Border officials are dually responsible for facilitating the lawful flow of people and goods, while at the same time preventing unauthorized entries and stopping illicit drugs and other contraband from entering the United States. As such, policy discussions around border security often involve questions about how illicit drugs flow into the country.1 These include questions about the smugglers, types and quantities of illicit drugs crossing U.S. borders, primary entry points, and methods by which drugs are smuggled. Further, these discussions often center on the shared U.S.-Mexico border, as it is a major conduit through which illicit drugs flow into the United States.2

Mexican transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) are a dominant influence in the U.S. illicit drug market and "remain the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States; no other groups are currently positioned to challenge them."3 They produce and transport foreign-sourced drugs into the United States and control lucrative smuggling corridors along the Southwest border. Drug intelligence4 and seizure data5 provide some insight into drug smuggling into the country. Generally, intelligence suggests that more foreign-produced cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl flow into the country through official ports of entry (POEs) than between the ports. Seizure data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) follows this pattern as well. Conversely, more foreign-produced marijuana has historically been believed to flow into the country between the ports rather than through them.6 However, CBP seizure data indicate that, like cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl, more marijuana was seized at POEs than between them in FY2019.7

While indicators suggest that large amounts of illicit drugs are flowing through POEs and that drug seizures are more concentrated at the ports, it is the flows between them that have been a primary topic of recent policy discussions around border security.8 This report focuses on the smuggling of illicit drugs between POEs. It briefly describes how these drugs are smuggled between the ports and then illuminates the discussion of how border barriers may shift or disrupt smuggling methods and routes.9

Illicit Drug Smuggling Between Ports of Entry

Notably, there are no data that capture the total quantity of foreign-produced illicit drugs smuggled into the United States at or between POEs; drugs successfully smuggled into the country have evaded seizure by border officials and are generally not quantifiable. In lieu of these data, officials, policymakers, and analysts sometimes rely on certain drug seizure data to help understand how and where illicit drugs are crossing U.S. borders.

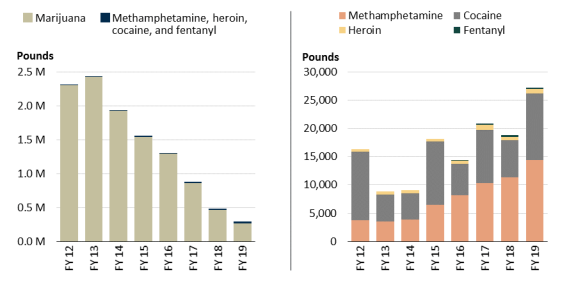

By weight, marijuana continues to be the illicit drug most-seized by border officials both at and between POEs, though total annual marijuana seizures have declined both at and between the ports in recent years.10 Historically, border officials have reported seizing more marijuana between POEs than at them.11 However, more marijuana, by weight, was seized at the ports than between them in FY2019. Of the 556,351 pounds of marijuana seized by CBP in that year, 289,529 pounds (52%) were seized at the ports, and 266,822 pounds (48%) were seized by the Border Patrol between the ports.12

While marijuana remains the primary drug seized by the Border Patrol between POEs, the annual quantity seized, in pounds, has declined since FY2013 (see Figure 1). Conversely, the amount of methamphetamine seized by the Border Patrol has increased annually since FY2013, and seizures of cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl have fluctuated.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. Data from CBP enforcement statistics, available online at https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics. As of the date of this report, only FY2014–FY2019 full-year seizure data are available at the website. FY2012 and FY2013 data were previously available at the same website, as recently as January 2019. |

Smuggling Methods

Smugglers employ a variety of methods to move illicit drugs into the United States between POEs, through land, aerial, and subterranean routes.13 These methods include the use of underground tunnels, ultralight aircraft and unmanned aerial systems (UASs), maritime vessels, and backpackers, or "mules."14 As noted, the smuggling between the official POEs has received heightened attention in policy discussions about border security. Specifically, there has been some debate about how physical barriers along the Southwest border between the POEs may deter or alter the smuggling of foreign-produced, illicit drugs into the country.

Border Barriers and Smuggling

Since the early 1990s, there have been efforts to build barriers along the Southwest border, in part, to deter the unauthorized entry of migrants and smugglers.15 More recently, in debates about physical barriers along the Southwest border, the prevention of drug smuggling and trafficking has been cited as a key goal and a reason to expand and enhance the physical barriers. For instance, the January 25, 2017, Executive Order 13767 stated that it is executive branch policy to "secure the southern border of the United States through the immediate construction of a physical wall on the southern border, monitored and supported by adequate personnel so as to prevent illegal immigration, drug and human trafficking, and acts of terrorism."16 Analysts suggest that smugglers may respond (if they have not already, given the hundreds of miles of border barriers already in place)17 by moving contraband under, over, or through the barriers, as well as around them—including by changing their concealment techniques to move illicit drugs more effectively through POEs.18

Under Barriers

Mexican traffickers utilize subterranean, cross-border tunnels to smuggle illicit drugs—primarily marijuana—from Mexico into the United States.19 Since the first one was discovered in 1990, tunnel construction has increased in sophistication.20 Tunnels may include amenities such as ventilation, electricity, elevators, and railways, and tunnel architects may take advantage of existing infrastructure such as drainage systems. For instance, in August 2019 officials discovered a sophisticated drug smuggling tunnel running more than 4,300 feet in length (over three-quarters of a mile) and an average of 70 feet below the surface from Tijuana, Mexico, to Otay Mesa, CA—the longest smuggling tunnel discovered to date.21

CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have primary responsibility for investigating and interdicting subterranean smuggling. CBP has invested in technology and services to help close certain capability gaps such as predicting potential tunnel locations as well as detecting and confirming existing tunnels—including their trajectories—and tunneling activities.22 Reportedly, among the challenges in detecting tunnels is the variance in types of soil along the Southwest border, which requires different types of detection sensors.23 ICE, CBP, and other agencies coordinate through initiatives such as the Border Enforcement Security Task Force (BEST) program,24 where they have focused Tunnel Task Forces in various border sectors. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) recommended in 2017 that CBP and ICE further establish standard operating procedures, including best practices applicable to all border sectors, to coordinate their counter-tunnel efforts.25 Policymakers may question whether current agency coordination is sufficient or whether the agencies have implemented or should implement GAO's recommendation.

Over Barriers

Traffickers have moved contraband over border barriers through a variety of mechanisms, from tossing loads by hand and launching bundles from compressed air cannons to driving vehicles on ramps up and over certain types of fencing, as well as employing ultralight aircraft and unmanned aircraft systems (UASs) and drones.26 While ultralights are used to transport bulkier marijuana shipments, "UASs can only convey small multi-kilogram amounts of illicit drugs at a time and are therefore not commonly used, though [officials see] potential for increased growth and use."27 For instance, in August 2017, border agents arrested a smuggler who used a drone to smuggle 13 pounds of methamphetamine over the border fence from Mexico into California.28

Border officials have tested several systems to enhance detection of ultralights and UASs crossing the border.29 Currently, CBP uses a variety of radar technology, including the Tethered Aerostat Radar System.30 These technologies are not, however, focused specifically on detecting illicit drugs being smuggled into the country over barriers; rather, they are more broadly used to help detect unauthorized movement of people and goods. Policymakers may examine technologies acquired and used by border officials, including whether they allow officials to keep pace with the evolving strategies of smugglers moving illicit drugs over the U.S. borders—specifically, over border barriers. In addition, they may examine whether, as GAO has recommended,31 CBP is assessing its performance in interdicting UASs and ultralights against specific performance targets to better evaluate the outcome of using these technologies.

Through Barriers

Various forms of physical barriers exist along the Southwest border, generally intended to prevent the passage of vehicles and pedestrians. Barrier styles and materials include expanded metal, steel mesh, chain link, steel and concrete bollards, and others.32 Smugglers have found ways to defeat them. They have cut holes and driven vehicles through fencing and, in at least one instance, have bribed border officials to provide keys to the fencing and inside knowledge about unpatrolled roads and sensor locations.33 More recently, smugglers have reportedly sawed through steel and concrete bollards on the newly constructed border barrier; "after cutting through the base of a single bollard, smugglers can push the steel out of the way, creating an adult-size gap" through which people and drugs can pass.34

Around Barriers

Some have noted that border barriers may deter some portion of illegal drug smuggling, while an unknown portion will be displaced to areas without fencing. Specifically, along the Southwest border, barriers may shift some portion of smuggling traffic to other areas of the land border between the United States and Mexico as well as to the ocean. Some of these alternate areas may have terrain that acts as some sort of a barrier, presenting different challenges than those from constructed border barriers. These challenges may, in turn, deter or alter drug smuggling. In addition, there have been reports that the newly constructed border barrier in the San Diego border sector has coincided with an increase of maritime smuggling along that coast.35 Smugglers use small open vessels ("pangas"), which can travel at high speeds. They also use recreational boats and small commercial fishing vessels that can be outfitted with hidden compartments to "blend in with legitimate boaters."36

In addition to moving illicit drugs across water or open areas of the land border without manmade barriers, the addition or enhancement of border barriers could lead some smugglers to move their contraband through POEs. The most recent data from CBP indicate that, in pounds, more illicit drugs—specifically marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl—are already being moved through POEs than between them.37 Policymakers may question whether any drug smuggling displaced to the POEs as a result of additional or augmented border barriers is a substantive change.

Border Barriers and Their Influences on Illicit Drug Smuggling Between POEs

A question policymakers may ask is what effect, if any, increased miles or enhanced styles of border barriers may have on drug smuggling between the POEs. Specifically, they may question whether additional border barrier construction will substantially alter drug smugglers' routes, tactics, speed, or abilities to breach these barriers and bring contraband into the country. A comprehensive analysis of this issue is confounded by a number of factors, the most fundamental being that the exact quantity of illicit drugs flowing into the United States is unknown. Without this baseline, analysts, enforcement officials, and policymakers rely on other data, albeit selected or incomplete, to help inform whether or how border barriers may affect illicit drug smuggling.

|

Illicit Drug Flows into the United States38 At the top of the illicit drug supply chain is the total production of illicit drugs around the world—both plant-based (e.g., cocaine, heroin, and marijuana) and synthetic (e.g., methamphetamine and fentanyl). Although some illicit drugs are produced in the United States, many originate elsewhere and are smuggled into the country. For plant-based drugs, a variety of factors affect cultivation as well as surveillance and measurement of crop yields. In addition, not all illicit drug crops may be processed into illicit drugs. For synthetic drugs, the supply chain begins in chemical manufacturing and pharmaceutical facilities. Measuring the stock of these drugs is affected by issues including the availability and inconsistent regulation of precursor chemicals and the proliferation of synthetic analogues, or new psychoactive substances. The next step in the supply chain of illicit drugs produced abroad and destined for the United States is their transit toward and into the country. Of the unknown total amount of illicit drugs produced, some may be consumed in the country of production, some may be destined for the United States, and some may be intended for an alternate market. Of those drugs destined for the United States, some may become degraded or lost in transit, some may be seized by law enforcement or otherwise destroyed or jettisoned by traffickers pursued by enforcement officials, and some reach the U.S. border. Of the total amount of illicit drugs that reach the U.S. border by land, air, or sea, some quantity is known because it was seized by border officials, and an unknown quantity is successfully smuggled into the country. |

Border barriers are only one component of tactical infrastructure employed at the border.39 Infrastructure, in turn, is only one element (along with technology and personnel) of border security. Isolating the potential effects of changes in border barriers from those of other infrastructure investments, as well as from the effects of changes in technology and personnel, is a very difficult task. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has made efforts to estimate the effectiveness of border security on the Southwest border between POEs; however, the department recognizes inevitable shortcomings of these estimates due, in part, to unknown flows of people and goods. Further, its estimates of border security effectiveness do not make precise attributions of effectiveness to personnel, technology, or infrastructure—or even more specifically, the portion of infrastructure that is border barriers.40

There are also factors beyond the immediate personnel, technology, and infrastructure of border security efforts that may affect drug smuggling. These include "the demand and supply for drugs, the type of drug being shipped, terrain and climate conditions, and smuggler counterintelligence functions."41 And, it may be difficult to separate the results of border security efforts from the effects of those external factors on drug smuggling. Moreover, changes in drug smuggling cannot always be directly linked to changes in border security efforts.

Policymakers may continue to question how DHS is identifying and evaluating any potential changes in drug smuggling between the POEs. More specifically, they may examine whether or how DHS is linking observed changes in drug seizure data—sometimes used as one proxy for drug smuggling—to specific border security efforts such as expanded border barriers. They may also consider how any return on investment in border barriers (measured by effects on illicit drug seizures) compares to the relative return from other border security enhancements. Relatedly, policymakers may continue to examine how DHS defines "success" or "effectiveness" of border barriers in deterring or altering drug smuggling. For instance, is an effective barrier one that deters the smuggling of illicit drugs altogether, or might it be one that slows smugglers, changes their routes, or alters their techniques so that border officials have more time, opportunity, or ability to seize the contraband? In addition, policymakers may question whether or how border barriers contribute to gathering intelligence that can be used by the broader drug-control community and whether that potential outcome is a measure of effectiveness.42