Recent Developments

After more than five years of conflict with Yemeni rivals backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the northern Yemeni-based Ansar Allah/Houthi movement (referred to in this report as "the Houthis") have solidified their power, gained territory, and, with the help of Iran, deployed long-range weaponry that threatens the region. Houthi gains arguably have been abetted by the choices and limitations of their opponents, who in 2019 fractured politically and feuded openly.

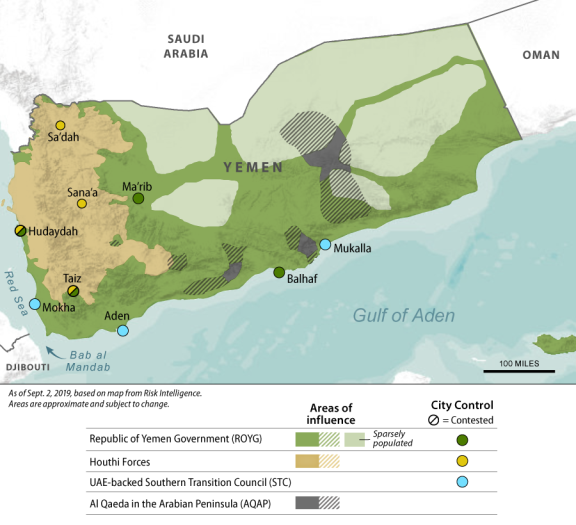

In summer 2019, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), facing a perceived threat from Iran and international criticism of its conduct in Yemen, unilaterally withdrew most of its forces from Yemen. The UAE had been Saudi Arabia's primary partner in a coalition war against the Houthis. The UAE's local partners in southern Yemen, the Southern Transitional Council (STC), attempted to seize more power in Aden from the internationally recognized Republic of Yemen government (ROYG) following the UAE's withdrawal. Violent confrontations ensued between STC and ROYG forces. Although Saudi Arabia and the UAE brokered a power-sharing agreement between the ROYG and the STC in November 2019, implementation of that deal stalled, leaving the STC ensconced in the South, the Houthis controlling the north, and the ROYG isolated.

During winter 2020, amidst the backdrop of this fracturing in the anti-Houthi opposition, the Houthis launched a new offensive into Jawf governorate, where they succeeded in seizing the provincial capital. By April 2020, the Houthis were in position to threaten Marib governorate, one of the last Yemeni areas loyal to the ROYG and where Yemen's modest oil and gas reserves are located. The capture of Marib would represent a major gain for the Houthis. Its seizure also could trigger major internal displacement. According to the International Crisis Group, Marib's population has increased from 300,000 before the war to as many as three million as of March 2020.1

Beyond the ground war in Yemen, the Houthis have continued to intermittently launch missile, rocket, and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)2 attacks against Saudi Arabian population centers and energy infrastructure. After the sophisticated air attacks against Saudi Arabian oil fields of Abqaiq and Khurais in September 2019, attacks widely attributed to Iran but claimed by the Houthis, the Houthis announced that they were suspending missile and UAV attacks against Saudi Arabia. Between September 2019 and January 2020, talks aimed at de-escalating the fighting between the Saudi-led coalition and the Houthis accelerated and were accompanied by several confidence-building measures, such as prisoner exchanges and medical evacuation flights from Sana'a to Amman, Jordan. By late January 2020, the Houthis had resumed their UAV and missile attacks against Saudi Arabia. 3

On March 28, 2020, the Houthis fired missiles at the Saudi capital Riyadh (and elsewhere in the kingdom), and Saudi air defenses reportedly intercepted the projectiles. The remnants of previous Houthi ballistic missile attacks against Saudi Arabia have proven to resemble Iran's Qiam missile, which itself is a modified short-range Scud missile.4 In February 2020, the USS Normandy intercepted a small dhow while on patrol in the Arabian Sea and discovered a cache of Iranian weapons intended for delivery to Yemen; some of the items seized included Iranian made copies of a Russian antitank guided missile, Iranian designed and manufactured surface-to-air missiles, and components for unmanned maritime systems.5

United Nations officials have called for worldwide humanitarian cease-fires in various conflict zones in order to respond to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. On April 8, 2020, Saudi Arabia unilaterally announced a two-week cease-fire in Yemen and a $500 million pledge of humanitarian aid. While Saudi Arabia and the Houthis have been engaged for months in negotiations6 over how to deescalate their conflict, there is some speculation that the demands of limiting the COVID-19 outbreak in the Arabian Peninsula may provide an opportunity for cooperation.7 The kingdom's leaders may wish to limit the risk that conflict could allow COVID-19 to threaten the kingdom from Yemen and may wish to extricate their military from what has become a diplomatically and financially costly campaign. International aid organizations have warned that Yemen is ill-equipped to handle the pandemic, as, according to one report, 51% of health facilities are fully functional, and there are limited supplies of personal protective equipment and few testing sites nationwide.8

Historical Background

For over a decade, the Republic of Yemen Government (ROYG) has been torn apart by multiple armed conflicts to which several internal militant groups and foreign nations are parties. Collectively, these conflicts have eroded central governance in Yemen, and have fragmented the nation into various local centers of power. The gradual dissolution of Yemen's territorial integrity has alarmed the international community and the United States. Policymakers are concerned that state failure may empower Yemen-based transnational terrorist groups; destabilize vital international shipping lanes near the Bab al Mandab strait9 (alt. sp. Bab al Mandeb, Bab el Mendeb); and provide opportunities for Iran to threaten Saudi Arabia's borders. Beyond geo-strategic concerns, the collapse of Yemeni institutions during wartime has exacerbated poor living conditions in what has long been the most impoverished Arab country, leading to what is now considered the world's worst humanitarian crisis.

|

|

Republic of Yemen Government (ROYG) |

|

|

Houthi Forces |

|

|

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) |

|

|

Southern Transitional Council (STC) |

Source: Prepared by CRS.

For over five years, one conflict in particular has garnered the bulk of international attention – the intervention of Saudi Arabia's international coalition against the northern Yemeni-based Ansar Allah/Houthi movement (referred to in this report as "the Houthis"). In 2014, Houthi militants took over the capital, Sanaa (also commonly spelled Sana'a), and in early 2015, advanced southward from the capital to Aden on the Arabian Sea. In March 2015, after President Hadi, who had fled to Saudi Arabia, appealed for international intervention, Saudi Arabia and a hastily assembled international coalition (referred to in this report as "the Saudi-led coalition") launched a military offensive aimed at restoring Hadi's rule and evicting Houthi fighters from the capital and other major cities.10

Now in its sixth year, the war has killed tens of thousands of Yemenis, including civilians as well as combatants, and has significantly damaged the country's infrastructure. One U.S.- and European-funded organization, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), estimated in late 2019 that more than 100,000 Yemenis had been killed since 2015.11

Despite multiple attempts by the United Nations to broker a cease-fire that would lead to a comprehensive settlement to the conflict, the parties continue to hinder diplomatic progress. In December 2018, the Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary-General for Yemen Martin Griffiths brokered a cease-fire, known as the Stockholm Agreement, centered on the besieged Red Sea port city of Hudaydah (alt. sp. Hodeidah, Al Hudaydah). Over a year later, the agreement remains unfulfilled and, though fighting around Hudaydah has subsided, other fronts have intensified.

Although media coverage since the 2015 Saudi-led intervention has tended to focus on the binary nature of the war (the Saudi-led coalition versus the Houthis), there have been a multitude of combatants whose alliances and loyalties have been somewhat fluid. In summer 2019 in southern Yemen, long-simmering tensions between the ROYG and the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a southern Yemeni separatist group backed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), boiled over, leading to open warfare between the local allies of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Many foreign observers have denounced human rights violations that they charge have been committed by all parties to the conflict, with particular attention paid in the United States and other Western countries to errant coalition air strikes against civilian targets. Some lawmakers have proposed legislation to limit U.S. support for the coalition, while others have highlighted Iran's support for the Houthis as a major factor in Yemen's destabilization. The Trump Administration continues to call for a comprehensive settlement to the conflict in line with in line with relevant resolutions of the United Nations Security Council and other international initiatives.

For Saudi Arabia, according to one prominent analyst, the Houthis embody what Iran seeks to achieve across the Arab world: that is, the cultivation of an armed non-state, non-Sunni actor who can pressure Iran's adversaries both politically and militarily (akin to Hezbollah in Lebanon).12 A decade before the current conflict began in 2015, Saudi Arabia supported the central government of Yemen in various military campaigns against a Houthi insurgency, which began in 2004.13 The Houthis rejected what they viewed as hostile, Saudi-supported proselytization efforts in northern Yemen.14

|

Who are the Houthis? The Houthi movement (also known as Ansar Allah or Partisans of God) is a predominantly Zaydi Shiite revivalist political and insurgent movement. Yemen's Zaydis take their name from their fifth Imam, Zayd ibn Ali, grandson of Husayn, son of Ali (the cousin and son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad). Zayd revolted against the Umayyad Caliphate in 740 C.E., believing it to be corrupt, and to this day, Zaydis believe that their imam (ruler of the community) should be both a descendent of Ali and one who makes it his religious duty to rebel against unjust rulers and corruption. A Zaydi state (or Imamate) was founded in northern Yemen in 893 C.E. and lasted in various forms until the republican revolution of 1962. Yemen's modern imams kept their state in the Yemeni highlands in extreme isolation, as foreign visitors required the ruler's permission to enter the kingdom. Although Zaydism is an offshoot of Shia Islam, it is doctrinally distinct from "Twelver Shiism," the dominant branch of Shia Islam in Iran and Lebanon. Zaydism's legal traditions and religious practices are more similar to Sunni Islam. The Houthi movement was formed in the northern Yemeni governorate of Sa'dah (in the mountainous district of Marran) in 2004 under the leadership of members of the Houthi family. Between 2004 and 2010, the central government and the Houthis fought six wars in northern Yemen. With each successive round of fighting, the Houthis improved their position, as anti-government sentiment became more widespread amidst an aggrieved population in a war-torn and neglected north. Although the Houthi movement originally sought an end to what it viewed as Saudi-backed efforts to marginalize Zaydi communities and beliefs, its goals grew in scope and ambition in the wake of the 2011 uprising and government collapse to embrace a broader populist, anti-establishment message. Ideologically, the group has espoused anti-American and anti-Zionist beliefs, embodied by the slogans prominently displayed on its banners: "God is great! Death to America! Death to Israel! Curse the Jews! Victory to Islam!" |

From the outset of the Saudi-led coalition intervention, Saudi leaders sought material and military support from the United States for the campaign. In March 2015, President Obama authorized "the provision of logistical and intelligence support to GCC-led military operations," and the Obama Administration announced that the United States would establish "a Joint Planning Cell with Saudi Arabia to coordinate U.S. military and intelligence support." U.S. CENTCOM personnel were deployed to provide related support, and U.S. mid-air refueling of coalition aircraft began in April 2015 and ended amid intense congressional scrutiny in November 2018.15

Since 2015, the Saudi military and its coalition partners have waged a persistent air campaign against the Houthis and their allies. This air campaign has at times drawn international criticism for growing civilian casualties from coalition air strikes. According to a U.N Human Rights Council Report on Yemen, which found human rights violations on all sides of the conflict between 2018 and 2019, despite "reported reductions in the overall number of airstrikes and resulting civilian casualties, the patterns of harm caused by airstrikes remained consistent and significant."16

Issues for Congress

Humanitarian Access in Northern Yemen

As the Houthis have become further ensconced in northern Yemen and placed key members in positions of authority, Houthi restrictions on humanitarian aid agencies working in northern Yemen have grown more onerous.17 Throughout 2019, the Houthis clashed with the World Food Programme (WFP) over the WFP's implementation of a biometric tracking system to prevent the misdirection of food aid.18 Two months after the WFP partially suspended food aid in northern Yemen in June 2019, the Houthis permitted the biometric system to be put in place; however, since then they have continued to block its full implementation. As a result, in some cases, food deliveries have been delayed, leading to the spoilage of supplies in warehouses. Control and diversion of aid is one means Houthi forces, Houthi partners, and other parties to the conflict have used to finance their operations.19

In November 2019, the Houthis issued Decree 201, creating the "Supreme Council for Management, Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, International Cooperation (SCMCHA)." This new governing body then conditioned the renewal of international aid operating agreements on certain provisions, such as decreeing that 2% of the budget of each humanitarian project approved would finance the SCMCHA, a clause widely rejected by international aid organizations.

In 2020, as international frustration over Houthi obstruction of humanitarian assistance has mounted, the international community has warned that if the Houthis do not abide by the principles of international humanitarian law and allow for unimpeded access for humanitarian assistance, they will risk losing aid. In February 2020, the European Commission and Sweden hosted a conference on the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, in which participants agreed that without significant change in Houthi behavior, the international community would downsize or cease certain humanitarian operations.20

The Trump Administration has supported international attempts to pressure the Houthis to abide by international humanitarian law. On March 24, 2020, USAID initiated a partial suspension of its funding to support humanitarian operations in northern Yemen. The suspension followed several weeks of warnings from U.S. officials that the Administration was extremely concerned over Houthi obstruction of aid. In February 2020, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Kelly Craft remarked:

The United States is also extremely concerned by mounting Houthi interference with the work of aid partners in northern Yemen, which limits the ability of the UN and other humanitarian organizations to deliver assistance to the most vulnerable Yemenis. Houthi actions – including imposition of a 2-3 percent per project levy – amount to a flagrant rejection of a principled humanitarian response….In light of these entirely avoidable circumstances, donors are faced with the difficult dilemma of how to continue delivering aid while remaining responsive to taxpayers. We may be forced to consider suspending or reducing our assistance in northern Yemen as early as March unless undue Houthi interference ceases immediately and access to vulnerable populations improves.21

As of April 2020, USAID has continued its partial suspension of humanitarian programming in Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen. As a result of U.S. and other international suspensions, the WFP has said it would halve its food aid to recipients in Houthi-controlled areas. Some Members of Congress have called on the Trump Administration to step up its role in resolving the standoff between the Houthis and international aid agencies. In February 2020, several Senators wrote a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo asking him to take a more active role in "ensuring the unimpeded, accountable, and impartial flow of assistance and commerce into Yemen."22 A month later, a bipartisan group of House Members demanded that Secretary Pompeo not suspend aid in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and other humanitarian considerations.23

Iranian Support to the Houthis

Iranian knowledge transfer and military aid to the Houthis, in violation of the targeted international arms embargo (see U.N. Security Council Resolution 2216), has increased the Houthi's ability to threaten Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations. According to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, Houthis continued to receive "military support in the form of assault rifles, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, anti-tank guided missiles and more sophisticated cruise missile systems. Some of those weapons have technical characteristics similar to arms manufactured in the Islamic Republic of Iran."24

The Houthis employ a variety of weapons to project power near and beyond Yemen's land and maritime borders, including:

- Short-range Ballistic Missiles - According to various sources, the Houthis have modified Iranian "Qiam" short-range 'Scud' missiles to boost their ranges in order to threaten Saudi cities, such as the capital Riyadh. 25 In May 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated five Iranian individuals who have "provided ballistic missile-related technical expertise to Yemen's Houthis, and who have transferred weapons not seen in Yemen prior to the current conflict, on behalf of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF)."26

- UAVs – Beginning in 2018, the Houthis began using UAVs to deliver and detonate explosive payloads against ROYG and Saudi targets. According to Jane's Intelligence Weekly, Houthis UAV capabilities gained "increased support from Iran in terms of the supply of technology and military trainers dispatched to Yemen."27 The U.N. Panel of Experts on Yemen reported in January 2019 that the panel "has traced the supply to the Houthis of unmanned aerial vehicles and a mixing machine for rocket fuel and found that individuals and entities of Iranian origin have funded the purchase." 28

- Surface-to-Air-Missiles (SAMs) – In February 2020, the U.S. Navy revealed that an intercepted Iranian weapons shipment to the Houthis contained a long-range air-breathing SAM that could loiter in a designated target area.29

- Anti-Ship Missiles, Drone Boats, and Sea Mines – The Houthis have developed various anti-ship capabilities that can threaten Saudi-led coalition ships enforcing a maritime blockade against Yemen.30 In February 2020, CENTCOM discovered that in addition to the previously mentioned weapons seized by the U.S. Navy, Iran also had shipped Iranian "Noor" anti-ship cruise missiles (anti-ship missiles based on the Chinese C-802 missile) to the Houthis. . The Houthis also have repeatedly built remote controlled Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs) also known as Waterborne Improvised Explosive Devices (WBIEDs) using Iranian components.31

|

Countering Iranian influence in Yemen: Recent U.S. Policy32 U.S. policymakers have pursued several different lines of effort to counter Iranian influence in Yemen, as part of the Trump Administration's maximum pressure campaign against Iran. Since the start of the Saudi-led coalition's 2015 intervention, U.S. naval forces from the Central Command/5th Fleet, in support of international efforts to enforce a targeted arms embargo, have repeatedly intercepted vessels carrying smuggled Iranian arms destined for the Houthis off the coast of Yemen.33 In summer 2019, President Trump ordered the deployment of a Patriot air defense battery to Prince Sultan Air Base in central Saudi Arabia. According to the State Department, "We stand firmly with our Saudi partners in defending their borders against these continued threats by the Houthis, who rely on Iranian-made weapons and technology to carry out such attacks."34According to one report, on the same day the United States killed Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF) Commander Qasem Soleimani, the United States also unsuccessfully targeted IRGC-QF leader Abdul Reza Shahlai, who was based in Yemen.35 The operation came a few weeks after the U.S. State Department announced a $15 million reward for information leading to Shahlai's capture. U.S. policymakers have repeatedly portrayed Iran as a spoiler in Yemen, bent on sabotaging peace efforts by lending support to Houthi attacks against Saudi Arabia. Like its other proxy groups (e.g., Hezbollah), Iran uses its relationship with the Houthis to project power in the region as part of Tehran's broader national security strategy. As Saudi Arabia has more directly engaged Houthi leadership in peace talks, U.S. officials have indicated that the Houthis are independent political actors and are not beholden to Iran. According to U.S. Special Representative for Iran Brian Hook, "The Houthis' de-escalation proposal, which the Saudis are responding to, shows that Iran clearly does not speak for the Houthis, nor has the best interests of the Yemeni people at heart…. Iran is trying to prolong Yemen's civil war to project power. Iran should follow the calls of its own people and end its involvement in Yemen."36 In April 2020, U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo spoke with Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud regarding Yemen in which both ministers agreed that an "unstable Yemen only benefits the Iranian regime and that the regime's destabilizing behavior there must be countered."37 |

U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Yemen

According to President Trump's December 2019 report to Congress on the deployment of U.S. Armed Forces abroad, "A small number of United States military personnel are deployed to Yemen to conduct operations against al-Qa'ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and ISIS. The United States military continues to work closely with the Republic of Yemen Government (ROYG) and regional partner forces to degrade the terrorist threat posed by those groups. Since the last periodic update report, United States military forces conducted one airstrike against AQAP operatives and facilities in Yemen."38

Throughout the Yemen crisis the United States has sustained counterterrorism operations against various U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations. Over the past year, U.S. forces, at times working with Saudi Arabia and the ROYG, have eliminated or captured the leaders of both AQAP and the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State. On February 6, 2020, the White House issued a statement that U.S. forces had killed the current leader and one of the founders of AQAP, 41-year-old Qasim al Rimi (alt. sp. Raimi or Raymi).39 In April 2012, U.S. forces reportedly carried out a missile strike against Al Rimi, then-the third-highest member of AQAP, but missed his vehicle.40

The announcement of Rimi's death came several days after Rimi released an audiovisual message claiming that AQAP was responsible for the December 2019 attack at the Naval Air Station Pensacola in Pensacola, Florida, in which a Saudi soldier studying there killed three U.S. sailors. While the exact role of AQAP in the Florida attack is unknown, according to one report, AQAP's ability to directly carry out attacks abroad has diminished due to U.S. counterterrorism efforts; therefore the group has shifted focus onto "inspiring rather than directing attacks."41

In June 2019, Saudi Arabia and ROYG troops captured the leader of the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State in the far eastern governorate of Al Mahra. Reportedly, the United States played an "advise and assist" role during the operation.42

To date, two U.S. soldiers have died in the ongoing counterterrorism campaign against AQAP and other terrorists inside Yemen. In January 2017, Ryan Owens, a Navy SEAL, died during a counterterrorism raid in which between 4 and 12 Yemeni civilians also were killed, including several children, one of whom was a U.S. citizen. The raid was the Trump Administration's first acknowledged counterterror operation. In August 2017, Emil Rivera-Lopez, a member of the elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, died when his Black Hawk helicopter crashed off the coast of Yemen during a training exercise.

According to one study, since 2002, the United States has conducted 372 air, drone, or ground operation strikes against terrorist targets in Yemen, killing an estimated 1,374– 1,771 militants and 115– 149 civilians.43 Among those militants killed were high-value targets such as AQAP leader Qasim al Rimi (2020); AQAP bomb maker Ibrahim al Asiri, (2018); AQAP leader Nasser al Wuhayshi (2015); USS Cole bomber Fahd al Quso (2012), and AQAP cleric/U.S.-citizen Anwar al Awlaki (2011).

Possible Illegal Transfer of U.S. Weaponry in Yemen

Congress has long taken an interest in ensuring that arms sold to foreign countries are used responsibly and for the purposes agreed on as part of their sale.44 In February 2019, CNN reported that Saudi Arabia and the UAE had provided U.S. military equipment (armored vehicles) to local Yemeni units fighting the Houthis in possible violation of end-user provisions in foreign military sale or direct commercial sale agreements.45 The coalition denied these charges, while the State Department said that it was "seeking additional information" on the issue. In Senate and House hearings in early February 2019, some Members expressed concern about end-use monitoring of equipment provided to the coalition.46 In October 2019, CNN published another article alleging that the UAE had illegally transferred U.S.-made Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles to the STC.47 A third piece, published a month later by CNN, which depicted video footage of MRAPs being offloaded in Aden, elicited a response from an unnamed State Department official who remarked that "there is currently no U.S. prohibition on the use of U.S.-origin MRAPs by Gulf coalition forces in Yemen."48

Per Section §3(a) of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA - 22 U.S. Code §2753) and Section 505(e) of the Foreign Assistance Act (22 U.S. Code §2314), the U.S. government must review and approve any transfer of U.S.-origin equipment from a recipient to a third party that was not previously authorized in the original acquisition.49 Third Party Transfer (or TPT) is the retransfer of title, physical possession or control of defense articles from the authorized recipient to any person or organization that is not an employee, officer or agent of that recipient country.50 U.S. origin defense articles sold via FMS and DCS are subject to end-use monitoring (EUM) to ensure that recipients use such items solely for their intended purposes.51 DOD's Defense Security Cooperation Agency manages the department's Golden Sentry EUM program for defense articles sold via FMS. The State Department's Directorate of Defense Trade Controls coordinates the Blue Lantern program, which performs an analogous function for items sold via DCS.

For lawmakers, the definition of the "end-user" is at issue in Yemen. Saudi Arabia and the UAE claim that U.S.-purchased weapons used in Yemen have remained in their control in accordance with U.S. law and relevant bilateral agreements. According to Saudi-led coalition spokesperson Col. Turki Al Maliki, "the information that the military equipment will be delivered to a third party is unfounded…. all military equipment is used by Saudi forces in accordance with term and conditions of Foreign Military Sales (FMS) adopted by the US government and in pursuance of the Arms Export Control Act."52

Several Members of Congress have followed up on CNN's investigations with legislative inquiries. Senator Elizabeth Warren has sent several letters to the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of State requesting information regarding the reported transfer of American weapons from the Saudi-led coalition to armed Yemeni militias, such as the STC.53 In September 2019, the Senate Appropriations Committee adopted an amendment by voice vote and incorporated it into Section 9018 of S. 2474, the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2020, which would have prohibited defense funds from being used to support the Saudi-led coalition air campaign in Yemen until the Secretary of Defense certifies that the Saudi-led coalition is in "compliance with end-use agreements related to sales of United States weapons and defense articles;" and submits to Congress any written findings of "any internal Department of Defense investigation into unauthorized third-party transfers of United States weapons and defense articles in Yemen and has taken corrective action as a result of any such investigation." P.L. 116-93, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, which incorporated S. 2474, did not include Section 9018.

The Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen

The humanitarian situation in Yemen was dire before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the outbreak has made the situation worse in several ways. Before the outbreak, the United Nations had described Yemen's humanitarian crisis as the worst in the world, with close to 80% of Yemen's population of nearly 30 million needing some form of assistance.54 Over 17 million Yemenis are in need of food assistance. Moreover, the depreciation of the Yemeni riyal (YER) has led to increases in food prices at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has hampered global trade. Yemen is dependent on food imports for 90% of its grain and other food sources.

The COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with Houthi obstruction of humanitarian aid, has prevented international aid agencies from formulating the 2020 Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan and convening donor conferences to raise funds. Currently, aid organizations are carrying over programs from the 2019 response plan.

Since 2015, the United States has provided over $2.4 billion in emergency humanitarian aid for Yemen (see Table 1 below). Most of these funds are provided through USAID's Office of Food for Peace to support the World Food Programme in Yemen.

Table 2. U.S. Humanitarian Response to the Complex Crisis in Yemen:

FY2015-FY2019

(in millions of U.S. dollars)

|

Account |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

IDA (USAID/OFDA) |

62.030 |

81.528 |

229.783 |

179.065 |

102.058 |

|

FFP (UDAID/FFP) |

71.486 |

196.988 |

369.629 |

368.243 |

594.548 |

|

MRA (State/PRM) |

45.300 |

48.950 |

38.125 |

18.900 |

49.800 |

|

Total |

178.816 |

327.466 |

637.537 |

566.208 |

746.406 |

Source: Yemen, Complex Emergency—USAID Factsheets.

One of the key aspects of the 2015 UNSCR 2216 is that it authorizes member states to prevent the transfer or sale of arms to the Houthis and also allows Yemen's neighbors to inspect cargo suspected of carrying arms to Houthi fighters. In March 2015, the Saudi-led coalition imposed a naval and aerial blockade on Yemen, and ships seeking entry to Yemeni ports required coalition inspection, leading to delays in the off-loading of goods and increased insurance and related shipping costs. Since Yemen relies on foreign imports for as much as 90% of its food supply, disruptions to the importation of food exacerbate already strained humanitarian conditions resulting from war.

To expedite the importation of goods while adhering to the arms embargo, the European Union, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States formed the U.N. Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM), a U.N.-led operation designed to inspect incoming sea cargo to Yemen for illicit weapons. UNVIM, which began operating in February 2016, is intended to inspect cargo while also ensuring that humanitarian aid is delivered in a timely manner.

However, Saudi officials argue that coalition-imposed restrictions and strict inspections of goods and vessels bound for Yemen are still required because of Iranian weapons smuggling to Houthi forces. Saudi officials similarly argue that the delivery of goods to ports and territory under Houthi control creates opportunities for Houthi forces to redirect or otherwise exploit shipments for their material or financial benefit.55

U.S. Bilateral Aid to Yemen

Since the current conflict began in March 2015, the United States has increased its humanitarian assistance to Yemen while limiting nearly all other bilateral programming. On February 11, 2015, due to the deteriorating security situation in Sana'a, the State Department suspended embassy operations and U.S. Embassy staff was relocated to Saudi Arabia.

Over the past few years, USAID has managed an economic assistance portfolio of $25-$30 million. It has focused its programming on the health, education, and financial sectors. In the health sector, USAID has supported programs for providing polio surveillance, reducing child mortality, and providing basic access to health care. In the education sector, USAID funds programs to expand access to education to meet the needs of crisis-affected children. In the financial sector, USAID has worked with The Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) to ensure that the CBY can continue paying public sector salaries and managing the treasury.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the FY2020 Foreign Operations Appropriations Act (Division G of P.L. 116-94) directs that $40 million in funding made available by the act and prior acts be used "for stabilization assistance for Yemen, including for a contribution for United Nations stabilization and governance facilities, and to meet the needs of vulnerable populations, including women and girls."

|

Account |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 est. |

FY2021 Request |

|

ESF |

70.0 |

40.0 |

25.0 |

32.0 |

29.6 |

26.350 |

|

FMF |

25.0 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

GHP-USAID |

9.5 |

9.0 |

3.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

|

IMET |

1.4 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

INCLE |

2.0 |

1.0 |

– |

.300 |

.300 |

– |

|

NADR |

6.5 |

5.884 |

6.5 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

4.6 |

|

Total |

114.400 |

55.884 |

35.000 |

43.400 |

41.400 |

36.450 |

Source: Congressional Budget Justifications, USAID notifications, and CRS calculations.

Note: In FY2019, Yemen received $21.5 million in ESF-OCO from the Relief and Recovery Fund.

Outlook

As foreign officials call for a nationwide cease-fire amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the conflict in Yemen could change significantly if the Houthis ignore such calls. Should the Houthis lay siege to Marib and its eponymous provincial capital, the balance of power on the ground could be poised to change. If Marib falls, the ROYG would lose its presence in northern Yemen and, with its presence in southern Yemen already tenuous and President Hadi in ill-health, the ROYG's status as a government in-exile would be cemented. Moreover, the Houthis would be in a much stronger negotiating position vis-à-vis the Saudis should their de-escalatory talks continue. For the United States, it would appear that for the time being and without a political settlement to the conflict, the prospect of diminishing Iran's relationship with the Houthis remains distant; however, deterrence in the form of a continued U.S. military presence in the region may be sufficient to limit further escalation.

In the meantime, the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to further devastate the country's already vulnerable population. Half of the country's medical facilities are either closed or partially functioning due to damage from the war, neglect, or lack of basic infrastructure such as running water and electricity. In war-torn Taiz, Yemen's third largest city, all hospitals combined possess four ventilators.56 Nationwide, Yemen has several hundred ventilators to serve a population of 30 million. Since 2015, the United States has provided over $2.4 billion in emergency humanitarian aid for Yemen. In the coming months, the United States and international community are expected to increase assistance to Yemen to cope with the pandemic. In late April 2020, the International Initiative on COVID-19 in Yemen (IICY) announced that it had shipped "49,000 virus collection kits, 20,000 rapid test kits, five centrifuges and equipment that would enable 85,000 tests, and 24,000 COVID-19 nucleic acid test kits."57 Also in late April, one unnamed State Department official remarked that "We are trying to get some funding into Yemen for COVID-19 countermeasures. We have the tranche underway that would hopefully make it possible…. It would be a substantial contribution…"58