Introduction

This report provides background information and issues for Congress on the Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, a program carried out by the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) and the Navy that gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify Department of Defense (DOD) acquisition strategies and proposed funding levels for the Aegis BMD program. Congress's decisions on the Aegis BMD program could significantly affect U.S. BMD capabilities and funding requirements, and the BMD-related industrial base.

For an overview of the strategic and budgetary context in which the Aegis BMD program may be considered, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Background

Aegis Ships

All but three the Navy's cruisers and destroyers are called Aegis ships because they are equipped with the Aegis ship combat system—an integrated collection of sensors, computers, software, displays, weapon launchers, and weapons named for the mythological shield that defended Zeus. (The exceptions are the Navy's three Zumwalt [DDG-1000] class destroyers, which are discussed below.) The Aegis system was originally developed in the 1970s for defending ships against aircraft, anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), surface threats, and subsurface threats. The system was first deployed by the Navy in 1983, and it has been updated many times since. The Navy's Aegis ships include Ticonderoga (CG-47) class cruisers and Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class destroyers.

Ticonderoga (CG-47) Class Aegis Cruisers

A total of 27 CG-47s (CGs 47 through 73) were procured for the Navy between FY1978 and FY1988; the ships entered service between 1983 and 1994. The first five ships in the class (CGs 47 through 51), which were built to an earlier technical standard in certain respects, were judged by the Navy to be too expensive to modernize and were removed from service in 2004-2005, leaving 22 ships in operation (CGs 52 through 73).

Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) Class Aegis Destroyers1

A total of 62 DDG-51s were procured for the Navy between FY1985 and FY2005; the first entered service in 1991 and the 62nd entered service in FY2012. The first 28 ships are known as Flight I/II DDG-51s. The next 34 ships, known as Flight IIA DDG-51s, incorporate some design changes, including the addition of a helicopter hangar.

No DDG-51s were procured in FY2006-FY2009. The Navy during this period instead procured the three above-mentioned Zumwalt (DDG-1000) class destroyers. The DDG-1000 design does not use the Aegis system and does not include a capability for conducting BMD operations. Navy plans do not call for modifying the three DDG-1000s to make them BMD-capable.2

Procurement of DDG-51s resumed in FY2010, following procurement of the three Zumwalt-class destroyers. A total of 23 DDG-51s have been procured from FY2010 through FY2020. DDG-51s procured in FY2017 and subsequent years are being built to a new version of the DDG-51 design called the Flight III version. The Flight III version is to be equipped with a new radar, called the Air and Missile Defense Radar (AMDR) or the SPY-6 radar, that is more capable than the SPY-1 radar installed on all previous Aegis cruisers and destroyers.

Aegis Ships in Allied Navies

Sales of the Aegis system to allied countries began in the late 1980s. Allied countries that now operate, are building, or are planning to build Aegis-equipped ships include Japan, South Korea, Australia, Spain, and Norway.3 Most of Japan's Aegis-equipped ships are currently BMD-capable, and Japan plans to make all of them BMD-capable in coming years. The Aegis-equipped ships operated by South Korea, Australia, Spain, and Norway are currently not BMD-capable.

Aegis BMD System4

Aegis ships are given a capability for conducting BMD operations by incorporating changes to the Aegis system's computers and software, and by arming the ships with BMD interceptor missiles. In-service Aegis ships can be modified to become BMD-capable ships, and DDG-51s procured in FY2010 and subsequent years are being built from the start with a BMD capability.

Versions and Capabilities of Aegis BMD System

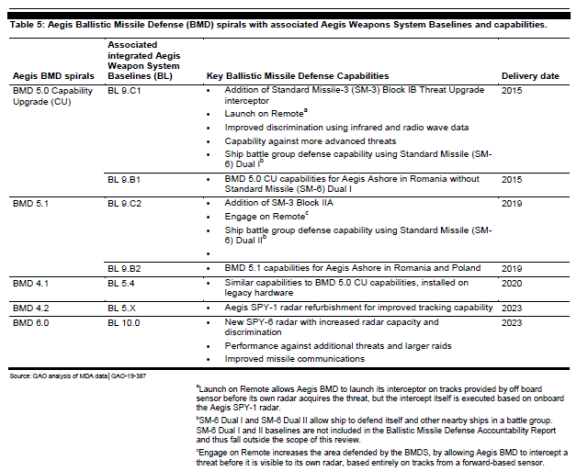

The Aegis BMD system exists in several variants. Listed in chronological order of development and deployment (and ascending level of capability), these include (but are not necessarily limited to) the 3.6.X variant, the 4.0.3 variant, the 4.1 variant, the 4.2 variant, the 5.0 CU (Capability Upgrade) variant, the 5.1 variant, and the 6.0 or 6.X variant. The BMD system variants correlate with certain versions (i.e., baselines, or BLs) of the overall Aegis system, which have their own numbering system. The more recent BMD variants, in addition to being able to address more challenging BMD scenarios, give BMD-equipped ships a capability to simultaneously perform both BMD operations against ballistic missiles and anti-air warfare (AAW) operations (aka air-defense operations) against aircraft and anti-ship cruise missiles. Figure 1 provides a 2019 Government Accountability Office (GAO) summary of the capabilities of the newer BMD variants and their correlation to Aegis system baselines.

The Aegis BMD system was originally designed primarily to intercept theater-range ballistic missiles, meaning short-, medium-, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs, MRBMs, and IRBMs, respectively). In addition to its capability for intercepting theater-range ballistic missiles, detection and tracking data collected by the Aegis BMD system's radar might be passed to other U.S. BMD systems that are designed to intercept intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), which might support intercepts of ICBMs that are conducted by those other U.S. BMD systems.

With the advent of the Aegis BMD system's new SM-3 Block IIA interceptor (which is discussed further in the next section), DOD is evaluating the potential for the Aegis BMD system to intercept certain ICBMs. Section 1680 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115-91 of December 12, 2017) directed DOD to "conduct a test to evaluate and demonstrate, if technologically feasible, the capability to defeat a simple intercontinental ballistic missile threat using the standard missile 3 block IIA missile interceptor." DOD's January 2019 missile defense review report states the following:

The SM-3 Blk IIA interceptor is intended as part of the regional missile defense architecture, but also has the potential to provide an important "underlay" to existing GBIs [ground-based interceptors] for added protection against ICBM threats to the homeland. This interceptor has the potential to offer an additional defensive capability to ease the burden on the GBI system and provide continuing protection for the U.S. homeland against evolving rogue states' long-range missile capabilities.

Congress has directed DoD to examine the feasibility of the SM-3 Blk IIA against an ICBM-class target. MDA will test this SM-3 Blk IIA capability in 2020. Due to the mobility of sea-based assets, this new underlay capability will be surged in a crisis or conflict to further thicken defensive capabilities for the U.S. homeland. Land-based sites in the United States with this SM-3 Blk IIA missile could also be pursued.5

A March 18, 2019, press report states the following:

The Pentagon plans a "first-of-its-kind" test of an unprecedented weapons capability to intercept and destroy an enemy Intercontinental Ballistic Missile "ICBM"—from a Navy ship at sea using a Standard Missile-3 Block IIA.

The concept, as articulated by Pentagon officials and cited briefly in this years' DoD "Missile Defense Review," would be to use an advanced SM-3 IIA to "underlay" and assist existing Ground-Based Interceptors (GBI), adding new dimensions to the current US missile defense posture.…

The testing, Pentagon officials tell Warrior, is slated for as soon as next year. The effectiveness and promise of the Raytheon-built SM-3 IIA shown in recent testing have inspired Pentagon weapons developers to envision an even broader role for the weapon. The missile is now "proven out," US weapons developers say….

"The SM-3 IIA was not designed to take out ICBMs, but is showing great promise. This would be in the upper range of its capability—so we are going to try," the Pentagon official told Warrior….

The SM-3 IIA's size, range, speed and sensor technology, the thinking suggests, will enable it to collide with and destroy enemy ICBMs toward the beginning or end of their flight through space, where they are closer to the boundary of the earth's atmosphere.

"The SM-3 IIA would not be able to hit an ICBM at a high altitude, but it can go outside the earth's atmosphere," the Pentagon official said. "You want to hit it as far away as possible because a nuke could go off."6

A March 26, 2018, press report states the following:

[MDA] Director Lt. Gen. Sam Greaves said MDA "is evaluating the technical feasibility of the capability of the SM-3 Block IIA missile, currently under development, against an ICBM-class target."

"If proven to be effective against an ICBM, this missile could add a layer of protection, augmenting the currently deployed GMD [ground-based missile defense] system," Greaves said in written testimony submitted March 22 to the Senate Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee. [Greaves] said MDA will conduct a demonstration of the SM-3 Block IIA against an ICBM-like target by the end of 2020."7

Aegis BMD Interceptor Missiles

The BMD interceptor missiles used by Aegis ships are the Standard Missile-3 (SM-3), the SM-2 Block IV, and the SM-6.

SM-3 Midcourse Interceptor

The SM-3 is designed to intercept ballistic missiles above the atmosphere (i.e., exo-atmospheric intercept), in the midcourse phase of an enemy ballistic missile's flight. It is equipped with a "hit-to-kill" warhead, called a kinetic vehicle, that is designed to destroy a ballistic missile's warhead by colliding with it. MDA and Navy plans call for fielding increasingly capable versions of the SM-3 in coming years. The current versions, called the SM-3 Block IA and SM-3 Block IB, are to be supplemented in coming years by SM-3 Block IIA.

Compared to the Block IA version, the Block IB version has an improved (two-color) target seeker, an advanced signal processor, and an improved divert/attitude control system for adjusting its course. Compared to the Block IA and 1B versions, which have a 21-inch-diameter booster stage at the bottom but are 13.5 inches in diameter along the remainder of their lengths, the Block IIA version has a 21-inch diameter along its entire length. The increase in diameter to a uniform 21 inches provides more room for rocket fuel, permitting the Block IIA version to have a burnout velocity (a maximum velocity, reached at the time the propulsion stack burns out) that is greater than that of the Block IA and IB versions, as well as a larger-diameter kinetic warhead. The United States and Japan have cooperated in developing certain technologies for the Block IIA version, with Japan funding a significant share of the effort.8

SM-2 and SM-6 Terminal Interceptors

The SM-2 Block IV is designed to intercept ballistic missiles inside the atmosphere (i.e., endo-atmospheric intercept), during the terminal phase of an enemy ballistic missile's flight. It is equipped with a blast fragmentation warhead. The existing inventory of SM-2 Block IVs—72 as of February 2012—was created by modifying SM-2s that were originally built to intercept aircraft and ASCMs. A total of 75 SM-2 Block IVs were modified, and at least 3 were used in BMD flight tests.

MDA and the Navy are now procuring a more-capable terminal-phase (endo-atmospheric intercept) BMD interceptor based on the SM-6 air defense missile (the successor to the SM-2 air defense missile). The SM-6 is a dual-capability missile that can be used for either air defense (i.e., countering aircraft and anti-ship cruise missiles) or ballistic missile defense. A July 23, 2018, press report states the following:

The Defense Department has launched a prototype project that aims to dramatically increase the speed and range of the Navy's Standard Missile-6 by adding a larger rocket motor to the ship-launched weapon, a move that aims to improve both the offensive and defensive reach of the Raytheon-built system.

On Jan. 17, the Navy approved plans to develop a Dual Thrust Rocket Motor with a 21-inch diameter for the SM-6, which is currently fielded with a 13.5-inch propulsion package. The new rocket motor would sit atop the current 21-inch booster, producing a new variant of the missile: the SM-6 Block IB.9

Aegis Ashore Sites in Romania and Poland

On September 17, 2009, the Obama Administration announced a new approach for regional BMD operations called the Phased Adaptive Approach (PAA). The first application of the approach is in Europe, and is called the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA). EPAA calls for using BMD-capable Aegis ships, a land-based radar in Europe, and two Aegis Ashore sites in Romania and Poland to defend Europe against ballistic missile threats from countries such as Iran.

Phase I of EPAA involved deploying Aegis BMD ships and a land-based radar in Europe by the end of 2011. Phase II involved establishing the Aegis Ashore site in Romania with SM-3 IB interceptors in 2016.10 Phase 3 involves establishing the Aegis Ashore site in Poland with SM-3 IIA interceptors. The completion of construction of the Poland site has been delayed by four years, to 2022, due to construction contractor performance issues.11 Each Aegis Ashore site in the EPAA is to include a structure housing an Aegis system similar to the deckhouse on an Aegis ship and 24 SM-3 missiles launched from a relocatable Vertical Launch System (VLS) based on the VLS that is installed in Navy Aegis ships.12

Although BMD-capable Aegis ships were deployed to European waters before 2011, the first BMD-capable Aegis ship officially deployed to European waters as part of the EPAA departed its home port of Norfolk, VA, on March 7, 2011, for a deployment to the Mediterranean that lasted several months.13

Numbers of BMD-Capable Aegis Ships

Under the FY2021 budget submission, the number of BMD-capable Navy Aegis ships is projected to increase from 48 at the end of FY2021 to 65 at the end of FY2025. The portion of the force equipped with earlier Aegis variants is decreasing, and the number equipped with later variants is increasing.

BMD-Capable Aegis Destroyers Forward-Homeported in Spain

On October 5, 2011, the United States, Spain, and NATO jointly announced that, as part of the EPAA, four BMD-capable U.S. Navy Aegis destroyers were to be forward-homeported (i.e., based) at the naval base at Rota, Spain.14 The four ships were transferred to Rota in FY2014 and FY2015.15 They are reportedly scheduled to return to the United States and replaced at Rota by a new set of four BMD-capable U.S. Navy Aegis destroyers in 2020-2022.16 Navy officials have said that the four Rota-based ships can provide a level of level of presence in the Mediterranean for performing BMD patrols and other missions equivalent to what could be provided by about 10 BMD-capable Aegis ships that are homeported on the U.S. east coast. The Rota homeporting arrangement thus effectively releases about six U.S. Navy BMD-capable Aegis ships for performing BMD patrols or other missions elsewhere.

In February and March 2020, DOD officials testified that DOD is considering forward-homeporting an additional two BMD-capable Aegis destroyers at Rota, which would make for a total of ships at the site.17 Navy officials have testified that they support the idea.18

Aegis BMD Development Philosophy and Flight Tests

The Aegis BMD development effort, including Aegis BMD flight tests, has been described as following a development philosophy long held within the Aegis program office of "build a little, test a little, learn a lot," meaning that development is done in manageable steps, then tested and validated before moving on to the next step.19 For a summary of Aegis BMD flight tests since 2002, see Appendix A.

Allied Participation and Interest in Aegis BMD Program

Japan20

Japan is modifying all six of its Aegis destroyers to include the Aegis BMD capability. As of August 2017, four of the six ships reportedly had been modified, and Japan planned to modify a fifth by March 2018, or perhaps sooner than that.21 In November 2013, Japan announced plans to procure two additional Aegis destroyers and equip them as well with the Aegis BMD capability, which will produce an eventual Japanese force of eight BMD-capable Aegis destroyers. The two additional ships are expected to enter service in 2020 and 2021. Japanese BMD-capable Aegis ships have participated in some of the flight tests of the Aegis BMD system using the SM-3 interceptor (see Table A-1 in Appendix A).

Japan cooperated with the United States on development the SM-3 Block IIA missile. Japan developed certain technologies for the missile, and paid for the development of those technologies, reducing the missile's development costs for the United States.

Japan plans to procure and operate two Aegis Ashore systems that reportedly are to be located at Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF) facilities in Akita Prefecture in eastern Japan and Yamaguchi Prefecture in western Japan, and would be operated mainly by the GSDF (i.e., Japan's army).22 The two systems reportedly will be equipped with a new Lockheed-made radar called the Long Range Discrimination Radar (LRDR) rather than the Raytheon-made SPY-6 AMDR that is being installed on U.S. Navy Flight III DDG-51s, and reportedly will go into operation by 2023.23

A July 6, 2018, press report states that "The U.S. and Japan are looking to jointly develop next-generation radar technology that would use Japanese semiconductors to more than double the detection range of the Aegis missile defense system."24

South Korea

An October 12, 2018, press report states that "the South Korean military has decided to buy ship-based SM-3 interceptors to thwart potential ballistic missile attacks from North Korea, a top commander of the Joint Chiefs of Staff revealed Oct. 12.25

Other Countries

Other countries that MDA views as potential naval BMD operators (using either the Aegis BMD system or some other system of their own design) include the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, Denmark, and Australia. Spain, South Korea, and Australia either operate, are building, or are planning to build Aegis ships. The other countries operate destroyers and frigates with different combat systems that may have potential for contributing to BMD operations.

FY2021-FY2025 MDA Procurement and R&D Funding

The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA's budget. The Navy's budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. Table 1 shows FY2021-FY2025 MDA procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts. Research and development funding for the land-based SM-3 is funding for Aegis Ashore sites. MDA's budget also includes additional funding not shown in the table for operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) for the Aegis BMD program.

Table 1. FY201-FY2025 MDA Procurement and R&D Funding for Aegis BMD Efforts

(In millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth; totals may not add due to rounding)

|

FY21 (req.) |

FY22 (proj.) |

FY23 (proj.) |

FY24 (proj.) |

FY25 (proj.) |

||

|

Procurement |

||||||

|

Aegis BMD (line 34) |

356.2 |

348.1 |

413.4 |

440.9 |

438.6 |

|

|

(SM-3 Block IB missile quantity) |

(34) |

(35) |

(41) |

(34) |

(33) |

|

|

Aegis BMD Advance Procurement (line 35) |

44.9 |

17.5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

SM-3 Block IIA (line 37) |

218.3 |

131.9 |

127.0 |

1,180.1 |

1,108.2 |

|

|

(SM-3 Block IIA missile quantity) |

(6) |

(3) |

(3) |

(51) |

(50) |

|

|

Aegis Ashore Phase III (line 40) |

39.1 |

26.2 |

3.9 |

2.4 |

1.0 |

|

|

Aegis BMD hardware and software (line 42) |

104.2 |

109.2 |

103.2 |

126.0 |

124.5 |

|

|

SUBTOTAL Procurement |

762.7 |

632.9 |

647.5 |

1,749.4 |

1,744.3 |

|

|

Research and development |

||||||

|

Aegis BMD (PE 0603892C) (line 82) |

814.9 |

674.8 |

553.4 |

478.0 |

449.1 |

|

|

Aegis BMD Test (PE 0604878C) (line 113) |

170.9 |

191.7 |

163.1 |

179.9 |

217.7 |

|

|

Land-based SM-3 (PE 0604880C) (line 115) |

56.6 |

43.7 |

29.1 |

31.5 |

27.9 |

|

|

SUBTOTAL RDT&E |

1,042.4 |

910.2 |

745.6 |

689.4 |

694.7 |

|

|

TOTAL |

1,805.1 |

1,543.1 |

1,393.1 |

2,438.8 |

2,439.0 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on FY2021 MDA budget submission.

Issues for Congress

FY2021 Funding Request

One issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA's FY2021 procurement and research and development funding requests for the program. In considering this issue, Congress may consider various factors, including whether the work that MDA is proposing to fund for FY2021 is properly scheduled for FY2021, and whether this work is accurately priced.

Delays in Delivery of New Assets for Aegis BMD Program

Another issue for Congress concerns delays in the delivery of new assets for the Aegis BMD program. A June 2019 GAO report on BMD program delivery delays states:

The Aegis BMD SM-3 Block IB program, which received full production authority early in fiscal year 2018 after years of delays, delivered 12 of 36 planned interceptors in fiscal year 2018. This shortfall was due to the discovery of a parts quality issue that necessitated suspending deliveries until MDA could complete an investigation of the issue's impact on the interceptor's performance. In addition, the Aegis BMD SM-3 Block IIA program delivered one of four planned test interceptors due to a flight test failure early in the year suspending further deliveries pending completion of a failure review board.

Moreover, according to MDA officials, construction contractor performance issues will result in the Aegis Ashore Missile Defense System Complex—Poland not being delivered until at least 18 months after the planned December 2018 date.… [T]his facility is central to MDA's plans for the EPAA Phase 3, such that a delay in the completion of this facility resulted in a delay in the planned EPAA Phase 3 delivery to the warfighter.26

Required vs. Available Numbers of BMD-Capable Aegis Ships

Another potential issue for Congress concerns required numbers of BMD-capable Aegis ships versus available numbers of BMD-capable Aegis ships. Some observers are concerned about the potential operational implications of a shortfall in the available number of BMD-capable relative to the required number. Regarding the required number of BMD-capable Aegis ships, an August 15, 2018, Navy information paper states the following:

The [Navy's] 2016 Force Structure Assessment [FSA]27 sets the requirement [for BMD-capable ships] at 54 BMD-capable ships, as part of the 104 large surface combatant requirement, to meet Navy unique requirements to support defense of the sea base and limited expeditionary land base sites….

The minimum requirement for 54 BMD ships is based on the Navy unique requirement as follows. It accepts risk in the sourcing of combatant commander (CCDR) requests for defense of land.

- 30 to meet CVN escort demand for rotational deployment of the carrier strike groups

- 11 INCONUS for independent BMD deployment demand

- 9 in forward deployed naval forces (FDNF) Japan to meet operational timelines in USINDOPACOM

- 4 in FDNF Europe for rotational deployment in EUCOM.28

Burden of BMD Mission on U.S. Navy Aegis Ships

A related potential issue for Congress is the burden that BMD operations may be placing on the Navy's fleet of Aegis ships, particularly since performing BMD patrols requires those ships to operate in geographic locations that may be unsuitable for performing other U.S. Navy missions, and whether there are alternative ways to perform BMD missions now performed by U.S. Navy Aegis ships, such as establishing more Aegis Ashore sites. A June 16, 2018, press report states the following:

The U.S. Navy's top officer wants to end standing ballistic missile defense patrols and transfer the mission to shore-based assets.

Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson said in no uncertain terms on June 12 that he wants the Navy off the tether of ballistic missile defense patrols, a mission that has put a growing strain on the Navy's hard-worn surface combatants, and the duty shifted towards more shore-based infrastructure.

"Right now, as we speak, I have six multi-mission, very sophisticated, dynamic cruisers and destroyers―six of them are on ballistic missile defense duty at sea," Richardson said during his address at the U.S. Naval War College's Current Strategy Forum. "And if you know a little bit about this business you know that geometry is a tyrant.

"You have to be in a tiny little box to have a chance at intercepting that incoming missile. So, we have six ships that could go anywhere in the world, at flank speed, in a tiny little box, defending land."

Richardson continued, saying the Navy could be used in emergencies but that in the long term the problem demands a different solution.

"It's a pretty good capability and if there is an emergent need to provide ballistic missile defense, we're there," he said. "But 10 years down the road, it's time to build something on land to defend the land. Whether that's AEGIS ashore or whatever, I want to get out of the long-term missile defense business and move to dynamic missile defense."

The unusually direct comments from the CNO come amid growing frustration among the surface warfare community that the mission, which requires ships to stay in a steaming box doing figure-eights for weeks on end, is eating up assets and operational availability that could be better used confronting growing high-end threats from China and Russia.

The BMD mission was also a factor in degraded readiness in the surface fleet. Amid the nuclear threat from North Korea, the BMD mission began eating more and more of the readiness generated in the Japan-based U.S. 7th Fleet, which created a pressurized situation that caused leaders in the Pacific to cut corners and sacrifice training time for their crews, an environment described in the Navy's comprehensive review into the two collisions that claimed the lives of 17 sailors in the disastrous summer of 2017.

Richardson said that as potential enemies double down on anti-access technologies designed to keep the U.S. Navy at bay, the Navy needed to focus on missile defense for its own assets.

"We're going to need missile defense at sea as we kind of fight our way now into the battle spaces we need to get into," he said. "And so restoring dynamic maneuver has something to do with missile defense.29

A June 23, 2018, press report states the following:

The threats from a resurgent Russia and rising China―which is cranking out ships like it's preparing for war―have put enormous pressure on the now-aging [U.S. Navy Aegis destroyer] fleet. Standing requirements for BMD patrols have put increasing strain on the U.S. Navy's surface ships.

The Navy now stands at a crossroads. BMD, while a burden, has also been a cash cow that has pushed the capabilities of the fleet exponentially forward over the past decade. The game-changing SPY-6 air and missile defense radar destined for DDG Flight III, for example, is a direct response to the need for more advanced BMD shooters. But a smaller fleet, needed for everything from anti-submarine patrols to freedom-of-navigation missions in the South China Sea, routinely has a large chunk tethered to BMD missions.

"Right now, as we speak, I have six multimission, very sophisticated, dynamic cruisers and destroyers―six of them are on ballistic missile defense duty at sea," Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson said during an address at the recent U.S. Naval War College's Current Strategy Forum. "You have to be in a tiny little box to have a chance at intercepting that incoming missile. So we have six ships that could go anywhere in the world, at flank speed, in a tiny little box, defending land."

And for every six ships the Navy has deployed in a standing mission, it means 18 ships are in various stages of the deployment cycle preparing to relieve them.

The Pentagon, led by Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, wants the Navy to be more flexible and less predictable―"dynamic" is the buzzword of moment in Navy circles. What Richardson is proposing is moving standing requirements for BMD patrols away from ships underway and all the associated costs that incurs, and toward fixed, shore-based sites, and also surging the Navy's at-sea BMD capabilities when there is an active threat....

In a follow-up response to questions posed on the CNO's comments, Navy spokesman Cmdr. William Speaks said the Navy's position is that BMD is an integral part of the service's mission, but where long-term threats exist, the Navy should "consider a more persistent, land-based solution as an option."

"This idea is not about the nation's or the Navy's commitment to BMD for the U.S. and our allies and partners―the Navy's commitment to ballistic missile defense is rock-solid," Speaks said. "In fact, the Navy will grow the number of BMD-capable ships from 38 to 60 by 2023, in response to the growing demand for this capability.

"The idea is about how to best meet that commitment. In alignment with our national strategic documents, we have shifted our focus in an era of great power competition―this calls us to think innovatively about how best to meet the demands of this mission and optimize the power of the joint force."...

While the idea of saving money by having fixed BMD sites and freeing up multimission ships is sensible, it may have unintended consequences, said Bryan McGrath, a retired destroyer skipper and owner of the defense consultancy The FerryBridge Group.

"The BMD mission is part of what creates the force structure requirement for large surface combatants," McGrath said on Twitter after Defense News reported the CNO's comments. "Absent it, the number of CG's and DDG's would necessarily decline. This may in fact be desirable, depending on the emerging fleet architecture and the roles and missions debate underway. Perhaps we need more smaller, multi-mission ships than larger, more expensive ones.

"But it cannot be forgotten that while the mission is somewhat wasteful of a capable, multi-mission ship, the fact that we have built the ships that (among other things) do this mission is an incredibly good thing. If there is a penalty to be paid in peacetime sub-optimization in order to have wartime capacity—should this not be considered a positive thing?"

McGrath went on to say that the suite of combat systems that have been built into Aegis have been in response to the BMD threat. And indeed, the crown jewels of the surface fleet―Aegis Baseline 9 software, which allows a ship to do both air defense and BMD simultaneously; the Aegis common-source library; the forthcoming SPY-6; cooperative engagement―have come about either in part or entirely driven by the BMD mission....

A Navy official who spoke on condition of anonymity, to discuss the Navy's shifting language on BMD, acknowledged the tone had shifted since the 2000s when the Navy latched onto the mission. But the official added that the situation more than a decade later has dramatically shifted.

"The strategic environment has changed significantly since the early 2000s―particularly in the western Pacific. We have never before faced multiple peer rivals in a world as interconnected and interdependent as we do today," the official said. "Nor have we ever seen technologies that could alter the character of war as dramatically as those we see emerging around us. China and Russia have observed our way of war and are on the move to reshape the environment to their favor."

In response to the threat and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis' desire to use the force more dynamically, the Navy is looking at its options, the official said. "This includes taking a look at how we employ BMD ships through the lens of great power competition to compete, deter and win against those who threaten us."30

A January 29, 2019, press report states the following:

The Navy is looking to get out of the missile defense business, the service's top admiral said today, and the Pentagon's new missile defense review might give the service the off-ramp it has been looking for to stop sailing in circles waiting for ground-based missile launches.

This wasn't the first time Adm. John Richardson bristled in public over his ships sailing in "small boxes" at sea tasked with protecting land, when they could be out performing other missions challenging Chinese and Russian adventurism in the South China Sea and the North Atlantic….

"We've got exquisite capability, but we've had ships protecting some pretty static assets on land for a decade," Richardson said at the Brookings Institute. "If that [stationary] asset is going to be a long-term protected asset, then let's build something on land and protect that and liberate these ships from this mission."

Japan is already moving down the path of building up a more robust ground-based sensor and shooter layer, while also getting its own ships out to sea armed with the Aegis radar and missile defense system, both of which would free up American hulls from what Richardson on Monday called "the small [geographic] boxes where they have to stay for ballistic missile defense."31

Allied Burden Sharing: U.S. vs. Allied Contributions to Regional BMD Capabilities

Another related potential issue for Congress concerns allied burden sharing—how allied contributions to regional BMD capabilities and operations compare to U.S. naval contributions to overseas regional BMD capabilities and operations, particularly in light of constraints on U.S. defense spending, worldwide operational demands for U.S. Navy Aegis ships, and calls by some U.S. observers for increased allied defense efforts. The issue can arise in connection with both U.S. allies in Europe and U.S. allies in Asia. Regarding U.S. allies in Asia, a December 12, 2018, press report states the following:

In June, US Navy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral John Richardson said during a speech at the US Naval War College that the US Navy should terminate its current practice of dedicating several US Navy warships solely for Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD).

Richardson wanted US warships to halt BMD patrols off Japan and Europe as they are limiting, restrictive missions that could be better accomplished by existing land-based BMD systems such as Patriot anti-missile batteries, the US Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile system and the Aegis Ashore anti-missile system.

In the months since dropping his bombshell, Richardson—and much of the debate—has gone quiet.

"My guess is the CNO got snapped back by the Pentagon for exceeding where the debate actually stood," one expert on US naval affairs told Asia Times.

But others agree with him. Air Force Lt Gen Samuel A Greaves, the director of the US Missile Defense Agency (MDA), acknowledges Richardson's attempts to highlight how these BMD patrols were placing unwelcome "strain on the (US Navy's) crews and equipment."

But there are complications. While it may free US Navy warships for sea-control, rather than land defense, there is a concern that next- generation hypersonic cruise missiles could defeat land-based BMD systems, such as Aegis Ashore, while the US Navy's Aegis-equipped warships offer the advantages of high-speed mobility and stealth, resulting in greater survivability overall.

As Japan prepares to acquire its first Aegis Ashore BMD system – and perhaps other systems such as the THAAD system which has been deployed previously in Romania and South Korea – the possibility that the US Navy will end its important BMD role represents abrupt change….

Japan's decision to deploy Aegis Ashore can fill in any gap created by a possible US Navy cessation of BMD patrols. "The land-based option is more reliable, less logistically draining, and despite being horrendously expensive, could be effective in the sense that it provides a degree of reassurance to the Japanese people and US government, and introduces an element of doubt of missile efficacy into [North Korean] calculations," said [Garren Mulloy, Associate Professor of International Relations at Daito Bunka University in Saitama, Japan], adding, however, that these systems could not cover Okinawa.

"Fixed sites in Japan could be vulnerable, and the Aegis vessels provide a flexible forward-defense, before anything enters Japanese airspace, but with obviously limited reactions times," Mulloy said. "Aegis Ashore gives more reaction time – but over Japanese airspace."…

The silence about this sudden possible shift in the US defense posture in the western Pacific is understandable: it is a sensitive topic in Washington and Tokyo. However, the Trump administration has urged its allies to pay more for their own defense needs and to support US troops deployed overseas.

Meanwhile, Tokyo needs to proceed cautiously given the likelihood that neighbors might view a move on BMD as evidence that Tokyo is adopting an increasingly aggressive defense posture in the region.

But for them, it is a no-win situation. If the US does ditch the BMD patrol mission, China and North Korea might view the shift as equally menacing given that it greatly enhances the US Navy's maritime warfare capabilities.32

Conversion of Hawaii Aegis Test Site

Another potential issue for Congress is whether to convert the Aegis test facility in Hawaii into an operational land-based Aegis BMD site. DOD's January 2019 missile defense review report states, in a section on improving or adapting existing BMD systems, that

Another repurposing option is to operationalize, either temporarily or permanently, the Aegis Ashore Missile Defense Test Center in Kauai, Hawaii, to strengthen the defense of Hawaii against North Korean missile capabilities. DoD will study this possibility to further evaluate it as a viable near-term option to enhance the defense of Hawaii. The United States will augment the defense of Hawaii in order to stay ahead of any possible North Korean missile threat. MDA and the Navy will evaluate the viability of this option and develop an Emergency Activation Plan that would enable the Secretary of Defense to operationalize the Aegis Ashore test site in Kauai within 30 days of the Secretary's decision to do so, the steps that would need to be taken, associated costs, and personnel requirements. This plan will be delivered to USDA&S, USDR&E, and USDP within six months of the release of the MDR.33

A January 25, 2019, press report states the following:

The Defense Department will examine the funding breakdown between the Navy and the Missile Defense Agency should the government make Hawaii's Aegis Ashore Missile Defense Test Center into an operational resource, according to the agency's director.

"Today, it involves both Navy resources for the operational crews—that man that site—as well as funds that come to MDA for research, development and test production and sustainment," Lt. Gen. Sam Greaves said of the test center when asked how the funding would shake out between the Navy and MDA should the Pentagon move forward with the recommendation.34

Potential Contribution from Lasers, Railguns, and Guided Projectiles

Another potential issue for Congress concerns the potential for ship-based lasers, electromagnetic railguns (EMRGs), and gun-launched guided projectiles (GLGPs, previously known as hypervelocity projectiles [HVPs]) to contribute in coming years to Navy terminal-phase BMD operations and the impact this might eventually have on required numbers of ship-based BMD interceptor missiles. Another CRS report discusses the potential value of ship-based lasers, EMRGs, and GLGPs for performing various missions, including, potentially, terminal-phase BMD operations.35

Technical Risk and Test and Evaluation Issues

Another potential oversight issue for Congress is technical risk and test and evaluation issues in the Aegis BMD program. Regarding this issue, a December 2019 report from DOD's Director, Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E)—DOT&E's annual report for FY2019—stated the following in its section on the Aegis BMD program:

Assessment

• Results from flight testing, high-fidelity M&S [modeling and simulation], and HWIL [hardware-in-the-loop] testing demonstrate that Aegis BMD can intercept non‑separating, simple-separating, and complex-separating ballistic missiles in the midcourse phase of flight. However, flight testing and M&S did not address all expected threat types, ground ranges, and raid sizes.

• [Flight test] FTM-45 demonstrated that Aegis destroyers can organically engage and intercept MRBMs with SM-3 Block IIA missiles. [Flight test] FTI-03 demonstrated, for the first time in an end-to-end test, Aegis BMD's capability to intercept an IRBM using EOR [engage-on-remote capability] and an SM-3 Block IIA missile.

• OPTEVFOR [the Navy Commander, Operational Test and Evaluation Force] accredited Aegis BMD high-fidelity M&S tools for many scenarios, but it noted limitations for raid engagements due to the lack of validation data from live fire raid engagements and lack of post-intercept debris modeling.

• During the four events that comprised FS-19 [Formidable Shield-19], the MDA demonstrated Aegis BMD interoperability with NATO partners over the U.S. European Command Operational Tactical Data Link communication architecture during cruise missile and ballistic missile engagements. An Aegis destroyer twice engaged a simulated MRBM target with live SM-3 Block IA missiles, performed engagement support surveillance and track, organically engaged a live SRBM target with a simulated SM-6 Block 1 guided missile, and organically engaged a lofted SRBM target with simulated SM-3 Block IB (Threat Update) missiles. During the last engagement, the geo-repositioned AAMDTC [Aegis Ashore Missile Defense Test Complex] launched a simulated SM-3 Block IIA guided missile at the target, using track data from the BL [Baseline] 9.C2 ship in an EOR scenario.

• Aegis BMD has exercised rudimentary engagement coordination with Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense [THAAD] firing units, but not with Patriot. MDA ground tests have routinely shown that inter-element coordination and interoperability need improvement to enhance engagement efficiency.

• The MDA has been collaborating with DOT&E and the USD(R&E) [Under Secretary of Defense, Research and Engineering] to establish an affordable ground testing approach to support assessments of reliability. DOT&E cannot assess SM-3 missile reliability with confidence until the MDA is able to provide additional ground test data that simulates the in-flight environment. In FY19, the MDA identified possible data sources to inform reliability estimates, but the data will not be available until CY21 [calendar year 2021].

• A December 2017 SM-3 Block IB Acquisition Decision Memorandum [ADM] requires the MDA and DOT&E to ensure periodic flight testing of the Block IB throughout the life of the program in the Integrated Master Test Plan. DOT&E and the MDA agreed that periodic testing would occur at approximately 2 year intervals. The MDA conducted two surveillance firings of the SM-3 Block IB missile in FY18, and two Stockpile Surveillance and Reliability program firings of the SM-3 Block IA missile in FY19.

• AN/SPY-6(V)1 [radar, aka Air and Missile Defense Radar, or AMDR] participated in its final Navy-funded BMD developmental test, FTX-34. This tracking exercise was the last of five SPY-6(V)1 BMD tracking exercises at the U.S. Navy's Advanced Radar Development Evaluation Laboratory (ARDEL). ARDEL does not have the most recent Aegis combat system (i.e., BL [baseline] 10), precluding future integration testing with the AN/SPY-6 radar at that facility.

Recommendations

The MDA should:

1. Provide data from high-fidelity ground test venues in the near term to help inform SM-3 Block IB Threat Upgrade and Block IIA missile reliability estimates.

2. Continue to conduct periodic (approximately every 2 years) SM-3 Block IB firings throughout the life of the program to demonstrate missile reliability.

3. Conduct Aegis BMD flight testing with live fire intercepts of raids of two or more ballistic missile targets to aid in the validation of M&S tools for raid engagements.

4. Improve Aegis BMD high-fidelity M&S tools to incorporate post-intercept debris modeling to better assess engagement performance in raid scenarios.

5. Coordinate with the Navy to fund an Aegis BL10 combat system at ARDEL for use in future combat system integration testing with the AN/SPY-6 radar.36

Regarding the SM-6 missile, the December 2019 DOT&E report also stated the following:

Assessment

• As reported in the FY18 DOT&E SM-6 BLK I FOT&E Report, the SM-6 remains effective and suitable with the exception of the classified deficiency identified in the FY13 IOT&E [Initial Operational Test and Evaluation] Report. The SM-6 BLK I satisfactorily demonstrated compatibility with AWS [Aegis Weapon System] Baseline 9 Integrated Fire Control capability.

• The Navy is not planning operational testing or lethality assessments for SM-6 BLK I and BLK IA FCD [Future Capabilities Demonstration]. The FCD represent significant warfighting improvements for Aegis destroyers and cruisers. DOT&E, with the Navy's concurrence, actively participated in the planning and execution of the FY19 and planned future developmental test events, and will report, as appropriate, on these warfighting enhancements.

• Data analysis is underway on the completed SM-6 BLK IA live fire and M&S FOT&E events. DOT&E will report on SM-6 BLK 1A FOT&E [Follow-On Operational Test and Evaluation] in FY20.

Recommendations

The Navy should:

1. Continue to improve software based on results investigating the classified performance deficiency discovered during IOT&E, perform corrective actions, and verify corrective actions with flight tests. This includes correcting the two new problems identified during FY17 SM-6 BLK I Verification of Corrected Deficiency tests.

2. Plan FOT&E testing and lethality assessments for SM-6 BLK I and BLK IA FCD.37

Legislative Activity for FY2021

Summary of Action on FY2021 MDA Funding Request

Table 2 summarizes congressional action on the FY2021 request for MDA procurement and research and development funding for the Aegis BMD program.

Table 2. Summary of Congressional Action on FY2021 MDA Funding Request

(In millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth; totals may not add due to rounding)

|

Request |

Authorization |

Appropriation |

|||||

|

HASC |

SASC |

Conf. |

HAC |

SAC |

Conf. |

||

|

Procurement |

|||||||

|

Aegis BMD (line 34) |

356.2 |

||||||

|

(SM-3 Block IB missile quantity) |

(34) |

||||||

|

Aegis BMD Advance Procurement (line 35) |

44.9 |

||||||

|

SM-3 Block IIA (line 37) |

218.3 |

||||||

|

(SM-3 Block IIA missile quantity) |

(6) |

||||||

|

Aegis Ashore Phase III (line 40) |

39.1 |

||||||

|

Aegis BMD hardware and software (line 42) |

104.2 |

||||||

|

Subtotal Procurement |

762.7 |

||||||

|

Research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) |

|||||||

|

Aegis BMD (PE 0603892C) (line 82) |

814.9 |

||||||

|

Aegis BMD test (PE 0604878C) (line 113) |

170.9 |

||||||

|

Land-based SM-3 (PE 0604880C) (line 115) |

56.6 |

||||||

|

Subtotal RDT&E |

1,042.2 |

||||||

|

TOTAL |

1,805.1 |

||||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on DOD's original FY2021 budget submission, committee and conference reports, and explanatory statements on FY2021 National Defense Authorization Act and FY2021 DOD Appropriations Act.

Notes: HASC is House Armed Services Committee; SASC is Senate Armed Services Committee; HAC is House Appropriations Committee; SAC is Senate Appropriations Committee; Conf. is conference agreement.

Appendix A. Aegis BMD Flight Tests

Table A-1 presents a summary of Aegis BMD flight tests since January 2002. As shown in the table, since January 2002, the Aegis BMD system has achieved 33 successful exo-atmospheric intercepts in 42 attempts using the SM-3 missile (including 4 successful intercepts in 5 attempts by Japanese Aegis ships, and 2 successful intercepts in 3 attempts attempt using the Aegis Ashore system), and 7 successful endo-atmospheric intercepts in 7 attempts using the SM-2 Block IV and SM-6 missiles, making for a combined total of 40 successful intercepts in 49 attempts.

In addition, on February 20, 2008, a BMD-capable Aegis cruiser operating northwest of Hawaii used a modified version of the Aegis BMD system with the SM-3 missile to shoot down an inoperable U.S. surveillance satellite that was in a deteriorating orbit. Including this intercept in the count increases the totals to 34 successful exo-atmospheric intercepts in 43 attempts using the SM-3 missile, and 41 successful exo- and endo-atmospheric intercepts in 50 attempts using SM-3, SM-2 Block IV, and SM-6 missiles.

|

Date |

Country |

Name of flight test of exercise |

Ballistic Missile Target |

Successful? |

Cumulative |

Cumulative |

|

Exo-atmospheric (using SM-3 missile) |

||||||

|

1/25/02 |

US |

FM-2 |

Unitary short-range (TTV) |

Yes |

1 |

1 |

|

6/13/02 |

US |

FM-3 |

Unitary short-range (TTV) |

Yes |

2 |

2 |

|

11/21/02 |

US |

FM-4 |

Unitary short-range (TTV) |

Yes |

3 |

3 |

|

6/18/03 |

US |

FM-5 |

Unitary short-range (TTV) |

No |

3 |

4 |

|

12/11/03 |

US |

FM-6 |

Unitary short-range (TTV) |

Yes |

4 |

5 |

|

2/24/05 |

US |

FTM 04-1 (FM-7) |

Unitary short-range (TTV) |

Yes |

5 |

6 |

|

11/17/05 |

US |

FTM 04-2 (FM-8) |

Separating short-range (MRT) |

Yes |

6 |

7 |

|

6/22/06 |

US |

FTM 10 |

Separating short-range (TTV) |

Yes |

7 |

8 |

|

12/7/06 |

US |

FTM 11 |

Unitary short-range (TTV) |

No |

7 |

9 |

|

4/26/07 |

US |

FTM 11 |

Unitary short-range (ARAV-A) |

Yes |

8 |

10 |

|

6/22/07 |

US |

FTM 12 |

Separating short-range (MRT) |

Yes |

9 |

11 |

|

8/31/07 |

US |

FTM-11a |

Classified |

Yes |

10 |

12 |

|

11/6/07 |

US |

FTM 13 |

Unitary short-range (ARAV-A) |

Yes |

11 |

13 |

|

Unitary short-range (ARAV-A) |

Yes |

12 |

14 |

|||

|

12/17/07 |

Japan |

JFTM-1 |

Separating short-range (MRT) |

Yes |

13 |

15 |

|

11/1/08 |

US |

Pacific Blitz |

Unitary short-range (ARAV-A) |

Yes |

14 |

16 |

|

Unitary short-range (ARAV-A) |

No |

14 |

17 |

|||

|

11/19/08 |

Japan |

JFTM-2 |

Separating short-range (MRT) |

No |

14 |

18 |

|

7/30/09 |

US |

FTM-17 |

Unitary short-range (ARAV-A) |

Yes |

15 |

19 |

|

10/27/09 |

Japan |

JFTM-3 |

Separating short-range (MRT) |

Yes |

16 |

20 |

|

10/28/10 |

Japan |

JFTM-4 |

Separating short-range (MRT) |

Yes |

17 |

21 |

|

4/14/11 |

US |

FTM-15 |

Separating intermediate range (LV-2) |

Yes |

18 |

22 |

|

9/1/11 |

US |

FTM-16 E2 |

Separating short-range (ARAV-B) |

No |

18 |

23 |

|

5/9/12 |

US |

FTM-16 E2a |

Unitary short-range (ARAV-A) |

Yes |

19 |

24 |

|

6/26/12 |

US |

FTM-18 |

Separating short-range (MRT) |

Yes |

20 |

25 |

|

10/25/12 |

US |

FTI-01 |

Separating short-range (ARAV-B) |

No |

20 |

26 |

|

2/12/13 |

US |

FTM-20 |

Separating medium-range (MRBM-T3) |

Yes |

21 |

27 |

|

5/15/13 |

US |

FTM-19 |

Separating short-range (ARAV-C) |

Yes |

22 |

28 |

|

9/10/13 |

US |

FTO-01 |

Separating medium-range (eMRBM-T1) |

Yes |

23 |

29 |

|

9/18/13 |

US |

FTM-21 |

Separating short-range (ARAV-C++) |

Yes |

24 |

30 |

|

10/3/13 |

US |

FTM-22 |

Separating medium-range (ARAV-TTO-E) |

Yes |

25 |

31 |

|

11/6/14 |

US |

FTM-25 |

Separating short-range (ARAV-B) |

Yes |

26 |

32 |

|

6/25/15 |

US |

FTO-02 E1 |

Separating medium-range (IRBM T1) |

n/aa |

26 |

32 |

|

10/4/15 |

US |

FTO-02 E2 |

Separating medium-range (eMRBM) |

n/ab |

26 |

32 |

|

10/20/15 |

US |

ASD-15 E2 |

Separating short-range (Terrier Orion) |

Yes |

27 |

33 |

|

11/1/15 |

US |

FTO-02 E2a |

Separating medium-range (eMRBM) |

No |

27 |

34 |

|

12/10/15 |

US (Aegis Ashore) |

FTO02 E1a |

Separating medium-range (IRBM T1) |

Yes |

28 |

35 |

|

2/3/17 |

US-Japan |

SFTM-01 |

Separating medium-range (MRT) |

Yes |

29 |

36 |

|

6/21/17 |

US-Japan |

SFTM-02 |

Medium-range |

No |

29 |

37 |

|

10/15/17 |

US |

FS17 |

Medium-range target |

Yes |

30 |

38 |

|

1/31/18 |

US (Aegis Ashore) |

FTM-29 |

Intermediate-range target |

No |

30 |

39 |

|

9/11/18 |

Japan |

JFTM-05 |

Simple separating target |

Yes |

31 |

40 |

|

10/26/18 |

US |

FTM-45 |

Medium range |

Yes |

32 |

41 |

|

12/10/18 |

US (Aegis Ashore) |

FTI-03 |

Intermediate-range target |

Yes |

33 |

42 |

|

Endo-atmospheric (using SM-2 missile Block IV missile and [for MMW Event 1] SM-6 Dual 1 missile) |

||||||

|

5/24/06 |

US |

Pacific Phoenix |

Unitary short-range target (Lance) |

Yes |

1 |

1 |

|

6/5/08 |

US |

FTM-14 |

Unitary short-range target (FMA) |

Yes |

2 |

2 |

|

3/26/09 |

US |

Stellar Daggers |

Unitary short-range target (Lance) |

Yes |

3 |

3 |

|

7/28/15 |

US |

MMW E1 |

Unitary short-range target (Lance) |

Yes |

4 |

4 |

|

7/29/15 |

US |

MMW E2 |

Unitary short-range target (Lance) |

Yes |

5 |

5 |

|

12/14/16 |

US |

FTM-27 |

Unitary short-range target (Lance) |

Yes |

6 |

6 |

|

8/29/17 |

US |

FTM-27 E2 |

Medium-range target (MRBM) |

Yes |

7 |

7 |

|

Combined total for exo- and endo-atmospheric above tests |

40 |

49 |

||||

Sources: Table presented in MDA fact sheet, "Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense Testing," February 2017, accessed on October 16, 2017, at https://www.mda.mil/global/documents/pdf/aegis_tests.pdf, and (for flight tests subsequent to February 2017) MDA news releases.

Notes: TTV is target test vehicle; ARAV is Aegis Readiness Assessment Vehicle. In addition to the flight tests shown above, there was a successful use of an SM-3 on February 20, 2008, to intercept an inoperative U.S. satellite—an operation called Burnt Frost. Including this intercept in the count increases the totals to 31 successful exo-atmospheric intercepts in 40 attempts using the SM-3 missile, and 38 successful exo- and endo-atmospheric intercepts in 47 attempts using SM-3, SM-2 Block IV, and SM-6 missiles.

a. MDA's table shows this as a test that did not result in the launch of an SM-3. MDA as of August 3, 2015, had not issued a news release discussing this event. MDA's count of 31 successful intercepts in 37 launches through July 29, 2015, does not appear to include this test, suggesting that this was considered a "no test" event—a test in which there was a failure that was not related to the Aegis BMD system or the SM-3 interceptor. News reports state that the test was aborted due to a failure of the target missile. (Andrea Shalal, "U.S. Skips Aegis Ashore Missile Test After Target Malfunction," Reuters, June 26, 2015.) MDA's table similarly shows the test of December 7, 2006, as a test that did not result in the launch of an SM-3. MDA issued a news release on this test, which stated that an SM-3 was not launched "due to an incorrect system setting aboard the Aegis-class cruiser USS Lake Erie prior to the launch of two interceptor missiles from the ship. The incorrect configuration prevented the fire control system aboard the ship from launching the first of the two [SM-3] interceptor missiles. Since a primary test objective was a near-simultaneous launch of two missiles against two different targets, the second interceptor missile was intentionally not launched." MDA counts the test of December 7, 2006, as an unsuccessful intercept in its count of 31 successful intercepts in 37 launches through July 29, 2015.

b. MDA's table shows this as a test that did not result in the launch of an SM-3. MDA as of November 10, 2015, had not issued a news release discussing this event. MDA's count of 32 successful intercepts in 39 launches through November 1, 2015, does not appear to include this test, suggesting that this was considered a "no test" event—a test in which there was a failure that was not related to the Aegis BMD system or the SM-3 interceptor.