senator William M. Calder of New York said, "under a volunteer system, there is no way of preventing men from leaving industries and crippling resources that are just as important as the army itself."14

In contrast to the Civil War draft, the Selective Service Act of 1917 did not allow for the furnishing of substitutes or bounties for enlistment. It also provided for decentralized administration through local and district draft boards that were responsible for registering and classifying men, and calling registrants into service.15 The law specified that the President would appoint boards consisting of civilian members "not connected with the Military Establishment." Over 4,600 such boards were established to hear and decide on claims for exemptions.16 The provost marshal general, at the time Major General Enoch Crowder, oversaw the operation of these boards.

The first draft lottery was held on July 20, 1917.17 Out of the 24.2 million that registered for the draft in WWI, 2.8 million were eventually inducted. While the law did not prohibit volunteers, the implementation of the selective service system alongside a volunteer system became too complex and the Army discontinued accepting volunteer enlistees by December 15, 1917.18 By 1919, at the end of the war, the provost marshal general was relieved from his duties, all registration activities were terminated, and all local and district boards were closed. In 1936, the Secretaries of War and the Navy created the Joint Army-Navy Selective Service Committee to manage emergency mobilization planning.19 The committee was headed by Army Major Lewis B. Hershey.

Between WWI and WWII, the Armed Forces shrank in numbers due to both treaty commitments and public attitudes toward a large standing force. In the interwar period, two opposing movements emerged. Some were in support of legislative provisions that would empower the President to conscript men for military service upon a declaration of war, and some called for a universal draft, universal military training, or broader authorities to conscript civilian labor in times of both war and peace.20 Others proposed provisions that would require a national referendum on any future use of conscription, or would forbid conscripts from serving outside the territorial borders of the United States.

The Selective Training and Service Act and World War II

In 1940, Europe was already at war, and despite the neutrality of the United States at the time, some in Congress argued that the United States could not continue with a peacetime force while other nations were mobilizing on a massive scale.21 In June 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that he would recommend a program of universal compulsory government service for American youth (men and women).22 A few days later a conscription bill, modeled on the Selective Service Act of 1917, was sponsored by Senator Edward Burke and Representative James Wadsworth in their respective chambers. The bill garnered support by senior Army leaders, who expressed concerns about the ability to recruit a sufficient number of volunteers necessary to fight a major war.23 Some in Congress opposed to the bill argued the following:

Regimentation of American life as provided for by the Burke-Wadsworth bill in peacetime is abhorrent to the ideals of patriotic Americans and is utterly repugnant to American democracy and American traditions ... no proof or evidence was offered to indicate that the personnel needs of the Army and Navy cannot be obtained on a voluntary basis.24

The conscription bill became the Selective Training and Service Act, and was signed into law on September 16, 1940, by Franklin D. Roosevelt.25 The act was the first instance of peacetime conscription in the United States and required men between aged 21 through 35 to register with local draft boards. The law required a 12-month training period for those inducted, at which time the inductees would be transferred to a reserve component of the Armed Forces for 10 years. Criminal penalties for failing to comply with registration or other duties under this act included "imprisonment of not more than five years or a fine of not more than $10,000, or by both such fine and imprisonment."26

The act also gave the President the authority to establish a Selective Service System, and to appoint a Director of the Selective Service with oversight of local civilian boards. Because the image of civilian leadership was deemed important during a time of peace, in 1940 the President initially appointed Dr. Clarence Dykstra as Director of the Selective Service while also retaining his position as president of the University of Wisconsin.27 Due to poor health Dykstra never took up his position as Director of Selective Service. In July 1941, the JANSSC that had been established in the interwar period became the new Selective Service headquarters and Colonel Lewis B. Hershey was appointed as the Director, a position he held until 1970, departing with the rank of Lieutenant General.28

In terms of the implementation of the Selective Service System, there was an emphasis on establishing an equitable lottery system administered by decentralized local draft boards as was deemed a successful approach during WWI:

The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 is based on the principle that the obligation and privileges of military training and service should be shared generally in accordance with a fair and just system of compulsory military training and service.... The public expected that the lottery under the new law would be conducted as the lottery of 1917-1918 was conducted, and those charged with the administration of the Selective Service felt likewise.29

The 6,442 district boards assigned a number to each registrant in their district.30 On October 29, 1940, the first draft lottery was held in a similar manner to the WWI draft lottery and draft inductions into the Army began on November 18, 1940.31 The lottery system was used for three groups of registrants, then abandoned in 1942 and not used again for the draft until 1969 during the Vietnam conflict.32 In the interim, draftees were inducted by local boards based on required quotas and contemporary policies for classification, age, and order of precedence.

Although some complaints arose over inequalities and inconsistencies in the draft administration, a Gallup poll conducted in 1941 found that 93% of those polled thought the draft had been handled fairly in their community.33 Volunteers were allowed to serve; however, approximately 10 million of the 16 million servicemembers who served during WWII were draftees.34

|

Consideration of a Draft for Nurses Following the invasion of Normandy in 1944 and other battles with high casualty rates, the Army was reporting a shortage of nurses to care for the wounded and a shortfall in recruiting efforts. In his 1945 State of the Union (SOTU) address, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for a draft to increase the number of nurses, stating: The inability to get the needed nurses for the Army is not due to any shortage of nurses; 280,000 registered nurses are now practicing in this country. It has been estimated by the War Manpower Commission that 27,000 additional nurses could be made available to the armed forces without interfering too seriously with the needs of the civilian population for nurses. Since volunteering has not produced the number of nurses required, I urge that the Selective Service Act be amended to provide for the induction of nurses into the armed forces. The need is too pressing to await the outcome of further efforts at recruiting.35 Shortly after the SOTU, the House Committee on Military Affairs met to consider legislation for the registration and draft of "trained and skilled women nurses."36 One version of the bill (H.R. 2277) would have required females between the ages of 20 and 45 who had graduated from a 2-year course of instruction to register for selection and induction.37 In testimony, the Surgeon General recommended broadening the medical draft to also support civilian needs, stating It is for these reasons that I recommend the selective-service principle for professional nurses to include minimum civilian as well as total military needs. This is total war. We must mobilize fully to guard against collapse on any front, military or civilian.38 Senior representatives in the nursing profession supported the initiative but called for it to be part of a Selective Service act for all women, not just those qualified as nurses.39 Other groups opposed to the legislation claimed it was unconstitutional to establish a draft of individuals based on their class of work or expertise, and questioned the ability of the War Department to effectively and efficiently manage the nursing resources already at its disposal.40 The bill to draft nurses (H.R. 2277) passed the House on March 7, 1945 by a vote of 347 to 42, and was referred in the Senate on March 29, 1945.41 The Senate twice deferred action on the bill, and it was never enacted. |

Consideration of Universal Compulsory Service

With the induction authority under the Selective Training and Service Act set to expire in 1945, some felt that the emergency conscription program should evolve into a permanent system of universal military training (UMT). 42 The Roosevelt Administration proposed a system that required one year of compulsory training at age 18 for all physically qualified men. In 1945, the congressional Committee on Postwar Military Policy held a series of open hearings on compulsory military training.43 Those in favor of maintaining some form of conscription, including groups like the American Legion, and the Chamber of Commerce, argued that it would provide a deterrent to future "Hitlers and Hirohitos" as well as build the health and character of American youth.44 Those opposed, including organized labor groups and the NAACP, contended that continued conscription was antithetical to democratic ideals, was an inefficient mechanism for building force structure, and led to war, international distrust, and profiteering.45 As the Committee on Postwar Military Policy was not empowered to propose legislation, the debate did not result in congressional action with respect to UMT.46 Instead, Congress extended the induction authority under the Selective Training and Service Act in 1945, and again in 1946 and 1947, allowing it to lapse on March 31, 1947.

In 1947 the Administration under President Truman again pushed for UMT, appointing a commission to study the issue. The President's Advisory Commission on Universal Training (the Compton Report) advocated for UMT as "a matter of urgent necessity."47 The Administration subsequently proposed six months of mandatory training. This proposal was reported out of the House Armed Services Committee in July 1947 but never brought to the House floor and was not considered in the Senate.48

Post-World War II, the Selective Service Act of 1948

In 1947, when the authorities under the Selective Service Act expired, all functions and responsibilities of the Selective Service System were transferred to the Office of Selective Service Records.49 This office, by law, had a limited mandate for knowledge preservation, and maintenance and storage of individual records. This restructuring essentially put the Selective Service System into a deep standby mode.

By 1948, the military had shrunk in size to less than 1.5 million from a peak of 12 million in 1945. Concerned about lagging recruiting efforts and the rising power of the Soviet Union, Congress authorized reinstatement of the draft in the Selective Service Act of 1948, which was signed into law by President Truman on June 24, 1948.50 The act was similar to previous acts authorizing the Selective Service System. It established registration requirements for males ages 19 to 26, and the same criminal penalties for fraudulent registration or evasion. It also dissolved the Office of Selective Service Records and transferred its responsibilities back to the newly established Selective Service System as an independent agency of the federal government. Under this act, the President had authority to appoint state directors of the Selective Service System. It also provided the authority to call National Guard and Reserve personnel into active duty to support the administration of state and national headquarters.

Korean War and the Universal Military Training and Service Act of 1951

The Selective Service Act of 1948 was set to expire on June 24, 1950. Due to budget constraints and absence of an immediate threat to national security, between 1948 and 1949 conscription was only used to fill recruiting shortfalls. On June 25, 1950, war broke out between North and South Korea. A bill to extend the Selective Service Act of 1948 was already in conference, and the Senate rushed to it on June 28 and it was signed by the President on June 30, 1950.51 The following year, Congress renamed the act the Universal Military Training52 and Service Act of 1951.53 The act extended the draft until July 1, 1955, and also lowered the registration age to 18.54 As the new name suggested, the law also contained a clause that would have obligated all eligible males to perform 12 months of military service and training within a National Security Training Corps if amended by future legislation (it was never amended).

The act did not alter the structure or functions of the SSS; however, it did require the Director to submit an annual report to Congress on

- the number of persons registered,

- the number of persons inducted, and

- the number of deferments granted and the basis for them.

The United States inducted approximately 1.5 million men into the military (one-quarter of the total uniformed servicemembers) under this act in support of the Korean conflict. A draft lottery was not used in this era, rather, the DOD issued draft calls, and quotas were issued to local boards. The local boards would then fill their quotas with those classified as "1-A," or "eligible for military service" by precedence as determined by policy.55 Public concerns with the draft at this time were equitable implementation of the draft due to the broad availability of deferments for what some saw as privileged groups. Others expressed concerns about the potential disruption of citizens' lives.56

Between 1950 and 1964 Congress repeatedly extended the Universal Military Training and Service Act in four-year periods with minor amendments. During this time, volunteers made up approximately two-thirds of the total military force with the remainder supplemented through inductions—with some limited exceptions, the Navy, Air Force, and Marines relied on volunteers almost entirely.57 For example, monthly draft calls in 1959 were for approximately 9,000 men out of an eligible population of about 2.2 million.58

|

The Doctor Draft and The Berry Plan A 1950 amendment to the Selective Service Act of 1948, commonly referred to as the Doctor Draft, provided for the "special registration, classification, and induction of certain medical, dental, and allied specialist categories."59 The law allowed for draft calls for medical professionals up to 50 years of age for a period of service for no longer than 21 months. The law also established a National Advisory Committee to coordinate with states and localities to ensure that consideration was given to the needs of the civilian populations in communities with few medical personnel. Members of the reserve component were not liable for registration or induction. The law, however, also provided a special pay entitlement to reserve medical and dental officers involuntarily ordered to active duty, as well as to those volunteering for active duty. This was designed as in incentive for draft-liable medical professionals to voluntarily serve in lieu of being inducted as an enlisted member.60 The Doctor Draft was extended twice. Amendments in 1955 reduced the age limit to 46 and allowed it to expire on July 1, 1957.61 At that time, facing objections to the draft from organizations such as the American Medical Association, DOD indicated that it would not seek a further extension of the authorization.62 In the meantime, DOD had also initiated other mechanisms incentivizing medical service. Dr. Frank B. Berry, who served as the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health and Medical Affairs starting in 1954, implemented a program under which both civilian hospitals and the military were able to meet staffing needs. This program, which came to be known as The Berry Plan, allowed doctors to defer obligatory military service until completion of medical education and training.63 Those that did not choose one of the options risked being drafted through the regular registration process, which encouraged participation. It is estimated that about two-thirds of physicians that served between 1950 and 1973 were obtained through the draft or through the Berry Plan. 64 |

The Vietnam War and Proposals for Draft Reform

In 1964, when America significantly escalated its military involvement in Vietnam, conscription was again used to mobilize manpower and augment the volunteer force. Among the criticisms of the draft system during this period were that it was inequitable and discriminatory since the chance of being drafted varied by state, by local community, and by one's economic status. In the late 1960s, public acceptance of the draft began to erode for the following reasons, inter alia:65

- Opposition to the war in Vietnam.

- The U.S. Army's desire for change due to discipline problems among some Vietnam draftees.

- Belief that the state did not have a right to impose military service on young men without consent.

- Belief that the draft was an unfair "tax" being imposed only on young men in their late teens and twenties.66

- Perception of some observers that the draft placed an unfair burden on underprivileged members of society.67

- Demographic change increasing the size of the eligible population for military service relative to the needs of the military.68

- Estimations that an all-volunteer force could be fielded within acceptable budget levels.69

In response to some of these concerns and associated political pressures, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11289 on July 2, 1966, establishing the National Advisory Commission on Selective Service headed by Burke Marshall. President Johnson instructed the commission to consider past, present, and prospective functioning of the Selective Service System and other systems of national service, taking into account the following factors:

- Fairness to all citizens,

- Military manpower requirements,

- Minimizing uncertainty and interference with individuals' careers and educations,

- National social, economic, and employment goals, and

- Budgetary and administrative considerations.

The commission examined a number of potential options from requiring everyone to serve to elimination of all compulsory service. The commission's final report, In Pursuit of Equity: Who Serves When not all Serve?, was delivered to the President in February 1967 at the time when the Selective Service law was up for renewal. The commission recommended continuing conscription but making significant changes to the Selective Service System to "assure equal treatment for those in like circumstances."70 Among these recommended changes were (1) adopting an impartial and random selection process and order of call, (2) consolidating the local boards under centralized administration with uniform policies for classification, deferment, and exemptions, and (3) ensuring that composition of local boards was representative of the population that they served.71

In parallel with the Presidential Commission's review, the House Armed Services Committee chartered their own review with a civilian advisory panel chaired by retired Army General Mark Clark. The Clark panel also recommended against shifting to an all-volunteer force but disagreed on the establishment of a lottery.72

In 1967, Congress extended the SSS through July 1, 1971, under the renamed Military Selective Service Act of 1967 (henceforth MSSA). While the Administration had pushed for comprehensive draft reform based on the commission's recommendations, the bill contained few of President Lyndon Johnson's proposals. In particular, the bill, as enacted, prohibited the President from establishing a random system of selection (draft lottery) without congressional approval.73

In 1969, President Richard M. Nixon called on Congress to provide the authority to institute the draft lottery system. In response, Congress amended the 1967 law, repealing the prohibition on the President's authority. 74 On the same day, President Nixon signed Executive Order 11497 establishing the order of call for the draft lottery for men aged 19 through 25 at the end of calendar year 1969. In the first year, all males age 19 through 25 were to be in the lottery. After that, only those who turned 19 each year were entered into the lottery, and were susceptible for a single year to being drafted.

While the draft remained contentious, in 1971 the induction authority under the MSSA was again extended through 1973.75 In response to concerns regarding the composition of local boards, the bill stated,

The President is requested to appoint the membership of each local board so that to the maximum extent practicable it is proportionately representative of the race and national origin of those registrants within its district.

The bill also included a significant pay raise for military members as a first step toward building an all-volunteer force.

The Gates Commission

Two months into President Nixon's first term, he launched the President's Commission on an All-Volunteer Force, which came to be known as the Gates Commission. In its 1970 report, the commission unanimously recommended that "the nation's best interests will be better served by an all-volunteer force, supported by an effective standby draft, than by a mixed force of volunteers and conscripts."76 The Gates Commission also recommended maintaining a Selective Service System that would be responsible for

- a register of all males who might be conscripted when essential for national security,

- a system for selection of inductees,

- specific procedures for the notification, examination, and induction of those to be conscripted,

- an organization to maintain the register and administer the procedures for induction, and

- the provision that a standby draft system may be invoked only by resolution of Congress at the request of the President.77

The last draft calls were issued in December 1972 and the statutory authority to induct expired on June 30, 1973.78 On January 27, 1973, Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird announced the end of conscription. The last man to be inducted through the draft entered the Army on June 30, 1973.79

Table 1 shows the number of inductees and total participants for each major conflict in which the United States used the draft and for which data are available. More than half of the participants in WWI and nearly two-thirds of the WWII participants were draftees. About one-quarter of the participants in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts were draftees, however, it should be noted that the possibility of being drafted may have induced higher rates of volunteerism during these later conflicts.80

|

Conflict |

Total Conscripts |

Total Participants |

% Conscripts of Total Participants |

|

Civil War (Union only) |

168,649* |

2,690,401 |

6.2% |

|

WWI |

2,810,296 |

4,734,991 |

59.4% |

|

WWII |

10,110,104 |

16,112,566 |

62.7% |

|

Korea |

1,529,539 |

5,720,000 |

26.7% |

|

Vietnam |

1,857,304 |

8,744,000 |

21.3% |

Source: Total conscripts are those inducted into service as reported by the Selective Service System (https://www.sss.gov/About/History-And-Records/Induction-Statistics). Total participants are from the Department of Veterans Affairs at http://www.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_americas_wars.pdf. Civil War data are taken from Crowder, E.H., Second Report of the Provost Marshal General to the Secretary of War On the Operations of the Selective Service System to December 20, 1918, GPO, Washington, DC, 1919, p. 376.

Notes: Figures for total participants are rounded to the nearest thousand in the source document for Vietnam and Korea. The total number of conscripts in the Civil War is only those actually inducted into service and includes those who were furnished as substitutes but excludes those who were drafted but paid a commutation in lieu of service.

All-Volunteer Force (AVF) and a Standby SSS

President Gerald Ford temporarily suspended the registration requirement through Proclamation 4360 (89 Stat. 1255) in April 1975.81 The MSSA was not repealed, however, and the requirement for the SSS to be ready to provide untrained manpower in a military emergency remained. This proclamation essentially put the SSS into deep standby mode. Between 1975 and 1977, the SSS reduced operational functions and shifted into a new role as a planning agency.82 At the time there were approximately 98 full-time staff operating a pared-down field structure with a national headquarters and nine regional headquarters.83 In the late 1970s, some were concerned that this "deep standby" system did not have the resources or infrastructure to register, select, classify, and deliver the first inductees within 30 days from the start of an emergency mobilization.84

These concerns became even more salient when, in December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. In his January 1980 State of the Union address, President Jimmy Carter announced his intention to resume draft registration requirements in the coming year.85 A Gallup Poll conducted in March 1980 found that 76% were in favor of a registration requirement for young men.86 Congress responded by providing $13.3 million in appropriations for the Selective Service System on June 25, 1980.87 President Carter signed Proclamation 4771 on July 2, 1980, reinstating the requirement for all 18- to 25-year-old males to register for the Selective Service, under the authority provided by the MSSA.88 Penalties for failing to register were the same as those first established in the 1940 Selective Training and Service Act (a fine of up to $10,000 and/or a prison term of up to five years). However, unlike in previous draft registration regulations, there was no requirement for men to undergo evaluation and classification for fitness to serve.

The core functions of the reinstated SSS had five key components that are still largely in place today:

- A registration process that is reliable and efficient.

- An automated data processing system that could handle pre- and post-mobilization requirements.

- A system for promulgation and distribution of orders for induction.

- A claims process that can quickly insure all registrants' rights to due process are protected.

- A field structure that can support the claims process.89

Supporters of reestablishing the registration requirement for men argued that it would send a message to the Soviet Union that the United States was prepared to act to defend its interests and also that it would cut down the mobilization time in the event of a national emergency. Some argued that registration was not enough, and advocated for a return of peacetime conscription, universal military training, or compulsory national service.90

Organizations opposed to the reinstatement of registration requirements argued that registration forms were illegal because they required registrants to disclose their Social Security numbers. Others argued that the exemption of women in the draft law was unconstitutional.91 Carter's proposal to Congress included legislative language that would have given the President the authority to register women. As justification for this proposal, he stated,

My decision to register women is a recognition of the reality that both women and men are working members of our society. It confirms what is already obvious throughout our society – that women are now providing all types of skills in every profession. The military should be no exception. […] There is no distinction possible, on the basis of ability or performance, that would allow me to exclude women from an obligation to register.92

Congress rejected the President's proposal to include women with an explanation under Title VIII of S. Rept. 96-826,

[T]he starting point for any discussion of the appropriateness of registering women for the draft is the question of the proper role of women in combat. The principle that women should not intentionally and routinely engage in combat is fundamental, and enjoys wide support among our people. It is universally supported by military leaders who have testified before the committee, and forms the linchpin for any analysis of this problem. […] Current law and policy exclude women from being assigned to combat in our military forces, and the committee reaffirms this policy. The policy precluding the use of women in combat is, in the committee's view, the most important reason for not including women in a registration system.

In 1981, the Supreme Court heard a challenge to the exception for women to register for Selective Service. In the Rostker v. Goldberg case, the Court held that the practice of only registering men for the draft was constitutional.93 In the majority opinion, Justice William Rehnquist wrote

[t]he existence of the combat restrictions clearly indicates the basis for Congress' decision to exempt women from registration. The purpose of registration was to prepare for a draft of combat troops. Since women are excluded from combat, Congress concluded that they would not be needed in the event of a draft, and therefore decided not to register them.

New Penalties for Registration Noncompliance

The first national registration after the reinstatement of the requirement was held in 1980 through registration at local U.S. Post Offices.94 The registration rate for the 1980 registration was 87% within the two-week registration period and 95% through the fourth month of registrations. In 1973, the registration rates were 77% within 30 days of one's 18th birthday as required by statute, and 90% through the fourth month.95 The Comptroller General estimated that, of the registrations submitted, there was a final accuracy level of 98%.96

Despite initial successes in registration, there was a push by many in Congress and the Reagan Administration to maintain public awareness of the requirements and to maintain high compliance rates. On January 21, 1982, President Ronald Reagan authorized a grace period until February 28, 1982, allowing those who had not registered to do so. In 1982, the Department of Justice (DOJ) began prosecution of those men who willfully refused to register for selective service.97 In the June 1983 SSS semiannual report to Congress, the agency reported that it had referred 341 persons to DOJ for investigation. At the time of the report, there were 11 indictments and 2 convictions.

In the same year, there was a movement in Congress to tie eligibility for federal benefits to registration requirements. National Defense Authorization bills for Fiscal Year 1983 were reported to the House and Senate floor without any proposed amendments to the MSSA. However, on May 12, 1982, the bill was amended by Senators Hayakawa and Mattingly on the Senate floor to prohibit young male adults from receiving any federal student assistance under Title IV of the Higher Education Act if they cannot certify they had registered with Selective Service. The Senate passed the amendment as drafted by voice vote. Representative Jerry Solomon introduced a similar amendment on the House floor. In conference committee, Members added language to direct the Secretary of Education and the Director of Selective Service to jointly develop methods for certifying registration.98 This provision amending the MSSA was signed into law as part of the FY1983 NDAA with an effective date of July 1, 1983.99

Representative Solomon also led the effort to attach similar language to the Job Training Partnership Act of 1982, which was passed on October 13, 1982.100 This law prohibited those who failed to register from receiving certain federal job training assistance. Congress repealed the Job Training and Partnership Act and replaced it with the Workforce Investment Act of 1998; however, the statutory language enforcing the MSSA was maintained in the new law.101

In 1985, Congress added a provision to FY1986 NDAA that made an individual ineligible for federal civil service appointments if he "is not registered and knowingly and willfully did not so register before the requirement terminated or became inapplicable to the individual."102 Congress also expressed support for the peacetime registration program as a "contribution to national security by reducing the time required for full defense mobilization," and as sending "an important signal to our allies and to our potential adversaries of the United States defense commitment."103

On November 6, 1986, President Reagan signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act.104 This law required males between the ages of 18 and 26 who are applying for legalization under the act to register for the Selective Service if they have not already done so. In response, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and the SSS established procedures for registering young men as part of the immigration application process.105

|

The Healthcare Personnel Delivery System (HCPDS) In the early 1980s, Congress raised concerns about readiness of the medical force and the ability of the Services to mobilize necessary medical personnel to deliver casualty care in the event of a war. The General Accounting Office (GAO) was asked to review this question and in 1981 released a report with recommendations for DOD, SSS, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for improving wartime medical preparedness.106 GAO found that if mobilization for major conflict were to occur, DOD would not be able to meet medical personnel requirements, with the report stating, shortages of physicians, nurses, and enlisted medical personnel would be most severe, would reduce capability to deliver wartime care, and would begin to occur soon after mobilization. Shortages of surgical personnel would be especially critical because theater of operations requirements could not be met.107 Another finding was that while the civilian sector likely had sufficient medical personnel to augment the force, the responsible agencies did not have adequate plans in place to mobilize and train civilian practitioners to provide effective wartime care.108 With respect to the SSS, the GAO noted that there was no authority that would provide for a draft of individuals with specialty skills. As such, GAO recommended that DOD and SSS jointly develop legislative provisions for a standby post-mobilization draft of civilian medical personnel. By request of the SSS, in 1987 Congress authorized SSS spending to "design and develop such a standby system to prepare for the post-mobilization registration and classification of persons with essential health care delivery skills."109 This law expanded the SSS mandate to also include responsibility to maintain "a structure for registration and classification of persons qualified for practice or employment in a health care occupation essential to the maintenance of the Armed Forces."110 The standby system developed under this law is called the Health Care Personnel Delivery System (HCPDS). The system is designed to be implemented by the SSS in a national emergency if legislated by the Congress and approved by the President. Following these approvals, the SSS would conduct a mass registration of both male and female health care workers between the ages of 20 and 45.111 |

Other Legislative Proposals since 1980

Between 1980 and 2020, several Members of Congress proposed a number of legislative changes to the MSSA; however, none have been enacted. Typically, such proposed changes to the MSSA have included one or more of the following options:

- Repeal the entire MSSA.112

- Terminate the registration requirement.113

- Reinstate draft induction authority.114

- Defund the Selective Service System.115

- Require women to register for the draft.116

Other proposed changes would seek to modify SSS record management or registration processes.117 These options are discussed in more detail later in this report.

National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service

In the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328), Congress established a National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service to help consider some of the options for the future of the MSSA. The commission is tasked not only with a review of the military selective service process, but also with proposing "methods to increase participation in military, national, and other public service, in order to address national security and other public service needs of the Nation."118 The statutory scope of the commission is to review

(1) The need for a military selective service process, including the continuing need for a mechanism to draft large numbers of replacement combat troops;

(2) means by which to foster a greater attitude and ethos of service among United States youth, including an increased propensity for military service;

(3) the feasibility and advisability of modifying the military selective service process in order to obtain for military, national, and public service individuals with skills (such as medical, dental, and nursing skills, language skills, cyber skills, and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) skills) for which the Nation has a critical need, without regard to age or sex; and

(4) the feasibility and advisability of including in the military selective service process, as so modified, an eligibility or entitlement for the receipt of one or more Federal benefits (such as educational benefits, subsidized or secured student loans, grants or hiring preferences) specified by the Commission for purposes of the review.

Section 552 of the FY2017 NDAA also required DOD to prepare a preliminary report on the purpose and utility of the SSS to support the commission's work, to include

(1) A detailed analysis of the current benefits derived, both directly and indirectly, from the Military Selective Service System, including— (A) the extent to which mandatory registration benefits military recruiting; (B) the extent to which a national registration capability serves as a deterrent to potential enemies of the United States; and (C) the extent to which expanding registration to include women would impact these benefits.

(2) An analysis of the functions currently performed by the Selective Service System that would be assumed by the Department of Defense in the absence of a national registration capability.

(3) An analysis of the systems, manpower, and facilities that would be needed by the Department to physically mobilize inductees in the absence of the Selective Service System.

(4) An analysis of the feasibility and utility of eliminating the current focus on mass mobilization of primarily combat troops in favor of a system that focuses on mobilization of all military occupational specialties, and the extent to which such a change would impact the need for both male and female inductees.

(5) A detailed analysis of the Department's personnel needs in the event of an emergency requiring mass mobilization, including— (A) a detailed timeline, along with the factors considered in arriving at this timeline, of when the Department would require— (i) the first inductees to report for service; (ii) the first 100,000 inductees to report for service; and (iii) the first medical personnel to report for service; and (B) an analysis of any additional critical skills that would be needed in the event of a national emergency, and a timeline for when the Department would require the first inductees to report for service.

(6) A list of the assumptions used by the Department when conducting its analysis in preparing the report.

DOD submitted its congressionally mandated report in July 2017. The report noted that the department "currently has no operational plans that envision mobilization at a level that would require conscription." Nevertheless, it acknowledges that, "the readiness of the underlying systems, infrastructure, and processes to effect [a draft] – serve as a quiet but important hedge against an unknowable future."119

GAO's report, released in January 2018, noted that DOD's requirements and timeline for mobilization of forces remain unchanged since 1994, despite changes to force structure, capability needs, national security environment, and strategic objectives.120 In particular, the report authors stated the following:

DOD provided the personnel requirements and a timeline that was developed in 1994 and that have not been updated since. These requirements state that, in the event of a draft, the first inductees are to report to a Military Entrance Processing Station in 193 days and the first 100,000 inductees would report for service in 210 days. DOD's report states that the all-volunteer force is of adequate size and composition to meet DOD's personnel needs and it has no operational plans that envision mobilization at a level that would require a draft. Officials stated that the personnel requirements and timeline developed in 1994 are still considered realistic. Thus, they did not conduct any additional analysis to update the plans, personnel requirements, or timelines for responding to an emergency requiring mass mobilization.

The authors stated that the GAO's 2012 recommendation that DOD "establish a process of periodically reevaluating DOD's requirements for the Selective Service System in light of changing operating environments, threats, and strategic guidance" remains valid.

The National Commission on Military, National and Public Service released an interim report on its preliminary research findings on January 23, 2019. The commission released its final report on March 25, 2020.121

With respect to the Selective Service and the draft the commission made several recommendations:

- Maintain a military draft mechanism in the event of national emergencies;

- Formalize a national call for volunteers prior to activating the draft;

- Retain the Selective Service System's current registration posture;

- Convey to registrants their potential obligation for military service;

- Ensure a fair, equitable, and transparent draft, including a mechanism to allow corrective registration and avoid lifelong penalties;

- Develop new voluntary models for accessing personnel with critical skills;

- Improve the readiness of the National Mobilization System through institutionalized exercises and better accountability; and

- Extend Selective Service registration to women.122

The commission made several other recommendations to increase civic education and outreach, strengthen military recruiting and marketing, incentivize and expand national service, and improve personnel management in the military and federal civil service.123

|

Inspired to Serve Act; Draft Legislation The National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service provided a Legislative Annex containing the legislative proposals as required by Section 555(e)(1) of the National Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2017 (P.L. 114-328). These proposals are presented in the form of a consolidated bill, the Inspire to Serve Act of 2020. The proposals, along with section-by-section analysis and redlines against existing law, are available on the Commission's website, http://www.inspire2serve.gov |

Selective Service Registration

Today, nearly all males residing in the United States—U.S. citizens and documented or undocumented immigrant men—are required to register with the Selective Service if they are at least 18 years old and are not yet 26 years old. Those who are required to register must do so within 30 days of their 18th birthday unless exemptions apply as listed in Table 2. Men born from March 29, 1957, to December 31, 1959, were never required to register because the registration program was not in effect at the time they turned 18. Individuals are not allowed to register beyond their 26th birthday. Women are currently not required to register for the Selective Service. Federal regulations state, "No person who is not required by selective service law or the Proclamation of the President to register shall be registered."124 All of those required to register would be considered "available for service" in the case of an emergency mobilization unless they were reclassified by the SSS.125

|

Category |

YES |

NO |

|

All male U.S. citizens born after Dec. 31, 1959, who are 18 but not yet 26 years old, except as noted below: |

√ |

|

|

Military Related |

||

|

Members of the Armed Forces on active duty (active duty for training does not constitute "active duty" for registration purposes) |

√* |

|

|

Cadets and Midshipmen at Service Academies or Coast Guard Academy |

√* |

|

|

Cadets at the Merchant Marine Academy |

√ |

|

|

Students in Officer Procurement Programs at the Citadel, North Georgia College and State University, Norwich University, Virginia Military Institute, Texas A&M University, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University |

√* |

|

|

Reserve Officers' Training Corps Students |

√ |

|

|

National Guardsmen and Reservists not on active duty/Civil Air Patrol members |

√ |

|

|

Delayed Entry Program enlistees |

√ |

|

|

Separatees from Active Military Service, separated for any reason before age 26 |

√* |

|

|

Men rejected for enlistment for any reason before age 26 |

√ |

|

|

**Immigrants |

||

|

Lawful nonimmigrants on visas (e.g., diplomatic and consular personnel and families, foreign students, tourists with unexpired Form I-94, or Border Crossing Document DSP-150) |

√ |

|

|

Permanent resident immigrants (USCIS Form I-551)/Undocumented immigrants |

√ |

|

|

Special agricultural workers |

√ |

|

|

Seasonal agricultural workers (H-2A Visa) |

√ |

|

|

Refugee, parolee, and asylum immigrants |

√ |

|

|

Dual national U.S. citizens |

√ |

|

|

Confined |

||

|

Incarcerated, or hospitalized, or institutionalized for medical reasons |

√* |

|

|

Handicapped physically or mentally |

||

|

Able to function in public with or without assistance |

√ |

|

|

Continually confined to a residence, hospital, or institution |

√ |

|

|

Gender Change/Transgender |

||

|

Individuals who are born female and changed their gender to male |

√ |

|

|

U.S. citizens or immigrants who are born male and change their gender to female |

√ |

Source: Selective Service Agency (https://www.sss.gov/Registration/Who-Must-Register/Chart).

Notes: * These individuals must register within 30 days of release unless already age 26. To be fully exempt the individual must have been on active duty or confined continuously from age 18 to 26.

** Residents of Puerto Rico, Guam, Virgin Islands, and Northern Mariana Islands are U.S. citizens. Citizens of American Samoa are nationals and must register when they are habitual residents in the United States or reside in the United States for at least one year. Habitual residence is presumed and registration is required whenever a national or a citizen of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, or Palau resides in the United States for more than one year in any status, except when the individual resides in the United States as an employee of the government of his homeland; or as a student who entered the United States for the purpose of full-time studies, as long as such person maintains that status. Immigrants who did not enter the United States or maintained their lawful nonimmigrant status by continually remaining on a valid visa until after they were 26 years old were never required to register. Also, immigrants born before 1960 who did not enter the United States or maintained their lawful nonimmigrant status by continually remaining on a valid visa until after March 29, 1975, were never required to register.

Processes for Registration

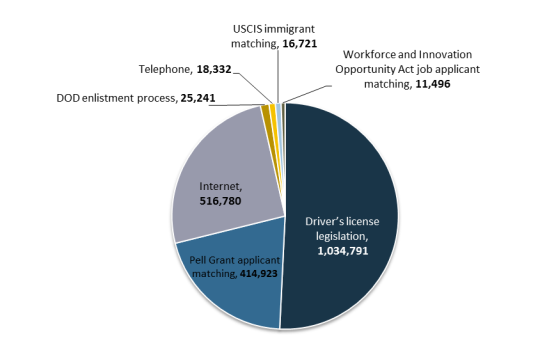

Almost all Selective Service registrations are completed electronically; however, registration can also be done at U.S. Post Offices and by submission of paper registrations.126 Forty-one states, four territories, and the District of Columbia (DC) have driver's license legislation that provides for automatic Selective Service registration when obtaining a driver's license, driver's permit, or other form of identification from the 1 million Department of Motor Vehicles.127 In FY2019, 51% of all registrations, representing just over young men, were conducted electronically through driver's license legislation (see Figure 1).128

The SSS also has interagency agreements for registration. In cooperation with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), immigrant men ages 18 through 25 who are accepted for permanent U.S. residence are registered automatically. In addition, men of registration age who apply for an immigrant visa through the Department of State are also registered. The application form for federal student aid includes a "register me" checkbox for those who have not yet registered for the Selective Service, which authorizes the SSS to automatically register those individuals.129 The SSS reports that approximately 20% of its electronic registrant data come from the Department of Education (ED) as part of the Pell Grant student aid application process.130 The SSS also has existing data-sharing relationships with the DOD for new enlistments and the Department of Labor for applicants under the Workforce and Innovation Opportunity Act.131

Registration compliance rate for the 18- through 25-year old age group was 91% in calendar year 2018, above the SSS goal of 90%.132 Reasons for noncompliance may include lack of awareness of requirements or purposeful avoidance. Knowingly failing to register comes with certain penalties including the following:

- If indicted, imprisonment of not more than five years and/or fine of not more than $10,000 (increased to $250,000 in 1987 by 18 U.S.C. §3571(b)(3)).133

- Ineligibility for federal student aid.134

- Ineligibility for appointment to a position in an executive agency.135

- Ineligibility for certain federal job training benefits.136

- Potential ineligibility for citizenship (for certain immigrants to the United States).137

- Possible inability to obtain a security clearance.138

In addition, a large number of state legislatures as well as county and city jurisdictions have conditioned eligibility for certain government programs and benefits on SSS registration.139

Failing to register for the Selective Service, or knowingly counseling, aiding, or abetting another to fail to comply with the MSSA, is considered a felony. Those who fail to register may have their names forwarded to the DOJ. In FY2018, 112,051 names and addresses of suspected violators were provided to DOJ.140 In practice, there have been no criminal prosecutions for failing to register since January 1986. At that time the SSS reported a total of 20 indictments with 14 convictions.141

Other penalties adversely affect the population required to register. For example, California estimated that between 2007 and 2014, young men in that state who failed to register were denied access to more than $99 million in federal and state financial aid and job training benefits.142

There is some relief from penalties for those who fail to register. The MSSA establishes a statute of limitations on criminal prosecutions for evading registration to five years after a fraudulent registration or failure to register, whichever is first.143 Also, individuals may not be denied federal benefits for failing to register if

- the requirement to register has terminated or become inapplicable to the person; and

- the person shows by a preponderance of the evidence that the failure of the person to register was not a knowing and willful failure to register.144

Individuals who unknowingly fail to register may ask for reconsideration from the official handling their case and may be required to submit evidence that they were unaware of their requirement to register.

Selective Service System Agency Overview

The SSS is an independent federal agency within the executive branch with headquarters located in Arlington, VA. It is not part of the Department of Defense. The agency is currently maintained as an active standby organization, which means that most of its functions are administrative. The statutory missions of the SSS are to maintain

- a complete registration and classification structure capable of immediate operation in the event of a national emergency (including a structure for registration and classification of persons qualified for practice or employment in a health care occupation essential to the maintenance of the Armed Forces), and

- personnel adequate to reinstitute immediately the full operation of the System, including military reservists who are trained to operate such System and who can be ordered to active duty for such purpose in the event of a national emergency.145

If the SSS were activated with the authority to induct individuals, the agency would be responsible for (1) holding a national draft lottery, (2) contacting registrants who are selected via the lottery, (3) arranging transportation for selectees to Military Entrance Processing Stations (MEPS) for testing and evaluation of fitness to serve, and (4) activating a classification structure that would include area offices, local offices, and appeal boards.146 Local boards would also evaluate claims for exemption, postponement, or deferments. Those classified as conscientious objectors would be required to serve in a noncombatant or nonmilitary capacity. For those permitted to serve in a nonmilitary capacity, the SSS would be responsible for placing these "alternative service workers" with alternate employers and tracking completion of 24 months of their required service.

|

Categories for Exemption or Deferment Under Current SSS Operating Procedures

Source: Selective Service System. |

Workforce and Organization

The agency's workforce is comprised of full-time career employees, part-time military and civilian personnel, and approximately 11,000 part-time civilian volunteers.147 In FY2019, the agency had 124 full-time equivalent civilian positions for administration and operations across agency headquarters, the Data Management Center, and three regional headquarters offices.148 Part-time employees include 56 State Directors representing the 50 states, four territories, the District of Columbia, and New York City. The median General Schedule (GS) grade for the agency is GS-11.149

The SSS maintains a list of unpaid volunteers who serve as local, district, and national appeal board members who could be activated to help decide the classification status of men seeking exemptions or deferments in the case of a draft. The SSS also has positions for 175 part-time Reserve Forces Officers (RFOs) representing all branches of the Armed Forces.150 RFO duties include interviewing Selective Service board member candidates, training board members, participating in readiness exercises, supporting the registration public awareness effort, and maintaining space, equipment, and supplies.151

Funding

Congress appropriates funds for the SSS through the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act.152 For FY2020, Congress appropriated $27.1 million, an increase over the FY2019 appropriation of $26 million. The budget request for FY2021 was $26 million.153 In FY1977-FY1979, while the SSS was in "deep standby" mode, funding for the agency was between $6 million and $8 million in then-year dollars (approximately $26-$34 million in 2020 dollars).154

Currently, about 60% of the agency's annual budget goes to personnel costs, including civilian pay and benefits and Military Reserve Officer support (see Table 3). 155

|

Function |

Amount |

|

Civilian Pay & Benefits |

$13,576,941 |

|

Military Reserve Officer Support Services |

$1,526,327 |

|

Agency Services (Government & Commercial) |

$4,231,313 |

|

IT Software & Equipment |

$3,483,253 |

|

GSA Occupancy Agreement (OA), Other Rent, Lease, Storage, |

$835,700 |

|

Postage & Express Courier Services |

$797,883 |

|

Communications Services, Utilities, and Facilities Operations |

$425,428 |

|

Printing & Reproduction |

$407,070 |

|

General Supplies and Furniture |

$375,379 |

|

Training, Travel, and Transportation of Personnel |

$274,885 |

|

Strategic Initiatives |

$65,821 |

|

Total |

$26,000,000 |

Source: Selective Service System, Annual Report to the Congress of the United States: Fiscal Year 2019, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, 2019, p. 19.

Data-Sharing and Data Management

The agency maintains data for registrants until their 85th birthday at the Data Management Center in Palatine, IL; the center is authorized 48 full-time employees.156 The purpose of retaining the data for this length of time is to enable SSS to verify eligibility for registered males who apply for certain government employment or benefits. According to the SSS, this database had 78 million records in FY2017 and grows by 2 million to 2.5 million records per year. 157 The information held in this database includes registrants' full name, date of birth, street address, city, state, zip code, and Social Security number.158 In FY2018, recognizing the need for digital and mobile information, the SSS started collecting email addresses and phone numbers.159 The SSS also maintains a "Suspected Violator Inventory System," which includes data on non-registrants that the SSS has received through data-sharing agreements.160 The SSS uses information on this list to reach out to individuals and remind them of their obligation to register.

Most of the registration and data-sharing is automated. The SSS both provides data to and receives data from other government agencies, including the Department of Labor, the Department of Education, the Department of State, USCIS, DOD, and the Alaska Permanent Fund. Information received from these agencies by the SSS is matched with existing data and if no record exists, one is created.

On a monthly basis, SSS provides the Joint Advertising and Market Research Studies (JAMRS, part of DOD) new registrant names, addresses, and date of birth, and a file of individuals identified as deceased.161 These data are kept for three years by JAMRS and are used by DOD for recruiting purposes. Yearly, SSS provides the names, addresses, and Social Security numbers of individuals ages 18 through 25 to the U.S. Census Bureau for its intercensus estimate program. The Census Bureau keeps these data for two years. Annually, the SSS also sends DOJ a list of individuals who are required to register, but have failed to do so.162

Men are required to update the Selective Service within 10 days when their address changes until January 1 of the year that they turn 26 years old. Those who register at 18 years old are likely to move at least once, if not a number of times, before their 26th birthday. For example, a college-bound 18-year-old may move away from their parents' home to university housing, then into an off-campus apartment, and into a new home after graduation. The SSS updates addresses in its database using information from other agencies and self-reported information from individuals.

What are Some Options for the Future of the Selective Service System?

Although Congress has amended the MSSA a number of times, some of its main tenets—the preservation of a peacetime selective service agency and a registration requirement—have remained much the same since the mid-20th century. The future of the Selective Service System is a concern for many in Congress. The registration requirements and associated penalties affect young men in every congressional district.

Some see the preservation of the SSS as an important component of national security and emergency preparedness. Others suggest the MSSA is no longer necessary and should be repealed. Still others have suggested amendments to the MSSA to address issues of equity, efficiency, and cost.

Arguments For and Against Repeal of MSSA

Some form of selective service legislation has been in effect almost continuously since 1940. Repealing the MSSA and associated statute would dismantle the SSS agency infrastructure and would remove the registration requirement with its associated penalties. Efforts to repeal the Selective Service Act have been repeatedly introduced in Congress, and repeal is popular among certain advocacy groups and defense scholars.163

Those who would like to repeal the MSSA and disband the SSS question whether a draft mechanism is still necessary in the modern-day context. A return to the draft has been unpopular with a majority of the American public.164 Some argue that there is a low likelihood of the draft ever being reinstated. Even in the face of nearly two decades of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, DOD has maintained its ability to recruit and retain a professional volunteer force without resorting to conscription. The nature of warfare has shifted in such a way that the United States may not need to mobilize manpower at the rates seen in the 20th century. Even if such high mobilization rates were needed, some question whether the Armed Forces would have the capacity and infrastructure to rapidly absorb the large numbers of untrained personnel that a draft would provide.165 DOD has reported that the Military Entry Processing Command can process approximately 18,000 registrants per day. These new accessions would then be sent to training centers/duty stations as identified by the Office of the Secretary of Defense.166

Some analysts have suggested that a draft, if implemented, would be an inefficient use of labor, as it would "indiscriminately compel employment in the military regardless of an individual's skills where that individual could have much greater value to our society elsewhere."167 Others, including civil rights advocacy groups, contend that the registration requirement and conscription are an invasion of civil liberty.

Those who advocate for maintaining the MSSA but suspending of all SSS activity contend that the SSS infrastructure and registrant databases could be reconstructed in due time if the need arose.168 In the short term, additional manpower needs might be augmented by Delayed Entry Program (DEP) participants, non-prior service reservists awaiting training, and other inactive reserve manpower.169 A reauthorization of the draft might also encourage volunteerism, as choosing a branch of service and occupational specialty might be more preferable to the possibility of being drafted into a less favorable branch and occupation. This might have the potential to provide adequate volunteer manpower until the SSS mechanisms could be fully re-established. Others are skeptical that a post-mobilization registration system could be quickly established in a time of national crisis.170

Proponents of maintaining the SSS and registration requirement often cite a few key arguments. First, at approximately $26 million per year, some have argued that it provides a "low-cost insurance policy" against potential future threats that may require national mobilization beyond what could be supported by the all-volunteer force. Second, adversaries of the United States could see the disbanding of the SSS as a potential weakness, thus emboldening existing or potential enemies. Third, the registration requirement is important to maintain connections between the all-volunteer force and civil society by creating an awareness of the military and the duty to serve in time of crisis among the nation's youth.

The National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service (henceforth "the 2020 Commission), found little evidence that the maintenance of the SSS either deters potential adversaries or helps forge connections between American citizens and the military. However, the 2020 Commission recommended maintaining the SSS and mandatory registration as a draft contingency mechanism, stating

After extensive review, the Commission reaffirms the need to maintain a contingency for mandatory military service in order to draw on the talents, skills, and abilities of Americans in the event of a national emergency, and to clarify the purpose of that system in law. The Selective Service is an essential component of the Nation's military preparedness.171

Other Legislative Options and Considerations

Some of the options for amending the MSSA include the following:

- Repealing the registration requirement (with or without maintaining the SSS as an agency),

- Transferring SSS functions to an existing federal agency,

- Removing or modifying penalties for failure to register,

- Requiring women to register,

- Enhancing SSS data collection for the acquisition of critical skills, and

- Strengthening ability to respond to a national mobilization.

Repealing the Peacetime Registration Requirement

Congress could repeal the registration requirement and terminate the existing penalties for failing to register.172 Removing the registration requirement and the need to verify registration would reduce the activities of the SSS. In this instance, the agency's functions would likely be limited to historical record preservation and maintenance of standby plans and volunteer rolls.

Some have proposed that if registrant data were needed for a future draft, they might be acquired through existing federal or state government databases. The current SSS database relies heavily on information collected by other federal and state entities for initial inputs, updates, and verification of registrants' address information. However, this data sharing is enabled by existing statutes and agency agreements that if repealed or allowed to lapse might require time and effort to reconstitute. The use of existing government or even commercial databases to develop a list of draft-eligible youth also raises concerns about a fair and equitable draft, as these lists might also exclude some draft-eligible individuals.173

In the case of a national emergency, Congress could enact a new statutory requirement for draft registration, and reconstitute the SSS (if it had been dissolved). A 1997 GAO study found that the time needed to raise the necessary infrastructure might be insufficient to respond to urgent DOD requirements.174 There may be other challenges in enforcing a new registration requirement in a time of national need. Currently, compliance rates for registration are relatively high, but the probability of implementing a draft is considered to be low. If the government tried to reintroduce a registration requirement during a time when conscription were more likely, compliance rates could fall and it might be more difficult to build up a database of eligible individuals. On the other hand, when the registration requirement was reinstated in 1980, the SSS reported 95% compliance rates within four months.175

The 2020 Commission recommend maintaining the pre-mobilization registration system and the SSS infrastructure, based on estimates that it would take 830 to 920 days to bring the SSS out of standby mode and deliver the first inductees.176 If the SSS was maintained and only the registration requirement was repealed, the SSS estimates it would take one year from congressional authorization to deliver the first inductee.177

Transferring SSS Functions to an Existing Federal Agency

Current law states, "the Selective Service System should remain administratively independent of any other agency, including the Department of Defense."178 Nevertheless, Congress could amend the MSSA to transfer its functions to an existing federal agency. Such a transfer might take into account not only the SSS's value as a unique data center, but also the staff who comprise the agency at many levels, who would be needed in case of an actual draft.

As described previously, this staffing includes regional directors and a pool of civilian volunteers that would serve on local draft boards. This responsibility for maintaining volunteer rolls and training could also be transferred to an existing federal agency, potentially the Department of Defense, and the capability could be augmented with military reserve manpower (as is currently done). The statutory independence of the SSS with respect to DOD and the presence of local civilian boards have historically been viewed as important to the public's perception of a fair and equitable draft. To address this concern, some have proposed that administrative responsibilities could be transferred to DOD while the draft is inactive with the option of transferring all functions back to an independent agency if draft authority were reinstated.179

Another option might be to transfer the agency and/or its functions to the Department of Homeland Security. There are potential synergies between the SSS and other DHS agencies that would play an active role in a time of national emergency.180 At least one agency under DHS (USCIS) already has a role in data sharing with the SSS.181