Introduction

In 1984, the Crime Victims Fund (CVF, or the Fund) was established by the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA, P.L. 98-473) to provide funding for state victim compensation and assistance programs.1 Since 1984, VOCA has been amended several times to support additional victim-related activities. These amendments established that the CVF be used for

- discretionary grants for private organizations,2

- the Federal Victim Notification System,3

- funding for victim assistance staff in the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Executive Office of U.S. Attorneys (EOUSA),4

- funding for the Children's Justice Act Program,5

- assistance and compensation for victims of terrorism,6

- sexual assault survivors' notification grants and ensuring rights of sexual assault survivors,7 and

- restitution for victims of child pornography.8

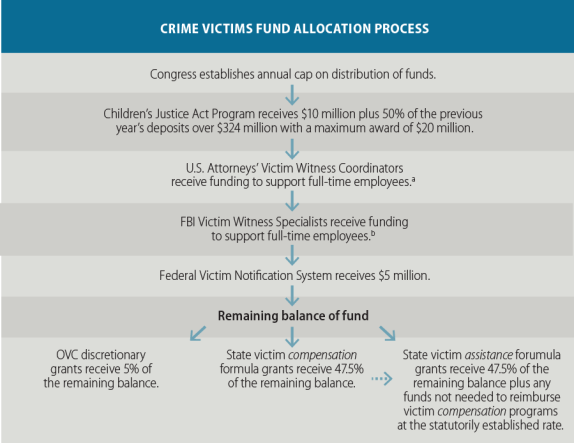

In 1988, the Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) was formally established within the Department of Justice (DOJ) to administer the CVF.9 As authorized by VOCA, the OVC awards CVF money through formula and discretionary grants to states, local units of government, individuals, and other entities. The OVC also distributes CVF money to specially designated programs, such as the Children's Justice Act Program and the Federal Victim Notification System (see Figure 1).10

The OVC's mission is to enhance the nation's capacity to assist crime victims and to improve attitudes, policies, and practices that promote justice and help victims. According to the OVC, this mission is accomplished by (1) administering the CVF, (2) supporting direct services for victims, (3) providing training programs for service providers, (4) sponsoring the development of best practices for service providers, and (5) producing reports on best practices.11 The OVC funds victim-support programs in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, tribes, and the territories.12

Notably, Congress has amended VOCA several times to provide support for victims of terrorism.13 These amendments established CVF-funded programs for (1) assistance to victims of terrorism14 who are injured or killed as a result of a terrorist act outside the United States, (2) compensation and assistance to victims of terrorism within the United States, and (3) an antiterrorism emergency reserve fund to support victims of terrorism.

This report provides background and funding information for VOCA programs and the CVF. It describes the process through which funds in the CVF are allocated and explains how the CVF affects the annual budget for DOJ. It then provides an analysis of selected issues that Congress may consider regarding the CVF and the federal budget.

Financing of the Crime Victims Fund

Deposits to the CVF

The CVF does not receive appropriated funding.15 Rather, deposits to the CVF come from a number of sources including criminal fines, forfeited bail bonds, penalties, and special assessments collected by the U.S. Attorneys' Offices, federal courts, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons from offenders convicted of federal crimes.16 In 2001, the USA PATRIOT Act (P.L. 107-56) established that gifts, bequests, or donations from private entities could also be deposited to the CVF.

The largest source of deposits into the CVF is criminal fines.17 Large criminal fines, if collected, can have a significant effect on deposits into receipts for the CVF. For example, from FY1996 through FY2004, fines collected from 12 defendants in federal courts accounted for 45% of all deposits to the CVF during this time period.18 Table 1 provides the amounts deposited into the CVF in each fiscal year from FY1985 to FY2019.

Fluctuation in Deposits and Growth of the Fund

As Table 1 illustrates, since FY2000 there has been considerable fluctuation in the amounts deposited each fiscal year. For example, from FY2013 to FY2014 the monetary amount collected rose by over 140.0% and then decreased by approximately 26.0% in FY2015. This was followed by a 43.7% decrease in FY2016, and then a 443.0% increase in FY2017. Table 1 provides the annual amounts collected from FY1985 through FY2019.

During the last decade, approximately $24 billion has been deposited into the CVF. Large criminal fines levied in cases of financial fraud and other white collar crimes contributed to the sizeable growth of the Fund.19 Although OVC had expected deposits to remain high due to major fines levied against federal offenders (in particular, against corporate violators of federal law),20 deposits into the Fund fluctuate from year to year and sometimes decrease, as they did from FY2015 to FY2016. Further, DOJ has identified the prosecution of violent offenders as a priority.21 While this does not mean that prosecutions against corporate offenders that pay substantial criminal fines will decline, if these prosecutions were to decline it may effect a further decline in the deposit amounts to the CVF.

Caps on the CVF

In the history of the CVF, two caps have affected the balance and distribution of the Fund: a cap on deposits and an obligation cap.

Cap on Deposits

In 1984, Congress placed a cap on how much could be deposited into the CVF each fiscal year. As shown in Table 1, from FY1985 through FY1992, the annual cap on deposits ranged from $100 million to $150 million. In 1993, Congress lifted the cap on deposits, establishing that all criminal fines, special assessments, and forfeited bail bonds could be deposited into the CVF.

Obligation Cap

From FY1985 to FY1998, deposits collected each fiscal year were distributed the following fiscal year to support crime victim services. In 2000, Congress established an annual obligation cap on the amount of CVF funds available for distribution to reduce the effect of fluctuating deposits and ensure the stability of funds for related programs and activities. Congress establishes the CVF cap each year as a part of the appropriations for DOJ.

Recent Changes to the CVF Obligation Cap

In FY2015, Congress set the CVF obligation cap at $2.361 billion, a 216.9% increase over the FY2014 cap (see Table 1). Unlike subsequent fiscal years, Congress did not direct DOJ to use any of the additional funding for purposes other than those specified in VOCA, which was distributed to crime victims programs according to the formula established by VOCA.

In FY2016, Congress further increased the obligation cap to $3.042 billion; however, $379 million was transferred to the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) for purposes outside of VOCA and $10 million was designated for the DOJ Office of the Inspector General (OIG) for oversight and auditing purposes.22 After deducting the transfers required by P.L. 114-113, the obligation cap was $2.653 billion, a 12.4% increase over the FY2015 cap.

In FY2017, however, Congress set the cap at $2.573 billion, a 15.4% decrease compared to the FY2016 cap. From this amount, $326 million was transferred to OVW (again for purposes outside of VOCA) and $10 million was again designated for the DOJ OIG for oversight and auditing purposes. In the accompanying explanatory statement for the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017 (Division B, P.L. 115-31), Congress explained that deposits into the CVF had slowed, and to ensure solvency of the Fund the FY2017 obligation cap was calculated based on the three-year average of deposits into the CVF. In the years since, Congress has continued to calculate the annual obligation cap in this manner.

From FY2018 to FY2020, Congress continued to transfer funds from the CVF to OVW and OIG. In addition, in FY2018 Congress set aside 3% of the cap (off the top before any other funds are allocated) for tribal assistance grants. In FY2019 and FY2020, Congress set aside 5% of the cap for these grants.

Carryover Balance of the CVF

|

CVF and CHIMPs Federal spending can be divided into the budget categories of discretionary spending, mandatory spending, and net interest. In certain circumstances, reductions in mandatory spending can generate offsets that allow higher levels of discretionary spending than would otherwise be permitted under congressional budget rules or under statutory caps on discretionary spending. CHIMPs are provisions in appropriations acts that reduce or constrain mandatory spending, and they can provide offsets to discretionary spending. The obligation limitation on the CVF has been the CHIMP item that has generated the largest offset of discretionary spending in recent years.23 |

Funding for a current fiscal year's grants is provided by the previous fiscal year's deposits to the CVF, and the OVC is authorized to use the capped amount for grant awards in a given fiscal year. After the yearly allocations are distributed, the remaining balance in the CVF is retained for future obligation. The difference between the fund's balance and the obligation limit is scored as an offset (i.e., as a Change in Mandatory Program or CHIMP) in DOJ's total discretionary spending in a given fiscal year.24 Moreover, that offset also affects the discretionary spending total in the annual Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies (CJS) appropriations act.25

VOCA law requires that all sums deposited in a fiscal year that are not obligated must remain in the CVF for obligation in future fiscal years.26 If collections in a previous year exceed the obligation cap, amounts over the cap are credited to the CVF, also referred to as the "rainy day" fund, for future program benefits. For example, in FY2000 the obligation limit was set at $500 million despite the fact that deposits were over $985 million in FY1999. In FY2000, approximately $485 million remained in the CVF and was credited for future use.27 Table 1 provides the balances that remain credited to the CVF at the end of each fiscal year from FY2000 through FY2019.

|

Fiscal |

Amount Collected to CVF |

Enacted Cap on CVF Deposits |

Obligation Cap on CVF |

Funds Made Available for Distributiona |

|

|

1985 |

$68.3 |

$100 |

— |

$68.3 |

— |

|

1986 |

62.5 |

$110 |

— |

62.5 |

— |

|

1987 |

77.5 |

$110 |

— |

77.5 |

— |

|

1988 |

93.6 |

$110 |

— |

93.6 |

— |

|

1989 |

133.5 |

$125 |

— |

124.2 |

— |

|

1990 |

146.2 |

$125 |

— |

127.2 |

— |

|

1991 |

128.0 |

$150 |

— |

128.0 |

— |

|

1992 |

221.6 |

$150 |

— |

152.2 |

— |

|

1993 |

144.7 |

— |

— |

144.7 |

— |

|

1994 |

185.1 |

— |

— |

185.1 |

— |

|

1995 |

233.9 |

— |

— |

233.9 |

— |

|

1996 |

528.9 |

— |

— |

528.9 |

— |

|

1997 |

362.9 |

— |

— |

362.9 |

— |

|

1998 |

324.0 |

— |

— |

324.0 |

— |

|

1999 |

985.2 |

— |

— |

500.0 |

— |

|

2000 |

777.0 |

— |

500.0 |

537.5 |

485.2 |

|

2001 |

544.4 |

— |

537.5 |

550.0 |

785.2 |

|

2002 |

519.5 |

— |

550.0 |

600.0 |

792.0 |

|

2003 |

361.3 |

— |

600.0 |

617.6b |

718.9 |

|

2004 |

833.7 |

— |

621.3c |

671.3d |

422.1 |

|

2005 |

668.3 |

— |

620.0 |

620.0 |

1,307.4 |

|

2006 |

641.8 |

— |

625.0 |

625.0 |

1,333.5 |

|

2007 |

1,018.0 |

— |

625.0 |

625.0 |

1,784.0 |

|

2008 |

896.3 |

— |

590.0 |

590.0 |

2,084.0 |

|

2009 |

1,745.7 |

— |

635.0 |

635.0 |

3,146.5 |

|

2010 |

2,362.3 |

— |

705.0 |

705.0 |

4,801.5 |

|

2011 |

1,998.0 |

— |

705.0 |

705.0 |

6,099.7 |

|

2012 |

2,795.5 |

— |

705.0 |

705.0e |

8,186.1 |

|

2013 |

1,489.6 |

— |

730.0 |

730.0e |

9,004.0 |

|

2014 |

3,591.0 |

— |

745.0 |

745.0e |

11,842.0 |

|

2015 |

2,640.0 |

— |

2,361.0 |

2,361.0e |

12,130.0 |

|

2016 |

1,486.4 |

— |

3,042.0f |

9,093.0 |

|

|

2017 |

6,583.9 |

— |

2,573.0f |

2,237.0 |

13,082.0 |

|

2018 |

444.8 |

— |

4,436.0f |

3,934.0 |

9,171.0 |

|

2019 |

524.0 |

— |

3,353.0f |

2,845.5 |

6,353.0 |

|

2020 |

— |

— |

2,641.0f |

2,064.0 |

— |

Source: FY1985-FY2019 data were provided by the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs. Obligation cap amounts are taken from appropriations law. The FY2020 obligation cap amount was taken from the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-93).

Notes: The Director of the OVC is authorized to set aside $50 million of CVF money in the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve to respond to the needs of victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and subsequently to replenish any amounts expended so that not more than $50 million is reserved in any fiscal year for any future victims of terrorism and/or mass violence. These funds do not fall under the annual cap of the CVF. Initial amounts set aside after 9/11 are reflected in footnotes b and d below, but amounts beyond those years are not provided in this table.

a. This column refers to funds administered by the OVC. From FY1985 to FY1998, deposits collected in each fiscal year were distributed in the following fiscal year to support crime victim services. From FY1985 to FY2002, the funds made available for distribution reflect the amounts distributed in the following fiscal year.

b. FY2003 funds include $17.6 million for the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve.

c. The original cap of $625.0 million was reduced due to congressional rescission.

d. FY2004 funds include $50.0 million for the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve.

e. Beginning in FY2012, the Office of Justice Programs (OJP) assessed management and administrative (M&A) costs for some programs funded by the CVF, but these amounts are not reflected here. See each individual program's respective table in this report. In FY2016, the total M&A cost assessment for VOCA programs (with the exception of the Children's Justice Act and victim compensation grant programs, which are not assessed this cost) was $78.1 million.

f. From FY2016 to FY2020, Congress transferred funds from the obligation capped amount to the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) and the DOJ Office of the Inspector General (OIG). Both amounts are reduced from the obligation capped amount before running the VOCA formula. The amount for OIG has been $10.0 million each year from FY2016-FY2020, but the amount transferred for OVW has varied. In 2016, P.L. 114-113 transferred $379.0 million to OVW, and from FY2017-FY2020 P.L. 115-31 transferred $326.0 million, P.L. 115-141 transferred $492.0 million, P.L. 116-6 transferred 497.5 million, and P.L. 116-93 transferred $435.0 million, respectively.

g. The FY2016-FY2020 distribution amounts reflect the deductions of the transfers to OVW and OIG highlighted in note f above.

Distribution of the Crime Victims Fund

As previously discussed, the OVC awards CVF money through formula and discretionary grants to states, local units of government, individuals, and other entities. The OVC also awards CVF money to specially designated programs. Grants are allocated as required by VOCA (see Figure 1). The programs supported with funding from the CVF are discussed in more detail below.

|

Figure 1. Annual VOCA-Authorized Distribution of the Crime Victims Fund |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office for Victims of Crime, Crime Victims Fund, Figure 2, https://www.ovc.gov/pubs/crimevictimsfundfs/intro.html; and U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs. Notes: This figure illustrates the annual distribution process as authorized under VOCA. From FY2018 to FY2020, Congress set aside 3%, 5%, and 5%, respectively, of the annual cap (off the top) for tribal assistance grants. Beginning in FY2012, OJP assessed management and administration (M&A) costs for programs funded by the CVF. OJP does not assess M&A costs for the Children's Justice Act Program and state victim compensation grants. In FY2012, state victim assistance grants were assessed 11.6% in M&A costs and all other CVF-funded grants were assessed 8.1% in M&A costs. In FY2013, state victim assistance grants were assessed 9.9% in M&A costs and all other CVF-funded grants were assessed 7.4% in M&A costs. In FY2014, CVF grants were assessed a 7.9% M&A costs. In FY2015, CVF grants were assessed 2.7% ($59.96 million) in M&A costs. OJP reduced the percentage for FY2015 due to the substantial increase in the obligation cap for that year, and has generally kept a similar percentage over the last several years. From FY2016 through FY2020, CVF grants were assessed $78.06 million, $92.01 million, $82.16 million, $80.90 million, and $81.77 million, respectively. a. As of FY2020, there were 192 Victim Witness Coordinators supported by the CVF. b. As of FY2020, there were 186 Victim Witness Specialists supported by the CVF. |

Children's Justice Act Program

The OVC and the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) manage the Children's Justice Act Program, a grant program designed to improve the investigation, handling, and prosecution of child abuse cases. Up to $20 million must be distributed annually to the Children's Justice Act Program.28 Of the designated funds, ACF receives up to $17 million to manage this program for the states, while the OVC distributes up to $3 million for tribal populations.29 In FY2020, the ACF received $17 million from the CVF to fund the Children's Justice Act Program. Table 2 provides funding data from FY2016 to FY2020.

|

Allocation Type (Administrative Agency in Parentheses) |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

State Allocation (ACF) |

$10.36a |

$17.00 |

$15.97a |

$15.74a |

$17.00 |

|

Tribal Allocation (OVC) |

3.00 |

2.95b |

3.00 |

3.00 |

NA |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs.

Notes: As of the date of publication, the FY2020 tribal allocation amount was not yet determined.

a. HHS had carryover funding from the previous fiscal year, and did not need the full allocation for this fiscal year.

b. According to OVC, the awards did not cover the full $3 million in this year as applications came with lower cost proposals.

Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys (EOUSA)

The OVC provides annual funding to support victim-witness coordinators within each of the 93 U.S. Attorney's Offices and 12 victim-witness coordinators exclusively serving Indian Country.30 In accordance with the Attorney General Guidelines for Victim and Witness Assistance,31 these personnel provide direct support for victims of federal crime by assisting victims in criminal proceedings and advising them of their rights, such as their right to make oral and written victim impact statements at an offender's sentencing hearing. Table 3 provides the number of full-time employees supported with CVF funding and the amount of CVF funding that the EOUSA victim-witness coordinator program received from the OVC from FY2016 to FY2020.

Table 3. Annual Allocation and Full-Time Employees (FTEs) for EOUSA Victim Witness Coordinators

(dollars in millions)

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

|

Allocation to EOUSA |

$29.38 |

$19.86 |

$27.77 |

$26.00 |

$25.71 |

|

Number of FTEs |

213 |

180 |

181 |

193 |

192 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs. Allocation figures reflect final enacted levels including reductions for management and administrative (M&A) costs. For more information on the M&A cost assessment for CVF programs, see the notes of Figure 1.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

The OVC provides annual funding to support victim witness specialists within the 56 FBI field offices.32 These specialists, or coordinators, personally assist victims of federal crime and provide information on criminal cases throughout case development and court proceedings.33 Table 4 provides the amount of CVF funding that the FBI's Victim Witness Program received from the OVC from FY2016 to FY2020.

Table 4. Annual Allocation and Full-Time Employees for FBI Victim Witness Specialists

(dollars in millions)

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

|

Allocation to FBI |

$17.29 |

$13.95 |

$28.11 |

$29.34 |

$34.00 |

|

Number of FTEs |

192 |

203 |

227 |

186 |

206 |

Source: Allocations and FTE numbers were provided by U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs. Allocation figures reflect final enacted levels including reductions for M&A costs. For more information on the M&A cost assessment for CVF programs, see the notes of Figure 1.

The Victim Notification System

The OVC provides annual funding to support the Victim Notification System (VNS), a program administered by the EOUSA and jointly operated by the FBI, EOUSA, OVC, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons.34 VNS is the vehicle through which victims of federal crime35 are notified of major case events relating to the offender, such as the release or detention status of the offender.36 Table 5 provides the amount of CVF funding that the VNS received from the OVC from FY2016 to FY2020.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

|

Allocation to EOUSA |

$4.03 |

$7.45a |

$5.23 |

$4.85 |

$5.44 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs. Allocation figures reflect final enacted levels including reductions for M&A costs. For more information on the M&A cost assessment for CVF programs, see the notes of Figure 1.

a. The FY2017 amount for the VNS included an extra $3.00 million allocated specifically to upgrade, enhance, and operate the VNS.

Victim Compensation and Assistance

After the Children's Justice Act, victim witness, and VNS programs are funded, remaining CVF money under the obligation cap is distributed as follows: Victim Compensation Formula Grants (47.5%); Victim Assistance Formula Grants (47.5%); and OVC Discretionary Grants (5%).37 Amounts not used for state compensation grants are made available for state victim assistance formula grants.

Victim Compensation Formula Grant Program

As mentioned, 47.5% of the remaining annual CVF money is for grant awards to state crime victim compensation programs.38 All 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and Puerto Rico have victim compensation programs.39 The OVC awards each state 60% of the total amount the state paid (from state funding sources) to victims in the prior fiscal year.40

According to VOCA, a state is eligible to receive a victim compensation formula grant if the state program meets the following requirements: (1) promotes victim cooperation with requests of law enforcement authorities, (2) certifies that grants received will not be used to supplant state funds, (3) ensures that non-resident victims receive compensation awards on the same basis as victims residing within the state, (4) ensures that compensation provided to victims of federal crimes is given on the same basis as the compensation given to victims of state crime, and (5) provides compensation to residents of the state who are victims of crimes occurring outside the state.41

Grant funds may be used to reimburse crime victims for out-of-pocket expenses such as medical and mental health counseling expenses, lost wages, funeral and burial costs, and other costs (except property loss, with limited exceptions)42 authorized in a state's compensation statute. Victims are reimbursed for crime-related expenses that are not covered by other resources, such as private insurance. From FY1999 to FY2016, medical and dental services accounted for close to half of the total payout in annual compensation expenses.43 In FY2017, 37.0%, or $136.67 million, of the total payments were for medical and dental expenses.44 According to OVC data, assault victims represent the highest percentage of victims receiving compensation each year.45 Victims of assault represented 36.0% all claims paid46 during FY2017.

Table 6 provides the amount of CVF funding that was allocated to OVC's Victim Compensation Program from FY2015 to FY2019.

|

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

|

Allocation for Compensation Grants |

$141.29 |

$164.42 |

$103.80 |

$178.84 |

$135.35 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs.

Notes: At the time of publication, the FY2020 allocation amount had not yet been determined.

Victim Assistance Formula Grant Program

The other 47.5% of the remaining annual CVF money (see Figure 1) is for the Victim Assistance Formula Grants Program. Amounts not used for state compensation grants are made available for the Victim Assistance Formula Grants Program. This program provides grants to state crime victim assistance programs to administer funds for state and community-based victim service program operations.47 The grants support direct services to crime victims including information and referral services, crisis counseling, temporary housing, criminal justice advocacy support, and other assistance needs.

Assistance grants are distributed by states according to guidelines established by VOCA. States are required to prioritize the following groups: (1) underserved populations of victims of violent crime,48 (2) victims of child abuse, (3) victims of sexual assault, and (4) victims of spousal abuse.49 States may not use federal funds to supplant state and local funds otherwise available for crime victim assistance.

VOCA establishes the amount of funds allocated to each state and territory. Each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico receive a base amount of $500,000 each year.50 The territories of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, and American Samoa receive a base amount of $200,000 each year.51 The remaining funds are distributed based on U.S. census population data. Table 7 provides the amount of CVF funding that the OVC allocated for the Victim Assistance Grant Program from FY2015 to FY2019.

|

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

|

Allocation for Assistance Grants |

$1,958.83 |

$2,219.90 |

$1,1846.51 |

$3,328.06 |

$2,253.33 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs.

Notes: At the time of publication, the FY2020 allocation amount had not yet been determined. Allocation figures reflect final enacted levels including reductions for M&A costs. For more information on the M&A cost assessment for CVF programs, see the notes of Figure 1.

According to the OVC, domestic or family violence victimizations made up the largest victimization type among those receiving services under the Victim Assistance Formula Grants Program in FY2017; 43.0% of the 5,088,858 victims served by these grants reported family or domestic violence victimization.52 This percentage has remained relatively stable, although it has declined slightly since 2000, when 50.1% of all victims served by the victim assistance grants were victims of domestic or family violence.53

Discretionary Grants

Five percent of the CVF money available annually (after the specially designated program allocations have been made; see Figure 1) is for discretionary grants.54 According to VOCA, discretionary grants must be distributed for (1) demonstration projects, program evaluation, compliance efforts, and training and technical assistance services to crime victim assistance programs; (2) financial support of services to victims of federal crime; and (3) nonprofit victim service organizations and coalitions to improve outreach and services to victims of crime.55 The OVC awards discretionary grants each year through a competitive application process.56

Table 8 provides the amount of CVF funding that the OVC allotted for discretionary grants from FY2016 to FY2020.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

|

Allocation for Discretionary Grants |

$126.56 |

$103.80 |

$178.84 |

$125.90 |

$94.85 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs. Allocation figures reflect final enacted levels including reductions for M&A costs. For more information on the M&A cost assessment for CVF programs, see the notes of Figure 1.

Notes: The allocations reflect the funds allocated for, but not necessarily committed to, discretionary grants. For example, in FY2016, $125.27 million was committed for discretionary grants ($1.29 million less than the annual allocation).

Survivors' Bill of Rights Act of 2016

The Survivors' Bill of Rights Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-236) established statutory rights for sexual assault survivors in the federal justice system.57 The act requires CVF funds made available to U.S. Attorneys and the FBI (see "Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys (EOUSA)" and "Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)")58 for victim and witness assistance to be used to carry out the requirements of the act, subject to specified exceptions. Further, it authorizes OVC to make grants to states (using discretionary grant funds) to develop sexual assault survivors' rights and policies and to disseminate written notice of such rights and policies to medical centers, hospitals, forensic examiners, sexual assault service providers, law enforcement agencies, and other state entities.

Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve

The Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve was established under P.L. 104-132 to meet the immediate and long-term needs of victims of terrorism and mass violence.59 The OVC accomplishes this mission by providing supplemental grants to state and local jurisdictions (where an incident has occurred) for victim compensation and assistance and by providing direct compensation to victims (U.S. nationals or officers or employees of the U.S. government, including Foreign Service Nationals working for the U.S. government) of terrorist acts that occur abroad.

The Director of the OVC is authorized to set aside $50 million of CVF money in the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve to respond to the needs of victims of the September 11 terrorist attacks, and subsequently, to replenish any amounts expended so that not more than $50 million is reserved in any fiscal year for any future victims of terrorism.60 After funding all other program areas, as listed above, the funds retained in the CVF may be used to replenish the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve.61 This reserve fund supports the following programs:

- Antiterrorism and Emergency Assistance Program (AEAP),

- International Terrorism Victim Expense Reimbursement Program,

- Crime Victim Emergency Assistance Fund at the FBI, and

- Victim Reunification Program.

Table 9 provides the amounts of funding that OVC has committed from the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve from FY2015 to FY2019.

|

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

|

Obligations for Programs Funded by the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve |

$8.01 |

$12.32 |

$36.57 |

$7.29 |

$26.79 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legislative Affairs.

Notes: Funds may be obligated to the following programs that are funded by the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve: the Antiterrorism and Emergency Assistance Program, International Terrorism Victim Expense Reimbursement Program, Crime Victim Emergency Assistance Fund at the FBI, and Victim Reunification Program. For grant award data, see U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, OJP Award Data, https://www.ojp.gov/funding/explore/ojp-award-data.

Assistance for Victims of Terrorism and Mass Violence

Over the past few years, the OVC has responded to several incidents of terrorism and/or mass violence in the United States with grants from the AEAP. Following incidents of terrorism or mass violence, jurisdictions62 may apply for AEAP funds for crisis response, criminal justice support, crime victim compensation, and training and technical assistance expenses. In 2019, for example, OVC awarded $16.7 million to the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services and $8.4 million to the California Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board to support victims of the mass violence shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas on October 1, 2017.63 A gunman killed 58 people and injured at least 622 others. Funding supported "supplemental crisis response and consequence management services to help victims continue to heal and cope with probable re-traumatization."64

Assistance for Victims of 9/11

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the OVC used money available in the Antiterrorism Emergency Reserve account to respond to the needs of victims. The OVC awarded $3.1 million in victim assistance funding and $13.5 million in victim compensation funding65 to the states of New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania.66 The funds were used by these states to coordinate and provide emergency assistance to victims in the form of crisis counseling and other direct services, and to offset out-of-pocket expenses for medical and mental health services, funeral costs, and lost wages.

In addition to providing funds to states, the OVC provided other assistance and services, including the following:

- OVC staff worked to identify the short- and long-term needs of victims and related costs, as well as to coordinate its efforts with other federal agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

- Immediately following the attacks, the OVC set up a call center that offered a 24-hour, toll-free telephone line for collecting victim information and providing referrals for financial, housing, and counseling assistance. Approximately 37,000 victims and family members received assistance and referrals through the call center.67

- The OVC also established a Victim and Family Travel Assistance Center, which handled all logistical arrangements and paid travel and lodging costs for 1,800 family members traveling to funerals and memorial services.68

- The OVC designed and operated a special "Hope and Remembrance" website to provide victims with answers to frequently asked questions, official messages from U.S. government sources, news releases, etc.69

Child Pornography Victims Reserve

The Child Pornography Victims Reserve was established under the Amy, Vicky, and Andy Child Pornography Victim Assistance Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-299).70 Among other changes, the act authorized a one-time $35,000 payment (adjusted for inflation) to victims of child pornography trafficking offenses. The Child Pornography Victims Reserve was established within the Crime Victims Fund to provide funding for these payments. Courts must impose additional assessments on persons convicted of child pornography offenses,71 and the additional assessments must be deposited into the Child Pornography Victims Reserve.

The Director of OVC may set aside up to $10 million of the amounts remaining in the CVF in any fiscal year (after distributing the amounts for VOCA programs listed in Figure 1) for the Child Pornography Victims Reserve, which may be used by the Attorney General for payments under 18 U.S.C. Section 2259(d). Amounts in the reserve may be carried over from fiscal year to fiscal year, but the total amount of the reserve shall not exceed $10 million.72 As of February 29, 2020, $52,075 had been collected into the reserve fund, and no receipts had been used yet on OVC programs.73

Selected Issues

Congress may confront several issues when considering the balance of the CVF, the annual obligation cap on the CVF, and possible amendments to VOCA. These issues include using the CVF for purposes other than those explicitly authorized by VOCA, the solvency of the Fund, eliminating the annual obligation cap, and amending VOCA to accommodate new programs or to adjust the allocation formula. Congress may also consider the purposes for which certain pools of victim services monies can be used.

Issues in Considering the Balance of the Fund

Because the CVF balance remains larger than the amount distributed to victims each year, there are several issues Congress may consider, and in some cases already has considered, regarding the balance of the Fund. One is whether to use receipts from the CVF to fund grant programs that are not authorized by VOCA. In the past, Congress has passed legislation that made CVF money available to support programs authorized outside of VOCA.74 For example, the National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 110-181) included a provision mandating that the Attorney General transfer from the emergency reserve of the CVF "such funds as may be required" to cover the costs of special masters appointed by U.S. district courts in civil cases brought against state sponsors of terrorism. Until FY2016, CVF money had not been used to fund grant programs outside of those authorized by VOCA; however, in the FY2016 through FY2020 CJS appropriations acts,75 CVF funds were transferred to OVW to be used for specified grant programs authorized under the Violence Against Women Act.76

While it could be argued that funds for the non-VOCA grant programs described above still support crime victims, it raises a question about whether these actions might pave the way for the CVF to be used to support grant programs that are not victim-focused. On the other hand, the CVF has a balance of more than $6 billion, which indicates that receipts to the Fund, for certain years, exceed the congressionally specified cap and that the extra funds could be used for other justice system needs. However, as mentioned, Congress already substantially increased the cap in FY2015 and more or less sustained the increased level since then (see Table 1). In addition, deposits into the Fund have decreased over the last two years. In a time of fiscal constraint, the CVF might provide an avenue to fund some DOJ grant programs while reducing DOJ's discretionary appropriation (i.e., grants funded through transfers from the CVF do not have to be funded through discretionary appropriations); however, as shown by the drop in CVF deposits over the last couple of years, there is no guarantee that receipts going into the CVF would be able to sustain a higher obligation cap. Therefore, if Congress were to increase the cap and continue or expand funding from the CVF for non-VOCA programs, it may not be possible to ensure that there will be a consistent level of funding to support these programs in future fiscal years.

Congress may also decide to rescind funds from the balance of the CVF, as it did in November 2015 through the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74). This law required the permanent cancellation of $1.5 billion from the balance of the CVF.77 This cancellation did not carry any specification as to any redirection for the funds, but rather was treated as a general offset. This action did not impact, at least not directly, the annual obligation cap on the CVF.

Congress could decide to eliminate the cap on the Crime Victims Fund altogether. If Congress should decide to eliminate the cap and allow all collected funds to be distributed in a given fiscal year, it could possibly have significant consequences for DOJ's budget. As mentioned, the difference between the obligation cap and the balance on the CVF is treated as a CHIMP and is scored as a credit against DOJs discretionary appropriations. Therefore, if Congress were to eliminate the cap, it would no longer have the CHIMP to offset some discretionary appropriations and this might result in Congress having to reduce discretionary funding for some DOJ programs (assuming that Congress did not increase the discretionary spending limit for CJS to offset eliminating the CHIMP). Moreover, Congress may consider whether VOCA programs would be able to use all the money in the fund if the obligation cap were eliminated.

Deposits into the Fund

Some victim advocates have expressed concern that funds collected from deferred and non-prosecution agreements between DOJ and defendants are not being deposited into the CVF, resulting in fewer deposits into the Fund.78 While criminal fines are deposited into the CVF, penalty assessments collected as part of a deferred or non-prosecution agreement between DOJ and defendants are not deposited into the CVF. For example, in December 2019 HSBC Private Bank (Suisse) SA (HSBC Switzerland) admitted to helping U.S. taxpayers conceal income and assets from the United States, and agreed to pay $192.4 million as part of a deferred prosecution agreement with DOJ. The $192.4 million penalty had three parts. First, $60.6 million was for restitution to the Internal Revenue Service, which represented the unpaid taxes resulting from HSBC Switzerland's participation in the conspiracy. Second, HSBC Switzerland forfeited $71.9 million to the United States, which represented gross fees (not profits) that the bank earned on its undeclared accounts between 2000 and 2010. Finally, HSBC Switzerland agreed to pay a penalty of $59.9 million.79 None of these funds went to the CVF. If DOJ had instead sought a criminal conviction involving the collection of criminal fines, those funds would have been deposited into the CVF.

According to DOJ, "in certain instances, it may be appropriate to resolve a corporate criminal case by means other than indictment. Non-prosecution and deferred prosecution agreements, for example, occupy an important middle ground between declining prosecution and obtaining the conviction of a corporation."80 It is unclear if DOJ has increased use of deferred and non-prosecution agreements in recent years. If Congress prefers that assessments collected as a result of deferred and non-prosecution agreements be deposited into the CVF, then it may amend VOCA to require this action.

Issues in Considering Amendments to VOCA

While VOCA may be amended in many possible ways, this report presents two options (beyond what has been discussed thus far) that Congress may choose to consider. Congress may decide to reassess the allocation formula of the CVF (see Figure 1) or consider adding new programs to be supported through the CVF.

VOCA Assistance Administrators have voiced concern that fluctuations in annual obligations can directly affect fund availability for victim assistance formula grants and, to a lesser extent, discretionary grants. The addition of new programs, increases in funding to other programs funded by the CVF, and new management and administration costs cause a reduction in funding available for victim assistance formula grants and discretionary grants. Congress may choose to review the allocation formula to determine if changes should be made to reduce the effect of fluctuations in obligated funds on these grants.

Since 1984, VOCA has been amended several times to support additional victim-related activities and accommodate the needs of specific groups of victims, such as child abuse victims and victims of terrorist acts. Congress may choose to continue amending VOCA to further accommodate the needs of additional special populations, such as victims of elder abuse and rural victims. While support for victims of elder abuse is an allowable use of the Fund, as the "baby boom" generation ages, it is possible that elder abuse will continue to grow as a social concern.81 For example, Congress may wish to consider expanding allowable uses of compensation funds to include property loss compensation for elder victims of financial fraud. Currently, VOCA funds may not be used to compensate for property loss (with limited exceptions). Similarly, victims in rural areas are supported through VOCA programs, but they face unique barriers to assistance such as lack of qualified service professionals and higher costs and limited availability of transportation to obtain services.82 Other populations with unique risks and needs may present themselves, and Congress may choose to use VOCA as one potential vehicle to address those risks and needs.