Background

Federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs) are a special type of government-owned, contractor-operated research centers—commonly referred to as "GOCOs"—that conduct research and development (R&D) and related activities in support of a federal agency's mission. FFRDCs operate under the framework of the Federal Acquisition Regulation.1 They differ from other performers of federal R&D—such as federal laboratories, universities, non-profit organizations, and private firms—in that they are designed to meet a "special long-term research or development need which cannot be met as effectively by existing in-house or contractor resources" and that they have "access, beyond that which is common to the normal contractual relationship, to Government and supplier data, including sensitive and proprietary data, and to employees and installations equipment and real property."2

Over the years, Congress has been concerned with the oversight and management of FFRDCs, lack of competition in contracting, and mission creep. More recently, some Members of Congress have focused on the need to balance responsible oversight with improved efficiency, effectiveness, and innovation.3 Additionally, the role of FFRDCs in the federal R&D enterprise, including the use of FFRDCs as a model for the governance of federal laboratories, has been an area of congressional interest. The use and management of FFRDCs, in addition to their role in the federal R&D enterprise, will likely be of interest in the 116th Congress.

Origins of FFRDCs

FFRDCs have their origin in World War II. During that time, the federal government sought to mobilize the country's scientific and engineering talent and apply it to the development of technologies that would aid U.S. war efforts. For example, the Department of Defense's (DOD's) Lincoln Laboratory was created to develop radar for identifying aircraft and ships and the Los Alamos and Oak Ridge National Laboratories (now under the auspices of the Department of Energy [DOE]) were established to support the development of the atomic bomb. The purpose of FFRDCs—to bring scientific and technical expertise to bear on pressing R&D challenges—remains.

Then, as now, it was widely believed that a lack of flexibility in the federal government made it difficult to recruit and maintain scientific and technical talent.4 Since FFRDCs are operated by contractors, many federal restrictions, including restrictions on pay and hiring, do not apply, in effect increasing the flexibility of FFRDCs compared to the federal government.5

FFRDCs were called "Federal Contract Research Centers" until 1967.6 In November 1967, the chairman of the Federal Council for Science and Technology, a predecessor to the National Science and Technology Council,7 sent a memorandum to federal science agencies formally changing the name of Federal Contract Research Centers to FFRDCs and detailing criteria for the establishment of an FFRDC.8 Accordingly, an FFRDC was required to:

- conduct basic research, applied research, or development, or perform R&D management;

- be independently incorporated or constitute a separate organizational unit within the parent organization;

- perform R&D under the direction of the federal government;

- receive 70% or more of its funding from one agency;

- have a long-term relationship with its sponsoring agency (five years or more);

- be government-owned; and

- have an average annual budget of at least $500,000.9

In 1984, the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) issued a policy letter revising and updating the governance of FFRDCs.10 The OFPP issued regulations in 1990 that incorporated the principles articulated in the policy letter as part of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR).11 The FAR now defines the purposes of an FFRDC, in addition to the policies that direct an FFRDC's establishment, use, review, and termination. The "Characteristics of FFRDCs" as defined by the FAR are discussed in more detail later in this report.

Current FFRDCs

Currently, 13 federal agencies sponsor or co-sponsor a total of 42 FFRDCs.12 These FFRDCs provide R&D capabilities in a broad range of areas—from energy and cybersecurity to cancer and astronomy. DOE and DOD sponsor a majority of the FFRDCs, 16 and 10 respectively. The National Science Foundation (NSF) sponsors 5 centers, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) sponsors 3, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sponsors 2. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), and the United States Courts each sponsor a single FFRDC. The Department of the Treasury (Treasury), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Social Security Administration co-sponsor a single FFRDC that serves all three.

FFRDCs are classified in three "activity type" categories under a system established by DOD and adopted by NSF. According to NSF, the three categories—R&D laboratory, study and analysis center, or system engineering and integration center are defined as follows:

Research and development laboratories fill voids where in-house and private sector research and development centers are unable to meet agency core area needs. Specific objectives for these FFRDCs are to: (1) maintain over the long-term a competency in technology areas where the Government cannot rely on in-house or private sector capabilities, and (2) develop and transfer important new technology to the private sector so the Government can benefit from a wider, broader base of expertise. R&D laboratories engage in research programs that emphasize the evolution and demonstration of advanced concepts and technology, and the transfer or transition of technology.

Study and analysis centers deliver independent and objective analyses and advise in core areas important to their sponsors in support of policy development, decisionmaking, alternative approaches, and new ideas on issues of significance.

System engineering and integration centers provide required support in core areas not available from sponsor's in-house technical and engineering capabilities to ensure that complex systems meet operational requirements. The centers assist with the creation and choice of system concepts and architectures, the specification of technical system and subsystem requirements and interfaces, the development and acquisition of system hardware and software, the testing and verification of performance, the integration of new capabilities, and continuous improvement of system operations and logistics. They often play a critical role in assisting their sponsors in technically formulating, initiating, and evaluating programs and activities undertaken by firms in the for-profit sector. 13

NSF has the responsibility of maintaining a master list of FFRDCs across the federal government. According to NSF and as shown in Appendix A, 26 of the 42 current FFRDCs are R&D laboratories, 10 are study and analysis centers, and 6 are system engineering and integration centers.

|

DOD Definitions of FFRDC Categories In 2018, under the DOD Federally Funded Research and Development (FFRDC) Program, the department adopted the following DOD specific definitions for the three categories of FFRDCs:

|

Characteristics of FFRDCs

The Federal Acquisition Regulation system (FAR) governs the establishment, use, review, and termination of FFRDCs.15 According to the FAR, FFRDCs are intended to address an R&D need that cannot be met as effectively by the federal government or the private sector alone. Essentially, FFRDCs are intended to only perform work that cannot be done by other contractors. FFRDCs accomplish their R&D through a strategic relationship with their sponsoring agency. Two overarching characteristics—special access and longevity—define this strategic relationship.

An FFRDC may be given special access to government and supplier data, employees, and facilities.16 This access is beyond what is typical in a normal contractual relationship and may include access to sensitive and proprietary information. Accordingly, the FAR requires that FFRDCs (1) operate in the public interest with objectivity and independence, (2) be free from organizational conflicts of interest, and (3) fully disclose their activities to their sponsoring agency.17 Additionally, FFRDCs are not allowed to use their special access to privileged information, equipment, or property to compete with the private sector for federal R&D contracts. However, an FFRDC is allowed to perform work for other agencies when the capabilities of the FFRDC are not available in the private sector. Finally, the prohibition against competing with the private sector for federal R&D contracts does not apply to the parent organization or any subsidiary of the parent organization associated with an FFRDC.18

The other defining characteristic is the long-term relationship between an FFRDC and its sponsoring agency. Under the FAR, the initial contract period of an FFRDC may be up to five years, but these contracts may be renewed, following a review, in increments of up to five years.19 For example, one DOE FFRDC—the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory—has been operating under the same contract since 1964. The FAR encourages long-term contracts to provide stability and continuity that are intended to allow an FFRDC to attract high-quality personnel.20 Additionally, under the FAR, a long relationship is required to enable the FFRDC to maintain in-depth expertise, stay familiar with the needs of the agency, provide a quick response capability, and maintain objectivity and independence.21

In addition to the described characteristics and requirements, prior to establishing an FFRDC, a sponsoring agency must make sure that there are no existing alternatives for addressing the agency's R&D needs (i.e., the research cannot be done effectively by the federal government or the private sector) and that the agency has the expertise necessary to review the performance of the FFRDC.22 The sponsoring agency must also ensure that cost controls are in place and that the purpose and mission of the FFRDC are clearly defined.23

Other organizations, such as University Affiliated Research Centers (UARCs), have characteristics and requirements similar to those of FFRDCs. A brief description of UARCs is provided in the following box.

|

University Affiliated Research Centers (UARCs) Currently, there are 13 University Affiliated Research Centers all sponsored by a DOD military service, agency, or component. UARCs provide an engineering, research, or development capability to the federal agency that supports them. UARCs are located within a university or college and typically receive funding in excess of $6 million per year on a non-competitive basis from their sponsoring federal agency. As illustrated in a 2018 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), the amount of funding DOD directs to an individual UARC can vary widely. For example, in FY2017 one UARC received $1.2 million in funding while another received $78.7 million.24 UARCs are not defined in federal statute. However, DOD has established policies and procedures for their management.25 The characteristics of UARCs are very similar to FFRDCs. The defining feature of UARCs, like FFRDCs, is the long-term strategic relationship they have with their sponsoring federal agency. This relationship is intended to allow for in-depth knowledge of the agency's research needs, independence and objectivity, freedom from conflicts of interest, access to sensitive information, and the ability to respond quickly to emerging research areas. The primary differences between UARCs and FFRDCs are that UARCs must be affiliated with a university, must have education as part of their overall mission, and have greater flexibility to compete for public and private R&D contracts.26 According to GAO, DOD oversight of the department's UARCs differs from its FFRDCs. The DOD military service, agency, or component serving as the primary sponsor of a UARC conducts policy and contract oversight of a UARC, in contrast to conducting active oversight of a DOD FFRDC (i.e., DOD must approve all FFRDC work before it is placed on contract).27 |

Federal Funding of FFRDCs

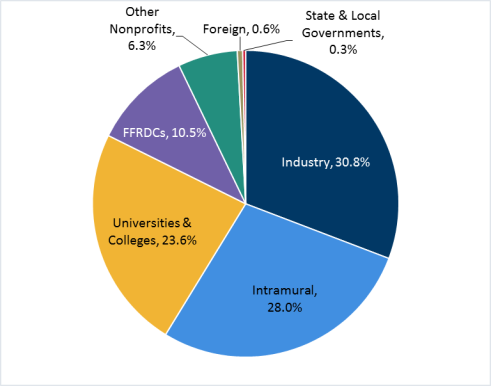

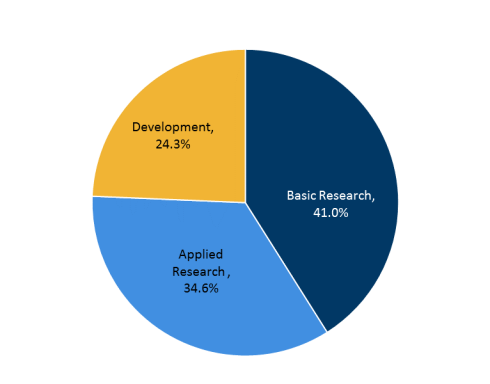

According to NSF, the federal government reported obligating $141.5 billion on R&D in FY2019.28 Of this amount, $14.9 billion or 10.5% of the total reported amount was spent on R&D performed by FFRDCs, compared to $43.6 billion (30.8%) performed by industry, $39.6 billion (28.0%) performed by federal agencies (intramural), and $33.4 billion (23.6%) performed by universities and colleges (Figure 1). Other nonprofit organizations, state and local governments, and foreign entities performed the remaining $10.1 billion (7.2%) of R&D funded by the federal government in FY2019 (Figure 1, see box below for definitions of R&D performers. Of the reported federal funds obligated to FFRDCs in FY2019, 41% was for basic research, 36% was for applied research, and 24% was for development (Figure 2).

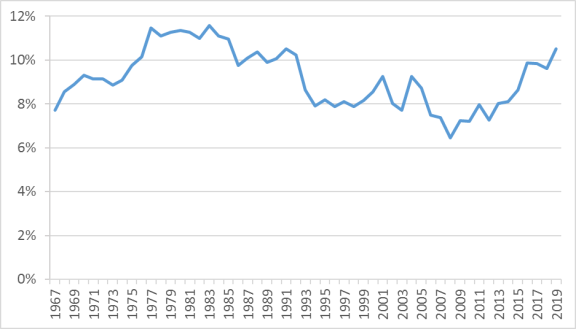

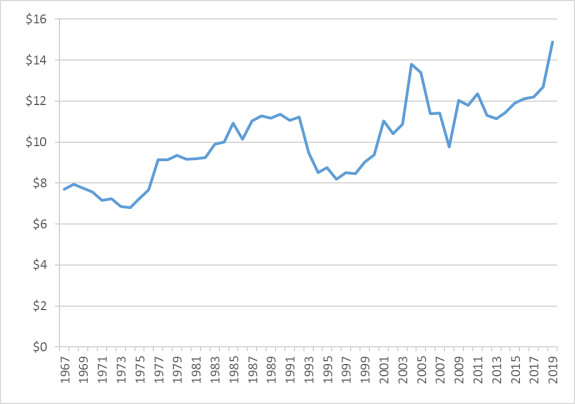

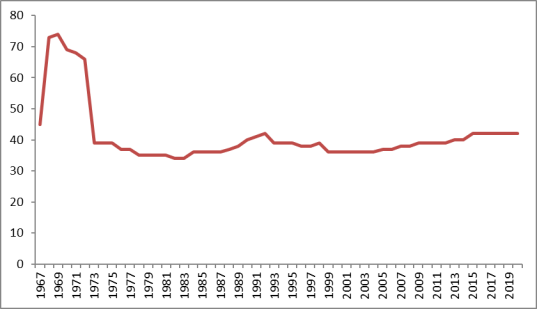

Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate federal R&D spending trends for FFRDCs from FY1967 to FY2019. Figure 3 shows that the proportion of total reported federal R&D spending obligated to FFRDCs has varied over time, ranging from a high of 11.6% in FY1983 to a low of 6.4% in FY2008. On average, between FY1967 and FY2019, the federal government reported obligating 9.2% of its federal R&D spending to FFRDCs. In constant dollars, federal funding for FFRDCs grew from $7.69 billion to $14.87 billion from FY1967 to FY2019 (Figure 4). This increase represents a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 1.25% compared to the CAGR of 0.66% for total reported federal R&D spending over the same period. Federal funding for FFRDCs in FY2019 ($14.87 billion) was 17.1% higher than in FY2018 ($12.70 billion) and represents the largest amount of federal funding for FFRDCs to date. As shown in Appendix B, the number of FFRDCs has fluctuated over time, from a high of 74 in FY1969 to a low of 34 in FY1982.

|

Figure 1. Share of Federal R&D Obligations by R&D Performer, FY2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from National Science Foundation, Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development, Fiscal Years 2018–19, Table 8, https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/fedfunds/2018/index.html. Notes: Components may not sum to 100% due to rounding. A total of 32 federal agencies (15 federal departments and 17 independent agencies) reported R&D data to NSF for the survey for FY2018-FY2019. As described by NSF, "some measurement problems are known to exist in the Federal Funds Survey data. Some agencies cannot report the full costs of R&D, the final performer of the R&D, or the R&D plant data." For more information on the survey design, data collection and processing, and survey quality measures, among other areas, see "Survey Description," at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvyfedfunds/#tabs-1&sd. |

|

Figure 2. Federal Obligations to FFRDCs by Character of Work, FY2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from National Science Foundation, Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development, Fiscal Years 2018–19, Tables 28, 40, and 52, https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/fedfunds/2018/index.html. Notes: Components may not sum to 100% due to rounding. A total of 32 federal agencies (15 federal departments and 17 independent agencies) reported R&D data to NSF for the survey for FY2018-FY2019. As described by NSF, "some measurement problems are known to exist in the Federal Funds Survey data. Some agencies cannot report the full costs of R&D, the final performer of the R&D, or the R&D plant data." For more information on the survey design, data collection and processing, and survey quality measures, among other areas, see "Survey Description," at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvyfedfunds/#tabs-1&sd. |

|

Figure 3. Share of Federal R&D Obligations to FFRDCs, FY1967-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from National Science Foundation, Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development, Fiscal Years 2018–19, Table 116, https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/fedfunds/2018/index.html. Notes: As described by NSF, "some measurement problems are known to exist in the Federal Funds Survey data. Some agencies cannot report the full costs of R&D, the final performer of the R&D, or the R&D plant data." For more information on the survey design, data collection and processing, and survey quality measures, among other areas, see "Survey Description," at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvyfedfunds/#tabs-1&sd. |

|

Definitions Associated with Federal R&D Performers29 Intramural performers are the agencies of the federal government. R&D is carried out directly by agency personnel. Extramural performers are organizations outside the federal sector that perform R&D with federal funds under contract, grant, or cooperative agreement. Types of extramural performers: Businesses or Industrial firms: organizations that may legally distribute net earnings to individuals or to other organizations. Universities and colleges: institutions of higher education in the United States that engage primarily in providing resident or accredited instruction for a not less than a 2-year program above the secondary school level that is acceptable for full credit toward a bachelor's degree or that provide not less than a 1-year program of training above the secondary school level that prepares students for gainful employment in a recognized occupation. Other nonprofit institutions: private organizations other than educational institutions whose net earnings do not benefit either private stockholders or individuals and other private organizations organized for the exclusive purpose of turning over their entire net earnings to such nonprofit organizations. Federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs): R&D-performing organizations that are exclusively or substantially financed by the federal government and are supported by the federal government either to meet a particular R&D objective or in some instances to provide major facilities at universities for research and associated training purposes. Each center is administered by an industrial firm, a university, or another nonprofit institution. State and local governments: State and local government agencies, excluding state or local universities and colleges, agricultural experiment stations, medical schools, and affiliated hospitals. R&D activities are performed either by the state or local agencies themselves or by other organizations under grants or contracts from such agencies. Foreign performers: Foreign citizens, organizations, or governments, as well as international organizations performing R&D work abroad financed by the federal government. |

|

Figure 4. Federal R&D Obligations to FFRDCs, FY1967-FY2019 in billions of constant FY2019 dollars |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from National Science Foundation, Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development, Fiscal Years 2018–19, Table 116, https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/fedfunds/2018/index.html. Notes: As described by NSF, "some measurement problems are known to exist in the Federal Funds Survey data. Some agencies cannot report the full costs of R&D, the final performer of the R&D, or the R&D plant data." For more information on the survey design, data collection and processing, and survey quality measures, among other areas, see "Survey Description," at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvyfedfunds/#tabs-1&sd. |

Table 1 shows the amount of reported preliminary federal funding obligated to FFRDC in FY2019, the share of total FFRDC funding provided by each agency, and the share of each agency's R&D budget spent at FFRDCs. Three federal agencies—DOE, NASA, and DOD—accounted for nearly 92% of all reported preliminary federal R&D funding obligated to FFRDCs in FY2019. DOE accounted for $8.5 billion (57.0%) of the total $14.9 billion in preliminary FFRDC funding reported for FY2019. This represented 58.0% of DOE's total R&D budget, indicating the central role FFRDCs play in fulfilling the agency's research needs. By comparison, NASA accounted for $3.1 billion (20.9%) of total preliminary FFRDC funding, which represented 20.3% of the agency's R&D budget and DOD accounted for $2.1 billion (14.1%) of the total funding, which represented 3.7% of DOD's R&D budget (Table 1).

Similar to DOE, the United States Courts and the NRC relied heavily on FFRDCs to execute their R&D needs in FY2019. The United States Courts spent all of its R&D budget on R&D performed by FFRDCs ($5.9 million) and the NRC obligated 32.9% ($21.3 million) of the agency's R&D budget to FFRDCs (Table 1). Other federal agencies spent variable amounts of their agency's estimated FY2019 R&D budget on R&D performed by FFRDCs. For example, HHS spent $673.1 million or 1.7% of its R&D budget, NSF spent $290.8 million or 4.8% of its R&D budget, DOT spent $126.9 million or 10.8% of its R&D budget, DHS spent $64.0 million or 6.8% of its R&D budget, and the Department of Commerce (DOC) spent $22 million or 1.4% of its R&D budget on R&D performed by FFRDCs (Table 1).

|

FFRDC Obligations |

% of Total Federal R&D Obligations to FFRDCs |

% of Agency R&D Budget to FFRDCs |

|||||||

|

Department of Energy |

|

|

|

||||||

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Department of Defense |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

|

|

||||||

|

National Science Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Department of Transportation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Department of Homeland Security |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Department of Commerce |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

|

|

|

||||||

|

United States Courts |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Department of Education |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Department of the Interior |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from National Science Foundation, Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development, Fiscal Years 2018–19, https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/fedfunds/2018/index.html.

Notes: As described by NSF, "some measurement problems are known to exist in the Federal Funds Survey data. Some agencies cannot report the full costs of R&D, the final performer of the R&D, or the R&D plant data." For more information on the survey design, data collection and processing, and survey quality measures, among other areas, see "Survey Description," at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvyfedfunds/#tabs-1&sd.

Issues for Congress

FFRDCs have attracted the attention of Congress for decades. Historically, congressional concern focused on the growth of FFRDCs and their cost to the government (see Appendix B for the number of FFRDCs from FY1967 to FY2020). In more recent years, Congress has focused on the management and oversight of FFRDCs and their insulation from competition. Many of these concerns remain. The following sections describe some of these issues.

Effectiveness of Oversight and Management

The adequacy of agency oversight and management of FFRDCs is a long-standing congressional concern. Some Members of Congress have repeatedly expressed concern about the ability of federal agencies to control costs and address perceived mismanagement at FFRDCs. For example, in 1992, a Senate subcommittee report indicated "that FFRDCs today operate under an inadequate, inconsistent patchwork of federal cost, accounting and auditing controls, whose deficiencies have contributed to the wasteful or inappropriate use of millions of federal dollars."30 In a 2016 hearing examining the mission and management of DOE's FFRDCs, Representative Fred Upton, Chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, stated,

DOE's safety, security, and contract management problems span administrations, span Congresses. From my experience, and as our witnesses will explain, improving DOE's performance requires long, sustained attention to ensure sustained improvement in agency performance.31

Congressional scrutiny is driven, in part, by a number of high-profile incidents. For example, in 2000, two Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) computer hard drives went missing and an employee was accused of planning to sell nuclear information to China.32 In 2004, the mishandling of classified data and the partial blinding of a student from a laser accident closed LANL for seven months, costing $370 million.33 Additionally, in 2016, an investigation found that LANL mishandled hazardous waste, and nine LANL workers were injured during routine maintenance of an electrical substation.34

Since the early 1990s, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has designated DOE's contract management as a high-risk area for fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement.35 In 2013, GAO narrowed its high-risk designation to major contracts and projects within DOE's Office of Environmental Management and the National Nuclear Security Administration, which manages three DOE FFRDCs.36 In 2018, while noting some of the progress made by DOE in addressing its oversight and management challenges, GAO indicated that "challenges remain."37 And, in a 2019 review of how DOE evaluates the performance of contractors who manage and operate DOE facilities, including FFRDCs, GAO found the following:

In analyzing DOE's fiscal year 2016 Performance Evaluation Reports (PER), GAO found that these reports provided less information on M&O [management and operating] contractors' cost performance than on contractors' technical and administrative performance. The cost information provided in the PERs often was not detailed, did not indicate the significance of the performance being described, and applied only to specific activities. Further, the information is of limited use for acquisition decision-making, such as deciding whether to extend the length of a contract, because it does not permit an overall assessment of cost performance.38

Since 2002, DOE has been shifting its FFRDC oversight from a transactional model to a systems-based approach that assesses analytical information collected by the FFRDCs through what is known as contractor assurance systems (CAS).39 Many stakeholders recognize the use of CAS as a positive step to improving DOE oversight.40 However, in 2013, the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) called on DOE to exercise caution as it transitioned to this oversight model.41 NAPA indicated that the maturity of CAS varies and that DOE needs to verify the ability of an FFRDC's CAS to identify problems before they occur.

In contrast, others view DOE's overall oversight and management activities as burdensome, counterproductive, and a distortion of the FFRDC model.42 Critics assert that the original benefit of the FFRDC model—flexibility—has been substantially diminished because DOE now micromanages its FFRDCs. According to a 2013 report by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, the Center for American Progress, and the Heritage Foundation,

Decisions that should be made by research teams and lab managers are instead preapproved and double checked by a long and growing chain of command at DOE. There is no better example of this oversight than the hundreds of DOE site-office43 employees staffed to regulate lab managers and research by proxy. This adds considerable delay and introduces additional costs to routine business decisions.44

Some of those concerned about the detrimental effects of increased micromanagement would like to see a return to the original intent of the FFRDC model: a model where the government sets the overall strategic direction and provides the necessary funding and the FFRDC is given the flexibility to determine how to address the identified challenges.45 Critics indicate that a lack of trust currently exists between DOE and its laboratories and that in order to return to the partnership envisioned by the FFRDC model, this trust needs to be restored. They recommend that DOE provide its FFRDCs with more authority and flexibility, and then hold each FFRDC to a high standard of transparency and accountability.46 According to the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, the Center for American Progress, and the Heritage Foundation, if an individual FFRDC does not meet its obligations, corrective actions, including punitive restrictions and possibly the firing of the FFRDC contractor, are valid options, but they assert that the mistakes of one FFRDC should not result in new regulations and additional oversight for all DOE FFRDCs.47

Competition with the Private Sector

Congress and the executive branch have been interested in promoting competition in federal procurement, including the procurement of R&D, for decades. However, federal law explicitly exempts FFRDCs from competitive practices.48 Historically, critics of this exemption have asserted that it prohibits the federal government from receiving the best possible R&D at the most competitive price.49 For example, in a 1997 report, the Defense Science Board stated, "the lack of competition for much of the work being done in the FFRDCs is not justified, nor in the long run is it in the best interests of the DOD."50 Additionally, some critics have pointed out that the R&D capabilities of the private sector have increased dramatically since World War II and the continued use of FFRDCs is in direct opposition to their original intent—to conduct R&D that cannot be done as effectively by the private sector or the federal government.51 A 2016 report by the Defense Business Board—an advisory committee composed of business leaders and managers—stated,

Today, the for-profit sector can provide most of the technical services that was, in the past, only available from a FFRDC. However, in many cases there remain sound reasons to give the work to FFRDCs, such as avoiding potential conflicts of interest, access to confidential competitive information or deep historical knowledge and experience not available in for-profit companies.52

More recently, critics have focused on the use of FFRDCs for systems engineering and integration (SE&I) services.53 The Professional Services Council (PSC), the national trade association of the government professional and technical services industry, has asserted that the SE&I capabilities of the private sector are as good as or better than those of FFRDCs.54 According to PSC, "prior to the 1990s, FFRDCs were often favored over for-profit systems engineering companies on grounds of avoiding potential conflicts of interest."55 However, PSC also suggested that congressionally initiated reforms through the Weapon System Acquisition Reform Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-23) have resulted in a sizable number of private sector SE&I companies that are conflict free, independent, and capable of performing the SE&I work currently going to FFRDCs.56

In the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Section 895 of P.L. 114-92), Congress included a provision to address concerns about conflicts of interest and unfair competitive advantages associated with sole-source task orders to entities that provide technical advice on defense programs. Specifically, the provision requires DOD to review and, if necessary, issue policy guidance related to the identification, mitigation, and prevention of potential unfair competitive advantages conferred to technical advisors to acquisition programs. As detailed in the joint explanatory statement accompanying the bill, technical advisors are contractors, FFRDCs, university-affiliated research centers, non-profit entities, and federal laboratories that provide, among other services, systems engineering and technical direction.57 In carrying out the provision, the joint explanatory statement directs DOD

To review the efficacy of current conflict-of-interest policies, the use of non-disclosure agreements, the application of appropriate regulations, and decisions to allocate resources through direct award of funds to intramural programs or sole-source task orders to entities that provide technical advice on defense programs versus open and competitive extramural solicitations.58

In December 2019, GAO reviewed DOD's use of study and analysis FFRDCs and found that all five of DOD's study and analysis centers had conflict of interest policies and practices in line with the FAR and DOD guidance related to FFRDCs.59

It is less clear, however, if the private sector could fully address the work being performed by FFRDCs categorized as R&D laboratories. According to PSC, FFRDCs "maintain laboratories and specialized test and evaluation facilities beyond those available to the government and its for-profit contractors."60 Additionally, proponents assert that FFRDCs "occupy a key role in the nation's S&T [science and technology] community that cannot be carried out solely by academic institutions or the business sector."61 FFRDCs are widely seen as contributing to U.S. technological and economic leadership.

Mission Creep

The diversification of FFDRC activities or "mission creep" is an issue closely related to concerns about competition with the private sector. A poorly defined mission or scope may make it more difficult to determine what R&D tasks are appropriate for an FFRDC to perform and what tasks are better left to the private sector. Concerns over mission creep are associated not only with the broadening of FFRDC activities into new fields, but also with the broadening of FFRDC clients (e.g., work for other agencies). Some analysts have asserted that diversification of FFRDC activities is contrary to the intent of FFRDCs—to serve a special R&D need—and an ineffective means for accomplishing the federal agency's mission.62 In 1995, a task force examining the future of the DOE national laboratories stated that applying the technical competencies of the national laboratories to new problem areas needed to be carefully managed.63 Specifically, the task force said such activities

should not be a license to expand into areas of science and technology which already are being addressed effectively or more appropriately by other Research and Development (R&D) performers in government, academia and the private sector.64

Agencies have approached mission creep concerns in different ways. DOE has placed limits on the amount of work its FFRDCs can perform for other agencies. Specifically, if the work for other agencies and non-governmental entities in a DOE Office of Science FFRDC is 20% above the FFRDC's operating budget, then DOE requires an in-depth review prior to approving the work.65 Such a review is intended to ensure the work that DOE FFRDCs are performing for other entities will not impede its ability to meet DOE's research needs. However, in a 2013 report, GAO indicated that DOE is not consistently fulfilling agency requirements—project approval, cost recovery, or program review—to ensure its work for others program is not negatively affecting the laboratories' mission.66

In regards to DOD, Congress has included language each year since 1993 in the defense appropriations bill that prohibits DOD from establishing new FFRDCs.67 Congress has also placed an annual limit on the number of Staff Years of Technical Effort (STE) that DOD FFRDCs can use to perform work for the agency.68 STE is a cap on personnel time which translates into a cap on funding levels for each FFRDC. DOD allocates a portion of STE to each of its FFRDCs. Limiting the personnel time available to each DOD FFRDC is believed to drive prioritization of needs and provide greater assurance that the work being performed by FFRDCs is appropriate in scope.69 As noted by the Defense Business Board, the STE limitation does not apply to work that DOD FFRDCs perform for other agencies and "it is not clear how much rigor is applied to the [STE] allocation process."70

In general, according to GAO, federal agency approval of annual FFRDC R&D plans should ensure activities remain within the scope, mission, and purpose of the FFRDC.71 Additionally, the Defense Business Board recommended that DOD conduct periodic in-depth reviews of its FFRDCs every seven to ten years using independent experts to review an FFRDC's mission and priorities; assess the quality of an FFRDC's work; and assess the relevance of their strategic or technical expertise.72

Competition of FFRDC Contracts

A hallmark of FFRDCs is the long-term relationship each has with its sponsoring agency. A long-term relationship is believed to provide stability and continuity and is considered central to attracting and retaining scientific and technical expertise. Many FFRDCs have been managed by the same contractor since they were created. For example, Associated Universities, Inc. has operated NSF's National Radio Astronomy Observatory since 1956; RAND Corporation has operated DOD's Project Air Force since 1946; and MITRE Corporation has operated FAA's Center for Aviation System Development since 1990. However, some Members of Congress, GAO, and others have criticized the use of noncompetitive procedures for FFRDC contracts.73 These critics view competition as the best way to decrease costs and increase quality. For example, in 2003, a report by the Blue Ribbon Commission on the Use of Competitive Procedures for the Department of Energy Labs found that "competition imposes discipline and can elicit quality performance and efficient operation in ways simply not inspired by oversight alone."74

DOE has shifted from a position of not regularly conducting full and open competitions for its FFRDCs to routinely subjecting its FFRDCs to competition. Congressional action spurred this shift. Specifically, between FY1998 and FY2009 congressional appropriations acts mandated the use of competition for all DOE FFRDC contracts unless the Secretary of Energy granted a waiver to competition and provided the appropriations committees with a detailed justification for the waiver.75

Annual appropriations language was not included after FY2009 because on December 22, 2009, the Secretary of Energy released a policy on the agency's use of competition for the management and operation of its FFRDCs.76 The policy states,

DOE does not default to a posture of determining a priori either that the Department will conduct competitions for all its M&O contracts, or that it will extend all these contracts. DOE recognizes a preference for full and open competition, and exercises, on a case-by-case basis, the authorities available to the Secretary.

According to DOE, the agency generally uses full and open competition under the following circumstances: when the performance of an FFRDC operator is viewed as unsatisfactory; when the potential for improved costs or technical performance has been identified; when viable alternatives exist in the marketplace; or when the agency decides to change the focus or mission of an FFRDC.77 In 2018, DOE awarded a new contract to Triad National Security, LLC—a partnership between Battelle Memorial Institute, the Texas A&M University System, and the Regents of the University of California—for the management and operation of Los Alamos National Laboratory. The new contract was awarded due to concerns with the performance of the previous contractor, which included health and safety issues.78 Media reports, however, question the ability of Triad National Security to make significant improvements as one of the entities involved in the partnership, the University of California, was part of the previous contract management team.79

Although competition is widely seen as an important tool for increasing performance and efficiency, some experts have asserted that there are downsides associated with the competition of FFRDC contracts.80 Specifically, critics view competition of existing FFRDCs as disruptive, costly, and harmful to FFRDC productivity.81 According to DOE, the time to conduct an FFRDC competition is approximately 18 months and it is estimated to cost a contractor preparing a bid between $3 million and $5 million.82 In describing its experiences with increased competition, DOE has stated,

although some efficiencies or improved contractual agreements have been made possible as a result of the new contracts the overall performance of the new contractors has in most cases not surpassed that of the old, and it is arguable that what improvements have been observed could have been achieved even in the absence of competition.83

In 2008, GAO found that while most agencies required full and open competition for their FFRDC contracts, DOD continued to award noncompetitive or sole-source contracts to its FFRDCs.84 However, GAO also found that in response to criticism DOD began conducting more detailed and comprehensive reviews before renewing its FFRDC contracts.85 Additionally, a 2009 report by NASA's Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that the agency did not conduct an assessment of possible competitors, as required by the FAR, for operation of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.86 According to the NASA OIG, without performing the assessment NASA could not determine if it was getting the best value for the operation of its FFRDC.87

Condition of FFRDC Infrastructure

Similar to other government-owned laboratories, the facilities and infrastructure of many FFRDCs are decades old. According to GAO, DOD FFRDC officials cited aging facilities and equipment as a hindrance to research and development efforts. For example, officials from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—the contractor and administrator of Lincoln Laboratory—indicated that some of the facilities "were not structurally designed for modern research and have relatively poor vibration isolation, resulting in inefficient workarounds or work that could not be performed."88

In a recent report, the Inspector General of the Department of Energy listed infrastructure modernization as one of DOE's top management challenges, stating,

Facilities and infrastructure can have a substantial impact on laboratory research and operations in a variety of ways. For instance, poor conditions in laboratory facilities and infrastructure can lead to inadequate functionality in mission performance; negative effects on the environment, safety, and health of the site; higher maintenance costs; and problems with recruiting and retaining high-quality scientists and engineers.89

Furthermore, a 2017 report on the state of DOE's national labs, indicates that despite investment by DOE "the condition of a large percentage of the infrastructure is substandard or inadequate for the mission as a result of more than five decades of aging, deterioration, and insufficient funding to keep pace with needed improvements."90

According to GAO, NASA's Inspector General has also identified aging infrastructure and facilities as a management challenge for the agency, including for NASA's FFRDC—the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)—where more than 50% of JPL's facilities are more than 50 years old.91

Appendix A. List of Federally Funded Research and Development Centers, as of March 2020

|

Sponsoring Agency |

Name of FFRDC |

Activity Type |

Contractor |

|

Department of Defense |

Aerospace Federally Funded Research and Development Center |

Systems Engineering and Integration Center |

The Aerospace Corporation |

|

Arroyo Center |

Study and Analysis Center |

RAND Corp. |

|

|

National Security Engineering Center |

Systems Engineering and Integration Center |

MITRE Corp. |

|

|

Center for Naval Analyses |

Study and Analysis Center |

The CNA Corporation |

|

|

Center for Communications and Computing |

R&D Laboratory |

Institute for Defense Analyses |

|

|

Lincoln Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

|

|

National Defense Research Institute |

Study and Analysis Center |

RAND Corp. |

|

|

Project Air Force |

Study and Analysis Center |

RAND Corp. |

|

|

Software Engineering Institute |

R&D Laboratory |

Carnegie Mellon University |

|

|

Systems and Analyses Center |

Study and Analysis Center |

Institute for Defense Analyses |

|

|

Department of Energy |

Ames Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Iowa State University |

|

Argonne National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

UChicago Argonne, LLC |

|

|

Brookhaven National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Brookhaven Science Associates, LLC |

|

|

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Fermi Research Alliance, LLC |

|

|

Idaho National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Battelle Energy Alliance, LLC |

|

|

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

University of California |

|

|

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC |

|

|

Los Alamos National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Triad National Security, LLC |

|

|

National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC |

|

|

Oak Ridge National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

UT-Battelle, LLC |

|

|

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Battelle Memorial Institute |

|

|

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Princeton University |

|

|

Sandia National Laboratories |

R&D Laboratory |

National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC |

|

|

Savannah River National Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Savannah River Nuclear Solutions, LLC |

|

|

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

Stanford University |

|

|

Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility |

R&D Laboratory |

Jefferson Science Associates, LLC |

|

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

CMS Alliance to Modernize Healthcare |

Study and Analysis Center |

MITRE Corp. |

|

Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research |

R&D Laboratory |

Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc. |

|

|

Department of Homeland Security |

Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center |

Study and Analysis Center |

RAND Corp. |

|

Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute |

Systems Engineering and Integration Center |

MITRE Corp. |

|

|

National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center |

Study and Analysis Center |

Battelle National Biodefense Institute |

|

|

Department of Transportation |

Center for Advanced Aviation System Development |

R&D Laboratory |

MITRE Corp. |

|

Department of the Treasury, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Social Security Administration |

Center for Enterprise Modernization |

Systems Engineering and Integration Center |

MITRE Corp. |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

R&D Laboratory |

California Institute of Technology |

|

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence |

Systems Engineering and Integration Center |

MITRE Corp. |

|

National Science Foundation |

National Center for Atmospheric Research |

R&D Laboratory |

University Corporation for Atmospheric Research |

|

National Optical Astronomy Observatory |

R&D Laboratory |

Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc. |

|

|

National Radio Astronomy Observatory |

R&D Laboratory |

Associated Universities, Inc. |

|

|

National Solar Observatory |

R&D Laboratory |

Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc. |

|

|

Science and Technology Policy Institute |

Study and Analysis Center |

Institute for Defense Analyses |

|

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

Center for Nuclear Waste Regulatory Analyses |

Study and Analysis Center |

Southwest Research Institute |

|

United States Courts |

Judiciary Engineering and Modernization Center |

Systems Engineering and Integration Center |

MITRE Corp. |

Source: National Science Foundation, Master List of Federally Funded R&D Centers, at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/ffrdclist/ and CRS analysis of data from National Science Foundation, Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development, Fiscal Years 2018–19, Table 13, https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/fedfunds/2018/index.html.

Appendix B. Number of FFRDCs, FY1967–FY2020

|

|

Source: CRS generated figure. Data from U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, A History of the Department of Defense Federally Funded Research and Development Centers, OTA-BP-ISS-157 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, June 1995), pp. 51-52; and National Science Foundation, Master List of Federally Funded R&D Centers, at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/ffrdclist/. |