Introduction

Since the 1960s, Congress has passed measures to authorize and fund international family planning related activities that give participants access to a broad range of contraceptive methods and services. Such assistance is intended to support broader U.S. international development priorities, as stated in Section 104 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (P.L. 87-195):

The Congress recognizes that poor health conditions and uncontrolled population growth can vitiate otherwise successful development efforts. Large families in developing countries are the result of complex social and economic factors which change relatively slowly among the poor majority least affected by economic progress, as well as the result of a lack of effective birth control. Therefore, effective family planning depends upon economic and social change as well as the delivery of services and is often a matter of political and religious sensitivity. While every country has the right to determine its own policies with respect to population growth, voluntary population planning programs can make a substantial contribution to economic development, higher living standards, and improved health and nutrition.

Section 104 goes on to authorize U.S. assistance to address the impact of population growth on development through family planning activities:

In order to increase the opportunities and motivation for family planning and to reduce the rate of population growth, the President is authorized to furnish assistance, on such terms and conditions as he may determine, for voluntary population planning. In addition to the provision of family planning information and services, including also information and services which relate to and support natural family planning methods, and the conduct of directly relevant demographic research, population planning programs shall emphasize motivation for small families.

According to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the primary federal agency charged with administering development assistance, family planning refers to "services, policies, information, attitudes, practices, and commodities, including contraceptives, that give women, men, couples, and adolescents the ability to avoid unintended pregnancy and choose whether and/or when to have a child."1 Over time, family planning programs evolved beyond a strict focus on contraception to provide information and services on a wide range of issues that adversely affect sexual and reproductive health (e.g., female genital mutilation and cutting (FGM/C), obstetric fistula, and gender based violence (GBV)). This broader scope is reflected in the common categorization of these activities as reproductive health/family planning (RH/FP) assistance. Reproductive health refers to "all matters relating to the reproductive processes, functions, and system at all stages of life."2

The United States is the largest country donor to international FP/RH programs, providing $575 million dollars annually in recent years.3 Although U.S. funding for FP/RH activities has been consistent for years, the programs remain a subject of intense congressional debate. While the law explicitly prohibits the use of funds to provide abortion or involuntary sterilization,4 some Members of Congress continue to express concern that FP/RH may indirectly support such activities as a result of funding fungibility. Other concerns relate to the cultural appropriateness of family planning activities and the relationship between FP/RH and broader global health and development assistance.

This report focuses on the scope and intended impact of U.S. bilateral international family planning programs administered by USAID. It does not comprehensively address related legislative restrictions (although a table listing such restrictions is provided in the Appendix), or discuss aid channeled through multilateral organizations, such as the U.N. Population Fund (UNFPA).5

Family Planning: Key Issues

International FP/RH programs aim to provide women with the information and services needed to make informed decisions regarding their contraceptive options and to ensure healthy reproductive systems and safe pregnancies.6 According to USAID, a key aspect of these programs is family planning, as some 885 million women worldwide would like to avoid or delay pregnancy.7 Of those women, 212.4 million (24%) lack access to FP/RH services.8 Supporters of FP/RH programs assert that access to such services is necessary for safe motherhood. They cite evidence that bearing children too close together, too early, or too late in life can threaten the health of the mother and her baby.9 In addition, lack of access to family planning services can have negative social and economic impacts that undermine broader global development goals. For example, some experts note that improving access to family planning services has been shown to have benefits for children's health, women's empowerment, and sustainable growth and development.10

Critics of international family planning programming have expressed concern that despite existing restrictions, U.S. dollars could be used indirectly to support abortion or involuntary sterilization if implementing partners use U.S. funds for approved services, freeing up funding from other sources to support abortion or involuntary sterilization. 11 Other detractors argue that U.S. foreign assistance for contraceptive provision is an inappropriate imposition on local cultural or religious norms, further asserting that abstinence education is a more effective form of family planning.12 Critics have also questioned the practice of allocating specific resources for FP/RH programs rather than allocating aid to broader women's health programs or for other development priorities that they argue would be a more effective use of U.S. funds.13

Evolution of U.S. Policy and Programs

Since U.S. bilateral FP/RH programs and policies were launched in 1965, they have evolved to reflect changes in global health priorities and emphasize the link between development and gender.14 The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195; as amended) first authorized research on family planning issues, among many other things, and in 1965 Congress authorized USAID to create contraceptive distribution programs through the Office of Population. Initial programs focused on procuring contraceptive supplies for distribution in developing countries.15 At the time, the rationale for these programs was that high birth rates "significantly increase the cost and difficulty of achieving basic development objectives by imposing burdens on economies presently unable to provide sufficient goods and services for the growing population."16 From the 1970s through the 1990s, USAID expanded international family planning assistance to include programs on fertility, reproductive and women's health, and maternal and child health, ultimately reorganizing the program into an Office of Population and Reproductive Health (PRH).17 The expansion of activities reflected changing attitudes and development strategies. Concerns about managing population growth were largely supplanted by a focus on advancing women's status and enhancing their individual health and empowerment.18 USAID family planning activities continued to utilize a multipronged approach, entailing the provision of contraception while also addressing broader reproductive health concerns.

USAID Priorities and Key Programs

USAID's FP/RH programs are administered through the Office of Population and Reproductive Health (PRH) within the agency's Global Health Bureau.19 PRH is responsible for setting technical and programmatic direction, providing technical leadership, and supporting field programming. USAID distributes FP/RH commodities (such as contraceptives) and related services primarily through contracts and grant agreements with nongovernmental organizations. The agency's technical and administrative staff oversee and monitor the work of implementing partners.

USAID FP/RH programming is organized around six priorities:

- 1. Supporting healthy timing and spacing of pregnancy.

- 2. Advancing community-based delivery of FP/RH services, such as deploying front-line community health workers to disseminate commodities and information, and to arrange referrals.

- 3. Ensuring adequate supplies of contraceptives.

- 4. Providing non-coerced access to surgical sterilization20 and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCS), such as intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants.

- 5. Integrating FP/RH and HIV/AIDS programs to ensure that HIV-positive men and women have access to family planning information and services, for disease prevention and to prevent mother-to-child transmission of the virus.

- 6. Integrating FP/RH and maternal and child health (MCH) programs, specifically during the postpartum period, when there is considerable demand from new mothers for contraception to ensure pregnancy spacing.

In addition to these priorities, USAID FP/RH programs may also focus on related policy areas, such as efforts to end child marriage, female genital mutilation and cutting, and gender-based violence; and related health goals, including the prevention of fistula.21

Programs and Activities

USAID works with implementing partners to fund programs and provide technical assistance for the following family planning and reproductive health programs and activities:

Delivery of FP/RH services.22 Examples include providing women with counseling to promote awareness of available contraceptives or other methods of birth control, or procedures at health facilities to insert Intrauterine Devices (IUDs) or other forms of Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARCs).23

Contraceptive supply and logistics—implementation and management of supply chains for contraceptives, including condoms. In FY2018, for example, USAID donated 28 million male condoms to developing countries through the agency's implementing partners.24

Biomedical and social science research—the study of biomedical and social science evidence to identify best practices in programming and implementing family planning services.25 For example, USAID created Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and partnered with national governments and implementing partners to use the tool for conducting household- and facility-based surveys on health attitudes and behaviors in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe.

In addition, USAID provides direct technical assistance to foreign ministries of health and other partners, focusing on the following areas:

Performance and quality improvement—the use of data to improve both access to FP/RH services and their quality.26 For example, data from USAID-supported surveys are used to analyze women's use of family planning methods (e.g., effectiveness of contraceptive method, provider attitudes towards patients, or provider-patient interactions).27

Health communication—the use of mass media, community-level, and interpersonal communication strategies to expand knowledge of contraception, healthy approaches to birth spacing, and sex education, as well as awareness and prevention of GBV, forced early and child marriage (FECM), and FGM/C. For example, USAID supports community health promoters and behavior change campaigns, to educate women and their families on a variety of issues such as access to reproductive health services, the importance of maternal and neonatal health provider check-ups, and the health and psychosocial risks of FGM/C to women and girls.

Policy analysis and planning—support for the development, implementation, and monitoring of policies and laws that affect FP/RH policies and programs, and women's health outcomes.28 For example, USAID supported a research project in Kenya which analyzed the country's evolving health policies (e.g., the National Population Policy for National Development and the Adolescent Reproductive Health and Development Policy) and contraceptive distribution programs, to evaluate impact on Kenya's total fertility rate and contraceptive prevalence rate.29

|

Case Study: Uganda Uganda is a USAID priority country for FP/RH assistance due to its high maternal mortality ratio and low contraceptive prevalence rate. Uganda's population is one of the fastest growing in the world, with a 3.3% annual population growth rate, and one of the highest fertility rates in the world (an estimated 5.9 children per woman, more than double the global average of 2.5 children per woman). Roughly 40% of women surveyed in the country reported having an unmet need for contraception, which experts believe contributes to high maternal death rates in Uganda, where the MMR is 334 deaths per 100,000 women.30 USAID supports voluntary FP/RH programs in Uganda through public and private partnerships. In 2018, U.S. family planning aid for Uganda totaled $29 million and represented 6% of U.S. foreign assistance for health projects in Uganda.31 The vast majority of health aid in Uganda ($372 million, or 80%) is programmed through the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) to combat HIV/AIDS. Implementing partners for U.S. FP/RH aid include Management Sciences for Health, FHI 360, Jhpiego Corporation, and the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation.32 These programs support direct service delivery of family planning and reproductive health care, as well as social marketing, vouchers for contraceptives, and franchises for contraceptive sales. Associated funds support outreach campaigns and workplace programs to increase access to contraceptives. In addition, USAID provides technical assistance to the Ugandan Ministry of Health to improve contraceptive and family planning service availability, affordability, and quality within public health systems. USAID cites several indicators pointing to the success of family planning assistance in Uganda. From 2005 to 2018, the contraceptive prevalence rate increased from 19% to 36%, while the maternal mortality ratio has decreased from 550 deaths per 100,000 live births to 343 deaths per 100,000 live births.33 Source: USAID, Uganda: Global Health, February 28, 2019, https://www.usaid.gov/uganda/global-health. |

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E)—the evaluation of programs to understand the content, quantity, and potential effects of services being provided with U.S. government assistance.34

Integration of FP/RH and MCH activities─ According to USAID, access to family planning services can prevent 30% of maternal deaths (or approximately 90,000 deaths annually).35 USAID implementing partners often provide integrated FP/RH and MCH services, where appropriate. Many experts recognize MCH programs as a natural entry point for promoting awareness of and access to family planning services, as in the post-natal period evidence suggests that women have an increased desire to plan or prevent future pregnancies.36 For example, a mother bringing her child to a routine vaccination appointment might also be able to receive maternal health services and counseling on contraceptive options. Fourteen USAID-supported countries highlight integration of FP/RH and MCH as an approach to community health service delivery in their national government policies.37 However, USAID MCH programs are funded separately from FP/RH programs, as there are also FP/RH programs that focus on issues outside the realm of MCH (e.g., programs addressing adolescent sexual and reproductive health, prevention of FECM, GBV, FGM/C and obstetric fistula). In India, for example, USAID FP/RH funds supported programs to provide counseling and referral of GBV survivors to service providers, such as psychosocial counselors.38

Countries Receiving USAID FP/RH Assistance

In 2018, USAID supported bilateral family planning and reproductive health aid programs in more than 40 countries, including 24 "priority" countries, which are the focus of FP/RH programs and technical assistance and receive the majority of FP/RH funding. Most of these priority countries (23 of 24) are also categorized as MCH priority countries by USAID.39 To determine priority status, USAID evaluates which countries have

- the highest need, based on the magnitude and severity of their neonatal and maternal death rates;

- demonstrated national commitment to achieving sustainable and efficient program outcomes; and

- the greatest potential to leverage U.S. government support.40

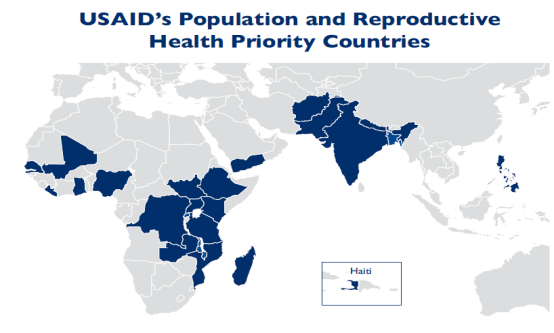

USAID FP/RH priority countries are largely in Africa (Figure 1). Compared with other developing nations and regions, Africa has the highest concentration of countries with low rates of modern contraceptive use and highest maternal mortality rates (Table B-1). In 2018, the top three recipients of U.S. FP/RH assistance were Nigeria ($37 million), Uganda ($29 million), and Tanzania ($28 million).41

|

|

Source: CRS prepared this figure using USAID, "Family Planning and Reproductive Health Program Note: The dark blue shading represents USAID FP/RH priority countries. |

In 2018, USAID provided $2 million or less (per country) annually to support FP/RH programs in an additional 18 countries that were assessed to have a need for family planning services (e.g., Benin), and/or a strategic foreign policy interest to the United States (see Table B-2). 42 For example, despite relatively low fertility and maternal death rates, Ukraine receives USAID FP/RH funds as part of a multifaceted approach to supporting Ukraine as a free and democratic state "in the face of continued Russian aggression."43

Criteria for Country "Graduation"

USAID formalized a country graduation process for FP/RH assistance in 2006, to transition countries off of U.S. foreign assistance for FP/RH programs and prioritize countries when allocating funding. The graduation strategy also aligns with the agency's "Journey to Self-Reliance," a policy framework established in 2018 to strengthen the ability of partner countries to support their own development agendas.44 Countries receiving family planning assistance may "graduate"45 once they have met certain criteria and a country program has achieved its stated goals. According to USAID, a country is eligible for graduation once it

- reaches a modern contraceptive prevalence rate of at least 51%; and

- reaches a level of fertility at or below 3.1 children per woman.

USAID also considers additional issues when evaluating a country's readiness for graduation. Countries who reach both criteria but lack the capacity to implement family planning programs or face other constraints may continue to receive assistance (e.g., India). USAID may also evaluate whether governments are allocating sufficient public funds for contraception procurement and whether their Ministries of Health demonstrate adequate capacity to manage the associated logistics and supply chain processes.46 Additional indicators considered for graduation include

- at least 80% of the population can access at least three methods of FP;

- no more than 20% of FP products, services and programs offered in the public and private sectors are subsidized by USAID; and

- major service providers in all sectors (public, non-governmental, commercial) can meet and maintain standards of informed choice and quality of care.47

To date, USAID 25 countries have graduated, half of which are in Latin America and the Caribbean (Table B-4). For example, Brazil graduated in 2000, after the government, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector invested substantially in family planning assistance, and as the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased.48 USAID partners worked to build capacity in Brazil's civil sector and Ministry of Health programs, by focusing on outreach, education, and improved access to care. According to USAID, "the program worked with the government to reduce Brazil's legal obstacles and tariff barriers to the importation of medical equipment, foam, jellies, and oral contraceptives, as well as quality intrauterine devices and condoms not manufactured in Brazil."49 Perhaps reflecting these efforts, Brazil's contraceptive prevalence rate increased from 34% in 1970, to 72% in 2000.50 Other countries who were graduated (e.g., Mexico), demonstrated similar characteristics.51

Once a country graduates, PRH evaluates where U.S. resources can best be reallocated based on need. In 2011, for example, USAID formed the Ouagadougou Partnership (named for the capital of Burkina Faso) with funding reallocated from graduated Latin American countries. This partnership—which also involves the government of France, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Hewlett Foundation—seeks to improve access to family planning services in francophone West Africa. (Table B-3).

U.S. Funding

Bilateral FP/RH assistance is funded through a variety of accounts in annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations measures. The Global Health Programs (GHP) account is the funding channel for more than 90% of bilateral FP/RH aid while smaller amounts of bilateral FP/RH assistance are generally made available through other accounts. 52 Department of State Economic Support Fund (ESF) monies are provided to select countries considered by the State Department to be politically and strategically important. In recent years, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Jordan have received ESF funds for FP/RH activities. In FY2017, for example, Afghanistan, which is a USAID FP/RH priority country, received $20 million in bilateral family planning assistance, all of which was provided through the ESF.53

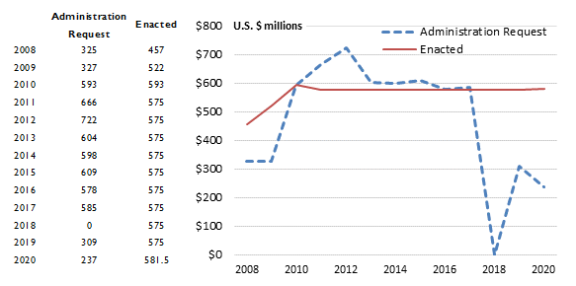

Over the past decade, enacted funding levels for bilateral international FP/RH aid have remained fairly consistent (Figure 2).

Although congressionally enacted funding has been constant since 2011, the absence of foreign assistance authorization legislation in recent decades has made annual consideration of foreign aid appropriations the primary venue for debating international family planning and reproductive health policy. Controversies that are frequently debated as part of the appropriations process include54

- codification of the Mexico City Policy/Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (MCP/PLGLHA), which is currently imposed through Executive Order (see "Selected Issues for Congress");

- the effect that withholding U.S. dollars as a result of such restrictions could have on access to voluntary family planning and other health services in developing countries; and

- whether or not designating funding for contraceptive provision and family planning is the best approach to allocating global health funds.

Members of Congress hold varied perspectives on these issues. Some Members have supported expanding access to FP/RH services, while others aim to increase restrictions on such services or reduce funding levels. in addition to these perennial concerns, debate in the 116th Congress regarding FP/RH programs has addressed issues such as the role of faith-based contractors in USAID FP/RH programs, bias and discrimination against potential aid recipients, and language around sexual and reproductive health.55 In recent years, controversy has also arisen over how FP/RH services are described in government documents, though it remains unclear whether language changes have had any impact on actual service provision.56

Selected Issues for Congress

When considering U.S. support for international family planning and reproductive health efforts, the 116th Congress may focus on three key areas: restrictions under the MCP/PLGHA, funding levels in appropriations bills, and program reforms proposed in pending legislation.

Mexico City Policy/PLGHA

The Mexico City Policy requires foreign nongovernmental organizations receiving USAID family planning assistance to certify that they will not perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning, even if such activities are conducted with non-U.S. funds. Since first applied in the Reagan Administration in 1984, the policy has been repeatedly lifted and reinstated through Executive Order. The policy was maintained by President George H.W. Bush and rescinded by President Clinton in 1993. It was then reinstated by President George W. Bush in 2001, who expanded the policy in 2003.57 President Obama rescinded the policy upon taking office in January 2009. The Trump Administration reinstated the policy, expanded it to include all U.S. global health assistance,58 and renamed it Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (PLGHA). The Trump Administration uses the two policy names interchangeably, though the Mexico City Policy until now only applied to international family planning and reproductive health programs. When discussing the policy under the Trump Administration, this report uses MCP/PLGHA.

MCP/PLGHA has never been enacted through legislation, and advocates have long encouraged Congress to codify the policy, making it harder for future Administrations to revoke. Simultaneously, detractors of the policy have called for enactment of legislation that would prevent the current practice of Administrations imposing the policy through Executive Order.

Some international FP/RH program advocates suggest there are issues and confusion regarding compliance with the expansion of MCP to include all global health assistance.59 They assert that the policy has rendered programs cumbersome and ineffective due to administrative and operational burdens associated with ensuring compliance, which divert resources from the health workforce, health information systems, and service delivery.60 Some field reports indicate that individual providers may not be aware of the restrictions because MCP/PLGHA is "embedded" in funding agreements, similar to "fine print," which can create barriers to care during a provider-patient interaction.61 Advocates of the expanded policy argue that it closes loopholes in the prior policy and does not cause an undue burden, asserting that the government must focus on compliance.62

In February 2018, the State Department released the findings of a six-month review of MCP/PLGHA.63 The State Department acknowledged the confusion the policy created, stated that the policy's impact on program effectiveness was minimal, and committed to conduct another review at the end of 2018.64 As of February 2020, the State Department had not announced plans for a second review. Congress could choose to mandate completion of the second review through legislation or examine the situation through oversight activities.

Setting Funding Levels for International FP/RH Programs

In recent years, congressional debates regarding international FP/RH assistance have centered on where and how such funding should be spent.65 For FY2020, Congress appropriated $575 million to international family planning programs. Some advocates have argued that global FP/RH funding levels would need to be doubled in order to make family planning and reproductive services accessible to all women who currently want and lack access to them.66 Proponents say that consistently flat funding is equivalent to FP/RH spending cuts, and this undermines U.S. global development goals on maternal and child health.67 Advocates note that the U.S. government would need to invest $1.5 billion to meet its appropriate share of the burden for foreign assistance for FP/RH funding, and other donor countries cannot fill the gap.68 Opponents of the aid have questioned the extent of international demand for family planning services and have suggested that international family planning resources could be better used on other development activities.69 Further, opponents argue that international family planning services are controversial in some countries due to religious and moral beliefs,70 which, in their views, raises questions about whether increased donor funding would lead to increased use of contraceptives and reproductive health care services or to better maternal health outcomes.71 Some observers also question whether the programs have been efficient and cost-effective, given the scale of U.S. spending on bilateral family planning programs, compared to other types of U.S. assistance.72 While data appears to show positive program impact in some countries,73 the attribution of results specifically to U.S. programming can be debated given the many factors that influence contraceptive use, including social and economic change and the activities of other international donors. In this context, Congress may consider whether funding levels for bilateral international family planning assistance align with need and potential impact, as well as with U.S. strategic goals and foreign policy objectives.

Formal Integration of FP/RH and MCH Programs and Funding Streams

Currently, though some U.S. international FP/RH and MCH programs may be integrated (e.g., both types of health services are provided together), most are not, due in part to separate line item funding in the annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations measures, separate funding entails separate program administration. Proponents of further program integration want to combine FP/RH and MCH services; they note that integration of these services has been shown to increase women's use of contraception, improve maternal health outcomes, and build health systems capacity.74 Integration of these funding streams may also provide more flexibility to implementing agencies to prioritize funding across a broader range of programs.

On the other hand, eliminating funding directives specific to FP/RH and MCH may also reduce congressional control over how funds are used. Furthermore, opponents note that respect for local cultural norms must be considered; in some contexts, service integration could be detrimental to MCH activities if they are associated with less socially acceptable family planning programs.75 Aid-recipient countries may also resist integration of these programs when separate government health units administer international FP/RH and MCH services and may fear losing prioritization and resources.76 Others have also raised concerns that embedding FP/RH programs in MCH services would limit USAID programs to address adolescent sexual and reproductive health, and prevent CEFM, GBV, and obstetric fistula - that are distinct from family planning.77 Congress may consider whether formally integrating FP/RH and MCH funding streams would be beneficial to program efficacy, or if existing appropriations and implementation mechanisms best further the stated objectives of U.S. international FP/RH and MCH programs.

Pending Legislation

In addition to appropriations legislation, a few proposals specific to international FP/RH are pending in the 116th Congress:

- H.R. 661, the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance Act of 2019, which would amend the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2351). This legislation was introduced to codify the Trump Administration's expansion of the Mexico City Policy to include all global health assistance. It would "prohibit U.S. assistance to foreign nonprofits, nongovernmental organizations, or quasi-autonomous organizations that promote or perform abortions, except in cases of rape or incest or where the mother's life is endangered."78

- H.R. 1581, the Reproductive Rights are Human Rights Act of 2019, and S. 707, the corresponding Senate bill, would amend the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2351) to "include in its annual reports on human rights in countries receiving U.S. development and security assistance a discussion of the status of reproductive rights in each country, including whether a country has adopted and enforced policies to:

(1) promote access to contraception and accurate family planning information,

(2) provide services to ensure safe and healthy pregnancy and childbirth,

(3) expand or restrict access to safe abortion services,

(4) prevent maternal deaths, and

(5) prevent and treat sexually transmitted diseases."

The bills would also require the reports to include data on maternal deaths and discrimination and violence against women and girls in health care settings, including the government's response to these actions.79

Appendix A. Restrictions on U.S. Funding for Voluntary FP/RH Programs

|

Amendment Name |

Description |

|

Helms (1973) |

Prohibits the use of U.S. foreign assistance funds to perform abortions or motivate or coerce individuals to practice abortions. |

|

Involuntary Sterilization (1978) |

Prohibits funding for involuntary sterilizations or the coercion of involuntary sterilizations. |

|

Peace Corps (1978) |

Prohibits funding for abortions for Peace Corps volunteers. |

|

Biden (1981) |

Prohibits funding for biomedical research related to abortion or involuntary sterilization. |

|

Siljander (1981) |

Prohibits funding to lobby for or against abortion. |

|

DeConcini (1985) |

Funding shall be made available to family planning projects that offer, directly or through referral to, a broad range of family planning methods and services. |

|

Additional Provision on Involuntary Sterilization and Abortion (1985) |

Funding under part I of the Foreign Assistance Act is prohibited for any country or organization if the President certifies the use of such funds violates the Helms, Biden, or involuntary sterilization amendments. |

|

Kemp-Kasten (1985) |

Prohibits funding to any organization which, as determined by the President, supports or participates in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization. |

|

Livingston (1986) |

Prohibits discrimination against organizations based on their religious or conscientious commitment to only offering "natural" family planning when awarding grants. |

|

Leahy (1994) |

States that the term "motivate" in the Helms amendment (or any other law as it relates to family planning assistance) shall not be construed to prohibit the provision of information or counseling about all pregnancy options. |

|

Tiahrt (1998) |

Directs voluntary family planning projects supported by the U.S. to comply with five requirements: (1) no quotas in projects (2) no payment of incentives or bribes (3) projects shall not be denied rights or benefits as a result of not accepting FP services; (4) the project shall provide information on health benefits and risks of method chosen; and (5) project shall ensure that experimental contraceptive drugs and other procedures are provided in the context of a specific study in which participants are advised of potential risks. |

|

Mexico City Policy (MCP)/Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (PLGHA) Policy |

MCP restricts U.S. family planning assistance to foreign NGOs engaged in voluntary abortion activities, even if such activities are conducted with non-U.S. funds. In 2017, the Trump Administration expanded the policy to include all U.S. global health assistance and renamed it PLGHA. |

Sources: Section 104(f)(1) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195; 22 U.S.C. 2151b(f)(1)), as amended by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-189). Section 104(f)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195; 22 U.S.C. 2151b(f)(2)), as amended by Section 104 of the International Development and Food Assistance Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-424; 92 Stat. 946). Title III of the Foreign Assistance and Related Appropriations Act, 1979 (P.L. 95-481 Stat. 1597). Section 525 of the Foreign Assistance and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1982 (P.L. 97-121; 95 Stat. 1657). Section 541 of the Foreign Assistance and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1986 (Section 101(i) of H.J.Res. 465; P.L. 99-190; 99 Stat. 1295). Section 541 of Section 101(i) of H.J.Res. 465, P.L. 99-190 (99 Stat. 1291). S.Amdt. 388 to H.R. 2577 [99th]. Title II of Section 101(f) of H.J.Res. 738, P.L. 99-500 (100 Stat. 1783-217). P.L. 103-306 (108 Stat. 1612). Section 101 of the Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1999 (P.L. 105-277, 112 Stat. 2681-154).

Appendix B. USAID FP/RH Priority Countries: Key Statistics, 2017

|

Country (by contraceptive prevalence rate, lowest to highest) |

Modern Contraceptive Prevalence Ratea |

Total Fertility Rate (children per woman)b |

Maternal Mortality Ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births) |

|

South Sudan |

3% |

5.2 |

789 |

|

Democratic Republic of Congo |

9% |

6.2 |

846 |

|

Nigeria |

11% |

5.7 |

814 |

|

Mali |

11% |

6.4 |

587 |

|

Mozambique |

16% |

5.5 |

489 |

|

Senegal |

17% |

5.2 |

315 |

|

Liberia |

20% |

4.8 |

725 |

|

Ghana |

20% |

4.2 |

319 |

|

Afghanistan |

24% |

5.1 |

396 |

|

Yemen |

28% |

4.4 |

385 |

|

Pakistan |

28% |

3.7 |

178 |

|

Uganda |

28% |

5.9 |

343 |

|

Haiti |

34% |

3.1 |

359 |

|

Tanzania |

34% |

5.2 |

398 |

|

Ethiopia |

36% |

4.6 |

353 |

|

Madagascar |

37% |

4.5 |

353 |

|

Philippines |

38% |

3.0 |

114 |

|

Zambia |

45% |

5.5 |

224 |

|

Rwanda |

47% |

4.1 |

290 |

|

Nepal |

48% |

2.3 |

258 |

|

India |

52% |

2.5 |

174 |

|

Kenya |

56% |

4.4 |

510 |

|

Malawi |

56% |

5.3 |

634 |

|

Bangladesh |

57% |

2.2 |

176 |

|

Global Average |

76% |

2.5 |

211 |

Source: CRS prepared this table using information and data from USAID, "Family Planning and Reproductive Health Program Overview," 2019; and World Bank and United Nations Population Division, Contraceptive prevalence, 2019. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2019. United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects: 2019 Revision.

a. Modern Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (MCPR) is defined as the percentage of married or in-union women aged 15-49 who are currently using one method of modern contraceptive, defined as a method that allows couples to have sexual intercourse at a mutually-desired time.

b. "Total Fertility Rate" is defined as the number of children per woman (aged 15-49).

|

Country (by lowest to highest Modern Contraceptive Prevalence Rate) |

Modern Contraceptive Prevalence Rate |

Total Fertility Rate (children per woman) |

Maternal Mortality Ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births) |

|

Benin |

10% |

4.9 |

397 |

|

Angola |

14% |

5.6 |

477 |

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

15% |

5.1 |

617 |

|

Burkina Faso |

18% |

5.6 |

320 |

|

Burundi |

23% |

6.1 |

548 |

|

Timor Leste |

26% |

5.4 |

215 |

|

Armenia |

30% |

1.6 |

26 |

|

Georgia |

37% |

1.8 |

25 |

|

Jordan |

43% |

3.5 |

46 |

|

Guatemala |

48% |

3.3 |

95 |

|

Ukraine |

51% |

1.5 |

19 |

|

Cambodia |

56% |

2.5 |

161 |

|

Honduras |

64% |

2.5 |

65 |

|

Zimbabwe |

67% |

3.7 |

443 |

Source: CRS prepared this table using information and data from CRS correspondence with USAID legislative affairs team, June 2019; and USAID, Other USAID-assisted Family Planning Countries, June 2019. World Bank and United Nations Population Division, Contraceptive prevalence, 2019. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2019. United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects: 2019 Revision.

|

Country |

Modern Contraceptive Prevalence Rate |

Total Fertility Rate (children per woman) |

Maternal Mortality Ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births) |

|

Guinea |

9% |

4.8 |

679 |

|

Benin |

16% |

4.9 |

405 |

|

Mali |

16% |

6.0 |

587 |

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

16% |

4.8 |

645 |

|

Mauritania |

18% |

4.6 |

602 |

|

Niger |

19% |

7.2 |

553 |

|

Togo |

20% |

4.4 |

368 |

|

Burkina Faso |

25% |

5.3 |

371 |

|

Senegal |

28% |

4.7 |

315 |

Source: CRS prepared this table using information and data from CRS correspondence with USAID legislative affairs team, June 2019. World Bank and United Nations Population Division, Contraceptive prevalence, 2019. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2019. United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects: 2019 Revision.

Notes: The Ouagadougou Partnership was formed in 2011 between USAID, the government of France, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Hewlett Foundation to improve access to family planning services in francophone West Africa. Ouagadougou partnership countries are considered to be USAID-assisted countries.

|

Country (by contraceptive prevalence rate, lowest to highest) |

Modern Contraceptive Prevalence Rate |

Total Fertility Rate (children/woman) |

Maternal Mortality Ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births) |

|

Turkey |

48% |

2.1 |

16 |

|

Tunisia |

53% |

2.2 |

62 |

|

South Africa |

55% |

2.4 |

138 |

|

Romania |

54% |

1.5 |

31 |

|

Sri Lanka |

56% |

2.1 |

30 |

|

Russia |

56% |

1.7 |

25 |

|

Morocco |

58% |

2.6 |

121 |

|

Indonesia |

59% |

2.5 |

126 |

|

Swaziland |

62% |

3.4 |

389 |

|

Panama |

63% |

2.5 |

94 |

|

Mexico |

67% |

2.2 |

38 |

|

Jamaica |

73% |

2.0 |

89 |

|

South Korea |

69% |

1.3 |

11 |

|

Paraguay |

68% |

2.5 |

132 |

|

Dominican Republic |

70% |

2.4 |

92 |

|

Honduras |

73% |

2.4 |

129 |

|

Botswana |

75% |

2.9 |

129 |

|

Peru |

76% |

2.4 |

68 |

|

Costa Rica |

76% |

1.8 |

25 |

|

Chile |

76% |

1.8 |

22 |

|

Thailand |

77% |

1.5 |

20 |

|

Ecuador |

80% |

2.5 |

64 |

|

Brazil |

80% |

1.7 |

44 |

|

Nicaragua |

80% |

2.2 |

150 |

|

Colombia |

81% |

1.8 |

64 |

Source: CRS prepared table using information and data from CRS correspondence with USAID legislative affairs team, June 2019; and World Bank and United Nations Population Division, Contraceptive prevalence, 2019. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2019.