Introduction

The United Nations (U.N.) Human Rights Council (the Council) is the primary intergovernmental body that addresses human rights worldwide. The United States is not currently a Council member; in June 2018, the Trump Administration announced that the United States would withdraw its membership. Administration officials cited concerns with the Council's disproportionate focus on Israel, ineffectiveness in addressing human rights situations, impact on U.S. sovereignty, and lack of reform. The United States is currently withholding funding to the Council under a provision in the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Act, FY2019 (Division F of P.L. 116-6.)1 As of March 13, 2020, some Human Rights Council activities are suspended or being conducted remotely due to COVID-19.2

Members of the 116th Congress may continue to consider the Council's role and effectiveness, including what impact, if any, the U.S. withdrawal might have on (1) the Council's efforts to combat human rights and (2) the United States' ability to further its human rights objectives in U.N. fora. Policymakers might also consider the following questions:

- What role, if any, should the Council play in international human rights policy and in addressing specific human rights situations?

- Is the Council an effective mechanism for addressing human rights worldwide? If not, what reform measures might improve the Council and how can they be achieved?

- What role, if any, might the United States play in the Council, or in other U.N. human rights mechanisms, moving forward?

- Should the United States rejoin the Council? If so, under what circumstances?

This report provides background information on the Council, including the role of the previous U.N. Commission on Human Rights. It discusses the Council's current mandate and structure, as well as Administration policy and congressional actions. Finally, it highlights policy aspects of possible interest to the 116th Congress, including the debate over U.S. membership, U.S. funding of the Council, alternatives to the Council in U.N. fora, the Council's focus on Israel, and the possible increased influence of other countries in Council activities.

Background

The U.N. Commission on Human Rights was the primary intergovernmental policymaking body for human rights issues before it was replaced by the U.N. Human Rights Council in 2006. Created in 1946 as a subsidiary body of the U.N. Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), the commission's initial mandate was to establish international human rights standards and develop an international bill of rights.3 During its existence, the commission played a key role in developing a comprehensive body of human rights treaties and declarations, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Over time, its work evolved to address specific human rights violations and complaints, as well as broader human rights issues. It developed a system of special procedures to monitor, analyze, and report on country-specific human rights violations, as well as thematic cross-cutting human rights abuses such as racial discrimination, religious intolerance, and denial of freedom of expression.4

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, controversy developed over the human rights records of some commission members that were widely perceived as systematic abusers of human rights.5 These instances significantly affected the commission's credibility. Critics, including the United States, claimed that countries used their membership to deflect attention from their own human rights violations by questioning the records of others. Some members were accused of bloc voting and excessive procedural manipulation to prevent debate of their human rights abuses. In 2001, the United States was not elected to the commission, whereas widely perceived human rights violators such as Pakistan, Sudan, and Uganda were elected.6 In 2005, the collective impact of these and other controversies led U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan to propose the idea of a new and smaller Human Rights Council to replace the commission.

Council Structure and Selected Policy Issues

In 2006, as part of broader U.N. reform efforts, the U.N. General Assembly approved resolution 60/251, which dissolved the U.N. Commission on Human Rights and created the Human Rights Council in its place. This section provides an overview of Council structure and selected policy issues and concerns that have emerged over the years.

Mandate and Role in the U.N. System

The Council is responsible for "promoting universal respect for the protection of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all."7 It aims to prevent and combat human rights violations, including gross and systematic violations, and to make recommendations thereon; it also works to promote and coordinate the mainstreaming of human rights within the U.N. system. As a subsidiary of the General Assembly, it reports directly to the Assembly's 193 members. It receives substantive and technical support from the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), an office within the U.N. Secretariat currently headed by Michelle Bachelet of Chile.8 The Council is a political body; each of its members has different human rights preferences, domestic considerations, and foreign policy priorities. Its decisions, resolutions, and recommendations are not legally binding. At the same time, Council actions sometimes hold political weight and represent the Council's human rights perspectives and priorities.

Membership and Elections

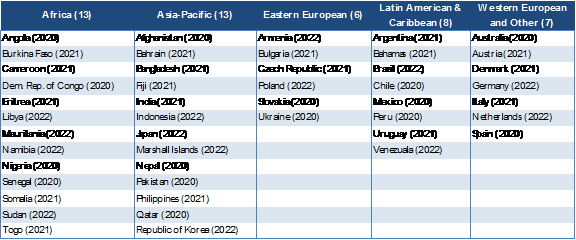

The Council comprises 47 members apportioned by geographic region as follows: 13 from African states; 13 from Asian states; 6 from Eastern European states; 8 from Latin American and Caribbean states; and 7 from Western European and other states (Figure 1). Members are elected for a period of three years and may not hold a Council seat for more than two consecutive terms. If a Council member commits "gross and systematic violations of human rights," the General Assembly may suspend membership with a two-thirds vote of members present.9 All U.N. members are eligible to run for a seat on the Council. Countries are nominated by their regional groups and elected by the General Assembly through secret ballot with an absolute majority required. The most recent election was held in October 2019; the next election is scheduled for late 2020. As of January 2020, 117 of 193 U.N. member states have served as Council members.

|

|

Source: U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Notes: Dates represent year of term end. |

A key concern for some critics has been the composition of Council membership, which sometimes includes countries widely perceived as human rights abusers. Many view the lack of competitiveness in Council elections as a key reason for this dynamic. In some elections, countries have run unopposed after regional groups nominated the exact number of countries required to fill Council vacancies. (For instance, in the 2018 election members from all five regional groups ran unopposed. In the 2019 election, members from two regional groups ran unopposed.) Many experts contend that such circumstances limit the number of choices and guarantee the election of nominated members regardless of their human rights records.10 On the other hand, supporters contend that the Council's election process is an improvement over that of the commission. They emphasize that countries widely viewed as the most egregious human rights abusers, such as Belarus, Russia, Sudan, and Syria, were pressured not to run or were defeated in Council elections because of the new membership criteria and process. Many also highlight the General Assembly's March 2011 decision to suspend Libya's membership as an example of improved membership mechanisms.11

More broadly, some Council observers have expressed concern that the Council's closed ballot elections in the General Assembly may make it easier for countries with questionable human rights records to be elected to the Council. To address this issue, some experts and policymakers, including the Trump Administration, have proposed requiring open ballots in Council elections to hold countries publicly accountable for their votes.12 Some have also suggested lowering the two-thirds vote threshold to make it easier to remove a Council member.13

Meetings and Leadership

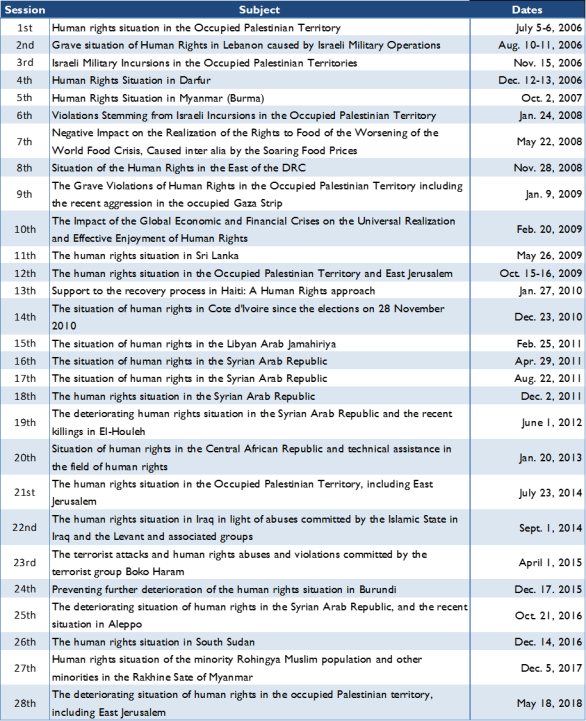

The Council is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, and meets for three or more sessions per year for a total of 10 or more weeks. It can hold special sessions on specific human rights situations or issues at the request of any Council member with the support of one-third of the Council membership. Since 2006, the Council has held 43 regular sessions and 28 special sessions. Eight of its special sessions have focused on Israel or the Occupied Territories. (See Appendix A for a list of special sessions.)

The Council president presides over the election of four vice presidents representing regional groups in the Council. The president and vice presidents form the Council bureau, which is responsible for all procedural and organizational matters related to the Council. Members elect a president from among bureau members for a one-year term. The current president is Elisabeth Tichy-Fisslberger of Austria.

Universal Periodic Review

All Council members and U.N. member states are required to undergo a Universal Periodic Review (UPR) that examines a member's fulfillment of its human rights obligations and commitments.14 The review is an intergovernmental process that facilitates an interactive dialogue between the country under review and the UPR working group, which is composed of the 47 Council members and chaired by the Council president. Observer states and stakeholders, such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), may also attend the meetings and present information. During the first review, the UPR working group makes initial recommendations, with subsequent reviews focusing on the implementation of previous recommendations. The full Council is responsible for addressing any cases of consistent noncooperation with the review. The United States underwent its first UPR in November 2010 and its second in May 2015.15 It is scheduled to undergo its third review on May 11, 2020; the extent of U.S. participation, if any, remains unclear.

Perspectives on the effectiveness of the UPR are mixed. Overall, many governments, observers, and policymakers support the Council's UPR process. They maintain that it provides an important forum for governments, NGOs, and others to discuss and bring attention to human rights situations in specific countries that may not otherwise receive international attention. Some countries have reportedly made commitments based on the outcome of the UPR process.16 Many NGOs and human rights groups operating in various countries also reportedly use UPR recommendations as a political and diplomatic tool for strengthening human rights. At the same time, some human rights experts have been critical of UPR. Many are concerned that the submissions and statements of governments perceived to be human rights abusers are taken at face value rather than being challenged by other governments. Some also contend that the process gives these same countries a platform to criticize countries that may have generally positive human rights records. Many experts have also expressed concern regarding some member states' rejection of UPR recommendations and nonparticipation in the UPR process.17

Special Procedures

The Council maintains a system of special procedures that are created and renewed by members. Country mandates allow for special rapporteurs to examine and advise on human rights situations in specific countries, including Cambodia, North Korea, and Sudan.18 Under thematic mandates, special rapporteurs analyze major global human rights issues, such as arbitrary detention, the right to food, and the rights of persons with disabilities. The Council also maintains a complaint procedure for individuals or groups to report human rights abuses in a confidential setting.19

Israel as a Permanent Agenda Item

Israel is the only country to be included as part of the Council's permanent agenda. In June 2007, Council members adopted a resolution to address the Council's working methods. In the resolution, Council members included the "human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories" as a permanent part of the Council's agenda.20 At the time the agenda item was adopted, many U.N. member states and Council observers, including the United States, strongly objected to the Council focusing primarily on human rights violations by Israel.21 A U.N. spokesperson subsequently noted then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon's "disappointment" with the Council's decision to "single out only one specific regional item, given the range and scope of allegations of human rights violations throughout the world."22 Over the years, the United States and other like-minded Council members have made unsuccessful efforts to reverse the Council's decision, particularly during the Council's five-year review in 2011.23 The Trump Administration has cited Israel's removal from the Council's permanent agenda as a condition for the United States rejoining the Council.24

Budget

The Human Rights Council is funded primarily through the U.N. regular budget, of which the United States is assessed 22%. Estimated Council funding for the 2020 regular budget calendar year is $21.8 million, which was similar to the 2019 funding level of $21.7 million. The Council also receives extrabudgetary (voluntary) funding to help cover the costs of some of its activities, including staff postings and Council trust funds and mechanisms. For 2020, such contributions are estimated at $12 million, compared with the 2019 amount of $11.4 million.25 The United States is currently withholding a proportionate share (22%) of Council funding. (For more information, see the "U.S. Policy"section below.)

U.S. Policy

Most U.S. policymakers have generally supported the Council's overall purpose and mandate; however, many have also expressed concern regarding its effectiveness in addressing human rights issues—leading to ongoing disagreements as to whether or not the United States should be a member of or provide funding for the Council. For example, under President George W. Bush, the United States voted against the Assembly resolution creating the Council and did not run for a seat, arguing that the Council lacked mechanisms for maintaining credible membership. (The George W. Bush Administration also withheld Council funding in FY2008 under a provision enacted by Congress in 2007.) On the other hand, the Obama Administration supported U.S. membership and Council funding, maintaining that it was better to work from within to improve the body; the United States was elected as a Council member in 2009, 2012, and 2016.26 Under President Obama, the United States consistently opposed the Council actions related to Israel and sought to adopt specific reforms during the Council's five-year review in 2011.27 Congressional perspectives on the issue have been mixed, with some Members advocating continued U.S. participation and others opposing it. A key concern among many Members of Congress is the Council's focus on Israel. During the past several fiscal years, Congress has enacted a provision in annual State-Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) legislation that prohibits Council funding unless the Secretary of State determines that U.S. participation is important to the national interest of the United States and that the Council is taking steps to remove Israel as a permanent agenda item.

Trump Administration Actions

On June 18, 2018, then-U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations Nikki Haley and Secretary of State Michael Pompeo announced that the United States would withdraw from the Human Rights Council, citing concerns about U.S. sovereignty and the Council's disproportionate focus on Israel.28 In a September 2018 speech to the U.N. General Assembly, the President further stated that the United States "will not return [to the Council] until real reform is enacted."29 Although Administration officials stated that the United States would fully withdraw from the Council, the United States has continued to participate in some Council activities, including the UPR process.30 Administration officials have also commented on Council elections and expressed support for continued reform of the organization.31 Since FY2017, the Trump Administration has withheld Council funding under aforementioned legislation enacted by Congress ($7.53 million in FY2019 and $7.67 million in FY2018).32 A decision has not been made about FY2020 funding.

Prior to withdrawing from the Council, the Trump Administration had expressed strong reservations regarding U.S. membership.33 It was particularly concerned with the Council's focus on Israel and lack of attention to other human rights abuses. Ambassador Haley called the Council "corrupt" and noted that "bad actors" are among its members; at the same time, she also stated that the United States wanted to find "value and success" in the body.34 In June 2017, Haley announced that if the Council failed to change, then the United States "must pursue the advancement of human rights outside of the Council."35 Haley outlined two key U.S. reform priorities: (1) changing the voting process in the General Assembly from a closed to open ballot so that countries can be held publicly accountable for their votes and (2) removing Israel as a permanent agenda item.

Congressional Actions

Congress maintains an ongoing interest in the credibility and effectiveness of the Council in the context of human rights promotion, U.N. reform, and concerns about the Council's focus on Israel. Over the years, some Members have proposed or enacted legislation expressing support for or opposition to the Council, prohibiting U.S. Council funding, or supporting Council actions related to specific human rights situations. Most recently, Members of the 116th Congress enacted a provision in the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94), which requires that none of the funds appropriated by the act be made available for the Council unless the Secretary of State determines and reports to the committees on appropriations that participation in the Council is in the national interest of the United States, and that the Council is taking significant steps to remove Israel as a permanent agenda item and ensure integrity in the election of Council members. (Similar language was included in previous fiscal years' appropriations laws.)36 In addition, Congress has enacted Council-related provisions in the context of country-specific human rights situations.37

In previous Congresses, proposed stand-alone bills have called for U.S. withdrawal from the Council or required that the United States withhold assessed contributions to the Council through the U.N. regular budget and any voluntary contributions.38 Specifically, some Members of the 115th Congress introduced legislation expressing concern with the Council's focus on Israel, seeking to defund or withdraw from the Council, and calling on the Council to take action on specific human rights situations.39

Selected Policy Issues

Congressional debate regarding the U.N. Human Rights Council has generally focused on a recurring set of policy issues.

U.S. Membership

|

Council Observer Status When considering U.S. membership, Members of Congress may take into account the role of Council observer, a status that the United States could hold as a non-Council member. Observer states are not eligible to vote in the Council, but they may participate in the UPR process and attend and participate in regular and special sessions of the Council. The ability of the United States to promote its human rights agenda within the U.N. framework may be significantly affected by changing to an observer status. Many Council members might be interested in U.S. statements and policies, but the United States' inability to vote may diminish its influence on the work of the Council. |

In general, U.S. policymakers are divided as to whether the United States should serve as a member of the Council. Supporters of U.S. participation contend that the United States should work from within the Council to build coalitions with like-minded countries and steer the Council toward a more balanced approach to addressing human rights situations. Council membership, they argue, places the United States in a position to advocate for its human rights policies and priorities. Supporters also maintain that U.S. leadership in the Council has led to several promising Council developments, including increased attention to human rights situations in countries such as Iran, Mali, North Korea, and Sudan, among others. Some have also noted that the number of special sessions addressing Israel has decreased during periods when the United States was on the Council. In addition, some Council supporters are concerned that U.S. withdrawal might lead to a possible leadership gap and countries such as China and Russia could gain increased influence in the Council.40

Opponents contend that U.S. membership provides the Council with undeserved legitimacy. The United States, they suggest, should not be a part of a body that focuses disproportionately on one country (Israel) while ignoring countries that are widely believed to violate human rights.41 Critics further maintain that the United States should not serve on a body that would allow human rights abusers to serve as members. Many also suggest that U.S. membership on the Council provides countries with a forum to criticize the United States, particularly during the UPR process.42

U.S. Funding

Over the years, policymakers have debated to what extent, if any, the United States should fund the Council. Some Members have supported fully funding the Council, while others have proposed that the United States withhold a proportionate share of its assessed contributions (22%) from the U.N. regular budget, which is used to fund the Council.43 Most recently, FY2017 through FY2020 State-Foreign Operations acts have placed conditions on U.S. funding to the Council, and the Trump Administration subsequently withheld about $7.5 million from U.S. contributions to the U.N. regular budget from FY2017 through FY2019. As of February 10, 2020, the Administration reports that it has not yet made a decision regarding FY2020 funding.44 Legislating to withhold Council funds in this manner is a largely symbolic policy action because assessed contributions finance the entire U.N. regular budget and not specific parts of it. The United States had previously withheld funding from the Council in 2008, when the George W. Bush Administration withheld a proportionate share of U.S. Council funding from the regular budget under a law that required the Secretary of State to certify to Congress that funding the Council was in the best national interest of the United States.45

Alternatives to the Council

Some observers and policymakers have argued that the United States can pursue its human rights objectives in multilateral fora other than the Human Rights Council.46 Specifically, they suggest that the United States focus on the activities of the General Assembly's Third Committee, which addresses social, humanitarian, and cultural issues, including human rights.47 Others also recommend that the United States could increase its support for the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, as well as the Council's independent experts who address country-specific and functional human rights issues. Other U.S. policymakers have proposed addressing human rights in the U.N. Security Council. In April 2017, then-U.S. Permanent Representative Haley held the Security Council's first ever thematic debate on human rights issues, where she stated the following:

The traditional view has been that the Security Council is for maintaining international peace and security, not for human rights. I am here today asserting that the protection of human rights is often deeply intertwined with peace and security. The two things often cannot be separated.48

In January 2018, the Security Council met for an emergency session focused on the deaths and detainment of protestors in Iran in the context of widespread demonstrations there. The United States used the occasion to approach the issue from a human rights perspective, while representatives of some other countries on the Security Council questioned whether the meeting fell within the scope of the Security Council's mandate.49 In the context of the Trump Administration's decision to withdraw from the Council, the State Department pointed also to continued U.S. engagement on human rights in non-U.N. fora, including regional membership bodies such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and Organization of American States, and other multilateral institutions such as the Community of Democracies.50

Critics of the withdrawal argue that some proposed alternatives do not carry the same level of influence or attention on human rights as the Human Rights Council, particularly since bodies such as the General Assembly and Security Council do not focus exclusively on human rights issues. Opponents of U.S. withdrawal have pointed to the Council's track record of marshaling country-specific investigations and commissions of inquiry, and contend that unlike the proposed alternatives, the Council includes unique mechanisms to address human rights issues, such the complaint procedure and UPR process.51

Focus on Israel

The Council's ongoing focus on Israel has continued to concern some Members of Congress. In addition to singling out Israel as a permanent part of the Council's agenda, other Council actions—including resolutions, reports, and statements by some Council experts—have generated significant congressional interest for what many view as an apparent bias against Israel.52 Some Members of Congress expressed alarm regarding a March 2016 Council resolution that requested OHCHR to produce a database of all business enterprises that have "directly and indirectly, enabled, facilitated and profited from the construction and growth of the (Israeli) settlements."53 The United States strongly opposed the resolution and voted against it.54 On February 12, 2020, OHCHR published the database. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo expressed "outrage" that OHCHR would publish the document and called on other U.N. members to reject it.55 Some Members of Congress have also opposed the database; for example, H.R. 5595, the Israel Anti-Boycott Act, seeks to prohibit some businesses from cooperating with information collection efforts connected to the database.56 Previously, some Members of Congress demonstrated considerable concern with a September 2009 Council report (often referred to as the "Goldstone Report" after the main author, Richard Goldstone, an independent expert from South Africa), that found "evidence of serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law," including possible war crimes, by Israel. The report received further attention in April 2011, when Goldstone stated that the report's conclusion that Israel committed possible war crimes may have been incorrect.57

Some experts suggest that the Council's focus on Israel is at least partially the result of its membership composition.58 After the first elections, members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) held 17 seats on the Council, accounting for about one-third of the votes needed to call a special session (13 OIC members currently serve on the Council). Some experts contend that blocs such as the African Group and Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), who may at times account for the majority of Council seats, tend to view economic and security issues as more important than human rights violations.

Rising Influence of Other U.N. Member States

Many experts have raised concerns that the Human Rights Council's work is increasingly influenced by countries that do not fully subscribe to international human rights norms and mechanisms. Some maintain that authoritarian governments use the Council as a platform to garner support for novel interpretations of these norms that in effect privilege principles of "noninterference" and strong conceptions of state sovereignty as a means of shielding themselves from international scrutiny.59 These efforts may also aim to undermine the idea that human rights are universal and indivisible, suggesting instead that they are context-dependent, or that some rights are subordinate to others.

Analysts view China under Xi Jinping, in particular, as having taken a more proactive role in attempting to shape global human rights norms and institutions in recent years, including in the Human Rights Council.60 China's normative agenda with regard to human rights has been described as "statist" and "development-first" in that it prioritizes the role of governments as opposed to civil society and individual rights-holders, and privileges development rights in particular.61 In 2017, China's first ever solo-sponsored Human Rights Council resolution, for instance, was entitled "The contribution of development to the enjoyment of human rights" and was viewed by some observers as suggesting that respect for human rights is predicated on development conditions.62 China has supported a number of other resolutions since 2016 that critics argue were intended to undermine the legitimacy of civil society organizations and human rights defenders and discourage the practice of publicly criticizing and pushing for investigations of rights abuses by individual countries, which China views as constituting interference in internal affairs, and instead promote state-led "mutually beneficial cooperation."63 Some have also expressed worry regarding China's April 2020 appointment to the Council's Consultative Panel, which plays a key role in the selection of independent experts to lead country and thematic human rights mandates.64 Reflecting concern over these and related activities, the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) has recommended that the executive branch provide Congress with a "multilateral human rights diplomacy strategy … to coordinate responses when the Chinese government uses multilateral institutions to undermine human rights norms" and prevent international discussion of its own human rights failings.65 The State Department has reportedly created a new Special Envoy position aimed at broadly combating the perceived malign influence of China and other actors within the United Nations.66

Other governments are also viewed as having taken action within the Council to undermine human rights norms. Russia, which was last a Council member in 2016, has arguably sought to undermine the universality of these norms by promoting respect for subjective and context-specific "traditional values." A 2012 Russia-sponsored resolution that pushed this concept was adopted despite opposition from the United States.67 Resolutions of these types have also been consistently supported by like-minded governments such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Cuba. Many resolutions ultimately did not pass, but nonetheless also garnered frequent support across a broad range of other countries, including democracies such as India and Indonesia. Supporting countries may share ideological common ground on these matters, may vote as they do in the interest of ensuring positive bilateral ties with the sponsoring government(s), or may act on the basis of a combination of these motivations.68

These efforts were uniformly opposed by the United States when it was a Council member. In March 2018, prior to the U.S. withdrawal from the Council, the State Department stated that the United States had defended the integrity of U.N. human rights mechanisms by opposing China's resolution on "mutually beneficial cooperation."69 Some analysts and human rights advocates have argued that the U.S. withdrawal undermines the ability of the United States to defend against these actions and effectively cedes space to governments such as China and Russia;70 others contend that the United States can push back on these efforts in other fora.71

Appendix A. Special Sessions of the Human Rights Council

|

|

Source: U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. |

Rising Influence of Other U.N. Member States

Many experts have raised concerns that the Human Rights Council's work is increasingly influenced by countries that do not fully subscribe to international human rights norms and mechanisms. Some maintain that authoritarian governments use the Council as a platform to garner support for novel interpretations of these norms that in effect privilege principles of "noninterference" and strong conceptions of state sovereignty as a means of shielding themselves from international scrutiny.59 These efforts may also aim to undermine the idea that human rights are universal and indivisible, suggesting instead that they are context-dependent, or that some rights are subordinate to others.

Analysts view China under Xi Jinping, in particular, as having taken a more proactive role in attempting to shape global human rights norms and institutions in recent years, including in the Human Rights Council.60 China's normative agenda with regard to human rights has been described as "statist" and "development-first" in that it prioritizes the role of governments as opposed to civil society and individual rights-holders, and privileges development rights in particular.61 In 2017, China's first ever solo-sponsored Human Rights Council resolution, for instance, was entitled "The contribution of development to the enjoyment of human rights" and was viewed by some observers as suggesting that respect for human rights is predicated on development conditions.62 China has supported a number of other resolutions since 2016 that critics argue were intended to undermine the legitimacy of civil society organizations and human rights defenders and discourage the practice of publicly criticizing and pushing for investigations of rights abuses by individual countries, which China views as constituting interference in internal affairs, and instead promote state-led "mutually beneficial cooperation."63 Some have also expressed worry regarding China's April 2020 appointment to the Council's Consultative Panel, which plays a key role in the selection of independent experts to lead country and thematic human rights mandates.64 Reflecting concern over these and related activities, the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) has recommended that the executive branch provide Congress with a "multilateral human rights diplomacy strategy … to coordinate responses when the Chinese government uses multilateral institutions to undermine human rights norms" and prevent international discussion of its own human rights failings.65 The State Department has reportedly created a new Special Envoy position aimed at broadly combating the perceived malign influence of China and other actors within the United Nations.66

Other governments are also viewed as having taken action within the Council to undermine human rights norms. Russia, which was last a Council member in 2016, has arguably sought to undermine the universality of these norms by promoting respect for subjective and context-specific "traditional values." A 2012 Russia-sponsored resolution that pushed this concept was adopted despite opposition from the United States.67 Resolutions of these types have also been consistently supported by like-minded governments such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Cuba. Many resolutions ultimately did not pass, but nonetheless also garnered frequent support across a broad range of other countries, including democracies such as India and Indonesia. Supporting countries may share ideological common ground on these matters, may vote as they do in the interest of ensuring positive bilateral ties with the sponsoring government(s), or may act on the basis of a combination of these motivations.68

These efforts were uniformly opposed by the United States when it was a Council member. In March 2018, prior to the U.S. withdrawal from the Council, the State Department stated that the United States had defended the integrity of U.N. human rights mechanisms by opposing China's resolution on "mutually beneficial cooperation."69 Some analysts and human rights advocates have argued that the U.S. withdrawal undermines the ability of the United States to defend against these actions and effectively cedes space to governments such as China and Russia;70 others contend that the United States can push back on these efforts in other fora.71