Introduction

Rules of origin (ROO), the methodology used to determine the country of origin of U.S. imports, are central components of U.S. trade policy. Such rules can be very straightforward when all of the parts of a product are manufactured and assembled primarily in one country.1 However, when component parts of a finished product originate in many countries—as is often the case in global industries such as autos and electronics—determining origin can be a complex, sometimes subjective, and time-consuming process.

Determining a product's country of origin can have significant implications for an imported product's treatment with respect to U.S. trade programs and other government policies. For example, the United States restricts imports from certain countries, including Cuba, Iran, and North Korea, as part of larger foreign policy considerations. U.S. trade policy also seeks to promote economic growth in developing countries by offering trade preference programs, including the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), and the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). Such policies require accurate country of origin determinations to ensure that the benefits of the preferential tariff treatment are received and program goals are met.

Certain key characteristics of contemporary globalized manufacturing may also prove challenging to the ROO process and implementation. These characteristics include the growing complexity of global value chains and, consequently, the increasing demand for fast and efficient movement of intermediate goods across borders to assure competitive prices and profitability.2 Some observers assert the combined effects of these characteristics have created a globalized manufacturing environment that is sufficiently intricate and flexible to make the application of ROO more complex and, at times, potentially misleading.

This report provides a general overview of the implementation of the U.S. ROO system and discusses the advantages and disadvantages of U.S.-implemented ROO schemes. The report concludes with some questions Congress may consider when addressing ROO issues in overall U.S. trade policy or future trade agreements.

Rules of Origin in U.S. Practice

The country of origin of an imported product is defined in U.S. trade laws and customs regulations as the country of manufacture, production, or growth of any article of foreign origin entering the customs territory of the United States.3 There are two types of rules of origin (ROO):

- Non-preferential ROO are used to determine the origin of goods imported from countries with which the United States has most-favored-nation (MFN) status;4 they are the principal regulatory tools for accurate assessment of tariffs on imports, addressing country of origin labeling issues, qualifying goods for government procurement, and enforcing trade remedy actions and trade sanctions.

- Preferential ROO are used to determine the eligibility of imported goods from U.S. free trade agreement (FTA) partners and certain developing countries to receive duty-free benefits under U.S. trade preference programs (e.g., the Generalized System of Preferences and the African Growth and Opportunity Act), and other special import programs (e.g., goods entering from U.S. territories). Preferential ROO schemes vary from agreement to agreement and preference to preference.

No specific U.S. trade law provides an overall definition of "rules of origin" or "country of origin." Instead, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—the agency primarily responsible for determining country of origin (as it is for enforcing tariffs and other laws that apply to imported products)—relies on a body of court decisions, CBP regulations, and agency interpretations to determine origin of an imported product if the matter is in doubt.5

Although CBP is the primary enforcement agency for U.S. trade laws, the Customs Modernization Act (Title VI of P.L. 103-182) actually shifted much of the responsibility for complying with customs laws and regulations from CBP to the importer of record.6 This means that the importer must understand customs procedures (including, for example, the applicability of a preferential ROO scheme to his or her product and country of origin), and apply "reasonable care" to enter, properly classify, and determine the value of merchandise so CBP can properly assess duties, collect accurate statistics, and determine whether all other applicable legal requirements have been met.7 In cases where importers are not sure about the origin of a product, they may seek advance rulings from CBP in order to ensure compliance with U.S. laws, and possibly to accelerate the import process.8

International Commitments

U.S. laws and regulations on rules of origin are designed to conform to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Rules of Origin, in which WTO members agreed not to use ROO to pursue trade policy objectives in a manner that would disrupt trade, and to apply them in a consistent, uniform, impartial, and reasonable manner.9 The agreement also allows each WTO member to determine its own ROO regime.10 All WTO members are required to provide the Secretariat its non-preferential ROO. They have also agreed to notify other members about preferential ROO, including a listing of the preferential arrangements that they implement, along with all applicable administrative decisions and rulings.1112

The WTO Agreement on Rules of Origin established a Harmonization Work Programme (HWP) in an effort to develop uniform, cooperative, and coherent non-preferential rules of origin to be used by all WTO members.13 Development is overseen by the WTO's Committee on Rules of Origin (CRO) and the World Custom Organization's Technical Committee on Rules of Origin (TCRO). The ongoing HWP issued a first draft of a consolidated negotiating text in 1998, and a technical review completed in 1999. These efforts secured a general agreement on an overall design for harmonized rules of origin, including definitions, general rules, and two appendices (one on definitions of wholly obtained goods and one on product-specific rules of origin).14 According to the United States Trade Representative (USTR), work on HWP was suspended in 2007 because of disagreement on a number of fundamental issues such as: product specific rules, scope of "prospective obligation to apply the harmonized non-preferential ROO equally for all purposes," and concern among Members that final HWP negotiations would not meet objectives in the ROO Agreement. 15 The USTR stated that the development of the HWP will continue through informal consultations in 2019.16 Nonetheless, about 40 WTO members, including the United States, currently apply national rules of origin for non-preferential purposes along WTO guidelines.17

While the WTO has no plans to develop an equivalent of the HWP for preferential rules of origin, the 2013 Bali Ministerial Conference established guidelines for non-reciprocal preferential rules of origin in an effort to ensure the rules set by preference-granting members, including the United States, are as transparent, simple, and objective as possible. The 2015 Nairobi Ministerial Conference builds on certain guidelines set previously in Bali. The CRO conducts annual review on the development of preferential ROO in accordance with the guidelines.

Non-preferential Rules of Origin

As a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the United States must grant most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment to the products of other WTO member countries with respect to tariffs and other trade-related measures.1819 Non-preferential ROO ensure that imports from U.S. MFN trading partners receive the proper tariff treatment. Non-preferential ROO are also important for country of origin labeling, government procurement, enforcement of trade remedy actions, compilation of trade statistics, supply-chain security issues, and other laws.20

Non-preferential ROO Criteria

Under non-preferential rules of origin, two major criteria apply. First, goods that are wholly the growth, product, or manufacture of one particular country are attributed to that country. This is known as the wholly obtained principle.

Second, if an imported product consists of components from more than one country, a principle known as substantial transformation is used to determine origin. In most cases, the origin of the good is determined to be the last place in which it was substantially transformed into a new and distinct article of commerce based on a change in name, character, or use.21 Making the determination about what constitutes a change sufficient for a product to be considered substantially transformed is when an origin ruling can prove to be quite complex. When determining origin, CBP takes into account one or more of the following factors:

- the character, name, or use of the article;

- the nature of the article's manufacturing process, as compared to the processes used to make the imported parts, components, or other materials used to make the product;

- the value added by the manufacturing process, including the cost of production, the amount of capital investment, or labor required, compared to the value imparted by other component parts; and

- the essential character is established by the manufacturing process or by the essential character of the imported parts or materials.22

Origin determinations are fact-specific, but CBP acknowledges that there can be considerable uncertainty about what is deemed to be substantial transformation due to the "inherently subjective nature" that may be involved in CBP interpretations of these facts.23

Since 1991, CBP has made several proposals to standardize non-preferential ROO. The last proposal was made in 2008 when CBP recommended expanding the application of NAFTA marking rules to all products imported under non-preferential ROO and for negotiated FTAs that use the substantial transformation test to determine origin.24 CBP stated that the objectivity and transparency of the rules resulted in determinations that are more predictable than the case-by-case adjudication method.25 Many associations and businesses voiced general opposition to the proposed rule because they said the proposal could substantially increase costs of entry, place undue burdens on members of the trading community (especially on small businesses), and increase the complexity of the importing process. Others commented on the difficulty of applying these NAFTA marking rules to particular products such as computer software or pharmaceuticals.26

In September 2011, CBP issued a final rule making the NAFTA marking rules applicable to some products subject to non-preferential ROO, namely pipe fittings and flanges, greeting cards, glass optical fiber, rice preparations, and some textile and apparel products. CBP officials also announced that they did not adopt as a final rule the "portion of the notice that proposed amendments to the CBP regulations to establish uniform rules governing CBP determinations of the country of origin of imported merchandise."27

Preferential Rules of Origin

Preferential rules of origin are used to verify that products are eligible for duty-free status under U.S. trade preference programs, such as the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), or free trade agreements (FTAs), such as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the U.S- South Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA).28

As with non-preferential ROO, if goods are "wholly the product" of a beneficiary of preference program or free trade agreement, establishing origin is usually fairly straightforward. However, if a good was not entirely grown or manufactured in the targeted country or region, rules of origin specific to the trade preference or FTA apply. Preferential ROO vary from agreement to agreement and preference to preference. Most U.S. FTAs use three methods, or a combination thereof, to determine where products "originate" and thus actually qualify for the benefits of the agreement.

"Tariff Shift" Test

In some agreements, a tariff shift method, or change in the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) tariff classification (as a result of production occurring entirely in one or more of the parties), may be used to determine whether or not the product qualifies for benefits. The USMCA is one example in which this methodology is used.29 This methodology is favored by U.S. customs officials because they say that it provides an objective method for describing exactly the kind of substantial transformation that must occur to determine the origin of a product.30

|

Examples of Tariff Shift Rules of Origin for Textiles and Apparel Products Fiber Forward A change to heading 5101 through 5105 [wool fibers] from any other chapter. Wool fiber must be produced in the territory of the trading partners, and no foreign fibers may be used. Yarn Forward A change to heading 5801 through 5811 [special woven fabrics] from any other Chapter, except from headings 5106 through 5113 [wool yarn and fabric], 5204 through 5212 [cotton yarn and fabric], 5308 [yarn of other vegetable fibers], or 5311 [woven fabrics of other vegetable textile fibers], Chapter 54 [man-made filaments and fabrics], or heading 5508 through 5516 [yarn and fabric of synthetic staple fibers]. Yarn and fabric must be produced in the territory of the trading partners, but foreign fibers may be used. Fabric Forward A change to heading 5901[coated textile fabrics] from any other chapter, except from heading 5111 through 5113 [woven wool fabrics], 5208 through 5212 [woven cotton fabrics], 5307 through 5308 [woven fabrics of other vegetable yarns (coir yarn, paper yarn, etc], 5407 through 5408 [woven man-made fiber filament fabrics], or 5512 through 5516 [woven man-made staple fabrics]. Fabric must be produced in the territory of the trading partners, but foreign yarn and fibers may be used. Source: Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States and U. S. Customs and Border Protection, "Textile and Apparel Preference Rules." |

For example, the "yarn forward" principle, related to preferential ROO for certain textile and apparel products, is a type of tariff shift test that requires textile and apparel products to originate in an FTA country from the yarn stage forward (fibers may come from anywhere). Notably, the specific term, "yarn forward" never actually appears in an FTA. Instead, the tariff shift presented in the ROO indicates the amount of processing required (substantial transformation) in an FTA country in order to confer originating status. Specific ROO for certain products, including textiles and apparel, generally appear in an annex to the FTA, and list various categories of goods by reference to their Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) tariff lines.31

Technical Test

With certain products, a technical test may be used that requires specific processing operations occur in the originating country.32 Sometimes known as a critical process criterion, this test mandates that certain production or sourcing processes be performed that may (positive test) or may not (negative test) confer originating status.33 For example, in the U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS), certain chemicals require that manufacturing processes such as purification, chemical reaction, controlled mixing and blending, changes in particle size, or other technical tests such as these, must take place in one or both FTA parties in order to confer origin.34

|

Examples of Technical Tests for Products of the Chemical or Allied Industries (HTS Chapters 28-38) Rule 1: Chemical Reaction Origin: A good in Chapters 28-38, except goods under heading 28.23, that results from a chemical reaction in the territory of one or both of the Parties shall be treated as an originating good. Note: For purposes of this section, a "chemical reaction" is a process (including a biochemical process) that results in a molecule with a new structure by breaking intramolecular bonds and by forming new intramolecular bonds, or by altering the spatial arrangement of atoms in a molecule. The following are not considered to be chemical reactions for the purposes of determining whether a good is an originating good: (a) dissolution in water or in another solvent; (b) the elimination of solvents including solvent water; or, (c) The addition or elimination of water of crystallization. *** Rule 3: A good in Chapters 30, 31, or 33, shall be treated as an originating good if the deliberate and controlled modification in particle size of the good, including micronizing by dissolving a polymer and subsequent precipitation, other than by merely crushing or pressing, resulting in a good having a defined particle size, defined particle size distribution, or defined surface area, which is relevant to the purposes of the resulting good and having different essential physical or chemical characteristics from the input materials, occurs in the territory of both of the Parties. Source: United States - South Korea Free Trade Agreement, Annex 6-A, Specific Rules of Origin. |

Local or Regional Value Content Test

A local content or regional value content (RVC) test is required of many products imported into the United States under FTAs or preference programs. A local content test stipulates that to receive the tariff benefit, a product must contain a minimum percentage of domestic value-added determined by the origin of physical components or parts and labor and manufacturing processes that originated in the FTA partner or beneficiary developing country.35

The amount of local content required may vary among U.S. free trade agreements and preferences, and differs among product categories within an arrangement. In some cases, the local content requirement may be fulfilled on a regional basis. For example, in order for a product to qualify for duty-free treatment under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), the cost or value of the materials produced in that developing country (or produced in one or more members of an association of countries treated as one country under GSP), and the direct cost of the processing operations performed in that beneficiary country (or association of countries as described above), must be at least 35% of the appraised value of the product.36

The previous example illustrates "cumulation," or the way that ROO may allow for combining value-added inputs from a region or group of countries into a manufactured product that qualifies as an import under the terms of a regional FTAs or regionally-targeted preference program. Cumulation may help accomplish another major policy objective of regional trade programs: the stimulation of regional integration through deepened intra-regional trade.37 In some preferential arrangements, a certain percentage of U.S. content may count toward meeting the regional content test.

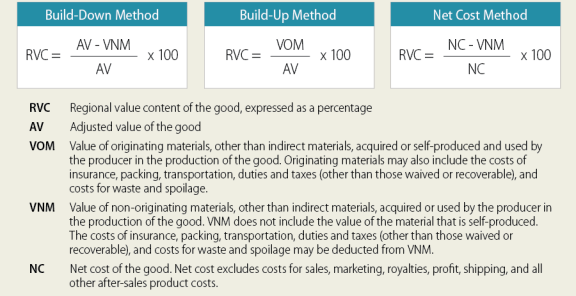

In U.S. FTAs, three alternative methods are often used to calculate RVC, which is often used to determine the origin of assembled products such as autos and auto parts (Figure 1). Manufacturers and importers are sometimes given more than one ROO option to calculate the RVC because one method of calculation may be more beneficial than others for particular companies or industries. Three common types of RVC calculations are:

- Build-down method: calculates the RVC by subtracting the value of the non-originating merchandise (VNM) from the adjusted value (AV) of the finished product. The adjusted value includes all costs, profit, general expenses, parts and materials, labor, shipping, marketing, and packing. If the RVC (expressed as a percentage) of the product value is equal to or greater than the minimum percentage specified in the ROO, the product qualifies.

- Build-up method: calculates RVC by adding together the value of all of the regional inputs (e.g., costs, general expenses, parts, materials, labor, shipping, marketing, and packing). If the RVC (expressed as a percentage) of the product is equal to or greater than the minimum percentage specified in the ROO, the product qualifies.

- Net cost method: captures only the costs involved in manufacturing, including factory labor, materials, and direct overhead. Other costs, such as sales promotion, marketing, royalties, and profit, are excluded from the calculation. The use of a small, easily identifiable set of input costs is thought to make the net cost method easier to use in calculating RVC.38

|

|

Source: Various U.S. FTA rules of origin chapters. |

Rules of Origin Issues

Due to their obscure and technical nature, rules of origin frameworks are generally not in the forefront of the debates on trade liberalization or globalization. Nevertheless, the role of ROOs (both preferential and non-preferential) is central to the international trading system and trade negotiations.

Preferential rules of origin are arguably essential to ensure that the benefits of an FTA are provided to those countries that have negotiated and entered into the agreement.39 Without preferential ROO, it would be possible for imports from non-FTA countries to enter the FTA partner with the lowest external tariff, and then sell the good throughout the region under the FTA rate. This could force a convergence of external tariffs and possibly a competitive devaluation of external tariffs in the region.40 For similar reasons, ROO are also considered important when providing unilateral trade preferences to ensure that only goods from eligible countries receive the benefits.

Some policy observers assert that the worldwide proliferation of trade agreements creates inefficiencies in the trading system because there are so many complex ROO frameworks. Others express concerns that current U.S. systems for determining country of origin may run counter to the goal of U.S. FTAs in encouraging international trade. Still other observers say that negotiation of specific ROO allows countries to shield import-sensitive segments of industries by instituting ROO that either do not include a particular product, or make the ROO so difficult that the product does not qualify. Some observers assert that ROO interpretation is complex and subjective. Other experts maintain that, in a global manufacturing environment, there should be other means of determining country of origin. Finally, some experts wonder if ROO definitions could produce results that could be counter to certain policy objectives.

New Characteristics in Rules of Origin

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaces NAFTA, introduced additional requirements for determining country of origin that have not existed in prior U.S. FTAs. In addition to increasing the regional value content requirement from 60% to 62.5% in NAFTA to 70% to 75% in USMCA, the agreement introduced requirements for steel and aluminum content, and labor value content, which requires 405 to 45% of vehicles and parts to be produced by workers earning at least $16 per hour.41 Some trade policy analysts predict the new requirements may increase economic inefficiency as it increases administrative costs and shifts existing supply chains.42 The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that higher compliance costs may result in increased tariff revenue for the U.S. government as manufacturers may choose to pay the MFN rate instead.43

In light of the fact that these requirements are new to a U.S. FTA, some manufacturers have raised questions as to how these rules will be applied and enforced. The relevant agencies, including CBP, will likely need to write new regulations to address these questions. Some in the trade community have also wondered whether the labor value content requirement in particular will change preferential ROO and origin determinations in future U.S. FTAs.

Proliferation of Preferential ROO

Some economists argue that the proliferation of bilateral and regional trade agreements—each with its own preferential ROO scheme—adds new complexities for importers and manufacturers; thus potentially inserting economic inefficiencies into the international trading system. Since preferential rules of origin are specific to each free trade agreement or preference program, assembling the proper documentation can be a complex and costly process. Some companies reported having to manage multiple sets of preferential ROO, which requires "significant efforts to manage the data, documentation and analysis" needed to meet various ROO requirements.44 Some U.S. firms have stated that the administrative costs associated with navigating the increasingly complex patchwork of regulations involved in establishing origin can outweigh the benefits of FTAs.45 The key challenges of constructing ROO in preferential trading relationships are twofold: finding the balance between the effectiveness and the efficiency of ROO, and simplifying and making ROO more transparent.

Some economists also assert that the worldwide proliferation of FTAs has led to an inefficient "spaghetti bowl" approach to trade policy with individual ROO requirements.46 It may also be a barrier to future potential efforts by WTO members to negotiate and/or revise multilateral rules governing preferential ROOs.47

The lack of transparency of preferential ROO (and their apparent use as instruments of protectionism) is also a matter of concern for some critics. An often-repeated example of this is the "triple-transformation rule" for apparel products within NAFTA, which also applies under USMCA. This rule requires that the raw materials (fiber), cloth, and the garment itself be processed within the FTA region to meet origin requirements.48 As a result, some economists argue that such restrictive rules may cause businesses to make inefficient sourcing decisions, particularly in industries with more restrictions.49

Importers always have the option of entering products under MFN rates (in which case non-preferential rules of origin would apply) if they determine this is the most cost-effective method of entry. For example, a study of trade flows under NAFTA ROO illustrated that when the MFN tariff on a product is equal or more favorable than the NAFTA tariff, importers will typically choose to import under the MFN rate to avoid the additional compliance costs.50 This may become more common under the USMCA; some domestic auto manufacturers have expressed concerns regarding the complexity and potential costs to the industry, such as incurring higher administrative expenses and shifting supply chains to meet ROO requirements.51 Additionally, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that some manufacturers will import under MFN rates and forgo the duty-free treatment under the new agreement due to higher compliance costs.52 Importers may, in some cases, decide not to enter goods under an FTA, but the availability of such preferences gives them greater flexibility to purchase and import products in the most cost-effective manner available. The fact remains, however, that the utilization of trade preferences under preferential rules of origin is sometimes costly, and may also inhibit the use of preferences.

Influence of Domestic Stakeholders

Because some preferential ROO in FTAs are negotiated product-by-product and industry-by-industry, some economists assert that the approach tends to lead to rules that are restrictive and complex.53 Some domestic industries push for specific ROO to restrict imports while expanding exports within a free trade area.54 Others argue that product-by-product rules leave little room for interpretation and receiving input from domestic industries is the best approach to negotiating ROO. This approach may also soften the opposition from import-competing groups, thus enhancing the political feasibility of subsequent FTA implementation (after congressional approval).55

Some studies indicate that more restrictive rules of origin, such as higher local content requirements, may encourage producers of finished goods in an FTA region to shift from lower-cost suppliers of intermediate goods outside an FTA to higher-cost suppliers within an FTA region (often U.S. suppliers) to qualify for more favorable FTA tariff benefits. Thus, more restrictive ROO can be used to provide "protection" to these regional suppliers and maintain existing protection against outsiders, to the extent that they provide sufficient incentive for FTA producers to buy more inputs inside the region.56 Therefore, more restrictive local or regional content requirements can spread the benefits of an FTA to manufacturers of intermediate products in the region.

The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) may open a period for public comments to get negotiating objectives for potential FTAs. This is one way domestic stakeholders may influence preferential ROO. For example, in 2018, USTR asked for public comments to develop negotiating objectives for the then-proposed U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement.57 Examples of submitted comments related to rules of origin include:58

- The Steel Manufacturers Association supported higher RVC and steel and aluminum requirements for motor vehicles that is seen in USMCA.

- The American Iron and Steel Institute supported strong ROO to ensure steel manufactured from third-countries do not receive preferential benefits.

- The American Apparel and Footwear Association supported rules of origin for the industry but advocate for cumulation provisions with joint FTA partners.

ROO Interpretation

Country of origin rulings can be complex, especially when questions on what processes or procedures are sufficient for a product to be "substantially transformed" come into play. A major reason for this complexity is that, especially in situations involving non-preferential (MFN) origin rules, officials must often make these determinations on a case-by-case basis. Some in the global trade community have criticized CBP and other custom authorities because they assert that some of these determinations are subjective, inconsistent, and lack transparency. In a 2018 survey by consulting firm Ernst & Young, a majority of trade professionals indicated origin rulings are inconsistent across customs authorities and cited a need for ROO harmonization.59

In the United States, CBP tries to promote transparency by allowing importers to request a binding ruling from the CBP Office of Regulations and Rulings in advance of importing the good. CBP also provides a Customs Rulings Online Search System (CROSS) that importers can search for a ruling on a product similar to theirs for additional guidance.60

Under the WTO Agreement on Trade Facilitation (TFA), which went into effect in 2017, all WTO members agreed to issue similar advance rulings on ROO and other trade matters "in a reasonable time-bound manner," and to "promptly publish … laws, regulations, and administrative rulings" of general application relating to rules of origin.61 The rationale is that increased transparency of ROO interpretation worldwide will provide greater assurance for exporters from the United States and other countries that the origin of their products will be handled in a consistent manner. CBP complies with the TFA by issuing binding advance rulings on origin.

Global Manufacturing and Rules of Origin

In an international trading environment in which a final good is made with parts sourced from multiple countries and may be assembled anywhere in the world, some observers suggest that single-country origin determinations are misleading.

Since World War II, new technology in manufacturing, communications, and transportation made it possible for companies to source labor, parts, and materials from multiple countries in a cost-efficient method. As a result, an increasing variety of a product's parts and components come from many different nations, and, especially with more complex merchandise, manufacture and assembly may also be conducted in several different countries.62

World trade and production are increasingly structured around "global value chains" (GVCs), defined as "the full range of activities that firms and workers do to bring a product from its conception to its end use and beyond."63 A value chain typically includes design, production, marketing, distribution, support, and delivery to the final consumer.64 Beyond increased competition among manufacturers, there has also been a restructuring of the overall manufacturing process toward subcontracting or "outsourcing" production to globally-integrated contract manufacturers. "Full-package" production companies in China and other countries are able to link specialized producers in many countries, creating specialized networks that manufacture all components and assemble final products. These producers are sufficiently integrated to control all manufacturing, logistics, and final delivery of the end-use products.65

These characteristics of modern manufacturing have significant implications for international trade, including the following:

- The "nationality" of the retailer or brand, the "nationalities" of the specialized producers, and "nationalities" of the ultimate manufacturers or assemblers of a product are often different. Most goods (and increasingly services) are "made in the world";

- Countries increasingly specialize in tasks and business functions, competing for economic roles within the value chain, rather than in the production of end-use goods;66

- Although major U.S. manufacturing firms are actively involved in the overall management of their GVCs, some industries, such as retailers, may know less about where or how a product was made;

- Frequently, a relatively small percentage of the product's total value was created in the attributed country of origin; and

- GVCs exist across many industry sectors, including electronics, motor vehicles, chemical products, agriculture and food products, fashion, and business and financial services.

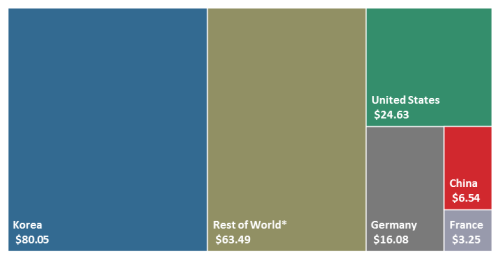

The Case of the Apple iPhone

A 2012 analysis of Apple's iPhone 4 manufacturing process provides a case study of how electronics and other products are produced in the global manufacturing environment. Most of Apple's iPhones are assembled in China by Foxconn,67 a Taiwanese contract manufacturer that handles all sourcing and logistics. The gross export value of the product (factory gate price) was $194.04, but the value-added of assembly costs in China was $6.54 (around 3% of the total value).68 Even though China's contribution to the iPhone's value was relatively small at the time of the 2012 analysis, the product is considered a product of China according to CBP regulations, because the product was last "substantially transformed" in China (Figure 2).69

|

|

Source: Gereffi and Lee, "Why the World Suddenly Cares about Global Supply Chains," 2012. Notes: *Includes $0.70 Japanese inputs identified in data source; most recent data available. |

Effects on Rules of Origin

As described above, in the increasingly global manufacturing environment, the assembly point of the manufactured product and of its individual components may differ. These rapidly accelerating changes in the manufacturing process can lead to additional complexities in ROO determinations because officials must ascribe origin to a single country for import purposes.

In turn, these complexities may lead to apparent inconsistencies. For example, in some cases, CBP officials may decide that the assembly process (including the value-added by labor costs) is sufficient to confer origin, as it is the "last place of substantial transformation."70 In other cases, officials have determined that the final assembly process and labor costs incurred are actually not sufficient to confer this essential character.71

However, CBP has the legal flexibility to be able to consider "the totality of the circumstances and makes such decisions on a case-by-case basis." As a consequence, the agency is able to fully consider the extent and technical nature of the processing that occurs in each country, thus taking into account the "resources expended on product design and development, extent and nature of post-assembly inspection procedures, and worker skill required during the actual manufacturing process" when making country of origin determinations.72 Therefore, the flexibility to analyze individual components and manufacturing processes could lead to more precise country of origin determinations, despite the complex nature of global manufacturing.

Conclusion and Questions for Congress

Rules of origin are central components of trade policy. Preferential rules of origin are especially important for ensuring that only goods qualified to receive benefits under an FTA or preference receive those benefits. ROO may also be constructed to ensure that import-competing U.S. producers are not adversely affected by an FTA, thus possibly assuring a degree of public support for the measure. Non-preferential rules are essential for making sure that goods coming from countries that enjoy MFN status with the United States are assessed the proper tariffs, and are also key to supporting other U.S. trade laws, such as country of origin labeling.

Non-preferential rules are essential for making sure that goods coming from countries with MFN status with the United States are assessed the proper tariffs, and are also key to supporting other U.S. trade laws, such as country of origin labeling. However, some importers criticize CBP's country of origin determination process for an alleged lack of transparency and predictability because its decisions are often made on a case-by-case basis. The last time CBP issued new regulation to standardize the process was in 2011. The Harmonization Work Programme (HWP), which the United States has agreed to, may lead to international standardization of non-preferential ROO, but formal negotiations stalled in 2007; informal consultations is ongoing as of 2019.

The increase in the number of bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs), each with its own set of preferential rules of origin, have created a spaghetti bowl effect. With the growing role that global value chains play in international trade, some economists have stated that the proliferation of preferential ROO are protectionist, and create inefficiency and complexity. The steel content and labor value content requirements under the USMCA are new ROO characteristics that add to the complexity. Stricter preferential ROO often lead to higher compliance costs and lower utilization of preferential benefits.

As Congress has the constitutional authority to regulate foreign trade, it may consider the following questions:

- Should the process for determining country of origin for non-preferential U.S. imports be standardized further to address the transparency and consistency issues?

- Should the United States take a leading role to push for the completion of the HWP?

- Should preferential ROO in current and future U.S. FTAs be liberalized to ease compliance costs for importers?

Will future U.S. FTA negotiations be influenced by new characteristics of ROO as seen under the USMCA?