Introduction

Child care quality, accessibility, and cost are frequent concerns for military families. This report traces the development of DOD-sponsored child care services and discusses these issues in greater depth in order to support Members of Congress in their oversight role. The next section gives an overview of DOD's justification for the CDP and demand for services. Next is a discussion of current CDP components, policies, and funding. This is followed by the legislative history of DOD-sponsored child care in the military including a discussion of recent initiatives. The final section puts forth some issues and options for Congress related to oversight and funding of military child care programs. Other military family or youth recreation and enrichment programs are beyond the scope of this report.

Why Does DOD Provide Child care Services?

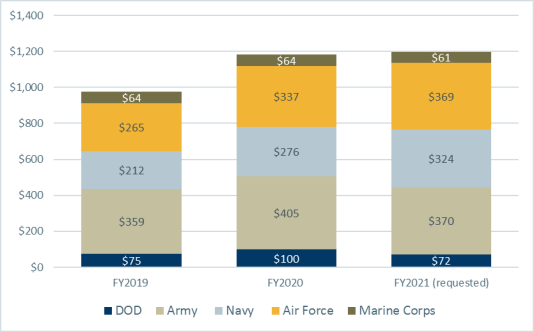

For most of the history of the U.S. military, young, single males were favored for recruitment and induction into the military by various laws and policy.1 Following the end of the draft and the beginning of the all-volunteer force (AVF) in 1973, DOD was required to compete for manpower with civilian employers. As DOD continually expanded its recruiting efforts, the proportion of women in the active component of the military grew from about 2.5% in 1973 to 16% in 2019.2 Today there are almost twice as many dual-military married couples and single parents serving on active duty than in 1985 (see Figure 1). In addition, there are approximately one million military dependent children of active duty members.3 Thus, DOD has expanded family-oriented benefits and programs as a component of its total servicemember compensation package. DOD's child development program (CDP) is one of these family-oriented initiatives and is part of a broader set of community and family support programs.4

|

Figure 1. Change in Dual-Military Couples and Single Parents Active Duty, 1985 and 2018 |

|

|

SourceS: 1985 data is a DOD estimate reported by the General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office) in Observations on the Military Child Care Program: Statement of Linda G. Morra before the Subcommittee on Military Personnel and Compensation, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, T-HRD-88-28, August 2, 1988. Department of Defense, 2018 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community, 2018. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2018-demographics-report.pdf. Notes: Dual military married couples are those where both members serve on active duty in one of the services. Not all dual military couples have children. |

DOD considers child care services a quality of life benefit and DOD officials have indicated that the primary reason for providing child care services is to enhance force readiness.5 DOD's stated policy is to ensure that child care services

[s]upport the mission readiness, retention, and morale of the total force during peacetime, overseas contingency operations, periods of force structure change, relocation of military units, base realignment and closure, and other emergency situations.6

Some in DOD and in military family advocacy groups have tied child care benefits to improved recruitment, morale, and retention of military personnel. Surveys of military servicemembers and veterans have consistently found that affordable and reliable child care is a top quality-of-life concern. In particular, a larger percentage of female servicemembers and veterans have cited child care issues as a major stressor associated with their time in service, relative to their male counterparts.7 In addition, surveys of military spouses have found that challenges in finding adequate child care are a disincentive to seek employment.8

DOD competes for talent with civilian employers who have begun to offer more family-friendly policies and benefits over the past few decades. This means that the compensation and benefits packages offered to servicemembers may need to be as good as or better than available civilian compensation packages to recruit and retain talent.

Research on the links between employer-sponsored child care and employee performance, morale, job satisfaction, and recruitment and retention have had mixed results. In general, some studies suggest positive links between these benefits, employee satisfaction, and organizational commitment.9 In particular, child care benefits are found to be more important to those employees who lack support from immediate or extended family. A 2011 study of family-friendly benefits at federal agencies found positive relationships between child care subsidy programs, agency performance, and reduced employee turnover.10 DOD credits the availability of quality child care on or near installations with reducing lost duty time (e.g., absenteeism and tardiness) and fewer parental distractions that could reduce servicemembers' productivity. For example, in 1987, the Army reported survey data showing that 20% of enlisted and 22% of officers had lost job and duty time due to lack of adequate child care.11 However, other research has found little empirical evidence that employer-sponsored child care in the private or public sector has significant positive effects on individual performance, productivity, or job satisfaction.12

Research on military families has shown that the readiness impact of insufficient child care varies by family type, with single parents and dual military couples reporting more missed duty time after the birth of a new child or when moving to a new installation.13 There is also some evidence that child care challenges may impact retention decisions. Military families have reported that it is "likely or very likely" that child care issues would lead them to leave the military and those with pre-school-age children have reported that they are more likely to leave the military than their counterparts with school-age children.14

On the other hand, some human resource professionals have warned that perceived inequities in the provision of child care benefits may have negative effects on the morale of childless employees or parents who are unable to use the benefit (e.g., those who are wait-listed for child care spots and/or lower on the priority list).15 Nevertheless, while researchers have found some evidence of negative employee attitudes towards specific family-friendly benefits, they have not found that these attitudes translated into negative perceptions or behaviors towards the organization.16

Demand for Military Child care

Military families may have different child care needs than their civilian counterparts. Servicemembers typically make a number of permanent change-of-station (PCS) moves throughout a career, making it difficult to maintain consistent full-time child care arrangements or draw on support from extended family members and friends. In addition, servicemembers may be required to work extended hours or shift work during times when normal day care providers are not in operation—a problem that may be exacerbated for single-parent servicemembers or dual-military spouses. Even in cases of married couples where the spouse is a civilian, deployments (typically six months or more) can create child care challenges for both working and nonworking spouses of military servicemembers who essentially become single parents for the duration of the deployment.17

DOD tracks Demand Accommodation Rate as a metric for whether it is meeting the child care needs of military families. DOD has previously reported that it was accommodating 78% of demand for CDC services.18 Wait list data is one way to measure this demand, which is affected by demographic, geographic, and structural factors. The services manage wait lists for CDCs locally and slots are allocated based on the date that the request for care was filed, priority criteria, and other mission-related factors at the installation commander's discretion (see Table A-1).19 The Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission (MCRMC) found that in 2014 there were 10,979 total children on waiting lists for child care, with a disproportionate number of children (73%) age three and under on waiting lists.20 In 2019, the Navy reported 9,000 families on waiting lists, mainly concentrated in fleet areas (e.g., Norfolk, VA and San Diego, CA).21 The Army reported approximately 5,000 children on its wait lists – primarily infants and toddlers. Reported wait lists for the Air Force and Marine Corps were 3,200 and 800 children, respectively.22

Although waiting list numbers are one indicator of demand, they may not accurately represent the total number of additional child care slots that are needed. Families that want military child care services may decide the waiting list is too long and may seek child care through other sources. Waiting list numbers might also lead to overestimates of demand, if families remain on waiting lists after a PCS move or after they no longer need military child care. Demand can also fluctuate based on parental preferences for care, the availability of other community-based child care options, unit deployment schedules, and changes to mission requirements.

Eligible Population

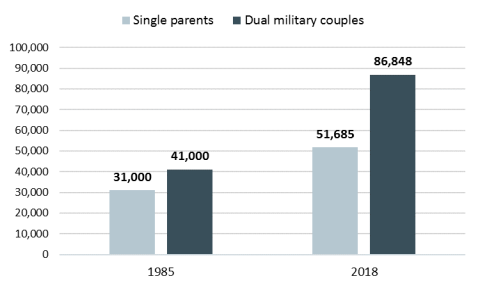

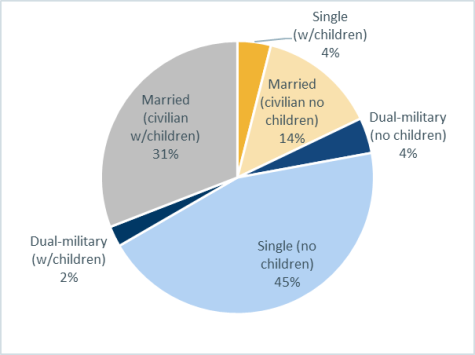

In 2019, 63% of married-couple families in the U.S. with children under 18 had both parents employed outside the home.23 Military servicemembers are, on average, younger than the civilian population and have fewer children. Although civilian spouses of active duty military members are, on average, more educated than other working-age civilians, they are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed and have lower earnings than their civilian counterparts.24 In 2018, 37% of military servicemembers across the active duty force had dependent children; 2% are in dual-military marriages, 4% are single parents, and 31% are in marriages with a civilian spouse (see Figure 2). The total military child population (active and reserve components) under the age of 13 is approximately 1.2 million, with 34% aged 3 and under (see Figure 3).25

|

Figure 2. Active Duty Military Family Status 2018 |

|

|

Source: Department of Defense, 2018 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community, 2018, p. 131, https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2018-demographics-report.pdf. |

|

Figure 3. Number of Children in Active Duty Families Under 12 Years Old October 2019 |

|

|

Source: Defense Manpower Data Center; Active Duty Family Number of Children Report. |

Child care Program Structure, Services, and Funding

DOD offers child care development programs on and off military installations for children from birth through 12 years, including care on full-day, part-day, short-term, and intermittent bases.26 The Military and Community Family Policy Office in DOD's Office of the Under Secretary for Personnel and Readiness oversees child and youth programs.27 DOD's policy states that child care "is not an entitlement." Servicemembers are not guaranteed child care support from DOD and they are required to have adequate care plans in place for their dependents.28 The following are among the child care services available as part of DOD's child development programs.

- Child Development Centers (CDCs). DOD-operated, facility-based care primarily for children from six weeks to five years.

- Family Child Care (FCC).29 Certified home-based child care services (maximum six children per home at any time) for children from 4 weeks through 12 years.30

- School-age Care (SAC). Facility-based or home-based care for children ages 6-12, or those attending kindergarten, who require supervision before and after school, or during duty hours, school holidays, or school closures.

- Supplemental Child Care. Child care programs and services that augment and support CDC and FCC programs to increase the availability of child care for military and DOD civilian employees. These may include, but are not limited to, resource and referral services, fee assistance/subsidy programs, contract-provided services, short-term/respite care, hourly child care at alternative locations, and interagency initiatives.31

For FY2019 the services reported 629 CDCs of varying sizes and 970 certified FCC homes serving approximately 200,000 military-connected children ages 0-12.32

CDC Eligibility and Access

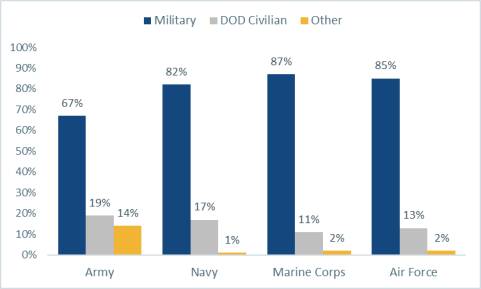

Military service members, surviving spouses, and DOD civilians are generally eligible for CDC services. DOD contractors, military retirees, and other federal agency personnel are eligible on a space-available basis. Over 80% of the CDC slots for the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps are filled by children of servicemembers (see Figure 4). The Army has a higher percentage of slots filled by civilians.33

|

Figure 4. Child Care Slot Allocation by Sponsor Affiliation 2019 |

|

|

Source: Briefings presented to the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS), June 2019, https://dacowits.defense.gov/Portals/48/Documents/General%20Documents/RFI%20Docs/June2019/USN%20RFI%205.pdf?ver=2019-06-09-200036-740. Note: Other includes other federal (non-DOD) civilian employees and direct care staff. |

Eligibility for CDC benefits does not guarantee access to care. DOD determines the priority categories for care. Currently, priority depends on the employment status of the child's sponsor and the sponsor's spouse or same-sex domestic partner on the date of the application for services.34 Military rank, paygrade, occupational specialty, General Schedule (GS) rating, or financial need are not official criteria for determining priority. See Table A-1 for a list of DOD's priority categories and eligibility.

Funding

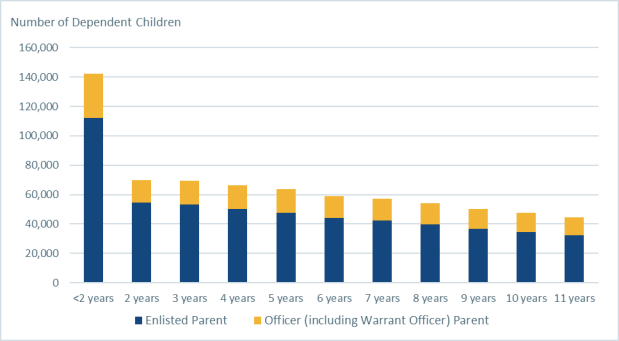

Among DOD's quality of life programs, the CDP is one of the largest appropriated-fund programs. Congress appropriates funds for DOD's Child Development Program through different accounts. Funds for the construction of care facilities come from military construction (MILCON) funds, while other operational funds come from Operation and Maintenance (O&M) and Morale, Welfare, and Recreation (MWR) accounts. Across the Services, approximately $1.2 billion in FY2020 appropriated O&M funds went towards direct support of military child care programs (see Figure 5).

MILCON funding for the construction or modification of CDC facilities varies from year to year depending on need. FCCs that are operated in military family housing are essentially subsidized by appropriated funds to the extent that funding goes towards construction and maintenance of such housing. However, the number of FCCs typically varies from year to year and therefore CRS cannot determine the percentage of military housing funds that support child care services.

Appropriated Funds and Non-Appropriated Funds

CDCs are funded by a combination of appropriated and non-appropriated funds (APF and NAF).35 Statute also allows appropriated funds to be used to subsidize FCCs at costs comparable to those at the CDCs, with the service fees paid directly to the FCC provider.36 By statute the amount of APF used to operate CDC cannot be less than the estimated amount of child care fee receipts.37 According to data provided by the services, NAF typically account for between 30% and 45% of total funding for Child Development Programs.38 Appropriated funds are used to pay for operation and maintenance of child care centers while NAF are used to pay mainly for staff salaries.

Non-appropriated funds for the CDCs come from the parent fees discussed below and are sometimes subsidized by other fee-generating MWR activities (e.g., military exchange store revenues). An installation commander typically has the discretion to direct additional MWR-generated revenues towards child care services or other installation activities and services. Using these funds could help augment the quality of child care services or provide additional resources to the centers' resources. However, over-reliance on MWR subsidies to support child care operations could be problematic, since those revenue streams are less reliable and are more subject to economic downturns. Also, some childless servicemembers may raise equity concerns about MWR revenue spending on family-related benefits rather than on other MWR activities that serve a broader population (e.g., clubs, movie theaters, golf courses). Finally, due to the decentralized nature of MWR funds collection and distribution, there is less visibility of how funds are spent and whether spending is effective in achieving program goals.39

Military child care programs generate approximately $400 million in non-appropriated funds annually through parent-usage fees.40 Statute requires the Secretary of Defense to establish CDC fees; these are adjusted annually to reflect cost of living increases.41 Statute also authorizes the Secretary of Defense to use appropriated funds to subsidize family home day care providers at rates comparable to those at the CDCs.42 DOD's guidance specifies that "child care is not an entitlement" and that each family is required to pay their share of the cost of child care. The amount that each family pays is determined by a sliding scale based on total family income.43 In the lowest income category, at 2019-2020 rates (including market adjustments), a family might pay as little as $51 per week per child and in the highest category would pay a maximum of $210 per week per child (See Table 1). The services have some discretion to offer fee reductions (e.g., for families with multiple children, injured or deployed servicemembers, or those experiencing financial hardship).44

|

Category |

Total Family Income |

Weekly fee per child (standard) |

Optional market adjustment (low) |

Optional market adjustment (high) |

|

I |

$0-$32,525 |

$60 |

$51 |

$70 |

|

II |

$32,526-$39,491 |

$75 |

$66 |

$85 |

|

III |

$39,492-$51,108 |

$93 |

$84 |

$103 |

|

IV |

$51,109-$63,884 |

$108 |

$99 |

$118 |

|

V |

$63,885 - $81,310 |

$124 |

$113 |

$134 |

|

VI |

$81,311 - $94,032 |

$136 |

$124 |

$146 |

|

VII |

$94,033 - $110,625 |

$140 |

$128 |

$150 |

|

VIII |

$110,626 - $138,330 |

$145 |

$133 |

$155 |

|

IX |

$138,331+ |

$150 |

$138 |

$160 |

|

DOD contractors and space-available patrons |

Not Applicable |

$210 |

||

|

Standard Hourly Care Rate |

$5.00 |

|||

Sources: Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs, Department of Defense Child Development Program Fees for School Year 2019-2020, Memorandum for Service Assistant Secretaries for Manpower Reserve Affairs and Director, Defense Logistics Agency, August 27, 2019. CDC monthly fee charts, provided to CRS by the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Notes: Optional market adjustment fees give centers the option to set rates slightly above or below the DOD established rates. Rates are for full-time care; where part-time care is offered, rates may vary. These fees are for implementation by January 1, 2020. Families who do not show proof of income are charged the Category IX fee.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has established a benchmark for affordable child care at 7% of family income for low-income families.45 To put the military child care fees in context, regular military compensation (including pay, allowances and tax advantage) for an E-5 with one dependent child is $68,093 annually, using the calendar 2019 enlisted pay scale.46 This pay rate would place the E-5 (with no spousal or other source of income) in income category V. Therefore, an E-5 would be paying approximately 9.4% of his or her income for child care fees for one child under the standard fee structure. A similarly situated officer, O-3, would have average pay and allowances of $106,825 annually and would be eligible for income category VII.47 This servicemember (with no spousal or other source of income) would be paying approximately 6.8% of his or her income in child care fees for one child.

Military child care fees are generally lower than fees for civilian center-based care. The U.S. Census Bureau has reported that out-of-pocket child care costs have risen over the past three decades, nearly doubling between 1985 and 2011.48 The cost of civilian child care varies widely depending on the age of the child, quality of care, and the geographic location. A 2019 study of child care costs across the nation found that the average annual care cost for center-based child care for one infant in a high-cost state like California is $16,452, and $9,100 for a lower-cost state like South Carolina.49 In comparison, annual military CDC care in 2019 ranged from about $3,000 to $8,400 per child.50 In addition, while civilian centers typically charge higher fees for infant care, DOD centers do not have variable fees for infants. DOD care is also unique due to the progressive nature of the subsidy, with lower income families paying less in fees. Civilian centers generally offer a flat fee for care, rather than a sliding scale based on income. However, low-income families may be eligible for supplemental state or federal child care assistance.51

Quality Assurance and Oversight

Child care decisions can be complex and military parents or guardians often have to make care choices under time constraints while transferring to a new duty station. They may have limited information about provider options and quality of care at the new locale. DOD's regulations for military child care centers generally have stricter operational, safety, and performance standards than many civilian centers and these standards have been ranked highest among all states in national assessments.52 DOD uses accreditation and certification rates as its primary metric for monitoring child care program quality.53 Because attaining accreditation and maintaining quality standards can be expensive, high-quality civilian child care centers may be out of reach for some military servicemembers, particularly for junior enlisted members. In the absence of DOD-subsidized options, these military families might otherwise rely on an informal or unregulated systems of child care.

Accreditation

Accreditation is one mechanism used to achieve quality assurance for child care. National child care accreditation organizations evaluate providers on standards related to, for example, curriculum, teaching, health, staff competencies, leadership and management, physical environment, and relationships between teachers, children, parents, and communities.54 Costs for initial accreditation and maintenance of accreditation typically vary by the number of children and accreditation is often awarded for a five-year term.55 The accreditation can serve two key purposes. First, the process of becoming accredited and accreditation renewal requires an organization to self-assess and can be a mechanism for improved operations and staff development. Second, accreditation can serve as a signaling mechanism to parents who typically do not have the information to individually assess the level of child care center quality. Critics of accreditation have argued that the requirements impose unnecessary time and resource burdens on child care staff. However, others have noted that accreditation can improve staff's morale and pride in their work.56

Congress first required accreditation of CDCs as a demonstration program in 1991. By 1994, a report on the impact of accreditation found that it improved care in both low-quality and high-quality centers at minimal incremental cost.57 The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1996 required all eligible military centers meet standards necessary for accreditation.58 By 1998, all of the military departments had implemented universal accreditation for their CDCs.59 As of 2015, DOD reported that 97% of its CDCs were nationally accredited, just shy of its goal of 98% accreditation. In comparison, the civilian rate of center accreditation nation-wide is estimated to be about 9% and varies by state.60 DOD FCCs are not required by law to be accredited; however, DOD policy encourages providers to seek national accreditation. To be eligible for the Fee Assistance program, private child care programs are not required by law to be accredited; however, they are required to be licensed to provide those services under applicable state and local law and are subject to DOD and service-level regulations.61

Certification

CDC and SAC facilities are required to meet certain minimum operational standards to receive a DOD Certificate to Operate.62 These include DOD's Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC) as well as Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards.63 By law, CDCs are subject to unannounced inspections a minimum of four times per year.64 One of these inspections must be carried out by an installation representative and one must be carried out by a representative of the major command under which the facility operates. The law also states

(1) Except as provided in paragraph (2), any violation of a safety, health, or child welfare law or regulation (discovered at an inspection or otherwise) at a military child development center shall be remedied immediately.

(2) In the case of a violation that is not life threatening, the commander of the major command under which the installation concerned operates may waive the requirement that the violation be remedied immediately for a period of up to 90 days beginning on the date of the discovery of the violation. If the violation is not remedied as of the end of that 90-day period, the military child development center shall be closed until the violation is remedied. The Secretary of the military department concerned may waive the preceding sentence and authorize the center to remain open in a case in which the violation cannot reasonably be remedied within that 90-day period or in which major facility reconstruction is required.65

FCC homes must meet the same standards as CDCs and are subject to inspections by FCC staff, as well as requirements to meet Fire, Safety, USDA Food Program, and Public Health Program requirements. DOD reported that it met its 100% certification rate goal for FY2015.66

Staff Qualifications and Background Checks

Child care employees are required by statute to meet certain training requirements that include at least the following.

- Early childhood development.

- Activities and disciplinary techniques appropriate to children of different ages.

- Child abuse prevention and detection.

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and other emergency medical procedures.67

At least one employee at each CDC is required to be a specialist in training and curriculum development.

To ensure the ability to recruit "a qualified and stable civilian workforce," the law requires that CDC employees be paid at rates of pay that are competitive or substantially equivalent to rates of pay for other employees at the respective installation.68 Besides competitive salaries, CDC employees are eligible to receive other federal employee benefits (e.g., medical, dental, and retirement benefits), as well as access to some of the amenities on military installations (e.g., fitness centers and recreation activities). FCC providers receive training, resources, and support through the CDC program but operate as independent providers.69

DOD regulations require that background checks be conducted on all individuals who regularly interact with children and youth.70 This includes CDC employees and FCC operators. In FCC homes all residents over the age of 12 are subject to background checks. Following a highly publicized incident at a CDC in Fort Myer, VA in 2012 where two daycare workers were charged with assault, DOD took action to review and strengthen background check procedures.71 DOD's new policy, effective in 2015, requires DOD components to ensure that background checks have been completed and to address delays in results in a manner that does not presume a favorable background check.72

Parent Boards

Another statutory element of oversight is the requirement that each CDC establish a board of parents of the children attending the center.73 The board is charged with meeting periodically with the staff and coordinating parent participation programs.

Legislative and Policy Background

The federal government first took a significant role in child care during the Great Depression when it set up day care centers to provide jobs for women through the Works Progress Administration.74 In 1941, in response to the need for women to work outside the home while many young men were away at war, the government passed the Lanham Act of 1940.75 The act provided grant funding nation-wide to communities based on demonstrated need, for care for children ages 0-12. These federal funds were used for the construction of child care facilities, teacher training and pay, and meal services.76 Over 550,000 children nation-wide are estimated to have received care from Lanham Act programs.77 By 1946, the funds were withdrawn with the government's expectation that most women would return to child care duties within the home following the end of the war.

In the U.S. military, demand for child care was low throughout much of the early 20th century. This was due to the demographic composition of the force and prevailing social norms. In the 1950s approximately 70% of servicemembers in the Army were single males, who generally did not have children or child care duties.78 Today over 50% of the total active duty force is married and females account for approximately 16% of the force. In the 1950s and 1960s, nonworking spouses mainly provided care for children of military servicemembers at home. During this era, if child care was needed outside the home, relatives, private groups, parents' cooperatives, or wives' clubs provided it. Some of these wives' clubs also sponsored part-day preschools that provided education and development programs for toddlers aged 3-5 years old.79 This child care system was loosely structured and had few regulations.

Between 1970 and 1980 a number of developments increased demand for military child care services. With the advent of the all-volunteer force in 1973, new recruits increasingly included women and career-oriented personnel with dependents. Between 1973 and 1978 the proportion of women in the military climbed from 2.5% to over 6% and the number of dual military marriages increased. In 1975, DOD directed the services to discontinue involuntary discharges for pregnant or custodial mothers, in favor of a voluntary separation policy.80 Meanwhile, between 1970 and 1980 the proportion of women participating in the U.S. labor force jumped from 43% to 51%81, and civilian employer-sponsored child care initiatives began to gain popularity.82 An increase in civilian spouses of military members working outside the home meant both an increased demand for child care services and fewer participants in the informal caregiver support networks that had been providing these services.

Around the same time the quality of child care services on DOD installations came under scrutiny. In 1976, a nation-wide survey of military centers operating as non-appropriated fund programs, found that there was a wide variance in the services and standards of military facilities relative to civilian facilities.83 The study also noted a lack of specialized training for teachers and aides. In 1978, DOD issued a directive formalizing government responsibility for installation child care centers as part of the military's morale, welfare, and recreation (MWR) program.84 This directive held the individual services responsible for developing their own policies and standards and allowed installations to establish their own operating procedures.

Congress first appropriated funds for the construction of new child care facilities in the Department of Defense Appropriation Act for Fiscal Year 1982.85 At that time the military services reported serving approximately 53,000 children in 576 facilities. In 1982, GAO reported that the majority of these existing child care facilities needed enhancements to meet fire, safety, and sanitation standards and to accommodate demand for services.86 Some of the deficiencies noted in the centers were lack of emergency evacuation access, lead-based paint peeling from the walls, and leaking roofs. The GAO also noted that user fees and other existing revenue streams might not be sufficient for the military services to conduct necessary upgrades. Finally, the report recommended that DOD establish department-wide minimum standards for total group size, caregiver-to-child ratios, educational activities, staff training, and food services.

Military Family Act of 1985

In 1985 Congress passed the Military Family Act establishing an Office of Family Policy within the Office of the Secretary of Defense.87 The office was designed to coordinate all DOD programs and activities relating to military families. The specified duties of the office were to

- coordinate programs and activities of the military departments to the extent that they relate to military families; and

- make recommendations to the Secretaries of the military departments with respect to programs and policies regarding military families.88

The act also established the authority of the Secretary of Defense to survey military family members on the effectiveness of existing federal military family support programs. In 1988, the Office of Family Policy was instrumental in formulating the Defense Department's Instruction for Family Policy. The Instruction laid the groundwork for implementing the current military child care programs.

Military Child Care Act of 1989

In the late 1980s, military child care services came under intense scrutiny after allegations of child abuse at a number of military installations emerged. Widespread publicity of allegations, particularly those involving Army CDCs at the United States Military Academy in West Point New York, and the Presidio Army Base in San Francisco, California, led DOD to establish a special investigative team in 1987.89 Many felt that the military was not doing enough to address the allegations, and a congressional inquiry was launched in 1988 with a series of hearings and testimony by military officials, child care specialists, legal experts, and military parents.

In the hearings, issues were raised about the staff-to-child ratios, the lack of employee background investigations, and inadequate procedures for deterring, preventing, identifying and responding to child abuse.90 Some of the other issues that were raised were the exemption of on-base child care centers from federal and state licensing standards and other jurisdictional issues, lack of quality programming within the centers, and low wages for child care employees. Some suggested that the reliance on non-appropriated funds limited the centers' ability to attract and retain quality personnel and to make necessary repairs and upgrades to facilities and equipment. Other concerns were the lack of capacity to meet demand and unsuitable civilian alternatives at certain military installations.91

In 1989, Congress passed the Military Child Care Act (MCCA) as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for 1990 and 1991.92 The goals of the MCCA were to improve the quality, safety, availability, and affordability of military child care. To achieve these goals the law called for standardizing requirements for health and safety inspections and training requirements. It also included provisions for increasing salaries of caregivers, parental participation, and DOD oversight, in particular, unannounced inspections.93 To improve affordability, Congress authorized the use of appropriated funds to subsidize family home day care providers and required a subsidized CDC fee structure that was based on family income.

To improve employee quality, the law required that at least one employee at each CDC be credentialed as a specialist in training and curriculum development and that all employees undergo mandatory training on four topics within six months of employment: (1) early childhood development, (2) activities and disciplinary techniques appropriate to children of different ages, (3) child abuse prevention and detection, and (4) cardiopulmonary resuscitation and other emergency medical procedures. Another quality initiative in the MCCA was a provision requiring accreditation of at least 50 military child care development centers (CDCs) by June 1, 1991, as a demonstration program. These 50 centers were intended to then serve as "model" centers for other CDCs and FCCs.94

In response to concerns about child abuse, the act required the establishment of a national hotline to report suspected child abuse or safety violations. It also directed DOD to establish regulations compelling installation commanders to coordinate with local child protective authorities in cases of child abuse allegations. The act also required DOD to establish a child abuse task force to respond to abuse allegations and to assist parents and installation commanders in dealing with allegations. Section 658 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1996 amended and codified the Military Family Act and MCCA under Chapter 88 of Title 10, United States Code, "Military Family Programs and Military Child Care."95

1999: Authorization of Child care Fee Assistance Program

As part of the FY2000 NDAA, Congress, for the first time, authorized DOD to subsidize civilian child care programs outside of military installations.96 To receive subsidies, these programs are required to comply with DOD regulations, standards and policies. Provider eligibility determinations are based on factors such as frequency of inspections, employee qualifications, and center accreditation.97 The Senate Committee report to accompany the bill noted,

The committee believes that the recommended financial assistance is necessary to supplement and expand essential quality of life services for children of military personnel and eligible federal employees at an affordable cost.98

The statute authorizes DOD to use Operation and Maintenance (O&M) funds for financial assistance under this program.99 The program provides a subsidy in the amount of the difference between what an eligible servicemember would pay for installation-based care (in CDCs) and the community-based care provider's rate up to a certain cap. Fee assistance subsidy services are administered by Child care Aware of America, a national nonprofit organization.100

|

Providers Eligible to Receive Fee Assistance Under 10 U.S.C. §1798, providers of child care or youth programs are eligible for financial assistance from DOD if the provider "(1) is licensed to provide those services under applicable State and local law; |

In the FY2020 NDAA, Congress asked DOD for an assessment of the fee assistance program, in particular to ascertain whether the maximum allowable subsidy provides adequate support to families at high-cost duty stations.101

2005: Tenth Quadrennial Review of Military Compensation (QRMC)

Section 1008(b) of Title 37, United States Code requires the President to conduct a review of the military compensation system every four years. The 10th QMRC, which was released in September 2008 had a specific mandate to address military quality of life programs.102 The authors of the report raised concerns that DOD was not managing the child care program as an element of a comprehensive compensation package. They noted that services were only available to a fraction of the force, wait list policies did not give priority based on highest need, and centers had limited hours. The authors questioned whether the investment in child care (estimated to be $530 million at the time) had any impact on DOD's force management goals, noting that servicemembers "significantly underestimate the program's value," and it was unclear whether the program had a "significant or cost-effective impact on … recruitment, retention, or readiness."103 Given these concerns the QRMC made three recommendations intended to improve equity, efficiency, and access to the child care benefit.

(1) The Services should prioritize allocation of child care slots based on force management needs, with priority to families of deployed soldiers in wartime and to servicemembers in critical/high demand occupations in peacetime.

(2) DOD should implement a pilot voucher program to help servicemembers pay for child care costs.

(3) DOD should increase its investment in family child care.104

In particular, the authors argued that a cash voucher system would offer a more tangible benefit for military families.105 DOD policies currently specify priority levels; however, DOD has not adopted the recommendation that priority be given to deployed soldiers or critical/high demand occupation.

2011: Congressional and Executive Oversight Initiatives

Congress included a provision in the FY2011 NDAA requiring DOD to submit biennial reports to the Armed Services Committees with information on CDCs and financial assistance for child care (see box below for required elements).106

|

Elements Required in Biennial Congressional Reports (1) The number of child development centers currently located on military installations. (2) The number of dependents of members of the Armed Forces utilizing such child development centers. (3) The number of dependents of members of the Armed Forces that are unable to utilize such child development centers due to capacity limitations. (4) The types of financial assistance available for child care provided by DOD in an off-installation setting to members of the Armed Forces (including eligible members of the reserve components). (5) The extent to which members of the Armed Forces are utilizing such financial assistance for child care off-installation. (6) The methods by which the Department of Defense reaches out to eligible military families to increase awareness of the availability of such financial assistance. (7) The formulas used to calculate the amount of such financial assistance provided to members of the Armed Forces. (8) The funding available for such financial assistance in DOD and in the military departments. (9) The barriers to access, if any, to such financial assistance faced by members of the Armed Forces, including whether standards and criteria of the DOD for child care off-installation may affect access to child care. (10) Any other matters the Secretary considers appropriate in connection with such report, including with respect to the enhancement of access to Department of Defense child care development centers and financial assistance for child care off-installation for members of the Armed Forces.107 |

In January 2011, then-President Barack Obama launched an initiative to support military families.108 Two of the four strategic priorities under this initiative are related to child care and child development:

- Ensure excellence in military children's education and their development.

- Increase child care availability and quality for the Armed Forces.

To help meet the needs identified in this report, the Obama Administration established the Military Family Federal Interagency Collaboration between DOD and the Department of Health and Human Services. This effort focused on

increasing the availability and quality of child care in 20 states for military families, especially those not living near military bases or lacking easy access to other military supports. The Collaboration has identified and is working toward the strategic goals of improving: (1) access to quality child care by increasing the level of quality; (2) the awareness of quality indicators and their importance for creating and maintaining safe and health environments for children; (3) the communication between various partners and agencies to ensure limited resources are used effectively.109

2015: Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission

The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2013 established a Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission (MCRMC) to provide the President and Congress with specific recommendations to modernize pay and benefits for the armed services.110 In 2015, the MCRMC submitted its final report. Pertinent recommendations of the report include the following:

- Establish standardized reporting of child care wait times.

- Exempt child care personnel from future departmental hiring freezes and furloughs.

- Support current DOD efforts to streamline CDP position descriptions and background checks.

- Reestablish authority to use operating funds for minor construction projects when building, expanding, or modifying CDP facilities.

One of the Commission's recommendations was to improve access to child care on military installations by ensuring DOD has the information and budgeting tools to provide child care within 90 days of need. Section 564 of the Senate version of the FY2016 NDAA would have required a biennial survey of military families to include, "adequacy and availability of child care for dependents of members of the Armed Forces." The House bill did not include a similar provision, and this requirement was not adopted.

MILCON Funding and CDP Facilities

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2006 (P.L. 109-163 §2810) authorized use of O&M funds for minor military construction for the purpose of constructing CDCs. The services used this authority to add over 9,000 child care spaces through additions and renovations to existing facilities.111 The original authority was set to expire in 2007, but was extended through 2009, in the FY2008 NDAA (P.L. 110-181 §2809), when it lapsed. The MCRMC recommended reauthorization of this provision which allows the Secretary concerned to spend up to $7.5 million from appropriations available for O&M on a minor military construction project that creates, expands, or modifies a CDC. The MCRMC also proposed an amendment to 10 U.S.C. §2805 that would raise the statutory threshold for a minor military construction project to $15 million for CDC-related construction projects.112 These provisions have not been adopted.

Recent Congressional Action

CDC Hours of Operation

On January 28, 2016, then-Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter announced enhancements to the military child care program as part of a broader "Force of the Future" military personnel reform initiative.113 DOD's proposed changes would extend the hours of military child care centers from 12 hours to a minimum of 14 hours per day to ensure that hours of operation are consistent with servicemember work hours at various installations.114 For example, for a normal workday of 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., the center would be open from 5:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Military servicemembers would be eligible to receive 12 hours of subsidized care and for any time over 12 hours the member would have to pay the full cost of care out of pocket. A provision of the FY2018 NDAA requires the Secretaries of the military departments to consider the "demands and circumstances" of the active and reserve component patrons of CDCs when setting and maintaining CDC hours of operation. The matters to be taken into account are the following:

- 1. Mission requirements of units whose members use the child care development center;

- 2. The unpredictability of work schedules, and fluctuations in day-to-day work hours, of such members;

- 3. The potential for frequent and prolonged absences of such members for training, operations, and deployments;

- 4. The location of the child care development center on the military installation concerned, including the location in connection with duty locations of members and applicable military family housing; and

- 5. Such other matters as the Secretary of the military department concerned considers appropriate for purposes of this section.115

Child care Staff Hiring Authorities

Congressional concerns about reductions in military child care services related to adequate staffing arose early in 2017 in response to an executive branch hiring freeze decreed by the Trump Administration. While certain child care positions received exemptions, implementation of the hiring freeze highlighted some preexisting recruitment and hiring issues for CDC positions. In particular, military officials noted substantial lag times for vetting new employees due to background check requirements.116

In the FY2018 NDAA, Congress took action to modify hiring authorities for those providing military child care services.117 This legislation also authorized the Secretaries of military departments to provide child care coordinators at installations with "significant numbers" of military personnel and dependents. The direct hire authority allows the Secretary of Defense to recruit and appoint qualified child care services providers to CDC positions if the Secretary determines that (1) there is a critical hiring need, and (2) there is a shortage of providers.118 The FY2018 bill also required a review of the General Schedule pay grades for DOD child care services provider positions to ensure that, in the words of the Senate committee report, "the department is offering a fair and competitive wage" for those positions. The FY2020 NDAA further expanded this authority to include those working in an administrative capacity as family child care school age child care coordinators and personnel working in installation housing offices.119

Issues for Congress

Potential issues for Congress regarding military child care services include the following:

- Should DOD provide child care support?

- What are the pros and cons of different types of child care support?

- Are there other oversight concerns for DOD's CDP?

These issues are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Should DOD Provide Child care Support?

Debates about the provision of publicly funded child care programs often arise from philosophical differences regarding the role of government. Those who oppose government support of child care programs typically express social, fiscal, or equity concerns. Some contend that child care should be a parental responsibility rather than a social good to be provided by the government.120 Some believe that it is best for a mother to stay home with her children and that when the government provides economic incentives for work outside the home it expresses a societal preference for out-of-home care.121 Some carry this argument further and contend that subsidized child care endorses and incentivizes single-parenthood or unstable family arrangements, which they contend may have negative economic and social consequences.122 Research from a Canadian effort to introduce universal subsidized child care in one province found some evidence suggesting that in the short run, children and families experienced some undesirable outcomes, including negative behaviors among children (e.g., hyperactivity, aggressiveness) and reduction in parental relationship quality.123

On the other hand, those who advocate for publicly funded child care programs often argue that child care provides societal benefits and should be a community resource in the same manner as schools, libraries, and parks.124 In 2017, the birthrate in the U.S. was the lowest in 30 years.125 Falling birthrates can have some societal consequences, such as diminished economic growth and increased strain on entitlement programs such as Social Security. Some studies have shown that accessible and affordable child care helps improve fertility rates as well as labor-force outcomes for women, who are often the default caregivers, allowing them to pursue a career and earnings outside of the home.126

For children, center-based child care is associated with both positive and negative social and behavioral outcomes relative to those who receive home-based or parental care.127 Effects are generally small, and depend on factors such as the length of time per day spent in care and the child's temperament and home environment.128 On the other hand, high-quality center-based care is generally correlated with slighter better cognitive, social, academic, and language skills. These benefits are more pronounced for children from low-income households, and gains are sustained through adulthood.129

Pointing to these potential positive outcomes for children and parents, some contend that it is in the government's best interest to regulate and/or subsidize child care services to ensure broad access to high-quality care as a societal good. In the military, this means that junior enlisted members, who generally have lower earnings, may have access to higher quality care than they would be able to otherwise afford. This could have first-order effects of better financial security for junior enlisted and single-parent military families through greater opportunities for spousal employment and lower child care fees. Some advocacy groups and researchers have gone further and argue that the federal government has a national security interest in the provision of high-quality child care for members, since it can improve the quality of the eventual recruiting pool for the military.130 Some studies have found that youth with a military family member are more likely to serve, and approximately one-third of new military recruits have a parent who has served.131 This suggests that early investments in children of military families may provide indirect long-term benefits to the military services.

Some opponents of government-sponsored child care suggest that use of taxpayer dollars to subsidize single-parent families or those with two working parents is inherently inequitable or discriminatory against those without children or those families with one parent who stays at home to care for children.132 Others suggest that the federal government should play a smaller role in the provision of social welfare programs such as subsidized child care, and that these programs are better funded by state and local governments, or through private/nonprofit groups where there may be more accountability for the allocation of funds.133 In terms of DOD-funded child care programs, military leaders and other experts have raised concerns about rising personnel costs and the resulting pressure on defense budgets, particularly during times of fiscal austerity or growth in the size of the force.134 Some have raised concerns that in a resource-constrained environment, the increased spending on personnel benefits could crowd-out spending on other war-fighting capabilities.135

Those who advocate specifically for DOD-sponsored child care services point to expansion of family-friendly benefits among private sector employers and suggest that these benefits help make DOD a more attractive employer. DOD's ability to offer competitive benefits becomes increasingly important in order to attract and retain talent during periods of force growth and times when the economy is strong and there is low civilian unemployment.

What are the Pros and Cons of Different Types of Child care Support?

While some may debate whether DOD should provide child care services at all, another consideration for Congress is whether certain child care activities should be funded or incentivized over others. Currently DOD's CDP includes a mix of direct provision of on-installation care with government employees in government-owned facilities (i.e., CDCs), and subsidized and regulated private care (e.g., FCCs and fee assistance programs). Factors to take into account when considering the pros and cons of different child care support programs include cost, accountability, and parental preferences.

Family Care Centers (FCCs)

Proponents of FCCs note that they are lower cost to the services. A 2002 RAND study found that the average annual cost per infant (age 6 weeks -12 months) in a CDC was more than twice as much as the average annual cost per infant in an FCC.136 In general, while DOD subsidizes FCC fees, FCCs have lower overhead costs. Care is provided in private residences, and operational costs are typically the responsibility of the FCC provider.137 One FCC home coordinator may be assigned to multiple homes or work on a part-time basis, whereas CDC administrative staff members are likely to be full-time employees.138

Another purported benefit of FCCs is that they provide an opportunity for military spouses to own and operate a business while caring for their own children. In 2015, the Navy reported that 94% of FCC providers were military spouses.139 This may let FCCs provide employment opportunities to military spouses while also freeing space at a CDC for other children (e.g., children of dual-military couples or single parents). In-home centers may have more flexibility for drop-in/respite services, care for sick children, and care outside "normal" working hours. An Air Force survey of FCC providers found that just over half were willing to offer extended duty and weekend care, while 24% were willing to offer overnight care.140 In addition, FCC care is available for infants from four weeks old while CDC care eligibility starts at six weeks.141 The number of children in FCCs is capped at six children at any one time. Some parents may prefer a smaller, in-home setting to the day care center environment. Other parents may prefer FCCs because they can allow parents to exercise more discretion over the care setting and the caregivers that are most suitable to their child's needs.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations to in-home care. In many cases, in-home care is operated by military spouses who may be subject to frequent or short-notice permanent change of station (PCS) orders. In addition, if the FCC operator falls ill or takes leave time, there may not be available back-up caregiving options. These factors could affect continuity of care for FCC patrons. The potential for frequent moves may also deter some military spouses from establishing an FCC if the time and resources needed to start up and certify home-based care in a new location are overly burdensome. The services have estimated that the amount of time it takes to certify a new FCC (including background checks, home inspections, and training and orientation) is anywhere from two to nine months.142 In addition, while FCC homes are certified and inspected, there is the potential for less oversight of safety and quality of care than in government-operated facilities.

Center-Based Care (CDCs)

While CDCs may be more expensive for DOD to operate, they may be more preferable to servicemembers in terms of stability, convenience, continuity of care, and oversight. Like FCCs, CDCs also provide employment, training, and development opportunities for military spouses. CDCs are sometimes housed in purpose-built facilities, have a larger staff component, and can handle more children than FCCs. In addition, CDCs are typically located on the military installation where the servicemember is assigned, providing convenience (FCCs may be located on or off the installation). On the other hand, some research has found that children in center-based care are ill more often than children in home-based care, which could lead to more time off from work for military parents.143

From the DOD perspective, the cost of building, operating, and maintaining CDC facilities may be significant. DOD has noted that there is "a continued need for repairing and replacing aging facilities in addition to building new facilities."144 At the same time, 2016 data shows that 70% of married servicemembers live off the military installation.145 While some members may favor care on the installation because it is closer to their workplace, it may be more convenient or preferable for the member and his or her spouse to have care located near the family's residence—in the civilian community. A 2006 study found that the propensity to use CDC care decreases the farther a family lives from the installation.146

Fee Assistance

There are some potential benefits to the fee assistance program in comparison to the DOD-run care facilities. First, within DOD's certification requirements for the fee assistance programs, parents may have a broader range of choice over the model of care and developmental curriculum (e.g., Montessori, parochial, home-based). Second, by participating in community-based child care, military families may have more opportunities to build social networks and connections with nonmilitary families in their neighborhoods. A recent survey of military families found that approximately half of the families "feel like they don't belong in their local civilian community," and would like more opportunities to build local networks.147 In addition, survey respondents indicated school and child care as one of the top opportunities to increase local connections. Some evidence suggests that fee assistance programs may also be a better fit for families that do not live on military installations.

A 2006 study reported, "Across the board, families living off base are more likely to choose formal civilian child-care options over the DoD CDC, and propensity to use civilian child care increases as the distance from an installation grows."148 Fee assistance programs may be particularly beneficial for reservists, who often live farther from military installations and do not have access to CDCs or FCCs. Also, subsidizing private child care programs could have broader spillover effects. DOD's high standards and criteria for private provider eligibility could serve to improve the quality of child care services within the community for both military and civilian families.

A potential limitation of the fee assistance programs for non-DOD affiliated providers is that these private providers may be less likely to offer services that cover extended or unusual duty hours (e.g., nights, weekends, or shift work). Some in the Congress have expressed concern about the privatization of quality of life services such as child care and its potential impact on quality of care.149 In addition, GAO found that some families using fee assistance off-installation care still had higher costs than those offered by on-installation care.150 Some military families have also expressed frustration that under the current fee assistance program their preferred private child care providers do not meet the DOD standards and thus are ineligible for fee assistance subsidies.

Cash Stipends

DOD's fee assistance program makes payments directly to child care providers. Another option would be to supply fixed stipends to military parents to subsidize child care. Currently, military personnel receive basic allowances for housing (BAH) as cash payments and those with dependents receive more BAH than those without. This type of system would have similar benefits to the current fee assistance program, but could offer parents even more choice and flexibility in selecting child care providers. Supporters of such a system argue that cash benefits are generally more efficient than in-kind benefits, since members can more easily assess the value of the benefit.151 Past focus groups with military families have revealed that among parents who used the CDC's, many were unaware that they were receiving a subsidy from DOD and some even believed DOD was profiting from the CDCs.152

Nevertheless, an unrelated survey of military personnel found that a substantial majority "would rather maintain access to existing quality of life benefits than exchange those benefits for cash vouchers."153 In addition, depending on how the benefit system was designed, oversight, accountability, and management may be more challenging. Questions that would need to be addressed with such a program include the following.

- Would military sponsors be required to show proof of care (e.g., receipts) to receive cash benefits?

- Would cash benefits be provided on a per-child basis? Would it vary by the child's age?

- Would families with nonworking spouses be eligible to receive a stipend?

- Would child care stipends be a flat rate (similar to basic allowance for subsistence) or vary by geographic location and prevailing market rates (similar to BAH)?

A cash stipend system that would allow parents to choose any child care provider, regardless of certifications, could result in the purchase of lower-quality child care than what could be provided through the current DOD system.

Other Federal, State, and Local Child care Support

In terms of non-DOD financial support for child care, there are a number of state and federal programs that offer financial assistance in the form of grants, subsidies, and/or tax credits. For example, servicemembers with eligible out-of-pocket child care expenses can claim the federal child and dependent care tax credit to help offset some of their child care costs. Taxpayers receive this credit annually when they file their income tax return, which can be many months after child care expenses are incurred and, hence, may provide little benefit to those who cannot afford upfront child care costs.154 In addition to the tax credit, under current law employers can choose to provide their employees with up to $5,000 in tax-free child care assistance, often delivered in the form of a flexible spending account (FSA). This benefit is not included in employee wages, so it is not subject to income or payroll taxes. Some military advocates have called for DOD to implement FSAs for military servicemembers to allow them to use pre-tax dollars to pay for child care services.155 The FY2010 NDAA expressed a sense of Congress that the Secretaries concerned should establish procedures to implement FSAs for uniformed servicemembers.156

Information on other federal and state services and benefits may be provided by installation referral and resource centers to military members as part of welcome packets following a permanent change of station (PCS). Some private child care centers also offer their own forms of assistance such as discounts for military-connected children, multiple children, negotiable rates, scholarships, and sliding-scale fees based on income.

Other CDP Oversight Issues

Beyond the mix of child care services that Congress chooses to fund through annual appropriations, there are also oversight issues related to access, equity, and quality. In general, military families have high satisfaction with DOD-sponsored programs. Some have pointed to the military child care system as a model that private employers or other government agencies may look to emulate.157 Others point to military families expressing frustration over matters such as lack of awareness of the range of non-CDC support available, CDC wait list management issues, a desire for longer or more flexible CDC hours and other supplemental care options, and the need for more spots for infants.

Awareness of Benefits

A 2012 GAO study found that some servicemembers, particularly those in the Guard and Reserves, have noted that they are not aware of all the services available to them, in particular, subsidized services available in local communities.158 Others were unaware of eligibility requirements, or of the need to apply early for waiting lists upon learning that they were expecting a child or were being transferred to a new installation.159 There are multiple avenues through which DOD and the military services conduct outreach to members about child care services, including handouts and posters on installations, newcomer or pre-deployment briefings, or other referral offices and websites (e.g., MilitaryOneSource.mil).

Some of the actions that the services have taken to address these issues are assigning dedicated resource and referral staff, providing targeted information for expectant parents, and developing sponsorship programs for those transferring to a new installation. In 2015, DOD launched MilitaryChild care.com as an online portal with helpdesk support for members to find information about child care services, to submit requests for care, and to be placed on waiting lists for military CDCs. The implementation of this initiative was completed in phases ending in June 2017. For members looking for off-installation care under the fee assistance or respite programs, Child Care Aware of America, operates an online portal that assists military families in finding accredited care centers, determining eligibility, and applying for subsidies.160 Potential measures for evaluating effectiveness include member satisfaction with the online portal and processes and usage and site-view statistics.

CDC Wait List Management

DOD's militarychildcare.com initiative was intended, in part, to address servicemember grievances about wait list management by integrating individual installation wait list processes into one DOD-wide system and providing more visibility into members' standing on such lists. Concerns still remain about the length of waiting lists, particularly on large bases or in high-demand areas, and how wait list priority is determined.161 DOD's target for the amount of time that a family spends on a wait list is 90 days.162 However, in 2014 the Services estimated average wait list times to be three to nine months.163 Some family advocacy groups have argued for higher wait list priority for certain active servicemembers over DOD civilian employees. They have noted that frequent PCS moves for military families—sometimes on short notice or with last minute extensions or delays—preclude military families from obtaining favorable spots on waiting lists, whereas civilian personnel move less frequently and generally have more notice prior to moves.164 Others have argued for income-based placement on wait lists, which would prioritize CDC placement for families who could least afford quality, off-installation care. Current law requires DOD to set fees based on family income, but does not establish priority categories for military child care wait lists.165

In the FY2020 NDAA, Congress requires DOD to take remedial actions to "reduce the waiting lists for child care at military installations to ensure that members of the Armed Forces have meaningful access to child care during tours of duty."166 A report on actions taken to address wait list issues is due to the Congress on June 1, 2020. In February 2020, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper announced a new policy for wait list management that prioritizes access for military families over DOD civilians (see Appendix).167 Families are required to apply for care through the militarychildcare.com (MCC) website, which will continue to be the primary wait list management platform.

CDC Capacity

The amount of time a military family spends on a wait list is a function of both geographic demand and CDC capacity. This capacity, in turn, depends on the size of the facility and the number of CDC employees. Options to expand capacity on high-demand installations would be to build new CDC facilities and to expand or refit existing space. Potential barriers to this include lack of available or appropriate physical space on certain installations and lack of the military construction funding that would be required. In addition, construction projects often have long lead times (to account for appropriating funds, the contracting process, and the design and build) and may not be able to accommodate short-term surges in demand. If physical space is available, one other limitation is the availability and ease of recruiting and hiring child care workers to maintain required caregiver-to-child ratios. In the past, issues such as federal hiring freezes and pace of background checks has slowed the pace of hiring for CDCs. Some of these staffing issues were addressed in the FY2018 NDAA as discussed in a previous section (see "CDC Hours of Operation").

In the FY2020 NDAA, Congress authorized an additional $158 million in MILCON funding for DOD to carry out construction projects for CDCs on military installations. Funding for the projects is contingent on congressional notification and approval for DOD's construction plans.168

Appendix. Patron Priority for CDCs

|

Priority Category |

Eligible Patrons |

|

Priority 1A |

CDP Direct Care Staff The children of Direct Care CDP staff will be placed into care ahead of all other eligible patrons. At no time will the child of a Direct Care CDP staff member be removed from the program to accommodate another eligible patron. |

|

Priority 1B |

Single or Dual Active Duty Members; Single or Dual Guard or Reserve Members on active duty or inactive duty training status; and servicemembers with a fulltime working spouse. Priority 1B children will be placed into care ahead of all other eligible patrons except Priority 1A. At no time will a Priority 1B patron be removed from the program to accommodate any other patron, including lA patrons. Order of precedence is (a) Single or Dual Active Duty members. (b) Single or Dual Guard or Reserve Members on Active Duty or Inactive Duty training status. (c) Active Duty with a full-time working spouse. (d) Guard or Reserve Members on Active Duty or Inactive Duty training status with a full-time working spouse. |

|

Priority 1C |

Active Duty Members or Guard or Reserve Members on Active Duty or Inactive Duty Training Status with Part-Time Working Spouse or a Spouse Seeking Employment. Priority 1C children will be placed into care ahead of all other eligible patrons except for Priority lA and 1B patrons. Priority lC patrons may only be supplanted by an eligible patron in Priority lA or 1B when the anticipated placement time of the Priority lA and 1B patron exceeds 45 days beyond their date when care is needed. Order of precedence is

|

|

Priority 1D |

Active Duty Members or Guard or Reserve Members on Active Duty or Inactive Duty Training Status with a Spouse Enrolled in a Post-Secondary Institution on a Full-Time Basis.

Order of precedence is

|

|

Priority 2 |

DOD Civilians DOD civilian patrons may only be supplanted from care by an eligible Priority lA or1B patron when the anticipated placement time of the Priority IA or 1B patron exceeds 45 days beyond their date when care needed. Order of precedence is (a) Single or dual DOD Civilian Employees. (b) DOD Civilian Employees with a full-time working spouse. |

|

Priority 3 |

Space Available Space available patrons will be supplanted by an eligible Priority 1 or 2 patron when the anticipated placement time of the higher priority patron exceeds 45 days beyond their date when care needed. Order of precedence is (a) Active Duty with nonworking spouse. (b) DOD Civilian Employees with spouse seeking employment. (c) DOD Civilian Employees with a spouse enrolled in a post-secondary educational program on a full time basis. (d) Gold Star spouses. (e) Active Duty Coast Guard members. (f) DOD contractors. (g) Other eligible patrons. |

Sources: Secretary of Defense, "Policy Change Concerning Priorities for Department of Defense Child Care Programs," Memorandum from Stephanie Barna, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Readiness and Force Management), Policy Clarification for Priority 1 Access to Department of Defense Child Development Programs, February 21, 2020. DOD, "Child Development Programs," DODI 6060.02, August 5, 2014.

Note: DOD defines a working spouse as a spouse who is hired for a wage, salary, fee, or payment to perform work for an employer; or a spouse who works for oneself as a freelancer or the owner of a business rather than for an employer. In all cases, work may be performed in or out of the home. For the purpose of this instruction, a spouse who is working 30 hours per week or 100 hours per month, or a spouse working less than 30 hours per week or 100 hours per month and enrolled in a postsecondary educational institution will be considered a full-time working spouse.