Introduction

The Department of Defense (DOD) created the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 1958.1 Originally called the Advanced Research Projects Agency, DARPA was established partly in response to the launch of the first Sputnik satellite by the former Soviet Union and partly in recognition of the need to invest resources toward promising concepts requiring a longer timeframe for development.2 In 1972, "defense" was added to the agency's name to emphasize its mission of making "pivotal investments in breakthrough technologies for national security."3

This report provides an overview of DARPA, including the agency's organizational structure, characteristics (i.e., the "DARPA model"), and strategic priorities. The report also describes funding trends at DARPA and discusses select issues for possible congressional consideration, including the appropriate level of funding for the agency, technology transfer, and the potential role of DARPA in maintaining the technological superiority of the U.S. military.

Background

According to DARPA, the agency is focused on research and development (R&D) that is intended to achieve transformative change rather than incremental advances.4 "Transformative" R&D—a term often used interchangeably with revolutionary or "high-risk, high-reward" R&D—is defined by the National Science Board as

research driven by ideas that have the potential to radically change our understanding of an important existing scientific or engineering concept or leading to the creation of a new paradigm or field of science or engineering. Such research is also characterized by its challenge to current understanding or its pathway to new frontiers.5

Since its establishment, DARPA-funded research has made important scientific and technological contributions in computer science, telecommunications, and material sciences, among other areas. Specifically, DARPA investments have resulted in a number of significant breakthroughs in military technology, including precision guided munitions, stealth technology, unmanned aerial vehicles, and infrared night vision technology.6 DARPA-sponsored R&D has also led to the development of notable commercial products and technologies such as the internet, global positioning system (GPS), automated voice recognition, and personal electronics.7

The nature of the high-risk, high-reward approach to funding taken by DARPA also results in a number of failed or less successful projects. For example, in the 1970s DARPA supported research into paranormal phenomena and the possibility of using telepathy and psychokinesis to conduct remote espionage.8 The agency also supported the development of a "mechanical elephant" for transportation in the jungles of Vietnam that former DARPA Director Rechtin termed a "damn fool" project and terminated before it could come under scrutiny by Congress.9

In 2003, the Total Information Awareness (TIA) program attracted congressional attention. The goal of the Total Information Awareness program was to "revolutionize the ability of the United States to detect, classify and identify foreign terrorists—and decipher their plans" by creating a large database of information that could be "mined" using new tools and techniques to identify actionable intelligence.10 Some Members of Congress, the American Civil Liberties Union, and others criticized the program as an abuse of government authorities and an infringement on the privacy of Americans.11 In Section 111 of the appropriations bill for FY2003 (P.L. 108-7) Congress limited the use of funds for the TIA program and expressed the sense of Congress that the program "should not be used to develop technologies for use in conducting intelligence activities or law enforcement activities against United States persons without appropriate consultation with Congress or without clear adherence to principles to protect civil liberties and privacy."

In more recent years some DARPA programs have failed to meet expectations. For example, in 2011, the Falcon Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 failed to meet expectations—exploding 9 minutes into a 30-minute planned test flight when large portions of the vehicle's outer shell peeled away.12 The program ended in 2011. Additionally, in 2020, DARPA ended its Launch Challenge without awarding a winner. Of the three teams qualifying for the final event—Virgin Orbit, Astra, and Vector Space—Astra was the only team to compete and the company ended up scrubbing the launch due to an issue with the rocket's guidance, navigation, and control system.13

These less successful and sometimes high-profile failures highlight DARPA's willingness to invest in high-risk, high-reward R&D. Despite such setbacks, the agency is frequently cited as a model for innovation that other agencies, outside groups, and Congress have sought to replicate across the federal government. For example, both the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E) within the Department of Energy were modeled after DARPA with a focus on high-risk, high-reward research in their respective areas. The "DARPA model" is discussed in more detail later.

Organizational Structure

DARPA is an independent R&D agency of the U.S. Department of Defense. Over the course of DOD's history, leadership for research, engineering, and technology development has existed at various levels within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, including an Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering and a Director of Defense for Research and Engineering. Currently, the Director of DARPA reports through the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering to the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD R&E).14 In general, DARPA's role and position within DOD has allowed the agency to have close ties to senior DOD officials, helping the agency maintain its independence and focus on transformative R&D.15

DARPA has more than 200 government employees, including 100 program managers who oversee the agency's annual budget of roughly $3 billion. DARPA does not directly perform research or operate any research laboratories, but rather executes its R&D programs mainly through contracts with industry, universities, nonprofit organizations, and federal R&D laboratories.

DARPA is a relatively flat organization consisting of the Director's Office; six technical program offices; the Adaptive Execution Office; the Aerospace Projects Office; the Strategic Resources Office; and the Mission Services Office.16 DARPA's six technical program offices are the

- Biological Technologies Office, responsible for the development and use of biotechnology for technological advantage, including neurotechnology, human-machine interface, human performance, infectious disease, and synthetic biology R&D programs.

- Defense Sciences Office, focused on mathematics and modeling, the physical sciences, human-machine systems, and social systems.

- Information Innovation Office, responsible for basic and applied research in cyber, analytics, and human-machine interfaces.

- Microsystems Technology Office, focused on R&D on the electromagnetic spectrum, information microsystems, and the security and reliability of microelectronics.

- Strategic Technology Office, responsible for developing technologies that enable fighting as a network (i.e., the use of multiple platforms, weapons, sensors, and systems simultaneously) to improve military effectiveness, cost, and adaptability, including battle management, command and control, and electronic warfare.

- Tactical Technology Office, focused on developing and demonstrating new platforms in ground, maritime (surface and undersea), air, and space systems, including advanced autonomous and unmanned platforms.

DARPA's other offices are the

- Adaptive Capabilities Office, responsible for working with the military services to develop joint capabilities and new concepts of operations by combining emerging technologies and new warfighting concepts.

- Aerospace Projects Office, a special projects office created in 2015, focused on the development of advanced aircraft technologies to ensure air dominance in future contested environments.

- Strategic Resources Office and the Mission Services Office, responsible for agency support activities, including human resources services and business enterprise and operations support.

The DARPA Model

The "DARPA model" is often cited by Congress and others when discussing how to improve the ability of the federal government to spur innovation through its R&D investments. DARPA officials contend that its organizational structure allows the agency to operate in a fashion that is unique within DOD, as well as the entire federal government. Specifically, DARPA officials assert that the agency's relatively small size and flat structure enable flexibility and allow the agency to avoid internal processes and rules that slow action in other federal agencies.17 Additionally, in his 2007 testimony before the House Committee on Science and Technology, Dr. Richard Van Atta, a defense policy analyst, stated, "a crucial element of what has made DARPA a special, unique institution is its ability to re-invent itself, to adapt, and to avoid becoming wedded to the last problem it tried to solve."18

DARPA attributes its long history of successful innovation to four factors: (1) trust and autonomy; (2) limited tenure and the urgency it promotes; (3) a sense of mission; and (4) risk-taking and tolerance for failure.19 These factors generally manifest themselves through the agency's approach to its program managers. Some assert that the key to DARPA's success "lies with its program managers."20

Trust and Autonomy

The level of trust and autonomy provided to DARPA program managers is unique across the federal government. DARPA expects its program managers to play a key role in the technical direction of each project. Specifically, unlike most program managers in federal R&D agencies, DARPA program managers are charged with creating new programs and projects and quickly funding innovative ideas. Although DARPA program managers can use peer review to help them evaluate the merit of an R&D proposal, they are not required to do so and are in effect responsible for the selection, and, if necessary, the termination of a project.21 This is in contrast to program managers at the National Science Foundation who, in general, inherit existing programs, are required to use peer review panels to determine the quality of a proposal, and select projects based primarily on the rankings provided by the review panel.22

Limited Tenure

Another key feature of DARPA's approach to program management is that program managers are hired for a limited tenure, generally three to five years. DARPA believes that the continued influx of new program managers infuses the agency with new ideas and personnel who have a passion for turning those ideas into reality as quickly as possible. DARPA estimates that 25% of its program mangers turn over annually.23 According to the agency, "in most organizations that would be considered a problem; at DARPA, it is intentional and invigorating. A short tenure means that people come to the agency to get something done, not build a career."24

However, some contend that the high turnover rate of program managers can result in duplicative efforts due to a lack of institutional memory.25 Concerns have also been raised that the recruitment process used by DARPA—existing or previous program managers identify new program managers—might contribute to a gender imbalance (DARPA program managers are typically men) and the selection of individuals from the same network of researchers, which could lead to a stagnation of new ideas and perspectives.26

Limited tenure and urgency is also reflected in how DARPA funds its projects. In general, DARPA funds an idea or project just long enough to determine its feasibility, typically three to five years. If a program manager believes a new idea is not working out, the program manager can terminate the project quickly and funds can be redirected to a new project or an existing project with more potential. Specifically, DARPA projects are evaluated on the basis of milestones established by program managers in advance of the start of the program; progress toward these milestones is used to evaluate whether continued funding is merited.

Sense of Mission

DARPA asserts its mission "to prevent and create technological surprise" is an important factor in reinforcing and driving the innovative culture of the agency.27 Specifically, DARPA contends

The importance and ambition of the mission help fuel the drive toward innovation. People are inspired and energized by the effort to do something that affects the well-being and even the survival of their fellow citizen.28

Risk-Taking and Tolerance for Failure

DARPA's approach to risk is also unusual and is a well characterized element of the agency's success.29 DARPA asserts that its program managers often reject projects for not being sufficiently ambitious and views failure as the cost of supporting potentially transformative or revolutionary R&D. To mitigate the costs of failed projects, DARPA funds projects for a limited time and is willing to reallocate funds from underperforming projects.30 DARPA's culture of risk-taking and tolerance for failure are among the most cited attributes some in Congress and others seek to replicate in other federal agencies supporting R&D.

Other Factors

Some experts have noted additional factors as important contributors to the DARPA model and its success. These factors include multigenerational technology thrusts (i.e., support for a suite of technologies and ideas in a given area over an extended period of time); connection to the larger innovation ecosystem; the agency's ties to leadership at DOD; and its role as an initial market creator or first adopter.31

Hiring and Contracting Flexibilities

Congress has provided DARPA with additional authorities that many believe are key contributors to the agency's record of successful innovation and essential to the DARPA model. These include flexibility in the hiring of personnel and the mechanisms it can use for acquiring goods and services and providing financial assistance. For example, in response to a question on the authorities Congress needed to grant DARPA to maintain a culture of innovation, former DARPA Director Dr. Arati Prabhakar stated

The tools that this committee has already helped us with I think are critically essential—number one, bringing in people from all different parts of the technical community. Not just those who already live in the DOD [Science and Technology] world, but people who come with backgrounds in commercial companies or having done startups or people out of universities—those different perspectives are very helpful.

Our ability to contract with entities that aren't normally in the business of doing business with the Federal Government through other transactions authority that is another way that allows us to reach farther in terms of technology and ... get access to some of these bleeding edge technologies.32

In 1998, Congress established an experimental program for hiring scientific and technical personnel at DARPA (P.L. 105-261). Specifically, the program granted DARPA the authority to directly hire experts in science and engineering from outside the federal government for limited term appointments (up to six years). It also exempted the agency from complying with traditional civilian personnel requirements, thereby allowing DARPA to streamline its hiring process and increase the level of compensation it could offer scientists and engineers. Many in Congress viewed this flexibility in hiring as improving DARPA's ability to recruit and retain eminent scientific and technical experts. Congress routinely extended the duration of the experimental personnel program between 1998 and 2015. Congress made the hiring authority permanent in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 (P.L. 114-328). In 2019, Congress increased the number of personnel DARPA can hire under the authority from 100 to 140 (P.L. 116-92).

In 1989, Congress granted DARPA "other transactions (OT) authority."33 There is no statutory or regulatory definition of "other transaction." An OT is an acquisition mechanism that does not fit into any of the traditional mechanisms used by the federal government for acquiring goods or services—contracts, grants, or cooperative agreements. OTs do not have to comply with the government's procurement regulations. Only those agencies that have been provided OT authority may engage in other transactions. Generally, the reason for creating OT authority is that the government needs to obtain leading edge R&D or prototypes from commercial sources that are unwilling or unable to navigate the government's procurement regulations. OT authority is generally viewed as giving federal agencies additional flexibility to develop agreements tailored to the needs of the project and its participants.34 In 1991, Congress made DARPA's OT authority permanent and extended it to DOD broadly.35 In 1993, Congress provided DARPA with authority to use OTs for prototypes; this authority was subsequently extended to the entire department in 1996 and made permanent in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (P.L. 114-92).36

DARPA's Role in DOD and Selection of R&D Programs

DARPA's R&D efforts are generally long-term in character and often in areas where the national security or defense need is initially unclear.37 As such, DARPA-supported research does not generally produce immediate, tangible results. In his 2017 testimony before Congress, Dr. Steven Walker, who was then Acting Director of DARPA, described the agency's role as

in large part to change what's possible—to do the fundamental research, the proof of principle, and the early stages of technology development that take impossible ideas to the point of implausible, but surprisingly possible. No other agency within the Defense Department has the mission of working on projects with such a high possibility of failure—or such a high possibility of producing truly revolutionary new capabilities.38

When DARPA was established in 1958 it was created as an independent R&D agency explicitly separate from the R&D organizations of the military services. This construct has allowed DARPA to support R&D and technology efforts that are not tied to formal military requirements or to the specific roles or missions of the military services.39 Instead DARPA's role in the DOD R&D enterprise has been to cut across the traditional jurisdictions of the military services and to explore new and unconventional concepts that have the possibility of leading to revolutionary advances in the technological capabilities of the military—potentially revising the traditional roles and missions of the military services.

Overall, DARPA takes a portfolio approach to its R&D investments and program activities (i.e., it addresses a wide range of technical opportunities and national security challenges simultaneously). However, the agency's program managers play a major role in selecting the R&D supported by the agency. This "bottom-up" approach is deemed effective by DARPA because its program managers, who are university faculty, entrepreneurs, and industry leaders, are seen as the individuals closest to the technical challenges and potential solutions and opportunities in a given field. DARPA considers this connection to the R&D and entrepreneurial community critical to driving innovation and risk-taking within the agency's activities.40 Additionally, DARPA often holds conferences, sponsors workshops, and supports travel by its program managers and its leadership to ensure the agency is fully informed of current and cutting-edge technologies and research. Ideas or R&D areas addressed through the agency's programs also come from the "top-down," including from DARPA leadership and from the military services who articulate the needs and challenges of the warfighter to the agency. Ultimately, DARPA leadership is responsible for setting agency-wide priorities and ensuring a balanced investment portfolio.

DARPA Strategic Priorities

In 2019, DARPA released a document outlining the agency's current areas of focus.41 Specifically, as described by DARPA, the agency is focusing its investments on four strategic initiatives:

Defend the homeland: Defending the homeland involves an array of completely new capabilities ranging from autonomous cybersecurity, to strategic cyber deterrence, to weapons of mass destruction sensing and defense, to active bio-surveillance and bio threat countermeasures. Because we know peer competitors have been developing hypersonic weapons, near-term development of defenses against these weapons also is paramount.

Deter and prevail against high-end adversaries: Succeeding against peer competitors in Europe (a stand-in scenario) and in Asia (a standoff scenario) requires new thinking. Realizing new capabilities across the land, sea, and air domains will be important, but space and the electromagnetic spectrum will be just as or more important in deterring conflict away from our shores. New capabilities must be developed, fielded, and operated with speed and adaptability to stay ahead of increasingly capable adversaries.

Prosecute stabilization efforts: The United States needs to get better at rapidly adapting to different environments. In particular, we need capabilities to address informal, unconventional gray-zone conflicts and city-scale warfare, along with rigorous and reliable models to better understand and predict our adversaries' moves prior to engagement.

Advance foundational research in science and technology: Basic research underlies all of DARPA's grander pursuits and is what makes possible never-before-seen capabilities. Ultimately, the goal of the agency's fundamental R&D investments is to understand where technology is leading us and to further develop and apply that technology with purpose, solving the nation's toughest security challenges. The best way to prevent technological surprise is to create it, ensuring that U.S. warfighters and our allies have access to the most advanced technologies and capabilities first. Research funded by DARPA in the near term will explore science and technology that leads to "leap ahead" solutions for specific current and future threats across multiple operational domains. Highest priority is assigned to investments that enable the country to maintain a technological advantage over adversaries while ensuring maximum deterrence.42

In 2015, as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (P.L. 114-92), Congress repealed a provision requiring DARPA to prepare and submit a biennial strategic plan to Congress describing the agency's long-term strategic goals; the research programs developed in support of those goals; the agency's technology transition strategy; the policies governing the agency's management, organization, and personnel; and the connection between DARPA's activities and the missions of the military services.

DARPA Appropriations and Funding Trends

DARPA funding is appropriated through the Defense-wide Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) account, which generally falls under Title IV of the annual defense appropriations act.43 The 2020 Defense-wide RDT&E account includes 17 other DOD organizations. Program elements within the account provide support for particular RDT&E activities within each DOD R&D organization, including DARPA. The program elements also describe DOD's R&D funding by the character of work to be performed (e.g., basic research). The character of work consists of a budget activity code (6.1 through 6.7) and a description (see Table 1).

Nearly all of DARPA's funding falls under the categories of basic research (6.1), applied research (6.2), and advanced technology development (6.3). Funding for the 6.1 to 6.3 program elements is referred to by DOD as the science and technology (S&T) budget. DOD's S&T budget is often singled out by analysts and others for additional scrutiny, as it is viewed as an investment in the foundational knowledge needed to develop future military systems. DARPA's remaining funding falls within the 6.6 budget activity code for management support, which includes personnel salaries and benefits as well as costs associated with travel, supplies, equipment, and office space.

|

Code |

Description |

|

6.1 |

Basic Research |

|

6.2 |

Applied Research |

|

6.3 |

Advanced Technology Development |

|

6.4 |

Advanced Component Development and Prototypes |

|

6.5 |

System Development and Demonstration |

|

6.6 |

RDT&E Management Support |

|

6.7 |

Operational System Development |

Source: Department of Defense, Financial Management Regulation (DoD 7000.14-R), Volume 2B, March 2016.

Notes: For a more detailed description of the types of activities supported within each budget activity code see CRS Report R44711, Department of Defense Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E): Appropriations Structure, by John F. Sargent Jr.

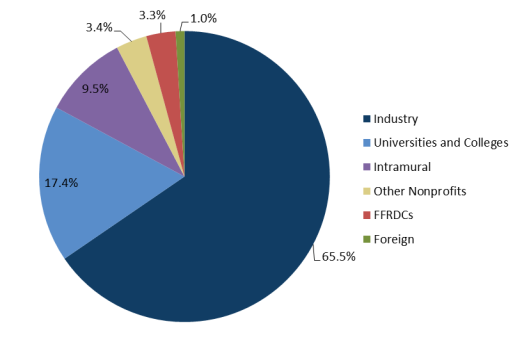

As stated previously, DARPA does not directly perform R&D, but supports R&D through contracts with various R&D performers which include universities and industry. As illustrated by Figure 1, DARPA primarily supports R&D performed by industry. Specifically, in FY2019 more than 65.5% ($2.3 billion) of DARPA's R&D was performed by industry; universities and colleges performed 17.4% ($615.6 million) of DARPA's R&D, followed by intramural R&D performers (e.g., federal laboratories) at 9.5% ($334.6 million), other nonprofits (3.4%; $121.8 million), Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) (3.3%; $115.2 million), and foreign entities (1%; $34.7 million).

Funding Trends for DARPA

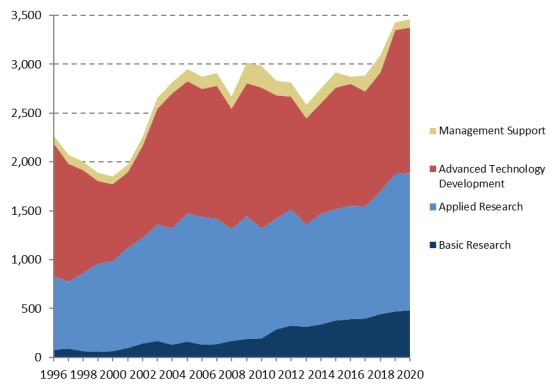

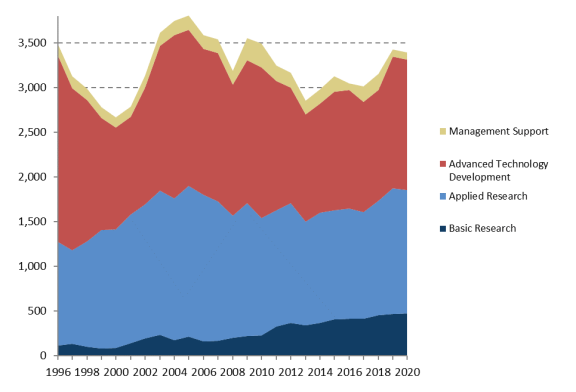

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show DARPA funding trends from FY1996 to FY2020 by character of work (i.e., basic research, applied research, advanced technology development, and management support) in current and constant FY2019 dollars (adjusted for inflation), respectively. In current dollars, overall funding for DARPA has increased by 52.4% from $2.27 billion in FY1996 to $3.46 billion in FY2020, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 1.7% (Figure 2). In FY2019 constant dollars, DARPA funding has decreased by 2.7%, from $3.48 billion in FY1996 to $3.39 billion in FY2020. DARPA funding has averaged $3.23 billion between FY1996 and FY2020 with fluctuations over time (Figure 3). Specifically, funding for the agency decreased by 23% between FY1996 and FY2000 in constant dollars, but then increased by 43% to its highest level in FY2005. Since FY2005, DARPA funding has declined by 11% (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. DARPA Funding by Character of Work, FY1996-FY2020 Obligational authority, in millions of constant FY2019 dollars |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from Department of Defense, Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation Programs (R-1), FY1998-2021. Notes: CRS used the earliest of the three fiscal years of data (actual expenditures) provided in each R-1. For example, the FY2017 funding levels are from the FY2019 R-1. For purposes of this chart, CRS used the GDP (Chained) Price Index from Table 10.1 of the Historical Tables in the President's Budget for Fiscal Year 2021, to adjust for "inflation"; this index is used by the Office of Management and Budget to convert federal research and development outlays from current dollars to constant dollars. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/hist10z1_fy21.xlsx. |

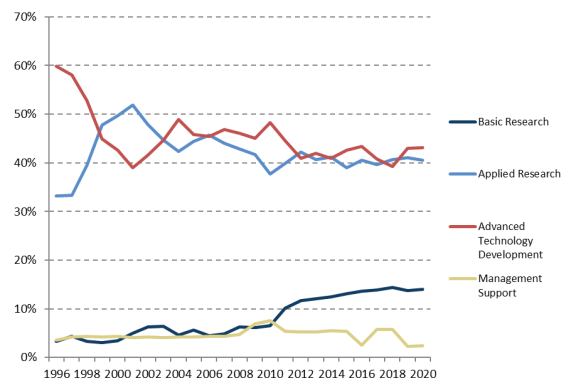

The proportion of DARPA funding supporting basic research has increased steadily over time (Figure 4). In FY2020, basic research accounts for 14% of DARPA funding, up from 3% in FY1996.

The proportion of DARPA funding supporting applied research has fluctuated over time, averaging 42% between FY1996 and FY2020 with a high of 52% in FY2001 and a low of 33% in FY1996 (Figure 4). In FY2020, the proportion of DARPA funding supporting applied research is 41%. The proportion of DARPA funding supporting advanced technology development has also fluctuated over time, averaging 45% between FY1996 and FY2020 with a high of 60% in FY1996 and a low of 39% in FY2001. In FY2020, the proportion of DARPA funding supporting advanced technology development is 43%. The proportion of DARPA funding for management support has remained relatively steady, peaking at 8% in FY2010. In FY2020, the proportion of DARPA funding for management support is 2%.

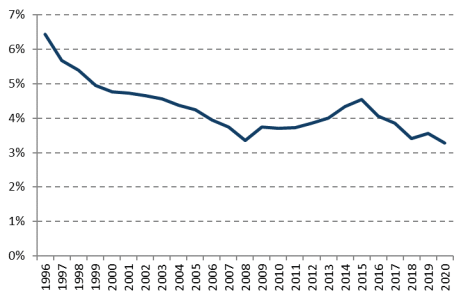

DARPA's goal is to ensure the U.S. military is "the initiator and not the victim of technological surprises."44 As such DARPA's R&D investments are often viewed as a surrogate for high-risk, high-reward R&D within DOD (i.e., R&D focused on revolutionary advances rather than incremental advances). Figure 5 and Figure 6 depict DARPA funding as a share of DOD RDT&E funding (6.1 to 6.7 budget activity codes) and Defense S&T funding (6.1 to 6.3) over time.

Between FY1996 and FY2020, DARPA's share of DOD RDT&E funding has declined from 6.4% in FY1996 to 3.3% in FY2020 (Figure 5).

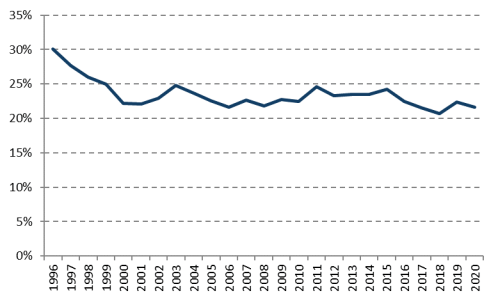

After a decline between FY1996 and FY2000—from 30.1% to 22.2%—DARPA's share of Defense S&T funding has remained relatively steady between 21% and 25% from FY2000 to FY2017 (Figure 6). In FY2020, DARPA's share of Defense S&T funding is 21.6%, up from its lowest level in FY2018 of 20.7%.

Potential Issues for Congressional Consideration

The following sections describe potential issues for congressional consideration, including the level of funding DARPA should receive, the agency's technology transfer activities, the role DARPA can or should play under the DOD Under Secretary for Research and Engineering and in DOD's efforts to maintain technological superiority, and how DARPA incorporates ethical, legal, and societal considerations into the research it supports.

What Is the Appropriate Level of Funding for DARPA?

Support for high-risk, high-reward research is considered by some as essential to maintaining the economic competitiveness of the United States.45 In the context of national security, high-risk, high-reward R&D could lead to the development of technologies that advance or maintain the technological superiority of the U.S. military. In this report, CRS examined DARPA funding as a surrogate for the level of support for high-risk, high-reward, disruptive, or revolutionary R&D conducted within DOD.46

A 2007 report by the National Academy of Sciences recommended that federal research agencies allocate 8% of an agency's budget toward high-risk, high-reward research that the National Academy stated "suffers in today's increasingly risk-averse environment."47 As shown in Figure 5, DARPA's share of DOD RDT&E funding has been below 7% since FY1996. Between FY1996 and FY2020 DARPA's share of DOD RDT&E funding averaged 4.3% and in FY2020 it is 3.3% of the agency's RDT&E funding. It is unclear the extent to which R&D investments by other DOD research organizations could be characterized as high-risk, high-reward, bringing DOD closer to the 8% spending level for high-risk, high-reward research recommended by the National Academy. Regardless, DARPA's share of DOD RDT&E funding has been on a downward trend since FY1996.

A 2017 report examining the best practices of innovative companies by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that innovative companies invest about 80% of their R&D spending on research that is designed to make incremental improvements to their products and 20% of their R&D budget on research in support of disruptive or high-risk, high-reward R&D. Additionally, GAO found that this disruptive R&D is typically conducted by a corporate research organization that is independent from the company's business units. According to GAO, DARPA resembles a corporate research organization in that it is independent from the military services and supports research that is generally not tied to existing weapons systems or specific military department requirements.48 As shown in Figure 6, DARPA's share of Defense S&T funding has remained relatively steady at between 21% and 25% from FY2000 to FY2020 and is comparable to the percentage of R&D devoted to disruptive projects at leading innovative companies.

As shown by the above analyses, the answer to the question "what is the appropriate level of funding for DARPA?" is dependent on the frame one uses when examining the data. In using DARPA's share of the overall DOD RDT&E budget one may determine that DARPA funding should increase; however, in using DARPA's share of the Defense S&T budget one may conclude that current DARPA funding levels are sufficient. Additionally, it is dependent on the goals and objectives of Congress. For example, Congress and others have expressed concern that the United States is at risk of losing its technological advantage and have called for increased innovation within DOD to address the narrowing of the United States' advantage over its adversaries.49 If Congress believes that DARPA should play a larger role in ensuring the technological superiority of the U.S. military then it may consider increased funding for the agency.

Transitioning Technologies from DARPA

The transition of technologies—often referred to as technology transfer—from R&D supported by DARPA to acquisition programs within the military services or other end users is a challenge long recognized by Congress.50 For example, a 2014 committee report from the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services stated

the committee is concerned that some technology projects may be successfully completed, but fail to transition into acquisition programs of record or directly into operational use. This may be because of administrative, funding, cultural, and/or programmatic barriers that make it difficult to bridge the gap from science and technology programs to acquisition programs, as well to the expected users of the technology.51

Barriers to technology transfer include DARPA's goal of creating disruptive or revolutionary technologies. Such technologies, often by design, challenge the status quo and can meet resistance from the military services. For example, according to GAO, the Air Force was initially resistant to investments in stealth technologies for aircraft.52 Risk aversion and resistance within the military services often can only be overcome with sufficient maturation and demonstration of the technologies prior to transition. However, DARPA's funding only supports budget activities from 6.1 to 6.3—basic research, applied research, and advanced technology development—and not the further levels of technology maturation in 6.4 and 6.5—advanced component development and prototypes and system development and demonstration—which could be used to overcome a military service's resistance. In a 2017 report comparing the best practices and management of science and technology programs at leading companies to DOD, GAO noted that companies recognize the difficulty associated with transitioning disruptive technologies and fund their disruptive technology projects through demonstration to help obtain a customer.53 According to GAO, from FY2016 to FY2018, DOD, including DARPA, has significantly increased the use of its other transactions authority for the development of prototypes.54 This increase in prototyping activities may help to overcome the gap in technology maturation funding between DARPA and the department's acquisition programs. Other barriers to technology transfer also exist, including the development of technologies that do not fall clearly within the mission of a particular service and the lack of a clear "customer."

Case studies by GAO and others, however, do indicate that DARPA has succeeded in transitioning some of its technologies to the military services and the private sector. According to GAO, the four factors that contribute to a successful technology transition are

- military or commercial demand for the technology;

- linkage to a research area where DARPA has had a sustained interest;

- active collaboration with the potential transition partner; and

- achievement of clearly defined technical goals.55

As noted by GAO and others, technology transfer is not a primary emphasis of DARPA.56 GAO has found that inconsistencies in the reporting and collection of technology transfer information by the agency make it difficult to reliably report on the overall success of DARPA's transition efforts. GAO first stated its concern regarding the lack of documentation for DARPA's technology transfer activities in 1974.57 More recently, GAO has concluded that DARPA leadership "foregoes opportunities to assess, and thus potentially improve, technology transition strategies" and that technology transition responsibilities fall to individual program managers that GAO believes are not sufficiently trained to achieve successful outcomes.58 Congress may examine the effectiveness of DARPA's Adaptive Execution Office which is responsible for reviewing and implementing the agency's technology transition strategies, including assisting individual program managers.

DARPA's Role and the Under Secretary for Research and Engineering

Over the last several years, some Members of Congress, think tanks, and others have expressed concern that the U.S. military is losing its technical superiority due, in part, to the proliferation of technologies outside the defense sector and the inability of DOD to effectively incorporate and exploit commercial innovations.59 To address this concern, Congress established an Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD R&E) in 2016 that "would take risks, press the technology envelope, test and experiment, and have the latitude to fail, as appropriate."60 In describing the role of the Under Secretary, the Senate Committee on Armed Services stated

the USD(R&E) will be a unifying force to focus the efforts of the defense laboratories, as well as agencies with critical innovation missions, such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and the Missile Defense Agency on achieving and maintaining U.S. defense technological dominance.61

How the USD R&E will "focus the efforts" of DARPA is unclear and an area that Congress may consider defining. In determining the appropriate role of DARPA in DOD's efforts to maintain technological superiority, it may be useful to examine some of the roles DARPA has played in its past. According to the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), DARPA has at various times through its history been the

- focus for large-scale, nationally important technology application areas;

- principal supporter of major areas of basic research and generic technologies with both military and commercial potential;

- developer of specific, large-scale system concepts and prototypes;

- supporter of highly experimental and extremely advanced concepts for weapons, systems, and capabilities;

- developer of operational systems and capabilities for direct application to existing military conflicts;

- funder of research to improve the capabilities of industry to produce defense-related technologies; and

- supporter of fundamental knowledge needed to better understand a phenomena related to a potential defense application.62

It may be appropriate to have DARPA pursue some or all of these roles simultaneously, with varying degrees of emphasis. However, IDA has stated that, historically, "DARPA efforts had their greatest success when there was a clearly defined sense of mission and direction in the agency and DOD."63 On December 18, 2017, the Trump Administration released the National Security Strategy, which stated that "the United States will prioritize emerging technologies critical to economic growth and security, such as data science, encryption, autonomous technologies, gene editing, new materials, nanotechnology, advanced computing technologies, and artificial intelligence."64 Currently, it is unclear how DOD will implement this strategic vision across its R&D organizations, including DARPA. Some of the questions posed by IDA in its 1991 report on the future of DARPA still hold today and may be considered by the USD R&E, DARPA, and Congress, including the following:

- What military needs and threats should DARPA's work be focused on?

- What technologies have the potential to make the largest impact in the future?

- How should DARPA interact with the commercial sector and civilian technologies?

- How does DARPA determine the scale and scope of its investment in a given area?

- How does DARPA appropriately balance investment risk and the pursuit of ambitious, potentially high-payoff programs?65

A 2003 report by IDA stated that "DARPA's success depends not only on strong support from OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense], but also on clear guidance from it on strategic needs."66

For more information on the USD R&E see CRS In Focus IF10834, Defense Primer: Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, by Marcy E. Gallo.

Integration of Ethical, Social, and Legal Considerations

Developments in R&D and technology can raise ethical, legal, and societal (ELS) concerns. For example, some groups have expressed concern about the impact artificial intelligence and neurotechnologies could have on privacy, consent, and an individual's identity and agency (i.e., a person's bodily and mental integrity and their ability to choose their own actions).67 The application of these technologies in a military context has the potential to further elevate ELS concerns. For example, how would a neurotechnology that enhances a soldier's senses, stamina, or dexterity affect the ability of an individual to integrate into civilian life upon completion of their service?

In 2013, DARPA initiated a number of neurotechnology programs as part of the Obama Administration's Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative, including R&D on implantable brain-computer interfaces that could restore neural and behavioral function or improve training and performance.68 The Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues recommended that institutions supporting neuroscience research integrate ethical considerations early on and explicitly throughout a research endeavor. DARPA addressed the integration of ethical considerations into its work by requiring neuroscience research program managers to engage an independent Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications panel at the inception of an R&D project.69 DARPA is also planning to host a national ethics workshop.70 However, some critics assert that DARPA does not adequately examine the moral and ethical implications of the research it supports.71 See the box below, "DARPA's Insect Allies Program: Some Scientists and Lawyers Express Concern," for an illustrative example.

|

DARPA's Insect Allies Program: Some Scientists and Lawyers Express Concern On October 5, 2018, a group of scientists and lawyers published a commentary in Science expressing concern over a DARPA funded program known as "Insect Allies." The Insect Allies program is supporting the development of a system that will rapidly modify the traits of plants through the use of insects and plant viruses as a means of protecting the United States crop supply from natural and engineered threats. In the commentary the group states: "In the context of the stated aims of the DARPA program, it is our opinion that the knowledge to be gained from this program appears very limited in its capacity to enhance U.S. agriculture or respond to national emergencies (in either the short or long term). Furthermore, there has been an absence of adequate discussion regarding the major practical and regulatory impediments toward realizing the projected agricultural benefits. As a result, the program may be widely perceived as an effort to develop biological agents for hostile purposes and their means of delivery, which—if true—would constitute a breach of the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)."72 The authors further noted: "It is not our contention that the Insect Allies program is ill-conceived simply because it is a military-funded program. Nor would we accept the assertion that the program is less problematic because it has been somewhat transparently initiated with academics. In our view, the program is primarily a bad idea because obvious simplifications of the work plan with already-existing technology can generate predictable and fast acting weapons, along with their means of delivery, capable of threatening virtually any crop species."73 According to DARPA, "DARPA created Insect Allies to provide new capabilities to protect the United States, specifically the ability to respond rapidly to threats to the food supply. A wide range of threats may jeopardize food security, including intentional attack by an adversary, natural pathogens, and pests, as well as by environmental phenomena such as drought and flooding. Insect Allies aims to develop scalable, readily deployable, and generalizable countermeasures against potential natural and engineered threats to mature crops. The program is devising technologies to engineer and deliver these targeted therapies on relevant timescales—that is, within a single growing season…. For Insect Allies, we scheduled a four-year program of research that concludes with demonstrations inside large, biosecure greenhouses. At no point in the program is DARPA funding open release of Insect Allies systems. Regulatory approval has been a part of the program since its inception as it would be necessary for any eventual realization of the technology."74 |

According to a 2014 report by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS)

knowledge regarding ethical, legal, and societal issues associated with R&D for technology intended for military purposes is not nearly as well developed as that for the sciences (especially the life sciences) in the civilian sector more generally.75

In its 2014 report the NAS recommended the development and deployment of five specific processes to ensure the consideration of ELS issues in an agency's R&D portfolio. These include (1) initial screening of proposed R&D projects, (2) review of proposals that raise ELS concerns, (3) monitoring of R&D projects for the emergence of ELS issues and making midcourse corrections when necessary, (4) engaging with various segments of the pubic as needed, and (5) periodically reviewing the ELS-related processes in an agency.76

According to DARPA officials, the agency has implemented a strategy—informed by the 2014 NAS report—for addressing ELS concerns early on (during the program formulation stage) and throughout the lifespan of a program. Additionally, according to DARPA, the Director conducted a review of the agency's ELS strategy and its implementation in partnership with the Biological Technologies Office and three external ELS experts in the summer of 2017. DARPA asserts that the implementation of the strategy has been effective, based in part on the "positive feedback" the agency has received from the ELS community.77 Congress may consider conducting oversight on the processes and mechanisms used by DARPA to integrate ethical, legal, and societal considerations into its R&D portfolio.